Abstract

Continuous blood pressure (BP) measurement is essential for real-time hypertension management and the prevention of related complications. To address this need, a cuffless BP estimation technique utilizing biosignals from wearable devices has gained significant attention. This study proposes a feasibility approach that integrates microneedle array electrodes (MNE) for ECG acquisition with photoplethysmogram (PPG) sensors for cuffless BP estimation. The algorithm employed is a baseline multivariate regression model using PTT and RR intervals, while the novelty lies in the hardware design aimed at improving signal quality and long-term wearability. The algorithm’s performance was validated using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC) database, achieving a mean error range of ±5.28 mmHg for the SBP and ±2.81 mmHg for the DBP. Additionally, the comparison with 253 measurements from three volunteers against an automated sphygmomanometer indicated an accuracy within ±25%. Therefore, these findings demonstrate the feasibility of an MNE-based ECG with PPG for BP integration for cuffless monitoring of SBP and DBP in daily life. The MIMIC-based evaluation was performed to verify the feasibility of the regression model under ideal public-database conditions. The volunteer experiment, performed with the developed MNE-ECG hardware, served as a separate preliminary feasibility test to observe hardware behavior in real-world measurements.

1. Introduction

The prolonged COVID-19 pandemic has significantly changed daily routines, including social distancing, remote work, and online education [1]. These changes have led to reduced physical activity, particularly among individuals with hypertension, who exhibited increased sedentary behavior and decreased mobility [2]. As of 25 May 2022, COVID-19 had infected more than 526 million people globally and had caused over 6.2 million deaths, while contributing to a rise in hypertension, recognized as a major risk factor for cerebrovascular or cardiovascular disease [3,4]. Consequently, frequent and consistent blood pressure (BP) monitoring has become critical for the prevention and management of hypertension, and the demand for various devices that can be used for continuous BP monitoring has increased [5,6].

Conventional BP measurement techniques include invasive methods that involve the insertion of a catheter into a blood vessel, and non-invasive approaches like auscultatory and the oscillometric method using a cuff. However, these traditional techniques are unsuitable for continuous monitoring due to their cumbersome nature and limited portability. To overcome these limitations, cuffless and continuous BP estimation methods leveraging the correlation among psychological signals have been extensively studied [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Among these biosignals, the electrocardiogram (ECG) and photoplethysmogram (PPG) signals have received significant attention for pulse transit time (PTT)-based BP estimation [18,19]. PTT, defined as the interval between the ECG R-peak and the onset of the PPG waveform, represents the time required for a pulse to propagate between two arterial sites [7,8]. This parameter is strongly associated with vascular properties, such as elasticity and compliance. An increase in BP causes an increase in vascular tone, which in turn reduces PTT, whereas a decrease in BP causes a decrease in vascular tone, which in turn increases PTT. Using this inverse relationship between the BP and PTT enables cuffless BP estimation. To enhance the accuracy of BP estimation, researchers have incorporated machine learning algorithms (regression tree, multiple linear regression, generative adversarial network, support vector machine, tree-based pipeline optimization tool) [9,10,11]. Furthermore, deep learning algorithms using neural networks, attention mechanisms, or long short-term memory architecture demonstrated promising results for predicting systolic BP (SBP) and diastolic BP (DBP) [12,13,14,15,16]. Consequently, studies are being actively conducted on the PTT-based BP estimation using the ECG and the PPG signals.

The proposed continuous cuffless BP estimation relies on the measurement of the time delay between two points. However, sensor placements (position of the measurement sensors) and other factors, such as body posture and motion artifacts [20], affect the measurement. Conventional ECG monitoring typically employs Ag/AgCl gel electrodes patched to the skin surface because they are suitable for monitoring high-resolution bioelectrical signals with low-electrode impedance and less noise. Despite these advantages, gel-based electrodes have several known drawbacks, including skin itching, allergic reactions, skin irritation, and degradation over time due to drying, which increases the motion-induced noise in the collected signals and makes it unsuitable for long-term biosignal monitoring [21,22,23]. To address such limitations, this article proposes a wearable device incorporating a microneedle array electrode (MNE) for ECG acquisition, enabling painless skin penetration and improved signal-to-noise ratio of ECG signals measured in the epidermis, bypassing the high impedance of stratum corneum [24,25]. In this study, ECG signals were recorded using MNE, while PPG signals were obtained via an infrared sensor placed on the left index finger. The values of SBP and DBP were estimated by signal processing using the measured ECG and PPG signals. The findings of this study are expected to facilitate cuffless and long-term BP monitoring without time and space constraints. It is important to note that the public-database validation only reflects algorithmic performance and does not evaluate the proposed MNE hardware. The hardware performance is assessed separately through a small-scale feasibility experiment with volunteers, which is described later. Furthermore, the algorithm used in this study is not intended as a novel contribution. Instead, it serves as a baseline method to validate the feasibility of cuffless BP estimation using the proposed MNE-based ECG acquisition system.

2. Materials and Methods

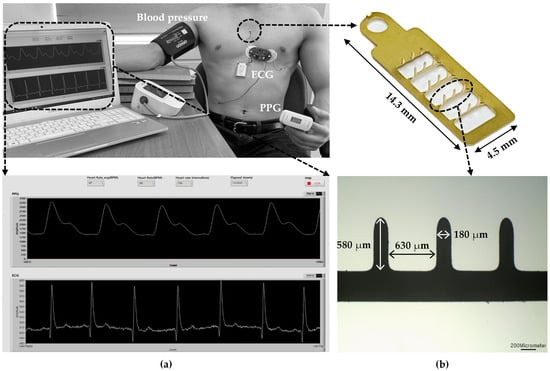

2.1. Fabrication of MNE

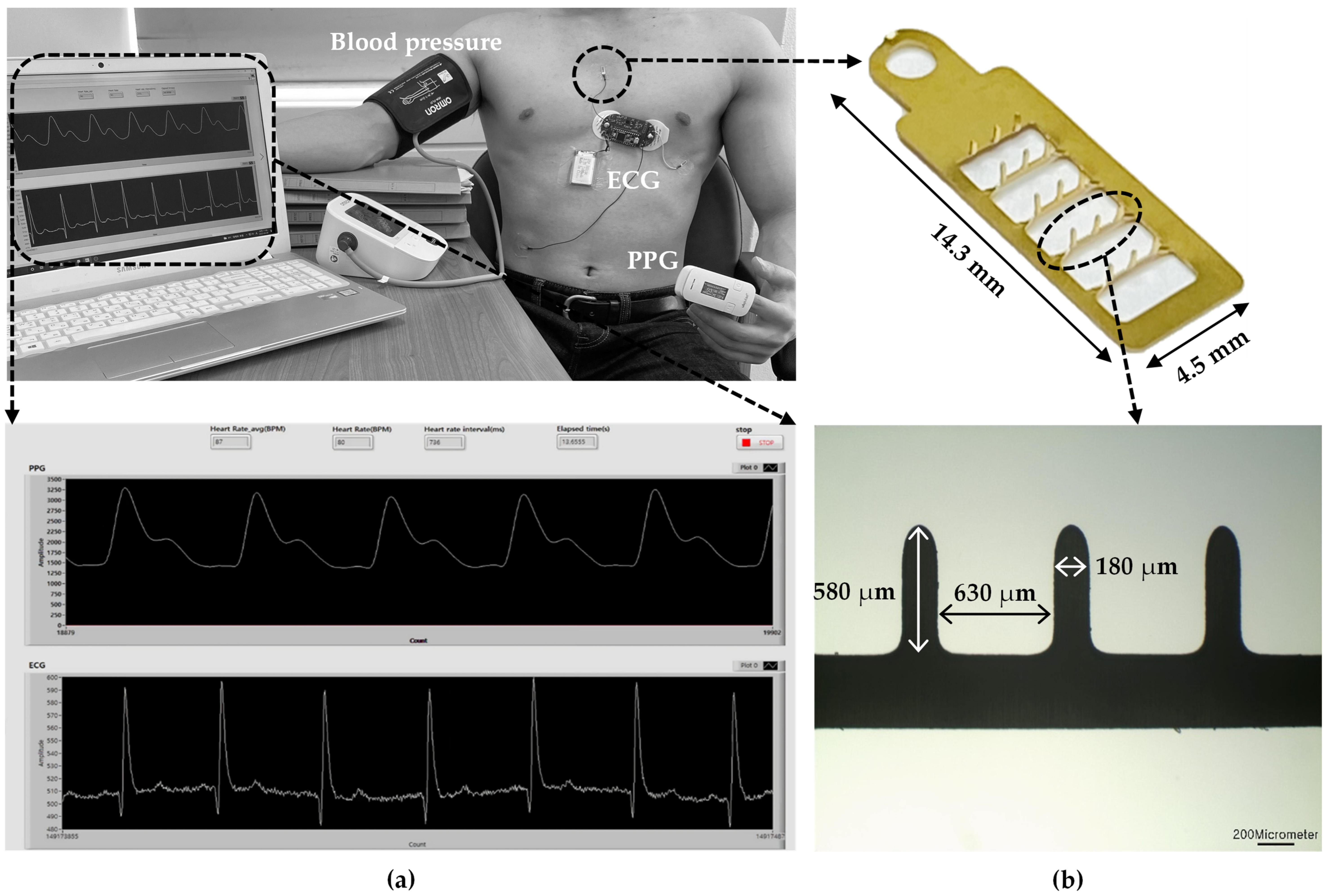

Figure 1 illustrates the experimental setup measuring ECG, PPG, and BP using the microneedle array electrode (MNE)-based system. First, the MNE for ECG measurements was fabricated by applying a pressure of 2 kgf/cm2 for 1 min after exposing the 100 μm 316 L stainless steel substrate to UV light with increased photosensitive resist in a ferric chloride etching solution. Next, a gold (Au) film layer was electroplated on the surface of the fabricated MNE. The microneedles were erected at 90° using a jig. An insulating layer, polyurethane skeleton (PUS301), was applied to minimize any electrical interference between the skin and base of the MNE. For the insulation, PUS301 was coated on the body of the MNE, and the tips of microneedles were inserted into polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) cured at a ratio of 10:1 (PDMS:curing agent). A UV curer (MCNet Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Gwangju, Republic of Korea) irradiated UV (wavelength of 365 nm) for 5 min for curing PUS301 (MCNet Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Gwangju, Republic of Korea). Finally, the PDMS was removed to fabricate the final experimental MNE.

Figure 1.

(a) Experimental setup of MNE-based ECG and PPG sensors and sphygmomanometer for the comparison of the measured BP with the estimated one; (b) LabVIEW-based program for simultaneous ECG and PPG recording.

2.2. Measurement of Biosignals

ECG measurements were performed using a previously developed portable system [20]. The system comprises a microcontroller with an analog digital converter (ADC), an AD8232 amplifier (Analog Devices, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA), filters, and a Bluetooth module. High- and low-pass filters were applied to remove noise, with cutoff frequencies set at 0.5 Hz and 40 Hz, respectively. To eliminate external interference from wires, Bluetooth communication was implemented using an HC-06 Bluetooth module (ITEAD Intelligent Systems Co., Ltd., Longgang Dist, Shenzhen, China), and a small polymer lithium-ion battery (LiPo) served as the power supply. A Teensy3.2 microcontroller (PJRC, LLC, Sherwood, OR, USA) was used for ADC functions. The Teensy 3.2 microcontroller employed a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter (ADC), corresponding to a theoretical voltage resolution of approximately 0.8 mV when operating at a 3.3 V reference. The ADC sampling jitter was specified by the manufacturer to be less than one clock cycle, which corresponded to <100 ns at the chosen clock configuration. This jitter was several orders of magnitude smaller than the millisecond-scale PTT intervals used in the BP estimation algorithm and therefore had a negligible impact on timing accuracy.

PPG signals were recorded using an infrared sensor (Ubpulse 360, LAXTHA, Inc., Daejeon, Republic of Korea), placed on the left index finger. The pulse waveform was measured through a COM port communication, and the data were used to calculate the interval between consecutive heartbeats. Heartbeats were then converted to beats per minute (BPMs) and averaged. ECG and PPG signals were sampled at frequencies of 200 Hz and 256 Hz, respectively, and monitored simultaneously using LabVIEW. For the serial communication of both signals (ECG and PPG) to the PC, the baud rate, data bits, stop bits, and parity were set to 115,200 bps, 8 bits, 1, and none, respectively. Although the ECG and PPG modules operated at different sampling rates (200 Hz for ECG and 256 Hz for PPG), both signals were transmitted over a single serial communication channel with timestamping. The Teensy-based acquisition firmware assigned a time index to each sample based on the microcontroller clock, allowing for the two signals to be aligned during post-processing by interpolation to a common time grid. Linear interpolation was used to resample both signals to 200 Hz prior to PTT estimation. This ensured that R-peak and PPG fiducial points were detected within a synchronized temporal reference frame.

BP was measured using an automatic electronic sphygmomanometer (HEM-7156T, OMRON, Co., Kyoto, Japan), with an accuracy of ±3 mmHg on the upper right arm. The measured BP values were compared with the BP values estimated by the developed algorithm using ECG and PPG.

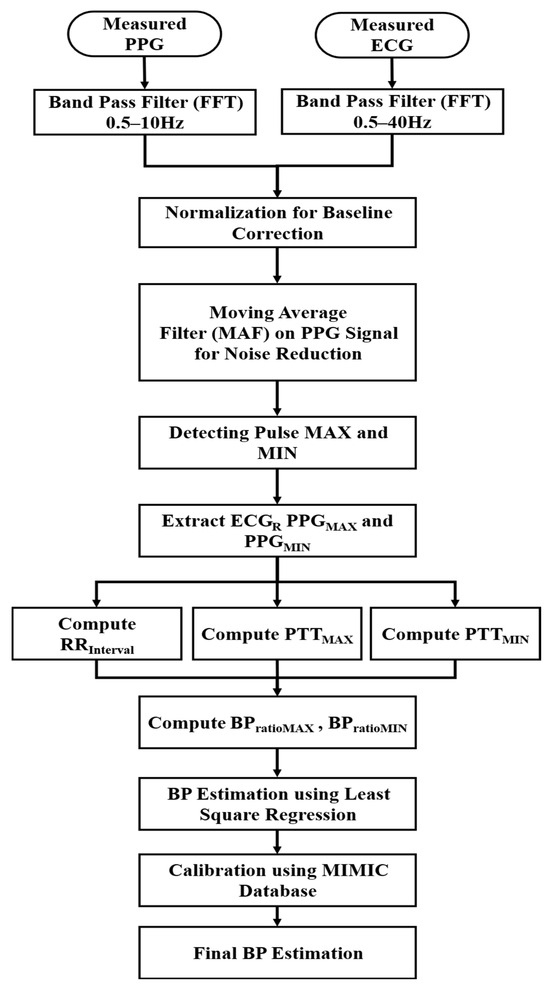

2.3. Biosignal Processing

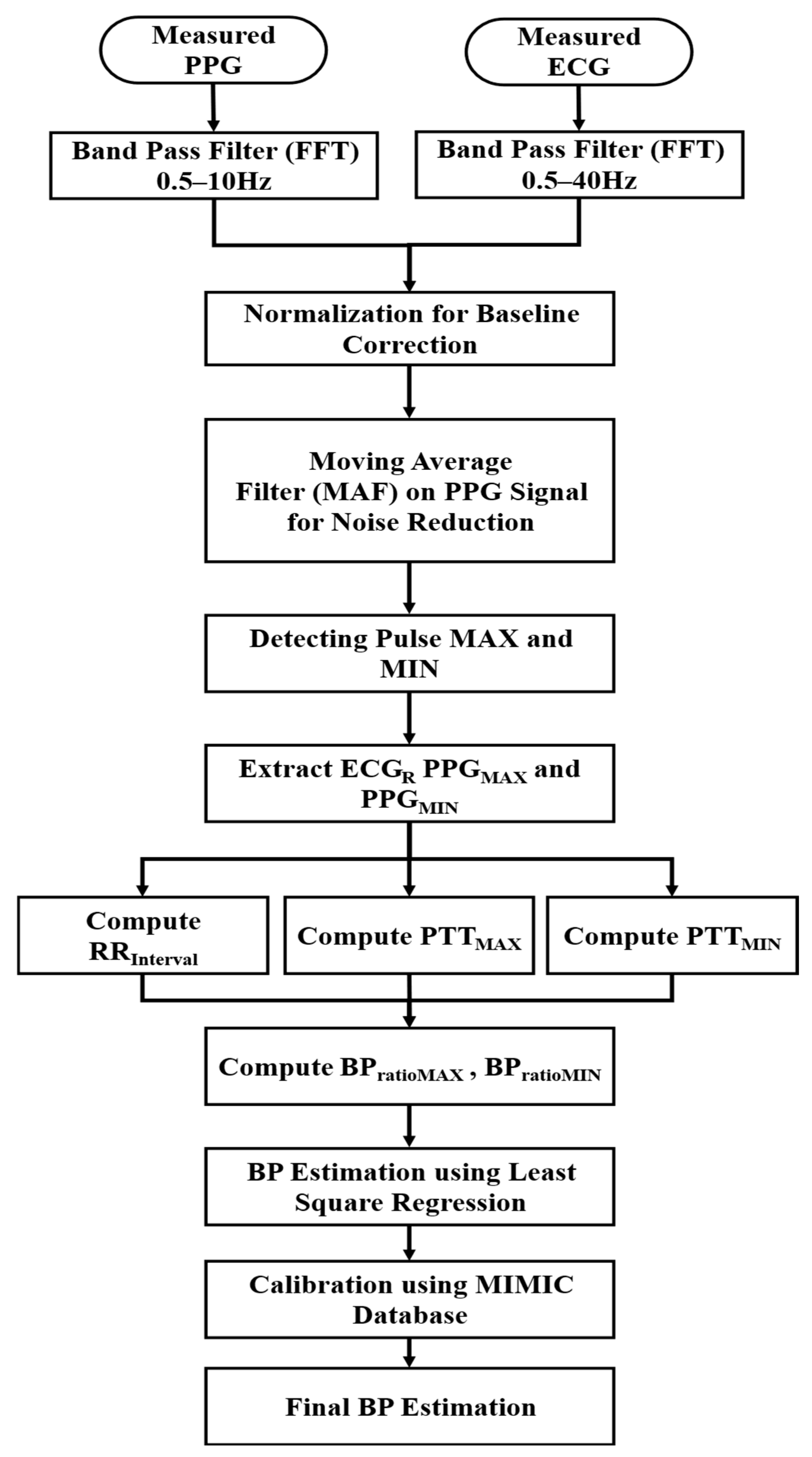

The measured ECG and PPG signals were analyzed to estimate SBP and DBP according to the data processing steps shown in Figure 2. To enhance the signal quality, frequency components of ECG and PPG data were selected using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) bandpass filter, allowing for frequencies within 0.5–40 Hz and 0.5–10 Hz, respectively. The chosen frequency ranges ensured the removal of baseline drift and high-frequency noise while preserving physiological signal components. Since the biosignal data consisted of pulsating (AC) and non-pulsating (DC) components [26,27], the baseline correction was performed through normalization. A moving average filter (MAF) was applied to remove noise from the PPG signals, which were highly sensitive to motion and respiration.

Figure 2.

BP estimation process using PPG and ECG data.

Afterward, the times corresponding to the maximum (MAX) and minimum (MIN) values of the pulse cycle were extracted by detecting the gradient of the rising pulse. The maximum (MAX) heart rate measured by the PPG (HRMAX [BPM]) was considered to determine the window size as follows.

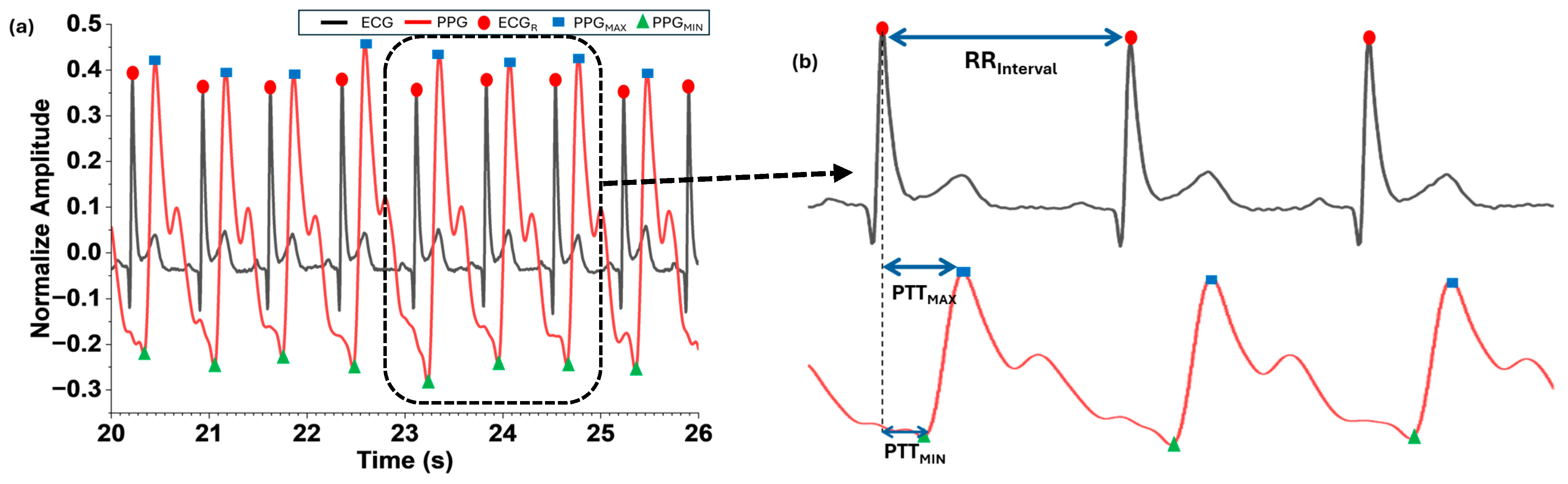

Through the MIN and MAX detection of the measured pulse cycles, the time corresponding to R-peaks of the ECG (ECGR) and MAX (PPGMAX) and MIN (PPGMIN) of the PPG were calculated. Although the PTT varied depending on the different blood arrival time points, this work defined the PTT based on the two points corresponding to PPGMAX and PPGMIN. PPGMAX and PPGMIN were selected as reference points for PTT calculation because they provided stable detection under our filtering approach. Alternative definitions, such as foot-to-upstroke or PAT-based intervals, were considered but not implemented in this study due to signal quality constraints and algorithm simplicity. Here, PTT denotes the time from the start of ventricular depolarization (R of the ECG) when blood is ejected from the heart until it reaches the capillaries at the tip of the index finger. PTTMAX in Equation (2) represents the interval between PPGMAX and ECGR, and PTTMIN in Equation (3) represents the interval between PPGMIN and ECGR.

Then the interval time between the current and previous ECGR () was computed using Equation (4). The ratio of the MAX and MIN changes in PTT to the was calculated as Equation (5) for and Equation (6) for .

The derived values using Equations (2)–(6) were applied to derive the equations for estimating BP through the least squares method. The coefficients and calibration constant were combined in Equation (7) for BP estimation and adjusted to improve the accuracy of the estimation of the BP according to the PPG measurement location or the vascular characteristics of individuals, i.e., heart rate variability and pulse rate variability.

where a–e are coefficients, and f is the calibration constant.

The values of the derived Equation (7) for BP estimation were adjusted by using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC) database extracted from the Physio Bank ATM, which provided simultaneously collected ECG, PPG, and BP data [28,29]. Calibration was performed by applying a least square fitting approach to optimize coefficients (a–e) and the constant (f) using MIMIC data. For volunteer tests, a global calibration constant was applied without subject-specific adjustment. Individual calibration, which typically involves one or two reference measurements per user, was not implemented in this feasibility stage but will be incorporated in future work to improve accuracy.

3. Results and Discussion

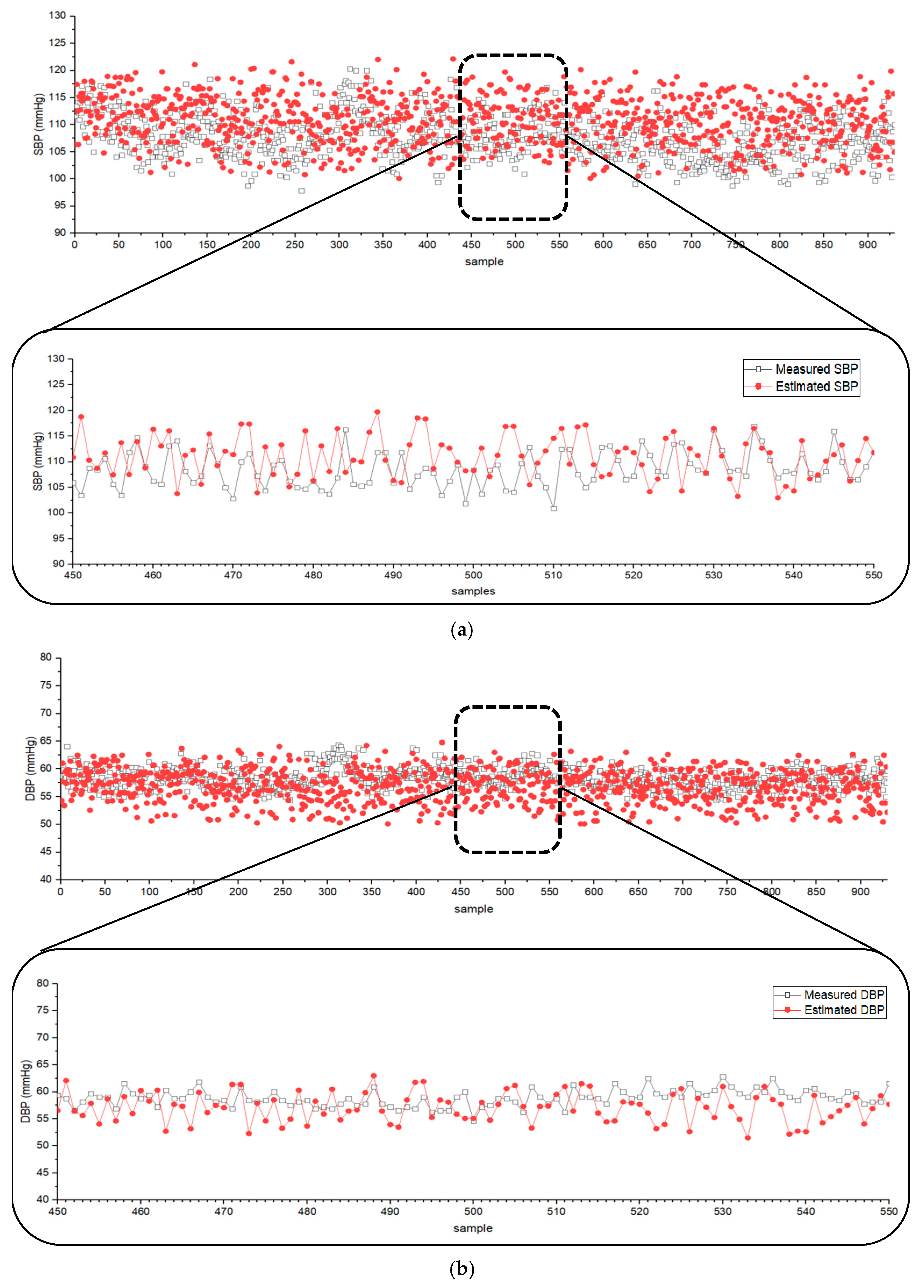

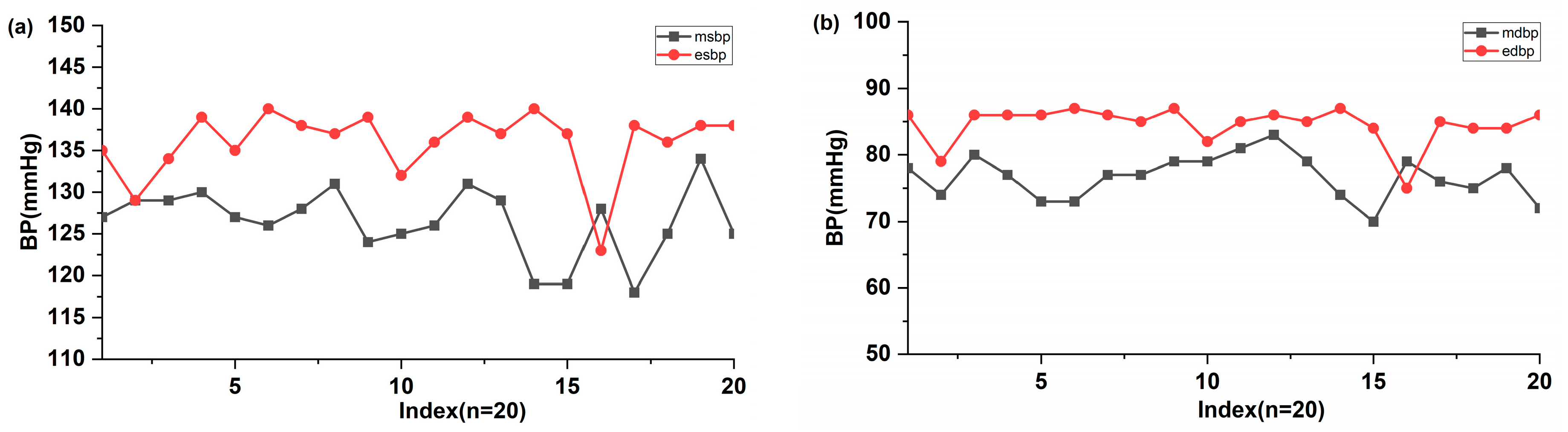

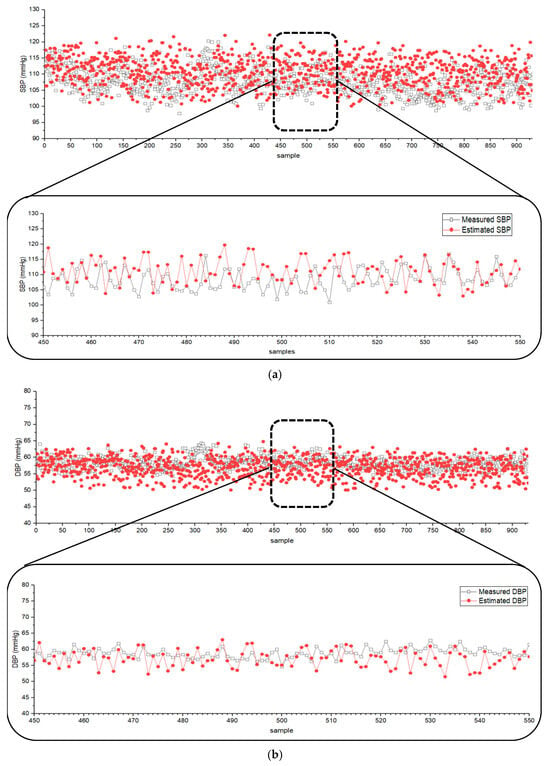

The derived BP estimation equations were applied to data from the MIMIC database, providing simultaneously recorded ECG, PPG, and BP data. The values of the proposed Equations (1)–(6) were obtained from the MIMIC data, and the coefficients in Equation (7) were adjusted to achieve optimal results. Figure 3 shows the estimated and measured SBP and DBP for 930 ICU patients registered in the MIMIC database when the coefficients of Equation (7) a to f were set to 2.47, −2.47, −0.56, −1864.60, 1576.49, and 563 for SBP, and 1.47, −1.67, −0.29, −1164.92, 1096.54, and 349 for DBP, respectively. The difference between the measured and estimated SBP and DBP was and (mean difference in mean standard deviation (SD)). The results indicated that the estimated BP values closely followed the trend of measured SBP and DBP using Equation (7).

Figure 3.

Scatter plots of (a) SBP and (b) DBP from the MIMIC database (n = 930) and the values estimated by the developed algorithm.

According to the [30] protocol (ANSI/AAMI/ISO) standard guideline, the criterion for the validation of BP measurement requires that the mean difference be below . Therefore, the established Equation (7) satisfies this criterion and is valid for BP estimation.

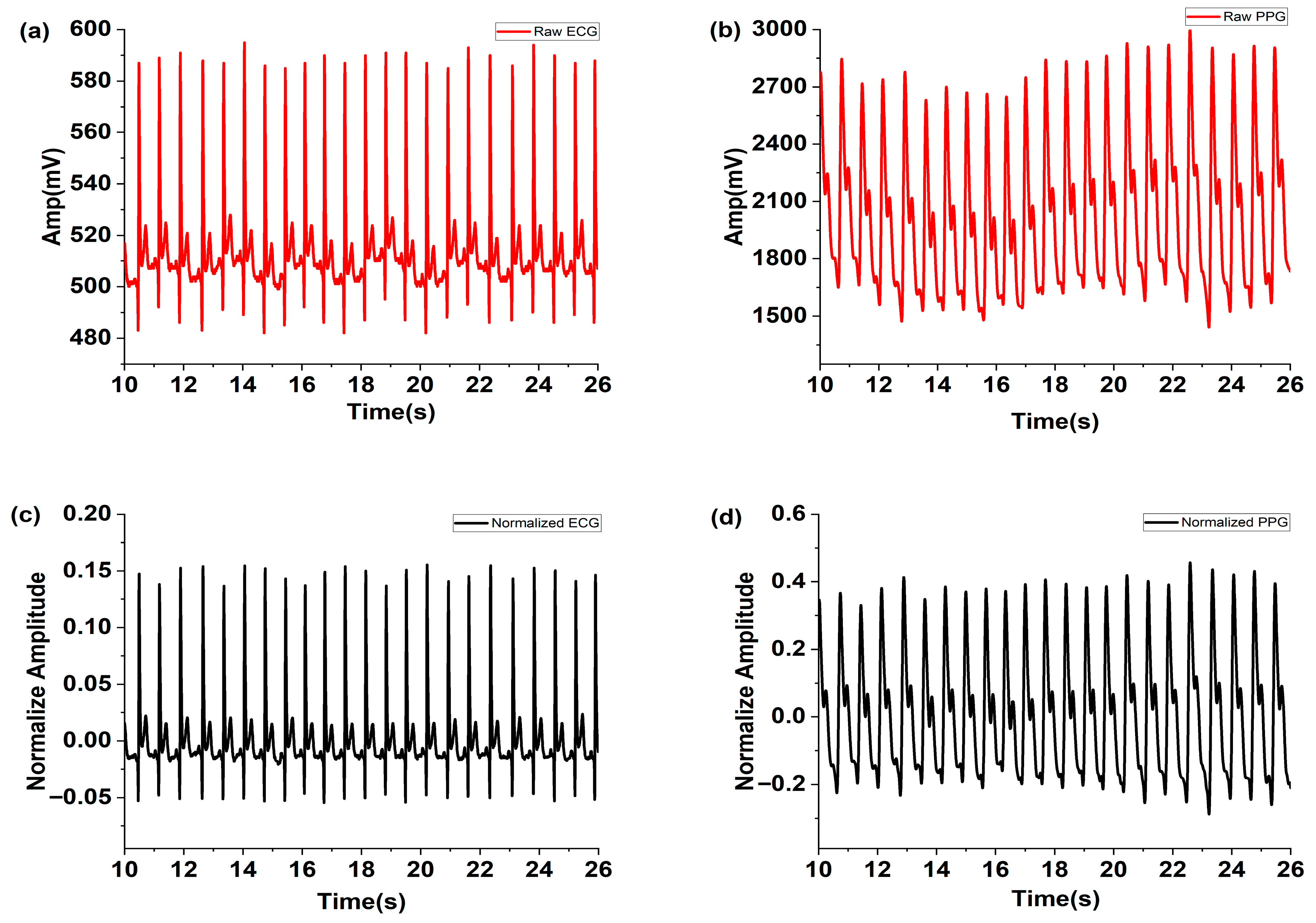

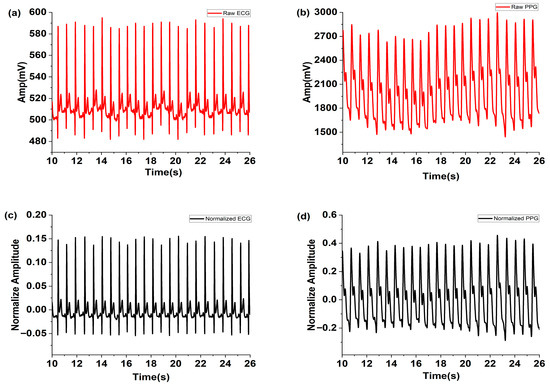

The raw ECG signals measured using the MNE and PPG signals are shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively. The normalized ECG and PPG signals filtered using MAF and FFT are depicted in Figure 4c,d. These figures demonstrate that noise was effectively removed by the applied MAF and FFT filters.

Figure 4.

Measured raw (a) ECG and (b) PPG, and the normalized (c) ECG and (d) PPG filtered using the MAF and FFT filter.

Although microneedle electrodes are reported in prior studies to offer advantages, such as reduced impedance and improved motion stability, this study did not include direct benchmarking against Ag/AgCl electrodes under identical conditions. Future work will involve parallel ECG recordings with both electrode types to compare signal-to-noise ratio, motion artifact suppression, and long-term wear comfort.

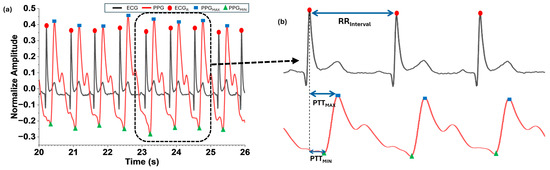

The normalized and filtered ECG and PPG signals were aligned along the recording time, and the parameters for Equations (2)–(4) were detected by using the signal processing steps shown in Figure 2. The algorithm was selected for its simplicity and widespread acceptance in PTT-based BP estimation studies. Our focus was on demonstrating the integration of MNE hardware with PPG sensors rather than introducing a new computational model. Figure 5 illustrates the detected points of ECGR, PPGMAX, and PPGMIN in the processed ECG and PPG signals and the calculated time intervals of RRinterval (n), PTTMAX, and PTTMIN.

Figure 5.

Detection of ECGR, (a) values derived from the normalized and filtered ECG and PPG (b) , , and .

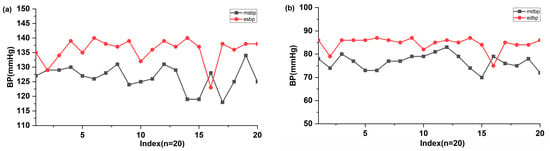

Finally, the proposed BP estimation method was applied to three volunteers. This small sample size was intended for feasibility demonstration only and did not represent a statistically valid clinical evaluation. A comparison of 20 measurements of SBP and DBP obtained using an automatic sphygmomanometer and the cuffless estimation algorithm was performed, with the results shown in Figure 6. The higher error observed in volunteer tests compared to MIMIC validation was attributed to subject-specific vascular variability and the absence of individualized calibration. The measured SBP and DBP were 126.5 ± 4.17 mmHg and 76.7 ± 3.29 mmHg (mean ± SD), respectively. Most estimated SBP and DBP values were 136 ± 4.09 mmHg and 84.55 ± 2.92 mmHg, which were higher than +2 SD of measured SBP and DBP. The mean differences for SBP (−9.5 ± 6.74 mmHg) and DBP (−7.85 ± 5.55 mmHg) were relatively high. These differences may be attributed to the time gap between the sphygmomanometer and the cuffless BP estimation. These results should be interpreted as preliminary feasibility rather than clinical validation.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the estimated (a) SBP and (b) DBP values (n = 20) with ones measured using the automatic electronic sphygmomanometer and estimated using the MNE and algorithm. The x-axis represents the sequential numbering of the 20 paired measurements.

Since the PPG device used was highly sensitive to motion, the BP estimation during vigorous activity remained challenging. Future studies could incorporate a pressure sensor into the PPG system to improve accuracy under movement conditions. In addition, practical limitations of MNE technology should be considered. Electrode durability over repeated use, user comfort during prolonged wear, and susceptibility to motion-induced artifacts are important factors for long-term deployment. While MNEs reduce skin impedance and improve signal quality, their mechanical integrity and ergonomic design require further optimization to ensure reliability and user acceptance. Furthermore, minimizing error through advanced algorithms could enable accurate BP detection in various daily life scenarios, including exercise. The current prototype does not meet ANSI/AAMI/ISO standards in volunteer tests; therefore, this cuffless BP monitoring method can only be used for fitness purposes or home healthcare, providing alerts for hypertension and hypotension in daily life. Future work will include clinical trials and calibration improvements.

To contextualize the performance of the proposed MNE-based ECG and PPG approach, this study compared its results with representative cuffless BP estimation studies reported in the literature. As summarized in Table 1, prior studies have employed various signal modalities (e.g., ECG, PPG, SCG, and BCG) and modeling strategies ranging from linear regression to deep learning. While our method achieved clinically reasonable accuracy using the MIMIC database and showed feasibility in a small volunteer cohort, the reported accuracy and validation scale remain below those demonstrated in larger studies. Nevertheless, the use of microneedle electrodes highlights a novel contribution toward improved signal quality and potential long-term wearability. Compared to recent studies using the MIMIC database and deep learning approaches [31,32], our method demonstrates feasibility with simpler regression modeling while introducing hardware innovation for enhanced ECG acquisition.

Table 1.

Representative cuffless BP estimation studies compared with proposed method.

For practical applications, the integration with wearable devices requires attention with regard to energy consumption and hardware design. Low-power microcontrollers, efficient signal processing, and wireless communication protocols will be essential to ensure continuous monitoring without frequent battery replacement. Future work will also explore flexible form factors and ergonomic designs to enhance user comfort and long-term adherence.

4. Conclusions

Continuous, non-invasive BP measurement is increasingly required in healthcare. In this study, a cuffless BP estimation method using the MNE-based ECG with PPG sensors and an algorithm to calculate the values of SBP and DBP was proposed and evaluated. The fabricated MNE enabled sensitive and accurate ECG measurement without interferences from motion noise, high impedance of stratum corneum, or side effects associated with the gel-based electrode. The MNE-based ECG and PPG for the cuffless BP estimation showed the mean difference of ±5.28 mmHg for the SBP and ±2.81 mmHg for the DBP from the MIMIC database. From the application of the cuffless BP estimation technique to three volunteers, it was found that the accuracy of the proposed method was within ±25%. Although accuracy does not yet meet ANSI/AAMI/ISO 81060-2:2013 standards in volunteer tests, the method demonstrates feasibility for cuffless BP estimation using MNE-based ECG acquisition. Future work will focus on larger cohort validation, comparative studies with Ag/AgCl electrodes, and include expanded clinical trials with larger cohorts to ensure statistical validity and compliance with international standards.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.P. and S.C.; methodology, software, Z.H., D.K., S.Y. and S.L.; validation, formal analysis, Z.H. and H.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K., S.Y. and S.L.; supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023R1A2C1003669).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Gachon University (IRB No. 1044396-202209-HR-180-01) in December 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Hyunmoon Park was employed by the company Energy Mining, Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC | Analog digital converter |

| BCG | Ballistocardiography |

| BP | Blood pressure |

| DBP | Diastolic BP |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| FFT | Fast Fourier transform |

| MIMIC | Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care |

| MNE | Microneedle array electrodes |

| PPG | Photoplethysmogram |

| PTT | Pulse transit time |

| SBP | Systolic BP |

| SCG | Seismocardiography |

References

- Stavridou, A.; Kapsali, E.; Panagouli, E.; Thirios, A.; Polychronis, K.; Bacopoulou, F.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Tsolia, M.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Tsitsika, A. Obesity in Children and Adolescents during COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2021, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durukan, B.N.; Vardar Yagli, N.; Calik Kutukcu, E.; Sener, Y.Z.; Tokgozoglu, L. Health related behaviours and physical activity level of hypertensive individuals during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2022, 45, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, F.; Zappa, M.; Oliva, F.M.; Spanevello, A.; Verdecchia, P. Blood pressure increase during hospitalization for COVID-19. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2022, 104, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citoni, B.; Figliuzzi, I.; Presta, V.; Volpe, M.; Tocci, G. Home Blood Pressure and Telemedicine: A Modern Approach for Managing Hypertension During and After COVID-19 Pandemic. High Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2022, 29, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Tang, O.; Brady, T.M.; Miller, E.R.; Heiss, G.; Appel, L.J.; Matsushita, K. Simplified blood pressure measurement approaches and implications for hypertension screening: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. J. Hypertens. 2021, 39, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganti, V.G.; Carek, A.M.; Nevius, B.N.; Heller, J.A.; Etemadi, M.; Inan, O.T. Wearable Cuff-Less Blood Pressure Estimation at Home via Pulse Transit Time. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 25, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figini, V.; Galici, S.; Russo, D.; Centonze, I.; Visintin, M.; Pagana, G. Improving Cuff-Less Continuous Blood Pressure Estimation with Linear Regression Analysis. Electronics 2022, 11, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, E.; De Vos, M.; Boylan, G.; Ward, T. Estimation of Continuous Blood Pressure from PPG via a Federated Learning Approach. Sensors 2021, 21, 6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fati, S.M.; Muneer, A.; Akbar, N.A.; Taib, S.M. A Continuous Cuffless Blood Pressure Estimation Using Tree-Based Pipeline Optimization Tool. Symmetry 2021, 13, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.H.; Shuzan, M.N.I.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Mahbub, Z.B.; Uddin, M.M.; Khandakar, A.; Reaz, M.B.I. Estimating Blood Pressure from the Photoplethysmogram Signal and Demographic Features Using Machine Learning Techniques. Sensors 2020, 20, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kwon, H.; Son, D.; Eom, H.; Park, C.; Lim, Y.; Seo, C.; Park, K. Beat-to-Beat Continuous Blood Pressure Estimation Using Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory Network. Sensors 2020, 21, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, C.C.; Lee, C.C.; Yeng, C.H.; So, E.C.; Chen, Y.J. Attention Mechanism-Based Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory Neural Networks to Electrocardiogram-Based Blood Pressure Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Park, T.J.; Chang, J.H. Novel Data Augmentation Employing Multivariate Gaussian Distribution for Neural Network-Based Blood Pressure Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Wang, D.; Yang, C. PPG-based blood pressure estimation can benefit from scalable multi-scale fusion neural networks and multi-task learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2022, 78, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.d.S.; Hasan, M.d.K. Cuffless blood pressure estimation from electrocardiogram and photoplethysmogram using waveform based ANN-LSTM network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2019, 51, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.H.; Sun, Y.; Wu, B.Y.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X. Using machine learning models for cuffless blood pressure estimation with ballistocardiogram and impedance plethysmogram. Front. Digit. Health 2025, 7, 1511667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zou, L.; Ji, Z. A review: Blood pressure monitoring based on PPG and circadian rhythm. APL Bioeng. 2024, 8, 031501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevskyi, O.; Trishch, R.; Sarana, V.; Yakovlev, M.; Popovici, E. Experimental analysis of blood pressure estimation using electrocardiography and photoplethysmography signals from fingertip measurements. Acta IMEKO 2025, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satti, A.T.; Park, J.; Park, J.; Kim, H.; Cho, S. Fabrication of Parylene-Coated Microneedle Array Electrode for Wearable ECG Device. Sensors 2020, 20, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Mahony, C.; Pini, F.; Blake, A.; Webster, C.; O’Brien, J.; McCarthy, K.G. Microneedle-based electrodes with integrated through-silicon via for biopotential recording. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2012, 186, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ren, L.; Chen, Z.; Pan, C.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, L. Fabrication of Micro-Needle Electrodes for Bio-Signal Recording by a Magnetization-Induced Self-Assembly Method. Sensors 2016, 16, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, T.; Kim, D.; Chung, W. Curved Microneedle Array-Based sEMG Electrode for Robust Long-Term Measurements and High Selectivity. Sensors 2015, 15, 16265–16280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, Ö.; Eş, I.; Akceoglu, G.A.; Saylan, Y.; Inci, F. Recent Advances in Microneedle-Based Sensors for Sampling, Diagnosis and Monitoring of Chronic Diseases. Biosensors 2021, 11, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Hong, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, T.; Shi, X.; et al. High-Performance Flexible Microneedle Array as a Low-Impedance Surface Biopotential Dry Electrode for Wearable Electrophysiological Recording and Polysomnography. Nanomicro Lett. 2022, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ward, R.; Elgendi, M. Hypertension Assessment via ECG and PPG Signals: An Evaluation Using MIMIC Database. Diagnostics 2018, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Xiao, X.; Chen, J. Advances in Photoplethysmography for Personalized Cardiovascular Monitoring. Biosensors 2022, 12, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Abbott, D.; Howard, N.; Lim, K.; Ward, R.; Elgendi, M. How Effective Is Pulse Arrival Time for Evaluating Blood Pressure? Challenges and Recommendations from a Study Using the MIMIC Database. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.E.W.; Stone, D.J.; Celi, L.A.; Pollard, T.J. The MIMIC Code Repository: Enabling reproducibility in critical care research. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2018, 25, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANSI/AAMI/ISO 81060-2:2013; Non-Invasive Sphygmomanometers—Part 2: Clinical Investigation of Automated Measurement Type. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013.

- Sanches, I.; Gomes, V.V.; Caetano, C.; Cabrera, L.S.B.; Cene, V.H.; Beltrame, T.; Lee, W.; Baek, S.; Penatti, O.A.B. MIMIC-BP: A curated dataset for blood pressure estimation. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, R.; Le, J.; Rudas, A.; Chiang, J.N.; Williams, T.; Alexander, B.; Joosten, A.; Cannesson, M. A review of machine learning methods for non-invasive blood pressure estimation. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2024, 39, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkebile, J.A.; Mabrouk, S.A.; Ganti, V.G.; Srivatsa, A.V.; Sanchez-Perez, J.A.; Inan, O.T. Towards Estimation of Tidal Volume and Respiratory Timings via Wearable-Patch-Based Impedance Pneumography in Ambulatory Settings. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 69, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaili, A.; Kachuee, M.; Shabany, M. Nonlinear Cuffless Blood Pressure Estimation of Healthy Subjects Using Pulse Transit Time and Arrival Time. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2017, 66, 3299–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harfiya, L.N.; Chang, C.C.; Li, Y.H. Continuous Blood Pressure Estimation Using Exclusively Photopletysmography by LSTM-Based Signal-to-Signal Translation. Sensors 2021, 21, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.H.; Harfiya, L.N.; Purwandari, K.; Lin, Y.D. Real-Time Cuffless Continuous Blood Pressure Estimation Using Deep Learning Model. Sensors 2020, 20, 5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.