Abstract

In recent years, with changes in dietary structure, beef has become the third most consumed meat in China after pork and chicken, with its consumption increasing by approximately 50%. The quality and commercial value of beef vary considerably across different muscles. However, due to the high similarity in the appearance of beef cuts and strong background interference, traditional image features are often insufficient for accurate classification. In this study, an improved convolutional neural network based on YOLOv11 was proposed. Four beef muscles were categorized: sirloin (longissimus dorsi), fillet/tenderloin (psoas major), oyster blade (infraspinatus), and ribeye (longissimus thoracis). A dataset comprising 3598 images was established to support model training and validation. We divided the dataset into training, testing, and validation sets in a 6:2:2 ratio. To enhance model performance, wavelet convolution (WTConv) was employed to effectively expand the receptive field and improve image understanding, while a large separable kernel attention (LSKA) module was introduced to strengthen local feature representation and reduce background interference. Comparative experiments were conducted with other deep learning models as well as ablation tests to validate the proposed model’s effectiveness. Experimental results demonstrated that the proposed model achieved a classification accuracy of 98.50%, with Macro-Precision and Macro-Recall reaching 97.38% and 97.38%, respectively, and a detection speed of 147.66 FPS. These findings confirm the potential of the YOLOv11n-cls model for accurate beef classification and its practical application in intelligent meat recognition and processing within the Chinese beef industry.

1. Introduction

Beef and its products provide high-quality protein and essential nutrients for a balanced diet, making it the third most consumed meat in China after pork and chicken [1]. Over the past decade, per capita beef consumption in China has increased by approximately 50% [2]. According to official statistics, annual per capita beef consumption rose from 0.668 kg in 1990 to 1.5 kg in 2021 [3]. Beef quality is influenced by multiple factors, including breed, age, fat-to-lean ratio, and anatomical location [4]. Even within the same carcass, substantial differences exist among muscles, resulting in variation in commercial value. Consequently, beef classification and cutting are essential to meet consumer demand for different muscles. According to the Chinese national beef grading standards and the Handbook of Australian Meat [5,6], together with a survey of surrounding beef retail markets to analyze common commercial classifications, beef cuts were categorized into four classes: ribeye (longissimus thoracis), sirloin (longissimus dorsi), fillet/tenderloin (psoas major), and oyster blade (infraspinatus). For clarity and consistency, the commercial names (ribeye, sirloin, fillet, and oyster blade) are used throughout the paper to refer to these muscle cuts, while the corresponding anatomical names are provided at their first mention. China is now the world’s third-largest beef producer; however, the cattle industry remains dominated by small-scale farmers using traditional extensive production systems [7]. As a result, beef sold in farmers’ markets, convenience stores and supermarkets is rarely labeled by specific muscle name. While butchers and professionals are generally able to identify beef cuts, ordinary consumers typically rely on visual inspection with the naked eye, a method based mainly on personal experience and perception, which is often difficult and unreliable for most people. This difference underscores the necessity of developing automatic and rapid beef muscle recognition methods.

In addition to serving consumer-oriented needs, automated recognition technologies also hold significant potential for the meat processing industry. With the ongoing modernization of meat processing, automated identification and classification of beef muscles can improve efficiency and reduce reliance on skilled labor. Moreover, such technologies can contribute to the standardization and digitalization of the meat supply chain. Therefore, computer-vision-based beef muscle recognition is not only valuable for improving consumer experience but also provides critical technical support for the automation and intelligent development of the meat processing sector.

Currently, leading techniques for meat detection include ultrasound, computer vision, near-infrared spectroscopy, hyperspectral imaging, Raman spectroscopy, and electronic nose technology [8,9,10]. These approaches are mainly applied to detect adulteration and to predict meat freshness and quality. Wang et al. proposed a method combining spectral analysis with machine learning to improve the accuracy of beef quality assessment. By optimizing feature extraction and classification algorithms, their approach reduces data variability and redundancy, thereby enhancing model performance [11]. However, such methods rely on spectroscopic analysis of beef composition, which involves complex experimental procedures and lacks real-time applicability, making them unsuitable for routine use [12]. Chen et al. combined machine vision with statistical parameters of intramuscular connective tissue and shear force to establish a stepwise multiple linear regression (Stepwise-MLR) model. Beef samples were classified into three tenderness levels—tender, medium, and tough—and the model achieved a prediction accuracy of 88.57%. These results demonstrate that integrating machine vision with statistical approaches can provide a rapid and non-destructive method for beef grading and prediction [13]. In addition, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) launched the Beef Remote Grading Pilot (RGP), which integrates simple technologies with robust data management and program oversight, enabling carcass characteristics to be evaluated and official quality grades assigned remotely [14]. Inspired by the application of deep learning, Huang et al. proposed a ResNet-based model to automatically identify pork cuts based on color and texture features [15]. Similarly, Jarkas et al. applied YOLOv5 in a factory setting for meat classification, achieving an accuracy of 85%, further demonstrating the effectiveness of artificial intelligence for meat identification in industrial environments [16].

Beef cuts, such as ribeye and fillet, exhibit high similarity in color, texture, and fat distribution, making them difficult to distinguish using traditional image features. In addition, for storage and transportation, beef is often packaged and refrigerated. Transparent boxes or bags, surface frost, and color or texture changes after freezing reduce image contrast and blur texture details, further increasing the difficulty of recognition. To address these challenges, this study applies deep learning to the recognition of fresh-cut beef. An improved YOLOv11n-cls model is proposed to better adapt the network to beef classification, offering a feasible solution with considerable potential for applications in daily consumption and meat processing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials and Pretreatment

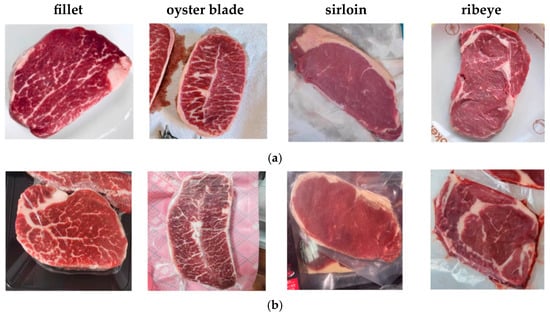

A total of 782 images of different beef cuts were collected, including four categories: fillet, oyster blade, sirloin, and ribeye. The dataset also covered three packaging conditions, as shown in Figure 1. Images were captured in meat markets, supermarkets, and online stores in Chengdu and Deyang (Sichuan Province, China) using a smartphone camera (12 MP, f/1.6). Most images were taken indoors under artificial lighting. All images were collected in Chengdu and Deyang, China. This regional limitation may affect the generalizability of the model to other cattle breeds, production systems, and international markets. Future research will include data collection from multiple regions and production environments to improve model robustness and cross-regional applicability.

Figure 1.

Example of Beef Classification Diagram. (a) Unpackaged; (b) packaged; (c) packaged and frost. (From left to right, the order is fillet, oyster blade, sirloin, and ribeye).

To prevent overfitting due to limited data, various image augmentation techniques were applied to expand the dataset. These included cropping, random rotation within ±60°, brightness adjustment, random horizontal and vertical translation of 10%, and random scaling by ±10%. Moreover, convolutional layers require input images of consistent dimensions, so normalization is necessary. In this study, images were resized to 224 × 224 pixels using the transforms. Resize function in PyTorch. After preprocessing, the dataset comprised 3598 images, including 925 fillet, 863 oyster blade, 921 ribeye, and 889 sirloin images. The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio, with 2398 images for training, 600 for validation, and the remaining 600 for testing.

2.2. Structural Enhancements of YOLOv11n-cls for Beef Image Recognition

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a class of deep learning models capable of automatically extracting image features and performing end-to-end classification. Their core principle is to use convolutional layers to capture local features, pooling layers to compress features, and fully connected layers to integrate and classify the extracted representations. CNNs have demonstrated outstanding performance in visual tasks such as image recognition, object detection, and semantic segmentation, learning hierarchical feature representations from low-level textures and edges to high-level semantic structures, thereby reducing reliance on traditional handcrafted feature engineering [17].

However, beef slice images present several challenges for visual recognition, including fine-grained texture differences, uneven fat distribution, reflections from transparent packaging, and surface frost after freezing, all of which can obscure prominent surface features. Meanwhile, traditional machine vision approaches typically rely on controlled lighting conditions and high-resolution industrial cameras to acquire high-quality images, which limits their practicality and generalizability in real industrial production environments [18].

2.2.1. YOLO Model

To address these challenges, this study employs the YOLO (You Only Look Once) model for feature extraction from beef images. Compared to traditional CNNs, YOLO series models offer significant advantages in feature extraction and object localization. YOLO transforms the object detection task into a single regression problem, simultaneously performing class prediction and bounding box regression in a single forward pass, thereby greatly enhancing detection speed and real-time performance. Therefore, this study selects YOLOv11n as the core framework for feature extraction and recognition, aiming to achieve rapid and accurate identification of different beef cuts under complex imaging conditions.

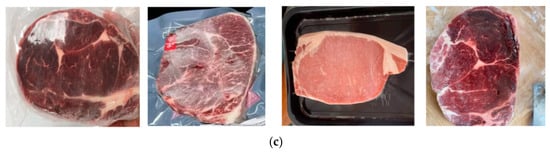

Network, the bottleneck module (Bottleneck) extracts image features through two convolutional layers, similar to ResNet [19,20]. To enhance the model’s ability to capture features at different levels, three convolutional layers are combined with the bottleneck module to form a C3 module. In the C3 module, the input is split into two paths: one passes through a complex route of convolutional and bottleneck layers, while the other passes directly through a single convolutional layer. The outputs of both paths are then concatenated (Concat), thereby improving the model’s representational capacity.

YOLOv11 emphasizes lightweight network design and introduces the EfficientRep backbone and RepOptimizer, making it well-suited for fine-grained, texture-sensitive tasks such as beef classification. In the YOLOv11 series, the C3 module is incorporated into C2f to form the C3k2 module, which combines the speed advantage of C2f with the flexibility of C3, as illustrated in Figure 2. For classification tasks, YOLOv11-cls optimizes the detection head to improve classification accuracy and inference speed while retaining the original detection framework. In this study, the lightweight YOLOv11n-cls was selected as the base model due to its small parameter size and high inference speed, making it suitable for deployment on mobile devices and real-time beef classification tasks.

Figure 2.

YOLOv11-cls C3k2 module.

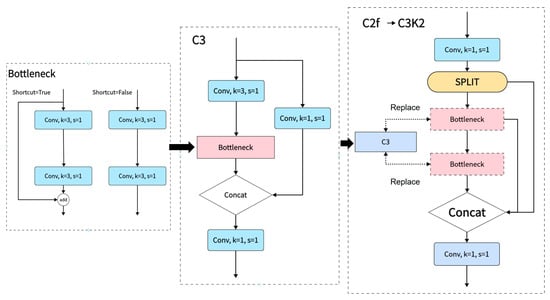

2.2.2. WTConv and LSKA for Texture Recognition

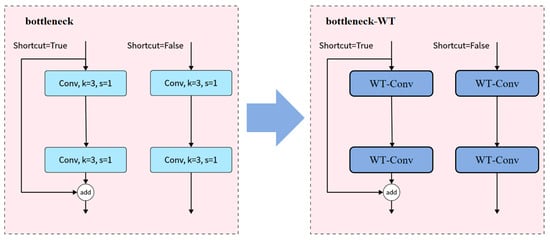

Due to factors such as packaging materials, cold-chain transportation, and freezing treatments, images of beef often exhibit blurred textures, loss of fine details, and reduced contrast. To address these issues, this study performs structural-level optimization of the feature extraction path based on YOLOv11n-cls. In the backbone network, WTConv (wavelet convolution) replaces the standard convolutional layers in the C3k2 module, expanding the effective receptive field and introducing multi-frequency representation, as shown in Figure 3. WTConv first decomposes the input into low-frequency (LL) and high-frequency (LH, HL, HH) components via wavelet transform (WT), followed by small-kernel depth-wise convolutions (DW-Conv) on each branch, and finally fuses the outputs through inverse wavelet transform (IWT) [21], as illustrated in Figure 4. Unlike conventional large-kernel convolutions, this structure significantly enhances the model’s ability to capture edge and texture features with minimal increase in parameters.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of the 2-level WTConv module.

Figure 4.

WT-Conv replaces Conv.

Meanwhile, to further enhance the network’s focus on critical regions and fine-grained textures, the LSKA (large separable kernel attention) module is incorporated into the C2PSA structure to enable dynamic receptive field adjustment, as depicted in Figure 5. LSKA captures local details via dense DW-Conv and expands the global receptive field through sparse DW-D-Conv, while decomposing the originally dense (2d − 1) × (2d − 1) convolution into 1 × (2d − 1) and (2d − 1) × 1 directional convolutions, achieving both low computational cost and strong representation capability [22], as shown in Figure 6. This integration enhances the network’s attention allocation to key texture regions across different beef cuts, improving feature discrimination.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the LSKA module.

Figure 6.

Insert the LSKA module into the C2PSA.

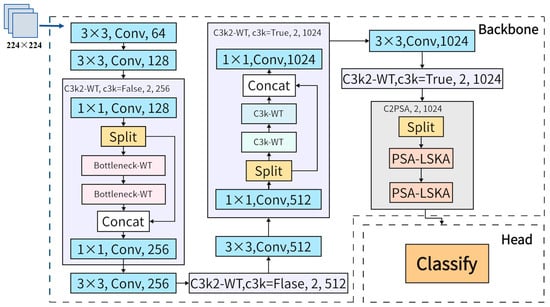

In summary, WTConv and LSKA are integrated into the C3k2 and C2PSA structures, respectively, to construct a feature extraction path better suited for fine-grained beef texture recognition. Based on the feature flow characteristics of YOLOv11n-cls, the placement, replacement strategy, and structural connectivity of these modules were optimized: WTConv expands the effective receptive field with small-kernel depth-wise convolutions and multi-frequency decomposition without significantly increasing parameters, while LSKA strengthens global modeling using separable large-kernel attention under low computational overhead. Moreover, the improved network exhibits a more uniform distribution of effective receptive fields across feature maps, facilitating the capture of fine-grained textures spanning different regions. Based on this structural-level integration strategy, we constructed the YOLOv11-cls-WT-LSKA model, achieving a better balance among model size, inference speed, and classification accuracy and the model architecture is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Structure diagram of YOLOv11-cls-WT-LSKA.

2.3. Model Training and Performance Evaluation

To validate the superior performance of the YOLOv11n-cls-WT-LSKA model in beef image recognition and classification, the hardware and software configurations, along with the training parameters employed in this experiment, are detailed as follows. The experiments were conducted on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i5-13400F processor (16 cores, 24 threads) and an NVIDIA RTX 4070 graphics card (12 GB VRAM), supplemented by 32 GB of KINGSTON RAM and a 2 TB KINGSTON SNV2S storage device.

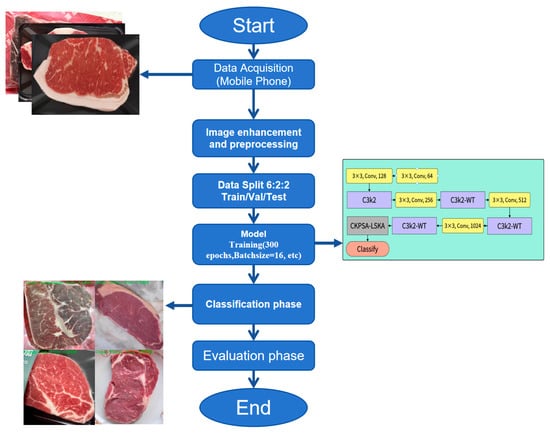

The experimental environment was based on Windows 11, utilizing Python 3.10.14 and PyTorch 2.2.2 for model training and inference, with CUDA 12.1 enabling GPU acceleration. During the training of the YOLOv11n-cls-WT-LSKA model, the configuration parameters outlined in Table 1 were applied, and the process is shown in Figure 8.

Table 1.

Training Parameters of YOLOv11n-WT-LSKA Model.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of Beef Classification.

The model’s performance was evaluated using the Confusion Matrix to validate its efficacy, incorporating three metrics: Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-Score, to assess the quality of the recognition model [23]. Within the Confusion Matrix, four fundamental indicators—True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN), and False Negative (FN)—visually depict the relationship between predicted results and actual labels. In binary classification tasks, TP denotes instances where the actual class is positive and predicted as positive; FP represents actual negative classes predicted as positive (false alarms); TN indicates actual negative classes predicted as negative; and FN signifies actual positive classes predicted as negative (missed detections) [24]. Utilizing the aforementioned parameters, the three model metrics (P, R, F1-Score) can be calculated as follows:

Precision (P) is defined as the proportion of correctly predicted positive samples among all samples predicted as positive by the model, calculated as follows:

In this formula, a precision (P) value closer to 1 indicates better model performance.

Recall (R) and Macro-Recall measure the proportion of actual positive samples that are correctly predicted by the model. While Recall evaluates performance on each class individually, Macro-Recall calculates the average of Recall values across all classes, giving equal weight to each class regardless of its sample size. A value closer to 1 indicates better model performance, and it is calculated as follows:

The F1-Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a comprehensive assessment of model performance. It is calculated as follows:

In addition, model performance was evaluated using prediction accuracy (Accuracy) and Macro-Precision (Macro-P), calculated as follows:

In the formula, denotes the total number of classes, set to 4, and represents the average precision (AP) for class

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Recognition Results and Comparison

Beef classification is a multi-class task, which can be decomposed into four binary classification tasks. This approach allows evaluation of whether the predicted label for each image matches the true label, and enables calculation of precision (P), recall (R), and F1-score for each beef cut, as presented in Table 2. The corresponding confusion matrix is shown in Figure 9.

Table 2.

Classification performance of YOLOv11n-WT-LSKA on the validation set.

Figure 9.

Confusion Matrix for Beef Recognition (a) Original Confusion Matrix; (b) Normalized Confusion Matrix.

Analysis of the model’s confusion matrix and the computed metrics (P, R, F1-score) indicates that recognition accuracy is relatively lower for fillet and ribeye, likely due to their similar color, texture, and fat–muscle distribution. In contrast, sirloin and oyster blade achieved higher metric scores, possibly because sirloin cuts often retain a layer of fat on top, and oyster blade cuts leave a portion of fascia in the middle, enhancing distinguishable features. The beef recognition results are shown in Figure 10, which includes four beef cuts (sirloin, ribeye, oyster blade, fillet) under three conditions (packaged, unpackaged, and packaged with frost).

Figure 10.

Identification results of four different types of beef from different parts. The Chinese text “西冷” shown in the image (second row, first column) corresponds to the English term “Sirloin”.

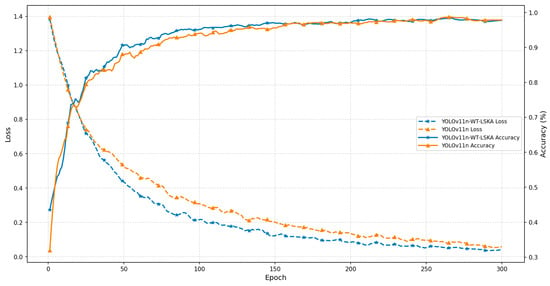

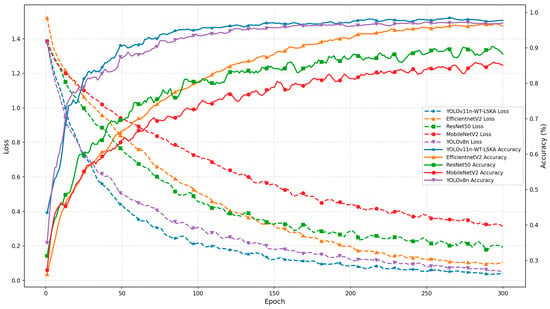

The training performance of the YOLOv11n-WT-LSKA model was compared with that of the YOLOv11n model on the beef dataset, including both training effectiveness and the accuracy of recorded loss values. As shown in Figure 11, the YOLOv11n-cls-WTConv-LSKA model reached 95% accuracy after 85 epochs, which is 33.33% higher than that of the original model. Regarding the loss curves, the improved model stabilized below 0.3 within 72 epochs, while the original YOLOv11n-cls model required 105 epochs to reach stability, indicating a reduction of 33 epochs in convergence. In addition, the proposed model exhibited a smoother loss curve, suggesting greater robustness against training instability.

Figure 11.

Comparison of model training performance.

3.2. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

This section compares the proposed model with relevant studies in the field of meat-related visual classification to provide meaningful reference. Existing research has primarily focused on meat freshness estimation or quality grading, whereas our work addresses fine-grained meat category recognition. A summary is provided in Table 3. Jiao et al. achieved an accuracy of 94.50% for pork freshness classification using a ResNet50-LReLU-Softplus neural network [25]. Büyükarıkan et al. conducted a systematic evaluation of multiple backbone networks on a meat-quality dataset, with the best performance of convVGG16 reaching 96.90%. Other models in the same study, including convMobileNet and convResNet50V2, reported accuracies of 84.00% and 71.20%, respectively [26]. More recently, YOLOv8n and its enhanced variant CBAM&SE-YOLOv8x achieved 99.99% accuracy on freshness-related tasks; however, the latter requires more than 12 M parameters and over 41 MB of model storage [6,27]. In contrast, the proposed YOLOv11-WT-LSKA attains an accuracy of 98.50% on the meat-recognition task while using only 1.4 M parameters and a model size of 2.9 MB.

Table 3.

Performance comparison of meat quality assessment models.

We further re-trained and tested the ResNet50, MobileNetV2, EfficientNetV2, and YOLOv8n-cls models under the same dataset, partitioning method, and data augmentation strategy [28]. The accuracy curves and loss function curves of different models are shown in Figure 12. The results indicate that the YOLO11n-cls-WT-LSKA model proposed in this paper performs well in both classification performance and model efficiency. As shown in Figure 9, its loss dropped below 0.4 within the first 50 cycles and eventually approached the theoretical lower limit. The convergence speed is faster than that of YOLOv8n-cls, EfficientNetV2, ResNet50, and MobileNetV2. The accuracy shows a monotonically increasing trend, the loss curve is smooth and has small fluctuations. The optimization process is more stable.

Figure 12.

Accuracy curves and loss function curves of different models.

After training, the performance evaluation results of the five models on the beef test dataset are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of Parameters of Different Models in the Validation Set.

EfficientNetV2 ranked second with an accuracy of 97.37%, but the model size increased to 7.9 MB and the computational cost was as high as 8.37 GFLOPs, with an inference speed of 125.02 FPS. Traditional deep network ResNet50 and lightweight representative MobileNetV2 performed poorly, with accuracies of only 86.33% and 82.00% respectively, and the ResNet50 model size was as high as 90.2 MB. In summary, YOLOv11n-cls-WT-LSKA outperforms YOLOv8n-cls and other classic classification networks in terms of accuracy, model size, inference speed and computational cost, and is suitable for real-time beef grading applications.

However, in real meat-processing environments, complex backgrounds, varying illumination conditions, and multiple overlapping meat blocks may pose challenges to the stability of the model. To address these issues, future research will focus on integrating attention-based enhancement modules, adaptive illumination compensation techniques, and multi-object detection strategies. It should be noted that the proposed model achieves a theoretical inference speed of 147.66 FPS and maintains a compact size with high accuracy when tested on an NVIDIA RTX 4070 GPU with 32 GB of memory. Nevertheless, due to the computational and memory limitations of actual edge devices, the inference speed may decrease in practical deployment scenarios. To verify the real-world deployment capability, subsequent work will include comprehensive on-board testing on embedded platforms. In addition, constructing a larger-scale industrial beef dataset that covers diverse illumination conditions, backgrounds, and cutting styles will further validate the robustness of the model in real production line environments. Furthermore, visual technology can be further extended to food adulteration detection, identification of meat source tampering, defense against adversarial samples, and other scenarios, thereby enhancing the overall credibility of intelligent meat processing systems [29,30].

3.3. Ablation Experiment

Ablation studies are widely adopted in deep learning to assess the impact of specific components by systematically removing or modifying them [26]. In this section, we evaluate the contributions of the proposed WT-Conv and LSKA modules through controlled experiments. The results are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of Different Modules on the Model.

After replacing the standard convolution with WTConv, the model’s mAP increased by 0.86 percentage points. The further incorporation of the LSKA attention mechanism led to an additional mAP improvement of 1.02 percentage points, resulting in a total gain of 1.88 percentage points. Although the parameter count decreased only modestly from 1,625,331 to 1,427,748 and the model weight dropped slightly from 3.1 MB to 2.9 MB, the improved model still maintained a compact and lightweight design, achieving a balance between performance enhancement and model efficiency.

As shown in Table 5:

- (1)

- Adding WT-Conv alone improves accuracy from 96.51% to 97.54% (+1.03 percentage points), demonstrating its strong capability in multi-scale feature representation.

- (2)

- Adding LSKA alone yields a smaller gain (+0.17 pp), reaching 96.68%.

- (3)

- The best performance of 98.50% is achieved when both modules are incorporated, resulting in a total improvement = +1.99 pp over the baseline and outperforming each individual module. This clearly validates the complementary effect of WT-Conv and LSKA.

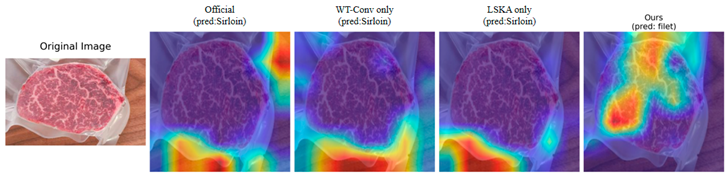

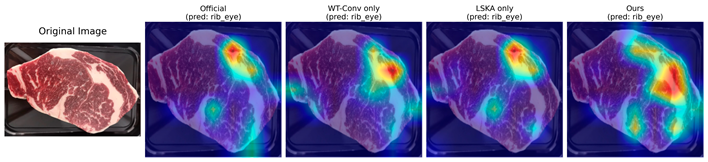

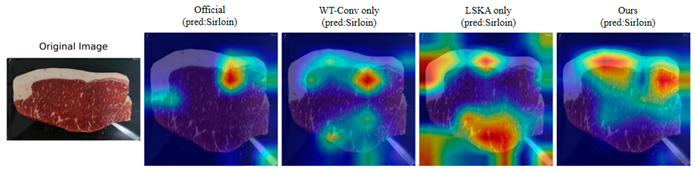

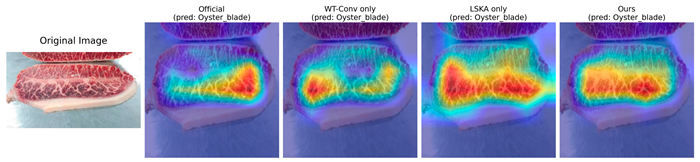

We further performed Grad-CAM++ attention visualization for four beef cuts (Fillet, Rib-eye, Sirloin, and Oyster-blade), as shown in Table 6. The results indicate that YOLOv11n-cls exhibits highly dispersed attention across all scenes and cuts, demonstrating weak capability in recognizing meat features; the highest activations are often incorrectly assigned to the tray or background, while key discriminative textures are ignored. Introducing WT-Conv alone significantly enhances the response to high-frequency textures, leading to more concentrated attention on the meat itself. LSKA alone further enlarges the receptive field and increases overall activation intensity, although some attention diffusion and interference from packaging remain. The proposed YOLOv11n-cls-WT-LSKA model achieves more complete attention focusing across all four cuts, with high-activation regions (red areas) closely aligning with the meat slices.

Table 6.

Comparison of Grad-CAM Heatmaps Generated by Different Models.

Notably, for the Fillet category, where texture features are relatively subtle, both the baseline and the two single-module ablation models misclassify it as Sirloin, with attention strongly distracted by packaging and background (first row of Figure 10). In contrast, the proposed model correctly identifies Fillet and produces high-activation regions that accurately cover the entire piece. These results demonstrate that the combination of WT-Conv and LSKA is essential for achieving high accuracy and robust performance in beef cut recognition tasks.

4. Conclusions

In this study, WT-Conv and LSKA modules were integrated into the YOLOv11n-cls model to expand the receptive field and enhance attention to discriminative beef features while maintaining a lightweight architecture. Experimental results show that YOLOv11n-cls-WTConv-LSKA achieves the highest overall accuracy (98.50%), Macro-P (97.85%), and Macro-Recall (97.30%) in beef grading tasks, with a compact model size of 2.9 MB and a fast inference speed of 147.66 FPS, demonstrating an excellent balance between accuracy, efficiency, and model compactness. In comparison, other models such as EfficientNetV2, ResNet50, MobileNetV2, and YOLOv8n exhibit trade-offs among accuracy, size, and speed. The proposed model also shows robustness against low-resolution images, packaging interference, and frost coverage, providing a practical solution for beef recognition in daily life and production lines. Future work will focus on evaluating the model on larger and more diverse datasets, extending it to other types of meat, and testing in real industrial environments, along with hardware-based deployment on mobile or edge devices to substantiate real-time performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H., W.M. and M.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and Y.H.; article ideas, W.M. and Y.H.; methodology, Y.H. and W.M.; software, H.L.; article search, H.L. and W.M.; article collation, H.L. and Y.H.; visualization, H.L.; supervision, W.M. and Y.H.; project administration, W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (ASTIP2025-34-IUA-10). China Agricultural Academy of Sciences Innovation Project-Urban Agriculture Big Data and Intelligent Management (ASTIP2024-34-IUA-10). Major Project at the Institute of Urban Agriculture of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (2024), Research and Application of Simplified Agricultural Machinery Equipment for Hilly and Mountainous Areas (SZ202405).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kantono, K.; Hamid, N.; Ma, Q.; Chadha, D.; Oey, I. Consumers’ perception and purchase behaviour of meat in China. Meat Sci. 2021, 179, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Lan, X.; An, J.; Shen, W.; Wan, F. Recent advances in feed and nutrition of beef cattle in China—A review. Anim. Biosci. 2022, 36, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Per Capita Beef Consumption of Chinese Households; CEIC Database: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01&zb=A0D0U&sj=2024 (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Liu, J.; Ellies-Oury, M.P.; Stoyanchev, T.; Hocquette, J.-F. Consumer perception of beef quality and how to control, improve and predict it? Focus on eating quality. Foods 2022, 11, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB/T 29392-2022; Quality Grading of Livestock and Poultry Meat—Beef [S]. State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China; Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2022. Available online: https://ndls.org.cn/standard/detail/2e7b5c6f87d4926bab16cf0687e0112a (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Handbook of Australian Meat, 7th ed.; AUS-MEAT Limited: Murarrie, QLD, Australia, 2005; Available online: https://www.aussiebeefandlamb.me/downloads/Handbook_of_Australian_Meat_7th_Edition-English.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Wang, Y. Current situation and development suggestions of beef cattle breeding models in China. Breed. Feed. 2024, 23, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, P.D.C.; Arogancia, H.B.T.; Boyles, K.M.; Pontillo, A.J.B.; Ali, M.M. Emerging nondestructive techniques for the quality and safety evaluation of pork and beef: Recent advances, challenges, and future perspectives. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Application and prospects of near-infrared spectroscopy technology in the meat testing industry. Mod. Food 2017, 25–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; Pi, J.; Wang, D. Research on Beef Marbling Grading Algorithm Based on Improved YOLOv8x. Foods 2025, 14, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X. Beef quality identification based on classification feature extraction and deep learning. Food Mach. 2022, 38, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.N.; Orvañanos-Guerrero, M.T.; Domínguez-Soberanes, J.; Álvarez-Cisneros, Y.M. Analysis of beef quality according to color changes using computer vision and white-box machine learning techniques. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ding, D.; Li, B.; Shen, M.; Lin, S. Research on relationship between beef connective tissue features and tenderness by computer vision technology. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2016, 39, 865–871. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Agricultural Marketing Service. Remote Beef Grading Service. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/remote-beef-grading (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Huang, H.; Zhan, W.; Du, Z.; Hong, S.; Dong, T.; She, J.; Min, C. Pork primal cuts recognition method via computer vision. Meat Sci. 2022, 192, 108898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarkas, O.; Hall, J.; Smith, S.; Mahmud, R.; Khojasteh, P.; Scarsbrook, J.; Ko, R.K. ResNet and YOLOv5-enabled non-invasive meat identification for high-accuracy box label verification. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J.; Al-Dujaili, A.; Duan, Y.; Al-Shamma, O.; Santamaría, J.; Fadhel, M.A.; Al-Amidie, M.; Farhan, L. Review of Deep Learning: Concepts, CNN Architectures, Challenges, Applications, Future Directions. J. Big Data 2021, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silmina, E.P.; Sunardi, S.; Yudhana, A. Comparative Analysis of YOLO Deep Learning Model for Image-Based Beef Freshness Detection. J. Ilmu Pengetah. Teknol. Komput. 2025, 11, 250–265. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 9 September–4 October 2024; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, K.W.; Po, L.M.; Rehman, Y.A.U. Large separable kernel attention: Rethinking the large kernel attention design in CNN. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 236, 121352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, D.M.W. Evaluation: From precision, recall and F-measure to ROC, informedness, markedness and correlation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyanarayanan, S.; Tantri, B.R. Confusion matrix-based performance evaluation metrics. Afr. J. Biomed. Res. 2024, 27, 4023–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Wang, W.; Hou, J.; Sun, P.; He, Y.; Gu, L. Freshness identification of Iberico pork based on improved residual network and transfer learning. Trans. Agric. Mach. 2019, 50, 364–371. [Google Scholar]

- Büyükarıkan, B. ConvColor DL: Concatenated convolutional and handcrafted color features fusion for beef quality identification. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, J.; Pi, J. Image recognition algorithm for pork freshness based on YOLOv8n. Food Mach. 2025, 41, 98–104. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Yoon, H.; Park, K.W. Robust Captcha Image Generation Enhanced with Adversarial Example Methods. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2020, 103, 879–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, H.; Park, K.W. Captcha Image Generation Systems Using Generative Adversarial Networks. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2018, 101, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.