1. Introduction

As education continues to evolve in response to new technologies and learning environments, the ability of students to adapt has become increasingly important [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Whether navigating digital classrooms, adjusting to varied instructional styles, or managing changing academic expectations, adaptability plays a vital role in student success. To support this need, adaptive learning systems have emerged as critical tools for personalizing education in dynamic settings [

5,

6,

7,

8].

Machine learning (ML) offers promising capabilities for identifying patterns in student behavior and predicting adaptability. These models can help educators proactively support students. However, their complexity often makes them difficult to interpret, particularly in education, where understanding the “why” behind a prediction is just as important as the prediction itself [

9,

10]. Educators and decision makers need transparency to make informed decisions and promote trust in automated systems [

1,

8,

11,

12].

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) methods aim to address this challenge by providing insight into how ML models make decisions. One widely used approach, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), helps to explain individual predictions by approximating the model locally using simpler interpretable models [

13,

14,

15]. While LIME is effective at the instance level, it falls short in capturing broader patterns that span groups or institutional contexts [

14,

16].

To overcome this limitation, this study introduces Hierarchical Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (H-LIME). This novel framework extends LIME by aggregating local explanations across multiple levels of a data hierarchy. With H-LIME, it becomes possible to understand how feature importance varies not only for individuals, but also across schools, locations, and education levels. The method supports:

Multi-level insightsthat go beyond the individual to reveal trends across institutions and regions;

Context-sensitive explanations aligned with the information needs of different stakeholders;

Actionable findings that can inform policy, resource allocation, and personalized interventions.

Using a real-world student adaptability dataset with institutional and demographic hierarchy, H-LIME reveals patterns that would remain hidden with instance-level methods alone. For example, while class duration may consistently affect students across contexts, the influence of financial background or internet connectivity may depend on specific subgroups. Our key contributions are summarized as follows:

Methodological Framework:We introduce H-LIME, a model-agnostic framework that aggregates local explanations across user-defined hierarchies (Institution→Location→Education Level). Crucially, we incorporate a new group-level stability metric () to detect feature polarization, distinguishing between universally irrelevant features and those with high intra-group variance.

Empirical Evaluation: We perform a rigorous comparative analysis of explanation stability, demonstrating that H-LIME explanations derived from Random Forest models are approximately 4.5 times more stable () than those from Decision Trees, thereby establishing a standard for trustworthy educational insights.

Domain-Specific Discovery: We uncover hierarchical dependencies in student adaptability, revealing that while Class Duration is a consistent global predictor, features like Financial Condition and Network Type exhibit significant variation across rural versus urban subgroups.

Practical Utility: We provide a practical deployment scenario illustrating how H-LIME’s multi-level insights can guide differentiated policy interventions, such as prioritizing digital infrastructure in rural regions versus curriculum adjustments in urban centers, that would be overlooked by standard global interpretation methods.

2. Related Works

Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) addresses the growing need to make machine learning (ML) models more transparent, especially in high-stakes domains such as education, where trust and accountability are critical [

9,

17]. As models increase in complexity, understanding their internal logic becomes challenging. Techniques like LIME attempt to solve this by approximating complex models locally using interpretable surrogates [

14].

2.1. Hierarchical Interpretability

Although LIME and SHAP provide useful explanations at the instance and global levels, they overlook hierarchical relationships often present in structured datasets, such as education systems. These methods fail to offer aggregated insights across levels like school type, location, or education stage [

14,

16]. Hierarchical interpretability bridges this gap by generating explanations at multiple levels of abstraction. Apley and Zhu’s Accumulated Local Effects (ALEs) [

18] enable global analysis while mitigating feature correlation effects, but do not support localized or group-specific interpretations. This limitation is significant in education, where student adaptability is influenced by both individual and institutional factors. Prior work on data aggregation and fairness-aware modeling [

19,

20,

21] has demonstrated the importance of summarizing data without losing key subgroup insights. Recent studies have further demonstrated the versatility of data-driven frameworks in higher education, ranging from sustainability benchmarking in Saudi Arabian institutions [

22] and assessing online learning experiences [

23] to analyzing the impact of demographic factors on organizational commitment [

24].

H-LIME addresses this by extending LIME to support multilevel aggregation. It begins with instance-level explanations and systematically groups them by hierarchical attributes (institution type, location), enabling educators and policymakers to detect patterns that are not visible at the individual level. This hierarchical structure aligns with calls for interpretable ML frameworks that balance local detail with broader applicability [

25,

26].

Hierarchical Explainability in Other Domains

While hierarchical aggregation is novel in educational data mining, similar concepts have emerged in other high-stakes domains. For instance, Hierarchical Shapley values [

27] have been utilized in high-dimensional biological data to attribute importance to correlated feature groups (gene clusters) rather than individual SNPs, thereby improving explanation stability. Similarly, in natural language processing, Hierarchical Attention Networks (HANs) [

28] have been widely adopted to provide multi-level explanations, identifying which specific words, sentences, and document sections drive a classification decision. In the medical imaging domain, frameworks like MIMIC-EYE [

29] layer clinical features (X-ray regions and ECG signals) to build interpretable clinical decision support systems. However, these methods typically rely on inherent feature hierarchies (pixel-to-object or word-to-sentence) or complex model-specific architectures. H-LIME distinguishes itself by offering a model-agnostic aggregation framework specifically designed for the user-defined, categorical nested structures (Institution→Location) that are prevalent in social and educational policy research.

2.2. XAI in Educational Applications

The integration of Machine Learning and Explainable AI (XAI) has gained traction across high-stakes domains beyond education. For instance, recent frameworks have successfully applied XAI to optimize renewable energy systems [

29,

30] and enhance clinical decision support through multi-modal deep learning [

31], highlighting the growing demand for model transparency in complex decision-making environments. XAI in education has expanded as institutions adopt data-driven tools to support student learning and adaptation. Models are increasingly being applied to predict academic performance, assess adaptability, and guide personalized interventions. However, for these predictions to be useful, they must be interpretable by human stakeholders [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. XAI methods such as LIME and SHAP have been widely used to analyze educational data. Beyond online learning and pandemic contexts, researchers have applied LIME to interpret models predicting student engagement, dropout risk, and learning outcomes across various settings [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. These studies highlight important predictors like internet access, financial stability, and self-directed learning behavior.

Although LIME provides helpful local explanations, its focus remains at the instance level. However, most educational decisions are made at higher levels, classrooms, schools, or regions. Educators and administrators often require group-level insights to inform systemic policy. Previous studies have emphasized this need for hierarchical analysis in educational XAI [

40,

42]. Some early efforts have explored hierarchical interpretability, but these are often tied to specific domains or model types, limiting their adaptability to education [

43]. As a response, H-LIME introduces a model-agnostic framework capable of aggregating local explanations into meaningful insights across multiple levels of data hierarchy. This bridges the gap between personalized feedback and institutional decision-making, offering a more holistic understanding of student adaptability.

2.3. Gaps and Opportunities in Educational XAI

Despite progress in applying XAI techniques to educational data, significant limitations remain. Most existing methods are designed for flat data structures and offer explanations only at the individual or model-wide level. As a result, they do not capture the hierarchical nature of educational systems, where insights are needed at multiple levels, students, classes, schools, and regions [

14,

40,

42,

44]. While fairness-aware aggregation and group-based modeling have been explored in other domains [

20,

45], such techniques have not been widely adapted for educational contexts. Moreover, hierarchical explainability tools that do exist are often tied to specific model architectures or constrained to particular use cases, limiting their general applicability [

43].

In educational decision-making, the ability to interpret model predictions across levels is essential for targeted interventions and resource allocation. Without hierarchical insights, stakeholders risk overlooking systemic issues or misinterpreting individual-level patterns. This gap highlights the need for general-purpose, model-agnostic frameworks that can bridge local and aggregated explanations. H-LIME responds to this challenge by enabling interpretability across hierarchical structures, offering stakeholders a more comprehensive view of feature importance at both micro and macro levels.

2.4. Comparison of XAI Techniques

Interpretable machine learning techniques such as LIME, SHAP, and ALE offer varying advantages. LIME approximates local model behavior by perturbing inputs around an instance and fitting a simple interpretable model, usually linear [

14]. It provides intuitive, instance-specific insights but lacks mechanisms for generalizing across groups or hierarchical levels. SHAP, based on Shapley values, supports both local and global explanations and is valued for its theoretical consistency [

46,

47]. However, it is computationally intensive and does not natively support aggregation across user-defined hierarchies. Similarly, ALE focuses on global effects and addresses feature correlations [

18], but does not offer instance-specific or hierarchical explanations. Additionally, standard tree-based feature importance metrics (Gini impurity or Information Gain in XGBoost) provide a global summary of feature utility but fail to capture the directionality of influence (positive vs. negative) or how these effects vary across specific subgroups.

H-LIME addresses these limitations by extending LIME to generate explanations at individual, subgroup, and global levels within structured data hierarchies (e.g., institution type, location, education level). It retains LIME’s model-agnostic nature while enabling context-aware aggregation. Beyond LIME and SHAP, recent XAI methods such as TreeSHAP [

27], ProtoDash [

48], and Anchors [

49] provide model-specific or prototype-based explanations, but typically operate on flat data and do not support hierarchical reasoning. A summary of these methods and their relative strengths is provided in

Table 1.

3. Methodology

This section outlines the general methodology used to analyze and improve student adaptability using machine learning models and hierarchical explainability techniques.

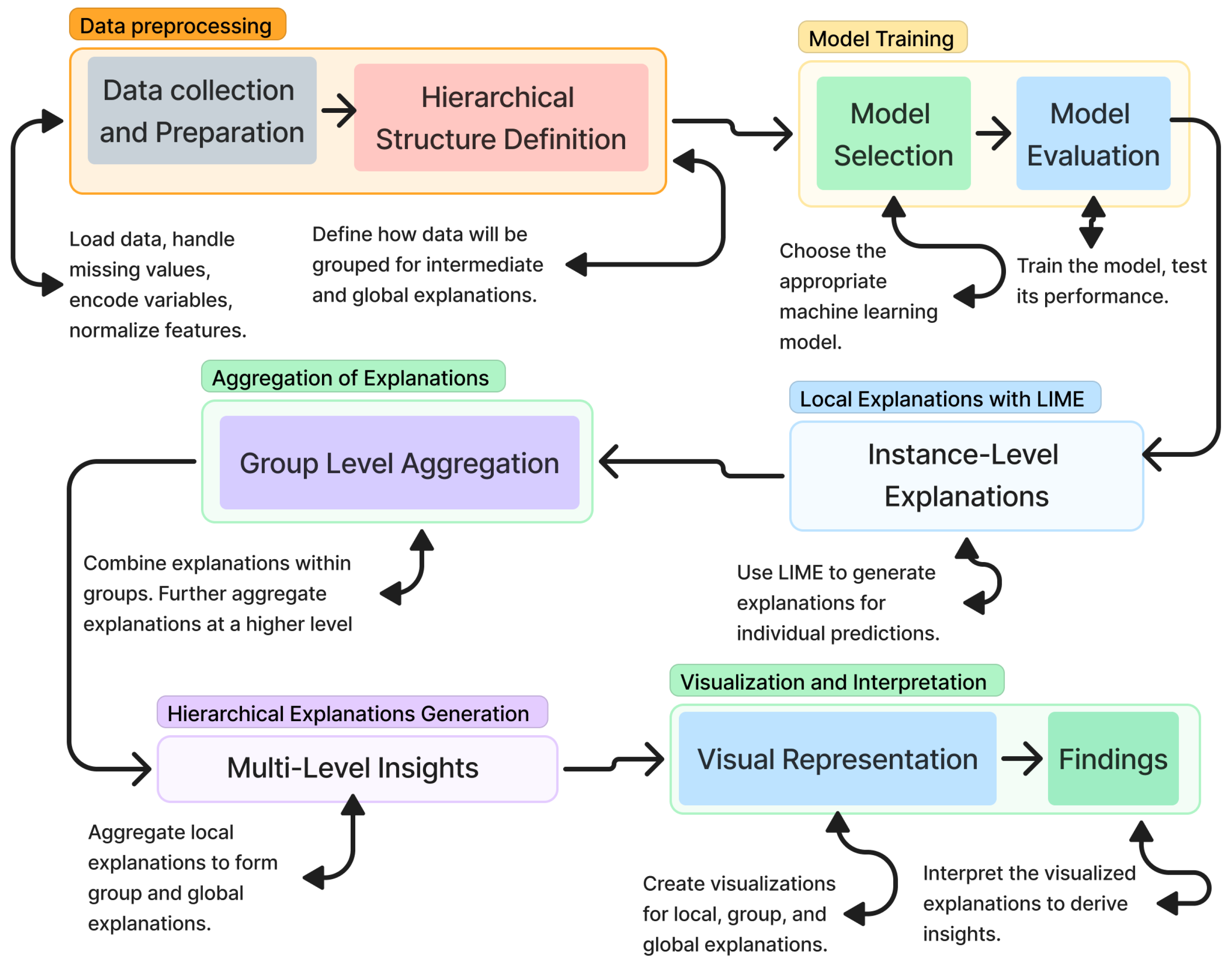

Figure 1 presents the structure of the proposed H-LIME framework.

3.1. Dataset Preparation and Hierarchical Structure

This study employed a publicly available dataset from Kaggle [

50], containing 1205 instances and 14 attributes capturing student demographics, socio-economic conditions, and learning environments. Features include Gender, Age, Education Level, Institution Type, IT Student status, Location, Load-shedding, Financial Condition, Internet Type, Network Type, Class Duration, LMS usage, and Device Type. The target variable,

Adaptivity Level, is categorized into

Low,

Moderate, and

High.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of these features, including valid counts, unique categories, and frequency statistics for the most common values.

To support hierarchical interpretability, the dataset was organized into three levels:

Institution Type: Government vs. Non-Government

Location: Urban vs. Rural

Educational Level: Primary (School), Secondary (College), and Tertiary (University)

These levels represent systemic, geographic, and curricular dimensions of the educational landscape (see

Figure 2). They enable multilevel insight into which features influence adaptability at the individual and group levels.

Before training and interpretation, the dataset was subjected to several preprocessing steps. Categorical variables such as Gender, Internet Type, and Network Type were encoded using one-hot encoding, and numerical features such as age and class duration were normalized to ensure uniform feature scaling. To address class imbalance, particularly among underrepresented groups like rural tertiary students, Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied to the training set. This preserved the original distribution in validation and test sets while ensuring adequate representation of minority classes during training.

The dataset was then split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets using hierarchical stratified sampling to maintain proportional representation across all levels (Institution Type, Location, and Education Level). Preprocessing transformations were learned from the training set and applied consistently across all splits to avoid data leakage, ensuring fair and valid performance evaluation during model training and H-LIME explanation.

To guarantee the statistical integrity of our aggregated explanations, we scrutinized the data distribution across the hierarchy’s most granular tiers (Institution→Location→Education Level).

Table 3 delineates the instance counts for the leaf nodes within the test set. Although the majority of subgroups exhibit robust sample densities, we acknowledge a pronounced sparsity in specific intersections, most notably at the tertiary level within rural jurisdictions (Non-Government Rural Universities). This scarcity provides a strong rationale for incorporating the standard deviation metric into the H-LIME framework, as it serves as a critical diagnostic for identifying instability in underrepresented strata.

3.2. H-LIME Framework Overview

The Hierarchical Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (H-LIME) framework extends traditional LIME by introducing a multilevel interpretability mechanism. While LIME provides local explanations for individual predictions, H-LIME aggregates these explanations across predefined hierarchical levels to generate both micro- and macro-level insights. The framework operates in three main stages:

Local Explanation Generation: For each test instance, LIME is applied to generate feature importance scores using a local surrogate model (typically a sparse linear regressor) around the prediction neighborhood.

Hierarchical Aggregation: Instances are grouped according to the defined hierarchical levels (Institution Type, Location, and Educational Level). Feature importances from LIME are averaged within each group to obtain subgroup-level interpretability. This allows for the detection of consistent patterns that would not be evident from single-instance explanations alone.

Global Trend Extraction: Aggregated group-level explanations are further summarized across the full hierarchy to identify features with persistent influence on predictions across the entire population. These global patterns help inform broader educational policy or curriculum interventions.

This multiscale approach enables stakeholders to trace explanations from the individual level (e.g., a student’s prediction) to institutional or regional levels (e.g., all students in rural colleges). It also addresses the limitations of flat interpretability methods, which often overlook structural context in grouped data.

Figure 3 illustrates the overall H-LIME pipeline, showing how LIME-generated explanations flow into subgroup and hierarchical aggregations. This allows for interpretable outcomes at all levels of the educational structure.

3.3. Model Training

The model training process is crucial for developing robust and accurate machine learning models capable of predicting student adaptability levels. This subsection outlines the steps involved in the selection, training, and evaluation of the various machine-learning models used in this study. Various machine learning models were selected to ensure a comprehensive analysis of their predictive capabilities and interpretability. The models chosen for this study included Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), XGBoost (XGB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Decision Tree (DT), Neural Network (NN), and AdaBoost. Each model was trained using a preprocessed training set. The training process involved fitting the models to the training data and tuning the hyperparameters using a validation set to optimize the performance.

3.4. Model Performance Metrics

To assess the predictive capability of the machine learning models, we utilized standard classification metrics: Precision, Recall, and F1-score. These metrics provide a robust evaluation of each model’s ability to correctly classify student adaptability levels, balancing the need for accuracy with the cost of misclassification.

3.4.1. Precision

Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified positive instances among all instances predicted as positive.

where:

(True Positive): The number of correctly predicted instances.

(False Positive): The number of instances incorrectly predicted.

In the educational context, high precision ensures that when the model identifies a student as “High Adaptability”, the prediction is reliable, minimizing false positives that could lead to incorrect assumptions about a student’s independence.

3.4.2. Recall

Recall evaluates the model’s ability to identify all relevant positive instances.

where

(False Negative) represents adaptable students incorrectly classified as non-adaptable. High recall is crucial to ensure that the system does not overlook students who possess high adaptability, ensuring they are correctly recognized.

3.4.3. F1-Score

The

F1-score is the harmonic mean of

Precision and

Recall.

The F1-score balances the trade-off between precision and recall. It is particularly useful in this study to ensure the model performs well across all adaptability levels without being biased by class imbalances.

3.4.4. Log-Loss Analysis and Model Selection

While precision and recall measure the model’s ability to make correct hard classifications, Log-Loss (Logarithmic Loss) evaluates the uncertainty of the model’s predictions. A lower Log-Loss indicates that the model’s predicted probabilities are closer to the actual class labels, reflecting better calibration. In this study, we employ the multi-class formulation of Log-Loss to account for the three adaptability levels (Low, Moderate, High).

where:

N is the total number of student observations, M is the number of classes (), is the binary indicator (0 or 1) denoting if the class j is the correct label for observation i, and is the predicted probability that observation i belongs to class j. A lower Log-Loss indicates that the model’s predicted probabilities are closer to the actual class labels, reflecting better probability calibration, which is essential for the stability of post-hoc explanation methods like LIME.

3.5. LIME and H-LIME

This section delves into the Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations technique and its hierarchical extension, Hierarchical Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations. These methods were employed to provide interpretability to the machine learning models used in this study, with a specific focus on the Random Forest model, which was selected for its superior explanation stability.

3.5.1. LIME

LIME explains the individual predictions of any classifier by learning an interpretable model locally around the prediction. The key idea is to perturb the input data and observe the changes in the predictions to build a simple, interpretable model that approximates the complex model locally [

14,

51], as summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 LIME Algorithm |

Input: An instance x to be explained, black-box model f, number of perturbations N, and interpretable model g (e.g., linear model).

|

- 2.

Generate Perturbations: Create N perturbed samples around x.

|

- 3.

Predict: Use the black-box model f to predict outcomes for the perturbed samples .

|

- 4.

Weight Perturbations: Assign weights to the perturbed samples based on their proximity to x. A common weighting function is the exponential kernel:

|

|

| Where: is the distance between x and , and is a kernel width parameter.

|

- 5.

Fit Interpretable Model: Fit the interpretable model g to the weighted perturbed samples .

|

- 6.

Output: The local explanation from the fitted interpretable model g.

|

For a given instance

x, LIME solves the following optimization problem:

where,

: The local explanation for the instance x, representing the interpretable model’s feature importance values.

: A candidate interpretable model selected from a class of interpretable models (G).

: A loss function measuring the fidelity of the interpretable model g in approximating the prediction of the original model f.

: A locality-aware weighting function that gives higher importance to perturbed samples closer to x.

: A complexity penalty for the interpretable model (g), ensuring simplicity and interpretability.

This equation minimizes the weighted loss between the predictions of the complex model f and the interpretable model g, with locality emphasized using . The complexity term prevents overfitting by ensuring the interpretable model remains simple. This trade-off between fidelity and simplicity makes LIME ideal for generating interpretable feature importance values for each instance.

3.5.2. H-LIME

H-LIME extends LIME by aggregating local explanations at multiple levels of a predefined hierarchy, providing insights that are both instance- and group-specific. This hierarchical approach allows for a more comprehensive understanding of model predictions across different levels of dataset hierarchy. Standard LIME explanations often rely on contrastive logic (Why Class A and not Class B?). To resolve multiclass confusion, H-LIME explicitly defines the explanation vector for a specific instance x as , containing only the coefficients corresponding to the predicted class of interest c (High Adaptability). Unlike standard outputs which might conflate class probabilities, this filtering step ensures that the subsequent aggregation represents the direct contribution of features to the specific outcome, rather than a rejection of alternative classes.

Since LIME generates sparse explanations where different instances may have different top features selected, we enforce a consistent feature space for aggregation. For any feature j that is not selected in the local explanation of an instance x, we assign a coefficient . This ensures that the global aggregation reflects the population-wide prevalence of a feature’s influence, effectively penalizing features that appear only sporadically. The complete hierarchical aggregation procedure is detailed in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 H-LIME algorithm |

Input: Dataset X with hierarchical structure, black-box model f, number of perturbations N, interpretable model g, and hierarchical levels .

|

- 2.

Local Explanations with LIME: For each instance , apply LIME to generate local explanations .

|

- 3.

Aggregation at Each Level: For each hierarchical level :

Group instances based on their values at level . Aggregate local explanations to obtain a group-level explanation .

|

- 4.

Global Explanation: Aggregation of group-level explanations to produce a global explanation that provides an overall view of the factors influencing the model predictions.

|

- 5.

Output: Hierarchical explanations offer insights at different levels of the hierarchy, and global explanation that summarizes feature importance across the entire dataset.

|

For a given hierarchical level

and

G at that level, the group-level explanation

can be defined as:

where,

: Group-level aggregated feature importance for group G at hierarchical level .

G: A group of instances within the dataset that share common characteristics, as defined by the hierarchical level .

: Specific hierarchical level in the dataset.

: The number of instances in group G.

: The local explanation for instance x.

: Denotes that the instance x belongs to group G.

This equation aggregates the local feature importance values across all instances within a group G, taking the mean to ensure group-level representativeness. The choice of mean aggregation is justified because it preserves the overall contribution of features within the group while mitigating the effect of outliers. Alternative aggregation methods (median or weighted mean) were considered, but may introduce biases, particularly in hierarchical datasets with imbalanced group sizes.

To capture the stability of feature influence within a group and to address the risk of feature cancellation (where positive and negative contributions offset each other), we compute the group-level standard deviation, denoted as

:

A low value of indicates high agreement among instances within the group, whereas a high value suggests polarization, implying that the feature exerts differing influences across subgroup members.

The global explanation

is then derived by aggregating the group-level explanations, as follows:

where,

: Global explanation summarizing feature importance across all hierarchical levels.

: Denotes that the group G belongs to hierarchical level .

: Sum of the sizes (number of groups) across all hierarchical levels.

This equation calculates the weighted mean of the feature importance values across all the hierarchical levels and their constituent groups. The normalization factor ensures that the levels with more groups do not dominate the global explanation. By combining insights across levels, this equation captures the hierarchical structure of the data, providing actionable, system-wide explanations. Hierarchical aggregation design is critical for datasets in which the feature importance varies significantly across levels.

Table 4 provides a detailed description of the variables and parameters used in the proposed framework. It includes definitions for key metrics such as true positives (TP), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), as well as mathematical notations like likelihood functions, local explanations, and hierarchical group-level explanations, ensuring clarity and consistency in the methodology.

3.5.3. Steps for Implementing H-LIME

The equations described in the H-LIME framework were implemented as part of a structured computational pipeline to generate local, group-level, and global explanations. This structured approach allows for seamless integration of various equations within the H-LIME framework. Their roles within the framework are as follows:

Local Explanations : LIME was used to generate the feature importance values for each instance. These values were used for further analysis. The Python LIME library was utilized to compute the instance-specific feature importances, which were then standardized for compatibility with subsequent computations.

Group-Level Aggregate : The aggregation equation was directly applied to compute the mean feature importance values for all instances x within a group G. This was performed for each hierarchical level . NumPy was used to efficiently perform the aggregation. For large datasets, parallel processing was leveraged to accelerate this step across hierarchical levels.

Global Explanation (): The global explanation formula was applied across all hierarchical levels, combining group-level explanations to generate a summary of feature importance. This ensured that the global explanation reflected contributions from all levels. A Python function aggregated the outputs from groups and levels, normalizing the contributions, as described previously. This step was optimized to handle large datasets.

The H-LIME framework executes the equations sequentially, starting with local explanations and moving on to group-level and global explanations. The outputs are stored in hierarchical data structures for visualization and analysis. The framework includes additional functions to validate and interpret these computations, ensuring that the results align with the model behavior and stakeholder expectations.

3.6. Assumptions in Model Development and Mathematical Formulation

The model development process and equation in this study rely on several key assumptions to ensure the applicability and interpretability of the results. These assumptions are fundamental to the methodological framework but also introduce potential limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings.

Feature Independence: LIME, and by extension H-LIME, assumes that features are independent when perturbations are applied to generate local explanations , simplifying the interpretation process. However, this assumption may oversimplify complex feature interactions, such as the correlation between socioeconomic status and technology access. To address this, aggregated insights were interpreted cautiously, and domain knowledge was used to account for potential interactions between features, ensuring meaningful and contextually accurate explanations.

Linearity in Local Models: LIME’s surrogate models assume a linear decision boundary near each instance, thus simplifying local explanations. However, in nonlinear regions, this assumption may not accurately capture the model’s behavior. To address this issue, H-LIME uses hierarchical aggregation to combine multiple local explanations across hierarchical levels. This reduces the biases introduced by the local linearity assumption, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of feature importance and context awareness.

Human-Defined Hierarchical Structure: We assume that the dataset can be meaningfully structured into hierarchical levels such as institution type, geographic location, and education level. These groupings are based on domain knowledge and follow the practice of human-defined concepts in explainable AI [

14,

25]. The utility of H-LIME relies on these definitions being relevant and interpretable for stakeholders.

These assumptions are fundamental to the methodological framework of this study and provide the necessary context for the application of H-LIME to explain student adaptability predictions. However, they also introduce potential limitations that may affect the interpretation and generalization of the findings.

3.7. Experimental Setup

For our experiments, we used a personal computer running Windows 10 Pro, equipped with a Lenovo X1 Yoga (ThinkPad) (Lenovo Group Ltd., Hong Kong, China) Core i7-6600U CPU, 16 GB of DDRAM, and 256 GB SSD. The Anaconda, Inc.-packaged Python version 3.11.5, was utilized to implement the machine learning models. The context for the computing performance of the methods employed in this study is provided by this hardware specification.

Table 5 highlights the experimental setup used in our models training.

4. Evaluation Results and Discussion

In this section, we evaluate machine learning models for predicting student adaptability levels, emphasizing performance metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and information criteria. We present hierarchical explanations using H-LIME, demonstrating their effectiveness in providing comprehensive, and actionable insights.

4.1. Models Performance Comparison

We compared the performance of the models using precision, recall, F1-score, and Validation Log-Loss. The calculated values for each model are illustrated in

Table 6. The Decision Tree model exhibits the highest F1-score (0.946), precision, and recall, indicating a strong ability to classify student adaptability levels based on hard predictions. Random Forest and XGBoost also demonstrate strong performance, with F1-scores (0.928) close to those of the Decision Tree model. KNN, Gradient Boosting, AdaBoost, and Neural Network models show moderate performance, while SVM has the lowest scores among all models evaluated.

4.2. Evaluating Random Forest Model with H-LIME

To investigate the factors shaping student adaptability, we employed the H-LIME method in conjunction with the Random Forest model. The hierarchical aggregation was conducted at three distinct levels: Institution Type, Location, and Educational Level, followed by the aggregation of group-level explanations to produce a global explanation that provides an overall view. This multi-level analysis offers insights into how various factors influence student adaptability across different detail scales.

4.2.1. Result for Local Explanation with LIME

Before applying H-LIME, we utilized LIME to interpret individual predictions. LIME helps approximate the decision-making process of complex models by locally fitting an interpretable surrogate model. To validate the trustworthiness of these local approximations, we quantified the fidelity of the surrogate linear models via the coefficient of determination (). The analysis yielded a mean of across the test set, suggesting that the generated explanations offer a faithful reflection of the Random Forest’s complex decision dynamics within the perturbed local neighborhoods.

Figure 4 shows the explanation generated by LIME for a student whose adaptability level was predicted as “

High”

with 100% confidence. However, due to the behavior of LIME in multiclass settings, the explanation plot contrasts the predicted class (“High”) with an alternative class, in this case, “

Moderate”. Thus, the plot visualizes how each feature contributes

for or against the “Moderate” class, rather than directly explaining the “High” prediction.

The model confidently predicted “High” adaptability (probability = 1.00), while the probabilities for “Moderate” and “Low” were 0.00. This indicates strong model certainty in the chosen class.

By examining the feature contributions away from “Moderate”, we infer the support for the “High” class as follows:

Class Duration (0): This has a strong negative influence on “Moderate,” suggesting that lack of scheduled class duration is less aligned with that class, and may contribute more to a “High” or “Low” classification.

Self LMS Usage (No): Shows a notable negative effect on “Moderate”, reinforcing the importance of self-driven LMS engagement for adaptability.

Education Level (School) and Age (1–5): These features contribute negatively to “Moderate”, indicating their relevance in separating age and education-level subgroups.

Network Type (2G): Slight negative contribution, highlighting digital infrastructure as a factor in adaptability.

Although the visualization contrasts with “Moderate”, the inverse logic reveals which features pull the model’s decision away from that class and toward “High”. This indirect interpretability underscores the limitations of LIME in multiclass tasks, where it does not directly explain why the predicted class was selected.

Note: H-LIME resolves this issue by allowing aggregation of explanations for the actual predicted class across hierarchical groups, rather than relying on contrastive logic.

4.2.2. Institution Type Aggregation

Figure 5 presents feature importance aggregated separately for government and non-government institutions. The results highlight systemic differences in factors influencing adaptability.

Government Institutions (

Figure 5a): Older students (e.g., Age 21–25), access to mobile data, and 2G network usage appear as positive contributors to adaptability, suggesting that older learners benefit from flexible digital resources. In contrast, rural location and reliance on mobile devices negatively influence adaptability, emphasizing the need for infrastructure investment and access to better hardware in underserved regions.

Non-Government Institutions (

Figure 5b): Negative contributors include mid-level financial condition and gender (boys), indicating socio-economic and gender-related challenges. Technological features such as 4G access and age groups show weaker associations, suggesting that while tech access helps, it does not fully mitigate deeper equity gaps. Support strategies like targeted financial aid and inclusive mentoring may be more effective in this context. H-LIME enables actionable insights into institutional disparities, supporting policies that align interventions with structural and demographic needs.

4.2.3. Location-Based Aggregation Within Institutions

Figure 6 shows how feature importance varies by location (urban vs. rural) within institution types.

(a) Government–Urban (

Figure 6a): Younger students (Age 21–25) show lower adaptability, while higher education level (School) contributes positively. Targeted mentorship and educational support may help address early-stage challenges.

(b) Government–Rural (

Figure 6b): Education remains a key positive factor, but rural students face greater infrastructural challenges. Investments in teaching quality, scholarships, and rural digital access are essential to mitigate these gaps.

(c) Non-Government–Urban (

Figure 6c): Technological constraints like 4G access appear less influential, suggesting better infrastructure. Digital literacy and engagement initiatives could further support younger learners.

(d) Non-Government–Rural (

Figure 6d): Barriers are more pronounced. Younger students and those with low LMS engagement are most affected. Personalized learning and increased digital platform use can help improve outcomes.

Across all subgroups, educational attainment consistently drives higher adaptability, while rural environments and younger learners face greater risks. These insights support policies focused on infrastructure equity, early-stage learning support, and LMS engagement.

4.2.4. Educational Level Aggregation Within Urban Government Institutions

Figure 7 shows how adaptability factors differ across primary (school), secondary (college), and tertiary (university) education levels within urban government institutions.

(a) Primary Level (

Figure 7a): A low score for Education Level_School and negative contributions from LMS usage and mobile devices indicate difficulties younger students face with self-learning and technology engagement. Improving early education quality and digital literacy at this level is crucial.

(b) Secondary Level (

Figure 7b): A strong primary education background (Education Level_School > 1.10) positively affects adaptability. Class duration and rural location also influence outcomes, suggesting the need for structured learning and better rural infrastructure.

(c) Tertiary Level (

Figure 7c): Flexible class schedules emerge as the most significant positive predictor, especially for older students. However, early education gaps continue to be associated with reduced adaptability, emphasizing the long-term importance of foundational learning. Younger university students may show higher adaptability with targeted academic support. The findings emphasize tailoring interventions to each educational stage: reinforcing foundational education, adapting schedules to student maturity, and investing in equitable technological access.

4.2.5. Global Feature Importance

Figure 8 presents the global feature importance derived from H-LIME, summarizing adaptability predictors across all hierarchical levels. The strongest negative contributor is Education Level_School, indicating foundational gaps in early education. Socio-economic (e.g., Financial Condition_Rich) and gender-based (e.g., Gender_Boy) disparities also reduce adaptability, highlighting the need for inclusive support strategies. Poor digital access (e.g., Network Type_2G, Device_Mobile) consistently impairs adaptability, reaffirming infrastructure’s role.

Age-related variation shows that students aged 21–25 are particularly at risk, potentially due to academic or career transitions. Students in rural areas (Location_No) and government institutions face structural disadvantages, while non-IT students demonstrate lower adaptability, underscoring the value of technical literacy. In contrast, higher education levels (College, University) show milder negative effects, suggesting improved resilience and access over time. This global view reinforces the importance of addressing early-stage inequalities while supporting digital access and skill development across the educational spectrum.

4.2.6. Comparison with Related Studies

Table 7 presents a comparison of the proposed H-LIME framework with recent studies on student adaptability prediction [

8] and explainable AI in education [

52]. The comparison highlights predictive performance, interpretability scope, and methodological contributions.

As shown in

Table 7, H-LIME demonstrates robust performance with an F1-Score of 0.93, making it highly competitive with state-of-the-art approaches. While Nnadi et al. [

8] achieved a marginally higher F1-Score (0.94) using a similar Random Forest architecture, their study utilized standard “flat” XAI methods (SHAP, LIME, ALE). These techniques provide excellent instance-level or global summaries but fail to capture the structural dependencies inherent in educational data, such as institution-specific or regional trends.

Similarly, Guleria et al. [

52] focused on individual predictions for career counseling but lacked mechanisms for global or group-level aggregation. The key advantage of H-LIME lies in its

hierarchical interpretability. By bridging the gap between local explanations and global trends, H-LIME offers unique "middle-layer" insights, such as identifying that digital infrastructure gaps are critical in rural subgroups but less relevant in urban ones, which remain hidden in the flat analysis models used by related studies.

4.2.7. Interpretability in Practice

Beyond these quantitative metrics, we also qualitatively compared LIME and H-LIME. Although LIME provides individual explanations, these are often fragmented and vary across similar instances. H-LIME, by aggregating local explanations into hierarchical levels, reveals stable group-specific patterns (e.g., how feature importance differs by institution type or education level). This structure enables stakeholders to reason across individual, group, and global scales, facilitating more informed interventions in educational settings.

5. Limitations and Practical Implications

While H-LIME offers detailed, multilevel explanations that support educational decision-making, several limitations and usability concerns remain.

Usability: Non-expert users may find hierarchical outputs overwhelming, especially when concise summaries are preferred. There’s a trade-off between interpretability and specificity; while H-LIME provides granular insights, they may obscure the overall model logic.

Technical Limitations: H-LIME depends on human-defined hierarchies, making it sensitive to poorly structured or imbalanced groupings. Like LIME, it assumes feature independence and local linearity, which may oversimplify complex relationships. Furthermore, this independence assumption may introduce bias when aggregating interlinked educational features (Financial Condition correlating with Device Type). H-LIME aggregates the attributed influence, but if the local surrogate assigns weight to a proxy feature due to collinearity, this misattribution will persist in the group summary.

To address the risk of feature cancellation, where positive and negative contributions within a group offset each other, we incorporated the standard deviation metric () into the aggregation logic. While mean aggregation alone might obscure polarized features (approaching zero), the inclusion of allows H-LIME to distinguish between truly irrelevant features and those with high intra-group variance, ensuring that highly polarized features are explicitly signaled. Although interaction-aware methods like Shapley values (SHAP) offer theoretical advantages for nonlinear features, they are computationally intensive and often produce dense explanations that are harder for non-technical stakeholders to interpret than LIME’s sparse linear approximations. Future work will explore efficient Hierarchical Shapley implementations to address this limitation.

Practical Use: H-LIME provides actionable insights at multiple levels. For example, identifying financial hardship in rural schools can justify aid programs, while recognizing digital access gaps can guide infrastructure upgrades. A hypothetical deployment at a rural tertiary institution showed how institution-type, location, and education-level explanations guided interventions in financial aid, connectivity, and curriculum design, ultimately improving adaptability and satisfaction. These insights reinforce H-LIME’s utility for educators and policymakers seeking scalable, interpretable frameworks to support student-centered strategies.

5.1. Assumptions About Hierarchical Structure

The hierarchical structure of the framework may not accurately reflect the underlying relationships in the data. This could introduce bias or lead to overfitting. Additionally, aggregating explanations across levels may skew the results if certain groups dominate the dataset, leading to biased conclusions that may not be generalizable.

It is important to note that the hierarchical structure (Institution→Location→Education Level) serves as a user-defined analytical lens rather than a rigid model constraint. Because H-LIME aggregates strictly from the instance level upward, the underlying feature contributions for a specific student remain constant regardless of the aggregation order. Consequently, changing the hierarchy order, such as grouping first by Location and then by Institution Type, does not alter the numerical validity of the insights, but instead shifts the policy focus. This flexibility ensures that the findings are not artifacts of a static sequence, but rather adaptable perspectives that enable stakeholders to prioritize different dimensions (addressing regional infrastructure gaps before institutional differences).

5.2. Scalability Challenges

Although the multilevel aggregation approach of H-LIME can increase computational complexity, especially for larger datasets or real-time applications, the following scalability challenges were identified:

Computational Overhead: Generating local explanations for individual instances using LIME and aggregating them across multiple hierarchical levels requires substantial computational resources. This complexity increases only as the dataset grows, and the number of hierarchical levels within the data increases.

Real-Time Applicability: In dynamic educational applications that require rapid decision-making, the time required for perturbations, model predictions, and hierarchical aggregation may exceed acceptable thresholds.

To quantify the actual computational overhead, we performed a runtime benchmark comparing the base LIME generation process against the H-LIME aggregation step. The results indicate that while generating LIME explanations required an average of 0.129 s per instance, the hierarchical aggregation process for the entire test set required only 0.016 s. Thus, the aggregation step introduces negligible latency (<1% of total runtime), confirming that the primary bottleneck remains the underlying LIME generation rather than the hierarchical summarization.

5.3. Mitigation Strategies for Scalability

To address the scalability challenges and enhance the applicability of H-LIME, the following strategies are proposed:

Parallel Processing: Employing parallel computing frameworks can significantly expedite the generation and aggregation of explanations, thereby enhancing the suitability of the framework for larger datasets.

Sampling Techniques: Leveraging representative sampling at each hierarchical level can reduce the computational load without compromising the integrity of insights.

Incremental Aggregation: Adopting an incremental approach to dynamically aggregate explanations as new data arrive can enhance the practicality of H-LIME for real-time applications.

5.4. Broader Applicability and Impacts of H-LIME

One of the key strengths of the H-LIME framework is its inherent adaptability, allowing for the integration of additional attributes into the hierarchical structure. While this study focuses on three specific dimensions, Institution Type, Location, and Education Level, H-LIME is designed to accommodate a diverse range of features across various domains.

For instance, in healthcare, the framework could be applied to hierarchical factors such as patient age groups, hospital departments, and geographic regions to evaluate clinical outcomes. Similarly, environmental studies could leverage hierarchical layers like climate zones, seasonal variations, and pollution levels to derive actionable insights. In the marketing domain, H-LIME could evaluate customer engagement patterns across regional markets and product categories. This flexibility ensures that H-LIME can be adapted to datasets of varying complexity, establishing it as a versatile tool for researchers seeking interpretable, multi-level insights in high-stakes fields.

Societal and Operational Impact

Beyond its domain versatility, H-LIME offers significant operational utility by bridging the gap between technical model outputs and human decision-making. By translating complex, non-linear model behaviors into hierarchical summaries, the framework democratizes access to AI insights, enabling non-technical stakeholders, such as school administrators, public health officials, or business strategists, to interpret data without requiring deep machine learning expertise.

Furthermore, H-LIME enhances accountability in high-stakes applications. By explicitly quantifying the stability and variance of features within subgroups (via the standard deviation metric, ), the framework prevents the ecological fallacy, where broad aggregate statistics might otherwise mask disparities affecting minority populations. This capability is critical for fostering fairness and trust, as it compels decision-makers to acknowledge the heterogeneity of the populations they serve rather than relying on oversimplified global averages.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

This study introduced the Hierarchical Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (H-LIME) framework, an innovative extension of the widely used LIME technique, aimed at addressing the need for more comprehensive interpretability in educational machine learning models. By aggregating local explanations across different hierarchical levels, such as institution type, location, and educational level, H-LIME provides a multi-layered understanding of the factors influencing student adaptability. Crucially, this study introduced a group-level stability metric () to distinguish between universally irrelevant features and those with high intra-group variance, ensuring that polarized predictors are explicitly identified.

Our findings demonstrate that H-LIME not only maintains the interpretability of individual predictions but also offers valuable insights at higher levels of aggregation. Empirical evaluation confirmed the robustness of the framework, with the Random Forest model yielding explanations that were approximately 4.5 times more stable than those of decision trees. The application of H-LIME revealed significant predictors of student adaptability, such as educational level and class duration, which retained their importance across hierarchical contexts. Our results align with and extend existing research by providing a more detailed and context-aware understanding of adaptability in educational settings.

This research contributes valuable knowledge to the field of educational data science, paving the way for more effective and personalized educational strategies. Future research will focus on:

Validating H-LIME’s utility through longitudinal pilot studies with educational institutions to test its effectiveness in guiding real-world interventions and refine the framework based on stakeholder feedback.

Optimizing computational efficiency using parallel computing to support real-time dashboards for educators.

Addressing feature interactions by exploring Hierarchical Shapley values (H-SHAP) to capture non-linear dependencies that linear surrogates might miss.

Expanding the application of H-LIME to other high-stakes domains, such as healthcare, finance, cybersecurity, and workforce development, where hierarchical data structures are prevalent.

These efforts aim to establish H-LIME as a robust and accessible tool for driving data-informed educational strategies and improving student adaptability.