Featured Application

This study informs the design of virtual environments for therapeutic and emotionally meaningful conversations delivered through VR platforms. The findings show that nature-themed environments, particularly virtual blue spaces, can enhance users’ comfort and calmness when disclosing personal experiences. These results can guide developers of VR counselling systems, digital mental-health tools, and conversational-agent platforms in selecting or tailoring virtual environments that promote psychological safety and ease of communication.

Abstract

Virtual reality (VR) offers new opportunities for delivering psychologically meaningful conversations in digitally mediated settings. This study examined how environmental designs influence user experience during emotionally relevant self-disclosure. Fifty university students completed a within-subjects experiment in which they engaged in a structured positive and negative self-disclosure task across four immersive environments (seaside, garden, urban, and sci-fi). After each interaction, participants rated six experiential dimensions relevant to therapeutic communication: comfort, calmness, pleasantness, focus, privacy, and perceived overall suitability for psychological therapy. Repeated-measures analyses showed that nature-themed environments were rated more positively than non-nature environments across all dimensions. Although the seaside and garden environments did not differ in overall composite ratings, the seaside setting was most frequently preferred for comfort, calmness, and pleasantness in participants’ final rankings. These findings demonstrate that virtual environment design meaningfully shapes users’ emotional and interpersonal experience in VR, highlighting the value of nature-based environments for VR counselling systems and digital mental-health applications.

Keywords:

self-disclosure; virtual reality; green spaces; blue spaces; environment; therapy; comfort; privacy; nature 1. Introduction

The delivery of psychological and interpersonal support services increasingly incorporates digital communication modalities, such as video, phone, and text-based telehealth [1,2,3]. Although these modes increase accessibility, they can lack many of the embodied and environmental cues that support emotional presence, rapport, and comfort during sensitive conversations [4,5,6]. Virtual Reality (VR) introduces an interaction setting that differs in a crucial way, placing users inside immersive environments in which both the social and spatial aspects of the experience can be deliberately crafted. In therapeutic communication contexts, this means that VR can potentially influence users’ emotional experience not only through avatar-mediated interaction but also through the design features of the surrounding virtual environment [7,8,9].

While emerging work has examined VR as a medium for self-disclosure and teletherapy-relevant communication [9,10,11,12,13], almost no research has compared how different specific VR environmental designs influence users’ psychological experience during emotionally meaningful self-disclosure interactions. This represents a critical gap for the field of human–computer interaction: If VR is to support future teletherapy, telepresence, workplace wellbeing, or AI-mediated conversational systems, designers must understand how different categories of virtual environments facilitate or hinder comfort, focus, privacy, and emotional openness. It should be noted that the virtual environments examined in the present study were stylised rather than fully photorealistic, reflecting the design characteristics of contemporary multi-user VR communication platforms such as VIVE Sync.

1.1. Nature vs. Non-Nature Environments for Emotionally Meaningful Interaction

Research in real-world contexts shows that natural green spaces (e.g., forests, gardens, parks) and blue spaces (e.g., seaside, rivers, lakes) reliably promote calmness, improve affect, and support recovery from stress [14,15,16,17,18]. These effects are commonly explained by restoration theories such as Attention Restoration Theory [19] and Stress Reduction Theory [20], which propose that natural settings reduce attentional demands and evoke a sense of safety or ease [21]. Even brief exposure to natural scenes can downregulate stress physiology [22,23,24] and shift individuals into more mindful or present-centred states [25].

A substantial body of counselling and psychotherapy research similarly shows that natural outdoor environments shape core therapeutic processes, influencing client comfort, emotional engagement, and the quality of the therapeutic relationship [26,27,28,29]. Meta-analytic and comparative studies indicate that outdoor or nature-assisted therapy can yield stronger reductions in psychological distress, anxiety, and stress than equivalent treatments delivered indoors [26,30,31]. Specific intervention studies echo this pattern. For example, group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) delivered in a forest environment led to higher recovery rates for major depressive disorder than the same CBT delivered in a hospital room [25,32]. Clients also report preferring outdoor formats such as walk-and-talk therapy because they feel less intimidating and more conducive to open conversation than conventional indoor counselling rooms [33,34].

These therapeutic advantages are linked to specific environmental mechanisms. Natural settings reduce interpersonal pressure, soften power dynamics, and create a neutral shared space that feels less clinical and less evaluative than traditional consulting rooms [27,28,35,36]. Outdoor environment can also facilitate emotional openness through sensory regulation, increased comfort, and opportunities for movement, creating a sense of grounding and safety that supports rapport and smoother interpersonal communication [26,29,37]. Collectively, this work shows that environmental context can shape clients’ comfort, focus, and willingness to disclose, highlighting the importance of examining how virtual environments influence emotionally meaningful interaction in VR.

Immersive VR nature environments show similar benefits. They reduce stress and negative affect, increase relaxation, and improve mood across a range of populations [38,39,40,41,42]. Studies comparing virtual nature with urban or artificial VR settings consistently find stronger affective and restorative responses in nature-based environments [38,39]. These effects are associated with design elements such as open spatial layouts, naturalistic visuals, appropriate lighting, and realistic environmental sounds, which enhance immersion and emotional ease [43,44,45]. VR nature therefore offers a controlled yet experientially rich setting that can support calmness and emotional regulation, making it well suited to emotionally meaningful communication.

1.2. VR Self-Disclosure as a Paradigm for Emotionally Meaningful Interaction

Given that VR environments can influence affective and relational processes in similar ways to real-world settings, it is important to consider how VR is currently used to study emotionally meaningful interpersonal interaction. Self-disclosure tasks have become an increasingly common methodological tool in VR research because they provide a structured way to elicit emotionally relevant interpersonal communication. Prior studies have used self-disclosure conversations to evaluate communication quality, comfort, rapport, and interaction preferences within VR and compared them with other communication modalities [9,10,11,12,13]. For example, Rogers et al. [13] examined user experience disclosing personal experiences across VR (within a virtual garden environment), text, and video modes of communication. Their participants were asked to indicate which communication mode they would most prefer for psychological therapy, and while most preferred video chat, a substantial proportion (~20%) indicated VR chat.

Self-disclosure tasks are particularly valuable for Human–Computer Interaction research because they allow VR communication systems to be evaluated under emotionally meaningful conditions rather than basic task-based interactions. As VR begins to support activities that involve personal sharing, including remote counselling, peer support, coaching, and interactions with conversational agents, it becomes essential to understand how system design shapes users’ emotional comfort, sense of privacy, and overall interaction quality. Using self-disclosure as an evaluation paradigm provides a controlled and replicable way to approximate the relational demands of real-world interpersonal communication, enabling researchers to investigate how specific design choices influence emotionally sensitive user experiences in VR.

1.3. The Present Study

The present study examined how different categories of virtual environments shape users’ psychological experience during an emotionally meaningful self-disclosure interaction. Although VR self-disclosure studies have evaluated rapport and comfort, they have concentrated on communication modality and avatar design, leaving the role of the VR environment largely unexamined [9,10,11,12,13]. Consequently, little is known about how specific virtual settings influence the experiential qualities that underpin counselling-relevant conversation.

Although natural environments generally produce more positive affective responses, this does not guarantee uniform preference across users or across the specific demands of an emotionally meaningful interpersonal task. VR design increasingly requires understanding the full range of experiential preferences. Some individuals may prefer more conventional or structured settings (e.g., offices), while others may find highly artificial spaces less distracting or more private. Because self-disclosure involves comfort, privacy, attention regulation, and interpersonal ease, it is not self-evident that natural environments will be optimal for all users. Testing this contrast therefore provides both a theoretically grounded prediction and an opportunity to examine individual variability in environmental preferences for emotionally meaningful VR interaction, an issue that has not been addressed in prior work.

To address this gap, in the present study, participants engaged in a brief self-disclosure conversation within four fully immersive VR environments: two nature-themed settings (garden and seaside) and two non-nature settings (urban and sci-fi). After each interaction, participants rated their experience on dimensions relevant to emotionally meaningful communication, including comfort, calmness, perceived privacy, focus, and overall suitability for therapeutic conversation. Based on research demonstrating the affective and relational advantages of natural environments in real-world talk-based therapeutic contexts [26,29,30,34], along with evidence showing calming and restorative effects of VR nature environments [38,39], we hypothesised that the nature-themed VR environments would be appraised more positively than the non-nature VR environments. This study therefore provides an initial empirical test of how VR environmental design influences user experience during counselling-relevant interpersonal interaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

A within-subjects design was used in which each participant completed a brief self-disclosure conversation within four immersive VR environments. Two environments were nature-themed (garden and seaside), and two were non-nature environments (urban and sci-fi). Environment order was individually randomised. After each conversation, participants rated six experiential dimensions: comfort, calmness, perceived privacy, focus, pleasantness, and perceived suitability of the environment for psychological therapy. These ratings provided both environment-specific analyses and composite environment appraisal scores. An a priori power analysis for within-subjects comparisons (effect size d = 0.50, α = 0.05, power = 0.80) indicated a target sample of ~50 participants, consistent with sample sizes in similar VR self-disclosure studies.

2.2. Participants

Fifty undergraduate psychology students participated for course credit (31 female, 19 male; M age = 30, SD age = 12, age range = 18–64). The age distribution reflects the composition of the psychology participant pool at the university, which includes both school-leavers and a substantial proportion of mature-age students. All participants had normal or corrected vision using contact lenses. Participation was voluntary, and all data were collected anonymously using coded identifiers. The study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Committee prior to study commencement.

2.3. Materials—Virtual Environments and Hardware

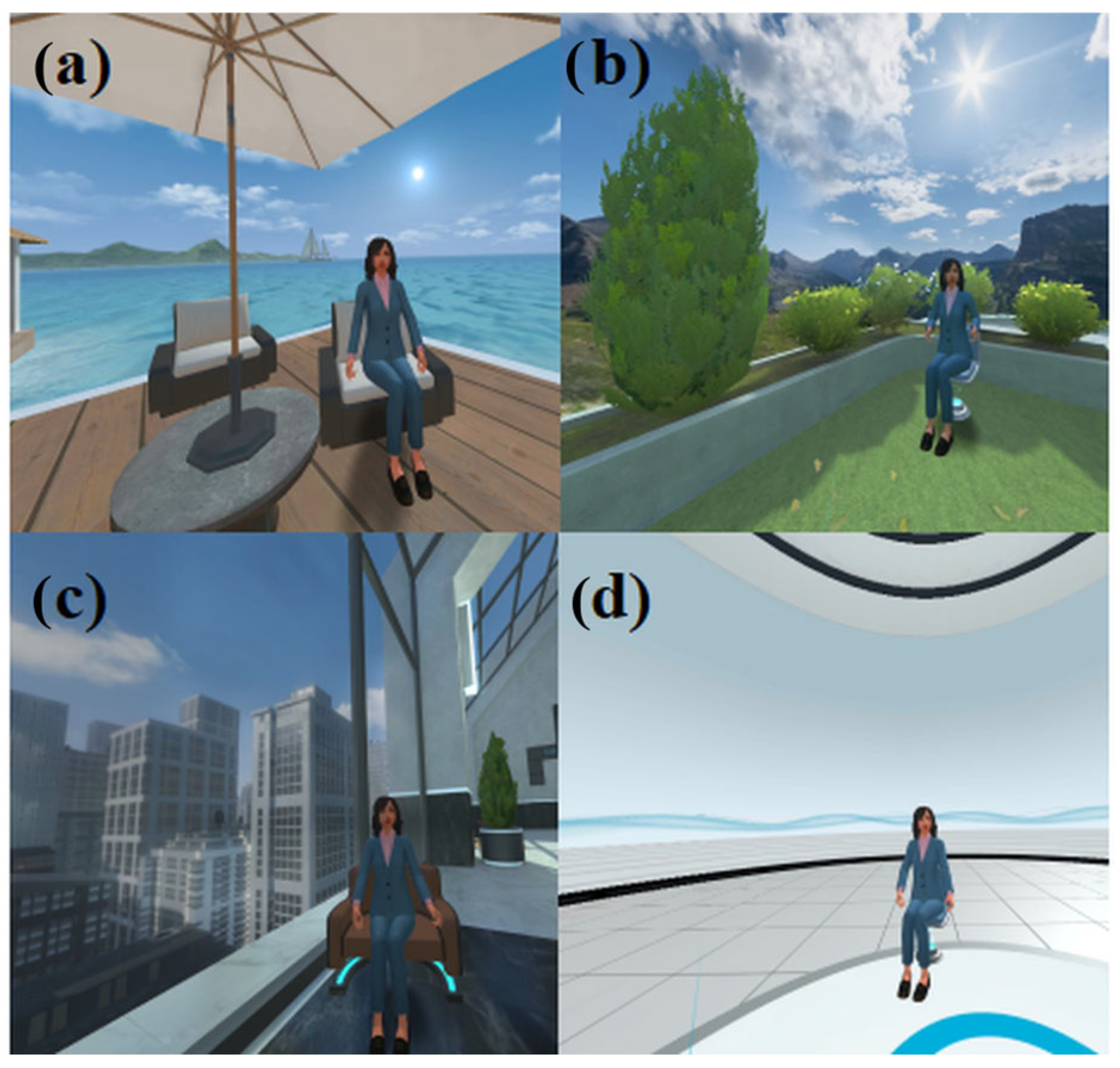

All interactions were conducted via HTC VIVE Sync, a multi-user VR communication platform supporting full-body avatars, spatial audio, and a selection of pre-built environments (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan City, Taiwan). Participants wore a VIVE Focus 3 headset, while the interviewer wore a second VIVE Focus 3 headset with eye tracking enabled to support more natural avatar behaviour (HTC Corporation, Taoyuan City, Taiwan). Both devices provide 5K resolution (2448 × 2448 pixels per eye), a 120-degree field of view, and a 90 Hz refresh rate. The four environments comprised a coastal seaside setting (Figure 1a), a green garden setting (Figure 1b), an urban office interior (Figure 1c), and a sci-fi interior within a spaceship (Figure 1d). These environments were selected to represent categories of virtual spaces commonly used or proposed in VR communication systems, including naturalistic, everyday non-naturalistic, and highly artificial settings.

Figure 1.

Four virtual environments used in the study: (a) seaside coastal setting, (b) green garden setting, (c) urban indoor office setting, and (d) sci-fi setting. All images were taken from the perspective of a participant, looking at the experimenter’s avatar.

In addition to their visual characteristics, the virtual environments included immersive sensory features inherent to the VIVE Sync platform. While VIVE Sync does not provide user-configurable sound profiles during a session, scene-specific ambient audio cues were present at low intensity in some environments (e.g., slight background sound consistent with a natural setting in the seaside and garden scenes and minimal environmental sound in others). Lighting within each environment was fixed and could not be adjusted independently; colour temperature and intensity were therefore as provided by the platform and not explicitly matched across environments. All environments included mild ambient animation (e.g., moving water, subtle vegetation motion, or lighting elements), but no interactive or task-relevant animations were present. Consequently, environments differed primarily in thematic and sensory context rather than interactivity or functional affordances.

2.4. Materials—Avatar Selection and Standardisation

Participants chose from a set of pre-made VIVE Sync avatars. The interviewer (a female researcher in her early twenties) used the same pre-made female avatar for all interactions and remained in a fixed position within each environment to ensure standardisation. The interviewer’s positioning was matched as closely as possible across all four environments by maintaining equivalent interpersonal distance and body orientation for every conversation. The interviewer’s avatar was positioned approximately 1.2 m from the participant, which falls within the range of interpersonal distances commonly used in VR research examining personal space and social interaction [46,47]. This standardisation ensured that variation in participants’ ratings could be attributed to environmental characteristics rather than differences in avatar appearance or experimenter behaviour.

2.5. Materials—Self-Disclosure Prompts and Questionnaires

Prior to entering VR, participants wrote brief descriptions of four positive and four negative experiences, for a total of eight experiences. During each VR interaction, the interviewer invited disclosure using the verbatim prompts: “Please describe the negative/positive experience you wrote down” and “How did that experience make you feel?” This level of disclosure is consistent with prior VR self-disclosure research, which typically uses brief, structured personal descriptions to ensure standardisation across participants and conditions [9,10,11,12,13]. After removing the headset, participants completed a six-item post-condition questionnaire assessing comfort, calmness, pleasantness, perceived privacy, ability to focus, and perceived suitability of the environment for psychological therapy. Each item used a four-point response scale ranging from: (1) Not at all, (2) A little bit, (3) Quite a bit, and (4) A lot. After completing all four environments, participants ranked the environments from most to least preferred for each experiential dimension and provided basic demographic information.

After the two self-disclosures made within a virtual environment, the participants were specifically asked, ‘Please rate your agreement with the below statement regarding your feelings when in the virtual environment while talking about your negative and positive experiences’ for the following items:

- I felt comfortable in the environment.

- The environment had a calming/soothing effect on me.

- I felt the environment was pleasant to look at.

- In the environment, I felt a sense of privacy for disclosing my experiences.

- I felt the environment helped me focus on the task of disclosing my experiences.

- I think this environment would be well suited for psychological therapy.

The item assessing perceived suitability for psychological therapy was intended to capture participants’ subjective appraisal of how supportive and appropriate each environment felt for a therapy-like conversation, rather than clinical efficacy or treatment preference. Although participants’ interpretations of what therapy “should” look like may vary based on prior therapy experience or personal comfort with different environments, perceived environmental suitability remains a meaningful indicator of acceptability and psychological safety, which are central to engagement in counselling and other emotionally sensitive interactions.

In a final ranking task after experiencing all environments, participants were asked, ‘Please rank order the environments (1 = best to 4 = worst) regarding the following statement:’ Each of the statements presented above was ranked by the participants in this fashion. All surveys were administered using Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA).

2.6. Procedure

Participants were welcomed individually by a research assistant and provided written information and consent forms. They then completed a short preparatory task in which they wrote down several personal positive and negative experiences to be used during subsequent VR conversations (i.e., four positive and four negative experiences, for a total of eight experiences). For each experience, they wrote down: (1) what the event was, including when and what happened, and (2) how it made them feel. While the participant prepared these responses, the interviewer calibrated the eye tracking of the experimenter’s headset and entered the first assigned environment.

The research assistant fitted the participant with the VR headset and ensured they were comfortable and stationary. Once the participant entered the virtual environment and located the interviewer’s avatar, the assistant left the room to enhance perceived privacy during the disclosure task. In each environment, the participant described one negative and one positive experience, always in that order, to conclude each interaction on a positive note. Interaction length was guided to remain consistent across environments. After each VR conversation, the headset was removed, and the participant completed the post-condition questionnaire before moving to the next environment. The research assistant was on hand to assist with removing and putting back on the headset throughout the session. After all four environments had been completed, participants completed the final ranking task and demographic items, were debriefed, and received course credit.

Although the research assistant left the room during each VR conversation, the experimenter remained physically nearby in an adjacent space throughout the session for safety and procedural control. This design constraint may have anchored participants’ perceptions of privacy at a broadly similar baseline across conditions. In addition, the brief and highly structured nature of the disclosure task limited attentional demands, which may have reduced the extent to which environmental differences could meaningfully influence focus ratings.

Each session followed the same sequence: (1) information and consent, (2) generation of four negative and four positive personal experiences, (3) entry into the first VR environment and completion of the initial self-disclosure task (one negative and one positive disclosure) followed by immediate experiential ratings, (4) repetition of this disclosure–rating sequence for the remaining three VR environments, (5) completion of the end-of-session survey, and (6) debriefing. The order of the four VR environments was randomised across participants.

2.7. Data Analysis

Because the six experiential ratings were moderately intercorrelated within each environment, composite appraisal scores were computed to represent overall appraisal of each environment. Therefore, composite scores were created for each environment, including the seaside (inter-item correlation = 0.42, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.82), garden (inter-item correlation = 0.47, Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.84), urban (inter-item correlation = 0.50, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86), and sci-fi (inter-item correlation = 0.59, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) environments. Composite appraisal scores were calculated as the mean of the six experiential item ratings for each environment and were not standardised prior to analysis.

These composite scores represent an analysis of general overall participant appraisal of the environments and are used to examine differences in participant preferences between the four VR environments. They will be referred to as ‘composite appraisal scores’ throughout the text. Composite scores were analysed using repeated-measures ANOVA with Huynh–Feldt corrections where necessary. Given the ordinal nature of the item-level ratings, additional Wilcoxon signed-rank follow-up tests were conducted to examine dimension-specific differences. Exploratory checks comparing first-exposure versus later-exposure ratings revealed no systematic order-related trends across environments or experiential dimensions; order was therefore not included in the final analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Post-Interaction Ratings

Descriptive statistics for the ratings made immediately after each interaction are presented in Table 1. A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing the composite appraisal scores across environments showed a significant overall effect of environment, F(2.62, 128.24) = 54.18, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.53 (Huynh–Feldt corrected due to violation of sphericity, ε = 0.87, p = 0.01). Follow-up paired-samples t-tests indicated that all environments differed significantly from one another (all p ≤ 0.001, all d ≥ 0.48) except for the seaside versus garden comparison, which was non-significant (p = 0.98, d = 0.01). These findings show that the seaside and garden environments received higher overall appraisal ratings than the urban and sci-fi environments, with no meaningful difference between the two nature settings. The urban environment was also rated more positively than the sci-fi environment.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations (SD) for participants’ experiential ratings made immediately after disclosing one negative and one positive personal experience within each virtual environment.

To examine each experiential dimension individually, additional Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were conducted. As these analyses closely mirrored the pattern observed in the composite scores, they are reported in a Supplemental Table (Table S1). The only departures from the composite pattern were that the urban and sci-fi environments did not differ significantly on the privacy or focus ratings. The seaside environment also did not differ from the urban or sci-fi environments in focus.

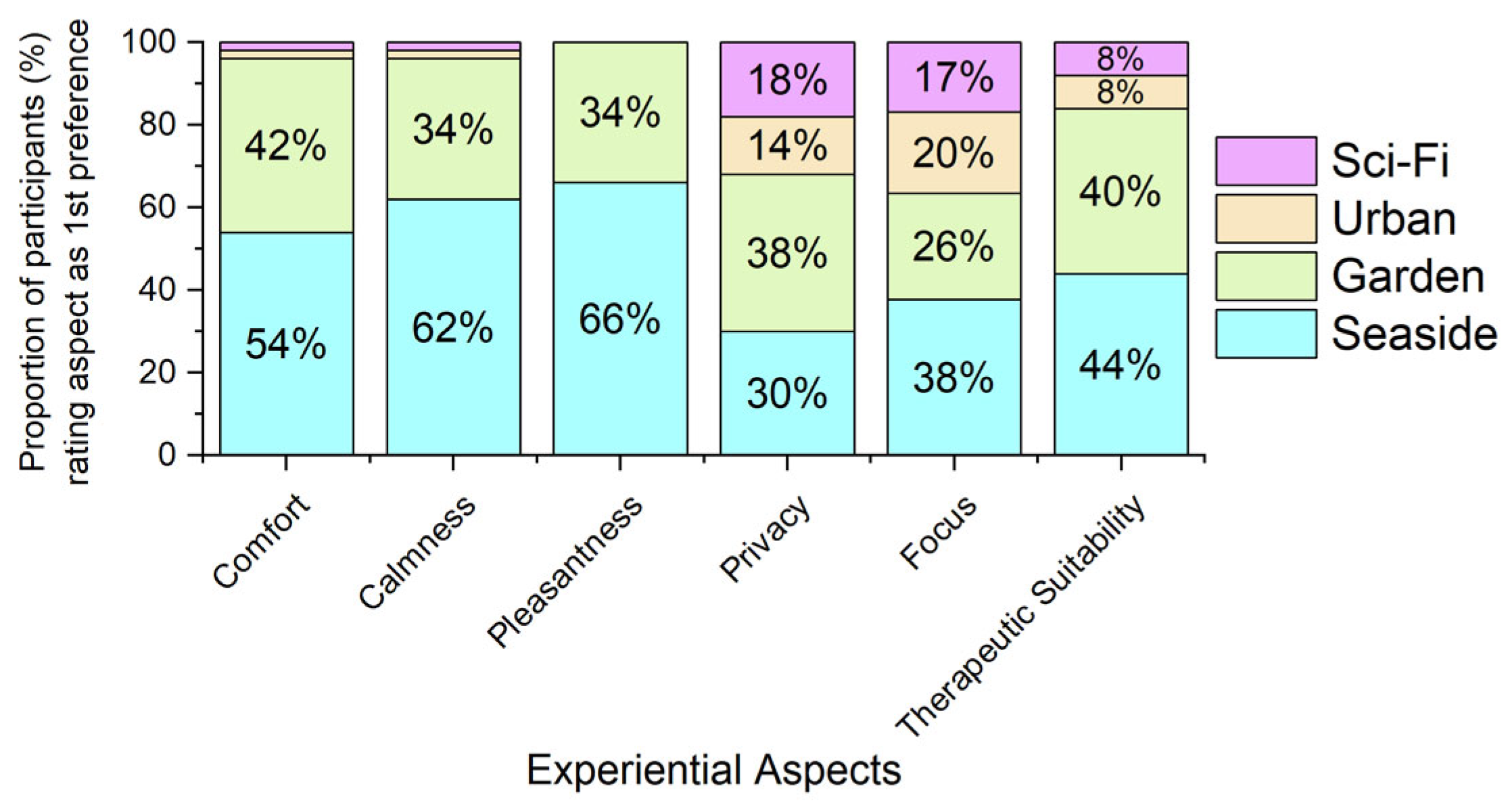

3.2. Preference Rankings

In addition to the post-interaction ratings, participants also provided overall preference rankings of the four environments after completing all disclosure tasks. Figure 2 presents the proportion of participants selecting each environment as their first preference for each experiential aspect. Consistent with the immediate ratings, the two nature environments remained the most preferred overall. For perceived therapeutic suitability, 44% of participants selected the seaside environment as their first choice, and 40% selected the garden, indicating a relatively even split. The seaside environment received the highest proportion of first-preference votes for comfort (54%), calmness (62%), and pleasantness (68%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of participants selecting each virtual environment as their first preference for each experiential aspect. Stacked bars represent the percentage of participants who ranked the seaside, garden, urban, or sci-fi environment as their top choice.

While the post-interaction ratings showed no significant differences between the two nature environments, the preference data reveal a clearer separation, with the seaside emerging as the clear favourite across some experiential dimensions. In contrast, preferences for privacy and focus were more evenly distributed across the four environments, indicating less consensus among participants for these aspects.

4. Discussion

The present study examined how distinct categories of virtual environments shape users’ psychological experience during emotionally meaningful self-disclosure interactions in VR. Across both composite and dimension-specific ratings, nature-themed environments were consistently experienced as more comfortable, calming, pleasant, and therapeutically suitable than non-nature environments. These findings extend existing work on VR self-disclosure [9,10,11,12,13] by showing that the environment itself, not just avatars or communication modality, systematically influences users’ interpersonal experience in VR. This highlights that VR environments actively shape the emotional and interpersonal dynamics of conversation, rather than serving as neutral backdrops.

4.1. Environmental Design Matters for Emotionally Meaningful Interaction

Participants rated the nature environments substantially higher than the urban and sci-fi settings, despite strict standardisation of avatar behaviour, interaction structure, and interpersonal distance. This demonstrates that environmental cues exert a measurable influence on the experiential qualities that matter for emotionally meaningful communication. This strengthens emerging evidence that environmental design in VR meaningfully shapes users’ emotional state and sense of interpersonal ease [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. The results align with restoration theories, which propose that natural settings support calmness, attentional ease, and emotional regulation [19,20]. The present findings show that these restorative benefits extend to interpersonal contexts relevant to counselling and support interactions.

The pattern also parallels real-world literature showing that natural outdoor settings can facilitate emotional openness and rapport during therapeutic interactions [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. The current study provides initial evidence that such interpersonal benefits may translate into immersive VR, suggesting that virtual nature is not merely aesthetically preferred but also functionally supportive of sensitive interpersonal dialogue. Notably, a small minority of participants selected the urban or sci-fi settings as their preferred context for therapy-like conversation, suggesting that there is no single optimal environment for all users and that some degree of personalisation is likely beneficial.

4.2. Distinctions Within Environment Types

Although the seaside and garden environments did not differ in the immediate post-interaction ratings, participants’ final rankings revealed greater preference for the seaside for comfort, calmness, and pleasantness. One explanation for this divergence is that immediate post-interaction ratings capture in situ affective responses constrained by the structured disclosure task, whereas ranking tasks may reflect more reflective or intuitive judgements of environmental preference formed across the session. In this context, the seaside environment may have benefitted from specific features commonly associated with blue-space restoration, such as an open visual horizon, visible water movement, and expansive spatial layout, which are less salient during brief task-focused ratings but become more influential during comparative evaluation. Cultural familiarity with coastal environments in Western Australia may have further amplified these preferences, given the strong recreational and symbolic associations of beaches and seaside settings in this context. Together, these factors suggest that while both nature environments provided similarly supportive immediate interaction contexts, blue-space features may exert a stronger influence on overall environmental preference when participants reflect on the experience more holistically.

Our findings are consistent with some real-world studies that suggest aquatic environments can evoke stronger feelings of calmness or restoration than green spaces, particularly when openness, natural sound, and visual movement are present [14,17,48]. However, within the broader literature, overall evidence for a generalised blue-space advantage is mixed, and further work is needed to determine whether this preference reflects environmental features, cultural familiarity, or population-specific factors [14,26,48,49].

Among non-nature settings, the urban environment was consistently preferred over the sci-fi environment. This likely reflects plausibility and familiarity: the urban scene resembles real-world counselling or office spaces, whereas the sci-fi environment introduces artificiality that may interfere with emotional grounding. This interpretation fits with research that suggests environmental incongruence might impair focus and interpersonal comfort in VR [50,51].

Notably, focus and privacy showed weaker differentiation across environments. This likely reflects task-level constraints rather than genuine equivalence between settings. The disclosure task was brief and highly structured, placing modest demands on sustained attention and thereby limiting the degree to which environmental features could differentially shape focus. Perceptions of privacy were also likely shaped by participants’ awareness of the experimental context, including the physical proximity of the experimenter, which may have anchored privacy judgements across environments. Importantly, this pattern reflects constrained interpretability rather than a lack of variability in the ratings themselves. Even so, both dimensions were rated more positively in the nature environments than in the non-nature environments. This pattern is consistent with an affective spillover, whereby the calming and pleasant qualities of the nature scenes elevate broader evaluative judgements, including privacy and focus.

4.3. Implications for VR Therapy and Conversational Systems

The findings have important implications for how VR might be used to support counselling, peer support, and other emotionally meaningful conversations. The results make it clear that the environment in VR is not a neutral backdrop. Even when everything else in the interaction is kept the same, the setting itself influences how comfortable, calm, and open people feel. Nature-themed environments consistently produced more positive experiences, suggesting that they are a sensible starting point when designing VR platforms intended for sensitive or emotionally charged dialogue. In contrast, highly artificial or stylised settings, such as the sci-fi scene, tended to make people feel less at ease, which highlights the value of choosing environments that feel plausible, familiar, and emotionally grounded.

These insights also matter for newer applications, such as conversational agents or AI-driven virtual therapists [52,53,54,55]. People’s willingness to disclose personal experiences, stay focused, and engage meaningfully is shaped not only by the virtual conversation partner but also by the environment that surrounds the interaction. This means that environmental design is closely tied to the quality of the interpersonal experience, rather than being a purely aesthetic decision. For psychological support, coaching, and digital mental-health tools delivered in VR, nature-based settings offer a simple and effective way to help users feel more comfortable and emotionally supported.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

Several limitations should be acknowledged. The sample comprised psychology undergraduates, which restricts generalisability and may partly explain the strong preference for the seaside environment, given the coastal familiarity of Western Australian residents. Interactions were also brief and highly structured, whereas longer or more naturalistic therapeutic conversations may elicit different experiential patterns. As such, the present study should be viewed as a foundational, laboratory-based investigation designed to isolate the influence of environmental cues under controlled conditions. The study examined only four pre-built VIVE Sync environments, limiting the range of spatial, sensory, and aesthetic features that could be tested. In addition, because the researcher remained physically nearby during disclosures, perceptions of privacy may have been constrained across conditions. Some participants may also have experienced novelty effects associated with using VR, which could have influenced their comfort or engagement during the interaction. In addition, the findings may not generalise directly to avatar-free settings, group-based VR therapy, or multi-user clinical applications, which likely involve different interpersonal dynamics.

Finally, all outcomes were self-reported, leaving open the question of how environmental design shapes behavioural or physiological indicators of emotional grounding. The absence of physiological indices such as heart rate variability (HRV) also limits the ability to validate the self-reported calmness effects physiologically. Although emotional and interpersonal responses to VR environments may plausibly vary as a function of age, gender, prior VR familiarity, or cultural associations with natural and coastal settings, the present study was not powered to support reliable moderation analyses. Accordingly, no exploratory moderator tests were conducted. Ethnicity and prior familiarity with VR were also not assessed, further limiting the ability to examine potential demographic or experience-based moderators of these effects. Future research using larger and more diverse samples should explicitly examine these individual differences. Additionally, the use of a 4-point scale may have reduced measurement sensitivity for some experiential dimensions, especially focus and perceived privacy. This is noted as a limitation and should be explored with higher-resolution scales in future work.

Future work should test whether the environmental effects observed here persist in extended or clinically meaningful dialogues, including genuine therapeutic sessions in VR with diverse clinically relevant populations [56,57,58]. A critical next step will be to examine whether these effects hold in longer, less structured, and more clinically authentic therapeutic interactions. More fine-grained manipulations of VR environments in self-disclosure contexts, such as lighting, weather patterns, spatial openness, natural soundscapes, or vegetation density, would help isolate the specific design elements that support or hinder emotionally meaningful interaction [39,41,59]. Incorporating physiological (e.g., heart rate, electrodermal activity) and behavioural measures (e.g., vocal markers, disclosure depth) would provide stronger evidence for the mechanisms through which environments influence user experience [38,39,45,60]. Finally, comparing interactions with human partners, avatars, and LLM-driven conversational agents would determine whether these environmental effects generalise to emerging VR-based digital mental health and telepresence systems [52,53,54,55].

5. Conclusions

In summary, the present study demonstrates that the design of virtual environments meaningfully shapes users’ psychological experience during emotionally significant conversations in VR. Nature-themed settings supported greater comfort, calmness, and perceived therapeutic suitability than non-nature environments, highlighting the importance of environmental design in emerging applications of VR for counselling, peer support, and emotionally aware conversational systems. Although further work is needed to generalise these findings beyond short laboratory interactions, the results offer a clear message for researchers and designers: immersive environments are not passive backdrops but active contributors to the quality of interpersonal experience. Treating environmental design as a core component of VR communication systems will be essential as VR becomes increasingly embedded in VR communication platforms that facilitate human–human interaction via avatars and human communication with AI-driven avatars.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010033/s1. Table S1. Wilcoxon signed-rank z values and effect sizes [r] for pairwise comparisons across environments for each experiential dimension. G. = Garden, S. = Seaside, U. = Urban, S.F. = Sci-Fi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, S.L.R.; methodology, T.C. and A.P.; formal analysis, T.C. and S.L.R.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C.; writing—review and editing, S.L.R., T.C. and A.P.; supervision, S.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Edith Cowan University (Approval number: 2023-04132-ROGERS; Approved 6 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available on figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30692063.v1.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1) was used to assist with editing, text refinement, and formatting. The authors reviewed and edited all AI-assisted output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Spaulding, E.M.; Fang, M.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Himmelfarb, C.R.; Martin, S.S.; Coresh, J. Prevalence and disparities in telehealth use among US adults following the COVID-19 pandemic: National cross-sectional survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e52124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowrouzi-Kia, B.; Bani-Fatemi, A.; Jackson, T.D.; Li, A.K.C.; Chattu, V.K.; Lytvyak, E.; Deibert, D.; Dennett, L.; Ferguson-Pell, M.; Hagtvedt, R.; et al. Evaluating the efficacy of telehealth-based treatments for depression in adults: A rapid review and meta-analysis. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2024, 35, 703–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perle, J.G.; Perle, A.R.; Scarisbrick, D.M.; Mahoney, J.J., III. Educating for the future: A preliminary investigation of doctoral-level clinical psychology training program’s implementation of telehealth education. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2022, 7, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geller, S. Cultivating online therapeutic presence: Strengthening therapeutic relationships in teletherapy session. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2020, 34, 687–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.L.; Miller, C.J.; Lindsay, J.A.; Bauer, M.S. A systematic review of providers’ attitudes toward telemental health via videoconferencing. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2020, 27, e12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, M.; Tweedlie, L.; Minnis, H.; Cronin, I.; Turner, F. Online therapy with families—What can families tell us about how to do this well? A qualitative study assessing families’ experience of remote Dyadic Developmental Psychotherapy compared to face-to-face therapy. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0301640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdag, M.T.; Jacquemin, P.H.; Wahl, N. Visit your therapist in metaverse-designing a virtual environment for mental health counselling. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2023 Proceedings, Hyderabad, India, 12 December 2023; p. 1579. [Google Scholar]

- Baccon, L.A.; Chiarovano, E.; MacDougall, H.G. Virtual reality for teletherapy: Avatars may combine the benefits of face-to-face communication with the anonymity of online text-based communication. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.L.; Broadbent, R.; Brown, J.; Fraser, A.; Speelman, C.P. Realistic motion avatars are the future for social interaction in virtual reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 2, 750729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.; Hollett, R.; Speelman, C.; Rogers, S.L. Behavioural realism and its impact on virtual reality social interactions involving self-disclosure. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.D.; Branson, I.; Hollett, R.C.; Speelman, C.P.; Rogers, S.L. Do realistic avatars make virtual reality better? Examining human-like avatars for VR social interactions. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2024, 2, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.D.; Branson, I.; Hollett, R.C.; Speelman, C.P.; Rogers, S.L. Expressiveness of real-time motion captured avatars influences perceived animation realism and perceived quality of social interaction in virtual reality. Front. Virtual Real. 2022, 3, 981400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S.L.; Pallister, A.; Canes, N. Virtual reality for self-disclosure: Comparing user experiences across VR, video and text chat. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, E.; Kindermann, G.; Domegan, C.; Carlin, C. Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promot. Int. 2020, 35, 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.; Clarke, D.; O’Keeffe, J.; Meehan, T. The impact of blue and green spaces on wellbeing: A review of reviews through a positive psychology Lens. J. Happiness Health 2023, 3, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanski, A.; McClelland, J.; Pearce-Walker, J.; Ruiz, J.; Verhougstraete, M. The effects of blue spaces on mental health and associated biomarkers. Int. J. Ment. Health 2022, 51, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.P.; Elliott, L.R.; Gascon, M.; Roberts, B.; Fleming, L.E. Blue space, health and well-being: A narrative overview and synthesis of potential benefits. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, C.; Wicks, C.; Barton, J. Green spaces for mental disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2023, 36, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, E.E.; McDonnell, A.S.; LoTemplio, S.B.; Uchino, B.N.; Strayer, D.L. Toward a unified model of stress recovery and cognitive restoration in nature. Parks Steward. Forum 2021, 37, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological benefits of viewing nature: A systematic review of indoor experiments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Q. The effect of exposure to the natural environment on stress reduction: A meta-analysis. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuda, Q.; Bougoulias, M.E.; Kass, R. Effect of nature exposure on perceived and physiologic stress: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 53, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.; Livingstone, A.; Dodds, M.; Kotte, D.; Geertsema, M.; O’Shea, M. Exploring forest therapy as an adjunct to treatment as usual within a community health counselling service. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2023, 25, 320–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S.J.; Robertson, N.; Jones, C.R.; Scordellis, J.-A. “Walk to wellbeing” in community mental health: Urban and green space walks provide transferable biopsychosocial benefits. Ecopsychology 2021, 13, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M. Moving beyond counselling and psychotherapy as it currently is—Taking therapy outside. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2014, 16, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.; Marshall, H. Taking counselling and psychotherapy outside: Destruction or enrichment of the therapeutic frame? Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2010, 12, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D.; Reed, P. The nature space. A reflexive thematic analysis of therapists’ experiences of 1:1 nature-based counselling and psychotherapy with children and young people: Exploring perspectives on the influence of nature within the therapeutic process. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2023, 23, 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickmeyer, A.; Smith, J.J.; Halpin, S.; McMullen, S.; Drew, R.; Morgan, P.; Valkenborghs, S.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Young, M.D. Walk-and-talk therapy versus conventional indoor therapy for men with low mood: A randomised pilot study. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2025, 32, e70035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.; Kidd, K.; Cooley, S.J.; Fenton, K. The feasibility of outdoor psychology sessions in an adult mental health inpatient rehabilitation unit: Service user and psychologist perspectives. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 769590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsis, I.; Simmonds, J.G. Using resources of nature in the counselling room: Qualitative research into ecotherapy practice. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2017, 39, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, E.; Gabriel, L. Investigating clients’ experiences of walk and talk counselling. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2023, 23, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince-Llewellyn, H.; McCarthy, P. Walking and talking for well-being: Exploring the effectiveness of walk and talk therapy. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2025, 25, e12847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.; Lehmann, J. An exploratory study of clients’ experiences and preferences for counselling room space and design. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2019, 19, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauge, A.L.; Lindheim, M.O.; Rotting, K.; Jonsen, S.A.K. The meaning of the physical environment in child and adolescent therapy: A qualitative study of the outdoor care retreat. Ecopsychology 2023, 15, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, A.T.; Williams, J.M.; Leibsohn, J.; Park, J.; Walther, B. “Put on Your Walking Shoes”: A Phenomenological Study of Clients’ Experience of Walk and Talk Therapy. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2024, 19, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.M.; Qiu, L.; Esposito, G.; Mai, K.P.; Tam, K.-P.; Cui, J. Nature in virtual reality improves mood and reduces stress: Evidence from young adults and senior citizens. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 3285–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, A.; Ficarra, S.; Thomas, E.; Bianco, A.; Nordstrom, A. Nature through virtual reality as a stress-reduction tool: A systematic review. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2023, 30, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, M.; Bunce, H. The effect of brief exposure to virtual nature on mental wellbeing in adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Shen, X.; Shen, Y. Improving immersive experiences in virtual natural setting for public health and environmental design: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, S.; Kaleva, I.; Nicholson, S.L.; Payne-Gill, J.; Steer, N.; Azevedo, L.; Vasile, R.; Rumball, F.; Fisher, H.L.; Veling, W. Virtual reality relaxation for stress in young adults: A remotely delivered pilot study in participants’ homes. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2024, 9, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdejo-Espinola, V.; Zahnow, R.; O’Bryan, C.J.; Fuller, R.A. Virtual reality for nature experiences. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 1005–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, G. Access to nature via virtual reality: A mini-review. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 725288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhao, B.; Xu, Y.; Wei, W. Effects of immersion in a simulated natural environment on stress reduction and emotional arousal: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1058177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachini, T.; Coello, Y.; Frassinetti, F.; Ruggiero, G. Body space in social interactions: A comparison of reaching and comfort distance in immersive virtual reality. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakoc, C.; Lucifora, C.; Massimino, S.; Nucera, S.; Vicario, C.M. Extending peri-personal space in immersive virtual reality: A systematic review. Virtual Worlds 2025, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascon, M.; Zijlema, W.; Vert, C.; White, M.P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Outdoor blue spaces, human health, and well-being: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1207–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Feng, B.; Wang, J. Green spaces, blue spaces and human health: An updated umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1505292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; Perkis, A. Authenticity and presence: Defining perceived quality in VR experiences. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1291650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safikhani, S.; Gattringer, V.; Schmied, M.; Pirker, J.; Wriessnegger, S.C. The influence of realism on the sense of presence in virtual reality: Neurophysiological insights using EEG. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2024, 8, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriuchi, E. Leveraging the science to understand factors influencing the use of AI-powered avatar in healthcare services. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2022, 7, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvin, A.D.; Benjamin, C. Exploring the use of AI avatars by marriage and family therapists practitioners as a therapeutic intervention. Fam. Relat. 2024, 74, 1341–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, D.; Olafsson, S.; Utami, D.; Murali, P.; Bickmore, T. Designing empathic virtual agents: Manipulating animation, voice, rendering, and empathy to create persuasive agents. Auton. Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2022, 36, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheu, M.; Shin, J.Y.; Huh-Yoo, J. Systematic review: Trust-building factors and implications for conversational agent design. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 37, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, I.H.; Pot-Kolder, R.; Rizzo, A.; Rus-Calafell, M.; Cardi, V.; Cella, M.; Ward, T.; Riches, S.; Reinoso, M.; Thompson, A. Advances in the use of virtual reality to treat mental health conditions. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 3, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraets, C.N.; Van der Stouwe, E.C.; Pot-Kolder, R.; Veling, W. Advances in immersive virtual reality interventions for mental disorders: A new reality? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 41, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paalimäki-Paakki, K.; Virtanen, M.; Henner, A.; Vähänikkilä, H.; Nieminen, M.T.; Schroderus-Salo, T.; Kääriäinen, M. Effects of a 360° virtual counselling environment on patient anxiety and CCTA process time: A randomised controlled trial. Radiography 2023, 29, S13–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Chiang, Y. The influence of forest resting environments on stress using virtual reality. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladakis, I.; Filos, D.; Chouvarda, I. Virtual reality environments for stress reduction and management: A scoping review. Virtual Real. 2024, 28, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.