Abstract

Background: Footwear may influence paediatric gait biomechanics, yet evidence across footwear types and barefoot conditions remains heterogeneous. This review aimed to synthesise evidence on how footwear affects gait biomechanics in children and adolescents compared with barefoot walking, and to conduct exploratory meta-analyses when feasible. Methods: We performed a PRISMA-guided systematic review (PubMed and Scopus; inception to November 2025) including participants < 18 years with gait outcomes assessed under barefoot and/or defined footwear conditions. Outcomes included spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, and plantar-pressure variables. Risk of bias was assessed with ROBINS-I. Random-effects meta-analyses (inverse-variance) were conducted only when ≥2 studies reported comparable outcomes. Results: Twenty-two studies were included; most were observational with overall moderate-to-serious risk of bias, mainly due to confounding and participant selection. Quantitative synthesis (exploratory): Meta-analyses were possible only for ankle plantarflexion (k = 2) and stride length (k = 3) and showed non-significant pooled effects with extreme heterogeneity (I2 > 90%) and wide prediction intervals. Narrative synthesis: For other outcomes, heterogeneity in designs, footwear definitions, and measurement protocols precluded pooling; conventional footwear may reduce metatarsophalangeal mobility and alter kinematics and plantar pressure in some contexts, while minimalist/biomimetic features may approximate barefoot-like values for selected parameters without implying equivalence. Conclusions: Footwear exposure in childhood may affect several gait-related parameters, but the certainty of evidence is low to moderate due to risk of bias, inconsistency, and imprecision. Standardised footwear classifications, harmonised gait protocols, and longitudinal studies are needed to clarify developmental implications and inform evidence-based guidance.

1. Introduction

The paediatric years encompass a developmental period characterised by rapid growth and profound neuromuscular maturation. During this time, children acquire and refine fundamental locomotor skills such as walking, and these skills are shaped by a complex interaction between intrinsic biological factors and modifiable extrinsic influences [1,2,3,4]. Among the latter, footwear is particularly relevant because it represents a permanent interface between the foot and the ground and is one of the few environmental factors that can be deliberately modified in terms of fit, structure, and mechanical properties throughout childhood [2,3,4,5,6].

From a developmental perspective, the growing foot is highly plastic. Longitudinal and cross-sectional studies suggest that habitual barefoot exposure during childhood is associated with distinct foot morphology and function, including a higher medial longitudinal arch, greater hallux range of motion, a wider forefoot, and stronger intrinsic foot muscles compared with peers who are habitually shod [1,6,7,8]. However, the term “habitually barefoot” is not consistently operationalised across studies. In practice, it may refer to children who spend most of their daily time without shoes, those living in environments where barefoot walking is common, or populations with limited access to footwear; moreover, explicit thresholds (e.g., proportion of time barefoot) are rarely standardised. This variability limits comparability between studies and complicates interpretation when contrasting acute barefoot testing with long-term footwear exposure. In cross-cultural comparisons, Mauch et al. observed that a greater proportion of Australian children presented with a higher medial arch than German children, who were more consistently shod, supporting the notion that footwear can influence structural development of the foot [7]. More recent work in toddlers indicates that children habitually using barefoot-style shoes show a higher plantar arch and different foot progression angles than those wearing conventional footwear, reinforcing the potential impact of footwear choices from the very first steps [8]. These morphological changes may, in turn, affect motor performance and balance, with barefoot or minimally shod children often demonstrating superior performance in tasks requiring postural control and dynamic stability [1,2,9].

Concurrently, footwear plays a central role in the biomechanics of gait. During acute shod walking (i.e., immediate changes observed when walking in shoes during an experimental protocol), alterations in the stance phase have been reported, such as modified foot-strike orientation, reduced metatarsophalangeal (MTP) extension during propulsion, and constraints on forefoot mobility, all of which may compromise the efficient functioning of the Windlass mechanism [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Conventional athletic footwear in children can significantly reduce the range of motion of the first MTP joint and the midfoot during the propulsive phase of gait [12,14,15]. Compensatory increases in ankle dorsiflexion and knee flexion have been described in several studies [13,16,17,18,20]. These joint-level adaptations are reflected in spatiotemporal parameters such as gait speed, stride length, swing time, and step width, although findings across the literature are not always consistent [12,13,18,19,20,21]. Although the broader locomotion literature includes running, the present review primarily focuses on walking gait biomechanics, as walking outcomes are most consistently reported across paediatric footwear studies and allow more meaningful comparison across conditions.

The design of children’s footwear is heterogeneous and includes variations in cushioning, heel height and drop, heel-counter rigidity, sole flexibility and flexion-point location, upper height and material, and surface texture [2,14,15,22,23,24,25,26,27]. These elements, alone or in combination, have been shown to influence lower-limb kinematics and kinetics, including ankle and knee joint excursions and plantar loading patterns [4,8,9,13,14,15,20,21,22,26].

Historically, the terminology and classification of clinical and everyday footwear have been inconsistent, using labels such as “orthopaedic”, “supportive”, or “special” shoes without clear definitions. Recent consensus work has proposed “therapeutic footwear” as an overarching term for children’s footwear interventions—encompassing accommodative, corrective, and functional categories—and has identified design features of stability footwear that may influence mediolateral control during gait [5,28]. Parallel efforts have generated taxonomies of young children’s footwear types and common features [6,29,30], provided a consensus definition and rating scale for minimalist shoes [31], and developed standardised paediatric assessment proformas such as GALLOP to harmonise gait and lower-limb data collection [32].

These methodological advances highlight a growing recognition that children’s footwear should be described and studied in a standardised, transparent manner. Nevertheless, recent narrative and scoping reviews underline that much of the current footwear guidance for children remains based on tradition, expert opinion, or marketing rather than robust empirical evidence [4,5,6]. Inconsistencies in how footwear is defined and reported, together with diverse outcome measures across studies, limit the ability to synthesise findings and to translate them into clear, age-appropriate recommendations for parents, clinicians, and industry [6,29,33]. This is particularly important in early childhood, when rapid changes in foot structure and locomotor demands coincide with high parental concern about choosing “the right shoe” [29,30].

In this context, there is a need for a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous synthesis of the available evidence addressing how different types of footwear influence children’s gait. Given variability in the definition of habitual barefoot exposure and heterogeneity in footwear classifications, it remains unclear to what extent footwear modifies spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, and plantar pressure parameters during walking across paediatric age groups, and whether these changes are likely to have meaningful implications for locomotor development and long-term foot health.

This systematic review addresses the following questions: (RQ1) What acute effects does footwear (conventional, minimalist, and biomimetic designs) have on children’s walking gait biomechanics compared with barefoot walking? (RQ2) How do gait outcomes differ between children with habitual barefoot exposure versus habitually shod children, when walking is assessed under comparable conditions? (RQ3) Which footwear design features (e.g., forefoot width, heel-to-toe drop, sole flexibility) are most consistently associated with changes in spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, and plantar-pressure outcomes during walking?

In contrast to prior narrative/scoping work, this review (i) applies operational definitions to distinguish acute barefoot testing, habitual barefoot exposure, and minimalist/biomimetic footwear; (ii) focuses primarily on walking outcomes to improve comparability; and (iii) provides an exploratory quantitative synthesis (prediction intervals and sensitivity analyses) only where data were sufficiently comparable, while transparently reporting uncertainty.

Therefore, the main objective of this systematic review (with exploratory meta-analysis where feasible) is to analyse biomechanical differences associated with different footwear conditions compared with barefoot walking, evaluating spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, and plantar pressure variables.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. Section 2 details the Methods, including information sources and search strategy, eligibility criteria and study selection, risk-of-bias assessment (ROBINS-I), and the statistical approach for the exploratory meta-analysis. Section 3 presents the Results, including the PRISMA flow, study characteristics, risk of bias, narrative synthesis of gait outcomes, and the exploratory meta-analyses. Section 4 discusses the findings in relation to the research questions, highlights limitations and implications, and outlines directions for future research. Section 5 provides the Conclusions. Supplementary Materials provide the full search strategies, sensitivity analyses, and detailed ROBINS-I judgements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) under the registration number CRD42025628073. The research topic was defined using the PECO framework: Population (P): Children and adolescents under 18 years of age. Exposure (E): Use of footwear (including conventional, athletic, minimalist, school, or biomechanical footwear). Comparator (C): Barefoot condition or comparisons between different types of footwear. Outcome (O): Gait parameters (spatiotemporal variables (step length, cadence, velocity), kinematic variables (joint angles), kinetic variables (joint moments, ground reaction forces), and plantar pressures).

Operational Definitions

To reduce conceptual overlap across included studies, we used the following operational definitions during data extraction and interpretation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Operational definitions of barefoot exposure and footwear categories used in this review.

The proposed inclusion criteria encompassed experimental, quasi-experimental, or observational studies with crossover or comparative designs, and peer-reviewed publications involving paediatric populations (≤18 years). Studies had to assess gait under barefoot and/or various footwear conditions and report at least one gait variable: spatiotemporal, kinematic, kinetic, or plantar pressure. Articles written in English or Spanish were included, with no publication date restriction.

Exclusion criteria included medical conditions that significantly affected gait (e.g., cerebral palsy, neuromuscular injuries), interventions involving orthoses or insoles without isolating the effect of footwear, and studies lacking comparative data between footwear conditions or failing to report standard deviation, standard error, or confidence intervals.

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Systematic searches were conducted in the PubMed and Scopus databases from their inception through November 2025. The search strategy combined terms related to paediatric footwear and gait, as well as general terms associated with gait and footwear:

(“children” OR “pediatric” OR “infant” OR “adolescent”) AND (“footwear” OR “shod” OR “shoe” OR “barefoot” OR “minimalist shoe” OR “school shoe”) AND (“gait” OR “walking” OR “running”) AND (“spatiotemporal” OR “step length” OR “cadence” OR “kinematics” OR “kinetics” OR “ground reaction force” OR “pressure” OR “moment”) (Supplementary Field).

The search was tailored to each database and supplemented with manual screening of relevant references.

2.3. Study Selection and Record Management

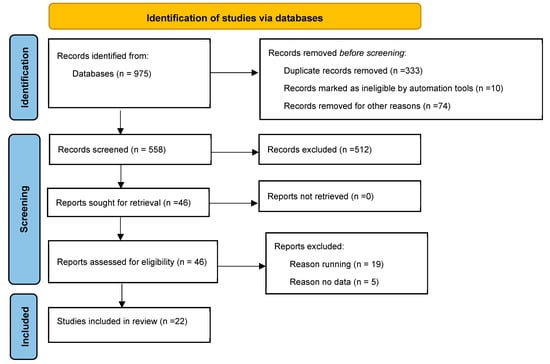

Two reviewers independently screened records by title/abstract and subsequently assessed full texts for eligibility. After database export, records were imported into Rayyan and duplicates were removed using the software’s automatic de-duplication function, followed by a manual check. A master spreadsheet (Excel) was used to centralise decisions, track reasons for exclusion at full text, and resolve discrepancies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and, when necessary, by consultation with a third reviewer. The selection process was documented using a PRISMA flow diagram [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for the systematic review (database searches only).

2.4. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from each included study: Author(s), year of publication, study design, and sample size. Age and sex of participants. Type of comparison (barefoot vs. shod; footwear type). The following gait variables were included. Spatiotemporal: velocity, stride length, cadence. Kinetic: impact force, joint moments. Kinematic: dorsiflexion, knee flexion, hip flexion/extension, etc. Plantar pressure: peak pressure, mean pressure, contact area. Results: means, standard deviations (SD), standard errors (SE), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and effect sizes (Cohen’s d, if reported or calculated).

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the ROBINS-I tool (Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomised Studies-of Interventions) for non-randomised studies. [34] The ROBINS-I tool, developed by Sterne et al., enables a structured assessment of bias across seven domains, ranging from participant selection to outcome measurement and selection. Each domain is rated as low, moderate, serious, critical, or with insufficient information to judge, providing an overall estimate of the study’s risk of bias. A concise summary of overall ROBINS-I judgements is provided in Supplementary Table S1, and full domain-level assessments for each study are reported in File SIII.

2.6. Statistical Analysis: Exploratory Quantitative Synthesis

Given the limited number of studies reporting comparable outcomes, any quantitative synthesis was planned a priori as exploratory and intended to complement the narrative synthesis rather than provide confirmatory evidence. Random-effects meta-analyses were conducted only when at least two studies reported sufficiently comparable data for the same outcome.

Meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) Web (The Cochrane Collaboration). Effect sizes were expressed as standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to allow comparability across studies. Pooled estimates were calculated using the inverse-variance random-effects model, with between-study variance (τ2) estimated using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method and CIs calculated using the Wald-type approach (as implemented in RevMan). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

Statistical heterogeneity was quantified using I2, and we additionally report τ2 and the χ2 test for heterogeneity. To explicitly convey uncertainty under heterogeneity, we report 95% prediction intervals, representing the range in which the true effect of a future study may plausibly lie. Results are presented in forest plots showing individual study effects, their relative weights, and the pooled estimate.

For outcomes with ≥3 studies, we conducted leave-one-out sensitivity analyses (Table 2) by repeating the random-effects meta-analysis after omitting one study at a time to assess the influence of individual studies on pooled estimates.

Table 2.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis for stride length (random-effects, REML).

When heterogeneity was extreme and/or the evidence base was sparse (k = 2–3), pooled results were interpreted cautiously, and the narrative synthesis was prioritised.

3. Results

A total of 975 records were identified through database searches. After removing 333 duplicates, 10 records were removed by automated record management and 74 were removed for other reasons; 558 records remained for screening. Records removed by automated record management refer to automatic record-management functions (automated duplicate detection in Rayyan) applied prior to manual screening; no automated eligibility exclusions were performed. Following title/abstract screening, 512 records were excluded and 46 full-text reports were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 24 were excluded (19 running-only; 5 lacking relevant gait data), resulting in 22 studies included in the review (Figure 1).

3.1. Study Characteristics

All 22 studies included in the review were observational in nature, comprising 20 cross-sectional studies and 2 longitudinal studies. The sample sizes ranged from 13 to 810 participants, with a total of over 3500 children and adolescents across all studies. Participant ages varied from 2 to 18 years, although one study did not specify the age range. Most studies included both sexes, although not all reported the distribution; when reported, female representation varied and was not always balanced [File SI].

The mean age across the samples was not consistently reported, but most studies focused on school-age children and early adolescents. Several studies clearly distinguished between habitually barefoot and habitually shod participants, often comparing their biomechanical or morphological characteristics [File SI].

In terms of content focus, a significant number of studies analysed foot morphology, arch development, and biomechanical parameters during walking, either barefoot or with various types of footwear. Others focused on performance measures such as jumping, balance, or gait velocity [File SII].

Measurement instruments and methodologies were diverse, including 3D motion analysis, plantar pressure platforms, high-speed video analysis, clinical tests, and custom questionnaires to evaluate barefoot habits and physical activity levels. Many of the studies used field-based data collection protocols, especially in school settings, while others were carried out in laboratory environments [File SII].

Regarding confounding factors, approximately half of the studies controlled for variables such as age, sex, BMI, ethnicity, and physical activity level in their analyses.

Intrinsic factors identified across studies included ankle dorsiflexion range, plantar pressure distribution, foot posture and alignment, whereas extrinsic factors included type and frequency of footwear use, surface hardness, and type of physical activity performed. Some studies suggested that habitual barefoot locomotion may contribute to higher medial longitudinal arch development, greater pliability of the foot, or altered foot strike patterns.

3.2. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias was assessed using the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomised studies. Overall risk of bias was predominantly moderate to serious (Supplementary Table S1), reflecting important methodological limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. Full domain-level judgements for each study are reported in File SIII.

The most frequent sources of bias were related to confounding and selection of participants, mainly due to limited control of relevant covariates (e.g., age, BMI, physical activity level, and socioeconomic background) and the use of non-random sampling or voluntary recruitment in school settings. Specific examples of issues are listed below:

- Confounding was commonly judged as moderate/serious because key baseline characteristics and co-exposures were not consistently measured or adjusted for;

- Selection of participants was frequently rated as moderate/serious due to potential selection bias associated with convenience sampling and recruitment procedures;

- Classification of interventions/exposures (e.g., defining children as habitually barefoot or shod) was generally well described, resulting in mostly low risk ratings in this domain;

- Deviations from intended interventions and missing data were typically rated as low risk, suggesting reasonable adherence and completeness of reporting in most studies;

- Measurement of outcomes showed greater variability, with higher risk ratings in some studies due to limited standardisation of assessment protocols and/or reliance on subjective measures;

- Selection of the reported result was generally low to moderate; in some studies, incomplete reporting of secondary outcomes limited transparency.

Overall, while the included observational studies provide useful data, the evidence base is constrained by confounding and participant selection, which reduces certainty in the estimated effects.

3.3. Meta-Analysis

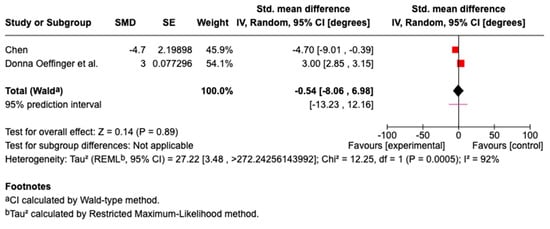

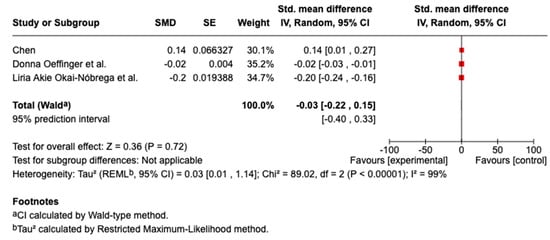

Exploratory meta-analysis (walking outcomes only)

Quantitative synthesis was feasible only for ankle plantarflexion and stride length, as these were the only outcomes reported by at least two studies with sufficiently comparable data to allow standardisation and pooling (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Given the very small number of studies contributing to each outcome (k = 2–3), the extreme heterogeneity, and the resulting wide prediction intervals, pooled effects are presented strictly as exploratory descriptive summaries to complement the narrative synthesis and should not be interpreted as definitive quantitative estimates.

Figure 2.

Standardised mean differences in ankle plantar flexion between experimental and control groups [16,17].

Figure 3.

Standardised mean differences in stride length between experimental and control groups [16,17,20].

For stride length (k = 3), leave-one-out analyses (Table 2) suggested that the pooled estimate varied in magnitude and, in some cases, direction, further supporting the exploratory interpretation of the quantitative synthesis. For ankle plantarflexion (Figure 2; k = 2), two studies were included and individual effects were directionally discordant (Chen: SMD = −4.70; Oeffinger et al.: SMD = 3.00), yielding a highly imprecise pooled estimate (random-effects: SMD = −0.54, 95% CI −8.06 to 6.98; Z = 0.14, p = 0.89) with substantial heterogeneity (τ2 = 27.22; I2 = 92%; χ2 = 12.25, p = 0.0005). The 95% prediction interval was very wide (−13.23 to 12.16), indicating that effects in future studies could plausibly vary greatly in both magnitude and direction.

For stride length (Figure 3; k = 3), although individual effects were relatively close to the null (range: 0.14 to −0.20), heterogeneity remained extreme (τ2 = 0.03; I2 = 99%; χ2 = 89.02, p < 0.00001). The pooled estimate was near zero and not statistically significant (random-effects: SMD = −0.03, 95% CI −0.22 to 0.15; Z = 0.36, p = 0.72). The 95% prediction interval (−0.40 to 0.33) still encompassed both beneficial and harmful effects, reinforcing substantial uncertainty.

Overall, both meta-analyses indicate considerable between-study variability with non-significant pooled effects and prediction intervals spanning both directions, supporting an interpretation driven primarily by the narrative synthesis.

Other gait outcomes were not suitable for quantitative pooling because they were inconsistently reported across studies (different protocols/definitions, units, or insufficient summary statistics), preventing standardisation and comparable effect estimation.

4. Discussion

This study examines the impact of footwear usage on paediatric gait compared with natural barefoot conditions, identifying relevant effects on the biomechanics of the developing foot. Overall, our findings suggest that footwear is not merely a neutral interface but a modifiable factor that may influence joint kinematics, spatiotemporal parameters, and plantar pressure distribution during childhood. These observations are broadly consistent with recent literature highlighting that children’s footwear can modify gait patterns and that many traditional recommendations remain based on convention or expert opinion rather than robust empirical evidence [4,27,32,33]. However, the strength of inferences is constrained by heterogeneity in footwear definitions, protocols, and outcome reporting across studies.

The exploratory meta-analyses should be interpreted with caution. With very few studies and extreme heterogeneity, pooled estimates have limited interpretability, and prediction intervals are necessarily wide. Nevertheless, we retained these analyses for transparency and to provide an approximate quantitative summary of direction and magnitude, while explicitly presenting heterogeneity and uncertainty. Importantly, our conclusions are based primarily on the narrative synthesis and the consistency (or inconsistency) of findings across studies rather than on the pooled estimates.

The accumulated evidence in this review suggests that footwear can reduce the maximum flexion of the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint during walking in children [3,12,15]. This reduction—reported as close to 20° in some studies—may reflect a restriction of forefoot mobility and an increase in plantar rigidity, which could influence propulsive mechanics. In-shoe multi-segment analyses similarly show reduced first MTP dorsiflexion and midfoot motion when children wear conventional athletic shoes [6,22]. However, whether these acute kinematic changes translate into clinically meaningful long-term consequences—for example, in relation to proprioception, development of the medial longitudinal arch, or the potential risk of hallux limitus/hallux valgus—remains unclear. This highlights the need for longitudinal studies linking repeated gait assessments to structural outcomes and symptom trajectories.

Regarding foot drop velocity, Elvira et al. reported that footwear decreases this velocity in girls during walking [3], suggesting potentially reduced demands on ankle dorsiflexor control. This may reflect sex-specific differences in shoe design, as girls’ footwear is often narrower and stiffer in the rearfoot region. Other work has documented sex-related differences in foot morphology and maturation patterns [35,36,37], indicating that sex may moderate children’s biomechanical response to footwear. Mizushima et al. found that a high proportion of habitually shod children used a heel-strike pattern when wearing footwear compared with barefoot walking [17,38,39]. Together, these data suggest that footwear may promote a more rearfoot-dominated strike pattern in some children, although patterns likely vary with age, surface conditions, and shoe properties.

The present synthesis also highlights that footwear can modify the spatial relationship between the foot and the shoe. Elvira et al. observed an anterior displacement of the MTP flexion axis of approximately 1 cm when children walked in shoes [3]. This is consistent with studies showing that when the shoe’s flexion line does not coincide with the anatomical MTP joints, plantar loading patterns are altered, and stress may be increased in specific forefoot regions [25]. From a design perspective, aligning the flexion point of the sole with the natural flexion axis of the foot appears important for facilitating push-off mechanics and minimising excessive forefoot loading.

Evidence regarding the foot progression angle was limited; significant differences were observed only in boys during walking with a moderate effect size in one study [3]. Similar results have been reported in comparisons of barefoot and shod gait in school-aged children [10,11,21,40]. It is plausible that children adjust rotations proximally (hip/pelvis) to maintain a relatively stable foot progression angle despite modifications at the foot–shoe interface.

Regarding longer-term morphological characteristics, cross-sectional comparisons of habitually barefoot and habitually shod populations report differences in arch morphology, foot width, and plantar contact area [5,37]. However, the trial by Gimunová et al., which compared toddlers wearing barefoot-style footwear with those in conventional shoes, found no significant differences in arch height or footprint indices after the follow-up period [6]. The small sample size and very young age (all participants under two years) may have limited the capacity to detect structural adaptations. Recent scoping work suggests that timing, duration, and intensity of barefoot or minimalist exposure, together with cultural habits and surface types, likely moderate outcomes and may explain part of the heterogeneity observed between studies [32].

There is also considerable variability in how “habitually barefoot” and “minimalist” are defined. Cranage highlighted the lack of standardisation in definitions of barefoot exposure when examining long-term outcomes [41]. For footwear, Esculier et al. proposed a consensus definition and rating scale for minimalist shoes based on weight, flexibility, drop, stack height, and stability [30]. Applying such frameworks to paediatric research would improve comparability and allow more precise interpretation of interventions described as “minimalist”, “respectful”, or “biomimetic”.

Plantar pressure outcomes provide further insight into how footwear redistributes load. Hillstrom et al. showed that shoes can reduce peak pressures at the heel and forefoot compared with barefoot conditions, while sometimes increasing midfoot contact [42]. Kellis reported that dynamic tasks substantially increase plantar pressures relative to quiet standing [43]. These observations are relevant for interpreting included studies because differences in task selection, speed, and surface conditions strongly influence pressure patterns. While it is plausible that sustained changes in regional loading during growth could contribute to callus formation, discomfort, or structural adaptations, current evidence remains insufficient to establish causal links.

Kinematic findings in the present review are broadly consistent with prior literature. Footwear is often associated with changes in step length and gait velocity and with altered ankle and knee excursions [7,10,13,16,17,20], although findings are not uniform across studies. Several studies describe increased knee flexion during mid-stance and greater ankle dorsiflexion at initial contact in shod conditions, while others report smaller effects [11,16,17]. Mahaffey et al. highlight that foot motion continues to evolve throughout childhood and that age-related changes in 3D foot kinematics must be considered when interpreting footwear effects [36]. Overall, heterogeneity in shoe characteristics, age groups, and methodologies likely explains part of the inconsistency between studies.

The role of sole flexibility and upper design is illustrative. Cranage et al. found that, although walking with shoes alters spatiotemporal parameters compared with barefoot gait, differences between soft and rigid soles were minimal, apart from a small reduction in step length with rigid-soled sandals [44,45]. Kung et al. also reported that footwear influences stride length and ankle and knee kinetics and kinematics, though without isolating sole stiffness as the main driver [20]. Van Hamme et al. observed that upper height had a greater influence on gait dynamics than heel height or sole stiffness [19]. These results suggest that focusing on a single parameter, such as “flexible vs. rigid”, may oversimplify the multi-component nature of footwear, supporting the need for comprehensive reporting frameworks such as the CHILD-SHOE checklist [34].

Biomimetic footwear offers an interesting contrast. Okai-Nobrega et al. analysed young children walking barefoot, in biomimetic footwear, and in conventional shoes [20,45]. Biomimetic shoes, which incorporate dynamic insoles intended to mimic irregular surfaces, were associated with smaller alterations in selected ankle and knee kinematics and closer similarity to barefoot gait for certain parameters (e.g., centre-of-mass vertical displacement). They also reported changes in medial longitudinal arch measures, interpreted as a functional response to altered sensory input; however, these findings should be interpreted cautiously given study design limitations and short follow-up.

Fit and forefoot width emerge as additional determinants of biomechanical response. In Okai-Nobrega’s work, wider-forefoot models showed less deviation from barefoot gait for some parameters [20]. Breet et al. suggested that prolonged use of narrow or poorly fitted shoes in childhood may contribute to reduced forefoot mobility and increased midfoot stiffness [46,47,48]; however, the extent to which these associations reflect causal effects remains uncertain. Evidence indicates that poor fit is frequent in school-aged children and may be associated with discomfort and altered foot function [2,29,35], while parents and some professionals may prioritise aesthetics or durability over flexibility and fit [35].

Specific footwear types, such as thong-style sandals, also illustrate how design constraints may elicit compensatory strategies. Chard et al. reported increased ankle dorsiflexion and midfoot plantarflexion when children walked in thong sandals, interpreted as a mechanism to retain the shoe due to minimal structural support [4]. They also found reduced hallux dorsiflexion, which could compromise optimal activation of the Windlass mechanism during late stance.

Ankle plantarflexion during push-off is another parameter reported as affected by footwear. Oeffinger et al. observed a reduction of approximately 3° in peak plantarflexion and lower power generation during push-off in shod children, although the authors considered these differences clinically small in healthy participants [17]. Chen et al. reported reduced plantarflexion during swing and increased dorsiflexion at initial contact in the shod condition [16]. Taken together, available evidence suggests that conventional footwear may increase step length while slightly restricting terminal plantarflexion [16,20], but the functional relevance likely depends on the magnitude of change, individual morphology, and cumulative exposure.

4.1. Acute Effects vs. Long-Term Implications

A key conceptual distinction is between acute footwear effects (immediate changes observed when children walk in a given shoe during an experimental protocol) and potential long-term developmental implications (adaptations in foot structure, strength, or motor control associated with sustained exposure). Most included studies assess short-term gait responses, whereas longitudinal evidence remains limited. Accordingly, developmental implications should be treated as hypotheses requiring confirmation in prospective studies with standardised footwear characterisation and repeated follow-up assessments.

Taken together, the findings of this review support the view that children’s footwear should be selected with attention to anatomical fit and functional design features. Footwear described as anatomically appropriate—characterised by adequate fit, wider toe boxes, low heel-to-toe drop, and high flexibility—may facilitate more natural foot motion and sensory feedback in some contexts; however, given heterogeneity and risk of bias, definitive claims about the superiority of specific designs are premature. Recent consensus and Delphi studies involving parents, clinicians, and industry stakeholders underline the need for clearer, evidence-informed guidance on footwear features in early childhood [28,29,34,35,49].

4.2. Conflicts of Interest and Risk of Bias

Some included studies reported funding or other links with footwear manufacturers, which may influence study design choices or the completeness of outcome reporting. While ROBINS-I does not treat sponsorship as a standalone domain, manufacturer involvement may indirectly contribute to concerns related to the selection of the reported result and transparency. Given that no study was judged to have a low overall risk of bias, careful reporting of funding sources, protocols, and outcomes is essential to strengthen confidence in future evidence.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, methodological heterogeneity across the included studies—in terms of participant age, footwear type, testing surface, exposure duration, and outcome measures—reduces comparability and may explain part of the inconsistency in the literature. Second, most studies focused on acute or short-term effects, leaving the medium- and long-term impact of different footwear types on foot structure and function largely unknown. Third, children from cultures with high rates of habitual barefoot activity were under-represented, limiting generalisability [32,37,38]. Finally, potential manufacturer involvement reinforces the importance of adopting reporting tools such as the CHILD-SHOE checklist to improve transparency and reproducibility [34].

A major limitation of this review is the scarcity and heterogeneity of the available evidence. Only a small number of studies reported sufficiently comparable outcomes to permit quantitative synthesis (k = 2–3), and between-study variability was extreme, which limits the interpretability of pooled estimates and results in wide prediction intervals. Accordingly, the meta-analytic findings should be regarded as exploratory summaries rather than definitive effect estimates.

Additional limitations include variability in study designs, participant characteristics, footwear definitions and reporting, and outcome measurement protocols, all of which reduce comparability and preclude meaningful subgroup or moderator analyses. These issues underscore the need for standardised reporting of footwear characteristics and gait outcomes in future studies.

With respect to RQ1, most included studies suggest that footwear may acutely modify selected walking gait parameters compared with barefoot, although effects vary by outcome and shoe design. For RQ2, comparisons involving habitual barefoot exposure are difficult to interpret consistently due to heterogeneous operational definitions and confounding. Regarding RQ3, design features related to forefoot space, low heel-to-toe drop, and flexibility appear more frequently associated with barefoot-like values for some parameters; however, causal inferences remain limited by study design and risk of bias.

Future studies should adopt standardised footwear classifications and reporting, harmonised biomechanical protocols, and adequately powered designs (including age- and sex-stratified analyses and, where feasible, longitudinal follow-up) to clarify potential developmental implications and to inform evidence-based footwear recommendations for children.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review synthesises the available evidence on how footwear conditions may influence children’s gait compared with barefoot walking. Across studies, footwear exposure may be associated with changes in several biomechanical gait parameters; however, the direction and magnitude of these effects remain uncertain due to the sparse and heterogeneous evidence base. The exploratory meta-analyses for ankle plantarflexion and stride length yielded non-significant pooled estimates with wide prediction intervals and therefore should be interpreted only as descriptive summaries alongside the narrative synthesis.

Overall, the strongest evidence arises from the narrative synthesis, which suggests that conventional footwear may be associated with altered joint kinematics, modified plantar pressure patterns, and reduced forefoot mobility in some contexts, although results are not consistent across studies. Footwear with minimalist/biomimetic features (e.g., wider forefoot, low heel-to-toe drop, and increased multidirectional flexibility) may approximate barefoot-like values for selected parameters, but current evidence remains insufficient to support firm comparative conclusions or to assume equivalence with barefoot gait.

Certainty of evidence (narrative statement). Overall certainty of the evidence was low to moderate, primarily due to moderate-to-serious risk of bias in most studies (ROBINS-I), inconsistency/heterogeneity across outcomes and footwear definitions, and imprecision related to small sample sizes and limited comparable data for quantitative pooling. Accordingly, conclusions should be interpreted cautiously.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010286/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.-C., E.C.-L. and G.G.-N.; methodology, G.G.-N.; formal analysis, G.G.-N. and C.M.-C.; data curation, C.M.-C. and G.G.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.-C., E.C.-L. and G.G.-N.; writing—review and editing, all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) under the registration number: CRD42025628073.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zech, A.; Venter, R.; De Villiers, J.E.; Sehner, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Hollander, K. Motor Skills of Children and Adolescents Are Influenced by Growing up Barefoot or Shod. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, E.; Banwell, H.A.; Arnold, J.B. Children’s school footwear: The impact of fit on foot function, comfort, and jump performance in children aged 8 to 12 years. Gait Posture 2021, 87, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Elvira, J.L.; López Plaza, D.; López Valenciano, A.; Alonso Montero, C.A. Influencia del calzado en el movimiento del pie durante la marcha y la carrera en niños y niñas de 6 y 7 años (Influence of footwear on foot movement during walking and running in boys and girls aged 6–7). Retos 2016, 31, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.C.; Price, C.; McClymont, J.; Nester, C. Big issues for small feet: Developmental, biomechanical and clinical narratives on children’s footwear. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2018, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.; Healy, A.; Chockalingam, N. Key concepts in children’s footwear research: A scoping review focusing on therapeutic footwear. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2019, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yu, L.; Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; Mei, Q.; Gu, Y. Understanding the Role of Children’s Footwear on Children’s Feet and Gait Development: A Systematic Scoping Review. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch, M.; Mickle, K.J.; Munro, B.J.; Dowling, A.M.; Grau, S.; Steele, J.R. Do the feet of German and Australian children differ in structure? Implications for children’s shoe design. Ergonomics 2008, 51, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimunová, M.; Kolářová, K.; Vodička, T.; Bozděch, M.; Zvonař, M. How barefoot and conventional shoes affect the foot and gait characteristics in toddlers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273388. [Google Scholar]

- Khajooei, M.; Wochatz, M.; Baritello, O.; Mayer, F. Effects of shoes on children’s fundamental motor skills performance. Footwear Sci. 2020, 12, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chard, A.; Greene, A.; Hunt, A.; Vanwanseele, B.; Smith, R. Effect of thong style flip-flops on children’s barefoot walking and jogging kinematics. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2013, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, K.; De Villiers, J.; Venter, R.; Sehner, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Braumann, K.M.; Zech, A. Foot Strike Patterns Differ Between Children and Adolescents Growing up Barefoot vs. Shod. Int. J. Sports Med. 2018, 39, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, S.; Simon, J.; Patikas, D.; Schuster, W.; Armbrust, P.; Döderlein, L. Foot motion in children shoes—A comparison of barefoot walking with shod walking in conventional and flexible shoes. Gait Posture 2008, 27, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, S.M.; Fink, P.W.; Hume, P.; Shultz, S.P. Kinematic and kinetic differences between barefoot and shod walking in children. Footwear Sci. 2015, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morio, C.; Lake, M.J.; Gueguen, N.; Rao, G.; Baly, L. The influence of footwear on foot motion during walking and running. J. Biomech. 2009, 42, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, C.; Greene, A.; Burns, J.; Hunt, A.E.; Vanwanseele, B.; Smith, R.M. In-shoe multi-segment foot kinematics of children during the propulsive phase of walking and running. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 39, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.P.; Chung, M.J.; Wu, C.Y.; Cheng, K.W.; Wang, M.J. Comparison of Barefoot Walking and Shod Walking Between Children with and Without Flat Feet. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2015, 105, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeffinger, D.; Brauch, B.; Cranfill, S.; Hisle, C.; Wynn, C.; Hicks, R.; Augsburger, S. Comparison of gait with and without shoes in children. Gait Posture 1999, 9, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lythgo, N.; Wilson, C.; Galea, M. Basic gait and symmetry measures for primary school-aged children and young adults whilst walking barefoot and with shoes. Gait Posture 2009, 30, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidner, G.S.; Nascimento, R.B.; Aires, A.G.; Baptista, R.R. Barefoot walking changed relative timing during the support phase but not ground reaction forces in children when compared to different footwear conditions. Gait Posture 2021, 83, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okai-Nobrega, L.A.; Santos, T.R.T.; Lage, A.P.; Araújo, P.A.D.; Souza, T.R.; Fonseca, S.T. Efeitos do uso de calçado biomimético na marcha de crianças típicas. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2024, 59, e435–e442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plesek, J.; Hamill, J.; Blaschova, D.; Freedman-Silvernail, J.; Jandacka, D. Acute effects of footwear on running impact loading in the preschool years. Sports Biomech. 2023, 22, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hamme, A.; Samson, W.; Dohin, B.; Dumas, R.; Chèze, L. Is there a predominant influence between heel height, upper height and sole stiffness on young children gait dynamics? Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 16, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llana, S.; Brizuela1, G.; Dura, J.V.; Garcia, A.C. A study of the discomfort associated with tennis shoes. J. Sports Sci. 2002, 20, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, K.; Vorpahl, K.A.; Heiderscheit, B. Effect of cushioned insoles on impact forces during running. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2008, 98, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spears, I.R.; Miller-Young, J.E.; Sharma, J.; Ker, R.F.; Smith, F.W. The potential influence of the heel counter on internal stress during static standing: A combined finite element and positional MRI investigation. J. Biomech. 2007, 40, 2774–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zwaard, B.C.; Vanwanseele, B.; Holtkamp, F.; van der Horst, H.E.; Elders, P.J.; Menz, H.B. Variation in the location of the shoe sole flexion point influences plantar loading patterns during gait. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2014, 7, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurse, M.A.; Hulliger, M.; Wakeling, J.M.; Nigg, B.M.; Stefanyshyn, D.J. Changing the texture of footwear can alter gait patterns. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2005, 15, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.; Healy, A.; Chockalingam, N. Defining and grouping children’s therapeutic footwear and criteria for their prescription: An international expert Delphi consensus study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Morrison, S.C.; Paterson, K.; Gobbi, K.; Burton, S.; Hill, M.; Harber, E.; Banwell, H. Young children’s footwear taxonomy: An international Delphi survey of parents, health and footwear industry professionals. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, C.M.; Banwell, H.A.; Paterson, K.L.; Gobbi, K.; Burton, S.; Hill, M.; Harber, E.; Morrison, S.C. Parents, health professionals and footwear stakeholders’ beliefs on the importance of different features of young children’s footwear: A qualitative study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2022, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esculier, J.F.; Dubois, B.; Dionne, C.E.; Leblond, J.; Roy, J.S. A consensus definition and rating scale for minimalist shoes. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2015, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranage, S.; Banwell, H.; Williams, C.M. Gait and Lower Limb Observation of Paediatrics (GALLOP): Development of a consensus based paediatric podiatry and physiotherapy standardised recording proforma. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2016, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.M.; Farlie, M.; Kolic, J.; Morrison, S.C.; Paterson, K.; Hill, M.; Bonacci, J.; Breet, M.C.; Cranage, S.; Caswell, S.V.; et al. Development of the CHILD-SHOE Reporting Checklist: A Scoping Review and Modified Delphi Study to Support Reporting in Children’s Footwear Research. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2025, 18, e70065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROBINS-I: A Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies of Interventions. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309098187_ROBINS-I_A_tool_for_assessing_risk_of_bias_in_non-randomised_studies_of_interventions (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Mahaffey, R.; Le Warne, M.; Blandford, L.; Morrison, S.C. Age-related changes in three-dimensional foot motion during barefoot walking in children aged between 7 and 11 years old. Gait Posture 2022, 95, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollander, K.; De Villiers, J.E.; Sehner, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Braumann, K.M.; Venter, R.; Zech, A. Growing-up (habitually) barefoot influences the development of foot and arch morphology in children and adolescents. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aibast, H.; Okutoyi, P.; Sigei, T.; Adero, W.; Chemjor, D.; Ongaro, N.; Fuku, N.; Konstabel, K.; Clark, C.; Lieberman, D.E.; et al. Foot Structure and Function in Habitually Barefoot and Shod Adolescents in Kenya. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, J.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Maeda, K.; Shibata, A.; Kaneko, J.; Ohyama-Byun, K.; Ogata, M. Long-term effects of school barefoot running program on sprinting biomechanics in children: A case-control study. Gait Posture 2021, 83, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizushima, J.; Seki, K.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Maeda, K.; Shibata, A.; Koyama, H.; Ohyama-Byun, K. Kinematic characteristics of barefoot sprinting in habitually shod children. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.S.Y. The balance control of young children under different shod conditions in a naturalistic environment. Gait Posture 2019, 68, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranage, S.; Bowles, K.A.; Perraton, L.; Williams, C. The impact of hard versus soft soled runners on the spatio-temporal measures of gait in young children and a comparison to barefoot walking. Footwear Sci. 2019, 11, S109–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillstrom, H.J.; Buckland, M.A.; Slevin, C.M.; Hafer, J.F.; Root, L.M.; Backus, S.I.; Kraszewski, A.P.; Whitney, K.A.; Scher, D.M.; Song, J.; et al. Effect of shoe flexibility on plantar loading in children learning to walk. J. Am. Podiatr. Med. Assoc. 2013, 103, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellis, E. Plantar pressure distribution during barefoot standing, walking and landing in preschool boys. Gait Posture 2001, 14, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cranage, S.; Perraton, L.; Bowles, K.A.; Williams, C. A comparison of young children’s spatiotemporal gait measures in three common types of footwear with different sole hardness. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okai-Nobrega, L.A.; Santos, T.R.T.; Lage, A.P.; Araújo, P.A.D.; Souza, T.R.D.; Fonseca, S.T. A influência de calçados no arco longitudinal medial do pé e na cinemática dos membros inferiores de crianças no início da fase de aquisição de marcha. Rev. Bras. Ortop. 2022, 57, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breet, M.C.; de Villiers, J.E.; Venter, R. South African School Shoes: Urgent Changes Required for Our Children’s Unique Feet. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2023, 119, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Kasuga, K.; Hanai, T.; Demura, T.; Komura, K. The effect of the kindergarten barefoot policy on preschool children’s toes. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2017, 36, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbaut, A.; Chavet, P.; Roux, M.; Guéguen, N.; Gillet, C.; Barbier, F.; Simoneau-Buessinger, E. The influence of shoe drop on the kinematics and kinetics of children tennis players. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2016, 16, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; McSweeney, S.C.; Hollander, K.; Horstman, T.; Wearing, S.C. Adolescents running in conventional running shoes have lower vertical instantaneous loading rates but greater asymmetry than running barefoot or in partial-minimal shoes. J. Sports Sci. 2023, 41, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.