Abstract

Background: Digital indirect bonding (IB) has emerged as a reliable approach to improving the precision and efficiency of orthodontic bracket placement. Methods: This in vitro study evaluated and compared the positional accuracy and efficiency of two digitally driven indirect bonding (IB) techniques—a rigid single-tooth transfer jig (Leone Jig System) and a flexible three-part transfer tray (IBT Flex Resin)—as well as conventional direct bonding. Ten sets of 3D-printed resin dental models were randomly allocated to the three bonding protocols. Bracket positions were virtually planned and analyzed by superimposing pre- and post-bonding STL models using landmark- and surface-based registration. Linear discrepancies were measured along the axial, sagittal, and vertical planes, and data were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVA and Friedman tests (α = 0.05). Results: Both indirect bonding techniques showed significantly smaller deviations from the ideal virtual setup compared with direct bonding across all spatial planes (p < 0.001). Mean discrepancies were consistently below 0.3 mm for the indirect protocols, compared with values exceeding 0.4 mm for direct bonding. The rigid jig demonstrated the highest precision, particularly in the sagittal (0.18 ± 0.06 mm) and vertical (0.21 ± 0.07 mm) planes, while the flexible tray showed slightly higher deviations (approximately 0.25–0.30 ± 0.08–0.09 mm across planes). Chairside bonding time per full arch was reduced by more than 50% with both IB techniques, with the jig-based system being the most time-efficient. No significant interaction between bonding method and spatial plane was observed. Conclusions: Within the limitations of this in vitro study, digital indirect bonding—especially rigid, patient-specific jigs—demonstrated superior bracket placement accuracy and procedural efficiency compared with direct bonding.

1. Introduction

Recent advances in digital technology have profoundly transformed contemporary orthodontic workflows [1], especially regarding bracket placement accuracy, operational efficiency, and overall treatment predictability [2]. Precise bracket positioning remains a fundamental requirement for achieving optimal functional and esthetic outcomes at the end of orthodontic therapy [3]. Clinical success depends on a precise diagnosis, individualized planning, and careful management of bracket placement, all essential for even distribution of occlusal forces and long-term dental stability [4].

The traditional direct bonding (DB) technique demands substantial operator skill and detailed anatomical knowledge [5,6]. However, clinical challenges—including individual anatomical variability, the presence of malocclusions, and operator error—can compromise the accuracy of bracket positioning, particularly during leveling and during insertion of rectangular archwires [7]. Positional inaccuracies may result in extended treatment times, the need for rebracketing, and suboptimal clinical outcomes.

To overcome these limitations, the indirect bonding (IB) technique, introduced in the 1970s, introduces a laboratory phase: brackets are placed on a physical or virtual model and then transferred to the dental arch via customized transfer appliances [8,9,10]. Various types of transfer trays have been developed, ranging from thermoplastic or silicone materials to sophisticated CAD/CAM devices, with different rigidity and flexibility profiles [11,12]. One of the main advantages of IB is the significant reduction in chairside time during bracket placement—a benefit for both clinicians and patients [6]. While IB can improve reproducibility, ergonomics, and workflow efficiency, the literature also reports minor but sometimes clinically significant deviations between planned and actual bracket positions [13,14]. Consequently, the improved workflow and time savings may not consistently offset the added laboratory and material costs associated with indirect bonding, especially in cases where the clinical advantage over direct bonding is limited in certain spatial planes [6].

The advent of CAD/CAM software has improved planning accuracy and enabled fabrication of highly individualized transfer devices, improving the accuracy of the indirect bonding step [13,14,15]. Nonetheless, systematic comparisons between different digital indirect bonding systems—especially those differing in design and material properties—remain limited, particularly regarding the precise transfer of prefabricated brackets with devices of various physical-mechanical characteristics and segmentations [16,17]. Moreover, design variables such as device rigidity or segmentation may influence transfer performance, particularly under moderate–severe crowding [18,19].

There is thus a clear need for rigorous comparative evidence on the accuracy, efficiency, and practical limitations of indirect bonding protocols with different materials and geometries, particularly in digitally driven orthodontic workflows.

Accordingly, an in vitro study was designed to address this gap.

The aim was to compare two representative indirect bonding techniques—a digitally designed, rigid single-tooth transfer jig (“Leone Jig System”) and a flexible multipart transfer tray manufactured by 3D printing for arch sections (“IBT Flex Resin tray”)—in terms of bracket transfer accuracy and chairside efficiency.

By systematically quantifying linear and angular transfer discrepancies and procedural times, the analysis sought to identify design-related factors influencing accuracy in contemporary digital orthodontics.

The null hypothesis stated that no statistically significant differences would be observed among the evaluated bonding techniques in any spatial dimension or in bonding time.

2. Materials and Methods

This manuscript was prepared in accordance with the CRIS (Checklist for Reporting In Vitro Studies) guidelines to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility [20].

Study Design

An in vitro comparative experimental study was conducted to evaluate the accuracy of bracket position transfer using two digital indirect bonding techniques relative to a direct bonding reference on printed models. The study was performed at the Department of Surgical Sciences, School of Specialization in Orthodontics, University of Cagliari, and at a private dental clinic in Soleto, Italy, between April and November 2024.

Sample Size and Selection

The sample comprised ten anonymized STL dental arch files (one per patient), including both maxillary and mandibular arches, selected from a database (Studio Dentistico Grecolini, Soleto, Italy). Inclusion criteria were: (1) presence of a permanent dentition (excluding second and third molars); (2) complete eruption of all teeth; (3) mild to moderate crowding; and (4) absence of prior orthodontic treatment by the investigators.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) mixed dentition; (2) partially erupted teeth; (3) severe crowding requiring complex bracket repositioning; and (4) dental arch characteristics potentially interfering with standardized digital planning and indirect bonding workflows.

For each case, three identical resin models were fabricated—one for each experimental group—yielding 30 models in total. Models were fabricated using Formlabs Model Resin V3 (Formlabs Model Resin V3 (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA) on a Form 3B Plus SLA 3D printer (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA). After printing, the models were washed in isopropyl alcohol using the FormWash system (Formlabs Inc.) for two cycles of ten minutes each, then air-dried and post-cured in a FormCure unit (Formlabs Inc.) at 60 °C for 30 min. All finished models were stored in a dry, dark box until use. Detailed technical specifications of materials and manufacturing equipment are summarized in Supplementary Materials. No a priori power calculation was performed due to the in vitro, pilot-comparative design; sample size conformed to prior studies with similar designs [16,17,21]. Written informed consent for research use of patient data was obtained in all cases.

Group Allocation

Each subject’s STL file was used to design and 3D print three identical resin models. The resin models were printed using Precision Model Resin (Formlabs Inc., Somerville, MA, USA), a high-accuracy material optimized for dental applications The models were randomly allocated (1:1:1) using a computer-generated simple randomization sequence to one of three experimental groups.

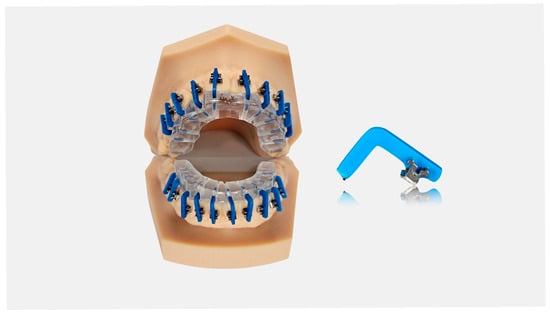

Group 1 (Jig-based indirect bonding). In this group, indirect bonding was performed using the Leone Jig System. Bracket positioning was digitally planned using dedicated indirect bonding software (Indirect Bonding Leone, Leone S.p.A., Sesto Fiorentino, FI, Italy), with subsequent customization or optimization performed by the operator. Patient-specific transfer jigs were produced at the Marco Pozzi Biotechnological Research Center (Leone S.p.A.) using high-precision PolyJet 3D printing (Objet Connex350, Stratasys Ltd., Rehovot, Israel) with MED610 medical-grade resin (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Example of the rigid single-tooth transfer jig (“Leone Jig System”) used for indirect bonding. The figure is provided for illustrative purposes and does not represent quantitative data from the study sample.

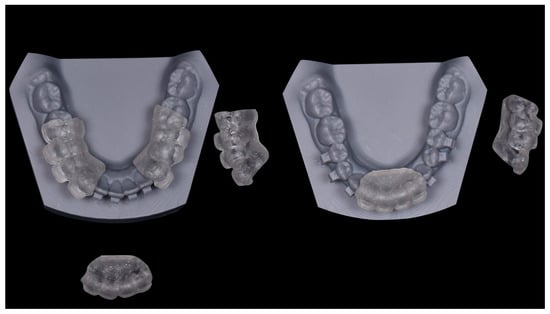

Group 2 (Flexible tray indirect bonding). In this group, indirect bonding was performed using a personalized tripartite IBT Flex Resin tray. Bracket positioning was digitally planned using the same indirect bonding software used for Group 1. The three-part transfer trays were manufactured by Smileline Technology (Mola di Bari, BA, Italy) via SLA 3D printing (Form 4, Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) using IBT Flex Resin (Formlabs) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example of the flexible three-part transfer tray (IBT Flex Resin, Formlabs) used for indirect bonding. The figure is provided for illustrative purposes and does not represent quantitative data from the study sample.

Group 3 (Direct bonding). In this reference group, brackets were positioned and bonded directly onto the resin models according to the digital treatment plan.

All brackets used in the study were metallic Edgewise STEP SYSTEM 2.0 brackets (0.022” × 0.028”; Leone S.p.A.).

Intervention

Bonding procedures were standardized across all groups and performed using Transbond XT adhesive and Transbond Primer (3M Unitek, Monrovia, CA, USA). Primer was applied in a thin layer to the buccal surfaces of the resin models using a microbrush, and brackets were loaded with a minimal amount of adhesive. Excess resin was carefully removed with a scaler prior to light curing to minimize seating interference.

Initial light curing was carried out using a VALO LED curing unit (Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, USA) for approximately 20 s at 1400 mW/cm2 in high-power mode, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

In Group 1, each bracket was inserted into its corresponding positioning jig, and the jig–bracket assembly was seated on the vestibular surface of the resin model, followed by a second light-curing cycle of approximately 20 s.

In Group 2, the three-part flexible tray was positioned with gentle buccal pressure; excess adhesive was removed as needed using a low-speed round bur, and each quadrant was cured individually for approximately 20 s.

In Group 3, brackets were placed and bonded individually onto the resin model surfaces according to the digital treatment plan.

Brackets were bonded across 30 resin models; molar tubes were excluded due to limitations of the digital bracket library. All bonding procedures were performed by a single operator, and all measurements and evaluations were conducted by a single examiner who was blinded to group allocation.

Digital Acquisition and Measurement

After bonding and tray/jig removal, an anti-reflection spray (Dr Mat Dental CAD/CAM scan white spray; Mat Chemical Industrial Productions, Istanbul, Turkey) was evenly applied to each model’s buccal surface to optimize digital scanning [21]. Post-transfer, all models were scanned with an iTero Element 2 intraoral scanner (Align Technology, San Jose, CA, USA) by the same operator following a standardized scanning path (right posterior → left posterior). Each final STL was reviewed for scanning artifacts.

For analytical measurement, both the initial digital/virtual STLs and scanned post-bonding models were loaded into Blue Sky Plan software (Blue Sky Bio, LLC, Grayslake, IL, USA). A patient-specific Cartesian coordinate system was defined (X: mesio-distal; Y: bucco-lingual; Z: occluso-gingival); positive directions were standardized a priori. Models were aligned through anatomical landmarks: for the upper arch, the third palatal ruga and mesiobuccal cusps of right and left first molars; for the lower arch, mesiobuccal cusps of right and left first molars.

Following landmark alignment, best-fit surface registration was performed. The software then generated color-coded maps displaying the magnitude and distribution of transfer errors. For each bracket, three reference points were manually identified and deviations measured in the sagittal, axial, and vertical planes, expressed in μm. Similar three-dimensional superimposition and measurement approaches have been previously reported in studies evaluating the transfer accuracy of orthodontic bracket bonding techniques [16,17,21]. Ten percent of brackets were re-measured after 14 days to assess intra-observer reliability; agreement was quantified using ICC (two-way mixed, absolute agreement).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data distribution and homoscedasticity were assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively.

For within-subject comparisons among bonding techniques across spatial planes, repeated-measures ANOVA was applied when data met parametric assumptions; otherwise, the Friedman test was used. Post hoc analyses were performed using Bonferroni or Dunn’s corrections, as appropriate.

Pairwise non-parametric comparisons were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test when required. Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d for parametric analyses and Kendall’s W for non-parametric analyses.

The effects of bonding technique, spatial plane, and their interaction were further evaluated using a two-way repeated-measures ANOVA.

Bonding time differences among techniques were assessed using one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Ethical Considerations

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and used fully anonymized STL reconstructions from a pre-existing, consented archive. No living subjects were involved; therefore, specific institutional review board approval was not required. No identifiable information was available to investigators.

3. Results

A total of 597 brackets were bonded across 30 resin models, with equal allocation to each experimental group. Three bonded brackets were excluded from the final analysis due to technical limitations encountered during digital scanning and three-dimensional superimposition, which prevented reliable quantitative assessment.

Statistical analysis identified the bonding method as the primary factor influencing spatial accuracy, explaining 88.7% of total variance (p < 0.0001); the spatial plane accounted for 1.4% (p = 0.046), and no significant method-by-plane interaction was detected (p = 0.18) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of bonding method and spatial plane on bracket positioning deviations.

For both indirect bonding techniques, deviations from the ideal virtual bracket position were significantly smaller than those observed with direct bonding across all spatial planes (Table 2). The largest differences were observed in the sagittal plane, followed by statistically significant differences in the axial and vertical planes. Mean deviations across planes ranged below 150 µm.

Table 2.

Differences in bracket positioning deviations from the ideal virtual setup between indirect and direct bonding techniques across spatial planes.

Direct comparison of the two indirect techniques showed statistically significant differences favoring the jig-based system (“Leone Jig System”) in the sagittal and vertical planes (p < 0.05). No significant difference was detected in the axial dimension. Effect size analyses (Cohen’s d, Kendall’s W) are reported in Table 1 and Table 2.

Bonding time differed significantly among groups (p < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA; Table 2). The direct technique required the longest mean time (1716 ± 256 s), followed by the flexible tray (1136 ± 139 s), whereas the jig-based approach was the fastest (784 ± 163 s), with all between-group differences highly significant (p < 0.0001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean bonding time for each bonding technique.

4. Discussion

This in vitro investigation supports existing evidence indicating that digital indirect bonding techniques result in smaller deviations from the ideal virtual bracket position compared with conventional direct bonding. Both protocols tested—the individualized, rigid “Leone Jig System” and the flexible multipart IBT Flex tray—demonstrated significant improvements, with the jig-based system showing the highest precision, particularly in the sagittal and vertical planes, alongside a marked reduction in chairside bonding time [22,23]. These findings are consistent with the rejection of the null hypothesis, confirming statistically significant differences among the bonding techniques.

The reduced deviations from the ideal virtual bracket position observed with indirect bonding compared with direct bonding align with prior studies which have emphasized the technical limitations of direct bonding—especially under variable dental morphology and limited clinical visibility [7,8]. These conditions predispose to greater bracket misplacements, necessitating post-bonding corrections and lengthening clinical sessions. Indirect methods mitigate these issues by allowing meticulous lab-based planning and fabrication of transfer templates, resulting in greater reproducibility and efficiency [10,15].

The systematic reviews and meta-analyses that have examined this topic in detail further confirm these findings [9,13,14,15]. For example, recent comprehensive meta-analyses report that indirect bonding consistently reduces bracket positioning errors and enhances transfer reproducibility, while also reducing clinical chairside time and patient discomfort [13,19]. Collectively, these studies highlight the clinical relevance of precise bracket placement as a determinant of treatment success and efficiency.

Our comparison between a flexible tray and a rigid jig reflects important clinical considerations regarding bonding tray design and effectiveness. Flexible trays are frequently adopted in clinical practice for their adaptability to the natural contours and anatomical variability of the dental arch, particularly in crowded or malaligned segments. This adaptability can facilitate easier placement and seating of the tray, reducing patient discomfort and chair time. Jungbauer et al. (2021) emphasized that increased tray rigidity may compromise accuracy in cases of severe crowding due to limited accommodation of tooth positioning variation, which can lead to bracket misplacement if the tray does not fully seat [18]. To mitigate this confounding effect, our study specifically selected models with moderate crowding, allowing a more controlled comparison between tray designs. By restricting the sample to moderately crowded arches, the present study minimized seating bias and ensured that tray performance reflected intrinsic design differences rather than anatomical constraints.

Despite the advantages of flexibility, the rigid jig provides crucial functional benefits by stabilizing bracket positioning during transfer. Its patient-specific digital design distributes placement forces evenly, limiting bracket displacement and unwanted rotation. This increased mechanical control reduces angular deviations, particularly in torque and rotation, which are vital for precise tooth movement and correct occlusal relationships. This mechanical stability may explain the superior sagittal and vertical accuracy observed for the jig-based system in the present results. From a clinical perspective, deviations in the order of a few tenths of a millimeter may appear limited; however, even small sagittal or vertical inaccuracies can affect torque expression, finishing efficiency, and the need for subsequent bracket repositioning, particularly within digitally planned orthodontic workflows.

Our findings align with recent evidence that rigid customized trays minimize bracket positional errors and decrease the need for repositioning after bonding, highlighting their practical value in orthodontic procedures [11,19]. This balance between adaptability and stability is essential for optimizing bracket placement accuracy and clinical outcomes.

The literature continues to investigate the influence of 3D-printed indirect bonding tray designs on transfer accuracy [16,24]. Studies comparing one-piece versus segmented trays generally report comparable linear accuracy; however, angular deviations remain a primary concern, impacting clinical outcomes. Campobasso et al., in their comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis, highlight that segmented trays—often incorporating arm-like or “L” shaped support structures—significantly improve angular control during transfer by stabilizing brackets more effectively. Such design features reduce unwanted rotations and torque movements that are challenging to control with conventional full-arch or flexible trays [13]. Their findings are supported by comparative studies demonstrating that segmented and partially enclosed trays better maintain bracket position, especially over anatomically complex regions such as incisors and canines, thus decreasing errors beyond linear dimensions [11,18,25]. This technological advancement in tray segmentation and geometry represents a promising avenue to balance mechanical stability with clinical ease of application in modern digital orthodontic workflows.

Measurement methodology remains a critical factor influencing reported accuracy in orthodontic bracket transfer studies. Various analytical approaches have been employed, ranging from landmark-based point measurements on specific bracket features such as wings and hooks, to virtual wire slot alignment techniques that evaluate positional deviation independent of bracket morphology [16,21,26]. Our study employed STL data superimposition using stable anatomical reference points on the dental models, combined with measurements incorporating the entire bracket form, including wings and hooks, enabling a robust and comprehensive three-dimensional assessment of positional accuracy. This protocol aligns with current best practices for 3D superimposition, emphasizing anatomical fidelity and observer reliability in bracket position quantification [21].

Clinical scanning of metallic brackets poses specific challenges due to light reflection caused by the metal surfaces, which can generate imaging artifacts affecting digital accuracy [27]. To minimize this limitation, a uniform anti-reflective coating was applied on all models’ surfaces, markedly improving scan data quality and measurement reliability, consistent with recommendations by Eglenen and Karabiber [28]. Similar studies corroborate that scanning artefacts can be minimized through this method, enhancing the accuracy of virtual models used for bracket position analysis. Furthermore, while ceramic brackets inherently produce fewer reflections, their higher cost and mechanical properties limit their widespread clinical use [21]. Ensuring reliable scanner performance and optimizing surface preparation techniques remain pivotal to accurate digital assessments in orthodontic research. This step proved essential to obtain artifact-free scans and reliable deviation maps, as also demonstrated by previous digital accuracy studies [27,28].

The reduction in bonding time observed with the jig-based system aligns with prior evidence, demonstrating significant procedural time savings with digital indirect bonding techniques without sacrificing accuracy. Campobasso et al. [13], in their systematic review and meta-analysis, highlighted the improved clinical efficiency of digital indirect bonding due to streamlined transfer protocols. This is supported by Wang et al. [29], who conducted a prospective clinical study comparing traditional direct bonding with computer-aided indirect bonding, reporting significantly reduced chairside duration with the latter method, contributing to enhanced patient comfort and clinical workflow optimization. Furthermore, Palone et al. [11] showed that 3D-printed jig-based systems noticeably decrease operator working time by minimizing bracket repositioning and adhesive cleanup. These findings align with prior evidence showing that digital workflows reduce chairside bonding time by limiting the need for bracket repositioning and adhesive handling [17]. From a clinical management perspective, these efficiencies translate into greater scheduling flexibility, reduced operator fatigue, and improved overall workflow quality.

The absence of a significant interaction between bonding method and spatial plane suggests that differences among bonding techniques were not dependent on spatial direction. This finding indicates that digital indirect bonding techniques reliably minimize bracket positional errors in the sagittal, vertical, and transverse planes, which are essential for precise control of tooth movement and treatment outcomes. Multiple studies have highlighted that precision in these spatial dimensions fundamentally influences treatment effectiveness, as inaccuracies in torque, angulation, or in-out positioning can lead to suboptimal occlusion or treatment prolongation [11,13]. Our results confirm that well-designed digital indirect bonding workflows can overcome traditional challenges associated with direct bonding, such as limited clinical visibility and difficulty in maintaining bracket stability during transfer. The spatial consistency observed also supports improved treatment predictability and may reduce the need for prolonged appliance adjustments and refinements, thereby optimizing the overall orthodontic workflow and patient experience.

Limitations

Despite methodological rigor, the in vitro design limits generalization to clinical conditions. Real-life variables such as saliva, intraoral anatomical constraints, patient movement, and operator variability were not simulated, yet these factors significantly influence bonding effectiveness and precision within the oral environment. For instance, moisture control and limited access, especially in posterior segments, can complicate bonding procedures, affecting transfer accuracy and outcomes [13]. The exclusion of molars and associated tubes reduces applicability to full-arch bonding scenarios and clinical challenges warranting future in vivo work. Additionally, the operator in this study possessed high expertise and skill, which may skew results toward greater accuracy than achievable in general practice. Clinician experience significantly affects bonding success and precision, underscoring the need for multicenter clinical trials incorporating diverse operators to validate and generalize these findings [5]. Future in vivo investigations should therefore assess these digital transfer systems under routine clinical variables such as humidity, limited visibility, and patient movement.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, the findings of this in vitro investigation indicate that:

- Digital indirect bonding techniques demonstrated significantly smaller deviations from the ideal virtual bracket position compared with conventional direct bonding.

- Among the evaluated protocols, the rigid Leone Jig System showed the highest transfer accuracy, particularly in the sagittal and vertical planes.

- Both indirect bonding approaches resulted in greater procedural efficiency, with a substantial reduction in chairside bonding time compared with direct bonding.

- No significant interaction between bonding method and spatial plane was observed, indicating consistent performance across spatial dimensions.

In summary, digital indirect bonding—particularly when using rigid, patient-specific jigs—enhances both the precision and efficiency of orthodontic bracket placement compared with direct techniques. Future clinical studies are warranted to validate these findings under in vivo conditions and to explore the influence of operator variability, intraoral factors, and long-term treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010285/s1, Table S1: Detailed technical specifications of materials and manufacturing equipment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.N. and M.E.G.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.B. and A.U.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, C.N.; resources, M.C., A.U. and V.L.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.N. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., A.A. and A.U.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.U. and V.L.; project administration, A.U. and E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study complied with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and used fully anonymized STL reconstructions from a pre-existing, consented archive. No living subjects were involved; therefore, specific institutional review board approval was not required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Francisco, I.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Marques, F.; Travassos, R.; Nunes, C.; Pereira, F.; Caramelo, F.; Paula, A.B.; Vale, F. Application of three-dimensional digital technology in orthodontics: The state of the art. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Ueno, E.P.; de Carvalho, T.C.A.d.S.G.; Kanashiro, L.K.; Ursi, W.; Chilvarquer, I.; Neto, J.R.; de Paiva, J.o.B. Evaluation of the accuracy of digital indirect bonding vs. conventional systems: A randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod. 2025, 95, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.K.; Abutayyem, H.; Almaslamani, M.J.; Odeh, R. Bracket positioning have an impact on smile arc protection–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bangladesh J. Med. Sci. 2025, 24, 984–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bokle, D.; Ahmed, F. Bracket positioning in orthodontics: Past and present. AJO-DO Clin. Companion 2023, 3, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.; Shen, G.; Petocz, P.; Darendeliler, M. Accuracy of bracket placement by orthodontists and inexperienced dental students. Aust. Orthod. J. 2007, 23, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czolgosz, I.; Cattaneo, P.M.; Cornelis, M.A. Computer-aided indirect bonding versus traditional direct bonding of orthodontic brackets: Bonding time, immediate bonding failures, and cost-minimization. A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 43, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K.; Saglam-Aydinatay, B. Comparative assessment of treatment efficacy and adverse effects during nonextraction orthodontic treatment of Class I malocclusion patients with direct and indirect bonding: A parallel randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 26–34.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, E.; Cohen, M.; Gianelly, A.A.; Dietz, V.S. A universal direct bonding system for both metal and plastic brackets. Am. J. Orthod. 1972, 62, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mei, L.; Wei, J.; Yan, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, W.; Li, Y. Effectiveness, efficiency and adverse effects of using direct or indirect bonding technique in orthodontic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondhi, A. Efficient and effective indirect bonding. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1999, 115, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palone, M.; Koch, P.-J.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.-G.; Spedicato, G.A.; Verducci, A.; Pieralli, P.; Lombardo, L. Accuracy of indirect bracket placement with medium-soft, transparent, broad-coverage transfer trays fabricated using computer-aided design and manufacturing: An in-vivo study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 163, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalange, J.T. Prescription-based precision full arch indirect bonding. In Seminars in Orthodontics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 19–42. [Google Scholar]

- Campobasso, A.; Battista, G.; Fiorillo, G.; Caldara, G.; Lo Muzio, E.; Ciavarella, D.; Gastaldi, G.; Muzio, L.L. Transfer Accuracy of 3D-Printed Customized Devices in Digital Indirect Bonding: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 5103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakdach, W.M.M.; Hadad, R. Linear and angular transfer accuracy of labial brackets using three dimensional-printed indirect bonding trays: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Orthod. 2022, 20, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhafi, Z.M.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Alam, M.K.; Jaber, S.; Jaber, S.T. Effectiveness and efficiency of indirect bonding techniques: An umbrella review with meta-analysis of the pooled findings. Int. Orthod. 2025, 23, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasenapp, J.v.; Hofmann, E.; Süpple, J.; Jost-Brinkmann, P.-G.; Koch, P.J. Comparison of two 3D-printed indirect bonding (IDB) tray design versions and their influence on the transfer accuracy. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, K.-J.; Nelson, G. Three-dimensional evaluation of the transfer accuracy of a bracket jig fabricated using computer-aided design and manufacturing to the anterior dentition: An in vitro study. Korean J. Orthod. 2021, 51, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungbauer, R.; Breunig, J.; Schmid, A.; Hüfner, M.; Kerberger, R.; Rauch, N.; Proff, P.; Drescher, D.; Becker, K. Transfer accuracy of two 3D printed trays for indirect bracket bonding—An in vitro pilot study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.-H.; Choi, S.-H.; Kim, K.-M.; Lee, K.-J.; Kim, Y.-J.; Yu, J.-H.; Choi, Y.-I.; Cha, J.-Y. Accuracy of 3-dimensional printed bracket transfer tray using an in-office indirect bonding system. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 93–102.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krithikadatta, J.; Gopikrishna, V.; Datta, M. CRIS Guidelines (Checklist for Reporting In-vitro Studies): A concept note on the need for standardized guidelines for improving quality and transparency in reporting: In-vitro: Studies in experimental dental research. J. Conserv. Dent. Endod. 2014, 17, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.E.A.; Gribel, B.F.; Spitz, A.; Artese, F.; Miguel, J.A.M. Reproducibility of digital indirect bonding technique using three-dimensional (3D) models and 3D-printed transfer trays. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauer, D.; Wiechmann, D.; Heymann, G.C.; SWIFT, J.; EDWARD, J. Computer-aided design/computer-aided manufacturing technology in customized orthodontic appliances. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2012, 24, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.W.; Koroluk, L.; Ko, C.-C.; Zhang, K.; Chen, M.; Nguyen, T. Effectiveness and efficiency of a CAD/CAM orthodontic bracket system. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2015, 148, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, W.; Xiao, L. Comparison of the transfer accuracy of two digital indirect bonding trays for labial bracket bonding. Angle Orthod. 2021, 91, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gia, K.Y.; Dunn, W.J.; Taloumis, L.J. Shear bond strength comparison between direct and indirect bonded orthodontic brackets. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 124, 577–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Chun, Y.-S.; Kim, M. Accuracy of bracket positions with a CAD/CAM indirect bonding system in posterior teeth with different cusp heights. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, S.-H.; Choi, T.-H.; Yen, E.H.; Zou, B.; Shin, Y.; Lee, N.-K. Accuracy of intraoral scan images in full arch with orthodontic brackets: A retrospective in vivo study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 4861–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eglenen, M.N.; Karabiber, G. Comparison of 1-and 3-piece directly 3-dimensional printed indirect bonding trays: An in vitro study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2024, 166, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Shi, X.; Cheng, W.-P.; Ma, F.-H.; Cheng, S.-M.; Kang, X. Clinical Study on Efficiency of Using Traditional Direct Bonding or OrthGuide Computer-Aided Indirect Bonding in Orthodontic Patients. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 9965190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.