Abstract

Anomaly detection in financial transactions is a challenging task, primarily due to severe class imbalance and the adaptive behavior of fraudulent activities. This paper presents a reinforcement learning framework for fraud detection (RLFD) to address this problem. We train a deep Q-network (DQN) agent with a long short-term memory (LSTM) encoder to process sequences of financial events and identify anomalies. On a proprietary, highly imbalanced dataset, 10-fold cross-validation highlights a distinct trade-off in performance. While a gradient boosted trees (GBT) baseline demonstrates superior global ranking capabilities (higher ROC and PR AUC), the RLFD agent successfully learns a high-recall policy directly from the reward signal, meeting operational needs for rare event detection. Importantly, a dynamic orthogonality analysis proves that the two models detect distinct subsets of fraudulent activity. The RLFD agent consistently identifies unique fraudulent transactions that the tree-based model misses, regardless of the decision threshold. Even at high-confidence operating points, the RLFD agent accounts for nearly 30% of the detected anomalies. These results suggest that while tree-based models offer high precision for static patterns, RL-based agents capture sequential anomalies that are otherwise missed, supporting for a hybrid, parallel deployment strategy.

1. Introduction

The detection of fraudulent activities in financial data represents a critical and persistent challenge, primarily due to the severe class imbalance of datasets and the dynamic, adaptive nature of fraudulent activities, as outlined in comprehensive reviews such as Compagnino et al. (2025) [1], Hernandez Aros et al. (2024) [2], Ali et al. (2022) [3], Al-Hashedi and Magalingam (2021) [4], and others [5,6,7,8]. Financial fraud is multifaceted, encompassing schemes from credit card and insurance fraud to sophisticated money laundering and emerging typologies like authorized push payment (APP) fraud [1]. Many of these schemes are not isolated events but are composed of sequences of actions designed to appear legitimate. For example, money muling involves chains of transactions across multiple accounts to obscure the origin of funds, while account takeover (ATO) fraud may be preceded by a series of unusual login activities.

Traditional machine learning models, such as Gradient Boosted Trees (GBTs) or Random Forests, typically treat transactions as independent tabular data points. While effective for static classification, this independence assumption renders them inherently blind to the temporal correlations and sequential patterns characteristic of sophisticated fraud. As recent empirical studies have demonstrated [1], this limitation often results in low detection rates for rare fraudulent events, necessitating the exploration of fundamentally different paradigms such as Reinforcement Learning (RL).

In this work, we present the Reinforcement Learning for Fraud Detection (RLFD) framework. We position this contribution not as a novel deep learning architecture, but as a domain-specific adaptation of the existing RLAD framework (Reinforcement Learning for Anomaly Detection) [9], specifically engineered for the constraints of banking transaction streams. The innovation of this study lies in the adaptation of the existing formulation, specifically the client-centric state windowing and asymmetric reward shaping, to address the severe class imbalance and operational costs of financial fraud. We hypothesize that this targeted adaptation enables the agent to capture sequential behavioral patterns that remain invisible to the static classifiers currently dominating the industry.

To investigate this hypothesis and assess the operational value of the framework, this study addresses the following research questions:

- Can a sequential reinforcement learning agent, trained with asymmetric rewards, achieve superior detection rates (recall) for rare fraudulent events compared to traditional static baselines in highly imbalanced financial datasets?

- Does the RLFD framework detect a distinct subset of fraudulent activities compared to tree-based models, thereby providing orthogonal and complementary operational value?

- To what extent does the sequential RL approach generalize to standard public benchmarks that lack strong temporal dependencies, compared to state-of-the-art static classifiers?

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

The application of machine learning to financial fraud detection has evolved significantly, transitioning from rule-based expert systems to sophisticated statistical learning algorithms. This section reviews the existing scholarship regarding static classification methods, the challenges of imbalanced sequential data, and the emergence of reinforcement learning as a viable alternative for anomaly detection.

2.1. Supervised Learning and Class Imbalance

Traditional supervised learning algorithms, particularly ensemble methods such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosted Trees (GBTs), represent the current industrial standard for fraud detection [1,10]. These models excel at capturing non-linear interactions between features in tabular data. However, their standard formulation relies on the independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) assumption, treating each transaction as an isolated event. This limitation is relevant in financial contexts, where fraudulent behavior often manifests as a sequence of actions rather than a single anomalous data point [5].

Furthermore, the extreme class imbalance characterizing financial datasets (typically < 5% fraud rate) poses a severe theoretical challenge. Standard objective functions tend to bias the model towards the majority class to maximize global accuracy [3,4]. As demonstrated by Compagnino et al. (2025) [1] on the same proprietary banking dataset used in this study, ensemble methods often struggle to achieve high recall without generating excessive false positives; in their benchmark, a Random Forest model achieved a fraud recall of only 0.36, highlighting the need for alternative approaches.

2.2. Deep Learning and Sequence Modeling

To address the temporal limitations of static models, Deep Learning architectures such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have been adopted to model transaction sequences [11]. LSTMs are theoretically well-suited for this domain because they maintain an internal state that can capture long-term dependencies. However, in a purely supervised setting, LSTMs are typically optimized to minimize a classification loss function (e.g., cross-entropy). This objective does not always align with the operational goal of fraud detection, which is to maximize the cumulative financial savings of correctly blocking fraud while minimizing customer friction.

2.3. Reinforcement Learning for Anomaly Detection

Reinforcement Learning (RL) reframes the classification problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). Unlike supervised learning, which provides a static label for every input, RL involves an agent that interacts with an environment (the stream of transactions) and receives a reward signal based on its actions [12]. This paradigm allows for the direct optimization of non-differentiable business metrics through reward shaping.

Recent literature has begun to explore RL for anomaly detection. The RLAD framework proposed by Wu and Ortiz [9] demonstrated that a Deep Q-Network (DQN) could effectively learn to identify anomalies in time-series data by treating the classification decision as an action in an MDP. By decoupling the learning process from static loss minimization, RL agents can learn aggressive policies that prioritize rare events if the reward structure incentivizes it. This study builds upon these theoretical foundations to answer the research questions posed in Section 1.

2.4. Mapping Financial Fraud to RL

To bridge the gap between financial anomaly detection and reinforcement learning theory, we formalize the fraud detection problem not as a static classification task, but as a sequential interaction between a monitor (the agent) and a client profile (the environment). This conceptual model is based on three theoretical links:

- 1.

- Sequentiality of fraud: Unlike static anomalies, financial fraud often evolves through a trajectory of events (e.g., an initial phase of low-risk, apparently legitimate transactions followed by a sudden escalation into illicit activity). The RL framework captures this via the state representation (), which is not a single point but a history window, allowing the agent to detect patterns based on temporal context rather than instantaneous feature values.

- 2.

- Action-consequence feedback: In a banking context, every decision has an immediate operational consequence. Blocking a legitimate user (False Positive) incurs a “customer friction” cost, while allowing a fraud (False Negative) incurs a direct financial liability. This aligns naturally with the RL reward signal (), which effectively translates the asymmetric cost matrix of the business directly into the optimization objective.

- 3.

- Adaptive decision boundary: Traditional classifiers optimize a fixed decision boundary based on a training set distribution. In contrast, an RL agent optimizes a policy to maximize long-term rewards. This theoretically allows the system to adapt its sensitivity based on the state of the client (e.g., becoming more aggressive if the recent sequence shows rising entropy), rather than applying a global threshold to all users.

By framing the problem through this conceptual lens, we justify the selection of a DQN with LSTM encoders as the appropriate methodological vehicle to answer the research questions posed in Section 1.

3. Materials and Methods

Our study utilizes two distinct datasets to evaluate the RLFD framework, selected to assess performance in both a complex, real-world banking scenario and a standardized public environment.

3.1. Proprietary Transaction Dataset

The primary dataset employed in this study is a proprietary collection of financial transactions provided by Intesa Sanpaolo (ISP), comprising 90,314 bank transfers from anonymized users. The dataset is highly imbalanced, containing 3285 fraudulent transactions, which represent approximately 3.6% of the total. To ensure privacy and regulatory compliance, all data were encrypted and anonymized: categorical and textual variables were hashed using the Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit (SHA-256) [13] prior to being transformed into numerical representations for machine learning models.

A feature engineering process was carried out to construct a rich and structured set of variables for each transaction, organized into the following categories:

- Temporal: Hour, day, day of the week, and a weekend indicator.

- Spatial: Latitude and longitude of the transaction origin, along with a client-specific distance from spatial median feature. Specifically, for each client, the median latitude and longitude across all transactions are computed, and the Euclidean distance of each transaction from this spatial median is calculated, providing a measure of geographic deviation.

- Financial: Transaction amount, currency code, divisibility flags (e.g., by 2, 5, or 10), and decimal patterns (e.g., 0.00, 0.50).

- Contextual and technical: Bank Identifier Code (BIC), bank codes, client type, mobile carrier, and decomposed/encrypted IP address octets. Semantic information from the transaction description field is captured using a 10-dimensional Word2Vec embedding.

- Security and authentication: Flags indicating secure app usage, fingerprint authentication, instant payment, and digital signatures.

The raw data undergo a preprocessing procedure to prepare it for the RLFD agent:

- 1.

- Chronological sorting: Transactions are first grouped by client ID and then sorted chronologically by timestamp to preserve temporal dependencies.

- 2.

- Categorical feature selection: To manage the high dimensionality of categorical variables, a two-stage selection process is applied. First, features are ranked by their Mutual Information (MI) score with respect to the fraud label, and the top-N features are retained. Then, for each selected feature, only the top-M most frequent values are preserved, with all others aggregated into a single “Other” category.

- 3.

- Encoding and scaling: The selected categorical features are one-hot encoded, while all numerical variables are normalized to the range using Min–Max scaling.

Finally, we note that synthetic oversampling techniques (e.g., SMOTE) were explicitly excluded from the pipeline. In sequential domains, generating synthetic transaction vectors can disrupt the temporal coherence of client histories, introducing look-ahead bias and invalidating the Markov property required for the RL agent.

3.2. UCI Credit Card Default Benchmark

To assess the generalizability of our framework, we also employ the public “Default of Credit Card Clients” dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [14]. This dataset, which contains records for 30,000 unique clients, is a standard benchmark for classification tasks. It has been used in numerous studies, including a recent comparative analysis of various machine learning models for fraud detection by Seera et al. [10]. The dataset includes demographic data and a six-month history of bill amounts, payment amounts, and repayment statuses. The target label indicates whether a client defaulted on their payment in the subsequent month, with a default rate of approximately 0.22.

While the dataset contains a six-month history, it is not primarily known for strong, long-term temporal correlations and is treated in the literature as a static, tabular problem. This makes it a particularly challenging benchmark for our sequential model. By testing our framework here, we evaluate its performance in a scenario where it is not inherently favored over tabular-optimized methods like GBT, which can process all features simultaneously. This serves as a test of our model’s ability to generalize its feature-extraction and decision-making capabilities to different problem structures.

Since this dataset is in a wide format (one row per client), a specific preprocessing step is required to adapt it for our sequential model. We transform the data into a long format, creating a sequence of six time-steps for each client. Each time-step contains the client’s static demographic features combined with their monthly payment/billing variables for that specific month. The final client label (default or not) is propagated to all six time-steps for that client. The resulting features are then one-hot encoded where appropriate and scaled.

3.3. Windowing

For both datasets, the processed time-series data for each client are transformed into overlapping sliding windows of a fixed length window_size (w). Each window serves as the state representation for the agent. For clients with fewer than w transactions, the sequences are left-padded with a distinct placeholder value (), and a binary mask is generated to differentiate real observations from padding. We will refer to w (window_size) throughout.

3.4. RLFD Framework as a Markov Decision Process (MDP)

We formulate the fraud detection task as an MDP [12] defined by the tuple :

- State (): a state at time t, denoted , is a window of w preprocessed transaction vectors and is represented as a matrix , where d is the number of features.

- hlAction (): the agent takes one of two discrete actions at each time: , where denotes classifying the transaction as normal and as fraudulent.

- Reward (): the reward is asymmetric to reflect the higher cost of missing a fraudulent transaction. Given the true label ,where . In configuration files these are denoted r1 and r2.

- Transition Kernel (): state transitions are deterministic within a client’s transaction history: the next state is the subsequent overlapping window from the same client’s sequence.

- Discount Factor (): a scalar balancing immediate and future rewards (configuration key: gamma).

3.5. Model Architecture and Training Strategy

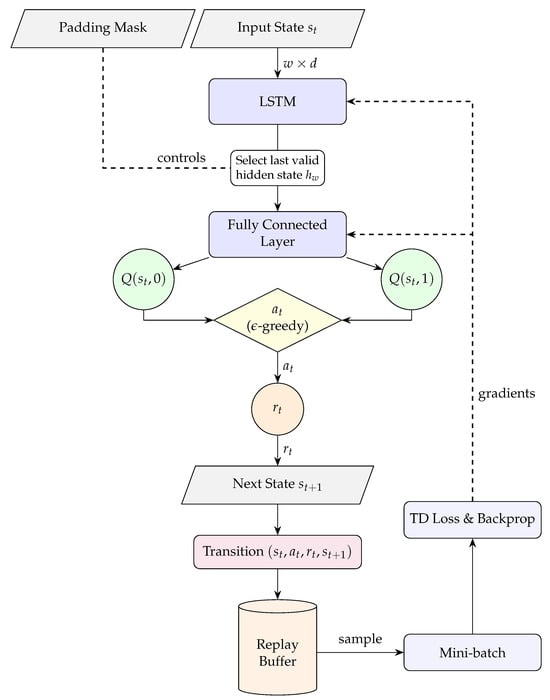

Our agent utilizes a Deep Q-Network (DQN) [15] with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [16] encoder to model sequential dependencies. While the fundamental network topology is adopted from the RLAD framework [9], we distinguish our approach by re-engineering the interaction loop for the financial domain. Unlike generic anomaly detection tasks where errors may be symmetric, we implement an asymmetric reward structure and a strictly chronological client-centric windowing mechanism. This ensures the agent is optimized not just for pattern recognition, but for the specific operational objective of maximizing fraud recall under imbalance. The architecture is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Expanded agent architecture and training loop. The network outputs Q-values for normal and fraud; an -greedy selector chooses , leading through the environment to and . The transition is appended to the replay buffer (max size: replay_buffer_size). Mini-batches from the buffer drive temporal-difference (TD) loss (model updated every target_update_freq episodes) and backpropagation (dashed arrows). Here, w is the window length (window_size) and d is the feature count.

The input state is passed to the LSTM, which outputs a sequence of hidden states. We extract the last valid hidden state (using the padding mask) as a compressed representation and set . A linear layer then computes the action–value vector:

where represents the network weights. Following best practices [9], the LSTM’s forget-gate bias is initialized to .

Training is stabilized using two relevant DQN mechanisms [15]:

- Experience Replay: All transitions are stored in a replay buffer. The agent learns by sampling mini-batches from this buffer. The maximum replay buffer size (replay_buffer_size) is treated as a hyperparameter and has been tuned to balance sample diversity and memory efficiency.

- Target Network: A separate, fixed target network is used to generate the temporal-difference (TD) target, reducing instability by decoupling the target from the online network. The TD target isThe online network parameters are updated by minimizing the mean squared error. The target network parameters are updated during training with a fixed frequency (target_update_freq), which is also tuned as a hyperparameter.

Training is structured into episodes, where each episode corresponds to the full transaction history of a single client. An -greedy strategy is used for action selection.

3.6. Evaluation Strategy

Our evaluation strategy differs between the two datasets to adhere to best practices for each.

- Proprietary Dataset: We employ a two-stage evaluation. First, for initial development and hyperparameter tuning, we use a single, stratified holdout split: training (0.64), validation (0.16), and testing (0.20). During this stage, we save the “Best Validation Model” that maximizes fraud recall while maintaining normal-class recall above a high threshold (e.g., 0.90). This specific selection criterion was driven by the bank’s operational requirements, which mandated a minimum fraud recall of ≈ due to the high imbalance and the pattern of fraudulent behavior. Consequently, our tuning process prioritized pushing the recall for the fraud class to reach this limit, rather than solely optimizing global metrics like the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC AUC) or the Area Under the Precision–Recall Curve (PR AUC) which can yield low detection rates in highly imbalanced scenarios. Second, for a more robust and unbiased performance assessment, we conduct a 10-fold stratified cross-validation. This allows for a direct comparison against gradient boosted trees (GBT) baselines, which were evaluated using the identical cross-validation scheme and data preprocessing.

- UCI Benchmark Dataset: For this standard benchmark, we employ a 10-fold stratified cross-validation as in Seera et al. [10]. In each fold, the data are split into 8 folds for training, 1 for validation, and 1 for testing. A fresh model is trained for each of the 10 folds, and its best performance (based on its validation set) is evaluated on the test fold. The final reported metrics are aggregated from the out-of-fold predictions from all 10 runs.

3.7. Performance Metrics

Evaluating the performance of fraud detection models requires a set of metrics that handle severe class imbalance and asymmetric misclassification costs [1]. Throughout, we define the positive class as (fraud for the proprietary dataset and default for the UCI dataset). The confusion-matrix entries TP, TN, FP, and FN are with respect to .

Accuracy: the overall proportion of correctly classified instances relative to all transactions:

While commonly reported, Accuracy can be misleading under extreme imbalance [17].

Precision and Recall: precision (Positive Predictive Value) measures the proportion of correctly identified positives among all predicted positives:

Recall (Sensitivity, True Positive Rate) measures the proportion of actual positives that were detected:

High recall reduces Type II error (missed positives), whereas high precision reduces Type I error (false alarms) [18].

F1-Score: the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall:

Threshold-Independent Metrics: to assess ranking performance across thresholds, we report the ROC AUC and the PR AUC, the latter being often more informative under imbalance [19].

4. Results

4.1. Proprietary Dataset Performance on Holdout Set

The model was first trained on our proprietary dataset using the holdout split methodology. The specific hyperparameters, detailed in Table 1, were selected through a grid search optimization process on the validation set. The rationale for the key parameter choices is as follows:

- Reward Ratio (): The positive reward for catching fraud (r1) is set four times higher than the reward for correct normal classification (r2). This asymmetry is necessary to counteract the severe class imbalance (3.6% fraud), ensuring the agent finds it mathematically advantageous to pursue rare fraud events rather than converging to a trivial “always normal” policy.

- Exploration (epsilon_min = ): Unlike standard RL tasks where often decays to 0.01, we maintain a higher minimum exploration rate. This prevents the Q-network from overfitting to the majority class and encourages the agent to continuously test the decision boundary around rare events.

- Feature Thresholds (): These parameters were treated as hyperparameters within the optimization loop. Preliminary sensitivity analysis on the validation set indicated this configuration offered the optimal trade-off; increasing dimensions beyond this point introduced state sparsity that destabilized the DQN convergence without improving recall, while lower values discarded predictive signal.

- replay_buffer (80): A constrained buffer size was chosen to ensure the agent learns from relatively fresh, on-policy experiences, which is beneficial given the non-stationary nature of user transaction patterns.

- window_size (18): Empirically determined to balance the capture of sufficient temporal context against the inclusion of irrelevant historical noise.

Table 1.

Hyperparameter configuration and training parameters for the RLFD Agent (proprietary dataset).

Table 1.

Hyperparameter configuration and training parameters for the RLFD Agent (proprietary dataset).

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Preprocessing & Model Architecture | |

| window_size | 18 |

| hidden_size (LSTM) | 64 |

| Top-N Features N | 10 |

| Top-M Categories M | 10 |

| Training | |

| learning_rate | 0.001 |

| gamma | 0.95 |

| batch_size | 8 |

| replay_buffer_size | 80 |

| inner_epochs | 200 |

| target_update_freq | 40 |

| epsilon_min | 0.22 |

| r1 (Positive-class reward) | 4.0 |

| r2 (Negative-class reward) | 1.0 |

The performance in Table 2 indicates that the Best Validation Model is superior for fraud detection, achieving a fraud recall of 0.67. This performance reflects a deliberate trade-off driven by our validation strategy: the model identifies most frauds while maintaining a recall of 0.90 for normal transactions. It is important to note that the achieved recall of 0.67 satisfies the explicit requirement to push fraud recall above 65%, thus sacrificing some accuracy. This demonstrates that the RLFD agent can be effectively tuned to meet strict operational thresholds that prioritize detecting rare events, a capability often compromised when optimizing solely for standard aggregated metrics.

Table 2.

Performance on the proprietary dataset test set (holdout split). All metrics are proportions in . The best recall for the fraud class, obtained with the Best Validation Model, is in bold.

4.2. Cross-Validation Benchmark on Proprietary Dataset

To provide a more robust evaluation, we conducted a 10-fold cross-validation on the proprietary dataset, comparing our RLFD framework against GBT baselines. The results, averaged across the 10 folds, are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

10-fold cross-validation performance on the proprietary dataset. Values are mean ± std. dev. across 10 folds.

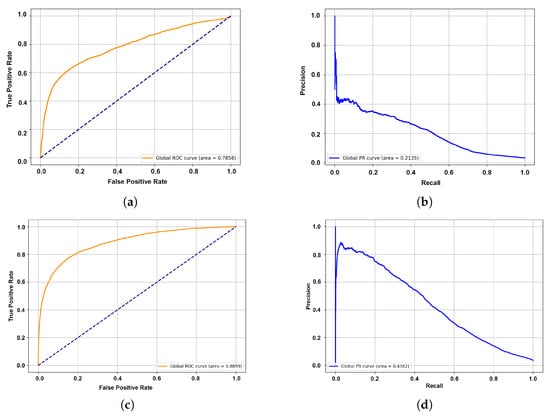

The standard GBT model demonstrates strong statistical capabilities, achieving the highest overall ROC AUC (0.886) and PR AUC (0.443), as evidenced in Figure 2. This indicates that the tree-based model is highly effective at ranking transactions and distinguishing classes when the decision threshold is optimized globally. However, at the default decision threshold of 0.5, the GBT yields a low recall for the fraud class (0.226 ± 0.042), heavily favoring precision. Applying class weighting (GBT Weighted) improves the recall to 0.450, but still falls short of the RLFD agent in pure sensitivity. Infact, the RLFD framework, while achieving lower aggregate ranking metrics (ROC AUC 0.773, PR AUC 0.222), successfully learns an aggressive policy from the asymmetric reward signal. It achieves the highest fraud recall of 0.549 ± 0.062, directly meeting the operational requirement to prioritize the detection of rare events. To assess statistical significance, we rely on the standard deviation across the 10 folds as a proxy for confidence intervals. The RLFD fraud recall presents a distribution that is strictly superior to the standard GBT with no overlap in the intervals, confirming the significance of the sensitivity improvement.

Figure 2.

Aggregated ROC and Precision–Recall curves from the 10-fold cross-validation on the proprietary dataset, comparing the RLFD (DQN-based) framework and the GBT model. (a) RLFD Global ROC Curve. (b) RLFD Global Precision–Recall Curve. (c) GBT Global ROC Curve. (d) GBT Global Precision–Recall Curve. In the ROC plots (a,c), the blue dashed diagonal line represents the performance of a random classifier (AUC = 0.5).

The discrepancy between the high recall and lower AUC suggests that while the RLFD agent is less precise globally, it is particularly effective at flagging a specific subset of suspicious activities that align with the high-reward criteria.

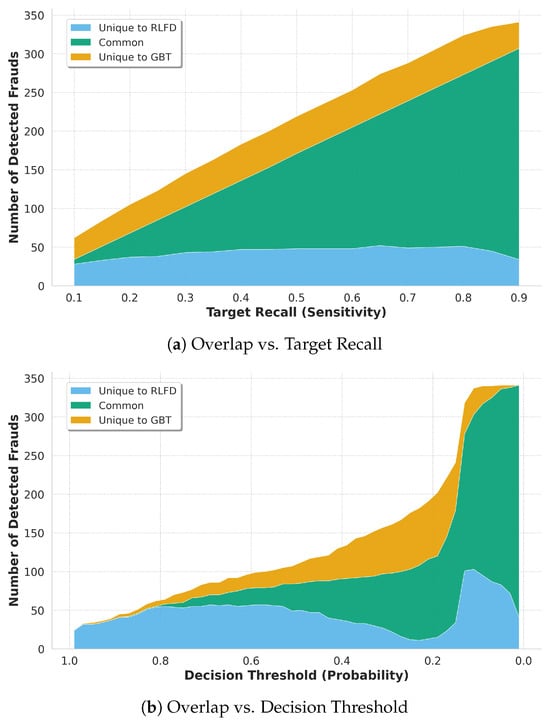

4.3. Orthogonality and Complementary Detection

To better understand the operational value of the RLFD framework beyond aggregate metrics, we performed a dynamic orthogonality analysis. Instead of relying on a single overlap snapshot, we examined the intersection of detected frauds across different operating points on the holdout set.

Figure 3a displays the overlap composition as a function of the target fraud recall. While the symmetry between the unique sets is mathematically enforced by equating the recall of both models, the magnitude of these unique sets is relevant. If the models relied on similar decision boundaries, the “Common” area would dominate and the unique bands would be negligible. Instead, the persistent width of the “Unique to RLFD” band demonstrates that for any given sensitivity level, the RLFD agent captures a substantial volume of fraud that the GBT inherently misses, proving that the agent is not merely a redundant classifier but a source of orthogonal information.

Figure 3.

Dynamic orthogonality analysis between the RLFD agent and the GBT baseline. (a) Evolution of fraud overlap as a function of target fraud recall (sensitivity). (b) Evolution of fraud overlap as a function of the decision threshold (probability cut-off), ordered from strict (1.0) to loose (0.0). In both views, the blue area highlights the unique contribution of the RLFD agent, which persists across all operating points.

Figure 3b visualizes the overlap as a function of the decision threshold, moving from strict (high probability) to loose (low probability) classifiers. At very strict thresholds (e.g., >), the RLFD agent is notably more effective, capturing the vast majority of detected frauds. Even as the threshold is lowered and the GBT becomes more effective, the RLFD agent continues to contribute a distinct set of unique detections, comprising approximately 30% of the total union of detected frauds at threshold 0.4, and over 40% unique cases at threshold 0.5, that are never captured by the tree-based model. This persistent orthogonality confirms that the two models rely on fundamentally different decision boundaries: the GBT exploits feature interactions in tabular space, while the RL agent leverages temporal transitions to catch sequential anomalies.

4.4. UCI Benchmark Performance

To address our third research question regarding generalizability, we evaluated the framework on the UCI Credit Card Default dataset. This environment differs fundamentally from the proprietary bank dataset: the sequences are short (only 6 time-steps), the granularity is coarse (monthly aggregates vs. timestamps), and the class imbalance is moderate (22% vs. 3.6%).

Consequently, the agent’s hyperparameters required logical adaptation, as detailed in Table 4. The window_size was reduced to 4 to accommodate the limited six-month history available per client. Furthermore, the positive reward scalar () was lowered from 4.0 to 3.0; because the default class is less rare than banking fraud, the agent requires less aggressive incentivization to learn the minority class distribution.

Table 4.

Key hyperparameters for the UCI benchmark experiment.

The comparative results are presented in Table 5. Our RLFD framework achieves an Accuracy of 0.802 and a ROC AUC of 0.696. When compared to the suite of static classifiers evaluated by Seera et al. [10], the RL agent performs competitively with standard distance-based methods (e.g., k-NN) but trails behind ensemble tree methods like GBT (Accuracy 0.821, ROC AUC 0.778).

Table 5.

Comparison of RLFD performance on the UCI benchmark against results reported by Seera et al. [10]. Bold values indicate the performance of the proposed RLFD framework. Source results from Feng et al. [20] and Jadhav et al. [21]. Accuracy is reported as a proportion in . Acronyms: k-NN, k-nearest neighbours; NB, Naïve Bayes; SVM, support vector machine; BagDT, bagged decision trees; BagNN, bagged neural networks; BagSVM, bagged support vector machines.

This result provides a relevant boundary condition for our research questions. It suggests that the RLFD framework’s advantage is heavily dependent on the presence of high-frequency sequential signals. In the UCI dataset, where temporal resolution is low (monthly snapshots) and feature interactions are largely static, the GBT leverage their superior ability to partition tabular space. However, the fact that the RL agent maintains robust performance (within 2% Accuracy of the state-of-the-art) despite being architecturally optimized for sequential tasks confirms its flexibility across different financial domains.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of reinforcement learning for financial fraud detection, specifically addressing the capability of sequential agents to identify rare events in highly imbalanced domains. Interpreting our findings through the lens of the primary research questions reveals a distinct trade-off between statistical ranking power and operational coverage.

Regarding the first research question on detection efficacy, the empirical results on the proprietary dataset affirm that the RLFD agent can achieve superior recall for rare events compared to static baselines. While the standard GBT model prioritized precision, resulting in a low fraud recall of 0.226, the RLFD agent leveraged the asymmetric reward signal () to achieve a fraud recall of 0.549. This demonstrates that in operational contexts where the financial liability of a false negative vastly outweighs the friction cost of a false positive, the RL framework offers a more tunable and effective optimization objective than standard cross-entropy loss minimization. Regarding computational efficiency, the RLFD framework requires significantly higher training resources compared to GBT (approximately wall-clock time in our experiments) due to the episodic nature of the interaction loop. However, inference latency remains comparable, as the trained Q-network processes sequence windows in constant time.

The most relevant finding, however, addresses the operational orthogonality of the models. The dynamic orthogonality analysis presented in Figure 3 provides strong evidence that the RLFD framework detects a distinct subset of fraudulent activities. The persistence of the “Unique to RLFD” detection band across the entire threshold spectrum indicates that the agent is not merely acting as a noisier classifier, but is sensitive to fundamentally different patterns that are invisible to the tree-based model. Notably, at high-confidence thresholds, the RL agent contributed over 30% of the unique detections. This confirms its value as a complementary safety net that captures temporal correlations missed by the independence assumption of static classifiers.

To define the boundary conditions of this approach, we examined the framework’s performance on the UCI benchmark, which lacks high-frequency temporal data. The results show that while RLFD is competitive (Accuracy 0.802), it does not outperform the GBT (Accuracy 0.821) in purely tabular environments. This establishes a clear limitation: the RLFD framework provides maximum value in domains with rich sequential signals (e.g., timestamped banking logs) and offers diminishing returns in static classification tasks where feature interactions dominate.

These findings have both theoretical and practical implications. Theoretically, the study reinforces the distinction between classification error minimization and operational utility maximization. By framing fraud detection as a Markov Decision Process, the decision boundary is allowed to evolve based on the sequential state of the client, contrasting with the fixed hyperplane approaches of supervised learning. Methodologically, our analysis highlights the danger of relying solely on global metrics like ROC AUC or Accuracy in highly imbalanced settings, a choice made on the UCI benchmark to align with the comparative analysis by Seera et al. [10]. As shown in Table 3, a model can achieve superior ROC AUC (0.886 vs. 0.773) while failing the primary business objective of detecting fraud (Recall 0.22 vs. 0.55). Consequently, future comparisons should prioritize threshold-dependent metrics and dynamic overlap analyses. From a practical standpoint, the findings speak against a “winner-takes-all” model selection. The optimal strategy for financial institutions is possibly an hybrid parallel deployment: using GBTs as a primary high-precision filter, while deploying RL agents in parallel to intercept the significant fraction of complex, sequential attacks that bypass static rules.

6. Conclusions

We adapted and evaluated a Reinforcement Learning for Fraud Detection (RLFD) framework alongside a Gradient Boosted Trees (GBTs) baseline on both a proprietary, real-world financial dataset and a public credit default benchmark. The investigation reveals that statistical superiority (as measured by Area Under the Curve, AUC) does not necessarily imply operational completeness. While the GBT baseline provides a robust primary filter with high precision, our dynamic orthogonality analysis proves it remains blind to specific anomalies across the entire decision spectrum. The RLFD framework, employing an episodic training loop, asymmetric reward shaping, and LSTM-based state encoding, successfully captures these elusive patterns. On the proprietary dataset, this approach consistently identifies a unique set of fraudulent transactions that the GBT misses; conversely, on the static public benchmark, the sequential advantage diminishes. We therefore caution that the magnitude of the complementary effect observed here (e.g., the ≈30% unique detections) is likely dataset-dependent and contingent on the prevalence of high-frequency sequential patterns in the target financial stream.

We conclude that the optimal deployment strategy for financial fraud detection is not a monolithic choice between static or sequential models, but rather a hybrid parallel architecture. In such a system, the RLFD agent serves as a specialized “safety net” for complex, sequence-dependent fraud scenarios that evade traditional tree-based classifiers, thereby significantly enhancing the total fraud coverage of the banking system. Future evolution of this framework will focus on the integration of Explainable AI (XAI) methods to bridge the gap between the high sensitivity of Deep RL agents and the regulatory requirement for interpretability in the financial sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.; Methodology, A.P.; Software, A.P.; Validation, A.P.; Formal analysis, A.P.; Investigation, A.P.; Writing—original draft, A.P.; Writing—review & editing, A.P., B.C., P.L. and R.C.; Visualization, A.P. and P.L.; Supervision, P.L. and R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR)—Missione 4 “Istruzione e Ricerca”—Componente 2 “Dalla Ricerca all’Impresa”—Investimento 1.4 “Campioni nazionali di R&S”, Project “National Centre for HPC, Big Data and Quantum Computing”—CN1 (Spoke 2) “Simulazioni, calcolo e analisi dei dati ad alte prestazioni”, CUP: B83C22002830001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The proprietary dataset used in this study consists of bank transactions protected by legal and contractual restrictions; raw data cannot be shared. The public benchmark dataset is available at the UCI Machine Learning Repository at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/350/default+of+credit+card+clients (accessed on 21 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank Intesa Sanpaolo for providing the anonymized dataset for this research. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Intesa Sanpaolo, its affiliates, or its employees.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Riccardo Crupi was employed by the company Intesa Sanpaolo S.p.A. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APP | Authorized Push Payment |

| ATO | Account Takeover |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| BagDT | Bagged Decision Trees |

| BagNN | Bagged Neural Networks |

| BagSVM | Bagged Support Vector Machines |

| BIC | Bank Identifier Code |

| DQN | Deep Q-Network |

| GBT | Gradient Boosted Trees |

| ISP | Intesa Sanpaolo |

| k-NN | k-Nearest Neighbours |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MI | Mutual Information |

| NB | Naïve Bayes |

| PR | Precision–Recall |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RLAD | Reinforcement Learning for Anomaly Detection |

| RLFD | Reinforcement Learning for Fraud Detection |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SHA-256 | Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TD | Temporal Difference |

| UCI | University of California Irvine (Repository) |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Compagnino, A.A.; Maruccia, Y.; Cavuoti, S.; Riccio, G.; Tutone, A.; Crupi, R.; Pagliaro, A. An introduction to machine learning methods for fraud detection. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Aros, L.; Bustamante Molano, L.X.; Gutierrez-Portela, F.; Moreno Hernandez, J.J.; Rodríguez Barrero, M.S. Financial fraud detection through the application of machine learning techniques: A literature review. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Abd Razak, S.; Othman, S.H.; Eisa, T.A.E.; Al-Dhaqm, A.; Nasser, M.; Elhassan, T.; Saif, A. Financial fraud detection based on machine learning: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashedi, K.G.; Magalingam, P. Financial fraud detection applying data mining techniques: A comprehensive review from 2009 to 2019. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Bhattacharya, M. Intelligent financial fraud detection: A comprehensive review. Comput. Secur. 2016, 57, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.; Maarof, M.A.; Zainal, A. Fraud detection system: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2016, 68, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngai, E.W.T.; Hu, Y.; Wong, Y.h.; Chen, Y.; Sun, X. The application of data mining techniques in financial fraud detection: A classification framework and an academic review of literature. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.J.; Hand, D.J. Statistical fraud detection: A review. Stat. Sci. 2002, 17, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Ortiz, J. RLAD: Time series anomaly detection through reinforcement learning and active learning. In Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGKDD Workshop on Mining and Learning from Time Series (MiLeTS’21), Virtual Event, Singapore, 14–18 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Seera, M.; Lim, C.P.; Kumar, A.; Dhamotharan, L.; Tan, K.H. An intelligent payment card fraud detection system. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 334, 445–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurgovsky, J.; Granitzer, M.; Ziegler, K.; Calabretto, S.; Portier, P.E.; He-Guelton, L.; Caelen, O. Sequence classification for credit-card fraud detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 100, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Penard, W.; Van Werkhoven, T. On the secure hash algorithm family. In Cryptography in Context; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–18. Available online: https://blog.infocruncher.com/resources/ethereum-whitepaper-annotated/On%20the%20Secure%20Hash%20Algorithm%20family%20%282008%29.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Dua, D.; Graff, C. UCI Machine Learning Repository. 2019. Available online: http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Alpízar, A.; Jenkins, M.; Martínez, A.; Quesada-López, C. Use of data mining and machine learning techniques for fraud detection in financial statements: A systematic mapping study. RISTI—Iber. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. 2020, E28, 97–109. Available online: https://www.risti.xyz/issues/ristie28.pdf (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Bakumenko, A.; Elragal, A. Detecting anomalies in financial data using machine learning algorithms. Systems 2022, 10, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The precision–recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Xiao, Z.; Zhong, B.; Qiu, J.; Dong, Y. Dynamic ensemble classification for credit scoring using soft probability. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 65, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; He, H.; Jenkins, K. Information gain directed genetic algorithm wrapper feature selection for credit rating. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 69, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.