Abstract

The synergistic combination of the ruthenium-based tetranuclear dendrimer photosensitizer with the highly efficient water oxidation catalyst Ru(bda)(pic)2 enables effective water oxidation under low-energy light irradiation in phosphate buffer 20 mM/acetonitrile 3% (pH 7). This study demonstrates that the integrated system can produce a significant amount of oxygen using visible light at wavelengths greater than 650 nm (up to 160 nmol), achieving quite good turnover number (3.5 × 10−3), high quantum yields (0.23) and enhanced stability. These results highlight the potential of this approach to efficiently drive solar water splitting for fuel production, even with low-energy illumination, thereby advancing the development of sustainable photochemical systems for solar energy conversion.

1. Introduction

Nature harnesses solar energy to sustain life, primarily through photosynthetic organisms such as plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Over the course of approximately two billion years, these biological systems have evolved to efficiently convert abundant raw mate-rials—carbon dioxide and water—into oxygen and carbohydrates, high-energy molecules that serve as natural fuels.

Inspired by this process, scientific research aims to develop artificial systems capable of converting light into usable fuels, a strategy known as artificial photosynthesis. This technology could, at least in principle, provide a definitive solution to the global energy crisis.

In natural photosynthesis, light absorption by photosynthetic pigments initiates a sequence of energy transfer and charge separation events [1,2,3]. These reactions lead to the oxidation of water, producing molecular oxygen (Equation (1)), while the generated reducing equivalents are employed for the reduction of CO2 to carbohydrates (Equation (2)):

2 H2O → O2 + 4 H+ + 4 e− E0′ = −0.81 V

n CO2 + 2 ne− + 2 H+ → (CH2O)n E0′ = −0.43 V

In artificial systems, the reaction pathway can mimic the natural process for water oxidation, but the reducing equivalents may instead be directed toward the production of high-energy fuels, such as hydrogen (Equation (3)), or reduced carbon-based molecules (Equations (4)–(8)):

2 H2O + 2 e− → H2 + 2 OH− E0′ = −0.42 V

CO2 + 2 H+ + 2 e− → HCOOH E0′ = −0.61 V

CO2 + 2 H+ + 2 e− → CO + H2O E0′ = −0.53 V

CO2 + 4 H+ + 4 e− → HCHO + H2O E0′ = −0.48 V

CO2 + 6 H+ + 6 e− → CH3OH + H2O E0′ = −0.38 V

CO2 + 8 H+ + 8 e− → CH4 + H2O E0′ = −0.24 V

In recent years, scientific efforts have focused on the synthesis and characterization of new species—particularly molecular ones—capable of accumulating electron holes (oxidative side) or electrons (reductive side) [4,5]. These compounds are investigated for their ability to produce oxygen and hydrogen from water, or to reduce CO2 into valuable products such as carbon monoxide or formic acid [6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

The oxidation of water using visible light represents a major challenge for researchers aiming to develop artificial photosynthetic systems capable of producing high-energy species from water and sunlight.

Significant efforts have been devoted to the synthesis and investigation of new molecular species that can serve as water oxidation catalysts (WOCs). Ruthenium-based molecular catalysts are among the earliest and most extensively studied, dating back to 1982, when Meyer and co-workers reported the so-called “blue dimer”, cis,cis-[RuII(bpy)2(H2O)]2(μ-O), with a catalytic turnover number (TON) of 13 and a turnover frequency (TOF) of 0.0042 s−1 using Ce4+ (Cerium Ammonium Nitrate, CAN) as the oxidant.

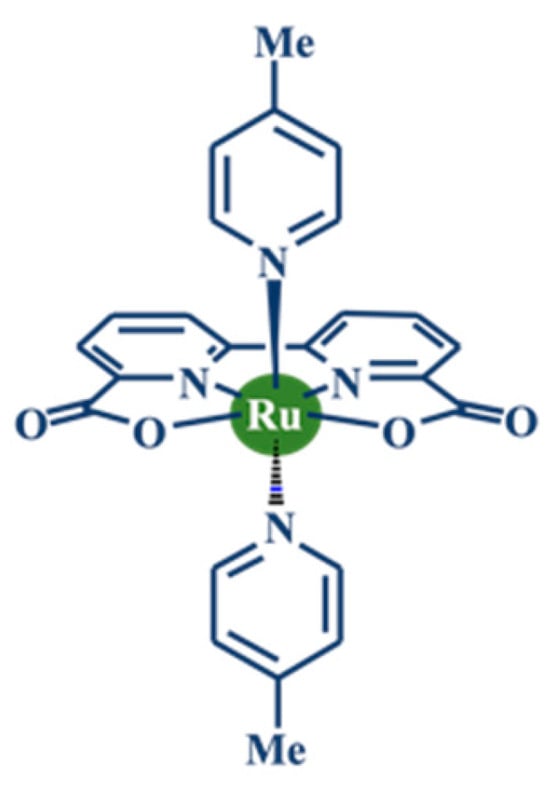

After decades of research, a breakthrough in molecular WOC efficiency was achieved in 2009 with the development of the Ru(bda)(pic)2 catalyst (bda = 2,2′-bipyridine-6,6′-dicarboxylate; pic = 4-picoline, Figure 1). This complex displayed a TON of 2000 and a TOF of 41 s−1 with CAN as the oxidant. Notably, the TOF value of Ru(bda)(pic)2 approaches that of natural photosynthetic systems. Together with its relatively low overpotential (180 mV), these properties establish Ru(bda)(pic)2 as one of the most active and efficient molecular WOCs reported to date.

Figure 1.

Structural formula of Ru(bda)(pic)2.

Although several efficient catalysts for water oxidation, driven by chemical oxidants or electrochemical methods, have been identified, achieving light-driven water oxidation with high quantum yield (Φ) remains a considerable challenge for molecular systems. Inorganic species such as ruthenium [13,14] and vanadium polyoxometalates have demonstrated remarkable photocatalytic activity, with quantum yields up to 0.3, while a tetra cobalt cubane catalyst reached a quantum yield of 0.4 for oxygen production in sacrificial systems. In all these cases, Ru(II) polypyridine complexes served as photosensitizers (PS) [15,16].

Mononuclear ruthenium WOCs generally exhibit high catalytic activity under chemical oxidation using one-electron oxidants such as CAN, achieving high TOF and TON values, but tend to perform poorly under photocatalytic conditions [17]. The [Ru(bpy)3]2+ complex (bpy = 2,2′-bipyridine), in combination with sodium persulfate as a sacrificial electron acceptor, has become a standard photosensitizer system for mechanistic studies of light-driven water oxidation by homogeneous WOCs [18]. [Ru(bpy)3]2+-type complexes possess strong visible-light absorption, efficiently generate long-lived triplet metal-to-ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) states, and display a sufficiently high oxidation potential in their oxidized form (PS+) to oxidize WOCs. Moreover, the irreversible cleavage of persulfate upon one-electron reduction to sulfate ion and sulfate radical limits competitive charge recombination, thereby improving photocatalytic efficiency [19].

The performance of a photo-driven water oxidation system depends strongly on both the light intensity and the ability of the photosensitizer to absorb visible light [20]. Thus, spectral overlap between the PS absorption profile and the solar spectrum is a key parameter, and a variety of metal complexes have been investigated for this purpose [21].

Photocatalytic experiments combining [Ru(bda)(pic)2] with [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as the photosensitizer and sodium persulfate as the sacrificial electron acceptor achieved a quantum yield for O2 production of 0.34 (based on 100% monochromatic light absorption), which is among the highest values reported in the literature.

However, [Ru(bpy)3]2+ presents two major drawbacks for practical applications in water oxidation: (i) it exhibits minimal absorption at wavelengths above 500 nm; (ii) its oxidized form is relatively unstable, thereby limiting its turnover number. Furthermore, its oxidation potential (1.26 V vs. SCE) is not sufficiently positive to provide a strong driving force for hole transfer to the WOC. One potential strategy to overcome these limitations is to covalently link the photosensitizer and catalyst through appropriate bridging ligands [22,23,24,25], or to modulate the redox behavior of the photosensitizer.

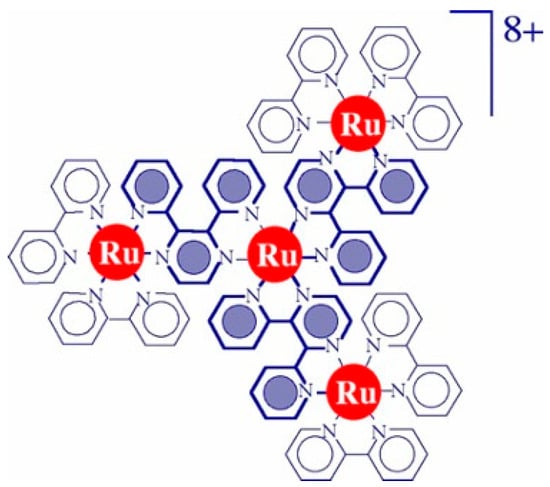

A tetranuclear Ru(II) dendrimer, [Ru{(μ-dpp)Ru(bpy)2}3]8+ (Ru4dendrimer, Figure 2), has been shown to surpass the properties of [Ru(bpy)3]2+, including an extended absorption spectrum up to 700 nm and an oxidation potential 290 mV more positive [26,27]. This dendrimer has been successfully employed as a photosensitizer in combination with efficient water oxidation catalysts. It was paired with malonate-stabilized IrO2 nanoparticles, achieving a quantum yield for oxygen evolution of 0.05 [28]. In 2010, a unique “4 × 4” ruthenium assembly combining Ru4dendrimer with Ru4POM as the catalyst reached a quantum yield of 0.3, the highest reported for photoinduced water oxidation at the time, using 550 nm irradiation. Additionally, the dendrimer photosensitizer demonstrated greater stability than the mononuclear [Ru(bpy)3]2+ under these conditions.

Figure 2.

Structural formula of [Ru{(μ-dpp)Ru(bpy)2}3]8+ (Ru4dendrimer).

The Ru4dendrimer is the only sensitizer known to utilize low-energy light for the photocatalytic oxidation of water to produce molecular oxygen in the presence of suitable catalysts. This species acts as a light-harvesting antenna, and in previous studies, it has been employed solely in combination with the Ru4POM catalyst for oxygen evolution. It is particularly interesting to investigate whether this sensitizer, which absorbs low-energy visible light more efficiently than the commonly used Ru(bpy)3, can also function effectively with different catalysts. Exploring its compatibility and performance with various catalytic systems could provide valuable insights into its versatility and potential for broader application in solar-driven water oxidation processes.

These developments indicate a clear path in the design of next-generation photosensitizers: systems combining wide visible-light absorption with improved redox potency and stability. The Ru4 dendrimer therefore offers a strong molecular framework for coupling with a range of catalytic components, hence helping the idea that effective photocatalysis can, in theory, be attained by means of a greater part of the solar spectrum than is available to conventional Ru(II) polypyridine compounds.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Synthesis

Ru(bda)(pic)2 and Ru4dendrimer were prepared following a modified version of reported procedures [29,30]. All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany) and used without further purification. Phosphate buffer solutions were prepared using Romil SPS-grade water. The detailed synthetic procedures are described in Supplementary Information.

2.2. Methods

The detailed procedures for spectrophotometric, spectrofluorimetric, and electrochemical measurements are provided in the Supplementary Information. Additionally, the procedures related to photocatalytic oxygen evolution measurements are also described in the Supplementary Information.

3. Results and Discussion

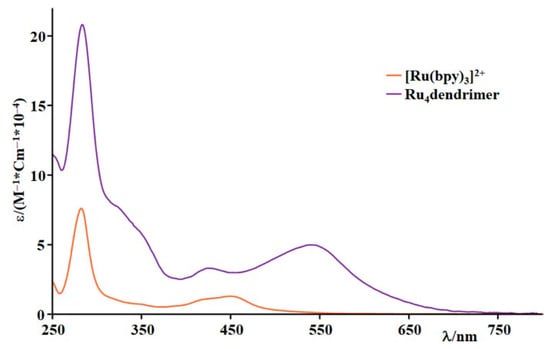

Figure 3 displays the absorption spectra of Ru4 dendrimer and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in phosphate buffer. Both spectra cover the visible and ultraviolet portions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Observed bands correlate for both species to π–π* transitions in the UV range and metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transitions in the visible spectrum.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectra of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and Ru4dendrimer in phosphate buffer 20 mM, pH = 7.

The presence of a bridging ligand connecting two metal centers in the Ru4 dendrimer makes possible lower-energy transitions involving the LUMO localized on the 2,3-dipyridylpyrazine bridge, producing a red shift supported by luminescence. With an emission maximum (Figure S2) at 782 nm and a lifetime of 51 ns, the dendrimer exits a lower-energy 3MLCT state including the peripheral metal centers and the bridging ligand. All photophysical properties were reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of sensitizers in aqueous solution.

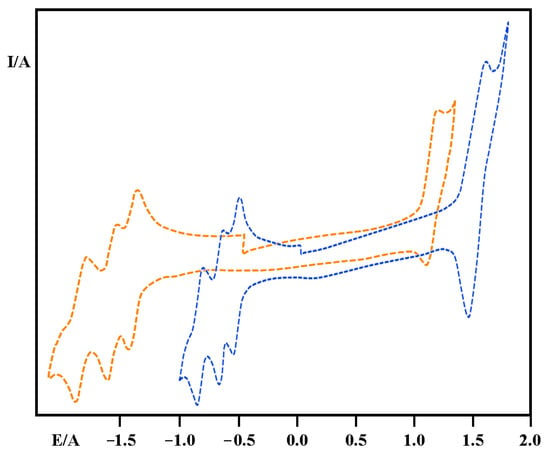

Furthermore, electrochemical characterization was performed. The well-known mononuclear complex [Ru(bpy)3]2+ undergoes a one-electron, reversible oxidation process at approximately +1.24 V vs. SCE, which is attributed to the oxidation of the metal center, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cyclic voltammogram of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (orange line) and Ru4dendrimer (blue line species in acetonitrile solution.

The dendrimer undergoes a reversible, tri-electronic oxidation at +1.50 V vs. SCE. This process involves the simultaneous and independent oxidation of the peripheral metal centers, which are more electron-rich than the central metal, due to the presence of bipyridine ligands within their coordination sphere. No oxidation of the central metal in the tetranuclear species is observed below 2 V vs. SCE, likely because the presence of three already oxidized centers (whose oxidation occurs at relatively positive potentials) shifts the oxidation potential of the central metal beyond this range, as shown in Figure 4

In Ru(II) polypyridinic complexes, reduction processes are localized on the ligands, resulting in a highly rich reduction redox pattern of the synthesized species. The reduction potential of each ligand depends on its electronic properties and, to a lesser extent, on the nature of the metal and the other ligands coordinated to it. As in the experimental conditions used, electronic communication between two metal centers is detectable only if the two metals are coordinated to the same bridging ligand; ligand–ligand interactions are significant only when ligands are coordinated to the same metal center.

In the cyclic voltammetry of the mononuclear species, three single-electron, reversible reduction processes are observed at −1.35 V, −1.55 V, and −1.74 V vs. SCE, respectively, attributable to the sequential reduction of the three bipyridine ligands.

The reduction pattern of polynuclear complexes is even more complex, as each ligand can undergo multiple reductions; specifically, each terminal ligand (bpy) can be reduced twice, while each bridging ligand can be reduced up to four times [31,32,33].

The tetranuclear dendrimer exhibits, upon reduction, three reversible one-electron processes at −0.55 V, −0.65 V, and −0.77 V vs. SCE. The potentials at which these processes occur allow us to assign them to reductions localized on the bridging ligands.

Furthermore, the voltammogram of the tetranuclear species displays three additional nearly reversible reduction processes at −1.20 V, −1.33 V, and −1.48 V vs. SCE, which are attributed to the second reductions of the bridging ligands. Electrochemical data were summarized in Table 2.

From a thermodynamic standpoint, and assuming that all electron transfer events occur within the Marcus normal region, the sequential hole-scavenging reactions of the oxidized sensitizer by Ru(bda)(pic)2 are anticipated to be faster for the Ru4dendrimer complex than for [Ru(bpy)3]2+. In the Marcus normal regime, a greater driving force for hole transfer generally leads to higher reaction rates, suggesting that the more oxidizing Ru4dendrimer should promote more efficient charge separation. Although this expectation requires confirmation by ultrafast spectroscopic measurements, such rapid hole scavenging would be beneficial in enhancing the overall photochemical efficiency while simultaneously mitigating photoinduced degradation of the sensitizer [34,35].

Table 2.

Oxidation potentials in acetonitrile solution at room temperature. Potential is reported vs. SCE [35].

Table 2.

Oxidation potentials in acetonitrile solution at room temperature. Potential is reported vs. SCE [35].

| Eox1/V | Eox2/V | Eox3/V | Ered1/V | Ered2/V | Ered3/V | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Ru(bpy)3]2+ | +1.24 | - | - | −1.35 | −1.55 | −1.74 |

| Ru4dendrimer | +1.5 | - | - | −0.55 | −0.65 | −0.77 |

| Ru(bda)(pic)2 a | +0.47 | +0.71 | +1.05 | - | - | - |

a oxidation potential in mixes solvent acetonitrile/water (1/1) vs. Ag/AgCl [23].

Calculating the free energy change (ΔG) is essential for understanding the spontaneity and efficiency of photoinduced electron transfer (PET) reactions. For oxidative quenching, where the donor is excited, ΔG is given by:

where is the half-wave potential for the acceptor’s reduction, is the half-wave potential for the donor’s oxidation, is the energy of the donor’s excited state, and represents the coulombic work term, which is often approximated as zero in dilute solutions. Conversely, for reductive quenching, where the acceptor is excited, the equation becomes:

where is the energy of the acceptor’s excited state. The term is considered numerically negligible.

Using the provided data, where for the [Ru(bpy)3]2+ ΔG = 0.27 and for the Ru4dendrimer ΔG = −0.1 eV, these calculations offer insights into the thermodynamic feasibility of the electron transfer processes in different molecular systems.

Given Ru4dendrimer’s well-known photocatalytic capabilities as a photosensitizer used with molecular catalysts like Ru4POM (TON = 350, TOF = 0.08 s−1 Though with an overall activity lower than that of [Ru(bda)(pic)2], we worked to improve the interaction between light-harvesting and catalytic elements to increase water oxidation efficiency [31,32,33].

Employing [Ru(bda)(pic)2] as the catalyst and Ru4dendrimer as the photosensitizer, with sodium persulfate acting as a sacrificial electron acceptor, photoinduced oxygen evolution was seen in this context. Amazingly, oxygen production under low-energy irradiation (λ = 650 nm), a region where the photosensitizer keeps considerable absorption (Figure 3 Table 1), emphasizing the degree of efficiency with which the Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] assembly stimulates visible-light-driven water oxidation.

To evaluate the efficiency of the Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] system, we compared:

- (i)

- the performance of [Ru(bda)(pic)2] combined with different photosensitizers ([Ru(bpy)3]2+ vs. Ru4dendrimer), and

- (ii)

- the water oxidation activity of systems containing Ru4dendrimer with either [Ru(bda)(pic)2] or Ru4POM as WOCs.

All photocatalytic experiments were carried out in phosphate buffer (20 mM) containing 3% acetonitrile at pH 7, with sodium persulfate as sacrificial agent, and irradiated at 650 nm. The concentration of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ was set to four times that of Ru4dendrimer to normalize for the number of chromophores in the photosensitizers.

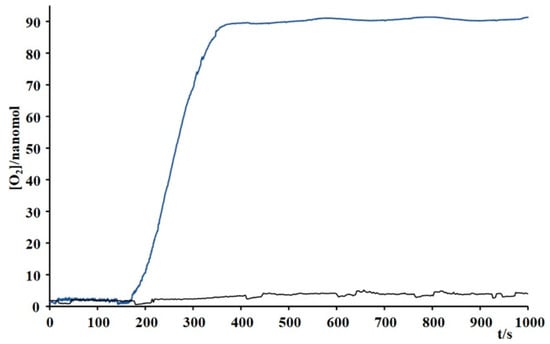

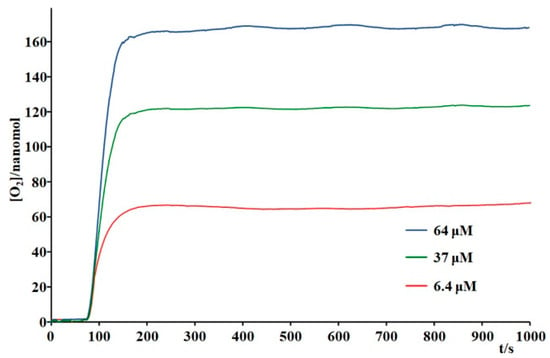

Figure 5 shows that under these conditions, the Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] system produced approximately 40 times more molecular oxygen than the [Ru(bpy)3]2+/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] system. While oxygen evolution was minimal with [Ru(bpy)3]2+, the Ru4dendrimer-based system generated about 90 nmol of O2. Further-more, oxygen production experiments performed at varying catalyst concentrations (Figure 6) demonstrated that even at low [Ru(bda)(pic)2], the system can generate ~60 nmol of O2 from water under low-energy light. In order to verify that the system works only in the configuration Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2]/Na2S2O8, the experiment with Ru(bda)(pic)2/Na2S2O8 and Ru4dendrimer/Na2S2O8 were performed (Figure S3).

Figure 5.

Oxygen evolution experiments in phosphate buffer 20 mM/acetonitrile 3% (pH 7) by using Ru4dendrimer (Blue line, 3.75 × 10−4 M) and Ru(bpy)32+ (black line, 1.5 × 10−3 M) in combination with Ru(bda)(pic)2 (6.4 × 10−5 M) and Na2S2O8 (37 mM). For irradiation a source at 650 nm was used.

Figure 6.

Oxygen evolution experiments in phosphate buffer 20 mM/acetonitrile 3% (pH 7) by using Ru4dendrimer (3.75 × 10−4 M) in combination with Ru(bda)(pic)2 at different concentrations (reported in the inset) and Na2S2O8 (37 mM). Irradiation at λ > 650 nm.

The water redox process requires the transfer of four electrons; in a photoinduced system where each photon generates an electron–hole pair, the theoretical quantum yield for molecular oxygen formation is 0.25. In our system, however, Na2S2O8, after oxidizing the photosensitizer, forms the SO4− radical, which can further oxidize either the catalyst or an additional photosensitizer molecule. As a result, a single photon generates two electron–hole pairs, increasing the theoretical quantum yield to 0.5. An estimate of the efficiency of this photoactivated process is provided by the quantum yield: considering the absorbed photons at the irradiation wavelength (using a 650 nm LED source), the experimental quantum yield is 0.23, indicating that approximately 50% of the absorbed photons are effectively used by the system for molecular oxygen production (Table 3).

Table 3.

Efficiency data for different sensitizer/catalyst system.

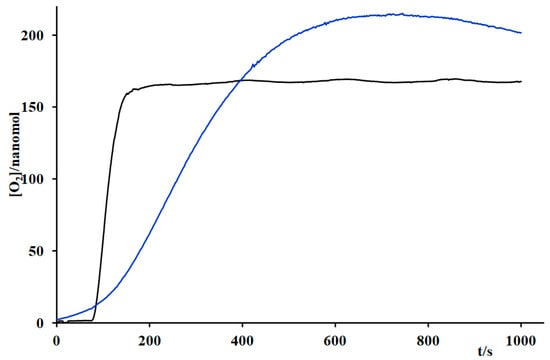

Kinetic experiments comparing Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] with Ru4dendrimer/Ru4POM under identical conditions showed similar rates of oxygen production (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Oxygen evolution by using Ru4dendrimer (3.75 × 10−4 M) and different catalysts: Ru4POM (Blue line) and Ru(bda)(pic)2 (black line) (6.4 × 10−5 M) in phosphate buff-er/acetonitrile 3%, pH 7. Irradiation at λ > 650 nm.

Although the advantages of using the Ru4dendrimer over [Ru(bpy)3]2+ are clear—owing to its broader absorption spectrum and higher oxidation potential—the experimental data suggest that substituting Ru4POM with [Ru(bda)(pic)2] does not lead to a significant enhancement in photocatalytic performance under the tested conditions. However, interpreting the similarity in activity between the systems Ru4dendrimer/Ru4POM and Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] requires caution, as their underlying mechanistic pathways may differ substantially.

In the case of Ru4POM, it has been demonstrated [32] that the sequence of photoinduced events is “anti-biomimetic”: initially, a reductive photoinduced electron transfer occurs within an ion-paired photosensitizer/catalyst complex, followed by electron transfer from the reduced photosensitizer to the sacrificial agent. This ion pairing, stabilized by electrostatic interactions, facilitates rapid intra-complex charge transfer, thus enhancing overall efficiency.

Conversely, the neutral [Ru(bda)(pic)2] catalyst lacks the high negative charge density or structured sites required for ion-pair formation. Consequently, it cannot readily participate in such assemblies. Instead, the electron transfer process is primarily governed by diffusional encounters in solution. After photoexcitation and oxidative quenching, the reduced Ru species (Ru+) must diffuse through the solvent to encounter and transfer an electron to the catalyst. The efficiency of this pathway critically depends on parameters such as diffusion coefficients, reactant concentrations, and the electronic coupling between the donor and acceptor. The absence of electrostatic stabilization results in generally slower electron transfer rates, which are also more sensitive to solution conditions.

While macroscopic measurements, such as oxygen evolution rates, might suggest similar catalytic activity, the underlying kinetic signatures differ markedly. Ion-pair–mediated transfer typically exhibits faster rates with lower activation barriers due to electrostatic stabilization, whereas diffusion-limited processes are inherently constrained by mass transport. Furthermore, the dynamics of charge-separated states can vary in ion-pair systems, close proximity facilitates rapid charge separation and minimizes recombination, leading to higher quantum yields; in neutral, unpaired systems, longer-lived charge-separated states are necessary to sustain catalytic turnover but risk increased recombination losses unless specific molecular arrangements—such as covalent linkages—are employed.

Understanding these mechanistic differences informs future strategies for system design. For neutral catalysts like [Ru(bda)(pic)2], creating molecular architectures that promote direct electronic coupling—for example, through covalent linking or proximity-enhancing ligands—could significantly improve charge transfer rates [36]. Additionally, immobilizing both components on structured supports or within nanostructured matrices can facilitate direct communication and more efficient electron transfer pathways [37]. Modifying the solvent environment—by adjusting viscosity, adding appropriate additives, or engineering the local dielectric—can also enhance diffusion and electron transfer kinetics [38].

Transforming the electron transfer from a diffusion-limited regime to a kinetically controlled one through these approaches can lead to substantial improvements in overall photocatalytic efficiency. This underscores the importance of an integrated design philosophy that combines molecular engineering with system-level architecture to overcome fundamental kinetic barriers and maximize solar-to-fuel conversion efficiencies.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the combination of Ru4dendrimer as a photosensitizer and [Ru(bda)(pic)2] as a molecular water oxidation catalyst exhibits high efficiency in photo-induced oxygen production, even under low-energy light irradiation (λ = 650 nm). The system achieved a quantum yield (Φ) of 0.23, indicating that significant proportions of absorbed photons are effectively converted into chemical energy.

When compared to the conventional [Ru(bpy)3]2+/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] pairing, the Ru4dendrimer/[Ru(bda)(pic)2] system produced ~40 times more O2 under identical experimental conditions. This marked improvement is attributed primarily to the broader absorption range and higher oxidation potential of Ru4dendrimer, which enhance light-harvesting efficiency and the driving force behind oxidative processes.

By coupling Ru4dendrimer with either [Ru(bda)(pic)2] or Ru4POM, slightly differences photocatalytic in performance were observed.

However, mechanistic differences between the two catalytic systems must be considered. In the Ru4POM system, the photoinduced process is “anti-biomimetic”, involving reductive electron transfer within an ion-paired photosensitizer–catalyst assembly, whereas [Ru(bda)(pic)2] operates via the more conventional sequence of photosensitizer oxidation by the sacrificial agent, followed by hole transfer to the catalyst.

Although this study represents an initial step, it provides compelling evidence that the Ru4 dendrimer is an efficient light-harvesting device capable of operating under conditions beyond the reach of conventional Ru(II) polypyridine photosensitizers. This approach underscores the importance of designing artificial photosynthetic systems that can achieve higher solar-to-fuel conversion efficiencies by utilizing lower-energy photons while maintaining sufficient oxidative power.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010159/s1, Detailed synthesis, methods, oxygen evolving measurements, determination of photochemical quantum yield for oxygen evolution; Figure S1, Photoisomerization reaction of Aberchrome 540; Figure S2, Emission spectra of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ and Ru4dendrimer in water; Figure S3, Oxygen evolution experiments in phosphate buffer 20 mM/acetonitrile 3% (pH 7) by using Ru4dendrimer (3.75 × 10−4 M ) in combination with Ru(bda)(pic)2 (6.4 × 10−5M) and Na2S2O8 (37 mM) (Blue line); Ru(bda)(pic)2 (6.4 × 10−5M) in combination with Na2S2O8 (37 mM) (Red line) and Ru4dendrimer (3.75 × 10−4 M ) in combination with Na2S2O8 (37 mM) (green line).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.P. and G.L.G.; methodology, F.N.; investigation, A.M.C. and A.A., data curation, F.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.C.; writing—review and editing, F.P., F.N. and G.L.G.; supervision, F.N. and G.L.G.; funding acquisition, G.L.G., F.P. and F.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

G.L.G, F.N. and F.P acknowledge the University of Messina for FFABR grants. This work has been partially funded by European Union (NextGeneration EU), through the MUR-PNRR project SAMOTHRACE (ECS00000022) and MUR project PRIN 2022 PHOTOGEN (J53D23007470006).

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding authors are available to share the data files upon request, as there is currently no cloud space available for data sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- García-Iglesias, M.; Peuntinger, K.; Kahnt, A.; Krausmann, J.; Vázquez, P.; González-Rodríguez, D.; Guldi, D.M.; Torres, T. Supramolecular Assembly of Multicomponent Photoactive Systems via Cooperatively Coupled Equilibria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 19311–19318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasielewski, M.R. Self-Assembly Strategies for Integrating Light Harvesting and Charge Separation in Artificial Photosynthetic Systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1910–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipem, F.A.S.; Mishra, A.; Krishnamoorthy, G. The role of hydrogen bonding in excited state intramolecular charge transfer. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 8775–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersten, S.W.; Samuels, G.J.; Meyer, T.J. Catalytic oxidation of water by an oxo-bridged ruthenium dimer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 4029–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.D. Photo-induced Electron and energy transfer in non-covalently bonded supramolecular assemblies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, J.P.; Sauvage, J.P. Synthesis and Study of Mononuclear Ruthenium(II) Complexes of Sterically Hindering Diimine Chelates. Implications for the Catalytic Oxidation of Water to Molecular Oxygen. Inorg. Chem. 1986, 25, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Bozoglian, F.; Mandal, S.; Stewart, B.; Privalov, T.; Llobet, A.; Sun, L. A molecular ruthenium catalyst with water-oxidation activity comparable to that of photosystem II. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Fischer, A.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L. Isolated Seven-Coordinate Ru(IV) Dimer Complex with [HOHOH]− Bridging Ligand as an Intermediate for Catalytic Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10397–10399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, L.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Li, F.; Sun, L. Highly Efficient Bioinspired Molecular Ru Water Oxidation Catalysts with Negatively Charged Backbone Ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Duan, L.; Stewart, B.; Pu, M.; Liu, J.; Privalov, T.; Sun, L. Toward Controlling Water Oxidation Catalysis: Tunable Activity of Ruthenium Complexes with Axial Imidazole/DMSO Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18868–18880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Iacopettab, D.; Ceramella, J.; Caruso, A.; Muià, N.; Longo, P.; Rosace, G.; Galletta, M.; Ielo, I. N-Thiocarbazole-based gold nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization and anti-proliferative activity evaluation. OP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 459, 012023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M.; Sun, L. Visible light-driven water oxidation by a molecular ruthenium catalyst in homogeneous system. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Tong, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, L. Visible light-driven water oxidation—From molecular catalysts to photoelectrochemical cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3296–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, H.; Sakai, K. Photo-hydrogen-evolving molecular devices driving visible-light-induced water reduction into molecular hydrogen: Structure–activity relationship and reaction mechanism. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntoriero, F.; La Ganga, G.; Sartorel, A.; Carraro, M.; Scorrano, G.; Bonchio, M.; Campagna, S. Photo-induced water oxidation with tetra-nuclear ruthenium sensitizer and catalyst: A unique 4 × 4 ruthenium interplay triggering high efficiency with low-energy visible light. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4725–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, M.-P.; La Ganga, G.; Nardo, V.M.; Natali, M.; Puntoriero, F.; Scandola, F.; Campagna, S. The Use of a Vanadium Species As a Catalyst in Photoinduced Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8189–8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Li, Z.; Liang, X.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, S.-T. Synthesis of a 6-nm-Long Transition-Metal–Rare-Earth-Containing Polyoxometalate. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 12534–12537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.J.; Sheridan, M.V.; Sherman, B.D. Mechanisms of molecular water oxidation in solution and on oxide surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 6148–6169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Triana, C.A.; Wan, W.; Adiyeri Saseendran, D.P.; Zhao, Y.; Balaghi, S.E.; Heidari, S.; Patzke, G.R. Molecular and Heterogeneous Water Oxidation Catalysts: Recent Progress and Joint Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 2444–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska-Andralojc, A.; Polyansky, D.E. Mechanism of the Quenching of the Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) Emission by Persulfate: Implications for Photoinduced Oxidation Reactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 10311–10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielo, I.; Cancelliere, A.M.; Arrigo, A.; La Ganga, G. Metal-based chromophores for photochemical water oxidation. Photochemistry 2023, 51, 384–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Wang, C.; Sun, C.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.-L.; Su, Z.-M. Ultra Stable Multinuclear Metal Complexes as Homogeneous Catalysts for Visible-Light Driven Syngas Production from Pure and Diluted CO2. J. Catal. 2020, 385, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancelliere, A.M.; Arrigo, A.; Galletta, M.; Nastasi, F.; Campagna, S.; La Ganga, G. Photo-driven water oxidation performed by supramolecular photocatalysts made of Ru(II) photosensitizers and catalysts. J. Chem. Phys. 2024, 8, 084709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteve, F.; Porcar, R.; Bolte, M.; Altava, B.; Luis, S.V.; García-Verdugo, E. A Bioinspired Approach Toward Efficient Supramolecular Catalysts for CO2 Conversion. Chem. Catal. 2023, 3, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamkhass, B.; Mametsuka, H.; Koike, K.; Tanabe, T.; Furue, M.; Ishitani, O. Architecture of Supramolecular Metal Complexes for Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction: Ruthenium–Rhenium Bi- and Tetranuclear Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2005, 44, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puntoriero, F.; Serroni, S.; La Ganga, G.; Santoro, A.; Galletta, M.; Nastasi, F.; La Mazza, E.; Cancelliere, A.M.; Campagna, S. Photo- and Redox-Active Metal Dendrimers: A Journey from Molecular Design to Applications and Self-Aggregated Systems. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 2018, 3887–3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetto, A.; Puntoriero, F.; Notti, A.; Parisi, M.F.; Ielo, I.; Nastasi, F.; Bruno, G.; Campagna, S.; Lanza, S. Self-Assembly of Hexameric Macrocycles from PtII /Ferrocene Dimetallic Subunits—Synthesis, Characterization, Chemical Reactivity, and Oxidation Behavior. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 2015, 5730–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ganga, G.; Nastasi, F.; Campagna, S.; Puntoriero, F. Photoinduced water oxidation sensitized by a tetranuclear Ru (II) dendrimer. Dalton Trans. 2009, 2009, 9997–9999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Sun, L. Ru-bda: Unique Molecular Water-Oxidation Catalysts with Distortion Induced Open Site and Negatively Charged Ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 5565–5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagna, S.; Denti, G.; Serroni, S.; Juris, A.; Venturi, M.; Ricevuto, V.; Balzani, V. Dendrimers of Nanometer Size Based on Metal Complexes: Luminescent and Redox-Active Polynuclear Metal Complexes Containing up to Twenty-Two Metal Centers. Chem. Eur. J. 1995, 1, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartorel, A.; Mirò, P.; Salvadori, E.; Romain, S.; Carraro, M.; Scorrano, G.; Di Valentin, M.; Llobet, A.; Bo, C.; Bonchio, M. Water Oxidation at a Tetraruthenate Core Stabilized by Polyoxometalate Ligands: Experimental and Computational Evidence To Trace the Competent Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16051–16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natali, M.; Puntoriero, F.; Chiorboli, C.; La Ganga, G.; Sartorel, A.; Bonchio, M.; Campagna, S.; Scandola, F. Working the Other Way Around: Photocatalytic Water Oxidation Triggered by Reductive Quenching of the Photoexcited Chromophore. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceroni, P.; Credi, A.; Venturi, M. Electrochemistry of Functional Supramolecular Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani, V.; Juris, A.; Venturi, M.; Campagna, S.; Serroni, S. Luminescent and Redox-Active Polynuclear Transition Metal Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mohamed, H.H.; Dillert, R.; Bahnemam, D. Kinetics and mechanisms of charge transfer processes in photocatalytic systems: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2012, 13, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morselli, G.; Reber, C.; Wenger, O.S. Molecular Design Principles for Photoactive Transition Metal Complexes: A Guide for “Photo-Motivated” Chemists. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 11608–11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.-K.; Zhong, S.-L.; Pei, J.-Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, D.-L.; Liu, D.-F.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Dang, Z.-M. Recent Progress and Future Prospects on All-Organic Polymer Dielectrics for Energy Storage Capacitors. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 3820–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbato, T.; Volpato, G.A.; Sartorel, A.; Bonchio, M. A breath of sunshine: Oxygenic photosynthesis by functional molecular architectures. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 12402–12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.