Abstract

Pediatric craniofacial fractures represent a significant diagnostic challenge due to age-dependent anatomical variability, subtle fracture lines, and the limited availability of specialists during emergency care. Computed tomography (CT) remains the gold standard for fracture assessment; however, small or non-displaced fractures may be easily overlooked. Advances in artificial intelligence offer opportunities for automated support in injury detection. In this study, we developed a 2.5D deep learning model that uses multiplanar CT reconstructions (axial, coronal, sagittal) as a three-channel input to a ResNet-18 network with transfer learning. A total of 63 high-quality CT examinations were included and split into a training set (n = 44) and a validation set (n = 19). The preprocessing pipeline included isotropic resampling, bone-window normalization, and the generation of 384 × 384 images. Model performance was evaluated using , , sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1-score, and threshold optimization using Youden’s index. The proposed model achieved = 0.822 and = 0.855. At the optimal decision threshold (t = 0.54), sensitivity reached 0.556, specificity 1.000, and F1-score 0.714. Grad-CAM visualizations correctly highlighted fracture-related structures, which was confirmed in an independent clinical assessment. The results demonstrate the potential of the proposed model as a decision-support tool for pediatric craniofacial trauma, providing a foundation for future extensions toward radiomics and hybrid deep-radiomic pipelines.

1. Introduction

Craniofacial fractures in children represent a significant clinical problem, and their radiological presentation differs from that observed in adult patients [1,2]. Pediatric patients exhibit different mechanisms of injury, distinct biomechanical properties of tissues, and ongoing developmental processes, which make fracture lines more subtle and more difficult to identify in imaging studies [1,2]. Computed tomography (CT) remains the gold standard in post-traumatic craniofacial diagnostics due to its high spatial resolution and the ability to assess bony structures across multiple planes [3]. In emergency settings, with high staff workload and limited availability of specialized radiologists and maxillofacial surgeons, the risk of overlooking small fractures remains considerable [3].

In parallel, there has been a very rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) methods in medical image analysis. Literature reviews indicate that convolutional neural networks (CNNs) achieve high performance in classification and detection of pathological findings in CT, X-ray, and other imaging modalities [4,5,6]. In the domain of craniofacial trauma, review papers discussing the use of AI for fracture diagnosis highlight the potential of these methods to streamline clinical decision-making and reduce the number of diagnostic errors [4,5]. At the same time, it is noted that most existing studies concern adult populations, and models trained on such data may have limited applicability in pediatric cohorts [1,2,7,8].

An important challenge in designing AI tools for medicine is not only achieving high classification metrics, but also ensuring the interpretability of model decisions. In diagnostic imaging, there is a growing expectation that algorithms should be able to indicate the regions of the image that most strongly influenced the final classification outcome (explainable AI, XAI). In the context of craniofacial trauma, this is particularly important because the location of the fracture within specific anatomical structures (e.g., the orbital rim, zygomatic arch, nasal bones) directly affects subsequent therapeutic management.

The aim of this study is to develop and preliminarily evaluate a deep learning model that automatically classifies pediatric craniofacial CT examinations into two classes: fracture vs. no fracture. A 2.5D approach was used, in which multiplanar MPRs in three planes (axial, coronal, sagittal) are treated as a three-channel input to a ResNet-18 network trained using transfer learning. The model’s discriminatory performance was evaluated using , , and classical metrics (sensitivity, specificity, precision, F1-score). Additionally, to increase clinical transparency, Grad-CAM visualizations were employed to identify image regions that contributed most strongly to the model’s decisions.

In this publication, we focus exclusively on the CNN-based processing pipeline. Radiomic analysis and hybrid models combining radiomic features with deep features will constitute the next stage of the project and will be presented in a separate study. This study provides the following contributions to the field of automated medical image analysis for pediatric craniofacial trauma:

- The development of a computationally efficient 2.5D deep-learning pipeline based on multi-planar CT projections, optimized for small pediatric datasets;

- Demonstration of strong discrimination performance (AUC_ROC = 0.822, AUC_PR = 0.855) despite the limited cohort size typical for pediatric trauma studies;

- The integration of a lightweight ResNet-18 architecture that offers a favorable balance between accuracy and computational cost, enabling potential real-time clinical deployment;

- The first implementation in our clinical setting of interpretable Grad-CAM visualizations validated by maxillofacial surgeons, confirming anatomically meaningful activation patterns;

- Formulation of a scalable methodological framework for future extensions involving 3D CNNs, radiomics, and hybrid deep–radiomic models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Characteristics

This retrospective study includes anonymized craniofacial CT examinations of pediatric patients (age < 18 years) performed in emergency settings at a single clinical center. From the complete dataset, 63 examinations meeting the quality criteria (no significant motion artifacts and a complete craniofacial scan) were selected.

The data were divided as follows:

- Training set: 44 examinations (22 with fractures, 22 without fractures);

- Validation set: 19 examinations (9 with fractures, 10 without fractures).

Clinical information (e.g., fracture description, injury location) was used solely for labeling the examinations (class 1—fracture, class 0—no fracture) and for subsequent qualitative interpretation of the Grad-CAM maps. All data were fully anonymized during export from the PACS system.

It should be noted that the dataset represents a preliminary, single-center pilot cohort. The limited number of examinations reflects the practical challenges of acquiring pediatric craniofacial trauma CT data in our clinical setting, including the relatively low incidence of such injuries and strict anonymisation procedures required in Polish hospitals. A multi-stage data collection process is currently ongoing, and future studies will include an expanded multi-center dataset together with external validation.

As all examinations were acquired at a single pediatric maxillofacial trauma center using a uniform CT protocol, the present results should be interpreted as single-center performance, while this reduces within-site variability, it does not capture differences across scanners or institutions, and therefore does not yet allow assessment of model robustness in multi-center settings.

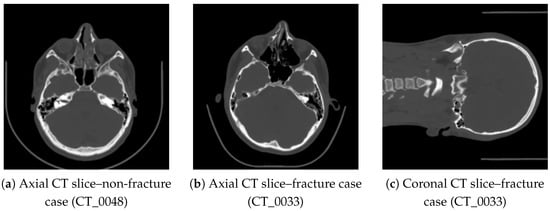

To illustrate the visual variability in the dataset, three representative CT slices are presented in Figure 1. Basic intensity-based features computed for these slices are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Representative CT slices included in the dataset: (a) healthy case, (b,c) fracture case showing disruptions of the orbital rim and anterior maxillary wall.

Table 1.

Example intensity-based features calculated for the representative CT slices shown in Figure 1.

2.2. Preprocessing and MPR Reconstruction

The raw DICOM data were converted to NIfTI format and then processed using a unified preprocessing pipeline:

- Intensity normalization to the bone window (typically around 1500/300 HU) and linear scaling of values to the range [0, 1];

- Isotropic resampling to a voxel resolution of 1.0 mm;

- Multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes;

- Extraction of a 384 × 384 pixel image for each plane, covering the entire craniofacial region;

- Saving all three projections as a three-channel 2.5D image.

For selected cases, additional median filtering was applied to reduce noise while preserving the visibility of thin bony structures.

2.3. 2.5D Model Input

The model input is defined as

where the three channels correspond to multiplanar CT reconstructions:

Here,

- —axial (transverse) reconstruction, providing a cross-sectional view commonly used for identifying discontinuities in the anterior–posterior direction,

- —coronal reconstruction, allowing assessment of vertical fracture patterns and orbital structures,

- —sagittal reconstruction, offering a longitudinal profile of the midface and mandible.

Using these three orthogonal projections as separate channels forms a 2.5D input representation. Although each reconstruction is two-dimensional, their combination preserves complementary anatomical information and approximates the spatial context of a full 3D CT volume, while remaining computationally efficient compared to 3D convolutional models.

For each examination, a binary label was assigned:

The label refers to the presence of any fracture within the craniofacial region, irrespective of its specific anatomical location.

2.4. Deep Learning Model Architecture

The core of the classifier is a ResNet-18 network implemented using the timm library, with pretrained ImageNet weights applied through transfer learning. The final fully connected layer was modified to produce a single output (logit), enabling the model to estimate the probability of a fracture:

where

- denotes the convolutional backbone of the network with parameters ; it maps the 2.5D input image X to a single scalar logit value;

- The output of is an unbounded real number representing the model’s internal score for the “fracture” class;

- is the sigmoid activation function,which converts the logit into a probability in the range ;

- The resulting value is interpreted as the predicted probability of the presence of a craniofacial fracture.

This formulation allows the model to produce a continuous probability score, which can later be transformed into a binary decision using a selected classification threshold. In this feasibility-stage study, the choice of the ResNet-18 architecture was motivated by the limited size of the pediatric CT dataset. Lightweight residual networks are widely recommended for small medical datasets because they offer a favorable balance between representational capacity and the risk of overfitting. Deeper models such as ResNet-50, DenseNet-121, or EfficientNet variants contain substantially more parameters and tend to overfit rapidly under similar conditions, whereas the residual connections in ResNet-18 ensure stable gradient propagation and efficient convergence. An additional practical advantage is the computational efficiency of ResNet-18, which enables fast inference suitable for clinical emergency workflows. Since the present work constitutes a pilot study, comparisons of multiple architectures would not yield statistically meaningful results. A broader evaluation including deeper CNNs, 3D models, and transformer-based architectures is planned once a larger multi-center pediatric dataset becomes available.

The ResNet-18 backbone was selected due to its favorable balance between model capacity and generalizability on small datasets. With approximately 11 million parameters, it is substantially less prone to overfitting than deeper CNNs or transformer-based architectures, which typically require hundreds or thousands of training volumes for stable convergence. Moreover, the 2.5D three-channel MPR input aligns naturally with ImageNet-based transfer learning, making ResNet-18 a computationally efficient and methodologically robust choice for the feasibility stage of this study.

2.5. Training Procedure

Model training was conducted in Python 3.10.19 using the PyTorch 2.4.1 framework. The following configuration was applied:

- Optimizer: AdamWwith a learning rate of and weight decay of . AdamW decouples weight decay from the gradient update, which improves stability and prevents overfitting, especially when training convolutional backbones on small datasets.

- Cosine annealing learning rate schedule. This schedule gradually reduces the learning rate following a cosine curve, enabling faster convergence at the beginning of training and more stable fine-tuning in later epochs.

- Batch size: . A small batch size helps regularize training and is suitable for 2.5D medical images with relatively large spatial dimensions.

- Number of epochs: 20, with the best model selected based on the lowest validation loss.

- Loss function: weighted binary cross-entropy, in which a higher weight is assigned to the fracture class. This compensates for the slight class imbalance and encourages the model to better detect fracture-positive cases.

To reduce the risk of overfitting given the limited dataset size, a set of standard data augmentations was applied:

- Random rotations up to ;

- Random brightness and contrast adjustments;

- Horizontal flips applied within the image plane.

These augmentations introduce natural variability while preserving the anatomical plausibility of the craniofacial structures.

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU (12 GB VRAM), an AMD Ryzen 7 5800X CPU, and 32 GB system memory. Owing to the relatively small dataset size, the full 20-epoch training cycle required only several minutes to complete. No explicit early stopping mechanism was used; instead, the final model was selected based on the checkpoint achieving the highest validation AUROC. The training process employed the AdamW optimizer together with a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler.

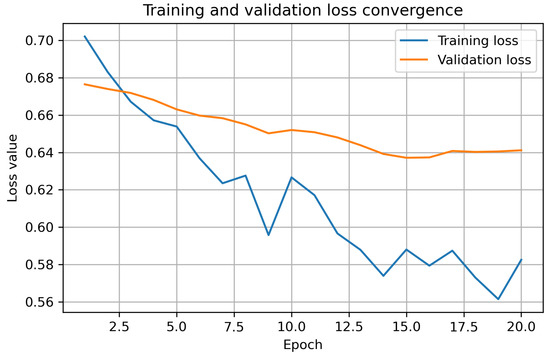

To monitor convergence and detect potential overfitting, both training and validation loss were recorded after each epoch. As shown in Figure 2, the training loss decreases smoothly throughout the 20 epochs, while the validation loss remains stable with no signs of divergence. This confirms that the model learns effectively and maintains generalization despite the limited size of the pediatric dataset.

Figure 2.

Training and validation loss convergence for the 2.5D ResNet-18 model. The curves demonstrate a stable decrease in training loss and a consistent validation loss profile, indicating that the model does not exhibit substantial overfitting despite the limited dataset size.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

The model’s performance was evaluated on the validation set using the following metrics:

- Area under the ROC curve (), which measures the ability of the classifier to distinguish between the fracture and non-fracture classes across all possible thresholds.

- Area under the precision–recall curve (,), particularly informative for datasets with moderate class imbalance, as it focuses on the trade-off between precision and sensitivity.

- Sensitivity (Sens) and specificity (Spec), quantifying the proportion of correctly detected fracture-positive and fracture-negative cases, respectively.

- Precision and F1-score, with the latter defined as the harmonic mean of precision and sensitivity.

- Confusion matrix values: true positives (TP), true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), and false negatives (FN), computed for a selected decision threshold.

To determine the optimal decision threshold, Youden’s index was used:

where t denotes the classification threshold. The value of t that maximized on the validation set was selected as the optimal threshold.

2.7. Grad-CAM Analysis

To enhance model interpretability, the Grad-CAM method was applied to generate heatmaps from the final convolutional layer of the ResNet-18 network. For selected examinations from the validation set, the following visualizations were produced:

- Grad-CAM heatmaps in the axial plane, rescaled to the input resolution (384 × 384 pixels);

- Overlay of the heatmaps (using the jet colormap) on the CT images with a transparency level of .

The evaluated cases included true positives (TP), false negatives (FN), and true negatives (TN). Each heatmap highlights regions contributing most strongly to the model’s prediction, with warmer colors indicating higher importance.

An important challenge in developing AI systems for medical imaging is not only achieving strong numerical performance but also ensuring that the underlying decision-making process remains interpretable for clinicians. In pediatric craniofacial trauma, where fracture lines may be subtle and anatomical variability is high, understanding why the model assigns a particular prediction is crucial for building clinical trust and for integrating AI safely into diagnostic workflows. For this reason, our methodological pipeline incorporates Grad-CAM as an explainability component. Grad-CAM generates spatial activation maps that highlight the regions of each CT slice that contributed most strongly to the network’s output, allowing clinicians to visually verify whether the model focuses on anatomically plausible structures such as cortical discontinuities or orbital asymmetries. This visualization also helps identify potential failure modes; for example, when the network highlights irrelevant regions or fails to attend to clinically meaningful areas. Including such interpretability tools reduces the “black-box” nature of deep learning models and supports transparency, clinical validation, and safe deployment in real-world settings.

An independent assessment of the Grad-CAM visualizations was performed by a maxillofacial surgeon, who compared the regions of highest activation with fracture locations documented in the clinical reports. This evaluation provided qualitative validation of the model’s interpretability and anatomical relevance.

2.8. Ethical Considerations

According to the official rules of the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia, retrospective analyses based exclusively on fully anonymized imaging data do not require ethical approval. All CT examinations used in this study were fully anonymized prior to analysis and contained no identifiable information.

3. Results

3.1. Data and Experiment Characteristics

The proposed 2.5D classification model was trained and evaluated on a retrospective dataset of pediatric craniofacial CT examinations. After initial preprocessing and random splitting using the same procedure as described in the Materials and Methods section, the training set consisted of examinations (22 with fractures and 22 without fractures), while the validation set consisted of examinations (9 with fractures and 10 without fractures).

A uniform preprocessing pipeline was applied to all examinations: isotropic resampling to a 1.0 mm voxel resolution and MPRs with an in-plane resolution of 384 × 384 pixels. The model is based on the ResNet-18 architecture in its 2.5D variant, and all results presented below refer to the independent validation set.

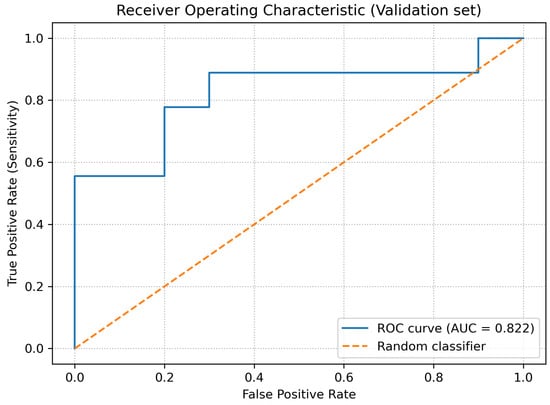

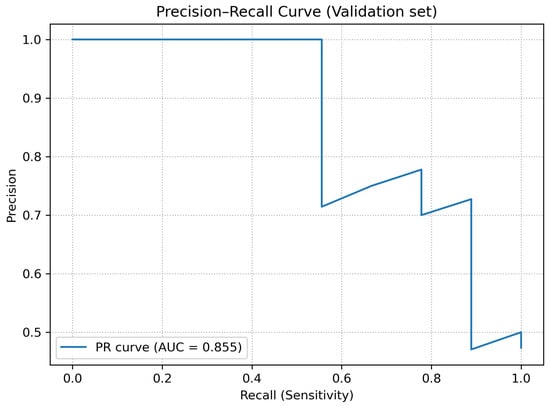

3.2. Global Discrimination Performance

The overall ability of the model to distinguish between examinations with and without fractures was assessed using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and the precision–recall (PR) curve. For the validation set, the following areas under the curves were obtained:

- ;

- .

As shown in Figure 3, the ROC curve demonstrates consistent discrimination between fracture and non-fracture cases across decision thresholds, with an AUCROC of 0.822. Complementarily, Figure 4 presents the precision–recall curve, highlighting stable precision levels over a wide range of recall values, which is particularly relevant given the moderate class imbalance in the validation dataset.

Figure 3.

ROC curve for the validation dataset.

Figure 4.

Precision–recall (PR) curve for the validation dataset.

The obtained values of and indicate that, despite the limited dataset size, the model is able to discriminate fracture-positive and fracture-negative examinations substantially better than a random classifier.

3.3. Decision Threshold Analysis

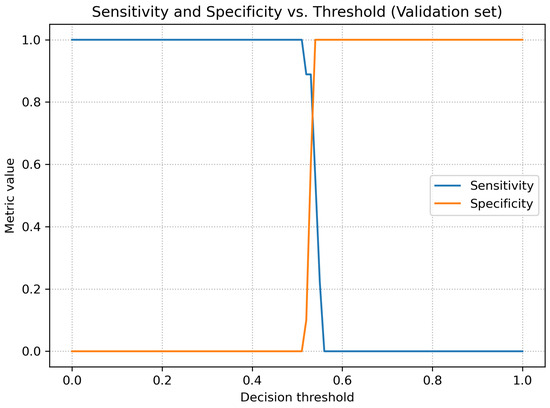

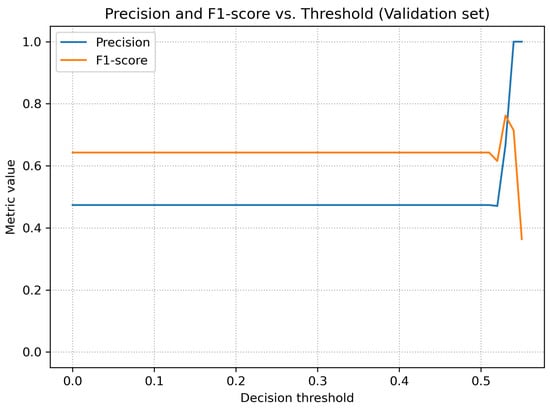

Since the network output is a continuous probability value of a fracture, the final binary decision depends on the selected threshold. Therefore, the variation of the main metrics (sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score) as a function of the decision threshold was analyzed.

Figure 5 shows the relationship between sensitivity and specificity as a function of the threshold. For low threshold values, the model achieved very high sensitivity at the cost of low specificity, whereas for higher thresholds the opposite trend was observed. Figure 6 presents the behavior of precision and F1-score as functions of the threshold.

Figure 5.

Sensitivity and specificity as functions of the decision threshold (validation dataset).

Figure 6.

Precision and F1-score as functions of the decision threshold (validation dataset).

A summary of the metrics for both thresholds, including full confusion matrix values (TP, TN, FP, FN), is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of validation metrics for the default threshold (0.50) and the optimal threshold according to Youden’s index (0.54).

A qualitative analysis of the results presented in Table 2 indicates that the model achieved stable classification performance despite the limited dataset size. The highest metric was precision, reflecting the absence of false-positive predictions at the optimal threshold and suggesting that the model is reliable in confirming the presence of fractures. Sensitivity remained moderate, which is expected in early-stage pilot studies involving heterogeneous pediatric trauma cases with subtle or non-displaced fractures. The AUC values demonstrate consistent discrimination capability across thresholds, forming a solid foundation for future improvements as the dataset expands and the architecture is further optimized.

3.4. Planned Extensions of the Results Section

In the next stages of the project, the results section is planned to be extended by:

- A qualitative analysis using Grad-CAM heatmaps illustrating the craniofacial regions that most influence the model’s decisions;

- Additional experiments combining the deep-learning approach with radiomic features computed from bone masks.

These components will be added after the completion of subsequent experiments.

3.5. Model Visualization Using Grad-CAM

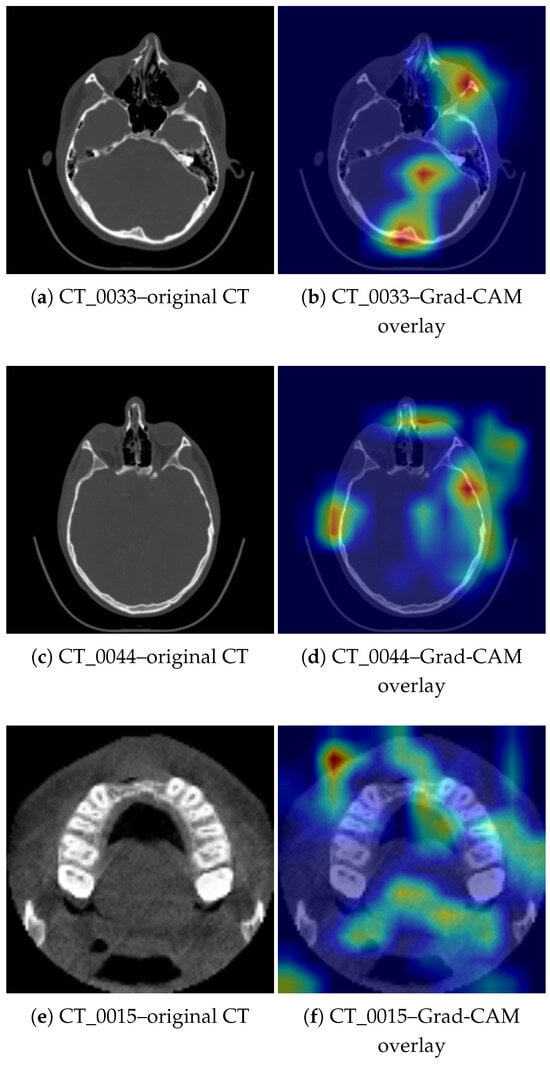

To better understand which regions of the computed tomography images contribute most strongly to the classifier’s decisions, the Grad-CAM method was applied to the trained ResNet-18 2.5D model. For each examination, heatmaps were generated from the final convolutional layer and overlaid onto the axial CT slices while preserving the same resolution as the model input (384 × 384 pixels).

Figure 7 presents three representative paired CT slices and corresponding Grad-CAM overlays from the validation set, evaluated at the decision threshold . Panels (a,b) show a true positive (TP) case (CT_0033), in which the model correctly identified a craniofacial fracture and the regions of highest activation overlap with clinically confirmed bone discontinuities. Panels (c,d) present another TP case (CT_0044), where the activation highlights anatomically consistent regions associated with post-traumatic changes. Panels (e,f) illustrate a false negative (FN) case (CT_0015), in which the model failed to exceed the decision threshold despite the presence of a fracture; here, the activation remains partially anatomically meaningful but is spatially weaker and extends toward adjacent, non-discriminative regions.

Figure 7.

Representative paired CT slices and corresponding Grad-CAM overlays from the validation set. Panels (a,b) show a TP case (CT_0033) and panels (c,d) show a TP case (CT_0044), where Grad-CAM highlights regions consistent with the fracture location. Panels (e,f) show an FN case (CT_0015), in which the activation includes both the alveolar ridge and unrelated soft-tissue regions, illustrating the interpretability limitations of Grad-CAM.

In the analyzed validation group (19 examinations, including 9 with fractures), the model achieved at the threshold the following values: , , sensitivity , specificity , positive predictive value , and F1-score . The Grad-CAM visualization confirms that in many correctly classified cases, the network focuses on bony structures associated with the fracture location, whereas in false negative cases the activation may shift toward unrelated regions of the skull or soft tissues.

3.5.1. Clinical Verification of Grad-CAM Maps

To assess the interpretability of the model, Grad-CAM visualizations were generated for selected cases from the validation dataset. A maxillofacial surgeon evaluated the heatmaps by comparing activated regions with the actual fracture locations visible on the CT images. The assessment confirmed a high level of agreement between the highlighted regions and the structures affected by trauma.

- Case CT_0033. A right-sided naso-orbital displacement was reported, including a fracture of the inferior orbital rim, the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus, and the nasal bones. The Grad-CAM visualization shows dominant activation on the right side, covering the areas corresponding to the described fractures. The highlighted regions align with the fracture lines and the location of traumatic changes.

- Case CT_0044. The clinical report indicated a fracture of the superior orbital rim on the left side, involving the zygomatico-orbital suture, as well as a non-displaced fracture of the nasal bones. Grad-CAM shows pronounced activation near the left superior orbital rim and adjacent frontal sinus structures, corresponding to the documented trauma. Additional smaller activations near the nasal bones are also consistent with the clinically identified fracture.

- Case CT_0015. The clinical description indicated a fracture of the anterior maxillary alveolar process with avulsion of teeth 12, 11, 21, and 22. The Grad-CAM map shows the strongest activation in the anterior portion of the maxilla, corresponding to the documented fracture site. Although this case was misclassified (false negative) at the selected threshold, the activation map remains anatomically meaningful.

These results demonstrate that the model not only correctly detects the presence of fractures but also localizes diagnostically relevant regions. This highlights the interpretable nature of the network and its potential clinical utility.

3.5.2. Interpretation of Paired CT and Grad-CAM Images

Figure 7 presents original CT slices alongside their corresponding Grad-CAM overlays. For CT_0033 (right-sided orbital–nasal fracture), the highlighted regions accurately follow the inferior orbital rim and the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus. For CT_0044 (left superior orbital rim fracture), Grad-CAM focuses on the fronto-zygomatic region, consistent with the documented injury. In CT_0015 (alveolar process fracture), the activation includes the anterior maxillary ridge but also extends toward unrelated soft-tissue structures, demonstrating known limitations of Grad-CAM saliency precision.

Grad-CAM produces continuous attention maps rather than anatomically sharp boundaries; thus, drawing explicit wireframe boxes for “fracture,” “missed area,” or “misdiagnosis” would imply a level of certainty not supported by the method. Instead, clinically validated textual interpretations are provided here.

4. Discussion

The results presented in this study confirm that the deep learning–based 2.5D approach can effectively support the diagnosis of craniofacial fractures in pediatric patients. The obtained metrics (, ) indicate a clearly better-than-random ability of the model to distinguish examinations with and without fractures, even despite the limited dataset size. This is consistent with previous findings showing that CNN models can achieve high performance in medical image analysis tasks when the architecture and transfer learning strategy are properly selected [4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14]. In the pediatric population, this issue is particularly important—anatomical variability and subtle fracture lines contribute to an increased risk of missed injuries, as emphasized in numerous clinical studies [1,2,7,9].

At the same time, the threshold analysis revealed that the default threshold of 0.50 led to overly optimistic classification (high sensitivity at the cost of specificity). Only after applying Youden’s index was it possible to identify a threshold providing a clinically acceptable balance between false-positive and false-negative results. The achieved specificity of 1.000 at aligns with clinical expectations, where avoiding unnecessary consultations or additional examinations is crucial. The moderate sensitivity may result both from the limited dataset size and from the nature of pediatric trauma cases, which often include small, non-displaced fractures that are difficult to detect even for experienced radiologists.

The moderate sensitivity observed at the optimal Youden threshold (t = 0.54) reflects a deliberate trade-off between true-positive and true-negative performance. At the conventional threshold t = 0.50, the model reaches a sensitivity of 1.00 but at the cost of zero specificity, demonstrating that the operating point strongly influences the balance of metrics. The chosen threshold was selected to provide clinically meaningful specificity in this small pilot cohort. Moreover, pediatric craniofacial fractures often present as subtle, non-displaced injuries that are difficult to detect even for experts, and the limited dataset size further constrains achievable sensitivity. Continued expansion of the dataset—especially with additional subtle fracture cases—is expected to improve sensitivity in the next phase of the project.

The model demonstrates moderate sensitivity at the selected operating point, which is partly a reflection of the small dataset size and the heterogeneous, often subtle nature of pediatric fractures. This limitation is expected to diminish as the dataset grows and the model is trained on a broader spectrum of injury patterns.

An essential component of the study was the assessment of model interpretability. Grad-CAM visualizations demonstrated high agreement with fracture locations described in clinical documentation, which is a key requirement for potential application of the tool in medical practice. According to recent research on explainable AI in radiology, the ability to highlight regions influencing the model’s decision increases user trust and supports clinical decision-making [15,16,17]. At the same time, false-negative cases showed that the activation of the model may shift toward structures unrelated to the injury, indicating areas that require further improvement.

The limitations of the study should also be addressed. The most significant is the small number of examinations, which restricts the generalizability of the results. This is a commonly reported problem in AI research involving pediatric populations [9,18], where data availability is substantially lower compared to adult datasets. Furthermore, the model uses only MPR projections, omitting the full spatial information contained in volumetric 3D data. Although the 2.5D approach represents a compromise between computational efficiency and representation complexity, future work may incorporate 3D architectures or hybrid models combining deep and radiomic features [13,14].

A further limitation is that the current model performs only binary classification (fracture vs. no fracture) and does not provide explicit localization or subclassification of fracture morphology, such as displaced, non-displaced, or comminuted fractures, while this demonstrates the feasibility of automated detection in pediatric craniofacial trauma, it does not yet meet the diagnostic requirements of clinical workflows, which often rely on precise anatomical localization and morphological characterization of injuries.

In future research, the analysis is planned to be expanded to include segmentation of bony structures and the development of hybrid models, which aligns with current trends reported in the literature [13,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. An additional direction may be external validation on datasets from multiple clinical centers, which would significantly increase the clinical value of the proposed approach.

Although ResNet-18 was intentionally chosen for its stability under limited-data conditions, future work will include systematic comparisons with deeper convolutional models (e.g., ResNet-50, EfficientNet, ConvNeXt) and transformer-based architectures once a larger, multi-center dataset becomes available. These architectures may provide improved capacity for modeling long-range dependencies in CT data, and their evaluation will form a key component of the next research stage.

An important direction for future work is to extend the model toward anatomically precise localization using radiologist-verified bounding boxes or segmentation masks, as well as toward multi-class classification distinguishing specific fracture types (e.g., displaced vs. non-displaced). Achieving this will require expanding the dataset and obtaining detailed region-level annotations, and these developments are planned for subsequent stages of the research program.

In the next phase of the project, we plan to expand the dataset by incorporating pediatric craniofacial CT examinations from at least two additional trauma centers. This will enable multi-center external validation of the proposed 2.5D model and provide a more rigorous assessment of its robustness across different scanners, patient populations, and imaging protocols. Where feasible, we also intend to explore federated learning schemes, which allow multi-institutional collaboration without compromising patient privacy.

Another important limitation is that the dataset originates from a single clinical center, and the model has not yet been evaluated on external data from other scanners or institutions. Consequently, the reported performance metrics represent single-center results and may not fully generalize to broader pediatric populations or different imaging environments.

It is important to emphasize that the present work should be interpreted as a proof-of-concept study representing the first stage of a multi-phase research programme. The limited dataset size is a direct consequence of the low incidence of pediatric craniofacial trauma cases and the strict anonymisation and legal procedures required in Polish hospitals. These factors substantially extend the time needed to acquire high-quality, ethically compliant CT examinations.

A multi-center data collection initiative is currently in progress, and the expanded dataset will form the basis for external validation as well as methodological extensions planned for subsequent publications. These include radiomics-based models, hybrid deep–radiomic approaches, and experiments incorporating 3D architectures. Together, these stages are intended to build a comprehensive and reproducible framework for automated analysis of pediatric craniofacial trauma.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a deep learning model based on the 2.5D approach was presented for the automated detection of craniofacial fractures in pediatric patients using CT examinations. The obtained results confirm that this method can effectively support trauma diagnosis, achieving high and values despite the limited dataset size. The Grad-CAM analysis demonstrated that the model is capable of identifying anatomical regions associated with the fracture location, which enhances its interpretability and clinical applicability.

The limitations of the study—primarily the small dataset size and the absence of full 3D analysis—indicate the need for further research. Future work will focus on extending the approach to include radiomic features, segmentation of bony structures, and multi-center validation, which may significantly increase the clinical usefulness of the proposed tool.

Author Contributions

B.I.: development and implementation of machine learning algorithms, data preparation and analysis, analysis of CT images. Ł.W.: data and results analysis, evaluation of machine learning algorithm performance, substantive supervision of the analytical process. N.S.-I.: medical analysis, verification of clinical correctness of the results, assessment of CT images. B.O.-W.: medical analysis, verification of the accuracy of descriptions and interpretations of results, assessment of CT images. Z.W.: results analysis, review and correction of descriptions and interpretations in the clinical and scientific context. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscrip.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it involved the retrospective use of fully anonymized imaging data, in accordance with the regulations of the Bioethics Committee of the Medical University of Silesia.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the use of fully anonymized retrospective imaging data.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to clinical data protection regulations, patient privacy, and institutional restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the maxillofacial surgery team for clinical evaluation of Grad-CAM visualizations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| area under the ROC curve | |

| area under the precision–recall curve | |

| CT | computed tomography |

| TK | computed tomography (Polish abbreviation) |

| MPR | multiplanar reconstruction |

| CNN | convolutional neural network |

| XAI | explainable artificial intelligence |

| TP | true positive |

| TN | true negative |

| FP | false positive |

| FN | false negative |

| 2.5D | intermediate approach between 2D and 3D (multiplanar projections) |

| HU | Hounsfield units |

| ROI | region of interest |

| ML | machine learning |

| AI | artificial intelligence |

References

- Alcalá-Galiano, A.; Arribas-García, I.J.; Martín-Pérez, M.A.; Romance, A.; Montalvo-Moreno, J.J.; Juncos, J.M. Pediatric Facial Fractures: Children Are Not Just Small Adults. Radiographics 2008, 28, 441–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncar, R.I.; Moca, A.E.; Juncar, M.; Moca, R.T.; Țenț, P.A. Clinical Patterns and Treatment of Pediatric Facial Fractures: A 10-year retrospective Romanian study. Children 2023, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez Roselló, E.; Quiles Granado, A.M.; Artajona Garcia, M.; Juanpere Martí, S.; Laguillo Sala, G.; Beltrán Mármol, B.; Pedraza Gutiérrez, S. Facial fractures: Classification and highlights for a useful report. Insights Imaging 2020, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M. A Survey on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Med. Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, J.; Wang, L.; Rao, J.; Lim, T. Deep Learning Applications in Medical Image Analysis: A Review. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 16410–16425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganyadevi, S.; Seethalakshmi, V.; Balasamy, K. A Review on Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Int. J. Multimed. Inf. Retr. 2022, 11, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulinari-Santos, G.; Santana, A.P.; Botacin, P.R.; Okamoto, R. Addressing the Challenges in Pediatric Facial Fractures: A Narrative Review of Innovations in Diagnosis and Treatment. Surgeries 2024, 5, 1130–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.N.; Edwards, M.J.; Srivatsa, S.; Wakeman, D.; Calderon, T.; Lamoshi, A. Clinical and radiographic predictors of the need for facial fracture operative management in children. Trauma Surg. Acute Care Open 2022, 7, e000899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otjen, J.P.; Moore, M.M.; Romberg, E.K.; Perez, F.A.; Iyer, R.S. The current and future roles of artificial intelligence in pediatric radiology. Pediatr. Radiol. 2022, 52, 2065–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundervold, A.S.; Lundervold, A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z. Med. Phys. 2019, 29, 102–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.D.; Holmes, S.B.; Coulthard, P. A review on artificial intelligence for the diagnosis of fractures in facial trauma imaging. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 6, 1278529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, H.R.; Lu, L.; Seff, A.; Cherry, K.M.; Hoffman, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Turkbey, E.; Summers, R.M. A New 2.5D Representation for Lymph Node Detection Using Random Sets of Deep Convolutional Neural Network Observations. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2014; Golland, P., Hata, N., Barillot, C., Hornegger, J., Howe, R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 2021, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parekh, V.S.; Jacobs, M.A. Radiomics: A new application from established techniques. Expert Rev. Precis. Med. Drug Dev. 2016, 1, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaraju, R.R.; Cogswell, M.; Das, A.; Vedantam, R.; Parikh, D.; Batra, D. Grad-CAM: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2020, 128, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjoa, E.; Guan, C. A survey on explainable artificial intelligence (XAI): Toward medical XAI. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A comprehensive survey on transfer learning. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieke, N.; Hancox, J.; Li, W.; Milletari, F.; Roth, H.R.; Albarqouni, S.; Bakas, S.; Galtier, M.N.; Landman, B.A.; Maier-Hein, K.; et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.J.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Suleyman, M.; Corrado, G.; King, D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, K.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Yin, H.; Kautz, J.; Molchanov, P. UNETR: Transformers for 3D medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE TPAMI 2019, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheller, M.J.; Reina, G.A.; Edwards, B.; Martin, J.; Bakas, S. Federated learning in medicine: Facilitating multi-institutional collaborations. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghassemi, M.; Naumann, T.; Schulam, P.; Beam, A.L.; Chen, I.Y.; Ranganath, R. Practical guidance on artificial intelligence for health-care data. Lancet Digit. Health 2019, 1, e157–e159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.