The Effects of Parabolic Arc Height and Velocity of a Target During Interception on Forward Reach Movement Mechanics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Aim 1: Evaluate how changes in parabolic vertex height to intercept an object in virtual reality affect task success.

- Aim 2: Evaluate how changes in parabolic vertex height to intercept an object in virtual reality influence movement mechanics.

- Aim 3: Determine how object velocity modulation in virtual reality affects task success during interception.

- Aim 4: Determine how object velocity modulation in virtual reality influences movement mechanics during interception.

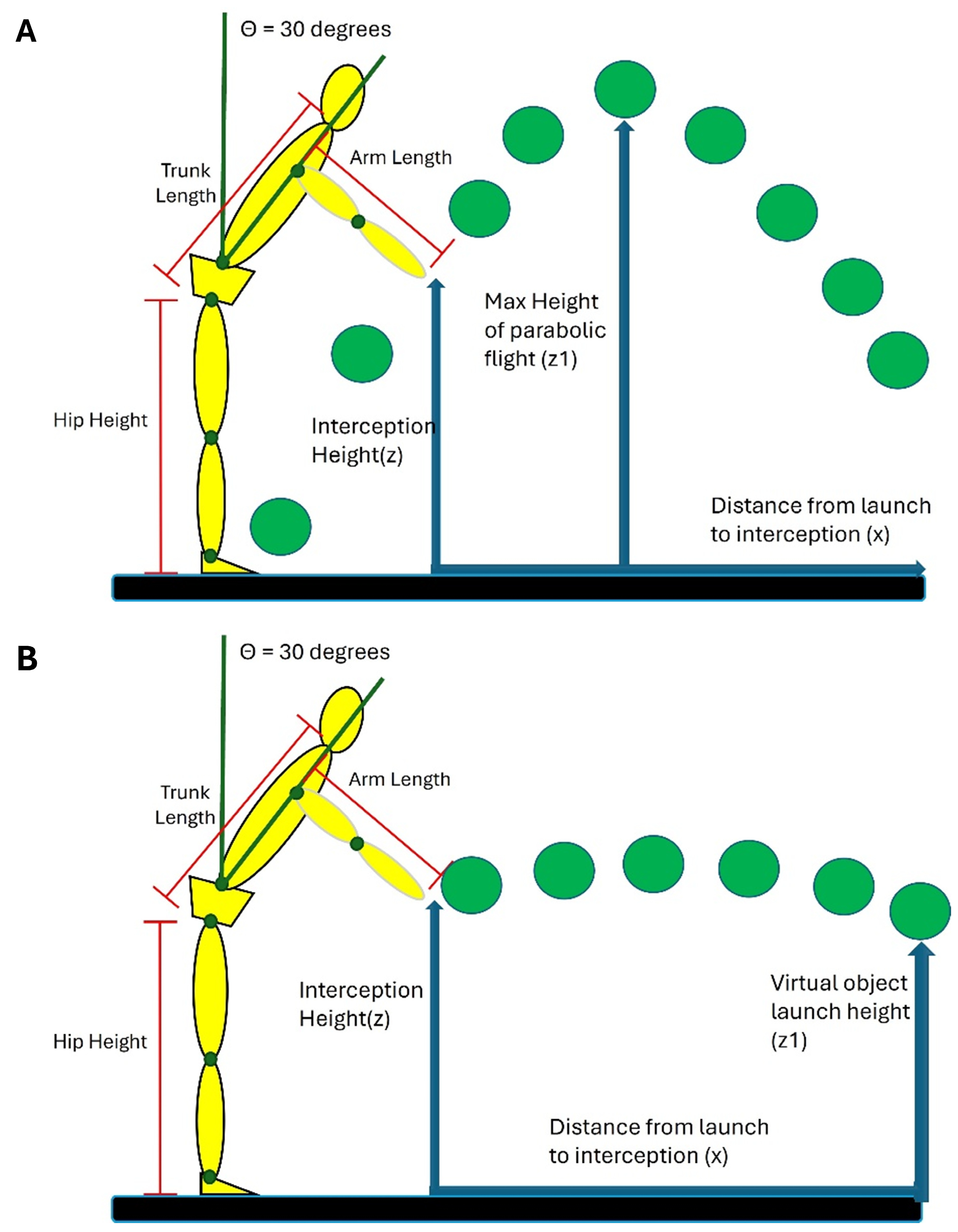

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Gameplay

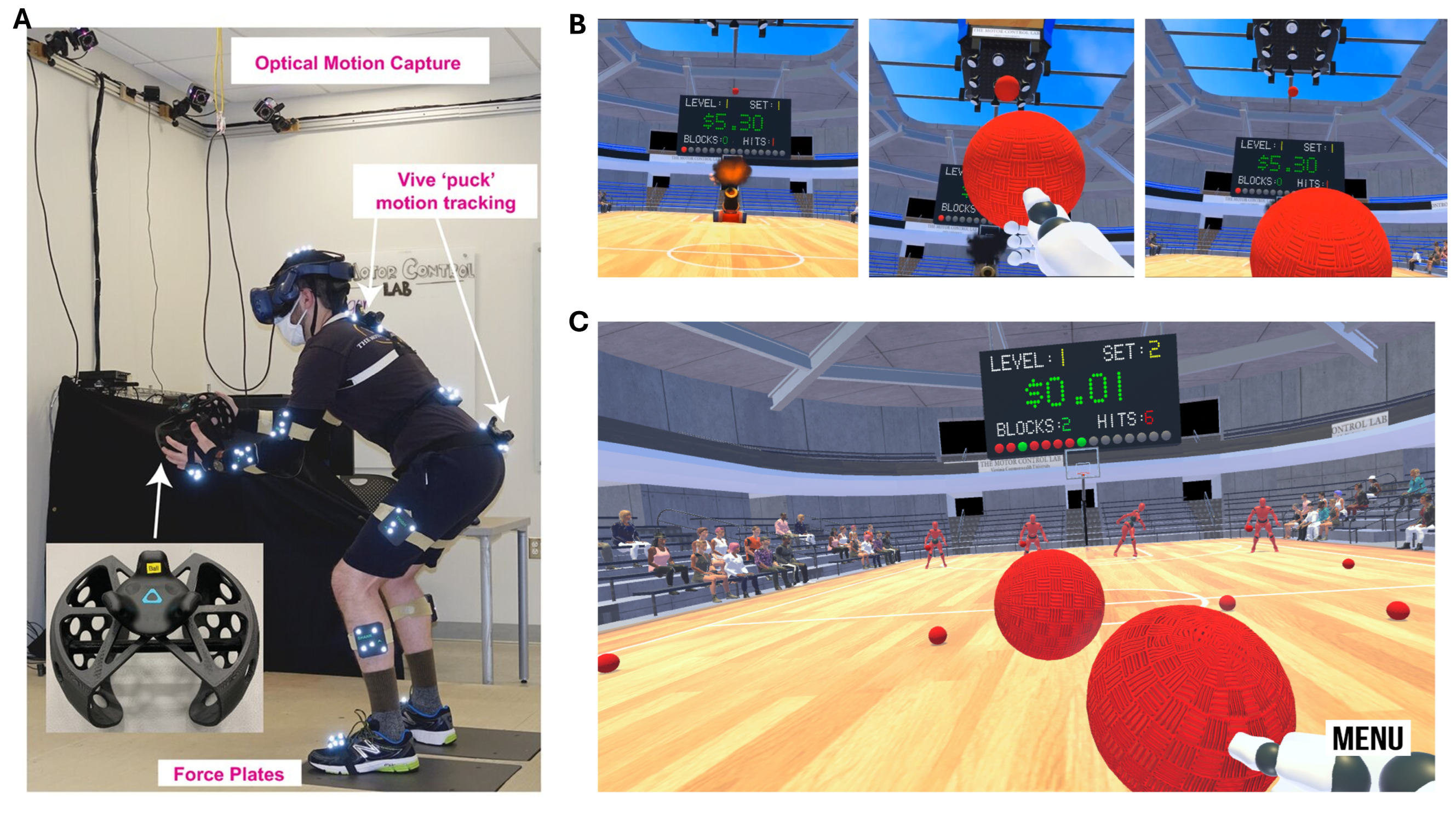

2.3. Instrumentation

2.4. Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

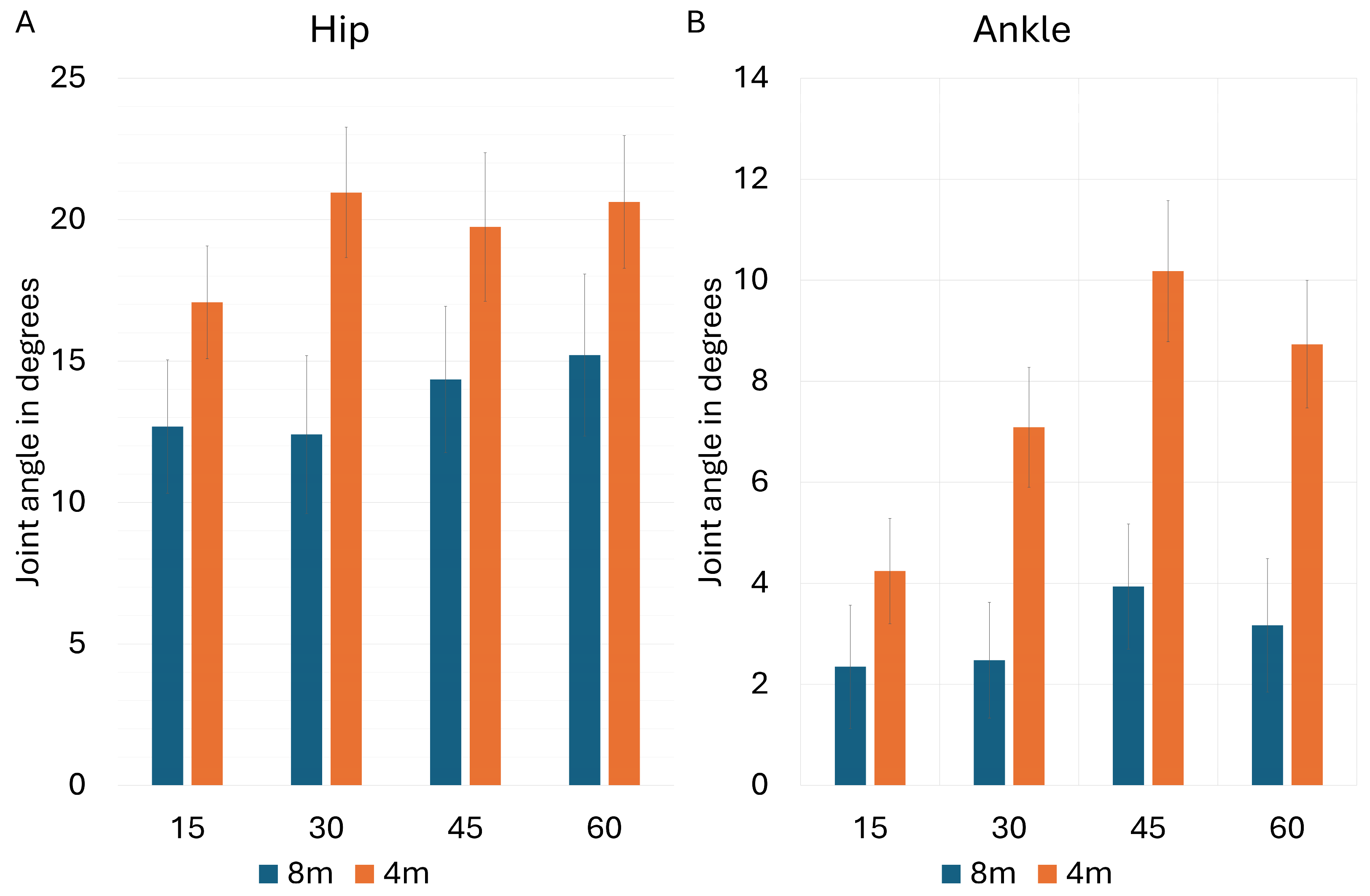

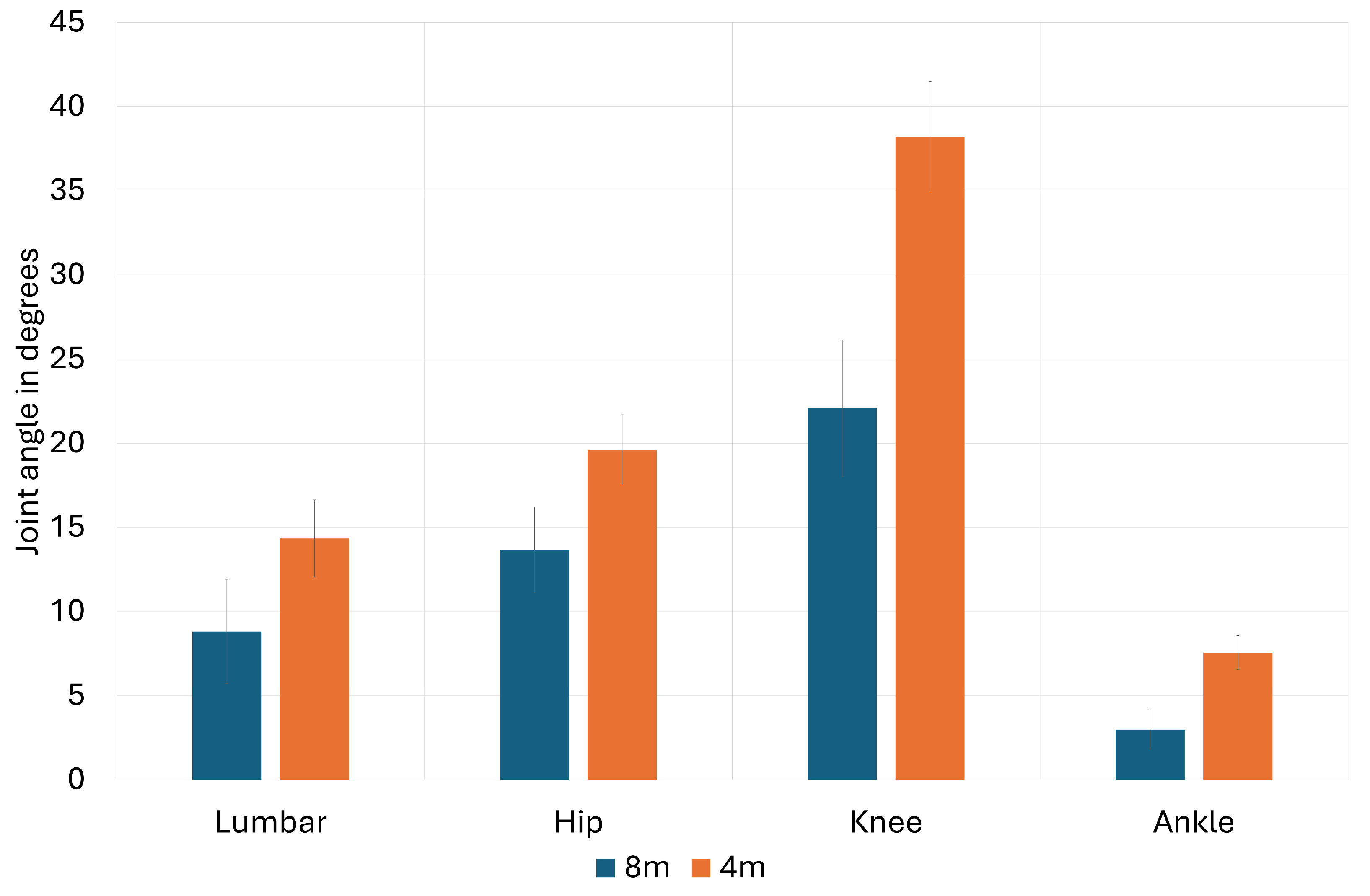

3.1. Parabolic Launch Vertex Height

3.2. Launch Velocity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Dijsseldonk, R.B.; De Jong, L.A.F.; Groen, B.E.; Van Der Hulst, M.V.; Geurts, A.C.H.; Keijsers, N.L.W. Gait stability training in a virtual environment improves gait and dynamic balance capacity in incomplete spinal cord injury patients. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 411121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, J.; Richards, C.L.; Malouin, F.; McFadyen, B.J.; Lamontagne, A. A Treadmill and Motion Coupled Virtual Reality System for Gait Training Post-Stroke. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2006, 9, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osumi, M.; Inomata, K.; Inoue, Y.; Otake, Y.; Morioka, S.; Sumitani, M. Characteristics of Phantom Limb Pain Alleviated with Virtual Reality Rehabilitation. Pain Med. 2019, 20, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, A.; Reger, G.; Perlman, K.; Rothbaum, B.; Difede, J.; McLay, R.; Graap, K.; Gahm, G.; Johnston, S.; Deal, R.; et al. Virtual reality posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exposure therapy results with active duty OIF/OEF service members. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2011, 10, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.H.; Lin, Y.F.; Chai, H.M.; Han, Y.C.; Jan, M.H. Comparison of proprioceptive functions between computerized proprioception facilitation exercise and closed kinetic chain exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin. Rheumatol. 2006, 26, 520–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Liang, H.N.; Yu, K.; Baghaei, N. Effect of Gameplay Uncertainty, Display Type, and Age on Virtual Reality Exergames. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallavicini, F.; Pepe, A. Virtual Reality Games and the Role of Body Involvement in Enhancing Positive Emotions and Decreasing Anxiety: Within-Subjects Pilot Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e15635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, G.; Garrett, B.; Taverner, T.; Cordingley, E.; Sun, C. Immersive virtual reality health games: A narrative review of game design. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2021, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.S.; France, C.R. The relationship between pain-related fear and lumbar flexion during natural recovery from low back pain. Eur. Spine J. 2008, 17, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; France, C.R. Pain-Related Fear Is Associated with Avoidance of Spinal Motion During Recovery from Low Back Pain. Spine 2007, 32, E460–E466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J.F. Motion sickness susceptibility questionnaire revised and its relationship to other forms of sickness. Brain Res. Bull. 1998, 47, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, C.R.; Thomas, J.S. Virtual immersive gaming to optimize recovery (VIGOR) in low back pain: A phase II randomized controlled trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2018, 69, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; France, C.R.; Applegate, M.E.; Leitkam, S.T.; Walkowski, S. Feasibility and Safety of a Virtual Reality Dodgeball Intervention for Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Pain 2016, 17, 1302–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; France, C.R.; Leitkam, S.T.; Applegate, M.E.; Pidcoe, P.E.; Walkowski, S. Effects of real-world versus virtual environments on joint excursions in full-body reaching tasks. IEEE J. Transl. Eng. Health Med. 2016, 4, 2100608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; Corcos, D.M.; Hasan, Z. The Influence of Gender on Spine, Hip, Knee, and Ankle Motions During a Reaching Task. J. Mot. Behav. 1998, 30, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; Gibson, G.E. Coordination and timing of spine and hip joints during full body reaching tasks. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2007, 26, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, W.H. Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN: The Art of Scientific Computing, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Putawa, R.A.; Sugianto, D. Exploring User Experience and Immersion Levels in Virtual Reality: A Comprehensive Analysis of Factors and Trends. Int. J. Res. Metav. 2024, 1, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Choi, S.; Lee, M.; Kim, K. Investigating Key User Experience Factors for Virtual Reality Interactions. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2017, 36, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owings, T.M.; Lancianese, S.L.; Lampe, E.M.; Grabiner, M.D. Influence of ball velocity, attention, and age on response time for a simulated catch. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maselli, A.; De Pasquale, P.; Lacquaniti, F.; d’Avella, A. Interception of virtual throws reveals predictive skills based on the visual processing of throwing kinematics. iScience 2022, 25, 105212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Veen, S.M.; Stamenkovic, A.; Applegate, M.E.; Leitkam, S.T.; France, C.R.; Thomas, J.S. Effects of Avatar Perspective on Joint Excursions Used to Play Virtual Dodgeball: Within-Subject Comparative Study. JMIR Serious Games 2020, 8, e18888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenkovic, A.; Underation, M.; Cloud, L.J.; Pidcoe, P.E.; Baron, M.S.; Hand, R.; France, C.R.; van der Veen, S.M.; Thomas, J.S. Assessing perceptions to a virtual reality intervention to improve trunk control in Parkinson’s disease: A preliminary study. Virtual Real. 2023, 27, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.S.; France, C.R.; Applegate, M.E.; Leitkam, S.T.; Pidcoe, P.E.; Walkowski, S. Effects of Visual Display on Joint Excursions Used to Play Virtual Dodgeball. JMIR Serious Games 2016, 4, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistemaker, D.A.; Faber, H.; Beek, P.J. Catching fly balls: A simulation study of the Chapman strategy. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2009, 28, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varon, S.; Babin, K.; Spering, M.; Culham, J.C. Target interception in virtual reality is better for natural versus unnatural trajectory shapes and orientations. J. Vis. 2025, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, A.; Frolov, A.; Massion, J. Axial synergies during human upper trunk bending. Exp. Brain. Res. 1998, 118, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stapley, P.J.; Pozzo, T.; Cheron, G.; Grishin, A. Does the coordination between posture and movement during human whole-body reaching ensure center of mass stabilization? Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 129, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.S.; Corcos, D.M.; Hasan, Z. Effect of movement speed on limb segment motions for reaching from a standing position. Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 148, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ida, H.; Fukuhara, K.; Ogata, T. Virtual reality modulates the control of upper limb motion in one-handed ball catching. Front. Sports Act. Living 2022, 4, 926542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, A.W.; Seng, C.N. Visual Movements of Batters. Res. Q. Am. Assoc. Health Phys. Educ. Recreat. 1954, 25, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsumata, H. A functional modulation for timing a movement: A coordinative structure in baseball hitting. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2007, 26, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition Tested | Factor(s) | Dependent Variable | df (Between, Within) | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parabolic Height | Height × Interception Height | Success Rate | (3, 19) | 10.887 | <0.001 * | 0.608 |

| Parabolic Height | Success Rate | (1, 21) | 13.335 | <0.001 * | 0.388 | |

| Interception Height | Success Rate | (3, 19) | 4.841 | 0.011 * | 0.433 | |

| Launch Velocity | Velocity × Interception Height | Success Rate | (3, 19) | 10.887 | <0.001 * | 0.632 |

| Launch Velocity | Success Rate | (1, 21) | 31.900 | <0.001 * | 0.603 | |

| Interception Height | Success Rate | (3, 19) | 148.558 | <0.001 * | 0.959 |

| Condition | Factor Level | Mean ± SD (%) | Post hoc Differences (p < 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parabolic Height | 4 m | 92.6 ± 1.8 | >8 m |

| 8 m | 83.3 ± 3.6 | — | |

| Interception Height | 15° | 94.3 ± 1.6 | >30°, 45°, 60° |

| 30° | 91.7 ± 2.2 | >45°, 60° | |

| 45° | 86.0 ± 3.4 | >60° | |

| 60° | 79.9 ± 4.5 | — | |

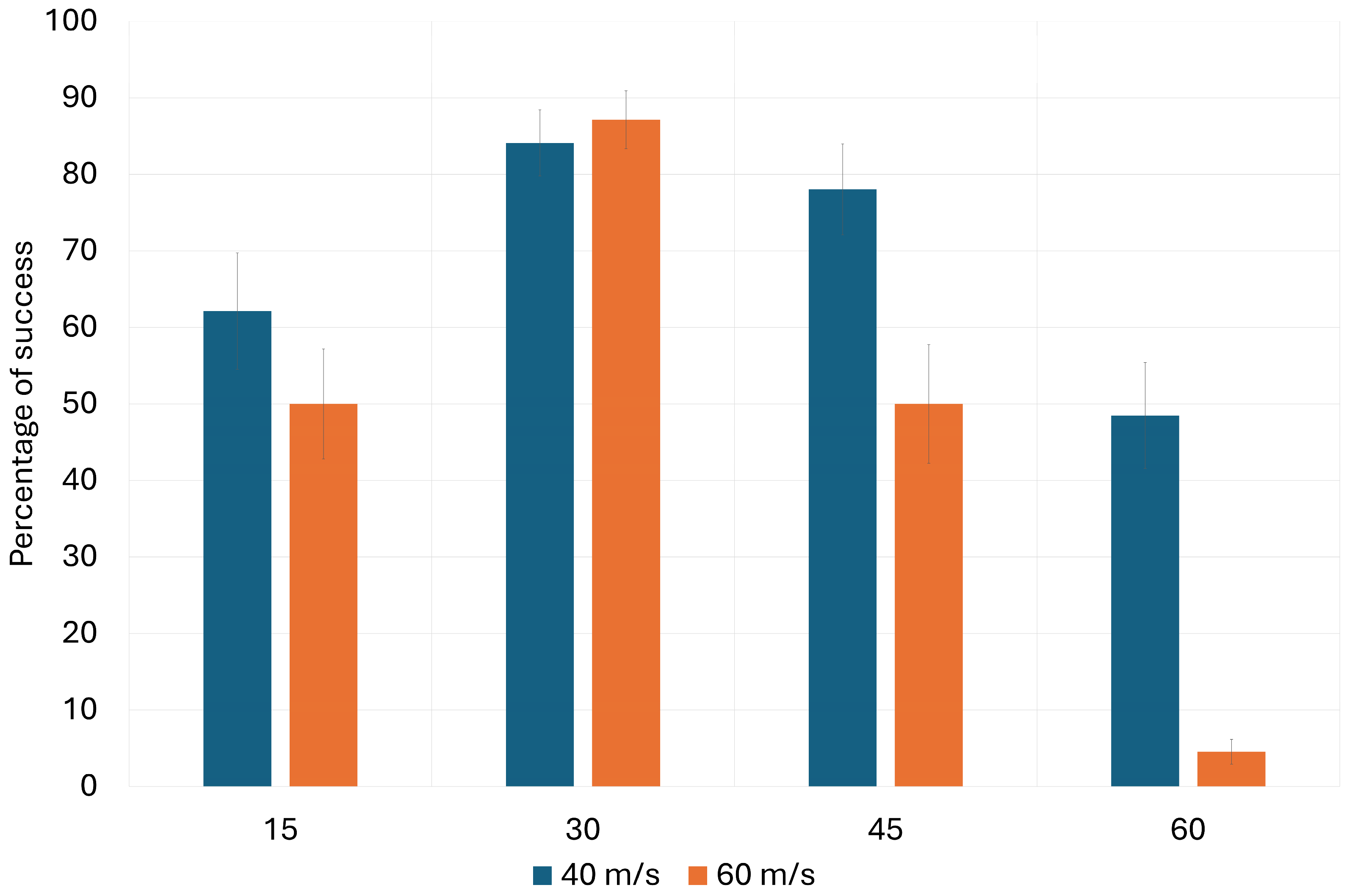

| Launch Velocity | 40 m/s | 68.2 ± 3.4 | >60 m/s |

| 60 m/s | 47.9 ± 2.2 | — | |

| Interception Height (Velocity Test) | 15° | 56.0 ± 6.6 | >60° |

| 30° | 85.6 ± 3.0 | >45°, 60° | |

| 45° | 64.0 ± 6.1 | >60° | |

| 60° | 26.5 ± 3.8 | — |

| Dependent Variable | Factor (s) | df (Between, Within) | F | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip Angle | Parabolic Height × Interception Height | (3, 16) | 3.876 | 0.029 * | 0.421 |

| Ankle Angle | Parabolic Height × Interception Height | (3, 17) | 3.585 | 0.036 * | 0.387 |

| Lumbar Angle | Parabolic Height | (1, 16) | 6.055 | 0.026 * | 0.275 |

| Hip Angle | Parabolic Height | (1, 18) | 6.594 | 0.019 * | 0.268 |

| Knee Angle | Parabolic Height | (1, 20) | 32.138 | <0.001 * | 0.616 |

| Ankle Angle | Parabolic Height | (1, 19) | 14.281 | 0.001 * | 0.429 |

| Knee Angle | Interception Height | (3, 18) | 8.827 | <0.001 * | 0.595 |

| Ankle Angle | Interception Height | (3, 17) | 6.831 | 0.003 * | 0.547 |

| Knee Velocity | Parabolic Height | (1, 21) | 4.409 | 0.048 * | 0.174 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

van der Veen, S.M.; Stamenkovic, A.; Abtahi, F.; Thomas, J.S. The Effects of Parabolic Arc Height and Velocity of a Target During Interception on Forward Reach Movement Mechanics. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010144

van der Veen SM, Stamenkovic A, Abtahi F, Thomas JS. The Effects of Parabolic Arc Height and Velocity of a Target During Interception on Forward Reach Movement Mechanics. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010144

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan der Veen, Susanne M., Alexander Stamenkovic, Forough Abtahi, and James S. Thomas. 2026. "The Effects of Parabolic Arc Height and Velocity of a Target During Interception on Forward Reach Movement Mechanics" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010144

APA Stylevan der Veen, S. M., Stamenkovic, A., Abtahi, F., & Thomas, J. S. (2026). The Effects of Parabolic Arc Height and Velocity of a Target During Interception on Forward Reach Movement Mechanics. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010144