Abstract

Ensuring good air quality in indoor environments of historical and artistic significance is essential not only for protecting valuable artworks but also for safeguarding human health. While many studies in this field tend to focus on the preservation of cultural heritage, fewer have addressed the impact on visitors and worshippers. Yet, places such as museums, galleries, churches, and other religious sites attract large numbers of people, making indoor air quality a key factor for their well-being. This study focused on evaluating air quality within the Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracoli in Saronno, Italy, a religious site that welcomes large numbers of visitors and worshippers each year. A detailed analysis of particulate matter was conducted, including chemical characterization by ICP-MS for metals, ion chromatography for water-soluble ions, and thermal–optical analysis for the carbonaceous fraction, as well as assessments of size distribution and radiometric properties. The results indicated overall good air quality conditions: concentrations of heavy metals were below levels of concern (<35 ng m−3), and gross alpha, beta, and 137Cs activity concentrations remained below the minimum detectable thresholds. Hence, no significant health risks were identified.

1. Introduction

Indoor air quality is a critical issue, particularly given the increasing amount of time people spend indoors [1,2,3]. Monitoring is challenging due to the heterogeneity of indoor environments, which makes it difficult to assess pollutant levels and establish regulatory limits comparable to those applied outdoors. While some countries have implemented guidelines for specific sensitive indoor environments [4], such as workplaces or areas with known pollutant risks, many other indoor settings remain largely unmonitored. Religious heritage sites, such as historic sanctuaries, represent a distinct category of indoor environments that are often overlooked. In such spaces, air quality standards are typically assessed with a focus on the preservation of artworks and cultural heritage, rather than the health of visitors and staff [5,6,7,8]. Yet, like any other indoor environment, these sites require careful monitoring, as they too can act as reservoirs for specific pollutants [9,10,11].

Particulate matter (PM) is one of the primary pollutants that can accumulate indoors and pose a significant health risk. This is particularly true for the fine fraction (PM2.5), which can penetrate deep into the respiratory system and exert harmful effects. Importantly, the health impact of PM is determined not only by particle size but also by its chemical composition [12]. Certain components, such as heavy metals, can exert a much more direct and severe impact on human health, whereas others may be comparatively inert [13]. For this reason, the relationship between particle size and composition is being investigated in increasing depth through progressively more advanced techniques and methodologies [14]. Radiometric analysis of PM is another type of assessment that is rarely applied to samples collected in indoor environments. As with other major air pollutants, existing regulations and technical standards refer exclusively to outdoor (ambient) PM, with no specific provisions for indoor settings. As a result, the body of available data on indoor PM obtained through radiometric methods remains very limited in the literature.

In particular, the measurement of radioactivity content in atmospheric PM is carried out to monitor the activity concentration of radionuclides present in the non-gaseous suspension in the atmosphere. This material can consist of organic or inorganic compounds of anthropogenic origin, organic material from plants, inorganic material produced by natural agents, and soil erosion [15]. In urban areas, PM can originate from industrial processes, heating systems, wear of asphalt, tires, brakes, and exhaust emissions from vehicles. Measurement of radioactivity content in atmospheric PM also allows for the identification of potential contaminations due to the presence of radionuclides in the air, which can either fall from higher layers of the atmosphere or be resuspended from contaminated soil [16]. Within the scope of radioprotection, the effective dose is the fundamental quantity used to assess the significance of the exposure of individuals of the population to ionizing radiation, albeit with limitations and uncertainties for a quantitative evaluation of the risk of stochastic health effects in individuals [17].

Nevertheless, in recent years, several studies have begun to highlight a direct relationship between particle radioactivity and adverse health effects [18,19,20,21]. Current research is increasingly focused on identifying the specific sources and chemical components that may contribute to elevated radiometric activity in airborne particles. To date, most investigations have concentrated on ambient air, revealing the influence of regional pollution and motor vehicle emissions on alpha and beta activities [19], as well as a direct association between Zn and elemental carbon (EC) with particle alpha activity [22]. Fewer studies have addressed indoor environments; however, one such investigation reported significant correlations between alpha activities and multiple PM components, including S, Fe, Br, V, Na, Pb, K, Ca, Si, Zn, As, Ti, and black carbon (BC) [18].

With the aim of deepening the understanding of the relationship between particle chemical composition and their radioactivity, this work combines detailed chemical characterization (organic carbon, elemental carbon, water-soluble ions, and toxicologically relevant heavy metals) with radiometric profiling of PM, an approach rarely applied to indoor environments. Sampling and analysis were conducted inside the Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracoli, a historic sanctuary located in Saronno (VA), Italy. The site attracts large numbers of worshippers and visitors, not only for its religious significance but also for its collection of artworks, including frescoes and wooden paintings. While a previous study on indoor air quality at this location focused primarily on the preservation of cultural heritage [23], the present investigation shifts the focus toward potential health implications for occupants. To this end, the collected PM was chemically characterized to determine its major components (organic carbon, elemental carbon, and water-soluble ions). In addition, heavy metals of toxicological relevance were quantified in all filter samples, and radiometric analyses were also performed. Finally, parallel measurement of the three most important dimensional fractions of particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5, and PM1) was carried out to provide a more comprehensive assessment of air quality within the sanctuary.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Particulate Matter Sampling

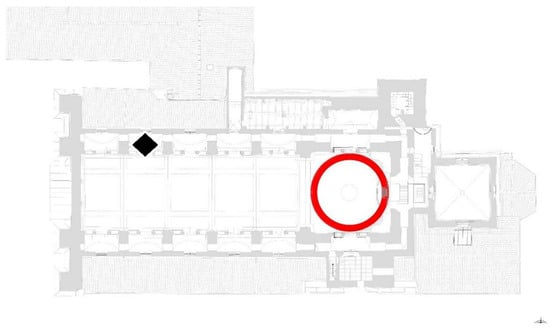

Total suspended particulates were sampled on quartz fiber filters (O = 101.6 mm) using a high-volume sampler (ECHO Emergency, TECORA, Cogliate, Italy) equipped with a noise-reducing casing that minimizes the sound produced by the high-volume pump, at a flux rate of 100 L min−1. Despite noise reduction, the instrument was placed on the west wing of the upper floor of the sanctuary (Figure 1) to minimize the disturbance to worshippers and visitors. A previous study on air quality conducted within the sanctuary did not show significant differences in PM concentration between the upper and lower floors of the building, due solely to height [23]. Hence, the location is considered representative of the conditions within the sanctuary.

Figure 1.

Planimetry of the first floor of the sanctuary. The black diamond indicates the location of the high-volume sampler.

The sampling location was chosen in accordance with the recommendations of the Italian Technical Guide on Environmental Radioactivity Measurements [24]. The sampler was positioned at approximately 3.5 m above ground level, in an open area protected from environmental disturbances at the far end of the upper floor left corridor.

Three filters were collected to assess the air quality conditions within the investigated site, and an additional filter was sampled at the chemistry department of the University of Milan as a reference (Table 1).

Table 1.

Particulate matter sampling details.

2.2. Chemical Characterization of Particulate Matter

All filters analyzed were pre-conditioned under controlled temperature and humidity conditions and repeatedly weighed until stability was achieved. Filters were considered valid only when the variation among the last three consecutive measurements was ≤0.001 g. The same conditioning and weighing procedures were applied after sampling, once particulate matter had been collected on the filters. Field blanks and laboratory blanks were also included to verify potential contamination, and their values were negligible compared to sample concentrations, confirming the absence of significant contamination.

The carbonaceous fraction was analyzed using a thermal–optical analyzer (OC-EC Lab Instrument, Model 5, Sunset Laboratory Inc., Tigard, OR, USA) working in transmittance mode and applying the NIOSH-870 as the thermal protocol. Calibration was performed using sucrose as the external standard in the range 0–400 μgC.

Instead, ion chromatography was employed to evaluate the concentration of water-soluble ions. Sample preparation was performed by extracting a 1.5 cm2 punch in 5 mL of ultrapure water (milli-Q Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) using an ultrasonic bath (<20 °C) for 30 min. Prior to injection, the solutions were filtered with 0.22 μm PVDF filters (25 mm, GVS, Sanford, ME, USA) to remove remaining particulates. Analysis was performed with a Dionex ICS-5000+ ion chromatography system (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for both anions (SO42−, Br−, Cl−, NO3−, and NO2−) and cations (Na+, NH4+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+).

The former were analyzed using a Dionex IonPac AG11 (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) guard column (13 μm, 4 × 50 mm), Dionex IonPac AS11 (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) analytical column (13 μm, 4 × 250 mm), Dionex ADRS 600 (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) suppressor (4 mm), and a conductimetric detector. Elution was performed in isocratic conditions using a 12 mM NaOH as the eluent and a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, setting the temperature of the column to 30 °C and that of the detection compartment to 15 °C.

Instead, cations were analyzed using a Dionex IonPac CG12A (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) guard column (8.5 μm, 4 × 50 mm), Dionex IonPac CS12A (Thermo Scientific Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) analytical column (8.5 μm, 4 × 250 mm), Dionex CDRS 600 (Thermo Scienfitic Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) suppressor (4 mm), and a conductimetric detector. Elution was performed in isocratic conditions with 20 mM methanesulfonic acid as the eluent, a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, setting the temperature of the column to 30 °C and that of the detection compartment to 15 °C.

Quantitative analysis was performed via external calibration using ten-point calibration curves for each ion between 0.1 and 20 ppm. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit quantification (LOQ) were determined by assessing the variability of the lowest standard closest to the probable LOD: chlorine: y = 0.229x − 0.05, R2 = 0.998, LOD = 0.22 ppm, LOQ = 0.74 ppm; nitrates: y = 0.128x − 0.03, R2 = 0.998, LOD = 0.09 ppm, LOQ = 0.32 ppm; sulfates: y = 0.131x + 0.006, R2 = 0.996, LOD = 0.06 ppm, LOQ = 0.19 ppm; bromides: y = 0.092x − 0.04, R2 = 0.998, LOD = 0.20 ppm, LOQ = 0.68 ppm; nitrites: y = 0.156x − 0.022, R2 = 0.9996, LOD = 0.06 ppm, LOQ = 0.18 ppm; sodium: y = 0.213x + 0.042, R2 = 0.998, LOD = 0.06 ppm, LOQ = 0.15 ppm; ammonium: y = 0.249x + 0.009, R2 = 0.994, LOD = 0.07 ppm, LOQ = 0.17 ppm; potassium: y = 0.155x, R2 = 0.9995, LOD = 0.03 ppm, LOQ = 0.06 ppm; Calcium: y = 0.277x, R2 = 0.9992, LOD = 0.09 ppm, LOQ = 0.32 ppm; magnesium: y = 0.507x, R2 = 0.9994, LOD = 0.02 ppm, LOQ = 0.06 ppm.

The concentration of heavy metals was obtained through ICP-MS analysis using a iCAP Qc ICP-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). A quartz microfiber punch area of 50 mm2 was retrieved from each filter and underwent acid digestion using a Milestone microwave unit system, Ethos touch control. Digestion was performed by adding 2 mL of ultrapure (67%) HNO3 and 1 mL of distilled water into a quartz insert, which was then placed in a 100 mL TFM vessel. Additionally, 5 mL of distilled H2O and 1 mL of H2O2 (30%) were placed directly in the TFM vessel, around the quartz insert, to a depth equal to the height of the liquid inside the quartz insert. The whole process was performed in three steps: 15 min at 1000 W and 200 °C; 10 min at 700 W and 200 °C; 10 min cooling [25]. After cooling, the contents of the quartz insert were filtered and made up to 50 mL with distilled H2O in a 50 mL perfluoroalkoxy–copolymer (PFA) Class A volumetric flask. The sample introduction system consisted of a Peltier-cooled (3 °C), baffled cyclonic spray chamber, PFA nebulizer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), and quartz torch (Thermo Fisher Scintific, Bremen, Germany) with a 2.5 mm i.d. removable quartz injector. The instrument was operated in a single collision cell mode, with kinetic energy discrimination (KED), using pure He as the collision gas. All the LOQs of the analyzed metals were below 1 ppb, which is a significant fraction of the limit values at the European level.

2.3. Radiometric Analysis and Radiological Hazard Effects Assessment

The assessment of the radioactivity content in the investigated samples was carried out through gross alpha and beta and HPGe gamma spectrometry analysis, according to the Italian Higher Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA) guidelines [26]. The gross alpha and beta activity concentrations are two screening parameters: only if they are greater than the MDC (minimum detectable activity concentration), the specific activity of individual natural alpha and beta-emitting radionuclides has to be measured through HPGe gamma spectrometry, to further evaluate radiological hazard effects for humans in terms of effective dose for inhalation. Additionally, for the assessment of potential anthropogenic contamination, the activity concentration of the radionuclide Cs-137 must be quantified [27].

In detail, for the evaluation of the gross alpha and beta specific activities, the measurement must be taken at least 120 h after the filter is removed, to allow natural radionuclides with a short half-life to decay. No special pre-treatment of the filter is necessary; it is sufficient that the diameter of the filter is compatible with that of the detector [26]. In our study, samples were counted for 5400 s by using the Else ALBA/LLAB setup [28], with a plastic scintillator (for beta particle counting) and a zinc sulfide (for alpha particle counting) as measurement detectors. A plastic scintillator (for gamma photon counting) was also employed as a screen detector. The counting efficiency was 43.4% for alpha and 28.6% for beta particles. The background was 0.0044 counts per second (cps) for alpha and 0.043 cps for beta particles.

The gross alpha and beta activity concentration (Bq m−3) was calculated using the following formula [26]:

where counts indicates net alpha and beta counts, ε is the counting efficiency, V is the sampled PM volume (m3), and t is the live time (s).

Moreover, with reference to the HPGe gamma spectrometry analysis, samples were counted for 70,000 s to reduce statistical uncertainty, and spectra were analyzed to obtain the specific activity of investigated radionuclides [29].

The experimental set-up consisted of a negatively biased GMX-series HPGe detector (ORTEC, Ametek ORTEC Division, Oak Ridge, TN, USA), the operating parameters of which are given in Table 2 [30].

Table 2.

GMX detector settings.

The detector was placed in lead wells to safeguard it from the background radiation coming from the environment, and efficiency and energy calibrations were performed using a multi-peak plastic disc foil gamma source (Eckert & Ziegler AH-1337), covering the energy range 59.54 keV–1836 keV, customized to reproduce the exact geometries of samples. The Gamma Vision (Ortec) 8.1 software was used for data acquisition and analysis [30].

The activity concentration (Bq m−3) of investigated radionuclides was estimated as follows [31]:

where NE indicates the net area of a peak at energy E; εE and γd are the efficiency and yield of the photopeak at energy E, respectively; V is the volume of sampled particulate matter (m3); and t is the live time (s). The accuracy and repeatability of the results were certified by the Italian Accreditation Body (ACCREDIA) [32].

Finally, when the MDC for gross alpha and beta activities, calculated according to [26], is exceeded, the assessment of radiological hazard effects has to be made in terms of the effective dose for inhalation, estimated with the following [27]:

where hj,inh is the effective dose coefficient for inhalation of the j-th natural radionuclide (Sv Bq−1), and Jj,inh is the intake of the j-th natural radionuclide (Bq year−1), respectively. The latter value is obtained by multiplying the number of hours per year spent in contact with samples for the activity concentration of the natural radionuclide (Bq m−3), and for the breathing factor (m3 h−1). The effective dose for inhalation must be lower than the limit of 300 μSv year−1 reported in Legislative Decree 101/20 with reference to naturally occurring radionuclides [33], to reasonably exclude a radiological hazard for the population associated with inhalation of the investigated particulate matter.

2.4. Particulate Matter Concentration Measurement

A portable optical particle counter was placed in parallel to the high-volume sampler to obtain highly time-resolved measurements of particulate matter. The sensor operates on the principle of laser light scattering: a laser diode illuminates the airflow generated by an integrated micro fan, and a photo detector measures the intensity of the scattered light. The sensor’s internal microcontroller then processes this signal to determine the size and number of particles. Conversion from particle number concentration to mass concentration (μg m−3) is performed on board using factory-calibrated algorithms, providing real-time output for the PM1, PM2.5, and PM10 fractions via a UART interface. The sensor was connected to a microcontroller running custom firmware. The system operated in ‘Start-Go-Stop’ mode with a time resolution of 15 s. The fan was activated for a stabilization period to ensure laminar flow and equilibrium with the environment before data acquisition. The data were stored and displayed remotely via a dual Bluetooth–GPRS telecommunication channel.

3. Results

3.1. Carbonaceous Fraction and Inorganic Soluble Ions

The carbonaceous fraction and water-soluble inorganic ions constitute the main components of both indoor and ambient particulate matter. This was also the case for the samples collected inside the sanctuary, and Table 3 provides the concentrations for all the measured species.

Table 3.

Organic carbon (OC), elemental carbon (EC), and water-soluble inorganic ions concentrations in the sanctuary, expressed as µg m−3. All measurements are subject to an experimental error of ±5%.

A previous study highlighted a significant contribution of both indoor and outdoor sources to PM measured within the sanctuary [23]. This is also reflected in the chemical composition of the filters collected in this study (Table 2). Indeed, high levels of OC are typical of indoor spaces [34], originating from various internal sources, along with limited air exchange, selective deposition, and indoor chemical reactions [35]. Preliminary investigations in the sanctuary showed incense burning, candle burning, and cleaning operations as the main indoor contributors to PM measured within the sanctuary. This is in line with the chemical composition results since small combustion sources are known to release a significant amount of OC, and regular cleaning tasks, such as vacuuming, also play a role in raising OC levels indoors [9].

At the same time, the data revealed an influence of outdoor sources on indoor air quality. This is reflected in the non-negligible concentrations of SO42− and NO3−, which mainly originate from secondary aerosols formed outdoors, where precursors and atmospheric oxidants are more abundant. These findings underscore the role of outdoor PM composition in shaping the indoor particulate profile. Moreover, concentrations of all other species were generally in line with typical values observed in ambient urban background environments in the Lombardy region of Italy [36,37].

3.2. Heavy Metals

Heavy metals of toxicological and regulatory relevance have also been analyzed in PM samples. The elements investigated include As, Cd, Ni (subject to EU target values), and Pb (air quality limit), ensuring compliance and comparability with Directives 2004/107/EC and 2008/50/EC [38,39]. Analytes with the highest documented health impact according to WHO/IARC have been prioritized [40], including recognized carcinogens [41]. Moreover, other elements (V, Cu, and Sb) have been included due to their role as tracers of the major PM sources, such as vehicular traffic, combustion processes, and industrial activities [42].

Table 4 shows the relative average concentrations inside the sanctuary during each sampling period.

Table 4.

Heavy metal concentrations inside the sanctuary, expressed as ng m−3. All measurements are subject to an experimental error of ±5%.

The concentrations of all analyzed metals in the sanctuary are below the limits set by European legislation for PM10. Since TSP was sampled, which includes PM10, values below the thresholds for TSP necessarily imply compliance also for PM10. In addition, all concentrations are below the European recommended thresholds of attention for ambient air. As there are no direct regulatory reference values for indoor air, this represents the only meaningful comparison that can be made. The only exception is Ni in sample 4, which exceeds the attention threshold (10 ng m−3) but remains below the target value established by European legislation (20 ng m−3). The main documented sources of indoor nickel are linked to combustion processes and consumer products [43]. Specifically, indoor nickel can originate from tobacco smoke, dust, cooking (especially with stainless steel utensils), heating appliances, and emissions from outdoor air that infiltrate indoors. Because nickel was detected in only one of the three samples, it is not possible to clearly attribute its specific source in this case.

Overall, these results do not indicate any critical situation within the sanctuary in terms of heavy metal contamination, even when compared with other studies conducted in indoor environments. The concentrations measured are 1–2 orders of magnitude lower than average values reported for indoor air worldwide and remain well below levels typically associated with critical conditions, such as the use of low-quality heating fuels or exposure in highly trafficked urban areas [44].

3.3. Radioactivity and Radiological Health Hazard

Table 5 reports natural and anthropogenic radioactivity results. It is worth noting that the gross alpha and beta activity concentration was found to be lower than the MDC in all cases. These results reasonably exclude a significant natural radioactivity content and thus a radiological hazard for humans associated with inhalation of the investigated particulate matter.

Table 5.

Gross alpha and beta, and 137Cs specific activities.

Furthermore, the activity concentration of 137Cs was lower than the MDC in all cases, thereby excluding any possible anthropogenic contamination of the samples investigated.

Notably, all experimental values agree with the data reported in the Italian radioactivity information system of the Italian National Inspectorate for Nuclear Safety and Radiation Protection (ISIN) for outdoor investigations [45]. Moreover, these results are consistent with those reported in the RADIA database of ISPRA for PM in outdoor environments in areas close to the sampling site [26].

A comprehensive comparison with similar indoor studies is challenging due to the limited research available. Two investigations conducted in residential settings showed that radioactivity levels varied considerably between sampling locations. The two main factors influencing the results were the decay of indoor radon and the infiltration of particles from outdoors [18,46]. This effect was particularly pronounced during the summer months, when air exchange with the outdoor environment is greatest [18]. In the case of radon, the strongest impact was observed in basements [46]. The very low values recorded in the sanctuary may be explained by the fact that sampling was not carried out during the summer and that the sanctuary, although an indoor environment, is very large, making radon accumulation less likely compared to confined spaces such as basements. The most comparable study was conducted in the Wawel Royal Castle Museum in Krakow, Poland, where alpha and beta activity values were found to fall within the variability ranges reported for other indoor environments [47]. However, a direct comparison with our case is complicated by differences in MDCs and by values that lie very close to these thresholds. This underscores the importance of conducting further studies to expand the available dataset and to enable a more comprehensive assessment of conditions and potential health risks in indoor environments.

3.4. Real-Time Measurement of Particulate Matter

Table 6 shows the mean concentrations of the three-dimensional fractions measured with the optical particle counter.

Table 6.

Mean concentrations of PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 inside the sanctuary, expressed as µg m−3. All measurements are subject to an experimental error of ±1 µg m−3.

The results reveal marked differences between sample 3 and the other two, with consistently higher concentrations observed in the former across all three dimensional classes. The findings also emphasize the substantial contribution of the fine fractions (PM2.5 and PM1) to PM10 in all cases. On the one hand, this indicates that concentrations within the sanctuary are not uniform but fluctuate considerably across different sampling periods. On the other hand, regardless of these fluctuations, the contribution of the fine fractions remains consistently significant. Overall, despite the increase in mass PM concentration, this was not accompanied by an increase in radiometric or heavy metal concentrations, as observed by previous investigations.

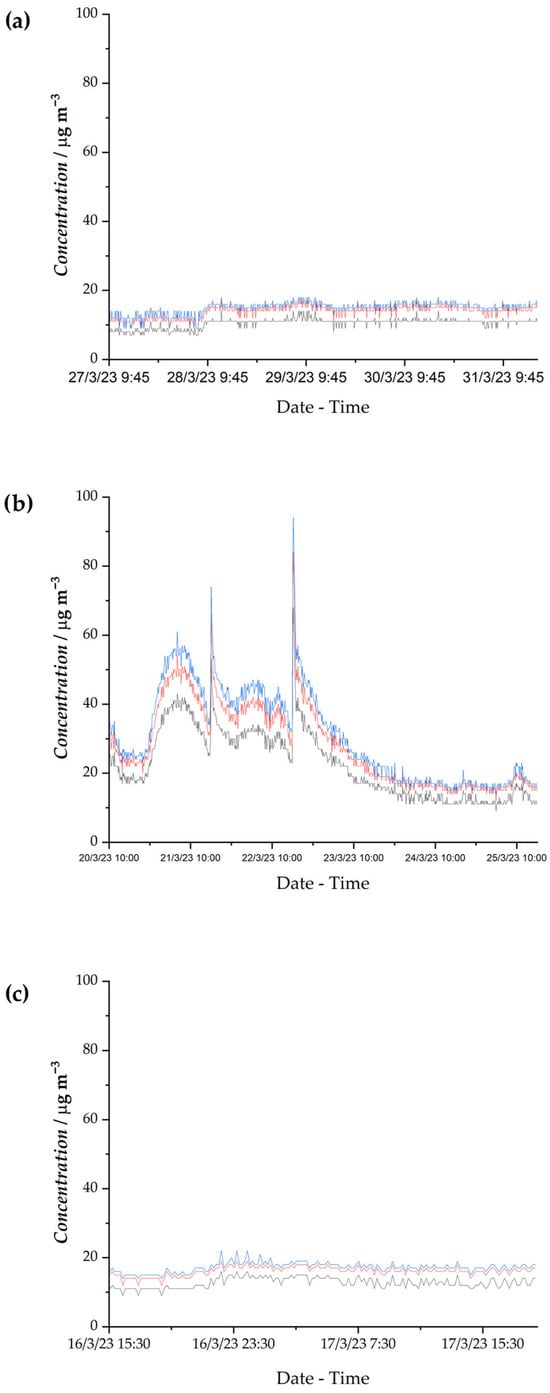

The use of the optical particle counter also allowed for highly time-resolved measurements of the three-dimensional fractions, which are particularly useful in indoor environments to evaluate potential sources of PM (Figure 2). The results show that during the first (27 March 2023, 09:48–31 March 2023, 18:00) and third (16 March 2023, 15:31–17 March 2023, 18:53) sampling periods, concentrations remained relatively stable, generally ranging between 5 and 20 µg m−3, with only a few exceptions. In contrast, the second sampling period (20 March 2023, 10:02–25 March 2023, 16:00) displayed several pronounced spikes in concentration, a typical signature of indoor sources [23]. These peaks exceeded 50 µg m−3 and affected all three dimensional fractions, in line with increased emissions due to candle burning, incense burning, and/or a greater influx of people within the sanctuary [23].

Figure 2.

Trends of PM10 (blue line), PM2.5 (red line), and PM1 (grey line) concentrations in the sanctuary across three sampling periods: (a) 27 March 2023, 09:48–31 March 2023, 18:00; (b) 20 March 2023, 10:02–25 March 2023, 16:00; (c) 16 March 2023, 15:31–17 March 2023, 18:53.

Their impact on the average values was substantial, as the elevated concentrations persisted over extended periods rather than being confined to short events. This highlights both the limited capacity of indoor environments to dissipate pollutants and their tendency to accumulate them, even in large spaces such as the sanctuary. Moreover, this result indicates that the rise in concentration due to indoor activities is not correlated with an increase in health risks due to heavy metal or radiometric concentrations.

4. Conclusions

Building on a preliminary investigation into air quality within the Santuario della Beata Vergine dei Miracoli, this study offers a more in-depth analysis through comprehensive chemical characterization of particulate matter and radiometric measurements. As commonly observed in indoor environments, organic carbon was the predominant constituent of the particles, while other components accounted for a smaller fraction of the mass. This was particularly evident for heavy metals, whose concentrations consistently remained below levels of concern. The results were further evaluated by considering the radioactivity of the particles, assessed through gross alpha and beta activities, as well as 137Cs specific activities. All values were consistently below the minimum detectable concentration (MDC), indicating no significant radiological health risks. Because the values were constantly below the MDC, it was not possible to establish a clear relationship between chemical composition and radiometric properties of the particles. Nevertheless, the continuous monitoring of PM highlighted the presence of indoor sources within the sanctuary, which did not exert any measurable impact on the radiological properties of the particles.

The assessment of radiological properties of indoor PM remains a seldom-explored area, and these results provide an important starting point and case study for future research. Overall, the investigations conducted, covering radiometric exposure, heavy metals, and other chemical components of PM, indicate generally good air quality conditions within the sanctuary. Future research should incorporate an assessment of radon concentrations to complete the framework of air quality and radiological evaluation within the sanctuary or in other indoor environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F.; methodology, A.B., A.S., F.C.; software, A.S., A.M., C.L.; validation, P.F., V.C. and V.V.; formal analysis, A.B., M.B. and F.C.; investigation, A.B., C.A.L., M.B., V.C., F.C.; resources, P.F., V.V. and C.L.; data curation, A.B., F.C., A.M. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B. and F.C.; writing—review and editing, A.B., F.C., P.F. and V.C.; supervision, P.F., V.V. and C.L.; project administration, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at 10.5281/zenodo.17816733.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Carlo Mariani and to the clergy and staff of the Sanctuary of the Blessed Virgin of Miracles in Saronno (VA) for kindly allowing us to carry out this study within the sanctuary.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Antonio Spagnuolo is a founding partner of Energreenup S.r.l. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Portela, N.B.; Teixeira, E.C.; Agudelo-Castañeda, D.M.; Civeira, M.d.S.; Silva, L.F.O.; Vigo, A.; Kumar, P. Indoor-Outdoor Relationships of Airborne Nanoparticles, BC and VOCs at Rural and Urban Preschools. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, G.; Ciuchini, C.; Pasini, A.; Tappa, R. Monitoring of Ambient BTX at Monterotondo (Rome) and Indoor-Outdoor Evaluation in School and Domestic Sites. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, J.; Paciência, I.; De Oliveira Fernandes, E. Levels and Indoor-Outdoor Relationships of Size-Specific Particulate Matter in Naturally Ventilated Portuguese Schools. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health—Part A Curr. Issues 2012, 75, 1423–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensirion. Total Volatile Organic Compounds (TVOC) and Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)SGP30 TVOC and CO2eq Sensor. Version 2.0. November 2019. Available online: https://www.sensirion.com/ (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Brimblecombe, P.; Blades, N.; Camuffo, D.; Sturaro, G.; Valentino, A.; Gysels, K.; Van Grieken, R.; Busse, H.J.; Kim, O.; Ulrych, U.; et al. The Indoor Environment of a Modern Museum Building, The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, UK. Indoor Air 1999, 9, 146–164, ISSN 0905-6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camuffo, D.; Brimblecombe, P.; Van Grieken, R.; Busse, H.-J.; Sturaro, G.; Valentino, A.; Bernardi, A.; Blades, N.; Shooter, D.; De Bock, L.; et al. Indoor Air Quality at the Correr Museum, Venice, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 1999, 236, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martellini, T.; Berlangieri, C.; Dei, L.; Carretti, E.; Santini, S.; Barone, A.; Cincinelli, A. Indoor Levels of Volatile Organic Compounds at Florentine Museum Environments in Italy. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 900–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Bovè, J.; Strlic, M. Fine particulate matter in indoor cultural heritage: A literature review. Herit. Sci. 2013, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupa, G.; Rapsomanikis, S. Air Pollutant Emission Rates and Concentrations in Medieval Churches. J. Atmos. Chem. 2008, 60, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wysocka, M. Analysis of Indoor Air Quality in a Naturally Ventilated Church. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, H.C.; Jones, T.; Bérubé, K. Combustion Particles Emitted during Church Services: Implications for Human Respiratory Health. Environ. Int. 2012, 40, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergomi, A.; Carrara, E.; Festa, E.; Colombi, C.; Cuccia, E.; Biffi, B.; Comite, V.; Fermo, P. Optimization and Application of Analytical Assays for the Determination of Oxidative Potential of Outdoor and Indoor Particulate Matter. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.Y.; Kim, G.D. Particulate Matter-Induced Emerging Health Effects Associated with Oxidative Stress and Inflammation. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Aizezi, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Deng, L.; Liu, Y. Single-Particle Decoding of Aerosol Pollutants Size-Composition Relationships: An Interpretable XGBoost-SHAP Framework with DTEWD-Enhanced SPAMS Analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 500, 140397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, R.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O.; Stafoggia, M.; Andersen, Z.J.; Weinmayr, G.; Hoffmann, B.; Wolf, K.; Samoli, E.; Fischer, P.; Nieuwenhuijsen, M.; et al. Effects of Long-Term Exposure to Air Pollution on Natural-Cause Mortality: An Analysis of 22 European Cohorts within the Multicentre ESCAPE Project. Lancet 2014, 383, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, A.L.; Tennant, R.K.; Stewart, A.G.; Gosden, C.; Worsley, A.T.; Jones, R.; Love, J. The Evolution of Atmospheric Particulate Matter in an Urban Landscape since the Industrial Revolution. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee, Directive 2013/59/Euratom. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2013/59/oj/eng (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Matthaios, V.N.; Liu, M.; Li, L.; Kang, C.M.; Vieira, C.L.Z.; Gold, D.R.; Koutrakis, P. Sources of Indoor PM2.5 Gross α and β Activities Measured in 340 Homes. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 111114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.Y.; Kang, C.M.; Liu, M.; Koutrakis, P. PM2.5 Sources Affecting Particle Radioactivity in Boston, Massachusetts. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 259, 118455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Koutrakis, P.; Li, L.; Coull, B.A.; Schwartz, J.; Kosheleva, A.; Zanobetti, A. Synergistic Effects of Particle Radioactivity (Gross β Activity) and Particulate Matter ≤ 2.5 Μm Aerodynamic Diameter on Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, A.J.; Nyhan, M.M.; Bind, M.A.; Vokonas, P.; Coull, B.A.; Schwartz, J.; Koutrakis, P. The Role of Ambient Particle Radioactivity in Inflammation and Endothelial Function in an Elderly Cohort. Epidemiology 2020, 31, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.; Martins, M.; Liu, M.; Koutrakis, P. Measurement of the Gross Alpha Activity of the Fine Fractions of Road Dust and Near-Roadway Ambient Particle Matter. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2021, 71, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergomi, A.; Comite, V.; Guglielmi, V.; Borelli, M.; Lombardi, C.A.; Bonomi, R.; Pironti, C.; Ricciardi, M.; Proto, A.; Mariani, C.; et al. Preliminary Air Quality and Microclimatic Conditions Study in the Santuario Della Beata Vergine Dei Miracoli in Saronno (VA). Molecules 2023, 28, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANPA Agenzia Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente. Guida Tecnica Sulle Misure di Radioattività Ambientali. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/pubblicazioni/AGFTGTE0002_v2.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, Soils, and Oils; Method 3051A; EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2015-12/documents/3051a.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Italian Higher Institute for Environmental Protection and Research (ISPRA). Manual of the RESORAD Network; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2016. Available online: https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/files/sicurezza-nucleare-radioattivita/ManualeReteRESORAD_rev2.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Caridi, F.; Marguccio, S.; Durante, G.; Trozzo, R.; Fullone, F.; Belvedere, A.; D’Agostino, M.; Belmusto, G. Natural Radioactivity Measurements and Dosimetric Evaluations in Soil Samples with a High Content of NORM. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2017, 132, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELSE Nuclear. ELSE ALBA/LLAB User Manual; ELSE Nuclear: Busto Arsizio, Italy, 2000; Available online: https://www.elsenuclear.com (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Caridi, F.; Testagrossa, B.; Acri, G. Elemental Composition and Natural Radioactivity of Refractory Materials. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortec. GammaVision® 8; Ortec: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ortec-online.com/-/media/ametekortec/manuals/a/a66-mnl.pdf?la=en&revision=dd63bfec-f5cd-4579-8201-e81a52f7fb78 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Caridi, F.; Messina, M.; Belvedere, A.; D’Agostino, M.; Marguccio, S.; Settineri, L.; Belmusto, G. Food Salt Characterization in Terms of Radioactivity and Metals Contamination. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCREDIA. Available online: https://www.accredia.it/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Italy. Legislative Decree No. 101 of 2020. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2020/08/12/20G00121/sg (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Perrino, C.; Tofful, L.; Canepari, C. Chemical characterization of indoor and outdoor fine particulate matter in an occupied apartment in Rome, Italy. Indoor Air 2015, 26, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, D.; Pinho, I.; Cerqueira, M.; Nunes, T.; Pio, C. Indoor and Outdoor Suspended Particulate Matter and Associated Carbonaceous Species at Residential Homes in Northwestern Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 473–474, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, M.; Cuccia, E.; Colombi, C. Campagna di Approfondimento Della Composizione Chimica del PM10 Nel Supersito di Varese; ARPA Lombardia: Milan, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Santo, U.; Algieri, A.; Carli, P.; Colombi, C.; Corbella, L.; Cuccia, E.; Martini, D.; Gianelle, V.; Siliprandi, G. Caratterizzazione Del PM10 in Alcune Città Lombarde. In Proceedings of the PM2020 Conference, Lecce, Italy, 14–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2008/50/EC of 21 May 2008 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 152, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament and Council of the European Union. Directive 2004/107/EC of 15 December 2004 Relating to Arsenic, Cadmium, Mercury, Nickel and Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Ambient Air. Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, 23, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003422-8. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Volume 100F: Chemical Agents and Related Occupations; IARC: Lyon, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manousakas, M.; Furger, M.; Daellenbach, K.R.; Canonaco, F.; Chen, G.; Tobler, A.; Rai, P.; Qi, L.; Tremper, A.H.; Green, D.; et al. Source Identification of the Elemental Fraction of Particulate Matter Using Size Segregated, Highly Time-Resolved Data and an Optimized Source Apportionment Approach. Atmos. Environ. X 2022, 14, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of California, Resources Board. Initial Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking—Proposed Identification of Nickel as A Toxic Air Contaminant; Technical Support Document, Part A; State of California, Air Resources Board: Sacramento, CA, USA, 1991.

- Liang, N.; Li, Z.; Sun, J.; Fu, N.; Zhong, G.; Lin, X.; Mao, K.; Zhang, P.; Chang, Z.; Yang, D.; et al. A Systematic Review on Heavy Metals in Indoor Air: Occurrence, Spatial Variation, and Health Risk. Build. Environ. 2025, 269, 112357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISIN. Radioactivity Information System; ISIN: Rome, Italy, 2025; Available online: https://sinrad.isinucleare.it/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Kang, C.M.; Liu, M.; Garshick, E.; Koutrakis, P. Indoor Particle Alpha Radioactivity Origins in Occupied Homes. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2020, 20, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S.; Krupińska, B.; Worobiec, A.; Cevik, U.; Taskın, H.; Van Grieken, R.; Samek, L.; Wiłkojć, E. Gross Alpha and Beta Activities of Airborne Particulate Samples from Wawel Royal Castle Museum in Cracow, Poland. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2013, 295, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.