Abstract

Aim: to investigate the criteria to define implant–prosthodontic therapy failure for dentists in Croatia. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study using an online questionnaire among dentists in Croatia. The questionnaire consisted of demographic information and sections about experience and criteria for defining outcomes in implant–prosthodontic therapy to assess dentists’ perspectives towards implant failures, failure of prosthodontic supra-structures, potential complications and follow-up time. Descriptive statistics were used and differences were assessed using Chi-squared statistics. Results: Overall, 198 dentists completed the questionnaire, most of whom were general practitioners (81.8%), and mostly females (68.2%). 63.1% reported having worked with implants in their everyday practice. Most dentists (71.2%) have encountered implant failure, and more than half (57.1%) experienced a failed prosthodontic supra-structure. However, their definitions of implant failure or success differed significantly. Criteria for failure from 1986 were considered among 47% dentists, while 53% considered the implant to be successful if it remained in situ over a follow-up period. The three postoperative complications which patients should be warned about included pain, swelling and periimplantitis. Follow-up at six months and at five years were both chosen as appropriate by approximately the same number of dentists. Conclusions: Criteria to define implant failure differed between general practitioners and specialists, while definitions of implant success correlated with experience. The variability observed underscores the need for standardized education and unified assessment criteria to improve clinical consistency and communication.

1. Introduction

Dental implants represent a contemporary, reliable, and widely adopted solution for partial or total edentulism [1,2,3,4], providing substantial benefits in function, esthetics and patients’ quality of life [3]. Despite reported success rates of up to 95% over a 10-year follow-up period [5,6], implant–prosthodontic therapy remains susceptible to biological, mechanical, and esthetic complications, which can lead to treatment failure [7,8].

Biological complications refer to conditions affecting peri-implant hard and soft tissues that compromise long-term implant stability [9,10], whereas prosthodontic complications involve mechanical problems such as ceramic chipping, loss of retention, or screw loosening [1,11,12]. Implant failure typically arises from multiple contributing factors [8,13], including impaired osseointegration, underlying systemic diseases, or patient-related habits such as poor oral hygiene and smoking [10]. The classification of implant failures generally distinguishes early failure, which occurs before functional loading due to incomplete osseointegration [1,14,15], and late failure, resulting from bone loss or inflammation-induced peri-implant complications after loading, typically within 6–36 months [13,16,17,18,19,20].

Historically, criteria for evaluating dental implant failure have included implant and prosthesis stability, peri-implant radiolucency, bone loss greater than 0.2 mm annually following the first year, and persistent pain or paresthesia [21,22,23,24,25]. However, despite decades of research and numerous clinical trials, no universally accepted definition or diagnostic framework for implant failure exists [26,27]. Clinicians often rely on subjective individual interpretation, with implant instability and loss of osseointegration among the most cited clinical assessment indicators [5].

A recent study identified 17 distinct sets of criteria used to define implant failure across clinical trials, revealing substantial inconsistency in defining implant success, survival, prosthodontic supra-structure failure, and complication outcomes [27]. Furthermore, most studies assess outcomes at only one year, despite the recommended five-year follow-up, potentially leading to overestimated success rates [1,28,29]. In clinical practice, short follow-up intervals and infrequent recalls can lead to unrecognized biological and mechanical complications that eventually result in implant loss [18].

This inconsistency across research frameworks not only limits comparability and meta-analytic synthesis but also hinders consistent clinical communication and evidence-based decision-making [27]. Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the attitudes and experiences of Croatian dentists regarding the definition of failure in implant–prosthodontic therapy. Specifically, it investigates the clinical and follow-up criteria dentists use to assess implant and prosthodontic supra-structure failure and explores how the definitions of these outcomes vary based on dentists’ experience, education, workplace, and clinical specialty.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study was conducted from April to December 2024. The self-structured questionnaire was developed based on a review of relevant literature and input from implantology experts, followed by pilot testing to ensure clarity and validity. Recruitment was conducted via email invitations sent to dentists listed in the Croatian national professional registries. The study included both specialists and general practitioners. Participation was voluntary, with electronic informed consent obtained electronically prior to questionnaire completion.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, University of Split (Class: 029-01/ 24-02/0001, Reg. no.: 2181-198-03-04-24-0038). The study adhered to the principles of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR); all collected data, including the identities of the respondents, are entirely anonymous. The study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines to ensure transparency and methodological rigor in observational research reporting [30].

2.2. Sampling

A hybrid sampling approach combining convenience and snowball sampling was employed to recruit Croatian dentists. Invitations, sent via email and social media from the authors’ professional contacts, explicitly requested recipients to share the survey link with colleagues actively engaged in implant–prosthodontic therapy in routine clinical practice. This aimed to enhance sample diversity and target relevance.

The target sample size was estimated based on official data from the Croatian Dental Chamber, which lists approximately 4000 registered dentists practicing in Croatia (accessed 10 March 2025, from https://www.hkdm.hr). Using an online sample size calculator (https://epitools.ausvet.com.au; URL accessed on 10 March 2025), the minimal required sample size was determined to be 216 dentists to achieve a 95% confidence level with a 5% margin of error and an 80% power.

2.3. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed and administered via Google Forms and consisted of two main sections, totaling 20 mandatory questions, estimated to take approximately 10 minutes to complete. The first section (Q1–Q7) collected participants’ demographic and professional background information, including gender, age, years of clinical experience, educational level, specific education in implant–prosthodontics, and independent clinical work with dental implants.

The second section (Q8–Q14) included questions about dentists’ experiences with dental implants, and the third section (Q15–Q20) focused on the criteria dentists use to define failure in implant–prosthodontic therapy. This part was primarily based on the outcomes and the defining criteria extracted from previously published clinical studies as outlined by Vardić et al. [27]. Therefore, the proposed multiple-choice items included criteria for implant failure, failure of the implant supra-structure, definitions of implant therapy success, and the timing to assess success of implant therapy, as well as possible postoperative complications, based on the exact criteria reported in the literature. Dentists responded to multiple-choice questions, each answer representing a distinct set of clinical criteria relevant to defining implant failure, prosthodontic supra-structure failure, implant success, complications, and dentists’ personal clinical experiences with implant–prosthodontic failures. Single answers were allowed for all questions except the final one regarding complications, which permitted multiple answers.

To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was pilot-tested by six implant-trained dentists at the University Hospital of Split and the Outpatient Dental Clinic in Split, Croatia. Feedback from this pilot led to refinements in wording and response options, but pilot data were excluded from the final analysis.

The questionnaire’s introduction included the study aims and information emphasizing voluntary participation, data confidentiality, and anonymity in accordance with GDPR standards. The full questionnaire is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Data Analysis

Responses collected through the online questionnaire were automatically imported into Microsoft Excel (Office 365, 2024, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and appropriately coded for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, with results presented as absolute numbers and percentages. The Chi-square test was employed to evaluate potential associations between categorical variables, specifically to identify differences in dentists’ attitudes based on years of clinical experience, specialty, level of education, workplace, and personal experience with implant treatment. Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistical software, version 26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The significance level was set at p < 0.05 (two-sided).

3. Results

A total of 198 Croatian dentists completed the questionnaire. The majority were general practitioners (81.8%), and most were female (68.2%). As for the education level, the large majority had a graduate university degree (84.3%), with only a minority with a PhD (9.6%) or a master’s degree (6.1%). More than half of the participating dentists had ten or more years of work experience (62.2%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Dentists’ demographic characteristics (n = 198).

When asked about individual experiences with implant–prosthodontic therapy, 75.7% of dentists reported having performed it in their everyday clinic practice. There was a wide diversity in the frequency of performing implant–prosthodontic therapy, with around a third of all dentists (28.8%) reporting either several cases per year or more than 10 cases per month. Only 22.2% perform the implantation procedure themselves. Most dentists (71.2%) have encountered implant failure, of which 63.1% have dealt with early implant failure, i.e., osseointegration failure, and 59.6% have encountered late implant failure after prosthodontic and occlusal loading (Table 2).

Table 2.

Dentists’ experiences with implant–prosthodontic therapy (n = 198).

The participating dentists showed considerable variability in their opinions on what constitutes a failed dental implant. Nearly half (47%) identified implant failure by a combination of clinical signs, including implant mobility, pain, peri-implantitis with suppuration, and peri-implant radiolucency accompanied by bone resorption. However, only 5% considered implant mobility alone as an indicator of failure. Other dentists regarded failure as occurring only when the implant was lost (12.6%), mobile with infection (13.1%), or mobile with marginal bone loss (13.1%).

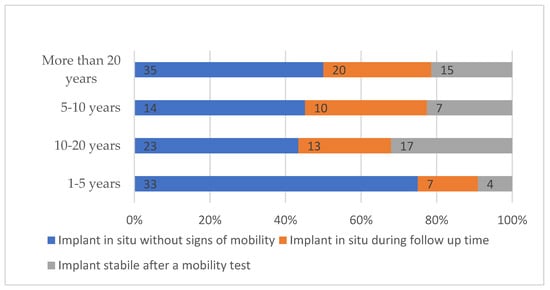

Regarding treatment success, 53% of participants defined implant therapy as successful when the implant remained in situ without mobility. Others emphasized criteria such as the implant being in situ during the follow-up period (25.3%) or demonstrating stability after a mobility test (21.7%). There was also notable inconsistency in responses regarding optimal follow-up duration, with similar proportions endorsing either a 6-month (26.8%) or a 5-year (28.3%) follow-up period for clinical evaluation of implant–prosthodontic therapy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Criteria to define outcomes of implant–prosthodontic therapy (n = 198).

More than half of participants (57.1%) reported encounters with failed prosthodontic supra-structure (Table 2). Among them, 17.6% considered soft tissue hypertrophy a sign of supra-structure failure, while 13.1% identified a loose screw as indicative of failure. Others defined prosthodontic failure by supra-structure mobility (27.3%), fractures or cracks in both fixed and mobile prostheses (25.8%), or the need for readjustment or replacement of the supra-structure (26.3%) (Table 3).

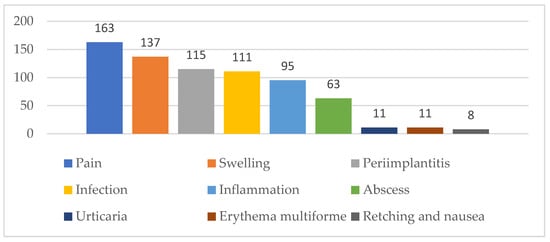

Dentists’ views on potential complications following implant placement, which should be communicated to patients, also varied significantly. The majority identified pain (82.3%) and swelling (69.2%) as the most common postoperative complications. Approximately half of them recognised infection (56.1%), inflammation (48%), and peri-implantitis (58.1%) as complications warranting patient awareness. Less frequently, a small number indicated that patients should be warned about complications, such as nausea (reported by 8 dentists), and hypersensitivity reactions, including urticaria or erythema multiforme (reported by 11 dentists) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dentists’ attitudes on postoperative complications that patients should be informed about.

A statistically significant difference was found between specialists and general practitioners in their definitions of implant failure criteria (χ2 = 14.659; df = 6; p = 0.023; Fisher’s exact p = 0.018). General practitioners most frequently defined implant failure as mobility accompanied by pain, peri-implantitis with suppuration, and radiolucency with bone resorption (48.8%), whereas specialists showed a more even distribution across multiple combined clinical and radiological indicators (Table 4). No statistically significant differences were found between groups according to years of clinical experience (χ2 = 15.854; df = 18; p = 0.603) or independent implant placement activity (χ2 = 6.147; df = 6; p = 0.407).

Table 4.

Distribution of dentists’ criteria for defining implant failure by specialization, presented as counts and percentages.

Building on these findings, further analysis revealed a significant association between years of clinical experience and the definition of implant success (χ2 = 13.717; df = 6; p = 0.033). Dentists with fewer years of experience (1–5 years) most frequently selected the criterion of an implant remaining in situ without signs of mobility. In contrast, other experience groups showed a more varied distribution of choices. This indicates diversity in definitions of implant success across clinical experience levels (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Dentists’ definitions of implant success stratified by years of clinical experience.

In contrast, no statistically significant differences were observed in definitions of implant success according to specialization (χ2 = 1.522; df = 2; p = 0.467) or independent implant placement activity (χ2 = 1.605; df = 2; p = 0.448).

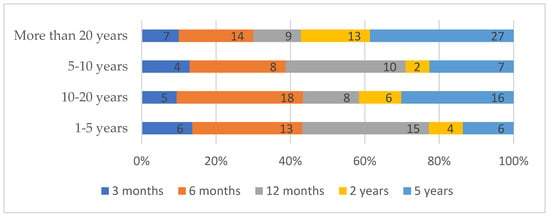

Follow-up time for clinical evaluation of implant–prosthodontic therapy varied significantly by dentists’ years of clinical experience (χ2 = 21.161; df = 12; p = 0.048). The most frequently selected interval was 5 years post-implantation (56 respondents), followed by 6 months (53 respondents) and 12 months (42 respondents). Dentists with more than 20 years of experience favored the 5-year period (27 out of 70, 38.6%), while those with 10–20 years and 1–5 years of experience showed more diverse preferences, including 6 months (18 out of 53, 34.0% and 13 out of 44, 29.5%, respectively) and 12 months (8 out of 53, 15.1% and 15 out of 44, 34.1%, respectively). The 5–10 years group showed no single dominant period, with similar proportions across 6 months (25.8%), 12 months (32.3%), and 5 years (22.6%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time period considered necessary for implant success evaluation by years of clinical experience.

No statistically significant differences were found in the preferred evaluation period regarding specialization (χ2 = 4.177; df = 4; p = 0.383), or independent implant placement (χ2 = 8.834; df = 4; p = 0.065).

The criteria for defining failure of prosthodontic supra-structures did not differ significantly by years of clinical experience (χ2 = 9.462; df = 12; p = 0.663). Similarly, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups defined by specialization (χ2 = 2.562; df = 4; p = 0.634). However, when comparing respondents who perform implant placement versus those who do not, a statistically significant difference emerged (χ2 = 10.682; df = 4; p = 0.030; Fisher’s exact p = 0.031), indicating that clinical activity in implant placement may influence how dentists define criteria of prosthodontic supra-structures (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of dentists’ criteria for defining failure of prosthodontic supra-structure by implant placement, presented as counts and percentages.

4. Discussion

This study found substantial differences in dentists’ perspectives regarding various aspects of implant–prosthodontic therapy success criteria, including definitions of implant failure, the optimal follow-up time, failure of prosthodontic supra-structure and the expected postoperative complications that dentists should warn their patients about.

Almost three-quarters of dentists in our study have encountered implant failure in their daily clinical practice, whether early or late. Yet, they have very different perspectives on what constitutes implant failure. Our results corroborate previous methodological evidence revealing a lack of consensus in defining dental implant failure [27]. In line with this, our findings indicate that dentists use different definitions of implant failure. We found differences between specialists and general practitioners in how they perceived implant failure criteria, suggesting that professional background and training may influence clinicians’ interpretation of implant outcomes. In contrast, clinical experience did not appear to affect these perceptions. Nevertheless, nearly half of the dentists aligned with the original Albrektsson definition, by which an implant is deemed failed in the presence of implant mobility, pain, peri-implantitis with suppuration, peri-implant radiolucency, or vertical bone resorption exceeding 0.2 mm annually after the first year of implantation [21,31]. This partial agreement suggests that the Albrektsson criteria continue to serve as a reference point [21]. However, substantial variation in clinical interpretation and application of the assessment criteria underscores the need for standardized definitions to ensure consistency in clinical decision-making.

Other dentists in our study applied less comprehensive definitions, with some considering implant failure to be equivalent to implant loss. This variability aligns with findings by Saad et al., who reported that one-third of participants perceived bone loss as the primary reason for implant failure, while one-quarter attributed it to infection [32]. Their conclusions, emphasizing the need for better systematization and standardization of implant therapy complications and outcomes, echo the implications of our study. Establishing consistent and clinically meaningful criteria for defining implant failure remains crucial for enhancing research comparability and clear clinical communication.

A notable finding of our study is that for one-quarter of dentists, implant therapy is considered successful if the implant remains in situ during the follow-up period, irrespective of other biological or prosthodontic parameters. This view reflects a simplified assessment of implant success, contrasting with the more comprehensive definition proposed by Albrektsson et al. [21], without clear information on parameters like pain, mobility, peri-implant radiolucency, or bone loss. The perception of implant success, however, was related to years of experience, indicating that accumulated clinical exposure may shape practitioners’ understanding of what constitutes successful treatment. Such a discrepancy highlights the persistent gap between clinical practice perceptions and the literature.

Supra-structure failure was widespread—more than half of the dentists have seen it in their clinical practice. However, their views on the criteria for supra-structure failure differed significantly. The criteria used to define failure of prosthodontic supra-structures were largely consistent across experience levels and specializations, though differences between dentists who perform implant placement and those who do not highlight the influence of hands-on surgical involvement on clinical judgment. Dentists’ standpoints on supra-structure seem to be much more conservative than the ones regarding implant failure: almost a quarter consider simple screw loosening or soft tissue hypertrophy as failure of the prosthodontic supra-structure.

Albrektsson et al. also proposed a standardized follow-up period of five years for evaluating implant success, a recommendation later reaffirmed by Sailer et al. and Papaspyridakos et al. [12,21,33]. Interestingly, nearly the same proportion of our participants considered either 6 months or 5 years an adequate follow-up period. More experienced dentists tended to adopt a five-year follow-up period, possibly reflecting greater emphasis on long-term evaluation and outcome stability. In contrast, less experienced dentists showed more varied preferences. In contrast, Vardić et al. reported that only one out of 117 studies assessing implant failure applied a five-year follow-up, while the majority limited their assessments to 12 months [27].

The study also found that the most common postoperative complications patients should be made aware of include pain and swelling. These findings are in accordance with a 2020 study by Fu et al., which found that pain was the most common postoperative complication of implant placement [9]. However, the third most common answer in our research was periimplantitis, which almost two-thirds of our participants deemed necessary to warn patients about as a possible complication. Peri-implantitis is a multifactorial pathological condition that occurs in the tissues surrounding the implant and is characterized by inflammation in the peri-implant mucosa with progressive loss of supporting bone and is a long-term risk factor for implant failure [10]. As such, it is an outcome that patients should consistently be warned about, but cannot be considered a postoperative complication, as reported by the dentists in this study. Peri-implantitis, along with other complications, is listed in this questionnaire as a dental-prosthodontic complication reported in the literature. Considering peri-implantitis as complication may be due to a misunderstanding among our dentists, who may have played it safe to emphasize the importance of warning patients about it. On the other hand, Kasbour et al. found that clinicians are sometimes reluctant to provide information on the longevity of implant–prosthodontic solutions, suggesting that dentists sometimes avoid communicating possible complications to avoid unwanted patient reactions [34].

Most of our participants were general practitioners, what may have influenced the results, as their formal education on implant dentistry is likely limited. This could explain the observed heterogeneity in perceptions regarding implant failure criteria. Similarly, Jayachandan et al. reported that undergraduate education in implant–prosthodontic therapy in England remains insufficient [35], highlighting a gap in current training. Furthermore, Chrcanovic et al. found that the operator’s experience and technique can significantly affect outcomes of implant therapy [36].

Overall, these findings suggest the need for more structured and standardized education in implant dentistry to ensure a consistent understanding and informed clinical decision-making among practitioners.

This study has several important limitations. First, the use of a hybrid non-probabilistic sampling strategy (convenience and snowball sampling) and reliance on voluntary completion of the online questionnaire may have introduced selection bias, favouring dentists who are more engaged in implant dentistry or more active within professional networks. As a result, the sample cannot be considered representative of all Croatian dentists, and the generalizability of the findings is limited. However, the observed sociodemographic and experiential profile, with a predominance of general practitioners regularly involved in implant–prosthodontic therapy, is consistent with current clinical practice patterns and thus aligns with the predefined target population for this study. Second, eligibility and clinical exposure were assessed through self-report, and external verification was not feasible in the anonymous online format, which may have led to some misclassification, particularly for experience-dependent outcomes. Finally, the cross-sectional design and self-reported data are susceptible to recall and social desirability bias. For these reasons, the results should be interpreted with appropriate caution and regarded as exploratory, providing insight into prevailing patterns and educational needs rather than definitive population estimates.

Nonetheless, despite the limitations, this study’s findings align with available evidence on the heterogeneity of opinions and the lack of clear definitions of what constitutes implant failure, the appropriate follow-up time, and the distinction between a postoperative complication and risk for implant failure. This type of study has not, to the best of our knowledge, been conducted to date. As such, this study provides valuable insights into local knowledge and needs regarding additional education and the non-availability of high-quality clinical practice guidelines. However, it may also reflect the current state of assessment of dental implant failure in clinical practice, as understanding the symptoms affects communication and may influence subsequent treatment steps. Seeing larger-scale results or perspectives, especially from implant–prosthodontic experts, could help to standardize implant-related study outcomes, which could then lead to the creation of guidelines applicable in daily practice.

Future studies can address this study’s limitations by using a larger, more representative sample, incorporating multivariable analyses to further elucidate these relationships. Since our sampling method involved participants sharing the questionnaire through their private and professional connections, new studies should aim to obtain a sample that covers most aspects of the population (dentists), thereby yielding more objective results.

5. Conclusions

Criteria to assess implant failure differed between general practitioners and specialists, independent of experience. Definitions of implant success and preferred follow-up periods varied by clinical experience, with dentists having more than 20 years of experience more frequently selecting longer evaluation intervals such as five years. The substantial variability observed in this study highlights the need for standardized educational frameworks and universally accepted definitions of clinical success and failure to improve consistency in clinical practice, communication, and research comparability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010102/s1, File S1: Criteria for assessing the failure of dental implant-prosthodontic treatment: the questionnaire.

Author Contributions

Study design: M.K., J.V., E.B. and T.P.P.; Data collection and analysis: M.K., A.P., J.V., E.B., A.T. and T.P.P.; Writing the first draft of the manuscript: M.K., A.P., M.A.P. and T.P.P.; Critical revision of the manuscript: M.K., A.P., J.V. and T.P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the of School of Medicine, University of Split, Split, Croatia (Class: 029-01/ 24-02/0001, Reg. no.: 2181-198-03-04-24-0038).

Data Availability Statement

Raw data derived from the questionnaire are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study were part of the graduation thesis of Eva Bilandžić at the University of Split School of Medicine Dental Medicine Study. The graduation thesis was written in Croatian.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- AlRowis, R.; Albelaihi, F.; Alquraini, H.; Almojel, S.; Alsudais, A.; Alaqeely, R. Factors Affecting Dental Implant Failure: A Retrospective Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemtov-Yona, K.; Rittel, D. An Overview of the Mechanical Integrity of Dental Implants. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 547384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.S.; Jansen, J.A. The development and future of dental implants. Dent. Mater. J. 2020, 39, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, H.L.; Ionfrida, J.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Walter, C. The Effects of Smoking on Dental Implant Failure: A Current Literature Update. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nawas, B.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Morbach, T.; Ladwein, C.; Wegener, J.; Wagner, W. Ten-Year Retrospective Follow-Up Study of the TiOblastTM Dental Implant. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Thoma, D.; Jung, R.; Zwahlen, M.; Zembic, A. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of implant-supported fixed dental prostheses after a mean observation period of at least 5 years. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2012, 23, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resnik, R.R.; Misch, C.E. Misch’s Contemporary Implant Dentistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Momand, P.; Naimi-Akbar, A.; Hultin, M.; Lund, B.; Götrick, B. Is routine antibiotic prophylaxis warranted in dental implant surgery to prevent early implant failure?—A systematic review. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-H.; Wang, H.-L. Breaking the wave of peri-implantitis. Periodontology 2000 2020, 84, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglundh, T.; Persson, L.; Klinge, B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2002, 29, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, K.; Derks, J.; Håkansson, J.; Wennström, J.L.; Thorén, M.M.; Petzold, M.; Berglundh, T. Technical complications following implant-supported restorative therapy performed in Sweden. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailer, I.; Karasan, D.; Todorovic, A.; Ligoutsikou, M.; Pjetursson, B.E. Prosthetic failures in dental implant therapy. Periodontology 2000 2022, 88, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Hirsch, J.; Lekholm, U.; Thomsen, P. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants, (I). Success criteria and epidemiology. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 106, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahapur, S.G.; Patil, K.; Manhas, S.; Datta, N.; Jadhav, P.; Gupta, S. Predictive Factors of Dental Implant Failure: A Retrospective Study Using Decision Tree Regression. Cureus 2024, 16, e75192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinhas, A.S.; Aroso, C.; Salazar, F.; López-Jarana, P.; Ríos-Santos, J.V.; Herrero-Climent, M. Review of the Mechanical Behavior of Different Implant–Abutment Connections. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M.I.; Daud, R.; Ibrahim, I.; Mat, F.; Mansor, N.N. Biomechanical Overloading Factors Influencing the Failure of Dental Implants: A Review. In Structural Integrity Cases in Mechanical and Civil Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, Y.; Oubaid, S.; Mardinger, O.; Chaushu, G.; Nissan, J. Characteristics of Early Versus Late Implant Failure: A Retrospective Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 2649–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochar, S.P.; Reche, A.; Paul, P. The Etiology and Management of Dental Implant Failure: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e30455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohajerani, H.; Roozbayani, R.; Taherian, S.; Tabrizi, R. The Risk Factors in Early Failure of Dental Implants: A Retrospective Study. J. Dent. 2017, 18, 298–303. [Google Scholar]

- Staedt, H.; Rossa, M.; Lehmann, K.M.; Al-Nawas, B.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Heimes, D. Potential risk factors for early and late dental implant failure: A retrospective clinical study on 9080 implants. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2020, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrektsson, T.; Zarb, G.; Worthington, P.; Eriksson, A.R. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: A review and proposed criteria of success. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1986, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Misch, C.E.; Perel, M.L.; Wang, H.-L.; Sammartino, G.; Galindo-Moreno, P.; Trisi, P.; Steigmann, M.; Rebaudi, A.; Palti, A.; Pikos, M.A.; et al. Implant Success, Survival, and Failure: The International Congress of Oral Implantologists (ICOI) Pisa Consensus Conference. Implant. Dent. 2008, 17, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annibali, S.; Bignozzi, I.; La Monaca, G.; Cristalli, M.P. Usefulness of the Aesthetic Result as a Success Criterion for Implant Therapy: A Review. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2012, 14, 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, D.; Mericske-Stern, R.; Bernard, J.P.; Behneke, A.; Behneke, N.; Hirt, H.P.; Belser, U.C.; Lang, N.P. Long-term evaluation of non-submerged ITI implants. Part 1: 8-year life table analysis of a prospective multi-center study with 2359 implants. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 1997, 8, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeboom, J.A.; Frenken, J.W.; Dubois, L.; Frank, M.; Abbink, I.; Kroon, F.H. Immediate Loading Versus Immediate Provisionalization of Maxillary Single-Tooth Replacements: A Prospective Randomized Study With BioComp Implants. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Takeuchi, J.; Asai, T.; Murata, M.; Umeda, M.; Komori, T. Analysis of 472 Brånemark system TiUnite implants:a retrospective study. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2010, 55, E73–E81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vardić, A.; Puljak, L.; Galić, T.; Viskić, J.; Kuliš, E.; Peričić, T.P. Heterogeneity of outcomes in randomized controlled trials on implant prosthodontic therapy is hindering comparative effectiveness research: Meta-research study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L. Dealing with dental implant failures. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2008, 16, 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Loutan, L.; Garavaglia, G.; Hashim, D. Removal of osseointegrated dental implants: A systematic review of explantation techniques. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007, 370, 1453–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, K.; Sivaraj, S.; Thangaswamy, V. Evaluation of implant success: A review of past and present concepts. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2013, 5, S117–S119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, I.; Salem, S. Knowledge, awareness, and perception of dental students, interns, and freshly graduated dentists regarding dental implant complications in Saudi Arabia: A web-based anonymous survey. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Chen, C.-J.; Singh, M.; Weber, H.-P.; Gallucci, G.O. Success Criteria in Implant Dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashbour, W.A.; Rousseau, N.S.; Thomason, J.M.; Ellis, J.S. Provision of information to patients on dental implant treatment: Clinicians’ perspectives on the current approaches and future strategies. J. Dent. 2018, 76, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayachandran, S.; Bhandal, B.S.; Hill, K.B.; Walmsley, A.D. Maintaining dental implants--do general dental practitioners have the necessary knowledge? Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Kisch, J.; Albrektsson, T.; Wennerberg, A. Impact of Different Surgeons on Dental Implant Failure. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.