Abstract

(1) Background: Handball is conceptualized as a complex dynamic system characterized by emergent behaviors, non-linearity, attractors, and self-organization, influenced by players’ interactions, environmental conditions, and tactical elements. This perspective emphasizes the importance of communication, adaptive strategies, and modern teaching methods like Non-linear Pedagogy for improving technical-tactical behaviors, advocating for a multidisciplinary approach to deepen its understanding. Thus, this narrative review aims to explore how modern theories and approaches can be integrated to provide a deeper understanding of handball’s complexity from a broad and multidisciplinary perspective. (2) Methods: A narrative review approach was employed to integrate key concepts such as chaos theory, self-organization, and non-linear pedagogy as they apply to the game’s technical-tactical dynamics. The methodology involved a comprehensive literature review to identify how emergent perceptual and social interactions influence collective performance. (3) Results: Findings indicate that team performance is not solely dependent on individual skills but on their capacity for synchronization, adaptation, and self-organization in response to competitive demands. Communication and internal cohesion emerged as critical factors for adjustment and autonomous decision-making, framed within Luhmann’s social systems theory. (4) Conclusions: The conclusions suggest that training methodologies should incorporate non-linear approaches that promote self-organization, adaptability, and player autonomy. This multidisciplinary perspective offers a deeper understanding of handball and highlights its applicability to other team sports, maximizing performance through an integrative analysis of social, philosophical, and communicative components.

1. Introduction

Team sports have long been recognized as dynamic and highly interactive disciplines where individual contributions converge to form complex collective actions. Recent advancements in sports science have further solidified the view that team sports should be understood as complex dynamic systems, a paradigm that recognizes the intricate interplay between individual skills, tactical frameworks, and environmental variables [1,2,3]. This shift in perspective highlights that team performance is dynamic, meaning it constantly evolves through player interactions and environmental influences. It is also non-linear, as minor adjustments in positioning or decision-making can lead to significant changes in team coordination. Finally, emergent behaviors arise spontaneously from these interactions, enabling teams to self-organize and adapt to unpredictable situations. In this context, handball emerges as an ideal example of a system characterized by spontaneous adaptation, self-organization, and continuous evolution [4].

Handball’s complexity is evident in its fast-paced transitions, where players must make split-second decisions in response to their opponents’ movements, the position of the ball, and changing spatial arrangements [5]. Unlike static or predictable systems, handball reflects a dynamic process in which minor perturbations can lead to significant tactical shifts, a phenomenon described as non-linearity [5,6]. For example, a minor defensive adjustment, such as shifting a player one step forward, may disrupt the opposing team’s offensive strategy and force them to reorganize [6]. This characteristic underscores the importance of adaptability and synchronization in achieving cohesive team performance [7]. The concept of emergence plays a pivotal role in understanding handball as a dynamic system. Emergence refers to the spontaneous appearance of coordinated behaviors arising from individual actions and interactions [1,4]. In practical terms, this means that successful defensive or offensive sequences often arise without direct, external control from the coach but instead through real-time coordination among players [8]. A well-known example is when a defensive system “reads” an opponent’s intentions and adjusts its coverage as a cohesive unit, closing gaps and intercepting passes based on implicit cues rather than explicit instructions [9,10]. These emergent behaviors highlight the system’s capacity to self-organize and adapt to new challenges, reinforcing the importance of internal communication and shared perception [11].

Another key aspect of handball as a complex system is the concept of attractors. In dynamical systems theory, attractors are variables that guide system behavior toward specific patterns of stability [1,12,13]. In handball, attractors can include the ball’s location, the position of key playmakers, or tactical structures like defensive lines and offensive “diamond” formations [11]. However, these attractors do not create static conditions; they are constantly in flux as the game progresses [5]. Disruptions, such as an unexpected turnover or a defensive mistake, can cause the system to shift toward a new state of equilibrium, requiring players to reorganize and adapt in real time [6,8]. This continuous reorganization process is described as self-organization, a hallmark of complex systems [4,9]. Self-organization refers to the system’s ability to achieve coordinated behavior through internal adjustments rather than external directives [7]. In handball, this phenomenon is particularly evident during chaotic or high-pressure moments when explicit coaching instructions cannot be conveyed in time [8,10]. Instead, players rely on verbal and non-verbal communication, such as eye contact, hand gestures, and spatial positioning, to coordinate their movements and restore order [13]. This underscores the importance of training methodologies that foster autonomy, creativity, and real-time decision-making [11].

Despite its theoretical richness, much of the research on handball has focused on isolated technical-tactical components rather than examining the sport as an interconnected system [1,13]. This has led to a fragmented understanding of how individual and collective actions contribute to overall performance [2]. Moreover, the theoretical foundations of complex systems in sports have traditionally been drawn from disciplines such as physics and mathematics, with limited integration of insights from the social sciences and cognitive psychology [12]. Addressing this gap requires a multidisciplinary approach that incorporates frameworks such as chaos theory, Luhmann’s social systems theory, and perspectivism [14], among others.

Chaos theory provides a compelling lens for analyzing the unpredictable dynamics of handball. Unlike the traditional view of chaos as disorder, chaos theory describes systems that are highly sensitive to initial conditions, where small variations can lead to vastly different outcomes [9,13]. In handball, this means that a slight misstep by a defender or a sudden acceleration by an attacker can radically alter the flow of play [5]. Understanding this sensitivity can inform coaching strategies that emphasize adaptability and resilience rather than rigid adherence to predefined tactics [10]. Similarly, perspectivism, rooted in philosophical inquiry, offers valuable insights into how players and coaches interpret and respond to game situations [12]. According to this view, there is no singular “truth” in sports; rather, each participant perceives and constructs reality from their unique vantage point [14]. For example, a coach observing from the sidelines may interpret a sequence as a missed offensive opportunity, while the player executing the action may perceive spatial constraints that made an alternate decision impossible [8]. This divergence in perspectives highlights the need for effective communication and shared mental models to align individual interpretations with collective objectives [10]. Luhmann’s social systems theory complements these insights by emphasizing the role of communication, self-reference, and operational closure in shaping team dynamics [14]. According to Luhmann, social systems are defined by their ability to create meaning through internal processes of interpretation and adaptation [13]. In handball, the team functions as a self-referential social system, continuously interpreting external cues (e.g., opponents’ movements, referee decisions) and generating coordinated responses based on shared norms and communication codes [12]. This perspective underscores the importance of fostering a team culture where players can interpret and adapt autonomously while maintaining coherence and cohesion [14].

Considering both theoretical and practical implications, this narrative review provides a comprehensive analysis of handball as a complex dynamic system. By integrating insights from complex systems theory, cognitive science, and social systems theory, this study aims to analyze handball through the lens of complex dynamic systems, examining how emergent behaviors, non-linearity, attractors, and self-organization shape technical-tactical dynamics. Additionally, it explores the pedagogical implications of non-linear pedagogy in fostering adaptive expertise and decision-making in players, providing practical recommendations for designing training environments that reflect real-game complexity.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a narrative review approach to analyze handball as a complex dynamic system, integrating social and cognitive perspectives. Unlike systematic reviews, which follow predefined inclusion criteria and focus on quantitative synthesis, narrative reviews provide greater flexibility for integrating diverse theoretical frameworks and analyzing conceptual developments. This approach was chosen because it allows for a multidisciplinary examination of emergent behaviors, communication dynamics, and pedagogical implications in handball, aspects that are not easily quantifiable but are essential for understanding the sport’s complexity [1,3]. This approach facilitates the exploration of multidisciplinary concepts, such as emergence, non-linearity, and self-organization, within the context of handball’s technical-tactical dynamics [4,5].

2.1. PRISMA Protocol and Data Collection

Although this narrative review does not strictly adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, it follows a systematic process to ensure transparency and reproducibility in the data collection and analysis [15]. The literature search was conducted using academic databases, including PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search terms included combinations of relevant keywords, such as “handball”, “complex dynamic systems”, “self-organization”, “emergence”, “non-linear pedagogy”, “attractors”, “adaptive strategies”, “team coordination”, “chaos theory”, “perspectivism”, and “communication in sports” [5,6]. The inclusion criteria focused on studies that applied key theoretical concepts to handball or related team sports, emphasizing research that addressed interactions between technical, tactical, and cognitive dimensions [10]. Articles in both English and Spanish were included to capture a broader range of perspectives and avoid language bias [16]. There were no restrictions on publication dates, as this review sought to provide both historical context and recent advancements [17]. Conversely, studies with a purely linear approach or insufficient theoretical depth were excluded to maintain consistency with the complex systems framework [8].

2.2. Literature Selection Process

The initial search identified a wide array of studies across multiple disciplines, including sports science, biomechanics, education, and psychology. The selection process followed a multi-step approach:

Preliminary Screening: The titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles were screened for relevance to the conceptual framework of this review [18].

Full-Text Review: Articles that passed the initial screening underwent a detailed review to ensure that they addressed at least one of the key concepts (e.g., emergence, non-linearity, self-organization) within the context of handball or other team sports [5].

Categorization and Thematic Analysis: The selected articles were categorized based on their primary focus (e.g., communication, pedagogy, social studies, etc.) and analyzed for common themes, theoretical divergences, and practical applications [12].

This process facilitated the identification of key studies that contributed to the development of an integrative framework for understanding handball’s complexity [10,19]. To enhance the validity of the findings, cross-referencing was performed to ensure that key concepts were supported by multiple sources [8].

2.3. Conceptual Framework

The review’s conceptual framework was grounded in theories of complex dynamic systems, including chaos theory [7], self-organization [4], and social systems theory [14]. The primary focus was to analyze how these concepts manifest in handball’s technical-tactical behaviors and to identify their pedagogical implications [5]. The analysis also considered cognitive and perceptual processes, drawing on research from sports psychology to understand how players interpret and respond to dynamic game situations [20,21].

In addition to the foundational theories, this review incorporated interdisciplinary insights from sociology [9,13] and philosophy [14] to provide a holistic understanding of the emergent and adaptive nature of handball [3]. This integrative approach allowed for the examination of not only the physical and tactical components of the game but also the underlying cognitive and social mechanisms that drive team performance [12].

2.4. Methodological Rigor

To ensure methodological rigor, this review adhered to key scientific principles that enhanced its transparency, comprehensiveness, and critical evaluation of sources. The following criteria were applied throughout the review process:

Transparency: The literature search and selection process were documented in detail, including the keywords used, databases searched (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar), and inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure reproducibility.

Comprehensive Coverage: Both foundational and recent studies were included to capture the evolution of theoretical perspectives and emerging trends. The selection focused on research integrating technical-tactical, cognitive, and social aspects of handball.

Critical Appraisal: Each selected study was evaluated for methodological quality, theoretical contribution, and practical relevance. Studies with methodological weaknesses (e.g., lack of peer review, insufficient sample size) were noted but included if they provided valuable theoretical insights.

2.5. Scope and Limitations

While this narrative review offers a comprehensive synthesis of key concepts applicable to handball research, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. The reliance on narrative rather than systematic review protocols may introduce selection bias, as the inclusion process is inherently subjective [15]. Additionally, the review focuses primarily on team sports contexts, which may limit the generalizability of some findings to individual sports [17]. Despite these limitations, the narrative approach was deemed appropriate for exploring the multifaceted and interdisciplinary nature of handball as a complex dynamic system [14].

This review has been registered in Zenodo and is publicly available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15026952 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

3. Results

The results of the analysis of handball as a complex dynamic system are presented below, focusing on how the interaction of multiple factors influences team performance. The findings are structured around key concepts such as emergence, non-linearity, self-organization, and chaos theory, highlighting their role in the synchronization and adaptation of technical-tactical actions. Additionally, the relevance of communication and internal cohesion is explored as elements that enable the team to adjust to the changing demands of the game. These results provide an integrated understanding of handball and offer new perspectives for designing training strategies that enhance adaptability and autonomous decision-making in competitive contexts.

3.1. Chaos and Order

In the Spanish language, the word “chaos” is defined as something that presents disorder or refers to the amorphous state of cosmic arrangement [22,23]. From this perspective, greater chaos implies greater disorder. Historically, the processes of training, teaching, analysis, and technical direction in handball have aimed for order and control of actions, attempting to reduce uncertainty through structured models that organize both offensive and defensive processes [24,25,26].

Defensive systems, for instance, present an organized structure: players’ actions are conditioned by specific tasks according to the game model established by the coaches. Examples include the diagonals of the 3:2:1 defense, defensive doublings in closed systems like the 6:0 defense, or pressures on the odd-numbered player when the ball reaches the wing in a 5:1 or 4:2 defense [27,28]. These directives seek order in defensive actions within the system, avoiding the need for players to resolve unforeseen situations at every moment.

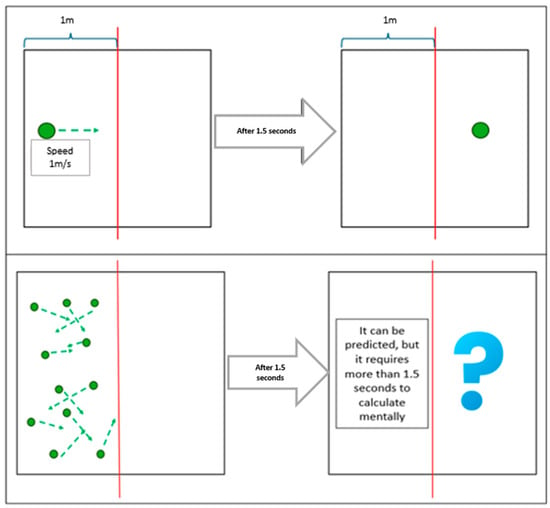

Offensive play is also organized, following predefined movements such as simple progressions, crossings, and one-on-ones, which, in their variability (due to feints, fakes, and players’ physical abilities), generate a certain level of uncertainty. This uncertainty increases in situations involving two-on-ones, two-on-twos, and up to six-on-sixes (or even seven-on-sixes), where the attacking team must adapt to defensive adjustments [29,30]. However, chaos theory, within the framework of general systems theory, redefines “chaos” not as disorder but as a difficulty in predicting outcomes due to high sensitivity to variations within systems. In chaotic systems, small initial variations can generate outcomes that appear random and difficult to anticipate [31]. Mathematical models of chaos theory make it possible, under specific conditions, to predict the future position of an element in a given space if it maintains a constant speed. However, when the number of elements increases, along with variability in speeds and spatial complexity, the capacity to predict their locations diminishes, rendering the system chaotic (though not necessarily disordered) (Figure 1) [32].

Figure 1.

The effect of multiple moving objects on predictability and chaos in a dynamic system.

When observing handball through this theory, it is possible to identify complex tactical interactions in the offensive cycle that increase chaos, particularly when players occupy various spaces and move at different speeds [33]. These simultaneous and coordinated group actions create dynamics that make it challenging for defenders to predict the position, speed, or direction of each attacker [34]. These interactions do not represent a lack of structure but rather an organization that appears chaotic, allowing the offensive team to self-organize in response to changing and unforeseen game conditions. Thus, the attacking team, behaving as a complex dynamic system, generates situations that may seem chaotic but are, in reality, the result of the interaction of all its components following an intrinsic order [35]. Offensive groupings or nuclei create chaos in small spaces through movements without a fixed structure, combining diverse tactical actions such as overlaps or passing cycles that create multiple fixations [36]. These tactical interactions generate “turbulence” in one sector of the field, forcing the defense to constantly adapt to variations in position and timing within limited spaces [37]. This results in defensive redistribution, increasing density in one sector while decreasing it in another, not through traditional defensive supports but through adaptive responses to the unpredictability generated by attackers’ constant variations. Thus, chaos, far from being disorder, becomes a strategic resource to generate uncertainty and difficulties for the defensive system [38].

Defensive tactical actions also demonstrate chaos theory, particularly in their capacity to adapt and respond to constant variations arising from offensive intentions. In a dynamic where every attacker’s movement alters spatial and temporal configurations, the defense must continuously process emerging information, limiting attackers’ movements and disrupting their passing connections [39]. In this context, the defense interrupts the fluidity of collective and individual offensive actions by disassembling the attack, creating a constant flow of positional changes that form a flexible organization. Far from rigid stability, the defensive structure maintains coherence through these constant adjustments, with each player repositioning according to the opponent’s movements. This type of defensive organization creates “controlled chaos”, in which the defensive system responds as an adaptable unit, limiting offensive opportunities through an individual-collective defense strategy [40].

3.2. Perception, Perspective, and Truth

The management of a handball team is traditionally based on the coach’s general observation and supervision, who analyses the playing field from the bench and adjusts collective actions according to their perception [33]. Meanwhile, players make specific decisions based on the provided instructions, continuously adapting to the opposing team’s actions to achieve their own objectives [34]. In this context, communication between participants is fundamental; both verbal and non-verbal communication serve as essential channels for coordination. For instance, defensive players often rely on quick verbal cues such as “shift” or “cover” to adjust their positions in real time. Meanwhile, non-verbal signals like hand gestures, eye contact, or even changes in body orientation allow teammates to anticipate actions without explicit instructions. This implicit communication is particularly valuable in high-pressure situations, such as counterattacks, where immediate verbalization may not be possible. However, studies in handball have focused on the transmission of information without delving into the interpretation and the value each individual assigns to it based on their role [35]. The process of listening, interpreting, observing, deciding, and executing actions involves a series of cognitive and mental operations that players experience throughout the match [36]. These processes also occur in the coach, with one important difference: their actions are not conditioned by the opponent’s physical intervention, allowing them to focus on observation without needing to move actively during the game [37].

Often, what the coach observes and defines is interpreted as “the truth”, while the players’ perceptions are understood as “opinions.” Truth, in this context, refers to objective, verifiable elements of the game, such as player positioning, ball trajectory, and rule enforcement. In contrast, opinion emerges from the subjective evaluation of game situations, shaped by experience, intuition, and individual roles within the team. This distinction is crucial in tactical discussions, as misalignments between objective facts and subjective interpretations can lead to communication breakdowns. There are instances where players express that they feel unable to perform a certain action, even though the coach considers it clear and has insisted on its execution. Conflicts can also arise among players because, from their perspective, someone failed to execute an action they deemed evident. Recognizing the interplay between truth and opinion allows for a more refined approach to team communication and decision-making, fostering alignment between strategic intentions and on-court execution [39,40].

3.3. The Handball Team as a Social System

Niklas Luhmann’s social systems theory posits that social systems are self-referential structures that operate through internal logic and specific communication codes, guiding their interactions and organization. According to this theory, each social system, such as politics, the economy, or education, establishes boundaries that differentiate it from other systems and its external environment through the creation of unique rules, values, and interpretive processes, enabling it to function autonomously [40]. A central concept within this theory is operational closure, which asserts that social systems do not interact directly with their environment; rather, they respond to external stimuli through their internal logic, interpreting these stimuli according to the system’s specific codes. In this way, participants within a social system share meanings and communication methods that are exclusive to that system, creating an environment where interpretation and communication occur on their own terms [41]. As these systems grow and become more complex, their capacity for autopoiesis, or self-organization, allows them to adapt to change and maintain internal cohesion, operating stably despite external variations [42].

In handball, the team functions as an autonomous social system operating under its own internal logic and codes, reflecting Luhmann’s social systems theory. Within this system, players, coaches, and other members communicate and organize according to roles, rules, and strategies that only make sense within the team context. Each participant interprets instructions and interactions based on a shared framework, which is strengthened through practice and shared experiences, generating a unique language and dynamic that fosters team cohesion and adaptability [43]. However, as Luhmann highlights with the concept of the double contingency, communication is never completely precise nor interpreted exactly as intended by the sender; rather, it is subject to constant reinterpretations and adjustments.

4. Discussion

The findings of this narrative review reinforce the importance of conceptualizing handball as a complex dynamic system rather than a series of isolated technical or tactical components. This perspective highlights the interconnectedness of players, tactical structures, and environmental conditions, emphasizing how collective behaviors emerge through interactions rather than through pre-scripted sequences [1,7]. By examining key concepts such as emergence, non-linearity, chaos theory, and self-organization, this review contributes to a deeper understanding of how team performance evolves and adapts in real-time competition [4,14].

4.1. Emergence as a Core Mechanism in Collective Play

A significant takeaway from this review is the role of emergent behaviors in fostering synchronization and adaptability. Emergence refers to the spontaneous formation of organized behaviors from individual interactions [18]. This phenomenon is especially prominent in defensive scenarios, where players must collectively anticipate and react to offensive threats without explicit verbal instructions [19,23]. Successful defensive adjustments, such as shifting coverage to close passing lanes or switching marks to neutralize offensive pivots, often arise from shared environmental perceptions and internal feedback loops [5,17].

Emergent behaviors rely heavily on the development of shared mental models, which enable players to interpret cues consistently and synchronize their actions [19]. Studies by Davids et al. [18] highlight the importance of implicit coordination, where non-verbal communication (e.g., body orientation, eye contact) plays a critical role in spontaneous decision-making. This supports the notion that emergence is not simply reactive but is influenced by training environments that promote game sense—the ability to read and respond to tactical developments in real time [35]. To foster emergent behaviors, it is essential for training programs to move beyond isolated technical drills and incorporate constraint-led approaches that simulate real-game variability [13]. For instance, defensive drills that limit verbal communication or impose random positional constraints can encourage players to rely on implicit communication and develop a heightened sensitivity to their teammates’ actions [41].

4.2. Non-Linearity and Its Impact on Tactical Decision-Making

The principle of non-linearity illustrates that small variations in initial conditions can lead to disproportionately large outcomes [9]. In handball, this manifests in scenarios where subtle changes—such as an attacker shifting their position by a single step, can force defensive players to reorganize, creating or closing gaps in the defensive structure [11,18]. This challenges the traditional coaching assumption that tactical success is the result of linear cause-and-effect relationships [28]. Research in non-linear dynamics by Araújo et al. [4] suggests that non-linearity underpins the adaptive nature of offensive transitions, where quick decisions, feints, or unexpected passes can destabilize defensive structures [29]. For example, a slight delay in a pass may give defenders the extra second they need to reposition, while a well-timed cross-court pass can create a critical spatial advantage for the offense [20,26].

The concept of attractors further reinforces the importance of non-linearity. Attractors temporarily stabilize system behavior by guiding player movements and decision-making based on key variables, such as the ball’s position or the placement of key playmakers [17]. However, these attractors are not static and can shift due to external disturbances, such as rapid ball rotations or sudden defensive presses. This “shifting attractor” phenomenon illustrates the dynamic balance between structure and improvisation in handball strategy [25]. Training that incorporates non-linear elements should include variable practice conditions that challenge players to adapt to unpredictable stimuli [37]. For instance, positional training that introduces fluctuating defender placements and unexpected spatial constraints can enhance players’ ability to identify and exploit emerging gaps. This approach aligns with research indicating that players trained in non-linear environments exhibit superior adaptability and situational awareness compared to those trained through repetitive, linear drills [30,36].

4.3. Chaos as a Tactical Resource: Balancing Structure and Unpredictability

Chaos theory offers a valuable lens for understanding the unpredictable dynamics of handball. Unlike the traditional view of chaos as disorder, chaos theory emphasizes that unpredictability can be harnessed to create organized complexity [16]. In handball, chaotic dynamics are particularly evident during transitions between offense and defense, where rapid changes in possession and spatial arrangements can lead to tactical imbalances [24]. Offensive chaos can be deliberately used to create turbulent zones that destabilize defensive structures [10,29]. For example, overlapping runs, quick directional shifts, and feints can force defenders into reactive states where they struggle to anticipate the next action [25,33]. By creating unpredictability, offensive teams can force defenders to make split-second decisions, increasing the likelihood of defensive errors [22,40]. Defensive chaos, conversely, involves the strategic use of disruptive actions such as coordinated pressing, double-teaming, or sudden defensive rotations to break the offensive flow and regain possession [27]. When applied effectively, defensive chaos can force turnovers and create opportunities for fast breaks. However, research by Magnaguagno et al. [29] highlights that teams must balance chaos with structure to avoid becoming disorganized themselves. Players must develop the capacity to transition seamlessly between moments of chaos and re-stabilization, a concept known as meta-stability [7].

To train players to navigate chaotic game scenarios, coaches can implement randomized drills that introduce unpredictable defensive patterns, time constraints, and simulated turnovers [35]. These drills can improve players’ resilience, decision-making, and ability to self-organize under pressure [41]. Studies have shown that exposure to chaotic conditions in training enhances players’ anticipation skills and prepares them to handle the unpredictability of real matches [31].

4.4. Self-Organization and Team Cohesion

Self-organization is a defining characteristic of dynamic systems and refers to the spontaneous coordination of system components in response to external disturbances [14]. In handball, self-organization is essential for maintaining internal cohesion during defensive recoveries and offensive transitions [39]. For example, when a defender is temporarily out of position following a turnover, the remaining players may intuitively shift to cover open spaces and delay the opponent’s fast break [26].

Self-organization is facilitated by implicit communication mechanisms that enable players to synchronize their actions without the need for explicit instructions [20]. These mechanisms include body positioning, subtle gestures, and anticipatory movements that convey tactical intentions [42]. Luhmann’s social systems theory underscores the importance of shared codes and norms in fostering effective self-organization [14]. By internalizing these codes during training, players develop a collective “language” that guides their interactions and ensures cohesion in complex scenarios [40].

The concept of autopoiesis, introduced by Maturana and Varela [43], further reinforces the notion that teams must continuously regenerate their structure to maintain coherence. This process of self-regeneration is particularly important in “scramble” situations, where the team must reorganize after an unexpected disruption, such as a deflected pass or a defensive error [9,41]. Training that incorporates adaptive scrimmages, where players are tasked with reorganizing after simulated turnovers, can enhance their ability to self-organize and maintain stability during chaotic moments [35,44].

4.5. Communication and Perspective-Sharing

Effective communication is fundamental to achieving synchronization and alignment within a team [36]. In handball, players often communicate through coded verbal commands or pre-established non-verbal signals to indicate tactical intentions. For example, a pivot might use subtle hand positioning to signal a screen or a cut, while a goalkeeper might rely on eye contact to coordinate defensive reactions with backline defenders. These shared signals create a common tactical language that facilitates rapid decision-making and enhances team cohesion. Communication extends beyond verbal instructions to include non-verbal cues, such as hand signals, eye contact, and movement patterns [23]. These cues enable players to anticipate their teammates’ intentions and coordinate their actions accordingly [22]. However, as highlighted by perspectivism, communication is inherently subjective, as individuals interpret information based on their unique experiences and roles within the game [45]. For example, a coach observing from the sidelines may interpret a defensive misalignment as a failure to close a passing lane, while the defender may view it as a necessary adaptation to counter an unexpected offensive maneuver [41]. This divergence in perspectives underscores the importance of fostering reflective practices that encourage players and coaches to discuss and align their interpretations of tactical scenarios [31]. Post-game video analysis sessions and role-switching drills, where players adopt different positions to gain new perspectives, can reduce perceptual mismatches and enhance team synchronization [21,45].

Nobre et al. [37] concluded that teams with strong communication frameworks demonstrate greater resilience and adaptability. To strengthen communication, training should incorporate scenario-based exercises that require players to make collective decisions under time constraints [33]. These exercises can help players develop efficient communication patterns and improve their ability to synchronize their actions during high-pressure situations [28].

4.6. Implications for Coaching and Pedagogy

The findings of this review suggest that modern handball coaching should prioritize non-linear, context-rich training environments that simulate the complexity of real-game situations [17,39]. Traditional, prescriptive approaches that focus on isolated skill development may limit players’ ability to adapt to dynamic game conditions [5]. Instead, constraint-led training, which introduces variability, unpredictability, and task-specific challenges, can foster players’ capacity for creative problem-solving, self-organization, and emergent decision-making [18,42]. By integrating insights from systems theory, cognitive science, and pedagogy, coaches can design training sessions that promote autonomy, adaptability, and resilience [41]. These sessions should emphasize exploration within constraints, providing players with opportunities to experiment with different strategies and develop their tactical intelligence [34,38]. Research suggests that players exposed to such environments exhibit greater composure and decision-making efficiency during competitive matches [45].

5. Limitations and Future Directions

While this narrative review provides a multidisciplinary perspective on handball as a complex dynamic system, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the reliance on a qualitative synthesis rather than a systematic or meta-analytical approach may introduce selection bias, as the inclusion of studies was based on conceptual relevance rather than standardized criteria. Future research could complement this review by conducting meta-analyses that quantify the impact of emergent behaviors, non-linearity, and self-organization on performance outcomes.

Additionally, this review primarily focuses on conceptual and theoretical aspects, with limited empirical validation of the proposed frameworks. Further studies should integrate experimental designs or data-driven performance analysis to empirically assess how complex systems theory applies to real-game situations in handball. Future investigations could also explore the role of individual differences in adaptability and decision-making within a non-linear pedagogical context.

Finally, while this review emphasizes handball as a case study, its findings may be applicable to other invasion team sports with similar structural and tactical complexities. Comparative studies across different team sports could provide additional insights into how complexity theory shapes collective performance across disciplines.

6. Conclusions

This narrative review reinforces the conceptualization of handball as a complex dynamic system characterized by emergent behaviors, non-linearity, self-organization, and adaptive communication. Rather than viewing team performance as the sum of individual technical actions, this perspective underscores the dynamic interactions between players, tactical structures, and environmental variables that shape collective behaviors. The findings highlight the importance of fostering adaptability, creativity, and autonomy through non-linear, constraint-based training methodologies that reflect the unpredictable and variable conditions of competitive play.

A key insight from this review is the central role of emergence in shaping team performance. Emergent behaviors, such as spontaneous defensive shifts and offensive overlaps, demonstrate players’ capacity to self-organize and synchronize their actions based on shared perceptions of the game environment. This reinforces the need for training environments that cultivate implicit coordination and “game sense,” enabling players to make real-time decisions independent of explicit directives from coaches. The review also illustrates that non-linearity is a defining characteristic of handball’s tactical dynamics. Small changes in positioning, timing, or decision-making can result in disproportionate outcomes, reinforcing the need for perceptual sensitivity and situational awareness. By incorporating variability and unpredictability into training drills, coaches can enhance players’ capacity to recognize and exploit subtle cues that influence the flow of the game.

Chaos theory further enriches this understanding by portraying handball as a system that operates on the edge of order and unpredictability. Offensive chaos, characterized by fluid movements and unstructured runs, can disorient defenses and create scoring opportunities, while defensive chaos leverages calculated disruptions to force opponents into reactive errors. Managing chaos effectively requires players to develop resilience and transition fluidly between structured play and spontaneous improvisation.

Additionally, the findings underscore the importance of self-organization in maintaining team cohesion under high-pressure situations. Self-organization enables players to reorganize dynamically in response to disruptions, such as turnovers or positional errors, without sacrificing tactical coherence. This process is supported by implicit communication, shared tactical frameworks, and continuous self-regeneration, highlighting that effective teams function as autonomous, self-referential systems capable of adapting to internal and external changes.

The review also emphasizes the role of communication and perspectivism in aligning individual interpretations of game scenarios. Effective communication extends beyond verbal directives and includes non-verbal signals that facilitate synchronization and decision-making. However, communication is inherently subjective, as players interpret cues through the lens of their roles and perspectives within the team. Reflective practices, such as post-game analyses and role-switching exercises, can foster a more cohesive tactical language and mitigate perceptual mismatches during matches.

Implications for Coaching and Future Research

From a pedagogical perspective, these findings suggest that traditional, linear approaches to handball training may be insufficient for developing the adaptive expertise required in dynamic game contexts. Coaches should adopt non-linear pedagogical models that prioritize exploratory learning, real-time feedback, and constraint-led drills that replicate the complexities of real matches. By designing training environments that foster emergent behaviors, self-organization, and decision-making under pressure, coaches can better prepare players to excel in high-stakes, unpredictable scenarios.

Future research should focus on empirical studies that measure the effects of constraint-based training interventions on competitive performance. Longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights into how emergent coordination and adaptive decision-making evolve over time and under various training conditions. Additionally, further exploration of the applicability of complex systems theory to other team sports could reveal universal principles for optimizing performance in dynamic, high-interaction environments.

By bridging the gap between theoretical frameworks and practical applications, this review offers valuable recommendations for coaches, players, and researchers seeking to enhance team performance through a complexity-based approach. Ultimately, adopting a multidisciplinary lens that integrates insights from systems theory, cognitive science, and pedagogy can contribute to the development of more adaptive, resilient, and high-performing teams.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; methodology, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; formal analysis, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; investigation, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; resources, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; data curation, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; writing—review and editing, S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by S.E.-L. and C.H.-T.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Balague, N.; Torrents, C.; Hristovski, R.; Davids, K.; Araújo, D. Overview of complex systems in sport. J. Syst. Sci. Complex. 2013, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, J. Análisis de Sistemas Dinámicos y Complejos en la Liga Profesional de Balonmano de España. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espoz-Lazo, S. Propuesta Metodológica para la Enseñanza de las Habilidades Técnico-Tácticas del Balonmano en Etapas de Formación a Partir del Desarrollo de las Dimensiones que Componen al ser Humano: Fundamentos Desde la Teoría de los Sistemas Dinámicos Complejos. Doctoral Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2022. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10481/77677 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Araújo, D.; Brito, H.; Carrilho, D. Team decision-making behavior: An ecological dynamics approach. Asian J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2023, 3, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Rodríguez, J.; Ramírez-Macías, G. Non-linear pedagogy in handball: The influence of drill constraints. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2021, 143, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Rodríguez, J.; Alvite-de-Pablo, J.R. Indicadores de rendimiento ofensivo de la selección española femenina de balonmano en el Mundial Japón 2019. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2023, 152, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, D. Autoorganización en Sistemas Compuestos: Sincronización, Turing, Fluctuaciones. Doctoral Thesis, University of Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Espoz-Lazo, S.; Farías-Valenzuela, C.; del Val-Martín, P.; Hinojosa-Torres, C. La autoorganización en la defensa 3:2:1 en balonmano: Conductas desde los sistemas dinámicos complejos. SPORT TK-Rev. EuroAm. Cienc. Deporte 2024, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, S. Teorías sobre los sistemas complejos. Adm. Desarro. 2017, 47, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espoz-Lazo, S.; Farías-Valenzuela, C.; Hinojosa-Torres, C.; Giakoni-Ramírez, F.; del Val-Martín, P.; Duclos-Bastías, D.; Valdivia-Moral, P. Activating specific handball’s defensive motor behaviors in young female players: A non-linear approach. Children 2023, 10, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Rodríguez, J. Pedagogía no Lineal Aplicada a la Enseñanza del Balonmano. Doctoral Thesis, University of Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://idus.us.es/items/1943b042-a8ff-43f2-b064-434157e49296 (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Vilches, A.M.; Legarralde, T.I. Aspectos Biológicos de la Complejidad Humana; Libros de Cátedra: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.G.; Grajeda, J.G.; Mayo, A. Las organizaciones como sistemas complejos. Política Cult. 2021, 56, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Sistemas Sociales: Lineamientos para Una Teoría General; Anthropos Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Thorne, S.; Malterud, K. Narrative review methods. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, J.Y.; Davids, K.; Button, C. Non-Linear Pedagogy in Skill Acquisition; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Passos, P.; Davids, K. Coordination dynamics in rugby. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2015, 41, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, L.; Araújo, D.; Button, C. Ecological dynamics and team sports coordination. In Skill Acquisition in Sport: Research, Theory and Practice; Williams, A.M., Hodges, N.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 155–175. [Google Scholar]

- Bourbousson, J.; Sève, C.; Poizat, G. Team coordination processes in team sports. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2010, 22, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, A.; Bailey, C.; Alfes, K.; Fletcher, L. Using narrative evidence synthesis in HRM research: An overview of the method, its application, and the lessons learned. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espoz-Lazo, S.; Hinojosa-Torres, C.; Farías-Valenzuela, C.; del Val, P. Communication in Handball Training and Performance: A Lost Variable. Sportis 2024, 10, 212–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elena, B. The importance of anticipation in increasing the defense efficiency in high-performance handball. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 76, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Academia Española. Diccionario de la Lengua Española. Available online: https://dle.rae.es/caos?m=form (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Menezes, R.P.; Putti, G. Sistemas de juego en balonmano en equipos escolares: Opciones de entrenadores en las categorías SUB-14 y SUB-17. Educ. Fís. Deporte 2019, 38, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.C.; Greco, P.J.; Ibáñez, S.J.; do Nascimento, J.V. Construcción del modelo de juego en balonmano. Pensar Mov. 2021, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón García, J.L. Análisis Evolutivo Estructural y Funcional del Sistema Defensivo 3:2:1; Imprentaweb Editorial: Granada, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Espina Agulló, J.J.; Pérez Turpin, J.A.; Cejuela Anta, R. Historical, Tactical, and Structural Evolution of the 5-1 Defensive System in Handball. Apunts. Educ. Fís. Deportes 2012, 110, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaguagno, L.; Hossner, E.J.; Schmid, J.; Zahno, S. Decision-making performance and self-generated knowledge in handball-defense patterns: A case of representational redescription. Ger. J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2023, 53, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallegrave, E.J.; Beirith, M.K.; Salles, W.N.; do Nascimento, J.V.; Folle, A. Analysis of tactical-technical attack performance factors: A case study of a professional women’s handball team. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2024, 13, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzimanouil, D.; Saavedra, J.M.; Lola, A.; Skandalis, V.; Gkagkanas, K. Analysis of movement and actions of wingers as second-line players in organized attack in handball. J. Hum. Kinet. 2024, 92, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, B. Geometría y método en diseño gráfico: Del paradigma Newtoniano a la Teoría General de Sistemas, el Caos y los Fractales. Arte Individuo Soc. 2012, 24, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arch-Tirado, E.; Collado-Corona, M.Á.; Lino-González, A.L.; Terrazo-Lluch, J. Uncertainty, dynamic systems, principles of quantum mechanics and their relationship to the health-disease process (analysis proposal). Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2020, 94, e202012136. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Salas, J.; Morillo-Baro, J.P.; Reigal, R.E.; Morales-Sánchez, V.; Hernández-Mendo, A. Análisis de coordenadas polares para el estudio de los sistemas defensivos en balonmano. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2020, 20, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chepea, B. Challenges determined by the new trends in handball communication. Ann. Dunarea Jos Univ. Galati. Fascicle XV Phys. Educ. Sport Manag. 2023, 2, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, F.M. Constructing a competition communication skills scale for the elite and first division handball league coaches. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deporte 2023, 18, 210–212. [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, T.; Rocha, L.; Ramos, C.; Carbone, P.; Madureira, D.; Rodrigues, B.; Caperuto, É. The use of proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation for increasing throwing performance. Rev. Bras. Med. Esporte 2020, 26, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikicin, M.; Szczypińska, M. Does perceptual-motor training improve behavioral abilities of handball players? J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2021, 21, 2244–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Ocaña, A. La interacción entre los sistemas vivos, psíquicos y sociales en la teoría sistémica de Niklas Luhmann. Praxis Filosófica 2021, 52, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. ¿Cómo es Posible el Orden Social? Herder: Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grijalbo, C.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Guzmán, J.F. Verbal coping of coaches in competition: Differences depending on emotional intelligence and self-determined motivation. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2022, 17, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.; Loft, M.S.; Schiessl, I.; Maravall, M.; Petersen, R.S. Sensory adaptation in the barrel cortex during active sensation in the behaving mouse. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Just, B.; Torres de Farias, S. Living cognition and the nature of organisms. BioSystems 2024, 246, 105356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanne, T.; Volossovitch, A. Team regulatory strategies and performance in elite handball. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2023, 94, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, A.W. Communicating in sports teams. In The Emerald Handbook of Group and Team Communication Research; Beck, S.J., Keyton, J., Poole, M.S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2021; pp. 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).