Abstract

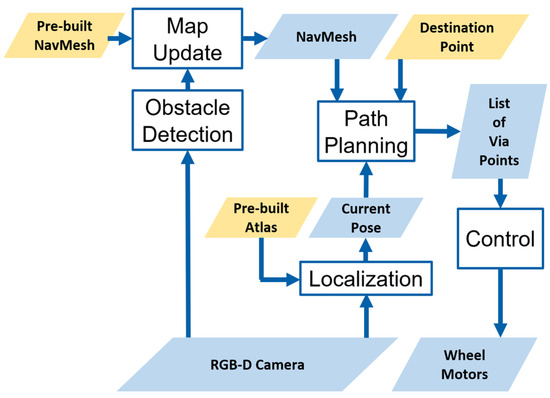

This paper presents a 3D vision-based autonomous navigation system for wheeled mobile robots equipped with an RGB-D camera. The system integrates SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping), motion planning, and obstacle avoidance to operate in both static and dynamic environments. A real-time pipeline is developed to construct sparse and dense maps for precise localization and path planning. Navigation meshes (NavMeshes) derived from 3D reconstructions facilitate efficient A* path planning. Additionally, a dynamic “U-map” generated from depth data identifies obstacles, enabling rapid NavMesh updates for obstacle avoidance. The proposed system achieves real-time performance and robust navigation across diverse terrains, including uneven surfaces and ramps, offering a comprehensive solution for 3D vision-guided robotic navigation.

1. Introduction

Autonomous navigation is a core challenge in robotics, with applications spanning industrial automation, transportation, surveillance, and search and rescue operations [1]. A robot’s ability to navigate its environment relies on three key components: simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM), path planning, and motion control [2]. SLAM, a critical technology, integrates sensor data to estimate the robot’s pose while constructing an environmental map [3]. Traditional mapping methods predominantly utilize two-dimensional (2D) grid representations, which, while effective, fall short of capturing the complexity of three-dimensional (3D) environments. In contrast, our research focuses on the richer and more intuitive domain of 3D spatial representation, particularly emphasizing real-time relocalization to maintain continuous and accurate localization.

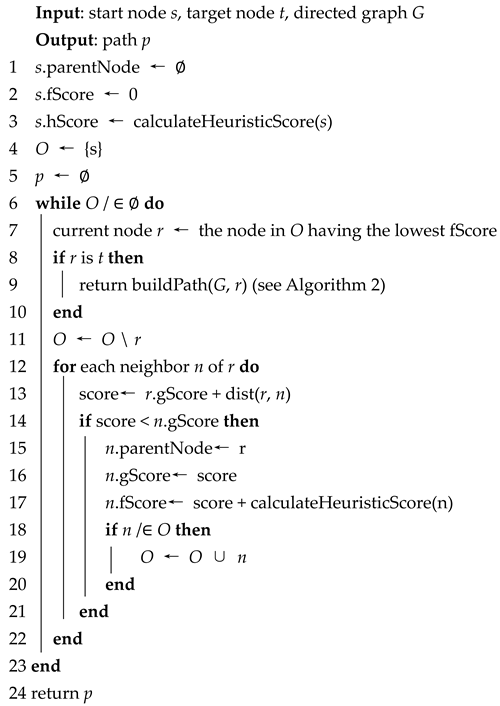

Path planning, another fundamental aspect of autonomous navigation, seeks to identify collision-free routes from the robot’s current position to its target, optimizing factors such as travel distance and time [4]. Dynamic path replanning is especially vital in changing environments, necessitating fast adaptation to obstacles and other changes.

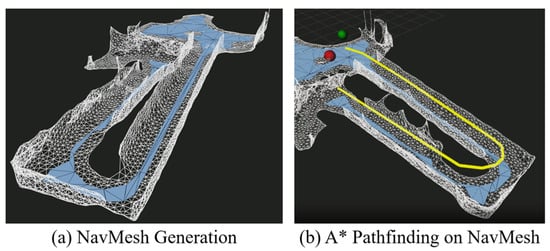

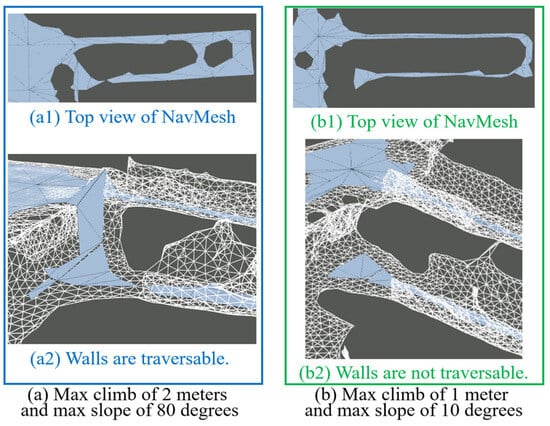

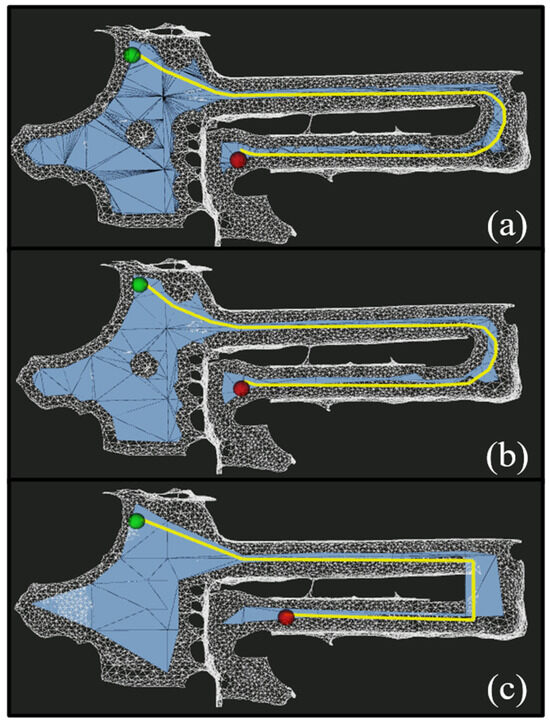

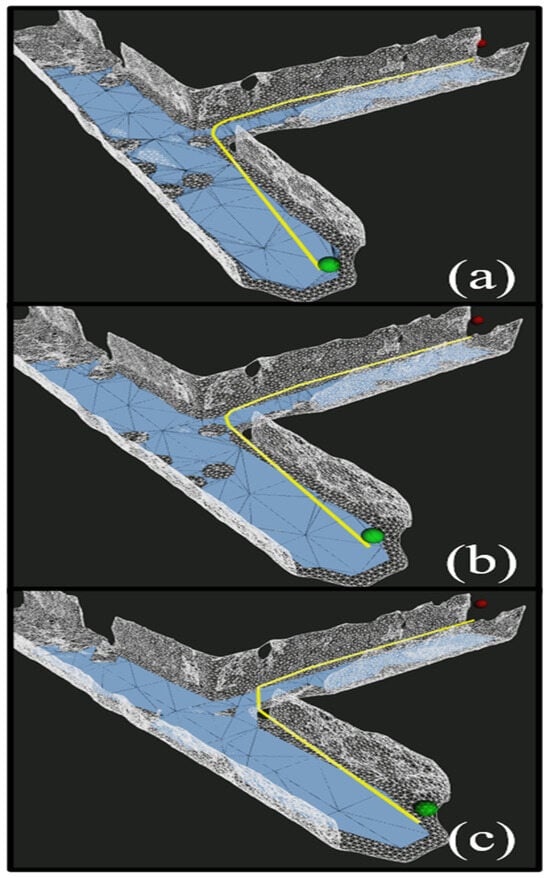

This research introduces the use of navigation mesh (NavMesh) as a precise navigation framework for wheeled mobile robots operating in complex 3D environments. Unlike conventional 2D grid-based pathfinding methods, which often generate paths with high node complexity, NavMesh [5] offers a more efficient solution by reducing node density on the resultant paths. This reduced complexity enables real-time navigation and smoother robot movements, further enhanced by via-point control strategies. In additional, the integration of NavMeshes with real-time “U-map” allows for updates for dynamic obstacle avoidance. Clearly positioning the work within the broader field of robotic navigation will enhance its impact.

Our primary objectives are twofold:

- To construct comprehensive 3D maps and convert them into navigation meshes, facilitating seamless navigation in intricate 3D settings.

- To demonstrate efficient path replanning with reduced node complexity, enabling adaptation to dynamic environments.

This framework, designed for mobile robots equipped with RGB-D cameras, addresses the intertwined challenges of SLAM, motion planning, and obstacle avoidance, ensuring robust operation in both static and dynamic scenarios.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Navigational Challenges in Multilevel Environments

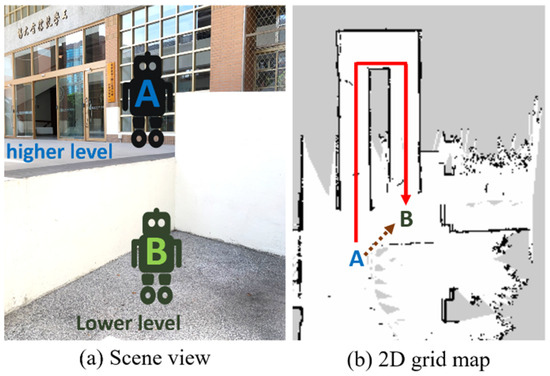

In multilevel environments, 2D SLAM techniques face inherent limitations. For instance, as depicted in Figure 1, consider a robot labeled as A positioned at an elevated level, while another robot, designated as B, is located at a lower elevation. When a 2D LiDAR sensor mounted on robot A perceives the location of robot B, it may incorrectly interpret the path as traversable. However, physical constraints prevent wheeled robots from overcoming significant vertical obstructions, rendering the path infeasible. This discrepancy between perception and reality is exemplified in Figure 1b, where GMapping [6], a 2D LiDAR-based SLAM algorithm, erroneously calculates a direct route across a wheelchair ramp (dotted arrow). In contrast, the actual feasible path (solid arrow) requires the robot to navigate the ramp appropriately. This highlights the pressing need for navigation systems that can accurately account for multilevel environments and robot mobility constraints.

Figure 1.

Navigation on the wheelchair ramp. An unfeasible path (dotted arrow) is calculated on the 2D grid map, while the solid arrow is the path passing through multilevel environments.

2.2. Challenges in 3D Mapping and Navigation

Mesh reconstruction techniques hold great potential for 3D mapping in multilevel environments. However, several challenges remain in achieving fully autonomous navigation. One of the primary difficulties is enabling robots to traverse unfamiliar terrains without prior knowledge. While integrating RGB-D cameras into SLAM systems has shown promise, these methods often encounter limitations, such as incomplete depth data and difficulties in accurately replicating real-world scenarios.

Although advancements in 3D navigation and pathfinding algorithms have been made [7], practical implementations frequently rely on 2D occupancy grids [8]. For example, the A* algorithm [9], widely adopted for global planning in the Robot Operating System (ROS) [10], suffers from high memory demands [11], especially in large-scale or complex environments [12]. This issue becomes critical during real-time path replanning. A 21 m path generated on a 2D grid map with a resolution of 5 cm typically involves over 400 nodes, leading to considerable computational overhead. This high node density not only increases memory usage but also poses challenges for real-time path planning, especially in large-scale or complex environments. Table 1 presents a comparative analysis of various pathfinding algorithms, highlighting their advantages and limitations in different scenarios. For more detailed pathfinding algorithms, please refer to [13].

Table 1.

Comparison of different pathfinding algorithms.

Research into 3D navigation methods has produced promising results. Putz et al. employed the Fast Marching Method on triangular meshes to compute vector fields for pathfinding [17]. However, such approaches often lack comprehensive pipelines for mesh map construction and mechanisms for real-time obstacle avoidance. Furthermore, while voxel-based approaches can approximate walkable surfaces, they introduce a trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency [18].

When considering motion control, existing 2D planners, such as the dynamic window approach (DWA), face compatibility challenges in 3D settings [19]. For instance, while effective in addressing obstacles in 2D, DWA struggles in dynamic environments and narrow spaces. This highlights the necessity of extending collision avoidance to fully account for 3D spaces, ensuring robust and efficient navigation.

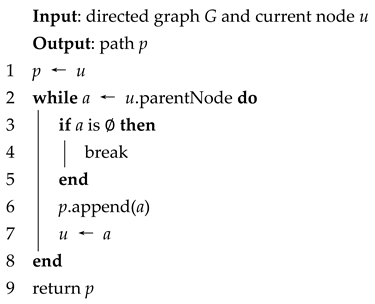

2.3. The Vision-Based 3D Autonomous Navigation Framework

In response to these challenges, this paper introduces a novel 3D vision-based autonomous navigation framework tailored for wheeled mobile robots equipped with RGB-D cameras. Our approach addresses the intertwined challenges of SLAM, motion planning, and obstacle avoidance in both static and dynamic environments.

Leveraging RGB-D data, our framework ensures seamless navigation through multilevel environments while adapting to dynamic obstacles. Key contributions include the following:

- The development of a robust 3D SLAM system that integrates RGB-D data for accurate mapping and localization.

- The implementation of efficient 3D pathfinding algorithms that reduce computational complexity.

- The design of collision avoidance mechanisms optimized for real-time operation in 3D dynamic spaces.

By integrating SLAM, pathfinding, and motion control components, our framework provides a comprehensive solution for navigating complex environments, ensuring safe and efficient robot operation.

3. Pipeline for 3D Mesh Reconstruction

ORB-SLAM3 [20] is widely recognized for its high accuracy in real-time localization and mapping scenarios, particularly in dynamic environments and large-scale scenes. It achieves this through an efficient loop-closure detection method that enhances map accuracy. However, it is important to note that when used concurrently with other tasks, ORB-SLAM3 may require additional computing resources as it operates at full capacity in real time on a standard computer. Furthermore, the accuracy of the RGB-D module in ORB-SLAM3 relies on sensor measurements. Despite these limitations, the growing affordability and popularity of GPUs provide a practical solution for accelerating specific tasks.

To better understand the performance of ORB-SLAM3 in comparison to other SLAM approaches, Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of various SLAM methods, focusing on key aspects such as sensor requirements, computational efficiency, and localization performance.

Table 2.

Comparison of SLAMs.

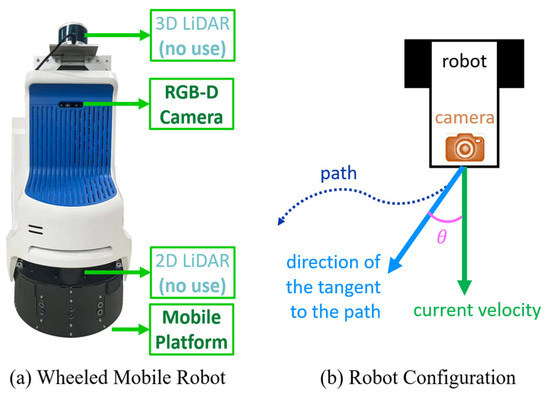

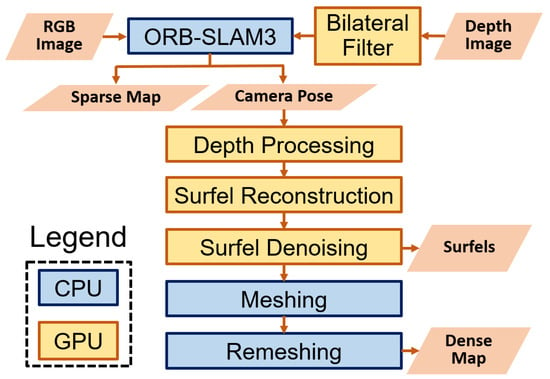

In this section, we present an enhanced RGB-D module for SLAM that harnesses GPU acceleration to achieve real-time performance, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Real-time pipeline for 3D reconstruction.

3.1. Depth Information Patching

The inherent limitations of camera technology result in depth images often containing significant artifacts, such as holes, reflections, and other sources of error. To mitigate these issues, we integrate a bilateral filter into the processing pipeline.

A bilateral filter [23] is a noise-smoothing and edge-preserving filter governed by range and spatial parameters. This filtering method not only enhances the quality of depth maps by reducing noise and preserving structural details but also effectively minimizes the occurrence of holes, thereby improving the accuracy of localization.

To evaluate the effectiveness of this approach, we conducted experiments using ORB-SLAM3 on the TUM RGB-D dataset [24]. Figure 2 presents the proposed method, which incorporates a bilateral filter, in comparison to the standard ORB-SLAM3 algorithm, as summarized in Table 3. The results demonstrate a substantial improvement in absolute pose error (APE), with a 39% reduction in APE root mean square error (RMSE) for the fr2/largeloop dataset. These findings are further illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Table 3.

APE with SE(3) Umeyama alignment (Unit: m).

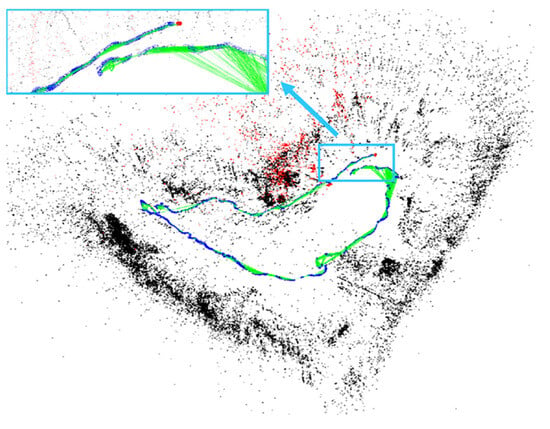

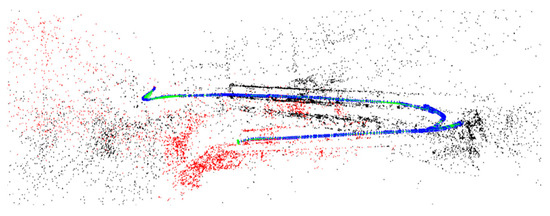

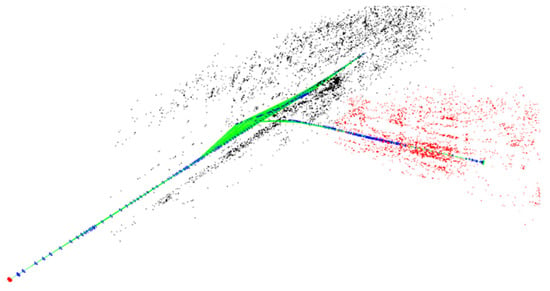

Figure 3.

Large drifts without optimization displayed by directly performing ORB-SLAM3 on the TUM fr2/largeloop dataset. Black points represent the static map points, while red points indicate active map points currently being tracked. This also applies to similar figures below.

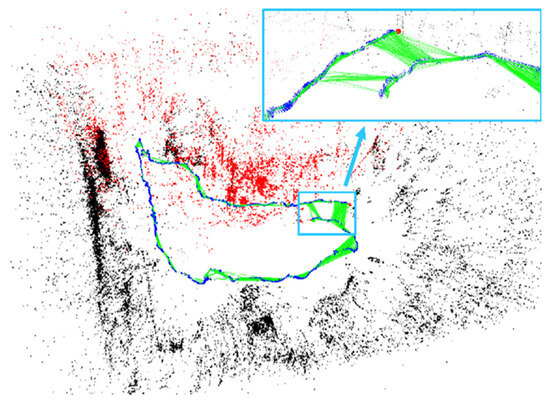

Figure 4.

Loop closing activated by performing our proposed method on the TUM fr2/largeloop dataset. The edges of current camera poses and several previously visited features become constrained.

3.2. Sparse and Dense Maps

The original source code of ORB-SLAM3, available on GitHub (https://github.com/UZ-SLAMLab/ORB_SLAM3, accessed on 1 March 2023), is based on a sparse map architecture referred to as the Atlas. To enhance its capabilities for storing and retrieving maps, we introduced several modifications. These adjustments allow the pre-built map to play a critical role in enabling real-time relocalization for navigation tasks. The sparse map is stored as a binary file with the extension *.osa. By integrating this pre-built Atlas into ORB-SLAM3, the system achieves reliable relocalization, even under subtle motions such as minor self-rotations of a mobile robot, thus effectively addressing the challenges posed by diverse indoor and outdoor environments.

To ensure the accuracy of the 3D map, we downsampled the depth images and aligned them using the poses calculated by the SLAM algorithm. Following the global reconstruction, point cloud filtering was applied to obtain a refined and usable 3D reconstruction [25].

In contrast to the sparse maps generated natively by ORB-SLAM3, we incorporated dense mapping into our framework by seamlessly integrating SurfelMeshing [26] into the real-time 3D reconstruction pipeline. SurfelMeshing is a well-established technique for online surfel-based mesh reconstruction, recognized for its versatility in real-time 3D reconstruction and rendering across extensive environments. The process comprises four primary stages: surfel reconstruction, surfel denoising, meshing, and remeshing.

The first stage involves generating an unstructured collection of surfels that represent visible surfaces, constructed from depth data acquired by RGB-D cameras. These surfels are then subjected to a rigorous regularization and blending process to reduce noise and address discontinuities at surface boundaries, thereby enhancing surfel denoising. The meshing phase follows, incorporating detailed neighbor searches and projecting the central surfel onto its tangent plane to construct a coherent mesh. Finally, the remeshing stage systematically removes outdated surfels and establishes new connections with neighboring elements, ensuring the continuity and accuracy of the reconstructed model.

SurfelMeshing provides numerous inherent advantages over traditional mesh reconstruction methodologies, establishing itself as a critical tool in the domains of real-time 3D mapping, autonomous navigation, and virtual reality. In our experiments, we utilize a depth camera to efficiently capture RGB-D data. In the subsequent sections of this paper, we present two illustrative case studies: one focusing on an indoor scenario and the other on an outdoor context. Our pipeline operates seamlessly, delivering high-quality 3D mapping results, accurately captured as the mobile robot navigates through dynamic environments. These results are vividly depicted in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8.

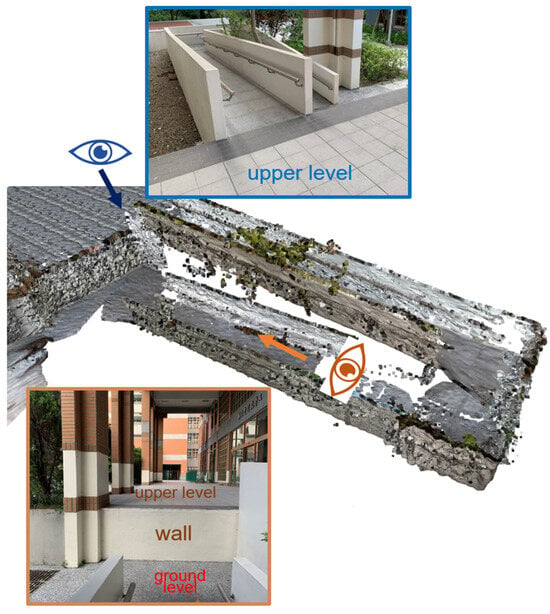

Figure 5.

The sparse map constructed outside the Building of Engineering Building at National Taiwan University (NTU).

Figure 6.

Mesh reconstruction outside the Building of Engineering Building at NTU.

Figure 7.

The sparse map is constructed from the third floor in the Building of Engineering Building at NTU.

Figure 8.

Mesh reconstruction on the third floor in the Building of Engineering Building at NTU.

6. Obstacle Avoidance

Obstacle avoidance constitutes a pivotal component of autonomous navigation, assuming heightened significance in dynamic environments, where the presence and configuration of obstacles can change rapidly. To ensure secure and efficient navigation, it is imperative to seamlessly incorporate real-time obstacle detection into the navigation framework.

6.1. Obstacle Detection from Depth Information

Helen et al. have introduced an innovative approach to obstacle detection, leveraging dense disparity images accumulated along image columns [30]. This approach entails the transformation of the disparity image into a U-disparity map (U-map) through the accumulation of disparity values along columns. The U-map serves as a fundamental tool for identifying objects and grouping them into distinct obstacles. The technique for detecting obstacles relies on U-V disparity maps [31], which partition the disparity image into two histograms: a U-map (accumulated along image columns) and a V-map (accumulated along image rows). This partitioning improves robustness against noise and inaccuracies in depth measurements. Obstacles are identified as connected components within the U-map and subsequently projected back into the world frame.

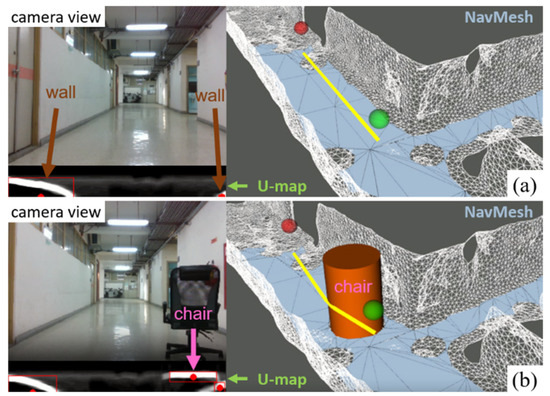

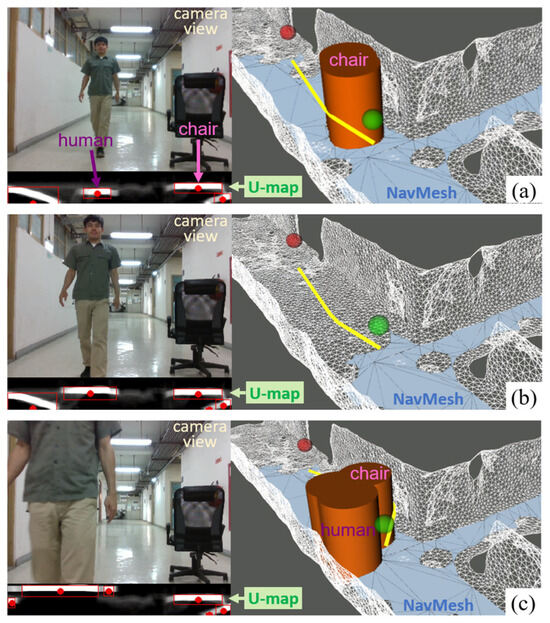

In dynamic environments, integrating obstacle detection into NavMesh-based navigation requires continuous path replanning to accommodate changing obstacles. Figure 15 illustrates a scenario where a static obstacle—a chair—blocks the robot’s original path. Upon detection, the NavMesh structure is updated to define new walkable areas, with the chair visualized as an orange column and the newly computed path represented by a yellow curve.

Figure 15.

The replanned path bypassing the additional static obstacle. In the original scenario (a), the known corridor is free of obstacles, allowing the robot, shown as the green point, to move directly toward the destination (red point). However, when a previously unknown static obstacle appears in the environment, the robot must update the map to include this new information and adjust its path accordingly. In (b), the algorithm generates a new, collision-free path to avoid the obstacle.

Dynamic obstacles also influence navigation performance. In Figure 16a, the robot successfully avoids a static obstacle; however, the introduction of a dynamic obstacle—a pedestrian—results in multiple obstructions, initially leaving no feasible path. This scenario triggers the clearance of prior obstacle configurations (Figure 16b), followed by NavMesh regeneration to accommodate the new environment. Finally, as shown in Figure 16c, a new path is planned based on the robot’s updated pose (green) and the positions of both static and dynamic obstacles.

Figure 16.

Path replanning for obstacle avoidance. In (a), the robot’s path (yellow) successfully avoids a static obstacle (a chair). However, the appearance of a human pedestrian creates multiple obstacles, resulting in an unfeasible path. This prompts the algorithm to clear the previous obstacle configurations, as shown in (b), and regenerate the NavMesh. Finally, (c) shows the replanned path, taking into account both the robot’s pose (green point) and the presence of static and dynamic obstacles.

6.2. Discussion and Limitations

In the context of our approach, it is assumed that all obstacles are situated at ground level. Consequently, the navigation mesh must be reconstructed to eliminate walkable areas blocked by these obstacles. While our mobile robot possesses a height of 0.98 m, allowing it to navigate through tunnels of similar dimensions, the situation changes when dealing with taller robots. If a robot’s height surpasses the maximum clearance of a tunnel, a collision becomes inevitable. It is worth noting that the upper structure of the tunnel is not originally situated on navigation meshes or closely connected to the walkable regions. Thus, for very tall robots or autonomous vehicles traversing tunnel-like structures, collision avoidance might be compromised. This limitation underscores the need for a comprehensive consideration of vertical obstacles in real-world scenarios.

Another limitation emanates from the design of our mobile robot. Situations may arise where the robot struggles to localize its position through visual SLAM due to a paucity of features for tracking. In such cases, our current mechanism necessitates the robot to backtrack to a prior state with observable environmental features to regain positional awareness. However, as no secondary camera is installed to capture the rearward view, backward motion could potentially lead to collisions in the presence of unforeseen dynamic obstacles. Thus, our future work should explore sensor fusion strategies, as the incorporation of additional sensors can augment obstacle detection capabilities, especially in the rearward direction.

This discussion on obstacle avoidance elucidates both the framework’s capabilities and its associated limitations, presenting a well-rounded perspective for readers and highlighting avenues for future research and refinement.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

In general, the typical algorithms employed in ORB-SLAM3, NavMesh generation, and U-map creation are referenced in [20], [5], and [30], respectively. ORB-SLAM3 computes visual odometry and, at a broader scale, includes loop detection within the SLAM framework. The Atlas map is a powerful tool for real-time positioning of robot agents, allowing for accurate navigation.

Using ORB-SLAM3, the SurfelMeshing algorithm reconstructs a 3D environment based on the visual odometry. Once we have a 3D mesh that simulates the real-world environment, we convert this mesh into a NavMesh. The above process generates two types of maps: the Atlas map and the NavMesh.

NavMesh is preferred for navigation instead of the original mesh because its data structure defines walkable areas. The Watershed Algorithm, applied through Recast Navigation, generates non-overlapping regions, making the walkable paths continuous. In contrast, the original 3D meshes are discontinuous, which complicates navigation.

Once we have both the Atlas and NavMesh, we can begin the navigation process. This includes two key tasks: path planning and obstacle avoidance. For path planning, we use the A* pathfinding algorithm on the NavMesh. A* is efficient in terms of computational time, especially when the NavMesh is optimized to define walkable areas. As shown in Table 4 and Table 5, the A* algorithm can compute the global path at real-world scales within a very short time. Furthermore, if the map contains mostly empty spaces with few complex objects, the number of nodes in the walkable areas can be minimized, further improving efficiency in our navigation process.

Regarding obstacle avoidance, the NavMesh is reconstructed whenever a dynamic obstacle is detected. Our obstacle detection method relies on U-V disparity maps, as detailed in [31]. The U-map is created by accumulating the disparity values along the columns of the image, while the V-map accumulates along the rows. Obstacles are typically characterized by a small number of disparity values, which are clearly visible in the U-map. In this map, all disparity values for a single object fall within the same range because the distance from the camera to the object remains constant.

Finally, the real-time performance of NavMesh generation has been validated on the commercial platform Unity 3D, where we also apply our NavMesh reconstruction using the same Recast Navigation system [5]. By detecting obstacles through the U-map, we can update the walkable areas and reconstruct the NavMesh in real time to accommodate dynamic changes in the environment.

The innovative 3D vision-based autonomous navigation system introduced in this research presents promising applications across a wide range of industries:

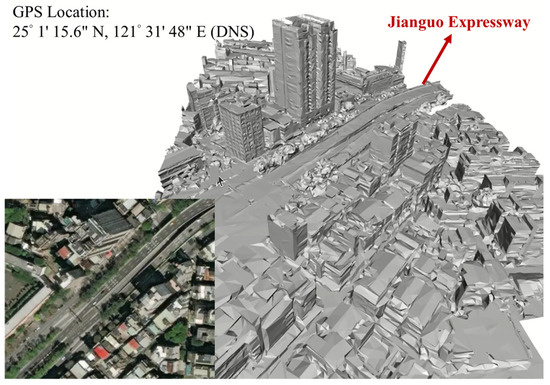

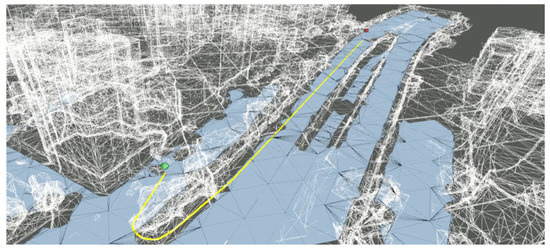

- Wide-Range Outdoor Navigation: The system offers transformative potential for autonomous vehicles, including self-driving cars, delivery robots, and other automated transport solutions. By enabling efficient, safe, and adaptable navigation in complex environments, it contributes significantly to advancing autonomous transportation. Furthermore, the research facilitates outdoor navigation in real-world, large-scale scenarios covered by wide-range GPS or networking. Leveraging services such as Google Maps for mesh data, the system can navigate complex urban environments with ease. For instance, Figure 17 illustrates mesh data depicting the Jianguo Expressway crossing several surface streets, while Figure 18 demonstrates a yellow navigation path displayed on NavMeshes, enabling movement from a lower-level street to the elevated Jianguo Expressway.

Figure 17. Mesh reconstruction downloaded from Google Maps.

Figure 17. Mesh reconstruction downloaded from Google Maps. Figure 18. A* pathfinding on a large-scale NavMesh converted from the mesh representation shown.

Figure 18. A* pathfinding on a large-scale NavMesh converted from the mesh representation shown. - Search and Rescue, Construction, and Disaster Response: The system’s adaptability to various terrains, including uneven surfaces and wheelchair ramps, makes it invaluable for challenging scenarios such as search and rescue missions, construction sites, and disaster response. Its ability to perform real-time navigation in complex environments addresses critical needs in these contexts. However, further investigation is required to evaluate its robustness under sensor noise, localization drift, and rapid environmental changes, which may affect its performance in highly dynamic scenarios. Future work will focus on assessing the system’s resilience to external disturbances, including varying lighting conditions, sensor occlusions, and mechanical wear, ensuring its reliability in real-world deployments.

- Virtual and Augmented Reality: The precise 3D mapping capabilities of the system extend its applications to virtual and augmented reality, facilitating the creation of immersive environments and enhancing augmented reality experiences. This connection between 3D perception and interactive applications further broadens the system’s potential impact beyond robotics. However, optimizing computational efficiency and real-time processing will be a key area of improvement, as faster and more efficient navigation is essential for both robotics and VR/AR applications.

This study makes significant contributions to the field of autonomous navigation for wheeled mobile robots. By presenting a real-time pipeline for 3D reconstruction using RGB-D cameras and implementing pathfinding algorithms in 3D space, we have advanced the state of the art in mobile robotics. The successful demonstration of robot navigation through navigation meshes (NavMeshes) offers a practical solution for interpretable 3D map-based navigation. Additionally, the integration of an RGB-D sensor enables moving object detection, ensuring effective collision avoidance. These advancements have the potential to substantially enhance the performance and reliability of autonomous vehicles and robotic systems.

Despite these achievements, several areas warrant further investigation and refinement. Future work will focus on expanding the evaluation metrics beyond navigation accuracy, incorporating energy efficiency, processing speed, and adaptability to different robot models to assess the system’s broader applicability. Additionally, while the current study primarily targets wheeled mobile robots, extending the system to other platforms, such as legged robots, will be an important direction to explore, requiring adaptations to different locomotion models. By addressing these aspects, we aim to enhance the system’s robustness and efficiency, broadening its applicability across various autonomous navigation scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-W.W. and H.-P.H.; Funding acquisition, H.-P.H.; Methodology, T.-W.W. and Y.-L.Z.; Project administration, H.-P.H.; Resources, H.-P.H.; Software, T.-W.W. and Y.-L.Z.; Supervision, H.-P.H.; Validation, T.-W.W. and Y.-L.Z.; Visualization, T.-W.W.; Writing—original draft, T.-W.W. and Y.-L.Z.; Writing—review and editing, T.-W.W., H.-P.H. and Y.-L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under NSTC 112-2221-E-002-149-MY3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This research is an extended version of our previous work presented at the 2024 National Conference on Mechanical Engineering of CSME [32].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gul, F.; Rahiman, W.; Nazli Alhady, S.S. A comprehensive study for robot navigation techniques. Cogent Eng. 2019, 6, 1632046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wu, T.; Zhou, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, J.; Li, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, A. SLAM, Path Planning Algorithm and Application Research of an Indoor Substation Wheeled Robot Navigation System. Electronics 2022, 11, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafnakaji, S.; Hajieghrary, H.; Teixeira, Q.; Bekiroglu, Y. Benchmarking local motion planners for navigation of mobile manipulators. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–20 January 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.S.; Mohd-Mokhtar, R.; Arshad, M.R. A Comprehensive Review of Coverage Path Planning in Robotics Using Classical and Heuristic Algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119310–119342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Ruan, N.; Shi, J.; Zhou, W. Deep Neural Network for 3D Shape Classification Based on Mesh Feature. Sensors 2022, 22, 7040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisetti, G.; Stachniss, C.; Burgard, W. Improved Techniques for Grid Mapping With Rao-Blackwellized Particle Filters. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2007, 23, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamkiewicz, M.; Chen, T.; Caccavale, A.; Gardner, R.; Culbertson, P.; Bohg, J.; Schwager, M. Vision-Only Robot Navigation in a Neural Radiance World. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 4606–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhisheng, Z.; Zhijie, X.; Min, D.; Meng, P.; Cen, J. Implementation and research on indoor mobile robot mapping and navigation based on RTAB-Map. In Proceedings of the 2022 28th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice (M2VIP), Nanjing, China, 16–18 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.E.; Nilsson, N.J.; Raphael, B. A Formal Basis for the Heuristic Determination of Minimum Cost Paths. IEEE Trans. Syst. Sci. Cybern. 1968, 4, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazem, Z.B.; Ince, R.; Dilibal, S. Joint Control Implementation of 4-DOF Robotic Arm Using Robot Operating System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Theoretical and Applied Computer Science and Engineering (ICTASCE), Ankara, Turkey, 29 September–1 October 2022; pp. 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Carsten, J.; Ferguson, D.; Stentz, A. 3D Field D: Improved Path Planning and Replanning in Three Dimensions. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Beijing, China, 9–15 October 2006; pp. 3381–3386. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, T.; Sellers, T.; Luo, C.; Carruth, D.W.; Bi, Z. Graph-based robot optimal path planning with bio-inspired algorithms. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2023, 3, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Shao, S.; Wang, T.; Yu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Cao, Z. Review of Autonomous Path Planning Algorithms for Mobile Robots. Drones 2023, 7, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Shi, P. Improvement of Dijkstra’s algorithm and its application in route planning. In Proceedings of the 2010 Seventh International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, Yantai, China, 10–12 August 2010; pp. 1901–1904. [Google Scholar]

- LaValle, S.M.; Kuffner, J.J. Rapidly-exploring random trees: Progress and prospects: Steven m. lavalle, iowa state university, a james j. kuffner, jr., university of tokyo, tokyo, japan. In Algorithmic and Computational Robotics; A K Peters/CRC Press: Natick, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, D.; Latombe, J.-C.; Kurniawati, H. On the Probabilistic Foundations of Probabilistic Roadmap Planning. In Robotics Research: Results of the 12th International Symposium ISRR, San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–15 October 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Pütz, S.; Wiemann, T.; Piening, M.K.; Hertzberg, J. Continuous Shortest Path Vector Field Navigation on 3D Triangular Meshes for Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Xi’an, China, 30 May–5 June 2021; pp. 2256–2263. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, J.L.; Hillebrand, A.; Geraerts, R. Annotating Traversable Gaps in Walkable Environments. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 3045–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, M.; Motoi, N. Local Path Planning: Dynamic Window Approach With Virtual Manipulators Considering Dynamic Obstacles. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17018–17029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, C.; Elvira, R.; Rodríguez, J.J.G.; Montiel, J.M.M.; Tardós, J.D. ORB-SLAM3: An Accurate Open-Source Library for Visual, Visual–Inertial, and Multimap SLAM. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2021, 37, 1874–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Singh, S. LOAM: Lidar Odometry and Mapping in Real-time. Robot. Sci. Syst. 2014, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, W.; Kohler, D.; Rapp, H.; Andor, D. Real-Time Loop Closure in 2D LIDAR SLAM. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–21 May 2016; pp. 1271–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornprobst, P.; Tumblin, J.; Durand, F. Bilateral Filtering: Theory and Applications. Found. Trends Comput. Graph. Vis. 2009, 4, 1–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, J.; Engelhard, N.; Endres, F.; Burgard, W.; Cremers, D. A benchmark for the evaluation of RGB-D SLAM systems. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 573–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-L.; Hong, Y.-T.; Huang, H.-P. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation between Visual SLAM and LiDAR SLAM for Mobile Robots: Theories and Experiments. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöps, T.; Sattler, T.; Pollefeys, M. SurfelMeshing: Online Surfel-Based Mesh Reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 2494–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haumont, D.; Debeir, O.; Sillion, F. Volumetric Cell-and-Portal Generation. Comput. Graph. Forum 2003, 22, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, D.H.; Peucker, T.K. Algorithms for the Reduction of the Number of Points Required to Represent a Digitized Line or Its Caricature. Cartographica 1973, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.L.; Huang, H.P.; Chen, T.L.; Chiang, P.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Yeh, J.H.; Huang, C.H.; Lin, J.F.; Weng, W.T. A Smart Sterilization Robot System with Chlorine Dioxide for Spray Disinfection. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 22047–22057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleynikova, H.; Honegger, D.; Pollefeys, M. Reactive avoidance using embedded stereo vision for MAV flight. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Labayrade, R.; Aubert, D.; Tarel, J. Real time obstacle detection in stereovision on non flat road geometry through “v-disparity” representation. In Proceedings of the Intelligent Vehicle Symposium, 2002, IEEE, Versailles, France, 17–21 June 2002; Volume 642, pp. 646–651. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.W.; Huang, H.P.; Zhao, Y.L. Vision-based Autonomous Robot Navigation in 3D Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 National Conference on Mechanical Engineering of CSME, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 15–16 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).