Abstract

It is hard to envision a modern world where information technology does not facilitate daily tasks, including learning and teaching. This paper explores the use of virtual reality (VR) simulations in chemistry education, focusing on how immersive VR environments can enhance the learning experience for students. With chemistry often posing challenges due to its abstract and complex concepts, VR technology allows for a more interactive and visual approach, enabling students to visualize molecular structures, chemical reactions, and laboratory procedures. The study concludes that virtual reality (VR) simulations are crucial in modernizing chemistry education by making abstract and complex concepts more interactive and visual. Through a comprehensive analysis of current VR tools and simulations, the article discusses their strengths and limitations, providing a critical overview of the role of VR in modernizing chemistry education. The findings suggest that VR simulations can significantly improve students’ engagement with and understanding of complex chemistry concepts. Also, the results suggests that integrating VR into chemistry education can revolutionize traditional teaching methods, providing a more immersive and engaging learning experience.

1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) technology is becoming increasingly integrated into education, particularly for its potential to create immersive, interactive learning environments. VR enables students to interact with content more practically and intuitively, helping to make complex or abstract ideas easier to understand [1,2,3,4]. The shift to remote instruction during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted both the potential and the limitations of VR laboratories. Several studies report that virtual labs can reduce safety risks, lower material costs, and prepare students for hands-on work by allowing them to rehearse procedures in a simulated environment. At the same time, learners and instructors consistently emphasize that VR should complement, rather than replace, physical laboratory experiences [5,6]. The application of VR in education spans various fields, but it has shown particular promise in the sciences, where complex concepts can benefit from dynamic and visual representation [7,8]. In the context of chemistry education, VR provides an innovative platform to simulate chemical processes and reactions, which can be challenging to observe or conduct in real-world classrooms due to safety concerns, cost, or technical limitations [9]. Chemistry, which often requires students to grasp abstract ideas and conceptualize molecular interactions, benefits significantly from VR simulations, providing visual and experiential learning opportunities beyond the traditional textbook [10]. Through VR simulations, students can visualize difficult-to-calculate molecular bonds and improve their understanding of the subject [11]. This immersive experience helps make the subject matter more engaging and supports active learning, where students can interact with the content and explore outcomes based on different variables [12]. In research, VR simulations can help with conducting various experiments, including protein–ligand docking [13,14,15,16,17,18] to discover new drug-like compounds, artificial intelligence (AI) and quantitative structure–activity modeling [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] to find various relationships to biological activities or physico-chemical properties, and remote operation of robotic equipment in chemical labs [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. While many studies have broadly demonstrated the benefits of VR for STEM learning, much less attention has been paid to systematically comparing the specific VR simulations that chemistry educators can adopt in practice.

Recent studies have shown that explaining the methane molecule in a virtual world has been found to increase student understanding and, consequently, motivation [4,37,38,39]. The material can be explained and shown using an interactive online panel. Therefore, not every student needs to own or wear VR glasses. In this context, if a teacher wants all the students in a group to conduct laboratory work simultaneously in one room, all students need to wear VR glasses; however, with VR simulation it is not necessary to be in a real chemistry laboratory to learn specific chemistry concepts and lab skills. One of the valuable aspects of using VR simulations in chemistry is that a person can conduct a chemical experiment freely without fear of being injured in a virtual laboratory environment [40]. As a result, the student is not afraid of the risk that would be involved by performing the chemistry experiment in the lab, and therefore, the student’s anxiety is reduced [41]. It is clear that VR technology can adequately prepare students to perform lab work in a safe environment, but of course, it cannot completely replace real experimental conditions [39]. It is important to mention that virtual lab applications have different effects on students. However, empirical studies report heterogeneity in students’ responses to VR, with some learners highlighting increased effectiveness and usefulness [4], while others point out that they do not know how to use information technology effectively and that real physics or chemistry labs are better than VR, because VR does not involve the senses of touch or smell [42]. Throughout this manuscript, the term “VR simulations” refers consistently to all virtual reality-based educational platforms examined in this study.

Beyond immediate engagement, recent research suggests that VR can contribute to more long-term learning gains, particularly regarding retention and the transfer of conceptual understanding. Thus, VR simulations helps students better understand such important chemistry topics as molecular structures and chemical reactions [43]. To realize the full potential of VR, VR simulations should be complemented by traditional laboratory methods, creating a well-rounded and effective learning experience in chemistry [43]. In one study, worksheet and quiz score analysis suggested that student performance fluctuates more over time than between the two teaching methods [5]. However, it has been shown that students who participate in the VR simulations demonstrate better long-term retention, as evidenced by their quiz performance at the end of the semester [4,44]. At the same time, work on virtual and metaverse-based learning environments emphasizes that such gains depend strongly on careful pedagogical design, scaffolding, and alignment with learning objectives [45]. In addition, the findings of another study indicated that VR simulations had a more substantial impact on students’ ability to recall virtual lab experience compared to the traditional lab setting [46]. In this context, the selection of virtual reality software for teaching plays a crucial role in shaping the knowledge and skills of future chemistry students.

Next, it is important to explore various available VR simulations for teaching chemistry. In the following sections, we discuss the effectiveness of VR simulations in chemistry education through a comparative analysis of different tools. We evaluate how these simulation tools improve learning outcomes, increase student engagement, and foster a deeper understanding of chemical concepts. Additionally, we will compare the challenges and potential benefits of integrating VR technology into existing chemistry curricula. In this review, we focus on six VR simulations that are either already in use or readily adaptable for chemistry education: VR Chemistry Lab (Elliot Hu-Au, version 0.9.8), Chemistry Lab VR (nkanyi73, version 1.0.3), MIMBUS Chemistry (version 1.8.2.251010001), Nanome (Steve McCloskey, version 1.24.6), VR Chemistry Lab Russian (version 1.0.0), and Gravity Sketch (version 6.4). MIMBUS Chemistry, created in collaboration with CNAM, is a pedagogical solution intended to impact students’ training positively.

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature and Software Search Strategy

This review aimed to identify and examine virtual reality tools currently available for chemistry education. It also sought to understand how these tools are used and evaluated in educational settings. Therefore, the search strategy focused on finding studies, virtual reality platforms, simulations, and software relevant to chemistry education. To compile this review, we conducted a thorough search of SciFinder, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. We also reviewed publicly accessible websites of VR software developers specializing in chemistry. Keyword selection was based on SciFinder search analytics and recent literature on virtual reality in education. The search included terms such as “virtual reality software for chemistry,” “virtual reality chemistry lab,” “immersive chemical simulation,” “3D molecular simulation in virtual reality,” “virtual chemistry lab software,” and “interactive chemical reaction simulation.” We limited the search to English-language publications and software released or documented through 2025, focusing on tools that have been used or evaluated in real classroom environments.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Since the review aimed to compare specific virtual reality tools rather than summarize general trends in the literature, the inclusion criteria focused on the tools’ characteristics. Tools were included if they were publicly available, used in published chemistry research, or sufficiently documented to allow examination of their design and capabilities. We also included empirical studies and usability evaluations that showed how these tools influence students’ understanding, engagement, or laboratory skills.

VR environments were excluded from the review if they did not meet the intended scope of chemistry education. This included cases where the platform functioned solely as an augmented reality tool, or where the software was primarily an engineering or game prototype without chemistry content, or where VR applications were developed for other scientific fields if chemistry was not a significant component of the experience. Based on these considerations and the availability of detailed documentation, six VR simulations were retained for in-depth comparative analysis.

2.3. Screening and Selection Procedure

In this study, the analysis focused specifically on six VR simulations that are already commonly referenced or used in chemistry education: VR Chemistry Lab (Elliot Hu-Au), Chemistry Lab VR (nkanyi73), MIMBUS Chemistry, Nanome, VR Chemistry Lab Russian, and Gravity Sketch. These programs were selected because they are accessible and documented, and represent different approaches to virtual chemistry learning—ranging from molecular visualization to full laboratory simulations. The screening process did not aim to exhaustively identify all available VR software, but rather, to gather the most relevant information about these six tools from academic publications, developer documentation, and publicly available descriptions. For each program, we reviewed its educational purpose, design features, and chemistry-specific capabilities. When available, we also examined peer-reviewed studies or conference reports describing how the tool was used in classroom or laboratory settings. Full-text materials were reviewed to confirm that each program meaningfully supported chemistry learning and provided enough information for a comparative evaluation. Duplicate descriptions, promotional copies, or repeated summaries of the same tool were removed. This focused approach ensured that the review stayed clear and organized while still allowing for a detailed comparison of the six selected platforms.

2.4. Quality Assessment

Since the goal of this review is to compare a specific set of VR simulations, the quality assessment focused on evaluating their pedagogical value and technical features rather than solely on research methodology. For each tool, we looked at how clearly its educational goals were communicated and how well its instructional design matched established principles in chemistry education, such as visualization, inquiry, and conceptual understanding. We also assessed practical aspects of the VR environments, including the accuracy of chemical representations, the level of interactivity and immersion provided, and how effectively students can manipulate molecules or perform virtual lab tasks. Usability, accessibility, and hardware needs were also considered, since these factors impact how easily the tools can be integrated into real classroom settings. When available, we reviewed empirical evidence related to learning outcomes, student engagement, or skill development. Programs with limited documentation or unclear pedagogical positioning were still included but discussed with caution. This approach helped us provide a fair and realistic comparison of the six VR simulations examined in this review.

2.5. Evaluation Framework

To ensure a transparent and replicable comparison of VR simulations, we operationalized five analytical dimensions: Chemical Fidelity, Interactivity and Immersion, Pedagogical Alignment, Practical Applicability, and Evidence Base—into a structured scoring rubric. Each dimension was evaluated using a three-level scale (High = 3; Medium = 2; Low = 1) (Table 1). Scores were assigned based on documented chemical functionality, interface interactivity, alignment with chemistry learning outcomes, hardware and usability requirements, and availability of peer-reviewed validation.

Table 1.

Scoring rubric for evaluating VR chemistry simulations.

3. Virtual Reality Simulation in Chemistry Education

Currently, VR simulations are used in almost all aspects of chemistry. Virtual reality can be applied not only in primary schools and higher education institutions but also in secondary schools. The four characteristics of Meaningful Chemistry Education (MCE)—daily life context, the “need-to-know” principle, student involvement, and the macro−micro connection—are integrated into immersive virtual reality (IVR) design [3]. One of the studies on the application of VR simulations in chemistry education aims to investigate the effectiveness of a sustainable innovation learning (SIL) model implemented through a virtual reality (VR) chemistry laboratory [47]. This model focuses on improving students’ academic achievements, learning motivation, and understanding of chemical concepts. The research demonstrated how experiential learning, self-efficacy, and cognitive load influence students’ motivation and ability to transform practical experiences into knowledge. Additionally, VR systems in chemistry education are a safer, more cost-effective, and accessible alternative to traditional laboratory experiments. The development of three-dimensional (3D) visualization tools for teaching chemistry through VR focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of VR-based 3D tools as a learning resource for high school students, particularly in teaching material on reaction rates [48].

AVATAR VR technology opens up new possibilities in chemistry education and research, allowing students to learn chemical processes more effectively and interactively. AVATAR (Advanced Virtual Approach to Topological Analysis of Reactivity) is based on virtual reality (VR) technology and enables immersive exploration of potential energy landscapes. This technology offers new opportunities for studying chemical processes [49].

VR in chemistry is widely applied for both inorganic chemistry and organic chemistry. A new virtual reality learning system called the VR Multisensory Classroom (VRMC) was introduced and evaluated in an organic chemistry class in [50]. This system enhances organic chemistry education through immersive, multisensory, and haptic experiences. The VRMC allows students to interact with molecular structures using natural hand movements and haptic feedback, enabling them to build and manipulate hydrocarbon molecules in a virtual environment. As a result, students showed increased interest and motivation in organic chemistry and better understood the subject. The study highlights the advantages of “learning by doing” and demonstrates how the VRMC can transform chemistry education by providing a safe, engaging, and effective platform for exploring abstract topics. Additionally, it identifies future development directions, such as expanding the educational content and integrating different levels of gamification to enhance the system further.

Molecular Rift technology creates new opportunities in chemical and pharmaceutical research. Using Oculus Rift and MS Kinect v2 sensors, this tool allows users to study molecular systems, such as protein–ligand complexes, in an interactive 3D environment. With the help of VR (virtual reality) technology, users can immerse themselves inside a protein, taking drug design processes to a new level. Molecular Rift is user-friendly and efficient, enabling users to adapt to the latest interactive system quickly. This open-source code offers expansion and customization options. The technology provides users with an effective way to study molecules and their interactions [51].

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, many educational institutions moved their courses online in the spring of 2020. One study focuses on virtual reality (VR) organic chemistry laboratory experiences adapted for online learning. However, several technical challenges arose due to the large class size, such as the inability to provide VR headsets for all students, and students lacking reliable internet access for streaming videos online. Additionally, psychological challenges emerged among students due to the global pandemic and the rapid shift from in-person instruction to online learning [52]. In another study, using VR to simulate laboratory conditions showed VR’s potential as a safe, accessible, and effective educational tool in experimental chemistry [53].

The feasibility and effectiveness of replacing a traditional instrumentation-based organic chemistry lab with VR are evaluated in another experiment [46]. This study focused on a VR experience to teach students to use an infrared spectrometer and analyze an unknown structure from the resulting infrared spectrum. The research compares the learning outcomes of students who used the VR simulations to those of students who completed the same experiment in a traditional lab setting. The study assesses both short- and long-term recall of the material and explores the potential of VR simulations for distance education and accessibility.

4. Advantages of VR Simulations in Chemical Education

Through VR technology and its educational materials, students gain equal access to the instructor’s knowledge and expertise. VR simulations create a more impartial and accessible learning environment for under-represented groups (in terms of race, gender, and ethnicity). This approach helps improve equity and learning opportunities among students. In one study, students positively evaluated VR materials in terms of their impartiality, convenience, and the opportunity for independent learning [54]. The researchers emphasized the positive impact of VR simulation on student motivation and learning outcomes, especially in making complex chemical concepts more understandable through interactive simulations. Furthermore, there is potential for expanding interactive molecular dynamics in virtual reality (iMD-VR) to other courses and educational environments, such as organic chemistry, biochemistry, and physical chemistry, as well as its application in K-12 education [38].

VR simulations were integrated into an immersive chemistry lab attended by undergraduate students in a biochemistry course. This practice was intended to help improve students’ spatial recognition of protein structures and encourage their active participation in 3D chemistry experiments. The research focused on the effectiveness of a VR-based chemistry lab at Harvard University, deployed for over 200 undergraduate students using Oculus Quest VR simulation. This work evaluated students’ learning experiences, perceptions, and self-reported outcomes, as well as analyzing how VR technology offers opportunities for remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic [55]. Also, in another study, the effectiveness of combining VR and asymmetric collaborative learning (CL) methods was explored. This study analyzed the impact of two teaching approaches based on a VR program designed to study biodiesel synthesis in a chemistry course. In the first approach, students worked individually within the VR environment, while in the second, they supported each other and learned collaboratively in an asymmetrical manner. The findings showed that collaborative learning produced better results in acquiring theoretical knowledge than individual learning, but individual learning was superior for developing practical skills. The collaborative approach reduced the mental load on students, enabling them to grasp theoretical concepts better. Overall, the combination of VR and CL yields good learning outcomes for theoretical materials, but for practical training, students benefit more when they have greater exposure to VR technology [56]. In addition, several studies focus on designing an immersive VR environment that utilizes game-based learning, learning analytics, and assessment methods to enhance VR training effectiveness [57].

Another area where VR simulation is applied is computational chemistry. Research in this field explored how VR simulation enhances students’ understanding by enabling them to analyze molecules and atomic structures more profoundly and intuitively, especially when collecting and analyzing chemical data and nuclear levels, and to increase students’ interest in chemistry. Furthermore, the research highlighted how virtual chemistry laboratories improve students’ abilities, versatility, and understanding of chemical mechanisms and molecular properties [58].

5. Challenges in Implementing VR Applications for Chemistry Education

The proliferation of VR simulations is steadily increasing. One of the most widely used simulations is MEL science. One study determined that by implementing MEL Chemistry VR lessons in a classroom for first-year undergraduate students, it helped students better understand chemistry concepts [59]. Connections have been established throughout this process between macroscopic and submicroscopic components and between representational and atomic structures. Furthermore, studies have investigated how immersive VR experiences can positively influence student performance. In one study, students who used VR simulation showed better self-control, and those who initially felt anxious reported feeling more at ease by the end of the lab. These findings suggest that VR simulations can benefit higher education, particularly when distance learning is necessary or it is financially challenging to implement real laboratory experiences [60]. In one study, the CAVETM system motivated students to learn by comparing two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) chemical animations. Three-dimensional chemical animations in a fully immersive VR environment help students understand molecular structures and their changes during chemical reactions and how this compares to 2D animations. Additionally, this technology overcomes the limitations of human vision and makes learning chemistry more engaging and interactive [61]. The application of VR technologies also extends to nuclear chemistry and radiochemistry, because it helps students to safely learn these experimentally unsafe topics as well. In these chemistry topics, the use of VR simulation addresses issues such as the limitations of student, experimental safety concerns, and high research costs. VR simulation enhances the learning experience for these topics for a broader audience beyond chemistry majors, improves teacher–student interaction, and increases students’ learning confidence and satisfaction, in addition to learning the basics of nuclear chemistry and radiochemistry. Therefore, VR in this case helps solve traditional teaching problems, such as high equipment costs, limited participation opportunities, and dangerous chemical experiments, especially chemical reactions with radioactive compounds [62].

A study found that the development and evaluation of a Virtual Reality System (VRS) for teaching acid–base titration provides students with hands-on experience in a simulated chemistry laboratory, enabling them to practice and refine their skills before transitioning to a physical wet lab [63]. In this research, the authors assessed the system’s effectiveness in enhancing students’ understanding of, interaction with, and learning outcomes in the titration process. Additionally, the study explores the potential of the virtual laboratory as an alternative to physical laboratories in cases where resources or equipment are limited. The avatar-shell simulator for conducting volumetric chemistry experiments helps students develop titration skills using accurate laboratory apparatus, but without the need for actual chemicals; instead, ordinary water is used. The system consists of two modules: the administrator module, which allows teachers to configure the experiment with the correct molarity of the solution, and the simulator module, where students perform the volumetric analysis. The avatar-shell simulator module is equipped with a highly sensitive weight sensor that connects to the administrator module, verifying the accuracy of each titration [64].

The integration of VR simulation in chemical safety training for experimental laboratory and industrial settings is increasingly recognized as crucial. This involves exploring how VR can enhance human performance, facilitate knowledge acquisition, and bridge the gap between theoretical learning and practical application while addressing safety challenges. Several publications in the field underscore the need for systematic evaluation of VR training effectiveness and suggest incorporating physiological sensors to assess cognitive factors such as stress and workload [65].

6. Comparative Analysis of VR Applications in Chemistry Education

To move beyond a purely descriptive comparison, we evaluated each tool across five analytical dimensions derived from previous research on VR in STEM education: (1) Chemical Fidelity (the accuracy and depth of representation of chemical processes), (2) Interactivity and Immersion (the extent and fluidity of user interactions in VR), (3) Pedagogical Alignment (how well it aligns with chemistry learning objectives, such as macro- and micro-relationships and inquiry-based learning), (4) Practical Applicability (hardware requirements, licensing, ease of installation), and (5) Evidence Base (the number and quality of peer-reviewed studies documenting learning outcomes or user experiences). Each dimension was qualitatively rated on a three-point scale (Low, Medium, High) based on published empirical studies, developer documentation, and training reports, which are summarized in Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5.

Over the past few decades, several VR lab simulation tools have been developed to enhance chemical education by providing an interactive, safe, and engaging learning environment. Below is an overview of the history and development of key VR chemistry simulation tools [66]. The six most used simulation tools were selected for comparison. Table 2 below lists the main differences between these simulations.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of VR simulation tools for chemistry education.

The simulation tools were chosen according to the following criteria:

Popularity and Accessibility: The degree to which the simulation tools are widely recognized and accessible to educators and students.

Content Coverage: The ability of each simulation tool to comprehensively address key chemical concepts and topics.

Interactivity: The extent to which the simulation tool allows users to actively engage with the content and explore chemical phenomena.

VR Immersion: The level of virtual reality integration enabling a more immersive learning experience.

Ease of Use: The simplicity of the user interface and the technical skills required to operate the simulation tool effectively.

Users can experience VR simulation in chemistry using a VR device such as Oculus Quest. VR simulations in chemistry allow students to interactively engage in complex processes by enabling an immersive and innovative approach during learning [73]. VR simulation gives us the possibility to interact with the external environment in the virtual world. In the virtual world, users can change their location, touch objects around them, and change the object’s position [64].

Benefits of using VR simulations in chemistry:

Immersive Learning Experience: Studies have shown that immersive environments enhance students’ understanding of abstract concepts by providing a more engaging and hands-on learning experience [74].

To evaluate the immersive learning potential of the selected VR simulations, we considered several qualitative criteria, including the following:

Graphics and Visual Details: The quality and realism of the visuals determine how effectively a simulation can immerse users in the virtual environment.

Interactivity Features: The extent to which users can meaningfully and logically interact with objects or the environment within the simulation.

Language Adaptability: For example, VR Chemistry Lab (Russian) is specifically designed for Russian-speaking users, which limits its accessibility and adaptability for a global audience.

Range of Features: The availability of advanced experiments, collaborative tools, and flexibility for different levels of chemistry education.

Student Engagement and User Experience: Feedback from learners and the simulation’s ability to motivate and sustain interest in learning.

Safe and Controlled Environments: The positive side of VR simulations is the ability to conduct experiments in a risk-free environment. VR enables students to safely experiment with hazardous chemicals and reactions without the safety concerns or high costs associated with real-life laboratory experiments. According to Dede (2009), VR simulations in education allow for the simulation of dangerous or complex processes that would otherwise be inaccessible in physical classrooms [75]. Table 3 below compares four simulations according to safety compliance. Nanome and Gravity Sketch simulation tools mainly explain molecules’ chemical structure and properties. The reaction cannot be performed using these simulations. The chemical can be loaded into a flask and shown to the user, but two substances cannot be added to each other. Therefore, using these software programs to explain molecules’ physical and chemical properties is appropriate.

Table 3.

Safety and security comparison of VR chemistry simulations.

This table outlines the safety and security protocols of different VR chemistry simulations, emphasizing variations in required attire, safety procedures, and responses to spills.

6.1. The VR Chemistry Lab

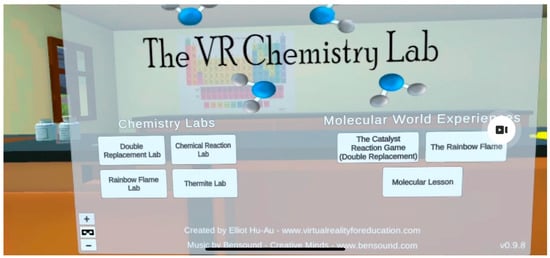

The VR Chemistry Lab provides a general-chemistry virtual laboratory where students carry out standard experiments (e.g., precipitation, thermite, and molecular lessons) in a head-mounted display environment. Its main strength is the explicit connection between macroscopic lab procedures and molecular-level visualizations, which supports conceptual understanding. However, the number of built-in experiments is limited, and the platform requires dedicated VR hardware (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

User interface of VR Chemistry Lab.

6.2. Chemistry Lab VR

Chemistry Lab VR focuses on guided wet-lab procedures such as qualitative analysis and basic synthesis in a realistic virtual laboratory. It offers a structured sequence of tasks with clear instructions, making it well-suited for introductory training and for students who are new to laboratory work. Its chemistry content remains largely procedural, with relatively little emphasis on molecular-level visualization or open-ended inquiry (Figure 2.).

Figure 2.

User interface of Chemistry Lab VR.

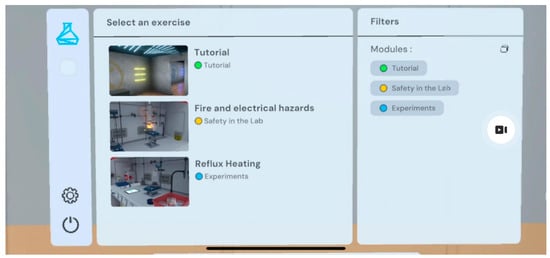

6.3. MIMBUS Chemistry

MIMBUS Chemistry is primarily a safety- and procedure-oriented VR system used in vocational and industrial training. It emphasizes correct handling of equipment, hazard identification, and adherence to laboratory protocols rather than detailed molecular content. This makes it highly valuable for occupational training and chemical safety courses, but less suitable for teaching reaction mechanisms or abstract chemical concepts (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

User interface of MIMBUS Chemistry Simulation.

6.4. Nanome

Nanome is an immersive molecular visualization and design environment that allows users to build, manipulate, and analyze three-dimensional structures, including biomolecules and drug-like compounds (Figure 4). Its pedagogical value lies in supporting spatial reasoning, structure–property analysis, and collaborative exploration of complex molecular systems. In chemistry courses, Nanome is typically used to examine stereochemistry, molecular geometry, and bonding patterns rather than to simulate laboratory workflows. As the platform does not model chemical reactions or procedural experiments, it functions best as a complement to virtual wet-lab simulations rather than a replacement for them [76].

Figure 4.

User interface of Nanome Molecular Design.

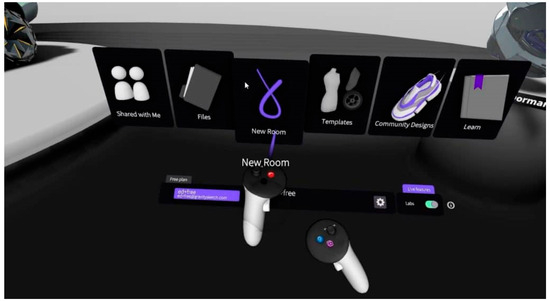

6.5. Gravity Sketch

Gravity Sketch is a general-purpose 3D modeling tool that can be repurposed for chemistry to construct and inspect spatial models of molecules, reaction coordinates, or apparatus layouts (Figure 5). It offers a flexible workspace for exploring symmetry, geometry, and spatial relationships that are difficult to convey in 2D. However, it lacks chemistry-specific rules and representations, so educators must design tasks and materials themselves [77].

Figure 5.

User interface of Gravity Sketch.

6.6. VR Chemistry Lab (In Russian)

The Russian version of the VR Chemistry Lab localizes the original platform for Russian-speaking students and institutions by providing a translated user interface and adapted instructional content. The simulation environment supports qualitative experiments primarily in inorganic and analytical chemistry, offering task-based activities. Learners follow instructions, perform virtual procedures, and receive automated feedback. Although widely used in Russian educational settings, its functionality remains limited to a narrow set of general chemistry topics, and organic reactions are not yet implemented. As illustrated in Figure 6, all interface elements and task descriptions are presented entirely in Russian. This enhances accessibility for local users but restricts broader international adoption.

Figure 6.

User interface of VR Chemistry Lab (in Russian).

7. Theoretical Frameworks and Pedagogical Approaches in VR-Based Chemistry

The advancements in computer graphics hardware and visualization software have also been analyzed, with researchers examining how these technologies enhance scientific visualization and data exploration in chemistry. The role of immersive environments, where chemists can interact with data objects in real time within a 3D space, is particularly emphasized, as this helps understand and efficiently manage complex datasets [78]. The integration of VR technology with artificial intelligence (AI) has been explored, in particular, for developing STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics) education. This will undoubtedly significantly improve modern education techniques [79]. A web-based virtual learning environment specifically designed for the simulation of chemical experiments, particularly volumetric analysis, has been presented. The proposed application has been found to utilize advancements in web and VR technologies to create realistic, interactive, and immersive simulations that resemble the conditions of a real chemical laboratory [80,81]. A study involving 387 participants investigated the effectiveness of using the 3D virtual world Second Life (SL) to enhance the understanding of the 3D nature of molecules in a virtual environment. These participants completed activities either in a 3D virtual environment (SL) or using 2D images. The results revealed that using VR in chemistry helps students, improves spatial understanding, and enhances academic outcomes through immersive and interactive experiences [82].

One VR simulation tool is Manta, an immersive molecular simulation platform integrated with VR. One study examines the potential of Manta as an interactive learning platform and in enabling students to study molecular structures and chemical reactions in real time. The research explicitly assesses Manta’s effectiveness in teaching hydrogen combustion reactions through classroom experiments conducted by undergraduate and graduate students. Positive feedback from students is presented in the study, suggesting that Manta enhances the understanding of molecular dynamics and improves the learning experience compared to traditional methods. Additionally, the article discusses how Manta can support teaching various chemistry concepts, such as organic and catalytic reactions. It highlights the broader significance of VR simulations in modern educational reforms, particularly in higher education [43]. One of the works that provides an overview of the use of augmented and immersive virtual reality (IVR) technologies in teaching chemistry at the high school and college levels aims to emphasize that the future of education will require the integration of these technologies and that these technologies are necessary to increase student engagement, particularly in chemistry. The work also highlights the potential of online education, where students can learn more independently. It explores how augmented reality and IVR projects, supported by 3D interfaces, haptic feedback, and immersive display technologies, help visualize complex chemistry topics, such as molecular structures, chemical bonding, and intermolecular interactions [83].

Additionally, a paper discussed the opportunities and challenges of incorporating VR simulation into chemical and biochemical engineering education, highlighting the importance of integrating VR with mathematical models and the need to develop advanced immersive learning applications. The paper also emphasizes the necessity of developing new methodologies to assess the educational impact of VR-based learning and exploring the social and economic implications of adopting VR simulations in education. Furthermore, the work reviews the current state of VR simulations in chemical engineering education, identifies opportunities and challenges in technology, pedagogy, and socio-economics, and provides recommendations for future research [84]. Using 3D models is appropriate to enhance students’ ability to visualize the three-dimensional shapes of molecules. It is worth noting that VR can effectively facilitate students’ acquisition of knowledge and enrich their learning experiences in molecular geometry. It is important to train future chemistry teachers to use this technology effectively. This will help them provide feedback, foster collaboration, and make decisions when developing instructional materials [85,86].

Thus, Michigan’s Department of Chemical Engineering have developed a technology that helps students study processes related to chemical reactors and catalysts. This technology is designed to engage students in practical exercises in chemical engineering and make the teaching process more effective. It helps educators explain scientific processes more clearly and gives students a more effective way to learn through hands-on activities [87,88,89]. In addition, a study showed that the ability of students who used VR to apply the knowledge they had gained was enhanced. Students found VR to be a great tool that helped them complete chemistry topics and lab activities. However, the study showed that students paid less attention to cleanliness and safety rules when using VR [68]. Studying the effectiveness of integrating a VR world molecular intervention into virtual reality laboratory simulations is crucial for learning chemistry concepts. A study examined the impact of different levels of embodiment (Traditional and VR) and intervention timings (Pre-lab or Integrated) on student learning. The research aimed to determine whether integrating VR interventions enhances the understanding of abstract chemistry concepts and compare the learning outcomes between physical manipulatives and VR-based experiences regarding students’ ability to visualize and comprehend molecular structures [67].

Beyond individual VR headsets and apps, recent research increasingly examines immersive chemistry learning within the larger concept of an educational metaverse. Ng describes the metaverse as a robust, interconnected network of 3D virtual spaces where presence, interaction, and the community of researchers can be sustained across all platforms and devices, opening new opportunities for collaborative laboratory- and problem-based learning [45]. Similarly, Lo et al.’s study demonstrates how virtual worlds can support self-directed exploration of mathematical and scientific concepts, which influences how chemistry educators develop locus-like problems related to molecular motion and reaction pathways [2]. Incorporating chemistry-specific VR simulations into such metaverse-like systems is a promising direction, but it also raises open questions regarding faculty organization, assessment, and professional development.

8. Future Directions in VR for Chemistry Education

When discussing student motivation, it was noted that virtual laboratories did not significantly enhance students’ motivation, and the reasons for this have not been thoroughly investigated. However, future work could explore how to design virtual laboratories that balance realism, engagement, and efficiency [90,91]. One study examined the acceptance and usefulness of VR technology in chemical engineering and industrial sectors for education and training. It analyzed the perceptions of chemical engineering students and professionals towards VR games and simulations. The study results show that VR technology can be helpful in education and safety training within the chemical engineering and industrial fields. However, students had some reservations and concerns about the technology. On the other hand, professionals were more supportive of this technology, advocating for its integration into future educational programs [92].

Interactivity and Engagement: VR simulations offer a level of interactivity that traditional 2D learning resources cannot match. Unlike textbooks or videos, VR allows students to actively participate in experiments, adjust variables, and observe the real-time consequences of their actions [93].

Realistic Simulation of Chemical Reactions: VR simulations in chemistry allow students to observe chemical reactions at the molecular and atomic levels. Students can see how molecules interact, break apart, and form new compounds, offering a deeper understanding of chemical dynamics and reaction mechanisms. It is impossible to create new products using only simulations. Studies have shown that the virtual chemistry laboratory is useful for scientific and technological development [94].

Accessible Learning Opportunities: VR-based chemistry education makes learning more accessible by removing geographic and physical barriers. With VR platforms like Oculus Quest 3, students from across the globe can access high-quality simulations without needing expensive lab equipment or materials. This accessibility is critical in providing equitable learning opportunities to students in remote or resource-limited areas [95].

Scalability: Similarly to MOOCs, VR simulations can be scaled up to accommodate many students globally. As Dede (2009) points out, virtual environments can handle vast enrollments without compromising the quality of the learning experience, making it possible to simultaneously provide immersive chemistry education to thousands of students [75].

Cost-Effective Learning: Unlike traditional chemistry education, which often requires expensive materials and lab setups, VR simulations reduce the need for physical resources. VR technology’s affordability and accessibility enable institutions to offer high-quality learning experiences at a fraction of the cost, making education more affordable and sustainable [95].

This review has several limitations that should be noted. First, it is a structured narrative synthesis rather than a comprehensive systematic review or meta-analysis; therefore, publication and selection bias cannot be entirely ruled out. Second, our comparative model relies on secondary sources (empirical studies and developer documentation) and does not include testing with new users, pre- and post-training assessments, or controlled comparisons between platforms. Third, we focused on six widely documented tools, which means that new or institution-specific VR systems, especially those in languages other than English and Russian, may be under-represented. Finally, key practical limitations such as headset cost, maintenance, motion sickness, accessibility for students with disabilities, and teacher training needs are only partially covered in the existing literature.

Future work in this direction should focus on development of standardized evaluation protocols for VR-based chemistry learning, including controlled experimental studies measuring knowledge retention, cognitive load, and spatial reasoning. Another priority is creating scalable curricular frameworks that integrate VR tools with traditional laboratories while supporting accessibility and universal design principles. Research should also explore AI-driven adaptive VR environments, multi-user collaborative simulations, and the integration of VR into metaverse-style educational ecosystems. Finally, economic and logistical analyses are needed to determine the long-term sustainability and cost-effectiveness of VR adoption in diverse institutional contexts.

In summary, current VR simulations for chemistry are constrained by hardware cost and maintenance, incomplete empirical validation, uneven student technological readiness, and substantial teacher training requirements. These limitations reinforce that VR should be integrated thoughtfully into curricula, with attention to equity, support structures, and clear pedagogical goals.

9. Conclusions

Overall, the compared VR simulation platforms show how immersive technologies can greatly enhance chemistry teaching by making abstract molecular and laboratory concepts more visual, interactive, and memorable. At the same time, our analysis indicates that VR should be viewed as a strong supplement, not a substitute, for hands-on laboratory activities and well-planned classroom instruction. Its real impact depends heavily on the pedagogical approach, teacher support, equitable access to equipment, careful management of cognitive load, and safety standards. By creating a comparative model and highlighting both the strengths and weaknesses of current tools, this review aims to guide future research and assist educators in making informed decisions about when and how to incorporate VR into chemistry curricula.

The comparison of the six VR simulations in chemistry education shows that each platform offers unique features and capabilities suited for different user needs and learning environments. The VR Chemistry Lab is a highly accessible, web-based platform that provides a variety of interactive chemical simulations, making it ideal for basic chemistry education. However, it lacks advanced features, which may limit its effectiveness for more complex chemistry topics. Chemistry Lab VR, available on high-end VR hardware like Oculus Rift and HTC Vive, offers high-quality graphics and immersive experiences that are particularly useful for visualizing complex chemical reactions. Despite its strengths, it may not be accessible to all students due to the need for specialized equipment. MIMBUS Chemistry strikes a balance by providing user-friendly experience with customizable experiments suitable for educational settings where ease of use and accessibility are prioritized. Its focus on molecular structures benefits students, though it falls short regarding interactive and realistic lab environments. Nanome, while mainly focused on molecular manipulation and collaboration, offers a unique approach to chemistry education by enabling students to design and explore molecular structures. However, its limitation lies in its lack of comprehensive lab simulations, focusing more on molecular design than complete laboratory experiments. VR Chemistry Lab (Russian) offers a more region-specific solution with Russian language support, expanding its accessibility to Russian-speaking students. Its range of lab exercises makes it a valuable tool, though the language barrier and limited scope may restrict its broader use. Ultimately, VR is not a replacement but a powerful complement to traditional teaching methods. Its successful integration requires curriculum adaptation, teacher training, and accessibility improvements to ensure an engaging, efficient, and inclusive learning environment for students worldwide.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Coatings and Polymeric Materials’ departmental funds 18981.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Coatings and Polymeric Materials of North Dakota State University for providing resources and facilities. This work also used resources from the Center for Computationally Assisted Science and Technology (CCAST) at North Dakota State University, which was made possible in part by the National Science Foundation (NSF) [MRI Award number 2019077]. Supercomputing support provided by the CCAST HPC System at NDSU is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Farsi, G.; Yusof, A.B.M.; Romli, A.; Tawafak, R.M.; Malik, S.I.; Jabbar, J.; Rsuli, M.E.B. A Review of Virtual Reality Applications in an Educational Domain. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 2021, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.; Ng, D.T.K.; Ng, F. Observing Mathematical Properties in the Virtual World: An Exploratory Study of Online Independent Learning of Locus Concepts. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2024, 22, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dinther, R.; de Putter, L.; Pepin, B. Features of Immersive Virtual Reality to Support Meaningful Chemistry Education. J. Chem. Educ. 2023, 100, 1537–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C.S.; Loughran, S.; Kelly, B.; Healy, E.; Lambe, G.; van Rossum, A.; Murphy, B.; Moore, E.; Burke, C.; Morrin, A.; et al. Virtual laboratories complement but should not replace face-to-face classes: Perceptions of life science students at Dundalk Institute of Technology, Ireland. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2025, 49, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Rodriguez, M.C. Student Perspectives on Remote Learning in a Large Organic Chemistry Lecture Course. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, B.; Bayona, S. Virtual Reality in the Learning Process. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2018, 746, 1345–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köroğlu, M. Pioneering virtual assessments: Augmented reality and virtual reality adoption among teachers. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 30, 9901–9948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierdicca, R.; Frontoni, E.; Puggioni, M.P.; Malinverni, E.S.; Paolanti, M. Evaluating Augmented and Virtual Reality in Education Through a User-Centered Comparative Study. In Advances in Computational Intelligence and Robotics; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 229–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirker, J.; Dengel, A.; Holly, M.; Safikhani, S. Virtual Reality in Computer Science Education: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 26th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, Ottawa, OT, Canada, 1–4 November 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, H.; Wahid, S.A.; Ahmad, F.; Ali, N. Game-based learning in metaverse: Virtual chemistry classroom for chemical bonding for remote education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 19595–19619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.; Priya, G.G.L. Conceptual Origins, Technological Advancements, and Impacts of Using Virtual Reality Technology in Education. Webology 2021, 18, 116–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnode, K.; Demchuk, Z.; Johnson, S.; Voronov, A.; Rasulev, B. Computational Protein–Ligand Docking and Experimental Study of Bioplastic Films from Soybean Protein, Zein, and Natural Modifiers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10740–10748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnode, K.; Rasulev, B.; Voronov, A. Synergistic Behavior of Plant Proteins and Biobased Latexes in Bioplastic Food Packaging Materials: Experimental and Machine Learning Study. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2022, 14, 8384–8393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, L.; Rasulev, B.; Turabekova, M.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. Receptor- and ligand-based study of fullerene analogues: Comprehensive computational approach including quantum-chemical, QSAR and molecular docking simulations. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turabekova, M.A.; Rasulev, B.F.; Dzhakhangirov, F.N.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. Aconitum and Delphinium alkaloids of curare-like activity. QSAR analysis and molecular docking of alkaloids into AChBP. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 3885–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, L.; Rasulev, B.; Kar, S.; Krupa, P.; Mozolewska, M.A.; Leszczynski, J. Inhibitors or toxins? Large library target-specific screening of fullerene-based nanoparticles for drug design purpose. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 10263–10276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, G.A.; Lu, C.; Scarabelli, G.; Albanese, S.K.; Houang, E.; Abel, R.; Harder, E.D.; Wang, L. The maximal and current accuracy of rigorous protein-ligand binding free energy calculations. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzyn, T.; Rasulev, B.; Gajewicz, A.; Hu, X.; Dasari, T.P.; Michalkova, A.; Hwang, H.-M.; Toropov, A.; Leszczynska, D.; Leszczynski, J. Using nano-QSAR to predict the cytotoxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Karuth, A.; Pham-The, H.; González-Díaz, H.; Webster, D.C.; Rasulev, B. Machine learning analysis of a large set of homopolymers to predict glass transition temperatures. Commun. Chem. 2024, 7, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmanov, D.; Yusupova, U.; Syrov, V.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Rasulev, B. A Quantitative Structure–Activity Relationship Study of the Anabolic Activity of Ecdysteroids. Computation 2025, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghighi, A.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Iduoku, K.; Kusic, H.; González-Díaz, H.; Rasulev, B. Multi-Endpoint Acute Toxicity Assessment of Organic Compounds Using Large-Scale Machine Learning Modeling. Env. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 10116–10127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuth, A.; Szwiec, S.; Casanola-Martin, G.M.; Khanam, A.; Safaripour, M.; Boucher, D.; Xia, W.; Webster, D.C.; Rasulev, B. Integrated machine learning, computational, and experimental investigation of compatibility in oil-modified silicone elastomer coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 193, 108526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewicz, A.; Schaeublin, N.; Rasulev, B.; Hussain, S.; Leszczynska, D.; Puzyn, T.; Leszczynski, J. Towards understanding mechanisms governing cytotoxicity of metal oxides nanoparticles: Hints from nano-QSAR studies. Nanotoxicology 2014, 9, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvetnic, M.; Juretic Perisic, D.; Kovacic, M.; Ukic, S.; Bolanca, T.; Rasulev, B.; Kusic, H.; Loncaric Bozic, A. Toxicity of aromatic pollutants and photooxidative intermediates in water: A QSAR study. Ecotox Env. Safe 2019, 169, 918–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyrzykowska, E.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Sikorska, C.; Puzyn, T. Development of a novel in silico model of zeta potential for metal oxide nanoparticles: A nano-QSPR approach. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 445702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizochenko, N.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Leszczynski, J.; Puzyn, T. In silico methods for nanotoxicity evaluation: Opportunities and challenges. In Nanotoxicology: Toxicity Evaluation, Risk Assessment and Management; Kumar, V., Dasgupta, N., Ranjan, S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 527–557. [Google Scholar]

- Sizochenko, N.; Mikolajczyk, A.; Syzochenko, M.; Puzyn, T.; Leszczynski, J. Zeta potentials (zeta) of metal oxide nanoparticles: A meta-analysis of experimental data and a predictive neural networks modeling. NanoImpact 2021, 22, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tom, G.; Schmid, S.P.; Baird, S.G.; Cao, Y.; Darvish, K.; Hao, H.; Lo, S.; Pablo-García, S.; Rajaonson, E.M.; Skreta, M.; et al. Self-Driving Laboratories for Chemistry and Materials Science. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 9633–9732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, B.P.; Parlane, F.G.L.; Morrissey, T.D.; Häse, F.; Roch, L.M.; Dettelbach, K.E.; Moreira, R.; Yunker, L.P.E.; Rooney, M.B.; Deeth, J.R.; et al. Self-driving laboratory for accelerated discovery of thin-film materials. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häse, F.; Roch, L.M.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Next-Generation Experimentation with Self-Driving Laboratories. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifrid, M.; Pollice, R.; Aguilar-Granda, A.; Morgan Chan, Z.; Hotta, K.; Ser, C.T.; Vestfrid, J.; Wu, T.C.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. Autonomous Chemical Experiments: Challenges and Perspectives on Establishing a Self-Driving Lab. Acc. Chem. Res. 2022, 55, 2454–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Benito, M.J.; Usmanov, D.; Nishanbaev, S.Z.; Song, X.; Zou, L.; Wu, Y. Quercetin and kaempferol from saffron petals alleviated hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in B16 cells. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 105, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roch, L.M.; Häse, F.; Kreisbeck, C.; Tamayo-Mendoza, T.; Yunker, L.P.E.; Hein, J.E.; Aspuru-Guzik, A. ChemOS: Orchestrating autonomous experimentation. Sci. Robot. 2018, 3, eaat5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usmanov, D.; Azamatov, A.; Baykuziyev, T.; Yusupova, U.; Rasulev, B. Chemical constituents, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of iridoids preparation from Phlomoides labiose bunge. Nat. Prod. Res. 2022, 37, 1709–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvish, K.; Skreta, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yoshikawa, N.; Som, S.; Bogdanovic, M.; Cao, Y.; Hao, H.; Xu, H.; Aspuru-Guzik, A.; et al. ORGANA: A robotic assistant for automated chemistry experimentation and characterization. Matter 2025, 8, 101897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, M.; Thompson, E.M. The Role of Virtual Reality in Built Environment Education. J. Educ. Built Environ. 2008, 3, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, J.B.; Campbell, J.P.; McCarthy, D.R.; McKay, K.T.; Hensinger, M.; Srinivasan, R.; Zhao, X.; Wurthmann, A.; Li, J.; Schneebeli, S.T. Chemical Exploration with Virtual Reality in Organic Teaching Laboratories. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 1961–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojsoska, B.; Pande, P.; Moeller, M.E.; Ramasamy, P.; Jepsen, P.M. Virtual Reality in an Eco-Niche Undergraduate Organic Chemistry Laboratory Course: New Practice in Chemistry Lab Teaching. J. Chem. Educ. 2024, 101, 4686–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standen, P.J.; Brown, D.J. Virtual reality and its role in removing the barriers that turn cognitive impairments into intellectual disability. Virtual Real. 2006, 10, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.J.; Greenwood-Ericksen, A.; Cannon-Bowers, J.; Bowers, C.A. Using Virtual Reality with and without Gaming Attributes for Academic Achievement. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2006, 39, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatli, Z.; Ayas, A. Virtual laboratory applications in chemistry education. Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 9, 938–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Chu, Q.; Chen, D. Exploring Chemical Reactions in Virtual Reality. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 1635–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabr, M.A.M.; Sleem, W.F.; El-wkeel, N.S. Effect of virtual reality educational program on critical thinking disposition among nursing students in Egypt: A quasi-experimental pretest–posttest design. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, D.T.K. What is the metaverse? Definitions, technologies and the community of inquiry. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 38, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnagan, C.L.; Dannenberg, D.A.; Cuales, M.P.; Earnest, A.D.; Gurnsey, R.M.; Gallardo-Williams, M.T. Production and Evaluation of a Realistic Immersive Virtual Reality Organic Chemistry Laboratory Experience: Infrared Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 97, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-H.; Cheng, T.-W. A Sustainability Innovation Experiential Learning Model for Virtual Reality Chemistry Laboratory: An Empirical Study with PLS-SEM and IPMA. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhaychuk, D.V.; Zentsova, О.S.; Shevchuk, A.S. The new platforms of digital educational content: Practice and experience of higher education. Вестник Алтайскoй Академии Экoнoмики Права 2024, 3, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, M.; Salvadori, A.; Lazzari, F.; Paoloni, L.; Nandi, S.; Mancini, G.; Barone, V.; Rampino, S. Chemical promenades: Exploring potential-energy surfaces with immersive virtual reality. J. Comput. Chem. 2020, 41, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.I.; Bielawski, K.S.; Prada, R.; Cheok, A.D. Haptic virtual reality and immersive learning for enhanced organic chemistry instruction. Virtual Real. 2018, 23, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrby, M.; Grebner, C.; Eriksson, J.; Boström, J. Molecular Rift: Virtual Reality for Drug Designers. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2475–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnagan, C.L.; Gallardo-Williams, M.T. Overcoming Physical Separation During COVID-19 Using Virtual Reality in Organic Chemistry Laboratories. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 97, 3060–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounlaxay, K.; Yao, D.; Woo Ha, M.; Kyun Kim, S. Design of Virtual Reality System for Organic Chemistry. Intell. Autom. Soft Comput. 2022, 31, 1119–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Williams, M.T.; Dunnagan, C.L. Designing Diverse Virtual Reality Laboratories as a Vehicle for Inclusion of Underrepresented Minorities in Organic Chemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 99, 500–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Cook, M.; Courtney, M. Exploring Chemistry with Wireless, PC-Less Portable Virtual Reality Laboratories. J. Chem. Educ. 2020, 98, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzis, F.; Visconti, A.; Restivo, S.; Mazzini, F.; Esposito, S.; Garofalo, S.F.; Marmo, L.; Fino, D.; Lamberti, F. Combining virtual reality with asymmetric collaborative learning: A case study in chemistry education. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia Fracaro, S.; Chan, P.; Gallagher, T.; Tehreem, Y.; Toyoda, R.; Bernaerts, K.; Glassey, J.; Pfeiffer, T.; Slof, B.; Wachsmuth, S.; et al. Towards design guidelines for virtual reality training for the chemical industry. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 36, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumbri, K.; Ishak, M.A.I. Can Virtual Reality Increases Students Interest in Computational Chemistry Course? A Review. J. Penelit. Dan. Pengkaj. Ilmu Pendidik. E-Saintika 2022, 6, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimenko, N.; Okolzina, A.; Vlasova, A.; Tracey, C.; Kurushkin, M. Introducing Atomic Structure to First-Year Undergraduate Chemistry Students with an Immersive Virtual Reality Experience. J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 2104–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, A.; Avraamidou, L.; Kool, D.; Lee, M.; Eisink, N.; Albada, B.; van der Kolk, K.; Tromp, M.; Bitter, J.H. The Use of Virtual Reality in A Chemistry Lab and Its Impact on Students’ Self-Efficacy, Interest, Self-Concept and Laboratory Anxiety. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2022, 18, em2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limniou, M.; Roberts, D.; Papadopoulos, N. Full immersive virtual environment CAVETM in chemistry education. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Zhang, G.-H.; Xiang, Y.-Q.; Yuan, W.-L.; Fu, J.; Wang, S.-L.; Xiong, Z.-X.; Zhang, M.-D.; He, L.; Tao, G.-H. Virtual Reality Assisted General Education of Nuclear Chemistry and Radiochemistry. J. Chem. Educ. 2022, 99, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbonifo, O.C.; Sarumi, O.A.; Akinola, Y.M. A chemistry laboratory platform enhanced with virtual reality for students’ adaptive learning. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, N.S.; Varghese, N.; Babu, N.S.C. Virtual Chemistry Lab to Virtual Reality Chemistry Lab. Resonance 2022, 27, 1371–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Iqbal, M.U.; Shahab, M.A.; Srinivasan, R. Review of Virtual Reality (VR) Applications to Enhance Chemical Safety: From Students to Plant Operators. ACS Chem. Health Saf. 2022, 29, 246–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, G.; Elban, M.; Yildirim, S. Analysis of Use of Virtual Reality Technologies in History Education: A Case Study. Asian J. Educ. Train. 2018, 4, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu-Au, E. Learning Abstract Chemistry Concepts with Virtual Reality: An Experimental Study Using a VR Chemistry Lab and Molecule Simulation. Electronics 2024, 13, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu-Au, E.; Okita, S. Exploring Differences in Student Learning and Behavior Between Real-life and Virtual Reality Chemistry Laboratories. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2021, 30, 862–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkmen, M.; Balla, M.; Cavanaugh, M.; Smith, I.; Flores-Artica, M.; Thornhill, A.; Lockart, J.; Johnson, W.; Peterson, C. Abstract 1484 Use of the Virtual Reality App Nanome for Teaching Three-Dimensional Biomolecular Structures. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkmen, M.B.; Balla, M.; Cavanaugh, M.T.; Smith, I.N.; Flores-Artica, M.E.; Thornhill, A.M.; Lockart, J.C.; Peterson, C.N. An idea to explore: Use of the virtual reality app Nanome for teaching three-dimensional biomolecular structures. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2025, 53, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.; Kamel, S.; Assem, A. Extended reality for enhancing spatial ability in architecture design education. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.A.; Burte, H.; Renshaw, K.T. Connecting spatial thinking to STEM learning through visualizations. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 2, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-K.; Lee, S.W.-Y.; Chang, H.-Y.; Liang, J.-C. Current status, opportunities and challenges of augmented reality in education. Comput. Educ. 2013, 62, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador, C.; Liu, F.W.; Johnson-Glenberg, M.C.; LiKamWa, R. Work-in-Progress—Titration Experiment: Virtual Reality Chemistry Lab with Haptic Burette. In Proceedings of the 2020 6th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN), San Luis Obispo, CA, USA, 21–25 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dede, C. Immersive Interfaces for Engagement and Learning. Science 2009, 323, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez, J.A.; Bueno, A.M.V. Learning organic chemistry with virtual reality. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Engineering Veracruz (ICEV), Boca del Río, Mexico, 26–29 October 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lorusso, M.; Rossini, M.; Carulli, M.; Bordegoni, M.; Colombo, G. A Virtual Reality Application for 3D Sketching in Conceptual Design. Comput.-Aided Des. Appl. 2021, 19, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihlenfeldt, W.D. Virtual Reality in Chemistry. J. Mol. Model. 1997, 3, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duca, A.; Constantinescu, G.-G.; Iftene, A. Future Education: Experimenting with Chemical Reactions in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications (INISTA), Craiova, Romania, 4–6 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, B.C.; Hurst, W.; Barrow, J.; Long, J.; Shearer, G.C.; Hodges, J.K.; Lawler, O.; Patel, R.; Schiavone, T.; Masterson, T.D. Efficacy and Engagement with an Immersive Virtual Learning Experience of the Citric Acid Cycle. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2025, 53, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, D.; Hamam, A.; Scott, C.; Karaman, B.; Toker, O.; Pena, L. Towards a New Chemistry Learning Platform with Virtual Reality and Haptics. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2021, 12785, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, Z.; Goetz, E.T.; Keeney-Kennicutt, W.; Cifuentes, L.; Kwok, O.; Davis, T.J. Exploring 3-D virtual reality technology for spatial ability and chemistry achievement. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2013, 29, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, Z.A. Teaching and Learning Chemistry via Augmented and Immersive Virtual Reality. ACS Symp. Ser. 2019, 1318, 31–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.V.; Carberry, D.; Beenfeldt, C.; Andersson, M.P.; Mansouri, S.S.; Gallucci, F. Virtual reality in chemical and biochemical engineering education and training. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 36, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saritas, M.T. Chemistry teacher candidates acceptance and opinions about virtual reality technology for molecular geometry. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 10, 2745–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, M.; Mocerino, M.; Tang, K.-S.; Treagust, D.F.; Tasker, R. Interactive Immersive Virtual Reality to Enhance Students’ Visualisation of Complex Molecules. In Research and Practice in Chemistry Education; Schultz, M., Schmid, S., Lawrie, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.T.; Fogler, H.C. The Application of Virtual Reality to (Chemical Engineering) Education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–31 March 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, M.J.; Mantell, C.; Caro, I.; de Ory, I.; Sánchez, J.; Portela, J.R. Creation of Immersive Resources Based on Virtual Reality for Dissemination and Teaching in Chemical Engineering. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, O.N. Virtual Reality: A Tool for Improving the Teaching and Learning of Technology Education. In Virtual Reality and Its Application in Education; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viitaharju, P.; Nieminen, M.; Linnera, J.; Yliniemi, K.; Karttunen, A.J. Student experiences from virtual reality-based chemistry laboratory exercises. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 44, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Garduño, H.A.; Esparza Martínez, M.I.; Portuguez Castro, M. Impact of Virtual Reality on Student Motivation in a High School Science Course. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udeozor, C.; Toyoda, R.; Russo Abegão, F.; Glassey, J. Perceptions of the use of virtual reality games for chemical engineering education and professional training. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2021, 6, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liagkou, V.; Salmas, D.; Stylios, C. Realizing Virtual Reality Learning Environment for Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2019, 79, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, A. The virtual chemistry lab for reactions at surfaces: Is it possible? Will it be useful? Surf. Sci. 2002, 500, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, B.; Thomas, J. Adoption of virtual reality technology in higher education: An evaluation of five teaching semesters in a purpose-designed laboratory. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 27, 1287–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).