Abstract

Efficient water management is increasingly critical in vineyard operations, particularly in the context of climate change and the rising demand for sustainable agricultural practices. Regulated deficit irrigation has emerged as a promising technique that allows significant water savings while sustaining or improving the quality of grapes. However, its effective implementation requires timely and precise information on vine water status and environmental conditions (pluviometry, humidity, radiation, etc.). This study presents the methodology of a decision-support tool that tested the application of several artificial intelligence regression models. Among the algorithms evaluated, an Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) regression model showed the best performance and was adopted as the core predictive engine of the ViñAI tool to optimize deficit irrigation in vineyards. Based on the developed methodology, the ViñAI tool integrates open-access environmental data such as weather forecasts and satellite-based estimates of evapotranspiration. Furthermore, ViñAI is designed with the potential to integrate sensor-based field data. Overall, the results demonstrate that ViñAI offers a scalable, data-driven approach to support climate-smart irrigation decisions in vineyards, particularly in sensor-sparse or resource-limited contexts, and provides a robust basis for further multi-season and multi-region validation.

1. Introduction

According to the World Atlas of Desertification of the UN, recent evidence underscores the accelerating scale of land-system degradation and its systemic risks. In Europe, inappropriate land and water resources management is linked to approximately 970 million tons of annual soil loss, contributing to an estimated 24 billion tons lost globally each year. Compounding pressures from water scarcity heighten these risks: by 2025, about 1.8 billion people are projected to live under absolute water scarcity, and aquifer depletion already affects more than half of the world’s population [1].

Wine production is a globally distributed sector with significant economic, cultural, and environmental importance. According to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV), global wine production reached approximately 237 million hectoliters in 2023 [2]. Within this global context, Spain occupies a leading position as one of the world’s largest wine producers and exporters. Official data from the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food indicate that Spain maintains the largest vineyard area in the European Union and consistently ranks as the third-largest wine producer, following Italy and France [3].

In viticulture, irrigation management remains one of the most critical yet least-optimized aspects of production, particularly under the increasing pressure of water scarcity and climate variability. Many growers still rely on traditional or empirical irrigation schedules, often based on experience, visual assessment of vine condition, or fixed calendar intervals, rather than on quantitative data or real-time monitoring. This conventional approach does not account for the complex interactions between soil moisture dynamics, plant physiological status, and local climatic conditions, leading either to over-irrigation or excessive water stress, both of which can negatively impact grape yield and quality. Despite the availability of sensors and remote sensing technologies, most existing systems are fragmented and lack the capacity to integrate and analyze large, heterogeneous data streams in real time.

This not only enhances the economic viability of precision irrigation but also aligns with broader goals of energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI), open data, and smart infrastructure represents a transformative opportunity for vineyard management in a changing climate.

As a result, decision-making remains largely manual and reactive. The problem, therefore, lies in the absence of intelligent, data-driven tools capable of synthesizing environmental, agronomic, and physiological information to optimize deficit irrigation strategies dynamically and efficiently in vineyards.

Water availability is a critical factor influencing grapevine physiology, composition, and, ultimately, wine quality [4,5]. In recent years, climate change—marked by more frequent droughts and increasingly complex rainfall patterns—has driven the adoption of precision irrigation practices in vineyards [6]. These practices have become essential for sustainable wine production. Among them, deficit irrigation stands out as one of the most promising approaches. Regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) involves applying water at less than 100% of crop water requirements during specific growth stages and periods.

Water use efficiency (WUE) is a key indicator for evaluating the effectiveness of deficit irrigation in vineyards [7]. When properly managed, deficit irrigation often increases WUE because vines allocate resources more efficiently, favoring fruit development over excessive vegetative growth. This approach has shown promise in improving grape quality traits—such as phenolic content and flavor concentration—while conserving water resources [8]. However, its effectiveness depends heavily on accurate, timely information about vine water status and environmental conditions. AI has become increasingly relevant in agricultural water management, offering methods to capture the complexity of interactions between climate, soil, and management practices.

In viticulture, AI-based approaches have been successfully integrated into decision-support systems for regulated deficit irrigation, showing that machine learning can support irrigation scheduling and improve grapevine performance. These advances highlight the potential of AI-driven decision tools to complement traditional agronomic knowledge and provide scalable solutions for precision irrigation.

One of the main challenges in developing an AI-based deficit irrigation tool lies in integrating heterogeneous data sources with varying spatial and temporal resolutions. While open environmental data provide broad coverage, they often lack the precision that in-field sensors can offer.

In Mediterranean vineyards, where water is a limited resource and climate variability is high, irrigation management requires strategies that balance production goals with long-term sustainability. Research on water and vegetation management in Mediterranean vineyards has emphasized the critical role of deficit irrigation in achieving both quality and efficiency objectives [9]. In addition, the ViñAI framework incorporates short-term weather forecasts and dynamic evapotranspiration signals to adjust irrigation recommendations during extreme climatic events such as heatwaves or abrupt drought intensification, enabling proactive rather than reactive deficit irrigation management.

Cost Determinants and Optimization Potential Through AI

The national reference framework provided in the REDES TECO Viña report, published by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Spain [10], identifies the following components as the main cost determinants in vineyard production:

- Energy and irrigation costs.

These are among the most influential factors in total production costs, especially in irrigated systems where water pumping and pressurization significantly affect profitability. Studies on regulated deficit irrigation (RDI) demonstrate that applying controlled water stress can reduce irrigation water use by 20–40% and energy consumption by 25–35%, with direct cost savings of approximately EUR 500–1200 per hectare per year [11,12,13,14].

- 2.

- Fertilization and phytosanitary treatment costs (particularly fungicides).

Input-related costs, including fertilizers and pesticides, represent another major share of vineyard expenditure. Artificial intelligence (AI) and multi-source monitoring enable site-specific fertigation and predictive pest control, which can reduce fertilizer and pesticide use by 15–25% while maintaining vine health and yield.

- 3.

- Labor costs, both hired and family.

Although less directly influenced by irrigation decisions, precision agriculture technologies and AI-based irrigation scheduling systems can reduce manual monitoring requirements, lowering labor needs for field inspection and irrigation control (Bellvert et al., 2020; MAPA, 2024) [10,14].

- 4.

- Opportunity costs related to land and capital.

Efficient irrigation and input management enhance long-term profitability by increasing water productivity and yield quality. This leads to improved net margins of 15–25%, as reported in both the academic literature and national benchmarking analyses such as the REDES TECO Viña Report (MAPA, 2024) [10], based on the agri benchmark TIPI-CAL methodology.

The integration of AI and multi-source data (soil moisture sensors, remote sensing, and meteorological forecasting) directly influences these cost determinants by optimizing irrigation scheduling and input allocation.

Intelligent precision deficit irrigation systems, when combined with real-time data analytics, enable reductions in both irrigation frequency and duration without compromising yield or grape quality [15].

Although AI-enhanced irrigation systems have shown substantial potential for optimizing water use and supporting regulated deficit irrigation strategies, several critical limitations remain. Oğuztürk 2025 provides meta-analytical evidence that AI-driven irrigation can achieve 30 to 50 percent water savings and 20 to 30 percent yield gains, yet also emphasizes persistent constraints related to sensor calibration drift, data sparsity, and limited validation across diverse crops and production contexts [16]. In parallel, Gaitan et al. 2025 demonstrate that integrating OpenAI models with IoT-based monitoring can generate contextual irrigation recommendations at farm and national scales, but their architecture operates mainly on environmental and management variables and does not explicitly couple irrigation decisions to cultivar-specific physiological or biochemical responses [17]. Focusing specifically on viticulture, Kang et al. 2023 developed an artificial neural network-based decision-support system that predicts weekly soil moisture and computes irrigation amounts to maintain predefined soil moisture targets linked to desired levels of vine water stress under regulated deficit irrigation [9]. While this system represents an important step toward precision RDI in wine grapes, its optimization remains largely framed in terms of soil water balance, evapotranspiration, and aggregate yield quality tradeoffs, without integrating mechanistic information on berry metabolism, phenolic composition, or drought-responsive gene expression. Taken together, these studies indicate that current AI-based irrigation frameworks for grapevines are predominantly data-driven and hydrologically oriented and only indirectly address the physiological pathways that determine berry composition. The work proposed in this study is designed to bridge this gap by embedding cultivar-specific physiological and compositional criteria into AI-mediated irrigation scheduling, thereby aligning regulated deficit irrigation not only with predicted soil moisture and climatic variability but also with the biochemical processes that underpin grape and wine quality.

As demonstrated by Alatzas et al. (2021), a water deficit can positively influence grape berry development by stimulating the accumulation of phenolics, anthocyanins, and other quality-enhancing metabolites, underscoring the agronomic value of controlled deficit irrigation [18]. Similarly, Tan et al. (2025) demonstrated that RDI applied at key developmental stages significantly boosts flavonoids, tannins, anthocyanins, and antioxidant capacity while conserving water [19].

Consequently, vineyards employing AI-assisted RDI achieve 30% lower water and energy consumption, 20% lower input costs, and 15–25% higher net profitability, highlighting the strong potential of digital technologies for sustainable cost optimization in Mediterranean viticulture [9,10,11,14].

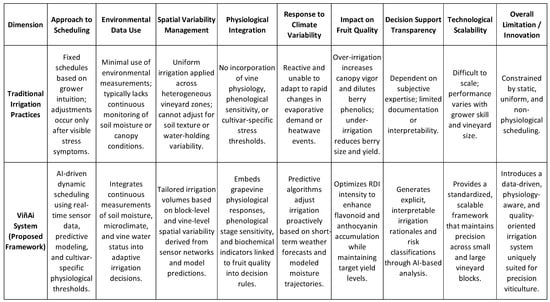

Traditional irrigation practices in viticulture rely heavily on fixed schedules, visual assessment of canopy symptoms, and grower intuition, often without integrating real-time measurements of soil moisture or plant water status. Such approaches are inherently reactive and can neither account for spatial variability in soil properties nor capture rapid changes in evaporative demand, leading to frequent over- or under-irrigation. Over-irrigation promotes excessive vegetative growth, increases canopy shading, and dilutes berry phenolics, whereas insufficient irrigation during sensitive phenological stages reduces berry size and yield and may impair key physiological processes. Furthermore, conventional irrigation systems are unable to synchronize water application with cultivar-specific thresholds of vine water stress, which are essential for optimizing regulated deficit irrigation outcomes in premium wine grape production. These limitations underscore the need for adaptive, data-driven systems that incorporate environmental dynamics and plant physiological responses rather than relying on static estimations or uniform irrigation scheduling across heterogeneous vineyard blocks. In this context, ViñAi introduces a novel advancement by integrating real-time environmental monitoring with cultivar-specific physiological information and data-driven modulation of deficit irrigation intensity. Unlike traditional systems or prior AI-based frameworks, ViñAi links irrigation decisions directly to grapevine biochemical and metabolic indicators associated with phenolic accumulation, berry development, and drought-responsive pathways, enabling irrigation recommendations that are both dynamic and quality-oriented. By unifying predictive analytics with cultivar-level physiological thresholds, ViñAi provides a more precise, responsive, and quality-centric irrigation strategy that addresses the central limitations of existing practices as it is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Traditional irrigation and ViñAI comparative.

Recent work on weather and environmental information systems also highlights broader technological limitations that affect real-time decision-making in agriculture. Studies on improved weather retrieval platforms show that systems dependent on repeated external API calls suffer from latency, high server load, and inconsistent performance under low bandwidth conditions, reducing their reliability in rural or resource-constrained environments [20]. These analyses also demonstrate that the absence of local caching, multilingual support, and adaptive interfaces can limit accessibility and prevent efficient user interaction, especially when rapid updates are required for operational decisions. Although these applications are not designed for irrigation control, the system-level constraints they reveal are directly relevant to precision agriculture, where the timeliness, stability, and contextualization of environmental data are essential. These findings reinforce the need for irrigation decision-support tools that incorporate efficient data retrieval pathways, resilient architectures, and user-centered design to ensure robustness under real field conditions.

Recent studies in climate modeling provide further evidence of the structural limitations that affect many current AI-based environmental and agricultural decision systems. As demonstrated by Khadar Maideen et al. 2024, traditional deterministic models are unable to respond effectively to dynamic environmental variability, whereas AI-driven approaches offer faster processing and higher predictive accuracy but still face key constraints related to data quality, computational load, and risks of overfitting [21]. These challenges parallel those observed in agricultural prediction systems, where complex nonlinear relationships and fragmented datasets hinder operational deployment. Complementary research on agricultural forecasting reinforces this perspective. Renju and Brunda 2024 show that ensemble stacking models combining decision trees, linear regression, and boosting algorithms can achieve exceptional predictive accuracy for crop yield estimation. While such multi-model learning frameworks successfully capture broad statistical relationships among agricultural variables, they remain primarily oriented toward predicting production outcomes and do not incorporate the physiological, phenological, or biochemical pathways that regulate real-time crop water use or stress responses [22]. Together, these findings reveal a persistent gap in existing AI-based systems: they model environmental or agronomic patterns at a large scale, yet they rarely translate this information into actionable, physiology-aware irrigation decisions. This gap underscores the novelty of ViñAI, which aligns machine learning predictions with cultivar-specific physiological thresholds and biochemical markers relevant to grape quality, thereby providing a dynamic, evidence-based deficit irrigation strategy that bridges environmental analytics with vine-level functional responses.

This work addresses a clear methodological gap in precision irrigation for vineyards. Despite increasing climatic variability, most irrigation decisions still rely on empirical scheduling and do not exploit AI-driven integration of environmental and agronomic data. Existing AI-based systems remain largely hydrological, offer limited support for regulated deficit irrigation, and often require dense sensor networks that restrict their applicability in resource-constrained contexts. In response, this study develops the ViñAI methodology, which applies artificial intelligence specifically to regulated deficit irrigation, integrates multi-source open environmental data with vineyard-level variables, and provides a transferable, data-driven framework capable of supporting quality-oriented and climate-adaptive irrigation decisions.

2. Materials and Methods

To develop a precision irrigation tool tailored for vineyard management, a hybrid system integrating AI models with multi-source environmental data was designed. The system leverages both openly available meteorological and remote sensing datasets (SIAR [23] and AEMET [24]) and high-resolution in-field sensor readings to estimate vine water status and recommend irrigation strategies under deficit conditions. This approach aims to support site-specific water applications that maximize water use efficiency while preserving or enhancing grape quality.

The selection of predictors prioritized variables that are openly available (ET0, temperature, humidity, wind speed, solar radiation, Kc, phenological stage, and soil water limits such as field capacity and PWP), as these can be sourced from national meteorological networks and remote sensing products and subsequently transferred to new vineyards without additional hardware requirements. This design contrasts with tools that depend primarily on in-field sensors: while sensors can improve local precision, they add cost, maintenance, and deployment barriers, whereas our open-data inputs support scalable, sensor-sparse deployment and still capture the key drivers that bound atmospheric demand and available water.

The methodological framework comprises six core components: vineyard characterization, data acquisition from both open and local sources, data preprocessing and integration, AI model development and validation, an irrigation decision-making module, and a performance evaluation protocol. Together, these elements support a scalable, data-driven solution for sustainable irrigation management in vineyards, responding dynamically to both climatic variability and local vine needs.

2.1. Study Area and Vineyard Description in ViñAI Case

The study was conducted in three vineyard fields located in the Borja region, northeastern Spain, a well-known viticultural area within the Campo de Borja. The vineyards were monitored over a one-year period (2024), covering a range of seasonal and interannual climatic variability.

Borja area experiences a Mediterranean–continental type of climate, marked by warm, dry summers and relatively cool winters with higher rainfall. Average annual rainfall ranges between approximately 350 and 450 mm, with most precipitation occurring during spring and autumn. Summers are typically arid and often experience prolonged heat spells, with daytime temperatures surpassing 30 °C. The region is also influenced by the Cierzo, a prevailing northwesterly wind that is both strong and persistent, enhancing evapotranspiration rates and influencing the water balance of the vineyards.

The three vineyard fields included in this study represent typical local viticultural conditions, with vines predominantly planted on gentle slopes (2–7%) and at elevations ranging between 400 and 500 m above sea level. The soils are generally calcareous and loamy, with moderate water-holding capacity, and are managed under rainfed or deficit irrigation practices, reflecting common regional water constraints.

The vineyards are primarily cultivated with Garnacha (Grenache), the main red variety in the region. The vines are managed using a vertical shoot-positioned (VSP) trellis system, with row spacing of approximately 2.5 m and vine spacing of 1–1.2 m. These vineyard plots offer a representative setting for testing the capabilities of the ViñAI tool, as they enable the combined use of satellite-derived environmental information and ground-based sensor measurements to advance practices in precision viticulture.

2.2. AI Model Development

2.2.1. Variables and Data Sources

The predictive model was trained using data collected from three vineyard plots over the period of 2018–2024. Input variables were categorized according to their source:

- -

- Weather station variables (local meteorological records):

- Average Temperature (°C): daily mean air temperature, influencing vine growth, evapotranspiration, and berry ripening.

- Average Humidity (%): atmospheric moisture conditions, affecting evapotranspiration and vine water stress.

- Wind Speed (m/s): a driver of evapotranspiration and canopy microclimate regulation.

- Solar Radiation (MJ/m2): energy input determining photosynthesis and evapotranspiration.

- Reference Evapotranspiration, ET0 (mm): calculated indicator of atmospheric water demand, essential for irrigation scheduling.

- -

- Soil and field measurements:

- Field Capacity, FC (mm): the maximum amount of soil water available after drainage, defining soil water availability.

- Permanent Wilting Point, PWP: threshold below which vines cannot extract water, critical for defining usable soil moisture.

- Root depth (m): effective root depth.

- Salinity (mS/cm): soil electrical conductivity, reflecting salt accumulation that can affect water uptake and vine physiology.

- Ks: reduction factor accounting for soil water stress effects on crop evapotranspiration.

- -

- Irrigation system and management plan:

- Irrigation Volume (mm): applied water depth, representing management decisions in deficit irrigation.

- Efficiency: irrigation system performance, reflecting water distribution and losses in the field.

To contextualize the predictive modeling framework, we considered physiological principles derived from water balance approaches validated in Mediterranean vineyards. Gaudin et al. (2017) demonstrated that under prolonged dry conditions (rainfall, soil evaporation, and capillary rise are negligible), vine water loss is dominated by transpiration, allowing simplification of the vineyard water balance [25].

In this framework, the objective parameter to be predicted by the AI model is the irrigation volume. By estimating the required irrigation depth based on weather, soil, and management variables, the model provides a data-driven decision-support tool to optimize deficit irrigation scheduling.

2.2.2. Model Architecture and Selection

To identify the most effective predictive algorithm, the PyCaret library was employed [26]. PyCaret allows for the automated comparison of a wide range of supervised learning algorithms under standardized workflows. The dataset was split across vineyard plots and years to ensure robustness and generalizability.

In this study, the target variable was the irrigation volume (mm), while the remaining climatic, soil, and management variables served as predictors. Through PyCaret’s benchmarking process, models were ranked based on predictive performance metrics. The analysis also provided insights into variable importance, highlighting which climatic, soil, and management factors contributed most strongly to irrigation optimization.

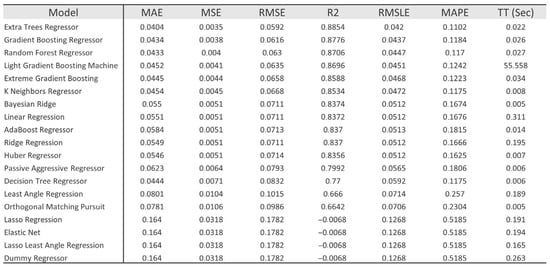

Figure 2 summarizes the benchmarking results across the supervised algorithms considered, reported with standard regression metrics (MAE, MSE, RMSE, R2, and MAPE) [27] produced through PyCaret’s comparison workflow. In addition to ranking models by predictive accuracy, the workflow surfaces variable-importance patterns that help relate performance to agronomic drivers for irrigation.

Figure 2.

Algorithm evaluated metrics.

Based on this benchmark and our deployment constraints, we selected Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [28] as the final estimator for ViñAI, balancing low error with efficiency and robustness across plots and years. XGBoost also supports variable selection via feature importance: the leading contributors were ET0 (mm) 0.54, phenological stage 0.19, Kc 0.10, average humidity (%) 0.06, wind speed (m/s) 0.05, solar radiation (MJ/m2) 0.03, and average temperature (°C) 0.03, while root depth (m) 0.00, FC (mm) 0.00, and permanent wilting point, PWP (mm) 0.00 were negligible in our training runs.

2.2.3. Training and Validation

The dataset used for model training comprised observations collected from three vineyard fields located in the Borja region (Spain) between 2018 and 2024. These data included climatic, soil, and irrigation management variables, which were preprocessed and used to train multiple machine learning algorithms within the PyCaret environment.

The model included 11 numeric predictors after preprocessing. Standard cleaning procedures were applied, including mean imputation for missing numerical values (8.4% of rows affected). Model evaluation was performed using PyCaret’s 10-fold K-Fold cross-validation scheme, in which each fold used approximately 70% of the samples for training and 30% for validation. This structure avoids data leakage and yields a reliable estimate of out-of-sample performance. All preprocessing steps (imputation, scaling, and feature transformation) were fitted exclusively on the training subset within each fold to ensure methodological rigor. The final estimator (XGBoost) was selected based on the averaged cross-validated metrics across folds and was subsequently validated under practical conditions during the 2025 growing season. A vineyard technician was asked to provide their intended irrigation decisions for specific weeks, which were then compared against the algorithm’s predicted irrigation volumes. This comparison allows us to assess the alignment between expert-driven irrigation scheduling and AI-based recommendations, thereby validating the model’s capacity to reproduce real-world decision-making.

2.3. Irrigation Decision-Making Framework

Once the predictive model and the deficit irrigation tool were developed, a key step was to bring the technology closer to end users by making it accessible and easy to interact with for farmers. To achieve this, a set of intelligent agents was designed to serve as the interface between the ViñAI system and the user, ensuring that relevant information is delivered in a practical and intuitive way.

Given that mobile phones are the most widespread and familiar digital tools among farmers, they were chosen as the main access point to the system. Through common interaction channels such as email notifications and instant messaging services, users can receive irrigation recommendations and interact directly with the AI agents. These chat interfaces go beyond providing irrigation advice: they also offer contextual information about vineyard management, including vine health indicators, potential diseases, and corrective treatment suggestions.

2.3.1. Periodic Email with Weekly Information

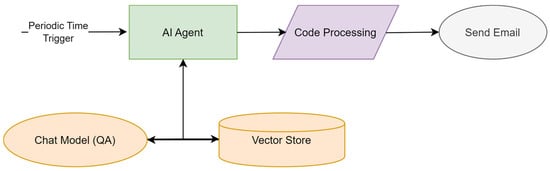

This diagram illustrates the workflow for automatically sending weekly emails powered by the ViñAI application. The process begins with a Periodic Time Trigger, which activates the AI agent at scheduled intervals. The AI agent interacts with both a Chat Model (QA) for question-answering capabilities and a vector store to retrieve relevant stored information. Once the required content is gathered, it is passed through a code-processing component that prepares and structures the email. Finally, the system executes the Send Email step, delivering the weekly update to users.

In essence, the setup combines automation, AI-driven information retrieval and code execution to ensure that users receive timely and relevant emails without manual intervention. It enables a streamlined flow from data retrieval to final communication, making the system efficient and scalable as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the periodic email AI agent workflow. A Periodic Time Trigger activates the AI agent, which processes code and sends results via email. The agent interacts with a Chat Model (QA) and a vector store to retrieve and manage contextual information.

2.3.2. Feedback Agent

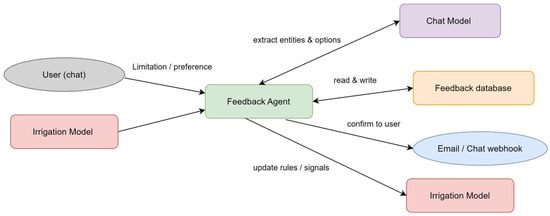

The Feedback Agent is the orchestrator of user feedback across the irrigation decision system. It ingests two primary inputs: (1) user limitations or preferences coming from user, and (2) signals from the Irrigation Model whenever a recommendation is not applicable in the field. From there, it launches a structured workflow that turns raw comments and exceptions into actionable improvements.

First, as shown in Figure 4, the agent passes messages to a language model to extract entities and options (e.g., scheduling constraints, thresholds, etc.). This step converts free text into structured data. Next, it reads from and writes to the feedback database, maintaining an auditable history of cases, rationales, and outcomes. With those records in place, the agent confirms back to the user—via email or chat webhook—what was captured and how it will influence future recommendations. Finally, it updates rules and signals consumed by the Irrigation Model, closing the learning loop: the next time the system evaluates a recommendation, it already incorporates the user’s constraints and the observed non-applicability patterns. The result is more relevant guidance, less operational friction, and a system that continually improves with every interaction.

Figure 4.

Feedback Agent workflow which collects user preferences and “not applicable” events, extracts entities via NLP, receives feedback, confirms to the user, and updates rules that feed the Irrigation Agent.

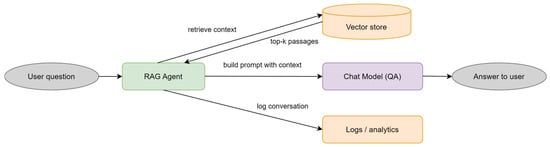

2.3.3. RAG Agent

The RAG Agent turns a user’s question into a grounded answer by acting as a coordinator. First, as shown in Figure 5, it queries a vector store to semantically retrieve the top-k passages most relevant to the request. This goes beyond matching keywords to match meaning. Those snippets become structured context that the agent uses to assemble a concise, source-aware prompt.

Figure 5.

RAG Agent workflow, where a user’s question triggers retrieval of top-k passages from a vector store; the agent builds a context-aware prompt for the QA Chat Model, returns the answer to the user, and (optionally) logs the interaction for analytics.

That prompt is sent to the Chat Model (QA), which generates the answer to the user based on the retrieved evidence. Optionally, the agent logs the conversation for analytics—capturing what was retrieved, how the prompt was built, and the model’s output—so teams can monitor quality and tune retrieval or prompts over time.

3. Results and Discussion

Figure 6 shows an example screenshot of obtained results from the ViñAI application. The interface is structured for intuitive navigation and critical data visualization, focusing on real-time needs and future planning.

Figure 6.

Example screenshot of obtained results from the ViñAI application.

- I.

- Header and Primary Navigation

The upper-left corner of the dashboard houses the primary identification element, consisting of the Web Page Title and the Tool/Application Name. This is crucial for establishing context and branding.

Positioned on the upper right are the Main Navigation Buttons, offering seamless transition between core system functionalities:

Home: Provides immediate access to the primary dashboard overview.

Map: Initiates the Full-Screen Map View, essential for comprehensive spatial analysis.

Reports: Directs the user to the Historical Reports Log, enabling the review of past operational data.

Settings: Accesses the system Configuration and Adjustment panel.

- II.

- Real-Time Data and Assistance

Located slightly below the header on the left is the Assistance Button. This control is specifically designed to facilitate immediate user support by launching the integrated WhatsApp Chatbot, streamlining communication and troubleshooting.

Adjacent to the assistance feature is the primary data visualization component: the Irrigation Need Map. This map renders critical operational data by displaying Liters per Square Meter (l/m2) required for each agricultural plot/parcel.

- III.

- Alert System and Forecasting

A crucial feature of the dashboard is the integrated Alert System. Plots exhibiting critically high or excessive water requirements are flagged with a Red Alert Status.

These high-priority plots are immediately mirrored in the lower-right section of the screen, designated as the Acute Need Plots Alert Panel. This panel provides a focused and immediate list of parcels demanding the most urgent attention, ensuring rapid decision-making.

Finally, the upper-right section of the main content area is dedicated to proactive resource management by displaying the Upcoming Week’s Rain Forecast, which informs strategic irrigation planning.

The comparative cost–benefit analysis for irrigation optimization in vineyards was developed based on the national reference framework provided by the 2024 Results Report (Harvest 2023) of REDES TECO Viña, published by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food of Spain [10]. This report applies to the international agribenchmark (TIPI-CAL, Technology Impact and Policy Impact Calculations) methodology [29], which standardizes the techno-economic indicators of typical vineyard production systems across different regions of the country. This approach facilitates the comparison of profitability among various management and irrigation strategies and provides a robust foundation for assessing the potential impact of artificial intelligence (AI) tools aimed at enhancing water use efficiency. The methodological development presented in this work forms the scientific basis of the CONTROLHYDRO project, funded by the Government of Aragon through the “Grupos Operativos” program, aimed at advancing precision irrigation technologies for sustainable viticulture.

3.1. Methodological Framework

The TIPI-CAL model assesses profitability through three benefit levels:

Effective benefit (short-term profitability)—calculated as total revenues minus effective costs.

Operating account benefit (OAB) (medium-term profitability)—which also deducts depreciation or non-effective costs.

Net benefit (long-term profitability)—incorporating opportunity costs of land, family labor, and own capital.

This structure enables the quantification of cost savings and productivity gains derived from the implementation of intelligent precision irrigation systems.

3.2. Comparative Cost Structure

The TECO Viña dataset distinguishes between rainfed and irrigated vineyards, further subdivided by training systems (trellis, bush, and pergola).

In rainfed vineyards, yields ranged from 0 to 13 tons per hectare (t/ha), with revenues between EUR 250 and EUR 2500 per ton, depending on the region and designation of origin. Input costs varied from EUR 250 to 3800 EUR/ha, while operational costs fluctuated between 1600 EUR and 10,000 EUR/ha, depending on the degree of mechanization and topographic conditions. The average total production cost was approximately 3700 EUR/ha, reaching values above 20,000 EUR/ha in intensive systems located in the humid northern regions (e.g., Galicia).

In irrigated vineyards, yields were considerably higher, ranging from 4 to 19 t/ha, although the average grape price was generally lower (typically below 600 EUR/t), with maximum values for Albariño around 2200 EUR/t. Input costs ranged between 400 EUR and 1200 EUR/ha, except in intensive systems (exceeding 2600 EUR/ha). The energy source was a key determinant of irrigation costs: holdings employing photovoltaic energy (such as exploitation 40-CLM_M) reported significant reductions compared to those dependent on diesel fuel. Overall, total production costs for irrigated systems ranged from 3500 EUR to 6700 EUR/ha, with intensive cases exceeding 19,000 EUR/ha.

Only high-quality varietal systems—such as Macabeo and Tempranillo in La Rioja and Castilla y León and Albariño in Galicia—showed positive long-term net benefits, highlighting the impact of the added value associated with the designation of origin.

3.3. Comparative Discussion with Conventional Irrigation Practices

A comparative analysis against conventional irrigation practices highlights the added value of the ViñAI methodology. As highlighted by Suciu et al. (2019), traditional irrigation strategies are insufficient under current climate variability, and automated systems capable of real-time data integration are essential to maintain crop performance and resource efficiency [30]. Traditional irrigation in Mediterranean vineyards is typically based on fixed schedules, grower intuition, and visual assessment of vine stress, which often results in suboptimal water allocation and substantial variability in water use efficiency. In contrast, ViñAI applies artificial intelligence specifically to regulated deficit irrigation, enabling dynamic adjustment of water doses according to climatic demand, predicted soil moisture trajectories, and cultivar-level physiological criteria. This data-driven regulation aligns with evidence from previous studies showing that controlled deficit irrigation can reduce water use by 20 to 40 percent while maintaining or improving fruit quality. Regarding technological maturity, conventional scheduling relies on well-established but low-sophistication procedures, whereas ViñAI builds upon widely validated machine learning algorithms and openly accessible environmental datasets, making the system technically mature yet more advanced in its analytical capability. In terms of usage cost, traditional systems incur minimal digital investment but often lead to higher operational costs due to inefficient water and energy use; ViñAI, by contrast, leverages open-data inputs and does not require dense sensor networks, reducing implementation costs while improving irrigation efficiency. Finally, operational difficulty is substantially lowered: whereas conventional irrigation demands continuous field inspection and manual decision making, ViñAI automates recommendations, provides clear decision rationales, and reduces the cognitive load on vineyard managers. Altogether, the methodology offers a more efficient, scalable, and sustainable alternative to existing irrigation practices. As noted by Mirás-Avalos and Silva Araujo (2021), future innovation in vineyard water management depends on developing scalable monitoring systems that leverage remote sensing and machine learning [31]. The ViñAI framework contributes to this emerging direction by providing an AI-based methodology adaptable to sensor-sparse contexts.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a novel approach to deficit irrigation management in vineyards through the integration of artificial intelligence models, open environmental data, and, potentially, in-field sensor measurements. The developed tool successfully generates precise irrigation recommendations by dynamically predicting vine water requirements under varying climatic and soil conditions. The ViñAI tool demonstrated robust performance in modeling complex interactions between environmental variables and vine water status, offering a data-driven alternative to conventional irrigation practices and, more specially, to deficit irrigation systems.

Field validation results indicate that the AI-assisted system can significantly improve water use efficiency while supporting the agronomic goals of maintaining or enhancing grape quality. The potential integration of real-time sensor data with open-access sources enables scalable deployment across different vineyard settings, making the tool adaptable to a wide range of climatic and management conditions. These findings support the potential of digital technologies to advance sustainable water management in vineyards and contribute to climate-resilient wine production systems.

Furthermore, AI models require continuous updating to maintain accuracy across different phenological stages, soil conditions, and climatic specs, adding complexity to system maintenance and scalability.

Despite these challenges, the opportunities presented by this approach are significant. The ability to remotely deploy the tool in sensor-sparse regions by relying primarily on open-access data offers a scalable path for wider adoption, especially in resource-limited or emerging wine-producing areas.

In future work, the ViñAI methodology will be extended to subsequent growing seasons by directly implementing the algorithm’s irrigation recommendations throughout the full cycle. The outputs will then be compared with actual grape production and quality metrics to determine whether the results are consistent with values reported in the literature for deficit irrigation strategies. Future work will focus on broader testing across multiple geographic regions, including remote deployment of the tool in vineyards with sensors not necessarily implemented at field level. Additionally, future developments will incorporate dynamic electricity tariff systems to enable cost-optimized irrigation scheduling, integrating real-time energy prices to account for pumping costs and improve operational efficiency. Moreover, the planned integration of real-time electricity pricing into the decision-making algorithm opens new avenues for cost-optimized irrigation, enabling growers to minimize pumping costs by scheduling irrigation during off-peak tariff periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G. (Esteban Gutiérrez) and D.R.-B.; methodology, E.G. (Esteban Gutiérrez), D.R.-B., M.C., J.A., I.L., E.G. (Eduardo García) and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G. (Esteban Gutiérrez), D.R.-B., D.Z.-V., M.C., J.A., I.L., E.G. (Eduardo García) and A.G.; writing—review and editing, D.Z.-V.; supervision, D.Z.-V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out within the framework of the CONTROLHYDRO project (Ref.: GOP2025000400), funded by the Government of Aragon through the “Grupos Operativos” program, which supports innovation and sustainable resource management in the agri-food sector. Additional support was provided by the CIRCE Technological Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Viñas del Vero, Gonzalez-Byass, Zaragoza Municipality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OIV | International Organisation of Vine and Wine |

| UN | United Nations |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ET | Evapotranspiration |

| WUE | Water Use Efficiency |

| SiAR | Sistema de Información Agroclimática para el Regadío |

| OAB | Operating Account Benefit |

| RDI | Regulated Deficit Irrigation |

| FC | Field Capacity |

| Kc | Crop coefficient |

References

- Cherlet, M.; Hutchinson, C.; Reynolds, J.; Hill, J.; Sommer, S.; von Maltitz, G. World Atlas of Desertification. 2018. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC111155 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- OIV State of the World Vine and Wine Sector in 2024. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/sites/default/files/2025-04/OIV-State_of_the_World_Vine-and-Wine-Sector-in-2024.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ministerio de Agricultura Vitivinicultura. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/agricultura/temas/producciones-agricolas/vitivinicultura/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Phogat, V.; Petrie, P.R.; Bonada, M.; Collins, C. Regional Dynamics in Evapotranspiration Components, Crop Coefficients, and Water Productivity of Vineyards. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 322, 109955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gao, L.; Hou, X.; Hao, W.; Nangia, V.; Gong, D. Vine Age, Variety and Planting Density Influencing the Effects of Water Supply on Yield and Quality of Wine Grapes—A Meta-Analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Kang, J.; Du, T.; Ding, R.; Dai, Z.; Kong, J.; Li, Z.; Kang, S. Alleviating Drought and Heat Stress: A Root-Canopy Coordination Irrigation Strategy Synergistically Elevating Grapevine Yield, Quality, and Water Productivity. Agric. Meteorol. 2026, 376, 110912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florea, A.C.; Sumedrea, D.I.; Rodino, S.; Ion, M.; Dragomir, V.; Dumitru, A.-M.; Pîrcalabu, L.; Dinu, D.G. The Impact of Climate Change on Eastern European Viticulture: A Review of Smart Irrigation and Water Management Strategies. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, I.; Sanz, F.; Perez, D.; Yeves, A.; Martinez, A.; Chirivella, C.; Bonet, L.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Manejo Del Agua y La Vegetación En El Viñedo Mediterráneo; Cajamar Caja Rural: Almería, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.; Diverres, G.; Karkee, M.; Zhang, Q.; Keller, M. Decision-Support System for Precision Regulated Deficit Irrigation Management for Wine Grapes. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 208, 107777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA). Redes TECO: Viña–Informe de Resultados 2024 (Vendimia 2023). Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/dam/mapa/contenido/agricultura/temas/producciones-agricolas/vitivinicultura/redes-teco-vina/informe-de-resultados_redes-teco-vina_2024.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Fereres, E.; Soriano, M.A. Deficit Irrigation for Reducing Agricultural Water Use. J. Exp. Bot. 2006, 58, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Interactive Effects of Deficit Irrigation and Shoot and Cluster Thinning on Grapevine Cv. Tempranillo. Water Relations, Vine Performance and Berry and Wine Composition. Irrig. Sci. 2011, 29, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junta de Extremadura Manual Práctico de Riego. Vid Para Vinificación. Available online: https://cicytex.juntaex.es/-/manual-practico-de-riego-vid-para-vinificacion (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Bellvert, J.; Mata, M.; Vallverdú, X.; Paris, C.; Marsal, J. Optimizing Precision Irrigation of a Vineyard to Improve Water Use Efficiency and Profitability by Using a Decision-Oriented Vine Water Consumption Model. Precis. Agric. 2021, 22, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.M.; Zarrouk, O.; Francisco, R.; Costa, J.M.; Santos, T.; Regalado, A.P.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Lopes, C.M. Grapevine under Deficit Irrigation: Hints from Physiological and Molecular Data. Ann. Bot. 2010, 105, 661–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OĞUZTÜRK, G.E. AI-Driven Irrigation Systems for Sustainable Water Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analytical Insights. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, N.C.; Batinas, B.I.; Ursu, C.; Crainiciuc, F.N. Integrating Artificial Intelligence into an Automated Irrigation System. Sensors 2025, 25, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alatzas, A.; Theocharis, S.; Miliordos, D.-E.; Leontaridou, K.; Kanellis, A.K.; Kotseridis, Y.; Hatzopoulos, P.; Koundouras, S. The Effect of Water Deficit on Two Greek Vitis vinifera L. Cultivars: Physiology, Grape Composition and Gene Expression during Berry Development. Plants 2021, 10, 1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Q.; Shen, T.; Xu, M.; Fang, Y.; Ju, Y. Effects of Regulated Deficit Irrigation at Different Times on Organic Acids, Phenolics and Antioxidant Capacity of Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 345, 114143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almu, A.; Yunusa, A. An Improved Web-Based Weather Information Retrieval Application. Int. J. Data Inform. Intell. Comput. 2025, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadar Maideen, A.A.; Mohammed Nawaz Basha, S.; Afsal Basha, V.A. Effective Utilisation of AI to Improve Global Warming Mitigation Strategies through Predictive Climate Modelling. Int. J. Data Inform. Intell. Comput. 2024, 3, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renju, K.; Brunda, V. Optimizing Crop Yield Prediction through Multiple Models: An Ensemble Stacking Approach. Int. J. Data Inform. Intell. Comput. 2024, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA). Sistema de Información Agroclimática Para El Regadio (SiAR). Available online: http://www.siar.es (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET). Available online: https://www.aemet.es (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Gaudin, R.; Roux, S.; Tisseyre, B. Linking the Transpirable Soil Water Content of a Vineyard to Predawn Leaf Water Potential Measurements. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 182, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team PyCaret—Low-Code Machine Learning Library for Python. Available online: https://pycaret.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Saha, J. Regression Metrics Explained: MAE, RMSE, R2, and Beyond. Available online: https://joyoshish.github.io/blog/2025/ds010-heartofml-regression4/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Agribenchmark Cash Crop–Terminology and Methodology (TIPI-CAL). Available online: http://www.agribenchmark.org/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Suciu, G.; Ușurelu, T.; Bălăceanu, C.M.; Anwar, M. Adaptation of Irrigation Systems to Current Climate Changes. In Business Information Systems Workshops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 534–549. [Google Scholar]

- Mirás-Avalos, J.; Araujo, E. Optimization of Vineyard Water Management: Challenges, Strategies, and Perspectives. Water 2021, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).