Abstract

Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB) is a technique that utilizes mine tailings, mining-process water, and a binder, typically Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), to backfill the opening created in underground mining. However, the use of cement in CPB increases operational costs and has adverse environmental effects. To mitigate these effects, eco-friendly natural pozzolan can be used as a partial replacement for OPC, thereby reducing its consumption and environmental impact. The volcanic region of western Saudi Arabia contains extensive deposits of Saudi natural pozzolan (SNP), which is a promising candidate for this purpose. This study evaluates the mechanical performance of CPB under four scenarios: a control mixture (CTRL), a mixture with untreated SNP (UT), and mixtures with activated SNP, specifically heat-treated (HT) and mechanically treated (MT). Each scenario was tested at replacement levels of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% of OPC. The performance was assessed using Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS) with Elastic Modulus (E), Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV), and Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS/Brazilian) tests. The results indicate that the HT scenario at a 5% replacement level delivered the highest performance, slightly outperforming the MT scenario. Both activated scenarios (HT and MT) significantly surpassed the untreated mixture (UT). Overall, the HT scenario proved to be the most effective among all CPB mixtures tested. XRD diffractogram analysis supported HT as the material with the highest strength performance due to the occurrence of more strength phases than other CPB materials, including Alite, Quartz, and Calcite. While UCS and UPV showed a positive correlation across all CPB materials, the relationship between UPV and the modulus of elasticity (E) demonstrated a low correlation. The findings suggest that using activated SNP materials can enhance CPB sustainability by lowering cement demand, stabilizing operating costs, and reducing environmental impacts.

1. Introduction

Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB) is a widely used method in underground mining that utilizes waste materials from mineral processing, including mill tailings and process water. Globally, the mining industry produces large quantities of mining waste, with annual tailings generation estimated at 13 billion tons and projected to exceed 100 billion tons from ongoing mineral and metal operations [1,2,3]. The utilization of these tailings in CPB enhances mining efficiency and safety by improving ground stability, mitigating ore dilution, and reducing surface waste disposal. This practice can potentially prevent environmental hazards, such as tailings dam collapses and acid mine drainage [4,5,6,7].

In a typical CPB mixture, Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) serves as a primary hydraulic binder, constituting 2–10 wt.% of a blend that is 70–85 wt.% tailings and 15–30 wt.% process water [8,9,10,11,12,13]. OPC is crucial for achieving the required strength for safe and economical operations [14,15]. However, its use presents significant economic and environmental challenges. Cement accounts for 75–80% of the total cost of the paste backfill process [16]. Furthermore, OPC production is energy-intensive, involving high-temperature calcination that releases approximately 0.54–0.8 tons of CO2 per ton of OPC and generates Cement Kiln Dust (CKD) at a rate of 15–20% of cement produced [17,18,19,20].

A sustainable mining operation involves reducing cost and embodied CO2 by partially substituting OPC with Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs) like fly ash, blast furnace slag, and natural pozzolans [21,22,23]. Nonetheless, the supply of predominant SCMs is limited, constraining their ability to meet market demand [24].

Natural pozzolans present a viable alternative to fill this gap. Saudi Arabia possesses extensive unexplored deposits of natural pozzolanic materials within its western volcanic region (Harrats), covering an area of 180,000 km2, which are suitable for use as SCMs [25,26,27]. The use of such eco-friendly materials, such as SNP, as a binder in CPB promotes sustainable mining by reducing carbon emissions and can also enhance acid resistance in metalliferous mining environments [28,29].

Although Harrats are extensive sources of SNPs, numerous regions, including Harrat Kishb, Buqum, Nawasif, and Al-Harrah, remain unexamined for their suitability as pozzolanic sources [30,31,32]. A significant challenge is the variable chemical composition and low reactivity of raw Saudi Natural Pozzolan (SNP), which often requires activation to function effectively as a binder [33]. Studies have shown that activation methods, such as thermal treatment at 550–750 °C or mechanical grinding to fine particle sizes of 38 µm and 20 µm, can significantly enhance the pozzolanic reactivity of SNP [33,34].

While there is some research on the direct application of raw natural pozzolan in CPB [9,28,35,36,37], the use of activated natural pozzolans remains unexplored. Previous studies on treated materials in CPB have primarily focused on artificial or by-product pozzolans, such as alkali-activated slag with silica fume [38], a composite alkaline activator [39], and an alkali-activated Bayer red mud [40].

Furthermore, the application of SNPs has been primarily utilized as a partial substitute for cement in concrete applications, with attention given to its activation and characterization [26,33,34,41,42,43,44]. However, the specific potential of thermally or mechanically activated SNPs to enhance the quality and performance of CPB has not been adequately investigated.

This study aims to evaluate the mechanical performance of CPB mixtures incorporating untreated, thermally activated, and mechanically activated SNP as a partial replacement for OPC. This study assesses the key mechanical properties (Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV), Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS) with Elastic Modulus (E), and Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS/BTS) under different replacement levels and curing times of 7, 14, and 28 days. The activated SNP scenarios focus on optimal treatments, including heat treatment at 600 °C and mechanical treatment by grinding for 6 h, to achieve a fineness of 5.8 µm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB) samples were prepared from a mixture of binder (Pozzolan and/or OPC), tailings (fine and coarse), and mining-process water (Figure 1). The binders consist of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) and Saudi Natural Pozzolan (SNP), which was obtained from a quarry in the Madinah region, while the cement was obtained from a local supplier. The tailings and process water, representing typical mining waste materials, were supplied by Maaden Barrick Copper Company (MBCC) from their Jabal Sayid underground copper mine in the western region of Saudi Arabia.

Figure 1.

Materials used for the preparation of CPB mixtures.

Special measures were taken to standardize both the coarse and fine tailings prior to their use in CPB mixtures. The tailings were first sun-dried for 24 h to reduce moisture heterogeneity in the material. The water content was then measured to account for its contribution to the overall water balance. Determining the water content is crucial for accurately calculating the volume of process water used during mining and added during the mixing process. Finally, the tailings sample was sieved to remove any small stones that could contaminate the sample and affect its consistency.

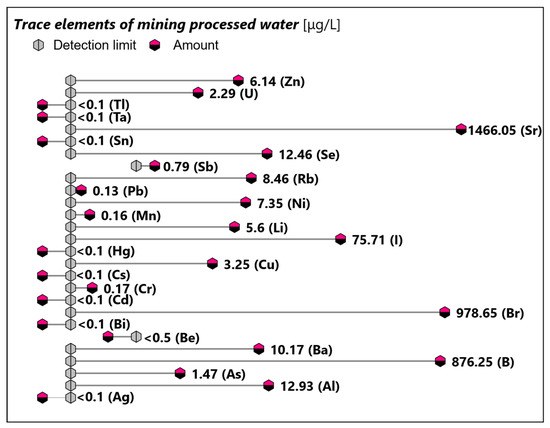

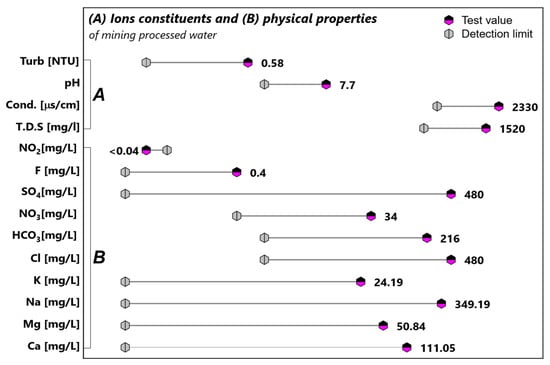

The chemical composition of all raw materials was quantified using Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS). The analyzed materials included the binders (OPC, untreated [UT], heat-treated [HT], and mechanically treated [MT] pozzolans) and the tailings (fine and coarse). The chemical composition of solid materials is provided in Table 1. The characteristics of mining-process water are given in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of raw materials used in the CPB mixing.

Figure 2.

Trace elements of mining-process water used in CPB.

Figure 3.

Ion constituents and physical properties of mining-process water.

2.2. Activated Saudi Natural Pozzolan

Saudi Natural Pozzolan (SNP) used in the mixture is activated before its use in CPB. Evaluation of the activation was based on the Strength Activity Index (SAI) as per ASTM C311M [45]. The activation methods consisted of thermal treatment (HT) and mechanical treatment (MT). The result of the treatment indicated that HT at a temperature of 600 °C yielded the highest Strength Activity Index (SAI), compared to other temperatures tested (ranging from 500 °C to 1000 °C). For MT, grinding for 6 h yielded the highest SAI among the other grinding durations, which ranged from 2 to 24 h. The mechanically treated SNP achieved a higher SAI than the heat-treated SNP. The activated SNP (either MT or HT) was incorporated into the CPB mixtures as a partial cement replacement at portions ranging from 5% to 20% of the total binder.

Several studies in CPB investigated higher cement replacement levels using natural pozzolan, ranging from 10 to 40 wt.% of total binder [28,35]. However, these studies indicated a loss in paste strength beyond 20% replacement. Therefore, this study focuses on lower dosage, limited to a maximum of 20% replacement conditions. Since the material usage is similar to that from the local underground mine, this investigation will assess the competitiveness of this experiment compared to standard mining practices, particularly by evaluating scenarios that use 100% OPC.

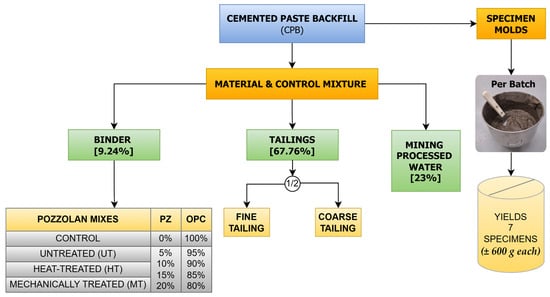

2.3. Mixture Design and Sample Preparation

The Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB) mixture was prepared to a total weight of 100%. The binder content was fixed at 9.24 wt.%, with Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) as the primary component. The control mix used the OPC, which constituted 9.24% by weight. In another mixture, OPC was partially replaced by SNP at specific percentages. The tailings content was 67.76 wt.%, divided equally between fine and coarse fractions (33.88 wt.% each). Mining-process water was maintained at 23 wt.%, with slight adjustments made to account for the moisture content of the tailings (Figure 4) and a total of 117 cylindrical specimens were prepared for testing. The specimens were cast in molds with dimensions of 130 mm in height and 52 mm in diameter. Each mold held approximately 600 g of mortar. The mixing bowl had a capacity sufficient to produce seven specimens per batch. Three samples for each mixture were prepared, and they were tested at curing ages of 7, 14, and 28 days, as detailed in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Mixture design flow chart with percentage of materials used in CPB (Four Scenarios).

Table 2.

Mixed proportions of the Control (CTRL), Untreated (UT), Heat-treated SNP (HT), and Mechanically treated SNP (MT).

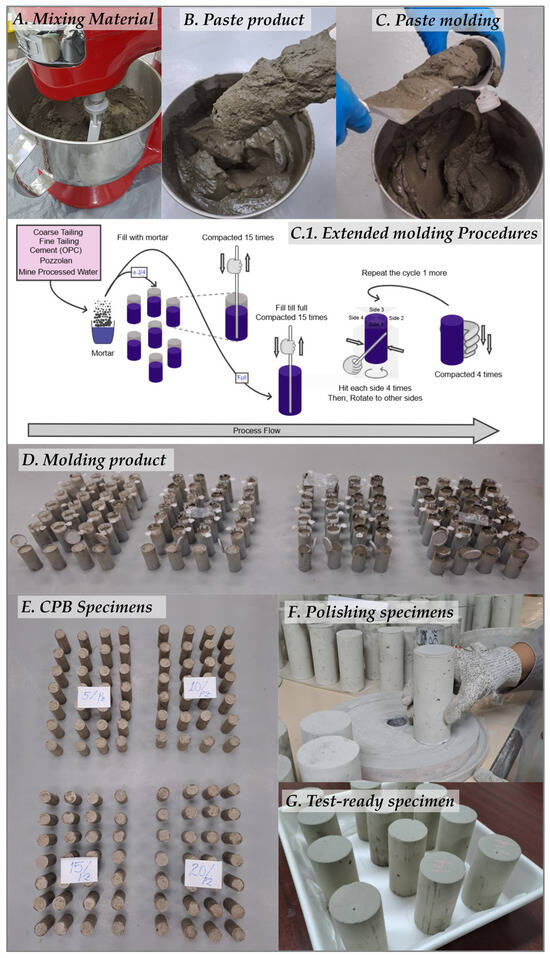

2.4. Mixing and Specimen Casting Procedures

The prepared raw materials, including binder (cement and pozzolan), tailings (fine and coarse), and mining-process water, were weighed according to the designated mixed designs and assembled near the mixer. Then, the mixing process was conducted (Figure 5A) as follows:

Figure 5.

CPB Sample preparation procedures for the mechanical performance test.

- Dry mixing: The solid components, including cement, pozzolan, and tailings, were placed into the mixing bowl. The mixer was then operated for 60 s, with the speed gradually increasing from 1 to 3 to achieve a homogeneous dry blend.

- Wet mixing: Following the dry mixing stage, the mixer was resumed, and the speed was gradually increased from 5 to 7. The pre-measured mining-processed water was then added slowly over 60 s to minimize splashing. The mixer was then paused for approximately one minute, during which the sides and bottom of the bowl were scraped manually with a spatula to incorporate any adhered material back into the mixture.

- Final Homogenization: the mixture was blended at high speed (speed 7) for an additional 60 s to achieve a consistent and homogeneous paste. The mixing process was then ended, and the resulting fresh paste was ready for molding (Figure 5B).

- Paste Molding and Compaction: Before placing mortar into the cylindrical mold, the inner surface of the mold was lightly oiled to facilitate demolding. Each mixing batch was sufficient to prepare seven cylindrical specimens. Initially, each mold was filled to approximately three-quarters of its volume, and then completely. After each filling stage, the mortar was compacted with 15 strokes using an iron rod. Afterward, each mold was gently tapped four times on the side and compacted again with four strokes to release entrapped air. This entire tapping and compaction cycle was repeated once more to ensure complete compaction and the removal of entrapped air (Figure 5C).

After molding, all specimens were arranged according to their pozzolan content (Figure 5D). After a 24 h curing period, the specimens were demolded (Figure 5E), their surfaces were polished according to standard procedures (Figure 5F), and they were prepared for subsequent mechanical testing, including Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV), Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS), and Brazilian Tensile Strength (BTS) (Figure 5G).

2.5. Experimental Testing

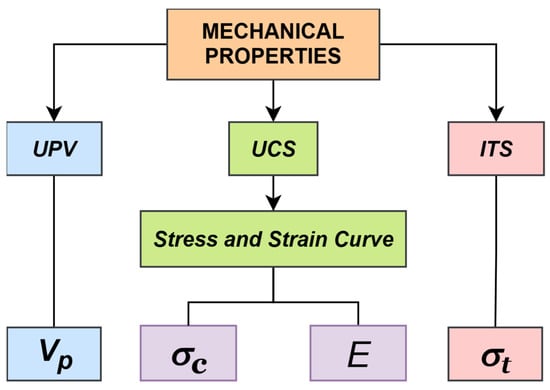

This study evaluated CPB performance using three techniques: Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV), Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS), and Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS), also known as Brazilian Tensile Strength (BTS) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Experimental test framework: ultrasonic pulse velocity (Vp), uniaxial compressive strength (σc), elastic modulus (E), tensile strength (σt).

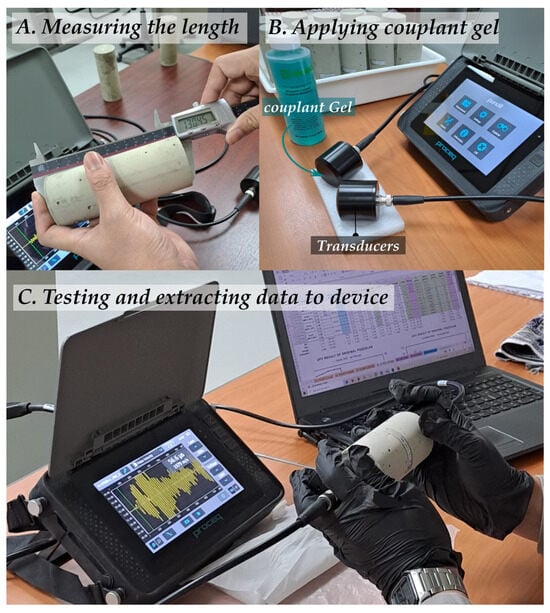

2.5.1. Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (UPV)

UPV is a non-destructive testing (NDT) method used to assess material homogeneity and quality. In this test, two transducers are placed on opposite sides of the specimen. One transducer emits an ultrasonic wave that travels through the specimen to the receiving transducer. The P-wave velocity (Vp) is calculated by dividing the manually measured path length (L) (Figure 7A) by the measured travel time (t) (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Experimental setup of UPV testing for CPB specimens.

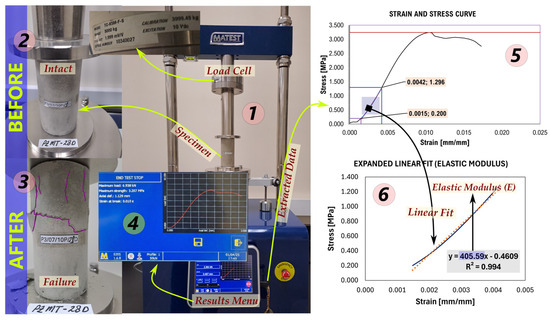

2.5.2. Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS)

All specimens were tested for UCS using a Matest S205M-Unitronic 50 kN (manufactured by Matest, Arcore, Italy), with a 50 kN load cell (Figure 8). Specimens preparation conformed to the ASTM C39 standards for the height-to-diameter ratio [46]. The machine recorded a graph of load (in kN) versus axial deformation (in mm) for each test. The maximum compressive strength (σc) was determined from recorded data. The modulus of elasticity or Young’s modulus (E) was derived from the strain-stress curve using a linear regression applied to the linear-elastic portion of the data.

Figure 8.

UCS test framework: (1) Compressive machine equipped with a 50 kN load cell; (2) Intact specimen prior to loading; (3) Specimen failure mode after testing; (4) Test result showing load and deformation record; (5) Strain and stress curve derived from extracted data; (6) Determination of elastic modulus (E) using linear fit.

2.5.3. Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS)

The ITS test, also known as Brazilian Tensile Strength (BTS), provides an indirect estimate of tensile strength (σt) by applying a diametrical compression load to a cylinder specimen (Figure 9). Testing was conducted in accordance with ASTM D3967 [47].

Figure 9.

Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS/BTS) test operation.

3. Results and Discussion

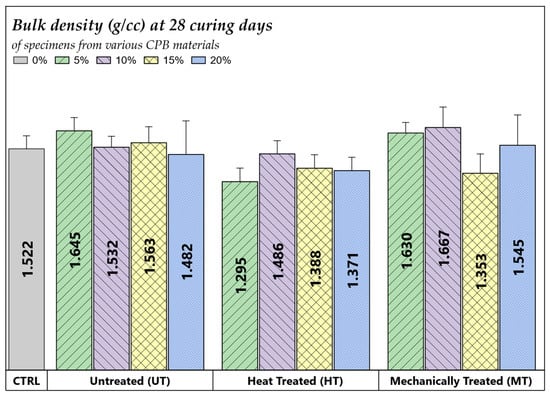

3.1. Bulk Density

The bulk density of the CPB samples was determined at 28 days of curing, in accordance with ASTM C642 [48]. Results from three samples per mixture are presented in Figure 10. The control mixture (CTRL) contained 100% OPC and 0% SNP. Other than Control, the CPB uses SNP under three conditions: Untreated (UT), with a Blaine fineness of 0.37 m2/g; Heat-treated (HT), thermally soaked at 600 °C for 30 min; mechanically treated (MT), ground for 6 h to a Blaine fineness of 2.52 m2/g or a mean particle size (d50) of 5.8 µm. The selection of a 600 °C thermal treatment in this research was based on previous results indicating it as a practical, energy-efficient activation threshold that partially enhances the pozzolanic reactivity of natural materials, offering a balance between improved mechanical performance and reduced processing costs.

Figure 10.

Average bulk densities of CPB for control mixture (CTRL), untreated (UT), heat treated (HT), and mechanically treated (MT) scenarios at 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% replacement (three trials of each specimen test).

The results show that the average bulk density ranged from 1.3 to 1.7 g/cc, depending on the dosage of each mix. The control mix (100% OPC) had a lower density, due to its relatively coarse particles (±15 µm) [49], than the UT and MT mixes. The lower MT dosage (5% and 10% replacement) exhibited higher density than UT, CTRL, and HT, due to the finer particle size in MT. Smaller particle size in UT and MT has increased density compared to the control mix due to three mechanisms: the filler effect [50,51]; microstructure densification [50,51,52,53]; and improved packing density [50].

In contrast, the HT mixtures showed slightly lower density than the CTRL due to the lower specific gravity of the thermally treated material and higher water demand, which often increases the mixture’s porosity [54,55]. Increasing the dosage to the optimal 20% using MT CPB might further enhance density.

3.2. Strain-Stress Curves and Elastic Moduli

Analysis of compressive machine data output yielded strain-stress curves (SSCs) that were used to identify the ultimate compressive strength (σc) and modulus of elasticity (E), which represent the stiffness of the CPB.

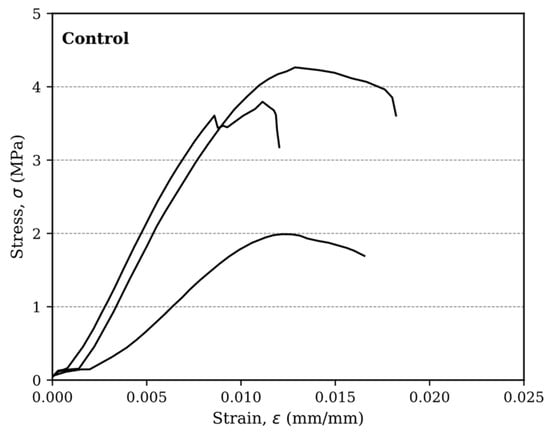

3.2.1. Elastic Moduli of the Control Specimens

The elastic modulus of the control samples, derived from SSCs similar to those in Figure 11, generally increased from 7 to 28 curing days, indicating a progressive stiffening. Despite the average value being higher at 7 days, due to the presence of outlier data points, a clear trend of increasing stiffness with curing age was observed for most of the CTRL specimens (Table 3).

Figure 11.

Strain-Stress Curve (SSC) of the three different CTRL specimens at 28 curing days.

Table 3.

The elastic modulus (E) value of the CTRL three specimens for each curing period.

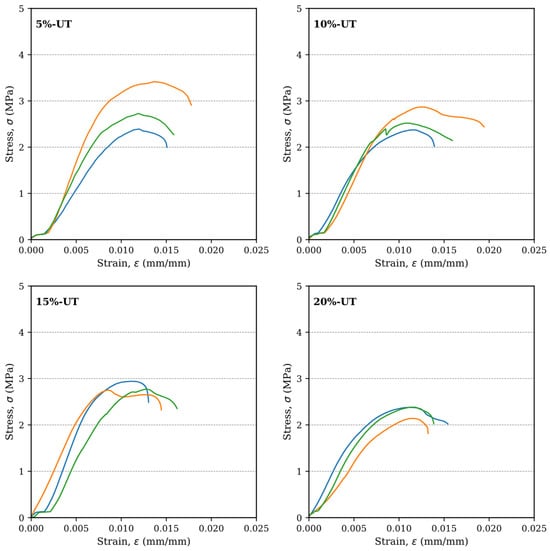

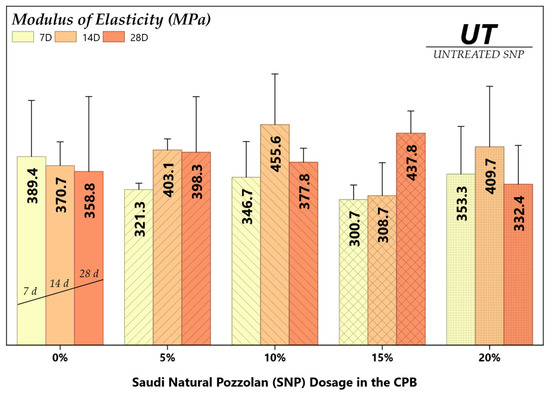

3.2.2. Elastic Moduli of the Untreated (UT) Scenario

The elastic moduli for UT specimens, derived from strain-stress curves (SSCs), were illustrated in Figure 12 and detailed in Table 4. Meanwhile, the average illustrations are shown in Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Strain-Stress Curves of the UT scenario at 28 days; Each color in each UT dosage corresponds to one of the three specimens.

Table 4.

Elastic moduli for untreated SNP specimens from 0% to 20% at different curing days.

Figure 13.

The average elastic modulus of UT specimens at different curing days for various replacement conditions.

At the early curing age, the CTRL mixture was the stiffest. However, by 14 days, the UT with 10% replacement exhibited a 23% higher elastic modulus (E) than CTRL. At 28 days, the UT (15%) mixture showed a higher E than CTRL, which was consistent with the 14-day observation.

3.2.3. Elastic Moduli of the Heat-Treated (HT) Scenario

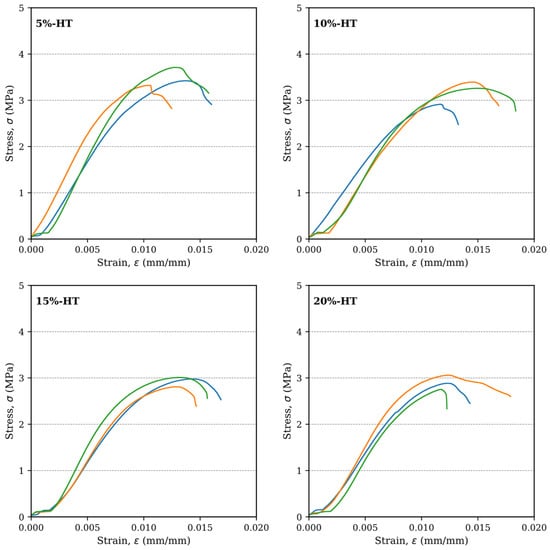

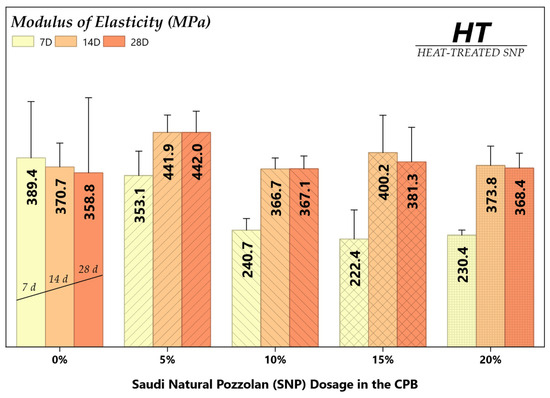

The elastic moduli for HT samples were derived from SSCs, as shown in Figure 14 and Table 5. Meanwhile, the average E was illustrated in Figure 15. They show that CTRL was the stiffest at early ages. However, by 14 and 28 days, the HT (5%) mixture demonstrated a 19% and 23% higher stiffness than CTRL materials at 7 days of curing, respectively. The other HT dosages (10–20%) showed E values approximately 40% lower than CTRL at early curing periods.

Figure 14.

Strain-Stress Curves (SSC) of the HT scenario at 28 days; Each color in each UT dosage corresponds to one of the three specimens.

Table 5.

Elastic moduli for heat-treated SNP specimens from 0% to 20% at different curing days.

Figure 15.

The average elastic modulus of HT specimens at different curing days for various replacement conditions.

3.2.4. Elastic Moduli of the Mechanically Treated (MT) Scenario

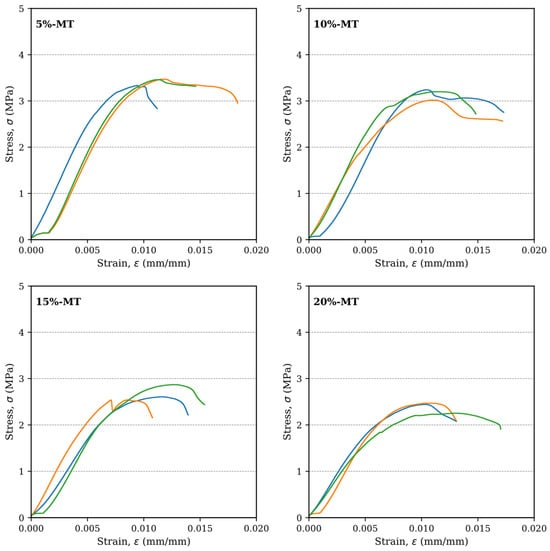

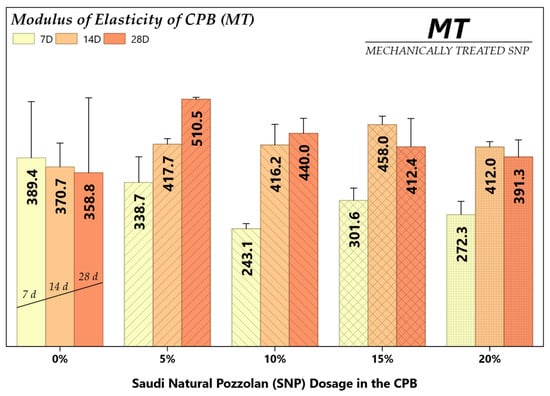

The elastic moduli for MT samples were derived from SSCs, as shown in Figure 16 and Table 6, followed a similar trend to that observed for UT and HT. Meanwhile, the average E values were illustrated in Figure 17. CTRL was the stiffest at an early curing age, but the MT (5%) mixture exceeded it by 19% at 14 days and by 42% at 28 days.

Figure 16.

Strain-Stress Curves (SSC) of the MT scenario at 28 days; Each color in each UT dosage corresponds to one of the three specimens.

Table 6.

Elastic moduli of mechanically treated SNP specimens from 0% to 20% at different curing days.

Figure 17.

The average elastic modulus of MT specimens at different curing days for various replacement conditions.

The CTRL mixture exhibited the highest initial E value among all treatments, due to the rapid hydration and the formation of Calcium Silicate Hydrate (C-S-H) gel [56].

Even though the Control mix exhibited high stiffness at an early age, UT, HT, and MT exceeded the CTRL’s stiffness at 14 and 28 days of curing. Specifically, UT (10%), HT (5%), and MT (5%) exhibited the highest elastic modulus values at 14 days, approximately 19% higher than those of the control mixture. At 28 days of curing, UT (15%), HT (5%), and MT (5%) had the highest elastic modulus, where UT (15%) and HT (5%) showed the highest stiffness, with MT (5%) exhibiting a 42% higher elastic modulus than the control mix.

3.3. Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS)

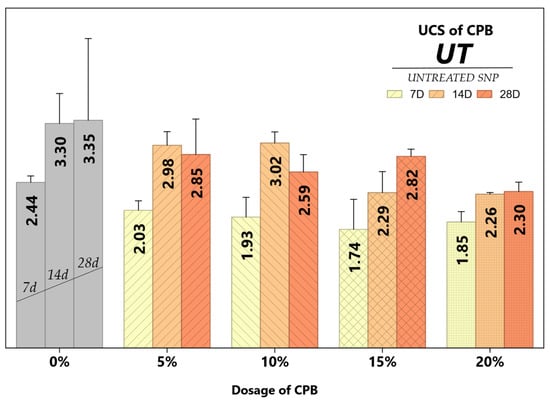

3.3.1. UCS of the Untreated (UT) Scenario

The average maximum strength (σc) was presented for the UT Scenario in Figure 18. The control mixes had the highest average compressive strength among all curing days. Among the UT mixtures, UT (5%) showed the highest strength at 7 and 28 days (2.03 MPa and 2.85 MPa, respectively), while UT (10%) was the highest at 14 days with 3.02 MPa. The lower early strength of pozzolan mixtures is due to clinker dilution and the delayed pozzolanic reaction, which increases early capillary porosity [57]. Although UT (5%) had the highest UT strength at 28 days, the slight difference of only 1% between UT (5%) and UT (15%) indicated that both of them are potentially suitable for practical applications.

Figure 18.

The average maximum strength of UT CPB at 7, 14, and 28 days for control (gray color), 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% replacement conditions.

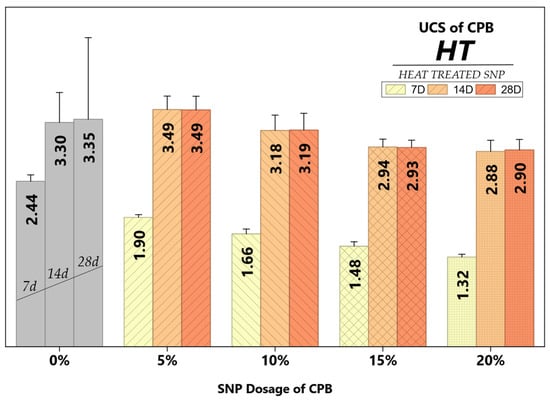

3.3.2. UCS of the Heat-Treated (HT) Scenario

Unlike the UT CPB specimens, the HT CPB specimens exhibited a more consistent strength development between 14 and 28 days, with a maximum difference of 2% for each dosage (Figure 19). HT (5%) achieved the highest strength among all HT dosages and exceeded the CTRL strength at 28 days. In contrast to the UT samples, the HT dosage above 5% progressively decreased the strength, with reductions of 9%, 16%, and 17% for the 10%, 15%, and 20% cement replacement, respectively.

Figure 19.

The average maximum strength of HT CPB at 7, 14, and 28 days for control (gray color) and various replacement conditions.

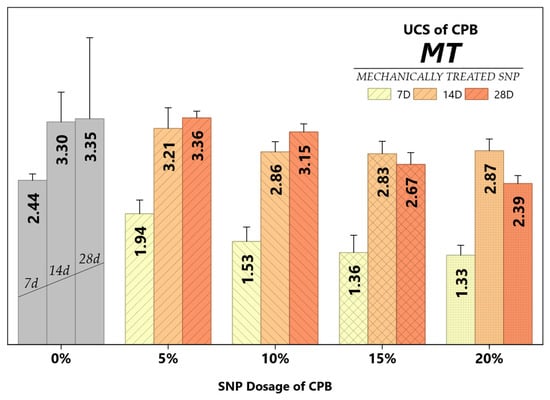

3.3.3. UCS of the Mechanically Treated (MT) Scenario

The UCS results for the mechanically treated CPB are shown in Figure 20. The early-age strength of MT CPB decreased with increasing MT dosages. The MT (5%) mixture, which had the highest strength among MT dosages at an early age, was 22% lower than CTRL at 7 days, corresponding to a decrease in strength from 2.44 MPa to 1.94 MPa. At later ages, the 5% and 10% replacements showed promising strength, with MT (5%) being nearly equivalent to CTRL at 28 days.

Figure 20.

The average of the maximum strength of MT CPB at 7, 14, and 28 days for control (gray color), 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% replacement conditions.

Both thermal and mechanical-activation treatments enhance the mechanical performance of CPB. Thermally treated SNP yielded the highest UCS across replacement levels, likely due to enhanced amorphous silica content and reactivity. Mechanical treatment also improved performance, though to a slightly lesser extent than thermal treatment. The strength gain from Untreated pozzolan at low dosages is attributed primarily to physical effects (packing and filler effects) rather than chemical activity.

3.4. Relationship Between Vp, UCS, and E

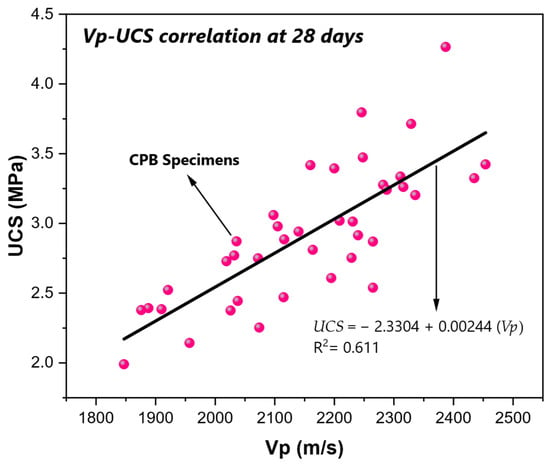

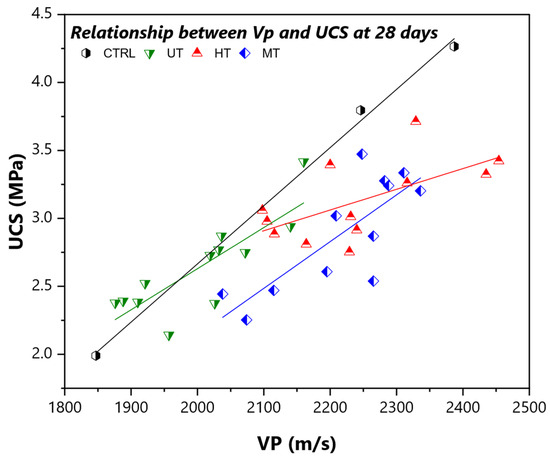

3.4.1. Relationship Between Vp and UCS at 28 Days

The linear fit between P-wave velocity (Vp) and UCS shows a positive correlation with an R2 of 61% (Figure 21), indicating that Vp is a moderately reliable non-destructive indicator for estimating CPB strength [58,59]. The moderate correlation can be attributed to the heterogeneity of CPB, which is composed of tailings, cement, and water.

Figure 21.

Relationship between pulse velocity (P-wave) and the strength of CPB.

Figure 22 illustrates the relationships between UCS and Vp for each material separately, while Table 7 presents the equations derived from the linear regression, with R2 values of 0.997 for CTRL, 0.682 for UT, 0.392 for HT, and 0.590 for MT. Although the HT mixture demonstrates weak correlation, the positive trend persists.

Figure 22.

Relationship between the P-wave and the strength of specimens of various CPB materials. The lines show the linear regression: black for CTRL, green for untreated (UT), red for heat-treated (HT), and blue for mechanically treated (MT).

Table 7.

The linear regression analysis (Equation and R2) of the P-Wave vs. UCS.

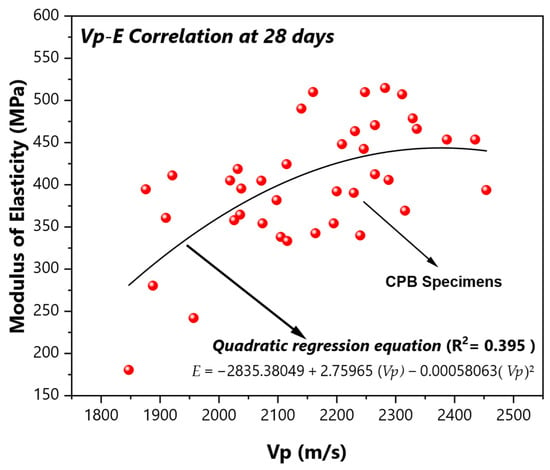

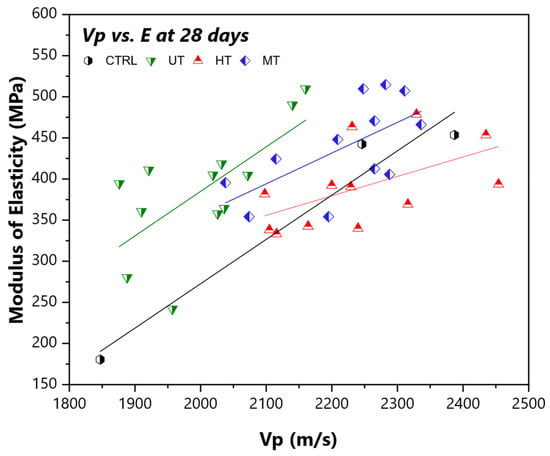

3.4.2. Relationship Between Vp and Modulus of Elasticity (E) at 28 Days

A correlation between the P-wave and elastic modulus was established using data from all types of CPB material. The quadratic regression yielded a low R2 value of approximately 0.40 (Figure 23), indicating that the UPV accounts for only about 40% of the variation in the elastic modulus. Analysis of each material type showed a weak correlation, with R2 values of 0.46 for UT, 0.31 for HT, and 0.40 for MT (Table 8 and Figure 24). Although a positive trend was observed, the low R2 values indicate that there is no significant correlation between Vp and E for these CPB materials. This low correlation is attributed to the composite and heterogeneous nature of CPB, where multiple factors beyond density influence the relationship between wave propagation and stiffness. Approximately 60% to 70% of the variation can be attributed to other factors, including:

Figure 23.

Pulse Velocity–Elastic Modulus Relationship of CPB.

Table 8.

The linear regression analysis (Equation and R2) of the P-Wave vs. E.

Figure 24.

Relationships of the P-wave velocity (Vp) and the elastic modulus (E) for various CPB materials. The lines show the linear regression: black for CTRL, green for untreated (UT), red for heat-treated (HT), and blue for mechanically treated (MT).

- Microstructure and Porosity: Pore size, distribution, and connectivity waves strongly influence both wave velocity and compressive strength [60].

- Material composition: binder type, aggregate size, and proportion of raw materials affect the hydration, formation of binding phases, and mechanical properties, leading to data scattering [61,62,63].

- Curing conditions: Temperature, humidity, and curing age impact hydration kinetics and the resulting microstructure [61,62,63].

- Moisture content/Drying: the amount of free and bound water in a specimen influences Vp; drying can decrease Vp due to microcracking and increased porosity [60].

- Heterogeneity: the mixing of diverse materials can lead to incomplete hydration and the existence of voids, which affect wave propagation and mechanical properties, reducing the reliability of empirical correlations [61].

The predictive ability could be improved through multivariate regression that incorporates these additional variables.

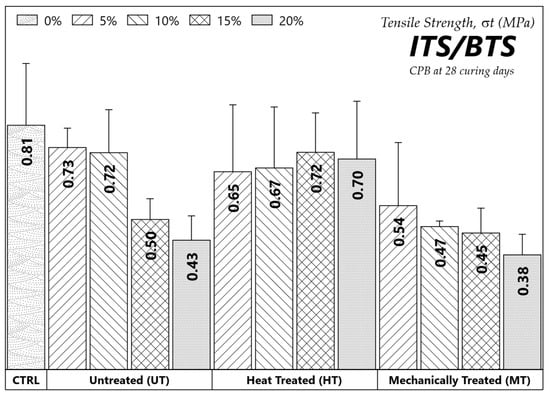

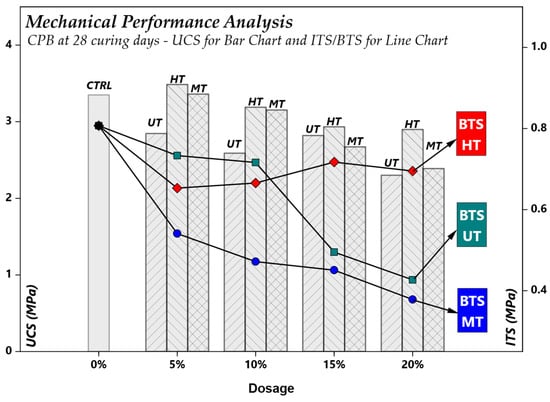

3.5. Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS/BTS)

Tensile strength is the primary reason for initial failure in CPB structures, such as during secondary stopes excavation, which is often initiated by tensile cracking [64]. Results of ITS at 28 curing days are shown in Figure 25 and Figure 26.

Figure 25.

Average tensile strength of CPB for the control (0% SNP) mixture (CTRL), untreated (UT), heat treated (HT), and mechanically treated (MT) scenarios at 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% replacement levels based on three specimens per mixture at 28 days.

Figure 26.

Comparison of the performance of the mechanical properties of the various CPB materials at maximum curing days (28 days), the line chart is BTS, while the bar chart is the UCS observation.

Experimental results from the indirect tensile strength test indicate that the tensile strength (σt) of the CTRL scenario is the highest among all tested CPB materials (σt ≥ 0.81 MPa). Moreover, increasing pozzolan dosage decreases the tensile strength of UT and MT. In contrast, HT increases the tensile strength from 0.65 MPa to 0.72 MPa for dosages ranging from 5% to 15%, with only a slight 3% decrease at the 20% dosage. The tensile strength of UT at 5% and 10% replacement was comparable to that of HT at 15% and 20%.

From a practical perspective, HT at 15–20% replacement is superior to UT, as it achieves a similar tensile strength (≅0.7 MPa) with a higher OPC substitution rate. The minimal strength difference between HT 15% and 20% suggests that the higher dosage is viable, with potential for long-term strength gain due to continued pozzolanic reaction and secondary C-S-H gel formation. Therefore, HT 20% replacement offers both cost savings and sustainability benefits in CPB applications, while maintaining the required mechanical integrity.

Finally, the primary mechanical performance of the CPB, UCS, and ITS was compared at 28 days of curing (Figure 26), with the listed key findings as follows:

- CTRL specimens exhibited the highest mechanical performance in both compressive and tensile strength.

- Among the treated Saudi Natural Pozzolan (SNP) mixtures, HT CPB showed the best UCS at all dosages, while its tensile strength is slightly lower at 5% and 10%. Increasing the dosage to 15% or 20% yields better compressive and tensile strength than MT and UT, indicating better bonding and matrix cohesion.

- Untreated pozzolan showed good tensile strength at 5% and 10%, despite a lower compressive strength than that of CTRL, HT, and MT.

- MT CPB exhibited competitive compressive strength at 5% dosage but demonstrated the lowest tensile strength among all treatments.

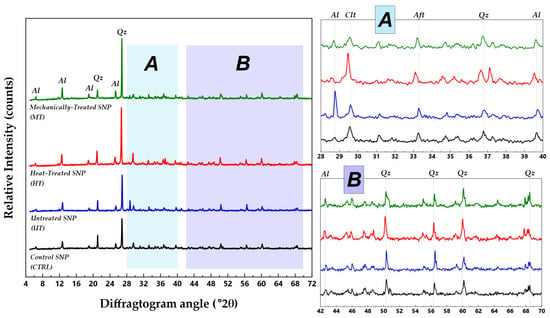

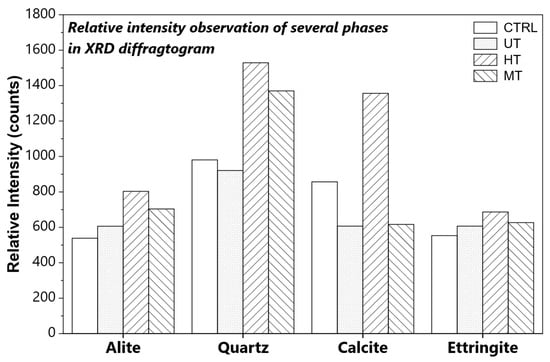

3.6. Microstructural Analysis

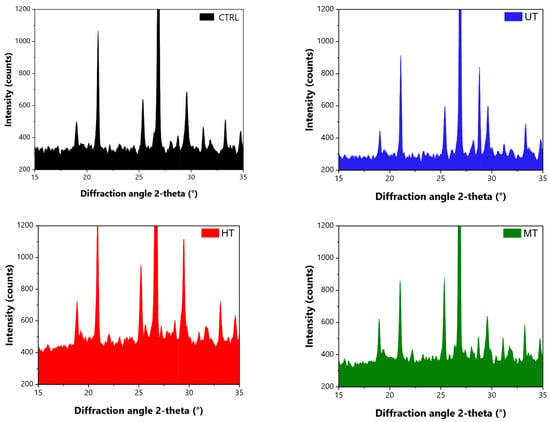

Microstructural analysis using XRD identified several phases in the tested CPB samples, including Alite or tricalcium silicate (C3S), Quartz (SiO2), Calcite (CaCO3), and Ettringite (AFt) (Figure 27. XRD pattern of each CPB material (Al: Alite, Qz: Quartz, Clt: Calcite, AFt: Ettringite). A semi-quantitative analysis of phase intensities (Figure 28) showed that the HT SNP had significantly higher intensities for Alite (49%), Quartz (56%), Calcite (58%), and Ettringite (24%) compared to the control CPB mixture. The high intensity of Alite in HT mixtures contributes to early strength development through the generation of amorphous Calcium-Silicate-Hydrate (CSH) [65]. This is supported by the prominent amorphous hump in the XRD pattern with 2-theta ranging from 15 to 35° for the HT sample (Figure 29), indicating greater pozzolanic reactivity.

Figure 27.

XRD patterns of the CPB materials (Al: Alite, Qz: Quartz, Clt: Calcite, AFt: Ettringite). Enlarged views are provided for clearer phase identification: (A) 2θ = 28–40°, (B) 2θ = 42–70°.

Figure 28.

Relative intensity for each phase in the XRD pattern of control (CTRL), untreated (UT), heat-treated (HT), mechanically treated (MT) SNP CPB.

Figure 29.

Enlarged XRD figures from 14 to 35° two-theta displaying amorphous hump differences in each CPB material.

Quartz typically acts as an inert filler [66,67], enhancing strength through improved packing density and a nucleation effect [68,69]. Meanwhile, Calcite is generated through carbonation in cement blends. It aids in forming hydration products and refining the pore structure, thereby contributing to long-term paste strength [65]. However, it is not as strong as Alite. The calcite intensity of HT CPB was twice that of the other CPB mixtures, which clearly demonstrated its superior paste strength. Ettringite (AFt) typically forms during the early stages of cement hydration when aluminates react with sulfate. However, excessive or delayed generation of ettringite may cause a reduction in strength due to microcracking, leading to lower paste strength in the long-term curing age [70,71,72]. The AFt increase in HT CPB (9–24% higher than other CPB materials) was not associated with strength loss (Figure 26), as the intensity had a low value, which was approximately similar to that of other CPB materials (Figure 28).

4. Conclusions

This study confirms that activated Saudi Natural Pozzolan (SNP), prepared using heat-treated (HT) and mechanical-treated (MT) approaches, can enhance the strength performance of Cemented Paste Backfill (CPB).

- Evaluations of Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS) indicated that the HT scenario was higher than that of other materials with a 5% cement replacement dosage.

- Indirect Tensile Strength (ITS/BTS) indicated that HT (5%) has the second-highest tensile strength, after the control samples.

- Elastic modulus (E) at 28 curing days indicated that MT (5%) and HT (5%) were stiffer than UT and CTRL CPB.

- Microstructural analysis through XRD has demonstrated that the high strength of the HT SNP paste is attributed to the high intensities of Alite, Quartz, and Calcite, along with a suitable amount of Ettringite (AFt). Another support comes from a high amorphous hump in the HT diffractogram.

This study focuses on the mechanical properties of treated SNP; however, an economical and sustainable analysis, as well as a long-term investigation using a high dosage of pozzolan, including other possible scenarios, would be worthwhile topics for future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.T.; methodology, A.A.T.; software, A.A.T.; validation, A.A.T., H.M.A., and H.A.M.A.; formal analysis, A.A.T.; investigation, A.A.T.; resources, A.A.T. and H.M.A.; data curation, A.A.T., H.M.A., and H.A.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.T.; writing—review and editing, A.A.T., H.M.A., and H.A.M.A.; visualization, A.A.T.; supervision, H.M.A., and H.A.M.A.; project administration, H.M.A.; funding acquisition, H.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by the KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Maaden Barrick Copper Company for providing the copper tailings and mining-process water used in this study. Their cooperation and material support were essential for the experimental work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SNP | Saudi Natural Pozzolan |

| CTRL | Control mixes |

| HT | Heat-treated SNP |

| MT | Mechanical Treated SNP |

| UT | Untreated SNP |

| CPB | Cemented Paste Backfill |

References

- Obenaus-Emler, R.; Falah, M.; Illikainen, M. Assessment of mine tailings as precursors for alkali-activated materials for on-site applications. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 246, 118470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson-Edwards, K.A.; Kemp, D.; Torres-Cruz, L.A.; Macklin, M.G.; Brewer, P.A.; Owen, J.R.; Franks, D.M.; Marquis, E.; Thomas, C.J. Tailings storage facilities, failures and disaster risk. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayebi-Khorami, M.; Edraki, M.; Corder, G.; Golev, A. Re-Thinking Mining Waste through an Integrative Approach Led by Circular Economy Aspirations. Minerals 2019, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, Z.; Chen, Z. Environmental management in North American mining sector. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossoff, D.; Dubbin, W.; Alfredsson, M.; Edwards, S.; Macklin, M.; Hudson-Edwards, K. Mine Tailings Dams: Characteristics, Failure, Environmental Impacts, and Remediation. Appl. Geochem. 2014, 51, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Generalized Solution for Mining Backfill Design. Int. J. Geomech. 2014, 14, 04014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.J. Lessons from Tailings Dam Failures—Where to Go from Here? Minerals 2021, 11, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercikdi, B.; Külekci, G.; Yılmaz, T. Utilization of granulated marble wastes and waste bricks as mineral admixture in cemented paste backfill of sulphide-rich tailings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, M.A. Investigating the basic properties of basalt fiber reinforced cemented paste backfill as a sustainable material for mine backfilling. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Xia, K.; Qiao, L. Dynamic tests of cemented paste backfill: Effects of strain rate, curing time, and cement content on compressive strength. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 5165–5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Fall, M. Sulphate effect on the early age strength and self-desiccation of cemented paste backfill. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, D.; Mbonimpa, M.; Yahia, A.; Belem, T. Assessment of rheological parameters of high density cemented paste backfill mixtures incorporating superplasticizers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuylu, S. Effect of different particle size distribution of zeolite on the strength of cemented paste backfill. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiguzel Tuylu, A.N.; Tuylu, S.; Adiguzel, D.; Namli, E.; Gungoren, C.; Demir, I. Optimizing Strength Prediction for Cemented Paste Backfills with Various Fly Ash Substitution: Computational Approach with Machine Learning Algorithms. Minerals 2025, 15, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, C.; Singh, P.; Behera, S.; Mishra, K.; Kumar, D.; Buragohain, J.; Mandal, P. Optimisation of binder alternative for cemented paste fill in underground metal mines. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.; Deb, D.; Sreenivas, T. Variability in rheology of cemented paste backfill with hydration age, binder and superplasticizer dosages. Adv. Powder Technol. 2018, 29, 2211–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Hefni, M.A.; Ahmed, H.A.M.; Saleem, H.A. Cement Kiln Dust (CKD) as a Partial Substitute for Cement in Pozzolanic Concrete Blocks. Buildings 2023, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bakri, A.Y.; Ahmed, H.M.; Hefni, M.A. Cement Kiln Dust (CKD): Potential Beneficial Applications and Eco-Sustainable Solutions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Santos, R.L.; Pereira, J.; Rocha, P.; Horta, R.B.; Colaço, R. Alternative Clinker Technologies for Reducing Carbon Emissions in Cement Industry: A Critical Review. Materials 2022, 15, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Ling, T.-C.; Mo, K.H.; Tian, W. Enhancement of high temperature performance of cement blocks via CO2 curing. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 827–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeloudis, C.; Zervaki, M.; Sideris, K.; Juenger, M.; Alderete, N.; Kamali-Bernard, S.; Villagrán, Y.; Snellings, R. Natural Pozzolans. In Properties of Fresh and Hardened Concrete Containing Supplementary Cementitious Materials: State-of-the-Art Report of the RILEM Technical Committee 238-SCM, Working Group 4; RILEM State-of-the-Art Reports; De Belie, N., Soutsos, M., Gruyaert, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 181–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, C.; Ahmad, W.; Usanova, K.; Karelina, M.; Mohamed, A.; Khallaf, R. Fly Ash Application as Supplementary Cementitious Material: A Review. Materials 2022, 15, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scrivener, K.; Martirena, F.; Bishnoi, S.; Maity, S. Calcined clay limestone cements (LC3). Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 114, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H. Recent progress of utilization of activated kaolinitic clay in cementitious construction materials. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 211, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Khan, K. Mechanical Performance of High-Strength Sustainable Concrete under Fire Incorporating Locally Available Volcanic Ash in Central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. Materials 2021, 14, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, K.; Jackson, M.D.; Mancio, M.; Meral, C.; Emwas, A.-H.; Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. High-volume natural volcanic pozzolan and limestone powder as partial replacements for portland cement in self-compacting and sustainable concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 45, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, D.T.; Robinson, J.E.; Stelten, M.E.; Champion, D.E.; Dietterich, H.R.; Sisson, T.W.; Zahran, H.; Hassan, K.; Shawali, J. Geologic Map of the Northern Harrat Rahat Volcanic Field, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2019.

- Ercikdi, B.; Cihangir, F.; Kesimal, A.; Deveci, H.; Alp, Ì. Effect of natural pozzolans as mineral admixture on the performance of cemented-paste backfill of sulphide-rich tailings. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senhadji, Y.; Escadeillas, G.; Mouli, M.; Khelafi, H. Influence of natural pozzolan, silica fume and limestone fine on strength, acid resistance and microstructure of mortar. Powder Technol. 2014, 254, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roobol, M.J.; Simsim, M.; Tayeb, O.; Abdul-Hafaz, K. Basalt as an Industrial Rock-1 Al-Madinah Area: Quarry Sites for Al-Madinah Al-Mukarramah; BRGM: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 1998.

- Roobol, M.J.; Simsim, M.; Tayeb, O.; Abdul-Hafaz, K. Basalt as an Industrial Rock-2 Central Harrat Rahat: Quarry Sites for Jeddah and Makkah Al-Mukarramah; BRGM: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 1998.

- Roobol, M.J.; Simsim, M.; Tayeb, O.; Abdul-Hafaz, K. Basalt as an Industrial Rock-3 Harrat Kishb: Quarry Sites for At’ Taif, Ar Riyadh and Ad Dammam; BRGM: Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 1998.

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N.; Saleem, M.U.; Qureshi, H.J.; Al-Faiad, M.A.; Qadir, M.G. Effect of Fineness of Basaltic Volcanic Ash on Pozzolanic Reactivity, ASR Expansion and Drying Shrinkage of Blended Cement Mortars. Materials 2019, 12, 2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Amin, M.N.; Usman, M.; Imran, M.; Al-Faiad, M.A.; Shalabi, F.I. Effect of Fineness and Heat Treatment on the Pozzolanic Activity of Natural Volcanic Ash for Its Utilization as Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Crystals 2022, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, H.; Bascetin, A. The study of strength behaviour of zeolite in cemented paste backfill. Geomech. Eng. 2022, 29, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, M.A. The potential use of pumice in mine backfill. Exp. Results 2020, 1, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yowa, G.G.; Sivakugan, N.; Tuladhar, R.; Arpa, G. Strength and Rheology of Cemented Pastefill Using Waste Pitchstone Fines and Common Pozzolans Compared to Using Portland Cement. Int. J. Geosynth. Ground Eng. 2022, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Li, T.; Liang, B. Preparation of a New Type of Cemented Paste Backfill with an Alkali-Activated Silica Fume and Slag Composite Binder. Materials 2020, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Dong, T.; Cui, Z. Effects of composite alkaline activator on mechanical properties and hydration mechanism of cemented paste backfill with cement kiln dust. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, H.; Guo, N.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, Y. Mechanical and Environmental Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill Prepared with Bayer Red Mud as an Alkali-Activator Substitute. Materials 2025, 18, 4712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Amoudi, O.S.B.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, S.; Maslehuddin, M. Durability performance of concrete containing Saudi natural pozzolans as supplementary cementitious material. Adv. Concr. Constr. 2019, 8, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, G.; Alhozaimy, A.; Al-Negheimish, A.; Abdalla Alawad, O. Characterization of scoria rock from Arabian lava fields as natural pozzolan for use in concrete. Eur. J. Environ. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moufti, M.R.; Sabtan, A.A.; El-Mahdy, O.R.; Shehata, W.M. Assessment of the industrial utilization of scoria materials in central Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. Eng. Geol. 2000, 57, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surour, A.; Moufti, M.R.; Nassief, M.O.; Saeda, Y. Chemical characteristics of black scoria and their influence on economic use as industrial rock: A case study from Harrat Rahat, Saudi Arabia. ISESCO J. Sci. Tech. 2017, 13, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM-C311; Standard Test Methods for Sampling and Testing Fly Ash or Natural Pozzolans for Use in Portland-Cement Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39/C39M; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3967; Standard Test Method for Splitting Tensile Strength of Intact Rock Core Specimens with Flat Loading Platens. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C642; Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zoz, H.; Jaramillo, D.; Tian, Z.; Trindade, B.; Ren, H.; Chimal-V, O.; de la Torre, S.D. High Performance cements and advanced Ordinary Portland cement manufacturing by HEM-Refinement and activation. ZKG Int. 2004, 57, 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño-Cardoza, T.; Linsel, S.; Alujas-Diaz, A.; Orozco-Morales, R.; Martirena-Hernández, J.F. Influence of very fine fraction of mixed recycled aggregates on the mechanical properties and durability of mortars and concretes. Rev. Fac. Ing. Univ. Antioq. 2016, 81, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korouzhdeh, T.; Eskandari-Naddaf, H.; Kazemi, R. The ITZ microstructure, thickness, porosity and its relation with compressive and flexural strength of cement mortar; influence of cement fineness and water/cement ratio. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Ying, K.; Hong, Y.; Xu, Q. Effect of different particle sizes of nano-SiO2 on the properties and microstructure of cement paste. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2020, 9, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korouzhdeh, T.; Eskandari-Naddaf, H. Evolution of different microstructure and influence on the characterization of pore structure and mechanical properties of cement mortar exposed to freezing-thawing: The role of cement fineness. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 140, 106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, V.D.; de Abreu, R.F.; Alexandre, J.; Xavier, G.d.C.; Marvila, M.T.; de Azevedo, A.R.G. Pozzolanic Potential of Calcined Clays at Medium Temperature as Supplementary Cementitious Material. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmatka, S.; Kerkhoff, B.; Panarese, W. Design and Control of Concrete Mixtures; Portland Cement Association (PCA): Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, H.H.; Najm, H.; Suksawang, N. Effect of pozzolanic materials and curing methods on the elastic modulus of HPC. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyasigorji, F.; Farajiani, F.; Hajipour Manjili, M.; Lin, Q.; Elyasigorji, S.; Farhangi, V.; Tabatabai, H. Comprehensive Review of Direct and Indirect Pozzolanic Reactivity Testing Methods. Buildings 2023, 13, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercikdi, B.; Yılmaz, T.; Külekci, G. Strength and ultrasonic properties of cemented paste backfill. Ultrasonics 2014, 54, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkadir, S.B.; Chen, Q.; Yilmaz, E.; Wang, D. Comparative and Meta-Analysis Evaluation of Non-Destructive Testing Methods for Strength Assessment of Cemented Paste Backfill: Implications for Sustainable Pavement and Concrete Materials. Materials 2025, 18, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liqiang, M.; Ahmad, Q.A.; Islam, M.M.; Khan, N.; Mangi, H.N.; Golsanami, N. Rock physics-based approach to assess the effectiveness of cement-based backfill materials in coal mining. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0333364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sainsbury, B.L.; Harty, D.; Felipe, F.; Ruest, M.; McLoughney, D.; Sainsbury, D. Characterisation of the geomechanical properties of cemented paste backfill for design. In Proceedings of the Paste 2024: 26th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings, Melbourne, Australia, 16–18 April 2024; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.-X.; Song, W.-D.; Tan, Y.-Y. Study on Microstructural Evolution and Strength Growth and Fracture Mechanism of Cemented Paste Backfill. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2016, 8792817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Liu, Z.; Min, C.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W. Compressive strength prediction of cemented backfill containing phosphate tailings using extreme gradient boosting optimized by whale optimization algorithm. Materials 2022, 16, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Peng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, G.; Tang, G.; Pan, A. Experimental Study on Direct Tensile Properties of Cemented Paste Backfill. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 864264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Li, W.; Shen, X. Study on the physical and chemical properties of Portland cement with THEED. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 213, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.H.A.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Razak, R.A.; Yahya, Z.; Salleh, M.A.A.M.; Chaiprapa, J.; Rojviriya, C.; Vizureanu, P.; Sandu, A.V.; Tahir, M.F.; et al. Mechanical Performance, Microstructure, and Porosity Evolution of Fly Ash Geopolymer after Ten Years of Curing Age. Materials 2023, 16, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.-Y. A Hydration Model to Evaluate the Properties of Cement–Quartz Powder Hybrid Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, L.R.C.; Tavares, J.F.T., Jr.; Costa, L.M.; da Silva Bezerra, A.C.; Cetlin, P.R.; Aguilar, M.T.P. Influence of quartz powder and silica fume on the performance of Portland cement. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.-S.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, G.-Y. Effects of Quartz Powder on the Microstructure and Key Properties of Cement Paste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, I.; Ainsworth, P.; Salvoldi, B.; Cano, R.; López, D. Reduction of strength losses in paste backfill with sludge cake. In Proceedings of the Paste 2023: 25th International Conference on Paste, Thickened and Filtered Tailings, Banff, AB, Canada, 1–3 May 2023; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, M.; Fall, M. Combined influence of sulphate and temperature on the saturated hydraulic conductivity of hardened cemented paste backfill. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 38, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, U.G.; Cinku, K.; Yilmaz, E. Characterization of Strength and Quality of Cemented Mine Backfill Made up of Lead-Zinc Processing Tailings. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 740116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).