Featured Application

Phase angle measured using a simple bioelectrical impedance device may serve as a practical screening indicator of exercise tolerance in healthy adults. This approach offers a rapid, non-invasive and economical tool for assessing aerobic capacity in fitness evaluations, preventive health screening, and field-based settings where cardiopulmonary exercise testing is impractical.

Abstract

Regular assessment of aerobic capacity is important in sports medicine and preventive health; however, cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) is often impractical in field or clinical settings. Phase angle (PhA), derived from bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), has been proposed as a practical indicator of cellular health and membrane integrity; however, its relevance to aerobic capacity relative to skeletal muscle mass percentage (SMM%) in healthy young adults remains unclear. This cross-sectional study investigated the independent associations of PhA and SMM% with peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and oxygen uptake at the anaerobic threshold (VO2AT). Forty-one adults underwent same-day BIA and CPX using a cycle ergometer. VO2peak was obtained from 37 participants who achieved maximal effort, while VO2AT was identified in all. In multiple regression analyses adjusted for sex, PhA was independently associated with both VO2peak and VO2AT, whereas SMM% showed no independent association. These findings indicate that PhA may serve as a stronger determinant of aerobic capacity than SMM% in healthy young adults and highlight its potential utility in settings such as routine health check-ups or preliminary screening of aerobic capacity when CPX is impractical.

1. Introduction

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) provides an integrated assessment of aerobic capacity and remains the gold standard for evaluating exercise tolerance. Key CPX-derived parameters such as peak oxygen uptake (VO2peak) and oxygen uptake at the anaerobic threshold (VO2AT) are widely used to assess functional status, guide exercise prescription, and predict clinical outcomes [1]. Strong evidence links higher exercise tolerance to improved long-term survival [1]. According to Wasserman’s gears model [2], VO2 reflects the coordinated function of the cardiac, pulmonary, and skeletal muscle systems, with skeletal muscle oxygen utilization serving as a major determinant of VO2 alongside cardiac output and pulmonary diffusion capacity [3].

Skeletal muscle oxygen utilization depends on both muscle mass and muscle quality [4,5,6,7]. Muscle mass contributes to the overall oxygen consumption capacity, whereas functional characteristics, such as contractile efficiency and metabolic responsiveness, influence aerobic performance. Because these attributes adapt differently to training, distinguishing the relative importance of muscle quantity and qualitative muscle properties is important for understanding inter-individual differences in aerobic capacity.

In clinical practice, skeletal muscle is commonly assessed through modalities quantifying muscle mass, such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry and bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) [8]. In contrast, widely applicable indicators of functional muscle properties remain limited. Phase angle (PhA) derived from BIA, has attracted growing interest because it reflects the relationship between resistance and reactance and may capture general electrical properties of tissues [9,10,11]. Recent studies in diverse populations, including older adults, adolescents, athletes, and individuals with obesity or heart failure, have demonstrated positive associations between PhA and VO2peak or related indicators of aerobic capacity [12,13,14,15,16]. These findings suggest that PhA may reflect aspects of muscle or whole-body function that are relevant to aerobic performance. However, the relative contributions of PhA and skeletal muscle mass percentage (SMM%) to aerobic capacity in healthy young adults—who represent an important physiological reference group—remain unclear. Few studies have evaluated PhA and SMM% within the same multivariate framework; therefore, whether PhA provides information beyond that explained by muscle quantity remains unclear. Addressing this gap would help refine our understanding of the physiological factors underlying aerobic fitness and the potential role of BIA-derived indices in exercise assessment.

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate whether PhA is independently associated with VO2peak in healthy young adults after accounting for SMM%. A secondary aim was to evaluate the associations of PhA and SMM% with VO2AT. From a theoretical perspective, comparing these indices may help elucidate the relative influence of muscle quantity and BIA-derived electrical properties on aerobic capacity. From a practical perspective, determining whether PhA provides meaningful information could support its use as a screening indicator in situations where CPX is impractical.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Institute of Science Tokyo Hospital. Participants were recruited during laboratory-based practical sessions between April 2023 and March 2024. Healthy young adults (approximately 20–29 years) were eligible if they self-reported being in good health and capable of independently performing daily activities without known physical limitations. Individuals with known cardiovascular, respiratory, or metabolic disease; musculoskeletal disorders restricting exercise; pregnancy or possible pregnancy; regular use of medications influencing exercise responses (e.g., β-blockers, digitalis); or acute illness within 48 h before testing were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the Institute of Science Tokyo Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. I2024-108) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In accordance with institutional guidelines for non-invasive observational research, the need for written informed consent was waived under the institutional opt-out policy. Study information, including the purpose, procedures, and right to decline participation, was publicly posted on the hospital website and on-site bulletin boards, and participants could withdraw at any time.

2.2. Body Composition Measurement

Body composition variables, specifically PhA and SMM%, were measured using a single multi-frequency BIA device (ACCUNIQ BC380, Toyo Medic Inc., Tokyo, Japan), equipped with an 8-point tactile electrode system. Measurements were taken around midday to minimize circadian variation in hydration status. Participants stood barefoot on foot electrodes while grasping hand electrodes, maintaining a stable posture.

To minimize transient effects of food and fluid intake, assessments were performed at least 3 h after the last meal or beverage. PhA was calculated from reactance (Xc) and resistance (R) at 50 kHz using the following formula:

SMM% was recorded directly as displayed by the analyzer.

PhA (°) = arctan (Xc/R) × 180/π

2.3. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing

Cardiorespiratory variables were measured using a breath-by-breath gas analyzer (Aeromonitor AE-300S, Minato Medical Science Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) during incremental exercise on a cycle ergometer (Well Bike BE-260, Fukuda Denshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Participants completed a 3-min warm-up at 20 W, followed by workload increments of 15 W/min for men and 10 W/min for women. These sex-specific ramp rates were selected to achieve a target total test duration of 8–12 min, consistent with CPX guidelines, and to account for sex-related differences in body size and aerobic capacity. Exhaled gas measurements were averaged every 10 s. VO2peak was defined as the highest 30-s averaged VO2 value obtained during the final stage of exercise. All exercise tests were terminated upon volitional exhaustion. Maximal effort was objectively verified by a respiratory exchange ratio (RER) ≥ 1.10. Participants who did not reach RER ≥ 1.10 were excluded from VO2peak analyses but retained for VO2AT analyses. VO2AT was determined independently by two experienced assessors using the V-slope method [17] combined with inspection of ventilatory equivalents (VE/VO2 and VE/VCO2). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus following a joint re-evaluation. To ensure validity, BIA and CPX were performed on the same day, with BIA consistently performed prior to CPX, to prevent post-exercise fluid shifts, thermal changes, or dehydration influencing impedance values.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The primary and secondary outcomes were VO2peak and VO2AT, respectively. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Pearson correlation and simple linear regression analyses were used to examine associations of PhA and SMM% with VO2 variables. Multiple linear regression analyses were then performed with PhA, SMM%, and sex (men = 1, women = 0) as predictors. Age and body mass index were excluded because they exhibited limited variability within this study cohort and were not central to the study aims.

Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF), with VIF < 5 considered acceptable. Regression coefficients were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To address the risk of type I error from multiple testing, the Holm–Bonferroni correction was applied to the five primary Pearson correlation analyses; all remained significant after adjustment. Regression analyses and interaction tests were considered exploratory, and p-values for these models were not adjusted for multiplicity.

The significance level was set at α = 0.05 (two-tailed), and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using EZR (version 1.63; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Participants

A total of 41 individuals were screened, all of whom met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. The cohort comprised 27 men (66%) and 14 women (34%), with a mean age of 23.3 ± 1.7 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 20.8 ± 2.5 kg/m2. Baseline body composition measurements indicated a mean PhA of 6.9 ± 1.3° and a mean SMM% of 33.5 ± 3.9%.

VO2peak was successfully measured in 37 of the 41 participants, yielding a mean value of 1669 ± 619 mL·min−1. Four participants voluntarily terminated the test before achieving maximal effort and were therefore excluded from VO2peak analysis. However, the secondary outcome of VO2AT was successfully determined in all 41 participants, with a mean value of 1195 ± 368 mL·min−1.

Participant characteristics for the entire cohort (n = 41) and stratified by sex are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, men demonstrated significantly higher PhA (7.6 ± 0.9° vs. 5.6 ± 0.9°), SMM% (35.4 ± 2.8% vs. 29.9 ± 3.0%), VO2peak (1967 ± 481 vs. 964 ± 149 mL·min−1), and VO2AT (1372 ± 324 vs. 855 ± 129 mL·min−1) compared with women (all p < 0.001), whereas no significant differences were observed in age or BMI. To examine whether the exclusion of non-maximal performers introduced selection bias, baseline characteristics were compared between the 37 participants who achieved VO2peak and the 4 who did not; no meaningful differences were observed in age, BMI, PhA, or SMM% (all p > 0.10).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants.

3.2. Correlation and Regression Analyses

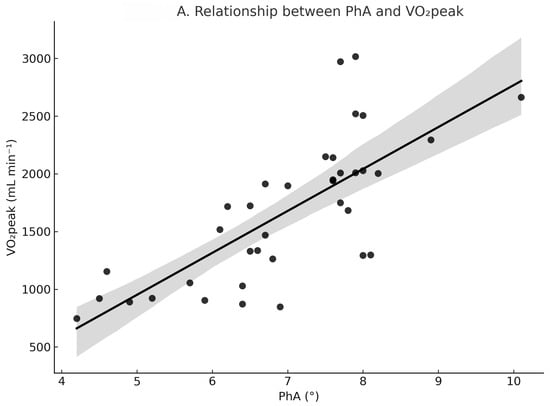

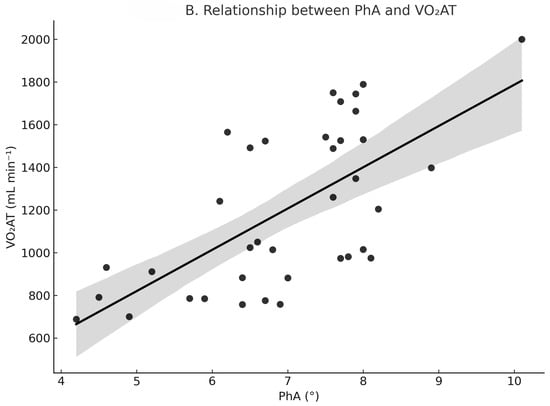

Pearson correlation coefficients are presented in Table 2, and the associations between PhA and VO2 variables are illustrated in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, participants with higher PhA generally exhibited significantly higher VO2peak and VO2AT values. VO2peak was strongly and positively correlated with PhA (r = 0.75, 95% CI: 0.55–0.87, p < 0.001; n = 37). The correlation between VO2peak and SMM% was also positive and significant but of moderate strength (r = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.10–0.65, p = 0.012; n = 37). VO2AT showed a strong positive correlation with PhA (r = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.44–0.80, p < 0.001; n = 41) and a moderate positive correlation with SMM% (r = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.21–0.69, p = 0.001; n = 41). Additionally, PhA was moderately correlated with SMM% (r = 0.42, 95% CI = 0.13–0.64, p = 0.006; n = 41).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between PhA, SMM%, and oxygen uptake variables.

Figure 1.

Relationship between PhA and oxygen uptake variables. (A) PhA vs. VO2peak (r = 0.75, p < 0.001, n = 37). (B) PhA vs. VO2AT (r = 0.66, p < 0.001, n = 41). Solid lines indicate linear regression. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Circles (●) represent individual data points.

In simple linear regression analyses, PhA alone explained 56% of the variance in VO2peak (R2 = 0.56, β = 0.75), whereas SMM% explained only 17% (R2 = 0.17). As summarized in Table 3, the multiple linear regression model for the primary outcome, VO2peak (n = 37), was significant and explained 63% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.63). Within this model, PhA (β = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.12–0.69, p = 0.009) and sex (β = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.14–0.88, p = 0.008) emerged as significant independent predictors of VO2peak, whereas SMM% was not (β = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.36–0.20, p = 0.555). The VIFs were low (1.79–3.14), indicating that multicollinearity did not significantly affect the model.

Table 3.

Multiple regression analysis of VO2peak (n = 37).

In the secondary analysis for VO2AT (n = 41), summarized in Table 4, the overall model explained 48% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.48). In this model, PhA remained a significant independent predictor of VO2AT (β = 0.38, 95% CI: 0.03–0.73, p = 0.032), whereas SMM% (β = −0.10, p = 0.483) and sex (β = 0.21, p = 0.143) were not. In the supplementary analysis of relative VO2peak (mL·min−1·kg−1), the association with PhA was not significant (β = 0.23, p = 0.24). An exploratory inclusion of a sex × PhA interaction term in the VO2peak regression model revealed no significant interaction effect (p = 0.10), indicating that the association between PhA and VO2peak did not differ substantially between men and women in this sample.

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis of VO2AT (n = 41).

4. Discussion

4.1. PhA and VO2peak

In this cross-sectional analysis among healthy adults aged 22–30 years, the primary finding was that PhA was independently associated with VO2peak after adjusting for SMM% and sex, whereas SMM% was not a significant independent predictor. SMM% correlated positively with VO2peak in the univariate analysis, consistent with previous studies reporting established skeletal muscle mass as a significant determinant of aerobic capacity; however, this association diminished when PhA was included in the multivariate model, as reported both in physiological studies using high-precision MRI [18] and in clinical populations such as those with chronic heart failure [19]. Therefore, in this relatively homogeneous young cohort, qualitative characteristics of muscle captured by PhA may play a greater role than the absolute amount of muscle mass in determining maximal aerobic performance. This non-significant finding for SMM% should not be interpreted as indicating physiological irrelevance. Rather, it likely reflects several factors: (1) limited between-subject variability in muscle mass within this healthy cohort; (2) shared variance between PhA and SMM%, with PhA accounting for a larger proportion of the variance in VO2peak; and (3) reduced precision of SMM% measured by BIA compared with gold-standard methods such as DXA or MRI. Together, these factors may have attenuated the contribution of SMM% in the multivariate model. Physiologically, PhA represents an impedance-derived index reflecting a balance between resistance and reactance, and it is associated with cellular integrity, membrane capacitance, and fluid distribution. These properties influence muscle function and may explain the observed associations with aerobic performance. However, because direct assessments of muscle histology or mitochondrial function were not performed, mechanistic interpretations remain speculative.

4.2. PhA and VO2AT

The association between PhA and VO2AT was also significant, although the effect size was weaker than that observed for VO2peak. This attenuation is physiologically plausible. VO2AT reflects a submaximal physiological transition point influenced by multiple factors, including ventilatory control, peripheral metabolic adjustments, and balance between aerobic and anaerobic pathways. These factors introduce greater inter-individual variability and may reduce the relative contribution of muscle-related properties, which PhA is believed to capture. Unlike VO2peak, which is more directly linked to maximal oxygen utilization capacity of skeletal muscle, VO2AT reflects a broader integrative response in which muscle-related factors may play a less dominant role.

4.3. PhA and Relative VO2peak

The lack of a significant association between PhA and relative VO2peak likely reflects the limited variability in body composition and aerobic fitness within this young adult cohort. Normalization of VO2peak to body mass reduces the influence of absolute physiological differences and may obscure relationships with impedance-derived measures such as PhA, particularly in samples with narrow BMI ranges. Additionally, the modest sample size and interdependence between muscle mass and muscle quality could further reduce detectable effect sizes. In populations with greater variations in muscle mass and metabolic health such as in individuals with sarcopenia, frailty, or chronic disease, PhA may more sensitively capture qualitative characteristics of muscle and may relate more strongly to relative VO2peak. Therefore, the absence of an association in our cohort should not be generalized beyond populations with similar demographic and physiological characteristics.

4.4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

PhA demonstrated a stronger independent association with aerobic capacity than SMM% in this cohort of healthy young adults. These findings suggest that PhA may have practical value as a rapid, non-invasive indicator of aerobic fitness in settings where CPX is not feasible. In high-throughput environments such as workplace or university health examinations, community screenings, or pre-participation evaluations for sports programs, a brief BIA measurement could help identify individuals with potentially lower aerobic capacity, who may then be prioritized for more detailed physiological testing or targeted exercise guidance, thereby enhancing the efficiency of resource allocation in preventive and sports medicine. Beyond screening, PhA may also have utility as a monitoring marker for physiological adaptations. Short-term physiological perturbations, such as a 2-week detraining period, have been shown to decrease PhA in parallel with reductions in muscle function, suggesting that PhA is sensitive to changes in neuromuscular status [20]. However, no study to date has examined whether longitudinal changes in PhA correspond to changes in VO2peak or VO2AT, which are primary outcomes of aerobic training. Establishing this relationship is essential before PhA can be adopted as a dynamic marker for monitoring aerobic fitness. To advance PhA toward clinical utility, several research steps are needed. First, longitudinal training and detraining studies should evaluate whether intervention-induced changes in PhA track with changes in VO2peak or other CPX-derived indices. Such evidence would clarify whether PhA can serve merely as a cross-sectional correlate or also as a responsive biomarker of aerobic adaptation. Second, large-scale cohort studies are required to establish age-, sex-, and population-specific reference values of PhA to aid interpretation in diverse groups. Third, inter-device and inter-protocol standardization across BIA systems is necessary to ensure reproducibility and facilitate broader implementation in clinical and field settings. Collectively, these steps will determine whether PhA can evolve from a convenient correlational measure into a validated, widely applicable tool for screening and monitoring aerobic capacity in clinical and community health environments.

4.5. Limitations

Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. It remains unclear whether higher PhA contributes to improved aerobic capacity, whether individuals with higher aerobic capacity develop higher PhA, or whether both are influenced by unmeasured factors such as habitual physical activity, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Because training status was not assessed, residual confounding is possible and may have influenced the observed associations. Second, the sample comprised healthy young adults with a relatively homogeneous age and body composition profile. Although this reduces between-subject variability and enhances internal consistency, it limits the generalizability of our findings to older adults or clinical populations with greater variability in muscle mass and qualitative muscle characteristics. The notably low absolute VO2peak values in the female subgroup likely reflect both limited habitual physical activity and the use of cycle ergometry, which typically yields lower values than treadmill testing. While this does not affect the internal validity of our association analyses, it constrains broader interpretation of the absolute fitness levels reported. Third, only 37 of the 41 participants achieved maximal effort based on an RER ≥ 1.10. Participants who did not meet this criterion were excluded from VO2peak analyses. As their baseline characteristics did not differ substantially from the included participants, selection bias would have been minimal. Nonetheless, excluding these cases reduced the statistical power for VO2peak and may have contributed to the non-significant association between PhA and relative VO2peak. Fourth, both PhA and SMM% were assessed using a single BIA device. Although BIA provides practical and reproducible estimates in healthy populations, it is less precise than gold-standard techniques such as DXA or MRI. Measurement imprecision may have attenuated the true association between muscle mass and aerobic capacity in the multivariate model. Moreover, because PhA and SMM% were derived from the same device, shared measurement bias cannot be fully excluded, although VIF values indicated no substantive multicollinearity within the regression models. Finally, VO2AT was identified by two trained assessors using standard gas-exchange criteria, but formal inter-rater reliability indices (e.g., intra-class correlation coefficients) were not calculated. Although consensus was reached for all determinations, the potential for subjective variability in AT identification should be acknowledged.

5. Conclusions

In this cohort of healthy young adults, PhA was independently associated with VO2peak after adjusting for SMM% and sex, whereas SMM% was not a significant independent predictor. This finding suggests that qualitative characteristics of muscle may provide additional information beyond muscle quantity when evaluating maximal aerobic capacity in this population. PhA was correlated with VO2AT, although the association was only modest, likely reflecting the greater physiological variability and multifactorial determinants of submaximal exercise responses. Given its simplicity, low cost, and accessibility, PhA shows potential as a practical screening tool in settings where CPX is not feasible. However, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal inference, and the findings are limited to a relatively homogeneous sample. To support broader application, future research should validate these associations in larger and more diverse populations, establish normative reference values across demographic groups, and clarify whether changes in PhA correspond to changes in aerobic capacity in longitudinal or interventional studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T. and T.Y.; methodology, Y.T.; software, Y.T.; validation, Y.T., M.H., and T.S.; formal analysis, Y.T.; investigation, Y.T.; resources, M.H.; data curation, M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T.; writing—review and editing, T.S. and T.Y.; visualization, Y.T.; supervision, T.Y.; project administration, T.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Institute of Science Tokyo Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. I2024-108), and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

In accordance with institutional guidelines for non-invasive observational research, the need for written informed consent was waived under the institutional opt-out policy. Study information was publicly disclosed, and participants were allowed to withdraw at any time without prejudice, consistent with Japanese ethical standards for research.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized dataset supporting the findings of this study is publicly available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30314497.v1. The dataset includes all individual-level measurements used in the statistical analyses (excluding any personal identifiers).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (version GPT-5, OpenAI) to assist with English language editing. The authors have reviewed and edited all AI-assisted text and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BIA | Bioelectrical impedance analysis |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CPX | Cardiopulmonary exercise testing |

| PhA | Phase angle |

| SMM% | Skeletal muscle mass percentage |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| VO2 | Oxygen uptake |

| VO2AT | Oxygen uptake at anaerobic threshold |

| VO2peak | Peak oxygen uptake |

References

- Balady, G.J.; Arena, R.; Sietsema, K.; Myers, J.; Coke, L.; Fletcher, G.F.; Forman, D.; Franklin, B.; Guazzi, M.; Gulati, M.; et al. Clinician’s guide to cardiopulmonary exercise testing in adults: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 122, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, K.; Whipp, B.J.; Koyl, S.N.; Beaver, W.L. Anaerobic threshold and respiratory gas exchange during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1973, 35, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, D.R.; Howley, E.T. Limiting factors for maximum oxygen uptake and determinants of endurance performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calbet, J.A.; Jensen-Urstad, M.; van Hall, G.; Holmberg, H.C.; Rosdahl, H.; Saltin, B. Maximal muscular vascular conductances during whole body upright exercise in humans. J. Physiol. 2004, 558, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, D.C.; Hirai, D.M.; Copp, S.W.; Musch, T.I. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: Implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H1050–H1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodpaster, B.H.; He, J.; Watkins, S.; Kelley, D.E. Skeletal muscle lipid content and insulin resistance: Evidence for a paradox in endurance-trained athletes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001, 86, 5755–5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, M.J.; Gardner, A.W.; Ades, P.A.; Poehlman, E.T. Contribution of body composition and physical activity to age-related decline in peak VO2 in men and women. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1994, 77, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Wang, Z.M.; Ross, R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2000, 89, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa-Silva, M.C.; Barros, A.J. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in clinical practice: A new perspective on its use beyond body composition equations. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2005, 8, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Herpich, C.; Müller-Werdan, U. Role of phase angle in older adults with focus on the geriatric syndromes sarcopenia and frailty. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Zocher, D.; Bosy-Westphal, A.; Szramek, A.; Scheufele, R.; Smoliner, C.; Pirlich, M. Cutoff percentiles of bioelectrical phase angle predict functionality, quality of life, and mortality in patients with cancer. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Streb, A.R.; Hansen, F.; Gabiatti, M.P.; Tozetto, W.R.; Del Duca, G.F. Phase angle associated with different indicators of health-related physical fitness in adults with obesity. Physiol. Behav. 2020, 225, 113104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, C.N.; Campa, F.; Cerullo, G.; D’antona, G.; Giro, R.; Faleiro, J.; Reis, J.F.; Monteiro, C.P.; Valamatos, M.J.; Teixeira, F.J. Bioelectrical impedance vector analysis discriminates aerobic power in futsal players: The role of body composition. Biology 2022, 11, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, Y.; Itoi, A.; Yoshida, T.; Nakagata, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Fujita, H.; Kimura, M.; Miyachi, M. Association of bioelectrical phase angle with aerobic capacity, complex gait ability and total fitness score in older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 150, 111350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Junior, M.C.P.D.; Silva, D.A.S.; Martins, P.C.; Bueno, N.B.; Moura, F.A.; Lima, L.R.A. Aerobic fitness, phase angle, and bioelectrical impedance vector analysis in adolescents living with HIV: A cross-sectional study. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2025, 43, e2024277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onishi, H.; Ogawa, M.; Honda, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Soma, R.; Yoshikawa, R.; Sakai, Y. Phase angle measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis as a predictor of exercise capacity in patients undergoing late-recovery phase cardiac rehabilitation. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2025, zwaf398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaver, W.L.; Wasserman, K.; Whipp, B.J. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 1986, 60, 2020–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanada, K.; Kearns, C.F.; Kojima, K.; Abe, T. Peak oxygen uptake during running and arm cranking normalized to total and regional skeletal muscle mass measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 93, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicoira, M.; Zanolla, L.; Franceschini, L.; Rossi, A.; Golia, G.; Zamboni, M.; Tosoni, P.; Zardini, P. Skeletal muscle mass independently predicts peak oxygen consumption and ventilatory response during exercise in noncachectic patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2001, 37, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, S.P.; Júdice, P.B.; Hetherington-Rauth, M.; Magalhães, J.P.; Correia, I.R.; Lopes, J.M.; Strong, C.; Matos, D.; Sardinha, L.B. The impact of 2 weeks of detraining on phase angle, BIVA patterns, and muscle strength in trained older adults. Exp. Gerontol. 2021, 144, 111175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).