Abstract

This study aimed to compare the effects on post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) of an axial load exercise, the deadlift (DL), and a hip joint-dominant exercise, the hip thrust (HT). Fifteen resistance-trained male rugby players with ≥5 years of experience (age: 22.7 ± 1.6 years; body mass index: 27.2 ± 2.3 kg/m2) participated in this study. They performed two repetitions at 90% of their one-repetition maximum with 8 min of recovery between the HT and the DL exercises. The order of the exercises was randomized, and then a standing broad jump (BJ) was performed. There were significant changes in BJ distance after DL (Δ = 7.1 cm; 95% confidence interval [CI] 4.5–9.7; p < 0.001; d = 0.29 [0.16–0.53]) and after HT (Δ = 5.1 cm; 95% CI 2.1–7.8; p = 0.003; d = 0.23 [0.08–0.43]); no difference was found between protocols. In a two-way repeated-measures model, a main effect of Time was observed (p < 0.001; η2p = 0.707), with no effects for Protocol (p = 0.122; η2p = 0.162) or for the Time × Protocol interaction (p = 0.326; η2p = 0.069). DL and HT elicited significant but small PAPE effects as expressed through BJ outcomes, with no between-protocol differences.

1. Introduction

A significant increase in muscle twitch force expressed in specific motor actions with marked explosive character has been demonstrated after performing maximal or sub-maximal muscle contractions. This physiological phenomenon is widely known as post-activation potentiation (PAP) [1]. However, a relevant change in the conceptualization of this effect has been suggested recently, proposing the term post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) when it is greater than 28 s, and physical, athletic, or sport-specific abilities have been assessed [2]. Thus, following this idea, performing exercises requiring a high level of force production before a particular exercise would lead to an increased speed or nerve impulse conduction and improved contractile mechanism in the subsequent activity [3]. PAPE effects are highly dependent on the recovery time between both actions. The temporal balance between fatigue and potentiating factors will determine if the subsequent contraction will be increased, reduced, or will not be modified, as has been previously observed by Scott & Docherty [4]. These same authors also stated that the physiological post-stimulus response would depend on the occurrence of PAPE and fatigue. Both PAPE and fatigue can increase immediately after the contractile activity and gradually return to pre-stimulus levels [4]. Thus, sports actions with a high degree of power requirements will benefit from this previous activation. Data show that if PAPE is produced, it will increase jumping capacity [5,6], with the vertical jump being the most studied skill [7], even applying an isometric contraction [8,9]. Current evidence also suggests a possible influence of PAPE to improve performance in endurance-trained participants [10]; however, responses in the sprint are mixed; from our laboratory, we have not found significant improvements [11], although other work groups found positive results [12].

On this improvement, neither the physiological mechanisms that underlie this phenomenon nor the most effective way to achieve PAPE is known. The phosphorylation of myosin light chains seems to be related to PAPE, since the sensitivity of actin-myosin interaction with calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is increased [13]. Furthermore, higher excitability of motoneurons due to the amplitude of the Hoffman reflex may also be the cause of this phenomenon [14].

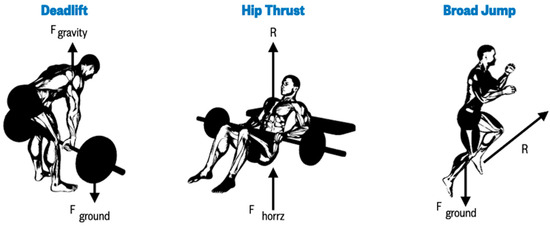

Vertical and horizontal jump capacity are motor actions that often intervene in different sports, and have been used as predictors of power performance in the past [15], since this capacity is involved in actions such as sprinting or change of direction (COD). However, vertical and horizontal jumps do not have the same direction. In this sense, the concept of vector has been proposed, allowing an adequate description of the movement. Consequently, training using force vectors considers load direction and the athlete’s position when executing the movement, thereby increasing the specificity of training. It is proposed, then, that training adaptations can be specific to the direction of movement. Figure 1 shows the application of different force vectors.

Figure 1.

Different force vectors.

Anteroposterior exercises can transfer better to horizontal force production, just as force vectors in axial load exercises transfer higher production of vertical force [16]. Following the principle of training specificity [17], vector analysis becomes important, since it allows identifying the different exercises that transfer optimally to sports performance [18]. This identification also includes the best exercises aiming at eliciting PAPE. It could be suggested, then, that torque and functionality of the movements are determining factors to select the proper exercises and their best order to generate PAPE.

Specifically, horizontal jumps are movements with an anteroposterior-emphasis force vector nature combined with an axial component, requiring vertical displacement to take-off. Therefore, this action is more specific to activities such as COD or sprints. In this sense, the deadlift (DL) exercise is classified as an exercise with an axial-emphasis force vector, while the hip-thrust (HT) is considered an anteroposterior-emphasis force vector movement [18].

To date, few studies have focused on the broad jump (BJ) test to express PAPE in the past; therefore, this study aimed to compare the effects of performing a PAPE protocol on the BJ test using exercises with axial-emphasis force vector predominance, such as the DL, compared to an anteroposterior-emphasis force vector exercise, such as the HT [19,20]. The initial hypothesis is that when the anteroposterior component predominates over the axial one, the HT exercise, presenting more similarities, will obtain more significant PAPE effects on the BJ than an exercise with axial force vector predominance, such as the DL.

2. Materials and Methods

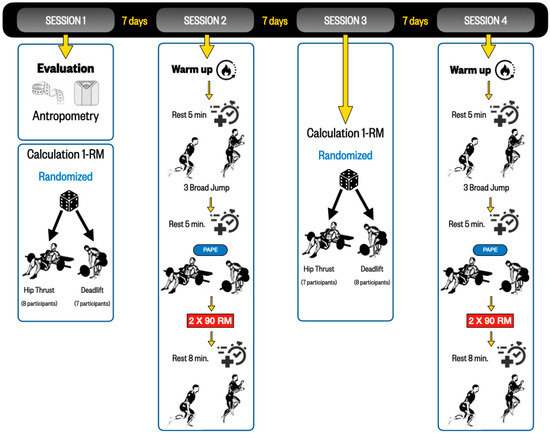

In the present study, a randomized repeated-measures crossover design was implemented to induce PAPE in the standing BJ using the HT and DL exercises. In the first session, anthropometric measurements were taken, and participation was randomized using the website randomizer.org. Additionally, the 1RM in the DL (7 participants) and HT (8 participants) exercises were tested following the protocol established by our group [21]. In the second session, PAPE was induced employing the DL and HT exercises using the 1RM values obtained during the first session. In the third session, the 1RM value of the exercises not tested in the first session was obtained for those individuals not previously assessed. PAPE was induced in the last session, changing the exercise used and the 1RM values obtained in the third session. Figure 2 shows the final methodological design of the study.

Figure 2.

Crossover study design and session timeline for deadlift (DL) and hip thrust (HT) protocols.

No familiarization sessions for the HT or DL exercises or the BJ were carried out since the participants had proven experience of more than five years in the use of these exercises.

2.1. Participants

Fifteen advanced male rugby players aged 18–30 years with ≥5 years of experience in resistance training participated in the study. Participants were informed about the experimental procedures and the possible risks and signed informed consent. Procedures followed the Declaration of Helsinki [WMA] [22] and were approved by the University of Málaga Ethics Committee (CEUMA code: 52-2025-H).

Participants who self-reported the use of doping agents (i.e., anabolic–androgenic steroids) during the last two years, as well as those who were not within the required age range of 18 to 35 years, were excluded from participation. In addition, participants who were suffering or had been treated recently for knee or hip injuries were also excluded. All participants declared themselves to be free of any neuromuscular or musculoskeletal pain. Participants were instructed not to exercise, nor to consume stimulant substances (e.g., coffee) at least 24 h before the assessments.

2.2. Measures

This study examined the effects of PAPE on BJ using the DL and HT exercises. To determine the effects, participants conducted four experimental sessions, with seven days between each visit to the laboratory. In the first session, anthropometric measurements of all of the participants were taken. The one-repetition maximum (1RM) in the DL or the HT was tested, assigning the participants at random, with one exercise per session. In the second and fourth sessions, the PAPE test was performed with a previous DL or HT exercise.

2.2.1. One-Repetition Maximum (1RM) Tests: Hip Thrust (HT) and Deadlift (DL)

The evaluation of the 1RM in the HT and DL exercises was carried out randomly and individually in sessions one and three. In both sessions, all the participants performed a standardized 12 min general warm-up, including joint mobility, activation movements, and dynamic stretching for the lower limb muscles. Between three and four incremental load series were carried out using the Baechle & Earle protocol [23]. Participants were supervised in the use of the correct technique in both exercises, noting the width, foot rotation, and grip that were employed, and maintaining the same stances and distances in sessions two and four. All of the measurements were performed on an elevated platform with an Olympic barbell and competition discs of different weights (Taurus, Buenos Aires, Argentina). A 72 cm barbell grip was used in the DL both in the 1RM evaluation and in the PAPE session. Despite the participants’ familiarity with the DL exercise, verbal instruction was used to encourage the lumbar spine neutral position. The technical aspects in the execution of the DL followed those in Andersen et al. [24], indicating that the movement is carried out with the weight on the platform, considering the end when the hip was extended over 180 degrees (trunk-thigh angle). In the HT, participants began the movement lying, resting their backs on a bench with a 49 cm height (Professional Gym, Buenos Aires, Argentina). Participants used a barbell pad as protection. The bar was placed in the hip crease, between the iliac crests and the anterior superior iliac spine. The knee angle was 90° in the top position, as previously reported [24]. Again, it was encouraged verbally that the thrust would be considered valid once the hip was fully extended. For this, an expert in resistance training supervised the exercise technique throughout the full movement, and another expert performed relevant annotations.

2.2.2. PAPE Inducing Action

PAPE was induced in the second and fourth sessions with prior randomization. To obtain the PAPE values, lower limb and hip joint mobility exercises were carried out. A progressive warm-up with a first set of five repetitions at 30% 1RM in the exercise to be evaluated was performed just after. Later, a two-minute rest and a second set of five repetitions at 50% 1RM were performed, followed by the same rest time to perform a final set of three repetitions at 70% 1RM and a five-minute break. Three consecutive BJ with a 20 s rest period between them were performed, recording the jump distance obtained once the strength protocol was concluded.

BJ’s were performed with the participants standing and with slight flexion of the knees, with the feet slightly apart at shoulder width. Participants were placed behind a line set on the floor with a five cm adhesive tape. After a researcher signal, the assessed participant began the jump action by flexing the knees, directing arms, and hips back to propel forward, aiming to achieve the longest distance possible. Participants were instructed to land with both feet and try to maintain the position, staying upright to facilitate measurements. The nearest mark to the starting line, coinciding with the heels, was measured in cm with a Class I (0.1 mm of accuracy) measuring tape (Tornado Tools, Shenzhen, China).

After a five-minute rest, the second set of measurements was carried out, using two repetitions at 90% 1RM of the corresponding exercise, and an eight-minute pause was established, following the recommendations for an optimal recovery time [25,26]. Three BJs were carried out to verify if the PAPE effect was displayed. The three jumps were performed continuously, consuming only the time necessary for the participants’ preparation, which ranged between 15 and 20 s.

2.2.3. Analysis

The results were summarized as mean ± SD. Primary analyses followed an estimation framework: paired mean differences (Δ = Post − Pre) and effect sizes (Cohen’s d for paired change) were reported with 95% bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrap confidence intervals based on 5000 resamples, and permutation p-values from 5000 within-pair sign-flips [27]. Cohen’s d was interpreted using conventional benchmarks (0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large) [28], with the confidence interval used to qualify magnitude and precision. To test whether the conditioning protocols differentially affected the outcome, we fitted a two-way repeated-measures model with within-subject factors Time (Pre, Post) and Protocol (DL, HT); effect sizes for the main effects and the Time × Protocol interaction were expressed as partial eta squared (η2p) and interpreted using common thresholds (0.01 small, 0.06 medium, 0.14 large) [28,29]. Statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics v27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Python v3.12.11 (Python Software Foundation) using dabest-python v2025.03.27. The significance threshold was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

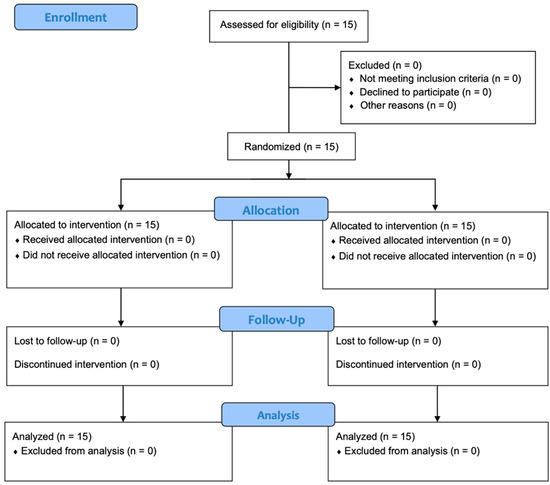

Figure 3 summarizes the CONSORT participant flow. Fifteen rugby players met the eligibility criteria, were enrolled, and completed the protocol. Baseline characteristics were: age 22.7 ± 1.6 years, body mass 89.9 ± 10.6 kg, stature 181.8 ± 6.5 cm, BMI 27.2 ± 2.3 kg/m2, DL 1RM 117.0 ± 20.6 kg, and HT 1RM 133.3 ± 21.5 kg.

Figure 3.

CONSORT flow diagram.

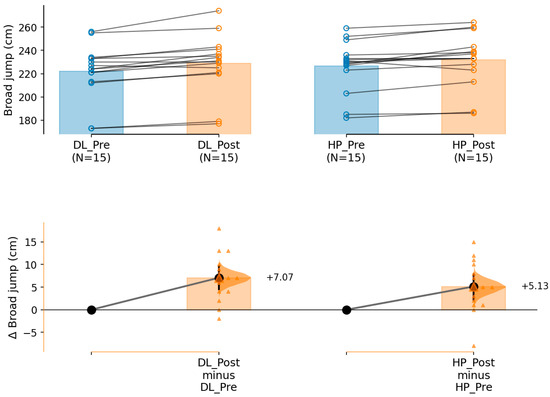

Turning to the primary outcome, broad jump performance improved under both conditioning protocols (Table 1). For DL, the mean paired increase was Δ = 7.1 cm (95% BCa CI 4.5–9.7), p < 0.001, with a small standardized mean change (d = 0.29, 95% CI 0.16–0.53). For HT, the mean paired increase was Δ = 5.1 cm (95% BCa CI excluding 0), p = 0.003, also showing a small effect (d = 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.43). Figure 4 presents the paired estimation plots, with the raw paired observations displayed above and the 95% BCa bootstrap confidence intervals for the paired mean differences below.

Table 1.

Pre–post change in broad jump and two-way repeated-measures effects by protocol.

Figure 4.

Paired estimation plots for the broad jump under two conditioning protocols (DL and HT). The upper axes show the raw paired observations; each participant’s Pre and Post values are connected by a line. The lower axes display the paired mean difference (Δ = Post − Pre) as a bootstrap sampling distribution (5000 BCa resamples). Mean differences are shown as dots, and the 95% BCa confidence intervals are indicated by the ends of the vertical error bars [27].

In the two-way repeated-measures model, there was a clear main effect of Time (p < 0.001; η2p = 0.707), whereas neither Protocol (p = 0.122; η2p = 0.162) nor the Time × Protocol interaction (p = 0.326; η2p = 0.069) reached significance (Table 1).

4. Discussion

The study examined whether the PAPE response differed when the standing BJ was performed after DL versus HT. Both protocols improved BJ performance, but no between-protocol difference was detected. The pre–post gains were small (d = 0.29 for DL; d = 0.23 for HT), and the model showed a main effect of Time with no effects for Protocol or the Time × Protocol interaction; therefore, our a priori hypothesis was not supported: HT did not elicit a greater PAPE effect on BJ than DL. Prior work in vertical-jump contexts suggests that heavy loads and adequate recovery can elicit PAPE [30]; however, transfer to a horizontal outcome may not favor one exercise over the other.

Due to the novelty of the force vector theory, few studies have been conducted with a similar scope to ours, limiting further comparison. Nevertheless, it has been demonstrated in professional soccer players that the use of squat exercise with an intensity range between 80% and 100% of 1RM implies subsequent performance improvements provided by eliciting PAPE [31]. In our study, using two repetitions at 90% 1RM with 8 min of rest, both DL and HT produced significant improvements in BJ, with no between-protocol differences. These pieces of research have also explored different exercise conditions (i.e., isometric, high loads) that can increase PAPE response. The different exercise/training methodologies conducted in our study (deadlift with axial force vector vs. hip thrust with anteroposterior force vector) have been selected because we hypothesized that they can induce distinct neuromuscular potentiation responses due to the principle of force vector specificity [16,32]. This concept proposes that strength and power gains are optimized when the direction of force application during the resistance training is in the same direction as that required in the target sport skill, or in our case, in the physical test. Therefore, deadlift (primarily vertical force production) and hip thrust (primarily horizontal force) might be expected to differentially affect tasks like the broad jump, which involves both vertical and horizontal force components [16,32,33].

The rationale for utilizing different protocols in our study is derived from this “principle vector specificity”, seeking to determine if force vector orientation can influence the magnitude of PAPE, as previously discussed by Randell et al. [16] The lack of significant differences found between protocols in our results is consistent with Seitz et al. [19], who reported similar PAPE magnitudes when force vector-specific protocols are used, provided that technical execution and load are appropriately prescribed.

Thus, we choose the protocol based on the underlying biomechanical and neuromuscular rationale and also aim to clarify if matching the force direction to the performance task (broad jump) yields differential acute enhancements.

Thus, the right “dose” of exercise and the proper rest time have been appropriately established. However, these exercise prescriptions should be applied in specific movements to obtain optimal results [34]. Therefore, the gap that our research aims to fill is to find out if athletes will obtain the same PAPE effect in different explosive efforts, such as BJ. Using the force vector approach, if the exercise used to stimulate PAPE is more similar to the subsequent motor pattern, its effectiveness will be increased. Many sports require predominantly horizontal force vector movements, such as COD or sprint [33]. Although horizontal jump distance seems to be a relevant power marker in athletic performance [15,35], the effects of PAPE on BJ have received little attention so far.

Previous research has evaluated the effects of PAPE on the BJ after an eccentric overload, with 12 participants performing a flywheel half-squat. Although the authors reported improvements in the BJ, those changes were lower than in the CMJ. In our study, no vertical test has been included, so the comparison between force vectors is not feasible, but we hypothesize similar results. Sue et al. [36], analyzing the effects on nine volleyball players who performed a five-repetition squat PAPE protocol (5RM), registered a BJ increase of 4.8% after 2 min of the execution of the primary exercise, and PAPE was reduced to 3.6% 6 and 10 min post-evaluation. In our study, significant increases of 3.15% for the DL and 2.29% for the HT were obtained after 8 min. Observing that the improvements described in our study are similar to those reported by Sue et al. [36], it could be inferred that the use of one or another force vector does not affect the subsequent activity if the appropriate PAPE protocols are met.

In the case of vertical jump, data from previous research are in agreement with the statement about the possibility that vector or force directional force specificity could not be essential in order to obtain the optimized PAPE. Recently, the conclusion by Arias et al. (2016) showed that five repetitions at 85% 1RM did not generate the PAPE effect, even though researchers highlighted an impairment in VJ performance [37]. Taken together, vector alignment may modulate transfer in some contexts, but heavy loading and recovery seem primary drivers of the acute response.

In this way, it has been reported a 5% increase in BJ after squatting at 70% 1RM, adding an elastic band (13.86 +/− 1.26%) [19]. It is important to note that the study mentioned above used contrast PAPE, performing two squat repetitions, followed by two horizontal jumps. The improvement of the horizontal jump records after vertical PAPE activities can be attributed to the fact that these activities increase the vertical take-off speed. Although the horizontal vector force is not better in those jumps, it will generate better subsequent performance, particularly in those individuals who have more experience in jumping horizontally [38].

Beyond the small but significant improvements observed in both protocols, the present findings align with a growing body of literature indicating that the magnitude of PAPE is strongly conditioned by load, rest interval, and training status, rather than exclusively by force-vector alignment. For example, Dobbs et al. (2019) reported in their meta-analysis that heavy loads (≥80% 1RM) combined with rest intervals between 6 and 10 min elicited the most consistent potentiation responses, regardless of the specific exercise pattern [30]. This echoes our observations, where both DL and HT—despite different mechanical orientations—produced comparable improvements in BJ performance.

Furthermore, when considering the role of vector specificity, our results partially contrast with early theoretical proposals by Randell et al. (2010), who suggested superior transfer when the conditioning exercise shared the primary direction of force application with the subsequent task [16]. However, more recent experimental evidence indicates that vector specificity may not always determine acute PAPE responses. For instance, other studies found that heavy squats improved horizontal sprinting performance despite being vertically oriented exercises. These findings suggest that global neuromuscular excitation, rather than mechanical specificity, may drive short-term potentiation [39].

The absence of meaningful differences between DL and HT in our study also agrees with Urbanski et al. (2023), who demonstrated similar acute jumping potentiation from HT and back squat when rest intervals were optimized [20]. Their work proposed that both exercises sufficiently activate the hip extensors—key contributors to horizontal displacement—potentially explaining why vector differences did not translate into divergent outcomes in BJ.

Another factor to consider is the training background of our participants. It has been widely documented that highly trained athletes exhibit more stable and predictable potentiation responses [26,40], likely due to greater type II fiber proportion, faster recovery kinetics, and more efficient force transmission. Since all players in the present study were resistance-trained rugby athletes, their advanced neuromuscular profile may have reduced variability between protocols and minimized the influence of vector direction. Likewise, previous research emphasized that potentiation and fatigue coexist dynamically, and that athletes with higher maximal strength typically achieve a more favorable balance between the two mechanisms, another possible explanation for the similarity between DL and HT effects [41].

It is also important to contextualize the magnitude of the observed improvements. While increases of 2–3% in BJ may appear modest, comparable magnitudes have been reported in controlled studies using both vertical and horizontal conditioning stimuli [36,38]. Given that BJ is a multi-planar, highly coordinative task involving simultaneous vertical and horizontal force production, it is possible that neither exercise perfectly matches its mechanical profile. Therefore, acute potentiation might depend more on the overall ability to enhance hip extension velocity and rate of force development, rather than replicating a specific vector.

Finally, the present findings contribute to the ongoing debate regarding the practical application of the force-vector theory. While several chronic training studies [18,42] have demonstrated vector-specific long-term adaptations, acute potentiation responses appear less sensitive to vector alignment. This distinction is crucial for practitioners: chronic adaptations may favor vector-specific design, whereas acute warm-up strategies can remain more flexible, as long as load, intent, and recovery are appropriately prescribed.

Eventually, after discussing our data, we hypothesized several possible explanations for our results:

- Both DL and HT may effectively potentiate the hip extensors relevant to BJ, leading to similar net transfer despite differences in vector orientation.

- Training status and specific BJ experience likely condition the magnitude of the acute PAPE response

Overall, it can be suggested that in highly trained individuals, the application of a PAPE protocol on the improvement of BJ can be implemented with either DL (anteroposterior/axial loading) or HT (hip-dominant), yielding small but significant gains without clear differences between protocols. Both strategies will increase the capacity to generate muscular power.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that both the deadlift (DL) and hip thrust (HT) exercises, when performed with high loads and followed by an adequate rest interval, acutely enhance horizontal jump performance (broad jump) in trained rugby players, with no significant difference between the two protocols. This data suggests that strength and conditioning coaches may select either approach to induce post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) prior to explosive tasks, depending on individual athlete profiles and sport-specific demands.

Future research should aim to investigate the effects of different vector direction protocols on different populations, such as female athletes, youth players, or those with varying strength and years of experience. Moreover, studies could consider the inclusion of velocity-based monitoring (e.g., encoder), evaluation of neuromuscular and physiological markers (e.g., muscle fiber composition, electromyographic activity), and compare additional exercises like the squat or isometric protocols to broaden understanding of force vector specificity on both acute and even chronic sport performance outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size on our intervention may be reduced and show specific particularities, not allowing extrapolation of the obtained results to other populations. Given that the literature shows that PAPE generates a response with high interindividual heterogeneity, better results have been found in advanced participants, who usually execute power movements in their workouts [40]. In addition, the phosphorylation potential of every athlete after a maximum voluntary contraction is very individual [43].

Another limitation of our piece of research is the absence of a histological study to determine the predominant fiber ratio. Muscle fiber composition can be a factor generating high variability in the results; with a more significant proportion of type II fibers, the magnitude of the PAPE effect may be enhanced [44].

From a practical perspective, a velocity-based training (VBT) monitoring tool (e.g., encoder) could have been used to obtain greater precision both in assessing 1RM and in obtaining a more accurate value of the stimulus provided.

Finally, it is essential to highlight that we have not included in our study any axial-vector exercises such as the squat, but we hypothesize that we would have achieved similar results to those found by previous studies [36].

5. Conclusions

Performing deadlift (DL) or hip thrust (HT) with heavy loading (2 × 90% 1RM) and 8 min recovery elicited small but significant acute improvements in standing broad jump (BJ) performance, with no difference between protocols. Accordingly. Thus, strength coaches and practitioners may select both exercises for inducing PAPE indistinctly, according to their personal preferences or specific sport skills.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., J.B.-P. and S.V.-M.; Methodology, L.C., J.B.-P. and N.C.; Formal Analysis, J.P. and J.L.P.; Investigation, L.C., S.V.-M., J.B.-P., D.A.B. and I.C.; Data Curation, J.P. and J.L.P.; Writing—Preparation of Original Draft, N.C., L.C., I.C. and S.V.-M.; Writing—Review and Editing, N.C., I.C., S.V.-M. and L.C.; Visualization, N.C., L.C., I.C., D.A.B., J.B.-P., J.L.P., J.P. and S.V.-M. Supervision, N.C., L.C., I.C., D.A.B., J.B.-P., J.L.P., J.P. and S.V.-M. Project administration, L.C., S.V.-M. and J.B.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee for Experimentation of the University of Malaga (CEUMA 52-2025-H).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors (benitez@uma.es, salvadorvargasmolina@gmail.com).

Conflicts of Interest

N.C. and S.V.-M receive honoraria for personalized training services. I.C.M., L.C., D.A.B. has conducted academic-sponsored research in sport and exercise sciences, serve as NSCA Spain and Latam board members, and has received honoraria for speaking on exercise sciences at international conferences and private courses. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PAPE | Post-activation performance enhancement |

| PAP | Post-activation potentiation |

| RM | Repetition maximum |

| COD | Change of direction |

| DL | Deadlift |

| HT | Hip thrust |

| BJ | Broad jump |

| CMJ | Countermovement jump |

| CI | Confidence interval |

References

- Hodgson, M.; Docherty, D.; Robbins, D. Post-activation potentiation: Underlying physiology and implications for motor performance. Sports Med. 2005, 35, 585–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazevich, A.J.; Babault, N. Post-activation Potentiation Versus Post-activation Performance Enhancement in Humans: Historical Perspective, Underlying Mechanisms, and Current Issues. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintosh, B.R.; Robillard, M.E.; Tomaras, E.K. Should postactivation potentiation be the goal of your warm-up? Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.L.; Docherty, D. Acute effects of heavy preloading on vertical and horizontal jump performance. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2004, 18, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, A.L.; Fernandes, I.A.; Cesar, E.P.; Silva, W.A.; Gomes, P.S. The effects of rest intervals on jumping performance: A meta-analysis on post-activation potentiation studies. J. Sports Sci. 2013, 31, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasicki, K.; Rydzik, Ł.; Ambroży, T.; Spieszny, M.; Koteja, P. The Impact of Post-Activation Performance Enhancement Protocols on Vertical Jumps: Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobal, R.; Pereira, L.A.; Kitamura, K.; Paulo, A.C.; Ramos, H.A.; Carmo, E.C.; Roschel, H.; Tricoli, V.; Bishop, C.; Loturco, I. Post-Activation Potentiation: Is there an Optimal Training Volume and Intensity to Induce Improvements in Vertical Jump Ability in Highly-Trained Subjects? J. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 66, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Molina, S.; Salgado-Ramirez, U.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Carbone, L.; Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Benitez-Porres, J. Comparison of post-activation performance enhancement (PAPE) after isometric and isotonic exercise on vertical jump performance. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0260866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz, J.; Gawel, D.; Socha, I.; Ewertowska, P.; Wilk, M.; Lum, D.; Krzysztofik, M. Acute Effects of Isometric Conditioning Activity with Different Set Volumes on Countermovement Jump Performance in Highly Trained Male Volleyball Players. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boullosa, D.; Del Rosso, S.; Behm, D.G.; Foster, C. Post-activation potentiation (PAP) in endurance sports: A review. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2018, 18, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, L.; Garzon, M.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Bonilla, D.A.; Alonso, D.A.; Benitez-Porres, J.; Petro, J.L.; Vargas-Molina, S. Effects of heavy barbell hip thrust vs back squat on subsequent sprint performance in rugby players. Biol. Sport. 2020, 37, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietraszewski, P.; Gołaś, A.; Zając, A.; Maćkała, K.; Krzysztofik, M. The Acute Effects of Combined Isometric and Plyometric Conditioning Activities on Sprint Acceleration and Jump Performance in Elite Junior Sprinters. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sale, D.G. Postactivation potentiation: Role in human performance. Exerc. Sport. Sci. Rev. 2002, 30, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, D.W. Postactivation potentiation and its practical applicability: A brief review. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuzaini, K.S.; Fleck, S.J. Modification of the standing long jump test enhances ability to predict anaerobic performance. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2008, 22, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randell, A.D.; Cronin, J.B.; Keogh, J.W.L.; Gill, N.D. Transference of Strength and Power Adaptation to Sports Performance—Horizontal and Vertical Force Production. Strength. Cond. J. 2010, 32, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Strength & Conditioning Association; Haff, G.; Triplett, T. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 4th ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, B.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Beardsley, C.; McMaster, D.T.; Reyneke, J.H.; Cronin, J.B. Effects of a Six-Week Hip Thrust vs. Front Squat Resistance Training Program on Performance in Adolescent Males: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, L.B.; Mina, M.A.; Haff, G.G. Postactivation Potentiation of Horizontal Jump Performance Across Multiple Sets of a Contrast Protocol. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 2733–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbański, R.; Biel, P.; Kot, S.; Perenc, D.; Aschenbrenner, P.; Stastny, P.; Krzysztofik, M. Impact of active intra-complex rest intervals on post-back squat versus hip thrust jumping potentiation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Sillero, M.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Bonilla, D.A.; Vargas-Molina, S.; Benitez-Porres, J. Effects of Preceding Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Movement Velocity and EMG Signal during the Back Squat Exercise. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Jama 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechle, T.R.; Earle, R.W.; National Strength & Conditioning Association. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 3rd ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, V.; Fimland, M.S.; Mo, D.A.; Iversen, V.M.; Vederhus, T.; Rockland Hellebo, L.R.; Nordaune, K.I.; Saeterbakken, A.H. Electromyographic Comparison of Barbell Deadlift, Hex Bar Deadlift, and Hip Thrust Exercises: A Cross-Over Study. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilduff, L.P.; Owen, N.; Bevan, H.; Bennett, M.; Kingsley, M.I.; Cunningham, D. Influence of recovery time on post-activation potentiation in professional rugby players. J. Sports Sci. 2008, 26, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.M.; Duncan, N.M.; Marin, P.J.; Brown, L.E.; Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, S.M.; Jo, E.; Lowery, R.P.; Ugrinowitsch, C. Meta-analysis of postactivation potentiation and power: Effects of conditioning activity, volume, gender, rest periods, and training status. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, J.; Tumkaya, T.; Aryal, S.; Choi, H.; Claridge-Chang, A. Moving beyond P values: Data analysis with estimation graphics. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 565–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.T.E. Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2011, 6, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, W.C.; Tolusso, D.V.; Fedewa, M.V.; Esco, M.R. Effect of Postactivation Potentiation on Explosive Vertical Jump: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2009–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petisco, C.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Hernandez, D.; Gonzalo-Skok, O.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J. Post-activation Potentiation: Effects of Different Conditioning Intensities on Measures of Physical Fitness in Male Young Professional Soccer Players. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, B.; Vigotsky, A.D.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Beardsley, C.; Cronin, J. A Comparison of Gluteus Maximus, Biceps Femoris, and Vastus Lateralis Electromyographic Activity in the Back Squat and Barbell Hip Thrust Exercises. J. Appl. Biomech. 2015, 31, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackala, K.; Stodółka, J.; Siemienski, A.; Coh, M. Biomechanical analysis of standing long jump from varying starting positions. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2674–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. Fundamentals of resistance training: Progression and exercise prescription. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 674–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, T.D.; Reeves, N.D.; Baltzopoulos, V.; Jones, D.A.; Maganaris, C.N. Strong relationships exist between muscle volume, joint power and whole-body external mechanical power in adults and children. Exp. Physiol. 2009, 94, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ah Sue, R.; Adams, K.J.; DeBeliso, M. Optimal Timing for Post-Activation Potentiation in Women Collegiate Volleyball Players. Sports 2016, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, J.C.; Coburn, J.W.; Brown, L.E.; Galpin, A.J. The Acute Effects of Heavy Deadlifts on Vertical Jump Performance in Men. Sports 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanis, G.C.; Tsoukos, A.; Veligekas, P. Improvement of Long-Jump Performance During Competition Using a Plyometric Exercise. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017, 12, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, L.B.; Haff, G.G. Factors Modulating Post-Activation Potentiation of Jump, Sprint, Throw, and Upper-Body Ballistic Performances: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, L.Z.; Fry, A.C.; Weiss, L.W.; Schilling, B.K.; Brown, L.E.; Smith, S.L. Postactivation potentiation response in athletic and recreationally trained individuals. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2003, 17, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tillin, N.A.; Bishop, D. Factors modulating post-activation potentiation and its effect on performance of subsequent explosive activities. Sports Med. 2009, 39, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McErlain-Naylor, S.; King, M.; Pain, M.T. Determinants of countermovement jump performance: A kinetic and kinematic analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.C.; Fry, A.C. Effects of a ten-second maximum voluntary contraction on regulatory myosin light-chain phosphorylation and dynamic performance measures. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, T.; Sale, D.G.; MacDougall, J.D.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Postactivation potentiation, fiber type, and twitch contraction time in human knee extensor muscles. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 2131–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).