Flow Characteristics of a Fully Developed Concentric Annular Turbulent Flow

Abstract

1. Introduction

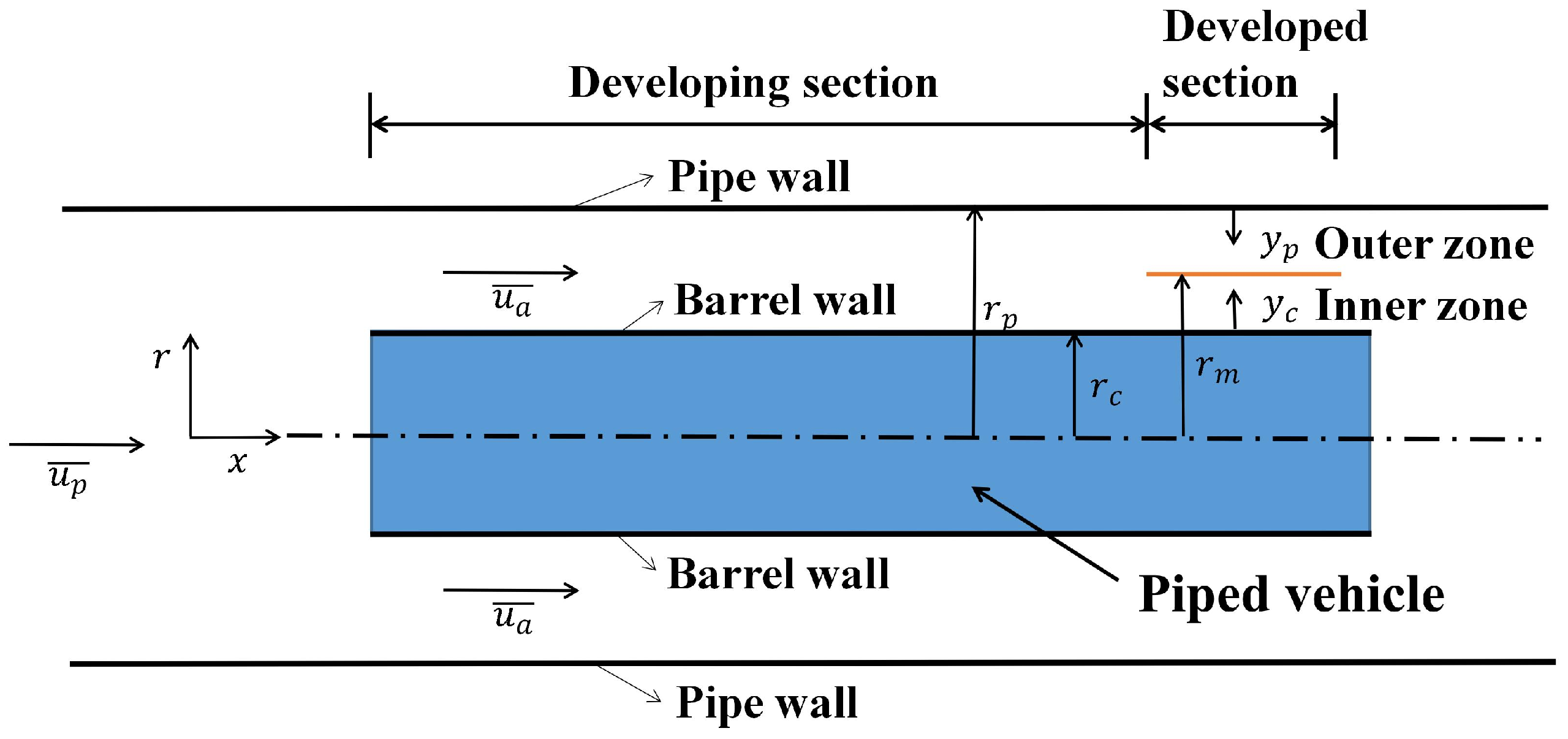

2. Theoretical Analysis

- (a)

- For the viscous sublayer ()

- (b)

- For the turbulent region ()

- (a)

- For the viscous sublayer ()

- (b)

- For the turbulent region ()

3. Experimental Scheme

3.1. Experimental System

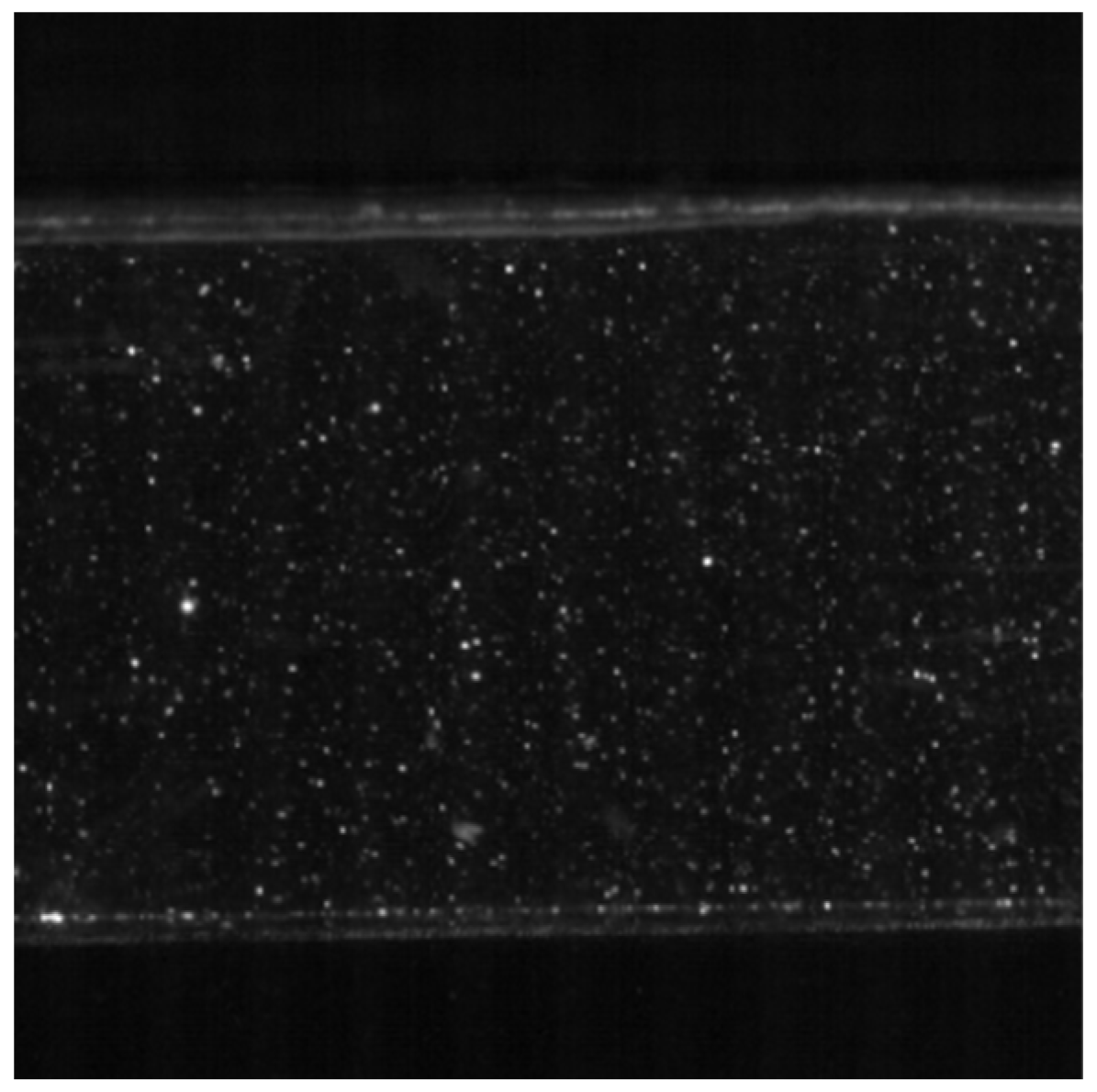

3.2. Measuring Device

3.3. Experimental Program Design

3.3.1. Test Conditions

3.3.2. Arrangement of Test Section and Test Points

4. Results and Discussion

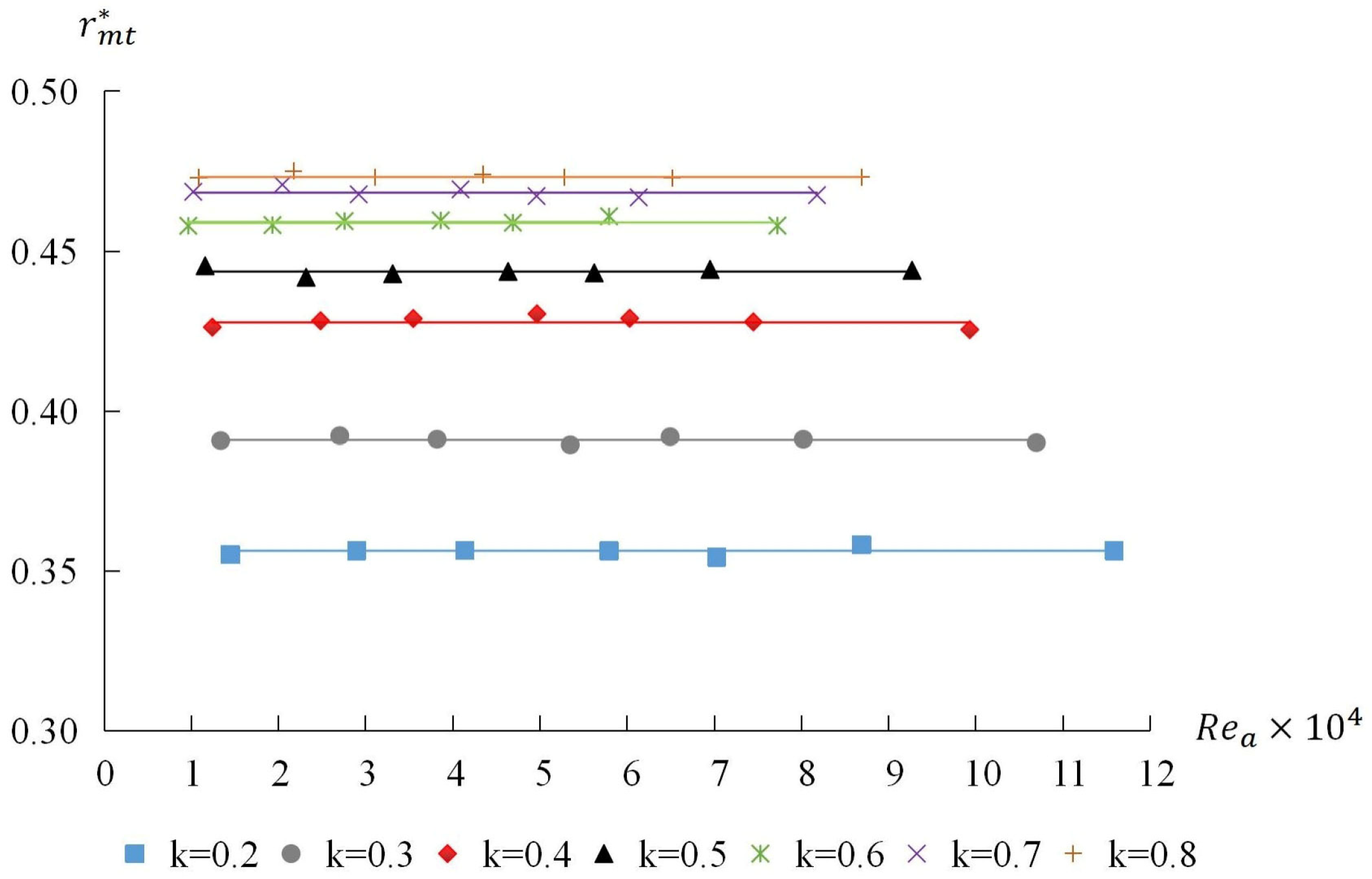

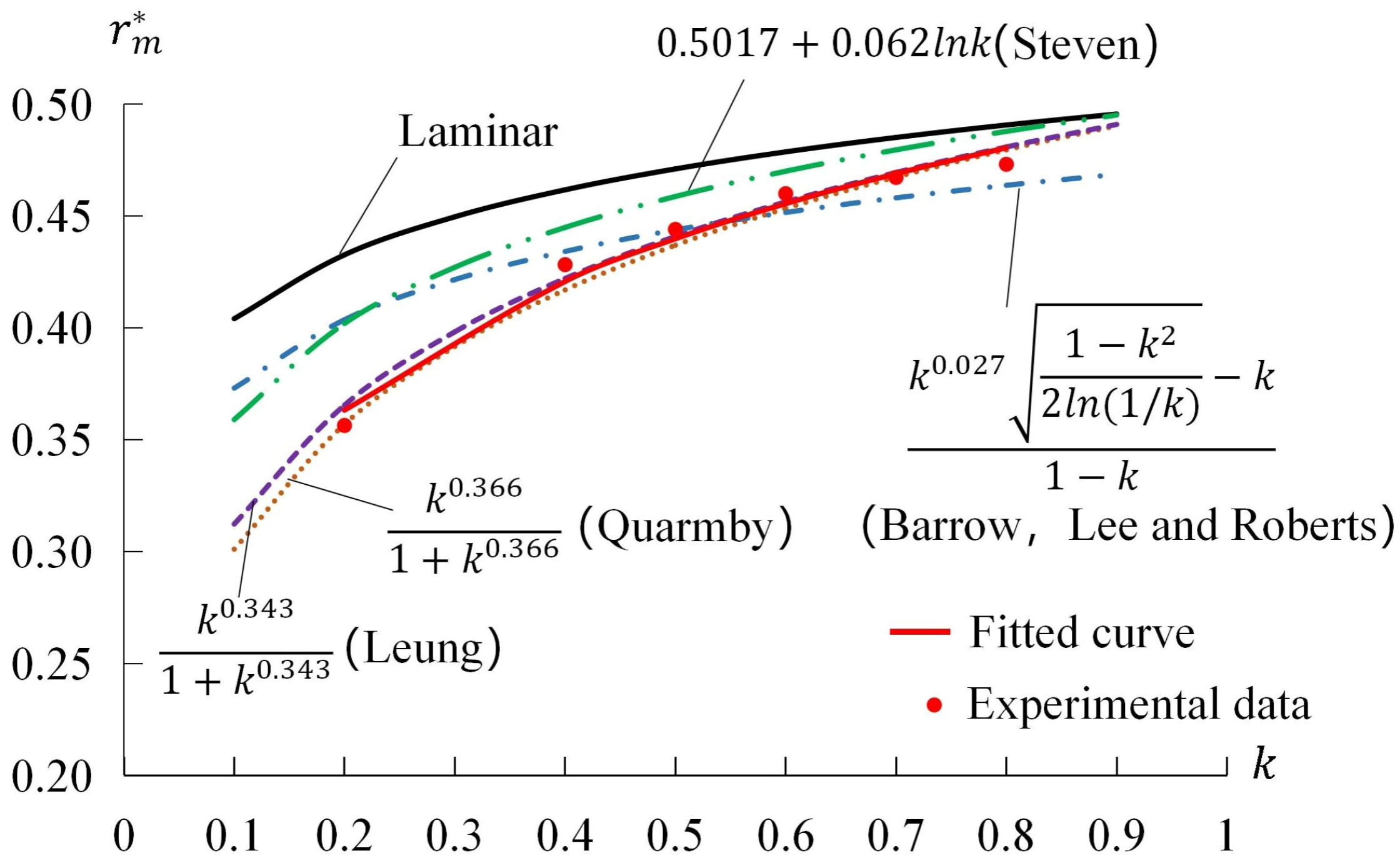

4.1. Position of the Maximum Velocity

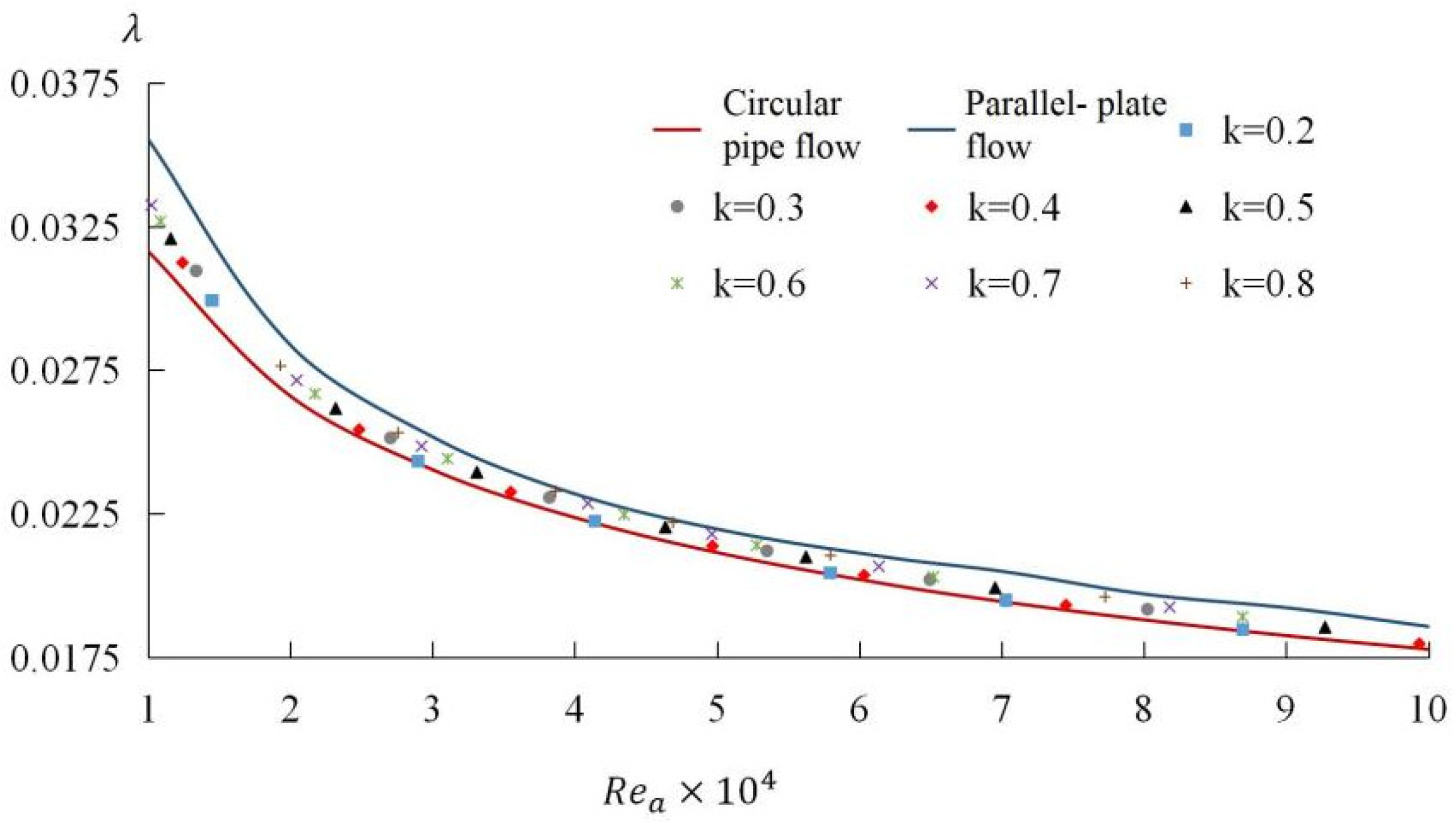

4.2. Resistance Characteristic

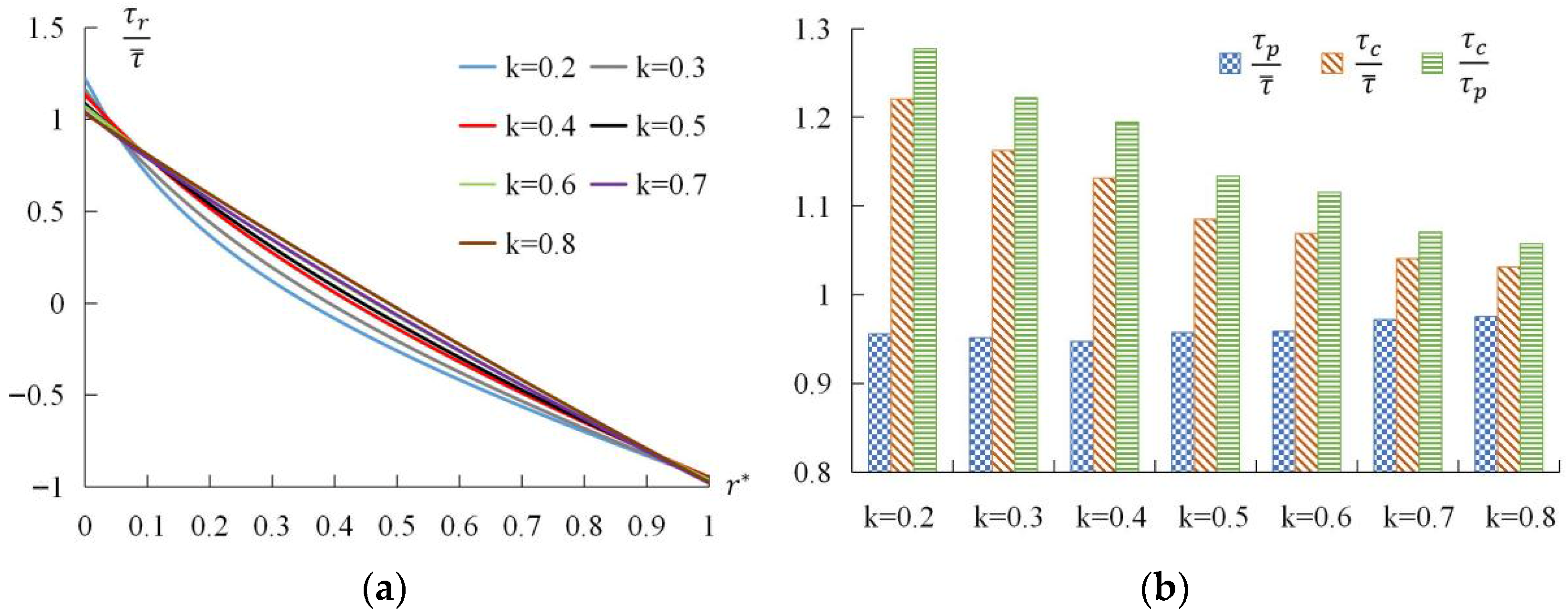

4.3. Shear Stress

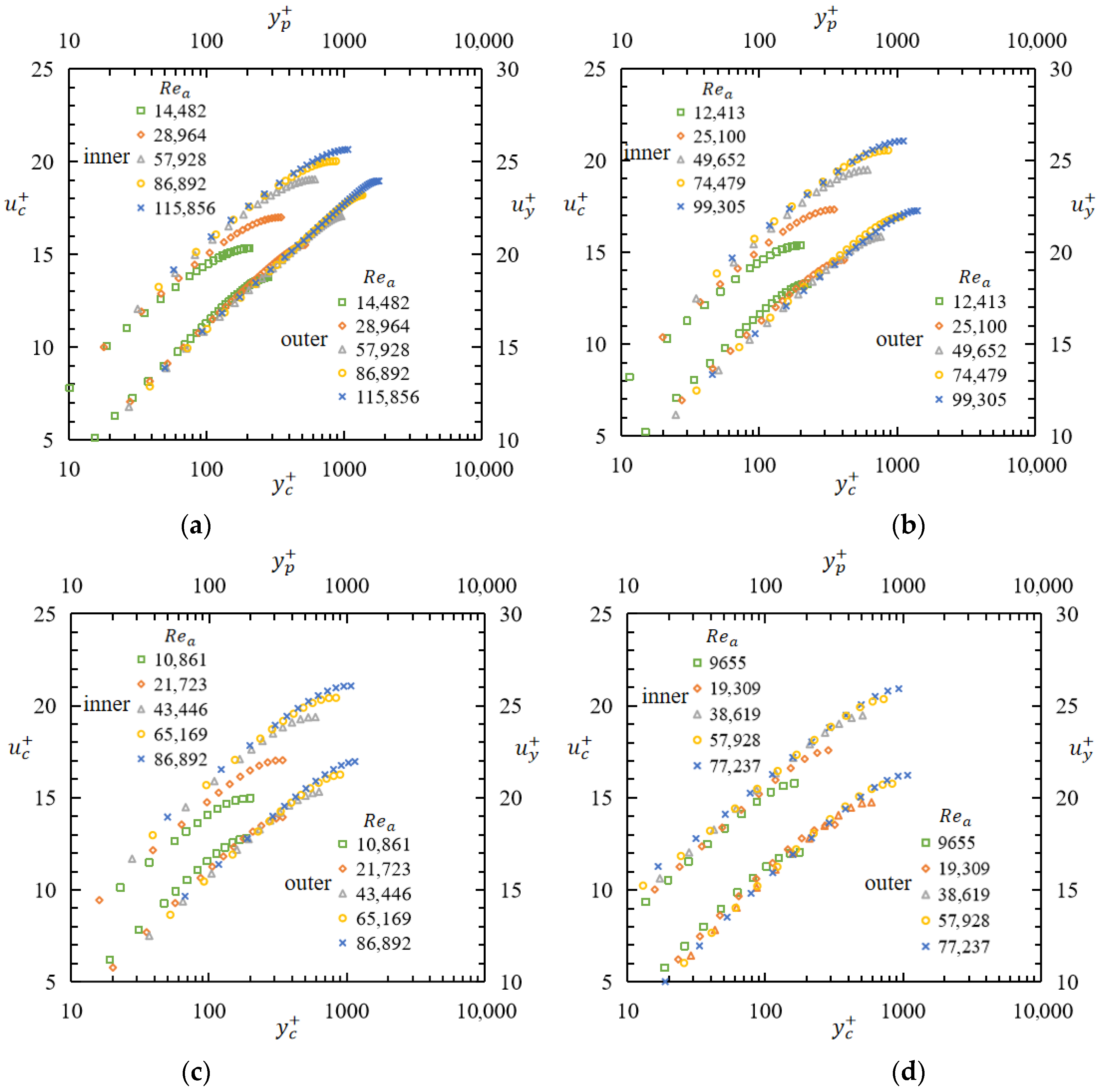

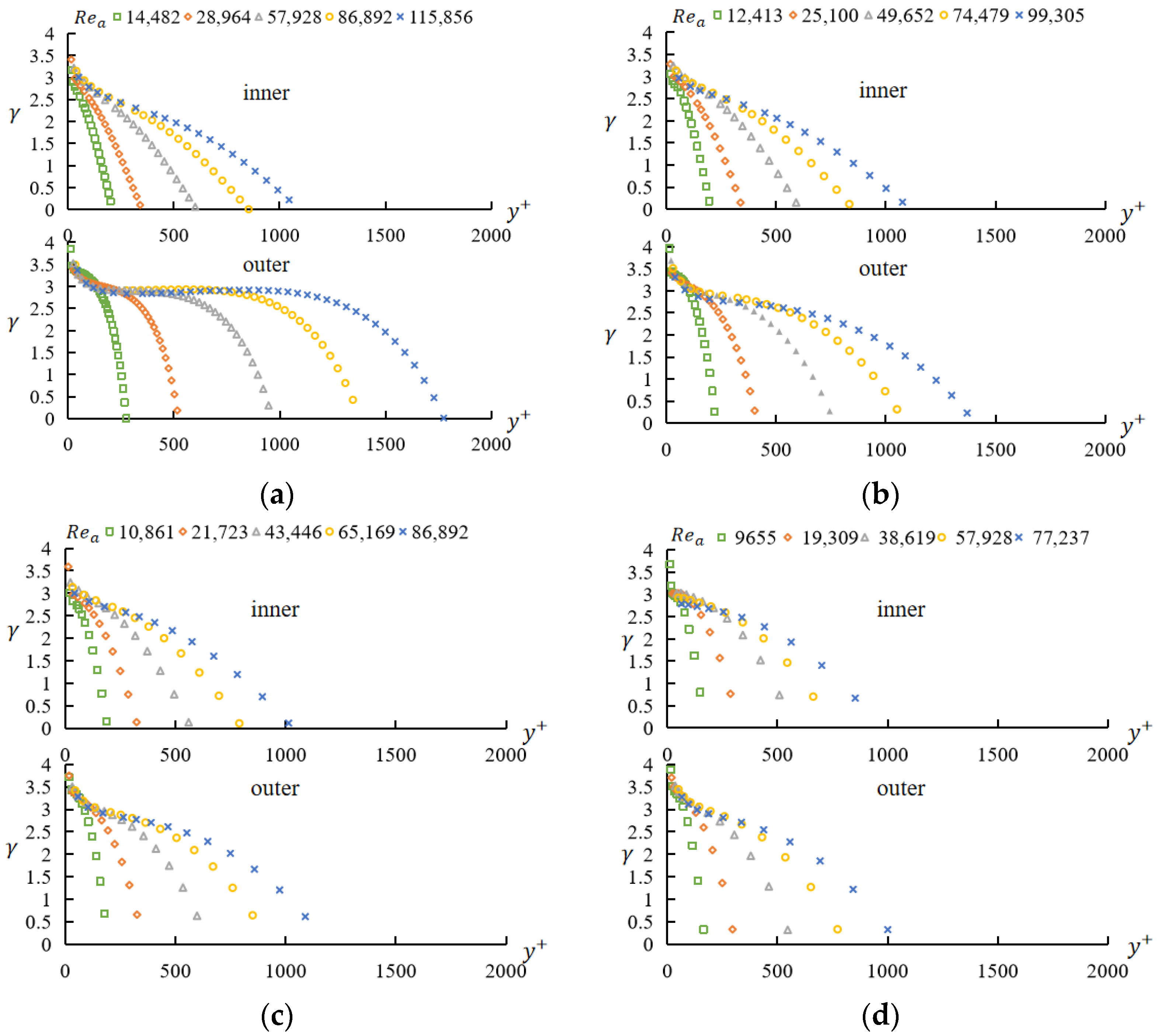

4.4. Velocity Distribution

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- For both laminar and turbulent flows, the maximum velocity did not occur at the center of the annular flow but biased towards the barrel wall. The smaller the radius ratio, the more it shifted towards the barrel wall. The position of the maximum velocity in turbulent flow was more biased towards the barrel wall than that in laminar flow. As the radius ratio increased, the position of the maximum velocity in turbulent flow approached that in laminar flow.

- (2)

- For both laminar and turbulent flows, the resistance coefficient of annular flow was independent of the radius ratio, that is, was a univariate function of the annular Reynolds number (). The relationship between the resistance coefficient of annular turbulent flow and the annular Reynolds number fitted from the experimental results was

- (3)

- At small radius ratios, the variation curves of shear stress in annular turbulent flow were curved and steep in the inner region but relatively flat in the outer region. As the radius ratio increased, the curves became flatter. The shear stress on the barrel wall was always greater than that on the pipe wall. As the radius ratio increased, the shear stress on the barrel wall decreased while the shear stress on the pipe wall increased.

- (4)

- The dimensionless velocity distribution in annular turbulent flow was related to both the Reynolds number and the radius ratio. In the inner region, the influence of the Reynolds number was more obvious than that of the radius ratio, and the average gradient of the curves increased with the increase in the Reynolds number. In the outer region, the average gradient of the curves decreased with the increase in the Reynolds number, and the Reynolds number effect was minimized with the decrease in the radius ratio. The velocity distribution in annular turbulent flow cannot be expressed by a unified relation, but there was a logarithmic region in the velocity distribution at high Reynolds numbers in the outer region, and the slope of the logarithmic region was greater than that in circular pipe flow and parallel-plate flow.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, X.L.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.L. The research of the concentric ring slit flow. J. Anhui Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2004, 24, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.N.; Sun, L.C.; Yan, C.Q.; Huang, W.T. Experimental investigation of single-phase flow friction in narrow annuli. Nucl. Power Eng. 2004, 25, 123–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nesterov, G.N.; Spiridonov, F.F. Flow of a viscous fluid in an annular gap with intensive blowing from the walls. Fluid Dyn. 1987, 22, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, F.G.; Colburn, A.P.; Schoenborn, E.M.; Wurster, A. Heat transfer and friction of water in an annular space. Trans. Am. Inst. Chem. Eng. 1946, 42, 165. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfus, R.R.; Monrad, C.C.; Senecal, V.E. Velocity distribution and fluid friction in smooth concentric annuli. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1948, 42, 2511–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehme, K. Turbulent flow in smooth concentric annuli with small radius ratios. Fluid Mech. 1974, 64, 263–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellstrom, B.; Hedberg, S. On Shear Stress Distributions for Flow in Smooth or Partially Rough Annuli; Aktiebolagent Atomenergi: Stockholm, Sweden, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfus, R.R.; Monrad, C.C.; Sikchi, K.G.; Heideger, J. Isothermal skin friction in flow through annular sections. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1955, 47, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothfus, R.R. Velocity Distribution and Fluid Friction in Concentric Annuli; Carnegie Institute of Technology: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, J.G.; Katz, D.L. Velocity profiles in annuli. In Proceedings of the Midwestern Conference on Fluid Dynamics, Barna-Champaign, IL, USA, 12–13 May 1950; pp. 175–203. [Google Scholar]

- Brighton, J.A.; Jones, J.B. Fully developed turbulent flow in annuli. ASME J. Basic Eng. 1964, 86, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, A. An experimental study of turbulent flow through concentric annuli. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1967, 9, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, A. An analysis of turbulent flow in concentric annuli. Appl. Sci. Res. 1968, 19, 250–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, V.K.; Sparrow, E.M. Experiments on turbulent-flow phenomena in eccentric annular ducts. J. Fluid Mech. 1966, 25, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steven, J.K. Turbulent Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer in Annular Passages with Rough Surfaces and Moving Cores. Master’s Thesis, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Shigechi, T.; Kawae, N.; Lee, Y. Turbulent fluid flow and heat transfer in concentric annuli with moving cores. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1990, 33, 2029–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.R.; Li, X.B.; Liu, Y.C. Study and experiment on flow behavior of pressurized-water in annular micro-gaps. China Mech. Eng. 2005, 16, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P.; Hrnjak, P. A mechanistic model in annular flow in microchannel tube for predicting heat transfer coefficient and pressure gradient. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 203, 123805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.Z. Analytical and Numerical Investigations of Flow Characteristics of Annular Microchannel. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.W. Numerical Simulation of Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics in Annular Microchannels. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Institute of Petrochemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, K.G.; Yan, S.F. Study on flow friction experimental characteristics in narrow annuli. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2010, 32, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, K.; Xiong, X.H.; Zhang, C.; Lai, G.C. Experimental study on the fluid resistance characteristics in micro-gaps. China Chem. Trade 2017, 9, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J.; Feng, D.Y. Experimental investigation of flow friction characteristic in annuli. J. Exp. Fluid Mech. 2011, 25, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Düz, H. Numerical and experimental study to predict the entrance length in pipe flows. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2019, 12, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kays, W.M.; Leung, E.Y. Heat transfer in annular passages–hydrodynamically developed turbulent flow with arbitrarily prescribed heat flux. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1963, 6, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, H.; Lee, Y.; Roberts, A. The similarity hypothesis applied to turbulent flow in an annulus. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1965, 8, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hama, F.R. Boundary layer characteristics for smooth and rough surfaces. Trans. Soc. Nav. Arch. Mar. Eng. 1954, 62, 333–358. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, G.Y.; Sun, Z.N.; Wang, J.; Yan, C.Q. Experimental investigation on the single-phase flow friction in narrow annulus. Nucl. Power Eng. 2006, 27, 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, S.W.; Chan, C. Improved correlating equation for the friction factor in fully developed turbulent flow in round tubes and between identical parallel plates, both smooth and rough. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1994, 33, 2016–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauser, F.H. The turbulent boundary layer. Adv. Appl. Mech. 1956, 4, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, R.D.; Kim, J.; Mansour, N.N. Direct numerical simulation of turbulent channel flow up to Reτ = 590. Phys. Fluids 1999, 11, 943–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Re | = 0.2 | = 0.3 | = 0.4 | = 0.5 | = 0.6 | = 0.7 | = 0.8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17,378 | 14,482 | 13,368 | 12,413 | 11,586 | 10,861 | 10,223 | 9655 |

| 34,757 | 28,964 | 27,031 | 24,826 | 23,171 | 21,723 | 20,445 | 19,309 |

| 49,652 | 41,377 | 38,194 | 35,466 | 33,102 | 31,033 | 29,207 | 27,585 |

| 69,513 | 57,928 | 53,472 | 49,652 | 46,342 | 43,446 | 40,890 | 38,619 |

| 84,335 | 70,279 | 64,930 | 60,292 | 56,224 | 52,756 | 49,609 | 46,894 |

| 104,270 | 86,892 | 80,208 | 74,479 | 69,513 | 65,169 | 61,335 | 57,928 |

| 139,027 | 115,856 | 106,944 | 99,305 | 92,685 | 86,892 | 81,780 | 77,237 |

| Proposers | Empirical Formulas |

|---|---|

| Kays [25] | |

| Quarmy [13] | |

| Barrow [26] | |

| Steven [15] |

| k | C | m | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.2 | 0.3175 | 0.2496 | 0.9967 |

| 0.3 | 0.3192 | 0.2489 | 0.9978 |

| 0.4 | 0.3193 | 0.2503 | 0.9959 |

| 0.5 | 0.3165 | 0.2483 | 0.9971 |

| 0.6 | 0.3176 | 0.2481 | 0.9959 |

| 0.7 | 0.3180 | 0.2478 | 0.9952 |

| 0.8 | 0.3198 | 0.2480 | 0.9931 |

| Average | 0.3183 | 0.2487 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, L.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Flow Characteristics of a Fully Developed Concentric Annular Turbulent Flow. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13161. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413161

Sun L, Sun X, Li Y, Wang L. Flow Characteristics of a Fully Developed Concentric Annular Turbulent Flow. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13161. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Lei, Xihuan Sun, Yongye Li, and Lianle Wang. 2025. "Flow Characteristics of a Fully Developed Concentric Annular Turbulent Flow" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13161. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413161

APA StyleSun, L., Sun, X., Li, Y., & Wang, L. (2025). Flow Characteristics of a Fully Developed Concentric Annular Turbulent Flow. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13161. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413161