Abstract

The objective of this work was to evaluate the potential of PEF application on the decrease in orange peel air-drying time and temperature, resulting in energy savings. Orange peel waste (by-product of squeezable orange juice typical production, with a moisture content of 70%) was PEF pretreated (1.0–5.0 kV/cm electric field strength, frequency of 20 Hz, pulse width 15 μs, >1000 pulses), achieving a cell disintegration index Z ranging from 0.1 to 0.8. Drying experiments of PEF-treated orange peels were carried out at mild temperatures (40–70 °C). The moisture diffusion coefficients Deff and the air-drying energy consumed of all samples were estimated and compared. At low drying temperatures (<55 °C), PEF treatment led to increased effective moisture diffusivity Deff by up to 25%, resulting in reduced drying time and energy savings up to 15 MJ/kg, compared to untreated samples. More intense PEF conditions resulted in higher drying rates, while, for temperatures > 60 °C, there was no significant effect on the moisture diffusion coefficient for PEF pretreated samples. PEF treatment did not lead to changes in the antioxidant activity of dried samples. The results showed the potential of PEF pretreatment to accelerate the drying process of orange peel waste minimizing energy consumption.

1. Introduction

Agro-industrial waste refers to materials left over from farming and food production processes. Orange production has surged globally, resulting in a significant increase in fruit waste, particularly orange peels [1,2]. These peels, comprising over half of the fruit, are typically discarded during juice extraction [2]. However, they contain valuable compounds like natural antioxidants [3,4].

Orange peel waste, with its low pH (3–4), high water content (75–85%), and organic matter (95% of total solids), poses contamination risks near production sites [5]. Typically, it is either used as animal feed in a dried form or burned, necessitating better management strategies. One alternative solution involves implementing new processes to repurpose this waste into organic fertilizers or source for extraction of pectin, bio-oil, essential oils, antioxidants, and valuable compounds, like microbial proteins and organic acids [6]. Moreover, to effectively utilize these by-products, it is crucial to implement a dehydration step before spoilage-fermentation occurs. However, orange peel is highly perishable due to its high moisture content [7]. Drying aims to reduce water activity in food to extend shelf life, causing physical and chemical changes [8,9]. Its advantages include reduced shipping costs and the ability to tailor product characteristics while managing crop surplus. However, conventional drying methods, particularly convective drying, are energy-intensive and costly, with significant environmental impacts [8,10,11]. Furthermore, limiting the time that a material is subjected to elevated temperatures tends to preserve the nutritional properties of the resulting food product [11,12]. Efforts to reduce process time not only cut costs and minimize the environmental issues but also preserve the nutritional value of orange peel waste, making it suitable for incorporation into new food products.

Recent research in food drying focuses on shortening drying times through technological advancements, like infrared drying or pretreatment methods, such as high hydrostatic pressure, ultrasounds, and pulsed electric fields, emphasizing both economic and environmental considerations. Pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment in food drying refers to the application of high-voltage electrical pulses to food materials before the drying process. Mild conditions with electric fields <5 kV/cm are required to improve mass transfer phenomena. This treatment alters the cellular structure of the food, facilitating moisture removal during drying and reducing drying time. PEF pretreatment has gained attention in recent years due to its ability to improve drying efficiency, preserve nutritional quality, and enhance product characteristics while minimizing energy consumption and environmental impact. The literature reports potential applications of PEF as a pretreatment in dehydration processes for fruits and vegetables, such as potatoes [13], carrot slices [14], red bell pepper [15], apple slices [16] and zucchini slices [17]. Limited research exists on the drying of orange peel, with only few relevant papers identified, concerning the mathematical description of different types of drying, such as solar drying [18], microwave drying [19], convective and freeze drying [20].

Physical or mathematical models play a crucial role in simulating the drying process and predicting desired property values. The overprocessing of orange peel waste in drying can influence its functional properties. Garau, Simal, Rossello, and Femenia [21] emphasized the importance of controlling air-drying temperature to maintain the quality of dietary fiber and antioxidant capacity in orange by-products, as prolonged or high drying temperatures may lead to degradation or modification.

Therefore, to address gaps in the current scientific understanding of orange peel drying, the main objectives of this study were as follows: (a) to investigate the effect of pulsed electric fields (PEF) on the acceleration of orange peel waste drying and on energy saving; (b) to mathematically describe the drying process, using various models reported in the literature; and (c) to comparatively assess the quality and the antioxidant content of the final untreated and PEF pretreated dried orange peel waste.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

Orange waste was provided from a fruit processing plant from Argolida region (Navel cv.), in Greece. Orange waste was a homogenous mixture consisting of peels, unpressed oranges and residual orange juice. The unpressed oranges were manually removed, and the mixture was filtered to separate the liquid fraction. The solid residue consisted exclusively of orange peels. Before drying, several pretreatment steps were applied. First, the peels were thoroughly washed with potable water to remove impurities and then manually cleaned. The material was subsequently cut into standardized dimensions (3.0 cm × 2.0 cm; thickness < 0.2 cm) to ensure uniform heat and mass transfer. After cutting, the samples were stored at 4 °C to prevent enzymatic degradation and maintain consistent initial quality. The initial moisture content of peels was 72.3 ± 3.5% (wet basis).

2.2. Experimental Set-Up

According to the experimental set-up, PEF processing was used as a pretreatment of conventional air drying of orange peel waste and was compared with the untreated conventionally dried samples (nontreated samples). Additionally, the optimal PEF pretreatment conditions were selected based on maximizing the acceleration of the drying process for orange peel waste while simultaneously minimizing the energy consumption of the process. All the results obtained were mathematically described with empirical models, and the total drying time and energy savings were estimated for all studied conditions. Finally, the major quality characteristics were measured in the final dried orange peel products (untreated and PEF pretreated), including color, water activity, residual moisture, density, solubility, hygroscopicity, water and oil holding capacity. Additionally, the concentrations of their bioactive compounds, such as total phenolic compounds, total carotenoids, and antioxidant capacity, were also determined.

2.3. Pulsed Electric Field Experiment

All PEF treatments were carried out using a versatile pilot-scale PEF system (Elcrack-5 kW, DIL, Quakenbruck, Germany). The system has a batch treatment chamber (length × width × height: 10 cm × 5 cm × 8 cm) and a connected oscilloscope (Tektronix TDS 1012, Beaverton, OR, USA) for monitoring the pulses delivered in chamber. For all PEF experiments, the frequency was set at 20 Hz, and the pulse width was equal to 15 μs. The shape of the pulses was nearly rectangular. Orange peel waste was mixed with tap water (electrical conductivity: 1.1 ms/cm, solid/liquid ratio: ½ and total mass: 350 g) and treated at 1.7, 2.5 and 4.0 kV/cm electric field strengths for pulses up to 2000 ms. The selection of suitable PEF conditions was performed by estimating the cell disintegration index Z of orange peel waste. More specifically, the selected PEF conditions for the further drying experiments corresponded to three different Z values (4.0 kV/cm, 0.75 ms, Z = 0.2; 4.0 kV/cm, 2.3 ms, Z = 0.5; 4.0 kV/cm, 7.5 ms, Z = 0.8) to evaluate whether the degree of cell disintegration caused by PEF, affected the drying rate of orange peel waste. Immediately after PEF treatment, the orange peel waste was removed from tap water. The temperature of samples was recorded before and after PEF treatment by using a digital thermometer (General Tools & Instruments, Secaucus, NJ, USA), and it never exceeded 30 °C. The specific PEF energy input (WPEF) was calculated from voltage, current, pulse width, and pulse number, sample mass [22] giving values between 1.98 and 19.86 kJ/kg. All PEF treatments were repeated twice.

2.4. Determination of Cell Disintegration Index Z

The cell disruption index Z is an indicator showing the percentage of electroporated plant cells due to PEF treatment. It ranges from 0 (control sample—untreated—non-disrupted) to 1 (fully disrupted). The objective was to apply three different PEF conditions to orange peel waste with Z equal to 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, to investigate whether the intensity of the conditions (more intense condition → larger Z) could affect the acceleration of drying. The low–high-frequency method was used to estimate the Z index based on the method proposed by Andreou, Dimopoulos, Dermesonlouoglou, and Taoukis [22]. A frequency generator, Newtronics Model 200SPC Sweep/Pulse/Function-Generator (Newtronics Pty Ltd., Tullamarine, VIC, Australia), and an oscilloscope were used for Z estimation. Three electric field strengths (1.7, 2.5, and 4.0 kV/cm) were applied to orange peel waste for treatment times of up to 30 ms. Electrical conductivity was measured before and after PEF treatment at low (1 kHz) and high (1 MHz) frequencies to determine the Z-value. The cell disintegration index (Z) was then modeled mathematically using a two-parameter empirical transition function [22]:

where Z denotes the cell disintegration index, τ represents the characteristic damage time (i.e., the PEF treatment duration required to reach a cell disintegration index of 0.5), t is the applied PEF treatment time, and r is an empirical exponent.

2.5. Air-Drying Process

Untreated and PEF pretreated orange peel waste was cut into equal disks with standard dimensions (length × width: 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm and a thickness of <0.2 cm—infinite slab) and placed in three pre-weighted containers. To determine the moisture loss during drying, the racks were weighed before and during the process at predetermined times. The drying was carried out at temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C by using an air dryer (Air Dryer—Easy Dry HOTMIXPro 8 GN1/1—Vitaeco S.r.l, Modena, Italy). The velocity of air was set at 1.0 m/s for all studied conditions and ambient relative humidity [23,24,25,26]. Preliminary drying trials were also conducted to confirm that this airflow ensures stable drying conditions without causing surface hardening, which is consistent with common practice for drying sensitive plant materials such as fruits and vegetables. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.6. Mathematical Modeling of Air During Process

To evaluate the drying kinetics of orange peel, both instantaneous drying rate (DRi) and average drying rate (DRav) were calculated. The instantaneous drying rate was determined using the equation:

where and are the moisture contents (g water/g dry matter) at times and (min), respectively. The moisture content can also be expressed in dimensionless form (ω) as follows:

where ω is the dimensionless moisture ratio, Mt is the dry basis moisture content at drying time t, Mf is the dry basis moisture content at the end of drying process and M0 is the initial dry basis moisture content. Then, the drying curves were constructed for each sample at each drying temperature. Plotting DRi as a function of time (DRi = f(t)) or dimensionless moisture content (DRi = f(ω)) allows for comparison of drying behavior between different samples.

The average drying rate (DRav) over the total drying period was calculated as

where and are the initial and final moisture contents (g water/g dry matter), and and are the initial and final drying times (min), respectively. DRav provides an overall measure of the drying performance for each treatment and drying temperature.

The experimental data were described using four different empirical mathematical models, which are widely used in the literature in drying process and are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analytical description of empirical models fitted to experimental data of air drying of orange peel waste.

Newton model (Equation (5)) and Page’s empirical model (Equation (6)) are considered the most suitable and simplest mathematical models to describe the air-drying process of plant tissues and their by-products [31]. Henderson and Pabis (Equation (7)) and Weibull model (Equation (8)) were also fitted to the experimental data obtained for the air-drying experiments. Moreover, it was considered crucial to apply a diffusion model to better understand the heat and mass transfer process of air drying. Fick’s second law with boundary conditions assumes that the heat inside the product is transferred by conduction, and the water removal is transferred by diffusion. The mathematical solution to Fick’s second law (for an infinite slab) (Equation (9)) was also fitted to obtain data, describing the diffusion from orange peels and the uniform initial moisture distribution. The effective moisture diffusion coefficients were calculated based on the following:

where ω is the dimensionless moisture ratio, Deff is the effective moisture diffusion coefficient (m2/s) and l is the slab half thickness (m) that was measured using a digital micrometer (Helios, Preisser, Gammertingen, Germany) with a precision of ±0.01 mm.

The dependence of the effective moisture diffusion coefficient on the drying temperature (as calculated from Equation (9)) was described according to the Arrhenius equation (Equation (10)):

where Deff and Deffref are the effective moisture diffusion coefficients (m2/s) at T and Tref (55 °C) drying temperatures (K), respectively, Ea is the activation energy (J/mol), and R is the universal gas constant (=8.314 J/mol K).

2.7. Thermodynamic Approach of Air Drying

The major thermodynamic properties of air-drying process, such as enthalpy (Equation (11)), entropy (Equation (12)) and Gibbs free energy (Equation (13)) differences, were estimated for each sample based on the following equations:

where ΔH is the specific enthalpy difference (J/mol), ΔS is the specific entropy difference (J/mol), ΔG is the Gibbs free energy difference (J/mol), Ea is the activation energy (J/mol), T is the drying temperature (K), Deffref is the effective moisture diffusion coefficients (m2/s) at Tref (=55 °C), kb is the Boltzmann constant (=1.38 × 10−23 J/K), hp is the Planck constant (6.62 × 10−34 J/s) and R is the universal gas constant (=8.314 J/mol K).

2.8. Determination of Drying Time and Total Energy of Air Drying

The drying time and total energy consumption during air drying were determined for both untreated and PEF pretreated samples at all tested drying temperatures, to evaluate the potential energy savings achieved by applying PEF as a pretreatment for air-drying orange peel waste. The required air-drying time until the dimensionless moisture reached a value of 0.2 was calculated based on Equation (14):

where t is the required drying time (min), ω is the dimensionless moisture ratio equal to 0.2, and k is the drying rate (min−1) for each studied condition that was calculated by fitting the experimental data using Equation (3). The value of 0.2 for the dimensionless moisture ratio (ω) was selected based on preliminary drying experiments, where it was observed that at this level the drying curve reached a plateau, indicating that further moisture removal occurred at a significantly slower rate. Therefore, the value of 0.2 was considered an appropriate endpoint for the drying process evaluation.

The total energy of air drying was estimated according to Equation (15) [17]:

where W is the total drying energy (MJ/kg of wet orange peel waste), A is the area of the container where the samples were placed for drying (m2), v is the air velocity (m/s), ρair is the air density at each drying temperature and atmospheric pressure (1 atm) (kg/m), t is the drying time (min) as calculated by Equation (14) at each condition, ΔT is the temperature difference (K), cp is the air specific heat at each drying temperature at atmospheric pressure (1 atm) (kJ/(kg K)), and m is the initial mass of wet orange peel waste (kg).

2.9. Determination of Physical Properties of Dried Orange Peel Waste

The moisture content of orange peels at the beginning and at the end of drying process was assessed by subjecting them to 24 h of drying at 110 °C using a Memmert B50 type oven (Memmert GmbH + Co. KG, Schwabach, Germany). The water activity of final dried samples was also determined by using Aqua LAB 4TEV aw-meter (Decagon, Pullman, WA, USA) at a constant temperature of 25 °C. Hygroscopicity and solubility of dried samples were also determined. Based on the method proposed by Cai and Corke [32] to estimate hygroscopicity, the moisture content of each dried sample was calculated after 7 days of incubation in a container with a saturated salt (Na2SO4) solution (81% relative humidity). Hygroscopicity was expressed as g H2O/100 g of sample. According to Cano-Chauca, Stringheta, Ramos, and Cal-Vidal [33], for solubility determination, 5 g of each dried sample was mixed with 20 mL of distilled water and incubated in bath of 80 °C for 30 min in tubes. Afterwards, the tubes were centrifugated and the supernatants were dried at 105 °C for 24 h. Solubility was expressed as g/100 g of sample. The bulk density (g/mL) of the dried samples was determined according to CRA [34]. A total of 5 g of dried sample was volumetrically measured in a volumetric cylinder. The water and oil holding capacity of the dried orange peel waste was determined according to the method proposed by Beuchat [35]. In total, 1 g of each dried sample was mixed with 10 mL of deionized water or sunflower oil and stirred for 1 min. Subsequently, the mixtures were centrifuged at 2200× g for 30 min. The supernatant water or oil after centrifugation was measured. The water holding capacity was expressed as g H2O/g of sample, while the oil holding capacity was expressed as g oil/g of sample. Each measurement was carried out in triplicate. The color variations in the final dried orange peels were analyzed using the CIE Lab scale, with measurements conducted employing a colorimeter, Minolta CR-300 (Minolta Company, Chuo-Ku, Osaka, Japan). The analysis encompassed five repetitions on randomly selected slices. The parameters L* (lightness), a* (redness), and b* (yellowness) were utilized to determine the chroma and hue angle, using Equations (16) and (17), respectively:

2.10. Determination of Bioactive Compounds of Dried Orange Peel Waste

At the end of each drying process, the total phenolic compounds (mg caffeic acid/100 g d.m) and antioxidant activity (mg Trolox equivalent/100 g d.m) were determined for untreated and PEF-treated dried samples. The solid–liquid extraction method was performed using 10 mL of methanol–water mixture (80:20 v/v), mixed with 1 g of dried sample. The mixture was incubated in ultrasonic bath for 1 h. Then, the mixture was filtered and stored at −20 °C until further analysis [36]. The total phenolic compound content was determined using a spectrophotometric technique based on Folin–Ciocalteu method. For antioxidant activity of samples, the DPPH method was used based on Brand-Williams, Cuvelier and Berset [37]. Carotenoids were extracted from dried orange peel products using an organic solvent as described by Andreou et al. [22] with some modifications. Five (5) g of each sample was placed in containers and stirred with 50 mL of hexane/acetone/ethanol (v/v 50:25:25) (solid/liquid = 1:10) for 30 min at 25 °C. The extracts were centrifuged at 3000 rpm (Thermo Scientific Heraeus Megafuge 16R centrifuge, Waltham, MA, USA) for 10 min. Five mL of water was added to the samples for phase separation, from which the organic phase (upper phase—orange) was collected. The final extracts were then stored at −20 °C until further analysis. The total carotenoid content was estimated spectrophotometrically according to the method of Lichtenthaler [38]. The absorbance of the extracts was measured at 470 nm (A470), 663 nm (A663) and 647 nm (A647). The chlorophyll a, b and total carotenoid contents were calculated using the Lichtenthaler equations [38]:

All measurements were repeated twice.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

One-way or factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess statistically significant differences and interactions between untreated and PEF-treated orange peels with respect to drying rate, required drying time, and the bioactive compounds of the final dried samples. Experimental data were analyzed using Statistica 7 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Mean comparisons were performed using Duncan’s test at a 5% significance level (p ≤ 0.05). Moreover, the empirical models, such as the first-order, Page’s and the mathematical solution of Fick’s second law, were used to describe the air-drying process mathematically. Model parameters were estimated from those models by using non-linear regression. To evaluate and compare the thin-layer drying models, the coefficient of determination (R2) (Equation (21)), adjusted R2 (Equation (22)), chi-square (χ2) (Equation (23)), reduced chi-square () (Equation (24)) and root mean square error (RMSE) (Equation (25)) were calculated.

where and are the experimental and model-predicted values, respectively, is the mean experimental value, is the number of observations, and is the number of model parameters.

R2 and adjusted R2 (which accounts for the number of model parameters) indicate the goodness of fit, with values closer to 1 representing better agreement between experimental and predicted data. Chi-square (χ2) and reduced chi-square () quantify the average squared deviation, considering the degrees of freedom (n − p), with smaller values indicating improved model performance. RMSE provides the standard deviation of residuals, with smaller values reflecting better predictive accuracy. Together, these parameters allow for reliable comparison of models with different numbers of parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Pulsed Electric Fields as Pretreatment on Drying Kinetics of Orange Peel Waste

3.1.1. Determination of Cell Disintegration Index Z of Orange Peel Waste

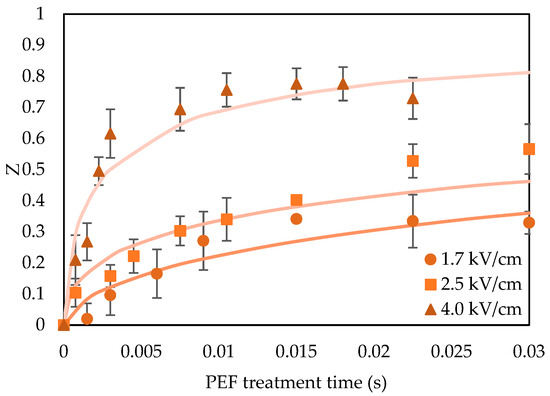

In Figure 1, the Z value of orange peels for different electric field strengths is presented, ranging from 1.7 to 4.0 and for treatment times up to 30 ms.

Figure 1.

Cell disintegration index (Z) of orange peel waste for different electric field strengths of 1.5, 2.5 and 4.0 kV/cm for treatment times up to 30 ms. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements.

The experimental data were fitted to Equation (1) for orange peel waste, which describes the dependence of Z on PEF treatment time. The model parameters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristic damage times τ (s) and empirical parameters r of PEF treated orange peel waste for electric field strengths equal to 1.7, 2.5 and 4.0 kV/cm.

3.1.2. Preliminary Drying Experiment of PEF Treated Orange Peel Waste

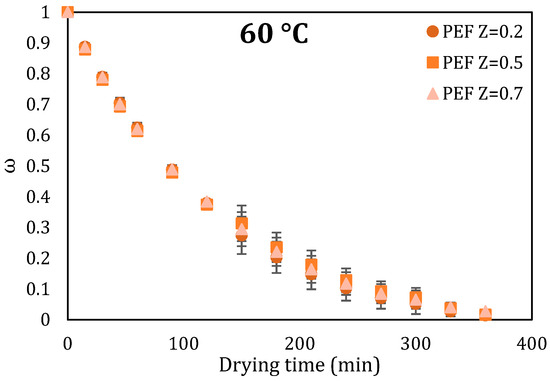

A preliminary kinetic experiment was performed to select the PEF conditions for the further drying experiments. Three different PEF conditions that correspond to three different cell disintegration indices Z were applied to orange peel waste as pretreatment, and those samples were then dried at 60 °C (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Drying curves of orange peel waste for three different cell disintegration indices (Z) for 4.0 kV/cm electric field strengths for treatment times up to 7.5 ms. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements.

3.1.3. Drying Kinetics of Orange Peel Waste

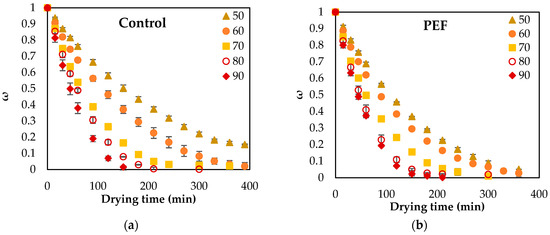

Figure 3 shows the drying curves of orange peel waste at temperatures from 50 to 90 °C for untreated and PEF pretreated samples at 4.0 kV/cm electric field strength and 50 pulses (Z = 0.2, 20 Hz, 15 μs pulse width).

Figure 3.

Drying curves of (a) untreated and (b) PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste at 50, 60, 70, 80 and 90 °C for up to 400 min. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements.

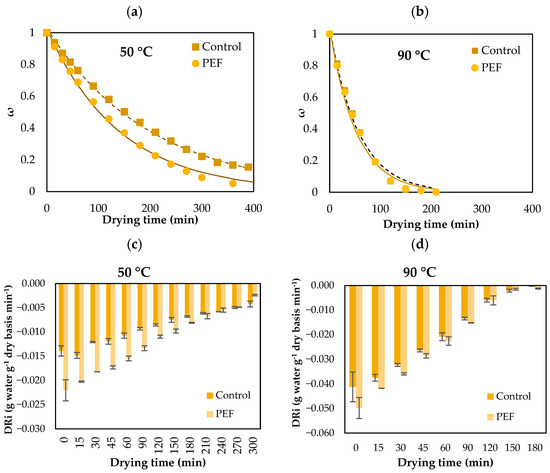

Figure 4 also shows a comparison of drying curves and instantaneous drying rate (DRi) of untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste orange peels at 50 and 90 °C. Table 3 also presents the average drying rate (DRav) of untreated and PEF pretreated orange peel waste at drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C.

Figure 4.

Drying curves of untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste at (a) 50 and (b) 90 °C for up to 400 min. Instantaneous drying rate (DRi) of untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste at (c) 50 and (d) 90 °C for up to 300 min. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements.

Table 3.

Average drying rate (DRav) untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste at drying temperatures ranging from 40 to 90 °C.

The experimental data were fitted to four different empirical models, namely, Newton, Page, Henderson and Pabis and Weibull, and their parameters are presented in Table 4. The efficiency of those models is also presented in Table 4, through several statistical parameters, such as R2, adjusted R2, chi-square (χ2), reduced chi-square () and RSME.

Table 4.

Estimated model parameters by fitting experimental data to Newton (Equation (5)), Page (Equation (6)), Henderson and Pabis (Equation (7)) και Weibull (Equation (8)) of untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperature ranging from 50 to 90 °C. Statistical parameters (R2, , RSME, , χ2) for checking the reliability of empirical models.

Fick’s model with boundary conditions also fitted to the experimental data and the effective diffusion coefficients Deff were estimated for each condition (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effective moisture diffusion coefficients Deff (m2/s) of untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C.

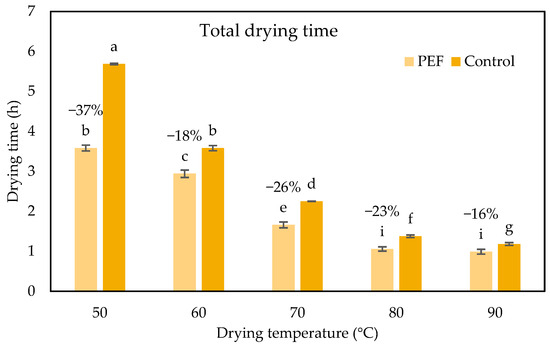

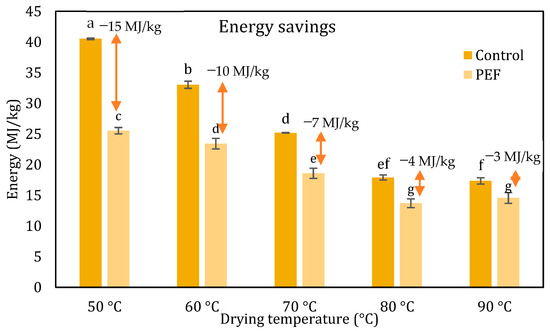

For all studied conditions, the required drying times to reach dimensionless moisture equal to 0.2 and the total drying energies were also estimated and presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6, respectively.

Figure 5.

Total drying time (h) for untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements. Different small letters indicate significantly different means (p < 0.5) between the drying times of untreated and PEF pretreated samples at each drying temperature.

Figure 6.

Total energy consumption (MJ/kg) for untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three measurements. Different small letters indicate significantly different means (p < 0.5) between the drying times of untreated and PEF pretreated samples at each drying temperature.

3.1.4. Thermodynamic Properties of Orange Peel Waste

Table 6 shows the thermodynamic properties, such as activation energy (Ea), enthalpy (∆H), entropy (∆S) and Gibbs free energy (∆G) differences in untreated and PEF pretreated (4.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C.

Table 6.

Thermodynamic properties, such as activation energy (Ea), enthalpy (∆H), entropy (∆S) and Gibbs free energy (∆G) differences in untreated and PEF pretreated (44.0 kV/cm, 50 pulses, Z = 0.2) orange peel waste for drying temperatures ranging from 50 to 90 °C.

3.1.5. Physical Properties of Final Dried Orange Peel Waste

The main physical properties of final dried orange peel waste, such as water activity, hygroscopicity, solubility, bulk density, water and oil capacity were determined and are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Physical properties, such as water activity, hygroscopicity (%), solubility (%), bulk density (g/mL), water holding capacity (mL water/g sample), oil holding capacity (mL oil/g sample) and color parameters (L*, a*, b*, chroma, hue angle) of untreated and PEF pretreated final dried orange peel waste at 50, 70 and 90 °C drying temperatures.

3.1.6. Bioactive Compounds Concentration of Final Dried Orange Peel Waste

The changes in total phenolic content (TPC), antioxidant activity (AA) and total carotenoid content (TCC) of untreated and PEF pretreated dried orange powders are demonstrated in Table 8.

Table 8.

Bioactive compounds, such as total phenolic compounds (mg Caffeic Acid/g), antioxidant activity (mg Trolox eq/g) and total carotenoids (μg/100 g) of untreated and PEF pretreated final dried orange peel waste at 50, 70 and 90 °C drying temperatures.

4. Discussion

4.1. Cell Disintegration Index Z of Orange Peel Waste

Cell disintegration index Z is considered a useful parameter for optimizing and controlling PEF processing, ensuring that a desired level of cell disintegration is achieved with the most efficient use of energy [39]. The intensity of PEF conditions (treatment time and electrical field strength) applied depends on the kind of plant tissue (cell size, electrical properties, etc.) to fully permeabilize its cell membranes [40,41]. Based on the results in Figure 1, the maximum Z value achieved after PEF treatment was 0.8. Higher Z values were achieved by increasing the treatment time at each studied electric field strength. It was observed that, at the lowest electric field strength of 1.7 kV/cm, the permeabilization phenomena of orange peels were less pronounced than at the other conditions. For treatment time higher than 7.5 ms at 4.0 kV/cm electric field strength, no further effect on the cell disintegration index Z was observed since it reached the maximum value of 0.8. In the literature, several studies have explored various Zmax values depending on the plant tissue. Andreou et al. [17,22] observed a maximum Z value of 0.5 in whole tomatoes and 0.95 in zucchini tissues, respectively. These significant differences in the electroporation effect between different plant tissues may be linked to cell size, as the cell radius is proportional to the cell disintegration index Z. Additionally, this variation could be attributed to the diverse electrical properties of material constituents, porosity, and structure, which are potential factors influencing the maximum Z values of different plant tissues [37].

The characteristic damage time, τ, serves as an indicator of how PEF treatment affects the level of electroporation in orange peel waste. The increasing influence of PEF treatment was evident in the decrease in the characteristic damage time τ, as the electric field strength increased. At electric fields of 1.7 kV/cm, the characteristic damage time τ was almost 26-fold higher than at an electric field of 4.0 kV/cm. Earlier studies have reported a wide range of characteristic damage times for different plant matrices—such as apples (0.0006–0.0040 s), carrots (0.0002–0.0008 s), and zucchinis (0.0059–0.1889 s)—under electric field strengths of 0.5 to 1.5 kV/cm [17,39,42]. Taking these observations into account, the PEF parameters chosen for the subsequent drying and extraction assays produced varying levels of cell permeabilization in the orange peel waste. Consequently, drying experiments were performed at 4.0 kV cm−1 for 0.75 ms (Z = 0.2, WPEF = 1.98 kJ/kg), 2.3 ms (Z = 0.5, WPEF = 5.95 kJ/kg) and 7.5 ms (Z = 0.8, WPEF = 19.86 kJ/kg) treatment time.

4.2. Drying of Orange Peel Waste—Selection of PEF Conditions

Based on the preliminary kinetic experiment performed, it was observed that there were no significant differences in the drying rates between the different PEF conditions (different Z values). So, for the further drying kinetic experiments, the mildest PEF condition corresponding to Z value equal to 0.2 (4.0 kV/cm, 0.75 ms, 1.98 kJ/kg) were selected.

4.3. Effect of PEF on Drying Kinetics of Orange Peel Waste

Based on the results shown in Figure 3, the duration of the air-drying process decreased as the drying temperature increased for all studied conditions. Raising the drying temperature promoted faster moisture removal from the peels by increasing the moisture gradient between the product and the surrounding air. It was also observed that PEF pretreated samples had higher drying rates at all drying temperatures, confirming the effectiveness of PEF treatment to cause electropermeabilization of cell membranes, enhancing the mass transfer phenomena. PEF exhibited a more significant influence on moisture reduction compared to untreated samples. Hence, PEF pretreatment and drying temperature positively influenced the reduction in drying time. However, at high drying temperatures, the effects of PEF-induced electroporation on plant cell membranes were largely masked by thermal plasmolysis of the tissue cells [43]. Consequently, there was no discernible positive impact of PEF treatment on the water mass transfer during drying at high temperatures (Figure 4). At each drying temperature, the instantaneous drying rate (DRi) is initially high and gradually decreases over time, as expected during the drying process. Samples pretreated with PEF exhibit higher negative drying rates (i.e., faster dehydration) compared to the untreated one, indicating an enhancement in mass transfer. The effect of PEF is more pronounced at lower temperatures (50 °C), whereas, at higher temperatures (90 °C), the differences between PEF and control are reduced, possibly due to the predominance of thermal cell disruption effects. This effect is further confirmed by the average drying rates observed at each temperature, as shown in Table 3. At all temperatures, PEF pretreated samples exhibit significantly higher drying rates compared to the untreated one, indicating that the PEF treatment effectively enhances water diffusion and accelerates dehydration. The effect of PEF is particularly pronounced at lower temperatures (50–70 °C), where the differences between control and PEF are statistically significant (p < 0.05). At higher temperatures (80–90 °C), the differences between the two samples diminish, suggesting that thermal effects dominate and partially mask the impact of PEF pretreatment. The enhanced dehydration of PEF-treated orange peels is likely due to the disintegration of cell wall biopolymers, caused by the cleavage of bonds within and between cell wall and membrane molecules [44]. The degree of such disintegration of cell walls and membranes may vary depending on the specific product. This led to an augmentation of mass transport phenomena, expediting the transfer of water from the tissue to the surface of the peels, where it could be evaporated. Consequently, the dehydration rate of orange peels post-PEF treatment was notably higher compared to other tissues studied under similar conditions [45].

Generally, all models showed good fitting to the experimental data for both samples (control and PEF pretreated). Mathematical modeling plays a crucial role in the design of the process, as it enables accurate prediction of process dynamics. A well-chosen mathematical model is instrumental for food technologists, aiding in decision making regarding optimal drying times and process optimization. Among the applicable empirical models, the Newton model is considered the simplest to describe the drying process but was found to be the least accurate (fitting R2 < 0.95 to experimental data), especially for the higher drying temperatures (>70 °C). It also became evident that the Page model fitted well the data obtained from drying kinetics of untreated and PEF-treated orange peel waste at all studied conditions. The values of R2 were higher than 0.98. The drying rate constant “kP” is considered the drying constant that describes the effective diffusivity during the drying process. Upon analyzing the data, it was observed that higher drying temperature led to higher values of drying rate constant “kP” for untreated and PEF pretreated orange peels. For PEF pretreated orange peels, the values of drying rate constant “kP” were greater than the untreated ones at each drying temperature, indicating the acceleration of the PEF-assisted drying process. Parameters “kP” for PEF pretreated samples were significantly higher for milder temperatures; while increasing the drying temperature, smaller differences appeared between the drying constants of untreated and PEF pretreated samples. More specifically, at a drying temperature of 50 °C, the parameter “kP” of the PEF-treated sample was 59% higher than the control one, whereas at 90 °C it was only 19% higher. The “n” parameter ranged from 1.06 to 1.25, increasing with temperature but without any significant differences (p > 0.05) between the two groups. Increasing drying temperature, the effect of PEF on mass transfer phenomena was considered negligible. The Page model was also fitted to the obtained data with lower chi-reduced factors than the other fitted models ( < 0.0004). That model had three estimated parameters that are shown in Table 4. The “kH” indicates the rate constant of the drying process. For PEF-treated samples, the drying rate “kH” had higher values for all studied samples compared to the respective untreated ones, with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05). The parameters «m» and «p» did not exhibit significant differences between all studied drying conditions for both the PEF-treated and untreated samples. The data were also fitted to the empirical Weibull model, and the two parameters of the model were calculated, as presented in Table 4. The parameter “a” in the Weibull model represents the slope parameter or the shape factor. The parameters “a” were significantly smaller for the PEF-treated samples compared to the corresponding reference samples at all drying temperatures. This model showed relatively good fitting to the experimental data, especially at lower drying temperatures. It is worth noting that the factor was up to 0.0272. Various empirical mathematical models, including the Page model [46], Weibull model [47,48], and Henderson and Pabis model [49,50], have been employed in the literature to characterize the drying process. Kim, Lee, Hong, Yeo, Jeong, and Lee [51] utilized PEF to accelerate the convective drying of carrots and fitted empirical models to describe the experimental data. The Page model exhibited the closest predicted values vs. actual experimental values for the drying of carrots, yielding R2 values of 0.979 and 0.999. El-Mesery and Mwithiga [52] demonstrated that the Page model effectively characterizes the convective drying of onions under isothermal conditions. Ostermeier et al. [46] also applied the Page model to predict the air drying of PEF-treated onions, concluding its effectiveness with an average R2 of 0.988.

Additionally, Fick’s second law of diffusion stands out as a widely used mathematical model [51,53,54,55]. According to various research studies in the literature related to the drying kinetics of plant tissues and their by-products, Fick’s second law provides a more realistic and physical interpretation and description of the drying operation, allowing the determination of the mass transfer phenomena by the estimation of effective diffusion coefficients, Deff. The Deff of untreated and PEF-treated samples ranged from 2.98 × 10−11 to 1.11 × 10−10 m2/s and from 4.42 × 10−11 to 1.15 × 10−10 m2/s, respectively, for all studied temperatures. It was observed that the effective diffusion coefficient of PEF pretreated samples at 50 °C was the same as that of the untreated at 60 °C. Thus, it was concluded that the application of PEF as pretreatment of orange peels resulted in the same drying rate that was achieved without pretreatment, reducing the drying temperature by 10 °C. Similar to the results of that study, Wiktor et al. [56] reported a 16.7% increase in the effective diffusivity (Deff) of PEF-treated carrot slices (5 kV/cm, 0.7 ms, 8 kJ/kg) compared to untreated samples during convective air drying at 70 °C. Pretreatment with PEF resulted in reduced drying times for all studied temperatures, consequently, in total energy needs. Specifically, a reduction in drying time by 14.5%, 12.5% and 13.8% compared to the corresponding untreated samples, at temperatures of 60, 70 and 80 °C, respectively, was observed. The most pronounced reduction in drying time was found at a temperature of 50 °C, where the reduction in drying time achieved with PEF pretreatment was approximately 37%. At 90 °C, the drying times of both samples did not differ significantly. As a result of these observations, PEF pretreatment led to energy savings equal to 10, 7 and 4 MJ/kg compared to the untreated samples at temperatures of 60, 70, and 80 °C, respectively. A remarkable energy reduction of 15 MJ/kg was achieved in the mildest drying temperature of 50 °C, when the samples were pretreated with PEF. This suggests that PEF processing may have the capacity to produce dried vegetables under gentler temperatures, potentially resulting in final products with improved nutritional quality and better overall attributes, due to the milder drying conditions, all while reducing energy consumption. Numerous studies have shown that PEF pretreatment influences the convective air-drying of fruits and vegetables. Shorstkii, Sosnin, Smetana, Toepfl, Parniakov, and Wiktor [57] studied PEF (1 kV/cm, 0.25–10 kJ/kg, 40 μs) on potatoes and observed a significant reduction in drying time up to 20% compared to the untreated ones. Ostermeier et al. [46] explored PEF-assisted drying of onions with PEF pretreatment, which reduced the drying time by 30.3% at 45 °C. In the study conducted by Wiktor et al. [56], they noted a 16.7% rise in the effective moisture diffusivity (Deff) when carrot slices were subjected to PEF treatment during convective air-drying at 70 °C. Similarly, Wiktor et al. [48] found a 12.6% decrease in drying time for apple slices treated with PEF. Furthermore, Perez-Won et al. [45] demonstrated a 34.7% reduction in drying time for red peppers treated with PEF during convective air-drying at 45 °C, coupled with a 53.3% increase in Deff. In addition, in the studies by Liu et al. [58], it was discovered that PEF pretreatment decreased carrot drying time by as much as 40% at 50 °C while maintaining the β-carotene content. Santos et al. [59] verified the efficiency of PEF (4.5 kV/cm, 70 °C drying temperature) as pretreatment in mango peels, where it was observed a maximum reduction in drying time equal to 67%. Andreou et al. [17] utilized PEF pretreatment to accelerate the drying process of zucchini while also reducing energy consumption. The most significant energy savings were noted at 40 °C, where PEF pretreatment (1.5 kV/cm, 13.5 kJ/kg) resulted in savings of 133 MJ/kg. In another study, Szadzińska, Kowalski, and Stasiak [60] observed that microwave (100 W, 10 min) and ultrasound (200 W)-assisted convective drying (55 °C, 0.4 m/s) of raspberries resulted in specific energy consumption of 96 and 173 kJ/kg, respectively, representing approximately a 55% and 20% decrease, compared to convective drying (214 kJ/kg).

4.4. Effect of PEF on Thermodynamic Properties of Orange Peel Waste

By fitting data to the Arrhenius equation, the activation energies were calculated for each sample. The activation energy represents the minimum energy required to begin the water removal process. From Table 6, it can be observed that the activation energy of PEF pretreated samples was significantly (p < 0.05) lower (30.8 kJ/mol) compared to the untreated one (35.7 kJ/mol), indicating that for untreated samples more energy is required to start the diffusion. In a study on PEF-assisted convective drying of red beetroots, Shynkaryk, Lebovka, and Vorobiev [55] observed that applying PEF at 0.4 kV/cm for 100 ms reduced the activation energy (Ea) of the effective diffusion coefficient (Deff) from 20.2 to 19.2 kJ/mol. As noted by Monteiro, Domschke, Tribuzi, Teleken, Carciofi, and Laurindo [61], variations in activation energy might be associated with the product’s structure, chemical composition, dryer specifications, and pretreatments applied. Other thermodynamic indices estimated were enthalpy (∆H), entropy (∆S) and Gibbs free energy (∆G) differences and are also presented in Table 6. Enthalpy difference represents the energy transferred to the food material, which is necessary for moisture evaporation. Due to endothermic phenomena of the drying process, the obtained enthalpy values were positive and showed a slight decrease (p > 0.05) when the drying temperature was increasing. Enthalpy differences ranged from 32.7 to 33.1 kJ/mol and from 27.8 to 28.2 kJ/mol for untreated and PEF-treated samples, respectively, indicating significant statistical differences between the two groups. These values also confirmed that untreated samples needed more energy to efficiently remove the bound water from the inlet of the samples, compared to PEF pretreated ones. The pores created on cell membranes of orange peels by PEF enhanced the water removal, and, consequently, lower energy was required for water removal during drying process. In the context of the drying process, the entropy change (ΔS) during drying reflects the degree of disorder and the mobility of water molecules within the material. ΔS values were negative, indicating that water molecules became more ordered as drying progressed. PEF pretreatment influenced ΔS by disrupting cell membranes and increasing tissue permeability, which enhanced water mobility at early drying stages and facilitated faster moisture removal. At advanced drying stages, the remaining water interacted with exposed binding sites, leading to the observed decrease in ΔS. The values of entropy change were negative (exothermic transformations) ranging from −421.4 to −420.4 and from −427.2 to −428.5 for untreated and PEF-treated samples, respectively, confirming that PEF pretreatment enhanced the water removal compared to the untreated ones. These trends are consistent with the literature reports on fruits and vegetables, where structural pretreatments affect water binding and the thermodynamic parameters of drying [62,63]. Gibbs free energy changes were also estimated and positive for all studied samples, showing the non-spontaneous character of the process.

4.5. Effect of PEF Pretreatment on Physical Properties of Final Dried Orange Peel Waste

All values of aw were lower than 0.3, indicating the storage stability of final dried samples and preventing the microorganisms’ growth. Higher drying temperatures led to lower aw for both samples in a shorter time. The higher aw observed in the PEF-treated samples is related to the structural changes caused by electroporation. PEF induces cell membrane disruption and modifies the microstructure, which affects how water is retained within the tissue. Thus, even if the total moisture content is similar between samples, in the untreated peels a larger fraction of water remains bound within intact cellular structures, whereas in the PEF-treated peels a greater proportion of water becomes unbound or more freely available, resulting in higher water activity values. In each drying temperature, PEF pretreated dried samples had significantly (p < 0.05) higher aw compared to the untreated ones. Hygroscopicity pertains to a material’s ability to absorb and retain moisture from its surroundings. Across the samples studied, hygroscopicity values were notably high, ranging from 33.4% to 41.1%. As drying temperature increased, a corresponding decrease in hygroscopicity values was observed. Due to the structural changes induced by PEF pretreatment of orange peel wastes, PEF-treated samples exhibited reduced hygroscopicity compared to untreated ones. This reduction might be attributed to soluble solids migrating to the sample’s surface during PEF-drying, forming a protective film that acts as a barrier against moisture absorption. Similarly, Lammerskitten et al. [64] found that PEF pretreatment resulted in freeze-dried apples being less hygroscopic than untreated samples, attributing this effect to improved transfer of soluble solids to the sample’s surface during drying. Additionally, according to Wei, Wang, Smith, and Jiang [65], the hygroscopicity of dehydrated mango peels is primarily influenced by their chemical composition and structural changes induced by pretreatments. Solubility stands as a crucial criterion for powdered substances, potentially impacting the reconstitution of the quality of dry powders. Values higher than 25% hold particular significance concerning the stability and acceptability of food products [66]. The influence of both PEF pretreatment and drying temperatures on the solubility of dried orange peels is presented in Table 7. The rise in drying temperature and the application of PEF exhibited a noteworthy effect on solubility (p < 0.05), yielding values ranging from 25.16% to 34.7%. PEF pretreatment yielded the highest solubility percentages across all temperatures (p < 0.05), suggesting an enhancement in the water solubility of dried orange peels. Wang, Zhou, Castagnini, Berrada, and Barba [67] attributed this phenomenon to the structural alterations induced by PEF.

Bulk density pertains to powdered materials, occupying the entirety of the container volume (known as bulk volume) in which they are situated. The desirable low bulk density of dried products, attributed to the “puffing” effect, is primarily sought to enhance sensory attributes, thereby fostering greater consumer acceptance. Various factors influence the bulk density of dried products, with the drying method and its parameters ranking among the most significant, alongside porosity [68]. The decrease in bulk density with rising temperature or using PEF pretreatment can be attributed to a more rapid evaporation rate, resulting in a more porous and fragmented structure of the food material. Additionally, PEF pretreatment contributes to the formation of a glassy structure in food powders, enhancing the development of more porous powders. Bulk density values for PEF pretreated samples were doubled (0.66–0.71 g/mL), compared to the untreated ones (0.33–0.36 g/mL). The PEF-treated samples exhibited the highest bulk density at the highest drying temperature of 90 °C (0.76 g/mL), whereas the lowest bulk density was observed in orange peel powders dried via air drying at 50 °C (0.33 g/mL). Comparable findings regarding bulk density were reported by İzli et al. [68], who observed that combining microwave with convective drying in pumpkin powders resulted in higher bulk densities (0.76 g/mL), compared to untreated samples (0.33 g/mL).

Water and oil holding capacities were determined and are presented in Table 7 for all analyzed samples. The water holding capacity (WHC) exhibited a decreasing trend with increasing drying temperatures. Specifically, at the highest temperature of 90 °C, orange peel powders without PEF pretreatment displayed the lowest WHC (4.38 g/g), whereas, at the lowest temperature of 50 °C, they exhibited the highest WHC (5.18 g/g). PEF pretreatment led to an increase in WHC at all studied drying temperatures ranging from 4.79 to 5.59 g/g compared to the untreated ones. Additionally, the results indicated that increasing the drying temperature is accompanied by decreases in the oil holding capacity (OHC) of the resulting orange peel powders. Specifically, untreated orange peel powders dried at 50 °C exhibited the highest OHC (3.78 mL oil/g) compared to PEF-treated samples, which demonstrated significantly lower OWCs at the respective drying temperatures (2.12–2.22 mL/g). The significant reduction in OHC and the increase in WHC observed after PEF pretreatment were mainly attributed to the electroporation-induced structural modifications, which increased cell permeability and promoted the release of soluble intracellular components. The formation of microscopic pores due to PEF treatment increases the ability of the tissue matrix to absorb and retain water, resulting in higher WHC. This occurs because the disrupted cell walls allow water to penetrate more easily into the intracellular spaces. Moreover, the structural matrix became less capable of retaining lipids. The release of intracellular components and the loss of structural integrity create a more open and less hydrophobic matrix, which is less effective at binding oil. These effects, however, do not necessarily limit the potential applications of the treated material. For food formulations where low lipid retention is desirable—such as low-fat bakery products, beverages, or functional powders, the reduced OHC may even be advantageous. Conversely, for applications where high OHC is required, such as fat mimetics or emulsified systems, untreated orange peel or alternative pretreatments may be more suitable. Therefore, the impact of PEF on OHC should be considered application-dependent rather than inherently negative.

Drying alters the color of food products, a transformation pivotal in assessing both raw and dried plant tissue quality. This change in color holds significant importance as it directly influences acceptability and decision making, emphasizing the critical role of external appearance in product perception. Chroma ranged from 24.33 to 50.15 and from 4.43 to 16.72 for untreated and PEF-treated samples, indicating a browner color with lower brightness when drying took place at high temperatures with PEF pretreatment. There was a significant disparity in hue angles between the two groups. The PEF-treated dried powders exhibited lower lightness and a more pronounced browning effect, as reflected in hue angle values ranging from 27.92 to −41.30, whereas the untreated samples ranged from 43.57 to 65.38 in hue angle values. Firstly, the degradation of pigments due to heat treatment and enzymatic or non-enzymatic (Maillard) browning reactions [67] plays a significant role. Additionally, the PEF pretreatment, which extracts sugars and enzymes on the surface of orange peels, accelerates the Maillard reactions during the drying process, leading to increased browning. The observed browning has been linked in the literature to PEF-induced structural changes that enhance the interaction of reactive components [69]. Studies in the literature have indicated that longer drying times and higher temperatures result in more pigment deterioration and greater changes in food colors [70]. Wiktor et al. [56] observed significant reduction in chroma values for PEF (5 kV/cm, 8 kJ/kg) pretreated dried carrots compared to their counterparts. Alam, Lyng, Frontuto, Marra, and Cinquain [71] showed that PEF-treated carrots exhibited a significant decrease in lightness (L*), whereas PEF-treated parsnips showed an increase in redness (a*). This reflects the variable impact of electroporation on pigment exposure and Maillard reactions, demonstrating that PEF-induced cellular disruption can either darken or intensify color depending on tissue composition and the types of pigments present.

4.6. Effect of PEF Pretreatment on Bioactive Compound Concentration of Final Dried Orange Peel Waste

TPC appeared to be heat-resistant (with only a moderate decrease of up to 10% observed when the drying temperature increased from 50 °C to 90 °C) and exhibited significantly (p < 0.05) higher values for PEF pretreated samples at the respective drying temperatures due to the shorter drying time. Additionally, PEF pretreatment positively influenced the total phenolic content (TPC), likely due to electroporation increasing cell membrane permeability and thereby enhancing extractability. Lammerskitten et al. [64] reported up to a 47% increase in TPC for PEF pretreated freeze-dried apple tissue compared to untreated samples. Similarly, Mello, Fontana, Mulet, Correa, and Cárcel [72] found that PEF pretreatment (1.20 kV/cm, 0.37 kJ/kg) prior to drying improved the retention of both total polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity in dried orange peels.

The TCC in the dried orange peel waste was affected by the drying temperature. Increasing drying temperature led to a decrease in TCC for both samples. The use of PEF pretreatment caused a decrease in TCC compared to the control samples. PEF induces electroporation of cell membranes, which can lead to the release of intracellular compounds, including carotenoids, making them more susceptible to oxidation during subsequent drying. In addition, the PEF-enhanced mass transfer and the increased exposure of carotenoids to oxygen and heat during drying can further accelerate their degradation. Previous studies on plant materials have also reported that PEF pretreatment may cause partial degradation of sensitive bioactive compounds due to increased accessibility and interaction with pro-oxidant conditions. In the study by Fratianni, Niro, Messia, Panfili, Marra, and Cinquanta [73] on carrot and parsnip slices, PEF pretreatment (0.9 kV/cm, 1000 and 10,000 pulses) similarly led to a reduction in carotenoid concentration (up to 30%), despite shortening the drying time. Similarly, Kumar, Bawa, Kathiravan and Nadanasabapathi [74] observed that after PEF treatments (70–120 Hz, 15–24 ms pulse width, 38 kV/cm) in mango nectar led to significant carotene degradation. Ciurzynska, Trusinska, Rybak, Wiktor, and Nowacka [75] showed that PEF pretreatment (1 and 3 kJ/kg) influenced the degradation of bioactive compounds, such as polyphenols, flavonoids, and ascorbic acid in apple tissues. The carotenoid retention after PEF pretreatment yielded the maximum value for 1 kJ/kg and minimum for 3 kJ/kg. No significant differences (p > 0.05) on AA were observed among all samples studied. This suggests that, although PEF pretreatment induced structural changes and enhanced mass transfer during drying, these effects did not lead to measurable losses or gains in antioxidant compounds under the studied conditions. The results indicate that the bioactive compounds responsible for antioxidant activity in orange peel were largely stable during both PEF pretreatment and subsequent drying, highlighting the suitability of PEF as a mild pretreatment that accelerates drying without compromising the antioxidant capacity of the material. Lammerskitten et al. [64] also showed that, for freeze-dried apple tissue, PEF pretreatment decreased antioxidant activity up to 60% compared to the untreated one. Nevertheless, a different effect of PEF pretreatment on the antioxidant properties of dried apricots was shown by Huang, Feng, Aila, Hou, Carne, and Bekhit [76], improving their antioxidant capacity. Liu, Oey, Leong, Kam, Kantono, and Hamid [77] also observed an increase in AA and TPC of dried apricots after PEF pretreatment (0.7–1.8 kV/cm, 50 Hz, 20 μs pulse width). In contrast to our findings, PEF pretreatment did not significantly affect the AA of the dried orange peel waste, as stated by Neri et al. [78], who studied the saffron stigmas and reported a negative impact of PEF (2 kV/cm; 1.5 KJ kg−1) on the initial antioxidant activity, although it enhanced extractability during drying, highlighting that the effect of PEF on bioactive compounds can be highly dependent on the type of plant material and its cellular structure.

5. Conclusions

In summary, PEF pretreatment of orange peel waste before drying was proven to be a very effective method, which may improve the economic efficiency of the drying process, reducing the drying time or temperature and therefore the total drying energy. Specific PEF conditions (4.0 kV/cm, 0.75 ms, 1.98 kJ/kg) can lead to an acceleration of the drying of orange peel by-products by up to 37% compared to the control sample, saving up to 15 MJ/kg energy, which is highly advantageous for industrial-scale processing. The Page and diffusion model (Fick’s law) fit showed high coefficients of determination. Nevertheless, the diffusion model provided a more accurate representation of the drying kinetics. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that the process was endothermic and non-spontaneous, also confirming from enthalpy differences values that untreated samples needed more energy to efficiently remove the bound water from the inlet of samples compared to PEF pretreated ones. In addition, electroporation caused by PEF treatment led to an increase in the TPC in dried material, compared to the control ones. PEF pretreatment also had no significant effect on the antioxidant activity of the dried samples. As a result, the quality of the final dried product remains high, making it suitable for incorporation into value-added applications. The use of PEF-treated peel can therefore support the development of functional food ingredients and nutraceuticals.

Overall, PEF represents a technologically feasible and environmentally beneficial strategy for valorizing orange peel waste and contributing to circular-economy goals. Compared to conventional drying methods, PEF at selected conditions (1.98 kJ/kg) followed by hot air drying at a mild temperature of 50 °C produced a high-quality product in a shorter drying time, offering a more efficient and sustainable approach to managing citrus-processing waste. Furthermore, the PEF process is compatible with large-scale integration into existing industrial lines, enhancing its practical applicability. These findings are valuable for the industry, highlighting the potential of nonthermal technologies to efficiently process food waste during drying. Future research could explore the quality assessment of such products and optimize key quality parameters. These findings suggest that PEF pretreatment conditions should be carefully optimized to prevent “over-treatment,” which could lead to degradation of the bioactive compounds. Future studies should also investigate additional emerging technologies, such as ultrasound and high-pressure processing, as alternative pretreatments to PEF. A comparative assessment of these methods could further clarify their potential benefits for enhancing mass transfer and improving drying efficiency and product quality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.K.; methodology, V.A. and M.G. (Marianna Giannoglou); software, V.A. and A.N.; validation, A.N., P.K.M. and V.A.; formal analysis, V.A. and M.G. (Marianna Giannoglou); investigation, A.N., P.K.M. and V.A.; resources, G.K.; data curation, A.N., P.K.M. and V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.; writing—review and editing, P.T., M.G. (Maria Giannakourou) and G.K.; visualization, P.T., M.G. (Maria Giannakourou) and G.K.; supervision, P.T. and M.G. (Maria Giannakourou); project administration, G.K.; funding acquisition, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call Greece 2.0 (project code: ΤAEDK-06176).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support provided by the laboratory staff and express their gratitude to the Institute of Technology of Agricultural Products ELGO DEMETER for providing research facilities and resources essential for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Garcia-Perez, J.V.; Ortuño, C.; Puig, A.; Carcel, J.A.; Perez-Munuera, I. Enhancement of water transport and microstructural changes induced by high-intensity ultrasound application on orange peel drying. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 2256–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, F.R.; Soler-Rivas, C.; Benavente-García, O.; Castillo, J.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A. By-products from different citrus processes as a source of customized functional fibres. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Xia, S.; Jia, C.; Zhong, F. Liberation and separation of phenolic compounds from citrus mandarin peels by microwave heating and its effect on antioxidant activity. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 73, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obafaye, R.O.; Omoba, O.S. Orange peel flour: A potential source of antioxidant and dietary fiber in pearl-millet biscuit. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, B.; Flotats, X.J. Citrus essential oils and their influence on the anaerobic digestion process: An overview. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 2063–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezzadori, K.; Benedetti, S.; Amante, E.R. Proposals for the residues recovery: Orange waste as raw material for new products. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem Romdhane, N.; Bonazzi, C.; Kechaou, N.; Mihoubi, N.B. Effect of air-drying temperature on kinetics of quality attributes of lemon (Citrus limon cv. lunari) peels. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 1581–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.K.; Prasad, S. Drying kinetics and rehydration characteristics of microwave-vacuum and convective hot-air dried mushrooms. J. Food Eng. 2007, 78, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisth, T.; Singh, R.K.; Pegg, R.B. Effects of drying on the phenolics content and antioxidant activity of muscadine pomace. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 44, 1649–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figiel, A. Drying kinetics and quality of beetroots dehydrated by combination of convective and vacuum-microwave methods. J. Food Eng. 2010, 98, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talens, C.; Arboleya, J.C.; Castro-Giraldez, M.; Fito, P.J. Effect of microwave power coupled with hot air drying on process efficiency and physico-chemical properties of a new dietary fibre ingredient obtained from orange peel. LWT 2017, 77, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therdthai, N.; Zhou, W. Characterization of microwave vacuum drying and hot air drying of mint leaves (Mentha cordifolia Opiz ex Fresen). J. Food Eng. 2009, 91, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepfl, S.; Knorr, D. Pulsed electric fields as a pretreatment technique in drying processes. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2006, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, N.K.; Nayak, C.A.; Raghavarao, K.S.M.S. Influence of osmotic pre-treatments on rehydration characteristics of carrots. J. Food Eng. 2004, 65, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ade-Omowaye, B.I.O.; Rastogi, N.K.; Angersbach, A.; Knorr, D. Combined effects of pulsed electric field pre-treatment and partial osmotic dehydration on air drying behaviour of red bell pepper. J. Food Eng. 2003, 60, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, K.A.; Angersbach, A.; Knorr, D. Influence of high intensity electric field pulses and osmotic dehydration on the rehydration characteristics of apple slices at different temperatures. J. Food Eng. 2002, 52, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Tsonas, T.; Katsimichas, A.; Limnaios, A.; Katsaros, G.; Taoukis, P. Pulsed electric fields-assisted drying and frying of fresh zucchini. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 2091–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, R.B.; Combarnous, M. Study of orange peels dryings kinetics and development of a solar dryer by forced convection. Sol. Energy 2011, 85, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Karaaslan, S.; Öztekin, S.; Şahan, Z.; Çiftçi, H. Microwave drying of orange peels and its mathematical models. Tarım Makinaları Bilim. Derg. 2014, 10, 329–333. [Google Scholar]

- Phuon, V.; Ramos, I.N.; Brandão, T.R.; Silva, C.L. Assessment of the impact of drying processes on orange peel quality characteristics. J. Food Process Eng. 2022, 45, e13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, M.C.; Simal, S.; Rossello, C.; Femenia, A. Effect of air-drying temperature on physico-chemical properties of dietary fibre and antioxidant capacity of orange (Citrus aurantium v. Canoneta) by-products. Food Chem. 2007, 104, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Dimopoulos, G.; Dermesonlouoglou, E.; Taoukis, P. Application of pulsed electric fields to improve product yield and waste valorization in industrial tomato processing. J. Food Eng. 2020, 270, 109778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velić, D.; Planinić, M.; Tomas, S.; Bilić, M. Influence of airflow velocity on kinetics of convection apple drying. J. Food Eng. 2004, 64, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sarkar, B.C.; Sharma, H.K. Effect of air velocity on kinetics of thin layer carrot pomace drying. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2011, 17, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santacatalina, J.V.; Soriano, J.R.; Cárcel, J.A.; Garcia-Perez, J.V. Influence of air velocity and temperature on ultrasonically assisted low temperature drying of eggplant. Food Bioprod. Process. 2016, 100, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankhade, P.K.; Sapkal, R.S.; Sapkal, V.S. Drying characteristics of okra slices on drying in hot air dryer. Procedia Eng. 2013, 51, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.K. The rate of drying of solid materials. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1921, 13, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, G.E. Factors Influencing the Maximum Rates of Air Drying Shelled Corn in Thin Layers; Purdue University: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, S.M.; Pabis, S. Grain drying theory. 1. Temperature effect on drying coefficient. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1961, 6, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Babalis, S.J.; Papanicolaou, E.; Kyriakis, N.; Belessiotis, V.G. Evaluation of thin-layer drying models for describing drying kinetics of figs (Ficus carica). J. Food Eng. 2006, 75, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwude, D.I.; Hashim, N.; Janius, R.B.; Nawi, N.M.; Abdan, K. Modeling the thin-layer drying of fruits and vegetables: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 599–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.Z.; Corke, H. Production and properties of spray-dried Amaranthus betacyanin pigments. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 1248–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Chauca, M.; Stringheta, P.C.; Ramos, A.M.; Cal-Vidal, J. Effect of the carriers on the microstructure of mango powder obtained by spray drying and its functional characterization. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2005, 6, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRA. Bulk density (B-16). In Analytical Methods of the Member Companies of the Corn Refiners Association; CRA: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Beuchat, L.R. Functional and electrophoretic characteristics of succinylated peanut flour protein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1977, 25, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, V.; Psarianos, M.; Dimopoulos, G.; Tsimogiannis, D.; Taoukis, P. Effect of pulsed electric fields and high pressure on improved recovery of high-added-value compounds from olive pomace. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 1500–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987; Volume 148, pp. 350–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lebovka, N.I.; Bazhal, M.I.; Vorobiev, E. Estimation of characteristic damage time of food materials in pulsed-electric fields. J. Food Eng. 2002, 54, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataro, G.; Ferrari, G.; Donsì, F. Mass transfer enhancement by means of electroporation. Mass Transf. Chem. Eng. Process. 2011, 8, 151–176. [Google Scholar]

- Vorobiev, E.; Lebovka, N.I. Extraction of intercellular components by pulsed electric fields. In Pulsed Electric Fields Technology for the Food Industry: Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 153–193. [Google Scholar]

- Angersbach, A.; Heinz, V.; Knorr, D. Effects of pulsed electric fields on cell membranes in real food systems. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2000, 1, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parniakov, O.; Bals, O.; Lebovka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Pulsed electric field assisted vacuum freeze-drying of apple tissue. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 35, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignat, A.; Manzocco, L.; Brunton, N.P.; Nicoli, M.C.; Lyng, J.G. The effect of pulsed electric field pre-treatments prior to deep-fat frying on quality aspects of potato fries. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2015, 29, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Won, M.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Tabilo-Munizaga, G.; Pizarro, S.; Noma, S.; Igura, N.; Shimoda, M. Modelling of red abalone (Haliotis rufescens) slices drying process: Effect of osmotic dehydration under high pressure as a pretreatment. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 34, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostermeier, R.; Giersemehl, P.; Siemer, C.; Töpfl, S.; Jäger, H. Influence of pulsed electric field (PEF) pre-treatment on the convective drying kinetics of onions. J. Food Eng. 2018, 237, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jin, T.Z.; Xiao, G. Effects of pulsed electric fields pretreatment and drying method on drying characteristics and nutritive quality of blueberries. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 41, e13303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, A.; Iwaniuk, M.; Śledź, M.; Nowacka, M.; Chudoba, T.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Drying kinetics of apple tissue treated by pulsed electric field. Dry. Technol. 2013, 31, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gálvez, A.L.M.S.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Bilbao-Sáinz, C.; Fito, P.; Andrés, A. Effect of air drying temperature on the quality of rehydrated dried red bell pepper (var. Lamuyo). J. Food Eng. 2008, 85, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti-Mata, M.E.R.M.; Duarte, M.E.M.; Lira, V.V.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Costa, N.L.; Oliveira, H.M.L. A new approach to the traditional drying models for the thin-layer drying kinetics of chickpeas. J. Food Process Eng. 2020, 43, e13569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Lee, B.M.; Hong, S.Y.; Yeo, H.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, D.U. A pulsed electric field accelerates the mass transfer during the convective drying of carrots: Drying and rehydration kinetics, texture, and carotenoid content. Foods 2023, 12, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Mesery, H.S.; Mwithiga, G. The drying of onion slices in two types of hot-air convective dryers. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 7, 4284–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.C.; Yano, H.; Teng, K.K.; Chao, M.V. A unique pathway for sustained neurotrophin signaling through an ankyrin-rich membrane-spanning protein. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 2358–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, A.; Siddeeg, A.; Manzoor, M.F.; Zeng, X.A.; Ali, S.; Baloch, Z.; Wen, Q.H. Impact of pulsed electric field treatment on drying kinetics, mass transfer, colour parameters and microstructure of plum. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2670–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shynkaryk, M.V.; Lebovka, N.I.; Vorobiev, E.J.D.T. Pulsed electric fields and temperature effects on drying and rehydration of red beetroots. Dry. Technol. 2008, 26, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, A.; Nowacka, M.; Dadan, M.; Rybak, K.; Lojkowski, W.; Chudoba, T.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. The effect of pulsed electric field on drying kinetics, color, and microstructure of carrot. Dry. Technol. 2016, 34, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorstkii, I.; Sosnin, M.; Smetana, S.; Toepfl, S.; Parniakov, O.; Wiktor, A. Correlation of the cell disintegration index with Luikov’s heat and mass transfer parameters for drying of pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreated plant materials. J. Food Eng. 2022, 316, 110822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yu, Q.; Huang, H.; Hou, K.; Dong, R.; Chen, Y.; Xie, M. The effect of bound polyphenols on the fermentation and antioxidant properties of carrot dietary fiber in vivo and in vitro. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, N.C.; Almeida, R.L.J.; Brito, A.C.D.O.; Silva, V.M.D.A.; Albuquerque, J.C.; Saraiva, M.M.T.; Mota, M.M.D.A. Effect of pulse electric field (PEF) intensity combined with drying temperature on mass transfer, functional properties, and in vitro digestibility of dehydrated mango peels. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 5219–5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadzińska, J.; Kowalski, S.J.; Stasiak, M. Microwave and ultrasound enhancement of convective drying of strawberries: Experimental and modeling efficiency. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 103, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, R.L.; Domschke, N.N.; Tribuzi, G.; Teleken, J.T.; Carciofi, B.A.; Laurindo, J.B. Producing crispy chickpea snacks by air, freeze, and microwave multi-flash drying. LWT 2021, 140, 110781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viganó, J.; Azuara, E.; Telis, V.R.; Beristain, C.I.; Jiménez, M.; Telis-Romero, J. Role of enthalpy and entropy in moisture sorption behavior of pineapple pulp powder produced by different drying methods. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 528, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R.L.J.; Santos, N.C.; Alves, I.L.; André, A.M.M. Evaluation of thermodynamic properties and antioxidant activities of Achachairu (Garcinia humilis) peels under drying process. Flavour Fragr. J. 2021, 36, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]