Abstract

Because of the advancement of IT, cross-domain environments have emerged where independent clouds with different security policies share data. However, sharing data between clouds with heterogeneous security levels is a challenging task, and most existing access control schemes focus on a single cloud domain. Among various access control models, RBAC is suitable for cross-domain data sharing, but existing RBAC schemes cannot provide strong role privacy and do not support freshness in role verification, so they are vulnerable to replay-based misuse of credentials. In this paper, we propose an RBAC scheme for cross-domain cloud environments based on a hash-chain-augmented zk-SNARK and identity-based signatures. The TA issues IBS-based role signing keys to users, and the user proves, through a zk-SNARK circuit, that there exists a valid role signing key satisfying the access policy without revealing the concrete role information to the CDS. In addition, a synchronized hash chain between the user and the CDS is embedded into the proof so that each proof is tied to the current hash-chain state and any previously used proof fails verification when replayed. We formalize role privacy, replay resistance, and MitM resistance in the cross-domain setting and analyze the proposed scheme by comparing it with Saxena and Alam’s I-RBAC, Xu et al.’s RBAC, MO-RBE, and PE-RBAC. The security analysis shows that the proposed scheme achieves robust role privacy against both the CDS and external attackers and prevents replay and man-in-the-middle attacks. Furthermore, the computational cost evaluation based on the number of pairing, exponentiation, point addition, and hash operations confirms that the verifier-side overhead remains comparable to existing schemes, while the additional prover cost is the price for achieving stronger privacy and security. Therefore, the proposed scheme can be applied to cross-domain cloud systems that require secure and privacy-preserving role verification, such as military, healthcare, and government cloud infrastructures.

1. Introduction

The recent cloud is evolving into a collaborative environment between clouds [1,2,3,4]. In this way, data sharing between different clouds is called cross-domain. For example, this includes data sharing between independent corporate clouds or between isolated military networks [5,6,7,8]. Here, a domain refers to an isolated system that is governed by its own security policy and administrator.

The cross-domain cloud environment consists of a high-security domain and a low-security domain based on relative security level [9]. Because of these security levels, the cross-domain cloud environment can lead to a variety of security problems, such as integrity violations of the high-security domain and sensitive information leakage to the low-security domain [10,11,12]. In particular, the cross-domain environment has a limitation that cannot provide uniform access control because of different security levels. Also, each domain has an independent authentication and authorization system to manage users. Therefore, even if a user has valid permissions in one domain, those permissions cannot be trusted in another domain.

However, despite the growing demand for secure inter-domain interaction, existing access control research mainly focuses on a single cloud environment and does not consider the unique constraints of a setting where domains do not inherently trust each other. In particular, there is currently no RBAC model that supports secure cross-domain operation while preserving user role privacy and preventing credential misuse such as replay attacks. As a result, there is a need for a cross-domain access control scheme that ensures security and preserves user privacy, especially in environments such as military and healthcare systems where the exposure of role information itself can lead to serious security problems.

To solve these problems, various access control schemes such as DAC (Discretionary Access Control), MAC (Mandatory Access Control), RBAC (Role-Based Access Control), and ABAC (Attribute-Based Access Control) can be used in the cross-domain environment. If an access control scheme is applied in the cross-domain cloud environment, it can ensure safety and trustworthiness because the user receives the minimum necessary authority.

Among them, the RBAC manages permissions by granting a role to users. So, it is suitable for a large cloud structure and can provide high scalability [13,14]. The recent RBAC research is being conducted to apply to various IT environments. Yet existing research only considers a single cloud environment. So, there is a lack of research considering the cross-domain cloud environment. As mentioned above, the importance of the cross-domain cloud environment is growing. So, a study considering the cross-domain environment is needed.

Existing RBAC schemes prove the role directly or indirectly. Yet it will make a problem in some environments, such as military and medical environments, if the role name is exposed [15,16]. If the user’s role name that collects information in the military is exposed, the attacker can select the user as an attack target. Also, if a user’s role name, such as “doctor” or “IT administrator”, is exposed, the attacker can also select the user as an attack target.

To prevent role name leakage, zk-SNARK can be applied in RBAC. However, existing zk-SNARK schemes cannot prevent a replay attack. Therefore, if an attacker obtains a valid proof, the attacker can also pass authentication using the previously obtained proof.

To address these limitations, this paper presents a zk-SNARK-based RBAC scheme designed for the cross-domain cloud. The proposed scheme integrates a hash-chain mechanism with zk-SNARK to provide role privacy while preventing replay attacks in verifier interactions. Through this, the proposed cross-domain RBAC scheme can perform more secure access control than existing RBAC schemes. The contributions of this paper are as follows:

- Provide the robust role privacy based on zk-SNARK: Existing RBAC research, especially I-RBAC (Identity-Based RBAC), has a problem that exposes the user’s role because it does not provide role privacy. There is a study that provides role privacy in normal RBAC, but it also exposes role intersection to the verifier. In this paper, we integrate zk-SNARK (Zero-Knowledge Succinct Non-interactive ARgument of Knowledge) with a hash chain and apply it in cross-domain RBAC when proving a user’s role. So, the verifier cannot know the role intersection between the user and the verifier. Through this, the proposed cross-domain RBAC can provide robust role privacy.

- Improved zk-SNARK to prevent replay attack: Existing zk-SNARK schemes cannot prevent replay attacks because they consider only a stateless verifier. Because of this, the attacker can pass authentication using previously obtained proofs. In this paper, we improve zk-SNARK using the hash chain. The prover and the verifier share the same hash chain value and use it when the prover proves their role with zk-SNARK. Through this, the proposed RBAC scheme can prevent replay attacks.

- Proposed RBAC customized for cross-domain environment: Existing RBAC research only considers a single domain, so there is a lack of research considering the cross-domain environment. This paper proposes a new cross-domain RBAC that enables interactions between different domains while maintaining an air gap. Each domain does not trust another domain’s request or data. So, if a CDS (Cross-Domain Solution) receives the request or the data, it always verifies its validity.

This paper focuses on satisfying cryptographic requirements in a cross-domain cloud. Therefore, the implementation of a real cross-domain cloud and the evaluation of the proposed scheme in a real cross-domain cloud will be performed in future work.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 describes the underlying technology of the proposed RBAC scheme, and Section 3 describes the basic research on zk-SNARK proposed in this paper and existing RBAC research. Section 4 proposes the proposed RBAC scheme, and Section 5 analyzes existing RBAC schemes and the proposed scheme. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Background

In this section, we introduce some cryptographic primitives to understand the proposed scheme.

2.1. Bilinear Pairing

Bilinear pairing is a special mathematical operation in ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), which outputs elements of a finite field that receive points on two elliptic curves as input [17]. Bilinear pairing is defined by selecting abelian additive groups and multiplicative group on the elliptic curve such that . Also, a bilinear pairing satisfies three properties.

- Bilinearity: .

- Non-degeneracy: When , .

- Computability: When , can be computed in polynomial time.

2.2. Identity-Based Cryptography

Existing I-RBAC research combines RBAC with IBC (Identity-Based Cryptography) to solve the public key management problem and improve the flexibility and scalability of access control. IBE (Identity-based Encryption) and IBS (Identity based Signature) use the user’s identity with a public key [18,19]. So, it can encrypt and verify the signature without a separate public key. The following processes describe the IBE and IBS procedures based on ECC.

2.2.1. Identity-Based Encryption

The process of IBE is as follows.

- Step 1.

- A trusted authority () initializes a bilinear group system as follows. and are two distinct elliptic curve groups, and is a multiplicative group. A bilinear map is defined. A large prime q is also chosen.

- Step 2.

- A generator is selected. The master secret key and the corresponding master public key are generated.

- Step 3.

- Hash functions and are defined. The public parameters are published.

- Step 4.

- For a user’s identity , the TA computes , and the private key and securely delivered to the user.

- Step 5.

- The sender computes the receiver’s and selects a random value . Then, is computed.

- Step 6.

- For a message M, the sender computes and constructs the ciphertext to be sent to the receiver.

- Step 7.

- The receiver decrypts the ciphertext by computing .

2.2.2. Identity Based Signature

The process of IBS is as follows.

- Step 1.

- A trusted authority () initializes a bilinear group system as follows. and are two distinct elliptic curve groups, and is a multiplicative group. A bilinear map is defined. A large prime q is also chosen.

- Step 2.

- A generator is selected. The master secret key and the corresponding master public key are generated.

- Step 3.

- Hash functions and are defined. The public parameters are published.

- Step 4.

- For an identity string , the TA first computes . Then, it derives the corresponding signing key and sends it to the user through a secure channel.

- Step 5.

- To sign a message M, the signer selects a random value and computes .

- Step 6.

- The signer then computes and , and generates the signature .

- Step 7.

- The verifier computes and .

- Step 8.

- The verifier checks the validity of the signature by verifying whether .

2.3. Hash Chain

The hash chain is a hash value obtained by applying a hash algorithm to the seed value continuously. In general, the seed is a private value, and the hash value is public. The hash chain can be defined like below.

The hash chain has security attributes:

- The hash chain is based on a one-way hash function with collision resistance. Once a value has been revealed, moving backwards to an earlier value is not feasible, and the chain must preserve this property.

- The last element of the chain is published first. The rest of the values are released step by step, depending on when the protocol requires the next value in the sequence.

- A disclosed value is verified by recomputing the remaining hash evaluations until reaching the public reference. If the final result does not match, the verifier rejects it.

- The initial seed is chosen from a large random space. If the seed can be predicted or reconstructed, the chain loses security, so high entropy is required.

The seed is transmitted from TA (trusted authority) to the user on a secure channel. Also, if the hash chain has expired, the last hash value will be the seed in the next hash chain.

3. Technical Foundation for Cross-Domain RBAC

In this section, we present the technical foundation of the proposed cross-domain RBAC scheme. First, we review zk-SNARK and related schemes that motivate our hash-chain-augmented construction. Next, we introduce the hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK protocol that is used as the core building block for role proof in our RBAC design. Finally, we summarize existing RBAC schemes that are closely related to our work and discuss their limitations. These foundations are used directly in the protocol description in Section 4 and in the security analysis in Section 5.

3.1. zk-SNARK

zk-SNARK is a ZKP scheme that allows a prover to convince a verifier that a statement is true without revealing the witness. A zk-SNARK satisfies the following properties.

- Zero-knowledge: The proof does not reveal any information other than the fact that the prover knows a valid witness for the statement.

- Succinctness: The proof size is small, and the verification time is short, regardless of the original computational complexity of the statement.

- Non-interactive: The verification is completed by checking a single proof message generated by the prover, without interaction between the prover and the verifier. This is possible through an initial setting called the CRS (Common Reference String).

- Argument of knowledge: A malicious prover cannot generate a valid proof without a valid witness in a computational sense. In other words, generating a valid proof assures that the prover knows a valid witness.

To achieve these properties, modern zk-SNARK schemes use pairing-based cryptography and the QAP (Quadratic Arithmetic Program) framework. They express the computation process as a circuit and convert it into polynomial relations, which enables concise and efficient proof generation and verification.

3.1.1. Related Works on zk-SNARK

Parno et al. proposed Pinocchio and advanced the theory of zk-SNARK into an implementable system [20]. Pinocchio improves the efficiency for developers by providing an end-to-end tool chain that converts parts of the C language into circuits and automatically transforms them into QAP form. Based on this, Parno et al. evaluated zk-SNARK performance in actual applications such as matrix multiplication and demonstrated its practicality. They also fixed the proof size to 288 bytes regardless of the complexity of the computation. However, Pinocchio cannot prevent replay attacks in which an attacker reuses a previously generated proof after seizing it on the communication channel.

Groth16, proposed by Jens Groth, is an efficient zk-SNARK scheme that improves the efficiency of pairing-based zk-SNARKs to a level close to the theoretical optimum [21]. Groth16 reduces the proof size to only three group elements and simplifies verification to use only three pairing operations. Therefore, Groth16 is recognized as one of the most efficient general zk-SNARK protocols. However, Groth16 also cannot prevent replay attacks.

Kim et al. pointed out that existing zk-SNARK schemes such as Pinocchio and Groth16 have malleability issues and proposed an advanced zk-SNARK that improves this property [22]. Malleability means that a new valid proof can be generated by modifying a previous proof. In Groth16, this property is allowed to reuse the same witness and improve the proof generation process. However, if an attacker abuses malleability, the attacker may generate a valid proof without knowing the intended witness. Kim et al.’s scheme is a secure RBAC construction that ensures the same efficiency as Groth16 while providing non-malleability. Nevertheless, it also cannot prevent replay attacks.

These results show that existing zk-SNARK schemes focus on succinctness and non-malleability, but do not address the freshness of proofs. Therefore, a separate mechanism is required to prevent replay attacks when zk-SNARK is applied to access control protocols. This observation motivates our hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK protocol.

3.1.2. Hash Chain-Augmented zk-SNARK Protocol

In this subsection, we propose a hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK protocol. Existing zk-SNARK schemes can be used to verify the same statement multiple times with a previously generated proof. This property is convenient for efficiency, but in the context of access control, it allows replay attacks: an attacker who obtains a valid proof can reuse it to gain unauthorized access.

To address this problem, we augment Groth16-based zk-SNARK with a hash chain. The prover and verifier share the same hash chain value that is initialized in the Trusted Setup phase. After that, both sides use the current hash chain value when the prover generates the proof and the verifier checks the proof. In this way, each proof is bound to the current hash chain state and cannot be reused once the hash chain is updated. The proposed protocol achieves replay resistance without complex additional mechanisms such as timestamps or nonces, and preserves non-malleability by integrating the hash chain into the proof and verification equations.

Table 1 presents the system parameters of the hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK.

Table 1.

System parameters for hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK.

- Trusted Setup

The Trusted Setup phase is where the TA generates the CRS and the initial root , and sets the same hash chain between the prover P and the verifier V to establish basic trust. The relation used in this phase is defined as

The Trusted Setup phase proceeds as follows.

- Step 1.

- TA selects random values and generates . Here,andare generated. The notation and means and , respectively.

- Step 2.

- TA selects a random , computes , and publishes .

- Step 3.

- P computes using its own identity and sends to V via a secure channel. Then, V receives and computes . At the end of this step, P and V share the same initial root for their hash chain.

- Prove

The Prove phase is where P generates the zero-knowledge proof using its witness. To prevent replay attacks, the hash chain value is explicitly included in the proof.

- Step 1.

- If it is the first proof, P sets . Then, P sets and defines . Here, are the public statements, are the witness values held by P, and is the current hash chain value .

- Step 2.

- P selects random values and generates as follows:where the hash chain is bound to the proof by

- Step 3.

- P generates the proof and sends it to V. After sending the proof, P updates the hash chain value as

- Verify

The Verify phase is where V checks whether the received proof is valid for the statement and the current hash chain value.

- Step 1.

- V reconstructs the public input vector for the statement and the current hash chain value , and computes the corresponding and . Then, V verifies whether

- Step 2.

- If the verification succeeds, it proves that the prover possesses a valid witness satisfying the statement. Additionally, V updates the hash chain value as

3.1.3. Analysis of zk-SNARK

In this subsection, we analyze the proposed zk-SNARK in comparison with existing zk-SNARK schemes. Table 2 summarizes the comparison.

Table 2.

Proposed zk-SNARK vs. existing zk-SNARK.

Existing zk-SNARK schemes can be verified using a previously generated proof for the same statement. This allows efficient repeated verification but also enables replay attacks. If an attacker obtains a valid proof, the attacker can use it again without generating a new proof. In an access control scenario, this may lead to unauthorized access and serious security problems.

In contrast, the proposed zk-SNARK uses the hash chain values and that are synchronized and shared by P and V. When generating the proof , P includes in the computation of C through and . When verifying, V uses its current hash chain value in the same way. If an attacker reuses a previous proof , the verification fails because and the equations in the verification step do not hold. Therefore, the proposed zk-SNARK can prevent replay attacks while keeping the same asymptotic complexity as Groth16 and Kim et al.’s scheme.

3.2. RBAC

In this subsection, we introduce existing RBAC schemes that are related to our work. Among various RBAC approaches, we focus on I-RBAC (identity-based RBAC) schemes and PE-RBAC (Privacy-Enhanced RBAC) schemes that provide role privacy to some extent. These schemes are used as comparison points in the analysis of Section 5.

3.2.1. Identity-Based RBAC

Saxena and Alam proposed RBACIBE, which combines RBE (Role-Based Encryption) with IBBE (Identity-Based Broadcast Encryption) to solve data security problems in untrustworthy cloud environments [23]. They pointed out two problems of existing ABE (Attribute-Based Encryption) based schemes: the need to update all users’ keys when a user is revoked, and the irregular key size. To overcome these limitations, they proposed a new RBAC scheme. Their scheme manages role hierarchy and keys through a TGM (Trusted Group Manager) and improves efficiency by allowing each user to manage several roles with one identity-based key. It also provides efficient revocation by invalidating the public key when the user is revoked. However, it does not provide role privacy.

Sultan et al. proposed a new RBE scheme based on I-RBAC [24]. Their scheme allows data access even when the user does not directly hold the role and key of another organization using PRE (proxy re-encryption). It also supports outsourcing decryption to reduce the user’s computation cost. However, this scheme also does not provide role privacy.

Xu et al. proposed an RBAC scheme that combines IBC with RBAC to ensure data confidentiality and secure access control in untrustworthy cloud environments [25]. They pointed out that existing schemes do not provide dynamic policies and suffer from efficiency degradation due to computation overhead. Their scheme improves efficiency by applying role inheritance and hybrid encryption. However, it cannot provide role privacy because the cloud stores the tuple UR, which directly stores the user–role relationship.

3.2.2. PE-RBAC

PE-RBAC is an RBAC scheme proposed by Zhang et al. that provides role privacy against external attackers [26]. In PE-RBAC, an IoT device proves its role to the CP (cloud platform) through a challenge–response protocol using a random number and a pseudo-random number. When the IoT device proves its role, it does not send the role directly.

Instead, it generates a blind value based on all possessed roles and constructs k indexes of a GBF (Garbled Bloom Filter) based on this blind value. The device selects a random value , where S is a pseudo-random number set generated from a pseudo-random seed. Then, is split into , and each is stored at for .

The CP generates based on the required roles for access and the request values from the IoT device. Then, CP computes and verifies whether . If , the IoT device is considered to have the required role .

However, PE-RBAC has a limitation that CP can still learn which roles the IoT device possesses. For example, if the IoT device generates a GBF based on and sends it to CP, the CP can test combinations such as and infer that the device holds and . Therefore, PE-RBAC can protect role privacy from external attackers, but it cannot provide robust role privacy because CP itself can learn the device’s roles.

These limitations of I-RBAC and PE-RBAC show that existing RBAC schemes either do not hide roles from the verifier or only partially hide them. This motivates our cross-domain RBAC scheme based on zk-SNARK, where the CDS verifies the user’s authorization without learning the concrete role, as described in Section 4.

4. Proposed RBAC for Cross-Domain Cloud Environments

In this section, we introduce the proposed RBAC scheme for cross-domain cloud environments. The goal of this section is to explain how the scheme provides robust role privacy and replay attack resistance based on the hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK described in Section 3.1.2, and how this mechanism is embedded into a practical cross-domain data sharing process.

First, we present the system model, basic assumptions, and main system parameters. Next, we describe the system objects and the threat model. Finally, we explain the full protocol flow in four phases (Setup, Registration, Access Policy Generation, and Cross-Domain Data Request), and show how each phase corresponds to the overall scenario in Figure 1 and the parameters in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Overall scenario of the proposed scheme.

Table 3.

System parameters for the proposed scheme.

In the proposed scheme, the CDS only checks whether the user has an allowed role for the requested access. The role value itself is not shown in this process, and the CDS cannot know which role the user belongs to. The DA (domain administrator) already knows the role of each user because the role key must be generated in the registration step. Therefore, DA is not considered part of the robust role privacy guarantee. Under this assumption, the verification works without exposing the role to the CDS. Metadata leakage, side-channel attacks, and similar issues are not included in the threat model of this paper.

For clarity, we make the following assumptions about the protocol execution.

- The prover and verifier use a communication channel where messages are delivered in the expected order. Each proof is treated as one request, and all messages related to the proof are tied to that request. If a message breaks the order or is duplicated due to network problems, then it is outside the scope of this model and must be handled by the deployment environment.

- The hash chain update is only used for blocking replay attacks. The update follows the next step of the hash value according to the description in Section 3.1.2. Handling parallel proofs or recovery when the process stops is not considered in this paper and should be treated as an implementation issue in the target system.

- The hash value is tied to the public input . Therefore, even if an old hash value is recorded by an attacker, it cannot be reused for another request with a different .

Figure 1 shows the overall scenario of the proposed cross-domain RBAC scheme, including the interaction among the user, CDS and DA in each domain. Table 3 summarizes the system parameters used throughout this section. These parameters are referenced later when we describe the protocol phases and the cost analysis.

4.1. System Objects

In this subsection, we describe the main objects in the proposed cross-domain RBAC system. These objects correspond to the entities that appear in Figure 1 and to the parameters in Table 3.

- Cross-domain solution: CDS is a security gateway that processes access policies set by the DA. CDS manages data that is sent to another domain or is received from another domain to maintain the security of the domain. In the proposed scheme, CDS also verifies the hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK proof and updates its local hash chain value.

- Domain administrator: DA is the manager who controls users in its domain. DA issues IBS and IBE keys to users, generates access policies, and sets them in the CDS. Each domain has an independent DA, so domains can keep independent security configurations.

- User: The user belongs to a domain and either requests data from another domain or sends requested data. The user obtains identity-based keys from the DA in the registration phase and, later, proves the possession of a role using the role’s IBS signing key as a witness in the zk-SNARK circuit.

4.2. Threat Model and Formal Security Definition

In this subsection, we describe the adversary model and formalize the main security properties of the proposed scheme. These properties are used later in Section 5 to analyze and compare the scheme with existing RBAC approaches.

4.2.1. Adversary Model

We assume a cross-domain cloud environment where the user generates a proof and the CDS verifies it, and each domain is managed by an independent domain administrator. In this environment, the communication channel is not trusted, so the messages between these entities can be observed or changed by an external attacker. The adversary A works on this network channel, but A does not break the hardness assumptions of the cryptographic primitives used in the proposed scheme.

The adversary model is considered as follows.

- A can store a valid zk-SNARK proof and try to send it again in another session.

- A can observe the exchanged data and message structure and try to guess the role of the user from this information.

- A can change the protocol flow by modifying, inserting, or reordering messages while the protocol is running.

- The trusted authority and the secret keys of legitimate users are not compromised in the basic model, and A cannot obtain these values unless we explicitly describe such a case.

- A does not break the soundness of the zk-SNARK system, the collision resistance of the hash chain, or the unforgeability of the identity-based signature scheme.

4.2.2. Role Privacy

In this subsection, we define the role privacy of the proposed RBAC scheme. Role privacy means that the CDS and an external attacker cannot know which role the user has, even if they can see the protocol messages and the proof.

The role privacy game between a challenger and an adversary A is defined as follows.

- Step 1.

- The challenger runs the setup algorithm of the proposed scheme and produces all public parameters to A.

- Step 2.

- The adversary A selects a target access policy and two different roles and that are both valid for this policy.

- Step 3.

- The challenger chooses a random bit . Then, the challenger simulates an honest user who has the role and runs the proposed protocol with the CDS. The challenger produces the full protocol transcript T (including the proof and the communication messages) to A.

- Step 4.

- After observing T, the adversary A outputs a guess about whether the user used role or role .

The advantage of A in this game is defined as

The proposed scheme provides role privacy if, for any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary A, the advantage is negligible in the security parameter . In this way, even if A can see all protocol messages and the proof, A cannot distinguish which valid role is used in the proof with non-negligible advantage.

4.2.3. Replay Attack Resistance

In this subsection, we define the replay attack resistance of the proposed scheme. Replay attack resistance means that an attacker cannot reuse an old valid proof or protocol transcript to obtain a new successful authorization in a later session.

The replay attack game between a challenger and an adversary A is defined as follows.

- Step 1.

- The challenger runs the setup algorithm of the proposed scheme and executes one honest protocol session between a user and the CDS. In this session, the user sends a valid proof, and the CDS accepts it. The challenger records the full transcript T of this session.

- Step 2.

- The challenger produces the transcript T to the adversary A. After that, A can use T and can also generate new messages.

- Step 3.

- Without the help of the honest user, the adversary A sends messages to the CDS and tries to start a new session.

- Step 4.

- The adversary A succeeds in the replay game if the CDS accepts a request in this new session based only on the old transcript T or on values that were already used in the previous session.

We say that the proposed scheme is replay-attack resistant if the success probability of any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary A in the above game is negligible. In this case, even if A stores a previous valid proof and the corresponding hash chain value, A cannot make the CDS accept again with the same proof, because the hash chain and the proof are always bound to the current session state.

4.2.4. Protection Against Man-in-the-Middle Attacks

In this subsection, we define the protection against man-in-the-middle attacks of the proposed scheme. This property means that an attacker who stays on the communication channel cannot change the protocol messages without being detected by the CDS or the honest party.

The man-in-the-middle game between a challenger and an adversary A is defined as follows.

- Step 1.

- The challenger runs the setup algorithm of the proposed scheme and provides the public parameters to A.

- Step 2.

- The adversary A can observe all signed messages that are exchanged between the user, the CDS, and the domain administrators. If needed, A may also ask for valid signatures on messages of its choice through a signing oracle.

- Step 3.

- At the end of the game, A outputs a message–signature pair and claims that it is a valid message from a specific honest entity in the system.

- Step 4.

- The adversary A wins this game if the signature is accepted as a valid signature of that honest entity, but the pair was never produced by this honest entity and was never returned by the signing oracle.

The proposed scheme provides communication integrity against man-in-the-middle attacks if any probabilistic polynomial-time adversary A can win the above game only with negligible probability. Through this, if an attacker modifies, inserts, or reorders protocol messages on the network, the modified message cannot have a valid signature of an honest entity, so the CDS detects the attack and the protocol fails.

4.3. Process of Proposed RBAC Scheme

In this subsection, we describe the full protocol flow of the proposed cross-domain RBAC scheme. The process consists of four phases: Setup, Registration, Access Policy Generation, and Cross-Domain Data Request. The first three phases are executed inside each domain and prepare the necessary keys and policies. The last phase corresponds to the cross-domain data exchange scenario shown in Figure 1.

4.3.1. Setup

Setup is the first phase. In this phase, each DA builds its own cryptographic environment. Each DA generates public parameters, master keys, and entity keys for its own domain. So, every domain can keep independent security. Also, this phase includes the CRS creation step of zk-SNARK. The Setup phase is as follows.

- Step 1.

- Each DA generates its parameters. For domain A, selects a prime , elliptic curve groups , a bilinear map , generators , and hash functions

- Step 2.

- chooses the master secret key and computes the master public key .

- Step 3.

- computes the IBS signing key and the IBE decryption key , where and .

- Step 4.

- Public parametersare published. Also, performs the Trusted Setup process described in Section 3.1.2 over and publishes . does the same process in its domain.

4.3.2. Registration

The Registration phase consists of user registration and role assignment. This phase is executed only inside one domain. Through this phase, the user is registered formally and obtains cryptographic keys from IBS and IBE. We describe the registration of a user in domain A.

- User Registration

User registration of domain A is as follows.

- Step 1.

- User sends identity to and .

- Step 2.

- computes the IBS signing key and the IBE decryption key , where and .

- Step 3.

- sends securely to .

- Step 4.

- and initialize their shared hash chain value according to the hash chain setup described in Section 3.1.2.

- Role Assignment

Role assignment is as follows.

- Step 1.

- User requests role from .

- Step 2.

- If the request is approved, computes the role signing key and sends it to .

4.3.3. Access Policy Generation

Access Policy Generation is the phase where each DA makes the internal RBAC rules for cross-domain interaction. These policies are set inside the CDS of each domain, and the users in the same domain can use them. The process is as follows.

- Step 1.

- defines the policy of its domain. A policy is the set of internal roles that can send data or requests to one external domain. This policy is written as . Also, generates the domain access list , where are domain identifiers.

- Step 2.

- does the same process in its domain.

- Step 3.

- Each DA sets the access policy and to its own CDS.

4.3.4. Cross-Domain Data Request

The Cross-Domain Data Request phase is the main phase where two domains exchange data through each CDS. This phase corresponds to the end-to-end scenario in Figure 1. First, the user finds the roles that are allowed by the local egress policy. This set of roles is used as the public input of the zk-SNARK proof. Then, the user makes a proof to show that he owns one role in the allowed set. In this way, the entire process is controlled by the CDS while hiding the concrete role.

For clarity, we divide this phase into three logical parts: (i) user-side role proof generation, (ii) verification and forwarding by , and (iii) response processing and sanitization by .

- (i)

- User-side role proof generation.

- Step 1.

- makes the request . checks the egress policy and obtains the allowed set .

- Step 2.

- finds a role that he owns and that is in . Then, makes the input vector for zk-SNARK.

- is the constant public input.

- are public inputs, which are the hash values of each role: for .

- and are private inputs. We write for a fixed public encoding that maps a group element in to field elements in when it is used as a zk-SNARK witness. Also, is the index of role in and is the scalar representation of .

- Step 3.

- makes the proof components from the vector a:Here, the hash chain is bound to the proof by settingwhere is the public input that represents the current request.

- Step 4.

- makes the proof and generates and .

- Step 5.

- Then, sends to .

- (ii)

- Verification and forwarding by .

- Step 1.

- receives the package and verifies . It makes the public input vector from its own and the chain . Then, it verifies by checking

- Step 2.

- After the verification result is true, and update the hash chain value . Then, makes the sanitized requestsigns it as , and sends to .

- Step 3.

- verifies . Then, it checks its local policy to decide whether the request from domain A is allowed. If the policy denies the request, the process stops at this point.

- (iii)

- Response processing and sanitization by .

- Step 1.

- If the policy allows the request, forwards the request to the data owner .

- Step 2.

- encrypts with and sends the ciphertext to .

- Step 3.

- computes , where f_remove_metadata is a function that removes metadata of .

- Step 4.

- generates a symmetric key and encrypts . Then, it encrypts as .

- Step 5.

- signs and sends to .

- Step 6.

- verifies . If it is valid, it decrypts and obtains .

- Step 7.

- checks for malicious code. If the data is not malicious, it computes and sends it to .

- Step 8.

- Finally, decrypts with and obtains .

Through these four phases, the proposed RBAC scheme realizes cross-domain data sharing while achieving the role privacy, replay attack resistance, and man-in-the-middle protection defined in the previous subsection. In Section 5, we compare this scheme with existing RBAC approaches using the security properties and computational cost summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Proposed RBAC vs. existing RBAC.

5. Analysis of Proposed RBAC

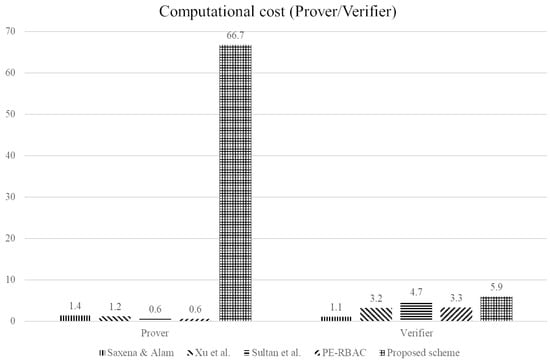

In this section, we analyze the proposed RBAC scheme by comparing it with existing RBAC schemes introduced in Section 3.2. Table 4 summarizes the security properties and computational cost of Saxena & Alam’s I-RBAC, Xu et al.’s scheme, Sultan et al.’s MO-RBE, Zhang et al.’s PE-RBAC, and the proposed cross-domain RBAC. Figure 2 visualizes the normalized computational cost of the prover and verifier for each scheme based on the operation weights defined in this section.

Figure 2.

Analysis of computational cost [23,24,25,26].

The comparison criteria in Table 4 are derived from the common security and efficiency requirements that appear in existing RBAC and I-RBAC studies, such as role privacy, resistance to replay attacks, protection against man-in-the-middle attacks, and the computational cost of the prover and verifier. Saxena & Alam, Xu et al., Sultan et al., and Zhang et al. all emphasize these properties in different ways as essential for practical cloud or cross-organization access control. Therefore, we adopt these properties as the main axes of comparison so that the proposed scheme can be evaluated under the same perspective as the existing work. In particular, we focus on how each scheme deals with the visibility of roles, the freshness of protocol messages, and the integrity of communication channels, because these points are directly related to the threat model of cross-domain clouds.

In the following subsections, we explain in detail how each symbol and parameter in Table 4 is interpreted and how the values in Figure 2 are obtained. In addition, we describe how the existing schemes achieve or fail to achieve the comparison criteria and how the proposed scheme improves over these schemes in terms of security properties and cost.

5.1. Robust Role Privacy

Robust role privacy means that the verifier does not know the prover’s exact role when the prover proves their role. In the cross-domain cloud environment, this property is especially important because the role name itself can reveal sensitive information about the user’s function or position. For example, if the CDS can directly see whether the user belongs to a high-privilege role such as “Doctor” or “Security Administrator”, it can become easier for attackers or insiders to profile potential targets.

Existing I-RBAC schemes such as Saxena & Alam’s RBACIBE and Xu et al.’s RBAC model combine RBAC with identity based cryptography to improve key management in the cloud. However, as described in Section 3.2.1, RBACIBE manages role hierarchy and keys through a Trusted Group Manager and allows each user to manage several roles with one identity based key, but it does not consider hiding the role from the verifier. The cloud or group manager must know the explicit role information to generate and update the corresponding keys, so the role is inherently visible to the verifier. In Xu et al.’s scheme, the cloud stores the user–role relationship in the UR tuple for efficient access control, so the cloud can always see which role is associated with each user during authorization. Therefore, these I-RBAC schemes cannot provide role privacy to the verifier and the row “Robust role privacy” in Table 4 is marked as “X” for these schemes.

Sultan et al.’s MO-RBE scheme also follows the I-RBAC line by combining role based encryption with identity based broadcast encryption and proxy re-encryption. Their work focuses on improving flexibility in a multi-organization context and supporting outsourced decryption through public and private clouds. Although this approach is suitable for distributing the decryption workload, the role information is still visible in the access structure and ciphertext. In particular, the access policy explicitly describes which roles can decrypt the ciphertext, so the cloud and the collaborating organizations can still guess which roles are permitted or used in each access request. In this situation, role names and access patterns remain observable. Therefore, this approach cannot provide robust role privacy, and Table 4 also marks “X” for MO-RBE.

PE-RBAC uses GBF-based blind values to avoid sending the role directly during the role proof process. In PE-RBAC, the IoT device first computes a blind value from the set of all roles it possesses and then derives the GBF indices based on this value. In this way, external attackers who only observe the messages cannot immediately learn the role because the role is indirectly encoded in the GBF. However, as explained in Section 3.2.2, the cloud platform can generate various values and test them against the GBF to infer which roles the device has. Since the verifier can adaptively query the GBF, it can gradually narrow down the candidate roles and reconstruct the role set of the device. Thus, PE-RBAC can protect role privacy only from external attackers but cannot hide the role set from the verifier itself. For this reason, PE-RBAC is also not regarded as providing robust role privacy in Table 4.

To solve these limitations, the proposed scheme uses a hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK. In the proposed scheme, the user encodes the possessed role signing key and the allowed role set into the witness of the zk-SNARK circuit and proves only that a valid role signing key exists that satisfies the access policy. The concrete value of the role or the index of the role is not revealed in the proof or in the messages observed by the CDS. The CDS only checks whether the proof is valid with respect to the public input and the circuit, and it does not receive any explicit information about which role satisfies the policy. As summarized in Table 4, the row “Robust role privacy” is marked as “O” only for the proposed scheme, while all existing schemes are marked as “X” or provide only partial protection. In other words, verifies only whether the proof is valid according to the circuit and the public input, and it does not learn which specific role satisfies the policy.

From this comparison, we can see that the existing I-RBAC and PE-RBAC schemes mainly focus on key management and access efficiency, and they either ignore role privacy or only protect it against external attackers. In contrast, the proposed cross-domain RBAC explicitly targets robust role privacy against both external attackers and the CDS verifier using zk-SNARKs. Through this, the proposed scheme achieves a level of role privacy that the existing RBAC and PE-RBAC schemes cannot provide.

5.2. Prevent Replay Attack

A replay attack is the reuse of a previously valid value (for example, a proof or credential) for unauthorized access. If unauthorized access is successful, it may result in serious security problems, especially in cross-domain scenarios where one compromised proof can be used repeatedly to bypass the CDS and to access multiple domains or resources.

Saxena & Alam’s RBACIBE and Xu et al.’s RBAC scheme are based on static identity-based keys. Their main goal is to integrate RBAC with identity based encryption or signature so that the cloud can manage users and roles more conveniently. However, as described in Section 3.2.1 and summarized in Table 4, they do not introduce any explicit freshness mechanism such as nonces, timestamps, or per-session one-time values for the role proof. The issued keys and role information remain valid until revocation, and there is no cryptographic binding between a single authorization session and the proof. Therefore, once an attacker obtains a valid credential or protocol message, the attacker can try to reuse it in a later session. For this reason, the row “Prevent replay attack” in Table 4 is marked as “X” for these schemes.

On the other hand, MO-RBE and PE-RBAC include interactive procedures with random values so that simple replay of the same message does not lead to successful authorization. For example, MO-RBE relies on fresh ciphertexts and re-encryption operations between the public cloud and private clouds, and PE-RBAC uses random challenges and responses when checking GBF entries. Accordingly, Table 4 marks “O” for these schemes in the replay attack row. However, as discussed in the previous subsection, MO-RBE and PE-RBAC still do not provide robust role privacy because the verifier can observe or infer the role information from the access structure or GBF behavior.

The proposed RBAC scheme prevents replay attacks by binding the zk-SNARK proof with a synchronized hash chain between the prover and verifier. As explained in Section 3.1.2, the prover and verifier share an initial hash value during the Trusted Setup phase, and then both maintain their own hash chain values and . When the prover generates the proof , the current hash chain value is embedded into the witness and reflected in the proof component C. After each successful verification, both sides update their hash chain values by applying the hash function to the previous value and the public input .

If an attacker reuses a previous proof , the hash chain value contained in does not match the current verifier-side hash chain value. As a result, the verification equation fails and the CDS rejects the request, even if the underlying role signing key is still valid. This behavior is reflected in Table 4, where the proposed scheme is marked as “O” in the “Prevent replay attack” row. Compared with MO-RBE and PE-RBAC, the proposed scheme provides replay resistance while simultaneously preserving the zero-knowledge property and robust role privacy, because the hash chain value is handled only inside the zk-SNARK circuit and does not expose additional identifying information.

From the above comparison, we can conclude that existing I-RBAC schemes do not address replay attacks at the protocol level and that MO-RBE and PE-RBAC handle replay only partially without hiding the role from the verifier. The proposed scheme integrates the hash chain mechanism tightly with the zk-SNARK proof so that each authorization session is uniquely bound to the current hash state. In this way, the proposed cross-domain RBAC achieves replay resistance under the same parameter setting where the existing schemes remain vulnerable or provide weaker guarantees.

5.3. Prevent MitM

MitM (man-in-the-middle) attack is an attack in which the attacker intervenes between two communicating entities and eavesdrops or modifies the exchanged messages. In cross-domain cloud environments, such attacks can target not only the user–CDS channel but also the CDS–CDS and CDS–DA channels. If the protocol does not protect the integrity and authenticity of messages, an attacker can change the requested file, policy, or domain information without being detected.

Among existing schemes, Saxena & Alam assume that the communication channel is secure. They focus on key management and revocation in an untrustworthy cloud environment but do not provide a concrete mechanism to guarantee the integrity and authenticity of request/response messages inside the protocol description. Therefore, as summarized in Table 4, the row “Prevent MitM attack” is marked as “X” for their scheme. In contrast, Xu et al., MO-RBE, and PE-RBAC adopt cryptographic protection for the protocol messages using signatures or authenticated encryption, so they are marked as “O” in the same row. These schemes explicitly require that the important messages be protected by cryptographic keys and that the verifier check the validity of the received messages.

The proposed RBAC scheme provides MitM protection using IBS signing keys for all important messages. As described in Section 4.3, all entities, including users, DAs, and CDSs, receive IBS signing keys based on their identities from the TA. When a user requests access to a file, the user signs the request with their signing key and sends the signature together. The DA or CDS that receives the message verifies the signature using the user’s identity-derived public information and confirms that the message has not been modified and was indeed generated by the corresponding user.

In this way, all critical messages in the cross-domain protocol, such as access requests, policy-related messages, and data transfer notifications, are signed and verified. If an attacker intercepts and modifies the message on the network, the signature verification fails, so the protocol is aborted. Therefore, the proposed RBAC scheme can strongly guarantee the integrity and authenticity of the communication channel and defend effectively against man-in-the-middle attacks, which is reflected by “O” in the “Prevent MitM attack” row of Table 4. Compared with the existing schemes, the proposed scheme follows the same basic strategy as Xu et al., MO-RBE, and PE-RBAC regarding MitM protection, but it integrates this with robust role privacy and replay resistance in a cross-domain CDS setting.

5.4. Computational Cost

In this subsection, we explain in detail the parameters and operation weights used for comparing the computational cost in Table 4 and clarify the meaning of the higher values in the cost analysis and Figure 2. By doing so, we can evaluate whether the additional security properties of the proposed scheme are obtained at a reasonable computational cost compared with the existing schemes.

Here, are the main parameters used in our cost expressions. In more detail, m denotes the number of computation gates included in the zk-SNARK circuit, n is the number of roles that belong to one layer in the role hierarchy, and ℓ is the number of public inputs that are given to the verifier. In addition, denote role-related parameters: is the number of roles that appear in the access policy or ciphertext, is the number of roles that the requester actually presents, and is the number of roles that the verifier manages in its system. For the cryptographic operations, we use to denote pairing, exponentiation, point addition, and hash operation, respectively. Based on these notations, every term that appears in the rows “Prover computational cost” and “Verifier computational cost” in Table 4 is written by combining with the operation symbols , so that all schemes can be compared under the same notation.

For example, the prover cost of Saxena & Alam’s scheme is expressed as

which means that the prover needs one pairing operation, exponentiation operations, and one hash operation when generating the access token. The verifier cost indicates one pairing, one exponentiation, and one hash for verifying the token. In Xu et al.’s RBAC model, the verifier must perform three pairings and two exponentiations and two hash operations for verification, which is shown as in Table 4. Compared with Saxena & Alam, Xu et al. increase the number of pairing operations on the verifier side to support their access control logic.

For MO-RBE, the authors present the cost by separating the roles of the public cloud and each private cloud, and we follow this style in Table 4. The prover-side cost is summarized as , which means that the encryption phase mainly consists of exponentiation operations whose number depends on . On the verifier side, the cost is divided into “PubC: ; #PrivCk: ; @PrivCk: ; User: ”, showing how many operations are required at each entity. In other words, MO-RBE spreads the verification and decryption workload over PubC, multiple PrivCk, and the user, but the overall procedure still requires a non-negligible amount of pairing and exponentiation. In the case of PE-RBAC, the verifier cost is written as because the cloud platform must check GBF entries that are related to all roles managed in the system, and the number of exponentiation operations grows according to . This reflects the fact that PE-RBAC reduces role exposure but pays a cost that increases with the size of the role universe.

For the proposed scheme, the prover cost is

and the verifier cost is

These expressions reflect the fact that the prover must execute the zk-SNARK proof generation algorithm over a circuit with m gates and ℓ public inputs, while the verifier must evaluate a constant number of pairing operations and linear numbers of exponentiations, additions, and hashes in ℓ. Compared with the existing schemes, the proposed RBAC introduces additional exponentiation and point addition operations due to the zk-SNARK-based role proof and hash chain binding.

For the comparative evaluation, the operation weights and parameter values are assumed as follows:

Here, is used as the basic cost unit and the costs of other operations are normalized relative to one pairing. Using these weights, each expression in Table 4 is converted into a single numeric value by summing with the above coefficients. For example, the total cost of a scheme is obtained by substituting the parameter values into its cost expression and computing

Figure 2 presents the result of this normalization. The x-axis is divided into two groups, “Prover” and “Verifier,” and for each group, the bars correspond to Saxena & Alam, Xu et al., Sultan et al. (MO-RBE), PE-RBAC, and the proposed scheme. The y-axis represents the normalized computational cost in units where a single pairing has cost 1. In this plot, larger values directly mean that more weighted cryptographic operations are required and thus higher computational overhead is expected.

As shown in Figure 2, the prover-side cost of the proposed scheme is significantly higher than that of existing schemes. This is because the proposed scheme performs zk-SNARK-based role proofs to ensure strong role privacy and integrates the hash chain into the proof, so the number of exponentiation and point addition operations grows with the circuit size m. In contrast, the existing schemes avoid this overhead because they either reveal the role directly or do not combine the role proof with a zero-knowledge argument. On the other hand, the verifier-side cost of the proposed scheme remains within a similar range to existing schemes because the zk-SNARK verification algorithm requires only a constant number of pairing operations and linear overhead in ℓ, which is comparable to the verification cost in Saxena & Alam, Xu et al., MO-RBE, and PE-RBAC.

Therefore, the phrase higher values in the cost analysis means that, under the same parameter setting and operation weight model, the proposed scheme requires more normalized computation units, especially on the prover side, than existing RBAC schemes. This overhead is the cost paid to obtain robust role privacy and replay attack resistance in the cross-domain cloud environment. For applications where privacy and security requirements are strong, such additional computation on the prover side can be acceptable because the verification burden on the CDS remains practical and comparable to existing solutions. Through this comparison, we can see that the proposed scheme achieves stronger security properties than the existing RBAC schemes while keeping the verifier-side cost at a similar level, and the trade-off is clearly quantified by Table 4 and Figure 2.

6. Conclusions

As the IT environment becomes more advanced, data interoperability becomes more important in cloud environments. However, data sharing between clouds that have different security policies can cause a lack of trust and can lead to serious security threats such as unauthorized access and sensitive information leakage. RBAC can be used as an effective access control mechanism in this setting, but most existing schemes are limited to single-domain environments and cannot reflect the complexity of actual cross-domain cloud environments. In addition, they still have critical problems such as role privacy leakage during the role proof process.

In this paper, we proposed a new RBAC scheme for cross-domain cloud environments by combining a hash chain-augmented zk-SNARK with Identity-Based Cryptography. The proposed scheme allows a user to prove the ownership of the required role to a CDS without revealing the concrete role value, so the verifier cannot learn the user’s role name during the access process. Through this, the proposed scheme achieves robust role privacy that existing RBAC schemes and PE-RBAC could not provide. Furthermore, by embedding a synchronized hash chain into the proof, the proposed scheme can effectively prevent replay attacks caused by reused proofs and improve the reliability of cross-domain access control.

From a theoretical perspective, this work analyzes role privacy, replay resistance, and message integrity in the cross-domain RBAC setting and shows that the proposed construction satisfies these security requirements. From a practical perspective, the proposed RBAC scheme is architecturally applicable to various cross-domain cloud environments where domains do not fully trust each other and where role information itself may become a target of attack.

For future work, we plan to overcome the limitation of Identity-Based Cryptography, which discloses the user identity to the TA, by applying other cryptographic techniques that reduce identity exposure while preserving the advantages of the current design. It is also necessary to reduce the computational cost of the zk-SNARK-based role proof so that the proposed scheme can be applied more efficiently to large-scale cloud environments. In addition, integrating other privacy-enhancing technologies to strengthen secure data sharing in cross-domain cloud environments is an important research direction. Finally, we will design and implement a real-world experimental environment to evaluate the practicality and effectiveness of the proposed scheme in realistic cross-domain cloud scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C.Y.; methodology, D.G.L.; validation, S.C.Y. and D.G.L.; formal analysis, D.G.L.; investigation, S.C.Y.; resources, D.G.L.; data curation, D.G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.Y.; writing—review and editing, D.G.L.; visualization, S.C.Y.; supervision, S.-H.K.; project administration, I.-Y.L.; funding acquisition, I.-Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is the result of commissioned research project supported by the affiliated institute of ETRI [2025-055], Technology Innovation Program (RS-2024-00443436) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy (MOTIE, Korea) and BK21 FOUR (Fostering Outstanding Universities for Research) (No. 5199990914048).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sepúlveda-Rodríguez, L.E.; Garrido, J.L.; Chavarro-Porras, J.C.; Sanabria-Ordonez, J.A.; Candela-Uribe, C.A.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, C.; Guerrero-Contreras, G. Study-based systematic mapping analysis of cloud technologies for leveraging it resource and service management: The case study of the science gateway approach. J. Grid Comput. 2021, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Jin, S. Inter-cloud secure data sharing and its formal verification. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2021, 33, e4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooque, M.; Patidar, K.; Kushwah, R.; Saxena, G. An efficient data security mechanism with data sharing and authentication. ACCENTS Trans. Inf. Secur. 2020, 5, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.; Hossain, M.S. Secure data-exchange protocol in a cloud-based collaborative health care environment. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 11121–11135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Gondree, M.A.; Shifflett, D.J.; Khosalim, J.; Levin, T.; Irvine, C. A cloud-oriented cross-domain security architecture. In Proceedings of the 2010-MILCOM 2010 Military Communications Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 31 October–3 November; 2010; pp. 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, L.; Jacobson, D. DECA: DoD Enterprise Cloud Architecture Concept for Cloud-Based Cross Domain Solutions. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, Kyoto, Japan, 17–19 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daughety, N.; Pendleton, M.; Xu, S.; Njilla, L.L.; Franco, J. vCDS: A Virtualized Cross Domain Solution Architecture. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2021-2021 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 November–2 December; 2021; pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinker, C.; Millar, K.; Kaminsky, A.; Kurdziel, M.; Lukowiak, M.; Radziszowski, S. Exploring the Application of Homomorphic Encryption to a Cross Domain Solution. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2019-2019 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Norfolk, VA, USA, 12–14 November 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, M.; Schell, R.; Reed, E.E. A multi-level secure file sharing server and its application to a multi-level secure cloud. In Proceedings of the MILCOM 2015-2015 IEEE Military Communications Conference, Tampa, FL, USA, 26–28 October 2015; pp. 1224–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvay, R.J. Safety of Mixed Model Access Control in a Multilevel System. Ph.D. Thesis, Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.B.; Li, K.; Shi, R.H.; Shao, B. VC-DCPS: Verifiable Cross-Domain Data Collection and Privacy-Persevering Sharing Scheme Based on Lattice in Blockchain-Enhanced Smart Grids. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 12449–12461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Chen, F. Privacy and Integrity Preserving Computation in Distributed Systems; Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2011; p. 184. [Google Scholar]

- Akuthota, A.K. Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) in Modern Cloud Security Governance: An In-depth Analysis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2025, 11, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.U. Scalable Role-based Access Control Using The EOS Blockchain. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2007.02163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Emmanuel, N.; Khan, T.; Xiang, Y.; Hassan, H. Garbled role-based access control in the cloud. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 9, 1153–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, Q. Anonymous role-based access control on e-health records. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Xi’an, China, 30 May–3 June; 2016; pp. 559–570. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, H.; Gu, D.; Xie, W. Efficient pairing computation on elliptic curves in Hessian form. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Security and Cryptology, Athens, Greece, 26–28 July 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Boneh, D.; Franklin, M. Identity-based encryption from the Weil pairing. In Proceedings of the Annual International Cryptology Conference, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 19–23 August 2001; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kiltz, E.; Neven, G. Identity-based signatures. In Identity-Based Cryptography; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Parno, B.; Howell, J.; Gentry, C.; Raykova, M. Pinocchio: Nearly practical verifiable computation. Commun. ACM 2016, 59, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, J. On the size of pairing-based non-interactive arguments. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Vienna, Austria, 8–12 May 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Oh, H. Simulation-extractable zk-SNARK with a single verification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 156569–156581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, U.R.; Alam, T. Role based access control using identity and broadcast based encryption for securing cloud data. J. Comput. Virol. Hacking Tech. 2022, 18, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N.H.; Varadharajan, V.; Zhou, L.; Barbhuiya, F.A. A role-based encryption (rbe) scheme for securing outsourced cloud data in a multi-organization context. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2022, 16, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Yu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, F. Role-based access control model for cloud storage using identity-based cryptosystem. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021, 26, 1475–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, X. Privacy-Enhanced Role-Based Access Control for IoT Systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 27269–27279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).