Abstract

CuZn39Pb3 leaded brass is one of the most widely used alloys in machining, with a 100% machinability index. However, there has been a lack of research on the effects of coldworking on surface integrity (SI) and operating behaviour of CuZn39Pb3 components. This study addresses this knowledge gap by examining the effects of three optimised combined processes on surface roughness, a key SI characteristic. Specifically, samples were subjected to a turning process followed by diamond burnishing (DB); this combined process was performed under three conditions: conventional flood lubrication (F), dry (D), and dry and cool-assisted (D+C) conditions. Cool-assisted conditions were achieved using a special device with a cold air nozzle operating on the vortex tube principle. The D and D+C conditions represent environmentally sustainable alternatives because they eliminate the use of cutting fluids, thereby reducing their adverse effects on both the environment and human health. The resulting surfaces obtained after each of the three optimised combined processes (F, D, and D+C) exhibited mirror-like finishes with minimum average roughness Ra values of 0.054, 0.079, and 0.082 μm, respectively. In addition, the F- and D+C-processes resulted in surface profiles with negative skewness and kurtosis values greater than three. Since roughness shape parameters are known to influence the operating behaviour of machined components, these processes are suitable for improving wear resistance in boundary lubrication regimes.

1. Introduction

Copper–zinc alloys (i.e., brass) are versatile and inexpensive materials that are valued for their unique properties, including non-magnetism, high thermal and electrical conductivity, excellent machinability, strength, corrosion and wear resistance, self-lubricating mechanism, and antibacterial properties. Consequently, these materials are widely used across industries such as electrical engineering, electronics, automotive manufacturing, and sanitation. Common brass products include door fittings, electrical components, plumbing fixtures, electric cables and components, heat exchangers, hydraulic and pneumatic parts, abrasives, adhesives, and automotive items such as brake pads, antennas, connectors, and radiators [1,2,3,4]. The annual processing volume of Germany and Northern Italy, which are key regions in which brass products are manufactured, is estimated to be 500,000–600,000 tons of brass per year [3].

The CuZn39Pb3 leaded brass alloy is one of the most widely used materials for machining, with a machinability index of 100%. This alloy complies with the RoHS II [5] and REACH [6] directives and is suitable for potable water applications. The high plasticity of this material is particularly suited for wire production [7]. The alloy is resistant to organic substances as well as neutral or alkaline compounds, while the excellent machinability of CuZn39Pb3 is primarily due to the presence of up to 3% lead in the alloy [8], allowing for excellent chip breaking, low tool wear, and high cutting performance [1]. Brinksmeier et al. [9] demonstrated the alloy’s excellent machinability during diamond turning and high-speed milling, while Schultheiss et al. [10] found significantly higher tool wear when machining the lead-free CuZn21Si3P alloy under similar conditions. CuZn39Pb3 alloy also has excellent sliding wear resistance: Küçükömeroğlu and Kara [11] found that the alloy performs best as a sliding component under vacuum conditions. The addition of low levels of aluminium and titanium was found to improve the refinement of its microstructure, thus enhancing its mechanical properties of the alloy [8].

One disadvantage of the CuZn39Pb3 alloy is its lead content, which is a toxic heavy metal even at low exposure levels [3,10]. Consequently, lead-free brass alloys have been considered as alternatives to address these environmental and health concerns. Anagnostis et al. [12] compared the fracture behaviour of CuZn39Pb3 with three lead-free brass alloys and found that the latter could replace conventional leaded brass in terms of basic mechanical properties. However, as mentioned previously, lead is responsible for the excellent machinability of CuZn39Pb3; consequently, reducing or eliminating lead results in long chip formation and increased thermal and mechanical stress on cutting tools [13,14]. Other disadvantages of the CuZn39Pb3 alloy include reduced resistance to stress corrosion cracking in ammonia environments, dezincification in hot acidic waters, and limited hot formability. In particular, the poor formability is due to the relatively low copper content (below 60%; for example, aluminium bronzes contain over 80% copper) [8]. Pantazopoulos and Vazdirvanidis [15] investigated a fractured hot-extruded CuZn39Pb3 hexagonal rod with a 6 mm flat cross-section and identified the presence of brittle intergranular fractures, with hot shortness being the primary failure mechanism.

Manufacturers have reported that semi-finished CuZn39Pb3 products have poor cold formability; however, studies on this issue are scarce. There is also a lack of information concerning the effect of surface layer modifications, such as reduced roughness, increased surface microhardness, residual compressive stresses, and a refined microstructure, on the mechanical, fatigue, and corrosion performance of this alloy. A promising, cost-effective approach to improving the surface integrity (SI) and thus the operational behaviour of CuZn39Pb3 alloy components is surface coldworking (SCW).

SCW involves the plastic deformation of a metal’s surface and near-surface layers at a temperature lower than its recrystallisation temperature. SCW techniques are categorised into dynamic and static methods [16]. Dynamic methods involve shock impacts on the treated surface using small particles; this approach originates from sand blasting methods pioneered by Tilgham in 1971 [17]. Modern dynamic methods include shot peening [18], laser shock peening [19], cavitation peening [20], waterjet cavitation impact [21], surface mechanical attrition treatment [22], and percussive burnishing [23]. A common feature of the dynamic methods is the dominance of the coldworking effect over smoothing effects.

Static methods, also known as burnishing methods, involve a hard, smooth deforming element that is pressed continuously against the surface being machined at a constant force while moving tangentially relative to the surface. The tangential contact between the deforming element and the surface may be rolling or sliding friction. Rolling-friction burnishing employs a ball or roller (cylindrical, barrel-shaped, or toroidal) and is described as ball burnishing [24,25] or roller burnishing [24,25,26,27], respectively. In slide burnishing [28], the working surface of the deforming element is usually spherical [29], less often cylindrical [30] or toroidal [31], and the material of the deforming element is a hard alloy [16]. When the deforming element is a natural or synthetic diamond, the process is called slide diamond burnishing or diamond burnishing (DB) [28,32]. This technique was introduced by General Electric in 1962 to improve the SI of metal components [33]. Detailed information on the development, technological capabilities, and prospects of DB is presented in [16]. DB is cheap, environmentally friendly, simple, and compatible with conventional and CNC machines, and merits wider distribution [28]. Accordingly, DB was employed in the present study.

Over the past six decades, DB has established itself as an effective finishing process for carbon [34], structural [35,36,37], tool [38], and stainless steels [39,40,41,42,43], as well as high-strength titanium [44], aluminium [45,46], and bronze alloys [47]. To date, the only study on brass (H62) was conducted by Luo et al. [48]. Comprehensive results on the impact of DB on SI, fatigue, wear, and corrosion resistance are reported in [16,49], while a review describing the correlation between SI and the performance of DB components can be found in [50]. However, studies investigating the effects of DB on the SI and performance of CuZn39Pb3 alloy components remain limited.

Conventional DB is performed on a metal-cutting machine after turning or milling under lubrication and cooling conditions using the machine’s cutting fluid (CF). However, the use of CF raises economic, environmental, and health concerns [51]. Indeed, the CF can account for up to 17% of total production cost [52], rising to almost 20% for difficult-to-cut alloys [53]. In addition, the cost of recycling used CF is two to four times more expensive than purchasing new fluid [54]. Its effect on the environment is also a significant concern, since even purified CF can contaminate rivers, lakes, air, and groundwater [51]. However, the most serious issue is the health risk associated with CF and its mist, which includes skin infections, respiratory diseases, and cancers [55,56]. Addressing the problems caused by CF usage is essential for the development of sustainable manufacturing [57,58]. In the context of DB, this refers to the implementation of dry DB (i.e., without the use of CF) [59,60], cool-assisted DB [61,62], or cryogenic-assisted DB [63,64]. Several reviews have summarised the effects of cryogenic- and cool-assisted DB on the SI and operational performance of metal components [16,65]. Accordingly, assessing the DB of CuZn39Pb3 under different burnishing conditions is of significant interest.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of DB when implemented conventionally (i.e., flood lubricated using CF) and when implemented sustainably (i.e., dry DB and dry + cool-assisted DB). Specifically, it investigates how these processes affect the surface roughness of the CuZn39Pb3 brass alloy. The effectiveness of the different DB processes was assessed using two-dimensional height and shape roughness parameters.

2. Experimental Information

2.1. Organisation of the Study

This study was conducted in four main stages:

- Planned experiments and analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to identify the optimal feed rate, cutting velocity, and cutting depth of each turning process (F, D, and D+C) by minimising the roughness parameter (Ra). All subsequent turning operations (performed before each DB process) were carried out using these optimal values.

- A one-factor-at-a-time approach was used to investigate how certain DB governing factors, including diamond radius, burnishing force, and feed rate, affect Ra. DB was conducted under conventional conditions (i.e., under F conditions); the identified rational range of variations for each governing factor was used to assess the other two DB conditions (D and D+C).

- Planned experiments and regression analyses were used to identify the optimal values of each governing factor for the three DB processes by minimising Ra.

- The optimised DB processes were compared in terms of average Ra, skewness, and kurtosis to evaluate their effectiveness as a sustainable DB method.

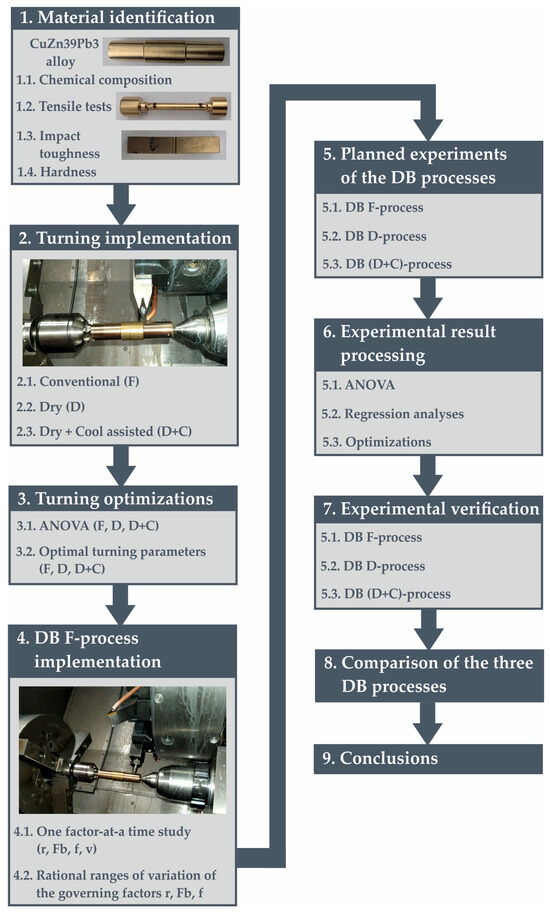

- The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study.

2.2. Materials

A hot-rolled CuZn39Pb3 R430 cylindrical brass bar was received and used as is. The chemical composition of the bar (wt%) was measured using a Spectrolab LAS01 optical emission spectrometer (SPECTRO Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany). The tensile strength, yield limit, and elongation of the alloy were obtained from three room-temperature tests on a ZD20 universal testing machine (Germany); the measurements were arithmetically averaged to obtain a final result. Impact toughness was measured with a KM-30 Charpy impact tester (SU) at 300 J. Hardness was determined with a VEB-WPM tester (WPM Werkstoffprüfsysteme Leipzig GmbH, Markkleeberg, Germany) using a 2.5 mm spherical indenter, 62.5 kg load, and 10 s holding time; seven measurements were recorded and arithmetically averaged.

2.3. Turning Implementation

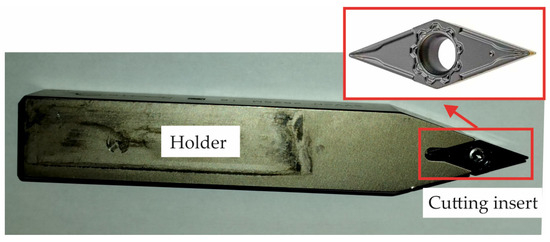

Turning was performed on an Index Traub CNC lathe (Esslingen am Neckar, Germany) under three cutting conditions: (1) flood lubrication (F) using Vasco 6000 lubricant; (2) dry conditions (D); and (3) dry + cool-assisted conditions (D+C) using a custom vortex-tube cold-air nozzle (Emuge-Franken, Germany). The experimental setup involved VCMT 160404–F3P carbide cutting inserts with a main back angle and radius at the tool tip of 0.4 mm, as well as an SVVCN 2525M-16 holder with main and auxiliary mounting angles of and , respectively (Figure 2). Each turning process used a freshly run insert (run for several minutes) to ensure uniform wear conditions.

Figure 2.

Holder and cutting insert used.

2.4. DB Implementation

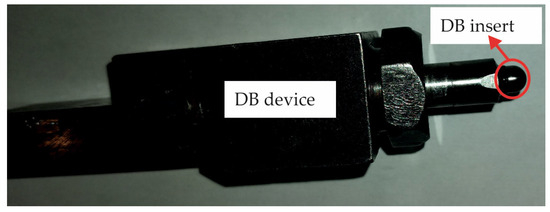

Turning and DB were carried out in a single clamping process. The burnishing tool ensures elastic normal contact between the deforming diamond insert and the treated surface (Figure 3). DB was implemented using spherical-ended polycrystalline diamond inserts under three types of burnishing conditions: (1) flood lubrication (F); (2) dry conditions (D); and (3) dry + cool-assisted conditions (D+C).

Figure 3.

DB device.

2.5. Measurement of SI Characteristics

Two-dimensional roughness parameters were measured using a Mitutoyo Surftest SJ-210 surface roughness tester (Kawasaki, Japan). Results are reported as the arithmetic mean of six evenly spaced sample generatrices.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Material Characterisation

The chemical composition of the CuZn39Pb3 alloy is presented in Table 1. The remaining elements were As, B, Bi, Co, S, Mg, Be, and Se (all elements sum to 100 wt%). The main mechanical characteristics of the alloy are as follows: a yield limit of 298 (±4) MPa, a tensile strength of 408 (±7) MPa, 6.75 (±1)% elongation, an impact toughness of , and a hardness of 136 (±4) HB.

Table 1.

Chemical composition (in wt%) of the used CuZn39Pb3 alloy.

3.2. Turning Process Optimisation

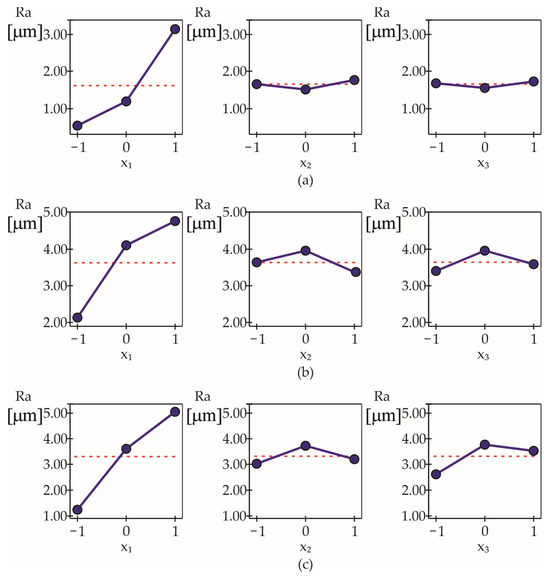

The governing factors of the turning processes, including feed rate f, cutting velocity , and cutting depth , their values, and the experimental results are presented in Table 2. The objective function used in the study was the Ra roughness parameter. An optimal second-order compositional design, also known as a Bm-type design and developed by Andrukovich et al. [66], was used. A central point is not recommended for more than two factors. The optimal compositional design was developed based on the Box and Wilson design [67], in which only a few more trials are added to the full factorial experiment. ANOVA was performed using the QStatLab software, v.6.1.1.3 [68]. Table 3 presents ANOVA results computed by QStatLab for the turning processes, and Figure 4 illustrates the degree of influence that each factor had on Ra. Feed rate was found to be the most significant factor, while the cutting velocity and depth had a significantly smaller influence on Ra. This trend was most pronounced in turning processes conducted under F conditions.

Table 2.

Governing factors, levels, experimental design, and roughness results.

Table 3.

Computed ANOVA results for the turning processes.

Figure 4.

ANOVA main effects in turning: (a) F-process; (b) D-process; (c) (D+C)-process.

All subsequent turning processes were performed with a feed rate of 0.05 mm/rev, a cutting velocity of 180 m/min, and a cutting depth of 1 mm in order to minimise Ra (Table 2, seventh experimental point).

3.3. DB Parametric Study

The main requirement of any burnishing process is the significant reduction in surface roughness. This section examines the effects of the main governing factors of DB on Ra, the most widely used roughness height parameter. The aim is to explore the factor space and identify rational ranges for the input variables (i.e., governing factors) of the DB process, which will be applied in subsequent planned experiments.

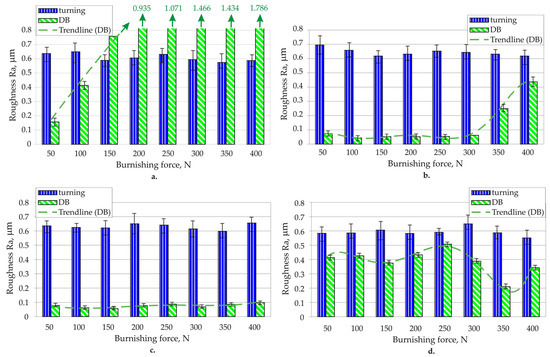

3.3.1. Effect of the Diamond Radius and Burnishing Force

The feed rate and burnishing velocity were held constant at 0.05 mm/rev and 80 m/min, respectively. During the DB process, the combination of diamond insert radius and burnishing force determines the penetration depth, i.e., the depth of the plastically deformed metal layer. There is a direct correlation between the depth of this layer and the smoothing effect. Therefore, the first stage of the parametric study focused on defining the rational ranges for the diamond insert radius and burnishing force, as both factors strongly influence Ra (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of diamond radius and burnishing force on roughness parameter Ra: (a) r = 2 mm; (b) r = 3 mm; (c) r = 4 mm; (d) r = 5 mm (f = 0.05 mm/rev; v = 80 m/min).

A 2 mm radius was found to be unsuitable for this alloy except for the combination of r = 2 mm and burnishing force of 50 N, which resulted in an average Ra of 0.156 μm (Figure 5a). Burnishing forces above 100 N significantly worsened the initial post-turning roughness. Larger radii (3, 4, and 5 mm) reduced the initial roughness of all burnishing force values tested. The 3 mm radius produced Ra values from 0.044 to 0.073 μm for forces up to 300 N, but increasing the force to 400 N caused Ra to rise sharply to 0.436 μm (Figure 5b). The 4 mm radius exhibited the most stable performance, maintaining an average Ra below 0.1 μm across all burnishing forces (Figure 5c). The largest radius, 5 mm, also reduced initial roughness but yielded a wide range of Ra values (0.209–0.508 μm) depending on the magnitude of the burnishing force; no clear trends were identified (Figure 5d). Based on these results, diamond insert radii of 3 and 4 mm and a burnishing force range of 100–400 N were selected for the planned experiments.

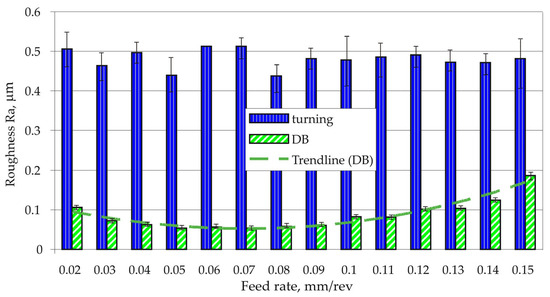

3.3.2. Effect of Feed Rate

The diamond radius, burnishing force, and burnishing velocity were held constant at 3 mm, 250 N, and 80 m/min, respectively. A consistent trend in Ra as a function of feed rate was observed (Figure 6). Specifically, when the feed rate was varied between 0.03 and 0.11 mm/rev, the Ra remained below 0.1 µm, reaching a minimum near the middle of this interval; feed rates beyond this range were found to degrade Ra. These results are qualitatively consistent with the theoretical formula for roughness when f > 0.07 mm/rev [69]. Lower feed rates increased the cyclic loading coefficient defined by Maximov et al. [70]; this explains the observed deterioration in roughness at very low feed rates.

Figure 6.

Effect of feed rate on roughness parameter Ra (r = 3 mm; ; v = 80 m/min).

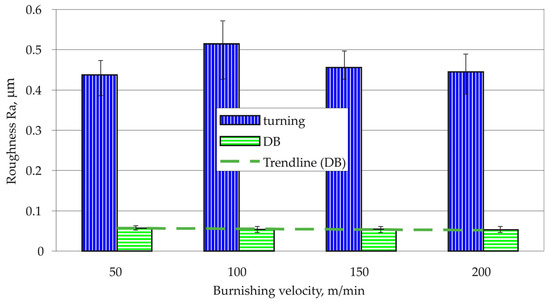

3.3.3. Effect of Burnishing Velocity

The diamond radius, burnishing force, and feed rate were held constant at 3 mm, 250 N, and 0.07 mm/rev, respectively. When the burnishing velocity was varied between 50 and 200 m/min, the Ra values remained relatively constant, with only a slight downward trend (Figure 7). High burnishing velocities are known to result in the thermal softening of the surface layer [71,72]; however, finite element simulations [72] have shown that this effect can be ignored at velocities below 100 m/min. Accordingly, all subsequent DB processes were conducted at a burnishing velocity of 80 m/min.

Figure 7.

Effect of burnishing velocity on roughness parameter Ra (r = 3 mm; ; f = 0.07 mm/rev).

3.4. DB Optimisation

The input variables (governing factors) and their levels (numerical values chosen based on the results obtained in Section 3.3) are shown in Table 4. The relationship between the natural and dimensionless variables is defined by Equation (1):

where and are the mean and maximum value of the natural variable, respectively.

Table 4.

Governing factors and levels.

A plan synthesised as a superposition of two second-order optimal composition plans (in terms of burnishing force and feed rate) with centre points included was used. The plan was extended (Table 5) with the radius of the diamond insert, which varies in two levels and can only take integer values. The objective function was the average roughness . The experimental results obtained for the three DB processes are presented in Table 4. The initial roughness values (i.e., the surface roughness after the turning process) are a measure of the stability of the turning process (all three processes were performed using the optimal values obtained in Section 3.2). For turning processes obtained under F conditions (turning F-process), the arithmetic mean of Ra was 0.461 μm with deviations of +0.022 μm and −0.036 μm, while the other two processes, D and D+C, exhibited surface roughnesses of 1.971 μm (+0.453 μm and −0.616 μm) and 1.768 μm (+0.525 μm and −0.794 μm), respectively. These deviations are roughly one order of magnitude greater than for the F-process, while the average Ra of the F-process is approximately four times smaller than that obtained by the turning D- and D+C-processes.

Table 5.

Experimental plan and results.

The turning F-process results in surfaces with a roughness (Ra = 0.461 μm) that is fully comparable to those obtained by some finishing processes like grinding, while the sustainable turning D- and D+C-processes require subsequent finishing. Consequently, the 100% machinability index assigned to CuZn39Pb3 leaded brass is only valid under flood lubrication conditions.

The DB D- and D+C-processes achieve Ra values of 0.063 μm (14th experimental point in Table 4) and 0.087 μm (15th experimental point in Table 4), respectively; these are comparable to roughnesses obtained by the DB F-process. Furthermore, the reduction in the initial roughness achieved by the SB D- and D+C-processes is several times greater than the reduction achieved by the DB F-process. These results demonstrate the potential of DB as a cheap, effective, and reliable finishing process for CuZn39Pb3 alloys.

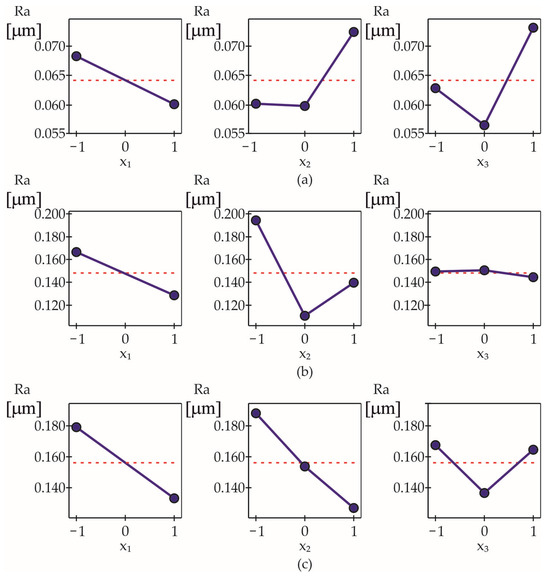

The impacts of the governing factors were obtained using ANOVA conducted in QStatLab. Table 6 presents the computed ANOVA results for the DB processes and Figure 8 visualises the main effects. In all three DB processes, diamond inserts with larger radii (r = 4 mm) resulted in reduced roughness; this was most pronounced in the DB D+C-process. In the DB F-process, the feed rate had the strongest influence on Ra, followed by the burnishing force. In the sustainable DB processes (D and D+C), the burnishing force had the strongest influence on Ra, followed by diamond radius. Notably, the influence of feed rate was negligible in the DB D-process. The highest Ra obtained during the DB F-process occurred when the maximum burnishing force was used, while the highest Ra obtained during the two sustainable DB processes occurred when the minimum burnishing force was used.

Table 6.

Computed ANOVA results for DB processes.

Figure 8.

ANOVA main effects in DB: (a) F-process; (b) D-process; (c) (D+C)-process.

In conclusion, in the DB F-process, Ra is minimised by combining a large diamond radius with moderate burnishing force and feed rates. In the DB D-process, the lowest Ra occurs with a large radius, maximum feed rate, and moderate burning force. Finally, in the DB D+C-process, the minimum Ra is obtained when both radius and force are at their maximum values while the feed rate is intermediate. It should be noted that ANOVA results are primarily qualitative, as they are based solely on the experimental data points.

These qualitative relationships were obtained using second-order regression models fitted to the data using QStatLab. Second-order polynomials were used since the governing factors were tested at three levels:

where is the vector of the governing factors , .

The polynomial coefficients of the developed roughness models are presented in Table 7. The coefficient is omitted because the diamond insert radius was varied at only two levels, which, by definition, has a linear effect on surface roughness. The model-predicted values of the Ra roughness parameter at the experimental points are listed in Table 5. The results obtained from the model were relatively consistent with the experimental data.

Table 7.

Regression coefficients in the Ra roughness models.

Statistical analysis of the regression models was performed using QStatlab. The critical values of the Student statistic (T), Fisher statistic (F), residual standard deviation (ResStDev), determination coefficient (R-sq), and adjusted determination coefficient (Radj-sq) [68] for the three models are shown in Table 8. The results confirm the adequacy of the models. The probability of a coefficient being insignificant is p > 0.05. However, such coefficients are also included in the models to minimise the residual (exp−model).

Table 8.

Results of statistical analysis of regression models.

The magnitude of the dimensionless coefficients and reflects the degree of influence (i.e., significance) of each factor: larger values correspond to stronger effects. The polynomial coefficients and in Table 7 are fully consistent with the ANOVA solutions.

The absolute values of the coefficients () describe the strength of the interactions between each factor. In the DB F-process, the largest coefficient involves the diamond radius and burnishing force; the combination of these two physical variables determines the penetration depth, which is an independent physical variable. Consequently, this variable can be used as a governing factor when using DB devices with a hard, normal contact between the deforming element and the machined surface. The coefficient (the interaction between the radius and feed rate) has a negligible magnitude, hence its omission from the roughness model. Physically, this interaction is associated with the formation of theoretical roughness (see Section 3.3.2) and the cyclic loading coefficient [68]. As discussed in Section 3.3.2, the feed rate qualitatively satisfies the theoretical roughness relationship only in the upper half of its variation range. The cyclic loading coefficient, which reflects the accumulation of plastic strain [73], also remains small due to the limited plasticity of the CuZn39Pb3 alloy (the measured elongation was only 6.75%; see Section 3.1). These observations validate the weak correlation between radius and feed rate as predicted by the regression model.

In both sustainable DB processes (D and D+C), the interaction between the radius and feed rate possesses the smallest magnitude, indicating that it has the weakest relationship (coefficient in Table 7). In contrast, the interaction between burnishing force and feed rate is the strongest (coefficient has the largest magnitude); this effect is more pronounced in the DB D-process. This stronger coupling arises from the greater heat generated during dry friction, resulting in a softening effect [16].

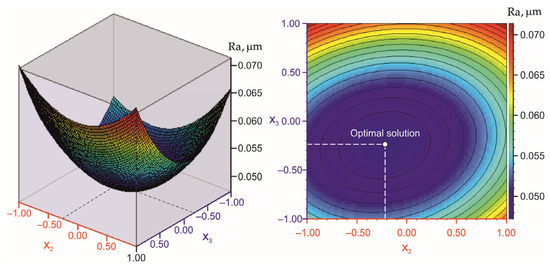

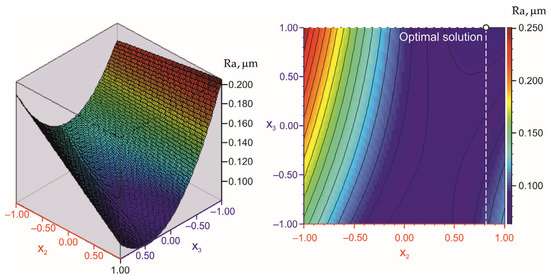

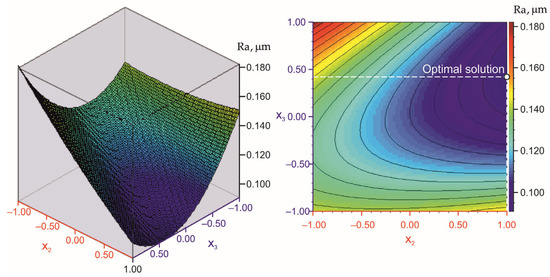

The three DB processes were optimised by identifying the minima of the corresponding models without applying any parametric or functional constraints. The analyses were performed using QStatLab and a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II [74]. The optimal sizes of the governing factors and the minimum Ra values are presented in Table 9 and are consistent with the ANOVA results. Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the optimal solutions for the three DB processes; in all cases, the radius r of the diamond insert is 4 mm or .

Table 9.

Optimal values of the governing factors and objective function.

Figure 9.

Ra model and optimal solution visualisation in DB F-process at r = 4 mm.

Figure 10.

Ra model and optimal solution visualisation in DB D-process at r = 4 mm.

Figure 11.

Ra model and optimal solution visualisation in DB (D+C)-process at r = 4 mm.

3.5. Analysis of the Roughness Parameters Obtained via Optimised DB Processes

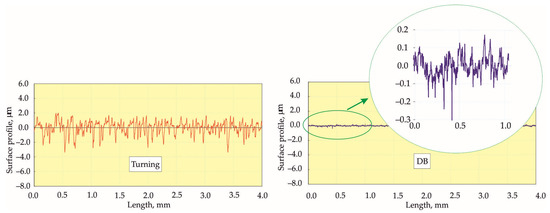

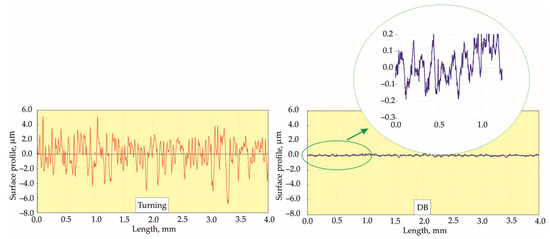

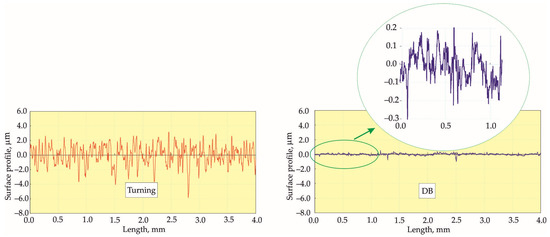

Twenty samples were processed for each DB process using their corresponding optimal governing factors in order to assess the stability of the obtained Ra values. All turning processes were performed under identical conditions. One sample from each group was selected; the selected sample possessed an Ra value that was closest to the arithmetic mean of its respective group. Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14 compare the roughness profiles after the turning process (left) and after the DB process for each of the three selected samples.

Figure 12.

Roughness profiles obtained through turning and DB F-processes.

Figure 13.

Roughness profiles obtained through turning and DB D-processes.

Figure 14.

Roughness profiles obtained through turning and DB (D+C)-processes.

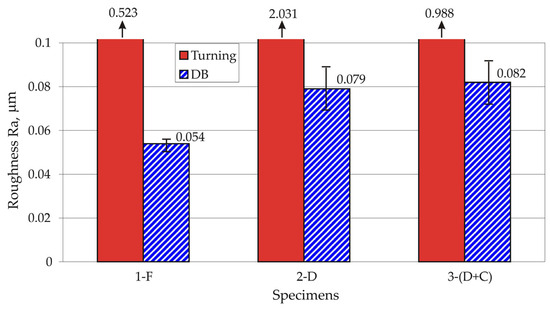

The turning F-process (Figure 12) produced the smallest peak-to-valley distances, followed by the turning D+C-process. All three DB processes exhibited similar surface roughness microprofiles, with a significant reduction in the roughness height parameters. Figure 15 compares the Ra values, while Table 10 lists selected roughness parameters associated with the height, shape, and the Rk group for the three representative samples. The DB D-process achieved the greatest reduction in Ra from 2.031 μm to 0.079 μm (a 25.7-fold decrease), while the DB F- and D+C-processes reduced Ra values by 9.68 and 12.05 times, respectively. The significant decrease in Ra observed in the DB D-process is attributed to the high heat generated, which results in a softening effect [16]. Conversely, the DB D+C-process was carried out under the lowest temperature conditions (the surface temperature in the area immediately surrounding the diamond-workpiece contact is approximately −20 °C when using a vortex tube [75]), leading to increased surface microhardness [76] and thus a shallower penetration depth when using a DB device with an elastic normal contact.

Figure 15.

Ra roughness parameter obtained through different processes.

Table 10.

Two-dimensional roughness parameters obtained through different DB processes.

Studies have shown that roughness shape parameters, such as skewness and kurtosis, directly influence the tribological performance of the surface–counterbody pair under boundary lubrication regimes [50]. Specifically, negative skewness and a kurtosis greater than three are indicative of improved wear resistance under boundary lubrication regimes [77]. The deep valleys act as micro-reservoirs for the lubricant, thus improving the tribological behaviour of the friction pair. The DB F- and D+C-processes can produce this combination. However, negative skewness can adversely affect fatigue behaviour, as the deep valleys in the roughness profile act as stress concentrators, leading to a reduction in fatigue strength [78].

Since the correlation between SI and component performance is well established [50], it is not possible to predict how the three DB processes will affect the operating behaviour of a machined CuZn39Pb3 part based solely on roughness data. Detailed investigations are required to understand how these processes influence the mechanical and physical properties of the SI and the underlying microstructure, which ultimately determines surface and near-surface behaviour. These issues will be addressed in future studies.

4. Conclusions

CuZn39Pb3 brass alloys are widely used in machining; however, there has been a lack of research on how surface coldworking affects roughness. This study addresses this gap by evaluating three optimised finishing processes: turning followed by DB performed under F, D, and D+C conditions. The influence of these processes on the roughness parameters was examined, and the following new findings were obtained:

- The three processes (F, D, and D+C) achieve mirror-like surfaces with a minimum average Ra of 0.054 µm, 0.079 µm, and 0.082 µm, respectively.

- The F- and D+C-processes exhibit surface roughness profiles with negative skewness and a kurtosis greater than three, indicating improved wear resistance in boundary lubrication regimes.

- The D- and D+C-processes are far more sustainable than the F-process because they eliminate the environmental and health hazards associated with cutting fluid used in the latter process.

- Across all turning processes (F, D, and D+C), the feed rate was the dominant factor affecting Ra; cutting velocity and depth have comparatively minor effects. For all three turning processes, the optimal parameters that minimised Ra were a feed rate of 0.05 mm/rev, a cutting velocity of 180 m/min, and a cutting depth of 1 mm.

- In all three DB processes, a larger diamond insert radius reduced roughness; this effect was most pronounced in the D+C-process. In the DB F-process, the feed rate had the strongest influence on Ra, followed by the burnishing force. In both sustainable DB processes (D and D+C), the burnishing force had the strongest influence on roughness, followed by diamond radius. The influence of feed rate was negligible in the DB D-process.

- The DB D-process achieved the greatest reduction in Ra from 2.031 μm to 0.079 μm (a 25.7-fold decrease). In contrast, the DB F- and D+C-processes reduced Ra by 9.68 and 12.05 times, respectively. The significant reduction in Ra during the DB D-process was attributed to the larger amount of heat generated, which results in a softening effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A. and M.I.; methodology, K.A. and M.I.; software, M.I., P.D., and V.T.; validation, M.I. and K.A.; formal analysis, K.A. and M.I.; investigation, K.A., P.D., M.I., and V.T.; resources, K.A. and M.I.; data curation, V.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.I., P.D., and V.T.; writing—review and editing, K.A. and M.I.; visualisation, M.I. and P.D.; supervision, K.A.; project administration, M.I.; funding acquisition, K.A. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Regional Development Fund under the Operational Programme “Scientific Research, Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation 2021–2027”, Project CoC “SmartMechatronics, Eco- and Energy Saving Systems and Technologies”, BG16RFPR002-1.014-0005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| CF | Cutting fluid |

| D | Dry |

| D+C | Dry and cool-assisted |

| DB | Diamond burnishing |

| F | Flood lubrication |

| SCW | Surface coldworking |

| SI | Surface integrity |

References

- Vaxevanidis, N.M.; Fountas, N.A.; Koutsomichalis, A.; Kechagias, J.D. Experimental investigation of machinability parameters in turning of CuZn39Pb3 brass alloy. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 10, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountas, N.; Koutsomichalis, A.; Kechagias, J.D.; Vaxevanidis, N.M. Multi–response optimization of CuZn39Pb3 brass alloy turning by implementing Grey Wolf algorithm. Fract. Struct. Integr. 2019, 50, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.; Marre, M. Forging of Zinc Alloys—A Feasibility Study. Eng. Proc. 2022, 26, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jasper, S.; Subash, R.; Muthuneelakandan, K.; Vijayakumar, D.; Jhansi Ida, S. The Mechanical Properties of Brass Alloys: A Review. Eng. Proc. 2025, 93, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Consolidated Text: Directive 2011/65/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2011 on the Restriction of the Use of Certain Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment (Recast) (Text with EEA Relevance). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/65/2025-01-01 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- A Regulation of the European Union, Adopted to Improve the Protection of Human Health and the Environment from the Risks That can be Posed by Chemicals, While Enhancing the Competitiveness of the EU Chemicals Industry. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/regulations/reach/understanding-reach (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Jablonski, M. Examination of the force parameters in drawing process of CuZn39Pb3 cast rod using selected lubricants. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2023, 4, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.M.; Abd, O.I. Influence of Al and Ti Additions on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Leaded Brass Alloys. Indian J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 2014, 909506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinksmeier, E.; Preuss, W.; Riemer, O.; Rentsch, R. Cutting forces, tool wear and surface finish in high speed diamond machining. Precis. Eng. 2017, 49, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultheiss, F.; Johansson, D.; Bushlya, V.; Zhou, J.; Nilsson, K.; Ståhl, J.-E. Comparative study on the machinability of lead-free brass. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükömeroğlu, T.; Kara, L. The friction and wear properties of CuZn39PB3 alloys under atmospheric and vacuum conditions. Wear 2014, 309, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostis, I.; Pantazopoulos, G.A.; Pairetis, A.S. Fracture behaviour and characterization of lead-free brass alloys for machining applications. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 23, 3193–3206. [Google Scholar]

- Klocke, F.; Nobel, C.; Veselovac, D. Influence of tool coating, tool material, and cutting speed on the machinability of low-leaded brass alloys in turning. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobel, C.; Klocke, F.; Lung, D.; Wolf, S. Machinability enhancement of lead-free brass alloys. Proc. Cirp 2014, 14, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazopoulos, G.; Vazdirvanidis, A. Failure analysis of a fractured leaded-Brass (CuZn39Pb3) extruded hexagonal rod. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2008, 8, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V. Effects of diamond burnishing on surface integrity, fatigue, wear, and corrosion of metal components—Review and perspectives. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 139, 4233–4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaster, H.J. A tribute to Benjamin Chew Tilghman. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Shot Peening, Oxford, UK, 13–17 September 1993; pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lawerenz, M. Shot Peening and its Effect on Gearing. In SAE Technical Paper 841090; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.M.; Her, Y.C.; Han, N.; Clauer, A. Laser shock peening on fatigue behavior of 2024-T3 Al alloy with fastener holes and stopholes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2001, 298, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Cavitation peening: A review. Metals 2020, 10, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyama, H. Oxidation-induced stacking faults introduced by using a cavitating jet for gettering in silicon. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 1999, 3, 93–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, T.; Wu, T.; Sun, F.; Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Niendorf, T. Influence of surface attrition treatment (SMAT) on microstructure, tensile and low-cycle fatigue behaviour of additively manufactured stainless steel 316L. Metals 2022, 12, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galda, L.; Koszela, W.; Pawlus, P. Surface geometry of slide bearings after percussive burnishing. Tribol. Int. 2007, 40, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoroll Catalogue. Tools and Solutions for Metal Surface Improvement; Ecoroll Corporation Tool Technology: Milford, OH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Saldana-Robles, A.; De la Pena, J.A.D.; Balvantin, A.; Aguilera-Gomez, E. Ball-burnishing process: State of the art of a technology in development. Dyna 2017, 92, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Klumpp, A.; Hoffmeister, J.; Schulze, V. Mechanical surface treatments. In Proceedings of the Conf proc 2014: ICSP-12 Goslar, Goslar, Germany, 15–18 September 2014; pp. 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Duncheva, G.V.; Maximov, J.T.; Dunchev, V.P.; Anhev, A.P.; Atanasov, T.P.; Capec, J. Single toroidal roller burnishing of 2024-T3 Al alloy implemented as mixed burnishing process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 3559–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, M. Slide Diamond Burnishing. In Nonconventional Finishing Technologies; Korzynski, M., Ed.; Polish Scientific Publisher: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shiou, F.J.; Chen, C.H. Determination of optimal ball-burnishing parameters for plastic injection moulding steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2003, 21, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.C.; Wang, S.W.; Lai, H.Y. The relationship between surface roughness and burnishing factor in the burnishing process. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2004, 23, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V. Finite Element Analysis and optimization of spherical motion burnishing of low-alloy steel. Proc. IMechE Part. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2012, 226, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, M. Modeling and experimental validation of the force-surface roughness relation for smoothing burnishing with a spherical tool. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2007, 47, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, E.H.; Nerad, A.J. Irregular Diamond Burnishing Tool. United States Patent 2966722, 3 January 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczylas, A.; Zaleski, K.; Matuszak, J. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Surface Defect Removal by Slide Burnishing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P. Smoothing, deep or mixed diamond burnishing of low-alloy steel components—Optimization procedures. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 1917–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunchev, V.P. Comprehensive model of the micro-hardness of diamond burnished 41Cr4 steel specimens. J. Tech. Univ. Gabrovo 2020, 60, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kebede, F.T.; Felho, C.; Sztankovics, I. Improving Surface Roughness of 42CrMo4 Low Alloy Steel Shafts by Applying Varying Feed in the Multi-Pass Slide Burnishing Process. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobola, D.; Kania, B. Phase composition and stress state in the surface layers of burnished and gas nitrided Sverker 21 and Vanadis 6 tool steels. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 353, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Argirov, Y.B. Effect of Diamond Burnishing on Fatigue Behaviour of AISI 304 Chromium-Nickel Austenitic Stainless Steel. Materials 2022, 15, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzynski, M.; Dudek, K.; Kruczek, B.; Kocurek, P. Equilibrium surface texture of valve stems and burnishing method to obtain it. Tribol. Int. 2018, 124, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labanowski, J.; Ossowska, A. Influence of burnishing on stress corrosion cracking susceptibility of duplex steel. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2006, 19, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Argirov, Y.B.; Nikolova, M.P. Effects of heat treatment and diamond burnishing on fatigue behaviour and corrosion resistance of AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolnicki, S.; Varga, G. Analysis of Surface Roughness of Diamond-Burnished Surfaces Using Kraljic Matrices and Experimental Design. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toboła, D.; Morgiel, J.; Maj, Ł. TEM analysis of surface layer of Ti-6Al-4V ELI alloy after slide burnishing and low-temperature gas nitriding. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 515, 145942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Ganev, N.; Duncheva, G.V.; Selimov, K.F. Effect of slide burnishing basic parameters on fatigue performance of 2024-T3 high-strength aluminium alloy. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2017, 40, 1893–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Anchev, A.P.; Duncheva, G.V.; Ganev, N.; Selimov, K.F.; Dunchev, V.P. Impact of slide diamond burnishing additional parameters on fatigue behaviour of 2024-T3 Al alloy. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2019, 42, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncheva, G.V.; Maximov, J.T.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P.; Argirov, Y.B. Multi-objective optimization of internal diamond burnishing process. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2022, 37, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Zhoung, Q. Investigation of the burnishing process with PCD tool on non-ferrous metals. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2005, 25, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.; Duncheva, G.; Anchev, A.; Dunchev, V.; Argirov, Y. Improvement in Fatigue Strength of Chromium–Nickel Austenitic Stainless Steels via Diamond Burnishing and Subsequent Low-Temperature Gas Nitriding. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V. The correlation between surface integrity and operating behaviour of slide burnished components—A review and prospects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, D.P.; Hii, W.W.-S.; Michalek, D.J.; Sutherland, J.W. Examining the role of cutting fluids in machining and efforts to address associated environmental/health concerns. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2006, 10, 23–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klocke, F.; Eisenblätter, G. Dry cutting. CIRP Ann. 1997, 46, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokrani, A.; Dhokia, V.; Newman, S.T. Environmentally conscious machining of difficult-to-machine materials with regard to cutting fluids. Int. J. Mach. Tool. Manuf. 2012, 57, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Reddy, M.M.; Yi, Q.S. Environmental friendly cutting fluids and cooling techniques in machining: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, P.; Wilhelm, D.; Maibach, H.I. Irritant Contact Dermatitis irritant contact dermatitis and aging. Contact Dermat. 1990, 23, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackerer, C.R. Health effects of oil mists: A brief review. Toxicol. Ind. Health 1989, 5, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Kishawy, H.A. Sustainable Manufacturing and Design: Concepts, Practices and Needs. Sustainability 2012, 4, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yan, Y.; Cui, J.; Geng, Y.; Sun, T.; Luo, X.; Zong, W. Recent advances in design and preparation of micro diamond cutting tools. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 062008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huuki, J.; Laakso, S.V.A. Surface improvement of shafts by the diamond burnishing and ultrasonic burnishing techniques. Int. J. Mach. Mach. Mater. 2017, 19, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swirad, S. The surface texture analysis after slide burnishing with cylindrical elements. Wear 2011, 271, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Le, V.A.; Nguyen, T.T. Artificial neural network-based optimization of the cryogenic-internal diamond burnishing process in tems of surface quality. HaUI J. Sci. Technol. 2024, 60, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Van, A.L.; Nguyen, T.T. Machine Learning-Based Optimization of Diamond Burnishing Parameters in Terms of Energy Efficiency and Quality Indexes. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 9339–9363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin, B.; Narendranath, S.; Chakradhar, D. Experimental evaluation of diamond burnishing for sustainable manufacturing. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 106514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachin, B.; Narendranath, S.; Chakradhar, D. Effect of cryogenic diamond burnishing on residual stress and microhardness of 17-4 PH stainless steel. Mater. Today 2018, 5, 18393–18399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V. Effects of Cryogenic—And Cool-Assisted Burnishing on the Surface Integrity and Operating Behaviour of Metal Components: A Review and Perspectives. Machines 2024, 12, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrukovich, P.F.; Golikova, T.I.; Kostina, S.G. Second-order designs on a hypercube with properties close to D-optimal ones. In Collection: New Ideas in Experimental Planning; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1969. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Box, G.E.P.; Wilson, K.B. On the Experimental Attainment of Optimum Conditions. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1951; Volume 13, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Vuchkov, I.N.; Vuchkov, I.I. QStatLab Professional, version 6.1.1.3; Statistical Quality Control Software, User’s Manual; QStatLab: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nestler, A.; Schubert, A. Effect of machining parameters on surface properties in slide diamond burnishing of aluminium matrix composites. Mater. Today Proc. 2015, 2S, S156–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Ganev, N.; Dunchev, V.P. Effect of cyclic hardening on fatigue performance of slide burnishing components made of low-alloy medium carbon steel. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2019, 42, 1414–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.; Smolin, I.; Skorobogatov, A.; Akhmetov, A. Finite element simulation and experimental investigation of nanostructuring burnishing AISI 52100 steel using an inclined flat cylindrical tool. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Dunchev, V.P.; Anchev, A.P. Different strategies for finite element simulations of static mechanical surface treatment processes—A comparative analysis. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, V.P.; Smolin, I.Y.; Dmitriev, A.I.; Tarasov, S.Y.; Gorgots, V.G. Toward control of subsurface strain accumulation in nanostructuring burnishing on thermostrengthened steel. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 285, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Pratap, A.; Agarwal, S.; Meyarivan, T. A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2002, 6, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.; Duncheva, G.; Anchev, A.; Dunchev, V.; Anastasov, K.; Argirov, Y. Sustainable Diamond Burnishing of Chromium–Nickel Austenitic Stainless Steels: Effects on Surface Integrity and Fatigue Limit. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahir, I.S.; Attia, H.; Biermann, D.; Duflou, J.; Klocke, F.; Meyer, D.; Newman, S.T.; Pusavec, F.; Putz, M.; Rech, J.; et al. Cryogenic manufacturing processes. CIRP Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2016, 65, 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, M.; Podgornik, B.; Vizintin, J. Correlation between standard roughness parameters skewness and kurtosis and tribological behaviour of contact surface. Tribol. Int. 2012, 48, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximov, J.T.; Duncheva, G.V.; Anchev, A.P.; Dunchev, V.P. Explicit correlation between surface integrity and fatigue limit of surface cold worked chromium-nickel austenitic stainless steels. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 6041–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).