Abstract

Blood Flow Restriction (BFR) training has gained growing attention in musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Effects of resistance training with and without BFR on lower-limb muscle activation were analyzed in a crossover study including 8 subjects (27.5 ± 4.8 years) engaged in regular CrossFit® training. Two 48 h-separated sessions (high bar back squat), with BFR (80% of individualized arterial occlusion pressure) and without BFR, were performed in a randomized order. Muscle activation (vastus lateralis, vastus medialis (VM), gluteus maximus (GM) and biceps femoris) was electromyographically recorded. The average electromyographic activity of the first four repetitions of the first set (T1), and the last four of the final set (T2) were considered, and intra- and inter-group comparisons were calculated. Pain (VAS) and fatigue (Borg scale) were recorded. Significant differences between BFR and non-BFR conditions were observed only for T1 peak BF activation values. Within the BFR experiments, no significant differences in EMG activation were detected between T1 and T2. In contrast, within the non-BFR experiments, T1 values were statistically significant higher (vs. T2) for mean VL, mean VM, peak VM, mean GM and peak GM. Median pain perception was 3.5 (0.75–6.75) and 4.0 (1.25–6.0), and fatigue perception was 8.0 (7.0–8.0) and 7.0 (7.0–8.0), respectively, with and without BFR. In this exploratory study, BFR maintained EMG activation (VM and GM) and suggests a strategy to minimize mechanical load while preserving muscle activation.

1. Introduction

CrossFit® is a training methodology characterized by the performance of constantly varied functional movements at high intensity, integrating cardiovascular, gymnastic, and weightlifting exercises. This modality has proven highly effective for improving overall physical fitness; however, its practice has also been associated with a relatively high incidence of injuries, likely due to the substantial loads and training volumes involved [1]. For instance, a study conducted in Spain reported 143 injuries among 182 practitioners, with an estimated incidence rate of 3.6 injuries per 1000 training hours—most of them of moderate severity and without significant impact on activities of daily living [2]. Male athletes exhibit a significantly higher incidence of injuries compared to female athletes, whereas the presence of supervised coaching is associated with a substantial reduction in injury occurrence [3].

To address this issue, sports physiotherapy and exercise sciences have developed strategies aimed at optimizing performance and recovery while minimizing injury risk. Among these, Blood Flow Restriction (BFR) training has gained growing attention in recent years [4]. This method involves the application of a pneumatic cuff to the proximal portion of a limb to partially restrict blood flow during exercise [4,5].

Beyond clinical and rehabilitative contexts, the application of BFR has also shown promising results in healthy and trained populations. Several studies have demonstrated that BFR can enhance muscle strength and hypertrophy while using substantially lower external loads, thereby reducing mechanical stress on joints and connective tissues without compromising neuromuscular activation [6]. This is particularly relevant for CrossFit® athletes, who frequently perform high-intensity, high-load multi-joint exercises that place considerable mechanical demands on the musculoskeletal system. In this population, BFR could represent a strategy to optimize performance and recovery while mitigating the cumulative load-related injury risk associated with repetitive heavy training.

From a physiological standpoint, BFR induces a hypoxic and metabolically stressful environment, leading to early fatigue of type I muscle fibers and the subsequent recruitment of type II fibers, even when using low external loads (20–40% of one-repetition maximum, 1RM) [7,8,9]. Consequently, it enables adaptations comparable to those achieved with high-intensity training but with reduced mechanical stress on the joints. Evidence shows that BFR enhances muscle hypertrophy and strength gains in both resistance and low-intensity training protocols, such as slow walking [8,9,10]. The most effective outcomes are typically observed in programs incorporating two to three sessions per week, occlusion pressures between 40% and 80%, and exercise protocols consisting of 2–4 sets following a 30-15-15-15 repetition scheme [7].

In clinical contexts, BFR has emerged as an effective tool in musculoskeletal rehabilitation, helping preserve muscle mass and strength in individuals unable to train with heavy loads, such as older adults [11,12,13], postoperative patients [13,14] or those with functional limitations [9,10]. Thus, its use extends beyond performance enhancement, representing a safe and effective adjunct in physiotherapeutic practice [15].

Given its demonstrated benefits, there has been growing interest in the effects of BFR during resistance exercise in recent years. For instance, Jagim et al. [16] analyzed the effects of BFR application to the lower limbs during squat exercise, examining muscle fatigue, blood lactate concentration, heart rate variability, and blood pressure responses. However, existing BFR studies predominantly focus on open-chain movements or single-joint exercises such as knee extensions [17,18], while the neuromuscular adaptation mechanisms induced by BFR during multi-joint and highly complex functional movements—for example, squatting patterns—remain insufficiently characterized and poorly understood [19].

CrossFit® combines high-intensity functional movements with substantial strength demands, frequently incorporating multi-joint exercises such as the squat. Consequently, CrossFit practitioners represent a relevant model for studying neuromuscular responses under conditions of both high mechanical and metabolic stress, where BFR could offer potential performance and injury-prevention benefits.

While most studies provide valuable insights into the acute physiological effects of BFR, they did not assess neuromuscular activation using surface electromyography (EMG). Surface EMG provides a non-invasive method for quantifying muscle activation and analyzing recruitment patterns under varying load conditions [20,21]. Understanding how BFR modulates neuromuscular activation is crucial for optimizing its application in both performance and clinical rehabilitation settings [22].

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to explore, in CrossFit® athletes, the effect of resistance training with partial BFR on lower-limb muscle activation, assessed through surface EMG, and to compare its response with a traditional protocol performed without BFR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A pilot experimental crossover design was implemented following the CONSORT guidelines [23]. Each participant completed two training sessions under different conditions: with BFR and without BFR. Testing sessions were scheduled on different days with a minimum 48-h washout between sessions to minimise carry-over effects. The trial was prospectively registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR; ACTRN12624001430527).

2.2. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Spain) on 2 July 2024 (approval code: 280520243442024). All procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki [24]. Participants received detailed verbal and written information about procedures, expected risks, and benefits, and provided written informed consent prior to any data collection.

2.3. Participants

Participants were recruited by campus announcements at Universidad Europea de Villaviciosa de Odón (Madrid, Spain). Inclusion criteria required participants to be aged 18–40 years and to have engaged in regular CrossFit® training for at least six months. Exclusion criteria included musculoskeletal injury within the previous six months, surgical procedures within the past year, diagnosed metabolic or vascular disorders, and pregnancy.

2.4. Procedures

During the first laboratory visit, baseline data were collected, including age, CrossFit® experience (months), and resting blood pressure. All subsequent procedures were applied to every participant during baseline measurements and familiarization, and repeated as required during each experimental session.

Before starting the training sessions, participants completed a standardized dynamic warm-up including side planks, standing bear crawls, arm circles, high knee raises, and static lunges with trunk rotation.

2.4.1. BFR Device

A BFR cuff designed for controlled vascular occlusion (Akrafit, Herycor, Elche, Alicante, Spain) was used for all participants. The lower limb cuffs measure approximately 82 cm in length and 10.5 cm in width, allowing precise adjustment and monitoring of cuff pressure during exercise. The BFR cuff was applied to the proximal region of the thigh.

2.4.2. Determination of BFR Pressure

Blood pressure was measured with an automated sphygmomanometer at the posterior tibial artery, with the participant positioned supine with the leg relaxed [25,26].

Thigh circumference was measured at the midpoint between the inguinal crease and the proximal border of the patella using a flexible anthropometric tape. Blood pressure and thigh circumference values were entered into a previously validated formula to estimate individualized arterial occlusion pressure:

Limb Occlusion Pressure lower extremity = −3.770 + (0.145 × systolic blood pressure) + (0.728 × diastolic blood pressure) + (2.203 × thigh circunference) [27].

Occlusion for the BFR condition was set at 80% of each participant’s individualized arterial occlusion pressure.

2.4.3. One-Repetition Maximum (1RM) Estimation

Maximal strength for the high-bar back squat was estimated using a Vitruve Encoder® (Vitruve, Madrid, Spain) [28]. Participants performed five repetitions with a standardized cadence; bar velocity data were recorded by the encoder and used to estimate 1RM according to the manufacturer’s validated algorithm.

2.4.4. Surface Electromyography (sEMG)

Muscle activation was recorded using a validated surface electromyography system (mDurance®, mDurance Solutions S.L., Granada, Spain) [29]. Signals were acquired and stored using the manufacturer’s application and web platform; processing and signal-conditioning were performed following the device’s validated pipeline.

Skin sites were shaved, abraded lightly and cleaned with 70% isopropyl alcohol to reduce impedance [30]. Bipolar Ag/AgCl surface electrodes were positioned with the inter-electrode axis parallel to the estimated muscle fibre direction and secured with hypoallergenic adhesive and tape as required to minimise movement artefact.

Signals were band-pass filtered between 20–450 Hz, and RMS values were calculated using a 200 ms moving window. EMG data were normalized to the participant’s MVC, and muscle activation patterns were analyzed using non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF), following the system’s validated procedures to ensure reproducibility [29,31].

Electrode positions were determined following SENIAM recommendations and are described here for replication:

Vastus lateralis (VL): 2 electrodes centre at two-thirds (2/3) of the line from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the lateral border of the patella; orientation parallel to muscle fibres [32] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positioning of the anterior electrodes.

Vastus medialis (VM): 2 electrodes centre at 80% on the line from the ASIS to the joint space anterior to the anterior border of the medial ligament of the knee, orientation parallel to muscle fibres [32] (Figure 1).

For anterior thigh recordings (quadriceps) the reference electrode was placed over the patella (Figure 1).

Gluteus maximus (GM): electrode centre at approximately 50% of the line between the sacral vertebrae and the greater trochanter; orientation parallel to fibre direction [33] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Positioning of the posterior electrodes.

Biceps femoris (BF, long head): electrode centre at 50% of the line from the ischial tuberosity to the lateral epicondyle of the tibia; orientation parallel to fibre direction [32] (Figure 2).

For posterior GM and BF, the reference (ground) electrode was placed over the sacral crest (cresta sacra), as performed in the study protocol.

Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contractions (MVICs) were collected for each target muscle to normalise EMG amplitudes across muscles, participants and conditions. The MVIC procedure was as follows and was applied consistently in every session:

Participants performed three MVIC trials for each muscle. Each trial consisted of a maximal isometric contraction held for 5 s. Participants were given strong verbal encouragement during each trial. A rest interval of 90–120 s was provided between successive MVIC trials for the same muscle.

The MVIC positions used for each muscle were selected based on standard recommendations and replication of commonly used positions in the literature:

Quadriceps (VL and VM): participant seated with hips and knees at 90° flexion; maximal isometric knee extension against a fixed resistance (or dynamometer/manual resistance) was performed.

BF: participant prone with the knee flexed to ~45° and performing maximal isometric knee flexion against manual or fixed resistance.

GM: participant prone, hip extension fixed resistance, often with the knee flexed to 90°.

For normalization the highest mean EMG amplitude obtained during a 1-s window within the 5-s MVIC trials was selected as the MVIC value for that muscle.

2.4.5. Data Processing and Normalization

EMG data were processed following the manufacturer’s validated pipeline: signals were conditioned and stored using the mDurance platform; raw EMG signals were band-pass filtered, rectified and processed to obtain root-mean-square (RMS) amplitude values. For each muscle, EMG amplitudes recorded during exercise were normalized to the MVIC value (highest mean 1-s window across MVIC trials) and expressed as percentage MVIC (%MVIC).

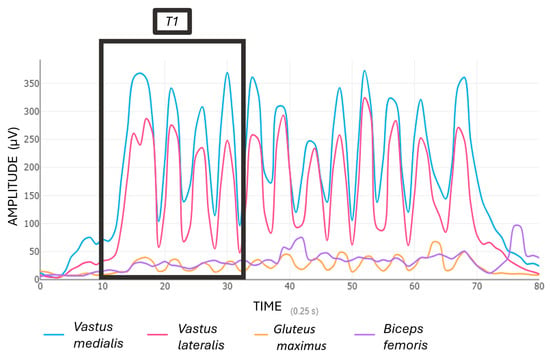

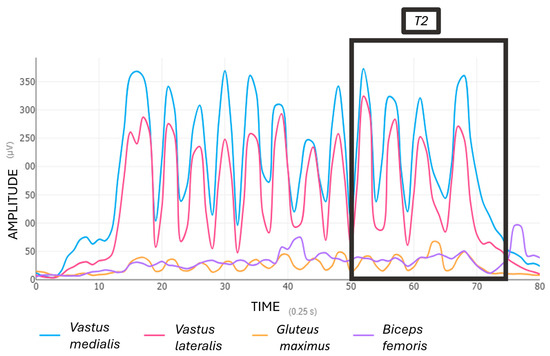

The average of the first four repetitions of the first set (referred to as T1) (Figure 3), and the last four repetitions of the final set (referred to as T2) (Figure 4) were calculated.

Figure 3.

Muscle activation (EMG %MVIC) during the start squat exercise (T1).

Figure 4.

Muscle activation (EMG %MVIC) during the end squat exercise (T2).

2.4.6. Training Protocols

Participants completed both conditions in a randomized and counterbalanced order, performing the same exercise in every session, which was a high bar back squat.

For the BFR condition, pneumatic cuffs were applied to the proximal thighs, and participants performed the squat at 30% of their estimated 1RM. Four sets were completed using a 30–15–15–15 repetition scheme, with 30 s rest between sets, during which the cuffs were deflated and re-inflated immediately prior to the next set [10].

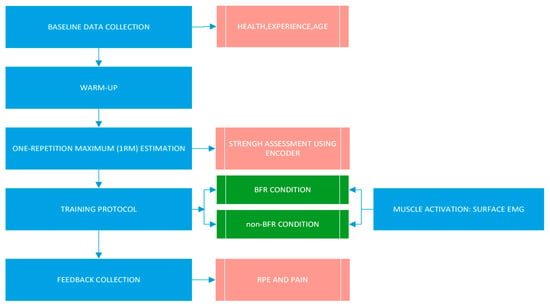

In the non-BFR condition, participants performed the squat at 70% 1RM, completing four sets with 15, 12, and two sets to volitional failure, with 30 s rest between sets [34] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Initial and final positions of the squat exercise.

At the end of each session, participants reported perceived exertion using the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale [35] and perceived pain using a 100 mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Timeline of the experimental procedure.

2.4.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using Jamovi (Version 2.6.44; The jamovi project, 2024). Due to the sample size, median (P25, P75) was used for the description of quantitative variables, and non-parametric tests were applied. Data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare paired measurements between BFR and non-BFR (control) and between T1- and T2- values within experiments. Effect sizes were calculated as r, using the rank-biserial correlation.

Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

The final sample of the study consisted of 8 subjects, all men, aged between 22 and 36 years, with a mean age of 27.5 years (SD = 4.8). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants.

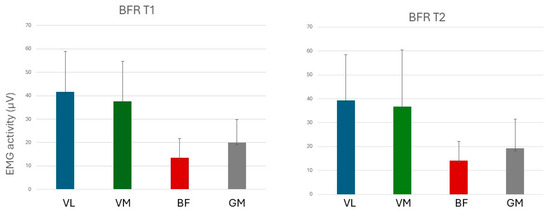

Table 2 shows the electromyographic results (mean and peak values) of muscle activation with and without BFR. In this exploratory analysis, significant differences between BFR and non-BFR conditions were observed only for peak BF activation values. Within the BFR experiments, no significant differences in EMG activation were detected between T1 and T2. In contrast, within the non-BFR experiments, statistically significant differences between T1 and T2 were found for several of the muscles assessed, as shown in the table.

Table 2.

Median (P25, P75) values of electromyographically measured muscle activation in experiments with and without BFR.

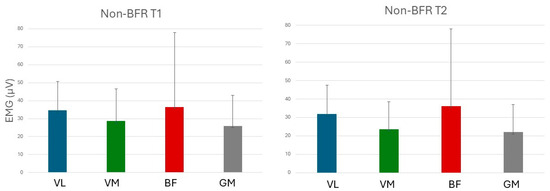

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show mean values of electromyographically measured muscle activation at T1 and T2 in experiments with BFR and non-BFR, respectively.

Figure 7.

Muscular activation in experiments with BFR. VL: Vastus lateralis; VM: Vastus medialis; BF: Biceps femoris; and GM: Gluteus maximus.

Figure 8.

Muscular activation in experiments without BFR. VL: Vastus lateralis; VM: Vastus medialis; BF: Biceps femoris; and GM: Gluteus maximus.

Median (P25, P75) pain perception (VAS) was 3.5 (0.75–6.75) during sets performed with BFR and 4.0 (1.25–6.0) during sets without BFR. Subjective fatigue perception (Borg scale) was 8.0 (7.0–8.0) and 7.0 (7.0–8.0) for sets with and without BFR, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether muscle activation differed between a traditional high-load resistance protocol and a low-load protocol performed with BFR. The high-load protocol showed a greater fatigue response, whereas EMG remained unchanged when low loads were combined with BFR. These findings may suggest the immediate neuromuscular effects of BFR as a strategy to minimize mechanical load while preserving muscle activation.

The present findings must be interpreted considering the different load intensities used in each condition. The absence of changes in EMG amplitude when BFR was combined with 30% 1RM may partially reflect the lower mechanical demands of this protocol, which could limit the extent of neuromuscular fatigue and thereby contribute to the stable EMG profile observed. This interpretation aligns with Jagim et al. [16], who also reported reduced neuromuscular fatigue with low-load BFR compared with higher-load exercise. However, unlike Jagim et al. [16], who assessed fatigue through blood lactate and countermovement jump performance, our study specifically examined EMG responses and found that activation of the vastus medialis and gluteus maximus was maintained in the T1–T2 comparison. This distinction suggests that BFR may attenuate fatigue-related decrements in neuromuscular activation, but the underlying mechanisms and the degree to which load intensity versus BFR per se contributes to this effect may differ depending on the outcome measured [16].

On the other hand, our results complement previous research by Slysz et al. [36], who demonstrated that BFR training can induce significant increases in muscle strength and hypertrophy even when using low loads. While their work focused on chronic adaptations, our study adds complementary acute evidence by showing that EMG activation is maintained during low-load BFR training. This immediate response may contribute to the long-term adaptations reported in the literature. The data suggest that BFR not only promotes structural adaptations but also elicits acute neuromuscular responses that reinforce its value in both functional training and rehabilitation settings [36].

Moreover, Lorenz et al. [37] provided a clinical framework supporting the safety and efficacy of BFR during post-injury rehabilitation, particularly when traditional loads are not tolerated. Our findings align with this evidence, showing that even in healthy subjects, BFR enables the maintenance of high muscle activation without increasing injury risk. Furthermore, BFR appears to reduce neuromuscular fatigue compared with equivalent high-load exercise performed without occlusion [37]. Similarly, Patterson et al. [8] emphasized that the efficacy and safety of BFR exercise depends on careful control of methodological variables such as cuff width, occlusion pressure, and duration of restriction. Their review highlighted that, when individualized and monitored, BFR can be safely implemented not only in athletic populations but also in clinical rehabilitation, without increasing the risk of adverse cardiovascular or neuromuscular events. This aligns with the present findings, which demonstrate that BFR applied during multi-joint functional movements like the back squat can effectively maintain muscle activation while minimizing mechanical stress. These observations support the view of BFR as a versatile and evidence-based strategy for both performance optimization and safe load management in preventive or rehabilitative training contexts [8].

Furthermore, another study conducted by Wilson et al. [38] outlined commonly used BFR protocols, typically involving 20–40% of 1RM, occlusion pressures between 40–80%, restriction durations of 5–10 min, and training frequencies of 2–3 sessions per week. Their results indicated that practical BFR, using elastic bands such as floss bands, can enhance muscle activation and acute swelling without inducing additional muscle damage [38]. This physiological response is consistent with the present findings, as EMG activity of key muscles (gluteus maximus and vastus medialis) was maintained under BFR conditions. This suggests a favorable environment for the recruitment of type II fibers without excessive fatigue or structural stress. Overall, our results reinforce prior evidence supporting BFR as a safe and effective tool for both performance enhancement and rehabilitation, particularly in athletic populations [39]. Moreover, although BFR training helps sustain neuromuscular activation with lower loads, participants also reported a greater perception of fatigue and, potentially, post-exercise muscle soreness.

4.1. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small sample size, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, as this was a pilot study, the limited number of participants was expected and served to assess the feasibility and preliminary effects of BFR in this context.

Another limitation is that MVIC was measured only during the first session and used for EMG normalization in both visits. Although the sessions were separated by only one week—minimizing expected changes in maximal strength—this approach does not account for potential test–retest variability. Future studies should include session-specific MVIC assessments or formal reliability analyses to better control this source of variability.

Additionally, the inclusion of only male participants prevents conclusions regarding possible sex-related differences in response to BFR. Finally, since all subjects were physically active, extrapolation to sedentary or clinical populations should be made with caution.

Future studies may benefit from examining EMG activity across different phases of muscle contraction, such as concentric and eccentric actions, to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying neuromuscular patterns [40].

4.2. Clinical Relevance

This pilot study suggests that low-load BFR may elicit muscle activation levels approaching those typically observed during higher-load training, while potentially generating lower overall fatigue. This response could be particularly relevant in lower-limb rehabilitation, where early phases of recovery generally involve reduced mechanical loads to minimize the risk of symptom exacerbation or re-injury. In this context, strategies that promote muscle activation while maintaining low mechanical stress may hold potential clinical relevance. Although further research is necessary to confirm these preliminary findings, BFR could help mitigate muscle atrophy and attenuate strength loss during rehabilitation, potentially supporting a safer and more progressive return to functional activity.

4.3. Future Lines of Research

Future research should further explore the effects of BFR across different muscle groups, exercises, sports disciplines, and in female populations. It would also be valuable to investigate the combination of BFR with other training modalities to optimize both performance outcomes and functional recovery. Moreover, other outcomes like muscle oxygen saturation could complement these results. Finally, future randomized controlled trials with larger samples and higher statistical power should validate the preliminary results of this study.

5. Conclusions

EMG results showed no significant differences in electromyographic activation between the control and experimental groups in the VL and BF. However, significant findings were observed in the VM and GM. The non-BFR group exhibited a decrease in EMG activity toward the end of the exercise, indicating neuromuscular fatigue, whereas the BFR group maintained EMG levels throughout. These preliminary results may suggest the use of low-load BFR as an effective strategy to preserve muscle activation while minimizing mechanical stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G.-A., G.G.-P.-d.-S. and M.-J.G.; Methodology, M.G.-A., G.G.-P.-d.-S. and M.-J.G.; Software, F.S., G.L.-T. and D.P.; Validation, F.S., G.L.-T. and D.P.; Formal Analysis, M.G.-A. and G.G.-P.-d.-S.; Investigation, G.L.-T., D.P., F.S. and J.-Á.D.-B.-M.; Resources, J.-Á.D.-B.-M.; Data Curation, G.L.-T. and D.P.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, D.P., G.L.-T. and M.G.-A.; Writing—Review & Editing, all authors; Visualization, J.-Á.D.-B.-M.; Supervision, M.-J.G. and M.G.-A.; Project Administration, M.G.-A.; Funding Acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Spain) for studies involving humans on 2 July 2024 (approval code: 280520243442024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nicolay, R.W.; Moore, L.K.; DeSena, T.D.; Dines, J.S. Upper Extremity Injuries in CrossFit Athletes—A Review of the Current Literature. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2022, 15, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lastra-Rodríguez, L.; Llamas-Ramos, I.; Rodríguez-Pérez, V.; Llamas-Ramos, R.; López-Rodríguez, A.F. Musculoskeletal Injuries and Risk Factors in Spanish CrossFit® Practitioners. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.S.; Confino, J.E.; Vance, D.D. Common Orthopaedic Injuries in CrossFit Athletes. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2023, 31, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, G.J.; Wilson, J.M. A Mechanistic Approach to Blood Flow Occlusion. Int. J. Sports Med. 2010, 31, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Fahs, C.A.; Rossow, L.M.; Abe, T.; Bemben, M.G. The anabolic benefits of venous blood flow restriction training may be induced by muscle cell swelling. Med. Hypotheses 2012, 78, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieljacks, P.; Matzon, A.; Wernbom, M.; Ringgaard, S.; Vissing, K.; Overgaard, K. Muscle damage and repeated bout effect following blood flow restricted exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2016, 116, 513–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgomaster, K.A.; Moore, D.R.; Schofield, L.M.; Phillips, S.M.; Sale, D.G.; Gibala, M.J. Resistance Training with Vascular Occlusion: Metabolic Adaptations in Human Muscle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1203–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.D.; Hughes, L.; Warmington, S.; Burr, J.; Scott, B.; Owens, J.; Abe, T.; Nielsen, J.; Libardi, C.A.; Laurentino, G.; et al. Blood Flow Restriction Exercise: Considerations of Methodology, Application, and Safety. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, T.; Kearns, C.F.; Sato, Y. Muscle size and strength are increased following walk training with restricted venous blood flow from the leg muscle, Kaatsu-walk training. J. Appl. Physiol. 2006, 100, 1460–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, S.B.; Clark, B.C.; Ploutz-Snyder, L.L. Effects of Exercise Load and Blood-Flow Restriction on Skeletal Muscle Function. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1708–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ding, P.; Chen, N. Effectiveness of low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction vs. conventional high-intensity resistance training in older people diagnosed with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centner, C.; Wiegel, P.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Effects of Blood Flow Restriction Training on Muscular Strength and Hypertrophy in Older Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 95–108, Correction in Sports Med. 2019, 49, 109–111.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Rosenblatt, B.; Haddad, F.; Gissane, C.; McCarthy, D.; Clarke, T.; Ferris, G.; Dawes, J.; Paton, B.; Patterson, S.D. Comparing the Effectiveness of Blood Flow Restriction and Traditional Heavy Load Resistance Training in the Post-Surgery Rehabilitation of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Patients: A UK National Health Service Randomised Controlled Trial. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 1787–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipker, L.A.; Persinger, C.R.; Michalko, B.S.; Durall, C.J. Blood Flow Restriction Therapy Versus Standard Care for Reducing Quadriceps Atrophy After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. J. Sport Rehabil. 2019, 28, 897–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loenneke, J.P.; Wilson, J.M.; Marín, P.J.; Zourdos, M.C.; Bemben, M.G. Low intensity blood flow restriction training: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 112, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagim, A.R.; Schuler, J.; Szymanski, E.; Khurelbaatar, C.; Carpenter, M.; Fields, J.B.; Jones, M.T. Acute Responses of Low-Load Resistance Exercise with Blood Flow Restriction. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A.K.; Russell, A.P.; Della Gatta, P.A.; Warmington, S.A. Muscle Adaptations to Heavy-Load and Blood Flow Restriction Resistance Training Methods. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 837697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiş, O.; Gürses, V.V.; Şendur, H.N.; Altunsoy, M.; Pekel, H.A.; Yıldırım, E.; Aydos, L. Low-Load Resistance Exercise With Blood Flow Restriction Versus High-Load Resistance Exercise on Hamstring Muscle Adaptations in Recreationally Trained Men. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, e541–e552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, H.; Uematsu, A.; Mizushima, Y.; Nozawa, N.; Katayanagi, S.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishikawa, K.; Takahashi, R.; Arakawa, T.; Sawaguchi, T.; et al. Blood Flow Restriction Increases the Neural Activation of the Knee Extensors During Very Low-Intensity Leg Extension Exercise in Cardiovascular Patients: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merletti, R.; Rainoldi, A.; Farina, D. Surface Electromyography for Noninvasive Characterization of Muscle. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2001, 29, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, D. Interpretation of the Surface Electromyogram in Dynamic Contractions. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2006, 34, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortman, R.J.; Brown, S.M.; Savage-Elliott, I.; Finley, Z.J.; Mulcahey, M.K. Blood Flow Restriction Training for Athletes: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1938–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, S.M.; Chan, C.L.; Campbell, M.J.; Bond, C.M.; Hopewell, S.; Thabane, L.; Lancaster, G.A.; PAFS Consensus Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. BMJ 2016, 355, i5239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, G.R. Declaration of Helsinki—The World’s Document of Conscience and Responsibility. South. Med. J. 2014, 107, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, N.; Li, Y.; Qi, H. Acute effects of blood flow restriction training at various arterial occlusion pressures on muscle activation, blood lactate responses, and RPE in healthy adult males. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1620294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, T.P.; Jonson, A.M.; Dempsey, A.R.; Fairchild, T.J.; Girard, O. Prescribing Blood Flow Restricted Exercise: Limb Composition Influences the Pressure Required to Create Arterial Occlusion. J. Sport Rehabil. 2024, 33, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Arrabé, M.; González-de-la-Flor, Á.; Salniccia, F.; López-Ruiz, J.; García-Pérez-de-Sevilla, G. Development of a predictive formula for arterial complete occlusion pressure in upper and lower limbs during blood flow restriction. J. Tissue Viability 2025, 34, 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justo-Álvarez, A.; García-López, J.; Sabido, R.; García-Valverde, A. Validity of a New Portable Sensor to Measure Velocity-Based Resistance Training. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Molina, A.; Ruiz-Malagón, E.J.; Carrillo-Pérez, F.; Roche-Seruendo, L.E.; Damas, M.; Banos, O.; García-Pinillos, F. Validation of mDurance, A Wearable Surface Electromyography System for Muscle Activity Assessment. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 606287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2000, 10, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Arrabé, M.; De La Plaza San Frutos, M.; Bermejo-Franco, A.; Del Prado-Álvarez, R.; López-Ruiz, J.; del-Blanco-Muñiz, J.A.; Giménez, M.-J. Effects of Minimalist vs. Traditional Running Shoes on Abdominal Lumbopelvic Muscle Activity in Women Running at Different Speeds: A Randomized Cross-Over Clinical Trial. Sensors 2024, 24, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainoldi, A.; Melchiorri, G.; Caruso, I. A method for positioning electrodes during surface EMG recordings in lower limb muscles. J. Neurosci. Methods 2004, 134, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, B.N.; Greenstein, J.; Etnoyer-Slaski, J.L.; Sterling, H.; Topp, R. Electromyographic Analysis of Gluteus Maximus, Gluteus Medius, and Tensor Fascia Latae During Therapeutic Exercises with and Without Elastic Resistance. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2018, 13, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Loenneke, J.P.; Fahs, C.A.; Rossow, L.M.; Thiebaud, R.S.; Bemben, M.G. Exercise intensity and muscle hypertrophy in blood flow–restricted limbs and non-restricted muscles: A brief review. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2012, 32, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, G.A.V. Borg’s Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1998; 104p. [Google Scholar]

- Slysz, J.; Stultz, J.; Burr, J.F. The efficacy of blood flow restricted exercise: A systematic review & meta-analysis. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, D.S.; Bailey, L.; Wilk, K.E.; Mangine, R.E.; Head, P.; Grindstaff, T.L.; Morrison, S. Blood Flow Restriction Training. J. Athl. Train. 2021, 56, 937–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M.; Lowery, R.P.; Joy, J.M.; Loenneke, J.P.; Naimo, M.A. Practical Blood Flow Restriction Training Increases Acute Determinants of Hypertrophy Without Increasing Indices of Muscle Damage. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 3068–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loenneke, J.; Abe, T.; Wilson, J.; Thiebaud, R.; Fahs, C.; Rossow, L.; Bemben, M. Blood flow restriction: An evidence based progressive model (Review). Acta Physiol. Hung. 2012, 99, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, H.; Quan, W.; Gusztav, F.; Baker, J.S.; Gu, Y. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system model driven by the non-negative matrix factorization-extracted muscle synergy patterns to estimate lower limb joint movements. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 242, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).