Abstract

Amid the global energy transition, the rapid growth of wind turbine deployment has highlighted the need for accurate fatigue load prediction to support structural design and ensure operational reliability. This study proposes a neural network-based method for estimating fatigue loads at critical locations of large wind turbines. Wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle were used as input features, while the damage equivalent loads at the blade root, tower base, and yaw bearing served as prediction targets. A dataset comprising 2139 operating conditions was constructed, and two predictive models—an artificial neural network (ANN) and a Bayesian neural network (BNN)—were developed and evaluated using standard error metrics. The results show that the BNN consistently achieves lower prediction errors and higher goodness-of-fit values than the ANN across all outputs, demonstrating improved accuracy and stability. The BNN model attained excellent predictive performance, with an overall coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.9998, a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.012, and a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of only 0.1877%. These findings indicate that probabilistic neural networks hold strong potential for enhancing fatigue load prediction and can provide valuable support for wind turbine structural assessment, design optimization, and active yaw control strategies.

1. Introduction

With increasing global environmental awareness and rapid advancements in science and technology, clean and pollution-free renewable energy has gained significant attention. Currently, as worldwide electricity demand continues to rise, wind energy—a clean and renewable power source—has been recognized as an effective solution to meet this growing demand [1]. According to the Global Wind Report 2024, the cumulative installed wind power capacity worldwide has surpassed 1021 GW, with 117 GW of new capacity added in 2023 alone—a 50% annual increase compared to 2022, setting a new annual installation record [2]. As a key pillar in achieving global net-zero emissions, wind power generation has been widely adopted across the globe, leading to the construction of numerous wind farms. However, the wake effect in wind farms remains a critical challenge: when wind flows through an upstream wind turbine, a portion of its kinetic energy is extracted, reducing the available wind energy for downstream turbines. This phenomenon not only decreases wind speed for downstream turbines but also increases turbulence intensity. The reduced wind speed directly lowers the total power output of wind farms, thereby diminishing economic efficiency. Meanwhile, heightened turbulence intensity exacerbates fatigue loads and induces high dynamic fluctuations in active power, ultimately shortening the operational lifespan of wind turbines [3].

To effectively mitigate the wake effect in wind farms, various wake adjustment methods have been developed in recent years, including tilt angle adjustment, individual pitch control, and active yaw control. Tilt angle adjustment can change the direction of the wake, but it is uncertain because different tilt angles can cause different degrees of load increase or decrease at different positions [4]. Although individual pitch control is easy to implement, its wake adjustment effect is limited and may have a negative impact on the service life of key components [5]. Active yaw control adjusts the direction of the upstream wind turbine nacelle to change the wake direction, thereby reducing the wake effect on the downstream wind turbine and improving the overall power generation efficiency of the wind farm. However, during the yaw control process, due to the rapid changes in wind direction and the slow response of the yaw system, wind turbines often experience yaw misalignment during operation. Yaw misalignment not only reduces power output but also increases the load on wind turbine, thereby shortening their service life [6]. In addition, an improperly designed yaw angle can exacerbate load issues [7]. Studies have shown that although active yaw control can effectively increase power generation, it still has a certain impact on the fatigue life of wind turbines [8]. Meng et al. [9] further confirmed that under wake control conditions, with the increase in yaw angle, the fatigue damage of wind turbine blades in the direction outside the rotor plane can increase by 50%. Therefore, accurately predicting the fatigue loads of wind turbines under different yaw angles is of great theoretical and practical significance for the design of large wind turbines and the optimization of yaw control.

During their operational life cycle, wind turbines primarily experience ultimate loads and fatigue loads. Ultimate loads typically occur under extreme wind speed conditions. Although they are highly destructive, their probability of occurrence during the design service life is relatively low. Therefore, the impact of fatigue loads is more pronounced in the routine operation of wind turbines. Traditional fatigue life prediction for wind turbines is a complex and time-consuming process. It usually involves obtaining a load spectrum through physical sensor monitoring, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems, or simulation calculations, and then combining the Rain Flow Counting method (RFC) and Miner’s rule for fatigue prediction. Some scholars have also conducted fatigue predictions by establishing physical models or load databases. Huo et al. [10] derived the joint distribution function of wind speed and wind direction in a wind farm based on meteorological station observation data. They comprehensively considered the variation in wind direction, the dynamic rotation characteristics of blades, and the fatigue accumulation effect under low-stress conditions, and established a systematic fatigue analysis theory for wind turbine towers in both time and frequency domains. Although this method demonstrates good prediction accuracy, due to the significant geographical differences in wind resources, fatigue assessment needs to be re-conducted for different wind conditions, which to some extent increases the time cost of engineering applications. Fu et al. [11] analyzed a large amount of load data, derived the impact of various wind conditions on loads, and established a fatigue load database. By inputting wind condition parameters to search the database and performing interpolation calculations, fatigue loads can be directly extracted, which greatly improves the efficiency of fatigue analysis. However, the prediction accuracy of this method for fatigue loads still needs to be examined.

With the rapid development of computer science, machine learning (ML), as an important branch of artificial intelligence [12], has demonstrated strong application potential in various fields. Particularly in the field of wind turbines, the application of ML technology has covered wind speed and wind energy prediction [13,14,15], condition monitoring and fault prediction of wind turbines [16,17,18,19], and fatigue load prediction of key components of wind turbines [20,21]. Taking blade fatigue load prediction as an example, some researchers have achieved effective prediction by combining SCADA data with neural network models [22]. Dolatabadi et al. [23] proposed a LiDAR-assisted two-dimensional convolutional neural network–bidirectional long short-term memory model, which takes wind farm component sequences and wind speed time sequences as inputs to predict the power and fatigue loads of wind turbines. The model effectively helps to solve yaw error problems to extend the fatigue life of wind turbines. He et al. [24] used the high-fidelity aeroelastic tool OpenFAST to conduct 12,728 ten-minute case simulations of the NREL 5 MW model under different conditions. By taking yaw angle, turbulence intensity, and wind conditions as inputs, and damage equivalent load (DEL) of key components and average power of wind turbine as outputs to establish a dataset, they constructed a nonlinear mapping model between wind turbine operating parameters and structural responses using the support vector regression algorithm. The research validation shows that the algorithm has small prediction errors and strong robustness. In addition, it can be integrated into active yaw control strategies to improve power generation efficiency and optimize fatigue loads. Ren et al. [25] proposed an active learning method called AK-MDAmax, which uses the Kriging model to predict tower fatigue damage under different wind and wave conditions. Compared with traditional fatigue damage calculation methods, the computational efficiency is improved by 35 times. In addition, many scholars have used Gaussian process regression models [26] and hidden Markov models [27] to predict fatigue damage. It can be seen that using machine learning methods instead of traditional fatigue calculation methods provides a new solution for fatigue load prediction of wind turbine.

In the field of wind turbine monitoring and fatigue prediction [28], artificial neural networks (ANNs) have become an important research tool due to their excellent capabilities in nonlinear modeling, adaptive learning, parallel processing, and fault tolerance. The response of wind turbines to changes in average wind speed is nonlinear, which leads to alterations in the stress transfer function caused by wind. To accurately obtain this stress transfer function from fatigue analysis, numerous environmental factors need to be considered, involving a large amount of simulation work that is time-consuming. To reduce the number of simulations, Kim et al. [29] introduced an ANN model to assess the effect of average wind speed on fatigue. They used the stress transfer function, stress spectrum, and fatigue damage as output results, with average wind speed and frequency as input data. By using the ANN model, they were able to reduce the number of required simulations from 41 to 7 while maintaining a maximum error of no more than 35%, thus saving a significant amount of time. Ziane et al. [30] used ANN to predict the fatigue life of wind turbine blades under different environmental conditions and compared the performance of three different networks. The results showed that the Cuckoo Search Neural Network, which can change weights under uncertain gradient conditions, performed better in prediction than the other two networks. Luna et al. [31] developed a nonlinear model predictive control method using ANN, which not only ensures high wind energy absorption but also effectively reduces the fatigue loads on wind turbine towers. Wang et al. [32] proposed a novel yaw optimization algorithm that takes into account both power generation and fatigue loads and successfully applied it in a real wind farm, resulting in a 6.4% increase in total power generation and a 23.53% reduction in fatigue loads.

Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs), as an improvement and extension of traditional ANNs, have been successfully applied in the fields of medium-term wind speed forecasting [33], power generation prediction [34], and wind energy prediction [35]. Unlike conventional ANNs, BNNs introduce probability distributions for network parameters through Bayesian inference. This characteristic not only endows the model with an intrinsic regularization effect but also significantly enhances its robustness and generalization ability. However, it is noteworthy that despite these significant advantages, the application of BNNs in the field of wind turbine fatigue life prediction remains quite limited. It is this research gap that makes the introduction of BNNs into wind turbine fatigue life prediction an innovative and valuable research direction.

This paper proposes a neural network-based framework for predicting the fatigue loads of key wind turbine components, with a focus on improving prediction efficiency and supporting structural design and operational decision-making. An artificial neural network (ANN) and a Bayesian neural network (BNN) are developed using wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle as input features, and the damage equivalent loads at critical turbine locations as prediction targets. The study aims to evaluate the predictive capability of probabilistic neural networks and assess their potential advantages over conventional deterministic models.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the dataset and model architecture, as well as the training procedure and evaluation metrics. Section 3 reports the prediction results, and Section 4 provides a detailed discussion of the findings and model limitations. Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Methodology

To fully leverage the advantages of machine learning methods for predicting the fatigue life of wind turbines, constructing a high-quality dataset is crucial. Acquiring field measurement data is inherently difficult and resource-intensive; obtaining long-term, high-quality data encompassing the 2139 operating condition combinations considered in this study would be practically infeasible. In contrast, wind turbine simulation tools provide a cost-effective and efficient means of data acquisition. Simulations allow precise control of key variables—such as wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle—and can generate large, high-quality datasets that comprehensively account for environmental factors and control strategies. This capability facilitates systematic evaluation of model performance across diverse operating conditions and supports the broad applicability of the proposed prediction method.

2.1. Simulation Platform and Fatigue Load Calculation

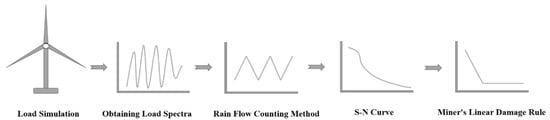

Fatigue damage assessment in wind turbine structures is fundamentally based on three key elements: the Rainflow Counting (RFC) method, the S–N fatigue life curve, and Miner’s linear cumulative damage rule. As illustrated in Figure 1, the RFC algorithm processes the simulated load time series by decomposing the complex, variable-amplitude load history into a series of discrete stress cycles. Using the material-dependent S–N curve, the fatigue damage associated with each cycle is quantified, and the total fatigue damage is subsequently obtained through Miner’s rule.

Figure 1.

Fatigue Life Prediction Process.

However, in fatigue analysis, to more conveniently assess the fatigue damage of wind turbines, the Damage Equivalent Load (DEL) is commonly used to represent fatigue (i.e., fatigue load) instead of remaining fatigue life or damage fraction. DEL is a signal with constant amplitude, fixed frequency, and fixed mean value, and the damage it produces after cycles is equivalent to the fatigue damage caused to the material or structure by the original load spectrum. Since the damage in Miner’s rule is an abstract quantity that is difficult to quantify as a ratio of cycles, and DEL provides a measurable quantity, the fatigue life prediction of wind turbines typically uses DEL rather than accumulated damage [36]. The calculation formula for DEL is shown in Equation (1) [36].

where

is the number of cycles;

is the stress amplitude;

is the fatigue strength exponent;

is the equivalent load cycle count, which is typically 106 in the wind energy industry.

In this study, all fatigue loads used for model training were obtained from the WeMoLab (Beta 23.10.0.7101) aeroelastic simulation platform. WeMoLab implements the standard RFC–S–N–Miner fatigue evaluation process and directly outputs DELs for critical structural locations, including the blade root, tower base, and yaw bearing. This computational framework is fully consistent with mainstream industry tools such as Bladed and HAWC2 (version 13.2.0), ensuring that the DEL results generated in this work are reliable and comparable to established engineering practices.

2.2. Simulation Case Setup

In this study, a 15 MW onshore wind turbine model provided in WeMoLab was used for load simulation. The reference turbine model features a rotor diameter of 241.91 m and a hub height of 150 m. Other key specifications are summarized in Table 1. Subsequently, Design load case 1.2 (DLC1.2) was set according to the design requirements for wind turbines formulated and released by the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) [37]. DLC1.2 mainly focuses on the damage experienced by wind turbines during normal operating conditions.

Table 1.

Parameters of the 15 MW Onshore Wind Turbine.

Due to the randomness of wind loads and the turbulent characteristics of wind, the fatigue damage assessment of wind turbines typically requires at least 10 min of time-domain simulation for each wind condition to obtain sufficient load data for calculating fatigue life. Studies have shown [38] that environmental wind speed and air turbulence have a decisive impact on the fatigue loads of blades and towers, and different yaw angles also affect the DEL at the base of the tower. Therefore, this paper selects wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle as input variables and establishes 2139 simulation cases with a duration of 630 s each.

Table 2 shows the detailed case settings. Referring to the technical specifications of the NREL 15 MW wind turbine, the cut-in and cut-out wind speeds are set at 3 m/s and 25 m/s, respectively. At this point, the wind speed range at the hub height is set from 3 to 25 m/s, with a step length of 1 m/s. Turbulence intensity is divided into three levels: Level A has an intensity of 0.16, Level B has an intensity of 0.14, and Level C has an intensity of 0.12. To comprehensively cover all possible nacelle yaw angle scenarios, the yaw angle range is set from −30° to +30°, with a step length of 2°.

Table 2.

Simulation condition setting table.

2.3. Dataset Establishment

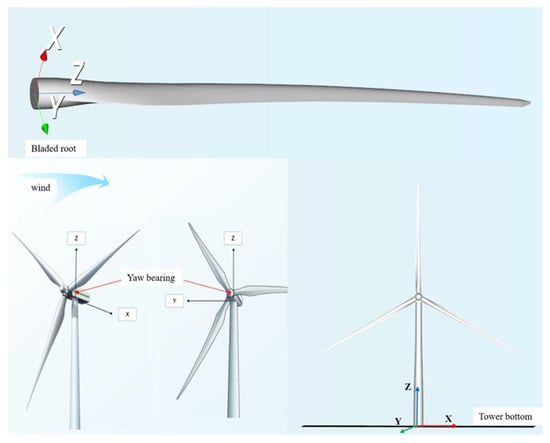

To comprehensively assess the impact of different wind conditions and yaw angles on the structural performance of wind turbines, as shown in Figure 2, the DELs at the blade root, tower base, and yaw bearing were selected as key indicators for analysis. The bending moment at the blade root is a critical factor affecting the structural performance of wind turbines, especially the bending moment perpendicular to the blade plane, which causes high-stress concentration at the blade root and may lead to fatigue failure. The centrifugal force generated by the rotation of the blades also increases the radial force at the blade root. The wind load, combined with the weight of the nacelle and tower, acts on the tower base, producing high bending moments and forces, with excessive bending moments potentially causing fatigue or instability in the tower base structure. The horizontal force at the yaw bearing not only causes friction and wear in the yaw system but also affects changes in yaw torque (bending moment around the Z-axis). Excessive yaw torque can lead to fatigue damage of the yaw bearing, thereby affecting the yaw capability and operational stability of the wind turbine. Considering the combined effects of these factors to more accurately predict the fatigue life of wind turbines, this study extracted the DELs of 10 load components of three key components of the wind turbine as representatives. These load components include: radial force at the blade root (BrFZ), bending moments around the X and Y axes at the blade root (BrMX and BrMY), horizontal forces at the tower base (TbFX and TbFY), bending moments around the X and Y axes at the tower base (TbMX and TbMY), horizontal forces at the yaw bearing (YbFX and YbFY), and yaw torque (YbMZ).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of key components of the wind turbine.

In this study, wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle were used as input variables, while the DELs at the blade root, tower base, and yaw bearing were used as output variables to construct the dataset for training the neural network. In neural networks, the processing of the dataset is crucial, as appropriately processed data can enhance the training efficiency, stability, and generalization ability of the network model. Therefore, this paper first performed a logarithmic transformation on the dataset. This step helps stabilize the variance and transform the data into a form that more closely follows a normal distribution, thereby improving the model’s convergence speed and prediction accuracy. Subsequently, the dataset was further divided into a training set (accounting for 80%) and a testing set (accounting for 20%). This division ratio aims to ensure that the model has sufficient data for learning during the training process while reserving a portion of the data to evaluate the model’s generalization ability.

2.4. Prediction Models and Methods

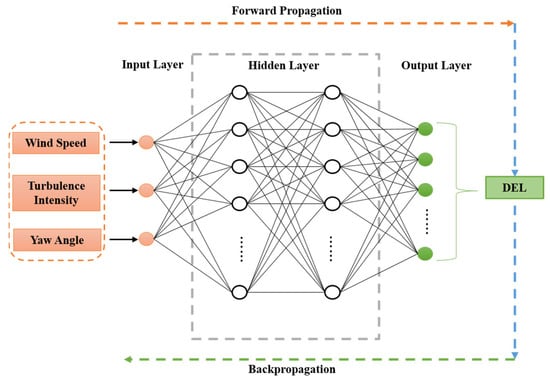

As one of the core technologies of modern artificial intelligence, neural networks have garnered significant attention due to their extensive applications in function approximation, associative memory, pattern association, and pattern recognition [39]. In recent years, particularly in the field of fatigue load prediction for key components of wind turbines, neural networks have received considerable attention [31]. The architecture of an ANN consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer (as shown in Figure 3), with each layer containing a certain number of neurons. Each neuron receives input signals from neurons in the previous layer, performs a weighted sum, and then applies a nonlinear transformation through an activation function, passing the result to neurons in the next layer. The final prediction of damage equivalent load is obtained through forward propagation.

Figure 3.

Network Architecture.

A single network architecture is used in this study to simultaneously predict all DEL outputs. Using one unified multi-output model eliminates the need to train a separate network for each load channel, thereby significantly improving computational efficiency and allowing the network to learn correlations among different structural responses.

The BNN extends this structure by introducing probabilistic representations of the network parameters. Instead of learning fixed weights, the BNN learns distributions over weights and biases using variational inference. This enables the model to quantify predictive uncertainty and improves robustness when dealing with noisy or highly variable wind-induced loads. The Bayesian formulation also provides an inherent regularization effect, mitigating overfitting without relying on additional techniques such as dropout or L2 penalties. These characteristics make BNNs particularly suitable for fatigue load prediction, where load variability and aleatory uncertainty are significant.

In contrast to ANNs, in BNNs, the weights are treated as random variables, meaning that each weight in the network follows an unknown distribution. To obtain this unknown distribution, a prior distribution for the parameters is first assumed, denoted as . This prior distribution can be thought of as a guess or intuition about the possible outcomes of the model parameters before observing any actual data. It reflects our initial views or assumptions about these parameters.

After observing the data, a posterior distribution for the parameters can be derived, denoted as . The posterior distribution incorporates information from both the prior and the observed data. With a large number of observations, the posterior distribution can be made to approximate the true distribution of the parameters.

Assuming that the observed data are independently and identically distributed, given a dataset , the posterior distribution of the parameters can be obtained using Bayes’ theorem [40]:

where

represents the D-dimensional feature vector, and is the target variable corresponding to .

is called the likelihood function.

is called the normalizing constant.

However, due to the nonlinearity of neural networks, the integral operation becomes very difficult, making the true posterior distribution intractable to compute using analytical methods. Therefore, Bayesian inference methods are relied upon to approximate the true solution. Bayesian inference methods are mainly divided into two types: Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) and Variational Inference (VI). While the former can obtain a distribution closer to the true posterior, it has a higher computational cost. Therefore, this paper chooses the VI method to approximate the posterior distribution of the Bayesian model.

The core idea of VI is to construct a computationally convenient variational distribution to approximate the complex true posterior distribution, and then minimize the Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence to measure the difference between these two probability distributions. When the two probability distributions are significantly different, the KL divergence value increases positively; as the similarity between the distributions increases, this value asymptotically converges to zero. Let be the approximate variational distribution of the posterior distribution (with as the parameter of the variational distribution). By minimizing the KL divergence between the two distributions, the posterior inference problem can be transformed into an optimization problem for the parameter . The KL divergence between and is given by the following formula [41]:

where ELBO stands for the Evidence Lower Bound.

Since the dataset is fixed, is a constant. Thus, minimizing the KL divergence can be transformed into minimizing −ELBO [42]. Based on the non-negativity of KL divergence, the Equation (3) can be converted into the form of a loss function:

The loss function consists of two parts. The first part measures the difference between the variational posterior distribution and the prior distribution and is called the KL divergence term. The second part represents the average fit of the training data D and is called the expected log-likelihood term. When the loss function is minimized, the KL divergence term should be as small as possible, indicating that the variational posterior distribution needs to be as close as possible to the prior distribution. Meanwhile, the expected log-likelihood term should be as large as possible, meaning that the model’s predictions are closer to the true label values.

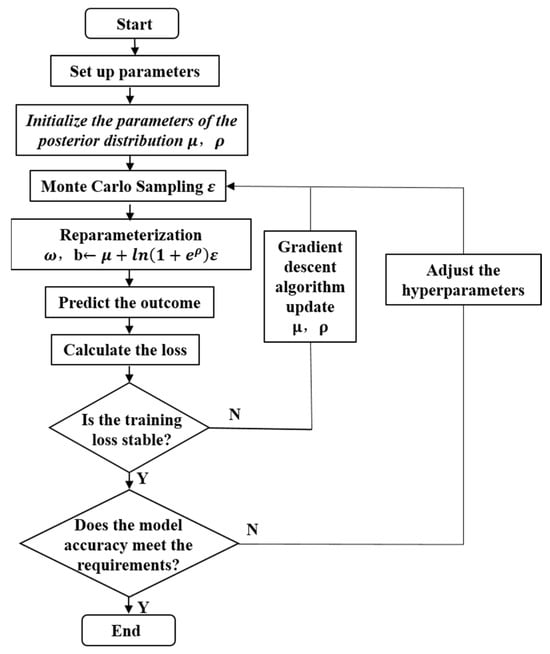

Construct the Bayesian Neural Network using Equation (4) as the loss function. The complete training process of the BNN is shown in Figure 4. First, set the initial values of the hyperparameters, including the number of hidden layers, the number of neurons, batch size, sampling times, noise value, learning rate, and training epochs. In the BNN, the activation function chosen is PReLU. Compared to other activation functions, PReLU not only has extremely high computational efficiency but also maintains a constant gradient in both positive and negative intervals, which helps to alleviate the problem of vanishing gradients. The optimizer selected is the Adam algorithm. The Adam optimizer is a widely used intelligent optimization method in deep learning. This algorithm can significantly improve the convergence speed and stability of model training. It can also automatically adjust the learning rates of different parameters based on their historical gradient information, allowing each parameter to have a differentiated update step size. The posterior distribution parameters and are initialized to 0 and −5, respectively. This makes the distribution approximately degenerate to deterministic values, ensuring that the initial weights and biases are concentrated around the mean, thereby enhancing model stability and reducing fluctuations in the early stages of network training. After reparameterizing the weights and biases , the differences between the output values and the label values, as well as between the prior and posterior distributions, are calculated based on the loss function. Finally, the gradients of each layer are computed through backpropagation according to the loss, thereby updating the distributions of the weights and biases . The network is optimized by adjusting the hyperparameters to achieve the best training effect, and the final hyperparameter settings are shown in Table 3 Hyperparameter Settings for Bayesian Neural Networks.

Figure 4.

The framework of the fatigue life prediction method based on BNN.

Table 3.

Hyperparameter Settings for Bayesian Neural Networks.

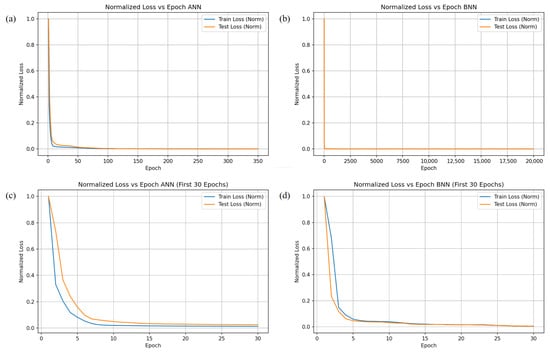

To further assess the training behavior and evaluate the risk of overfitting, Figure 5 illustrates the training and validation loss curves for both the ANN and the BNN models. The ANN model converges after approximately 350 epochs, where its training and validation losses remain closely aligned, indicating that no significant overfitting occurs within the available dataset. In contrast, the BNN requires substantially more training iterations due to the optimization of variational distributions, with its loss gradually decreasing over roughly 20,000 epochs before reaching convergence. Similar to the ANN, the BNN exhibits no divergence between the training and validation curves, demonstrating stable generalization behavior throughout training. These results verify that both neural network models were trained without observable overfitting under the current dataset size and network configurations, providing a reliable basis for the subsequent prediction analyses presented in Section 3.

Figure 5.

Training and validation loss curves of ANN and BNN models (a) ANN (full); (b) BNN (full); (c) ANN (first 30 epochs); (d) BNN (first 30 epochs).

3. Results

To accurately and effectively evaluate the performance of ANN and BNN in predicting the fatigue life of wind turbines, this section assesses them using three different error metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination R2. These metrics measure the model’s accuracy and fit from different perspectives.

RMSE measures the absolute distance between the predicted values and the actual label values. A smaller RMSE indicates that the model’s predictions are closer to the actual values, reflecting higher prediction accuracy. MAPE measures the relative distance between the predicted values and the actual label values. A lower MAPE value suggests that the deviation between the predicted results and the true data is smaller, indicating more precise predictions. R2 is a core indicator for evaluating the fit of a regression model, with values ranging between 0 and 1. This metric reflects the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. An R2 value closer to 1 indicates a stronger explanatory power of the model and a higher consistency between the predicted and observed values.

In practical applications, these three metrics together provide a comprehensive perspective for evaluating and comparing the performance of different models, guiding model selection, and optimization. Their formulas are as follows:

where

is the actual value;

is the predicted value;

is the number of samples;

is the mean of the data.

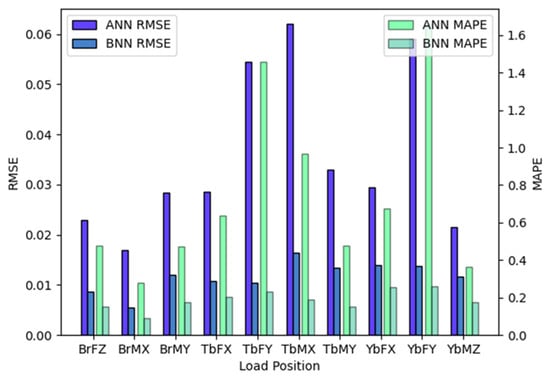

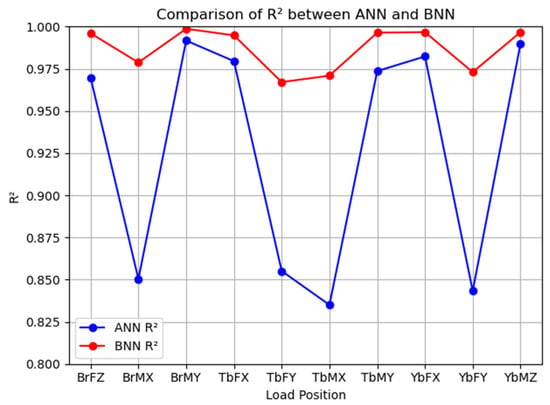

Table 4 summarizes the prediction performance of the ANN and BNN models for all fatigue load outputs. As shown in Figure 6, the BNN yields lower RMSE and MAPE values than the ANN across most structural locations. At the blade root and tower base positions, the reduction in RMSE and MAPE is particularly evident. Figure 7 further shows that the R2 values of the BNN predictions are consistently closer to 1, indicating a higher degree of agreement between predicted and reference DEL values. Both models exhibit relatively higher prediction errors at the BrMX, TbFY, TbMX, and YbFY locations. Figure 6 and Figure 7 show that RMSE, MAPE, and R2 at these positions deviate more noticeably from the overall trend. Nevertheless, the prediction accuracy remains generally high for both ANN and BNN across all eight output variables.

Table 4.

Prediction performance comparison for BNN and ANN.

Figure 6.

Comparison of RMSE and MAPE between ANN and BNN.

Figure 7.

Comparison of R2 between ANN and BNN.

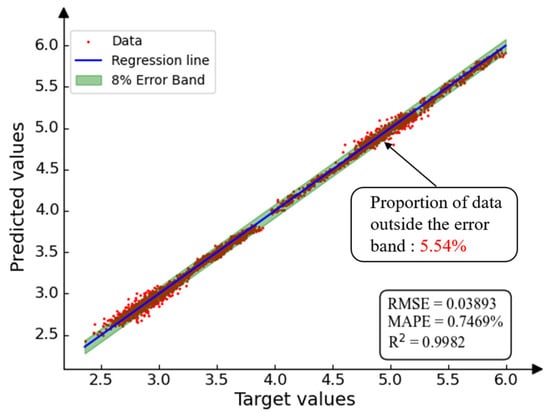

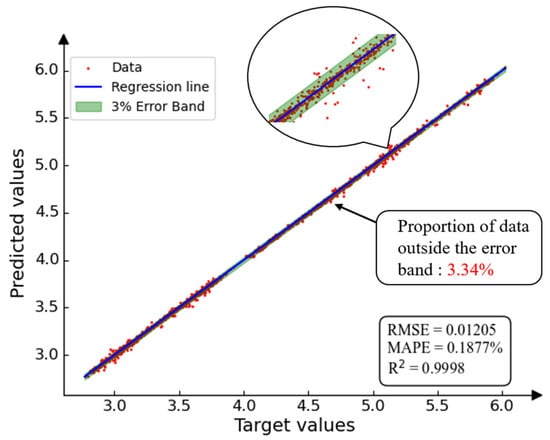

Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the regression results and error distributions for all prediction targets. Quantitatively, the BNN achieves an overall RMSE of 0.01205, compared with 0.0389 for the ANN. The corresponding MAPE values are 0.1877% and 0.747%, respectively. While both models maintain high R2 values, the BNN exhibits a tighter clustering of predicted data points around the reference line. Error distribution analysis further shows that more than 95% of the BNN prediction errors fall within a ±3% range, whereas the ANN achieves this for only about 8% of the samples. In contrast, ANN predictions show greater dispersion and are more sensitive to noise, particularly at positions with stronger aerodynamic–structural coupling.

Figure 8.

Overall prediction performance of the ANN model.

Figure 9.

Overall prediction performance of the BNN model.

This consistent performance advantage reflects the effect of Bayesian parameter estimation in suppressing overfitting and stabilizing predictions under highly variable wind-induced loads. These results demonstrate clear quantitative differences between the two models and provide a solid basis for the subsequent comparative analysis.

4. Discussion

The comparative results presented in Section 4 demonstrate that the BNN consistently outperforms the ANN across most structural locations of the 15 MW wind turbine, achieving lower RMSE and MAPE values as well as higher R2 values. The tighter clustering of BNN predictions around the reference line, observed in Figure 8 and Figure 9, further confirms the enhanced stability and predictive reliability of the Bayesian approach. These improvements align with previous findings that probabilistic neural network frameworks can more effectively capture nonlinear load characteristics and reduce prediction dispersion in complex aero-elastic systems.

To understand the underlying mechanisms, it is important to examine the training behavior and generalization characteristics of the two models. The ANN converges rapidly due to its deterministic structure, efficiently capturing dominant trends in the data, though it is more sensitive to noise in highly coupled load channels such as BrMX, TbFY, TbMX, and YbFY. In contrast, the BNN converges through iterative posterior-update and sampling processes inherent to Bayesian learning. This probabilistic formulation provides an implicit regularization effect that stabilizes predictions, mitigates overfitting, and reduces variance through posterior-mean model averaging, leading to the tighter clustering observed in Figure 8 and Figure 9. These behaviors highlight the BNN’s robustness in handling complex, noisy load patterns.

Despite the overall superior performance of the BNN, both models exhibit relatively higher errors at the BrMX, TbFY, TbMX, and YbFY positions. These locations are typically subject to turbulence-induced fluctuations and strong coupling between aerodynamic and structural responses. The current input feature set—wind speed, turbulence intensity, and yaw angle—may not fully capture the dynamic factors influencing these loads. Incorporating additional descriptors, such as shear gradients, tower shadow effects, or yaw misalignment dynamics, could further improve predictive performance at these positions, though it would also increase model complexity and data requirements.

The BNN’s training process, while highly effective, involves iterative sampling and variational inference steps that require more epochs to converge compared with the ANN. This computational demand reflects the trade-off inherent in uncertainty-aware learning: the enhanced prediction stability and reduced overfitting provided by the BNN comes with increased training effort. Future directions for improving efficiency include sparse Bayesian architectures, adaptive sampling strategies, or hybrid deterministic–probabilistic network designs.

Generalizability also remains an important consideration. The models were trained on data from a single 15 MW onshore turbine, which limits their ability to extrapolate to turbines operating offshore, at different rated power levels, or under complex wind conditions. Moreover, the current framework is purely data-driven: while DEL labels capture fatigue-related information, no physics-based fatigue mechanisms, such as S–N curves or stress cycle distributions, are incorporated. Integrating physics-informed constraints or fatigue-guided regularization could enhance both interpretability and predictive reliability under extreme or unseen operating conditions.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that probabilistic deep learning offers clear advantages for fatigue load prediction in large wind turbines, particularly in capturing nonlinear load patterns and reducing prediction dispersion. At the same time, the analysis identifies several areas for improvement—feature enrichment, computational efficiency, dataset diversity, and physics-informed modeling—that will guide future efforts to enhance the robustness and practicality of neural-network-based fatigue assessment methods.

5. Conclusions

This study developed neural network-based models to predict fatigue loads at key structural locations of a large wind turbine. An ANN model was first constructed as a baseline, which achieved reliable prediction accuracy across most operating conditions. Building on this foundation, a BNN model was further established to incorporate probabilistic learning and uncertainty quantification. The BNN achieved lower prediction errors and higher fitting accuracy than the ANN, demonstrating improved overall performance in fatigue load estimation.

The comparative evaluation of both models shows that the BNN provides more concentrated prediction distributions and reduced error dispersion for all output variables. These results indicate that probabilistic neural networks offer clear advantages for capturing complex aero-elastic behaviors in wind turbine structures. The findings provide a useful reference for integrating data-driven methods into wind turbine structural assessment and for supporting future developments in condition monitoring and operation management.

Author Contributions

H.J.: Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation. J.Z.: Validation, Investigation. H.G.: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Software, Investigation. S.L.: Visualization, Validation, Software. X.S.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision. Q.Z.: Validation, Investigation. Y.X.: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization. B.L.: Writing—review and editing. W.H.: Writing—review and editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFB4201200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 12272131), the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Hunan Province (2024RC3084), and the Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (2025JJ50041). The APC was funded by Hunan University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Arslan Tuncar, E.; Sağlam, Ş.; Oral, B. A review of short-term wind power generation forecasting methods in recent technological trends. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wind Report 2024; Global Wind Energy Council: Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Bai, G.; Feng, Y.; Ma, Z.-Q.; Li, X. An Asynchronous Distributed Optimal Wake Control Scheme for Suppressing Fatigue Load and Increasing Power Extraction in Wind Farms. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.A.; Gebraad, P.M.O.; Lee, S.; van Wingerden, J.-W.; Johnson, K.; Churchfield, M.; Michalakes, J.; Spalart, P.; Moriarty, P. Evaluating techniques for redirecting turbine wakes using SOWFA. Renew. Energy 2014, 70, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnolo, F.; Petrović, V.; Bottasso, C.L.; Croce, A. Wind tunnel testing of wake control strategies. In Proceedings of the 2016 American Control Conference (ACC), Boston, MA, USA, 6–8 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, P.A.; Scholbrock, A.K.; Jehu, A.; Davoust, S.; Osler, E.; Wright, A.D.; Clifton, A. Field-test results using a nacelle-mounted lidar for improving wind turbine power capture by reducing yaw misalignment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 524, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Porté-Agel, F. Power Maximization and Fatigue-Load Mitigation in a Wind-turbine Array by Active Yaw Control: An LES Study. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1618, 042036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanev, S.; Bot, E.; Giles, J. Wind Farm Loads under Wake Redirection Control. Energies 2020, 13, 4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Yu, X.; Chang, S. Study on equivalent fatigue damage of two in-a-line wind turbines under yaw-based optimum control. Int. J. Green Energy 2022, 20, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, T.; Tong, L. An approach to wind-induced fatigue analysis of wind turbine tubular towers. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2020, 166, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, P.; Zou, L.; Wu, W.; Dou, W.; Zhang, J. Wind Farm Fatigue Load Site Suitability Tool Based on Database. Ship Eng. 2020, 42, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Huang, L.; Li, J.; Xia, Z.; Ding, Y.; Fang, Q.; Liu, B.; He, W.; Xie, H. Intelligent localization method of fatigue crack tips in enormous high-temperature DIC images. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadevi, B.; Kasi, V.R.; Bingi, K. Enhancement of Texas wind turbine power predictions using fractional order neural network by incorporating machine learning models to impute missing data. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 300, 112176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Shi, K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, X. A novel temporal–spatial graph neural network for wind power forecasting considering blockage effects. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.; Aly, H.H. Short term wind speed forecasting using artificial and wavelet neural networks with and without wavelet filtered data based on feature selections technique. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, C.; Li, K.; Yang, J.; Xie, N.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y. Hierarchical spatial–temporal autocorrelation graph neural network for online wind turbine pitch system fault detection. Neurocomputing 2024, 586, 127574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, P.; Rizk, F.; Karganroudi, S.S.; Ilinca, A.; Younes, R.; Khoder, J. Advanced wind turbine blade inspection with hyperspectral imaging and 3D convolutional neural networks for damage detection. Energy AI 2024, 16, 100366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wu, Y.; Sun, Z.; Shen, W.; Guo, G.; Lin, J. A method of convolutional neural network based on frequency segmentation for monitoring the state of wind turbine blades. Theor. Appl. Mech. Lett. 2023, 13, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Nava, V. Condition monitoring of mooring systems for Floating Offshore Wind Turbines using Convolutional Neural Network framework coupled with Autoregressive coefficients. Ocean Eng. 2024, 302, 117650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghinezhad, J.; Sheidaei, S. Prediction of operating parameters and output power of ducted wind turbine using artificial neural networks. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3085–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Xing, Y. An efficient active learning Kriging approach for expected fatigue damage assessment applied to wind turbine structures. Ocean Eng. 2024, 305, 118034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Tudela, L.; Kühn, M. Analysing wind turbine fatigue load prediction: The impact of wind farm flow conditions. Renew. Energy 2017, 107, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatabadi, A.; Abdeltawab, H.; Mohamed, Y.A.-R.I. Deep Spatial-Temporal 2-D CNN-BLSTM Model for Ultrashort-Term LiDAR-Assisted Wind Turbine’s Power and Fatigue Load Forecasting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 2342–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Yang, H.; Sun, S.; Lu, L.; Sun, H.; Gao, X. A machine learning-based fatigue loads and power prediction method for wind turbines under yaw control. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 120013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Xing, Y. AK-MDAmax: Maximum fatigue damage assessment of wind turbine towers considering multi-location with an active learning approach. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño-Valencia, L.D.; Abdallah, I.; Chatzi, E. Virtual fatigue diagnostics of wake-affected wind turbine via Gaussian Process Regression. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 539–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Ding, Z.; Huang, X. Probabilistic model for fatigue damage estimation of wind turbines with hidden markov model and neural network. Ocean Eng. 2024, 310, 118663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShannaq, H.; Aly, A.M. Review of Artificial Neural Networks for Wind Turbine Fatigue Prediction. SDHM Struct. Durab. Health Monit. 2024, 18, 707–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Jang, B.-S.; Park, C.-K.; Bae, Y.H. Fatigue analysis of floating wind turbine support structure applying modified stress transfer function by artificial neural network. Ocean Eng. 2018, 149, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziane, K.; Ilinca, A.; Karganroudi, S.S.; Dimitrova, M. Neural Network Optimization Algorithms to Predict Wind Turbine Blade Fatigue Life under Variable Hygrothermal Conditions. Eng 2021, 2, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, J.; Falkenberg, O.; Gros, S.; Schild, A. Wind turbine fatigue reduction based on economic-tracking NMPC with direct ANN fatigue estimation. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 1632–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Z. Fatigue analysis of wind turbine and load reduction through wind-farm-level yaw control. Energy 2025, 326, 136266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babbar, S.; Lau, C. Medium term wind speed forecasting using combination of linear and nonlinear models. Solid State Technol. 2020, 63, 874–882. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Lv, X.; Wu, Q.; Zhu, B. Probabilistic prediction of wind power based on improved Bayesian neural network. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 11, 1309778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blfgeh, A.; Alkhudhayr, H. A Machine Learning-Based Sustainable Energy Management of Wind Farms Using Bayesian Recurrent Neural Network. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, A. Damage equivalent load synthesis and stochastic extrapolation for fatigue life validation. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 1171–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-1; Design Requirements for Wind Turbines. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Sun, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, H.; Gao, S.; Wang, B.; Ying, Y.; Sun, Y.; Qian, P.; Zhang, D.; Si, Y. Quantitative evaluation of yaw-misalignment and aerodynamic wake induced fatigue loads of offshore Wind turbines. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogirou, S.A. Artificial neural networks in renewable energy systems applications: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2001, 5, 373–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampinen, J.; Vehtari, A. Bayesian approach for neural networks—Review and case studies. Neural Netw. 2001, 14, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linka, K.; Holzapfel, G.A.; Kuhl, E. Discovering uncertainty: Bayesian constitutive artificial neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2025, 433, 117517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucukelbir, A.; Ranganath, R.; Gelman, A.; Blei, D.M. Automatic variational inference in Stan. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems-Volume 1, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; pp. 568–576. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).