Featured Application

The portable Kubernetes cluster supports on-site machine learning and web services in remote or resource-limited environments. It is applicable to field research, disaster response, military, and security operations requiring local autonomous, reliable, and secure computing capabilities. The cluster is intended to operate as a standalone computing device in a remote or isolated deployment, hosting local web services for information dissemination and enabling on-site retraining of AI models (e.g., for new enemy platform types) using data collected in the field.

Abstract

This paper presents a portable cluster architecture based on a lightweight Kubernetes distribution designed to provide enhanced computing capabilities in isolated environments. The architecture is validated in two operational scenarios: (1) machine learning operations (MLOps) for on-site learning, fine-tuning and retraining of models and (2) web hosting for isolated or resource-constrained networks, providing resilient service delivery through failover and load balancing. The cluster leverages low-cost Raspberry Pi 4B units and virtualized nodes, integrated with Docker containerization, Kubernetes orchestration, and Kubeflow-based workflow optimization. System monitoring with Prometheus and Grafana offers continuous visibility into node health, workload distribution, and resource usage, supporting early detection of operational issues within the cluster. The results show that the proposed dual-mode cluster can function as a compact, field-deployable micro-datacenter, enabling both real-time Artificial Intelligence (AI) operations and resilient web service delivery in field environments where autonomy and reliability are critical. In addition to performance and availability measurements, power consumption, scalability bottlenecks, and basic security aspects were analyzed to assess the feasibility of such a platform under constrained conditions. Limitations are discussed, and future work includes scaling the cluster, evaluating GPU/TPU-enabled nodes, and conducting field tests in realistic tactical environments.

1. Introduction

Reliable computing in remote or resource-constrained environments remains a persistent challenge, often limited by hardware constraints, intermittent connectivity, and the lack of scalable infrastructures [1,2,3]. Cloud computing centralizes data processing and storage in remote data centers, requiring reliable, high-bandwidth network connections to transmit large volumes of data between end devices and the cloud [4,5]. Traditional cloud solutions, while powerful, are dependent on stable high-bandwidth links [6] and often become infeasible for operations in disconnected, bandwidth-limited and adversarial environments because they require stable, high-throughput connections to centralized datacenters. Examples of such scenarios could include defense, environmental monitoring, or emergency response actions.

These scenarios require reliable, low-latency, and resilient systems that traditional centralized clouds struggle to deliver due to their inherent network dependencies and resource allocation models [7,8,9]. Transmitting data for centralized processing introduces security vulnerabilities, particularly in military or tactical environments where adversaries may intercept, jam, or exploit communications. In such scenarios, a solution that processes information using local resources can enhance security by providing a rapid, agile solution without relying on vulnerable long-range communication links or external cloud services.

To contextualize these challenges, it is essential to note that current research in distributed computing relies on the Cloud–Edge–IoT continuum, a unified architectural model in which computation is strategically placed across cloud datacenters, intermediate edge nodes, and resource-constrained devices close to the data source [10]. This paradigm aims to minimize end-to-end latency, reduce dependence on long-haul links, and maintain operational continuity when connectivity is contested or unavailable [11]. Within this continuum, edge computing specifically focuses on relocating data processing, storage and decision-making to local platforms to improve responsiveness and preserve data confidentiality in environments where backhaul links may be unreliable or unavailable. This perspective provides the conceptual foundation for evaluating lightweight Kubernetes distributions on small hardware, as field-deployed clusters must operate autonomously without relying on traditional long-distance, high-bandwidth cloud connections [12].

In recent years, lightweight Kubernetes distributions such as MicroK8s and K3s have emerged as state-of-the-art solutions for edge and field deployments [13,14,15,16]. These platforms provide container orchestration with reduced operational overhead and small resource footprints, enabling deployment of low-cost hardware such as Raspberry Pi 4B clusters. Comparative studies indicate that MicroK8s offers a modular and easy-to-cluster solution, while K3s is highly optimized for ARM-based architectures and ultra-low-resource nodes, both significantly outperforming full-scale Kubernetes distributions in constrained environments [17]. In parallel, advances in containerization and orchestration have demonstrated the ability to run scalable machine learning (ML) pipelines and web services at the edge, supported by Dockerized workloads and automated orchestration via Kubernetes [18].

Performance optimization strategies have also been proposed to improve workload distribution and fault tolerance, including ML-assisted scheduling and resource-adaptive load balancing mechanisms. Research shows that such strategies reduce latency and increase throughput compared to default Kubernetes schedulers, thereby enhancing the resilience of clusters in unreliable networks [19,20,21]. At the monitoring layer, integration with Prometheus and Grafana has become a standard practice, offering real-time observability, visualization, and proactive fault detection [22,23]. Together, these tools form a mature ecosystem for edge-oriented deployments, transforming lightweight clusters into computing platforms capable of sustaining mission-critical tasks.

Existing work on lightweight Kubernetes for edge computing still exhibits several shortcomings when applied to highly constrained, field-deployable clusters based on single-board computers. First, most studies assume relatively stable power and networking conditions, whereas tactical deployments must cope with limited energy budgets and intermittent links. Second, many evaluations rely on synthetic benchmarks rather than on practical ML retraining tasks or real web-service deployments. Third, security considerations are often addressed only at a high level, even though they are important in demanding or high-risk environments. As a result, it remains uncertain whether lightweight Kubernetes distributions can adequately provide the performance–cost–reliability trade-off necessary for practical use in field environments.

This paper investigates whether a small, PoE-powered Raspberry Pi 4B cluster running MicroK8s can serve as a standalone computing device for remote environments, in scenarios with no connectivity or operations carried out in harsh electromagnetic environments. In this setup, the cluster must host local web services for information dissemination and support on-site retraining of AI models used by field equipment.

Building on these advances, this study addresses the practical problem of deploying a portable Kubernetes cluster tailored for constrained field conditions. The proposed infrastructure, developed on Raspberry Pi 4B units interconnected via a PoE switch, is optimized for two operational scenarios:

- a.

- ML operations in remote environments—The cluster enables on-site (where the data is generated) model training/retraining, eliminating the need for high-bandwidth backhaul to cloud services. This is critical for low-latency decision-making in mission-critical applications such as environmental monitoring or security analytics. While the paper uses network anomaly detection as the ML workload, this example illustrates the applicability of the proposed system to real operational scenarios such as on-site model updates for novel target type detection/tracking.

- b.

- Web hosting in isolated networks—The same orchestration framework can host containerized web applications in a high-availability configuration, serving dashboards, Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), or data visualization tools to local clients without connectivity.

The core scientific and engineering question of this work is whether a low-cost Raspberry-Pi-based MicroK8s cluster can offer a practical balance of performance, cost, and reliability for ML retraining and web-service workloads in environments characterized by limited power, unstable networking, and heightened security constraints typical of remote tactical deployments. Addressing this question involves both demonstrating that such workloads can operate on the platform and evaluating their performance; identifying key bottlenecks in CPU, networking, and power availability; and determining whether the system meets real field requirements for autonomy, resilience, and secure operation.

Therefore, the main objective of this paper is to design, implement, and validate a field-deployable Kubernetes architecture that balances portability, scalability, and operational resilience. This is achieved by integrating containerization (Docker), orchestration (MicroK8s), and workload optimization (Kubeflow), complemented by performance monitoring (Prometheus and Grafana). The study aims to demonstrate that low-cost, lightweight clusters can serve as compact, field-deployable micro-datacenters. The study’s contribution lies in delivering a practical and adaptable MicroK8s-based Raspberry Pi cluster that demonstrates how low-cost, field-ready infrastructure can support ML retraining and web services in remote environments while maintaining autonomy, reliability, and acceptable scalability. The originality of this work does not lie in proposing a new Kubernetes distribution but in the end-to-end design, deployment, and analysis of a real MicroK8s cluster on Raspberry Pi hardware under realistic constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the materials and methods used for setting up the Kubernetes cluster. The section is divided into two parts: the hardware setup, which also includes network and orchestration details, and the software stack.

2.1. Hardware Configuration

The cluster hardware is built around a Power over Ethernet (PoE) switch (8 ports, model TL-SG1210P, TP-Link Technologies Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), which serves as both the primary power distribution unit and the central network backbone. This switch is connected to a management workstation (PC/Laptop) and a variable number of Raspberry Pi 4B devices—ranging from a minimal two-node setup to a maximum of eight nodes—each equipped with 4GB/8GB of RAM (Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK). Every Pi is fitted with a PoE Hat (Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK), enabling power delivery directly over the Ethernet interface, thereby eliminating the need for separate power adapters.

One of the Pi units (or a designated workstation) is designated as the head node, running the MicroK8s control plane and handling Kubernetes orchestration for the entire cluster. The remaining Raspberry Pi units act as worker nodes, executing workloads assigned by the control plane.

When operating outside the cluster, the management workstation provides administrative control, including running deployment commands to initiate new workloads, managing configuration files and sending them to the cluster, accessing the Kubernetes Dashboard, and monitoring platforms (Prometheus and Grafana).

PoE-based cluster design offers several practical advantages for field deployment. By using a single Cat6 cable to supply both power and data to each node, the setup significantly reduces cable clutter and simplifies physical layout. Centralized power control through the PoE switch management interface allows operators to remotely power nodes on or off without manual intervention, streamlining maintenance and troubleshooting. Furthermore, the combination of minimal cabling and integrated power delivery enables rapid system deployment, making the cluster well-suited for quick setup in remote or tactical environments where time and efficiency are critical.

A summary of component-level power consumption is provided to contextualize the cluster’s energy requirements in field conditions. Table 1 lists idle, medium, and maximum loads for Pi boards, PoE+ Hats, Solid State Drives (SSDs), and PoE losses, along with the power usage of the PoE switch. Power-consumption values in Table 1 were derived from manufacturer datasheets, published data [24] and technical documentation.

Table 1.

Component-level power consumption for the field-deployable cluster.

Using these values, total cluster consumption for five nodes ranged from approximately 24 W at idle to 75–94 W under typical activity, with short peaks of 110–128 W during ML tasks. These values indicate that the cluster remains operable on compact inverter generators with low fuel usage, making it suitable for deployments with limited energy resources.

A dedicated private subnet (192.168.50.0/24) was configured to interconnect the Raspberry Pi nodes and the management system. Each device was assigned a static IPv4 address to ensure deterministic communication and avoid Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP)-related variability. Network integrity was verified via Internet Control Message Protocol (ICMP) echo requests between nodes.

Kubernetes orchestration was provided by MicroK8s (version 1.32) [16], installed on all nodes using the Snap package manager (2024 stable). Post-installation, user permissions and local Kubernetes configuration directories were adjusted to enable non-privileged command execution. Node readiness was confirmed, and cluster membership was verified.

Lightweight Kubernetes distributions (MicroK8s, K3s, k0s, MicroShift, KubeEdge) each exhibit limitations when deployed on constrained edge hardware. No single distribution is universally optimal, and the selection depends on workload, hardware constraints, and operational priorities. K3s and k0s consistently demonstrate the lowest memory and CPU consumption, making them best suited for highly resource-constrained edge devices [25]. MicroK8s has been reported to consume more memory than K3s or k0s in some scenarios but provides stronger built-in add-on support and easier extensibility [17,26].

MicroK8s was selected over K3s, k0s, and MicroShift for several reasons, including the following: (i) MicroK8s offers very simple installation and automatic high-availability activation for clusters with at least three nodes; (ii) it includes pre-built add-ons (dashboard, Prometheus, MetalLB, etc.) that can be enabled with a single command, which is advantageous in time-critical field setups; and (iii) it integrates smoothly with Ubuntu and Snap-based updates. Although K3s and k0s show lower control-plane overhead in benchmarks, MicroK8s provides a better operational fit for the defined objective, where reliability, ease of maintenance, and rapid deployment outweighs small performance differences. Table 2 presents a synthetic comparison of the key metrics of the various Kubernetes distributions, according to [17].

Table 2.

Comparative assessment of various Kubernetes distributions.

In summary, existing solutions either assume more powerful hardware and stable networking than available in the targeted scenario, or require non-trivial integration effort to achieve observability, High Availability (HA), and registry support. This motivates the present work on a MicroK8s-based Raspberry-Pi cluster tuned specifically for remote, tactical operation.

Cluster formation was initiated by designating one Raspberry Pi as the control plane (head node), which generated a join token. Worker nodes were integrated into the cluster using the join command with the -worker flag, and successful registration was confirmed from the head node. All orchestration and deployment operations were subsequently executed from the control plane.

Node removal was performed by using the designated command (microk8s leave). For clusters with more than 3 nodes, HA feature, enabled by default in MicroK8s, ensured datastore replication and resilience against single-node failures. This configuration provided a stable, statically addressed network, centralized orchestration, and fault-tolerant operation suitable for remote platform deployments.

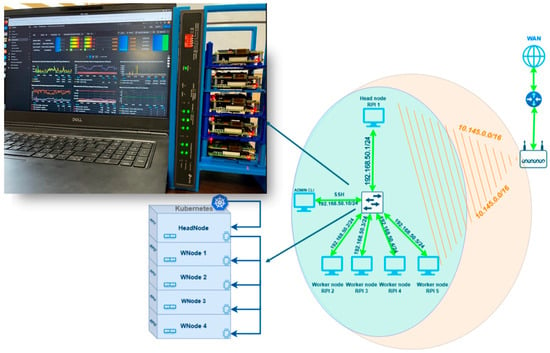

Figure 1 presents the physical layer configuration for the field-deployable Kubernetes cluster with 5 enabled nodes (1 head node and 4 working nodes). A custom designed case was constructed to house the PoE switch and worker nodes for ensuring fast deployment, portability, scalability and mobility in the field. For the initial deployment, the PoE switch was connected to the internet via Wi-Fi (using a router) to facilitate software installation and configuration. This connection was removed once the setup was complete, leaving the cluster to operate as an isolated, self-contained network.

Figure 1.

Field-deployable Kubernetes cluster with physical layer configuration.

2.2. Software Stack

The software stack was designed to enable portable, reproducible, and scalable machine learning (ML) and web hosting in remote environments.

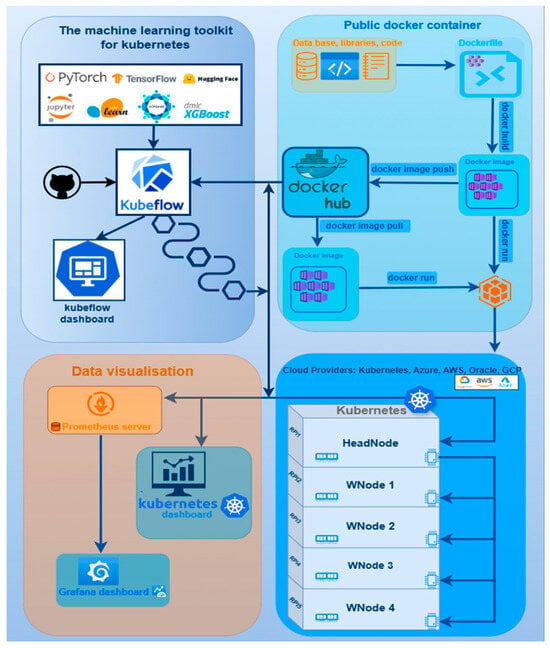

The field-deployable cluster operates on Ubuntu 22.04 (64-bit) and leverages MicroK8s [13] for lightweight Kubernetes orchestration, chosen for its minimal footprint and compatibility with Advanced RISC Machine (ARM)-based architectures. The proposed architecture for the local Kubernetes cluster is presented schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Kubernetes cluster architecture.

The software stack incorporates the following core components:

- Kubeflow [27]—Provides an integrated ML operations framework for building, training, deploying, and monitoring ML models in a Kubernetes-native environment. PyTorch (v 2.1.0), TensorFlow (v 2.12), Scikit-learn (v 1.3), XGBoost (v. 1.7.6), and Jupyter Notebooks (base-notebook, 2024 release) serve as the primary interactive development interface for data analysis, model prototyping, and experiment documentation. Applications are deployed using Kubernetes manifests written in YAML (YAML Ain’t Markup Language), a human-readable format for defining Kubernetes resources. YAML manifests describe Deployments (container images, replica counts, resource limits) and Services (network exposure, load balancing). Kubeflow Pipelines orchestrate containerized ML workflows, supporting automated hyperparameter optimization, batch processing, and real-time retraining using new data collected in the field.

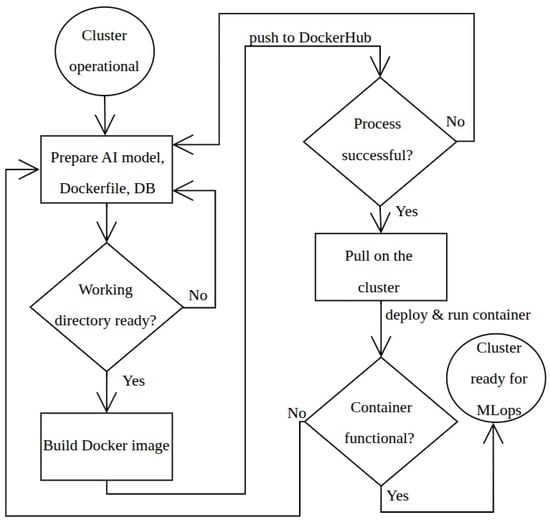

- Dockerization [28]—Used for containerizing ML models and application services, ensuring portability and reproducibility across heterogeneous computing environments. A developer creates a Dockerfile that specifies the environment, libraries, and code for their application. This Dockerfile is used to build a Docker image. Once the image is created, it is pushed to a Docker Hub repository. This centralized repository acts as a public or private registry for storing and sharing container images. Other users or the Kubernetes cluster can then pull this image from Docker Hub to run the application, ensuring consistency and portability across different environments. The diagram in Figure 2 presents the flow used to create, push, and run a Docker image. In the remote environment scenario considered in this manuscript, on-premises container registry will serve the function of Docker Hub to manage and distribute images within the isolated network. This built-in registry was selected because it requires minimal configuration, operates without external dependencies, and is suitable for field environments where connectivity is limited or unavailable. All images used in the ML and web-hosting scenarios were pushed to this internal container registry and distributed to worker nodes through MicroK8s’ native image-sync mechanisms. Although Harbor or other enterprise-grade registries (e.g., OCI-compliant registries integrated with CI/CD or GitOps workflows) offer more advanced features, these will be considered for future extensions of the platform. A simplified diagram for MLOps Docker pipeline for model deployment on cluster is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. MLOps Docker pipeline for model deployment on cluster.

Figure 3. MLOps Docker pipeline for model deployment on cluster.

- Data visualization and monitoring were configured using Prometheus [29] and Grafana [30]. Prometheus collects time-series metrics from all cluster nodes, including CPU load, memory utilization, and network throughput. The collected data is then visualized using Grafana, which provides a powerful and customizable dashboard for real-time monitoring. This setup allows administrators and developers to keep track of the cluster’s health and performance. The diagram in Figure 2 shows a Prometheus server feeding data to a Grafana dashboard, providing a visual representation of the cluster’s operational status.

The entire code used for setting up the cluster is presented in a dedicated GitHub repository available at [31]. The described architecture was tested for the two defined operational scenarios, and the results are presented in the following sections.

3. Kubernetes Cluster Deployment for ML Operations—Performance Evaluation

The ML application chosen for this scenario focuses on traffic anomaly detection within a local computer network. The baseline dataset was derived from the KDD intrusion detection dataset [32], which contains labeled records classified as either normal or attack. The version utilized in this work, constructed in 2019, includes traffic instances from three network protocols—Transmission Control Protocol (TCP), User Datagram Protocol (UDP), and ICMP. Given the increasing complexity and diversity of contemporary cyber-attacks, continuous dataset updating and periodic retraining of the detection model are essential to maintain detection accuracy and relevance. The goal of this experiment is to determine whether on-site model updates can be executed reliably and with acceptable performance compared to cloud-based execution, and to assess the cluster’s ability to run replicated workloads across heterogeneous nodes.

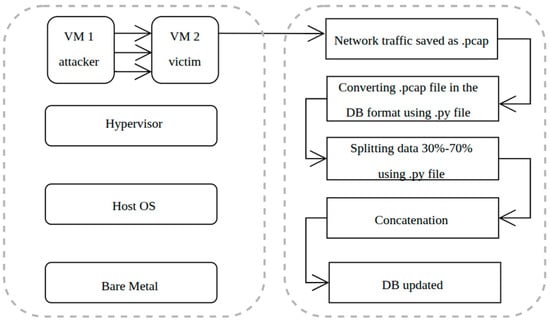

To address this requirement, a controlled virtualized environment was configured to simulate and capture network traffic associated with two representative modern attack types: the SYN flood attack, which targets network resource exhaustion by initiating a high volume of incomplete TCP connection requests, and the sniffing attack, which intercepts network packets to extract potentially sensitive information. The resulting data was incorporated into the training set to extend the model’s detection capabilities beyond the original dataset scope.

A virtual environment with dedicated attackers and victim machines was set up to capture network traffic. The captured files were reformatted to match the original dataset structure, merged with the existing data, and used to retrain the anomaly detection model. The update workflow is shown in Figure 4. The primary objective of this paper is to evaluate and demonstrate the capabilities of the proposed cluster architecture; therefore, a detailed exposition of the specific ML algorithm employed is beyond the scope of this work. The complete source code for the database update process and the ML implementation is available and explained in [33].

Figure 4.

Anomaly detection database updating framework.

The ML algorithm was packed in a deployable container and ran on the proposed architecture. It is worth noting that the initial tests were performed on virtual machines before migrating to physical hardware; as a result, some documentation may still reference virtual machines, although the operating system and commands used remain the same.

The anomaly detection workflow used in this study is based on a Random Forest classifier trained using an 80/10/10 train–validation–test split. The retraining step, performed after adding the SYN-flood and sniffing traffic, yielded a modest but measurable improvement, with overall accuracy increasing from 92.1% to 94.8% and recall for SYN-flood attacks rising from 88% to 93%. These values are not intended as a comprehensive ML performance evaluation. They demonstrate that the proposed field-deployable micro-datacenter can reliably execute on-site model updates using operational data, which is the core proof-of-concept targeted by this work.

The deployment environment is defined through a Dockerfile derived from jupyter/base-notebook image, extended with the project’s source files and required Python (v. 3.10) dependencies. The resulting container provides a consistent execution environment for the anomaly-detection workflow used in this study.

The Docker image was built and validated locally to ensure portability and reproducibility and subsequently published to a public container registry. A multi-architecture installation was created to support both linux/amd64 and linux/arm64 platforms, ensuring compatibility across heterogeneous systems.

Running the container launches a Jupyter Notebook server that hosts the experimental pipeline. Within this environment, anomaly detection workflows can be executed directly, including dataset loading, preprocessing, model training, evaluation, and visualization.

This workflow, from Dockerfile creation to Hub publication and container execution, ensures a portable, reproducible, and scalable environment for data science simplifying deployment in both standalone and Kubernetes-managed infrastructures.

Initially, the Docker image was run solely on the available management workstation (Intel Core i7processor featuring 10 cores manufactured by Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA, 16 GB of RAM, and a 2 TB external SSD for virtual machine storage) and the execution crashed. After setting up the cluster, several configurations were investigated, and the comparative result of their corresponding run-time is presented in Table 3. All runtime measurements reported in Table 3 were obtained through five repeated executions of each configuration. The values in the table represent the mean runtime, with deviations across repetitions remaining below ±3%, which is consistent with the deterministic CPU-bound nature of the workload.

Table 3.

Comparative run time result for Kubernetes cluster configurations.

Although the anomaly-detection workflow is containerized as a single application rather than decomposed into microservices, Kubernetes still distributes the computation by scheduling multiple container replicas across the available Raspberry Pi nodes. Each replica processes an assigned subset of the dataset in parallel, and the intermediate results are aggregated at the end of the run. Thus, the performance improvements reported in Table 3 reflect genuine parallel execution, where multiple nodes work simultaneously on different partitions of the computation, rather than microservice decomposition. In configuration 4 (“Management workstation + 5 WN, all active”), Kubernetes successfully scheduled all replicas across heterogeneous nodes, enabling concurrent execution and achieving the shortest runtime among local deployments.

In the initial phase, the container was tested with a direct docker run command on the management workstation to validate dependencies and ensure that the image was executed correctly in a controlled environment. However, all reported performance measurements were obtained only after deploying the container through Kubernetes.

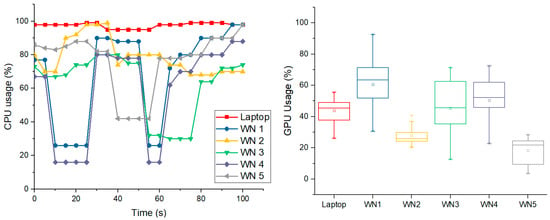

In the partially balanced configuration (Management workstation + 5 WN with only two active worker nodes), runtime was significantly reduced compared to the Raspberry Pi–only configuration, but performance remained suboptimal due to inefficient resource allocation. When scheduling was tuned to fully utilize all nodes (Management workstation + 5 WN, all active), runtime decreased to approximately one-twelfth of the Raspberry Pi–only case, illustrating the value of heterogeneous resource integration and proper orchestration tuning. This corresponds to an improvement of approximately a factor of twelve. For this optimal case, Figure 5 presents the CPU and GPU usage.

Figure 5.

CPU (left) and GPU (right) variability for setup no. 4 in Table 3.

The management workstation’s CPU maintained near-maximum utilization (approximately 98–99%) throughout the run, while the Raspberry Pi worker nodes displayed more fluctuation, with occasional drops in activity on nodes such as WN1 and WN2 likely caused by scheduling delays or data transfer bottlenecks. GPU usage followed the same general trend but at lower overall levels, reflecting both the computational demands of the model and the more limited GPU capabilities of the devices. Certain nodes, notably WN5, showed consistently lower GPU activity, suggesting an uneven distribution of processing tasks or hardware constraints. These patterns align with the runtime data in Table 3, demonstrating how differences between nodes influence workload distribution and resource use during execution.

It is important to note that the use of Docker containers introduces an inherent performance overhead compared to native execution. This occurs because containerization adds abstraction overhead, Kubernetes introduce extra latency, and inter-container communication, especially across networked nodes, increases data transfer times. Furthermore, ML workloads packaged in containers may require additional initialization steps, such as loading large model weights or environment dependencies, before computation begins. While these effects can increase runtime, the benefits of containerization (portability, reproducibility, and simplified deployment) generally outweigh the performance penalty, particularly in heterogeneous or distributed environments.

For benchmarking purposes, Google Colab’s TPU, GPU, and CPU instances were evaluated. Predictably, the TPU delivered the fastest execution (42.3 s), followed by GPU and CPU modes. While cloud-based solutions outperformed the local cluster at raw speed, they require continuous internet connectivity and may not be feasible in isolated or security-sensitive deployments.

Our results demonstrate that, although locally built low-cost clusters cannot match the performance of cloud accelerators, careful orchestration and load balancing can produce reliable, low-latency processing capabilities in field environments. This trade-off between absolute speed and operational independence underlines the practical advantage of the proposed architecture for remote ML workloads in disconnected or bandwidth-limited scenarios.

To further assess the operational efficiency of the field-deployable Kubernetes cluster, a series of benchmark and monitoring tests were conducted, comparing a single-node deployment to a three-node cluster configuration. The hardware specifications are the same as described in Section 2. The results, summarized in Table 4, quantify the impact of distributed orchestration on system resource utilization, throughput, and fault tolerance. Both K6 and Apache Benchmark (ab) tests were repeated five times, with throughput and latency variations staying within ±5%. All measurements were performed from the management workstation connected through the same switch, ensuring a single-hop network path under stable bandwidth (1 Gbps per port). Apache Benchmark was executed locally on this machine, using repeated trials (five runs per test) and reporting the mean values; variance remained low, with latency fluctuations within ±0.4 ms across repetitions.

Table 4.

Comparative performance metrics for single-node and three-node Kubernetes cluster configurations.

The single node setup provided a baseline for evaluating the benefits of the Kubernetes cluster. Under load testing, the single node reached resource capacity, with CPU usage peaking at 35% and memory capped at 6 GB. While the system managed to handle 15,000 requests per second, its response time averaged 10.5 ms, and a small percentage of requests (0.5%) failed due to resource contention. This limitation underscored the inherent constraints of a standalone node, particularly for high-demand applications.

The three-node Kubernetes cluster addressed these limitations by distributing workloads across nodes, significantly enhancing performance and reliability. CPU usage across the cluster averaged 15–20% during load tests, and memory consumption was evenly distributed, with 4 GB used by the head node and 2 GB per worker node. This distribution resulted in a 65% increase in throughput (24,823 requests/s) and a 62% reduction in response time (4.03 ms), all while maintaining a 100% success rate. The integration of MetalLB [34] ensured seamless load balancing and HA, with failover mechanisms enabling the cluster to redirect traffic to remaining nodes within 200 ms in the event of a node failure.

Scaling efficiency was another significant advantage of the proposed architecture. Adding additional containerized workloads demonstrated the cluster’s ability to allocate resources dynamically, achieving an efficiency rate of 85–90% without noticeable performance degradation. This adaptability positions the cluster as a robust solution for workloads requiring elasticity, such as machine learning pipelines or high-traffic web applications.

4. Kubernetes Cluster for Web Hosting—Implementation and Testing

For the second testing scenario, the deployment of a static web application within a Kubernetes cluster involved a sequence of containerization, configuration, and orchestration steps. The experimental goal of this section is to evaluate throughput, latency, and failover performance under controlled load, and determine whether the multi-node cluster provides measurable benefits over a single-node deployment. Initially, the web content was prepared as an HTML file (index.html), which was subsequently containerized into a Docker image. The containerization process enabled the encapsulation of the application and its dependencies into a portable unit that could be deployed consistently across environments. Once the Docker image was created, it was exported as a .tar file to facilitate its transfer into the cluster. This step is relevant in scenarios where a Docker registry is not directly accessible. The imported image was then made available within the cluster using the microk8s.ctr image import command.

To provide external access to the application, the MetalLB load balancer was configured through a dedicated YAML file. This configuration defined the IP address pool from which MetalLB dynamically allocated external IPs to Kubernetes services. Three additional YAML configuration files were employed for orchestrating the deployment: the deployment file (defining the pod specifications), the service file (exposing the application internally within the cluster), and the ingress file (defining routing rules for external access). Together, these resources ensured that the web application was deployed, exposed, and accessible from external clients.

After applying the configuration files to the cluster, verification was conducted to ensure correct scheduling and service exposure. The pods were confirmed to reach a stable running state, and the service was successfully assigned an external network endpoint. To improve usability, the dynamically assigned IP address was mapped to a human-readable hostname. This allowed seamless access to the application using a descriptive URL rather than a raw IP address. As a result of these steps, the web application was successfully hosted within the Kubernetes cluster and made accessible both locally and on the local network.

With the cluster configured in a HA setup across three virtual machines, penetration and performance testing were conducted to evaluate the robustness of the deployment. Two Linux-based benchmarking tools, K6 [35] and Apache Benchmark [36], were employed to simulate user load and measure server responsiveness under stress conditions.

For the first experiment, a JavaScript-based scenario file (load-test.js) was created to define the workload executed by K6. The test simulated 100 concurrent virtual users performing HTTP GET requests against the deployed application for a duration of 30 s. Each request was validated to ensure a successful response (HTTP status code 200). The test provided insights into how the application handled simultaneous access patterns that closely resemble real-world traffic conditions.

In the second experiment, Apache Benchmark was used to further evaluate throughput and response time under high concurrency. The tool executed 10,000 HTTP requests at a concurrency level of 100 parallel requests. This configuration tested the limits of the server’s request-handling capacity and provided detailed statistics regarding connection times, transfer rates, and request distribution. The combined results of the two tests are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of load testing results for the Kubernetes-deployed web application.

Both experiments confirmed that the web application maintained full stability under load, with no failed requests observed. The K6 test validated the system’s ability to sustain concurrent user sessions over an extended duration, while the Apache Benchmark test demonstrated the cluster’s capacity to process a large burst of requests in a very short interval. Together, these findings confirm that the Kubernetes deployment is capable of handling high traffic volumes while ensuring low latency, high throughput, and predictable performance.

5. Kubernetes Cluster Monitoring Solutions

For this project, Kubernetes monitoring was approached at multiple levels. First, we implemented the Kubernetes Dashboard for basic cluster management and workload status. Then we extended the monitoring capabilities by enabling Prometheus and Grafana monitoring solutions that implement advanced metrics collection, visualization, and alerting. Together, these tools offer real-time observability of pod performance, resource consumption, and overall system health.

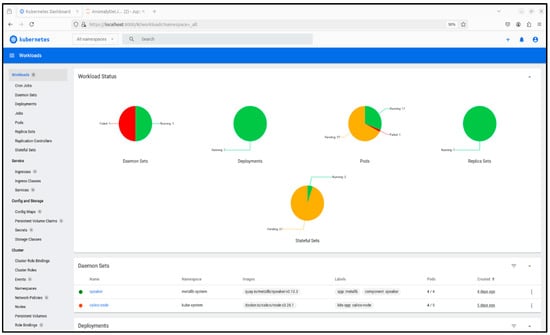

In MicroK8s, the Kubernetes Dashboard is enabled with microk8s enable dashboard, after which its status can be confirmed using microk8s status. Secure access requires an authentication token retrieved from the kubernetes-dashboard namespace. The interface can then be accessed in two ways: locally, by starting a proxy with microk8s kubectl proxy and navigating to the generated API URL in a browser, or cluster-wide, by modifying the dashboard service type from ClusterIP to NodePort, which exposes it on a dynamically assigned port (30,000–32,767) retrievable via kubectl. In both cases, authentication is completed using the generated token, with the browser displaying a warning for the self-signed certificate that must be acknowledged. Once operational, the Kubernetes Dashboard provides real-time insights into cluster workloads, node health, and resource utilization. Such a display for the proposed cluster is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Kubernetes dashboard overview of workload status.

To extend observability beyond the Kubernetes Dashboard, Prometheus was deployed in a dedicated monitoring namespace on MicroK8s. The setup required enabling Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) to allow Prometheus to scrape metrics from cluster components such as nodes, pods, services, and ingress controllers. The permissions were defined in a ClusterRole and bound to the Prometheus service account via a ClusterRoleBinding.

The Prometheus configuration was externalized using a ConfigMap (e.g., prometheus.yaml), which defined scrape targets for the Kubernetes API server, nodes, pods, and cAdvisor. This configuration ensured automated discovery of metric endpoints without manual intervention. The Prometheus server was then deployed as a Kubernetes Deployment using the official prom/prometheus image, with resources constrained to 1 CPU and 1 GB RAM, and with port 9090 exposed for the web interface and API.

Access to Prometheus was established through kubectl port-forwarding, mapping the Prometheus pod to a local port (localhost:8080). This interface allowed for direct inspection of collected metrics, execution of PromQL queries, and visualization of time-series data such as CPU usage, memory consumption, and filesystem utilization. Prometheus also maintained a registry of all monitored targets, enabling administrators to validate the health and responsiveness of nodes and services. Figure 7 presents the implemented Prometheus targets monitoring the Kubernetes nodes.

Figure 7.

Prometheus targets monitoring Kubernetes nodes.

To complement Prometheus, Grafana was deployed within the monitoring namespace to provide visualization and dashboarding capabilities. A ConfigMap was first defined to configure Prometheus as the default Grafana data source, enabling direct querying of metrics collected from the cluster. The deployment specification described a single replica of the official Grafana image, resource limits, persistent storage, and provisioning of the data source configuration. Grafana was exposed via a NodePort service (port 32,000) for external access, with an alternative option of port forwarding for local use.

Once deployed, the Grafana interface was accessible through the web browser, where Prometheus was configured as the data source using the predefined connection settings. Through this integration, metrics such as CPU usage, memory allocation, pod health, and network traffic became queryable using PromQL. Grafana’s customizable dashboards transformed these metrics into interactive visual panels, supporting both system-level and application-level monitoring.

The deployment validated Grafana’s role as the visualization layer in the monitoring pipeline: Prometheus ensured reliable time-series collection, while Grafana provided administrators with intuitive dashboards and the ability to configure alerts for critical thresholds. Together, they enabled comprehensive observability of the Kubernetes cluster, offering actionable insights into performance, scalability, and reliability.

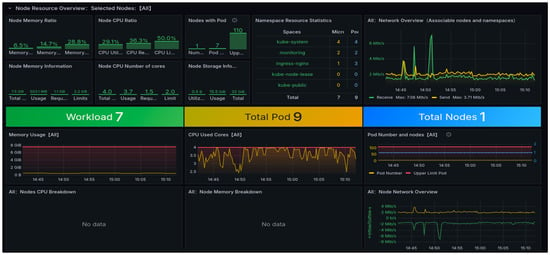

Figure 8 presents the Grafana dashboard obtained for a node overview offering real-time information on node health, resource distribution, and traffic analysis. Key metrics such as memory usage, pod count, node CPU stats, and network I/O are displayed in intuitive visual formats, allowing administrators to identify trends, anomalies, and potential performance bottlenecks.

Figure 8.

Grafana dashboard: kubernetes node resource overview.

6. Security, Scalability and Limitations of the Proposed Solution

The proposed Raspberry Pi 4B–based MicroK8s cluster is designed as a compact, low-power computing platform for remote or isolated deployments, but its practical operation must be understood together with its security posture, scalability characteristics, and hardware-level constraints. From the power consumption perspective, the cluster remains efficient: a five-node configuration consumes approximately 24 W at idle, 75–94 W under typical workloads, and reaches 110–128 W only during short, three-minute daily ML retraining tasks. These values include all components—Raspberry Pi boards, PoE+ HATs, SSDs, PoE conversion losses, and the TL-SG108PE switch—which makes the system suitable for generator-powered outposts or battery-supported missions. When operated on a compact inverter generator, fuel usage remains below 0.11 L/h, enabling 19–23 h of continuous operation on a single 2.1 L tank. This low and predictable power profile simplifies deployment in isolated military or research sites by reducing thermal output, noise, and logistic overhead.

Security considerations are essential in field conditions, where connectivity is limited and physical node access cannot be assumed safe. MicroK8s provides built-in TLS for component communication, RBAC for access control, and mutual-TLS for securing interactions between the API server and nodes, aligning with recommended hardening practices for lightweight Kubernetes systems [37,38,39]. In the proposed operational model, container images are preloaded onto nodes before deployment, eliminating reliance on external registries and reducing exposure to supply-chain or man-in-the-middle attacks. Encrypted volumes are used for datasets and logs associated with ML retraining, ensuring confidentiality even if hardware is physically compromised. Although MicroK8s does not offer the full spectrum of cloud-grade security controls, its default isolation mechanisms, together with the offline deployment model, allow for a realistic and sufficiently robust security posture in remote tactical environments.

Scalability is supported in the form of horizontal expansion through additional Raspberry Pi nodes attached to the PoE switch. Kubernetes can redistribute workloads across these nodes, and failover mechanisms—combined with MicroK8s’ automatic HA activation on clusters with three or more nodes—provide resilience against individual device failure. However, several structural bottlenecks define the practical scaling limits. First, the control plane remains bound to the compute and I/O capacity of a single Raspberry Pi, as MicroK8s integrates the API server, scheduler, controller manager, and dqlite datastore on one board; prior studies show that lightweight distributions exhibit performance degradation under metadata-intensive or highly concurrent operations [17,40]. Second, network throughput becomes constrained as more nodes are chained through PoE switches, increasing latency and reducing stability when the cluster handles frequent pod rescheduling or heavy image transfers. Third, SSD performance, while significantly better than that of SD cards, remains well below server-grade NVMe storage and can become a bottleneck during ML dataset loading or container extraction.

The proposed solution embraces these limitations intentionally, because the design goal is not to match cloud-scale throughput but to provide a reliable, autonomous micro-datacenter capable of running web services and lightweight, daily ML updates in disconnected or bandwidth-restricted environments. Within this operational scope, the cluster demonstrates favorable characteristics: low energy usage, graceful degradation under node failure, quick field deployment due to MicroK8s’ integrated add-ons, and the flexibility to host both web servers and small ML jobs without relying on external infrastructure. Nonetheless, the architecture remains unsuitable for large neural networks, high-throughput data pipelines, or long-term storage-heavy workloads, and its performance is highly dependent on stable intra-cluster networking and the limited compute budget of ARM SBCs.

7. Conclusions

This study presents a portable Kubernetes cluster designed for remote and resource-limited environments, built on low-cost Raspberry Pi 4B nodes and the lightweight MicroK8s distribution. The cluster was validated under two practical scenarios: (1) on-site ML with retraining and (2) isolated web hosting. Results confirm that the proposed system architecture can provide reliable, autonomous computing capabilities without dependence on external cloud infrastructure.

Experimental results highlight the advantages of distributed orchestration, with substantial improvements in execution time, throughput, and system resilience compared to single-node deployments. MetalLB provides effective load balancing and HA failover, while the monitoring stack (Prometheus and Grafana) enables real-time observability of performance, resource utilization, and fault tolerance. Although TPU/GPU accelerators deliver superior raw performance, the proposed architecture provides a practical trade-off between computational efficiency and operational independence, which is critical in tactical or disconnected environments.

Overall, the study demonstrates that lightweight, containerized infrastructures can operate effectively on low-power hardware, enabling compact, field micro-datacenters for applications such as defense, environmental monitoring, and security analytics, where autonomy, agility and resilience are crucial.

Future work will concentrate on scaling and expanding the cluster based on recent advances in distributed and edge intelligence [41] as well as extensive testing in real operational environments. The cluster may also be extended with AI-accelerator HATs or external Edge TPU devices to improve training and inference performance, in line with recent trends emphasizing the benefits of specialized coprocessors for embedded ML workloads [42,43]. Additional efforts will evaluate the system at a larger scale, refine HA mechanisms, and test the platform in real field conditions. Despite its current limitations, the proposed Raspberry-Pi/MicroK8s platform demonstrates a viable proof of concept for autonomous, mission-oriented micro-datacenters designed to operate independently in remote or harsh environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and T.-M.G.; methodology, A.S.; software, T.-M.G. and L.G.; validation, A.S., L.G. and B.K.; formal analysis, T.-M.G. and B.K.; investigation, A.S. and T.-M.G.; resources, B.K. and A.S.; data curation, T.-M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S. and T.-M.G.; writing—review and editing, A.S.; visualization, L.G.; supervision, A.S.; project administration, A.S. and B.K.; funding acquisition, A.S. and B.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to OpenLab Hamburg for their support in developing and printing the 3D model design used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Junior, A.P.; Díez, L.E.; Bahillo, A.; Eyobu, O.S. ML-Driven User Activity-Based GNSS Activation for Power Optimization in Resource-Constrained Environments. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, M.; González, P.; de Farias, C.; Delicato, F. AFRODITE—Optimizing Federated Learning in Resource-Constrained Environments Through Data Sampling Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Pervasive and Intelligent Computing (PICom), Boracay Island, Philippines, 5–8 November 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Lei, L.; Wang, Y.; Jing, J.; Wan, S. CacheIEE: Cache-Assisted Isolated Execution Environment on ARM Multi-Core Platforms. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyani, Y.; Collier, R. A Systematic Survey on the Role of Cloud, Fog, and Edge Computing Combination in Smart Agriculture. Sensors 2021, 21, 5922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, B.; Yahya, W.; Lin, Y.; Ali, A. Offloading Using Traditional Optimization and Machine Learning in Federated Cloud–Edge–Fog Systems: A Survey. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanarayanan, M.; Schuster, R.; Ebling, M.; Fettweis, G.; Flinck, H.; Joshi, K.; Sabnani, K. An open ecosystem for mobile-cloud convergence. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2015, 53, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, R.; Mini, R.; Skarin, P.; Gustafsson, H.; Harmatos, J.; Abeni, L.; Cucinotta, T. A Multi-Domain Survey on Time-Criticality in Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2025, 18, 1152–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masip-Bruin, X.; Marín-Tordera, E.; Sánchez-López, S.; García, J.; Jukan, A.; Ferrer, A.; Queralt, A.; Salis, A.; Bartoli, A.; Cankar, M.; et al. Managing the Cloud Continuum: Lessons Learnt from a Real Fog-to-Cloud Deployment. Sensors 2021, 21, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W. Research on Lightweight Microservice Composition Technology in Cloud-Edge Device Scenarios. Sensors 2023, 23, 5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkonis, P.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; D’Andria, F. A Survey on IoT-Edge-Cloud Continuum Systems: Status, Challenges, Use Cases, and Open Issues. Future Internet 2023, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; Facca, F.; Spantideas, S.; Giannopoulos, A.; Kapsalis, N.; Martins, R.; Bosani, E.; Molinas-Ramón, J.; Prats, R.; et al. A Reference Architecture for Cloud–Edge Meta-Operating Systems Enabling Cross-Domain, Data-Intensive, ML-Assisted Applications: Architectural Overview and Key Concepts. Sensors 2022, 22, 9003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturzinger, E.; Lowrance, C.; Faber, I.; Choi, J.; MacCalman, A. Improving the performance of AI models in tactical environments using a hybrid cloud architecture. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Multi-Domain Operations Applications III, Online, 12–17 April 2021; Volume 11746, p. 1174607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjorveziroski, V.; Filiposka, S. Kubernetes distributions for the edge: Serverless performance evaluation. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 13728–13755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqasizade, H.; Ataie, E.; Bastam, M. Kubernetes in Action: Exploring the Performance of Kubernetes Distributions in the Cloud. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2025, 55, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Ferlin, S.; Brunstrom, A. Performance Analysis of Lightweight Container Orchestration Platforms for Edge-Based In Proceedings of the IoT Applications. 2024 IEEE/ACM Symposium on Edge Computing (SEC), Rome, Italy, 4–7 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MicroK8s. Available online: https://microk8s.io (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Koziolek, H.; Eskandani, N. Lightweight Kubernetes Distributions: A Performance Comparison of MicroK8s, k3s, k0s, and Microshift. In Proceedings of the 2023 ACM/SPEC International Conference on Performance Engineering, Coimbra, Portugal, 15–19 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Enciso, A.; Skarmeta, A. Adapting Containerized Workloads for the Continuum Computing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 104102–104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Xiong, J.; Zhao, Y. Network-aware container scheduling in edge computing. Clust. Comput. 2024, 28, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mdemaya, G.B.J.; Sindjoung, M.L.F.; Ndadji, M.M.Z.; Velempini, M. HERCULE: High-Efficiency Resource Coordination Using Kubernetes and Machine Learning in Edge Computing for Improved QoS and QoE. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 72153–72168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, Y. On the Optimization of Kubernetes toward the Enhancement of Cloud Computing. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbolaji, T.J.; Nzeako, G.; Akokodaripon, D.; Aderoju, A.V. Proactive monitoring and security in cloud infrastructure: Leveraging tools like Prometheus, Grafana, and HashiCorp Vault for Robust DevOps Practices. World J. Adv. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2024, 13, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, M.; Kundan, A.P. Grafana. In Monitoring Cloud-Native Applications; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyidbayli, C. Bit Depth in Energy Consumption: Comparing 32-Bit and 64-Bit Operating System Architectures in Raspberry Pi Systems; Technical University Clausthal: Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, D.; Almeida, F.; Blanco, V.; Toledo, P. KubePipe: A container-based high-level parallelization tool for scalable machine learning pipelines. J. Supercomput. 2025, 81, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukis, G.; Skaperas, S.; Kapetanidou, I.; Mamatas, L.; Tsaoussidis, V. Performance Evaluation of Kubernetes Networking Approaches across Constraint Edge Environments. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Paris, France, 26–29 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ep, C. Development of Kubeflow Components in DevOps Framework for Scalable Machine Learning Systems. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 9, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropp, A.; Torre, R. Docker: Containerize your application. In Computing in Communication Networks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xian, M.; Liu, J. Monitoring System of OpenStack Cloud Platform Based on Prometheus. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Computer Vision, Image and Deep Learning (CVIDL), Chongqing, China, 10–12 July 2020; pp. 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, A.; Bali, M.; Abbas, S.; Singh, M. Unleashing the Potential of Grafana: A Comprehensive Study on Real-Time Monitoring and Visualization. In Proceedings of the 2023 14th International Conference on Computing Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), Delhi, India, 6–8 July 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://github.com/Teodorhack/Microk8s-cluster-from-scratch-/tree/step-2 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Kaggle Database—NSL-KDD. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/code/josiagiven/network-security-attack-classification/notebook (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- Available online: https://github.com/Teodorhack/AIanomaly (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Nguyen, Q.; Phan, L.; Kim, T. Load-Balancing of Kubernetes-Based Edge Computing Infrastructure Using Resource Adaptive Proxy. Sensors 2022, 22, 2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayan, I.; Pinastawa, R.; Pradana, M.; Maulana, N. Web Server Performance Evaluation: Comparing Nginx and Apache Using K6 Testing Methods for Load, Spike, Soak, and Performance. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Informatics, Multimedia, Cyber and Information System (ICIMCIS), Jakarta, Indonesia, 20–21 November 2024; pp. 1002–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhang, W.; Ni, H.; Zha, Q. Benchmarking Apache on Multi-Core Network Processor Platform. In International Conference on Computer Technology and Development, 3rd ed.; ASME Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morić, Z.; Dakić, V.; Čavala, T. Security Hardening and Compliance Assessment of Kubernetes Control Plane and Workloads. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubernetes Documentation. Using RBAC Authorization. Available online: https://kubernetes.io/docs/reference/access-authn-authz/rbac (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Kotenko, M. Navigating the Challenges and Best Practices in Securing Microservices and Kubernetes Environments. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2024, 3826, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Klaermann, S. Evaluating the Suitability of Kubernetes for Edge Computing. Master’s Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Shan, G.; Roh, B.-H. Fair Federated Learning for Multi-Task 6G NWDAF Network Anomaly Detection. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 17359–17370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magid, Y.; Etzion, O.; Shmueli, O. Image Classification on IoT Edge Devices. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.11119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, C.; Mohammadi, M.; Elbtity, M.E.; Zand, R. Efficient Deployment of Transformer Models on Edge TPU. OpenReview 2023. Available online: https://openreview.net/pdf/648914b56e5c4dc27b0a2905008b88750a48bfe1.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).