Abstract

The increasing demand for advanced cosmetic formulations based on natural biopolymers has stimulated the design of multifunctional and sustainable skin care products. Hyaluronic acid (HA) and silk proteins are widely recognized for their hydrating, barrier-supportive, and biocompatible properties. This study aimed to develop a novel topical formulation, integrating low- and medium molecular weight hyaluronic acid (LMW-HA and MMW-HA), encapsulated sodium hyaluronate (NaHA), silk, and hydrolyzed silk as active components, aiming to enhance skin barrier function and biocompatibility. The formulation was subjected to comprehensive physicochemical characterization including evaluation of appearance, odor, color, pH, viscosity, and stability, all assessed over 30 days and microbiological stability testing under controlled storage conditions. Safety evaluation followed a dual-phase strategy: (i) in silico toxicological screening of individual ingredients, including sensitization, and mutagenicity predictions, and (ii) in vivo skin compatibility assessment in 25 human volunteers using a semi-occlusive patch test. The formulation demonstrated good physicochemical stability, as pH remained stable, and viscosity showed no significant changes, confirming structural integrity, indicating preserved structural and microbiological stability throughout the study period. The in silico assessment indicated no mutagenic and/or sensitizing alerts and favorable safety margins for all components, confirming the safety profile of each ingredient, supporting their suitability for dermocosmetic use, while in vivo evaluation revealed no significant adverse effects, with irritation scores indicating no skin reaction (erythema or edema) across the test population. These findings support the potential of this novel biopolymer-based formulation as a safe and well-tolerated dermocosmetic product, aligning with principles of sustainable development and biomimetic design.

1. Introduction

Cosmetics and personal care products depict a vast market category, offering a variety of products that enhance the appearance of consumers’ skin, hair, nails, and/or teeth and the mucous membranes of the oral cavity [1]. As most personal care products are emulsions, they typically contain an ample combination of ingredients, including a solvent/base (such as water), emulsifiers, preservatives, rheology modifiers/thickeners, coloring agents, fragrances, and pH stabilizers, etc. [2,3,4].

Cosmetic ingredients and materials must meet various requirements related to performance, aesthetics, cost, and especially safety, which impacts the adoption of new technologies in cosmetic formulations and applications. This also presents challenges when incorporating polymers into cosmetic products. Polymers are commonly used in a wide category of personal care and cosmetic products, leveraging their diverse properties to provide unique benefits to formulations that vary depending on the types of selected polymers [5].

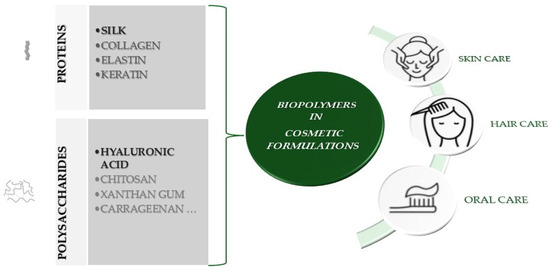

Biopolymers play a crucial role in cosmetic formulations, functioning as rheological modifiers, emulsifiers, conditioners, film-formers, fixing agents, foam stabilizers, moisturizers, and antimicrobials, with the added benefit of metabolic activity on the skin [6,7]. These ingredients are generally categorized into two main types: polysaccharide and protein-based. While the properties of polysaccharides have traditionally been enhanced by synthetic polymers, both polysaccharide and protein-based biopolymers contribute to improving the safety and efficacy of cosmetic ingredients and products [8,9,10,11]. Figure 1 depicts the application and suggestive examples of biopolymers in cosmetic formulations, according to product category:

Figure 1.

Examples of biopolymers in cosmetic formulation and their application according to product category.

Biotechnologically derived ingredients offer enhanced biocompatibility, high purity, and functional versatility [12]. Rising demand for sustainable, high-performance bioactive compounds in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and nutraceuticals has driven the use of advanced biotechnology, including omics technologies, metabolic engineering, and controlled bioprocessing, to produce compounds with improved efficacy, consistency, and environmental compatibility [13,14,15].

Biotechnology is commonly classified by color codes to indicate its main application areas, including cosmetic ingredient development [16,17]. Green biotechnology (plant-based ingredients) leverages plant cell culture and selective fractionation to sustainably produce rare phytochemicals like polyphenols and terpenoids, aligning with clean beauty trends and ecological standards [18,19,20,21,22]. Blue biotechnology (marine-derived ingredients), particularly through microalgae cultivation, provides valuable compounds such as antioxidants, essential fatty acids, and pigments with proven dermocosmetic benefits [23,24,25,26]. White biotechnology (industrial biotechnology/fermentation-based ingredients) involves the development of active cosmetic ingredients using microorganisms through processes such as fermentation and bioconversion or by employing enzymes (biocatalysis). These natural, sustainable methods contribute to the development of eco-friendly raw materials by minimizing the use of harmful solvents. Fermentation and bioconversion relieve sugar transformation, enabling microorganisms to produce primary and secondary metabolites, with valuable cosmetic effects [15,27].

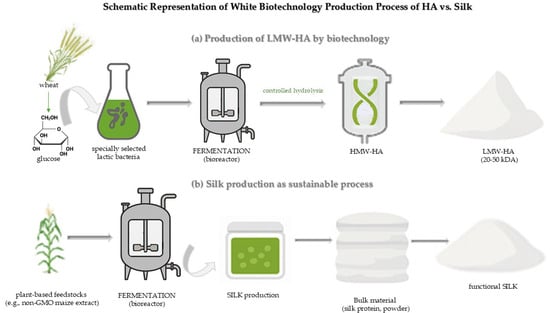

Recent advances in white biotechnology have revolutionized the sustainable production of active cosmetic ingredients, notably hyaluronic acid and silk proteins, enabling their efficient biosynthesis through microbial and enzymatic processes for use in high-performance cosmetic applications [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36] (Figure 2). Currently, microbial fermentation has become a standard method for HA production, considering its reduced risk of cross-infection, straightforward technical implementation (simple process flow), no limitations on raw materials, scalability potential, cost effectiveness, high quality, and environmental sustainability [8,37]. In the context of silk production, white biotechnology has become increasingly important because it enables the generation of bioengineered silk or recombinant silk proteins without relying on traditional sericulture (silkworm farming). For cosmetic applications, white biotechnology supports the production of hydrolyzed silk peptides that enhance skin hydration, functionalized silk proteins with improved stability or skin penetration, and environmentally friendly silk alternatives to conventional animal-derived ingredients [38].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of biotechnological production processes of medium-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid (MMW-HA) versus low-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid (LMW-HA) and functional silk protein. (a) Production of LMW-HA begins with fermentation using specially selected lactic acid bacteria cultured on substrates such as glucose and peptides derived from wheat. The high molecular weight hyaluronic acid produced is subjected to a controlled enzymatic or chemical hydrolysis step, resulting in LMW-HA (20–50 kDa), which demonstrates enhanced bioavailability and dermal penetration; (b) Sustainable silk production involves the use of renewable plant-based feedstocks (e.g., non-GMO maize extract) in microbial fermentation systems. The resultant silk protein is purified into pure powder form and subsequently activated or formulated into functional silk for biomedical or cosmetic applications.

Natural polymer associations may be viable and innovative ingredients for use in cosmetics as actives, possessing multifunctional properties, considering them also as stabilizers and rheological modifiers in cosmetic formulations.

Hyaluronic acid and silk-derived proteins are widely used in anti-ageing skin care due to their humectant, film-forming and barrier-supportive properties, contributing to improved skin hydration, elasticity and texture [39,40,41]. Oil-in-water emulsions are the predominant vehicle for facial creams because they combine good spreadability and cosmetic elegance with the ability to incorporate both hydrophilic and lipophilic ingredients [42,43]. Based on these considerations, we developed an HA- and silk-based anti-ageing cream and evaluated its quality and safety profile through a combination of physicochemical, microbiological, in silico and in vivo assessments.

This study introduces an innovative approach to anti-ageing cosmetic formulation by combining a unique combination of active components, including low- and medium-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, encapsulated NaHA, silk and hydrolyzed silk proteins, a biomimetic peptide complex, and encapsulated botanical extracts (lemon and cucumber fruit extracts). The formulation leverages the multifunctional properties of natural polymers not only as bioactive agents but also as stabilizers and rheological modifiers, demonstrating a multifunctional role. Additionally, the study integrates a comprehensive quality and safety evaluation—covering physicochemical analysis, microbiological stability (including preservative efficacy testing (challenge testing)), in silico toxicological profiling, and in vivo skin compatibility assessment, highlighting a robust and scientifically grounded development process, rarely detailed in cosmetic formulation studies.

2. Results

2.1. Selection of Cosmetic Ingredients and Actives for HA and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Formulation Development

The selection of cosmetic ingredients was based on a multifactorial rationale that includes their clinical relevance, molecular mechanisms, and established safety and efficacy in topical cosmetic applications.

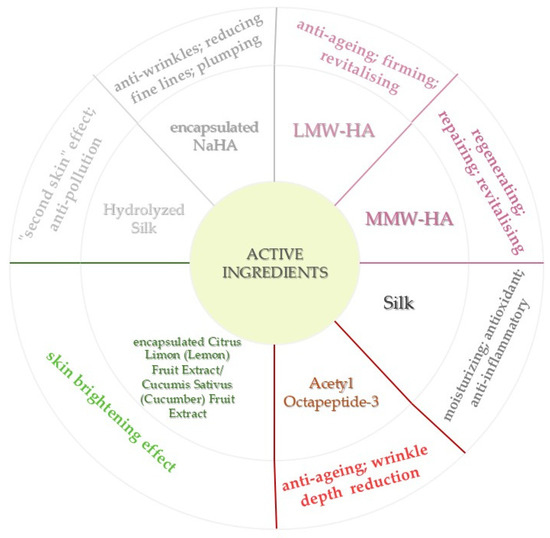

Low- and Medium-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid (LMW-HA, MMW-HA) and encapsulated sodium hyaluronate (NaHA) were selected for their humectant properties and ability to improve skin hydration, reduce fine lines, and promote dermal regeneration.

Acetyl Octapeptide-3 is a biomimetic peptide known for reducing wrinkle depth by modulating facial muscle contractions, targeting dynamic lines.

Silk and hydrolyzed silk proteins provide a “second skin” effect, contributing to skin barrier reinforcement and anti-pollution activity, while also exhibiting moisturizing and anti-inflammatory properties.

Encapsulated botanical extracts from Citrus limon (lemon) and Cucumis sativus (cucumber) fruits are incorporated for their brightening, soothing, and antioxidant activities, enhancing the product’s efficacy against pigmentation irregularities and environmental stress.

This active ingredient association (Figure 3) was carefully incorporated in the cosmetic formulation to provide a synergistic and targeted approach to skin rejuvenation, addressing hydration, firmness, wrinkle depth reduction, elasticity, and brightness, while ensuring skin tolerance and cosmetic elegance.

Figure 3.

Mechanism-Oriented Classification of Active Ingredients in the Anti-Ageing Cream Formulation.

Table 1 presents a detailed overview of the developed HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream, listing each ingredient with its commercial and INCI names, functional role within the formulation, supplier information, and applied concentration range:

Table 1.

Formulation of the developed HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream.

2.2. Physicochemical and Microbiological Assessment of HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream for Quality Control

The combination of stability, physicochemical, and microbiological assessment demonstrated that the developed formulation is a well-formulated product, stable under various conditions, microbiologically safe, and capable of retaining its beneficial properties throughout its shelf life. This robust quality control approach supports compliance with current cosmetic regulations and enhances consumer confidence in the product’s safety and efficacy.

2.2.1. Comprehensive Stability Testing and Physicochemical Profiling of the Formulated Anti-Ageing Cream

To assess the quality of the developed Anti-Ageing Cream, a series of evaluations was conducted to characterize its physicochemical and pharmaceutical-technological properties. Organoleptic evaluation confirmed that the cream’s appearance, color, and odor remained consistent with the initial specifications. Viscosity measurements verified that the formulation maintained an ideal consistency for easy application and uniform texture throughout the study period. The absence of phase separation was also confirmed. pH values remained within the optimal range for skin compatibility. The results indicate that the formulation was stable under the study conditions and exhibited appropriate physicochemical characteristics (Table 2). In addition, a long-term real-time stability study was performed to support the formulation’s shelf life. Samples stored in their primary packaging (glass jar) at the intended storage temperature (20–25 °C) were monitored over a 24-month period, confirming the product’s long-term stability profile.

Table 2.

Anti-Ageing Cream physicochemical properties.

2.2.2. Microbial Safety and Challenge Test Evaluation of the Developed Formulation

The microbiological quality of the developed cosmetic formulation complied with the acceptable limits for total aerobic mesophilic microorganisms, yeasts, and molds, as summarized in Table 3. No pathogenic microorganisms were detected.

Table 3.

Microbiological evaluation of the developed Anti-Ageing Cream.

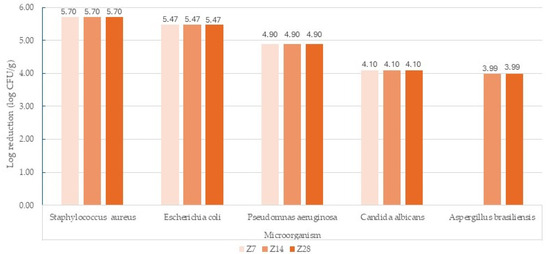

The antimicrobial preservation efficacy of the developed HA- and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream was quantitatively assessed using the standard 28-day Challenge Test in accordance with ISO 11930 (Supplementary Material (Table S1. Raw data corresponding to Challenge test results for the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream)). The evolution of microbial reduction for each inoculated strain is presented in Figure 4, illustrating the logarithmic decrease in viable counts over time (Z7, Z14, Z28).

Figure 4.

Anti-Ageing Cream Challenge test results. Z7—after 7 days, Z14—after 14 days; Z28—after 28 days.

A substantial microbial reduction was observed across all test organisms, exceeding the acceptance limits for Criterion A as defined by the standard. After 7 days, Staphylococcus aureus exhibited a 5.70 log reduction, Escherichia coli 5.47 log, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa 4.90 log. Candida albicans showed a 4.10 log reduction, while Aspergillus brasiliensis reached 3.99 log after 14–28 days. These results confirm a strong and sustained antimicrobial protection throughout the testing period.

Overall, the formulation demonstrated complete compliance with the microbiological safety requirements for cosmetic products, meeting Criterion A of the ISO 11930 standard and confirming the effectiveness of the preservative system composed of Phenoxyethanol and Ethylhexylglycerin.

The combination of stability, physicochemical, and microbiological tests demonstrated that the Anti-Ageing Cream is a well-formulated product, stable under various conditions, microbiologically safe, and capable of retaining its beneficial properties throughout its shelf life. This robust quality control approach supports compliance with current cosmetic regulations and enhances consumer confidence in the product’s safety and efficacy.

2.3. In Silico and Clinical Assessment of the Safety Profile of the Developed Anti-Ageing Cream

2.3.1. Safety Evaluation and Risk Assessment of Cosmetic Ingredients in the Novel Formulation Using In Silico Approaches

The formulation was subjected to in silico safety evaluation using a specific cosmetic risk-assessment platform that integrates ingredient hazard characterization with exposure modelling. The software generated a comprehensive assessment of ingredient safety and enabled the simulation of multiple risk scenarios relevant to the specific formulation. The output included a summary table of results (Table 4), which reflects the product type and the assumed ingredient concentrations used in the assessment. The result reports whether any ingredient is listed in the Annexes of the EU Cosmetics Regulation (Annex III/IV for hair dyes and colorants, Annex V for preservatives, and Annex VI for UV filters), as well as predicted mutagenicity (Ames test), sensitization potential, dermal absorption estimates based on the Kroes approach, the calculated Margin of Safety (MoS), and the Threshold of Toxicological Concern (TTC) values.

Table 4.

Toxicological Hazard and Exposure Profile of Ingredients in the HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream. Product type: Face Cream.

The toxicological assessment of the HA- and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream indicates that many ingredients present no significant mutagenic or sensitization concerns according to the in silico predictions. Most ingredients either showed non-mutagenic profiles with good or experimental reliability or lacked structural alerts indicating genotoxicity. A reduced number of ingredients were identified as potential sensitizers, although reliability levels ranged from low to moderate, and the associated MoS remained well above the accepted threshold of 100, indicating no expected risk under the intended conditions of use.

Ingredients with available dermal absorption predictions showed absorption values between 10 and 80%, with more hydrophilic components (e.g., glycerine, glycols) generally displaying higher predicted uptake. Despite these absorption estimates, the MoS values for all assessed compounds were several orders of magnitude above the minimum requirement, and others (e.g., Hydrolysed Hyaluronic Acid) reached very high values, reflecting extremely low systemic exposure relative to the established NOAELs.

The TTC values remained low across the ingredients, consistent with the expected dermal exposure profile of a leave-on facial cosmetic.

No ingredient in the formulation was indicated as belonging to restricted categories in the EU Cosmetics Regulation Annexes III, IV, V, or VI, except for Triethanolamine (Annex III), Phenoxyethanol (Annex V), Potassium Sorbate (Annex V), and Titanium Dioxide (Annex VI). All were used correctly within regulatory concentration limits, and the associated MoS values confirmed their safe inclusion in the formulation.

Hydrolyzed Silk (9.8%), Hydrolyzed Hyaluronic Acid (0.7%), and emollients and thickeners formed the functional basis of the cream. Even at higher usage levels, none of these ingredients exhibited toxicological alerts, and all demonstrated very high MoS values, indicating a wide margin between estimated exposure and potential adverse effect thresholds.

Overall, the compiled toxicological and exposure data indicate that the formulation components—individually and collectively—exhibit favorable safety profiles under the intended conditions of cosmetic use. The combination of non-mutagenicity predictions, low sensitization concern, high MoS values, and supportive TTC estimates supports a positive safety assessment for the HA- and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream.

2.3.2. HA and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream Skin Tolerance—Dermatological Semi-Open Test

Dermatological evaluation demonstrated very good skin tolerance of the developed cosmetic formulation. Throughout the semi-open patch test, conducted under dermatological supervision, none of the participants exhibited any signs of irritation or allergic reaction at any assessment time point.

The irritation potential was quantified using the average irritation index (Xav), calculated as the sum of erythema and edema scores according to a four-level classification system (Xav < 0.50: not irritating; 0.50 ≤ Xav < 2.00: slightly irritating; 2.00 ≤ Xav < 5.00: moderately irritating; Xav ≥ 5.00: highly irritating). All subjects recorded a score of 0 for both erythema and edema at 48 h (T1) and 72 h (T2). Because no reactions were observed at T1 or T2, the 96 h assessment (T3) was not required, in line with test protocol criteria.

Based on these results, the developed anti-ageing cream demonstrated excellent dermatological compatibility and was classified as “not irritating” (Xav < 0.50), confirming its suitability for topical application (Table 5):

Table 5.

Dermatological responses in the Semi-Open Test were expressed as erythema, edema, and average irritation index (Xav).

Across all 25 subjects included in the skin tolerance evaluation, the irritation index remained 0.00 ± 0.00 at 48, respectively, 72 h, indicating a complete absence of erythema or edema in the study population.

3. Discussion

Each cosmetic product incorporates a complex combination of ingredients. Evaluating its safety typically involves analyzing the toxicological profiles of individual ingredients in relation to the expected product exposure. The safety assessment of the final formulation considers various factors, including the physicochemical properties and chemical structure, and toxicological data of the ingredients, but also in vitro and clinical studies on the finished formulation, and potential product exposure. Additionally, confirmatory testing on human volunteer subjects may be conducted to assess product compatibility and acceptability [44].

These findings underscore the potential of the developed biopolymer-based cosmetic formulation as a safe and efficacious dermocosmetic system. By integrating components such as hyaluronic acid and silk derivatives, the formulation closely mimics the structural and functional properties of the skin’s extracellular matrix. This biomimetic approach, combined with the use of sustainably sourced materials and environmentally conscious processing, highlights the formulation’s relevance to modern trends in green chemistry and bioinspired product design.

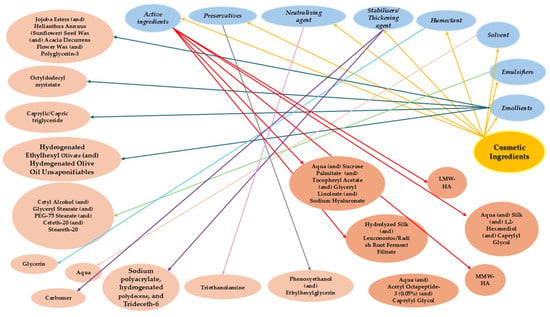

Figure 5 illustrates the ingredients and active compounds incorporated into the developed Anti-Ageing Cream. Each segment represents a specific ingredient or group of ingredients along with its corresponding cosmetic function.

Figure 5.

Circular dendrogram of cosmetic ingredients categorized by function in the HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream. •—gold: starting node for cosmetic ingredients; •—light blue: functional categories; •—light coral: specific ingredients according to INCI.

The circular dendrogram provides a structured visualization of the cosmetic formulation by categorizing each ingredient according to its functional role within the HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream. Starting from the central node, “Cosmetic Ingredients”, the dendrogram branches out into primary functional categories such as emollients, emulsifiers, solvent(s), humectants, stabilizers/thickening agents, neutralizing agents, preservatives, and active ingredients. Each category then links to specific compounds employed in the formulation.

This hierarchical structure illustrates the complex approach required in cosmetic formulation development. For instance, emollients contribute to skin softness and barrier function [45], while emulsifiers ensure the stability of oil-in-water emulsions critical for product texture [46]. The solvent and humectant components, such as water and glycerin, enhance hydration [47]. Particularly important are the active ingredients, which include multiple forms of hyaluronic acid, silk derivatives, peptides, and microencapsulated botanical extracts, reflecting the product’s targeted anti-ageing and skin-rejuvenating claims. This active ingredient association was carefully incorporated in the cosmetic formulation to provide a synergistic and targeted approach to skin rejuvenation, addressing hydration, firmness, wrinkle depth reduction, elasticity, and brightness, while ensuring skin tolerance and cosmetic elegance.

The pH of the formulation (5.3 ± 0.2) remained within the range generally recommended for facial leave-on products (approximately 4.5–6.0), which is compatible with the physiological skin surface pH and supports skin barrier function. Viscosity values in the 4.5–7.0 Pa·s range at 20 °C correspond to a semi-solid texture that spreads easily while maintaining structural integrity in the primary packaging, consistent with the sensorial profile of commercial oil-in-water facial creams [46,48,49]. The absence of phase separation or syneresis further indicates adequate emulsion stability under the tested conditions. The field of cosmetic safety assessment has seen advancements in recent years, particularly in the use of in silico approaches, in addition to the traditional safety evaluation methods. However, it is important to notice that in silico methods are most effective when combined with traditional safety testing and regulatory oversight to ensure the highest level of consumer protection [48,50,51,52].

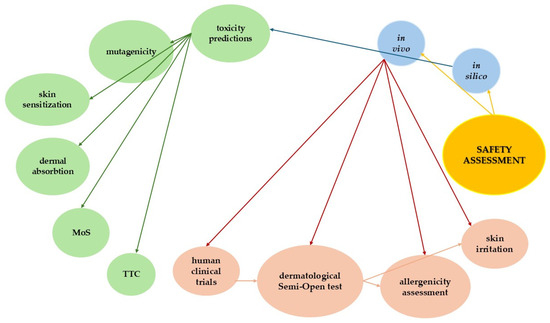

Figure 6 provides a comprehensive visual representation of the safety assessment flow for the HA- and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream, structured across both in silico and in vivo evaluation pathways. The diagram originates from the overarching concept of safety assessment, branching into two principal domains: in silico and in vivo methodologies.

Figure 6.

Circular dendrogram of in silico and in vivo assessment pathways for the novel HA- and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream. •—gold: starting node (safety assessment); •—light blue: main assessment categories (in silico, in vivo); •—light green: in silico parameters; •—light coral: in vivo parameters.

The in silico evaluation is structured around toxicity prediction, which further informs specific predictive endpoints including mutagenicity, skin sensitization, dermal absorption, MoS, and TTC. This sequence reflects the tiered approach of computational toxicology, where generalized toxicity predictions are refined through specific hazard evaluations.

In parallel, the in vivo assessment path begins with human clinical trials, advancing to the dermatological Semi-Open test, a critical method for evaluating skin compatibility in human subjects [53]. This test directly informs the assessment of skin irritation and allergenicity, ensuring empirical validation of safety parameters initially predicted via computational models.

Directional arrows within the dendrogram illustrate the hierarchical and functional relationships between assessments, emphasizing how toxicity prediction informs subsequent computational evaluations, while in vivo trials progress through increasingly specific dermatological assessments. Overall, this structured visualization underlines the complementary roles of in silico predictions and in vivo validation, aligning with current regulatory and scientific frameworks for the comprehensive safety evaluation of cosmetic formulations.

According to our study, in silico toxicological assessment demonstrated that the HA- and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream is safe for its intended cosmetic use. All evaluated ingredients showed favorable hazard profiles, with no indications of mutagenic potential and only limited sensitization alerts of low to moderate reliability. Importantly, all calculated Margins of Safety substantially exceeded the regulatory threshold of 100, indicating a wide safety margin even under conservative exposure assumptions, and TTC values further supported the safety of ingredients with limited toxicological datasets. Taken together, the hazard characterization, exposure modeling, and regulatory compliance evaluation confirm that the formulation presents no expected risk to consumers when used as intended. Furthermore, dermatological testing using a semi-open patch test confirmed excellent skin compatibility of the novel developed cosmetic formulation.

Although New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) are now widely applied in the risk assessment of cosmetic ingredients and formulations, there remains a clear need for integrated evaluation strategies. This is because alternative methods are not always fully applicable to complex, multicomponent ingredients or finished cosmetic products, representing a notable limitation when compared with traditional in vivo testing.

Findings from this study indicate that the developed biopolymer-based formulation, combining hyaluronic acid with silk and hydrolyzed silk, exhibits favorable safety and performance profiles for (dermo)cosmetic use. Designed to emulate the skin’s natural extracellular matrix, the formulation reflects a biomimetic strategy aligned with sustainable material development. These attributes position it as a promising candidate for advanced, biocompatible cosmetic applications. Overall, the results support its suitability for advanced cosmetic applications with enhanced functional performance and skin compatibility.

Further in vivo efficacy assessment, e.g., skin microrelief evaluation, and/or periorbital wrinkles length and depth reduction, could confirm the claimed effect of the anti-ageing formulation, for a comprehensive characterization and evaluation according to the current legal framework.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection of Cosmetic Ingredients and Actives for Anti-Aging Formulation Development

The selection of ingredients for the anti-ageing cream formulated with hyaluronic acid (LMW- and MMW-HA, together with NaHA microcapsules) and silk proteins (broadly identified as an HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream) was based on the classification of raw materials according to their respective Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS). Safety-related information for each cosmetic ingredient, including permitted concentration limits, documented safe use levels, and ingredient-specific properties, was retrieved from the Cosmetic Ingredient Database (CosIng), COSMILE Europe, and the Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR). This classification ensured the safety and functional suitability of each component in the cosmetic formulation. Ingredients were selected based on their INCI (International Nomenclature of Cosmetic Ingredients) names and corresponding commercial designations, as outlined in Table 6, according to their cosmetic functions.

Table 6.

INCI Denomination, Commercial Designations, and Cosmetic Functions of the Selected Ingredients.

The cosmetic formulation incorporates a unique and synergistic combination of active ingredients with scientifically demonstrated efficacy, targeting improvements in skin hydration, elasticity, texture, and radiance. In particular, hyaluronic acid and silk-derived proteins have been selected due to their complementary biological properties and established use in anti-ageing skincare. Table 7 summarizes the key physicochemical characteristics and cosmetic functions of the HA and silk components incorporated in the developed formulation:

Table 7.

Comparative Characteristics of Polysaccharide (Hyaluronic Acid) and Protein (Silk) Biopolymers in the Cosmetic Formulation.

4.2. Formulation Design, Composition and Manufacturing Process of the HA and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream

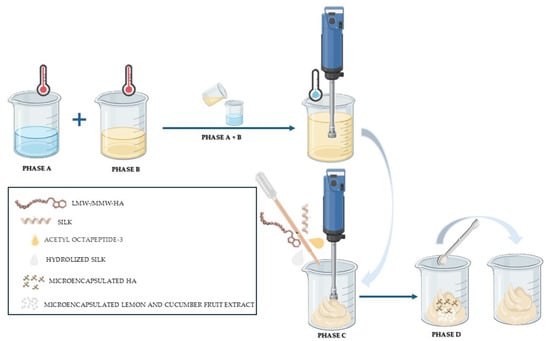

The HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream was formulated using a phase emulsification technique, whereby the oil and aqueous phases were separately prepared under controlled temperature conditions, subsequently combined under continuous stirring, and homogenized to achieve a stable emulsion. Active ingredients were then incorporated during the cooling phase to preserve their stability and bioactivity (Figure 7). The manufacturing procedure was performed under controlled laboratory conditions as follows:

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the manufacturing procedure for the HA and Silk-based Anti-ageing Cream.

- (i)

- phase preparation (Phase A and Phase B):

The oil phase and aqueous phase were prepared separately by heating each component to approximately 70–75 °C using a water bath. The oil phase typically included emulsifiers and lipid-soluble ingredients, while the aqueous phase contained water (INCI Aqua, PURELAB®® Option Q7 (Type I), ELGA LabWater, HighWycombe, UK), humectants, hydrating agents, and preservatives and water-soluble components.

- (ii)

- Emulsification (Phase A + Phase B):

The oil phase was slowly added to the aqueous phase under continuous mechanical stirring using a high-shear homogenizer (T 50 digital ULTRA-TURRAX with a S 50 N-G 45 G dispersing tool (IKA, Staufen, Germany) (2400 rpm for 20 min)), to ensure uniform mixing and emulsion formation.

- (iii)

- cooling and active ingredients addition (Phase C):

After forming a stable emulsion, the cosmetic cream was gradually cooled to room temperature under constant stirring. Once the temperature dropped below 40 °C, heat-sensitive active ingredients such as LMW-HA (20–50 kDa), MMW-HA (100–300 kDa) (previously dissolved in 10 mL of ultrapure water for complete dissolution), Silk and hydrolyzed Silk, Acetyl Octapeptide-3 complex, and the perfume were added and mixed thoroughly.

- (iv)

- final homogenization (Phase D):

Encapsulated NaHA, together with lemon and cucumber microcapsules, was added to the emulsion. The formulation underwent a final homogenization step using a T 50 digital ULTRA-TURRAX (equipped with an R 50 stirring shaft mixing head with an R 1405 Propeller (IKA, Staufen, Germany) (600 rpm for 5 min)). These mild homogenization conditions were chosen to prevent microcapsule breakage while ensuring uniform dispersion.

The cream was transferred into sterile containers and stored at ambient conditions until further testing. This standardized process ensured consistency in texture, viscosity, and stability, aligning with the quality control parameters required for cosmetic product development.

4.3. Quality Assessment of the HA and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream: Physicochemical and Microbiological Perspective

In compliance with Regulation 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on Cosmetic Products, a thorough quality control protocol was implemented to assess the stability, physicochemical properties, and microbiological safety of the formulated HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream. These evaluations are critical to ensuring product safety, consistency, and effectiveness during production, distribution, and consumer use [48,49,52,93,94,95,96].

4.3.1. Evaluation of the Stability Profile of the Cosmetic Formulation

The stability of the developed cream was tested to evaluate how storage conditions may impact the product’s texture, appearance, and overall performance over time. The stability tests were conducted under accelerated conditions to simulate potential changes during extended shelf life. The samples were stored for 30 days at different controlled temperatures: 4 °C (refrigerated conditions) (LKUv 1610 MediLine, Liebherr, Germany); 20 °C (room temperature) and 40 °C (elevated temperature) (Natural convection drying oven SLN-32 (STD), Pol-Eko, Wodzisław Śląski, Poland) [48,49,95]. The detailed study protocol considering the stability testing cycle is presented in Supplementary Material (Table S2. Stability test cycle for the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream). A 24-month real-time stability study was also conducted to evaluate the long-term stability of the developed formulation.

4.3.2. Assessment of Key Physicochemical Parameters of the Cosmetic Formulation

The following physicochemical parameters were evaluated to verify that the developed formulation meets industry standards for texture, viscosity, pH, and overall formulation quality: organoleptic properties (appearance, colour, odour) (ISO 6658:2005 p. 5.4.2 [97]); viscosity determinations (Brookfield DV-III Ultra, spindle Sc4-18/RPM: 250 (o/min/shear rate 330 (1/s)); density (20 °C) (PB-155 ed. I of 2 May 2012), and pH testing (PB-234 ed. I of 03.10.2013r.). Viscosity, density and pH values represent the mean ± standard deviation of n = 3 determinations performed on one batch measured in triplicate.

4.3.3. Evaluation of Microbiological Quality of Cosmetic Formulation and Preservative Efficacy

Ensuring microbiological safety is crucial for cosmetics. Considering this aspect, the following microbiological assessments were conducted:

- (i)

- Microbiological analysis: this test was carried out according to ISO standards to determine the total aerobic mesophilic bacteria count (SR EN ISO 21149:2017 [98]), yeast and mould counts (SR EN ISO 16212:2017 [99]), and the presence of key pathogens, following microorganisms being specifically monitored: Staphylococcus aureus detection (SR EN ISO 22718:2016 [100]), Candida albicans detection (SR EN ISO 18416:2016 [101]), Escherichia coli detection (SR EN ISO 21150:2016 [102]), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa detection (SR EN ISO 22717:2016 [103]).

- (ii)

- Preservative Efficacy Test (Challenge Test): This critical test evaluated the ability of the formulation’s preservative system (Phenoxyethanol and Ethylhexylglycerin) to inhibit microbial growth during product usage and storage. Conducted per PN EN ISO 11930:2012 standards [104], this 28-day test involved intentionally contaminating the developed cream with a specific concentration of microorganisms and then monitoring microbial reduction over time [48,52].

4.4. Integrated Safety Evaluation of the Anti-Ageing Cream via In Silico and Clinical Approaches

4.4.1. Predictive In Silico Evaluation of Cosmetic Ingredient Safety and Risk Assessment in the Developed Anti-Ageing Cream

The in silico safety assessment of the HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream was conducted using SpheraCosmolife (version 0.24), a module of the LIFE VERMEER platform (Milan, Italy) developed for integrated hazard and exposure evaluation of cosmetic ingredients and formulations. The software incorporates QSAR models from the VEGA platform to characterize ingredient-related risks and provides ingredient-specific reports summarizing predicted hazards, exposure scenarios, and overall safety considerations [105]. This system enabled comprehensive characterization of ingredient safety profiles and supported the investigation of multiple potential risk scenarios, ensuring a rigorous and science-based cosmetic risk assessment.

Each ingredient in the formulation was evaluated for potential hazards based on established safety profiles, including sensitization, dermal absorption, and potential long-term health effects, such as mutagenicity. The hazard assessment was performed in accordance with international regulatory frameworks, including the EU Cosmetics Regulation, to ensure compliance with current safety standards. The margin of safety (MoS) was estimated by integrating the systemic exposure dose with hazard characterization parameters, using validated exposure and hazard prediction models. A MoS ≥ 100 was considered acceptable, reflecting standard safety factors for inter-species extrapolation and human variability, in accordance with SCCS guidance for cosmetic ingredient safety assessment [106]. In addition, the threshold of toxicological concern (TTC) approach was applied when appropriate to support the overall toxicological evaluation of the cosmetic formulation. This methodology facilitated a predictive, science-based assessment of the formulation’s safety, ensuring regulatory compliance and guiding risk management decisions [107].

4.4.2. Dermatological Safety Evaluation of the Developed HA and Silk-Based Anti-Ageing Cream

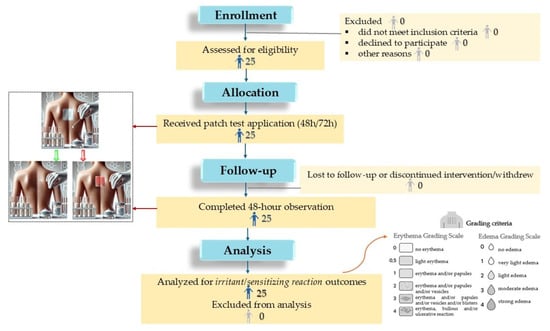

This study was conducted to evaluate the sensitizing and irritant potential, as well as the skin tolerance, of the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream through a semi-open patch test. The assessment focused on the appearance of erythema and edema at defined intervals following product application [108].

A total of 25 healthy Caucasian volunteer subjects were enrolled, all with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes I to IV. Subjects were selected based on general inclusion criteria requiring intact, non-irritated skin at the test site, with no ongoing dermatological conditions or pharmacological treatments that could interfere with the evaluation. Exclusion criteria included any known history of skin disorders, hypersensitivity, or adverse reactions to cosmetic ingredients. Subject’s characteristics and eligibility criteria of participants in the semi-open test are presented in Table 8:

Table 8.

Demographic Data and Eligibility Criteria of Participants in the Semi-Open Test of the Test Formulation.

The test product was applied using a semi-open patch (12 mm diameter Finn Chamber, SmartPractice, Phoenix, AZ, USA), involving the topical application of a measured amount of formulation to the inner forearm under semi-occlusive conditions for 48, 72, and 96 h. This anatomical site was selected for its sensitivity and suitability for early detection of irritant reactions. After removal of the patches, trained dermatologists performed clinical evaluations of the skin to assess for erythema, edema, or other signs of irritation or sensitization. For the semi-open tolerance test, descriptive statistics (mean ± standard deviation) were calculated for the irritation index at each time point.

The study design and flow of participants are presented in the CONSORT flow diagram below (Figure 8):

Figure 8.

CONSORT Flow Diagram of Participant Enrollment and Assessment in the Semi-Open Clinical Evaluation of Skin Tolerance.

The results were quantified using the Average Irritation Index (X̄av), calculated based on individual irritation scores over the observation period. Based on the X̄av, the test formulation was classified according to standard irritation categories: not irritating (X̄av = 0); slightly irritating (0 < X̄av ≤ 0.5); moderately irritating (0.5 < X̄av ≤ 1.5); highly irritating (X̄av > 1.5).

This study followed a non-randomized, single-arm design and therefore, no control or comparison groups were included. All participants provided informed consent (ICF), and the study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards for non-invasive cosmetic testing. An independent laboratory (J.S. Hamilton Poland Sp. z o.o., Gdynia, Poland) conducted the study in accordance with current regulatory requirements, including Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 on Cosmetic Products and the Cosmetics Europe (formerly COLIPA) Product Test Guidelines for the Assessment of Human Skin Compatibility.

5. Conclusions

Polymers play essential roles in cosmetic formulations by contributing to stability, texture, and overall performance. Concurrently, biotechnology is driving innovation by enabling the development of advanced ingredients that improve product safety and efficacy. Together, these advances support the creation of next-generation cosmetics that meet regulatory requirements and consumer expectations. Ensuring cosmetic safety—including ingredient testing and continuous improvement of assessment methods—remains a central focus in current research and development.

This novel formulation developed in this study, based on natural biopolymers, demonstrated suitable quality attributes, favorable skin tolerance and promising application potential in cosmetic science. The integration of hyaluronic acid and silk-derived ingredients is consistent with biomimetic design principles and current trends in sustainable cosmetic product development, indicating its relevance for future dermocosmetic applications.

In conclusion, the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream demonstrates a favorable safety profile, supported by ingredient-level analysis and in vivo skin compatibility assessment. While comprehensive risk assessment remains essential due to the complexity of multi-component formulations, advances in toxicological methods and regulatory alignment will further reinforce safety assurance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412973/s1, Table S1: Raw data corresponding to Challenge test results for the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream and Table S2: Stability test cycle for the developed HA and Silk-based Anti-Ageing Cream.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; methodology, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; software, L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; resources, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; writing—review and editing, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; visualization, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J.; supervision, A.M.J.; project administration, D.L.M., L.-L.R. and A.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by SC Aviva Cosmetics SRL, which provided the cosmetic ingredients used in the formulation and covered all expenses, including those related to the clinical trial.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board of J.S. Hamilton Poland Sp. z o.o. (protocol No. 267095/21/JSHR/21.05.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge SC Aviva Cosmetics SRL for providing ingredients and trial support.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Anca Maria Juncan is the owner of SC Aviva Cosmetics SRL, which sponsored the study. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on Cosmetic Products. 2009. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R0655 (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Loh, X.J.; Zheng, Y.J. Natural Rheological Modifiers for Personal Care. In Polymers for Personal Care Products and Cosmetics; Loh, X.J., Ed.; Royal Society Of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 60–89. [Google Scholar]

- Juncan, A.M.; Fetea, F.; Socaciu, C. Application of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy for the Characterization of Sustainable Cosmetics and Ingredients with Antioxidant Potential. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncan, A.M.; Hodisan, T. Determination of Synthetic and Natural Antioxidants in Cosmetic Preparations by Solid-Phase Extraction and Subsequent Gas and High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Analysis. Rev. Chim. 2011, 62, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, A.; Ferritto, M.S. Polymers for Personal Care and Cosmetics:Overview. In Polymers for Personal Care and Cosmetics; Patil, A., Ferritto, M.S., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 1148, pp. 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, T.F.R.; Morsink, M.; Batain, F.; Chaud, M.V.; Almeida, T.; Fernandes, D.A.; da Silva, C.F.; Souto, E.B.; Severino, P. Applications of Natural, Semi-Synthetic, and Synthetic Polymers in Cosmetic Formulations. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhi, M.; Prabhakaran, M.P.; Ramakrishna, S. Edible Polymers: An Insight into Its Application in Food, Biomedicine and Cosmetics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 103, 248–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Muñoz, N.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; Piñón-Segundo, E.; Zambrano-Zaragoza, M.L.; Quintanar-Guerrero, D.; Del Prado Audelo, M.L.; Urbán-Morlán, Z. Trends in Biopolymer Science Applied to Cosmetics. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2023, 45, 699–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, P.; Morganti, G.; Coltelli, M.B. Natural Polymers and Cosmeceuticals for a Healthy and Circular Life: The Examples of Chitin, Chitosan, and Lignin. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuro, G.; Costantini, A.; Baratto, G.; Francescato, S.; Busata, L.; Semenzato, A. Characterization of Polysaccharidic Associations for Cosmetic Use: Rheology and Texture Analysis. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawade, R.P.; Chinke, S.L.; Alegaonkar, P.S. Polymers in Cosmetics. In Polymer Science and Innovative Applications: Materials, Techniques, and Future Developments; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 545–565. ISBN 9780128168080. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco, A.; Martins, M.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Ribeiro, A. Biotechnology of Functional Proteins and Peptides for Hair Cosmetic Formulations. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappelli, C.; Barbulova, A.; Apone, F.; Colucci, G. Effective Active Ingredients Obtained through Biotechnology. Cosmetics 2016, 3, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Jerold, F. Biocosmetics: Technological Advances and Future Outlook. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 25148–25169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.; Silva, A.C.; Marques, A.C.; Lobo, J.S.; Amaral, M.H. Biotechnology Applied to Cosmetics and Aesthetic Medicines. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, M.C.S.; Lupki, F.B.; Campolina, G.A.; Nelson, D.L.; Molina, G. The Colors of Biotechnology: General Overview and Developments of White, Green and Blue Areas 1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2018, 365, fny239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafarski, P. Rainbow Code of Biotechnology. CHEMIK 2012, 8, 811–816. [Google Scholar]

- Sasounian, R.; Martinez, R.M.; Lopes, A.M.; Giarolla, J.; Rosado, C.; Magalhães, W.V.; Velasco, M.V.R.; Baby, A.R. Innovative Approaches to an Eco-Friendly Cosmetic Industry: A Review of Sustainable Ingredients. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C. Green Cosmetic Ingredients and Processes. In Analysis of Cosmetic Products, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 303–330. ISBN 9780444635167. [Google Scholar]

- Nhani, G.B.B.; Di Filippo, L.D.; de Paula, G.A.; Mantovanelli, V.R.; da Fonseca, P.P.; Tashiro, F.M.; Monteiro, D.C.; Fonseca-Santos, B.; Duarte, J.L.; Chorilli, M. High-Tech Sustainable Beauty: Exploring Nanotechnology for the Development of Cosmetics Using Plant and Animal By-Products. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aneklaphakij, C.; Chamnanpuen, P.; Bunsupa, S.; Satitpatipan, V. Recent Green Technologies in Natural Stilbenoids Production and Extraction: The Next Chapter in the Cosmetic Industry. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzroud, S.; El Maaiden, E.; Sobeh, M.; Merghoub, N.; Boukcim, H.; Kouisni, L.; El Kharrassi, Y. Biotechnological Approaches to Producing Natural Antioxidants: Anti-Ageing and Skin Longevity Prospects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, E.A.; Agusman; Pangestuti, R.; Shin, K.H.; Kim, S.K. Potential Cosmetic Active Ingredients Derived from Marine By-Products. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.P.; Custódio, L.; Reis, C.P. Exploring the Potential of Using Marine-Derived Ingredients: From the Extraction to Cutting-Edge Cosmetics. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, K.; Pedroza-Islas, R.; Pedraza-Segura, L. Blue Biotechnology: Marine Bacteria Bioproducts. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anestopoulos, I.; Kiousi, D.E.; Klavaris, A.; Maijo, M.; Serpico, A.; Suarez, A.; Sanchez, G.; Salek, K.; Chasapi, S.A.; Zompra, A.A.; et al. Marine--derived Surface Active Agents: Health—Promoting Properties and Blue Biotechnology--based Applications. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajna, K.V.; Gottumukkala, L.D.; Sukumaran, R.K.; Pandey, A. White Biotechnology in Cosmetics. In Industrial Biorefineries and White Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 607–652. ISBN 9780444634535. [Google Scholar]

- Karami, M.; Shahraky, M.K.; Ranjbar, M.; Tabandeh, F.; Morshedi, D.; Aminzade, S. Preparation, Purification, and Characterization of Low-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid. Biotechnol. Lett. 2021, 43, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ucm, R.; Aem, M.; Lhb, Z.; Kumar, V.; Taherzadeh, M.J.; Garlapati, V.K.; Chandel, A.K. Comprehensive Review on Biotechnological Production of Hyaluronic Acid: Status, Innovation, Market and Applications. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 9645–9661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Morales, G.; Poggi-Varaldo, H.M.; Ponce-Noyola, T.; Pérez-Valdespino, A.; Curiel-Quesada, E.; Galíndez-Mayer, J.; Ruiz-Ordaz, N.; Sotelo-Navarro, P.X. A Review of the Production of Hyaluronic Acid in the Context of Its Integration into GBAER-Type Biorefineries. Fermentation 2024, 10, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Chen, J. Microbial Production of Hyaluronic Acid: Current State, Challenges, and Perspectives. Microb. Cell Factories 2011, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PrimalHyalTM 50_Givaudan. Available online: https://www.givaudan.com/fragrance-beauty/active-beauty/products/primalhyal-50 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Huang, L.; Shi, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Q. Advances in Preparation and Properties of Regenerated Silk Fibroin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitar, L.; Isella, B.; Bertella, F.; Bettker Vasconcelos, C.; Harings, J.; Kopp, A.; van der Meer, Y.; Vaughan, T.J.; Bortesi, L. Sustainable Bombyx Mori’s Silk Fibroin for Biomedical Applications as a Molecular Biotechnology Challenge: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silkgel_Givaudan. Available online: https://www.givaudan.com/fragrance-beauty/active-beauty/products/silkgel (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Kannan, P.R.; Li, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhao, R.; Kong, X. Silk-Based Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2025, 338, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rivero, C.; López-Gómez, J.P. Unlocking the Potential of Fermentation in Cosmetics: A Review. Fermentation 2023, 9, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Hu, X.; Liang, R. Recombinant Fibrous Protein Biomaterials Meet Skin Tissue Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1411550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Roth, M.; Karakiulakis, G. Hyaluronic Acid: A Key Molecule in Skin Aging. Dermatoendocrinol 2012, 4, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvez-Martin, P.; Soto-Fernandez, C.; Romero-Rueda, J.; Cabañas, J.; Torrent, A.; Castells, G.; Martinez-Puig, D. A Novel Hyaluronic Acid Matrix Ingredient with Regenerative, Anti-Aging and Antioxidant Capacity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadir, J.; Islam, T. Potential of Silk Proteins in Cosmetics. J. Sci. Agric. 2024, 8, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, M. Introduction to Cosmetic Emulsions and Emulsification; Published on behalf of the International Federation of Societies of Cosmetic Chemists by Micelle; Micelle Press: Weymouth, UK, 2010; Vol. Monograph No. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Dănilă, E.; Moldovan, Z.; Kaya, M.G.A.; Ghica, M.V. Formulation and Characterization of Some Oil in Water Cosmetic Emulsions Based on Collagen Hydrolysate and Vegetable Oils Mixtures. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 1493–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretz, L.J.; Bailey, J.E. CTFA Preservative Challenge and Stability Testing Survey—Cosmetics & Toiletries; The Cosmetic Toiletry and Fragrance Association (CTFA): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berkey, C.; Kanno, D.; Mehling, A.; Koch, J.P.; Eisfeld, W.; Dierker, M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dauskardt, R.H. Emollient Structure and Chemical Functionality Effects on the Biomechanical Function of Human Stratum Corneum. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2020, 42, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, J.; He, C.; He, L.; Li, X.; Sui, H. The Formation, Stabilization and Separation of Oil–Water Emulsions: A Review. Processes 2022, 10, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madnani, N.; Deo, J.; Dalal, K.; Benjamin, B.; Murthy, V.V.; Hegde, R.; Shetty, T. Revitalizing the Skin: Exploring the Role of Barrier Repair Moisturizers. J. Cosmet. Dermatol 2024, 23, 1533–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncan, A.M.; Morgovan, C.; Rus, L.L.; Loghin, F. Development and Evaluation of a Novel Anti-Ageing Cream Based on Hyaluronic Acid and Other Innovative Cosmetic Actives. Polymers 2023, 15, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncan, A.M.; Rus, L.L. Influence of Packaging and Stability Test Assessment of an Anti-Aging Cosmetic Cream. Mater. Plast. 2018, 55, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnuqaydan, A.M. The Dark Side of Beauty: An in-Depth Analysis of the Health Hazards and Toxicological Impact of Synthetic Cosmetics and Personal Care Products. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1439027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthe, M.; Bavoux, C.; Finot, F.; Mouche, I.; Cuceu-Petrenci, C.; Forreryd, A.; Hansson, A.C.; Johansson, H.; Lemkine, G.F.; Thénot, J.P.; et al. Safety Testing of Cosmetic Products: Overview of Established Methods and New Approach Methodologies (Nams). Cosmetics 2021, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncan, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Morgovan, C.; Loghin, F. Evaluation of the Safety of Cosmetic Ingredients and Their Skin Compatibility through In Silico and In Vivo Assessments of a Newly Developed Eye Serum. Toxics 2024, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, A.P.; Basketter, D.A.; Baverel, M.; Diembeck, W.; Matthies, W.; Mougin, D.; Paye, M.; Rothlisberger, R.; Dupuis, J. Test Guidelines for Assessment of Skin Compatibility of Cosmetic Finished Products in Man. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1996, 34, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jojoba Esters (and) Helianthus Annuus (Sunflower) Seed Wax (and) Acacia Decurrens Flower Wax (and) Polyglycerin-3 ACTICIRE MB. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1520629.pdf?bs=3983&b=719008&st=1&sl=149104681&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbQUNUSUNJUkVd&k=ACTICIRE&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Octyldodecyl Myristate MOD MB. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1395526.pdf?bs=3983&b=588277&st=1&sl=149105263&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbTU9EIE1CXQ%3d%3d&k=MOD|MB&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Huber, P.; Reinau, D.; Brodard, Z.; Meier, C.R.; Surber, C. How to Choose an Emollient? Pharmaceutical and Sensory Attributes for Product Selection. Skin. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2025, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprylic/Capric Triglyceride LABRAFAC CC. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1395523.pdf?bs=3983&b=588276&st=1&sl=149105203&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbTGFicmFmYWMgQ0Nd&k=Labrafac|CC&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Fiume, M.M.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Amended Safety Assessment of Triglycerides as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 22–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrogenated Ethylhexyl Olivate (and) Hydrogenated Olive Oil Unsaponifiables SOFTOLIVE. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1597710.pdf?bs=830&b=724179&st=1&sl=149105673&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbU29mdG9saXZlXQ%3d%3d&k=Softolive&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Burnett, C.L.; Fiume, M.M.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; et al. Safety Assessment of Plant-Derived Fatty Acid Oils. Int. J. Toxicol. 2017, 36, 51S–129S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetyl Alcohol (and) Glyceryl Stearate (and) PEG-75 Stearate (and) Ceteth-20 (and) Steareth-20 EMULIUM DELTA MB. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1520632.pdf?bs=3983&b=719010&st=1&sl=149105458&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbRW11bGl1bcKuIERlbHRhIE1CXQ%3d%3d&k=Emulium%c2%ae|Delta|MB&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Chen, H.J.; Lee, P.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Huang, S.L.; Huang, B.W.; Dai, F.J.; Chau, C.F.; Chen, C.S.; Lin, Y.S. Moisture Retention of Glycerin Solutions with Various Concentrations: A Comparative Study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.C.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety Assessment of Glycerin as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2019, 38, 6S–22S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbomer Carbopol®®®®®® ETD 2050. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1172655.pdf?bs=77&b=3755&st=1&sl=149106076&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbQ2FyYm9wb2zCriBFVEQgMjA1MF0%3d&k=Carbopol%c2%ae|ETD|2050&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Bergfeld, W.F.; Donald, F.A.C.P.; Belsito, V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Amended Safety Assessment of Acrylates Copolymers as Used in Cosmetics; Cosmetic Ingredient Review; CIR: Washingtone, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Castelain, F.; Kerre, S.; Carlet, C.; Goossens, A.; Girardin, P.; Pelletier, F.; Aubin, F. Allergic Contact Dermatitis from Carbomers: Two Case Report. Contact Dermat. 2020, 83, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozman, U.; Kalčíková, G. The First Comprehensive Study Evaluating the Ecotoxicity and Biodegradability of Water-Soluble Polymers Used in Personal Care Products and Cosmetics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 228, 113016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.O.; Lee, Y.M. Simultaneous Analysis of Mono-, Di-, and Tri-Ethanolamine in Cosmetic Products Using Liquid Chromatography Coupled Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2016, 39, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiume, M.M.; Heldreth, B.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; et al. Safety Assessment of Triethanolamine and Triethanolamine-Containing Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2013, 32, 59S–83S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Chang, H. Deciphering Trends in Replacing Preservatives in Cosmetics Intended for Infants and Sensitive Population. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phenoxyethanol (and) Ethylhexylglycerin Euxyl PE 9010 Preservative. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/en/eu/PersonalCare/Detail/33934/1318586/euxyl-PE-9010?st=1&sl=359373241&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbRXV4eWwgUEUg (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Radrezza, S.; Aiello, G.; Baron, G.; Aldini, G.; Carini, M.; D’amato, A. Integratomics of Human Dermal Fibroblasts Treated with Low Molecular Weight Hyaluronic Acid. Molecules 2021, 26, 5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essendoubi, M.; Gobinet, C.; Reynaud, R.; Angiboust, J.F.; Manfait, M.; Piot, O. Human Skin Penetration of Hyaluronic Acid of Different Molecular Weights as Probed by Raman Spectroscopy. Skin. Res. Technol. 2016, 22, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncan, A.M.; Moisă, D.G.; Santini, A.; Morgovan, C.; Rus, L.L.; Vonica-Țincu, A.L.; Loghin, F. Advantages of Hyaluronic Acid and Its Combination with Other Bioactive Ingredients in Cosmeceuticals. Molecules 2021, 26, 4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydrolyzed Hyaluronic Acid PRIMALHYAL 300. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1597712.pdf?bs=830&b=724176&st=1&sl=149148732&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbUHJpbWFsSHlhbOKEoiAzMDBd&k=PrimalHyal%e2%84%a2|300&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Mannitol Cellulose Calcium Sodium Borosilicate CI 77492 (US: Iron Oxides) Silica CI 77891 (US: Titanium Dioxide) CI 77480 (Gold) Tin Oxide Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose HYALUSPHERE PF. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/documents/1597711.pdf?bs=830&b=724168&st=1&sl=149110383&crit=a2V5d29yZDpbSFlBTFVTUEhFUkVd&k=HYALUSPHERE&r=eu&ind=personalcare (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Nanda, S.; Nanda, A.; Lohan, S.; Kaur, R.; Singh, B. Nanocosmetics: Performance enhancement and Safety Assurance. In Nanobiomaterials in Galenic Formulations and Cosmetics Applications of Nanobiomaterials; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 47–67. ISBN 9780323428682. [Google Scholar]

- Lipotec SNAP-8TM. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/en/eu/PersonalCare/Detail/2316/67495/SNAP-8-peptide-solution-C?st=1&sl=500143112&crit=U05BUC044oSi&ss=2 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Errante, F.; Ledwoń, P.; Latajka, R.; Rovero, P.; Papini, A.M. Cosmeceutical Peptides in the Framework of Sustainable Wellness Economy. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 572923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.M.; Yi, E.J.; Jin, X.; Zheng, Q.; Park, S.J.; Yi, G.S.; Yang, S.J.; Yi, T.H. Sustainable Dynamic Wrinkle Efficacy: Non-Invasive Peptides as the Future of Botox Alternatives. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, E.; Ferreira, L.; Correia, M.; Pires, P.C.; Hameed, H.; Araújo, A.R.T.S.; Cefali, L.C.; Mazzola, P.G.; Hamishehkar, H.; Veiga, F.; et al. Anti-Aging Peptides for Advanced Skincare: Focus on Nanodelivery Systems. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 89, 105087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givaudan Flashwhite Unispheres®®. Available online: https://www.ulprospector.com/en/eu/PersonalCare/Detail/830/594872/Flashwhite-Unispheres?st=1&sl=500142730&crit=Rmxhc2h3aGl0ZSBVbmlzcGh (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Klimek-szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Ekiert, H. Citrus Limon (Lemon) Phenomenon—A Review of the Chemistry, Pharmacological Properties, Applications in the Modern Pharmaceutical, Food, and Cosmetics Industries, and Biotechnological Studies. Plants 2020, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, C.M.; Lee, Y.M. Revolutionizing Cosmetic Ingredients: Harnessing the Power of Antioxidants, Probiotics, Plant Extracts, and Peptides in Personal and Skin Care Products. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Ma, H.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Sheng, W.; Xu, T.; Shen, L.; Wang, W.; et al. Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) with Heterologous Poly-γ-Glutamic Acid Has Skin Moisturizing, Whitening and Anti-Wrinkle Effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CosIng-Cosmetics Ingredients. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/cosing/details/35851 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Bergfeld, F.A.C.P.; Donald, V.; Belsito, D.E.; Cohen, C.D.; Klaassen, A.E.; Rettie, D.; Ross, T.J.; Slaga, P.W.; Snyder, D.V.M.; Tilton, S.C. Expert Panel for Cosmetic Ingredient Safety. In Safety Assessment of Hyaluronates as Used in Cosmetics; Cosmetic Ingredient Review (CIR); Final Report: CIR: Washingotn, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, W.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Belsito, D.V.; Hill, R.A.; Klaassen, C.D.; Liebler, D.C.; Marks, J.G.; Shank, R.C.; Slaga, T.J.; Snyder, P.W.; et al. Safety Assessment of Silk Protein Ingredients as Used in Cosmetics. Int. J. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 127S–144S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, B.; Rajkhowa, R.; Kundu, S.C.; Wang, X. Silk Fibroin Biomaterials for Tissue Regenerations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louiselle, A.E.; Niemiec, S.; Azeltine, M.; Mundra, L.; French, B.; Zgheib, C.; Liechty, K.W. Evaluation of Skin Care Concerns and Patient’s Perception of the Effect of NanoSilk Cream on Facial Skin. J. Cosmet. Dermatol 2022, 21, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Chen, H.; Dan, X.; Ju, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Lei, L.; Fan, X. Silk Fibroin for Cosmetic Dermatology. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 506, 159986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.S.; Costa, E.C.; Reis, S.; Spencer, C.; Calhelha, R.C.; Miguel, S.P.; Ribeiro, M.P.; Barros, L.; Vaz, J.A.; Coutinho, P. Silk Sericin: A Promising Sustainable Biomaterial for Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetics Europe. Guidelines on Stability Testing of Cosmetic Products. 2004. Available online: https://cosmeticseurope.eu/resources/guidelines-on-stability-testing-of-cosmetics-ce-ctfa-2004/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- ISO/TR:18811; Cosmetics-Guidelines on the Stability Testing of Cosmetic Products. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Juncan, A.M. Packaging Evaluation and Safety Assessment of a Cosmetic Product. Mater. Plast. 2018, 55, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eixarch, H.; Andrew, D. The Safety Assessment of Cosmetic Products. Pers. Care 2018, 4, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 6658:2005; Sensory Analysis—Methodology—General Guidance. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 21149:2017; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Enumeration and Detection of Aerobic Mesophilic Bacteria. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 16212:2017; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Enumeration of Yeast and Mould. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 22718:2016; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Detection of Staphylococcus Aureus. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 18416:2016; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Detection of Candida Albicans. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 21150:2016; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Detection of Escherichia Coli. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 22717:2016; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Detection of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 11930:2012; Cosmetics—Microbiology—Evaluation of the Antimicrobial Protection of a Cosmetic Product. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- SpheraCosmolife: New Software Specific for Risk Assessment of Cosmetic Products. Available online: https://www.vegahub.eu/portfolio-item/vermeer-cosmolife/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety. The SCCS Notes of Guidance for the Testing of Cosmetic Ingredients and Their Safety Evaluation, 12th ed.; SCCS: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Selvestrel, G.; Robino, F.; Baderna, D.; Manganelli, S.; Asturiol, D.; Manganaro, A.; Russo, M.Z.; Lavado, G.; Toma, C.; Roncaglioni, A.; et al. SpheraCosmolife: A New Tool for the Risk Assessment of Cosmetic Products. Altex 2021, 38, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmetics Europe. Product Test Guidelines for the Assessment of Human Skin Compatibility. 1997. Available online: https://cosmeticseurope.eu/resources/guidelines-for-assessment-of-skin-tolerance-of-potentially-irritant-cosmetic-ingredients-1997 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).