Abstract

The latest trends focus on increasing the nutritional value of food products, including yogurts, by fortifying them with bioactive compounds derived from natural ingredients, in line with the concept of “food-to-food fortification”. Mushrooms are a rich source of protein, dietary fibre, certain vitamins, minerals, and numerous bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides (β-glucans) and phenolic compounds. Biologically active substances found in mushrooms exhibit numerous biological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, hypocholesterolaemic and immunomodulatory properties. This study aimed to determine the potential of edible mushrooms as functional additives in yogurt production, based on a review of the scientific literature. The study discusses the effects of various forms of mushroom additives (powders, aqueous and ethanolic extracts, polysaccharides, β-glucans) on the course of lactic acid fermentation, the growth and survival of lactic acid bacteria, and the physicochemical and sensory properties of yogurts. In most cases, the addition of mushrooms increased the activity of lactic acid bacteria, increased the acidity, viscosity, and hardness of yogurt, and reduced syneresis, thereby improving its stability. This effect is mainly due to mushroom polysaccharides, including β-glucans. In turn, the presence of antimicrobial and antioxidant compounds significantly limits the growth of undesirable microorganisms and slows lipid oxidation, thereby extending the shelf life of yogurts. The addition of edible mushrooms to yogurts, in various forms, is a safe and effective way to create a functional product that meets consumer expectations, but it requires optimising the form and concentration of the additive.

1. Introduction

Humans began consuming milk and dairy products as early as the Neolithic Revolution, when hunter-gatherer communities transitioned to a settled lifestyle based on agriculture and the domestication of milk-producing animals [1,2,3]. Milk and dairy products remain an important element of the daily diet. They are a source of easily assimilable and valuable protein and provide essential minerals, such as calcium, magnesium and potassium, as well as vitamins, mainly A and D, and B-group vitamins [2,4,5]. Regarding fermented dairy products, their nutritional value and health benefits are additionally enhanced by the presence of beneficial microbiota and their metabolites. Furthermore, the lactic acid fermentation process reduces the lactose content, thus increasing the digestibility of yogurts and cheeses [4,6,7,8]. Yogurt is one of the most popular dairy products. According to a definition by Codex Alimentarius [9], conventional yogurt is milk that has been acidified and coagulated using lactic acid bacteria (LAB) of the species Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. In addition to conventional yogurts, Codex Alimentarius provides for yogurts with microflora modified using a culture of Streptococcus thermophilus and any culture of the Lactobacillus genus. The most common additional microorganisms used in yogurt production include Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, L. rhamnosus, and various species of the Bifidobacterium genus. Microflora with potential probiotic properties may also be considered additional microflora. In accordance with the requirements, the product must contain live bacterial cultures that remain active until the “best before” date, except for yogurts that have been thermised. Most industrial yogurt production uses cow’s milk with varying fat content, including powdered or skimmed milk [10]. Yogurts are also produced from goat, sheep, camel, buffalo and donkey milk [11], with plant-based equivalents of this drink also being commercially available [12,13].

Natural yogurts are perceived as minimally processed, low-calorie products that positively affect health, and rarely contain additives. There is also a whole range of flavoured (e.g., fruit-flavoured) yogurts, which consumers often consider a sweet snack [14]. A variety of functional yogurts are also available on the market, including probiotic, prebiotic, symbiotic, high-protein, and others [15,16,17]. Among dairy products, yogurt is one of the most commonly used to provide consumers with bioactive compounds, both because of its high popularity and its rather neutral flavour, which can be easily modified [18].

Yogurts, despite their advantages, fail to provide all the necessary components. For example, they lack fibre, which is important for digestion and intestinal health [19,20,21], or iron, the deficiency of which is the most commonly observed nutritional issue [21,22,23]. Milk and dairy products are most commonly fortified with minerals and vitamins [24,25,26,27]. In countries such as Canada, Finland and China, fortification of milk with vitamin D and iron is mandatory. Some Latin American countries have introduced mandatory fortification of milk with vitamins A and D to tackle nutritional deficiencies [28]. This example illustrates interventional fortification, which aims to prevent or reduce nutrient deficiencies in the general population or specific groups [29]. Simultaneously, it involves compensatory fortification, designed to offset nutrient losses caused by processing. For vitamins A and D, this process occurs during the skimming of whole milk [27].

The third component most commonly added to dairy products is fibre, mainly its soluble fraction. The addition of soluble fibre in the form of fructo-oligosaccharides, β-glucans, polyfructans, alginate, carrageenan, guar gum, xanthan gum and pectin allows specific technological effects to be achieved. It improves the water-holding capacity in the product, increases production efficiency, enhances texture, reduces calorie content, and, in the case of fermented products, acts as a prebiotic [30,31,32]. Fortifying dairy products with fibre also provides certain health benefits, due to the properties of this additive [32].

The latest trends focus on increasing the nutritional value of food products, including yogurts, by fortifying them with bioactive compounds derived from natural ingredients, primarily plant-based, but also animal- and mushroom-based [28,33]. This aligns with the so-called “food-to-food fortification” (FtFF) approach, which involves the addition of one or more food products rich in specific micronutrients to commonly consumed products [34,35].

The most commonly added natural ingredients to yogurts include fruit, cereals, honey, as well as vegetables, seeds, and herbs [18,21,36,37,38,39]. These raw materials are a source of valuable nutrients and health-promoting substances, which improve the flavour and aroma, thereby increasing their attractiveness to consumers, but they can also enhance the stability and microbiological safety of dairy products [33]. Edible mushrooms or products derived from them (powders, extracts, isolates) are much less commonly used as additives. This study aimed to assess the current state of knowledge regarding the use of edible mushrooms as a natural source of bioactive compounds that enhance the nutritional and health-promoting value of yogurts.

2. Methods

This review focuses primarily on studies assessing the effects of adding edible mushrooms, in various forms, on yogurt properties. As information on the chemical composition of mushrooms is essential for understanding their technological and functional impact in dairy matrices, an additional comprehensive introductory section describing the nutritional and bioactive properties of edible mushrooms was included. To identify relevant literature, the databases Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar were comprehensively searched. The search covered mainly the period from 2015 to 2025, with earlier key sources considered where necessary. The keywords used were related to the characteristics of yogurts (“yogurt”, “yoghurt”, “dairy products”, “starter cultures”, “technological process”, “fortification”, “additives”), mushrooms (“edible mushrooms”, “bioactive compounds”, “β-glucans”, “polysaccharides”, “prebiotic properties”, “health-promoting properties”, “antioxidant properties”). Combinations of keywords were used as well (e.g., “yogurt” + “starter cultures”, “edible mushrooms” + “β-glucans”, “edible mushrooms” + “yogurt”). The articles were searched by title, abstract and full text. Articles on plant-based yogurts were excluded from the search results. Given the wide variety of methods used across studies, only a descriptive synthesis of the results was performed.

3. Properties of Edible Mushrooms

The term ‘mushrooms’ commonly refers to the visible parts, the so-called fruiting bodies, of macroscopic species (macrofungi) [40]. Mushrooms belong to their own distinct kingdom of Fungi. From a practical perspective, mushrooms can be divided into three main groups: edible, medicinal and toxic mushrooms. According to Das et al. [41], they account for 54%, 38% and 8% of the total, respectively, while Losoya-Sifuentes et al. [40] report that approximately 3000 species are suitable for consumption, approximately 700 show medicinal properties, and 1% are poisonous. According to Li et al. [42], who reviewed all edible mushroom species worldwide, 2189 edible species have been identified. Of these, 183 species are conditionally safe, meaning they require specific pre-treatment before consumption or can cause allergies in some people. Among this enormous number of edible mushroom species, several of the most popular and most commonly consumed should be highlighted. These include Agaricus bisporus (button mushroom), Lentinula edodes (shiitake), Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushroom) and Flamulina velutipes (enoki) [40,41,43,44]. Currently, most mushrooms available on the market are cultivated. Globally, 25–35 mushroom species are commonly cultivated [41,45], yet the practical possibilities are much greater. In China alone (the world’s leading producer of edible cultivated mushrooms), more than 60 species of edible and medicinal mushrooms are commercially cultivated, and another 200 are successfully cultivated on a laboratory scale [46].

3.1. Nutritional Value

The nutritional value and benefits linked to eating mushrooms have been known for a very long time. The ancient Romans considered mushrooms to be the food of the gods. Hippocrates wrote about the medicinal properties of mushrooms around 400 BC. These properties were particularly appreciated in Asian countries such as China, Japan and Malaysia. In European countries, mushrooms have been valued mainly for their flavour and aroma [40,41,47,48].

The nutritional values and sensory properties of mushrooms are determined by their chemical composition, which is influenced by many different factors, including the composition of the substrate, external conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, insolation, etc.), the stage of mycelium development, and the degree of fruiting body maturity [49,50,51,52]. The average essential nutrient contents of the most popular edible mushroom species are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Nutrient content of the four most popular species in 100 g of fresh edible mushrooms [53].

Mushrooms are low in calories, as 100 g of fresh mushrooms provides approximately 24–39 kcal [41,44]. As reported by Kalač [54], the dry matter content ranges from 8.33% to 28.5% in some wild-growing mushrooms, and from 8.36% to 20.22% in some cultivated mushrooms. Carbohydrates constitute the major proportion of dry matter. This fraction comprises digestible and non-digestible carbohydrates, such as dietary fibre [40,52,54]. In terms of simple sugars, disaccharides and polyols, i.e., glucose, trehalose and mannitol that are present in the highest quantities. They contribute to the flavour of mushrooms and are an effective indicator of their freshness [55,56]. The highest carbohydrate content is found in fresh A. bisporus fruiting bodies. After 12 days of mushroom storage at 12 °C, total carbohydrate content decreased by 55% [57]. Mushroom cell walls contain large amounts of polysaccharides, such as chitin, hemicellulose, mannans and β- and α-glucans. They provide dietary fibre, which is important for proper intestinal function [58]. According to Atila et al. [56], the chitin content of A. bisporus is 9.6 g/100 g DW, and is significantly higher than that for the fruiting bodies of P. ostreatus or L. edodes. Certain mushroom polysaccharides, mainly β-glucans, exhibit strong biological activity [57,59,60]. Particularly noteworthy are (1,3)-β-glucans, which have a β-(1,6) branching at every fifth residue. These polymers are characterised by high molecular weight, water solubility and high anti-carcinogenic activity [49].

Mushrooms are a valuable, non-animal source of protein, the content of which in the dry matter of mushrooms usually accounts for 20–40%. Mushroom protein is considered more easily digestible than protein from certain plants, such as soybeans or peanuts [49]. Protein digestibility for some mushroom species is as high as 90% [61]. According to Correa et al. [62], mushrooms contain less crude protein than meat, but considerably more than most other food products, including milk. Mushroom protein contains all essential amino acids, making it a viable substitute for meat in the diet [63,64]. In most popular edible mushroom species, glutamic and aspartic acids are the most abundant amino acids [65]. These compounds are precursors to other amino acids, and in their free form, they are responsible for the characteristic umami flavour [66,67]. As reported by Jabłońska-Ryś and Przygoński [68], fruiting bodies of A. bisporus, P. ostreatus and L. edodes contain 37.57, 15.52 and 27.00 mg/g DW of aspartic acid, and 47.78, 18.52 and 56.28 mg/g DW of glutamic acid, respectively. According to Han et al. [69], 100 g DW of F. velutipes fruiting bodies contain 0.824–1.176 g of aspartic acid and 1.999–3.161 g of glutamic acid, depending on the substrate composition.

The overall fat content of edible mushroom fruiting bodies is relatively low, but mushrooms are characterised by a favourable ratio of unsaturated to saturated fatty acids [54]. As far as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are concerned, linoleic acid is typically the most predominant [54,70,71]. According to Baars et al. [72], linoleic acid accounts for 90% of all fatty acids in the fruiting bodies of A. bisporus. In turn, Das et al. [41] report that this proportion for the fruiting bodies of A. bisporus, P. ostreatus and L. edodes accounts for 40.33%, 65.59% and 58.23%, respectively, while Jabłońska-Ryś and Przygoński [68] report the following values for the same species, respectively: 63.07%, 32.50% and 26.33%. The main monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) in most popular edible mushrooms is oleic acid, and the predominant saturated fatty acid (SFA) is palmitic acid [68,71].

Mushrooms are a favourable source of B-group vitamins, mainly thiamine, riboflavin, pyridoxine, pantothenic acid, nicotinic acid, folic acid and cobalamin. The vitamin B2 content of mushrooms is higher than that in many vegetables [49,56,61]. Mushrooms are the only non-animal source of vitamin D, as they contain its precursor, ergosterol. This compound is a component of mushroom cell membranes, and, under UV radiation, readily converts to ergocalciferol, or vitamin D2 [73,74,75]. For this reason, cultivated mushrooms usually contain lower amounts of vitamin D2 than wild mushrooms, which have access to sunlight [56]. However, mushroom fruiting bodies can be effectively irradiated with UV radiation after harvesting. UVB radiation increases the vitamin D2 content in A. bisporus fruiting bodies from 5.5 μg/100 g DW to 410.9 μg/100 g DW [76], and in the case of P. ostreatus and L. edodes, from 0.83 μg/g DW to 69.00 μg/g DW, and from 0.35 μg/g DW to 15.10 μg/g DW, respectively [77]. Research has shown that the amount of vitamin D2 in irradiated mushrooms can, in some cases, be up to 5000 times greater than that produced by sunlight [78]. When exposed to UVB radiation, dried mushrooms can convert ergosterol into vitamin D2 [73]. Other ergosterol derivatives found in mushrooms include ergosta-5,8,22-trien-3-ol, ergosta-7,22-dien-3-ol, ergosta-5,7- dien-3-ol and ergosta-7-en-3-ol. Interest in mycosterols stems from their ability to reduce cholesterol absorption and lower LDL cholesterol levels in plasma without causing side effects [49].

Mushrooms also contain small amounts of vitamins C and E, and provitamin A. Cultivated mushroom species generally have lower contents of these vitamins than wild mushrooms [54].

Mushrooms are a widely recognised source of minerals. The ash content of mushrooms ranges from 60 to 120 g/kg DW. Wild species exhibit greater diversity than cultivated species due to the greater variability of substrate components [54]. Of the major elements, potassium is found in the largest quantities. This element is significantly concentrated in mushrooms, with the fruiting bodies containing 20–40 times more than the substrate, while mushroom caps contain higher amounts than stems [43,79]. In terms of potassium and phosphorus contents, mushrooms are superior to most vegetables [54]. Importantly, mushrooms are low in sodium. This element plays a crucial role in the human body, but the average diet often contains excessive sodium, which increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases, particularly hypertension [80]. The fruiting bodies of various mushroom species, including Pleurotus spp., A. bisporus and L. edodes, have also been found to contain trace elements such as copper, zinc, iron, manganese, molybdenum and selenium [61]. Their content varies significantly between species and is also significantly determined by the composition of the substrate. Most edible mushrooms are poor sources of selenium, a micronutrient essential for humans, yet the content of this element in fruiting bodies can be significantly increased by irrigating the substrate with a sodium selenite solution [56]. Wild-growing mushrooms can accumulate high levels of, e.g., cadmium and mercury, if growing in contaminated areas [54,81].

3.2. Health-Promoting Properties

Mushrooms, both medicinal and edible, exhibit several health-promoting properties resulting from the various biologically active substances found in this raw material (Table 2). Kumar et al. [47] report that bioactive compounds found in mushrooms exhibit over 120 various health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-carcinogenic, immunostimulatory, hypocholesterolaemic, hypoglycaemic, antimicrobial, antiviral and many others. However, it has not been discovered in every case which specific components of mushrooms are responsible for the individual properties.

3.2.1. Antioxidant Properties

Edible mushrooms exhibit strong antioxidant properties due to their bioactive compounds, primarily polyphenols [49,82]. Among cultivated species, in terms of total phenolic compound content, free radical scavenging capacity and the reducing power, A. bisporus fruiting bodies have the highest potential compared to P. ostreatus and L. edodes [49,52,83]. The phenolic compound content and antioxidant activity are determined by the morphological part of the fruiting bodies, and, in general, slightly higher activity is noted for the caps than for the stems [84]. The most common phenolic compounds found in mushrooms include phenolic acids and flavonoids. In addition to antioxidant properties, they also exhibit anti-inflammatory, anti-cancerogenic, antihyperglycaemic, antiosteoporotic, antityrosinase and antimicrobial activities [85].

Polysaccharides, particularly β-glucans, also exhibit antioxidant properties. Their capacity to scavenge free radicals, reduce oxidative stress, and chelate Fe2+ contributes to their antioxidant activity. Additionally, they can inhibit lipid peroxidation, carry out erythrocyte haemolysis and increase enzyme activity in cells [82].

Mushrooms contain derivatives of indolic compounds, e.g., serotonin. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter and tissue hormone that plays a crucial role in regulating mood, sleep, appetite and other processes occurring in the body. This compound also exhibits antioxidant properties. Its content in A. bisporus was estimated at 5.21 mg/100 g DW. A better source of serotonin are the fruiting bodies of Cantharellus cibarius, which contain 29.61 mg/100 g DW [86].

Antioxidant properties are also exhibited by vitamins found in edible mushrooms, namely vitamins E, C and D, and provitamin A (β-carotene). Vitamin E is found in mushrooms in the form of α, β, γ and δ tocopherols. A high β-tocopherol content of 0.85 μg/100 g of fresh weight has been noted in the fruiting bodies of A. bisporus [52]. The most active form of vitamin E is α-tocopherol, whose main role is to protect cell membranes against lipid peroxidation [82]. Kozarski et al. [87] noted the presence of ascorbic acid in the fruiting bodies of C. cibarius at a level of 100 mg/100 g DW. Vitamin C is the primary antioxidant in the plasma and cells [82].

Table 2.

Bioactive compounds of the four most popular species of edible mushrooms.

Table 2.

Bioactive compounds of the four most popular species of edible mushrooms.

| Species | Compounds | Properties | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. bisporus | Phenolic acids | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, antimicrobial, antiviral; | [88,89,90] |

| Lectins (ABA—Agaricus bisporus agglutinin) | Immunomodulatory, antiproliferative, anti-carcinogenic; | [88,89] | |

| α-glucan | Induced tumour necrosis factor production; | [91,92] | |

| β-glucan | Increased monocyte proliferation, prebiotic; | [88,90,92] | |

| Ergosterol | antioxidant, antimicrobial, anticancer, antidiabetic, antineurodegenerative; | [90,93] | |

| Ergothioneine | Hypotriglyceridemic, antioxidant, antiatherosclerotic, hypocholesterolaemic, reducing oxidative stress; | [88,89] | |

| Agarodoxin (benzoquinone derivate) | Antibacterial; | [89] | |

| Lovastatin | Anticancer, antihyperlipidemic. | [89,94] | |

| L. edodes | β-glucan—lentinan | Anticancer, hypoglycaemic, immune-boosting; | [95,96,97] |

| Lectins | Antiproliferative, anticancer, antiviral, immune-stimulating potential; | [95,98,99] | |

| Eritadenine | Hypocholesterolaemic, hypotensive, antiparasitic | [95,100] | |

| Protein hydrolysates | Antioxidant; | [101] | |

| Polysaccharides | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiaging, immunomodulatory, antiviral, hepatoprotection effects, antiatherosclerotic; | [96,102,103] | |

| Lentinmacrocycles A-C and Lentincoumarins A-B | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory; | [104] | |

| Lenthionine | Antimicrobial; | [96] | |

| Polyacetylenes and sulphur compounds | Antimicrobial; | [105] | |

| Polyphenols | Antioxidant, hepatoprotection effects. | [96] | |

| P. ostreatus | Phenolic acids | Antioxidant; | [106] |

| Flavonoids | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative; | [107] | |

| Polysaccharides | Anticancer, hepatoprotective, prebiotic, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antidiabetic, antioxidant; | [106,107,108] | |

| β-glucan—pleuran | Antibacterial, antiviral, prebiotic, immunomodulatory, antioxidant; | [107,109,110] | |

| Chitosan | Antimicrobial; | [109] | |

| Lectins | Anticancer, antiviral; | [106,109] | |

| Ergosterol | Hypocholesterolaemic, antioxidant; | [107,110] | |

| Lovastatin | Hypocholesterolaemic. | [110] | |

| F. velutipes | Flammulinolide, enokipodin, proflamin | Anticancer, anti-hypertension, anti-hypercholesterolemic; | [111,112] |

| Polysaccharides | Immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-aging, neuroprotective; | [113,114,115,116,117] | |

| Phenolic acids | Antioxidant; | [112] | |

| Arbutin, epicatechin, phillyrin, kaempferol, formononetin | Neuroprotective, antioxidant, anticancer; | [118] | |

| Sesquiterpenes | Antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant; | [112,117,119] | |

| Ergosterol | Anticancer. | [120] |

Orange-coloured mushroom species contain β-carotene [121]. Vitamin D2, found in mushrooms, similarly to vitamin D3, is a membrane antioxidant and inhibits iron-dependent peroxidation of liposomal lipids [82]. The precursor to vitamin D2, ergosterol, also exhibits similar properties [93].

The antioxidant properties of mushrooms are also linked to ergothioneine, a histidine derivative. Ergothioneine has the capacity to reduce pathological lesions caused by radiation, hypoxia (following transplants), myocardial infarction or stroke. In addition to its antioxidant activity, ergothioneine also exhibits antimutagenic, chemoprotective and radioprotective properties [89].

Some trace elements are cofactors of enzymes with antioxidant functions and are referred to as antioxidant micronutrients. Selenium is the main antioxidant, acting through selenoproteins to reduce the cytotoxic effects of reactive oxygen species. Several selenium compounds have been identified in fungi, including selenomethionine, selenocysteine, Se-methylselenocysteine, selenite and seleno-polysaccharides [82].

3.2.2. Anticancer Properties

To date, numerous compounds with anti-carcinogenic potential have been identified in mushrooms, both with low molecular weight (e.g., quinones, cerebrosides, isoflavones, catechols, amines, triacylglycerols, sesquiterpenes, steroids, organic germanium and selenium) as well as with high molecular weight (e.g., homo- and heteroglucans, glycans, glycoproteins, glycopeptides, proteoglycans, proteins and RNA-protein complexes) [122,123].

The compounds most extensively studied for anticarcinogenic activity are polysaccharides. They are believed to be present in all higher mushroom species. This is because, along with chitin, they are essential components of the mushroom cell wall [49]. Due to their chemical structure, polysaccharides can be divided into homo- and heteroglucans. The former group includes, e.g., α- and β-glucans. Particularly noteworthy are (1,3)-β-glucans, which are characterised by high molecular weight, water solubility and high anti-carcinogenic activity [124]. Examples of such compounds with anti-carcinogenic properties include lentinian (isolated from the fruiting body and the mycelium of L. edodes), pleuran (from P. ostreatus), grifolan (from Grifola frondosa), and krestin (from Trametes versicolor) [124,125]. These compounds activate and regulate the immune system by affecting the maturation, differentiation and proliferation of immune system cells, thereby inhibiting metastasis and the growth of neoplastic cells [126]. Further possible mechanisms include the induction of apoptosis or the inhibition of neoplastic cell proliferation [127]. β-glucans are effective in the treatment of many types of neoplasms, including pancreatic, colon, oesophageal, bladder epithelial, ovarian, cervical, gastric, lung, head and neck, and other cancers [127,128]. They are also known for their immunostimulant, anticholesterolemic, anti-inflammatory and prebiotic effects [59].

Other mushroom compounds with anti-carcinogenic properties are lectins. These are proteins or glycoproteins capable of exerting cytotoxic effects on neoplastic cells. Their activity is linked to the activation of apoptotic pathways in cancer cells. Lectins are found in the fruiting bodies of many edible mushroom species, e.g., A. bisporus, P. ostreatus, L. edodes and F. velutipes [129,130].

3.2.3. Hypocholesterolaemic Properties

In Oriental medicine, it is recommended to include edible mushrooms in a cholesterol-lowering and anti-atherosclerotic diet. A study indicates that mushroom consumption may help lower total serum cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglyceride levels, attributed to the high fibre content of mushrooms [131]. Mushrooms also contain other compounds that are capable of lowering blood cholesterol levels. Mycosterols exhibit effects similar to those of phytosterols, reducing cholesterol absorption in the human intestine. For example, ergosterol obtained from A. bisporus, when incorporated into fat matrices, significantly reduced cholesterol and triglyceride levels and showed great potential for combating fatty liver disease [132]. In turn, eritadenine from L. edodes, by inhibiting the enzyme S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase, accelerates cholesterol metabolism in the liver, thereby reducing blood plasma cholesterol levels [133]. Another example of a substance that lowers blood cholesterol levels is lovastatin, which has a hypocholesterolaemic effect by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase, the enzyme required for cholesterol synthesis [133,134]. This compound is found in large quantities in A. bisporus and P. ostreatus at 560 and 600 mg/kg DW, respectively [49].

3.2.4. Antimicrobial Activity

Mushrooms synthesise specific secondary metabolites which protect them against pathogen attacks. These compounds may be useful in inhibiting bacterial or mould growth. Low-molecular-weight compounds exhibiting antimicrobial activity include oxalic acid, terpenes and steroids, while high-molecular-weight compounds primarily include proteins and peptides [49]. A compound with strong antibacterial and antifungal activity is lenthionine, an exobiopolymer containing sulphur, found in L. edodes [135]. The antibacterial properties of F. velutipes are mainly attributable to polyphenols, which interact with the cell membrane of bacteria and disrupt their functions, as well as aldehydes and ketones [136]. In many cases, however, it is difficult to identify a specific compound in the resulting mushroom extracts that exhibits antimicrobial activity. Extracts from various species of edible mushrooms effectively inhibit the growth of, among others, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans [131].

3.2.5. Antiviral Activity

Polysaccharides, carbohydrate-binding proteins, peptides, proteins, enzymes, polyphenols, triterpenes, triterpenoids, and other compounds found in mushrooms exert antiviral activity. Depending on the type of compound, antiviral activity may be direct or indirect and is associated with modulation of the host’s immune system [137,138]. Some mushroom compounds effective against HIV, influenza A virus and hepatitis C virus showed efficacy comparable to that of antiviral drugs [137]. The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that traditional Chinese medicine, including mushroom-based treatments, is safe and effective for the treatment of COVID-19 [138]. Lectins are a promising group of compounds with antiviral activity. This protein can inhibit viral activity by binding to the virus’s surface glycoprotein, blocking the host receptor, or inhibiting the viral polymerase enzyme by binding to its active site. The antiviral activity of fungal lectins against HIV has been most comprehensively studied [129,139].

3.2.6. Anti-Diabetic Activity

The consumption of certain mushrooms helps control and treat diabetes mellitus. The compounds in this raw material stimulate insulin secretion by the pancreas, help lower blood glucose levels, and exhibit α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, which improves glucose uptake by cells [140,141]. Bioactive mushroom metabolites with anti-diabetic potential include, e.g., polysaccharides, proteins, dietary fibre, vitamin D, as well as various mushroom extracts containing unknown metabolites [141,142]. Compounds isolated from popular edible mushroom species, such as Pleurotus spp. [143,144], L. edodes [145] and A. bisporus [52,144,146], exhibit promising health benefits in the treatment of type 2 diabetes, with therapeutic effects similar to those observed in highly valued medicinal mushrooms. The high fibre content in mushrooms inhibits the action of digestive enzymes, which lowers blood glucose levels. Molecules similar to lectins also contribute to lowering glucose levels and increasing the insulin content [52].

3.2.7. Anti-Inflammatory Properties

Edible mushrooms are considered potentially helpful in the prevention and treatment of inflammatory conditions. Anti-inflammatory compounds in mushrooms are a diverse group in terms of chemical structure. These include polysaccharides, terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and many other low-molecular-weight molecules [147]. Polysaccharides found in edible mushrooms exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by regulating cytokine secretion in inflammatory cells. Pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory properties are exhibited by mannogalactan, fucomannogalactan and fucogalactan isolated from A. bisporus [52]. Cerletti et al. report that β-glucans modulate or attenuate the ongoing inflammatory response induced by inflammatory stimuli [60]. It has been shown that polysaccharides from edible mushrooms alleviate intestinal inflammation by regulating the intestinal mucosal barrier, which may help treat inflammatory bowel disease [148].

The anti-inflammatory effect of mushrooms also results from the presence of indolic compounds and selected minerals. Enriching the mycelium with micronutrients, such as zinc, copper, or selenium, enhances the anti-inflammatory properties of L. edodes extracts [149].

3.2.8. Other Properties

Mushrooms are used as immune system stimulators and modulators in the treatment of certain diseases associated with immunodeficiency. Polysaccharopeptides, ubiquitin-like peptides, ubiquinone-9, glycoproteins, nebrodeolysin, proteoglycans, and glucans found in P. ostreatus strengthen the immune response in the human body. Lectins stimulate the maturation of immune cells [47,144]. Mushroom polysaccharides can modulate immune function by altering the composition of the intestinal microbiome [150]. Mushrooms also exhibit hepatoprotective effects. These properties are mainly attributable to phenolics, triterpenes, polysaccharides and peptides [144,151]. Mushrooms, highly nutritious raw materials that contain a variety of bioactive compounds, are increasingly appreciated for their role in obesity, as they are low in calories and rich in fibre. It has also been demonstrated that the compounds found in mushrooms may be helpful in treating obesity-related diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, atherosclerosis and dyslipidaemia [152].

Due to their high nutritional value and a wide range of health-promoting effects, resulting from the presence of various active substances, mushrooms are certainly a valuable component of people’s diet.

4. Incorporating Mushrooms in Yogurt

Mushrooms are increasingly being used as functional additives in many food products due to their properties. They are used fresh, dried, or as extracts, serving as substitutes for meat, fat, flour or even salt [153,154,155]. They fortify food products with minerals, protein, fibre and antioxidant compounds, providing a number of health benefits [41,144,156,157]. Among the most commonly fortified products are bakery products, such as bread, biscuits, cookies and cakes, in which the addition of mushrooms affects nutritional, rheological, physicochemical, textural and sensory properties [156,158]. Mushrooms are also used as an additive in various types of dairy products. Table 3 summarises the possibilities for using different types of mushrooms in yogurts and indicates the main effects of their use.

Table 3.

Possibilities of using edible and medicinal mushrooms in yogurts.

4.1. The Form of a Mushroom Additive

Pleurotus ostreatus is the most commonly used edible mushroom for fortifying yogurts [175,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190]. Several studies are dedicated to A. bisporus [159,160,161,162] and L. edodes [167,174,175]. The effect of the addition of F. velutipes on yogurt properties has also been studied [167]. Other studies examine the potential use of various edible and medicinal mushroom species, the most popular of which is G. lucidum [162,168,169,170,171].

Mushrooms can be added to yogurt in various forms. The simplest method for incorporating valuable mushroom-derived nutritional and health-promoting components is to add mushrooms in the dried and powdered form. This form is closest to the FtFF concept, which involves the use of balanced food products or minimally processed natural ingredients to enhance the nutritional value of another food product, in this case, yogurt [34,35]. Mushroom powders, unlike isolated ingredients, represent a complex matrix of bioactive substances. Their incorporation into a fermented milk matrix certainly supports synergy among the individual ingredients of fortified yogurts, thereby resulting in additional, often multidirectional effects. As observed by Atik et al. [168], the addition of G. lucidum in powder form exerted a greater effect on the physicochemical, microbiological, textural and sensory properties than that in the form of an aqueous extract.

The raw material for powder production was usually the fruiting bodies of mushrooms or their caps. It is worth noting, however, that stems, which are often considered production waste [174,184], or fruiting bodies that do not meet size or appearance requirements, can also be used [163]. This waste can be a valuable raw material for the production of mushroom powders or extracts, enabling the fortification of yogurts with mushrooms in an economically and technologically sustainable manner.

Fresh mushroom fruiting bodies were convectively dried at 40–65 °C [159,174,180,182,184] or freeze-dried [168,173,181,183]. Alternatively, the raw material for the study was purchased as mushroom powder [172,179]. The drying method can significantly affect the chemical composition and properties of mushroom powders or extracts derived from them. Shams et al. [193] demonstrated that freeze-dried A. bisporus powders contain significantly higher levels of total phenolic compounds and exhibit greater antioxidant activity than powders obtained by convection drying. The drying process can also affect the structural characteristics of mushroom polysaccharides. Hot-air drying modifies the β-configuration in polysaccharides and, consequently, contributes to changes in their properties [194]. The drying method significantly influences the physical parameters of mushroom powders. Freeze-dried powders are characterised by a more porous structure and smaller granulation than powders obtained by the convection method [195], which significantly affects the rehydration process and, thus, the extraction efficiency. Freeze-dried samples are also characterised by a significantly higher L* parameter value and, at the same time, lower a* and b* parameter values than convection-dried samples [193], which may affect the colour development of fortified products. Zhang et al. [196] demonstrated that the drying process affects mushroom flavour. The authors compared four drying methods for L. edodes fruiting bodies, including freeze-drying and convection drying. The results showed that freeze-drying is an effective method for obtaining umami flavour in dried mushrooms. Unfortunately, freeze-dried samples also contained the most bitter-tasting amino acids.

The addition of mushroom powder to yogurts varied from 42 mg/L for G. frondosa [172] to a maximum of 5% for A. bisporus [159] and P. ostreatus [183]. Dried solid residues remaining after industrial water extract production [171], as well as mycelia [176,190] have also been used.

Mushrooms have also been added to yogurts in the form of extracts, primarily aqueous extracts, at 0.25–10% [177,185,186,187,188]. Additionally, aqueous extracts after evaporation and drying at 40 °C have been used at concentrations of 0.05–0.1% [164]. Ethanolic extracts were used less frequently, at concentrations ranging from 40 mg/50 g to 18.75 mg/mL [160,161], and after complete evaporation, at 737 mg/50 g [163]. The extraction method and the type of solvent used significantly affect the retention of bioactive compounds in the mushroom component and, thus, their functionality in yogurt. Aqueous mushroom extracts, particularly those obtained by hot water extraction, are rich primarily in soluble polysaccharides (mainly β-glucans and other heteroglycans) and polysaccharide-protein complexes, as well as selected polar metabolites and a portion of phenolic compounds. Ethanolic extracts, on the other hand, mainly contain phenolic acids and other phenolic compounds, triterpenoids, sterols, including ergosterol, and other less polar secondary metabolites. Ethanolic extracts usually exhibit greater antioxidant activity [47,197,198,199,200,201,202]. The efficiency of extraction is also influenced by parameters such as temperature, time, and other factors, e.g., ultrasound-assisted extraction. The interpretation and comparison of the results of individual studies on the use of mushroom extracts in yogurts are seriously hindered by the fact that, in these studies, authors apply different techniques for pre-treating the raw material, use different extraction protocols, and often employ different methods for determining bioactive compounds.

Francisco et al. [161] fortified yogurts with ethanolic extracts, free (40 mg/50 g) and microencapsulated (2.5 g/50 g) from A. bisporus fruiting bodies. Microencapsulation was performed by spray drying using maltodextrin crosslinked with citric acid as the encapsulating material. This process is justified as it helps maintain the biological activity of extracts during the storage of fortified food products [157]. The microencapsulation technique is fairly widely described in scientific literature as a technology that helps protect probiotics and various bioactive ingredients added to yogurt. Microencapsulation of probiotic bacteria increases their survival during the fermentation and storage of yogurt, as well as during passage through the human digestive system [203,204]. Microencapsulated bioactive compounds or plant extracts, which are sources of vitamins, pigments or phenolic compounds, are protected in the acidic environment of yogurt, and released in a controlled manner in the digestive tract [205,206,207,208].

Another additive to yogurts has also been specific compounds isolated from various mushroom species, purified to varying degrees. These are primarily polysaccharides, added at 0.1–3% as an extract or a dried extract [162,165,166,167,189,192], and β-glucan at 0.3–1.5% [169,170,178]. In the case of L. edodes and P. ostreatus, this compound was also applied as a 1% hydrogel [175]. The commercial preparation Ganogen, containing β-glucans from G. lucidum, has also been used as an additive [169]. It should be noted that mushroom polysaccharides, including β-glucan, are polar compounds, highly soluble in water, and, therefore, they generally represent the main fraction of aqueous mushroom extracts [209]. The use of mushroom additives in the form of highly processed fractions, such as purified polysaccharides or standardised β-glucan, may provide the most predictable and repeatable technological effects, as well as the highest repeatability of health-promoting functions and reduced sensory changes, but they are limited in their compatibility with the FtFF concept.

Most studies added mushroom additives to yogurts before milk homogenisation and pasteurisation. This ensures better dispersion and integration of the mushroom component into the milk matrix, and a lower tendency to sediment in the case of solid particles (mushroom powders). The pasteurisation process contributes to the inactivation of mushroom enzymes that may have remained partially active, especially in the absence of prior high-temperature treatment, and to the enhancement of microbiological quality. In several studies, mushroom additives were added after the pasteurisation and cooling of milk [164,168,173,174]. In some cases, this may lead to deterioration in yogurt quality, e.g., due to increased syneresis resulting from the activity of mushroom proteases [164].

Research conducted to date has mainly focused on assessing the effects of adding mushrooms, in various forms, on the growth and survival of lactic acid bacteria. Consequently, those studies examined the course of lactic acid fermentation, the development of physical properties, basic nutritional parameters, antioxidant properties, and sensory quality. The effect of the addition of mushrooms, in various forms, on the course of lactic acid fermentation and yogurt properties is described below.

4.2. The Course of Lactic Acid Fermentation and Prebiotic Properties

The key parameters indicating the desired course of the lactic acid fermentation process include acidity and pH. Due to the activity of lactic acid bacteria, lactic acid content increases, accompanied by a decrease in pH to 4.6. Most authors of yogurt studies have determined these parameters. In most cases, the addition of mushroom products significantly contributed to an increase in acidity and a decrease in the pH value, compared to the control yogurt (with no mushrooms added) [159,162,164,165,173,174,176,177,180,181,183,186,187,188,189]. Al Kaisy et al. [183], who added dried P. ostreatus powder to sheep milk-based yogurt, explained this by the presence of carbohydrates in mushrooms, which serve as an additional nutrient source for lactic acid bacteria. Similar correlations were observed following the addition of powders from A. bisporus, L. edodes, G. frondosa and L. hatsudake [159,172,173,174]. Pelaes Vital et al. [188] investigated the effect of adding P. ostreatus to low-fat yogurt and demonstrated that aqueous mushroom extracts shorten the incubation time required to reach a pH value of 4.6, as the extract compounds contribute to a faster rate of multiplication of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus. They identified dietary fibre, represented by indigestible carbohydrates such as chitin, α-glucans, xylans, mannans, and galactans, as the prebiotic compounds responsible for this effect. The positive effect of aqueous mushroom extracts on fermentation kinetics and the LAB count in yogurts was also demonstrated by Sakul et al. [186] and Dimitrova-Shumkovska et al. [177]. Tupamaho and Budiarso [180], who used an additive of P. ostreatus powder, demonstrated that an increase in its concentration (from 0.5% to 1.5%) was accompanied by a decrease in the pH value of yogurt and, at the same time, a significant increase in the count of lactic acid bacteria, which can be linked to the prebiotic properties of mushroom compounds. After 12 h of fermentation, yogurt with a 1.5% addition of mushroom powder contained 10.1 log CFU (colony-forming units) per mL of lactic acid bacteria, whereas the yogurt with no additive contained 9.77 log CFU/mL. A significant increase in the count of lactic acid bacteria in yogurt to 9.76 log CFU/mL was also caused by a 2% addition of dried G. lucidum solid residues remaining after industrial water extract production, although this did not change fermentation kinetics [171]. In turn, in a study by Atik et al. [168], the addition of both powder and aqueous extract from G. lucidum at concentrations of 1% and 2% caused a decrease in the count of the species of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus, but showed a prebiotic effect, contributing positively to the development of probiotic bacteria B. animalis subsp. lactis (Pro Lafti B-94) and L. acidophilus (Pro Lafti L10), which are added to yogurt. In samples with a 2% addition of powdered mushroom, the count of probiotic bacteria was above 7.5 log CFU/g. The definition developed by FAO/WHO indicates that the population of specific microorganisms used in the production of yogurts must remain alive, numerous and active and should be at least 107 CFU/g [9] until the last day of the shelf-life of these products.

The effects of prebiotics are also important during the storage of yogurts. According to Chou et al. [167], polysaccharides obtained from the stems of L. edodes, P. eryngii and F. velutipes, added in amounts ranging from 0.1% to 0.5%, act synergistically with peptides and amino acids from yogurt culture, thus increasing the survivability of L. acidophilus, L. casei and B. longum subsp. longum during low-temperature storage of yogurts, and maintaining probiotics at a level above 107 CFU/mL. According to Faraki et al. [164], prebiotic properties are determined by the concentration of mushroom extracts added to yogurts. Moreover, the preferences of individual lactic acid bacteria species may differ in this respect. The authors demonstrated that an A. auricula aqueous extract added at 0.05% showed a superior effect on the survival of B. bifidum Bb-12, and for L. acidophilus La-5, at a concentration of 0.1%.

Prebiotic properties of mushroom polysaccharides have been widely described [106,108,109,210], with particular emphasis placed on the properties of β-glucans [88,90,92,109,210]. Not only are prebiotics important from a technological perspective, e.g., in yogurt production, but, above all, they modulate the human intestinal microbiota, thereby significantly improving human health [109,211].

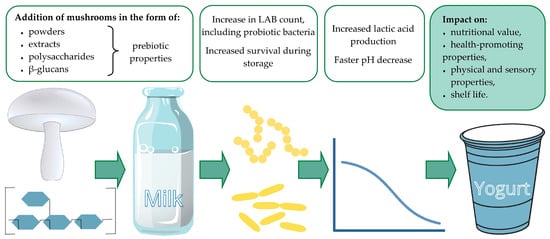

The constituents of mushroom powders and extracts, as well as isolated polysaccharides such as β-glucans, influence the growth and survival of lactic acid bacteria, thus enhancing the nutritional and health-promoting values of yogurt. Moreover, by increasing acidity and lowering pH, mushroom additives affect physical and sensory properties and the shelf life of the final product (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effect of mushroom additives on yogurt properties.

Nonetheless, introducing mushrooms has not consistently benefited the fermentation process. Several studies have not clearly established the effect of the addition of mushroom powder, polysaccharides or β-glucans on fermentation kinetics [166,169,175,178,179]. Heiba et al. [182,184] demonstrated that, with increasing addition of P. ostreatus powder to low-fat yogurt, its pH increased. Radzki et al. [189] explain this dissimilar effect by the difference in the amount of the additive applied, as they applied a higher concentration of the mushroom additive (3%). Another reason for this phenomenon could be that a study by Heiba et al. [182,184] used mushroom powders rather than polysaccharides, specifically β-glucans. This is because mushrooms contain various substances with antibacterial properties (Table 2), which, at higher concentrations, could inhibit the growth of lactic acid bacteria, and thus slow down the rate of fermentation. This was confirmed by a study that demonstrated a significant decrease in the contents of S. thermophilus, L. acidophilus, and B. bifidum in yogurts with increasing concentrations of the mushroom additive [184]. Moreover, although polysaccharides can serve as prebiotics, they also have antibacterial properties. A study by Türsen Uthan et al. [188], concerning the prebiotic potential of several species of edible and medicinal mushrooms towards L. plantarum, L. acidophilus and E. coli showed that maximum bacterial growth was achieved at a concentration of 0.25% of all mushroom polysaccharides, and higher concentrations of polysaccharides inhibited the proliferation of all strains of the bacteria under study.

4.3. Effect on Physical Properties

In accordance with Codex Alimentarius guidelines, yogurts, as well as other fermented dairy beverages, may be produced from whole milk, partially or completely skimmed milk, condensed milk or milk reconstituted from powder [9]. Consumers value low-fat yogurts due to the growing awareness of the health hazards associated with high-fat diets. However, fat plays an important role in yogurts, as it determines their texture. Low-fat yogurts are characterised by lower gel strength and firmness than full-fat yogurt, and are also perceived as being of lower quality by consumers [212]. To improve the quality of yogurts, plant fibre is added, which serves a stabilising function, increases water-holding capacity, prevents syneresis, and improves viscosity and gelling ability [213]. Plant fibres, such as β-glucan and inulin, also serve a prebiotic function [214]. A similar role can also be played by mushroom fibre.

4.3.1. Viscosity

Viscosity is an important quality parameter for yogurt, as it is closely linked to its stability and how consumers perceive it [187]. Most studies have shown that with an increase in mushroom additive, whether in the form of powdered dried P. ostreatus mushrooms [181,182,183,184] or in the form of an aqueous extract from P. ostreatus [185,187], powders and aqueous extracts from G. lucidum [168], as well as polysaccharides from A. cornea [165] and E. yadongensis [166], the viscosity values increased. This is particularly relevant for low-fat yogurts, which typically exhibit lower viscosity and a greater tendency toward syneresis [182]. The authors explained the increase in viscosity as a result of increased water-holding capacity, linked to the fibre content of the mushroom powder and its presence [168,181,182,183,184,192]. During the storage of the yogurt, a continuous increase in this parameter value was observed in both the control samples and those fortified with a mushroom additive. This was probably due to the continuous metabolic activity of lactic acid bacteria and a further decrease in pH, resulting in progressive coagulation of milk proteins [181]. In a study by Wang et al. [192], the viscosity of set yogurt was slightly enhanced after adding T. fuciformis polysaccharides during cold storage, primarily because the polysaccharides could interact with the opposite charges in proteins to form a stronger structure. However, when the applied mushroom additive was β-glucan, an increase in its concentration was accompanied by a decrease in yogurt viscosity. According to Pappa et al. [178], β-glucan was added in the form of a paste; therefore, as the percentage of β-glucan added to milk increased, the amount of water added also increased, which could have significantly contributed to the decrease in viscosity. In several cases, a decrease in viscosity, proportional to the increase in the concentration of the mushroom powder added and the yogurt storage duration, was observed [172,173,174]. Aleman et al. [172] explain this fact by disturbances in the gel network of the yogurt matrix caused by mushroom particles, resulting in decreased viscosity. Furthermore, the addition of mushroom powder accelerated the growth of starter cultures, which can cause breakdown of milk solids due to pH-related alterations in casein micelles, leading to reduced gel strength and yogurt viscosity.

4.3.2. Syneresis

Syneresis, or gel shrinkage, which leads to the separation of whey, is a defect in yogurts that primarily affects low-fat yogurts. The reason for this phenomenon is the loss of the yogurt gel’s ability to retain the entire serum phase during storage, due to the weakening of the gel network [188]. The occurrence of syneresis in yogurt is influenced by the pH, total acid content, and water-holding capacity [187]. Syneresis can be partially reduced by increasing the total dry matter content of milk, subjecting milk to intensive heat treatment, increasing homogenisation pressure, or adding stabilisers such as gelatin, pectin, starch, whey protein concentrate, and gums, which interact with the casein network [188].

The study yielded conflicting results regarding the effect of adding mushrooms in various forms on the occurrence of syneresis in yogurts during storage. The addition of powder from dried P. ostreatus and L. edodes at 1%, 2%, and 3% to yogurts significantly reduced syneresis as the amounts of the mushroom additives increased, compared to the control sample. The authors attributed this fact mainly to the presence of mushroom fibre and increased water capacity [174,182,184]. As reported by Pelaes Vital et al. [188], the addition of P. ostreatus aqueous extract at concentrations of 0.25%, 0.5%, 0.75%, and 1% also reduced, to a considerable extent, the occurrence of this defect in low-fat yogurt, with the best effect observed at a concentration of 1%. The aqueous extract used in the study contained, inter alia, phenolic compounds that, due to hydrophobic interactions, can form complexes with milk proteins. Additional hydrogen bonds strengthen the resulting polyphenol-casein complexes, potentially leading to reduced syneresis in fortified yogurts [215]. Sukul et al. [185,187] added P. ostreatus aqueous extract to whole-milk yogurts, but at higher concentrations of up to 8%. In this case, the authors noted a similar trend: as the concentration of the mushroom additive increased, syneresis decreased. The authors linked these stabilising properties to the β-glucan content of the extracts used, which has water-binding properties and improves the rheological properties of full-fat yogurt. Powders and aqueous extracts from G. lucidum, used in amounts of 1% and 2%, also showed beneficial effects by reducing syneresis in yogurts, with the reducing effect of the addition of mushroom extract on % syneresis being higher than that of the addition of powder [168]. Where the G. lucidum-based β-glucan preparation was used at concentrations of 0.5%, 1% and 1.5%, even better results were obtained. The syneresis of low-fat yogurt decreased with increasing concentration of the mushroom-derived additive, and no effect of storage duration was observed, which is extremely important. This was explained by a considerably higher concentration of total solids in fortified yogurts compared to the control, as well as by the presence of hydroxyl groups in the chemical structure of β-glucan, which can bind water through hydrogen bond interactions [169]. A similar syneresis-inhibiting effect during the storage of yogurts was exhibited by polysaccharides from E. yadongensis [166]. Literature data on β-glucans in dairy systems confirm that these compounds, by incorporating themselves into the casein network and forming polysaccharide clusters in the spaces between micelles, can lead to increased viscosity, reduced syneresis and enhanced gel stability, especially in reduced-fat yogurts [216,217,218].

In a study by Pappa et al. [178], increasing levels of β-glucan isolated from P. citrinopileatus did not decrease syneresis in low-fat yogurts. Furthermore, after two weeks of storage, the highest syneresis was noted for yogurt with the highest concentration of the additive (0.5%). Similarly, an increase in syneresis was observed when crude polysaccharides from A. bisporus, G. lucidum [162] and P. ostreatus [189], as well as an aqueous A. auricula extract [164] and L. hatsudake powder [173], were used as additives in yogurts. These studies showed that syneresis increased proportionally with the concentration of the mushroom additive, regardless of the starter culture used. Faraki et al. [164] suggest two possible reasons for the increased syneresis. The first option involves fungal origin proteases, which can coagulate milk casein and increase the amount of liquid released. The second cause of syneresis may be the activity of lactic acid bacteria, which can bring milk casein to its isoelectric point (pH), resulting in syneresis in yogurts. Rapid acidification leads to rapid protein aggregation, resulting in the formation of a small number of protein-protein bonds and of a weak gel with large pores and greater whey separation. According to Zhu et al. [173], the enzymatic activity of the starter culture can degrade the protein structure, reducing colloidal bonds and decreasing the size of milk protein aggregates, thereby hindering the retention of water molecules and leading to syneresis.

4.3.3. Texture Profile

Hardness, or firmness, is the most important characteristic in determining yogurt texture. Al Kaisy et al. [183] reported that, when fortifying sheep milk yogurts with P. ostreatus powder, the hardness of yogurt increased with increasing additive concentration (from 1% to 5%), due to the presence of mushroom compounds, namely proteins and polysaccharides. The hardness values also increased over 14 days of frozen storage, likely due to the slow loss of moisture from the open containers with the product. This increased the total solid content, resulting in higher hardness and viscosity. Moreover, Atik et al. [168], who added a G. lucidum aqueous extract and powder to yogurts, observed a similar trend of increasing yogurt hardness in proportion to the mushroom additive concentration (from 1% to 2%), with the effect of the powder additive being greater than that of the extract. Polysaccharides of fungal origin significantly increased the water-holding capacity and hardness of yogurt. A similar trend was observed by Wang et al. [165,192], who added polysaccharides from the T. fuciformis and A. cornea species. However, in the case of T. fuciformis, the hardness of yogurts decreased significantly during their storage. In contrast, studies by El Attar et al. [181] and Ghetran and Mulakhudair [159] show that adding mushroom powder increases yogurt hardness relative to the control, but only over a limited concentration range. In the case of P. ostreatus, both fresh and stored yogurt fortified with 0.1% of the powder exhibited the highest hardness and gumminess. With the addition of 0.2%, the hardness and gumminess decreased. In turn, the addition of A. bisporus increased the hardness of fresh yogurt when applied at concentrations of 0.5% and 5%. Intermediate concentrations did not increase yogurt hardness. Radzki et al. [189] demonstrated that increasing the concentration of crude polysaccharides to 0.4% significantly increased hardness, with no further changes observed at higher concentrations. The gumminess values in yogurts increased proportionally with the addition of polysaccharides across the entire concentration range (from 0.1% to 0.5%). This is consistent with the results of a study by Gustaw [219], who demonstrated that oat β-glucans concentrations above 0.1% resulted in a considerable decrease in yogurt hardness. According to Vanegas-Azuero and Gutiérrez [169], who added β-glucans from G. lucidum, the hardness of fortified yogurts was significantly higher than that of the control, regardless of the concentration applied (0.5–1.5%). No changes in the textural parameters of fortified yogurt samples were observed during frozen storage. The authors explain this fact by the specific structure of β-glucans, whose long chains can disrupt the formation of casein’s three-dimensional structure, leading to a weaker gel. Yogurts fortified with L. hatsudake and L. edodes powders during frozen storage also showed significantly lower hardness than that of control yogurts [173,174].

Cohesiveness is another important textural parameter of yogurt, representing the strength that integrates all the product’s ingredients. With increasing concentration, the addition of mushrooms, whether in the form of powders, extracts, or isolated β-glucans, decreased this parameter in most cases. A decrease in cohesiveness was also observed during frozen storage of yogurts [169,173,181]. The decrease in cohesiveness may result from the formation of gels with lower integrity and may be associated with increased syneresis [189]. An interesting correlation was demonstrated in studies by Al Kaisy et al. [183] and by Radzki et al. [189]. In this case, applying the highest concentrations of the mushroom additive (5% P. ostreatus powder and 0.5% P. ostreatus crude polysaccharides, respectively) inhibited the decrease in cohesiveness and even led to a slight increase. An opposite relationship was observed by Zhu et al. [174]. The authors demonstrated that yogurts containing 1% and 2% L. edodes powder showed higher cohesiveness than the control yogurt, but at a 3% addition, the parameter decreased significantly.

Springiness determines the ability of a sample to return to its original state after deformation. In studies by Al Kaisy et al. [183] and El Attar et al. [181], springiness decreased slightly with increasing mushroom additive concentration and storage time. The highest springiness was observed in the control yogurts. In turn, Pelaes Vital et al. [188] demonstrated that an increasing concentration of an aqueous P. ostreatus extract in low-fat yogurts corresponds to an increase in springiness. The authors explained this by the gel’s higher water content, which makes it softer and less fragile. The addition of mycelia from M. esculanta also contributed to a significant increase in springiness, as compared to the control yogurt [176].

It should be noted that the textural properties of yogurt are determined by numerous complex factors, not only its composition but also the technological process (e.g., temperature and incubation time) and the type of starter culture used, as all these factors affect the gel network structure [220].

4.3.4. Microstructure

The microstructure of yogurts was observed using scanning electron microscopy [191,192] and fluorescence microscopy [185]. The studies demonstrated that the addition of mushrooms in the form of an aqueous P. ostreatus extract [185] and polysaccharides isolated from T. fuciformis [192] contributed to the formation of a compact, dense yogurt microstructure, enhancing physicochemical properties and stability. The authors explain this through the action of mushroom polysaccharides, which affect the protein matrix and lead to the formation of a compact yogurt gel. Microstructure studies were also conducted on yogurts containing fruit pulp fermented by T. versicolor [191]. In this case, a clear influence of mushrooms on the structure of yogurt was also observed. Products with the addition of fruit pulp fermented by mushrooms were characterised by considerably smaller pores and greater structural compactness, as compared to yogurt with unfermented fruit pulp added. According to the authors, the improvement in the structure, as in previously cited studies, results from the presence of mushroom polysaccharides. These polysaccharides function by physically occupying interstitial spaces within the protein matrix and chemically crosslinking casein micelles, thereby creating a more compact and stable protein-polysaccharide complex network.

4.3.5. Colour Parameters

Mushroom additives may also affect the colour of yogurts. Several studies have reported instrumental colour measurements of yogurts fortified with mushrooms using the CIE colour scale, assessing the following basic parameters: L*, a*, and b*. L* is the lightness component, which ranges from 0 to 100; parameters a* (from green to red) and b* (from blue to yellow) are the two chromatic components, which range from −120 to 120 [221]. According to El Attar [181], the addition of P. ostreatus powder, even at a maximum concentration of 0.2%, did not significantly affect the colour parameters of fresh fortified yogurts. Only the L* parameter value was slightly reduced compared to the control sample. However, during cold storage, the b* parameter increased, possibly due to the gradual decrease in yogurt moisture content. Pelaes Vital et al. [188], who used an aqueous extract of P. ostreatus as an additive, demonstrated a significant change in the colour of the fortified yogurts. It was found that low-fat yogurt containing an over 0.5% mushroom extract was yellower, redder, and darker than the control, which was attributed to the dark colour of the mushroom extract. A significant effect of L. hatsudake and L. edodes mushroom powder on the colour of yogurts was demonstrated by Zhu et al. [173,174]. With increasing concentration, the additive decreased the L* parameter and increased the a* and b* parameters. A similarly significant change in the colour of yogurts fortified with powder and aqueous extract from G. lucidum was observed by Atik et al. [168], with the effect of the powder additive being more statistically significant than that of the extract additive. The authors demonstrated that fortified yogurts showed a significantly lower L* parameter value than the control. The darkening of the product could be due to both the mushroom’s dark colour and the increase in phenolic compound content, depending on the concentration of the added powder and extract. The addition of mushroom powder or extract resulted in an increase in the a* parameter value, a change in colour from green to red, and a decrease in the b* parameter value.

4.4. Impact on the Chemical Composition

Mushroom additives incorporate a number of ingredients into dairy products, e.g., vitamins, minerals, fibre, antioxidant compounds, and various biologically active substances. Particularly important are phenolic compounds and β-glucans, which, when incorporated into the yogurt matrix, can interact with numerous components (including milk proteins and fat). These interactions are of crucial importance for both the stability of bioactive compounds and their bioavailability. According to El Attar [181], the addition of mushrooms rich in nutrients and health-promoting compounds to a product as popular as yogurt can effectively prevent diseases associated with nutritional deficiencies.

4.4.1. Proximate Analysis

In most studies, the addition of mushrooms significantly increased the basic nutritional value parameters, including the protein, carbohydrate and fibre contents of yogurts. The total solid content also increased, while the product’s moisture content decreased. These studies usually used mushroom powder, naturally rich in carbohydrates, fibre and protein, as an additive [159,179,181,182,183,184]. A decrease in protein content was observed only by Pappa et al. [178], who used β-glucans isolated from P. ostreatus as an additive. However, Sakul et al. [187], who also used β-glucans from P. ostreatus, and Vanegas-Azuero and Gutiérrez [169], who used a commercial β-glucan preparation from G. lucidum, showed an increase in protein content proportional to the amount of added β-glucan. The commercial preparation used consisted mainly of carbohydrates (93.5%) and contained 2% protein. An increase in protein content has also been observed during frozen storage of yogurts, both in mushroom-fortified and control samples [159,182,183,184]. The apparent increase in protein content can be explained by proteolytic enzymes in starter cultures breaking down protein, releasing free amino acids and peptides. This may alter the form of protein and increase the amount of free nitrogen, which, in some analyses, may be interpreted as an increase in protein content [222].

Most studies have found no significant effect of fortifying yogurts with mushrooms on the fat content [159,163,178,179,181,182,184], regardless of the form of the additive. Mushrooms contain small amounts of fat and, therefore, have no significant effect on the development of this parameter in yogurts. An increase in the content of this component in yogurts has only been demonstrated in a study by Vanegas-Azuero and Gutiérrez [169]. In addition to the mushroom additive in the form of β-glucans from G. lucidum, the authors also added sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis) seeds to the yogurts, which may explain the results. In a study by Al Kaisy et al. [183], yogurts fortified with P. ostreatus powder contained significantly less fat than the control yogurt. However, the fat content increased in all yogurts as storage progressed. The authors explained this by a decrease in moisture content, which increases the total solids content, including fat.

4.4.2. Amino Acids

El Attar et al. [181] examined the amino acid content of yogurts. The addition of P. ostreatus powder increased the content of most amino acids in fresh yogurts. In most cases, the greatest increase was observed in samples containing the highest addition of mushroom powder (0.2%), including aspartic and glutamic acids, serine, arginine, threonine, methionine, isoleucine, and leucine. After 14 days of storage, all samples containing mushroom powder had a higher percentage of glutamic acid than at time zero. The authors report that the hydrolysis of most proteins and the increase in free amino acid content of yogurts are mainly attributable to L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. Free amino acids stimulate the activity of streptococci and enable the formation of compounds responsible for the characteristic aroma of yogurt. In turn, the observed decrease in amino acids is mainly due to their utilisation by S. thermophilus.

Liu et al. [191] added to yogurts R. roxburghii and S. grosvenorii juice in an unprocessed form and in a form subjected to fermentation involving T. versicolor. Yogurt with the addition of a fermented juice contained more free amino acids than that with the addition of an unprocessed juice. Fresh yogurts containing fermented juice contained higher levels of arginine, glutamic acid, leucine, and proline, confirming the proteolytic activity of T. versicolor. Yogurt with fermented juice added retained small amounts of leucine, histidine, and lysine, whereas no such compounds were detected in yogurt with unprocessed juice. In both variants, yogurt fermentation contributed to a decrease in the contents of serine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, leucine, valine and threonine, probably due to their catabolism into α-keto acids, and subsequent conversion to flavour-active compounds. The study showed that fungal fermentation modulates both the nutritional and flavour characteristics of fermented dairy products.

4.4.3. Fatty Acids

The fatty acid profile is an important indicator of qualitative changes during yogurt storage. Corrêa et al. [163], who fortified yogurt with an extract from commercial A. bisporus waste, rich in ergosterol, found that both fresh control and fortified yogurts had a similar fatty acid profile. In all samples, the predominant fatty acids were palmitic acid (C16:0), followed by oleic acid (C18:1n9) and myristic acid (C14:0). The control yogurt contained significantly more PUFAs than yogurt with a mushroom extract added. After seven days of frozen storage, fortified yogurts showed a significant increase in the proportion of butyric acid (C4:0) and a decrease in linoleic acid (C18:2n6), compared to the control sample. A similar fatty acid profile, with a predominance of palmitic, oleic, and myristic acids, was found in yogurts fortified with free and encapsulated extracts from A. bisporus [161]. The study showed that the form of the mushroom additive significantly affects the fatty acid profile, except for oleic acid, SFAs, and MUFAs. In yogurt with thermally untreated microspheres containing extract samples, greater amounts of lauric acid (C12:0) and myristic acid were noted. In the control yogurt, the highest oleic acid and MUFA contents, along with the lowest SFA content, were noted. A seven-day frozen storage period contributed to a decrease in the oleic acid and linoleic acid contents. The fatty acid profile was also analysed in a study by Vanegas-Azuero and Gutiérrez [169]. However, in this case, the results of the study were primarily influenced by the addition of P. volubilis seeds to yogurt, rather than by a mushroom additive in the form of β-glucans from G. lucidum.

4.4.4. Vitamins and Minerals

Mushrooms can be added to yogurt to increase its vitamin content. El Attar et al. [181] examined the contents of vitamins C and E, as well as B group vitamins (B2, B3, B6, B9, B12) in yogurts fortified with P. ostreatus powder. Fresh control yogurt contained no vitamins E or B3. The addition of mushroom powder increased the levels of all vitamins, except B3. Regarding vitamin C, the greatest (8-fold) increase was observed at a mushroom powder concentration of 0.1%; in other cases, the best results were achieved with the maximum addition (0.2%). The highest vitamin levels in samples of fresh yogurt containing mushrooms were observed for vitamin C (537 mg/kg DW), B9 (475 mg/kg DW), and B6 (221 mg/kg DW). The greatest increase in the content after fortification was noted for vitamin B12 (more than 57-fold) and B9 (more than 30-fold). After a 15-day frozen storage period, a decrease in the vitamin content was observed in most cases. The exceptions included vitamins B2 and B12, whose levels increased slightly. Vitamin B3 was detected in yogurts containing added mushrooms. The authors explained the decrease in vitamin content as due to factors such as oxygen, light, heat, alkali, trace minerals, and hydroperoxides. Increasing the content of vitamins C and E, which have antioxidant properties, is particularly important for maintaining yogurt quality during storage.

The same authors also examined the effect of P. ostreatus powder on the macro- and micronutrient contents in yogurts. The addition of mushrooms increased the levels of all micronutrients (Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn) and macronutrients (Ca, Mg, K, Na, P) tested in fresh yogurts compared to the control, although this increase did not always correlate with the mushroom powder concentration. No such relationships were noted for yogurts frozen stored for 15 days. As far as the micronutrients are concerned, Zn and Fe were found in the highest amounts in all yogurt samples, while Ca and K were the most abundant macronutrients. The addition of mushroom powder resulted in a threefold increase in the calcium content in yogurts, compared to the control sample [181].

A study by Atik et al. [168] on the effect of adding powder and aqueous extract from G. lucidum on the functional, textural, and sensory qualities of yogurt also analysed mineral content. However, only mushroom powder and mushroom extract were tested, whereas yogurts were not. The authors report that the mineral content of the powder was higher than that in the extract, with potassium being the most abundant mineral.

4.5. Phenolic Compound Content and Antioxidant Properties

The introduction of a mushroom additive to yogurts in the form of powder [168,173,174,182,184] or an aqueous extract [168,177] contributed to an increase in the phenolic compound content regardless of the mushroom species. The studies conducted in this area show that powders and aqueous extracts significantly affected the total phenolic content in yogurts, depending on the concentration used. Certain levels of phenolic compounds were also observed in control yogurt samples due to the analytical method used, which measured phenolics with the Folin–Ciocâlteu reagent. The minimal level of phenolic compounds in the control yogurt samples can be attributed to the presence of glucose derived from the breakdown of milk lactose and amino acids containing phenolic side chains. These compounds react with the reagent, yielding a false-positive measurement result [173]. As demonstrated by Atik et al. [168], the use of 1% and 2% aqueous extracts from G. lucidum resulted in a greater increase in the phenolic compound content of yogurts compared to using the same concentrations of freeze-dried powder. The highest phenolic compound content was observed in fresh yogurts containing 3% P. ostreatus powder (160.12 mg/100 g) [182].