Abstract

The meandering river reservoirs of the Ng3–Ng4 members of the upper Guantao Formation in northern Middle Block 2, Gudao Oilfield, exhibit sand bodies with rapid lateral variation, complex contacts, and strong heterogeneity. Previous characterization using sparse well patterns showed deviations in depicting sand body boundaries and internal architecture with insufficient accuracy for optimizing development plans and tapping remaining oil. Additionally, small-scale lateral accretion mud interlayers within point bars—which are hard to trace between wells—limited fine characterization of point bar architecture. Using the high-resolution data and dense inter-well control of the study area’s dense well pattern, we traced 3–10 cm thick lateral accretion mud interlayers within point bars between wells, overcoming the challenge of characterizing thin interlayers with sparse well patterns, and dissected reservoir architecture. Results indicate the study area is dominated by meandering river deposits, with four architectural units: channels, abandoned channels, overbanks, and flood plains. Meander belts range in width from 450 to 1900 m with an average of 1420 m; point bars measure in length from 310.6 to 1754 m with an average of 1036.2 m and in width from 323.4 to 1586 m with an average of 1000.8 m. Lateral accretion mud interlayers show sub-oblique profiles, with dips of 3–6° and a thickness of 3–10 cm; individual lateral accretion bodies are 1.5–5.7 m thick and 32–255 m wide horizontally. Based on channel-point bar scale relationships, an empirical formula for quantitative characterization was established, enabling the prediction of single sand body scales in sparsely well-patterned areas to support well placement and remaining oil prediction. Combined with contact relationships of sand bodies across architectural hierarchies, the main architectural models of composite meander belts were developed. This study provides a reliable geological basis for dissecting meandering river reservoir architecture and tapping remaining oil under sparse well patterns.

1. Introduction

Reservoir heterogeneity refers to the spatial variation characteristics of lithology, electrical properties, physical properties, oil-bearing property, and microscopic pore structure within oil and gas reservoirs [1]. Research in this field began in the 1980s and has now become a core component of fine reservoir characterization. Currently, scholars worldwide mainly adopt research methods of “evolution from qualitative to quantitative analysis, multi-technology integration, and interdisciplinary combination” to conduct systematic studies on reservoir heterogeneity. Reservoir heterogeneity is controlled by multiple factors such as sedimentation, diagenesis, and tectonism [2]. Among them, factors including base-level changes, paleotopographic slope, hydrodynamic intensity and direction, provenance supply, and sedimentary microfacies lead to differences in sediment grain size, bedding structure, sand body thickness, geometric shape, superposition pattern, and connectivity, thereby forming reservoir heterogeneity [3]; diagenesis also has a significant impact on reservoir heterogeneity characteristics [3,4]. For example, compaction, cementation, and recrystallization can significantly alter the original physical properties of sand bodies and intensify the degree of reservoir heterogeneity [5,6].

Reservoir architecture refers to the scale, shape, occurrence, and mutual superposition relationship of different hierarchical architectural units within reservoirs [7]. This concept was first proposed by Allen at the 1st International Conference on Fluvial Sedimentology in 1977. In 1985, Miall [8] further clarified the definition of fluvial reservoir architecture and proposed corresponding analytical methods. In 1986, Chinese scholar Ke Baojia [9] first introduced the concept of reservoir architecture into China. Domestic research in this field started relatively late, mostly based on Allen’s research results, focusing on fluvial and deltaic reservoirs. In the 1990s, reservoir architecture research entered a stage of rapid development, with a large number of relevant achievements published by scholars worldwide. In 1991, Baker [10] took the lead in applying ground-penetrating radar technology to reservoir architecture research; in the same year, Xue Peihua summarized the point bar architecture model and proposed the concept of “lateral accretion body”. In 1992, Zhang Changmin [11] put forward the hierarchical analysis method for architecture. Early understanding of underground geological structures mainly relied on outcrop and modern sedimentary studies, which have the advantages of easy accessibility and detailed description. In 1996, Miall [12] systematically proposed an architectural classification scheme including 9 levels of interfaces, 9 types of architectural elements, and 20 lithofacies. In 2000, Posamentier et al. [13] applied seismic geomorphology methods to reservoir architecture research, and since then, methods such as numerical simulation [14] and flume experiment [15] have also been widely used. In 2005, Weber et al. [16] first incorporated diagenesis into the scope of architectural research and proposed the “diagenetic architecture concept”. In 2008, Wu Shenghe [17] put forward the research idea of “hierarchical analysis, pattern fitting, and multi-dimensional interaction”. In 2010, Backert et al. [18] introduced aeromagnetic data into architectural analysis. In 2013, Wu Shenghe et al. [19] proposed a 12-level architectural interface classification scheme; in 2014, Hu Guangyi et al. [20] further proposed the concept of “composite sand body architecture”. At present, reservoir architecture research has entered a relatively mature stage.

Meandering river deposits are widely developed in continental sedimentary basins in China and serve as important oil and gas reservoirs [21,22]. Among them, meandering river reservoirs are usually far from provenance with gentle slopes, characterized by fine grain size, good sorting, and “high porosity and high permeability” [23], making them favorable oil and gas-bearing sand bodies. However, due to frequent channel migration, sand bodies have poor continuity, showing characteristics of “segmental continuity” and “local disconnection” [24], resulting in poor reservoir connectivity and significant heterogeneity.

The architectural element analysis method proposed by Miall [12] has laid a foundation for the fine dissection of fluvial reservoir architecture and promoted the rapid development of meandering river reservoir research. Currently, scholars at home and abroad have achieved fruitful results in the field of meandering river reservoir architecture. Luo Heyuan [25], Li Bing’e [26], and others have conducted quantitative characterization of meandering river reservoir architecture based on high-resolution seismic data; Bridge [27], Marinus [28], Qiao Hui [29], and others have systematically explained the meandering river sedimentary architecture patterns through field outcrop observation and modern sedimentary investigation, greatly enriching the research results of meandering river reservoirs. However, existing research still faces obvious bottlenecks: although high-resolution seismic data can characterize macro-architecture, it is limited by resolution and difficult to finely depict microstructures such as thin-bedded sand bodies and lateral accretion interbeds, making it impossible to accurately identify channel superposition relationships and single sand body boundaries, thereby restricting the accurate evaluation of reservoir seepage laws; although field outcrops and modern sediments can provide intuitive references for sedimentary models, they cannot reflect the actual distribution laws of underground sand bodies. Current research on meandering river reservoir architecture has the problems of “sufficient macro-characterization but insufficient micro-description, and predominant surface analogy with low consistency with underground reality”. There is an urgent need to rely on high-resolution data to achieve fine dissection at the single sand body level.

The study area, Gudao Oilfield, is located in the eastern part of Zhanhua Sag, Bohai Bay Basin, and is a typical meandering river sandstone oilfield. Members Ng3~Ng4 of the Upper Guantao Formation are the target strata of this study. The block faces problems such as high comprehensive water cut and low recovery factor during development [30,31,32]. However, the well pattern density of 180 wells/km2 (average well spacing of 85 m) in the study area can provide high-resolution lithological and physical property data, laying a foundation for fine dissection. Based on this, this paper adopts the hierarchical analysis method to conduct three-level architectural dissection (meander belt, point bar, and internal point bar) of the reservoir, clarifies the distribution and internal structure of sand bodies at different levels, counts core parameters such as single sand body thickness and lateral accretion layer dip angle, and establishes a quantitative characterization method of “hierarchical characterization-parameter statistics-pattern fitting”, providing a scientific basis for the optimization of oil and gas development plans and remaining oil tapping in the block.

2. Overview of the Study Area

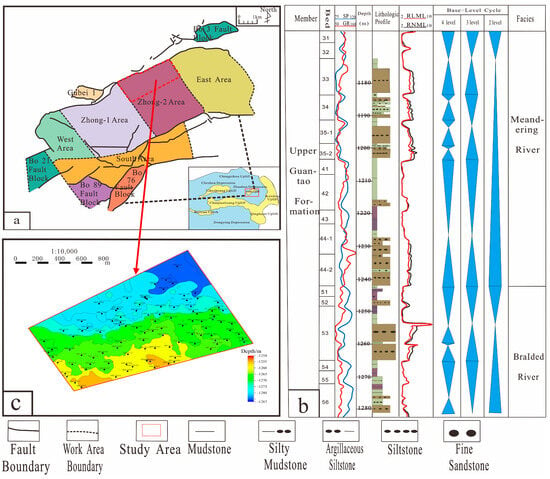

The Gudao Oilfield is located at the eastern junction of the Jiyang Depression and Zhanhua Depression in the southeastern part of the Bohai Bay Basin, structurally belonging to the core and pericline area of the Gudao Buried Hill Structural Belt and administratively falling under the Hekou District of Dongying City, Shandong Province, with the delta front of the Yellow River Estuary to its south, the Bohai Sea to its east, and the Chengdao Oilfield across the sea to its north; in terms of regional tectonic setting, the formation and evolution of the oilfield are controlled by the “multi-stage extensional-strike-slip superposition” tectonic dynamic environment of the Bohai Bay Basin, which is closely related to the lithospheric extension induced by the destruction of the North China Craton and the far-field effects of the Pacific Plate subduction, and as an important structural separation unit between the Jiyang Depression and Zhanhua Depression, the Gudao Buried Hill Structural Belt has a basement composed of Precambrian metamorphic rocks, with differential uplift occurring under the influence of NE-trending major fault activities during the Paleogene rifting period and draping sedimentation received over the buried hill in the Neogene depression period, eventually forming a large-scale NE-SW trending draped anticline with a “flat top and gentle flanks” structural morphology [33,34]; the study area is situated in the northern part of the Middle Second Block of the Gudao Oilfield, specifically on the northern flank of the Gudao Draped Anticline and adjacent to the No. 1 boundary major fault to the north, whose main active period was from the Paleogene Shahejie Formation to Dongying Formation deposition, and its activity has weakened since the Neogene but still controls the local structural morphology, while the internal structure of the study area is relatively simple, with an intact and gentle main structure, no secondary faults developed, and obvious zonation in stratum dip angle—only 30′~1°30′ at the anticline top and gradually increasing to 2~3° at the flanks—and the overall topographic relief is high in the southwest and low in the northeast, with strata gently dipping northeastward at a stable angle of 1~2°; in terms of regional stratigraphic sequence, the Gudao Oilfield develops Precambrian basement metamorphic rocks, Paleogene System, Neogene System, and Quaternary System from bottom to top, among which the Paleogene and Neogene Systems are the main oil-bearing strata, the main development horizon in the study area is the Upper Member of the Neogene Guantao Formation (a fluvial facies sandstone-mudstone assemblage that can be subdivided into 17 sublayers (Figure 1) with generally good sandbody connectivity), and the target interval focused on in this paper is the 3rd~4th sandstone members of the Guantao Formation, dominated by meandering river sedimentary facies; since its commissioning in 2005, the block has undergone 14 optimization adjustments, with the current comprehensive water cut reaching as high as 87.2%, and constrained by the internal structural heterogeneity of the reservoir, the block faces problems such as severe water flooding, unclear remaining oil distribution, and increasingly prominent injection-production contradictions, making it urgent to carry out detailed reservoir anatomy, further characterize the reservoir heterogeneity, and reveal the influence of reservoir architecture on oil and gas development.

Figure 1.

Tectonic Location of Gudao Oilfield and Comprehensive Stratigraphic Columnar Section of Upper Guantao Formation. (a) Structural Map of Gudao Oilfield; (b) Comprehensive Stratigraphic Column of the Upper Guantao Formation; (c) Well Location Map of the Study Area.

3. Date Analysis

3.1. Microfacies Identification

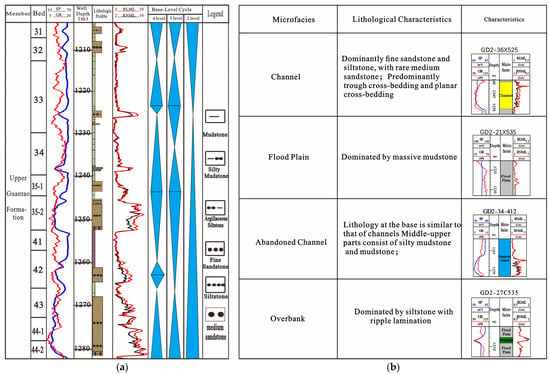

Previous studies have suggested that meandering river deposits are developed in sand members Ng3~Ng4 of the Upper Guantao Formation in Gudao Oilfield [30,32]. Based on a comprehensive summary of previous research results, this paper has identified multiple indicators, including rock composition, structural characteristics, sedimentary structures, vertical sequences, and logging response characteristics, to further analyze the types and features of architectural units in the study area. Taking Well GD2-34-422 as an example, its lithological profile has a low “sand-shale ratio” vertically, with a significant cumulative thickness proportion of mudstone. The lower sublayers of sand members Ng3 and Ng4 develop thick-bedded massive yellow and yellowish-green medium-fine sandstone, while the middle and upper parts are dominated by thick-bedded massive grayish-green and purple-red mudstone, which forms frequent interbedding with sandstone. It presents the positive cyclic sedimentary characteristics of “sand enclosed in mud”, a typical meandering river sedimentary feature (Figure 2a). Based on this, with sandstone thickness as the main criterion and combined with a comprehensive analysis of logging response characteristics, the division and identification of architectural units for all well intervals in the study area were further completed. Finally, the study area was classified into four types of architectural units: channel sand bodies, abandoned channels, flood plains, and overbank sand bodies.

Figure 2.

Comprehensive Lithostratigraphic Columnar Section and Sedimentary Microfacies Characteristics of Upper Guantao Formation of Well GD2-34-422 in Gudao Oilfield. (a) Comprehensive Lithostratigraphic Columnar Section of Upper Guantao Formation of Well GD2-34-422; (b) Characteristics of Sedimentary Microfacies.

3.1.1. Channel Sand Bodies

The channel sand bodies of meandering rivers are dominated by point bar deposits. Their formation results from the frequent lateral migration and oscillation of channels, leading to the lateral connection of multiple single-point bar units that collectively form composite channel sand belts. The channel sand bodies in the study area have large sedimentary thickness, ranging from 3 to 14 m. Lithologically, they are dominated by fine sandstone and siltstone, with a small amount of medium sandstone, and exhibit typical positive rhythmic structures, with grain size gradually fining from bottom to top. Trough cross-bedding and tabular cross-bedding are the most developed. The logging curves show that spontaneous potential (SP) and natural gamma (GR) present box-shaped, bell-shaped, or their composite forms, with a large single-layer thickness of sand bodies and strong sedimentary energy (Figure 2b).

3.1.2. Flood Plains

The flood plain is formed when the river water level rises continuously during the flood period, and the fine-grained sediments carried by the water body overflow the river channel and are deposited in interchannel depressions. This microfacies is dominated by massive mudstone. The spontaneous potential (SP) curve is close to the mudstone baseline and straight in shape, while the natural gamma (GR) curve shows a medium-high value, serrated shape, reflecting the characteristics of high shale content and fine-grained lithology (Figure 2b).

3.1.3. Abandoned Channels

During the evolution of meandering rivers, the channel sinuosity continuously increases, eventually leading to neck cutoff. The original channel is abandoned and gradually filled, forming abandoned channel deposits. Its bottom lithology is similar to that of the channel, while the grain size of the middle and upper parts gradually fines, with increasing shale content. The sand body thickness ranges from 0.5 to 4 m. The spontaneous potential (SP) curve gradually decreases from medium-high amplitude to close to the mudstone baseline, reflecting the process of weakening water energy and decreasing sediment supply (Figure 2b).

3.1.4. Overbank Sand Bodies

Overbank sand bodies are mainly formed during flooding events. When there is a sudden increase in river discharge, the water level rises and overflows to the outside of the channel, and suspended materials undergo rapid accumulation to form overbank sand bodies. Lithologically, they are dominated by ripple-bedded siltstone. In terms of logging response, the natural gamma (GR) curve is mostly funnel-shaped or finger-shaped, the spontaneous potential (SP) curve shows a low-amplitude serrated-finger shape, and the microelectrode curves present low-amplitude serrations. The thickness of sand bodies is usually less than 3 m. Such deposits mainly include secondary units such as natural levees, crevasse splays, and floodplains (Figure 2b).

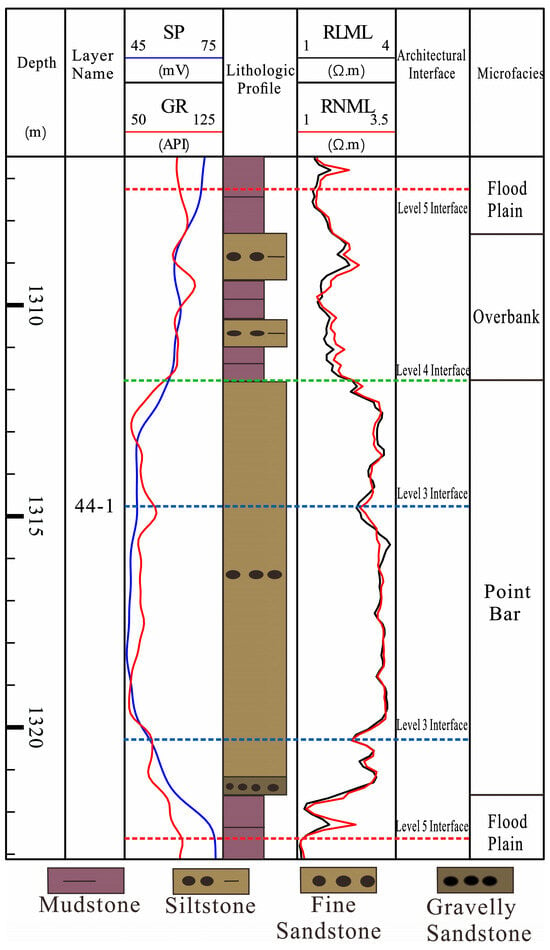

3.2. Architectural Hierarchy Identification

To accurately characterize the internal structure and fluid flow laws of fluvial reservoirs in the study area, this paper identifies 3rd~5th order architectural interfaces by analyzing lithofacies associations and logging responses of typical wells in the area, based on Miall’s fluvial architectural hierarchy theory [12]. A single meander belt is a 5th order architectural unit, whose architectural interfaces are the top and bottom boundaries of channel deposits; microfacies such as point bars and abandoned channels are bounded by 4th order interfaces, which serve as the dividing boundaries between bar-type architectural units and other architectural units; individual lateral accretion bodies within point bars are 3rd order architectural units, referring to single accretionary bodies [35,36].

Taking a typical well in the single layer Ng44-1 as an example, the flood plain mudstone at the 5th order architectural interface is dominated by purple-red massive mudstone, with spontaneous potential (SP) mostly showing serrated or linear shapes; the bottom of the interface is a channel scour surface, and the lithology abruptly changes downward to flood plain mud, with micro-potential and microelectrode curves presenting “abrupt contact”; the 4th order architectural interface is the dividing boundary between point bar sand bodies and upper overbank deposits, with SP usually showing obvious regression, natural gamma (GR) presenting medium-high values, small amplitude differences in micro-potential and microelectrode curves, and lithology dominated by massive-bedded mudstone and ripple-bedded siltstone; the 3rd order architectural interface corresponds to individual lateral accretion layers within point bar sand bodies, and its logging curves show varying degrees of regression (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Cross-Section of Type Classification of Different Levels of Architectural Interfaces in Typical Wells of the Study Area.

4. Methods

4.1. Single Meander Belt Sand Body Analysis

During the deposition of meandering rivers in the study area, due to seasonal changes in hydrodynamic force, multi-stage channel sand bodies cut and superimpose vertically to form “quasi-connected sand bodies”, while multiple single meander belt sand bodies splice laterally to form “sheet-like sand bodies” horizontally. This makes it difficult to identify the boundaries of single meander belts, resulting in complex spatial superposition relationships and strong heterogeneity of sandstone reservoirs.

Based mainly on logging data, this paper adopts the method of “vertical staging and lateral demarcation”. First, vertical staging is carried out through sedimentary discontinuities to identify sedimentary bodies of different stages. Then, according to the meandering river sedimentary model, combined with the results of architectural unit division and interwell correlation, a comprehensive analysis of single meander belts is conducted. When identifying single meander belts, their boundaries are determined based on interchannel deposits, elevation differences, abandoned channel filling, and thickness variation characteristics.

4.1.1. Vertical Staging

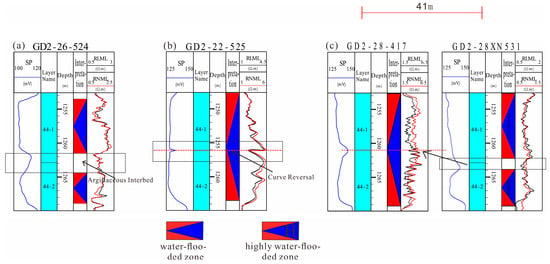

In the early stage of the Upper Guantao Formation, meandering river deposits dominated. Driven by sustained base-level fall, the channel development scale showed an expanding trend, with continuous channel incision and superposition. As a result, the vertical superposition relationship of channel sand bodies in the Ng44 sublayer is more complex than that in other sand layers. Therefore, taking the Ng44 sublayer as an example, this paper conducts fine division of vertical architectural units in the Ng44 sublayer based mainly on high-resolution logging data, comprehensively using methods including mudstone interbeds, logging curve regression, and adjacent well correlation constraint.

(1) Argillaceous Interbed. The meandering rivers in the study area exhibit typical “sand enclosed in mud” profile characteristics, effectively separating such channels vertically by fine-grained sediments such as mudstone and silty mudstone. The thickness of mudstone barriers ranges from 0.8 to 7 m. The spontaneous potential (SP) curve mostly presents independent box-shaped or bell-shaped forms with moderate amplitude, reflecting the complete sedimentary sequence of a single channel unit.

(2) Logging curve regression. When the channel hydrodynamic force is strong, it has a certain incision capacity but fails to completely erode the previously deposited fine-grained sediments. This is manifested as obvious regression characteristics on log-ging curves. As shown in Figure 4b, the SP curve of Well GD2-22-525 shows different amplitude differences with distinct stepped characteristics, and obvious regression also appears in the micro-potential and microelectrode curves.

Figure 4.

Three Vertical Staging Methods of Upper Guantao Formation in the North of Zhong-2 Area, Gudao Oilfield. Argillaceous Interbed. (a) Shaly interlayer. (b) Curve Reversal. (c) Adjacent Well Correlation Constraint.

(3) Adjacent well correlation constraint. In superimposed sandstones, some wells face great difficulty in identifying internal interfaces due to poorly developed mudstone interbeds and insignificant logging curve responses. In this case, the method of adjacent well correlation constraint can be adopted: taking the clear marker beds of adjacent wells as references, combined with stratigraphic continuity characteristics, to inversely infer the sedimentary discontinuities of the target well.

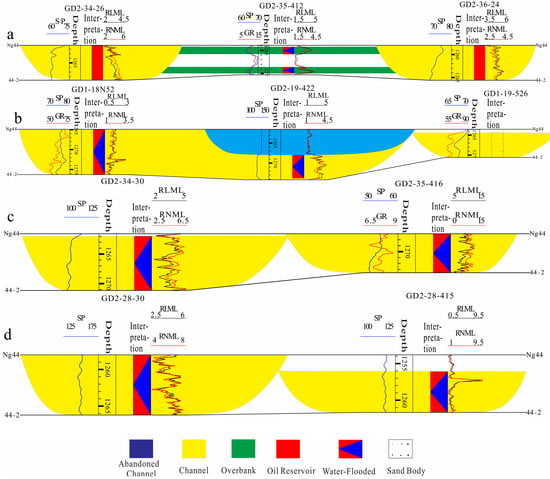

4.1.2. Lateral Demarcation

(1) Sedimentary facies change. When two stages of channels undergo lateral migration and horizontal convergence, discontinuous fine-grained sediments develop at the edges or bifurcations of their sand bodies, specifically manifested as overbank deposits and flood plain deposits. For example, both Well GD2-34-26 and Well GD2-36-24 drilled into channel sand bodies, but the two channels are separated by overbank deposits encountered by Well GD2-35-412, indicating that Well GD2-34-26 and Well GD2-36-24 drilled into different channel sand bodies (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Identification Marks of Meandering Belt Boundary. (a) Interchannel deposits; (b) Abandoned channel filling; (c) Differences in sand body thickness; (d) Differences in sand body top elevation.

(2) Abandoned channel filling. Abandoned channels are reliable indicators of the development scale of point bars. During the evolution process of a single fluvial system, channel migration and avulsion occur universally, and the abandoned channels formed by their final evolution mark the termination of sedimentation of the single channel (Figure 5b).

(3) Differences in sand body thickness. Differences in the duration of channel activity or hydrodynamic conditions during their formation lead to inconsistent thickness of deposited sand bodies. For example, the sand body thicknesses encountered by Well GD2-34-30 and Well GD2-35-416 are significantly different, thus serving as a marker for identifying the boundaries of single meander belts (Figure 5c).

(4) Differences in sand body top elevation. For the two stages of channels, differences in their sedimentation time and paleotopographic conditions result in inconsistent channel top elevations. When significant top elevation differences are observed between channels, these channels should belong to different sedimentary stages. For example, the channel sand bodies encountered by Well GD2-28-30 and Well GD2-28-415 have obvious elevation differences, thus confirming that the two wells drilled into channel sand bodies of different stages (Figure 5d).

4.2. Individual Point Bar Sand Body Analysis

Point bars are typical representative units of the 4th-order interface in Miall’s fluvial architectural hierarchy theory, and the most sand-rich sedimentary units in meandering river systems. Their reservoir performance is significantly controlled by the spatial superposition pattern, contact relationship, and distribution scale of lateral accretion bodies and lateral accretion interbeds. To conduct point bar identification based on underground drilling data, this paper identifies point bars according to their vertical sequence characteristics, sand body thickness, and close association with abandoned channel deposits.

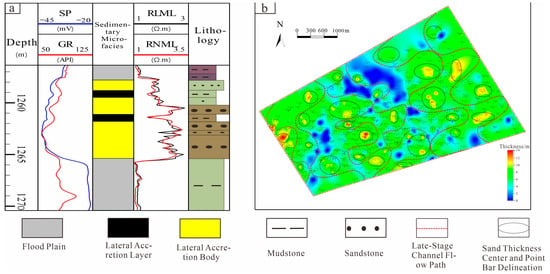

(1) Vertically, point bar sand bodies are mainly characterized by a positive grain size rhythm: grain size gradually decreases from bottom to top, and the scale of sedimentary structures also shrinks accordingly, collectively forming a typical “binary structure”. Vertical properties are clearly reflected in logging curves: spontaneous potential (SP) and natural gamma (GR) curves often show bell-shaped or box-shaped forms. GR values are low in the lower and middle intervals with high sand content, and increase significantly when transitioning upward to fine-grained lithofacies. From the perspective of architectural hierarchy, point bars are divided into two parts: lateral accretion bodies and lateral accretion layers, both corresponding to the 3rd-order interface in Miall’s architectural unit classification system. Among them, lateral accretion bodies are the main sand-bearing components and the primary reservoir intervals of point bar reservoirs; lateral accretion layers are thin interbeds between adjacent lateral accretion bodies, imbricated and embedded within lateral accretion bodies. Lateral accretion layers are dominated by fine-grained sediments with clear logging identification markers: micro-potential and microelectrode curves show low values with obvious regression characteristics, SP curves shift toward the mudstone baseline, and GR presents significantly high values (Figure 6a). In the study area, the thickness of lateral accretion layers inside point bars is less than 15 cm (mostly 3–10 cm), lithologically dominated by mudstone, argillaceous siltstone, and silty mudstone. With low permeability, they act as vertical and lateral seepage barriers for point bar reservoirs.

Figure 6.

Identification Marks of Point Bar. (a) Internal Distribution Characteristics of Point Bar; (b) Sand Body Thickness Map of Ng44-1 Single Layer.

(2) Horizontally, point bar sand bodies are distributed in a typical beaded lenticular morphology and are the largest-scale sand body architectural units within composite channels. Therefore, sand body thickness can serve as an important marker for identifying individual point bars. Referring to the method proposed by Shan Jingfu et al. [37], which combines the initial and final streamline envelope method with sand thickness to identify point bars, taking the single sand layer Ng44-1 as an example, 6 single channels have developed along the sedimentary extension direction from near-provenance (north) to south. Point bar sand bodies are embedded in each channel in a lenticular shape, with thickness following the distribution law of “thicker in the center of the point bar and gradually thinning toward both sides of the channel” (Figure 6b).

(3) The occurrence of abandoned channels is a key marker for the end of the first stage of meandering river point bar development. Their spatial distribution is strictly controlled by paleochannel morphology: horizontally, the main body of point bars is always closely adjacent to abandoned channels or terminal channels, serving as an important marker for identifying point bar boundaries.

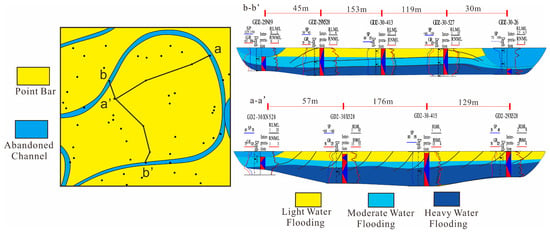

4.3. Reservoir Connectivity

The point bar sand bodies in the study area are mainly characterized by an internal section pattern of nearly en echelon arrangement. The lateral accretion layers have a gentle upper part, a steep middle part, and a gentle lower part, with connectivity at the lower part, and the top surfaces of each lateral accretion interbed are nearly horizontal. Taking a certain point bar and sand body as an example, this point bar is enclosed by meandering river abandoned channels. Section a-a′ is perpendicular to the point bar direction, where the lateral accretion layers generally present an en echelon imbricated shape; Section b-b′ is parallel to the point bar direction, where the lateral accretion layers extend nearly horizontally in the section and gradually incline toward both sides of the abandoned channel (Figure 7). Through the dissection of lateral accretion mudstone, it is concluded that the remaining oil is concentrated in the upper part of the lateral accretion mudstone, while the lower part of the sand body is connected and suffers from severe water flooding.

Figure 7.

Anatomy of Interbed Cross-Section Morphology in a Typical Well. Water (blue) and oil (red).

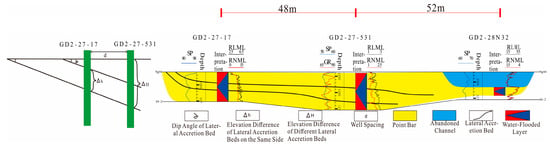

4.4. Scale and Dip Angle of Lateral Accretion Bodies and Lateral Accretion Layers

To quantitatively characterize the dip angle of lateral accretion mudstone interbeds, this paper first selects paired wells with small spacing within point bars. It identifies the development positions of lateral accretion layers based on the logging response characteristics of individual wells, then projects the depths of those layers from the two wells onto a single cross-well profile. In accordance with the principle of stratigraphic sedimentary continuity, lateral accretion layers with similar characteristics in the two wells are correlated to construct a lateral accretion layer correlation profile. After the top flattening treatment of the profile is completed, the apparent dip angle α of the lateral accretion layer is calculated by the height difference of the same lateral accretion layer divided by the horizontal distance between the two wells. Taking the cross-well profile of Well GD2-27-17 and Well GD2-27-531 in the study area as an example (Figure 8), the horizontal distance between the two wells is 48 m, and the height differences of the two corresponding connected groups of lateral accretion layers are 2.5 m and 4 m, respectively. Combined with the above calculation method, the dip angles of the lateral accretion layers are 3° and 4.76° in sequence.

Figure 8.

Calculation of Dip Angle of Lateral Accretion Beds Using Paired Wells Method.

Thirty pairs of wells were selected for measurement in this paper. The results show that the thickness of a single lateral accretion body ranges from 1.5 m to 5.7 m, and the dip angle of the lateral accretion layer is between 3° and 5.72°.

Although the overall well pattern density in the study area is relatively high, due to the poor sand body continuity in some areas and the constraints of well location deployment conditions, effective pair wells cannot be fully formed in the entire area, making it difficult for this method to cover the quantitative research of all point bar lateral accretion layers. To accurately identify the dip angle of lateral accretion layers in the study area, this paper conducts quantitative characterization of the interior of point bars in the study area based on the relationship w = 1.5h/tanα [38] summarized by Leeder between bankfull channel width (w), bankfull channel depth (h), and lateral accretion layer dip angle (α). According to the formula calculation, the dip angle ranges from 3° to 6°. In addition, according to Leeder’s research results [38], the horizontal width of a single lateral accretion body is approximately 2/3 of the bankfull channel width, so the horizontal width of a single lateral accretion body is 32 to 255 m.

Synthesizing the above two methods, it is concluded that the dip angle of the lateral accretion layer of point bars in the study area ranges from 3° to 6°, the thickness of a single lateral accretion body is 1.5 m to 5.7 m, and the horizontal width of a single lateral accretion body is 32 to 255 m.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Sand Body Scale

Statistical analysis of the sand body thickness of wells that encountered point bars in the Ng44 sublayer was conducted, yielding a bankfull depth of the river ranging from 3.6 to 13.7 m with an average of 9.3 m. This average depth can be approximately taken as the bankfull depth of the channel. Leeder [38] and Lorenz [39] proposed that the relationships among bankfull depth (h), bankfull channel width (bc), width of a single meander belt (bm), and point bar span (bd) are as follows:

bc = 6.8h1.54

bm = 7.44bc1.01

1000bd = 0.8531In(bc/1000) + 2.4531

It is derived that the bankfull channel width is 210 m, the width of a single meander belt is 1648 m, and the point bar span is 1122 m. These results can reflect the quantitative characteristics of architectural units to a certain extent and can constrain the scale of meandering river architectural units during architectural analysis.

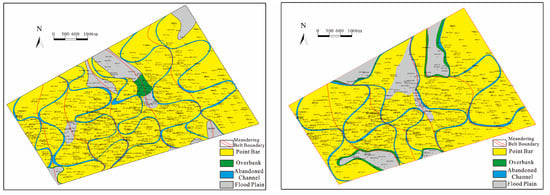

Following the division of the Ng44 sublayer based on the aforementioned identification markers for single meander belts and individual point bars, it is found that the Ng44 sublayer exhibits the characteristic of “continuous sheet-like sand body distribution”. It has good horizontal continuity and extensive spatial extension, with the maximum sand body width exceeding 1500 m. Channel neck cutoff occurs frequently, abandoned channels are widely developed with large distribution areas, and overbank sand bodies are developed in a “striped pattern” along the channel margins (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Planar Facies Maps of Single Sand Layer Ng44-1 and Ng44-2. (a) Planar Facies Map of 44-1; (b) Planar Facies Map of 44-2.

5.1.1. Statistical Sample Selection

To ensure the accuracy of statistical results, the Ng44 sublayer was selected as the core research layer in this study. This sublayer features a clear isochronous interface, diverse sandbody splicing types, and representative development scales. Lithological interfaces of architectural units were strictly determined based on core observations and logging response characteristics, while sandbody continuity was verified through interwell correlation analysis. Invalid units with missing logging curves or contradictions in interwell correlation were excluded. Sampling data were collected from the main channel, channel margins, and abandoned channel edges, and a total of 50 independent point bars, along with their corresponding channel widths and meander belt widths, were statistically analyzed. Systematic measurements show that the width of a single meander belt ranges from 450 to 1900 m with an average of 1420 m; the length of point bars ranges from 310.6 to 1754 m with an average of 1036.2 m; and the width of point bars ranges from 323.4 to 1586 m with an average of 1000.8 m.

5.1.2. Fitting Method and Empirical Formula Construction

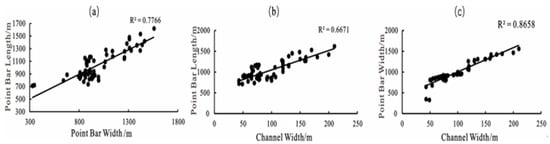

Correlation analysis of statistical parameters reveals a significant positive correlation between point bar length (Lp), point bar width (Wp), and channel width (Wr) in the study area (Figure 10). To quantify this correlation, scatter plots were drawn, indicating an approximately linear relationship among the variables. The least squares method was adopted to minimize the sum of squared residuals, ensuring the optimal fitting result. Based on valid samples, an empirical formula for the quantitative characterization of single sand bodies suitable for the study area was established.

Figure 10.

Relationship Curve of Point Bar Length, Point Bar Width, and Channel Width.

5.1.3. Anatomical Results and Rationality Explanation of R2

A comparison between the above calculation results and the actual anatomical results of the study area shows that the point bars and single meander belts obtained through anatomy are slightly smaller than the calculated values. The reasons for this are speculated to be: frequent channel avulsion in the study area leading to varying migration intensities of meandering rivers at different stages; uneven restriction intensity of some meander belts by floodplain mudstones; and deviations in point bar division caused by local thin lateral accretion mudstone interbeds with weak logging responses. As shown in the figure, the correlation between point bar length and channel width is relatively weak. This may be attributed to the fact that the point bar scale is not only controlled by channel width but also affected by factors such as the development degree of overbank deposition and the superposition mode of lateral accretion bodies. These variables were not included in the statistics, resulting in incomplete coverage of explained variance. Additionally, identification errors of some thin interbeds indirectly affect the accuracy of parameter statistics. Some point bars may have undergone tongue-shaped rapid progradation due to flood events, leading to morphological differences in point bars corresponding to channels of the same scale, which are difficult to fit through a single linear simulation.

The expression of the empirical formula is as follows:

Lp = 8.533Wr + 81.7

WP = 6.19Wr + 45.4

WP = 1.57Lp + 74.6

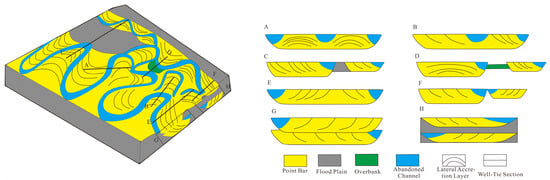

5.2. Architectural Pattern

This study establishes an architectural model of the meander belt in the northern part of Middle Block 2, Gudao Oilfield, from planar, vertical to spatial scales (Figure 11). The core feature of this model is “multi-level interfaces controlling percolation and multi-dimensional contacts determining connectivity”: it exhibits “overall connectivity-local separation” heterogeneity in the planar view, forms differentiated contacts controlled by channel incision intensity in the vertical direction, and ultimately constructs a complex internal structure characterized by “planar differentiation-vertical stratification-spatial composite”.

Figure 11.

Anatomy of Interbed Cross-Section Morphology in a Typical Well. Same direction of lateral accretion layers: (A,B) point bars—abandoned channel—point bar; (C) point bar—floodplain—point bar; (D) point bar–overbank—point bar. Different directions of lateral accretion layers: (E) point bar—point bar; (F) point bars—abandoned channel—point bar. Vertically: (G) Vertically stacked type. (H) Isolated type.

In the planar view, complex meander belt sand bodies are generally connected, i.e., multiple channels are joined to form a unified oil-water movement system. Single sand bodies of different origins within composite channels control the planar distribution of permeability; meanwhile, abandoned channels within single-stage channels, contact boundaries of multi-stage channels, and overbank or flood plain deposits between channels form various planar barriers or percolation resistance layers within the same connected body. Within each separated single-stage channel, different microfacies show differentiation in percolation capacity due to differences in lithology and pore structure; affected by variations in river migration, lateral accretion interlayers with barrier effects inside point bar sand bodies form different contact patterns such as continuous barriers and discontinuous separations.

In the vertical direction, if later-stage channels intensely incise and stack on early-stage sand bodies, the two vertical stages of sand bodies have good connectivity, forming thick multi-stage connected bodies; if later-stage channels only incise the upper part of early-stage sand bodies, the two are disconnected due to the barrier of argillaceous interlayers between them.

The local separations in the planar view and differentiated contacts in the vertical direction superimpose on each other, jointly shaping the spatial internal structure of complex meander belt composite sand bodies. Diverse contact relationships result in different percolation capacities.

5.3. Discussion

Based on the advantage of dense well patterns, this paper conducts a fine characterization of key architectural units in meandering river reservoirs. In previous studies on meandering river reservoir architecture, spatial distribution was mainly inferred relying on seismic data, core observation, and dynamic data [15,16,26]. However, in areas with low well pattern density or frequent channel migration, large interwell spacing and ambiguous architectural unit boundaries often lead to deviations between reservoir connectivity judgments and reality, resulting in a lack of reliable characterization methods.

The innovation of this paper lies in establishing a reservoir architectural dissection method adapted to the dense well pattern and meandering river sedimentary setting. Relying on high-density well pattern logging responses and core observation, it can accurately identify architectural units such as point bars and abandoned channels and predict their distribution. This method focuses on the fine description of lateral accretion layers inside point bars, clarifies their controlling effect on reservoir heterogeneity and remaining oil distribution, provides a new approach to solving the problem of fine characterization of meandering river reservoirs, and has important practical significance for remaining oil tapping and optimization of injection-production well patterns in the middle and late stages of oilfield development.

It should be noted that this method imposes high requirements on the uniformity of well pattern density and the accuracy of single-well data. In practical applications, priority should be given to the standardization of logging curves, and architectural interpretation results should be verified in combination with dynamic production data to ensure the credibility of the dissection results. Meanwhile, the method identifies natural gamma (GR), spontaneous potential (SP), and dynamic production pressure as core identification parameters through interwell interpolation of dense well patterns, dynamic connectivity analysis, and screening of well deployment conditions. It is emphasized that the selection of parameters is not unique, and their effectiveness depends on differences in the sedimentary background of the study area and the completeness of dense well pattern data. Notably, during the architectural characterization process, logging responses are affected by lithological mixing, changes in fluid properties, and borehole conditions, which may lead to deviations in the identification of architectural units. For instance, the GR responses of thin interbedded argillaceous interlayers and lateral accretion mudstones are prone to overlap, making it difficult to distinguish them precisely with a single curve. In addition, the logging facies characteristics of channel sand bodies from different sedimentary stages exhibit transitionality, which may result in misjudgment of architectural boundaries. Uncertainties also exist in interwell correlation: although dense well patterns shorten the interwell distance, the randomness of meandering river migration and the lateral pinch-out characteristics of lateral accretion bodies may still lead to multi-solutionality in the correlation of interwell architectural units. For example, the correspondence of lateral accretion layers between adjacent wells may deviate from reality due to changes in channel curvature, or misjudgment of channel stages may occur due to the lithological similarity of abandoned channel fillings. Dynamic production pressure data can reflect the variation law of water cut, verify interwell architectural connectivity, and reduce the multi-solutionality of correlation.

The architectural model proposed in this study has also been observed in multiple regions. For example, in the tidally influenced meandering river reservoir of the Athabasca Oil Sands in Alberta, Canada [40], the “intermittent separation” feature formed by lateral accretion mudstones inside point bars is consistent with the planar “local separation” architectural law identified in this study. In the incised valley fill reservoir of the Kern River Oil Field in California, USA [41], the intense incision of early sand bodies by late-stage channels results in vertical “strong connectivity”, which is highly consistent with the control mechanism (incision intensity) of vertical contact relationships in this study, confirming the applicability of the multi-level interface permeability control law in temperate-subtropical meandering river systems.

Outcrop studies of the meandering river reservoir in the Montllobar Formation in the southern Pyrenees, Spain [42] have shown that interchannel overbank/floodplain mudstones and abandoned channel fillings form planar permeability barriers, which is consistent with the functional mechanism of planar “separators” in this study. In the meandering-braided river transition zone reservoir of the Walloon Formation in the Surat Basin, Australia [43], coal seams and argillaceous interlayers deposited in meandering rivers during the highstand of base level form vertical separations, which is consistent with the vertical “weak connectivity” model in this study.

In future applications in similar meandering river reservoirs, it is necessary to further optimize core parameters and interpretation processes by integrating the sedimentary evolution characteristics and well pattern distribution laws of specific regions. Additionally, machine learning algorithms should be introduced to improve the degree of automation in architectural unit identification, thereby providing more robust support for the efficient development of meandering river reservoirs worldwide.

6. Conclusions

(1) The Ng3~Ng4 sandstone groups of the Upper Guantao Formation in the northern part of Block 2 Middle, Gudao Oilfield, are of meandering river deposition, mainly developing four types of architectural units: channel sand bodies, flood plains, abandoned channels, and overbank sand bodies. Based on Miall’s fluvial architectural hierarchy theory, hierarchical analysis of the 3rd~5th orders was conducted, namely the architectural dissection of single meander belts, point bars, and internal hierarchies of point bars. Four types of identification markers—interchannel deposits, abandoned channel filling, differences in sand body thickness, and differences in top elevation—were used for lateral demarcation of composite meander belts. According to the vertical superposition differences of the channel sand bodies, three types of vertical division markers were summarized: mudstone interbeds, logging curve regression, and adjacent well correlation constraint.

(2) The development positions of point bars in the study area were identified based on point bar sand body thickness, single-well logging responses, vertical sedimentary sequence characteristics, and distribution characteristics of point bars being closely adjacent to abandoned channels. Measurements show that single meander belts have a width of 600–1900 m with an average of 1420 m; point bars have a length of 310.6–1754 m with an average of 1076.3 m and a width of 223.4–1586 m with an average of 1037.8 m. Through correlation analysis of parameters such as point bar length, width, and channel width, an empirical formula suitable for the study area was proposed, providing a basis for predicting single sand bodies in sparsely well-patterned areas of the region.

(3) In the study area, lateral accretion layers in point bars show mainly sub-oblique profile patterns, with dip angles of 3–6°, and most are 3–10 cm thick. Individual lateral accretion bodies are 1.5–5.7 m thick and 32–255 m in horizontal width. Eight main sand body architectural models of composite meander belts are established based on sand body configuration relationships across architectural hierarchies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y.; methodology, H.Y. and L.W.; Software, L.W.; Validation, L.T. and L.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.; Writing—review and editing, L.W.; supervision, L.W.; Project administration, L.W.; Funding acquisition, L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ongoing studies using a part of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jiang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Chen, X. Basic characteristics and evaluation of shale oil reservoirs. Pet. Res. 2016, 1, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.C.; Yuan, G.H.; Yang, H.J.; Wang, Y.Z.; Liu, K.Y.; Zan, N.M.; Xi, K.L.; Wang, J. Current situation of oil and gas exploration and research progress of the origin of high-quality reservoirs in deep-ultra-deep clastic reservoirs of petroliferous basins. Acta Pet. Sin. 2022, 43, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.L.; Guo, B.C.; Yang, Z.P.; Gao, X.J.; Hui, L.; Cai, Z.C.; Guo, Y.Q. Characteristics of sedimentary microfacies of Triassic Yanchang Formation Chang 6_1 in Hengshan area and its influence on reservoir heterogeneity. J. Northwest Univ. 2020, 50, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.L.; Chen, L.H.; Zhang, F.Q.; Liang, Y.Q. Pore evolution in tight sandstone and its impact on oil saturation: A case study of Chang 6 to Chang 8 reservoirs in Triassic Yanchang Formation, Ganquan area, Ordos Basin. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2024, 46, 1145–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Qiu, B.; Shi, X.; Bai, J.; Li, W.X.; Chen, Y.Q.; He, B.B. Characteristics and influencing factors of tight sandstonereservoirs in the second member of the Permian Jingjingzigou Formation, Jinan Sag. Chin. J. Geol. 2024, 59, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.J.; Zhang, C.M.; Gai, S.S.; Yu, W.Z.; Li, J.; Yuan, H.H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.P. Diagenetic facies identification and distribution prediction of Jurassic ultra-deep tight sandstone reservoirs in Yongjin Oilfield, Junggar Basin. Pet. Geol. Recovery Effic. 2024, 31, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Wu, S.H.; Wang, R.F.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.F.; Xu, Q.Y.; Xiong, Q.C.; Yu, J.T.; Wang, L. Submarine fan reservoir architecture of deep-water X gas reservoir in the Rovuma Basin, East Africa: Implications of gravity flow-underflow interaction. Paleogeography 2023, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.D. Architectural-element analysis: A new method of facies analysis applied to fluvial deposits. In Recognition of Fluvial Depositional Systems and Their Resource Potential; SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology): Claremore, OK, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Zhao, Y.C.; Li, S.M.; Xu, X.M. Research and prospect of reservoir architecture of different sedimentary systems. Pet. Geol. Xinjiang 2013, 1, 5. Available online: https://www.zgxjpg.com/EN/abstract/abstract442.shtml (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Baker, P.L. Fluid, lithology, geometry, and permeability information from ground-penetrating radar for some petroleum industry applications. In Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition, SPE, Perth, Australia, 4–7 November 1991; SPE-22976-MS. ISBN 978-1-55563-519-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.M. Hierarchical Analysis Method in Reservoir Research. Oil Gas Geol. 1992, 13, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miall, A.D. The Geology of Fluvial Deposits: Sedimentary Facies, Basin Analysis, and Petroleum Geology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posamentier, H.W.; Laurin, P.; Warmath, A. Cenozoic Carbonates Systems of Central Australasia; 2000; pp. 104–121. Available online: https://sedimentary-geology-store.com/catalog/book/cenozoic-carbonate-systems-australasia (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Szerbiak, R.B. 3D description of clastic reservoirs: From 3D GPR data to 3D fluid permeability model. Prog. Explor. Geophys. 2002, 25, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, J.H. Conditions for formation of massive turbiditic sandstones by primary depositional processes. Sediment. Geol. 2004, 166, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.; Ricken, W. Quartz cementation and related sedimentary architecture of the Triassic Solling Formation, Reinhardswald Basin, Germany. Sediment. Geol. 2005, 175, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Yue, D.L.; Liu, J.M.; Shu, Q.L.; Fan, Z.; Li, Y.P. Hierarchical Modeling of Subsurface Paleochannel Reservoir Architecture. Sci.China 2008, S1, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backert, N.; Ford, M.; Malartre, F. Architecture and sedimentology of the Kerinitis Gilbert-type fan delta, Corinth Rift, Greece. Sedimentology 2010, 57, 543–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Jiang, Y.L.; Yue, D.L.; Yin, S.L. Discussion on hierarchical scheme of architectural units in clastic deposits. Geol. J. China Univ. 2013, 19, 12. Available online: https://geology.nju.edu.cn/CN/Y2013/V19/I1/12 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Hu, G.Y.; Chen, F.; Fan, T.E.; Sun, L.C.; Zhao, C.M.; Gao, Y.F.; Wang, H.; Song, L.M. Analysis of Stacking Patterns of Fluvial Composite Sand Bodies in the Neogene Minghuazhen Formation of Oilfield, S., Bohai Sea Area. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2014, 32, 586–592. Available online: http://119.78.100.143/article/id/1084 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Qu, X.Y. Sequence stratigraphy division and petroleum geological significance in the middle submember of the third member of Shahejie Formation in Liangdong area, Dongying Sag. Lithol. Reserv. 2025, 37, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Zhu, X.M.; Liao, F.Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, R.Z.; Cao, L.G.; Shi, R.S. Features and control factors of gentle-sloped fluvial sandbodies in rift basins: An example from the Wen’an Slope, Baxian Sag. Earth Sci. Front. 2021, 28, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.F.; Ren, Q.Q.; Yang, T.; Cai, L.X.; Li, Z.; Cui, R. Development characteristics of structural fractures in tight sandstone reservoirs under multi-level configuration interfaces: A case study of second member of Xujiahe Formation in Western Sichuan Depression. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2024, 46, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.H.; Yue, D.L.; Feng, W.J.; Zhang, J.J.; Xu, Z.H. Research progress of depositional architecture of clastic systems. J. Palaeogeogr. 2021, 23, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.Y.; Luo, S.L.; Li, L.X.; Tian, Z.L.; Hu, G.M.; Liu, Q.Q.; Feng, J.W. Reservoir Architecture Characterization of Meandering River in the Guantao Formation of Block 4, Gudong Oilfield, and Its Control on Remaining Oil. Pet. Geol. Dev. Daqing 2023, 42, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.E.; Yin, T.J.; Wang, Y.J. Characterization of meandering-river reservoir architecture under sparse well pattern condition in Bohai Sea. Dev. Daqing 2022, 41, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, J.S.; Tye, R.S. Interpreting the dimensions of ancient fluvial channel bars, channels, and channel belts from wireline-logs and cores. AAPG Bull. 2000, 84, 1205–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranter, M.J.; Vargas, M.F.; Davis, T.L. Characterization and 3D reservoir modelling of fluvial sandstones of the Williams Fork Formation, Rulison field, Piceance basin, Colorado, USA. J. Geophys. Eng. 2008, 5, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Wang, Z.Z.; Li, L.; Li, H.M.; Pan, L.; Wang, K.Y. Application of Geological Knowledge Database of Modern Meandering River Based on Satellite Image. Geoscience 2015, 29, 1444–1453. Available online: https://www.geoscience.net.cn/thesisDetails?columnId=103996546&Fpath=home&index=0&lang=zh (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Liu, R.H. Study on Sand Body Architecture of Complex Meander Belts and Its Control on Remaining Oil Distribution(Ph.D. thesis). Northeast Petroleum University, Daqing, China, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.C.; Zhang, X.; Shen, H.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, L.X. Treatment Technology for Water Injection Blocks in Eastern Gudao Oilfield. Oil Gas Field Surf. Eng. 2006, 12, 24–25. Available online: https://yqtd.cbpt.cnki.net/WKC/WebPublication/paperDigest.aspx?paperID=8add6a03-d570-476e-9380-3c5b77f0b936# (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Dali, Y. Hierarchy analysis in paleochannel reservoir architecture: A case study of meandering river| reservoir of Guantao Formation| Gudao Oilfield. Chin. J. Geol. 2010, 45, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. Study on Architectural Structure of Fluvial Reservoirs in Gudao Oilfield. China Sci. Technol. Inf. 2009, 19, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Distribution Characteristics and Controlling Factors of Guxi Buried Hill in Jiyang Depression. Adv. Geosci. 2023, 13, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.H.; Yue, D.L.; Li, W.; Guo, C.C.; Li, X.; Lv, M. Identification of Point bar and abandoned Channel of meandering river by spectral decomposition inversion on machine learning. Oil Geophys. Prospect. 2023, 58, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.T.; Yu, X.H.; Pan, S.X.; Tan, C.P.; Li, S.L.; Zhang, Y.P. Sedimentary Characteristics and Sedimentogenic-based Sandbodies Correlation Methods of Meandering River in Toutunhe Formation, Southern Margin of Junggar Basin. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2013, 24, 1132–1139. Available online: https://www.zhangqiaokeyan.com/academic-journal-cn_detail_thesis/02012104914281.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Shan, J.F.; Zhao, Z.J.; Li, F.P.; Sun, L.X.; Tang, N.Q.; Wang, B.; Gao, H.X. Sedimentary Evolution Process and Historical Reconstruction of Meandering Channels: A Case Study of Dachengzi Oil Layer in Fuyu Oil Production Plant, Jilin Oilfield. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2015, 33, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeder, M.R. Fluviatile fining-upwards cycles and the magnitude of palaeochannels. Geol. Mag. 1973, 110, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, J.C.; Heinze, D.M.; Clark, J.A.; Searls, C.A. Determination of widths of meander-belt sandstone reservoirs from vertical downhole data, Mesaverde Group, Piceance Creek Basin, Colorado. AAPG Bull. 1985, 69, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, S.M.; Smith, D.G.; Nielsen, H.; Leckie, D.A.; Fustic, M.; Spencer, R.J.; Bloom, L. Seismic geomorphology and sedimentology of a tidally influenced river deposit, Lower Cretaceous Athabasca oil sands, Alberta, Canada. AAPG Bull. 2011, 95, 1123–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, D.K.; Allen, J.; Beeson, D.; Robbins, J. Fluvial reservoir architecture, directional heterogeneity and continuity, recognizing incised valley fills, and the case for nodal avulsion on a distributive fluvial system: Kern River field, California. AAPG Bull. 2023, 107, 477–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzel, M.; Jones, S.J.; Meadows, N.; Allen, M.B.; McCaffrey, K.; Morgan, T. Basin-scale fluvial correlation and response to the Tethyan marine transgression: An example from the Triassic of central Spain. Basin Res. 2021, 33, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.R.; Martin, M.A. Coal architecture, high-resolution correlation and connectivity: New insights from the Walloon Subgroup in the Surat Basin of SE Queensland, Australia. Pet. Geosci. 2017, 23, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).