Abstract

This study investigates the home-court advantage (HA) and home win percentage (HW) in women’s professional basketball across 14 leagues spanning four continents over three seasons (2021–2024). This study is an observational descriptive analysis based on open access match results. Using data from 12,178 games, we analyzed HA and HW, accounting for team ability and geographical variations. The findings indicate significant differences in HA across continents, with Europe and South America showing higher HA compared to Oceania and Asia. However, HW did not vary significantly between continents. When examining team ability, no significant interaction effects were identified, although trends suggested that low-ability teams rely more heavily on HA, consistent with previous research. A more detailed league-level analysis revealed notable variability, with leagues in the United States of America (USA), Australia, and several Asian leagues showing lower HA compared to those in Mexico and Europe. Factors like travel demands, geographical region, and fan attendance were identified as key determinants. For instance, leagues with extensive travel requirements, particularly in Asia and Oceania, demonstrated lower HA, consistent with studies showing that travel negatively impacts performance. Additionally, reduced fan attendance in women’s basketball may further diminish HA.

1. Introduction

The phenomenon of home-court advantage (HA) has been widely documented across multiple team sports, including basketball [1,2]. In 1972, HA was defined through an analysis of numerous competitions [3]. This concept refers to a statistical phenomenon that associates match location with competition outcome [3]. In simpler terms, teams are more likely to win when playing at home compared to playing away [4]. In addition to HA, recent studies have introduced the home win percentage (HW), which specifically measures a team’s success rate in games played at home [5,6].

HA in basketball has been extensively studied in relation to various contextual factors, including the country in which the home team is located [7], travel demands [8], the influence of spectators [5,9], and game scheduling [10,11]. Nevertheless, most studies on HA have focused on male basketball players, while paying limited attention to women’s basketball competitions. A recent systematic review identified only two studies specifically addressing HA in women’s basketball [12]. A comparative analysis of HA and HW in Spanish basketball leagues was conducted [13], reporting that men’s teams achieved significantly higher HA and HW than women’s teams. Similarly, research in the Spanish Women’s Basketball First Division examined HA and HW under different spectator conditions and found no significant variations [14]. Their findings revealed no significant differences in HA or HW across different periods (pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic) or between games with and without spectators [14].

Moreover, studies on HA in women’s basketball leagues have primarily been conducted in Europe [13,14,15] and the United States of America (USA) [1,16]. Consequently, the HA in women’s basketball from other continents may be underrepresented. Analyzing HA and HW across women’s basketball leagues worldwide could provide insights for the development of targeted strategies to optimize team performance. Further research into HA in women’s basketball is necessary to obtain a comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon in the sport [12]. In addition, it was reported that there is a significant 6.75% greater HA in college men’s basketball compared to professional men’s basketball (66.61 vs. 59.90%, respectively) [1]. Conversely, no such differences were observed between college and professional women’s basketball. Similarly, differences in HA and HW between male and female basketball teams were examined, finding that men’s teams competing in professional leagues across various countries exhibited a higher HA (60.1%) compared to women’s teams (55.6%) [15]. However, in the A1 Greek Basketball League during the 2014–2015 season, HW was nearly identical between sexes (61.5% for men and 61.4% for women) [15]. Similar results were reported in the top USA basketball leagues (NBA and WNBA) where differences in HA (p = 0.731) or HW (p = 0.890) were observed between leagues [17].

In addition, the geographical region of the competition and team abilities have been identified as potential factors influencing HA in professional basketball [4]. Teams based in regions characterized by extreme climates or high altitudes may benefit from a natural home advantage, as they are better adapted to these conditions, whereas visiting teams often face difficulties to adapt [4]. Moreover, team ability plays an important role. While many studies indicate that strong teams tend to perform better regardless of the venue, whereas weaker teams rely more on advantages associated with playing at home [5,6,13], this pattern is not universal. Evidence from NBA, for instance, suggests that strong teams outperform teams of lower ability levels [18]. Analyzing these factors is crucial, as it helps clarify performance outcomes, audience effects, and strategic decisions. Based on this premise, our first hypothesis predicts the existence of HA in women’s basketball leagues, with variations between countries and continents. Accordingly, the aims of the present study are (i) to quantify HA and HW in women’s professional basketball leagues, (ii) to identify differences in HA and HW between continents, and (iii) to compare the results across various basketball leagues.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

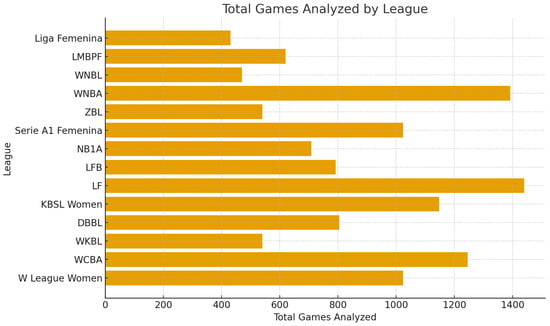

Data were obtained from 12,178 games played across 14 women’s professional basketball leagues (Table 1 and Figure 1). The dataset included three regular seasons (from the 2021–2022 to 2023–2024 season). Since the data were open access, obtaining participant informed consent was not required.

Table 1.

Number of team–season observations and total games by league and continent.

Figure 1.

Distribution of total games across leagues.

2.2. Procedures

Data were extracted from the open access website www.flashscore.es (Accessed on 13 October 2024). The leagues included in this study were selected based on three conditions: (i) the availability of full, season-by-season match results in open access format; (ii) representation of the main professional women’s leagues in each continent; and (iii) a sufficient number of teams and games to support robust statistical analysis. The variables collected included season, country and continent of each league, wins at home, wins away, total wins, total matches played, and total matches played at home per season. Each observation corresponds to a single team within a single regular season. All seasons were analyzed collectively. Only regular-season games were included in the analysis. Playoff games were excluded to avoid confounding effects related to seeding, competitive imbalance, or shortened travel distances. Data were extracted using customized Microsoft Excel (version 16.0, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheets for further calculation of HA [(total home wins/total wins) × 100] [7,19], home win percentage (HW) [(total home wins/total home games) × 100] [5,13], and team ability [(total wins/total games) × 100] [7]. Teams were categorized according to team ability in each season (e.g., a team that won 40 out of 50 games would have a win percentage of 40/50 = 80%) [5,13]. In this way, a two-step cluster analysis was used to stratify teams according to ability into two different groups (average silhouette = 0.7) as follows: high-performance teams (win percentage = 74.24 ± 12.82%, n = 210 team samples or 41.5% of total dataset) and low-performance teams (win percentage = 32.65 ± 14.21%, n = 296 team samples or 58.5% of total dataset).

Team ability was classified using a two-step cluster analysis employing the log-likelihood distance measure and the Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to determine the optimal solution. Models with two, three, and four clusters were evaluated, with the two-cluster solution selected based on the highest silhouette coefficient (0.7), indicating the best cohesion–separation balance. This data-driven approach was chosen to avoid arbitrary cutoff points and to ensure a robust classification that reflected the natural structure of performance data across leagues.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

A descriptive analysis was conducted for all of the variables using the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for parametric data and the median ± interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-parametric data. The Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to examine differences between continents or leagues, and if a significant effect was detected, post hoc Dunn’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. The interaction between group (continent or leagues) and team ability (group × team ability) was also examined. For this purpose, a two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc correction was implemented for each variable. Eta partial squared (η2p) was used to determine the magnitude of the effect independently of the sample size; η2p has previously been recommended for ANOVA designs [20] and interpreted based on the recommendations of Cohen: small < 0.06, medium 0.06 to 0.14, and large > 0.14. Then, if a significant effect was detected, Cohen d effect size and the associated 95% CI for pairwise comparisons were applied and interpreted based on the following: trivial < 0.2, small ≥ 0.2 < 0.6, moderate ≥ 0.6 < 1.2, large ≥ 1.2 < 2.0, and very large ≥ 2.0 [21]. All analyses were conducted using JASP Team (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.1) [MacOs Monterrey 12.7.6]. For all analyses, we set statistical significance at p < 0.05.

3. Results

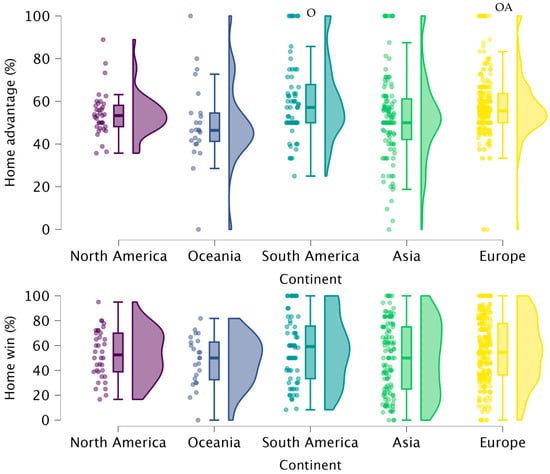

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences for HA (p <0.001; η2p = 0.072) between continents. Dunn’s post hoc comparison showed that Oceania had a significantly lower HA compared to South America (p = 0.020) and Europe (p = 0.017). Moreover, a significantly lower HA in Asia compared with Europe was observed (p = 0.021) (Figure 2). However, non-parametric analyses did not reveal significant differences for HW between continents (p = 0.257; η2 = 0.003) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Raincloud plots of comparative analysis of HA (upper panel) and HW (lower panel) between the main women’s basketball leagues in Europe according to team ability. Significance is indicated by symbols: O significant differences vs. Oceania; A vs. Asia. The scatterplots represent the distribution of the individual values. The whisker box represents the distribution and the middle line, and the bars represent the median, 95% CI, and SD of the given group. The raincloud plots represent the overlapped distribution of 2 groups.

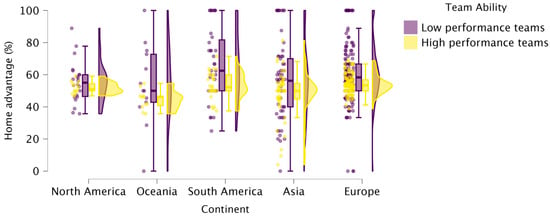

The two-way ANOVA revealed that there was no significant interaction effect of continent × team ability for HA (p = 0.585; η2 = 0.005) and HW (p = 0.066; η2 = 0.011) when continent was compared to team ability (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Raincloud plots of comparative analysis of HA (upper panel) and HW (lower panel) between continents according to team ability. The whisker box represents the distribution and the middle line, and the bars represent the median, 95% CI, and SD of the given group. The raincloud plots represent the overlapped distribution of 2 groups.

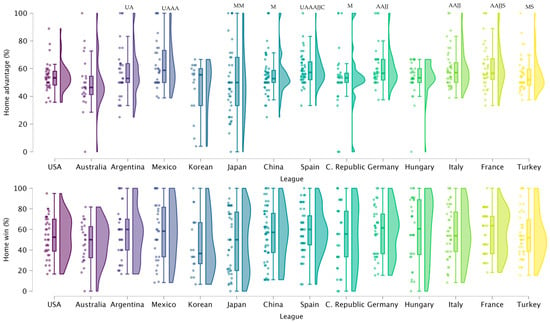

Figure 4 shows the comparisons for HA and HW in leagues. The results of the Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences for HA (p = 0.002; η2 = 0.042), but no significant differences for HW (p = 0.848; η2 = 0.00), between leagues. The USA showed significant a lower HA than Mexico (p = 0.034) and Spain (p = 0.033). Moreover, Australia showed a significantly lower HA than Argentina (p = 0.037), Mexico (p < 0.001), Spain (p < 0.001), Germany (p = 0.002), Italy (p = 0.002), and France (p = 0.002). Mexico presented a significantly higher HA than Japan (p = 0.002), China (p = 0.041), the Czech Republic (p = 0.037), and Korea (p = 0.048). While significantly lower values of HA were found for Japan compared with Spain (p = 0.001), Germany (p = 0.003), Italy (p = 0.005), and France (p = 0.003), in contrast, Spain showed a significantly higher HA than China (p = 0.039), the Czech Republic (p = 0.037), and Korea (p = 0.048).

Figure 4.

Raincloud plots of comparative analysis of HA (upper panel) and HW (lower panel) between the main women’s basketball leagues worldwide. The whisker box represents the distribution and the middle line, and the bars represent the median, 95% CI, and SD of the given group. The raincloud plots represent the overlapped distribution of 2 groups. Significance level is indicated by the number of symbols: one symbol for p < 0.05, two for p < 0.01, and three for p < 0.001; U significant differences vs. USA; A vs. Australia; M vs. Mexico; J vs. Japan; C vs. China; and S vs. Spain.

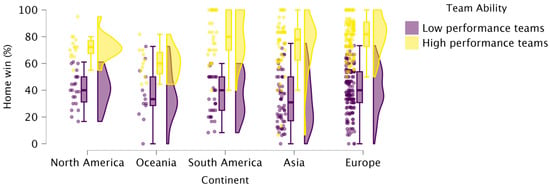

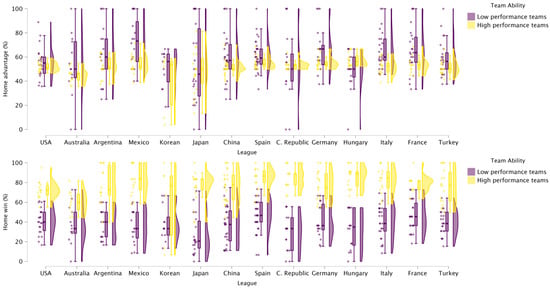

A descriptive analysis of HA and HW depending on region and team ability can be found in Table 2. When considering team ability and leagues, a significant interaction effect was evident for HW (p = 0.001; η2 =0.029), but no significant interaction results were found for HA (p = 0.205; η2 =0.031) (Figure 5). Regarding HW, the results of the Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that significant differences were identified between some league pairings and high-performance teams (Australia < Spain p = 0.042, Czech Republic p = 0.033, and Hungary p = 0.008) and low-performance teams (Japan < Spain p < 0.001 and France p = 0.014; Spain > Czech Republic p = 0.025) (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of HA and HW depending on region and team ability.

Figure 5.

Raincloud plots of comparative analysis of HA (upper panel) and HW (lower panel) between the main women’s basketball leagues worldwide according to team ability. The whisker box represents the distribution and the middle line, and the bars represent the median, 95% CI, and SD of the given group. The raincloud plots represent the overlapped distribution of 2 groups. Significance level is indicated by the number of symbols: one symbol for p < 0.05, two for p < 0.01, and three for p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

The aims of the present study were (i) to quantify the home advantage (HA) and HW in women’s professional basketball leagues, (ii) to identify any differences between continents in women’s basketball, and (iii) to compare the results obtained across different basketball leagues.

Based on the authors’ understanding, this is the first study that compares HA and HW across different continents competing in elite women’s basketball leagues while also accounting for team ability. The key findings indicate that Europe and South America exhibited higher levels of HA and HW compared to Oceania and Asia. However, no significant differences were observed when stratifying teams by ability across continents. Furthermore, the results demonstrate a significant impact of HA and HW on different team abilities and leagues worldwide.

Our data reveal that teams from Europe and South America showed significantly greater HA compared to those from Oceania. This finding aligns with previous research in football, which reported that HA in leagues from Japan, South Korea, and China is relatively lower [22]. This phenomenon could be partially explained by the fact that Asian leagues, similar to those in Oceania, span much larger geographical areas. In such contexts, both the home and away teams are regularly exposed to long-distance travel, which may reduce the relative disadvantage typically experienced by the away team. Consequently, the difference between home and away performance narrows, resulting in lower HA values rather than higher ones. In contrast, HW did not present significant differences between continents. Similarly, no significant differences in HA and HW were observed based on team ability. One potential factor contributing to the observed smaller home-court advantage (HA) in women’s basketball may be the consistently lower attendance at many women’s games. The presence of a large, supportive crowd has been proposed as a key mechanism for HA: for instance, a “natural experiment” during the 2020/2021 NBA season—when over half of the regular-season games were played without fans—showed that home teams won 58.65% of games with crowds, but only 50.60% when arenas were empty; moreover, home teams outrebounded and outscored opponents only when spectators were present [23]. Similarly, evidence from the European top-level EuroLeague indicates that home-audience advantage (HAA)—manifesting, for example, in lower turnover rates for home teams—was much weaker or absent in games played under empty-arena conditions during the COVID-19 era [13,24]. Hence, if women’s games systematically attract fewer or less dense crowds compared to men’s, this may partially explain the attenuated HA observed in female competitions. However—and importantly—data specifically linking crowd size or density to HA in women’s basketball remain extremely scarce. As such, this crowd attendance hypothesis should be treated as a tentative proposition, to be tested in future empirical work rather than stated as established fact.

The USA, Australia, Japan, China, and Korea showed lower values for HA compared to Mexico and most European leagues. While no prior study is directly comparable to this one, some research in elite basketball has shown that travel demands affect match outcomes [25]. For instance, in European basketball, it was found that greater travel distances negatively influenced certain game-related statistics [8]. However, this does not necessarily translate into a greater HA; instead, in leagues where long travel is systematic and affects all teams, the cumulative travel burden may be symmetrically distributed. Under these structural conditions, teams often adapt to frequent long-distance trips, and the relative advantage of playing at home becomes less pronounced. This suggests that HA may be influenced by travel distances, which are substantial in the USA, Australia, and Asian leagues.

The analysis of team ability by leagues revealed mixed results. Low-performance teams from Japan had a significantly lower HA compared to teams from Spain and France. Similarly, high-performance Australian teams exhibited a significantly lower HA compared to teams from Spain, the Czech Republic, and Hungary. These findings align with previous studies conducted in Europe [4,6,13]. In the study examining the five major men’s European Basketball Leagues (Spain, Germany, Italy, Greece, and Israel) over 16 regular seasons, teams were divided by ability into three groups (low ability, medium ability, and high ability) and it was observed that low-ability teams (win percentage = 32.85%) showed a higher HA compared to medium (win percentage = 55.27%) and high-ability teams (win percentage = 80.22%), while high-ability teams demonstrated higher HW than the other ability groups [4]. A similar trend was observed in the two premier Spanish basketball leagues, where during 12 seasons it was observed that lower-ability teams (win percentage = 38.0 ± 10.5%) tended to have a higher HA than higher-ability teams (win percentage = 71.7 ± 11.9%), while higher-ability teams presented a higher HW than lower-ability teams [13]. Additionally, in another study in Spain, it was observed that regardless of the league, lower-ability teams consistently showed a greater HA and lower HW compared with higher-ability teams [6]. Taken together, these findings align closely with the patterns observed in our study, indicating that across elite women’s basketball, teams with low-performance ability rely more heavily on home-court conditions to enhance performance, whereas high-performance teams tend to maintain greater HW.

However, this trend contrasts with findings from the NBA, the most competitive basketball league worldwide. A total of 24 regular season were analyzed and it was observed that contender teams (win percentage = 69.6 ± 5.0%) had a significantly higher HA and HW compared to teams with other ability levels, including low-ability teams (win percentage = 21.2 ± 5.4%) [18]. This inversion of the pattern suggests that that the influence of team ability may operate differently in highly professionalized environments, where higher-ability teams appear more capable of leveraging tactical, psychological, and contextual advantages than lower-ability teams to maximize home-court performance.

These findings underscore that HA is shaped by the interaction between competition level, team ability, organizational structure, geographical region, and fan engagement. The interactions of these factors produced distinct patterns across women’s leagues worldwide, suggesting that future investigations should analyze each contextual factor independently and in combination to better understand how HA can be optimized within each league.

The findings from this study have several practical implications. Sports psychologists and coaches can help professional teams mitigate the challenges of playing on the road by adopting strategies used by teams or leagues with a greater HA. These strategies often focus on mental preparation, emphasizing concentration and self-discipline to reduce the impact of unfamiliar environments and potentially hostile audiences. Teams should also avoid behaviors that could provoke referee bias, which could be influenced by home crowds [4,26,27,28]. Additional strategies include implementing consistent routines for away games and ensuring that travel is as smooth, predictable, and comfortable as possible to minimize stress and its impact on performance. For league organizers, understanding the contextual factors influencing HA could support improved scheduling, reduce unnecessary travel, and enhance competitive balance.

When interpreting our results, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. This study relied exclusively on publicly available match data, which prevented us from incorporating key contextual variables—such as detailed travel logistics, crowd behavior, arena capacity, or venue occupancy—that may meaningfully influence HA and HW [8,13]. As noted by the reviewer, our analysis represents a descriptive overview of performance patterns across leagues rather than an in-depth examination of each competition’s unique environment. Consequently, the conclusions should be interpreted with caution, as richer contextual information could lead to different insights. Additionally, our findings may not generalize to other populations, such as youth players or male professional leagues, given differences in competitive structure and performance profiles. Future research should integrate these contextual factors and examine longitudinal changes in HA as women’s basketball continues to professionalize and as attendance and organizational structures evolve.

5. Conclusions

This study reveals notable differences in home advantage (HA) across continents in women’s basketball, with teams from Europe and South America showing significantly higher HA compared to those from Oceania and Asia. However, no significant differences were observed in home winning percentage (HW) across continents. The reduced HA in regions like the United States of America (USA), Australia, and Asia may be attributed to factors such as extensive travel demands, which are particularly pronounced in these geographically expansive areas.

The analysis of team ability revealed that lower-performance teams tend to derive greater benefits from HA, a pattern consistent with findings in men’s basketball. To mitigate the challenges associated with away games, practical strategies such as enhanced mental preparation and optimized travel planning could prove beneficial.

This study does have limitations, including the exclusion of potentially influential factors such as crowd dynamics and detailed travel logistics. Future investigations should focus on addressing these limitations to enhance the overall understanding of HA in women’s basketball.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.L.-G. and R.N.-A.; methodology, E.A.-P.-C. and R.N.-A.; software, R.N.-A.; validation, A.L.-G.; formal analysis, R.N.-A. and A.L.-G.; investigation, A.L.-G. and R.N.-A.; resources, A.L.-G.; data curation, A.L.-G. and R.N.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.-G., E.A.-P.-C. and R.N.-A.; writing—review and editing, R.N.-A. and A.L.-G.; visualization, A.L.-G.; supervision, S.L.J.-S. and R.M.N.; project administration, A.L.-G. funding acquisition, A.L.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Non applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Non applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data were extracted from an open access website (www.flashscore.com).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HA | Home-court advantage |

| HW | Home win percentage |

| USA | United States of America |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQRs | Interquartile ranges |

References

- Pollard, R.; Gómez, M.A. Comparison of Home Advantage in College and Professional Team Sports in the United States. Coll. Antropol. 2015, 39, 583–589. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, R.; Pollard, G. Long-Term Trends in Home Advantage in Professional Team Sports in North America and England (1876–2003). J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koppet, L. Home Court: Winning Edge. The New York Times, 9 January 1972; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Portes, R.; Ribas, C.; Lorenzo, A.; Leicht, A.S.; Gómez, M.Á. Impact of Spectators, League and Team Ability on Home Advantage in Professional European Basketball. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2023, 131, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.; Lorenzo, A.; Ribas, C.; Gómez, M.Á. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on HOME Advantage in Different European Professional Basketball Leagues. Percept. Mot. Skills 2022, 129, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Chao, E.A.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Scanlan, A.T.; Martin-Castellanos, A.; Lorenzo, A.; Gómez, M.Á. Home-Court Advantage Is Greater for Teams Competing at Higher Playing Levels: An Exploratory Analysis of Spanish Male Basketball Leagues. Percept. Mot. Skills 2024, 131, 1708–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, M.A.; Pollard, R. Reduced Home Advantage for Basketball Teams from Capital Cities in Europe. Eur. J. Sport. Sci. 2011, 11, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, P.; Conte, D.; Gasperi, L.; Scanlan, A.; Ruano, M. Analysing Elite European Basketball Players’ Performances According to Travel Demands, Game Schedule and Contextual Factors. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2024, 25, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmuş, T.; Gülü, M. Comparison of the Home-Court Performances of Successful and Unsuccessful Teams at Euroleague Before and After COVID-19 Pandemic. Perform. Anal. Sport Exerc. 2022, 1, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Entine, O.A.; Small, D.S. The Role of Rest in the NBA Home-Court Advantage. J. Quant. Anal. Sports 2008, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenland, K.; Deddens, J.A. Effect of Travel and Rest on Performance of Professional Basketball Players. Sleep 1997, 20, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochales Cuesta, I.; Jiménez-Sáiz, S.L.; Kelly, A.L.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. The Influence of Home-Court Advantage in Elite Basketball: A Systematic Review. J. Funct. Morphol. Kinesiol. 2024, 9, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso Pérez-Chao, E.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Scanlan, A.T.; Lopez-García, A.; Lorenzo, A.; Gómez, M.Á. Is There No Place like Home? Home-Court Advantage and Home Win Percentage Vary According to Team Sex and Ability in Spanish Basketball. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2024, 24, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Martín-Castellanos, A.; Nieto-Acevedo, R.; Lopez-García, A.; Portes, R.; Gómez, M.Á. Examining the Role of Fan Support on Home Advantage and Home Win Percentage in Professional Women’s Basketball. Percept. Mot. Skills 2024, 131, 989–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krommidas, C.; Perkos, S.; Karatrantou, K.; Soulas, E.; Chasialis, A.; Armenis, E.; Gerodimos, V. Home Advantage Effect in Greek Basketball Leagues at the Regular Season: Males vs. Females and Home vs. Guest Teams. TRENDS Sport Sci. 2020, 26, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, S.; Maggio, P.; DeBeliso, M. A Longitudinal Investigation of Crowd Density and the Home Court Phenomenon in the Women’s National Basketball Association. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2022, 8, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, A.; Alonso-Pérez-chao, E.; Navarro, R.M.; Jiménez-Sáiz, S.L. Exploring Home-Court Advantage and Home Win Percentage Rates in American Basketball Leagues: A Gender-Centric Examination of WNBA and NBA Teams. E-Balonmano Com Rev. Cienc. Deporte 2025, 21, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, A.; Alonso-Pérez-Chao, E.; Navarro Barragán, R.M.; Jiménez-Sáiz, S.L. Home-Court Advantage and Home Win Percentage in the NBA: An in-Depth Investigation by Conference and Team Ability. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R.; Gómez, M.A. Home Advantage Analysis in Different Basketball Leagues According to Team Ability. Iber. Congr. Basketb. Res. 2007, 4, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, M.A.; Paredes, V.; Comfort, P.; Jiménez-Ormeño, E.; Areces-Corcuera, F.; Giráldez-Costas, V.; Gallo-Salazar, C.; Alonso-Aubín, D.A.; Menchén-Rubio, M.; McMahon, J.J. “You Are Not Wrong About Getting Strong:" An Insight into the Impact of Age Group and Level of Competition on Strength in Spanish Football Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2024, 19, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, R. Worldwide Regional Variations in Home Advantage in Association Football. J. Sports Sci. 2006, 24, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leota, J.; Hoffman, D.; Mascaro, L.; Czeisler, M.E.; Nash, K.; Drummond, S.P.A.; Anderson, C.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Facer-Childs, E.R. Home Is Where the Hustle Is: The Influence of Crowds on Effort and Home Advantage in the National Basketball Association. J. Sports Sci. 2022, 40, 2343–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdas, D.I.; Mitrousis, I.; Zacharakis, E.D.; Travlos, A.K. Home-Audience Advantage in Basketball: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in EuroLeague Games During the 2019–2021 COVID-19 Era. J. Phys. Educ. Sport 2022, 22, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, S.; Gasperi, L.; Robertson, S.; Ruano, M.A.G. Rest or Rust? Complex Influence of Schedule Congestion on the Home Advantage in the National Basketball Association. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2023, 174, 113698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goumas, C. Home Advantage in Australian Soccer. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2014, 17, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, M.; Kocher, M.G. Favoritism of Agents—The Case of Referees’ Home Bias. J. Econ. Psychol. 2004, 25, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, W.; Weigelt, M.; Rein, R.; Memmert, D. How Does Spectator Presence Affect Football ? Home Advantage Remains in European Top-Class Football Matches Played Without Spectators During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).