Abstract

Phosphogypsum-based cemented paste backfill (PCPB) represents an effective solution for managing substantial accumulations of PG. However, its practical application is limited by excessive fluoride content and insufficient strength. To systematically investigate the influence of initial fluoride content on the hydration behavior, microstructures, and strength development of PCPB specimens, synthetic phosphogypsum was prepared using CaSO4·2H2O and NaF to eliminate impurity interference in this study. A series of specimens was designed with varying initial fluoride content (5–70 mg/L), sand-to-cement ratios (1:6, 1:8, 1:10), and concentrations (63 wt%, 65 wt%). Setting time, unconfined compressive strength, isothermal calorimetry, X-ray diffraction, and scanning electron microscopy were employed to elucidate the effects and underlying mechanisms of fluoride on PCPB performance. The results indicate that higher initial fluoride content markedly delayed setting and reduced early strength. Calorimetric analysis confirmed that fluoride postponed the exothermic peak and extended the induction period, primarily due to the formation of the CaF2 layer on clinker particle surfaces, which hindered nucleation and hydration. The microscopic results further revealed that high fluoride content suppressed the formation of ettringite and C-S-H gels, resulting in more porous and loosely bonded microstructures. Leaching tests indicated that fluoride immobilization in PCPB specimens occurred mainly through CaF2 precipitation, physical encapsulation, and ion exchange. These findings provide theoretical support for the fluoride thresholds in PG below which the adverse effects on cement hydration and strength development can be minimized, contributing to the sustainable goals of waste reduction, harmless disposal, and resource recovery in the phosphate industry.

1. Introduction

Phosphogypsum (PG) is the primary by-product of wet-process phosphoric acid production, consisting mainly of gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) alongside fluorides, phosphates, and trace metallic impurities [1,2,3]. With the rapid growth of the global phosphate fertilizer industry, approximately 300 million tons of PG are generated annually worldwide, of which more than 100 million tons originate from China [4,5]. However, less than 15% of the total PG produced is recycled into building materials, soil conditioners, or cement retarders [6,7]. Most PG is directly stockpiled in large open-air impoundments, occupying vast land areas and posing serious risks to groundwater and surrounding ecosystems due to its acidic components and the leaching of phosphorus and fluoride [8,9]. Therefore, the efficient and sustainable reuse of PG has become a key focus in solid waste management and green mining development.

In recent years, the utilization of PG in cemented paste backfill has emerged as a promising approach that combines waste recycling with mine stability control [10,11,12,13]. This technology involves mixing PG, cementitious materials (typically ordinary Portland cement, (OPC)), and water to produce a slurry that is pumped into underground voids or open pits [14,15]. However, the high fluoride content in PG could significantly delay setting time, inhibit cement hydration, and cause continuous leaching of fluoride, posing long-term risks to groundwater quality [16,17]. Moreover, untreated PG exhibits low reactivity with OPC, resulting in inadequate early strength that often fails to meet the engineering requirements of mine backfill operations [16,18]. To compensate for this deficiency, higher OPC content is typically employed, but this significantly elevates both mining costs and environmental burden, thereby limiting large-scale PG utilization.

Achieving a balance between mitigating the risks of fluoride pollution and minimizing production costs is therefore essential to maximize the sustainability of PG-based cemented paste backfill (PCPB) [19,20]. Previous studies have shown that replacing OPC with industrial byproducts (such as ground granulated blast furnace slag, steel slag, and fly ash) can effectively reduce both cost and carbon emissions [20,21,22,23]. However, in practical engineering applications, adjusting factors such as the sand-to-cement ratios and concentration to reduce cement content remains the most commonly employed approach [24,25]. Furthermore, extensive research exists on reducing fluoride concentrations in PCPB leachate to mitigate environmental impacts. Chen et al. [26] demonstrated that alkaline washing pretreatment effectively immobilized fluoride while maintaining mechanical strength. Similarly, other studies have shown that introducing polyaluminum chloride could reduce fluoride concentration in leachates and promote early hydration by accelerating the formation of hydration products [27]. However, given the complex and uncontrollable nature of impurities in PG, it is challenging to definitively elucidate the influence of fluoride on hydration kinetics, mineral phase, and fluoride immobilization mechanisms.

To overcome these limitations, this study synthesized PG from pure CaSO4·2H2O and NaF to eliminate interference from phosphates and organic impurities. The effects of initial fluoride content on the hydration behavior, strength development, and microstructural evolution of PCPB specimens were systematically investigated. Experimental parameters included varying initial fluoride contents (5–70 mg/L), sand to cement ratios (1:6, 1:8, 1:10), and concentrations (63 wt% and 65 wt%). Setting time, unconfined compressive strength (UCS), isothermal calorimetry, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses were conducted to elucidate the mechanisms governing hydration and fluoride immobilization. The findings provide a theoretical foundation for the fluoride thresholds in PG below which the adverse effects on cement hydration and strength development can be minimized, contributing to the sustainable goals of waste reduction, harmless disposal, and resource recovery in the phosphate industry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

To eliminate the influence of impurities commonly found in natural PG and quantitatively investigate the effect of initial fluoride content on the performance of PCPB specimens, synthetic PG was prepared using analytical-grade calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O, >99%, Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) and sodium fluoride (NaF, >98%, Hangzhou Westlake Chemical Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China). The OPC (P.O 42.5) supplied by Conch Cement Co., Ltd. (Wuhu, China) was used as the primary cementitious material. Deionized water was provided by South China High-Tech Water Treatment Equipment Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China).

2.2. PCPB Preparation

The initial fluoride contents in the synthetic PG were determined based on field measurements from a phosphate mine in Guizhou, China, where fluoride leaching concentrations ranged from 12 to 61 mg/L. To efficiently investigate the influence of fluoride content on PCPB performance while limiting experimental cost and workload, five representative fluoride levels (5, 10, 30, 50, and 70 mg/L) were selected to cover and extend the observed field distribution. To further examine the coupled effects of fluoride concentration and cement hydration, a structured experimental design was adopted by varying the sand-to-cement ratios (1:6, 1:8, and 1:10) and concentrations (63 wt% and 65 wt%). This factorial combination enables systematic evaluation of the main factors and their interactions while minimizing the number of required experiments. The detailed mix proportions are summarized in Table 1. Each specimen was labeled using the notation “C3S6F5,” where “C3” represents a concentration of 63 wt%, “S6” denotes a sand-to-cement ratio of 1:6, and “F5” indicates an initial fluoride content of 5 mg/L. The same naming convention applies to other combinations.

Table 1.

The mix proportions of PCPB specimens.

Based on prior research [28], the synthetic PG was first prepared with the designated fluoride content and then mixed with OPC according to Table 1. The mixture was stirred with deionized water for 5 min to form a homogeneous slurry, which was then poured into cylindrical molds (50 mm in diameter and 100 mm in height). The specimens were cured at 20 ± 1 °C and 90 ± 2% relative humidity.

2.3. Analytical Method

Setting times were measured according to the Chinese standard GB/T 1346-2024 [29]. The initial setting time was determined when the penetration depth of the needle was approximately 4 mm from the base, measured at 5 min intervals, while the final setting time was recorded when the needle failed to leave a visible mark on the specimen, checked every 15 min [30].

Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) tests were conducted at curing times of 7, 14, and 28 d using a microcomputer-controlled universal testing machine (SANS-YAW4305, Jinan, China) at a loading rate of 0.1 mm/min [31]. The reported UCS values represent the average of three specimens.

The mineralogical composition of the PCPB specimens was analyzed using XRD (D8 Advance, Bruker, Bremen, Germany). The hydration heat evolution within the first 70 h was monitored by isothermal calorimetry (TAM Air, Jiangcheng Precision Instruments Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China). The microstructures of PCPB specimens were observed using scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS, Tescan Mira3, TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic) [32].

The fluoride leaching concentrations in PCPB specimens were determined following the GB 5086.1-1997 [33].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Setting Time

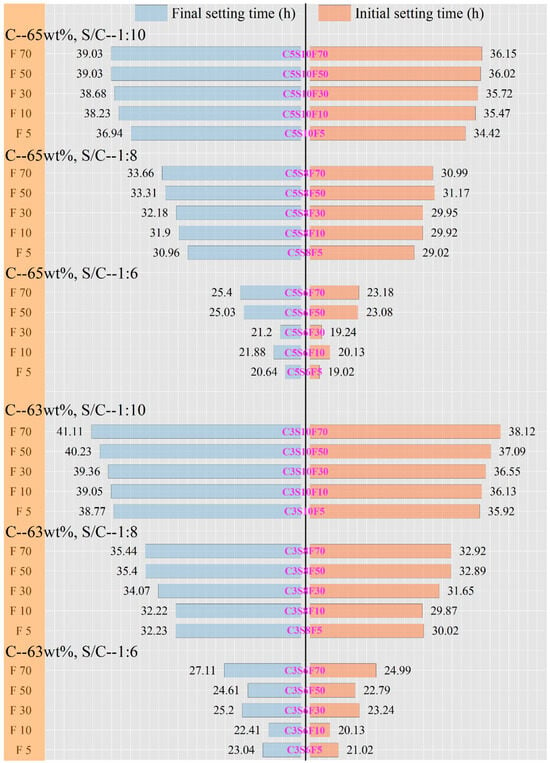

The setting time is a crucial parameter of the early hydration behavior of PCPB specimens and provides important insights into their early strength development. The setting time results of the PCPB specimens are presented in Figure 1. It can be observed that C5S6F5 exhibited the shortest setting time, with initial and final setting times of 19.02 h and 20.64 h, respectively. In contrast, C3S10F70 showed the longest setting time, with initial and final setting times of 38.12 h and 41.11 h, respectively. This pronounced delay can be attributed to the combined effects of the lower cement content and the highest fluoride content, both of which suppress cement hydration [22]. Furthermore, at a sand-to-cement ratio of 1:6, the PCPB specimens exhibited the shortest times to reach both initial and final setting among the three ratios. This may be attributed to the higher ratio diluting the paste and accelerating ion diffusion, thereby accelerating hydration reactions [4]. Under identical sand-to-cement ratios, the setting times of PCPB specimens with different concentrations were relatively similar, consistent with their mechanical strength results. Concurrently, as both the sand-to-cement ratio and concentration decrease, the reduced cement content in the slurry prolonged the setting time of the PCPB specimens. Interestingly, compared to C5S6F5, C5S6F70 exhibited initial and final setting times of 23.18 h and 25.4 h, respectively. This may be attributed to the reduced fluoride content, which mitigates the inhibitory effect of fluoride on cement hydration, thereby accelerating the setting process and enhancing early strength development in PCPB specimens.

Figure 1.

The setting times of the PCPB specimens.

3.2. Mechanical Properties

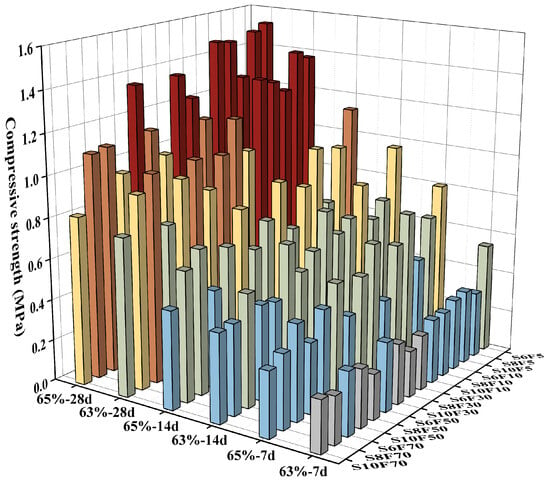

Figure 2 presents the overall strength of the PCPB specimens, with red columns indicating specimens with strength values ranging from 1.2 to 1.6 MPa, which were predominantly associated with specimens containing lower initial fluoride concentrations. Overall, the strength of PCPB specimens increased steadily with higher concentration, lower sand to cement ratios, and reduced initial fluoride content. However, only certain specimens met the strength requirements for practical mine backfilling applications. To better illustrate the relationships among curing times, concentration, sand-to-cement ratios, and initial fluoride content, the strength values and strength contribution rate were analyzed at different curing times. The strength contribution rate represents the proportion of strength gained within specific curing intervals relative to the strength of the PCPB specimens cured for 28 d.

Figure 2.

The overall strength of the PCPB specimens.

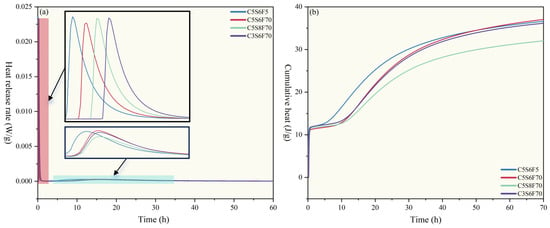

Figure 3 shows the strength and strength contribution rates of the PCPB specimens at different curing times. The strength contribution ratio denotes the percentage of strength gain in specimens cured for different curing intervals relative to the strength of PCPB specimens cured for 28 d. It can be observed that the strength of the PCPB specimens consistently increased with decreasing initial fluoride content across 7, 14, and 28 d. Strength also exhibited a positive correlation with both curing times and cement content. At a concentration of 63 wt%, only the C3S6F5 cured for 7 d demonstrated a notably higher strength (0.538 MPa), while other specimens showed minimal strength differentiation. In contrast, the strength variation in specimens at 65 wt% showed an inverse correlation with fluoride content, and the corresponding strength contribution rates were generally higher than those of the 63 wt% (Figure 3b). Since no other impurities in the PCPB specimens were present, the observed delay in strength development can be attributed primarily to the retarding effect of fluoride on the hydration reaction.

Figure 3.

The strength and strength contribution rates of PCPB specimens at different curing times. (a) The strength of specimens cured for 7 d, (b) Strength contribution rates during the 0–7 d, (c) The strength of specimens cured for 14 d, (d) Strength contribution rates of PCPB specimens during the 7–14 d, (e) The strength of specimens cured for 28 d, (f) Strength contribution rates of PCPB specimens during the 14–28 d.

The strength of the 63 wt% PCPB specimens cured for 14 d gradually approached that of the 65% PCPB specimens, reaching 0.432–0.963 MPa (Figure 3c). As shown in Figure 3d, the strength contribution rate of the 63% PCPB specimens was significantly higher than that of the 65% specimens during the 7–14 d curing period, with C3S6F30 reaching the highest contribution of 44%. Moreover, the contribution rate of the 63 wt% specimens declined as the cement content decreased, suggesting that the retarding effect of fluoride becomes more pronounced when less cement is available to buffer its effects.

The strength among PCPB specimens cured for 28 d became more pronounced, indicating that fluoride content increasingly influenced later strength development of the PCPB specimens. As shown in Figure 3f, PCPB specimens with higher initial fluoride content exhibited strength contribution rates exceeding 40% during the 14–28 d, confirming that the retarding effect of fluoride primarily affects the early hydration stage. As hydration time extends, the retarding effect of fluoride gradually diminishes, while the contribution of cement content to the strength development of the PCPB specimens increases further.

Additionally, it was observed that the C5S6F5 consistently exhibited optimal mechanical properties across all curing times. Interestingly, as the initial fluorine content increased, the C5S6F70 also demonstrated a favorable trend in strength development. Based on these results, C5S6F5 and C5S6F70 were selected for detailed analysis of early hydration behavior, mineral phases, and microstructure of the specimens. Building upon this foundation, the C5S8F70 and C3S6F70 specimens were selected through a controlled variable method to further analyze the influence of cement content on the strength development of the specimens.

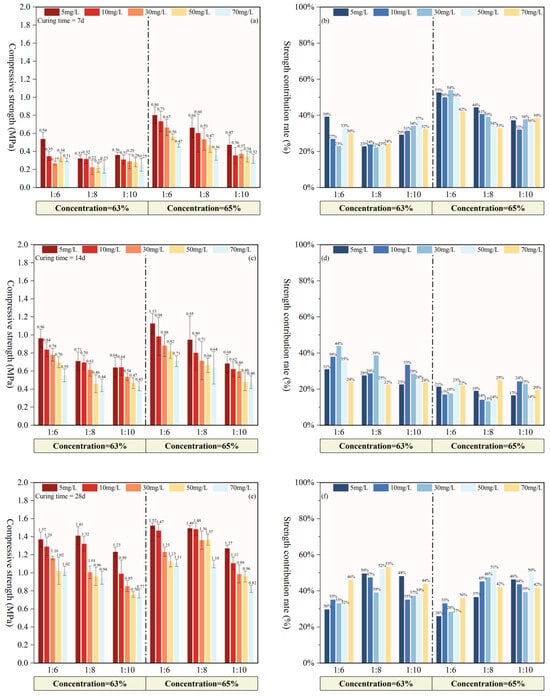

3.3. Analysis of Early Hydration Kinetics

Figure 4 presents the heat release rate and cumulative heat of the PCPB specimens during the first 70 h, and the corresponding characteristic parameters are summarized in Table 2. Overall, the hydration profiles of all PCPB specimens exhibited the typical heat evolution pattern observed in conventional cementitious materials, regardless of initial fluorine content and cement content variations. During the initial dissolution stage, the C5S6F70 showed a significantly lower heat release rate than C5S6F5, with a clear delay in the appearance of the exothermic peak. This confirmed that higher fluoride contents markedly retarded the initial hydration of cement. The delay is likely due to the endothermic precipitation of CaF2, which consumed heat and formed a surface film that inhibited further hydration until dissolution equilibrium was reached. Moreover, a similar delay was observed in the C5S8F70 and C3S6F70, with the most pronounced effect in C3S6F70, likely due to the higher water and gypsum contents enhancing fluoride solubility and CaF2 formation.

Figure 4.

(a) Heat release rate measured for the PCPB specimens. (b) Cumulative heat measured for the PCPB specimens.

Table 2.

Hydration heat characteristic parameters of the PCPB specimens.

In the induction stage, the C5S6F5 exhibited a much shorter induction period (3.3 h) compared to approximately 8–9 h for the other specimens, indicating that reducing the initial fluoride content substantially shortened the hydration induction period of the PCPB specimens. The remaining specimens showed noticeable fluctuations in heat flow before the end of the induction phase, which may be associated with variations in fluoride content caused by differences in cement content.

During the acceleration stage, fluoride content exerted a greater influence on the timing of the second exothermic peak than cement content. The C5S6F5 reached its second peak at 10.05 h with a maximum heat flow of 0.00027 W/g, indicating that lower initial fluoride content enhanced the specimen hardening rate, consistent with the setting time results. In contrast, C5S6F70 exhibited a slightly higher peak value, possibly due to ionic exchange between fluoride and hydration products. The C5S8F70 displayed the latest and weakest exothermic peak, primarily due to its lower cement content. During the deceleration and stabilization stages, the heat flow curves of all specimens showed no significant trend differences. However, after approximately 50 h, the cumulative heat of C5S6F70 began to increase gradually, reaching a maximum of 37.27 J/g, suggesting that higher fluoride content may promote the late hydration of C4AF in the cement clinker.

In summary, the initial fluoride content directly affected the initial dissolution and induction stages of PCPB specimens, while cement content influenced the process indirectly by modulating the available fluoride content in the system [34]. Higher fluoride contents delayed both the initial hydration and induction stages, whereas increasing the cement content promoted fluoride immobilization during early hydration, effectively reduced free fluoride concentration, and shortened the induction period, thereby accelerating the overall hydration process.

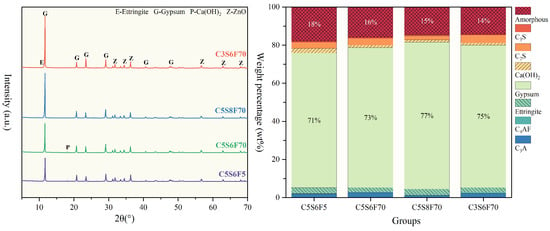

3.4. XRD Analysis

Figure 5 presents the mineral composition and corresponding contents of the PCPB specimens cured for 28 d. The primary clinker phases of OPC (C2S, C3S, C3A, and C4AF) were still detected in all specimens, indicating that the hydration process was partially delayed by the presence of fluorides. Ettringite (AFt), mainly formed from the hydration of C3A, was identified as the dominant early hydration product contributing to strength development [35,36]. Ca(OH)2 and C-S-H gels were also observed as typical hydration products of C2S and C3S, with the amorphous phase fraction representing the amounts of C-S-H gels [37,38]. Notably, significant differences were observed between C5S6F5 and C5S6F70 in terms of the amorphous phase, Ca(OH)2, and AFt contents. The reduced formation of these phases in C5S6F70 suggested that higher initial fluoride contents inhibited cement hydration, consistent with the observed reduction in mechanical properties. Moreover, the higher residual C3A content in C5S6F70 indicates that fluoride hindered the hydration of C3A, explaining the lower early strength of the specimen. In contrast, both C5S8F70 and C3S6F70 exhibited lower amorphous contents than C5S6F70, suggesting that increasing cement content could partially mitigate the retarding effect of fluoride, thereby enhancing the content of hydration products within the specimens and further supporting strength development. No distinct diffraction peaks corresponding to crystalline fluoride-bearing phases were detected in any of the PCPB specimens. This absence may be attributed to their low contents or to the physical immobilization of fluoride within amorphous hydration products.

Figure 5.

Mineral composition and corresponding contents of the PCPB specimens cured for 28 d.

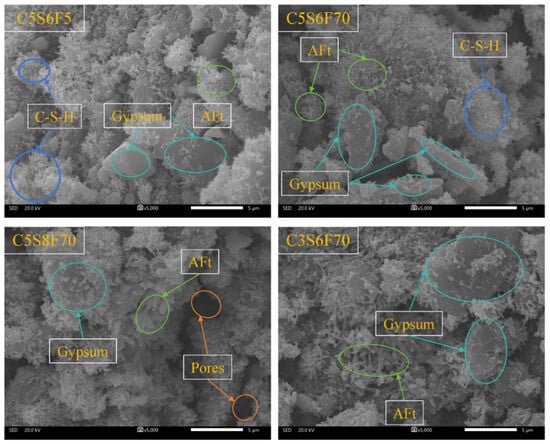

3.5. Microstructural Analysis

Figure 6 shows the microstructural morphology of the PCPB specimens cured for 28 d. A large number of hydration products, primarily C-S-H gels and AFt, were observed along with residual gypsum and visible pore structures in the PCPB specimens. The C5S6F70 exhibited a relatively loose microstructure with numerous large pores on the surface, indicating incomplete hydration under the high-fluoride environment. In contrast, the C5S6F5 displayed a denser morphology, where interwoven clusters of AFt needles and C-S-H gels formed a compact, continuous microstructure. The heterogeneous distribution of hydration products in C5S6F70, with localized dense and porous regions, likely caused internal volume fluctuations and microcracking, contributing to its lower compressive strength. Compared to the C5S6F70, both C5S8F70 and C3S6F70 showed more dispersed hydration products alongside a higher abundance of large pores. Moreover, larger gypsum crystals are discernible in both C5S8F70 and C3S6F70, indicating that, under identical initial fluoride content conditions, cement content directly influences the early hydration reaction and strength development of the PCPB specimens. While the granular crystals were occasionally observed on the surfaces of the PCPB specimens, likely corresponding to CaF2 crystals embedded within gypsum crystals or denser hydration products [39,40].

Figure 6.

The microstructural morphology of the PCPB specimens cured for 28 d.

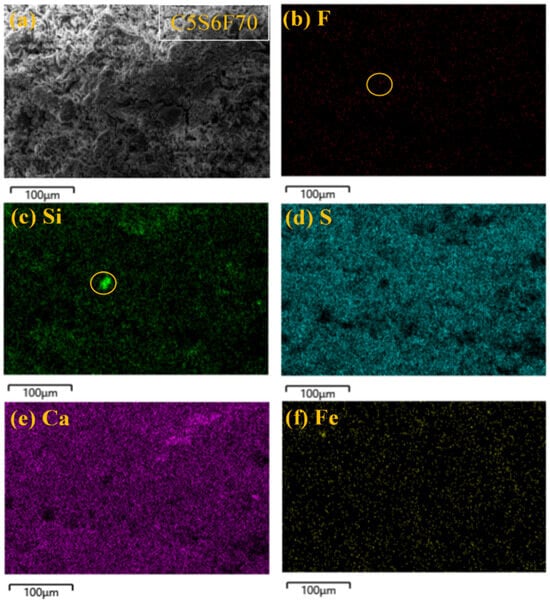

As shown in Figure 7, elemental distribution within the C5S6F70 revealed dense distributions of Ca and S, confirming the presence of residual gypsum. The regions marked by yellow circles exhibited distinct Si enrichment accompanied by localized slight F enrichment, suggesting partial ion exchange between F and the structure of C-S-H gels. This indicates that fluoride may be incorporated within C-S-H gels or at their interface with gypsum, forming complex composite microstructures [41]. Furthermore, partial overlap between F and Ca signals supported CaF2 precipitation as one of the primary fluoride immobilization mechanisms. The co-localization of Fe and F also suggested that hydration of C4AF under high-fluoride conditions facilitated fluoride immobilization through the formation of the complexes [42].

Figure 7.

The elemental distribution within the C5S6F70 cured for 28 d.

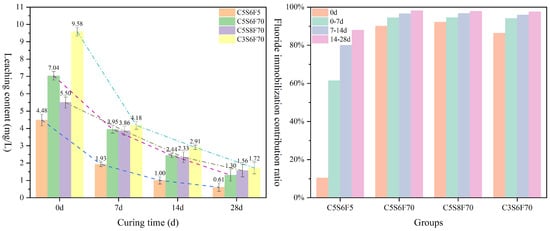

3.6. Fluoride Leaching Behavior

Figure 8 presents the fluoride leaching concentrations and corresponding immobilization contribution rates of the PCPB specimens cured for different times. The fluoride concentrations of C5S6F70 and C3S6F70 at 0 d were 7.035 and 9.579 mg/L, respectively, corresponding to immobilization contribution rates of 90% and 86%. This indicates that higher concentrations promoted fluoride immobilization in PCPB specimens. Furthermore, the fluoride immobilization contribution rates exhibited a decreasing trend across the three intervals of 0–7 d, 7–14 d, and 14–28 d as the hydration reaction progressed, which suggested that the fluoride immobilization capacity of the PCPB specimens became increasingly limited. Nevertheless, throughout the entire hydration process, the PCPB specimens achieved over 90% fluoride immobilization within the first 7 d, potentially attributable to CaF2 precipitation formation.

Figure 8.

The fluoride leaching concentrations and corresponding immobilization contribution rates of the PCPB specimens.

Interestingly, the C5S8F70 exhibited a lower initial fluoride concentration (5.496 mg/L at 0 d) compared with C5S6F70, seemingly contradicting the expectation that higher cement content would reduce fluoride leaching. However, the fluoride concentration in C5S6F70 cured for 28 d had dropped below that of C5S8F70, which may be attributed to the lower gypsum content in C5S6F70, initially limiting CaF2 precipitation and resulting in higher early fluoride leaching. As the hydration reaction progressed, the increased cement content in C5S6F70 facilitated more stable fluoride immobilization during later curing stages. In contrast, the C5S6F cured for 28 d exhibited a low fluoride concentration of 0.607 mg/L, yet its fluoride immobilization contribution rate reached only 87.86%, likely due to its lower initial fluoride content and relatively compact microstructure.

Combining insights from hydration heat, mineral phase, and microstructural analyses, it is evident that OPC contributed to fluoride immobilization during hydration. This process is closely related to the retardation effect of fluoride on cement hydration. During the initial hydration stage, dissolution of synthetic PG releases abundant fluoride, which rapidly reacts with Ca to form CaF2 precipitates [20]. These precipitates tended to deposit on the surface of unhydrated clinker particles, impeding water penetration and delaying hydration. The early hydration is dominated by C3A, and the results indicated that lower fluoride contents enhanced C3A reactivity, promoting early strength development [43,44]. As hydration progressed, newly formed products such as AFt progressively encapsulated CaF2 precipitates, leading to physical encapsulation of fluoride.

Meanwhile, the C-S-H gels generated by the hydration reactions of C2S and C3S are the primary contributors to strength development. According to double-layer and zeta potential theories, C3S experienced distinct induction and acceleration stages during early hydration [45]. However, as hardening and setting progressed, C-S-H gels and Ca(OH)2 crystals accumulated on particle surfaces, reducing the hydration rate. The observed variations in strength across different fluoride contents suggested that excessive fluoride content inhibited the hydration reactions, likely due to the adsorption of CaF2 precipitates on unhydrated clinker surfaces, hindering the acceleration of C3S and C2S reactions.

During the later hydration stages, abundant C-S-H gels provided potential sites for ion exchange, allowing residual fluoride to be incorporated into silicate chains, further contributing to chemical immobilization. Furthermore, the greater consumption of C4AF in high-fluoride conditions indicated its participation in fluoride immobilization [46,47]. The hydration products of C4AF may undergo secondary hydrolysis in saturated CaF2 environments, forming complex compounds that further immobilize fluoride.

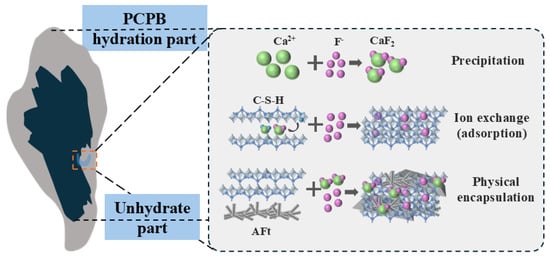

Based on the leaching and microstructural analyses, precipitation dominated during the early hydration period. Gypsum served as the main Ca2+ source, with specimens containing lower cement content tending to exhibit higher early fluoride immobilization efficiencies due to greater gypsum availability. However, the resulting CaF2 precipitates could extensively adhere to unhydrated clinker surfaces, impeding further hydration and slowing the overall reaction rate [48]. As shown schematically in Figure 9, physical encapsulation occurred primarily during the early and intermediate hydration stages. Once CaF2 precipitation reached equilibrium, these deposits became coated by new hydration products, leading to the physical immobilization of fluoride [44,49]. Additionally, fluoride may also be trapped within gypsum crystals or adsorbed onto hydration products through ion exchange, forming complex fluoride-bearing compounds [50].

Figure 9.

The fluoride immobilization mechanisms of the PCPB specimens.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically investigated the influence of initial fluoride content, sand-to-cement ratios, and concentration on the hydration behavior, strength development, and microstructural evolution of the PCPB specimens. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Effect of fluoride on hydration and strength: Lower initial fluoride content weakened the inhibitory effect of fluoride on cement hydration, resulting in superior early strength of the PCPB specimens. The strength contribution analysis further confirmed that increasing cement content effectively mitigated the negative impact of fluoride, leading to enhanced overall strength development.

- (2)

- Hydration behavior and phase evolution: Isothermal calorimetry demonstrated that higher fluoride content intensified the retardation effect on hydration, as evidenced by delayed exothermic peaks and prolonged induction periods. This was primarily attributed to the early formation of CaF2 precipitates, which adhered to clinker surfaces and hindered nucleation. XRD results revealed significantly reduced C4AF content and elevated C3A content in the C5S6F70, suggesting that CaF2 precipitation suppressed the rapid hydration of C3A while promoting the later hydration of C4AF. This explained the slower strength development observed in high-fluoride conditions.

- (3)

- Microstructural characteristics: SEM showed that elevated fluoride content inhibited hydration product formation, leading to a more porous and loosely packed microstructure. And the specimens with high fluoride content exhibited heterogeneous distributions of hydration products and more pronounced porosity. EDS results revealed overlapping distributions of F and Fe, as well as local enrichment of Ca, Si, and F, indicating that fluoride participated in ion exchange with C-S-H gel structures.

- (4)

- Fluoride immobilization mechanisms: Fluoride leaching results demonstrated that increasing cement content significantly reduced the fluoride concentration in leachates. The fluoride immobilization contribution analysis indicated that OPC hydration primarily contributed to fluoride immobilization during the middle and later stages. Fluoride immobilization in PCPB specimens occurred mainly through three mechanisms: CaF2 precipitation, physical encapsulation, and ion exchange with hydration products.

Future research should focus on the long-term evolution of internal microstructures, the effects of aggressive degradation and end-of-life scenarios, and the stability and mobility of immobilized contaminants. In addition, it is essential to evaluate more aggressive degradation and end-of-life scenarios, such as cyclic wetting–drying, chemical erosion, mechanical disturbance, or carbonation-induced phase transformations. Furthermore, future work should further explore the variability of industrial PG and the reproducibility of material performance under different sources and processing conditions. The behavior of PCPB specimens under fire exposure should also be investigated, as fire represents a new and emerging challenge for backfill materials. These investigations will provide more reliable guidance for practical applications and optimization of the PCPB specimens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L., D.W., Y.F. and Q.C.; Methodology, B.L., Y.Y. and Q.C.; Formal analysis, Q.Z. and D.W.; Resources, Y.F.; Data curation, B.L. and Y.Y.; Writing—original draft, B.L.; Writing—review and editing, Q.C.; Visualization, Q.Z.; Supervision, Q.Z., D.W. and Y.F.; Funding acquisition, D.W. and Q.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52274151 and 52474165), China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (No. BX20250036), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2025M771797).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yikun Yang was employed by the company Guang Zhou Baiyun International Airport Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Cai, Q.; Jiang, J.; Ma, B.; Shao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Qian, B.; Wang, L. Efficient removal of phosphate impurities in waste phosphogypsum for the production of cement. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 780, 146600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.P.; de Medeiros, M.H.G.; de Castro Carvalho, I.; Suzuki, S.; Kirchheim, A.P. Optimizing phosphogypsum neutralization for enhanced setting regulation in Portland cement matrices. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 46, e01681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiusong, C.H.E.N.; Aixiang, W.U. Research Progress of Phosphogypsum-based Backfill Technology. Chin. J. Eng. 2025, 47, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, H.; Zheng, L.; Wang, K.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Feng, H. Utilization of waste phosphogypsum to prepare hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and its application towards removal of fluoride from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 241, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernysh, Y.; Yakhnenko, O.; Chubur, V.; Roubik, H. Phosphogypsum Recycling: A Review of Environmental Issues, Current Trends, and Prospects. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumanis, G.; Vaiciukyniene, D.; Tambovceva, T.; Puzule, L.; Sinka, M.; Nizeviciene, D.; Fornés, I.V.; Bajare, D. Circular Economy in Practice: A Literature Review and Case Study of Phosphogypsum Use in Cement. Recycling 2024, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbaya, H.; Jraba, A.; Khadimallah, M.A.; Elaloui, E. The Development of a New Phosphogypsum-Based Construction Material: A Study of the Physicochemical, Mechanical and Thermal Characteristics. Materials 2021, 14, 7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, M.Y.J.; Su, C.; Talpur, S.A.; Iqbal, J.; Bajwa, K. Arsenic Removal from Groundwater Using Iron Pyrite: Influence Factors and Removal Mechanism. J. Earth Sci. 2023, 34, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.J.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, F.J.; Yu, W.J.; Yin, Z.G.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Chi, R.A.; Zhou, J.C. The Impurity Removal and Comprehensive Utilization of Phosphogypsum: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.L.; Ke, Y.X.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, Q.L.; Xiao, C.C.; He, F.J.; Yu, Q. Cost-Effective Treatment of Hemihydrate Phosphogypsum and Phosphorous Slag as Cemented Paste Backfill Material for Underground Mine. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 2019, 9087538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Wu, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. Determination of utilization strategies for hemihydrate phosphogypsum in cemented paste backfill: Used as cementitious material or aggregate. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 308, 114687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stukhlyak, P.D.; Buketov, A.V.; Panin, S.V.; Maruschak, P.O.; Moroz, K.M.; Poltaranin, M.A.; Vukherer, T.; Kornienko, L.A.; Lyukshin, B.A. Structural fracture scales in shock-loaded epoxy composites. Phys. Mesomech. 2015, 18, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, Y.; Wang, D.; Lu, R.; Na, Q.; Chen, Q. Low-foam-rate expansive cemented paste backfill for facilitating active roof-contact: Correlation mechanisms between expansion properties and mechanical properties. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 113, 114063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, J.; Gao, L.; He, S.; Gan, L.; Sun, C.; Shi, Y. Immobilization of phosphogypsum for cemented paste backfill and its environmental effect. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Ma, L.; Li, K.; Du, W.; Hou, P.; Dai, Q.; Xiong, X.; Xie, L. Preparation of phosphogypsum-based cemented paste backfill and its environmental impact based on multi-source industrial solid waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 404, 133314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Zhou, S.T.; Zhou, Y.N.; Min, C.D.; Cao, Z.W.; Du, J.; Luo, L.; Shi, Y. Durability Evaluation of Phosphogypsum-Based Cemented Backfill Through Drying-Wetting Cycles. Minerals 2019, 9, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Q. A new strategy for preparing cemented paste backfill using red mud neutralized by phosphogypsum: Mechanical properties, hydration mechanism and production cost. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 392, 126758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, Z. Investigation on phosphogypsum–steel slag–granulated blast-furnace slag–limestone cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1296–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, A.; Ruan, Z.; Bi, C.; Li, Y. Water resistance and hydration mechanism of phosphogypsum cemented paste backfill under composite curing agent modification. Environ. Res. 2025, 286, 122797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.D.; Pan, R.X.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Q.L.; Yang, M. Study on application and environmental effect of phosphogypsum-fly ash-red mud composite cemented paste backfill. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 108832–108845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cho, D.W.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Cao, X.; Hou, D.; Shen, Z.; Alessi, D.S.; Ok, Y.S.; Poon, C.S. Green remediation of As and Pb contaminated soil using cement-free clay-based stabilization/solidification. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 336–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ding, H.; Qiu, J.; Guo, Z. Recycling flue gas desulfurisation gypsum and phosphogypsum for cemented paste backfill and its acid resistance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 275, 122170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, B.; Masiero Gil, A.; Longhi Bolina, F.; Fonseca Tutikian, B. Thermal damage evaluation of full scale concrete columns exposed to high temperatures using scanning electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction. Dyna 2018, 85, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhao, L.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Wu, A.; He, Y.; Cheng, H.; Sun, W.; Li, H. A systematic review of cemented paste backfill technology for cleaner and efficient utilization of phosphogypsum in China. Miner. Eng. 2025, 231, 109468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, N.; Qiusong, C.; Wu, A. Precise and Non-destructive Approach for Identifying the Real Concentration Based on Cured Cemented paste Backfill Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y. Influence mechanism of alkaline environment on the hydration of hemihydrate phosphogypsum: A comparative study of various alkali. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 353, 129070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, W.; Zou, L.; Chi, R. Investigation of the mechanism of soluble fluoride removal from phosphogypsum leachate using polyaluminium chloride flocculation: A molecular dynamics approach. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 718, 136822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Yang, Y.K.; Wang, D.L.; Liu, B.; Feng, Y.; Song, Z.; Chen, Q.S. Assessing Fluoride Impact in Phosphogypsum: Strength and Leaching Behavior of Cemented Paste Backfill. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1346-2024; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Standard Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF.aspx/GBT1346-2024?English_GB/T%201346-2024 (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Li, Z.; Niu, R.; Xie, G.; Zhang, W.; Xing, F. Efflorescence and mitigation of red mud–fly ash–phosphogypsum multicomponent geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 448, 137869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Yuan, X.; Wu, A.; Liu, Y. Enhancing CO2 mitigation potential and mechanical properties of shotcrete in underground mining utilizing microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2024, 34, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.B.; Pachla, E.C.; Bolina, F.L.; Graeff, Â.G.; Lorenzi, L.S.; da Silva Filho, L.C.P. Mechanical and chemical properties of cementitious composites with rice husk after natural polymer degradation at high temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 85, 108716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5086.1-1997; Test Method Standard for Leaching Toxicity of Solid Wastes Roll Over Leaching Procedure. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1997. Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF/English.aspx/GB5086.1-1997?Redirect (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Hou, J.; He, X.; Ni, X. Hydration mechanism and thermodynamic simulation of ecological ternary cements containing phosphogypsum. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Preparation, characterization and application of red mud, fly ash and desulfurized gypsum based eco-friendly road base materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, T. In-depth insight into the cementitious synergistic effect of steel slag and red mud on the properties of composite cementitious materials. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, F.; Sun, Y. Innovative and sustainable filling materials from bauxite residue (red mud) and multiple industrial solid wastes. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukiza, E.; Liu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, N. Preparation and characterization of a red mud-based road base material: Strength formation mechanism and leaching characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 220, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, Y.S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Tong, L.; Hu, Q.; Dai, J.G.; Tsang, D.C.W. Stabilisation/solidification of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash by phosphate-enhanced calcium aluminate cement. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.H.; Zhang, P.Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.M.; Sun, Q.; Mao, Z.Y.; Wang, W.S.; He, T.S. Exploration on the occurrence state of fluorine in cement hydration products mixed with high fluorine alkali free liquid accelerator. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 3105–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.H.; He, T.S. Leaching behavior and environmental safety evaluation of fluorine ions from shotcrete with high-fluorine alkali-free liquid accelerator. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 11267–11280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisone, S.; Gautier, M.; Chatain, V.; Blanc, D. Spatial distribution and leaching behavior of pollutants from phosphogypsum stocked in a gypstack: Geochemical characterization and modeling. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 193, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.P.; Yin, S.H.; Chen, X.; Yan, R.F.; Chen, W. Effect of Alkali-Activated Slag and Phosphogypsum Binder on the Strength and Workability of Cemented Paste Backfill and Its Environmental Impact. Min. Metall. Explor. 2023, 40, 2411–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.B.; Zhou, Y.A.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Q.Q. Fluoride immobilization and release in cemented PG backfill and its influence on the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 869, 161548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, T.T.; Cheng, M.Q.; Zhang, L.P.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Z.Q.; Zhou, T.; Yang, J.Z.; Xiao, P.Y.; Huang, Q.F.; et al. Enhanced strength and fluoride ion solidification/stabilization mechanism of modified phosphogypsum backfill material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, C.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Lu, X. Improving the strength performance of cemented phosphogypsum backfill with sulfate-resistant binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Cruz, F.J.; Rosales, J.; Bolívar, J.P.; Ramos-Lerate, I.; Agrela, F.; Gázquez, M.J. Phosphogypsum leachate cleaning waste as partial cement replacement in mortars. Results Eng. 2025, 28, 107913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Zhao, L.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Cheng, H.; Sun, W.; Wu, A.; Chen, C. Immobilization of phosphorus and fluorine from whole phosphogypsum-based cemented backfill material with self-cementing properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tan, Y.; Ming, H.; Wang, C.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y. The synergistic effect of carbide slag and thermal treatment on immobilizing soluble phosphorus and fluoride in phosphogypsum. Waste Manag. 2026, 210, 115230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.A.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, Q.Q. Control of Fluoride Pollution in Cemented Phosphogypsum Backfill by Citric Acid Pretreatment. Materials 2023, 16, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).