Abstract

Phthalic acid esters (PAEs) are ubiquitous pollutants with reported endocrine-disruption and multiplex toxic activities in a wide range of invertebrate and vertebrate animals. In the present review, the molecular and physiological effects of phthalate exposure on invertebrates, as well as less characterized vertebrates such as amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, are thoroughly examined. PAEs induce a series of adverse effects, such as reproductive toxicity, oxidative stress, immune system impairment, and neuroendocrine disruption. The effects can extensively vary depending on the species, developmental stage, and environmental conditions, ranging from impaired hormone signaling, developmental malformations, and thyroid impairment in amphibians and reptiles to lipid metabolism disturbances and epigenetic changes in mammals. This review will place particular emphasis on transgenerational effects, mixture toxicity, and chronic low-level exposure. By integrating evidence from in vivo, in vitro, and omics studies, this review defines areas of knowledge gaps and the necessity to integrate these taxa in integrated ecological risk assessments, as well as regulatory policy.

1. Introduction

The phthalates, or phthalic acid esters (PAEs), are a class of ubiquitous chemicals employed both as plasticizers and non-plasticizers in numerous consumer products, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC); household appliances; medical equipment; construction materials (e.g., wall coatings and electrical cables); insecticides; packaging materials; pharmaceuticals; medical devices; dentures; children’s toys; automobiles; lubricants; waxes; cleaning materials; clothes; and personal care products (PCPs), such as facial cleansers, fragrances, soaps, lotions, and cosmetics [1]. Although no universally accepted classification exists, PAEs are generally categorized into low-molecular-weight (LMW) PAEs, which contain side chains with 3 to 6 carbon atoms, and high-molecular-weight (HMW) PAEs, characterized by side chains (R and R′) containing 7 to 13 carbon atoms [2]. Their primary function lies in improving product stability, flexibility, and durability [3]. In fact, PAEs possess a relatively high boiling point and low melting point, characteristics that make them particularly well-suited for applications as plasticizers, heat transfer fluids, and carriers in the polymer industry [2] (Table 1). During 2007–2018, the global consumption of plastic products led to a significant increase in PAE emissions, rising from over 3 million tons to 6 million tons per year, with China contributing 25% to 45% of total global emissions [3].

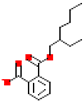

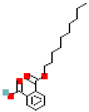

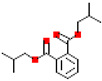

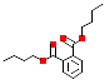

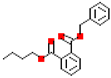

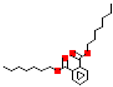

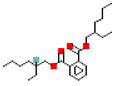

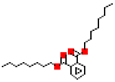

Table 1.

Most common phthalates (monoesters and diesters) cited in this review, along with their acronyms, molecular structures, molecular weight g/mol, and XLogP3.

The widespread use of PAEs in commercial products, in conjunction with their affinity for organic matter and their non-covalent bonds within matrices during mixing, renders them susceptible to leaching into surrounding environments. This has resulted in their pervasive detection in water bodies, sediments, soils, air, organisms, and landfill leachates [4].

Although it is widely accepted that the presence of phthalates in the environment primarily originates from anthropogenic sources, namely chemical synthesis and leaching from phthalate-containing materials, recent studies have highlighted the potential significance of biosynthetic contributions [5,6,7].

Various organisms, including plants, algae, bacteria, and fungi, are capable of producing phthalates as secondary metabolites. These compounds are typically synthesized to fulfil ecologically significant biological roles such as allelopathic or phytotoxic effects; antimicrobial activity, including both antibacterial and antifungal properties; insecticidal effects; and antioxidant functions, possibly through the shikimic acid pathway.

According to Semenov et al. [8], the production of phthalates by plants alone, as secondary metabolites, has been estimated to be approximately 36 times greater than the annual global industrial production, which amounted to 4.9 million tons in 2019. This estimation does not include the potential additional contributions from bacteria, fungi, and algae.

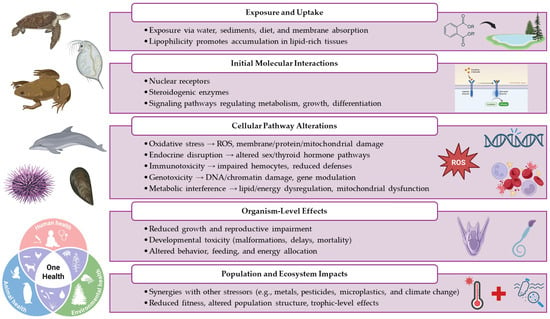

Concerns regarding phthalate esters arise from well-documented evidence of their toxicity in laboratory animals. Depending on the concentration, the chemical nature of the compound, environmental physicochemical conditions, and the exposed organism, PAEs can cause a wide range of acute and chronic toxic effects. These include immunotoxicity, metabolic toxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, genotoxicity, developmental toxicity, and other adverse health outcomes [9,10]. Figure 1 provides a concise overview of the primary toxic effects of PAEs, illustrating their logical flow and underlying mode of action.

Figure 1.

A schematic representation of the main toxic effects and the mode of action of PAEs. Created in BioRender.

Exposure to PAEs also affects the health and behavior of both adults and their offspring, inducing oxidative stress, neurodevelopmental disturbances, genetic alterations, and epigenetic reprogramming [11]. As endocrine-active substances (EAS), PAEs can interact with or disrupt normal hormonal functions. Depending on exposure levels and biological responses, they exhibit complex mechanisms of toxicity and are considered risk factors for a wide array of multifactorial diseases, including reproductive and respiratory disorders; developmental and embryogenic alterations, such as reduced egg-hatching success; metabolic syndromes; and tumor development [3,9]. In particular, phthalates can disrupt endocrine pathways and reprogram the epigenome of developing germ cells. The exposure to such molecular systems mediated via maternal-to-fetal exposure occurs across the placenta through passive diffusion, facilitated transport, and protein binding and after birth through breast milk [12,13]. The phthalates activate nuclear receptors like peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), estrogen receptors (ERs), and thyroid hormone receptors (THRs), thereby modifying hormone-sensitive gene networks and instigating stable epigenetic alterations, including DNA methylation and histone modifications. These changes can result in reproductive, metabolic, and neurodevelopmental abnormalities that persist into subsequent generations, indicating the heritable inheritance of phthalate-induced epimutations [14,15].

The fate and toxicity of PAEs are closely linked to the wide range of environmental and biological transformations they undergo across different compartments. These processes are influenced by the molecular structure and physicochemical properties of the specific PAEs; the chemical composition of the matrix in which they are found; and various environmental conditions, such as organic carbon content, pH, salinity, and enzyme activity.

PAEs are primarily degraded through hydrolysis, photodegradation, and microbial activity; however, abiotic degradation in natural environments is slow. Photolysis is more efficient in the gas phase, while hydrolysis becomes slower with longer alkyl chains. In aquatic systems, microbial degradation dominates but is constrained by environmental factors, resulting in half-lives ranging from years to centuries. PAEs can accumulate in aquatic organisms through ingestion; although they rarely biomagnify, they are generally metabolized into less toxic yet fat-storable compounds like MPE. Similar to other persistent organic pollutants (POPs), PAEs pose potential risks to the food chain, human health, and ecosystems [9].

The environmental and biological risks associated with PAEs are primarily linked to their high affinity for lipophilic media, facilitating interactions with cellular membranes. Their physicochemical characteristics, particularly a high octanol–water partition coefficient (log KOW), low vapor pressure, and very low volatility, promote their diffusion into aquatic environments and subsequent accumulation in the tissues of aquatic organisms [10]. The log KOW, reflecting the equilibrium distribution between octanol and water, is a key parameter used to estimate a compound’s hydrophobicity and predict its behavior in aqueous systems, biota, sediments, and soil organic matter. The estimated XLogP3 value, a computationally derived form of log KOW, further refines this prediction by accounting for molecular structure and substituent effects, offering a more accurate predictions than most of the other methods [16,17], and allowing us to assess a compound’s potential for bioaccumulation and environmental mobility.

Table 1 provides a synopsis of the chemical structure, molecular weight, and estimated XLogP3 value (obtained from PubChem, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 17 September 2025) of the most prevalent PAEs.

Multiple studies reporting PAE concentrations in freshwater and marine environments show how levels can vary widely with geographic location, season, local sources, and analytical approaches [18,19].

The contamination of phthalates in water is highest in China, the world’s major PAE producer, due to insufficient pollution control. For instance, in Xuanwu Lake, total PAE concentrations exceed 1000 μg L−1, with DBP at 800.95 μg L−1 and di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) at 1299.54 μg L−1 [10]. In Vietnam, wastewater samples were found with PAE concentrations ranging from 20.7 to 405 μg L−1 (mean/median: 121/115 μg L−1) [20]. Brazil and India also show severe levels, with DBP reaching 207.781 μg L−1 in Indian groundwater, and diethyl phthalate (DEP) reaching 248.65 μg L−1 in Brazil’s Lake Paranoá [10].

Currently, most PAE production occurs in developing countries like Brazil, China, and India [21]. As previously mentioned, DEHP in China was found to be 1000 times higher than that in other countries (1.3 μg L−1), including the United States [22]. Additionally, DEHP concentrations in aquatic environments of countries such as Korea, the United States, France, India, Israel, Spain, Kuwait, Iran, and the Netherlands have all exceeded 1.3 μg L−1, surpassing the EU’s environmental quality standards for priority substances [10]. Investigating phthalate concentrations in the Karst region of Puerto Rico, average total phthalate concentrations were found to be 5.08 ± 1.37 μg L−1, ranging from 0.093 to 58.4 μg L−1 [23].

Given their importance as plasticizers and potential environmental contamination, it was necessary to study their distribution in a river environment. Rivers in Southern India were therefore used as references. In this matrix, phthalates were quantified at an average concentration of 35.6 μg L−1 [24]. Considering the ubiquitous presence of phthalates and their common exposure events, it is crucial to perform accurate aquatic ecological risk assessments based on precise measurements of PAE concentrations and relevant toxicological parameters. In parallel, it is essential to develop and implement effective strategies to mitigate the environmental impact caused by PAE pollution.

Despite increasing regulatory measures in various countries, including bans and restrictions on specific phthalates, the global management of PAEs remains challenging. This is largely due to their environmental persistence and the complex, transboundary nature of global supply chains. Conventional remediation technologies, such as adsorption and advanced oxidation processes, are often limited by cost and treatment efficiency. Consequently, recent research has focused on environmentally sustainable alternatives, particularly microbial-based biodegradation methods that can effectively degrade phthalates under ambient environmental conditions [25].

The objective of this review is to provide an integrated synthesis of current knowledge on the toxicological impacts of phthalate esters and their metabolites in aquatic invertebrates and underrepresented vertebrate taxa, including amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. By integrating findings from in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo studies, this review aims to clarify the mechanisms of toxicity, highlight interspecies differences in sensitivity and response, and identify critical knowledge gaps essential for supporting environmental risk assessments.

2. Effects of PAEs on Biota

PAEs are generally metabolized in the body, primarily in two phases. In Phase I (hydrolysis), PAEs are converted into their main metabolite, monoalkyl phthalate esters (MPEs). In Phase II (conjugation), the monoester is transformed by P450 enzymes into oxidative metabolites, specifically hydrophilic glucuronide conjugates [10,26]. These metabolites are less toxic than their parent compounds [27], but they are fat-soluble, accumulating in animal-fat tissues for long periods [28]. MPE, for instance, can persist for up to 6 months and remains toxic to organisms [29], highlighting the importance of evaluating their toxicity.

To date, studies carried out both in vivo and in vitro have demonstrated that PAEs and their metabolites may influence the endocrine system, causing severe disfunction, such as infertility, and growth and developmental malformations and inhibition [19,30,31]. As observed by Mathieu-Denoncourt et al. [32], the toxicity of phthalates is affected by aromatic ring substitution, alkyl chain length, and metabolism.

Mathieu-Denoncourt et al. [32] observed that the toxicity (96 h LC50s) of phthalates was similar to that of aquatic invertebrates (0.46–377 mg L−1) and fish (0.48–121 mg L−1), and this toxicity appears to be highest around a log KOW of 6, which corresponds to the highest potential for bioconcentration and bioaccumulation.

In this review, we summarize the effects of PAEs on key aquatic organisms, including invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Table 2 provides an overview of the main effects reported across the studied species.

Table 2.

Reported effects of PAEs on aquatic invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals.

2.1. Invertebrates

PAEs exert adverse effects on aquatic invertebrates, largely by impairing immune, oxidative-stress, endocrine, and developmental pathways. Invertebrates rely on a multifaceted defense mechanism that includes physicochemical barriers, humoral responses, and cell-mediated immunity to protect against pathogens and environmental contaminants capable of disturbing cellular homeostasis [31,54]. Among the key cellular components of this system, hemocytes are considered the primary immune effectors. These cells are involved in crucial defense activities such as phagocytosis, encapsulation, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), secretion of cytokine-like molecules, synthesis of antimicrobial peptides, and activation of the phenoloxidase (PO) cascade [55,56,57].

2.1.1. Cladocera

The toxicological impact of PAEs has been widely explored in zooplankton, which occupies a pivotal position in aquatic food webs by linking primary producers (e.g., phytoplankton) to higher trophic levels, such as fish and invertebrate predators. Among freshwater zooplankton, microcrustaceans like Daphnia magna and Ceriodaphnia spp. are widely used as model organisms in standardized aquatic toxicity assays [33,34] (Table 2). Multiple studies show that Daphnia magna is highly sensitive to both DBP and DEHP, exhibiting acute toxicity responses and impaired reproduction at environmentally relevant concentrations [33,58]. Specifically, the LC50 values of DEHP for juvenile D. magna were 0.83 mg L−1 and 0.56 mg L−1 after 24 and 48 h, respectively, whereas for adults, the LC50 dropped to 0.48 mg L−1 (24 h) and 0.35 mg L−1 (48 h). Within the first 24 h of exposure, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, a marker of lipid peroxidation, increased significantly, suggesting the onset of oxidative stress. Concurrently, antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and glutathione S-transferase (GST) were upregulated as a compensatory response. However, prolonged exposure (≥48 h) led to a sharp decline in enzymatic defenses, indicating a collapse of the antioxidant system. DEHP exposure also modulated the transcription of key stress-related genes, including CAT (catalase) and GST, suggesting molecular-level interference with the oxidative stress response [33]. Similar outcomes have been observed in Ceriodaphnia cornuta, where DEHP exposure altered growth and reproductive performance. In chronic-exposure experiments conducted at environmentally relevant concentrations (50–500 µg L−1), DEHP did not significantly affect the survival of the freshwater cladocerans D. magna and Ceriodaphnia cornuta [34,58,59].

Nevertheless, DEHP, together with other phthalates, such as DBP and DEP, has been associated with a range of sublethal toxic effects.

In D. magna, comparative chronic exposures (14 days) to 1 and 10 µM DEHP, DBP, or DEP did not induce acute mortality or hatching delays but led to significant reductions in body length and enhanced lipid accumulation in all treatments [58]. Notably, DEHP at 1 µM unexpectedly increased reproductive output, whereas DEP and DBP had no effect on fecundity. In contrast, DEP at 10 µM and DBP at both concentrations significantly reduced life span [33].

In another experiment, the chronic effects of two common plastic additives, DEHP and BPA, were assessed on the tropical micro-crustacean C. cornuta, both individually and in combination, at environmentally relevant concentrations (50 and 500 μg L−1) [34]. Over a 10-day exposure, DEHP had no significant impact on survival, and BPA showed minimal toxicity, with survival rates above 80%. Similarly, the mixture of DEHP and BPA did not significantly affect survival, aligning with previous findings on D. magna [59]. However, C. cornuta exhibited marked sensitivity in terms of reproduction and growth. While DEHP slightly enhanced reproductive output (up to 115% of control), BPA strongly inhibited it (down to 21–22%), and their mixture induced a synergistic reproductive suppression (5% of control). In terms of growth, both DEHP and BPA individually increased body length, but their mixture had an antagonistic effect, resulting in no significant size difference compared to controls [34]. These results suggest energy trade-offs and potential competitive binding mechanisms affecting endocrine and growth regulation.

In another exposure toxicity test, the responses of D. magna were evaluated following exposure to DEHP alone and in combination with the heavy metals Pb and Cd at environmentally relevant concentrations (50 μg L−1 DEHP, 4.2 μg L−1 Pb, and 5.4 L−1 Cd) [60]. While DEHP alone did not affect survival, maturation, or reproduction, the binary mixtures with metals induced severe adverse effects. Co-exposures led to high mortality (70–100%), significant delays in maturation, and substantial reductions in reproductive output, with offspring production decreasing to as low as 3.7% of control levels [60]. These combined effects are likely due to increased metabolic and detoxification energy demands, highlighting the importance of considering mixture toxicity. Overall, the findings emphasize that combined exposures to DEHP and heavy metals pose a far greater risk to D. magna than single compounds alone [60].

Similarly, in a further chronic-exposure test, the effects of two widely used plasticizers, DEHP and tris(2-butoxyethyl) phosphate (TBOEP), were evaluated on C. cornuta, using both an artificial medium and natural Mekong River water at a concentration of 100 μg L−1 over 14 days [61]. Both compounds significantly reduced survival in C. cornuta, while in the artificial medium, they paradoxically stimulated reproduction without affecting growth. However, in the more complex matrix of river water, the plasticizers markedly decreased reproductive success. These findings reveal that the toxicity of DEHP and TBOEP is amplified in natural aquatic environments, likely due to interactions with other environmental factors. Also in this case, the results underscore the limitation of relying solely on standard test media, as they may underestimate risks posed by such pollutants under realistic exposure scenarios.

Regarding phthalate monoesters, the authors of [62] have investigated the impacts of MEHP, a primary metabolite of DEHP, on D. magna, focusing on lipid alterations and reproductive outcomes. Exposure to MEHP at concentrations up to 2 mg L−1 did not induce mortality but significantly increased lipid droplet accumulation (after 96 h) and reproductive output (after 21 days). Non-targeted metabolomics revealed 283 altered lipid metabolites, including glycerolipids, glycerophospholipids, and sphingolipids, following 48 h of exposure. At the molecular level, MEHP modulated the expression of ecdysone receptor (EcR) and vitellogenin 2 (Vtg2), with an initial upregulation observed at 6 and 24 h, followed by downregulation at 48 h in the 1 and 2 mg L−1 exposure groups. These findings suggest that MEHP-induced alterations in the EcR signaling pathway may underlie the observed lipid accumulation and enhanced reproductive capacity in D. magna, as observed also with DEHP [58,62].

Overall, Cladocerans show consistent vulnerability to PAEs across trophic and environmental contexts, confirming their role as sensitive bioindicators.

2.1.2. Echinoidea

The ecotoxicological consequences of PAEs on marine invertebrates remain largely unexplored, with only limited evidence available from sea urchin models. In Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, environmentally relevant PAE levels have been shown to decrease larval survival [63], whereas in Paracentrotus lividus, developmental abnormalities were reported only under comparatively elevated exposure conditions [64]. A recent study investigated the effects of a mixture of six PAEs commonly found in the aquatic environment on the development of the sea urchin Arbacia lixula at multiple functional levels: ecotoxicological, morphological, and biochemical [35] (Table 2). The authors found a strong dose-dependent response to PAEs, with PAE-exposed embryos showing delayed or malformed development, a stunting effect on skeleton growth, and the modulation of activity of stress response enzymes (alkaline phosphatase, esterase, and peroxidase). Strikingly, when embryos were co-exposed to PAEs and heatwave conditions, the authors found that thermal stress decreased embryo tolerance to PAEs, with an EC50 lower by 76%. Combined exposure also led to more developmental abnormalities and impaired skeletal growth. Biochemical assays indicated that temperature primarily modulated stress-response enzyme activities, suggesting that sea urchin embryos can experience markedly enhanced sensitivity under combined environmental stressors, emphasizing the need for ecological risk assessments that account for both PAE mixtures and climate-related drivers [35].

2.1.3. Insecta (Chironomidae)

Some studies have evaluated the toxic effects of PAEs in Chironomidae species, in particular, Chironomius riparius.

Park and Kwak [65] analyzed the expression of the serine-type endopeptidase (SP) gene from C. riparius after exposure to various concentrations of DEHP during its life-history stages, showing that gene expression decreased significantly across all DEHP dosages, and it may be used as a potential biomarker in response to DEHP. Planelló et al. [36] (Table 2) have assessed the alterations of some prominent genes linked to the endocrine system, cellular stress response, and ribosomal machinery in C. riparius to increased concentrations of DEHP e BBP, focusing on three gene families: stress-related genes (hsp70/hsc70), hormonal-related genes (EcR and usp), and housekeeping genes (rDNA). Their study revealed that exposure to DEHP or BBP stimulated the expression of the hsp70 gene in a dose-dependent manner, whereas the form hsc70 was not altered by these contaminants. Moreover, transcription of ribosomal RNA, which measure cell viability through levels of ITS2, was not influenced by DEHP but was significantly downregulated by BBP at the highest concentrations tested. Lastly, it has been demonstrated that BBP caused overexpression of the EcR gene, increasing from 0.1 mg L−1, whereas exposure to DEHP reduced the activity of this gene at the highest concentration [36].

Herrero et al. [37] (Table 2) investigated the toxicity of BBP in C. riparius aquatic larvae, analyzing changes in genes linked to stress response, the endocrine system, energy metabolism, and detoxication pathways, as well as in the enzyme activity of GST. The analysis showed that 24 h exposures to increased doses of BBP negatively influenced larval survival and caused a strong response of various heath-shock genes (hsp70, hsp40, and hsp27) and endocrine disruption through the upregulation of the ecdysone receptor gene (EcR), whereas treatments with low doses of BBP led to a repression of transcription and GST activity [37].

Dos Santos Morais et al. [38] (Table 2) analyzed the toxic effects of BBP on Chironomis sancticaroli, after exposure to increased concentrations of BBP (0.1–2000 µg L−1), evaluating genotoxic effects in the oxidative stress pathways and development. The study has demonstrated that BBP caused a reduction in cholinesterase (ChE) activity, in antioxidant pathways, in GST and in SOD activity at all tested concentrations. Moreover, it has been reported DNA damage after acute and subchronic exposure [38].

2.1.4. Gastropoda

At the molecular level, further insights were gained by evaluating the effects of DEP, BBP, and DEHP on the freshwater gastropod Physella acuta [41] (Table 2). After one week of exposure to concentrations of 0.1, 10, and 1000 µg L−1, gene expression analysis via real-time PCR revealed that BBP significantly modulated the transcription of nearly all the 30 target genes, which are involved in critical biological processes including DNA repair, detoxification, apoptosis, oxidative stress, immune response, energy metabolism, and lipid transport. In contrast, DEP and DEHP did not elicit notable changes in mRNA levels. These findings suggest that BBP exerts a broad molecular impact, possibly linked to its endocrine-disrupting properties on gastropods [41].

Biological effects of PAEs have also been assessed on other species of aquatic invertebrates.

Zhou et al. [66] evaluated the toxicological impacts of diallyl phthalate (DAP) as an endocrine disruptor of the abalone Haliotis diversicolor supertexta after three months of exposure and using proteomic profile of hepatopancreas. Their study demonstrated that abalone was sensitive to DAP, and this contaminant significantly influenced abalone’s physiological activities, such as detoxification/oxidative stress, hormonal modulation, cellular metabolism, and innate immunity, while after a 5 d pre-experiment, the LC50 value of DAP was 5000 μg L−1 [66].

2.1.5. Anellida

Lu et al. [67] examined the negative impacts of DBP on embryogenesis of sessile marine invertebrate Galeolaria caespitosa, showing abnormal embryos, cytokine disruption, and suppression of superoxide dismutase activity in spermatozoa, leading to a decrease in fertilization rates.

2.1.6. Bivalvia

Xu et al. [39] (Table 2) studied the toxicity of DEHP in Mytilus galloprovincialis, analyzing dose-dependent effects to several levels of exposure on antioxidant enzyme activity, gene expression, and metabolism. Mussels were exposed to five concentrations (4, 12, 36, 108, and 324 µg L−1), and a range of biomarkers, including antioxidant enzyme activities, gene expression (CAT, GST, and MgGLYZ), and metabolite profiles, were analyzed. At environmentally relevant concentrations (12 and 36 µg L−1), DEHP induced clear hormetic effects, evidenced by U-shaped or inverted U-shaped trends in gene expression and enzyme activities (SOD and CAT). Metabolomic analysis further highlighted a monophasic response in osmotic regulation (homarine) and a biphasic pattern in energy-metabolism markers (glucose, glycogen, and amino acids) [39].

2.1.7. Malacostraca

Yurdakok-Dikmen et al. [68] investigated the endocrine-disruption effects of DEHP in narrow-clawed crayfish Astacus leptodactylus, examining the bioaccumulation of this contaminant in hepatopancreas, muscle, gill, intestine, and gonads, and showing that this compound was less toxic compared to other environmental pollutants with endocrine-disrupting effects.

He et al. [69] investigated the effect of DBP on the detoxification, antioxidant, survival, and growth of the swimming crab juveniles Portunus trituberculatus, showing that DBP exposure caused responses of three cytochrome P450 members and antioxidant enzyme genes, transcription of gene and protein levels of GST, two heat-stress-protein and malondialdehyde accumulations, decrease in glutathione level, and inhibition of antioxidant enzyme activities. Further, no significant effect of DBP was observed in crab survival, size, and weight, but there was molting retardation.

2.1.8. Copepoda

The marine copepod Tigriopus japonicus was used to assess the interaction between DBP and polystyrene microplastic (mPS) [40] (Table 2). Acute toxicity tests revealed an LC50 for DBP of 1.23 mg L−1, while mPS alone showed no significant lethality. Interestingly, the presence of mPS reduced the bioavailability and toxicity of DBP, likely due to adsorption mechanisms. However, in chronic exposure tests, mPS negatively impacted reproductive parameters, reducing nauplii production and delaying hatching, while DBP alone had minimal effects at lower concentrations. An antagonistic interaction between DBP and mPS was observed in both acute and chronic tests, though the mechanisms differed: in chronic exposure, mPS aggregation in the presence of DBP may have altered bioavailability or uptake. These findings stress the importance of considering long-term exposure and mixture effects when evaluating the ecological risks of microplastics and associated contaminants [40].

2.2. Anphibians

Amphibians are increasingly recognized as highly valuable indicators for assessing the ecotoxicological effects of environmental stressors, especially endocrine disruptors (EDs) [70].

Their unique life cycle, particularly the obligatory aquatic phase during larval development, makes them exceptionally suitable for evaluating waterborne contaminants [70]. Unlike other anamniotes, amphibian embryos lack a protective eggshell, making them directly exposed to pollutants in surface water [70]. Their permeable skin further enhances the uptake and bioaccumulation of hazardous substances, rendering larval stages extremely sensitive to environmental toxins [70]. Despite the wealth of research on ED effects in fish, knowledge about their impact on amphibians remains limited, an alarming gap considering the suspected role of EDs in the global decline of amphibian populations. While factors like increased UV radiation and habitat degradation partly explain this decline, they cannot account for all cases, highlighting the need to investigate ED effects more thoroughly in amphibians [70,71]. Amphibians are classical model organisms in endocrinology and developmental biology, supported by a robust body of basic research, particularly on reproductive and thyroid systems. Their endocrine systems, organized similarly to those of other vertebrates, feature complex feedback mechanisms and multiple potential targets for ED action, ranging from hormone receptors to metabolic and secretion pathways. This structural and functional similarity makes amphibians not only ideal for studying endocrine disruption but also relevant for extrapolating findings to other vertebrate groups.

Given their sensitivity, ecological relevance, and well-understood physiology, amphibians are indispensable models for uncovering the mechanisms and consequences of endocrine disruption in the environment.

In this context, among EDs, the effects of phthalates on amphibians are still largely understudied [72].

In Western clawed-frog larvae, a 72 h exposure to DMP resulted in an LC50 of 11.9 mg L−1 [73], a value lower than that reported for aquatic invertebrates and fish. In Japanese wrinkled frog tadpoles, exposure to 27.8 mg L−1 of DBP was acutely lethal, causing 100% mortality within 5 min [74]. In African clawed frogs, the 96 h LC50 for DBP was 14.5 mg L−1 [43] (Table 2).

Phthalate diesters have demonstrated acute toxicity to tadpoles, with exposures to 9.1 mg L−1 of DMP and 4.1 mg L−1 of dicyclohexyl phthalate (DCHP) significantly increasing mortality in developing Western clawed-frog larvae compared to controls [73]. Surviving individuals exhibited a higher frequency of malformations, delayed development, or altered gene expression. However, the lowest observed effect concentrations (LOECs), 0.03 mg L−1 for DMP and 1.5 mg L−1 for DCHP, remain two to three orders of magnitude higher than the maximum concentrations currently detected in aquatic environments [73].

Multiple studies show that DBP induces concentration-dependent mortality and developmental impairment in X. laevis, even at low exposure levels. Refs. [42,43] evaluated the effects related to exposure to environmentally relevant concentrations of DBP on the embryogenesis, spermatogenesis, survivability, and development of the African frog Xaenopus laevis, using Frog Embryo Teratogenesis Assay—Xaenopus (FETAX). The study revealed that acute exposure to DBP at a low concentration (0.01 ppm) during 96 h of life influenced normal growth and development in X. laevis frogs, whereas exposure to a concentration of 5 ppm of DBP and higher led to mortality. Adverse effects of DBP produced noticeable malformations in the ability of developing embryos to swim as stage 46 tadpoles and caused severe decrease in secondary spermatogonial cell nests and several lesions based on denudation of germ cells, vacuolization of Sertoli cell cytoplasm, thickening of lamina propria of seminiferous tubules, and focal lymphocytic infiltration. For instance, DBP exposure causes severe malformations, particularly impairing locomotor performance, and it disrupts early embryonic cleavage and cellular organization.

Endocrine-disrupting effects of DBP and of its major metabolite MBP have also been investigate by [75] in X. laevis frogs due to their ability to interfere with thyroid hormone system. The authors analyzed changes in expression of selected thyroid hormone responses: thyroid hormone receptor-beta (TRβ), retinoid X receptor gamma (RXRγ), and alpha and beta subunits of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSHα and TSHβ). In particular, their study has demonstrated that exposure effects to DBP and MBP is concentration-dependent, inhibits growth, and significantly influences metamorphic development. In addition, embryos of X. laevis frogs were used in the study carried out by Gardner et al. [46] to assess toxicity and teratogenicity of ortho-phthalate esters DEP, DnPP, and DBP through the 96 h FETAX. Teratogenic risk did not change markedly with alkyl chain length, with data showing only DBP to be teratogenic. Overall, DBP emerges as the most potent teratogenic phthalate in this species, driving malformations and growth impairment in a dose-dependent manner. In addition, their study has demonstrated that increasing concentrations of phthalates induced malformations, negatively influenced teratogenic indices, and inhibited growth. Malformations have also been observed in developing X. laevis larvae exposed to DEP, DnPP, and DBP at lower concentrations [46] (Table 2). Similar results have been reported by Xu and Gye [44], Xu et al. [76], and Arancio et al. [77], who tested common phthalate ester plasticizers such as DBP, BBP, DOTP, di(2-propylheptyl)-phthalate (DPHP), DiNP, and DiDP. DBP significantly affected survival and growth of X. laevis, causing morphological abnormalities [44,76] (Table 2); meanwhile, DBP also caused disruption of cleavage divisions, and it showed cytokinesis and cellular dissociation [77].

The 96 h LC50 value of DBP for X. laevis embryos was determined to be 13.3 mg L−1 [44].

Zhang et al. [45] investigated the influence of DEHP on metamorphosis rate, thyroid hormone levels, thyroid histology, and gene expression in the Chinese brown frog Rana chensinensis. Their findings revealed that exposure to the highest DEHP concentration may increase body size in R. chensinensis larvae and lead to significant delays in metamorphosis. Histopathological alterations in the thyroid gland, including evident colloid depletion, were observed, confirming that thyroid histology serves as a sensitive indicator of endocrine disruption in amphibians. Furthermore, high-dose DEHP exposure resulted in a significantly increased proportion of females and upregulation of CYP19 (cytochrome P450 aromatase) gene expression in male tadpoles, suggesting estrogenic effects and disruption of sex steroid signaling. These results support the hypothesis that DEHP interferes with both thyroid hormone and sex steroid pathways during gonadal differentiation, highlighting a potential crosstalk between these endocrine axes [45] (Table 2).

Recently, Jiang et al. [78] examined histological characteristics of R. chensinensis tadpoles, highlighting that the skin was subjected to injury after exposure to cadmium (Cd) and DEHP, leading to an imbalance of skin microbial community homeostasis and interfering with the normal trial status of the host. This co-exposure paradigm may more accurately reflect the cumulative damage associated with environmental pollutant exposure. In a study conducted on the same species under comparable experimental conditions, it was observed that combined exposure resulted in a significant reduction in the abundance of butyrate-producing Firmicutes, impairment of lipid storage and transport mechanisms, and a diminished anti-inflammatory response [79]. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the presence of DEHP in the co-exposure group appeared to attenuate the cadmium (Cd)-induced weight loss, suggesting potential interactions that modulate the overall toxicological outcome [79].

Bissegger et al. [80] conducted a study examining the effects of PAE exposure on malformations and the mRNA expression of genes involved in reproduction and oxidative stress. Their findings demonstrate that PAEs act as teratogens in amphibian embryos. In particular, exposure to 0.1 μM DEHP, DBP, and DEP induced several malformations, including incomplete gut coiling, edema, and ocular defects, and was associated with increased expression of androgen-related genes (steroid 5α-reductase 1/2/3, steroid 5β-reductase) and the androgen receptor within the 0.1–10 μM concentration range, which is consistent with phthalate-induced modulation of these gene pathways [80].

On the other hand, Kamel et al. [81] investigated the effects of BBP and DBP on the hypothalamic–pituitary thyroid axis of X. laevis larvae, using Amphibian Metamorphosis Assay (AMA), through exposure to increased concentration of the compounds (3.6, 10.9, 33.0, and 100 µg L−1). Their study revealed that the selected chemicals caused a rise in the developmental-stage frequency distribution at a concentration of DBP equal to 143 µg L−1, whereas histopathology showed an abnormal development and mild thyroid follicular cell hypertrophy at all BBP concentrations. In addition, increased snout–vent length was also observed for BBP and DBP.

Taken together, amphibian studies confirm that PAEs (especially DBP) disrupt key developmental and endocrine pathways, supporting X. laevis as a sensitive model for aquatic endocrine disruption.

2.3. Reptiles

The effects of PAEs on aquatic reptiles remain poorly documented. The existing literature primarily focuses on bioaccumulation and biomonitoring, while detailed insights into post-exposure accumulation and toxicological mechanisms are typically derived from in vitro studies using cell cultures. Due to the scarcity of direct toxicity assessments in aquatic reptiles, potential effects are often inferred through comparisons with model organisms commonly employed in ecotoxicological testing. In vivo testing is generally discouraged for ethical reasons and is legally prohibited when it involves protected species. In contrast, in vitro approaches are increasingly adopted, as they can offer valuable insights into toxic effects at the organismal level. However, these methods have inherent limitations, including the inability to fully replicate the complex biological processes occurring within an intact organism.

Cocci et al. [47] (Table 2) investigated the effects of various endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including diisononyl phthalate (DiNP) and diisodecyl phthalate (DiDP), on primary erythrocyte cell cultures from the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) as an in vitro model for assessing toxicological responses. The study focused on evaluating erythrocyte viability, estrogen receptor α (ERα) expression, and heat-shock protein 60 (HSP60) expression. Among all tested compounds, DiDP caused the most pronounced reduction in cell viability at all time points when administered at 100 μM. In comparison, a significant decrease in erythrocyte viability following DiNP exposure was observed only after 48 h at the highest concentration (100 μM).

Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that ERα mRNA expression significantly increased at low concentrations of DiDP (0.0001–0.01 μM), with a marked reduction observed at 1 μM. A similar expression pattern was noted for DiNP, with upregulation starting at the intermediate concentration (0.01 μM). In terms of HSP60, exposure to 0.0001 μM DiDP led to a significant increase in its expression compared to the control group, whereas 0.01 μM DiNP caused a significant downregulation. Overall, these findings suggest that phthalates induce cytotoxicity in primary erythrocytes of Caretta caretta, potentially through mechanisms involving metabolic inhibition [47].

Unlike in vivo tests, ex vivo tissue cultures preserve, at least partially, the ultrastructure and biochemical functions of the tissue, offering a valuable platform for investigating tissue-specific cellular responses to various external stressors. In their effort to develop and apply ex vivo models as an alternative to traditional cell cultures, particularly for assessing the effects of phthalates, Bianchi et al. [48] (Table 2) combined biomarker analysis with proteomic profiling to obtain complementary information on the impact of phthalates in the sea turtle Caretta caretta. The study focused on MEHP, the main metabolite of DEHP, and demonstrated its genotoxic potential, along with its ability to promote reactive oxygen species production in multiple tissues, leading to oxidative stress. The importance of assessing molecular-level toxicity endpoints in environmental matrices was also emphasized by Lv et al. [82], who combined chemical analysis, species sensitivity distributions (SSD), and in silico docking to evaluate estrogen receptor-mediated risks in aquatic species from the Dongjiang River, China. Their results showed high concentrations of phthalates in water samples (Σ6PAEs ranging from 834 to 4368 ng L−1, with an average of 2215 ng L−1). The SSD analysis identified DBP, DnOP, and DEHP as compounds posing significant ecological threats, with turtles among the species most vulnerable to estrogenic toxicity.

With regard to accumulation mechanisms, although current studies show inconsistent patterns in the biomagnification of phthalates, several report evidence of biodilution. In particular, a study examining phthalate concentrations in the wild top predator Chinese water snake (Enhydris chinensis) and its main prey, the common carp (Cyprinus carpio), found no significant correlation between biomagnification factors and log KOW values. These findings suggest that biotransformation processes may play a predominant role in the elimination of phthalates from the snake’s body [49] (Table 2).

Although physiological mechanisms may help mitigate the toxic effects of phthalates, these compounds pose significant risks not only to exposed individuals but also to their offspring. Maternal transfer of pollutants has been shown to compromise embryonic viability, survival, and overall developmental health. Reptiles, which are currently facing global population declines and exhibit a high sensitivity to embryonic exposure, remain largely underrepresented in pollution risk assessments and conservation strategies [83]. Although maternal transfer of various contaminants has been reported in aquatic reptiles, the extent consequences of phthalate transfer through this pathway remain largely unexplored [49,83,84].

Liu et al. [49] reported that snake eggs contained a significantly higher proportion of DEHP (91%), a high-molecular-weight phthalate, compared to muscle tissue (66%). In contrast, DiBP and DnBP, which are lower-molecular-weight phthalates, were more abundant in carcass tissues (mean combined concentration of 17%) than in the eggs (3.8%). These differences in chemical distribution between eggs and muscle tissue are likely due to the variable maternal transfer potential of individual phthalates, which was found to be positively correlated with increasing log KOW values.

Among aquatic reptiles, sea turtles have proven to be an excellent model species for investigating environmental contamination, particularly with regard to the maternal transfer of phthalates [84]. Their long life span, broad migratory patterns, trophic position and behavior, and reproductive biology make them especially suited to assess how these lipophilic and endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) contaminants are transferred from females to offspring, potentially affecting embryonic development and survival [47].

The high prevalence of plastic debris in the gastrointestinal tract of sea turtles has led to their recognition as sentinel species and biomonitoring for marine litter [84]. One of the main adverse effects of plastic ingestion is the risk of chemical contamination caused by the prolonged retention of plastic particles in the gastrointestinal tract. This condition facilitates the release and subsequent absorption of plastic additives, such as PAEs, along with other toxic substances adsorbed into the plastic [85].

Despite their relevance, data on the biological effects of PAEs on sea turtles remain limited. According to Di Renzo et al. [86], microplastics and their associated additives negatively affect the health of C. caretta specimens, which showed gastrointestinal alterations and significant levels of phthalate contamination in tissues.

A previous study conducted by Savoca et al. [85] analyzed tissues from thirteen dead marine turtles found along the Sicilian coast, including one Dermochelys coriacea and twelve Caretta caretta specimens, using HPLC/MS to detect the presence of phthalates. Four phthalates, DBP, BBP, DEHP, and DnOP, were detected at relevant concentrations in the liver and gonads of C. caretta, while only DBP was found in the muscle of Dermochelys coriacea, at concentrations four times lower than those found in other tissues. In C. caretta, adipose tissue showed a high prevalence of the most lipophilic phthalates, particularly DEHP and DnOP, with total phthalate concentrations elevated across all tissue types [85].

Moreover, although to a lesser extent, notable levels of phthalates were also found in the eggs of this species [84]. Statistical analyses showed significant differences in the distribution of individual phthalates and their total concentration among the eggshell, yolk, and albumen. Based on these results, the authors of [84] proposed that maternal transfer is the most likely route of contamination, possibly originating from the release of phthalates during digestion.

This hypothesis is supported by several studies that found strong correlations between phthalate levels in maternal blood and in eggs, confirming maternal transfer as a key pathway [87,88,89]. Furthermore, experimental data suggest that when contaminants are applied externally to the eggshell, transfer to the albumen or yolk is minimal [90,91]. In addition, other potential sources of contamination, such as nest sediments, appear unlikely due to the low phthalate concentrations typically recorded in these matrices compared to those found in internal tissues of C. caretta, particularly in the liver [84,92]. The liver plays a central role in vitellogenin synthesis, a yolk precursor protein transported through the bloodstream to the ovaries, where it is deposited in developing oocytes. Since vitellogenesis occurs primarily during the foraging period, when turtles are more likely to ingest plastic debris, it is plausible that phthalates accumulated in maternal tissues are transferred to the eggs during this process [84].

However, further studies are needed to confirm this transfer hypothesis and, in general, on the fate of phthalates also in biotransformation processes leading to the formation of monoester metabolites. Recently, a study investigated the presence of 18 phthalate metabolites in 79 liver samples of C. caretta collected between 2016 and 2021. The results showed increasing concentration of these contaminants, likely associated with the extensive use of single-use plastics during the COVID-19 pandemic and with uncontrolled wastewater discharges. Moreover, a negative correlation was observed between phthalate metabolite concentrations and turtle body size, suggesting a possible dilution effect [93].

2.4. Mammals

Marine mammals are long-living organisms with large lipid deposits that are positioned at the top of the food chain, and, consequently, they are subjected to high accumulation of pollutants among aquatic organisms.

Among marine mammals, 60% of the species are threatened by pollution, thus making pollution the second most prevalent threat to marine biodiversity behind accidental mortality, such as by-catch [94].

Traditional in vivo toxicological studies are not feasible for large, free-ranging, and protected marine species due to ethical and logistical constraints. Moreover, laboratory in vivo experiments are conducted under highly controlled conditions that poorly reflect real-world exposure scenarios.

While toxic effects can be observed at the tissue level, such as receptor inhibition, hormone alterations, or tissue characteristics (e.g., testes weight), effects at the organ or whole-organism level are more relevant for population-level extrapolations. However, mechanistic understanding of pollutant impacts at these higher biological levels remains limited, with existing evidence largely based on empirical observations.

Ex vivo approaches, which involve culturing or analyzing tissues (e.g., blood, adipose, and kidney) from live or dead animals, offer a practical and ethical alternative. These methods are especially valuable in ecotoxicology, as they can be applied non-destructively to live, free-ranging animals (e.g., blood and skin) or invasively to stranded individuals (e.g., liver cells). For instance, blood or blubber samples can be used to simultaneously assess pollutant concentrations and their biological effects. Cell-based technologies further support rapid, ethical screening of chemical toxicity and environmental risk without the need for live-animal testing [94].

Unlike algae, fishes, or invertebrates, aquatic mammals have been the subject of more extensive research on bioaccumulation in natural environments than on the evaluation of associated biological effects. An exception is represented by a recent study that studied concentrations of PAEs in serum samples collected from aquarium-housed delphinids (Tursiops truncatus and Orcinus orca) located in California, Florida, and Texas (USA), exploring potential correlations between PAE presence and various biomarkers, including aldosterone, cortisol, corticosterone, hydrogen peroxide, and malondialdehyde, while accounting for sex, age, and reproductive status [50] (Table 2). All PAEs were detected in at least one individual. Total PAEs concentrations ranged from 6 to 2743 ng·mL−1 wet weight (w.w.) in bottlenose dolphins and from 5 to 88,675 ng·mL−1 w.w. in killer whales. Both species exhibited higher mean concentrations of DEP and DEHP. Results from the linear mixed model showed significant correlations between aldosterone levels, month, location, physiological status, and total PAE concentrations in killer whales, suggesting that aldosterone concentrations are influenced by the combined effects of these variables [50].

Considering the limitations in studying the effects of phthalates in aquatic mammals, the potential effects of these substances are often used as comparison models for terrestrial mammals such as mice and rats [95]. The adverse effects of phthalates are mainly linked in mammals to be activated through the perturbation of nuclear receptor signaling pathways. In detail, the key targets include PPARγ, estrogen receptors (ERα/ERβ), and thyroid hormone receptors (THRα/THRβ). Phthalate metabolites, such as mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (MEHP), are PPARγ agonists, triggering metabolic dysregulation. Concurrently, they exhibit weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activity via ERs, disrupting reproductive development and steroidogenesis. Moreover, they are antagonists of THR, impairing thyroid hormone signaling, and ultimately altering hormone levels and consequent deficits in neurodevelopment and metabolism [96].

Recent research shows that phthalates are present in both wild and captive marine mammals, accumulating mainly in adipose tissues. To our knowledge, there are not so many studies focusing on the molecular mechanisms of phthalates in acting through specific receptors, e.g., PPARs, in the specific context of marine mammals. However, most of the research demonstrates associations between exposure and effects, rather than explaining the underlying mechanisms. In an in vitro study from 2023, benzyl butyl phthalate (BBzP) was found to accumulate in juvenile grey seals [97], triggering the expression of adipose-specific genes, whereas the phosphorylation of the chinase Akt was unaffected. In a 2024 study on dolphins and killer whales, phthalates were found in serum samples and, importantly, also in newborns, suggesting a possible placenta- or lactation-mediated or maternal transfer [50]. In addition, in a more recent study, researchers reported that phthalate exposure in wild dolphins might be linked to dysfunctions in the metabolic, reproductive, or immune activity of dolphins, especially those having compromised health [98].

It has been reported that in mammalian cellular models, PAEs can induce metabolism disruption, mainly affecting lipid metabolism [99,100]. In particular, exposure to environmentally relevant doses of MEHP, a major metabolite derived from DEHP, could contribute to 3T3-L1 adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation, which was linked to the activation of the PPARγ signal pathway [101], creating adipocytes functionally distinct from those generated by rosiglitazone (a pharmacological compound that could enhance the development healthy white adipocytes), and suggesting that exposure to various levels of PAEs could produce dysfunctional adipocytes that are able to disrupt global energy homeostasis [102,103]. It has been demonstrated that, in animals, regulation of energy homeostasis is crucial for their survival, in particular, for marine mammals, which are characterized by large fat stores and are often subjected to fat deposition/mobilization for insulation in order to cope with rapidly changing living environments and energy supplies in periods of food deprivation [104,105]. Although the effects of other PAEs and PAE metabolites are still poorly investigated, a study investigated endocrine-disruptive potential and concentration of PAEs in marine mammals [52] (Table 2), particularly in the blubber/adipose tissue of blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus), fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus), bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus), and polar bears (Ursus maritimus) sampled in the Svalbard Archipelago Norwegian Arctic [52]. DEHP, ranging from <20 to 398 ng g−1 wet weight, was the only phthalate quantified among the 12 diesters of phthalic acids investigated [52]. Additionally, plasma samples from polar bears were analyzed for total concentrations of phthalate monoester metabolites, including their free and glucuronated forms; among these, mono-n-butyl phthalate and monoisobutyl phthalate were found in low concentrations (<1.2 ng mL−1) in some samples [52]. In vitro reporter gene assays were used to evaluate the transcriptional activity of PPARγ, glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and THRβ from fin whales in response to DEHP and DiNP. Due to the high similarity of the ligand-binding domains of THRB and PPARγ across whales, polar bears, and humans, the findings are also relevant to these species. DEHP exhibited both agonistic and antagonistic effects on whale THRB at concentrations much higher than those found in the sampled animals, while DiNP acted as a weak agonist. No significant effects were observed on whale PPARγ. However, both DEHP and DiNP reduced basal luciferase activity mediated by whale GR at several concentrations. In conclusion, although DEHP was detected in the blubber of Arctic marine mammals, current environmental levels do not appear to affect the nuclear receptor functions studied in the adipose tissues of blue whales, fin whales, bowhead whales, or polar bears from the Norwegian Arctic [52].

Another recent study quantified the concentrations of 11 phthalates in the blubber of 16 stranded and/or free-living marine mammals from the Norwegian coast, including the killer whale (Orcinus orca), sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus), long-finned pilot whale (Globicephala melas), white-beaked dolphin (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), harbor porpoise (Phocoena phocoena), and harbor seal (Phoca vitulina) [53] (Table 2). Five phthalates were detected across all samples: BBP in 50% of samples, DEHP in 33%, diisononyl phthalate (DiNP; 33%), DiBP (19%), and di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP; 13%).

Among the individuals sampled, the white-beaked dolphin showed the highest phthalate concentrations, while the killer whale, sperm whale, and long-finned pilot whale exhibited the lowest. Notably, no phthalates were detected in a neonate killer whale, suggesting inefficient maternal transfer and/or absence of phthalates in the mother. Given that the neonate died only a few hours before sampling, degradation of phthalates is unlikely [53].

These findings align with previous studies reporting a lack of maternal transfer of phthalates in the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) from the Brittany Gulf, France [106], and from Florida [107], based on blubber and urine analyses. This lack of phthalate transfer contrasts with earlier results on the same killer whale neonate that confirmed maternal transfer of other lipophilic pollutants [53].

Few studies have been carried out on mammals, and the major parts are focused on the negative impacts of some PAEs in cetaceans due to high vulnerability to contaminants related to their long life span, low reproduction rate, and high position in the trophic web [108]. Giovani et al. [51] (Table 2) investigated the cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of DEHP on a skin-derived cell line (TT) from the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), a coastal apex predator particularly vulnerable to lipophilic pollutants due to its high fat content in subcutaneous tissues.

Dolphin cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of DEHP (0.01–5 mM) to assess impacts on cell viability, cell death, and DNA integrity. After 24 h, both MTT and Trypan Blue assays showed no significant reduction in dolphin cell viability. Similarly, the comet assay detected no primary DNA damage. However, the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay revealed a clear increase in micronuclei formation and a reduction in cell proliferation, even at the lowest exposure levels. When compared with Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, DEHP produced more pronounced cytotoxic effects, including a marked increase in necrosis. In both cell types, the absence of direct DNA-strand breaks, alongside increased micronucleus formation, suggests that DEHP induces aneugenic effects disrupting chromosome segregation during cell division [51]. Overall, the potential chromosome loss detected could constitute a threat for species of marine mammals constantly exposed to plastic marine litter [51].

Bioaccumulation effects have been analyzed in the muscle of S. coeruleoalba, with higher values detected in males than in females, and without significant influence on reproductive conditions, suggesting that these animals can be considered potential bioindicators of these contaminants [108]. Similarly, phthalate metabolites were also detected in urine collected from T. truncatus by Hart et al. [109], whereas Giovani et al. [51] have highlighted the effect of DEHP in T. truncatus that causes cell death and micronucleus induction in vitro exposed skin cell line. In addition, lipid-disrupting effects of phthalate metabolites have been studied by Xie et al. [110] in Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) from the South China Sea, demonstrating that chronic exposure to PAEs might negatively influence lipid metabolism in dolphins, as shown by the correlation between hepatic monoethylhexyl phthalate, accounting for over half of the ∑12mPAE concentrations, and blubber fatty acids. Studies focused on bioaccumulation of PAEs and their metabolites have also been performed using the tissue of the harbor porpoise Phocoena phocoena, showing a high bioaccumulation of mEP, mIBP, mBP, and PAEs in liver samples of P. phocoena [111].

Given the bioaccumulative potential and toxic effects of phthalates and their metabolites, as well as the uncertainties surrounding their biomagnification capacity, further exposure risk assessments are necessary to elucidate the environmental fate of these ubiquitous contaminants, particularly for those phthalates whose toxicological risks have not yet been fully characterized.

In this context, environmental monitoring activities are also essential to identify major and emerging sources of exposure. For example, one study analyzed various phthalate metabolites (mPAEs) in different fish species that are potential prey for Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins [112]. The study found that MEHP and mono-n-butyl phthalate (MBP) were the predominant metabolites detected, and that a specific species, Harpadon nehereus, could account for over 20% of the total mPAEs accumulated in dolphins through dietary intake [112].

The diet also reflects trophic niches, as observed in a recent study that analyzed fatty acid profiles and phthalate (PAE) concentrations in the blubber of two oceanic cetacean species to explore ecological niche differences, exposure to plastic additives, and health implications [113]. This research provides the first baseline data on PAEs in free-ranging cetaceans from the Madeira Island region. Significant interspecies differences were observed in both FA composition and PAE levels, indicating distinct metabolic traits, feeding habits, and exposure routes. Bottlenose dolphins showed higher PAE concentrations, likely reflecting habitat-specific exposure and dietary patterns [113].

2.5. Utilizing the Current Evidence in Ecological Risk Assessment

Current toxicological evidence demonstrates that PAEs can induce adverse developmental, reproductive, and endocrine alterations across multiple aquatic taxa, supporting their classification as contaminants of emerging concern. The comparative sensitivity patterns identified in invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and marine mammals highlight the need to integrate cross-taxa data to more accurately identify vulnerable species and life stages in ecological risk assessments. Moreover, consistent findings of dose-dependent toxicity in PAE mixtures, together with interactions observed between PAEs and environmental variables such as temperature (see [35]), indicate that realistic exposure scenarios should account for mixture effects and climate-related stressors. The incorporation of biochemical and cellular endpoints also offers early-warning indicators that can complement traditional apical outcomes. Overall, the mechanistic and phenotypic insights synthesized in this review provide a valuable foundation for the refinement of prospective risk-assessment models under current and future environmental conditions.

3. Conclusions

Phthalates are an emerging class of contaminants increasingly detected in aquatic environments, where they exert significant ecotoxicological effects on a wide range of organisms, including both model and non-model species such as invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. An integrated analysis of the literature reveals that PAEs can interfere with essential biological processes, inducing adverse effects at multiple levels of biological organization, from gene expression to physiological and behavioral responses (Figure 1).

In aquatic invertebrates, PAE exposure leads to alterations in larval development, reproductive and immune dysfunctions, and significant bioaccumulation and histological changes, often associated with oxidative stress. In amphibians, PAEs mainly act as endocrine disruptors, impairing metamorphosis, gametogenesis, and thyroid function, with potential consequences for population survival in contaminated habitats. These effects are particularly severe during sensitive life stages, such as embryonic and larval development.

For aquatic reptiles, available data remain limited but point to potential risks related to bioaccumulation, neurotoxicity, and hormonal disruption. Studies on reptilian cell cultures suggest vulnerabilities similar to those observed in higher vertebrates. In aquatic mammals, toxicological evidence reveals endocrine, hepatic, and reproductive alterations observed both in experimental models and in individuals affected by environmental contamination, underscoring a potentially underestimated ecological risk for these apex species.

Overall, a clear interspecific variability emerges in toxicological responses to PAEs, attributable to physiological, metabolic, and phylogenetic differences. The integration of in vivo, in vitro, and ex vivo studies has provided a more comprehensive picture of the possible mechanisms of action, although significant knowledge gaps persist, particularly concerning non-model reptiles and mammals. A comparative evaluation of PAEs’ toxicity across taxa highlights important differences in sensitivity and ecological implications. Among aquatic invertebrates, cladocerans such as Daphnia magna and Ceriodaphnia spp. consistently emerge as the most sensitive bioindicators, showing acute lethality and pronounced sublethal effects even at environmentally relevant concentrations. Their pivotal role in pelagic food webs amplifies the ecological consequences of such impairments, potentially altering energy transfer to higher trophic levels. Amphibians, particularly during embryonic and larval stages, display an equally high vulnerability, largely due to their permeable skin and the critical processes of metamorphosis, which are strongly dependent on endocrine regulation. Disruption of thyroid and reproductive axes by PAEs can therefore have severe repercussions for population viability and may contribute to the global decline of amphibians. In contrast, aquatic reptiles and mammals tend to accumulate PAEs and their metabolites due to their lipid-rich tissues and long life spans, but evidence of population-level impacts remains scarce. In these taxa, most data are derived from biomonitoring or in vitro/ex vivo models, highlighting substantial knowledge gaps. Evidence of maternal transfer in reptiles and potential intergenerational effects in mammals underscores the need to evaluate transgenerational toxicity under realistic exposure scenarios. Taken together, these findings suggest that while invertebrates and amphibians provide early-warning signals of acute and developmental toxicity, reptiles and mammals highlight the long-term risks of bioaccumulation and potential transgenerational transfer. Integrating these patterns into ecological risk assessments is essential to better predict cascading effects within aquatic ecosystems and to guide conservation and management policies.

Importantly, recent studies emphasize the relevance of co-exposure scenarios, where organisms are simultaneously exposed to multiple PAEs or to mixtures of PAEs and other environmental contaminants. These combined exposures may lead to synergistic, additive, or antagonistic effects, complicating the prediction of toxic outcomes. Moreover, environmental factors such as temperature, pH, salinity, and dissolved oxygen, particularly under climate-change scenarios, can modulate the bioavailability and toxicity of PAEs, further influencing organismal responses. For instance, elevated temperatures may exacerbate metabolic stress or enhance the uptake of lipophilic contaminants, potentially amplifying toxic effects. Understanding these interactions is crucial for assessing realistic environmental risks.

This review underscores the need to develop more representative environmental risk assessment strategies, incorporating currently neglected sentinel species and multidisciplinary approaches. In particular, the adoption of standardized methodologies for assessing chronic, sublethal, and multigenerational effects of PAEs, under both single and combined exposure conditions and across variable environmental scenarios, is crucial for the accurate protection of aquatic ecosystems and biodiversity.

Ecological Risk Assessment and Policy Recommendations

Given the pervasive occurrence of PAEs and their documented effects across multiple taxa, advancing towards a more comprehensive ecological risk-assessment framework is essential. Future research should prioritize the creation of an integrated cross-taxa sensitivity database that consolidates mechanistic and phenotypic endpoints from invertebrates, amphibians, reptiles, and marine mammals. Such harmonization would support the identification of vulnerable species and refine regulatory thresholds. In parallel, dynamic modeling approaches are needed to assess real-world exposure scenarios that include mixture toxicity (e.g., PAEs combined with metals or microplastics) and climate-change stressors (e.g., co-exposure PAEs + warming, and hypoxia), as these interactive factors can markedly alter and/or amplify organismal sensibility. Importantly, reptiles and marine mammals should be incorporated into priority monitoring programs, as current data remain insufficient to inform conservation measures despite their elevated ecological relevance and trophic transfer risk. Collectively, these actions would enhance both predictive power and regulatory applicability, ensuring that ecotoxicological evidence effectively supports management decisions and ecosystem protection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S., C.M. and S.O.; methodology, D.S. and C.M.; validation, S.O., A.M., V.A., D.A. and G.A.; formal analysis, D.S. and C.M.; investigation, D.S., C.M. and S.O.; resources, D.S. and S.O.; data curation, D.S. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S., C.M., S.O., A.M., V.A., D.A. and G.A.; visualization, D.S. and C.M.; supervision, S.O., A.M., V.A., D.A. and G.A.; project administration, D.S. and S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree No. 3175 of 18 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU (Award number: project code CN_00000033) and Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, (CUP B73C22000790001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated in this study. All data discussed are available in the published literature and referenced accordingly.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Biodiversity Future Center (NBFC) Project funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of December 18, 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU; Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP B73C22000790001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”. Figure 1 was created using https://BioRender.com Martino [114]), https://BioRender.com/froezxm (accessed on 28 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Al-Saleh, I.; Elkhatib, R. Screening of Phthalate Esters in 47 Branded Perfumes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Zuccarini, M.; Cichelli, A.; Khan, H.; Reale, M. Critical Review on the Presence of Phthalates in Food and Evidence of Their Biological Impact. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, C.L.T.; Hoang, N.B.; Nguyen, A.V.; Le, V.; Tran, N.M.T.; Pham, K.T.; Phung, H.D.; Chu, N.C.; Hoang, A.Q.; Minh, T.B.; et al. Distribution of Phthalic Acid Esters (PAEs) in Personal Care Products and Untreated Municipal Wastewater Samples: Implications for Source Apportionment and Ecological Risk Assessment. Water Air Soil. Pollut. 2025, 236, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Agarwal, A.K.; Gupta, T.; Maliyekkal, S.M. (Eds.) New Trends in Emerging Environmental Contaminants; Energy, Environment, and Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2022; ISBN 9789811683664. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, C.; Ni, J.; Chang, F.; Liu, S.; Xu, N.; Sun, W.; Xie, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. Bio-Source of Di-n-Butyl Phthalate Production by Filamentous Fungi. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.N. Bioactive Natural Derivatives of Phthalate Ester. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 913–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, A.; Vaglica, A.; Maccotta, A.; Savoca, D. The Origin of Phthalates in Algae: Biosynthesis and Environmental Bioaccumulation. Environments 2024, 11, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, A.A.; Enikeev, A.G.; Babenko, T.A.; Shafikova, T.N.; Gorshkov, A.G. Phthalates—A Strange Delusion of Ecologists. Theor. Appl. Ecol. 2021, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoca, D.; Barreca, S.; Lo Coco, R.; Punginelli, D.; Orecchio, S.; Maccotta, A. Environmental Aspect Concerning Phthalates Contamination: Analytical Approaches and Assessment of Biomonitoring in the Aquatic Environment. Environments 2023, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Tao, Y.; Yang, Y. Hazards of Phthalates (PAEs) Exposure: A Review of Aquatic Animal Toxicology Studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 145418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucaccioni, L.; Trevisani, V.; Passini, E.; Righi, B.; Plessi, C.; Predieri, B.; Iughetti, L. Perinatal Exposure to Phthalates: From Endocrine to Neurodevelopment Effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, G.R.; Dettogni, R.S.; Bagchi, I.C.; Flaws, J.A.; Graceli, J.B. Placental Outcomes of Phthalate Exposure. Reprod. Toxicol. 2021, 103, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punhagui-Umbelino, A.P.F.; Frigoli, G.F.; de Aquino, A.M.; Jorge, B.C.; Alonso-Costa, L.G.; Erthal-Michelato, R.P.; Arena, A.C.; Scarano, W.R.; Fernandes, G.S.A. Phthalate Exposure During Pregnancy and Lactation Transgenerationally Impairs the Epididymis in the Offspring of Rats. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2025, 39, e70379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sree, C.G.; Buddolla, V.; Lakshmi, B.A.; Kim, Y.-J. Phthalate Toxicity Mechanisms: An Update. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 263, 109498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, W.; Wang, Y.; Cui, K.; Chen, W.; Liu, J.; Jin, H.; Zhou, Z. Reproductive Toxicity and Multi/Transgenerational Effects of Emerging Pollutants on C. elegans. Toxics 2024, 12, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Lin, F.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Lai, L. Computation of Octanol−Water Partition Coefficients by Guiding an Additive Model with Knowledge. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007, 47, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Manzetti, S.; Zhang, H.; Klamt, A. Prediction of Partition Coefficients of Environmental Toxins Using Computational Chemistry Methods. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 13772–13781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergé, A.; Cladière, M.; Gasperi, J.; Coursimault, A.; Tassin, B.; Moilleron, R. Meta-Analysis of Environmental Contamination by Phthalates. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 8057–8076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Net, S.; Sempéré, R.; Delmont, A.; Paluselli, A.; Ouddane, B. Occurrence, Fate, Behavior and Ecotoxicological State of Phthalates in Different Environmental Matrices. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 4019–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.M.; Nguyen, H.M.N.; Nguyen, V.K.; Nguyen, A.V.; Vu, N.D.; Yen, N.T.H.; Hoang, A.Q.; Minh, T.B.; Kannan, K.; Tran, T.M. Profiles of Phthalic Acid Esters (PAEs) in Bottled Water, Tap Water, Lake Water, and Wastewater Samples Collected from Hanoi, Vietnam. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 788, 147831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Liang, H. An Overview of Phthalate Acid Ester Pollution in China over the Last Decade: Environmental Occurrence and Human Exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 1400–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehmeh, B.; Haydous, F.; Ali, H.; Hdaifi, A.; Abdlwahab, B.; Orm, M.B.; Abrahamian, Z.; Akoury, E. Emerging Contaminants in the Mediterranean Sea Endangering Lebanon’s Palm Islands Natural Reserve. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.I.; Yu, X.; Padilla, I.Y.; Macchiavelli, R.E.; Ghasemizadeh, R.; Kaeli, D.; Cordero, J.F.; Meeker, J.D.; Alshawabkeh, A.N. The Influence of Hydrogeological and Anthropogenic Variables on Phthalate Contamination in Eogenetic Karst Groundwater Systems. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]