Abstract

This work illustrates a machine learning methodology to forecast pipe failure frequencies in drinking water systems to enhance asset management and operational planning. Three supervised regression models—Random Forest Regressor (RFR), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP)—were developed and evaluated using historical failure data from Malatya, Türkiye. The primary predictive variables identified were pipe diameter, pipe type, pipe age, and seasonal average ambient air temperature. The MLP demonstrated superior performance compared to the other models, attaining the lowest RMSE (1.48) and the highest R2 (0.993) with respect to the training data, effectively capturing the nonlinear characteristics and failure patterns. The MLP was validated using two datasets from 24 District Metered Areas (DMAs) in Sakarya and Kayseri, Türkiye. The model’s anticipated failure frequencies exhibited strong concordance with the observed failure frequencies, even in regions of elevated failure density, indicating the model’s proficiency in identifying high-risk locations and facilitating the prioritization of maintenance activities. The work demonstrates the potential of machine learning in water infrastructure management. It emphasizes the importance of employing a hybrid method with Geographic Information Systems (GISs) in future research to enhance forecast accuracy and spatial analysis.

1. Introduction

Water is an indispensable natural resource vital for life on Earth. Current water resources are experiencing heightened stress due to rising global populations, rapid urbanization, extensive industrialization, and the impacts of climate change. In this context, sufficient supply, distribution, and sustainable management of water have emerged as critical components of contemporary urban governance. The provision and distribution of drinking water are not solely technical matters; they are strategically important for public health, environmental sustainability, and economic development [1,2]. Urban drinking water systems are intricate networks that transport water to users and manage the extraction and discharge of treated water, facilitating its movement from the source through distribution channels. A drinking water system generally comprises source structures, pumping stations, treatment facilities, primary and secondary transmission lines, distribution systems, and consumer water connections [3,4,5]. Drinking water systems may deteriorate over time due to many factors, resulting in technical and economic disturbances. The technical failures resulting from these reasons may be physical, including fractures, bursts, leaking joints on and between pipes, valve malfunctions, corrosion, ground movements, and fatigue. Notable non-physical systemic variable failures encompass unanticipated urbanization, inadequately executed maintenance and repairs, and aged infrastructure components [6]. Failures in drinking water systems result in water losses and diminish system efficiency, escalate energy usage, and adversely affect water quality. For instance, drinking water systems operating under low-pressure circumstances are susceptible to contamination from the surrounding environment, posing significant public health issues [5,7]. Moreover, malfunctions in drinking water systems lead to unanticipated water disruptions, diminishing customer comfort and potentially decreasing public satisfaction with municipal services. Thus, forecasting breakdowns in drinking water systems to inform preventive maintenance decisions is essential for technical sustainability and service quality.

Forecasting failures entails modeling the system’s behavior through historical data and other analytical methods to anticipate future failure scenarios proactively. Various methodologies are accessible, ranging from statistical analysis to artificial intelligence techniques. Techniques such as data mining, machine learning, artificial neural networks, fuzzy logic, regression analysis, and time series modeling have been increasingly explored in drinking water systems. However, it should be noted that machine learning methods, in particular, are still under trial and their effectiveness is debated, with ongoing discussions regarding their learning performance, data requirements, and the challenges posed by their black-box nature [8,9,10,11]. These methods offer a substantial advantage by employing extensive datasets produced by system sensors to examine data trends related to failures and to facilitate decision-making processes. Three primary forms of pipe failure models are heuristic, physical, and statistical. Regarding physical approaches, recent studies in the literature emphasize the effectiveness of executing transient tests for verifying pipeline integrity and detecting faults [12,13]. Many authors in the literature have methodically examined and classified these models at several degrees of abstraction [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. The current literature studies, however, either cover only deterministic and probabilistic approaches or have a limited period and concentrate on only the past ten years of work. Moreover, there is a lack of focus on assessing models applied to infrastructure components, including large-diameter transmission mains [21].

From first-order deterministic equations, to more intricate models handled as probabilities and models guided by data, pipe failure models have evolved. With the limited application of these approaches in our sector, machine learning models have been popular since they allow users to uncover links in complicated data structures and offer improved prediction capacities. Reviewing the methods applied in this field deserves more attention, considering the increasing frequency of machine learning models. The relevance of machine learning techniques is especially evident in improving the predictive capacity for decision-making on the use of infrastructure [22].

Moreover, regulatory incentives that encourage innovation are expected to foster greater interest in the application of machine learning and data analytics to support the management of critical data repositories [23]. In this context, the use of advanced analytical techniques to interpret large datasets from drinking water systems is expected not only to enhance the operational efficiency of existing systems but also to improve the accuracy of failure predictions [24,25].

A review of studies on failure prediction reveals that Motiee and Ghasemnejad [26] analyzed 583 km of drinking water pipelines over a three-year period and developed four different regression models. Similarly, Giraldo-González and Rodríguez [27] investigated a 652 km network over two years and developed separate models for cast iron (CI), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and asbestos cement (AC). Other studies have focused on smaller areas, identifying factors influencing failures and attempting to construct localized failure models. However, these studies lack practical demonstration of how the reported models can be translated into tools for real-world application or how they can be utilized by water utilities. Furthermore, only a limited number of studies employ a comprehensive set of pipe-specific, environmental, and operational covariates, highlighting not a shortcoming of the studies themselves, but rather the limitations in the availability of relevant data [22,28,29,30]. While these studies have contributed significantly to understanding pipe failures in water distribution networks, their methodological strengths and limitations should also be highlighted. For example, Moslehi et al. [31] provide a rigorous economic framework for determining leakage targets using detailed field pressure and flow measurements; however, their work does not involve predictive modelling and therefore cannot capture nonlinear relationships among multiple failure-related variables. In contrast, Aydogdu and Firat [32] demonstrate that combining fuzzy clustering with LS-SVM improves estimation accuracy within homogeneous sub-regions, representing an important advancement for localized modelling. Nevertheless, their reliance on relatively small datasets and region-specific clusters limits the generalizability of their results across larger or more heterogeneous networks. More broadly, statistical and regression-based studies often assume linearity and have restricted feature sets, while many machine learning applications rely on limited validation or lack integration with real-time operational data such as pressure, temperature, or soil characteristics. These strengths and weaknesses collectively indicate that there is still a need for comprehensive, data-rich, and generalizable modelling approaches capable of capturing complex, nonlinear interactions in large-scale water distribution systems.

In conclusion, the ability to predict failures in drinking water systems is crucial for the development of more resilient and sustainable urban infrastructure. The aim of this study is to examine methods for predicting failures in drinking water systems, evaluate their effectiveness, and provide examples from existing implementations. In addition, by offering detailed information on the types of data used, analytical techniques applied, and performance metrics reported, the study seeks to contribute both theoretically and practically to this growing field of research. In this study, failures in the selected case study area were analyzed based on pipe diameter, pipe material, pipe age, and average air temperature, and a failure prediction model was developed. The model was tested in independent regions, and the results were presented.

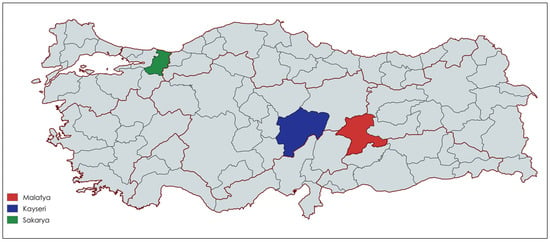

2. Study Area and Data

The study area for failure analysis and prediction was Malatya province in Türkiye. Malatya encompasses an area of 12,313 km2 with a population of approximately 750,091. The drinking water distribution system in the research region, spanning 1,888,000 m, serves approximately 350,000 people and features pipe diameters ranging from 63 mm to 300 mm (Figure 1). The pipe materials included cast iron (CI), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), and asbestos cement (AC).

Figure 1.

Study Area.

Compared to analogous studies in the literature, substantial data was collected for 4560 failure episodes documented by the Malatya Water and Sewerage Administration (MASKI), constituting a significant dataset.

The data collected in the research field was utilized for Geographic Information Systems (GISs), Subscriber Management Systems, Fault Management Systems, and Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA). Each documented failure was georeferenced inside a GIS framework, and the corresponding pipe diameter, pipe material, and failure date were assigned. This study examined the influences of pipe diameter, material, age, and ambient air temperature on pipe failure. In this study, pressure values were found to fall within a narrow range, averaging between 5.2 and 6.0 bar. All 4560 fault records examined occurred within this range, indicating that the pressure in the water distribution system is homogeneous. While the literature recognizes the impact of pressure reduction on reducing fault frequency, statistical analysis was conducted to assess the impact of limited changes within a narrow pressure range on fault frequency. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results indicated no significant difference between pressure levels (F-statistic: 0.887, p-value: 0.489), a finding attributed to the narrow pressure range characterized by a mean of 55.49 m (~5.5 bar), a standard deviation of 1.72 m, and a coefficient of variation of 0.031. This confirms the methodological appropriateness of excluding the pressure variable. However, the effect of pressure on fault frequency may be more pronounced in systems with wider pressure ranges, an issue that should be investigated in detail in future studies.

Water quality can influence pipe deterioration through processes such as corrosion or internal scaling; however, in the distribution networks examined in this study, no reclaimed or recycled water is used, and no significant spatial variation in water quality exists across the systems. Therefore, water-quality-related variables could not be meaningfully incorporated into the models. Nonetheless, this factor is important, and future studies conducted in networks with measurable water-quality gradients should consider integrating parameters such as pH, conductivity, and corrosivity indices to enhance predictive performance.

Moreover, soil-related variables were not included in this study because high-resolution and fully georeferenced soil data were not available for the entire network, and using inconsistent layers would have introduced additional uncertainty into the model. However, as more detailed GIS-based soil maps (e.g., soil type, corrosivity, moisture content) become available, future studies will incorporate these variables to further enhance predictive performance.

While the model encompasses the essential variables—pipe diameter, material, age, and ambient air temperature—it omits additional factors that may influence failure and should be addressed in future studies to enhance the overall quality of our model.

3. Methodology

In this study, supervised machine learning methods were employed to predict failures in pipe systems. The input variables included pipe diameter (Diameter), pipe type (Type), pipe age (Age), and ambient air temperature (Temperature), while the target variable was the number of failures, represented by the variable NoF (Number of Failures). Three different regression algorithms were used in the development of the predictive models: Random Forest Regressor, XGBoost Regressor, and Artificial Neural Network (Multi-Layer Perceptron Regressor—MLPRegressor). This section details the data preprocessing steps, the modeling process, and the performance metrics.

Prior to analysis, the dataset was first split into training (%60), validation (%20), and testing (%20) sets. These same statistics were used to normalize the validation and testing sets, ensuring that no information from the validation or testing sets influenced the model during training [30].

Categorical variables such as pipe diameter and pipe type in the dataset were converted to numerical data using one-hot encoding and included in the model. This method represents each categorical value (e.g., each pipe type) as a separate binary column. Thus, these variables were processed appropriately for machine learning models and included in the model. Numerical variables such as age and temperature were used directly and no normalization or scaling was applied.

The dataset was reviewed for data quality and consistency. It is noteworthy that the target variable represents the annual failure rate. In this context, periods with a high number of failures are considered critical real-world events rather than erroneous data points. Removing these values would prevent the model from learning to predict high-risk scenarios, which is a primary objective of this work. Therefore, no outlier removal was performed on the failure rate data to preserve the integrity of the underlying physical phenomena.

3.1. Machine Learning Models

3.1.1. Random Forest Regressor

A Random Forest Regressor (RFR) is created utilizing a supervised learning methodology for failure prediction in pipeline systems. Established by Breiman [33], Random Forest Regression (RFR) is a bagging technique that uses many decision trees created and averaged to get final predictions. RFR utilizes a randomly selected subset of the training data to train each decision tree, thereby reducing the variance of the model, improving its generalizability, and minimizing overfitting to the training data. The models were evaluated using standard regression metrics, such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and R-squared (R2). At the same time, the hyperparameters—number of trees and maximum tree depth—were adjusted by cross-validation. The model’s hyperparameters were optimized through a 5-fold cross-validation process on the training set. The number of trees (n_estimators) was set to 100, and the maximum depth of each tree (max_depth) was set to 10. These values provided a balance between model complexity and computational efficiency while preventing overfitting.

3.1.2. XGBoost Regressor

The XGBoost Regressor functioned as the secondary failure prediction instrument. XGBoost, or Extreme Gradient Boosting, is an efficient ensemble learning technique based on gradient-boosted decision trees, Chen and Guestrin [34], which creates new trees at each iteration to address leftover errors from the preceding procedure. This method is particularly efficient for high-dimensional, sparse datasets, providing well-calibrated predictions with exceptional accuracy and speed. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using RandomizedSearchCV with 5-fold cross-validation. The key parameters optimized were the learning rate (set to 0.1), the maximum tree depth (max_depth set to 6), and the number of estimators (n_estimators set to 150). This configuration was found to deliver robust performance without excessive computational cost. We evaluated model performance using the same criteria MAE, MSE, and R2 employed by the RFR model.

3.1.3. Multi-Layer Perceptron Regressor (MLP)

The Multi-Layer Perceptron Regressor (MLPRegressor), a deep learning model, was utilized in the final phase of the research to predict potential pipe failures. Regarded as a feed-forward artificial neural network, the MLP has an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and a concluding output layer. To effectively model the complex and non-linear characteristics of failure data, the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function was selected for the hidden layers. ReLU was chosen specifically because it mitigates the vanishing gradient problem often encountered in deep networks, allowing the model to learn intricate patterns more efficiently than sigmoid or tanh functions. Furthermore, the Adam optimization algorithm was employed during training due to its adaptive learning rate capabilities, which ensure robust and rapid convergence even with sparse or noisy data. The structure of the MLP model is defined as follows: 2 hidden layers with 64 neurons per layer. The output layer contains a single neuron, and no activation function is used (linear output). To ensure the stability and generalizability of the model, a 5-fold cross-validation protocol was applied. While early stopping was used to mitigate the risk of overfitting, the training parameters were determined as follows: learning rate 0.001, batch size 32, and maximum epoch number 1000. The assessment of model performance was completed with the same criteria as in previous successful methodologies [35].

3.2. Statistical Performance

To assess the performance of the algorithms used in this study, the following performance metrics were employed: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE), Normalized Mean Bias Error (NMBE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Index of Agreement (IOA), and Coefficient of Determination (R2). These metrics are defined by the following equations:

where n is the total number of data points; yactual is the observed value; ypredict is the predicted value; actual is the mean of the observed values; predict is the mean of the predicted values; and var(yactual) is the variance of the actual values [36]. This study used a number of metrics, including RMSE, NMSE, NMBE, MAE, MAPE, IOA, and R2, to evaluate model performance. RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) measures the model’s error magnitude by taking the square root of the mean squared difference between the actual and predicted values. NMSE (Normalized Mean Squared Error) normalizes the model’s error level according to the variance of the actual data, with a low value indicating good model performance. NMBE (Normalized Mean Bias Error) measures whether the model’s predictions are systematically biased. A positive value indicates overestimation, while a negative value indicates underestimation. MAE (Mean Absolute Error) directly measures the error magnitude by averaging the absolute difference between the actual and predicted values. MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) displays the error rate as a percentage, with a low value indicating the model’s sensitivity. IOA (Index of Agreement) measures how well the model’s predictions match the actual data, with a value close to 1 indicating that the model is making accurate predictions. Finally, R2 (Coefficient of Determination) indicates how much of the total variance the model explains in the data, with a value close to 1 indicating that the model can explain the data with high accuracy. These metrics measure the model’s accuracy, error magnitude, and prediction accuracy from different perspectives, allowing us to comprehensively evaluate overall performance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Factors Influencing Failures

To better understand the nature of the failures, all incidents were classified using the concept of failure frequency, defined as the number of failures per 100 km per year [37]. This metric allows for meaningful comparison of failures across pipes of different diameters, ages, and materials.

As a first step, the failures were analyzed in relation to pipe diameter, and the results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relationship Between Pipe Diameter and Failure Frequency.

An analysis of failures by pipe diameter reveals that smaller-diameter pipes in the network experience a higher frequency of failures compared to larger-diameter pipes. In particular, pipes with diameters of 63 mm, 75 mm, and 90 mm exhibit approximately 4 to 5 times more failures than those with larger diameters. This finding is consistent with previous studies in the literature, which indicate that pipes with diameters smaller than 150 mm tend to have higher failure frequencies [38,39]. However, the relationship between pipe diameter and failure frequency is influenced by various factors, including pipe material, pipe age, installation depth, soil characteristics, and environmental conditions. Therefore, it is essential to consider these additional parameters alongside pipe diameter in pipe failure prediction models.

Pipe material is another critical factor that affects the frequency of failures in drinking water systems. When planning long-term infrastructure strategies, water utilities must consider not only operational feasibility, cost, and practicality but also the susceptibility of different pipe types to failure. The failure frequencies calculated for the four different pipe materials found in the study area are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Relationship Between Pipe Material and Failure Frequency.

An analysis of failures by pipe material reveals that the highest number of failures occurred in cast iron (CI) pipes. These pipes, primarily due to their age and the lack of cathodic protection, have been the most failure-prone material as a result of corrosion. They are followed by asbestos cement (AC) pipes, which are particularly susceptible to failures in older systems due to aging and brittleness. The data also indicate that HDPE and PVC pipes tend to experience fewer failures. Both materials are resistant to ground movements, easy to install, and relatively cost-effective. As a result, these two types of pipes are predominantly used in Türkiye. Similar findings are reported in previous studies in the literature, supporting the results obtained in this study [27,40,41,42].

Several studies have indicated that failure frequency generally increases with pipe age, independent of pipe material and environmental conditions. The relationship between pipe age and failure frequency in the study area is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Relationship Between Pipe Age and Failure Frequency.

An examination of the study area shows that pipes up to 10 years old have a failure frequency below 13 failures per 100 km per year, which is generally considered an acceptable threshold [37,43]. However, due to material aging, failure frequency can reach as high as 192 failures per 100 km per year. This finding provides important insights for asset management. It highlights the necessity for water utilities to develop pipe replacement programs that take these values into account during the operational phase [44,45].

Temperature variations are also among the key factors contributing to failures in water distribution networks. Studies have shown that sudden temperature fluctuations significantly increase the likelihood of failures. Not only sudden changes but also prolonged exposure to extreme high or low temperatures can elevate failure frequencies [46,47]. For instance, cold weather conditions tend to increase failure frequency in cast iron pipes, whereas high temperatures are found to substantially raise failure frequencies in PVC and HDPE pipes. Table 4 presents data from the study area based on temperature ranges and corresponding failure frequencies.

Table 4.

Relationship Between Air Temperature and Failure Frequency.

In the study area, a significant increase in failure frequencies was observed with rising temperatures. This trend can primarily be attributed to the fact that the majority of the network—approximately 79%—is composed of HDPE and PVC pipes, as supported by findings in the literature. Consequently, elevated temperatures are seen to contribute to higher failure frequencies within the system.

Analyzing the factors that lead to failures is of critical importance for water utilities. Especially in the context of long-term planning, insights gained from the characteristics of the existing network can be used to design effective rehabilitation strategies. Additionally, these data can inform the selection of appropriate pipe materials for new installations. The results obtained in this study not only confirm widely accepted views in the literature but also provide quantifiable insights that can be applied in practice.

4.2. Failure Prediction Model

Three distinct models—RFR, XGB, and MLP—were selected to simulate failures in DWSs. MATLAB (Version R2022a) executed the selected techniques, and the results were documented. To assess model accuracy, the dataset was randomly divided into three segments, 60% for training, 20% for validation, and 20% for testing, before analysis. Each approach underwent a fair and consistent train/test split, ensuring an accurate assessment of anticipated accuracy. The models were used to predict the failure rate, specifically the number of failures per 100 km, which was the model output. Performance metrics for the models (RFR, XGB, and MLP) were calculated on the test set, and the results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Model Performance Indicators.

Standard global conventional performance metrics, including RMSE, NMSE, NMBE, MAE, MAPE, IOA, and R2, led the assessment of the models.

Among the models employing the three distinct techniques, the MLP model performed superiorly across nearly all metrics. The RMSE was 1.48283, indicating minimal discrepancies between projected and actual values, demonstrating the model’s accuracy in producing reliable predictions. The model demonstrated its capability to forecast future accuracy, evidenced by exceptionally low NMSE (0.00553) and MAE (1.22132) values. The MAPE value, calculated at 2.927%, provides compelling evidence that the model generated reliable predictions regardless of fault size.

The MLP model exhibited a minor positive bias in its predictions, with the NMBE measured at 0.00542. The RFR model exhibited a slight tendency to underestimate, as indicated by a negative NMBE of −0.00159. Although it did not maintain the load generated by the MLP model, the XGB exhibited more equitable NMBE calculations than the RFR model.

The MLP model achieved an IOA of 0.99787 and a R2 of 0.99309, indicating it accounted for over 99% of the variability in the observed data. Despite its superior performance (IOA = 0.99676 and R2 = 0.98917), the XGB model was inferior to the MLP in terms of error metrics. In terms of RMSE and MAE, the RFR model exhibited the worse performance overall.

These findings underscore the MLP model’s efficacy in predicting issues within drinking water systems, notably due to its ability to capture complex and nonlinear relationships. The capacity of artificial neural networks to comprehend intricate relationships among input variables significantly influenced this outcome. Nonetheless, MLP models typically exhibit constrained interpretability and elevated computational expenses. Based on the results, detailed outcomes related to the best-performing model MLP are presented in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4.

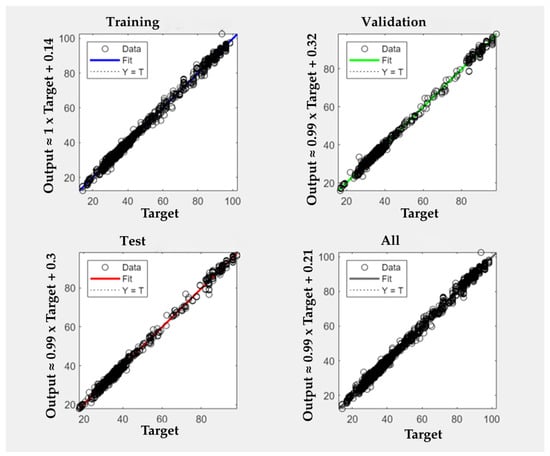

Figure 2.

Data Correlations for MLP.

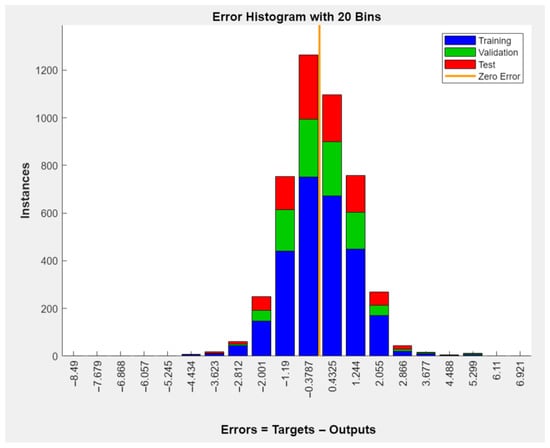

Figure 3.

Error Histogram for MLP.

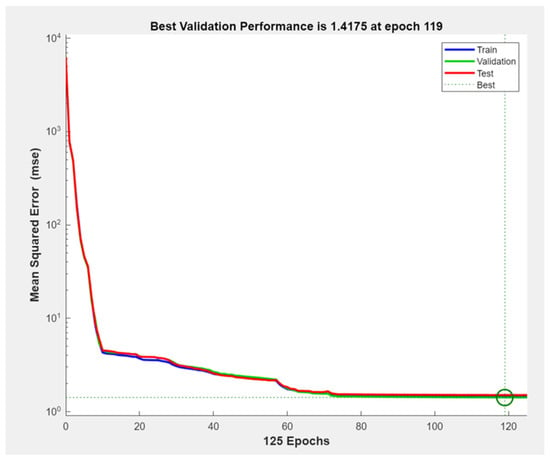

Figure 4.

Mean Squared Error Graph for MLP.

For the MLP model, the regression diagrams presented in Figure 2 were prepared to evaluate the performance of the developed prediction model across the training, validation, testing, and overall datasets. In each subplot, the horizontal axis represents the actual (target) values, while the vertical axis shows the predicted (output) values generated by the model. The circular markers indicate individual observations, solid, colored lines represent the model’s fitted regression lines, and the dashed lines denote the ideal prediction line, i.e., the Y = T (output = target) relationship.

An examination of the regression line in the training phase reveals that the model learned from the training data with nearly zero error. The proximity of the prediction values to the ideal line suggests that overfitting is not immediately apparent. During validation, the regression equation was obtained as Output = 0.99 × Target + 0.32, indicating that the model is capable of generalizing with high accuracy on unseen validation data. The slope value shows that predictions are very close to the target values, with no meaningful systematic bias.

Similarly, in the testing phase, the regression line was found to be Output = 0.99 × Target + 0.30, confirming that the model successfully transferred its learned patterns to previously unseen data. The predicted and observed values were closely aligned, with minimal deviations.

For the overall dataset, the regression line was calculated as Output = 0.99 × Target + 0.21, which suggests that the model consistently generated accurate and reliable predictions across the entire dataset without introducing significant systematic error. The slope being very close to 1 and the low intercept value indicate a balanced and stable performance throughout the prediction range.

Overall, the strong linear correlation observed at every stage—training, validation, and testing—demonstrates the model’s success in both learning and generalization. Additionally, the clustering of data points around the ideal linear line in the scatter plots further supports the conclusion that the model operates with low variance and minimal bias.

An error histogram was also generated for the model (Figure 3). This histogram, divided into 20 bins, was created to analyze the model’s prediction performance. The horizontal axis represents the error, defined as Error = Target − Output, while the vertical axis shows the number of samples (frequency) falling within each error range. Different datasets are color-coded: training data is shown in blue, validation data in green, and test data in red. Additionally, the zero-error line is represented in orange.

The shape of the histogram closely resembles a bell curve (normal distribution), indicating that the model generally performs with low errors. The highest concentration of data points lies within a narrow range near zero error (approximately between −0.43 and +0.43), with a noticeable density of training samples in this region. This suggests that the model was able to produce predictions close to the target values during training.

The comparable centering of the error distributions for the test (red) and validation (green) datasets indicates the model’s exceptional generalization ability. Low-variance and symmetric error distributions for non-training data indicate that the model does not exhibit overfitting.

Minimal occurrences near the extreme ends of the histogram—specifically, between −6 and −8 or between +5 and +7—suggest that the model infrequently produces substantial prediction errors. These uncommon abnormalities are likely caused by erratic data, exceptional conditions, or random deviations.

The model’s error distribution has a balanced structure throughout the training and testing/validation datasets, with the majority of prediction errors concentrated at zero. This indicates that, devoid of systematic bias, the model can produce reliable, consistent, and broadly applicable predictions.

An examination of the error graph from the training process (Figure 4) illustrates how the Mean Squared Error (MSE) values for different datasets (training, validation, and test) change over the number of epochs during model training. The blue line corresponds to the training data, the green line to the validation data, and the red line to the test data. The epoch at which the best validation performance was achieved (epoch 119) is highlighted with a green circular marker. The graph is presented on a logarithmic scale, allowing clearer observation of the rapid decline and stabilization in error values.

Looking at the overall trend of the curves, the model is seen to rapidly reduce the MSE starting from the initial epochs. This indicates that the model began learning the data effectively early on, and parameter updates contributed significantly to performance improvement. After approximately the 60th epoch, the rate of error reduction slowed across all curves, and around the 100th epoch, the error values began to stabilize. This suggests that the model had reached an optimal level of learning, where further training yielded no substantial improvements.

The best validation performance was achieved at the 119th epoch, where the validation error reached approximately 1.4175. This value reflects a high level of predictive accuracy on the validation set and indicates strong generalization capability. Furthermore, the alignment of the training and test error curves with the validation error supports the conclusion that the model did not suffer from overfitting and was able to apply learned patterns successfully across different datasets.

The parallel and closely aligned progression of the training, validation, and test curves demonstrates that the model exhibited balanced performance across all data partitions and that the learning process advanced in a stable manner. This also suggests that the hyperparameters used during training (e.g., learning rate, network architecture, number of epochs) were appropriately selected.

Overall, Figure 4 confirms that the model was trained effectively, experienced neither overfitting nor underfitting, and successfully identified the point of minimum validation error.

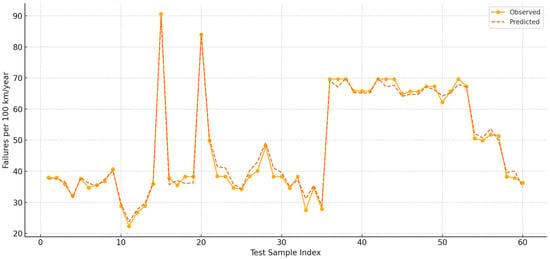

For the established model, predictions on a randomly selected subset of 60 test samples were compared to their actual values and are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of Observed and Predicted Failure Frequencies on the Test Data.

An examination of Figure 5 visually demonstrates the prediction accuracy of the developed model on the test dataset. The horizontal axis represents test samples, numbered from 1 to 60, while the vertical axis indicates the annual failure frequency per 100 km of pipeline. A comparison between the observed values and the values predicted by the model offers valuable insight into the overall predictive performance of the model.

A general review of the graph structure shows that the predicted values closely follow the observed ones, indicating that the model successfully learned the underlying patterns and accurately captured the dynamics within the data. The model’s ability to track sharp increases and decreases (e.g., between test samples 12–18 and 35–38) further demonstrates its sensitivity to variable trends.

Some local deviations are also observed—particularly at peak points such as test samples 14 and 36, where the predicted values slightly differ from the observed ones. However, these discrepancies appear to be random rather than systematic, suggesting that while the model may introduce minor errors when handling high-variance data, it still manages to capture the overall trend with considerable success.

In segments where the data is relatively flat (e.g., test samples 37–50), the model’s predictions almost perfectly match the observed values, indicating a strong ability to learn and replicate stable patterns. Additionally, the downward trend observed in the final portion of the test dataset (samples 50–60) is accurately followed by the model.

In conclusion, while all three models demonstrated acceptable levels of performance, the MLP model provided the highest accuracy and reliability in predicting failures in drinking water systems. This reflects the model’s robustness and capacity to generate trustworthy predictions not only during training but also when applied to real-world data.

When the predictive performance of this study is interpreted within the broader context of the literature, it is important to consider methodological and scale-related differences among studies. In [31], the reported RMSE values (>2.3) arise from an economic leakage assessment framework rather than a predictive machine-learning model; thus, similarities exist only in thematic scope, not in modeling objectives. In [32], LS-SVM outperformed FFNN and GRNN models after fuzzy clustering was applied to create homogeneous sub-regions. The very low RMSE value reported in that study (0.0086) reflects the fact that the target variable was normalized and modeled separately within narrowly defined clusters, yielding a much smaller numerical range. By contrast, the target variable in this study—the annual number of failures per 100 km—is naturally larger in magnitude (typically ranging between 0 and 20 or more). Therefore, an RMSE of 1.48 corresponds to an average prediction error of only about 1.5 failures per 100 km per year, which is realistic and meaningful for practical applications. This scale dependency underscores why a direct numerical comparison of RMSE values across studies may be misleading. For this reason, we also emphasize scale-independent metrics: the proposed MLP model achieved an R2 of 0.98583 on independent DMA test regions (The maximum R2 value seen in the study [32], including subsets, was 0.736.), demonstrating strong generalization capability across diverse network conditions without the need for prior segmentation. These distinctions clarify the observed performance differences and highlight the robustness and practical applicability of the proposed approach.

In future studies, even greater success may be achieved by developing hybrid or ensemble models that combine the strengths of neural networks and tree-based algorithms.

4.3. Real-World Data Testing

Although the developed model demonstrated successful performance on internal test datasets, its applicability to different water networks is equally important. To evaluate the model’s performance under varying conditions, data from the provinces of Sakarya and Kayseri in Türkiye—distinct from the original study area of Malatya—were selected for further testing (Figure 1).

In this context, data were collected from a total of 24 measurable sub-regions (District Metered Areas—DMAs), including 11 from Sakarya and 13 from Kayseri. These are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of DMA (District Metered Area) Data.

The creation of DMAs (District Metered Areas) plays a critical role in drinking water management [48,49,50]. These areas are physically separated from other parts of the network and are continuously monitored using flow meters installed at their inlets. Moreover, DMAs can be integrated with subscriber management systems, fault management systems, and Geographic Information Systems (GISs).

In the 24 selected DMAs, systematic failure records have been maintained. These records include additional data such as the age, diameter, material type, and location of the pipes where failures occurred. To ensure a robust testing process, the selected regions were chosen to represent a variety of pipe materials, diameters, and ages (see Table 6).

The actual failure data from these areas were used as input to the MLP model, and the resulting predictions are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

MLP Model Predictions vs. Actual Failures in DMA Regions.

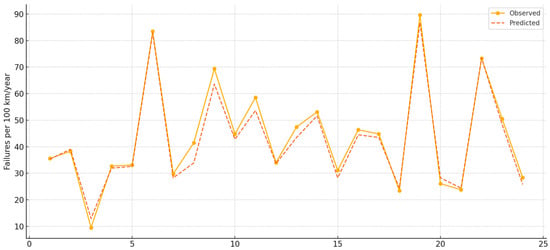

As a result of the analyses, the comparison between actual failure data and model predictions is presented in Table 7 and Figure 6. The table includes the total pipe lengths for various DMA regions, the annual number of failures, the observed annual failure frequency per 100 km (Observed Failure/100 km/year), and the corresponding values predicted by the model (Predicted Failure/100 km/year). Such a comparison is highly valuable for assessing both the model’s ability to generalize across different regions and its sensitivity to local variations.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Observed and Predicted Failure Frequencies on Real Field Data.

A general evaluation of the dataset reveals a high level of agreement between the observed failure frequencies and the values predicted by the model. In nearly all DMAs, the predicted values either match the observed rates exactly or differ by only a small margin. This indicates that the model has not only captured the overall distribution accurately but has also successfully learned local variations at the DMA level.

In a few DMAs, there are noticeable discrepancies between the observed and predicted values. For example:

- In SasDMA8, the observed failure frequency was 41.49, while the model predicted 33.90. This deviation (approximately 7.6 points) may stem from the model’s tendency to suppress extreme values (i.e., peak-prone regions) or from unexplained external factors specific to this area.

- In SasDMA3, the model predicted 12.92, compared to the observed value of 9.49, slightly overestimating the failure frequency. Such minor deviations may result from the fact that, in DMAs with low failure frequencies, even small numerical changes can appear disproportionately large in percentage terms.

- In high-failure-rate areas such as KasDMA8 (Observed: 89.63, Predicted: 86.72) and KasDMA11 (Observed: 73.29, Predicted: 73.50), the model produced highly accurate predictions. This demonstrates the model’s capability to correctly identify high-risk zones.

The statistical performance of the developed model is presented in Table 8. Upon examining the results, it is evident that the model achieved successful prediction performance.

Table 8.

Performance Metrics.

The model demonstrated significant predictive accuracy across DMAs with low and high failure frequencies. This indicates that the developed prediction method can substantially assist in proactively identifying existing infrastructure threats and can be reliably utilized in field-based decision-support systems.

To strictly evaluate the position of the proposed MLP model within the current literature, a comparison with prominent studies published in the last five years is presented in Table 9. This comparison includes various machine learning approaches ranging from Logistic Regression to recent Deep Learning and Ensemble applications. The metrics demonstrate that the proposed MLP model achieves state-of-the-art performance, outperforming or matching the best results reported in similar recent studies.

Table 9.

Comparison Of the Proposed Model with Recent Studies in the Literature.

Comprehending the localized behavior of the model and permitting region-specific prioritization relies on DMA-level analyses. The model’s performance is demonstrated to be consistent and steady.

5. Conclusions

This study used machine learning techniques to determine pipe failure frequencies in drinking water systems. The study evaluated the efficacy of various strategies, including Random Forest Regressor (RFR), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), to ascertain the most effective method for predicting annual failure variance per 100 km of pipeline.

In comparison to the other models, the MLP model achieved the lowest RMSE (1.48), MAE (1.22), and the highest coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.99309), thereby establishing it as the most accurate and reliable. Based on the visual analyses, it can be concluded that error histograms and regression graphs effectively demonstrated the model’s substantial predictive capability despite nominal variation from actual data. The MLP model effectively generalized the three datasets (training, validation, and test), successfully identifying nonlinear and complex relationships within the data.

The DMA level experiments indicate that the model can produce precise local estimations, validating its potential for risk-based maintenance planning and asset management of pipelines. The method’s ability to identify locations with elevated failure frequencies underscores its significance for repair prioritization. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that the model’s performance depends significantly on the quality and completeness of the input data. Incorporating additional external variables—such as soil conditions, variations in pipe material, and fluctuations in hydraulic pressure—could further enhance prediction accuracy.

The model’s predictions allow us to prioritize maintenance by determining the annual failure frequency of pipelines. These predictions indicate that pipelines with high failure frequencies require a high maintenance priority. Maintenance plans can be supported by parameters such as historical data and the maintenance budget, and a maintenance threshold can be determined. This threshold can be set at the 13 failures/100 km identified in previous studies [37,43], or it can be set individually for each water utility. This threshold can be determined using parameters such as historical maintenance data, pipeline type and age, environmental factors, and the maintenance budget.

These findings confirm that machine learning, particularly MLP-based models, can play a pivotal role in the proactive management of aging water infrastructure. Future research may also focus on a deeper integration of failure prediction models with GIS-based asset management systems and real-time supervisory infrastructures. The combined use of GIS and SCADA can enable the automatic capture of failure events at the moment they occur, allowing the system to instantly associate the event location with spatially referenced pipeline attributes such as pipe age, diameter, material, installation year, and burial conditions, as well as dynamic operational variables including average pressure, temperature, and soil characteristics on the day of the failure. Such an integrated framework would allow the raw operational data to be transformed into analysis-ready datasets without manual intervention, significantly improving the timeliness and reliability of predictive modeling. Moreover, when the full water distribution network is represented within GIS, enriched with real-time and historical hydraulic and environmental layers, it becomes possible to compute spatially explicit indicators such as the expected number of failures per 100 km for each sub-region, detect emerging high-risk zones, and design targeted rehabilitation or maintenance strategies for critical areas. As more operational, environmental, and structural systems become interoperable within the GIS environment, the management of water distribution assets can become increasingly proactive, data-driven, and spatially optimized.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data, models, and code used during the study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with local water utilities. However, anonymized or aggregated versions of the datasets and model configurations may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to institutional approval.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the cooperation of the General Directorate of Water and Sewerage Administration of Malatya (MASKI) for providing data and information. The author declares that AI-assisted tools (specifically ChatGPT-5, DeepL, and Grammarly) were used only for translation from Turkish to English and for language editing during the preparation of this manuscript. These tools did not contribute to the generation of scientific content, analysis, interpretation, or conclusions. All scholarly ideas, data, and findings presented in this article are entirely the author’s own work. The author assumes full responsibility for the accuracy, integrity, and ethical compliance of the manuscript, in accordance with MDPI publication policies. This study was conducted without any financial support from funding agencies, institutions, or organizations in the public, private, or non-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Asbestos Cement |

| ANOVA | One-Way Analysis of Variance |

| CI | Cast Iron |

| DMAs | District Metered Areas |

| GISs | Geographic Information Systems |

| HDPE | High-Density Polyethylene |

| IOA | Index Of Agreement |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MASKI | Malatya Water and Sewerage Administration |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| NMBE | Normalized Mean Bias Error |

| NMSE | Normalized Mean Squared Error |

| NoF | Number Of Failures |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| RFR | Random Forest Regressor |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| SCADA | Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition |

| XGB | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Scholten, L.; Scheidegger, A.; Reichert, P.; Maurer, M. Combining Expert Knowledge and Local Data for Improved Service Life Modeling of Water Supply Networks. Environ. Model. Softw. 2013, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, S.; Özdemir, Ö.; Fırat, M. Application of IWA Standard Water Balance in Strategic Water Loss Analysis: Benefits and Problems. Environ. Res. Technol. 2021, 4, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D. Standard Definitions for Water Losses: A Compendium of Terms and Acronyms and Their Associated Definition in Common Use in the Field of Water Loss Management; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, M.; Stewart, R.A. Implementation of Pressure and Leakage Management Strategies on the Gold Coast, Australia: Case Study. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2007, 133, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AWWA. Water Audits and Loss Control Programs-M36, 4th ed.; American Water Works Association: Denver, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, M.; Trow, S. Losses in Water Distribution Networks: A Practitioners’ Guide to Assessment, Monitoring and Control; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun, M.; Kammoun, A.; Abid, M. Leak Detection Methods in Water Distribution Networks: A Comparative Survey on Artificial Intelligence Applications. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2022, 13, 04022024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, I.; Jalili Ghazizadeh, M.; Yousefi-Khoshqalb, E. An Economic Valuation Model for Alternative Pressure Management Schemes in Water Distribution Networks. Util. Policy 2020, 67, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailhot, A.; Pelletier, G.; Noël, J.; Villeneuve, J. Modeling the Evolution of the Structural State of Water Pipe Networks with Brief Recorded Pipe Break Histories: Methodology and Application. Water Resour. Res. 2000, 36, 3053–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Velasco, A.; Cortés, P.; Muñuzuri, J.; Onieva, L. Prediction of Pipe Failures in Water Supply Networks Using Logistic Regression and Support Vector Classification. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 196, 106754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Peng, H.; Xu, Z.-D.; Qin, G.; Azimi, M.; Matthews, J.C.; Cao, L. Theory and Machine Learning Modeling for Burst Pressure Estimation of Pipeline with Multipoint Corrosion. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2023, 14, 04023022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniconi, S.; Brunone, B.; Tirello, L.; Rubin, A.; Cifrodelli, M.; Capponi, C. Transient Tests for Checking the Trieste Subsea Pipeline: Towards the Field Tests. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniconi, S.; Brunone, B.; Tirello, L.; Rubin, A.; Cifrodelli, M.; Capponi, C. Transient Tests for Checking the Trieste Subsea Pipeline: Diving into Fault Detection. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.-Q.; Fang, S.-Q.; Lin, L.-B. Mechanical Analyses of Underground Pipelines Subjected to Ground Subsidence Considering Soil-Arching Effect. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2023, 14, 04022076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, A.; Leitão, J.P.; Scholten, L. Statistical Failure Models for Water Distribution Pipes—A Review from a Unified Perspective. Water Res. 2015, 83, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, M.; Filion, Y. Forecasting Breaks in Cast Iron Water Mains in the City of Kingston with an Artificial Neural Network Model. Can. J. Civil. Eng. 2014, 41, 918–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, S.; Deligianni, A. A Neurofuzzy Decision Framework for the Management of Water Distribution Networks. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, Y.; Nafi, A.; Rajani, B. Planning Renewal of Water Mains While Considering Deterioration, Economies of Scale and Adjacent Infrastructure. Water Supply 2010, 10, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Ateş, A.; Firat, M.; Özdemir, Ö.; Cinal, H. Determination of Economic Loss Levels in Water Distribution Systems with Different Network Conditions by a District Stochastic Optimization Algorithm. Water Supply 2023, 23, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogárdi, I.; Fülöp, R. A Spatial Probabilistic Model of Pipeline Failures. Period. Polytech. Civil. Eng. 2011, 55, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.; Filion, Y.; Moore, I. State-of-the-Art Review of Water Pipe Failure Prediction Models and Applicability to Large-Diameter Mains. Urban Water J. 2017, 14, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.A.; Hallett, S.H.; Jude, S.R.; Tran, T.H. An Evolution of Statistical Pipe Failure Models for Drinking Water Networks: A Targeted Review. Water Supply 2022, 22, 3784–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce Romero, J.; Hallett, S.; Jude, S. Leveraging Big Data Tools and Technologies: Addressing the Challenges of the Water Quality Sector. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, B.; Ni, P.; Wang, Y. An Interpretable Machine Learning Model for Failure Pressure Prediction of Blended Hydrogen Natural Gas Pipelines Containing a Crack-in-Dent Defect. Energy 2025, 320, 135401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo, R.; Zayed, T.; Bakhtawar, B.; Adey, B.T. Explainable Deep Learning Models for Predicting Water Pipe Failures. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 379, 124738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motiee, H.; Ghasemnejad, S. Prediction of Pipe Failure Rate in Tehran Water Distribution Networks by Applying Regression Models. Water Supply 2019, 19, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo-González, M.M.; Rodríguez, J.P. Comparison of Statistical and Machine Learning Models for Pipe Failure Modeling in Water Distribution Networks. Water 2020, 12, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zayed, T.; Meguid, M.A.; Sushama, L. Predicting Failure Pressure of Corroded Gas Pipelines: A Data-Driven Approach Using Machine Learning. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 1424–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warad, A.A.M.; Wassif, K.; Darwish, N.R. An Ensemble Learning Model for Forecasting Water-Pipe Leakage. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verheugd, J.; de Oliveira da Costa, P.R.; Afshar, R.R.; Zhang, Y.; Boersma, S. Predicting Water Pipe Failures with a Recurrent Neural Hawkes Process Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Toronto, ON, Canada, 11–14 October 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 2628–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moslehi, I.; Jalili-Ghazizadeh, M.; Yousefi-Khoshqalb, E. Developing a Framework for Leakage Target Setting in Water Distribution Networks from an Economic Perspective. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2021, 17, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydogdu, M.; Firat, M. Estimation of Failure Rate in Water Distribution Network Using Fuzzy Clustering and LS-SVM Methods. Water Resour. Manag. 2015, 29, 1575–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, F. Multilayer Perceptrons for Classification and Regression. Neurocomputing 1991, 2, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirzad, A.; Tabesh, M.; Farmani, R. A Comparison between Performance of Support Vector Regression and Artificial Neural Network in Prediction of Pipe Burst Rate in Water Distribution Networks. KSCE J. Civil. Eng. 2014, 18, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, A.O.; Brown, T.G.; Takizawa, M.; Weimer, D. A Review of Performance Indicators for Real Losses from Water Supply Systems. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.—AQUA 1999, 48, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesalie, R.A.; Aklog, D.; Kifelew, M.S. Failure Assessment for Drinking Water Distribution System in the Case of Bahir Dar Institute of Technology, Ethiopia. Appl. Water Sci. 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Morales, U.; Corona Vásquez, B.; Prieto González, R.; Martínez Austria, P. Influence of the AMO and Its Modulation of the ENSO Effects on Summer Precipitation in Mexican Coastal Regions. Water Pract. Technol. 2023, 18, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadirek, I.E.; Kaya-Basar, E.; Akdeniz, T. A Study on Pipe Failure Analysis in Water Distribution Systems Using Logistic Regression. Water Supply 2024, 24, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasim, M.; Djukic, M.B. Corrosion Induced Failure of the Ductile Iron Pipes at Micro- and Nano-Levels. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 121, 105169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwinandha, D.; Zhang, B.; Fujii, M. Prediction of Reaction Mechanism for OH Radical-Mediated Phenol Oxidation Using Quantum Chemical Calculation. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, J.; Lambert, A.O. Pressure management extends infrastructure life and reduces unnecessary energy costs. In Proceedings of the IWA International Conference ‘Water Loss 2007’, Bucharest, Romania, 23–26 September 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, X. Machine Learning Based Water Pipe Failure Prediction: The Effects of Engineering, Geology, Climate and Socio-Economic Factors. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 219, 108185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvisi, S.; Franchini, M. Comparative Analysis of Two Probabilistic Pipe Breakage Models Applied to a Real Water Distribution System. Civil. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2010, 27, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamijala, S.; Guikema, S.D.; Brumbelow, K. Statistical Models for the Analysis of Water Distribution System Pipe Break Data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2009, 94, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajani, B.; Kleiner, Y.; Sink, J.-E. Exploration of the Relationship between Water Main Breaks and Temperature Covariates. Urban. Water J. 2012, 9, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yao, H.; Chu, S.; Yu, T.; Shao, Y. Optimized DMA Partition to Reduce Background Leakage Rate in Water Distribution Networks. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 2021, 147, 04021071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Ateş, A.; Özdemir, Ö. Determination of Economic Leakage Level with Optimization Algorithm in Water Distribution Systems. Water Econ. Policy 2021, 7, 2150014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, S.; Firat, M.; Ateş, A.; Özdemir, Ö. Analysis of Economic Leakage Level and Infrastructure Leakage Index Indicator by Applying Active Leakage Control. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 2021, 12, 04021046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).