Abstract

Objective: The aim was to evaluate the effects of two high-resistance training (RT) protocols combined with curcumin supplementation on antioxidant capacity, systemic inflammation, bone and muscle health, and body composition. Methods: Eighty-one apparently healthy older adults [(68.2 ± 4.6 years (57% women); BMI 26.4 ± 4.8 kg/m2; minimally active according to IPAQ] were randomly allocated to accentuated eccentric (Aecc), maximal strength (Max), or a non-training control (C). Additionally, participants received either a bio-optimized curcumin formulation (Cur) or a placebo (Pla), resulting in six study groups: Aecc-Cur, Aecc-Pla, Max-Cur, Max-Pla, C-Cur, and C-Pla. Participants underwent pre- and post-intervention assessments of oxidative stress, inflammation, and bone health parameters, whole-body composition, and muscle function. Aecc and Max performed six familiarization sessions and a 16-week intervention. Participants in the curcumin groups received 500 mg/day of a bio-optimized curcumin formulation (CursolTM; 2 × 250 mg capsules per day, corresponding to 10.50 mg/day of curcumin) throughout the intervention. Data were analyzed using three-way repeated-measures ANOVA/ANCOVA with time (pre–post) as the within-subject factor and training group and supplementation as between-subject factors, with Least Significant Difference post hoc comparisons and effect sizes (Hedges’ g, ηp2) reported, and the significance level set at p < 0.05. Results: Aecc was the most effective in improving antioxidant capacity (glutathione; F = 25.57, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.262) and bone biomarkers (serum-procollagen type I N-propeptide—P1NP, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.504; serum beta C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen—β-CTX—p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.074, and their ratio—P1NP/β-CTX—p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.605). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) decreased more in Aecc (p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.584) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in Max (p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.471). Both groups similarly improved body composition and muscle function. Bone mineral density was generally unchanged. Overall, curcumin supplementation enhanced the benefits of high-RT programs (further glutathione increase in Aecc [Hedge’s g: 0.49]; IL-6 decrease in both modalities [Hedge’s g: 0.48–1.27]; decrease in TNF-α in controls [Hedge’s g: 0.47]; better outcomes in P1NP/β-CTX in all groups [Hedge’s g: 0.46–1.46]; among others). Conclusions: Aecc is recommended for supporting antioxidant capacity and bone health, while the choice between Aecc and Max may depend on the individual’s inflammatory profile. Curcumin supplementation further amplifies the benefits of both RT protocols across most outcome variables.

1. Introduction

Aging features a chronic, systemic pro-inflammatory state—“inflammaging” [1]. This pathological condition is characterized by the predominance of pro-inflammatory cytokines over anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha [TNF-α] and interleukin-6 [IL-6]). It is linked to type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, and age-related muscle degeneration [2,3]. A key mechanism is redox imbalance—excess reactive species relative to antioxidant defenses (e.g., glutathione)—leading to oxidative stress [4,5]. Specifically, reactive species accumulation is thought to activate Nuclear Factor-kappa B (NF-κB), increasing transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines [2,4]. Conversely, inflammaging augments reactive species production via prostaglandin biosynthesis, amplifying oxidative stress and tissue damage [6]. This bidirectional loop helps determine aging trajectories, distinguishing healthy from pathological aging.

Maintaining bone health is a key objective of healthy aging, as its deterioration can significantly reduce the quality of life by leading to decreased mobility, increased dependence, and greater frailty [7]. Bone health can be measured, among other techniques such as densitometry, by evaluating blood levels of the main reference markers of bone formation (serum-procollagen type I N-propeptide (PINP)) and one of bone resorption (serum beta C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen (β-CTX)) [8]. As people age, the balance between bone formation and resorption during the bone remodeling process becomes increasingly negative [9]. While various hypotheses have been proposed to explain this negative balance, increasing evidence points to chronic, low-grade inflammation—characteristic of inflammaging—as a key contributing factor [10,11,12,13]. Previous studies have shown that elevated levels of pro-inflammatory markers are a driving force behind the pathological changes observed in the bones of older individuals. Among these markers, the cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 are two of the most studied in relation to bone metabolism and morphological biomarkers [10,11,12,13]. IL-6 is central in activating and maintaining the inflammatory response and is a predictor of postmenopausal bone loss (4). Additionally, both IL-6 and TNF-α can regulate bone metabolism through the endocrine system (4). Treatment with TNF-α inhibitors has been shown to positively influence bone turnover markers by increasing levels of P1NP (marker of osteoblast activity, bone formation) and β-CTX (marker of osteoclast activity, bone resorption) in adults ≈45 years old with inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions [13,14]. Additionally, higher IL-6 levels have been associated with lower bone mineral density (BMD) in the hip among postmenopausal women [12] and in the lumbar spine among elderly men and women with osteoporosis/osteopenia [10,11]. In light of the profound impact bone deterioration can have on the elderly, prioritizing the development of effective interventions to suppress the undesirable effects of inflammaging is imperative.

Another undesirable age-related pathological change commonly reported in older individuals is the progressive loss of muscle mass, strength, and performance—the three principal components of sarcopenia [15]. Although these progressive pathological changes in muscle health involve complex interactions, such as hormonal imbalance, neuromuscular junction degeneration, and protein synthesis imbalance [16], inflammaging, once again, emerges as one of the main contributing factors. Chronic elevation of TNF-α, in particular, has been identified as a critical endocrine stimulus contributing to contractile dysfunction and inhibiting myogenesis, ultimately leading to muscle atrophy [17,18]. Similarly, persistently high levels of IL-6, often observed in pathological conditions such as cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases, have been linked to accelerated muscle wasting [19,20,21]. Furthermore, numerous studies have reported inverse associations between elevated TNF-α [22,23,24] and IL-6 [16,24,25,26,27] levels and muscle mass, strength, and performance, reinforcing the role of these cytokines as potential biomarkers of sarcopenia in older adults. However, while evidence consistently supports the pathological role of chronic TNF-α and IL-6 elevation, recent meta-analytic findings suggest that IL-6 alone may not be sufficient to induce the catabolic processes leading to muscle wasting. Instead, such effects appear to require the concurrent activity of other cytokines such as TNF-α [24]. Therefore, it seems important to take into consideration both IL-6 and TNF-α or other cytokines when exploring the link between inflammaging and muscle health.

Considering the link between inflammaging, oxidative stress, and musculoskeletal health in older adults [1], research on therapies is warranted. Most treatments rely on pharmacological interventions, dietary modifications, and supplementation with variable effectiveness [28]. Among non-pharmacological options, regular physical activity and diet consistently reduce inflammaging and oxidative stress and benefit physiology (e.g., gut microbiome) and related pathologies [29,30,31,32]. Evidence supports multiple exercise modes—aerobic and concurrent [29,33], high-intensity interval training (HIIT) [33], and resistance training (RT) [34]—to reduce inflammaging in healthy older adults and in those with inflammation-related conditions. Mechanisms include reduced adiposity; monocyte TNF-α inhibition; contraction-induced myokine release (e.g., IL-6) with lower TNF-α and higher IL-6 antagonists; macrophage shift from pro-inflammatory (M1) to anti-inflammatory (M2); toll-like receptor-4 downregulation; and increased antioxidant capacity (e.g., glutathione), yielding a more balanced cytokine profile and underscoring the regulatory role of structured exercise [34]. Beyond these indirect effects on bone and muscle, physical activity also confers direct, well-established tissue benefits: in bone, mechanical loading activates osteocytes via bone-lining networks, increasing formation markers and decreasing resorption markers [35]; in muscle, mechanical stress stimulates myofibrillar protein synthesis, slowing sarcopenic progression [36].

Although regular physical activity is widely recognized as an effective strategy for reducing inflammaging and oxidative stress, as well as enhancing bone and muscle health in older adults, there is still ongoing debate regarding which exercise modality offers the greatest overall benefit. For instance, aerobic endurance training has been shown to effectively reduce inflammaging and oxidative stress [37,38] but appears less effective in promoting bone and muscle health [39,40]. In contrast, RT is often favored for improving bone density and muscle mass [41,42,43], but emerging evidence indicates that it can also reduce chronic inflammation in older adults [39]. Eccentric RT has traditionally been avoided in older populations due to concerns about its potential to increase oxidative stress at high intensities [44,45]. However, emerging studies suggest that the response to eccentric RT is comparable to traditional RT and may offer significant benefits for health and function [46,47]. Despite its benefits, there is a lack of studies investigating the effects of eccentric RT in older adults’ bone health, inflammation, and oxidative stress, with only one study assessing the potential of descending stair walking on older adults’ bone mineral density (BMD) [48]. Similarly, another study used eccentric cycling to evaluate oxidative stress adaptations [45]. Therefore, studies applying eccentric loads through traditional RT movements are warranted.

Reasons that prevent older adults from performing eccentric or traditional RT include perceived barriers, including the reliance on gym-based equipment, the subjective difficulty of RT exercises, and the costs associated with gym membership [49]. A promising alternative, therefore, is performing RT using more affordable and user-friendly equipment such as elastic bands, which have been shown to elicit muscle and bone adaptations comparable to traditional RT methods [50,51,52,53]. Additionally, elastic bands, due to the elongation coefficient, provide greater resistance in the parts of the range of motion that are more biomechanically advantageous and less resistance in the most biomechanically disadvantageous parts of the movement in which the participants are “weaker” [54]. However, to our knowledge, no studies have specifically investigated the effects of elastic band RT on markers of inflammaging in older adults. This presents an important opportunity for research into a modality that may simultaneously target inflammaging, oxidative stress, and musculoskeletal health, while remaining accessible and appealing to older adults.

In efforts to mitigate the negative effects of inflammaging and oxidative stress, and to improve musculoskeletal health in older adults, various exercise protocols have been combined with diverse supplementation strategies in pursuit of optimal health outcomes [55,56,57,58]. Among them, curcumin supplementation in doses of 9.6–2100 mg/day proved to be a good adjunct when it comes to boosting antioxidative capacity [59], managing inflammation-related conditions such as metabolic syndrome [60], diabetes [61], rheumatoid arthritis, and other age-associated inflammatory diseases [62]. Also, it has been used effectively in doses of 69–110 mg/day along with other supplements to improve bone health [63,64] and muscle homeostasis [65]. Oral curcumin exhibits poor systemic bioavailability due to extensive intestinal conjugation and rapid hepatic metabolism [66]. To avoid this and increase curcumin absorption, formulations such as CursolTM include Tween 80 (Polysorbate 80), which improves solubility and stability in the gastrointestinal tract [67].

Therefore, the aim of this randomized, double-blind trial was to evaluate the effects of two high-RT protocols (accentuated eccentric [Aecc] and traditional concentric-eccentric [Max]) combined with curcumin supplementation on antioxidant capacity, systemic inflammation, bone and muscle health, and body composition in sedentary older adults. We hypothesized that both high-RT programs would effectively improve all dependent variables and that these improvements would be further enhanced by curcumin supplementation. However, no specific hypothesis was formed regarding which of the two protocols (Aecc or Max) would be more effective due to the absence of relevant comparative studies for this population. Compared with previous trials that have combined exercise and curcumin in older adults, the present study is, to our knowledge, the first randomized, double-blind intervention to contrast two high-resistance elastic band protocols—maximal strength and accentuated eccentric training—while testing the isolated effects of a bio-optimized curcumin formulation on an integrated panel of oxidative stress, inflammaging, bone turnover, bone morphology, and muscle function outcomes. This design enables a more comprehensive evaluation of how specific high-load RT modalities, delivered with accessible equipment, may be potentiated by curcumin supplementation in sedentary older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

This randomized, longitudinal, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at the facilities of the University of Valencia (Valencia, Spain), in collaboration with the Faculty of Physical Activity and Sport Science and the Faculty of Nursing.

2.1. Participants

A total of 81 participants completed the study protocol (age: 68.2 ± 4.6 years; weight: 71.3 ± 11.3 kg; height: 164.9 ± 6.8 cm; body mass index: 26.4 ± 4.8 kg/m2). The sample size was determined through an a priori power analysis using G*Power (Version 3.1.9.3), which indicated that a minimum of 60 participants was required to achieve 80% statistical power with a moderate effect size (f) of 0.25 for a three-way ANOVA with six groups. The effect size was calculated and used for all variables according to standard thresholds [68]. After baseline testing, participants were allocated to the six groups according to a computer-generated randomization sequence prepared by an independent researcher, which was implemented by external staff to ensure allocation concealment and preserve blinding of participants, assessors, and data analysts: (I) accentuated eccentric training with curcumin supplementation (Aecc-Cur; n = 16), (II) accentuated eccentric training with placebo (Aecc-Pla; n = 13), (III) maximum strength training with curcumin supplementation (Max-Cur; n = 10), (IV) maximum strength training with placebo (Max-Pla; n = 10), (V) control with curcumin supplementation (C-Cur; n = 15), and (VI) control with placebo (C-Pla; n = 17).

The trial was conducted as a double-blind, placebo-controlled supplementation study with blinded outcome assessment: participants, testing personnel, and data analysts were unaware of curcumin versus placebo allocation, whereas training staff were aware of the RT protocol (Aecc, Max, or control) for safety and supervision purposes but remained blinded to supplementation status and did not participate in outcome assessments or data analysis.

To be eligible for participation in the study, individuals had to be sedentary (not involved in programmed physical activity or exercise in the last six months), non-smokers, and non-alcoholic, aged over 60 years, while maintaining functional independence (i.e., able to walk and climb stairs unassisted). Additionally, participants were required to provide a medical certificate confirming their suitability for RT and to refrain from taking antioxidants (e.g., vitamins C, E, and A and omega-3, among others), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), or other supplements for at least six weeks before and during the study. Participants were excluded from the study if they had any disease or condition that could compromise their health, including severe visual or hearing impairment, a history of malignant neoplasms or terminal illness, significant body weight fluctuations exceeding 10%, or an intellectual disability (defined as a Mini-Mental State Examination score below 23). Additionally, individuals were ineligible if they had undergone medication therapy that could influence study outcomes (e.g., hormone replacement therapy, calcitonin, corticosteroids, glucocorticoids, allopurinol) or had participated in another study involving dietary, exercise, or pharmaceutical interventions within the past six months. Participants were informed about the potential risks and benefits of the study and provided written informed consent before enrolment. The study complied with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the University of Valencia Ethics Committee (IRB: 1861154, 5 May 2022). Additionally, the trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06620666, 30 September 2024).

2.2. Study Design

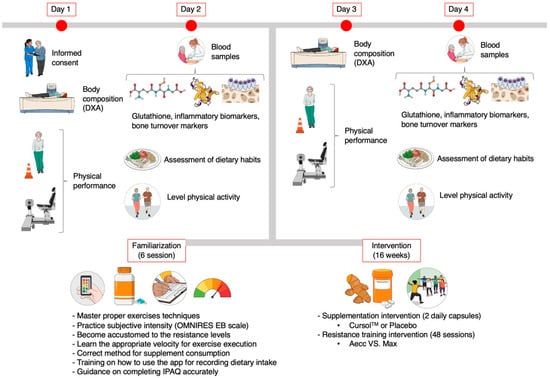

A longitudinal, double-blind study evaluated the effectiveness of two high-RT programs and curcumin supplementation on oxidative stress, inflammation, bone health, and muscle health-related parameters in older sedentary adults. All participant groups underwent initial and final testing, while the high-RT groups (Aecc-Cur, Aecc-Pla, Max-Cur, Max-Pla) also completed six familiarization sessions and a 16-week strength training program in between. Initial and final testing included blood sampling, DXA screening, and muscle performance assessments (See Figure 1 and Figure 2 for experimental setup). High-RT protocols were conducted three times per week, resulting in a total of 48 sessions over 16 weeks. The control group continued being sedentary, performing their routine daily activities. Each session lasted approximately one hour and was scheduled on non-consecutive days, at roughly the same time of day, under consistent environmental conditions.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of the study procedures. Created with Mindthegraph.com (accessed on 28 April 2025). DXA: Dual x-ray absorptiometry. IPAQ: International Physical Activity Questionnaire. EB: elastic band. Aecc: accentuated eccentric training. Max: maximum strength training.

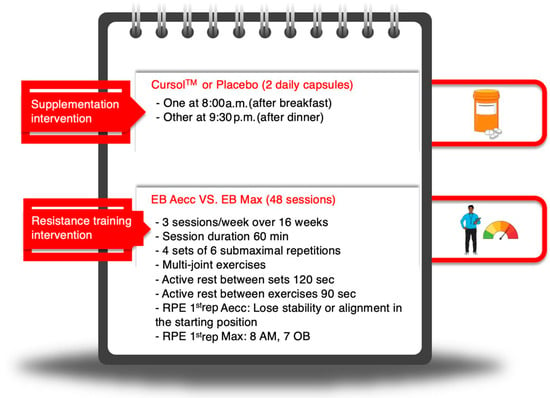

Figure 2.

Graphical summary of the supplementation and resistance training protocols. Created with Mindthegraph.com (accessed on 28 April 2025). EB: elastic band. Aecc: accentuated eccentric training. Max: maximum strength training. RPE 1st rep: rate of perceived exertion of the first repetition. AM: active muscles. OB: overall body. ‘8 AM’ and ‘7 OB’ refer to the perceptual cues used to adjust training intensity: an RPE of 8 for the perception in the active muscles (AM), and an RPE of 7 for the perception in the overall body (OB) for Max training. Min: minutes. Sec: seconds.

2.3. Testing Procedures

Both the initial and final testing sessions were conducted by staff members not involved in the high-RT protocols. Testing was carried out at the facilities of the University of Valencia and scheduled at approximately the same time for all groups. The interval between the initial and final testing sessions was approximately 18 weeks. The control group only completed the initial and final assessments. In contrast, the experimental groups completed both a familiarization phase (six sessions) and the high-RT program (16 weeks) during the period between the initial and final testing. Final assessments for the experimental groups were conducted 72 h following their last high-RT session. Each testing period was completed over two non-consecutive days.

On the first day, participants arrived at the Performance Laboratory of the Faculty of Physical Activity and Health Sciences between 8:30 and 10:00 a.m. Upon arrival, they were asked to rest in a comfortable chair to standardize baseline conditions. Participants were asked to keep their usual hydration habits and refrain from caffeine and alcohol consumption for 8 h before the performance testing. On the second day, participants were scheduled at the Faculty of Nursing, where a qualified nurse collected their blood samples. In order to reduce pre-analytical variability of the biochemical markers, the participants were scheduled at the same time of the day in the morning between 9 and 12 am and were instructed to fast and not consume any liquids at least 8 h before the blood collection.

2.3.1. Body Composition and Bone Health

Participants’ height was measured using a portable stadiometer (Seca GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany) and body weight using an electronic scale (Seca 878 model; Seca GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany). Later, whole-body fat-free (without bones) and fat mass, BMD, and T-scores of the femoral neck and Ward’s triangle were estimated using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (QDR® Hologic Discovery Wi, Hologic Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with APEX software (version 12.4, APEX Corp., Waltham, MA, USA). For these assessments, participants wore light clothing and removed all metallic items to avoid interference.

2.3.2. Muscle Function

Following this, participants completed an isokinetic concentric-concentric strength test involving five consecutive elbow flexions and extensions of the dominant arm at an angular velocity of 60°/s. The range of motion was set from 5° (near full extension) to 90° of elbow flexion. We measured peak isokinetic strength (N·m) with a Biodex dynamometer (Biodex Medical™, Shirley, NY, USA) using the Advantage software (version 3.2). Finally, aerobic endurance was assessed by the Six-Minute Walk Test as the number of meters that can be walked in 6 mins around a 30-m course, as described in the Senior Fitness Test Manual [69]. A practice try was allowed before the test to ensure validity [70].

2.3.3. Blood Collection and Biomarker Analysis

Blood samples were collected using two Vacutainer SSTs (i.e., serum-separating tubes that contain a gel at the bottom to separate blood cells from serum during centrifugation) and were centrifuged at 3000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min. The serum samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis was performed. All analysis procedures strictly adhered to the manufacturer’s instructions provided in the technical inserts of the commercial kits (AFG Bioscience, Northbrook, IL, USA) and LDN (Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG, Nordhorn, Germany). Samples for IL-6 and TNF-α were analyzed without prior dilution, whereas samples for glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1), PINP, and β-CTX were diluted at a ratio of 1:5 (one part sample to four parts diluent). Absorbance readings were taken at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 650 nm, according to the bichromatic reading protocol recommended by the manufacturer. The measurements were performed using a Labtec ELISA Microplate Reader LT-5000 ms (Labtec International LTD, East Sussex, UK).

Inflammation Markers and Antioxidants

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were used for analyzing IL-6 (ELISA kit IL E-3200; LDN Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG, Nordhorn, Germany), TNF-α (ELISA kit IL ref. IL E-3100; LDN Labor Diagnostika Nord GmbH & Co. KG, Nordhorn, Germany), and glutathione peroxidase levels (ELISA kit EK241437; AFG Scientific, Northbrook, IL, USA).

Bone Turnover

Biochemical bone health-related variables P1NP and β-CTX were analyzed using ELISA kit EK716118 and ELISA kit EK714439, respectively (AFG Bioscience, Northbrook, IL, USA). The sample concentrations were interpolated using four-parameter logistic (4PL) regression and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) for statistical validation. Procedures followed the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.

2.4. Training Programs

Before beginning the training program, participants completed six familiarization sessions aimed at mastering exercise techniques, becoming accustomed to subjectively evaluating exertion using the OMNI-RES scale, and familiarizing themselves with the appropriate movement velocity and repetition frequency. Following the familiarization phase, participants in the experimental groups completed a total of 48 training sessions over 16 weeks, with sessions held three times per week. Each training session included 5–10 mins of general warm-up, 40–50 mins of the main workout, and 5–10 mins of cool-down exercises, following the guidelines of the American College of Sports Medicine [71]. The main part of each training session consisted of performing four sets of six repetitions of lunges, standing horizontal chest presses, standing horizontal rows, and standing horizontal hip hinges. All exercises were performed using CLX elastic bands (TheraBand®; Hygenic Corporation, Akron, OH, USA). Rest periods between exercises lasted 90 s, while rests between sets lasted 2 min. These breaks were active and included low-intensity rhythmic coordination drills, dance routines, simple cognitive games, and similar activities designed to enhance adherence to the program.

The resistance during exercises was modified through two approaches (I) objectively, by using CLX elastic bands of different tension level and their combinations and adjustments to the starting position relative to the wall anchor, and (II) subjectively, taking into consideration participants’ perceived exertion using an OMNI-RES scale for elastic bands [72]. Floor markers were placed on the floor once the optimal resistance was determined during the first set of each exercise to ensure consistency in positioning between repetitions and sets.

Training intensity was standardized between Aecc and Max by equating exercise selection, number of sets and repetitions, rest intervals, and the brand/model of elastic bands. For both protocols, band tensions were individualized to elicit a target OMNI-RES rating of 8 in active muscles (and 7 for the overall body), corresponding to ~85% 1RM, with floor markers and a maximum elongation of 300% used to reproduce resistance across sets and sessions. Movement cadence was controlled with a metronome [72] (Aecc: unloaded concentric followed by a 5-s eccentric; Max: 2-s concentric and 2-s eccentric), such that contraction mode and time under tension differed by design and, at the same time, relative intensity was maintained within the same high-resistance range. All sessions were supervised by sports scientists. Both the Aecc and Max high-RT programs were designed in accordance with guidelines for older adults [73] and featured the following specific characteristics.

2.4.1. Accentuated Eccentric Elastic Band Program (Aecc)

Participants began each repetition close to the wall while holding the elastic band and performing the concentric phase of the movement without external resistance (e.g., extending their arms in front of the body at shoulder height and width). Afterward, they started walking further from the wall while maintaining the joint alignment achieved during the concentric phase. Once they could no longer maintain the joint position (e.g., elbows began to flex), a researcher positioned a marker on the floor. Afterward, the controlled 5s eccentric phase began (e.g., flexing their elbows). When participants completed the eccentric phase of the repetition, they were instructed to walk back to the initial position (close to the wall) within a 2-s window and to initiate the next repetition. Performing exercises following the described procedure allowed participants to exert 100% of their maximal capacity (i.e., the maximal resistance possible for a concentric phase), typically reaching a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) of 7 to 8 at the beginning of each set.

2.4.2. Maximal Strength Elastic Band Program (Max)

Participants began each set positioned close to the wall and gradually walked further until they perceived tension in the active muscles from the elastic band, corresponding to an RPE of approximately 8 (or 7 when considering overall body perception) at the start of each test [72,74]. Both RPE 7 and 8 corresponded to the intensity of approximately 85% of their one-repetition maximum [72]. Once the participants reached the optimal tension, the marker was positioned on the floor to ensure consistency of the repetitions during the remaining sets. Then, participants performed concentric and eccentric phases of the movement (e.g., elbow extension-flexion), each lasting 2 s. After completing all repetitions of a set, participants were instructed to return close to the wall and rest before beginning the next set. At no point did participants reach an RPE of 10.

2.5. Supplementation, Diet, and Physical Activity Monitoring

All participants were instructed to take two capsules per day [daily dose corresponds to 500 mg/day of CursolTM (10.50 mg/day of curcumin)], one in the morning after completing breakfast and the other in the evening after dinner. The content of the capsules for the curcumin-supplemented groups contained 250 mg of Cursol™, a bio-optimized curcumin formula with dual patents that ensure the preservation of its bio-active properties (Nutris We Care About You, Madrid, Spain). Cursol™ is standardized to contain 2.1% curcumin (5.25 mg), with the dosage aligned with established recommendations for human consumption [75,76,77]. Each Cursol™ capsule contains turmeric rhizome extract (Curcuma longa L.), dibasic calcium phosphate anhydrous (E341, stabilizer), Polysorbate 80 (E433, emulsifier), and citric acid (E330, acidity regulator). As reported by previous research [67], the addition of nonionic surfactant Tween 80 (Polysorbate 80) in Cursol™ significantly leads to the formation of liquid micelles, which enhances curcumin’s absorption and bioavailability by improving its solubility and stability in the gastrointestinal tract.

The placebo capsule was composed of 250 mg of maltodextrin and excipients (Life Pro Nutrition, Madrid, Spain). Both the curcumin and placebo capsules were matched for appearance, excipients, and labeling. Allocation to supplementation arms was centralized and handled by independent staff uninvolved in recruitment, testing, or analysis, ensuring concealment. Participants, outcome assessors, and data analysts were blinded to supplementation; training staff, who knew the assigned high-RT protocol for safety, remained blind to curcumin versus placebo and had no role in outcome assessment or data handling.

All participants were instructed to maintain their usual dietary and physical activity habits throughout the study. To monitor dietary intake, participants recorded their food consumption over three non-consecutive days (two weekdays and one weekend day) at both the beginning and end of the study. This was performed using the validated smartphone app MyFitnessPal (MyFitnessPal, LLC, CA, USA) [78]. Proper use of the MyFitnessPal app and accurate recording of dietary intake were supervised by an experienced nutritionist. This procedure allowed us to estimate total daily energy intake and macronutrient distribution (protein, carbohydrate, and lipids) for each participant and group. The physical activity was also assessed both at the beginning and at the end of the study using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).

2.6. Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness Control

Since accentuated eccentric and maximum strength RT may induce delayed-onset muscle soreness (DOMS), particularly in sedentary older individuals [79,80], the Category Ratio-10 Scale (CR-10) was used to examine its chronic effects in this population. Since sedentary older adults may experience greater DOMS and encounter limitations, especially during the initial phases of an Aecc or Max high-RT protocol due to the use of high loads [79], an adaptation period was implemented before administering the questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered and completed by participants in all training groups between weeks 5 and 9. Regarding the CR-10 scale, a value of 0 indicated “no pain”, while a value of 10 represented “maximum pain”. Participants were asked to report DOMS based on three different exercises: upper-body horizontal push, upper-body horizontal pull, and squat. For subsequent statistical analysis, an average DOMS score was calculated to generate an overall value for each experimental group.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test revealed that the fat-free mass, IL-6, TNF-α, glutathione, and Six-Minute Walk Test were the only variables that showed normal distribution. Although some dependent variables did not strictly meet the assumption of normality according to the Shapiro–Wilk test, a repeated-measures ANOVA was retained for the analysis. This decision is supported by recent evidence suggesting that the Shapiro–Wilk test should not be used as the sole criterion for selecting statistical methods, as its reliability can be affected by sample size [81]. Additionally, all variables presented homogeneous variances according to Levene’s test (all p > 0.060) and complied with the assumption of sphericity. Moreover, simulation studies have shown that ANOVA is robust to moderate violations of normality, particularly when the sample size per cell is adequate, as is the case in the present study [82]. Therefore, since all other assumptions (independence, homogeneity of variances) were met, a parametric approach was chosen for all variables, thus avoiding the loss of statistical power associated with the unnecessary use of non-parametric tests.

Considering its robustness, a three-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with time as a within-subject factor (pre-test vs. post-test) and group (Aecc vs. Max) and supplement (Cur vs. Placebo) as between-subject factors on the dependent variables, which were equalized between groups at the baseline. Subsequently, a three-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed on variables that were not equalized between the groups at the beginning of the study. This was performed by using baseline values of IL-6, TNF-α, glutathione, P1NP, β-CTX, and their ratio, BMD, and Ward’s triangle T-score, Six-Minute Walk Test, and isokinetic elbow flexion at 60º/s as covariates to eliminate the potential influence of initial differences on intervention outcomes [83,84]. In cases where a significant F-ratio was obtained, 95% confidence intervals were applied to examine the differences between the adjusted ANCOVA pre- and post-test scores within groups, as well as the post-test differences between groups. Finally, the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test was employed for post hoc comparisons, with effect sizes (ES) evaluated using partial eta squared (ƞp2).

Spearman’s rank-order correlation was employed to explore the correlations between the changes in the dependent variables following the intervention, calculated as the difference between post-intervention and pre-intervention values [85]. Changes in variables were computed as the difference between post- and pre-intervention values. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is defined as the smallest change in a variable that is considered meaningful and beneficial, justifying a treatment change, without causing significant side effects or high costs [86,87]. The MCID endpoints and cutoff points were extracted from previous literature similar in terms of intervention, outcome measure, and population [88]. MCID endpoints refer to specific levels of improvement associated with positive clinical effects, while cutoff points indicate thresholds to identify risks or classify participants. With these values in mind, we manually calculated the percentage of participants that achieved each endpoint/cutoff point.

The intention-to-treat approach was employed, wherein baseline measurements for participants who withdrew from the study were carried forward to the post-intervention phase to address missing data [89]. The qualitative interpretation of ƞp2 was as follows: values between 0.01 and 0.06 indicated a small effect, values from 0.06 to 0.14 represented a medium effect, and values greater than 0.14 corresponded to a large effect. ESs were calculated using Hedge’s g to account for potential small sample bias and interpreted based on Cohen’s guidelines: trivial effect (<0.20), small effect (0.20–0.50), moderate effect (0.50–0.80), and large effect (>0.80) [90]. Finally, correlations were qualitatively interpreted as 0.00–0.10 (negligible), 0.10–0.39 (weak), 0.40–0.69 (moderate), 0.70–0.89 (strong), and 0.90–1.00 (very strong). Statistical analyses were performed using the software package SPSS (IBM SPSS version 28.0.1.1 (14), Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive data are presented using means, standard deviations (SD), and percent difference (%Δ = [[post-test score–pre-test score]/pre-test score] × 100). Alpha was set at a p < 0.05 level.

3. Results

Training program attendance exceeded 87% across all training groups, with similar compliance with the supplementation regimen of approximately 89%. No participants sustained injuries or reported adverse effects from the study procedures. DOMS scores did not significantly differ between groups throughout the study (H range = 0.619–6.373, p range = 0.095–0.892). Participants from the experimental studies categorized their DOMS levels between “no pain” and “mild pain,” with mean values [range] as follows: Aecc+Cur: 0.68 [0.55–0.81], Aecc+Pla: 0.94 [0.88–1.05], Max+Cur: 1.07 [0.93–1.33], and Max+Pla: 1.58 [1.33–1.94].

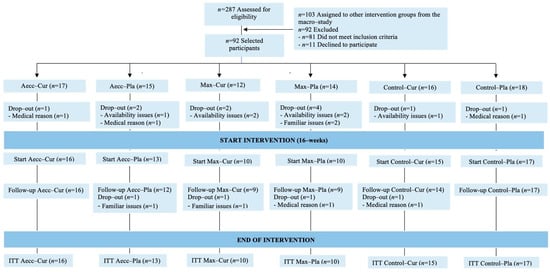

The final sample was composed of 57% females and 43% males. Participants could be classified as “minimally active” (<1500 MET-minute/week) according to IPAQ outcomes [91]. At the start of the training protocols, groups were matched for age, weight, height, BMI, weekly physical activity, and dietary intake (total calories, protein, carbohydrates, and lipids), and this equivalence was maintained throughout the program (p ≥ 0.161 for all variables). See Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for descriptive data. Figure 3 presents participant flow throughout the study.

Figure 3.

Participant flow throughout the study.

3.1. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Markers

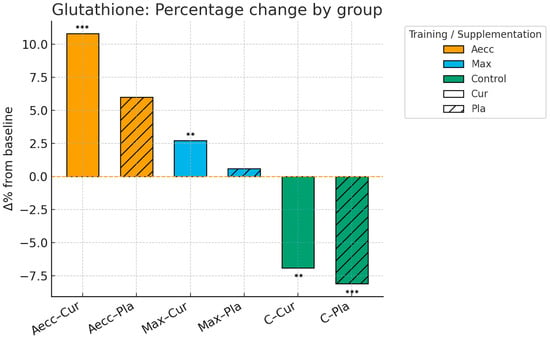

A significant time × group interaction was observed for glutathione levels (F = 28.11, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.438), indicating that high-RT programs affected participants differently over time, with the Aecc group showing a significant increase (F = 25.57, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.262), the Max-RT group showing no effect (F = 1.05, p = 0.307, ηp2 = 0.014), and the control group exhibiting a significant decrease (F = 30.40, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.297). A significant main effect of the group indicated that participants in the Aecc group increased glutathione levels significantly more than those in the Max-RT (p = 0.014) and control groups (p ≤ 0.001), while the Max-RT group also showed greater improvements compared to the control group (p ≤ 0.001). The interactions time × supplementation (F = 1.65, p = 0.203, ηp2 = 0.022), supplementation × group (F = 0.58, p = 0.565, ηp2 = 0.016), and the main effect of time (F = 1.95, p = 0.167, ηp2 = 0.026) and supplementation (F = 1.65, p= 0.203, ηp2 = 0.022) were non-significant. Pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Intervention effects on the oxidative stress and inflammatory parameters of each group.

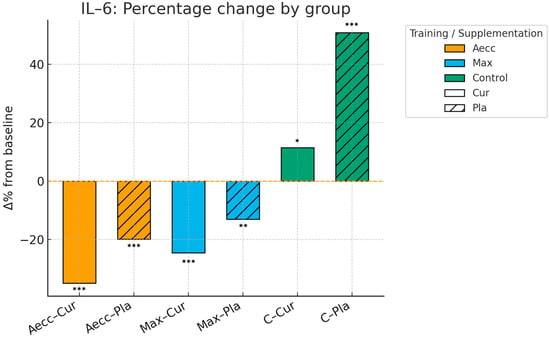

The time × group interaction was significant for IL-6 levels (F = 69.65, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.653), indicating the largest reductions occurred in the Aecc groups (F = 103.72, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.584), followed by the Max groups (F = 27.13, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.268), while the control group showed an increase (F = 47.81, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.392). The time × supplementation interaction was also significant (F = 29.13, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.282), indicating that participants receiving curcumin experienced significant reductions in IL-6 levels over time (p ≤ 0.001), whereas no change was observed in the placebo group (p = 0.921). Main effects for time (F = 39.02, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.345), group (F = 69.65, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.653), and supplementation (F = 29.13, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.282) were all significant, highlighting that the greatest reductions in IL-6 occurred at post-test, particularly in the Aecc groups and among participants who received curcumin. The supplementation × group interaction was not significant (F = 1.53, p = 0.223, ηp2 = 0.040).

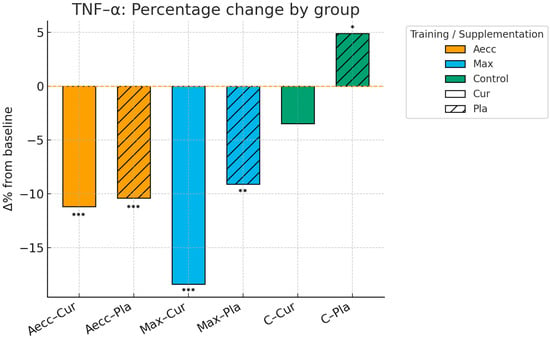

The time × group interaction was also significant for TNF-α levels (F = 23.94, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.393), indicating differential changes across groups. The Max group showed the largest reduction (F = 65.77, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.471), followed by the Aecc group (F = 40.30, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.353), while the control group showed no change (F = 0.07, p = 0.797, ηp2 =0.001). The time × supplementation interaction was also significant (F = 20.91, p = 0.012, ηp2 = 0.083), indicating greater reductions in TNF-α levels among participants who received curcumin compared to those in the placebo group (p = 0.012). Significant main effects were found for time (F = 24.91, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.252), group (F = 23.94, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.393), and supplementation (F = 0.01, p = 0.012, ηp2 = 0.083), showing that the highest reductions in TNF-α were observed at post-test, especially in the Max groups and among those receiving curcumin. The supplementation × group interaction was not significant (F = 1.29, p = 0.281, ηp2 = 0.034). Detailed pairwise comparisons are provided in Table 1 and Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Pre–post percentage change by group in glutathione. Significance markers: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Aecc-Cur: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + curcumin supplementation group; Aecc-Pla: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + placebo group; Max-Cur: elastic band maximum strength training + curcumin supplementation group; Max-Pla: elastic band maximum strength training + placebo group; C-Cur: control + curcumin supplementation group; C-Pla: control + placebo group.

Figure 5.

Pre–post percentage change by group in interleukin-6. Significance markers: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Aecc-Cur: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + curcumin supplementation group; Aecc-Pla: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + placebo group; Max-Cur: elastic band maximum strength training + curcumin supplementation group; Max-Pla: elastic band maximum strength training + placebo group; C-Cur: control + curcumin supplementation group; C-Pla: control + placebo group.

Figure 6.

Pre–post percentage change by group in tumor necrosis factor alpha. Significance markers: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Aecc-Cur: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + curcumin supplementation group; Aecc-Pla: elastic band accentuated eccentric training + placebo group; Max-Cur: elastic band maximum strength training + curcumin supplementation group; Max-Pla: elastic band maximum strength training + placebo group; C-Cur: control + curcumin supplementation group; C-Pla: control + placebo group.

3.2. Bone Health

A significant time × group interaction was observed (F = 49.30, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.578), indicating differential changes in the P1NP/β-CTX ratio across groups. The Aecc groups showed the greatest improvement (F = 110.51, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.605), followed by the Max groups (F = 61.00, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.459), while the control groups demonstrated a significant decrease (F = 55.90, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.437). A significant time × supplementation interaction was found (F = 28.11, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.281), with curcumin-supplemented participants showing significant post-test improvements in the P1NP/β-CTX ratio (F = 79.47, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.525), while no change was observed in the placebo group (F = 1.96, p = 0.166, ηp2 = 0.027). Significant main effects were observed for time (F = 6.18, p = 0.015, ηp2 = 0.079), group (F = 49.30, p≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.578), and supplementation (F = 28.11, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.281), indicating that the highest P1NP/β-CTX ratios were observed at post-test, particularly in the Aecc groups and among participants who received curcumin supplementation. The group × supplementation interaction was not significant (F = 0.80, p = 0.452, ηp2 = 0.022).

A significant time × group interaction was observed (F = 44.76, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.547), indicating differential changes in the P1NP across groups. The Aecc groups showed the greatest improvement (F = 75.18, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.504), followed by the Max groups (F = 39.62, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.349), while the control groups demonstrated a significant decrease (F = 25.12, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.253). A significant time × supplementation interaction was found (F = 11.42, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.134), with curcumin-supplemented participants showing significant post-test improvements in the P1NP (F = 49.01, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.398), while minor changes were observed in the placebo group (F = 4.65, p = 0.034, ηp2 = 0.059). Significant main effects were observed for time (F = 12.14, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.141), group (F = 44.76, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.547), and supplementation (F = 11.42, p= 0.001, ηp2 = 0.134), indicating that the highest P1NP improvements were observed at post-test, particularly in the Aecc groups and among participants who received curcumin supplementation. The group × supplementation interaction was not significant (F = 0.58, p = 0.565, ηp2 = 0.016).

A significant time × group interaction was observed (F = 3.34, p = 0.041, ηp2 = 0.088), indicating differential changes in the β-CTX across groups. The Aecc groups showed the greatest improvement (F = 5.49, p = 0.022, ηp2 = 0.074), followed by the Max groups (F = 4.21, p = 0.036, ηp2 = 0.067), while the control groups demonstrated a significant increase (F = 16.99, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.198). A significant time × supplementation interaction was found (F = 5.61, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.075), with curcumin-supplemented participants showing significant post-test improvements in the β-CTX (F = 33.83, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.329), while minor changes were observed in the placebo group (F = 5.54, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.074). Significant main effects were observed for time (F = 135.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.662), group (F = 3.34, p = 0.041, ηp2 = 0.088), and supplementation (F = 5.61, p = 0.021, ηp2 =0.075), indicating that the highest β-CTX improvements were observed at post-test, particularly in the Aecc groups and among participants who received curcumin supplementation. The group × supplementation interaction was significant (F = 6.43, p = 0.003, ηp2 = 0.157).

A significant time × group interaction was observed for femoral neck BMD (F = 4.83, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.114), femoral neck T-score (F = 4.92, p = 0.010, ηp2 = 0.116), and Ward’s triangle T-score (F = 5.37, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.125), indicating greater improvements in the experimental groups compared to the control groups in these morphological measures. The main effect of time was also significant for the femoral neck T-score (F = 7.68, p = 0.007, ηp2 = 0.093) and Ward’s triangle T-score (F = 6.72, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.082), reflecting post-test improvements in bone density. In contrast, the main effects of group (all F ≤ 1.55, p ≥ 0.220, ηp2 ≤ 0.040), supplementation (all F ≤ 1.29, p ≥ 0.259, ηp2 ≤ 0.017), time × supplementation interaction (all F ≤ 1.51, p ≥ 0.223, ηp2 ≤ 0.020), and supplementation × group interaction (all F ≤ 0.72, p ≥ 0.493, ηp2 ≤ 0.019) were non-significant. Detailed pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Intervention effects on the bone health-related variables.

3.3. Muscle Function

The interaction time × group was significant for all variables, including the Six-Minute Walk Test (F = 68.29, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.646), elbow flexion strength (F = 159.67, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.810), elbow extension strength (F = 130.00, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.776), fat-free mass (F = 121.30, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.764), and fat mass (F = 162.06, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.812) indicating greater improvements in the experimental groups compared to the control groups across all outcomes. The interaction time × supplementation was also significant for elbow flexion strength (F = 15.67, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.173), elbow extension strength (F = 5.19, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.065), fat-free mass (F = 17.17, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.186), and fat mass (F = 8.52, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.102), but not for the Six-Minute Walk Test (F = 3.61, p = 0.061, ηp2 = 0.046), suggesting greater gains in muscle-related outcomes among curcumin-supplemented participants compared to the placebo group, with no significant effect on walking performance. The main effect of time was significant for all variables—Six-Minute Walk Test (F = 98.47, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.568), elbow flexion strength (F = 584.55, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.886), elbow extension strength (F = 466.82, p ≤ 0.001, ηp2 = 0.862), fat-free mass (F = 5.93, p = 0.017, ηp2 = 0.073), and fat mass (F = 290.55, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.795)—reflecting overall post-test improvements in muscle health. A significant main effect of group was found for the Six-Minute Walk Test (F = 3.69, p = 0.030, ηp2 = 0.090), elbow extension strength (F = 5.14, p = 0.008, ηp2 = 0.121), and fat-free mass (F = 3.75, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.091), indicating superior outcomes in the Six-Minute Walk Test in the Aecc high-RT group compared to the control, and higher elbow extension strength and fat-free mass in both Aecc and Max high-RT groups relative to the control. No significant group effect was observed for elbow flexion strength (F = 2.47, p = 0.091, ηp2 = 0.062), although pairwise comparisons showed higher elbow flexion strength in the Aecc group compared to the control (p = 0.037). Additionally, neither the main effect of supplementation (all F ≤ 1.69, p ≥ 0.198, ηp2 ≤ 0.022) nor the supplementation × group interaction (all F ≤ 0.65, p ≥ 0.524, ηp2 ≤ 0.017) reached significance. Detailed pairwise comparisons are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intervention effects on the functional and muscular capacities of each group.

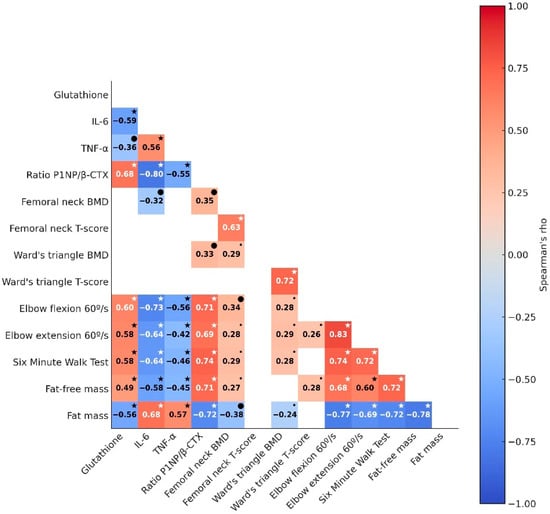

3.4. Bivariate Correlation Analysis (Spearman’s ρ)

Significant weak-to-strong correlations were observed among most of the dependent variables (Figure 7). Specifically, antioxidant capacity (glutathione) demonstrated an inverse correlation with inflammation (IL-6: ρ = −0.59, p ≤ 0.001; TNF-α: ρ = −0.36, p ≤ 0.01), suggesting that increased antioxidant capacity is associated with reduced systemic inflammation. Additionally, IL-6 and TNF-α displayed a moderate and positive correlation (ρ = 0.51, p ≤ 0.001), reinforcing their interrelated role as key inflammatory markers.

Figure 7.

Association between changes in dependent variables before and after the intervention. Significance markers: smaller or larger “•” represent p < 0.05 or p < 0.01, respectively; * p < 0.001. The correlation magnitude is represented by color intensity, ranging from negative (red) to positive (blue), with Spearman’s ρ displayed. Non-significant correlations are omitted. IL-6, Interleukin-6; TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha; P1NP, Type I procollagen N-terminal propeptide; β-CTX, beta C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen; BMD, bone mineral density.

Markers of oxidative stress and inflammation were significantly correlated with bone turnover biomarkers (ρ range = |0.55| to |0.80|) and muscle health markers (ρ range = |0.43| to |0.73|), generally showing moderate to strong associations, while their correlations with bone-health-related morphological parameters were mostly non-significant. Notably, bone turnover biomarkers were significantly and moderately to strongly associated with muscle health variables (ρ range = |0.69| to |0.74|).

3.5. Clinical Relevance

At least 50% of participants across the four experimental groups (Aecc or Max combined with either the supplement or placebo) reached the predefined endpoints or remained within acceptable cutoff values in at least 8 out of the 14 dependent variables. These benefits encompass reduced physical impairment, improved bone health, and a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, all of which collectively contribute to a decreased overall mortality risk. Importantly, all clinically relevant effects in the curcumin-supplemented groups were equal to or greater than those observed in the corresponding placebo groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentage of participants who have reached the predefined endpoints or remained within acceptable cutoff values.

4. Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the effectiveness of two high-RT protocols (Aecc vs. Max) on antioxidative capacity, systemic inflammation, bone health, and muscle function in older adults, and to determine whether these effects could be further enhanced by curcumin supplementation. The main findings revealed that: (I) antioxidant capacity, indicated by elevated glutathione levels, increased most significantly following the Aecc high-RT protocol; (II) the two inflammatory markers responded differentially—IL-6 decreased more substantially with the Aecc program, whereas TNF-α showed a greater reduction following the Max high-RT protocol; (III) the Aecc protocol was more effective in improving the P1NP, β-CTX, and their ratio, indicating a favorable shift in the balance between bone formation and resorption, while the remaining bone health morphological variables improved similarly—but to a lesser extent—with both the Aecc and Max high-RT protocols; (IV) overall, both programs similarly improved muscle function-related variables and body composition, with Max high-RT being more effective in improving elbow extension and fat mass, and (V) the associations between the improvements in antioxidative activity and inflammatory profile were highly associated with the improvements in the P1NP/β-CTX biomarker ratio and muscle health. These results suggest that the Aecc high-RT program may be preferable for enhancing overall health, including antioxidant capacity and bone health. Depending on the inflammatory profile, the results favor Aecc or Max—Aecc was more effective in reducing IL-6, and Max showed a greater impact on TNF-α. Additionally, the benefits of high-RT programs were enhanced by curcumin supplementation, which acted as a valuable ally by boosting the positive effects of both protocols across nearly all dependent variables.

4.1. Direct Effects of High-Resistance Training (Aecc, Max, Control)

Both high-RT programs demonstrated beneficial effects on antioxidative capacity in healthy older adults. These results align with previous research highlighting the advantages of nearly all forms of regular physical activity as effective non-pharmaceutical strategies to counteract age-related oxidative stress by upregulating antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase [37,100,101]. In addition, extensive evidence shows that resistance and power training are well-established stimuli for improving bone density, muscle strength, and muscle mass in older adults [102,103], reinforcing the role of exercise as the primary driver of musculoskeletal adaptations. However, contrary to the commonly held belief that eccentric RT may have a detrimental impact on the oxidative capacity of the elderly [44], our results revealed significantly higher glutathione levels in the Aecc group compared to the Max group. Despite these benefits, eccentric training is often avoided in older adults due to concerns about increased oxidative stress [44]. However, our results demonstrated that Aecc training not only improved antioxidative activity levels but also attained improvement to a greater extent than the Max high-RT protocol. This supports the hypothesis proposed by Nikolaidis et al. [46] regarding the oxidative stress safety of eccentric training in the elderly; older adults experience elevated oxidative stress at rest compared to younger counterparts, but obtain similar training adaptations. This suggests that older adults can adapt to and benefit from exercise programs that include eccentric muscle contractions, which have similar characteristics to the Aecc high-RT program in our study, where, in particular, the progressive resistance of the elastic bands throughout the range of joint motion might have contributed to a favorable stimulus. Additionally, it could be that the longer time under tension of Aecc (5 s per repetition) compared to Max (4 s per repetition) shaped the outcomes, although it was not an aim of the study, and future study designs may confirm whether time under tension during high-RT can modulate antioxidant responses.

Similarly, high-RT programs showed beneficial effects in reducing inflammatory cytokines, although their effectiveness varied depending on the specific cytokine targeted. The values encountered in the inflammatory markers are common to healthy populations (e.g., IL-6 between 0 and 43.5 pg/mL), although with a certain level of low-grade inflammation [104,105]. Notably, the Aecc protocol was more effective in reducing IL-6 levels, whereas the Max protocol was more effective in lowering TNF-α. This distinction may be due to the differing biological roles, secretion mechanisms, and tissue sources of these cytokines. Recent literature increasingly identifies IL-6 as an “exercise-induced myokine” that plays a key role in muscle-organ communication and contributes to the anti-inflammatory effects of physical activity [106]. Its secretion during exercise appears to depend on both the intensity and duration of the activity, with elevated IL-6 responses observed following sessions characterized by high lactate accumulation and glycogen depletion [107]. In this context, the longer time under tension experienced by the Aecc group may have led to greater metabolic stress, potentially explaining the more pronounced reductions in resting IL-6 levels observed in this group. Conversely, TNF-α seems to be less directly influenced by the exercise stimulus itself. Its reduction has been more strongly associated with reductions in fat mass and leptin, alongside increases in adiponectin and insulin sensitivity [108]. The greater TNF-α decrease observed in Max groups compared to Aecc could be due to macrophages being the main source of TNF-α secretion and adipocytes also being involved [109,110]. Macrophages are involved in muscle regeneration and hypertrophy [111], therefore, the greater decrease in resting TNF-α levels observed in the Max groups may be related to the more substantial increase in body fat-free mass—which includes muscle mass—and strength compared to the Aecc groups and the greater decrease in fat mass for Max group (12.7%) compared to Aecc (9.7%).

The favorable shift in the balance between bone formation and resorption, as indicated by the P1NP, β-CTX, and their ratio, was also positively influenced by both high-RT interventions. However, the improvements in these parameters were more pronounced in participants of the Aecc groups compared to those in the Max high-RT groups. Previous studies have reported inconclusive findings on this topic. For example, while some studies reported that 16-week [112] or 32-week [113] RT programs had no significant effect on bone turnover markers (osteocalcin, skeletal alkaline phosphatase, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, CTX, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand), others found positive changes in marker ratios (bone alkaline phosphatase and CTX) after just 6 weeks of high-RT or low-load RT combined with blood flow restriction [114]. Although participant profiles and the use of whole-body high-RT protocols were comparable between our study and those reporting no changes [112,113], the bone turnover markers used to calculate the ratio were different; this was also the case for the specificities of the RT programs, which might potentially explain the differences in the reported results. While our study utilized P1NP, β-CTX, and their ratio, others employed markers such as bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, CTX, and their ratio [114], osteocalcin, skeletal alkaline phosphatase, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, CTX, osteoprotegerin, and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand [112,113]. Another key difference may be the mode of resistance used. In our study, participants trained with elastic bands, while previous studies primarily used free weights. Elastic bands are often considered more joint-friendly, an important factor for older adults, as they enable smoother and less painful execution of movements. Additionally, they provide variable resistance throughout the range of motion and may promote greater control and longer time under tension—factors potentially contributing to a more favorable osteogenic stimulus. This is consistent with established frameworks that consider mechanical loading the primary osteogenic signal in older adults [102,103].

Even though positive shifts in the bone formation/resorption ratio were achieved, especially under the Aecc high-RT protocol, improvements in femoral bone morphological parameters related to bone density were less evident. Although the experimental groups showed a more positive change over time in bone density maintenance compared to the control groups, statistically significant effects were observed in only two of the four bone morphological variables at the post-test–specifically, the femoral neck T-score and Ward’s triangle T-score. It is important to note that these two variables do not represent actual bone density values, but rather indicate the standard deviation from the average peak bone density of a healthy young adult [115]. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that biomarkers of bone metabolism, such as osteocalcin, serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, CTX, deoxypyridinoline, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, respond more rapidly to RT than do measurable changes in bone mineral density itself [116,117]. Moreover, it appears that achieving meaningful improvements in bone density—especially in older individuals—requires not only high training loads but also longer intervention periods. Most studies reporting significant gains in bone density employed training programs that lasted at least one year [118,119,120]. This may also explain why the observed changes in bone morphological variables did not significantly correlate with improvements in other dependent measures. In fact, the four bone morphological variables were among the six outcomes in which fewer than half of the participants experienced clinically meaningful changes.

All muscle function-related variables significantly improved following the intervention period in both training groups. No difference was observed between the two experimental groups in most of the muscle function-related variables; the Max high-RT protocol elicited greater improvements compared to the Aecc high-RT protocol in elbow extension and fat mass. These findings only partially align with previous research reporting superior gains in strength, function, and muscle mass from eccentric RT programs compared to traditional concentric or concentric-eccentric regimens [121,122]. Nevertheless, consistent with established physiological models, RT itself is recognized as the primary and most robust stimulus for improving muscle mass and functional capacity in older adults [103].

4.2. Effects of Curcumin Supplementation

Confirming our hypothesis, curcumin supplementation enhanced the positive effects of the high-RT protocols implemented in our study on almost all dependent variables. However, these effects should be interpreted cautiously, given the known limitations in the systemic bioavailability of orally administered curcumin, which may restrict the magnitude or physiological reach of its actions. Firstly, our findings demonstrate that curcumin supplementation increased glutathione-related oxidative activity, which supports previous research suggesting that curcuminoids exert their primary effect by neutralizing harmful free radicals and thereby boosting the antioxidant capacity of individuals [59]. It is also possible that some of these effects reflect local or indirect mechanisms rather than high systemic exposure, a point that warrants further investigation. Secondly, our results revealed a significant anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin supplementation, with reductions in inflammaging markers of up to 34% in the curcumin-supplemented high-RT groups, compared to a maximum of 19.9% in the placebo groups. These findings are further supported by existing literature, where curcumin is recognized as a valuable adjunct to exercise programs for managing inflammation-related conditions such as metabolic syndrome [60], diabetes [61], rheumatoid arthritis, and other age-associated inflammatory diseases [62]. Nonetheless, the relatively low dose used in our study compared with higher doses employed in clinical trials [123] may partly explain the moderate magnitude of some effects.

Notably, a novel contribution of our study is the consistent amplification of RT effects on bone turnover markers through curcumin supplementation. This was evidenced by significant differences between Aecc-Cur and Aecc-Pla (p = 0.024), as well as between Max-Cur and Max-Pla (p = 0.007). While previous studies have shown curcumin’s benefits for bone health (total body, total hip, lumbar spine, and femoral neck BMD, bone turnover biomarkers CTX, osteocalcin, osteopontin, and bone-specific alkaline phosphatase) primarily in combination with other supplements, such as alendronate [63], Nigella sativa oil [64], and ginger [124], our findings indicate that curcumin alone combined with RT, can yield significant improvements in bone turnover markers. Nevertheless, these results should be viewed as preliminary until future studies confirm whether the observed changes reflect systemic actions or more localized regulatory effects. In addition to its impact on bone metabolism, curcumin supplementation also amplified the positive effects of high-RT protocols on muscle function-related variables. However, the effects on bone morphology-related parameters were less conclusive, likely due to the relatively short duration of the intervention, which may have been insufficient to elicit measurable structural changes in bones. Finally, curcumin supplementation significantly magnified fat loss in both training groups. Previous research has suggested that curcumin can be important in the control of obesity by the regulation of oxidative stress, which, among other negative effects in the body, promotes lipogenesis and stimulates the differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes [125]. Still, without pharmacokinetic confirmation of circulating curcumin levels, the specific pathways underlying these changes cannot be fully determined.

4.3. Combined Interpretation and Limited Training × Supplementation Interactions

When considered jointly, the data indicate that high-resistance elastic band training—particularly Aecc—is the primary driver of improvements in muscle function, body composition, and bone turnover, whereas curcumin exerts a complementary systemic effect by augmenting antioxidant capacity and attenuating low-grade inflammation. In most outcomes, training × supplementation interactions were small or non-significant, suggesting predominantly additive rather than strongly synergistic effects. Nonetheless, the strongest health gains were observed when the mechanical loading stimulus of Aecc or Max was combined with curcumin, especially for the P1NP/β-CTX ratio, inflammaging markers, and fat mass. Importantly, the observed associations between changes in glutathione and inflammatory cytokines and changes in the P1NP/β-CTX ratio and muscle health underscore the mechanistic link between redox-inflammatory homeostasis and musculoskeletal integrity in older adults. From a practical perspective, these findings support the implementation of well-supervised high-RT programs—preferably including an accentuated-eccentric component delivered with elastic bands—as a core strategy for healthy aging, with curcumin supplementation serving as a valuable adjunct rather than a substitute for exercise.

4.4. Methodological Considerations and Limitations

Although involving a relatively hard-to-reach population, the 16-week randomized, double-blinded intervention was completed by 81 participants, highlighting the study’s strong retention and duration, though a few limitations should still be acknowledged. First, small and uneven group sizes warrant cautious interpretation. Unbalanced allocation across six arms likely reduced power to detect small-moderate effects, particularly for higher-order interactions, and the modest sample plus cohort specificity (sedentary, apparently healthy older adults) limit generalizability to broader clinical and multimorbid populations. Nevertheless, the systemic reporting of effect sizes (Hedges’ g, ηp2), and consistent biochemical and functional patterns enable readers to appraise the robustness and practical relevance of the findings despite these sample-size constraints.

Although we started measuring in the fourth week, measuring DOMS from the first week can help track adaptation patterns of older adults to different training methodologies. Additionally, the 16-week intervention is adequate mainly to detect early biochemical adaptations in bone metabolism rather than substantial BMD changes. Despite a high weekly mechanical stimulus (3 supervised high-resistance elastic band sessions/week, exceeding many longer-term RT trials), this window is suboptimal for robust densitometric gains in older adults. Accordingly, bone morphology outcomes are interpreted as maintenance or slight improvement rather than definitive long-term osteogenic remodeling, whereas clearer changes in bone-turnover markers are consistent with their shorter response windows. Future trials should include ≥ 12-month follow-up and/or repeated densitometric assessments to better characterize the time course of structural adaptations to high-resistance elastic band training with or without curcumin.

Therefore, the present outcomes, although reaching MCID, do not equate to proven reduction in clinical outcomes such as fractures, disability, or mortality, but rather general health and quality of life. Related to frailty prevention, having measured both upper and lower limb strength would have given a broader picture of potential clinical applicability.

Concerning supplementation, although conducted under a double-blind, placebo-controlled design with comparable training/supplement adherence and stable dietary and physical activity patterns, placebo-related behavioral changes cannot be fully ruled out. Supplement intake may elicit low-level expectancy effects (e.g., increased motivation, perceived program efficacy) that might have marginally influenced some between-group differences. Future trials should include explicit measures of treatment expectancy and motivation to better quantify and control these potential influences. Furthermore, we did not perform high-performance liquid chromatography analyses of curcumin or its metabolites to biochemically confirm intake and systemic exposure. Although adherence was monitored via capsule dispensing and supervised follow-up, the lack of direct pharmacokinetic confirmation means that absorption variability and occasional non-compliance cannot be ruled out. Future trials combining high-resistance training with curcumin should include high-performance liquid chromatography quantification of circulating curcuminoids to validate intake and characterize exposure–response relationships with oxidative stress, inflammation, and musculoskeletal outcomes. Furthermore, although dietary intake was monitored using a validated smartphone application and supervised by a nutritionist, the reliance on self-reported food records introduces well-known sources of error, such as underreporting and recall bias, which should be considered when interpreting the nutritional data.

Finally, our profiling was limited to IL-6, TNF-α, and glutathione-related activity, narrowing inference on systemic inflammatory tone and antioxidant defense. The lack of high-sensitivity-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and enzymatic antioxidants (e.g., catalase, superoxide dismutase) limits characterization of redox-inflammatory adaptations to the intervention. Future studies should use broader panels (hs-CRPS, catalase, superoxide dismutase, complementary redox indicators) to delineate how high-resistance elastic band training, with and without curcumin, modulates inflammatory and oxidative-stress networks in older adults.

4.5. Practical Applications

From an applied perspective, these findings suggest that high-RT elastic band programs—particularly Aecc—constitute a feasible, low-cost, and scalable option for inclusion in community and primary-care exercise prescriptions aimed at mitigating inflammaging, improving bone turnover dynamics, and preserving muscle function in sedentary older adults. The distinct patterns observed for IL-6 and TNF-α further support the future development of more individualized training prescriptions (Aecc vs. Max) according to patients’ inflammatory and body-composition profiles, while curcumin supplementation may be considered as an adjunct—not a substitute—to a structured high-RT program in contexts where additional anti-inflammatory and antioxidant support is clinically desirable. These results also provide a mechanistic and practical basis for longer-term trials in frail or multimorbid populations, for studies targeting hard clinical endpoints (e.g., fractures, disability), and for implementation research evaluating the integration of high-RT elastic band training, with or without curcumin, into existing osteoporosis and sarcopenia prevention programs.

5. Conclusions

The results support that in sedentary older adults, both high-resistance elastic band programs (Aecc, Max) improved inflammatory markers and functional outcomes vs. control. Aecc produced greater gains in antioxidant capacity (glutathione) and a more favorable bone turnover profile (increased P1NP and P1NP/β-CTX ratio, and decreased β-CTX), with larger IL-6 reductions, while Max yielded the largest TNF-α decreases. Bone morphology was unchanged over 16 weeks. Curcumin supplementation (500 mg/day, CursolTM) potentiated training with additional IL-6 (both modalities), TNF-α reductions (including control), improved P1NP/β-CTX ratio, greater strength and fat-free-mass gains, and lower fat-mass, but with no effect on the Six-Minute Walk Test. Overall, these findings suggest that combining high-RT with curcumin supplementation may provide complementary or synergistic benefits. However, causal mechanisms cannot be established from the current design. Longer-term trials that include pharmacokinetic verification of curcumin exposure are needed to confirm these effects and clarify their underlying mechanisms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152412862/s1. Table S1: Baseline characteristics. Table S2: Physical activity and nutritional intake.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-B., A.J., J.G.-M., P.J.-M., O.C., J.F.-G., C.A.-F., V.G., and J.C.C.; methodology, A.S.-B., A.J., P.J.-M., J.G.-M., and J.C.C.; validation, P.J.-M., and J.C.C.; formal analysis, A.S.-B., A.J., J.G.-M., D.J., and J.C.C.; investigation, A.S.-B., A.J., J.G.-M., O.C., J.F.-G., and J.C.C.; resources, J.C.C., P.J.-M., C.A.-F., O.C., and J.F.-G.; data curation, A.S.-B., A.J., P.J.-M., J.G.-M., and J.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.-B., D.J., P.J.-M., C.A.-F., A.J., J.G.-M., O.C., J.F.-G., and J.C.C.; writing—review and editing, A.S.-B., A.J., J.G.-M., D.J., V.G., and J.C.C.; visualization, A.S.-B., A.J., D.J., and J.C.C.; supervision, P.J.-M., and J.C.C.; project administration, J.C.C.; funding acquisition, J.C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Nutris We Care About You provided reagents for the development of the study; however, they were not involved in data collection or data entry, and there were no restrictions on analysis, writing, or publication. This work was supported by a grant from the Generalitat Valenciana (Angel Saez-Berlanga’s predoctoral grant CIACIF/2021/189, funded by the European Social Fund).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (protocol code 1861154 with an approval date of 5 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants for their commitment to the study, to Life Pro Nutrition Industries for providing the supplements, and to Nutris We Care About You for the reagents. Furthermore, we extend our gratitude to Alejandro Silvestre Herrero for his contribution to the data collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

Pablo Jiménez-Martínez, Carlos Alix-Fages, and Danica Janicijevic serve as scientific advisors for companies in the field of nutraceutical products and are part of Indiex Sport Nutrition SL. Veronica Gallo works for Nutris We Care About You. The rest of the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Aecc | Accentuated eccentric |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| β-CTX | Beta C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen |

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| C | Control |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| Cur | Curcumin |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| ES | Effect size |

| LSD | Least significant difference |

| Max | Maximal strength |

| MCID | Minimum clinically important difference |

| P1NP | Type I procollagen N-terminal propeptide |

| Pla | Placebo |

| RPE | Rating of perceived exertion |

| RT | Resistance training |

| SD | Standard deviations |

| SST | Serum-separating tube |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |