Abstract

Patients undergoing oral surgery are frequently polymedicated and preoperative prescriptions (analgesics, corticosteroids, antibiotics) can generate clinically significant drug–drug interactions (DDIs) associated with bleeding risk, serotonin toxicity, cardiovascular instability and other adverse events. This study prospectively evaluated whether large language models (LLMs) can assist in detecting clinically relevant DDIs at the point of care. Five LLMs (ChatGPT-5, DeepSeek-Chat, DeepSeek-Reasoner, Gemini-Flash, and Gemini-Pro) were compared with a panel of experienced oral surgeons in 500 standardized oral-surgery cases constructed from realistic chronic medication profiles and typical postoperative regimens. For each case, all chronic and procedure-related drugs were provided and the task was to identify DDIs and rate their severity using an ordinal Lexicomp-based scale (A–X), with D/X considered “action required”. Primary outcomes were exact agreement with surgeon consensus and ordinal concordance; secondary outcomes included sensitivity for actionable DDIs, specificity, error pattern and response latency. DeepSeek-Chat reached the highest exact agreement with surgeons (50.6%) and showed perfect specificity (100%) but low sensitivity (18%), missing 82% of actionable D/X alerts. ChatGPT-5 showed the highest sensitivity (98.0%) but lower specificity (56.7%) and generated more false-positive warnings. Median response time was 3.6 s for the fastest model versus 225 s for expert review. These findings indicate that current LLMs can deliver rapid, structured DDI screening in oral surgery but exhibit distinct safety trade-offs between missed critical interactions and alert overcalling. They should therefore be considered as decision-support tools rather than substitutes for clinical judgment and their integration should prioritize validated, supervised workflows.

1. Introduction

Patients undergoing oral surgery frequently take multiple medications, especially older individuals or those managing chronic systemic conditions like diabetes or cardiovascular disease [1,2,3]. The addition of typical perioperative drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen and other analgesics, corticosteroids, and antibiotics further increases the risk of clinically significant drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in this population [4,5]. These DDIs may result in adverse outcomes, including excessive bleeding, therapeutic failure, serious adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and, in severe cases, even emergency department visits or hospital admissions [6].

For example, combining warfarin (an anticoagulant) with antiplatelet agents amplifies the risk of hemorrhage several-fold [7,8]; coadministration of NSAIDs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) more than doubles the odds of gastrointestinal bleeding [9,10] and adding tramadol (an opioid) to SSRIs can precipitate serotonin syndrome [11,12]. Other medication classes often encountered in oral surgery patients that may increase the risk of DDI include antidiabetic drugs (such as GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors) [13], statins [14], antiepileptics [15,16] and antiresorptive osteoporosis drugs, which are associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) [17,18,19,20].

In oral surgery, the assessment of potential drug–drug interactions is not a leisurely academic exercise but a time-critical clinical judgment often made under pressure, frequently while patients are still in the chair and the surgical team must decide within minutes whether to proceed, substitute, adjust or defer treatment [21,22]. Compounding the challenge, dentists may lack access to patients’ full medication histories, which can result in missed or underestimated DDIs and increase the risk of DDI-related harm [23,24,25]. There is therefore an urgent need for tools that can support rapid, systematic, and reproducible DDI screening in the oral-surgery setting, without replacing clinicians’ judgement.

In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a promising clinical decision-support tool in dentistry [26,27,28]. Large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, Gemini and specialized systems like DeepSeek could rapidly analyze medication lists and cross-reference known interactions, providing comprehensive and standardized DDI screening at high speed and potentially streamlining preoperative prescribing workflows [29,30,31,32]. This capability may help reduce variability in the thoroughness of interaction checks across providers. Indeed, ChatGPT has shown high sensitivity, correctly identifying approximately 99% of DDIs in a recent evaluation [33].

However, current LLMs also exhibit notable limitations: they may “hallucinate” non-existent interactions and occasionally generate incorrect or unsupported information. Studies comparing ChatGPT, DeepSeek and similar models with reference databases have reported only moderate agreement regarding interaction severity, along with frequent inaccuracies in AI-generated recommendations [34]. All evaluated models showed low specificity (inability to reliably exclude absent interactions), underscoring that human expert verification remains essential.

While AI-driven DDI checks have been investigated in general medicine (intensive care and pharmacovigilance), no study has directly compared AI with clinicians in dentistry or oral surgery, fields in which robust DDI data remain scarce [35].

Addressing this gap, the present prospective, simulation-based study compares five LLMs with a panel of experienced oral surgeons. Using 500 standardized oral-surgery scenarios with predefined medication regimens, we assess each model’s ability to identify clinically meaningful DDIs, to classify their severity on an ordered scale, and to suggest appropriate management strategies, using the surgeon consensus as the reference standard. The overarching aim is to determine whether current general-purpose LLMs can provide reliable, chairside decision support for DDI screening in oral surgery while remaining subordinate to human clinical judgement.

2. Materials and Methods

This study compared the performance of five large language models (LLMs): DeepSeek-Chat and DeepSeek-Reasoner (DeepSeek, Hangzhou, China), Gemini-Flash and Gemini-Pro (Google DeepMind, London, UK), and ChatGPT-5 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA)—with that of a panel of experienced oral surgeons in identifying and managing potential drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in standardized oral-surgery scenarios. The primary endpoint was case-level accuracy for clinically significant DDIs; secondary endpoints included pair-level diagnostic performance, severity agreement, correctness of management advice, safety-critical errors, hallucinations and process metrics (API latency, token usage, human time-to-decision).

2.1. Study Design, Setting and Data Governance

A prospective, simulation-based, parallel evaluation was conducted on isolated workstations. DeepSeek-Chat and DeepSeek-Reasoner runs were executed on 14 July 2025; ChatGPT-5 runs were executed on 3 October 2025; Gemini-Flash and Gemini-Pro runs were executed on 10 October 2025. Internet access was restricted to API calls. The analysis plan and rubric were finalized before data generation. No real patient data were processed; all records were fully simulated and non-identifiable. Deterministic case generation (fixed random seeds), unique study IDs, immutable raw archives and timestamped logs (model names, API endpoints, parameters as set in code, request/response times) were maintained to support reproducibility and version transparency. This study was reported in accordance with the principles of the STARD 2015 guideline, adapted for simulation-based evaluation [36].

2.2. Case Generation and Clinical Scenarios

A corpus of 500 postoperative cases represented complex mandibular third-molar surgery. Each case included a fixed postoperative regimen (non-opioid analgesic; amoxicillin/clavulanate 875/125 mg orally, three times daily for short duration; a short corticosteroid course—e.g., betamethasone/Bentelan or prednisone, as clinically plausible) together with variable chronic medications. These agents were selected to mirror routine perioperative prescribing patterns in oral surgery and to recreate realistic chairside scenarios in which clinicians must rapidly evaluate potential drug–drug interactions.

Chronic medications spanned the following major therapeutic classes, which are commonly encountered in oral-surgery patients and clinically relevant for DDI risk:

- (i)

- Cardiovascular antihypertensives (ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, β-blockers, thiazide diuretics);

- (ii)

- Antidiabetic agents (metformin, SGLT-2 inhibitors such as empagliflozin, GLP-1 receptor agonists such as liraglutide, and sulfonylureas);

- (ii)

- Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies (aspirin, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, warfarin), which directly influence intra- and postoperative bleeding risk;

- (iv)

- Lipid-lowering drugs (atorvastatin, simvastatin, rosuvastatin);

- (v)

- Antidepressants (SSRIs/SNRIs such as sertraline, escitalopram, fluoxetine, duloxetine), relevant for serotonergic interactions with certain analgesics;

- (vi)

- Antiepileptics/neuromodulators (valproate, lamotrigine, pregabalin, gabapentin);

- (vii)

- Immunosuppressants (tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine);

- (viii)

- Acid-suppressive therapy (omeprazole, pantoprazole);

- (ix)

- Respiratory/allergy medications (e.g., montelukast);

- (x)

- Hormonal agents and contraceptives;

- (xi)

- Bisphosphonates and other antiresorptives (alendronate, ibandronate, denosumab), which are associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw;

- (xii)

- Hypnotics (e.g., zolpidem), among others.

To avoid unrealistic or clinically inconsistent scenarios, predefined plausibility checks were applied to all simulated cases. Cases showing implausible dose combinations or internal inconsistencies—for example, duplicate prescriptions of the same active ingredient at incompatible doses, or regimens unlikely to be used in routine oral-surgery practice—were identified and removed before analysis. Each record included age, sex, chronic medications and the corresponding English prompt, and records were stored in CSV/JSON format using deterministic generation scripts.

2.3. Interventions and Comparators

Automated comparators comprised DeepSeek-Chat, DeepSeek-Reasoner, Gemini-Flash, Gemini-Pro and ChatGPT-5, each accessed via the provider’s chat-completion API. Scripts supplied a concise system instruction (clinical pharmacology assistant) and a case prompt. Where temperature or other decoding controls were not explicitly set in code, provider defaults applied; all other parameters followed the script settings and remained constant across cases. This configuration ensured that each large language model received the same clinically formatted information and operated under stable, reproducible conditions throughout the simulation.

The human comparator consisted of three board-certified oral surgeons (each with >10 years of independent practice) from the Oral Surgery Unit. Each surgeon independently reviewed all 500 cases and assessed, for every case, the presence of any clinically relevant drug–drug interaction, the suspected mechanism, the clinical severity grade on the A–B–C–D–X scale and the recommended management strategy.

During this first round, surgeons were explicitly blinded to the identity of the models, to all model outputs and to the interim ratings provided by the other evaluators. After an independent review, all cases with at least one discrepant rating were re-examined in a dedicated consensus session. In this session, the three surgeons discussed the clinical scenario and their initial assessments and resolved disagreements by majority rule (two-out-of-three agreement). The final majority label was considered the reference standard for that case and used in all comparative analyses. The time required for expert adjudication was recorded with a stopwatch during the consensus process and subsequently summarised as the human latency benchmark.

2.4. Prompting, Inference and Logging

Five large language models were queried programmatically through their public APIs: GPT-5 (OpenAI; Chat Completions API with model = “gpt-5”), DeepSeek-Chat and DeepSeek-Reasoner (DeepSeek Inc., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China; chat-completions API with model = “deepseek-chat” or model = “deepseek-reasoner”) and Gemini-2.5-Flash and Gemini-2.5-Pro (Google; Generative Language API v1beta).

For context, the evaluated systems represent different design choices and intended uses. GPT-5 (“ChatGPT-5”, OpenAI) is a general-purpose frontier LLM accessible through a routed endpoint, which internally selects among multiple model variants and is optimised for broad-domain reasoning and conversational assistance rather than for pharmacology specifically. DeepSeek-Chat (DeepSeek Inc.) is a chat-optimised model designed for fast, conservative responses, whereas DeepSeek-Reasoner is a companion model that prioritises more elaborate stepwise reasoning at the expense of latency. Gemini-2.5-Flash and Gemini-2.5-Pro (Google) are multimodal generative models; the Flash variant is tuned for low-latency, high-throughput applications, while the Pro variant is positioned as a more capable general model for complex analytical tasks. None of these systems is explicitly fine-tuned on dental prescribing or oral-surgery DDIs, and none was provided with direct access to proprietary drug interaction databases (such as Lexicomp or Micromedex) during inference.

For DeepSeek and Gemini models, decoding parameters included an explicitly fixed temperature of 0.0, and other generation settings (e.g., top_p, token limits) were left at provider defaults to maximize determinism. For GPT-5, no generation parameters (temperature, top_p, max tokens, or reasoning effort) were overridden; the routed gpt-5 endpoint dynamically allocates fast versus extended reasoning internally. Each of the 500 simulated oral-surgery cases was submitted exactly once to each model under these fixed settings. This default-oriented configuration was adopted to mirror realistic clinical and educational use, in which users typically rely on vendor-recommended settings rather than extensive manual tuning, and to avoid introducing additional bias through model-specific parameter optimisation.

The prompt delivered to each model contained: (i) the standardized surgical scenario (mandibular third-molar surgery), (ii) the complete medication profile for that scenario, including chronic therapy and the perioperative prescription (drug, dose, route, frequency, duration) and (iii) renal/hepatic cautions when applicable. The instruction requested identification of clinically relevant drug–drug interactions and assignment of a single severity grade using a constrained Lexicomp-based scale {A, B, C, D, X}, where D/X indicates that clinical action is required. Model outputs were post-processed only by trimming whitespace and forcing uppercase. A response was considered valid if, after this preprocessing, it contained exactly one allowed severity code from {A, B, C, D, X} and no contradictory additional codes. Any reply that did not satisfy this criterion—for example, free-text narrative without a severity letter, multiple conflicting letters, or other unparseable formats—was flagged for manual adjudication and treated as missing in the quantitative analyses until resolved.

For every API call, latency was measured in real time using time.time() as the interval between request dispatch and receipt of the complete response. Brief intentional pauses between consecutive calls (e.g., one-second waits to respect rate limits) were not counted as latency. Latency values were recorded in seconds for all cases and summarised at the model level to characterise practical responsiveness in a near-real-time, chairside decision-support scenario.

All prompts, raw model responses, timestamps, assigned severity letters and measured latencies were logged and merged into a single case-level table together with the consensus severity label provided by the oral surgeon panel.

2.5. Knowledge Sources and Severity Framework

Drug–drug interaction severity in the reference standard followed the Lexicomp rating: A (no interaction), B (no action needed), C (monitor therapy), D (consider therapy modification) and X (avoid combination). For each simulated case, the final severity letter used as “ground truth” was assigned by the oral-surgeon panel during the consensus process described in Section 2.3. When additional information was needed, panel members could consult three drug interaction compendia (Lexicomp, Micromedex and Stockley’s Drug Interactions) as supporting knowledge sources [37,38].

When Micromedex Drug Interactions (Micromedex Solutions, Merative, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; version 2.0) or Stockley’s Drug Interactions, 12th edition (Pharmaceutical Press, London, UK) were consulted, a predefined mapping was used to relate their interaction categories to the Lexicomp® Drug Interactions database (Lexicomp, Wolters Kluwer Health, Hudson, OH, USA; version 9.3.0) scale. Interactions described as “contraindicated” or “avoid” were aligned to X when complete avoidance is recommended, or to D when modification of therapy is usually sufficient. “Major” interactions requiring a change in therapy were aligned to D, “moderate” interactions usually requiring closer monitoring and/or dose adjustment were aligned to C, and “minor” or “no clinically significant interaction” corresponded to B. Combinations for which no interaction was reported were classified as A.

If the compendia gave different assessments, a conservative rule was applied: whenever a trusted source suggested a more serious interaction (for example, D instead of C), the higher severity level was chosen. This approach makes the human reference standard more sensitive to potentially dangerous interactions, even at the cost of a more stringent benchmark for model specificity. These knowledge sources were used only to support the human reference standard and were not provided directly to the language models in the prompts.

2.6. Outcomes

The primary outcome was case-level accuracy, defined as the exact agreement between each model’s predicted severity grade (A–B–C–D–X) and the surgeon-panel consensus reference standard for the same simulated case.

Secondary outcomes described the closeness to the reference and the distribution of classification errors. Ordinal agreement was quantified using quadratic-weighted κ, while the ordinal error profile was expressed through the median absolute grade difference |prediction − reference|, the proportion of predictions within one grade of the reference (Acc@1), and the proportion differing by two or more grades.

A binary clinical endpoint was also evaluated by collapsing the ordinal categories into two groups: grades D/X were classified as “action required” and A–C as “no action.” For each model compared with the reference standard, the following 2 × 2 metrics were calculated: accuracy, sensitivity (recall), specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and two clinically oriented indicators—Safety-FN (false negatives among true D/X cases) and Overcall (false positives among true A–C cases).

Finally, process outcomes (latency) were measured as the per-case response time for each model and for the reference process, and summarized using the median, interquartile range, and 90th percentile to describe performance consistency and extreme delays.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed at the case level (N = 500). Model outputs and the surgeon-adjudicated reference standard were letter grades on an ordinal scale {A,B,C,D} (with occasional X). Text fields were trimmed and upper-cased prior to analysis. Letters were mapped to integer scores (A = 0, B = 1, C = 2, D = 3, X = 4) to enable ordinal computations; only available, non-missing pairs were used (no imputation).

2.7.1. Agreement Metrics

For each model, exact category agreement with the reference standard (proportion of identical letters) was computed with exact binomial 95% CIs. To quantify agreement on the ordinal scale, quadratically weighted agreement and common coefficients (Percent Agreement, Brennan–Prediger, Cohen/Conger’s κ, Scott/Fleiss’ π, Gwet’s AC and Krippendorff’s α) were estimated with standard errors and 95% CIs (Stata kappaetc, quadratic weights based on squared score differences). Quadratic-weighted agreement gives greater penalties to larger disagreements (e.g., D vs. A vs. D vs. C), and κ-type coefficients adjust the observed agreement for the level of agreement expected by chance. These measures summarise how closely each model reproduces the human ordinal classification.

2.7.2. Error Analysis and Ordinal Distance

Using the ordinal scores, the per-model absolute distance |prediction − reference| was summarized by median and IQR. Two ancillary proportions were also reported: Accuracy-within-1 (Acc@1 = P[distance ≤ 1]) and Off-by-2+ (P[distance ≥ 2]), each with exact binomial 95% CIs. These quantities describe not only whether predictions are correct, but also how far incorrect predictions tend to fall from the reference severity grade.

2.7.3. Statistical Tests for Categorial Outcomes

Pairwise differences in exact agreement between models were tested within-case using the paired exact test for proportions (two-sided exact McNemar). For each comparison, discordant counts b (A correct/B incorrect) and c (A incorrect/B correct), the risk-difference in percentage points (Δpp = 100·[p_A − p_B]), the two-sided exact p-value (from the binomial tail on n = b + c) and a mid-p sensitivity analysis were obtained. Multiplicity across the 10 pairwise tests was controlled using Holm’s step-down adjustment; adjusted p-values are presented alongside raw values where applicable.

2.7.4. Binary Clinical Endpoint and Diagnostic-Type Metrics

The ordinal scale was dichotomized a priori as “action required” = {D,X} versus “no action” = {A,B,C}. For each model versus the reference standard, a 2 × 2 confusion matrix was formed and Accuracy, Sensitivity (Recall), Specificity, PPV, NPV, Safety-FN (FN/(TP + FN) = 1 − Sensitivity) and Overcall (FP/(TN + FP) = 1 − Specificity) were derived, with exact (Clopper–Pearson) 95% CIs for proportions. These diagnostic-type metrics quantify the ability of each model to detect clinically relevant interactions (D/X) while controlling the rate of false alarms on non-actionable cases (A–C).

2.7.5. Latency Analysis

Per-case response times (seconds) were compared within subjects across the six sources (five models plus the reference-process timing) using the Friedman test. Pairwise post hoc contrasts used Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Holm correction; for key contrasts, the Hodges–Lehmann median paired difference with 95% CIs was reported.

All tests were two-sided with α = 0.05 after multiplicity control. Analyses were conducted in Stata 19 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA); agreement metrics used the user-written kappaetc package and built-in exact binomial functions.

3. Results

3.1. Sample and Case Characteristics

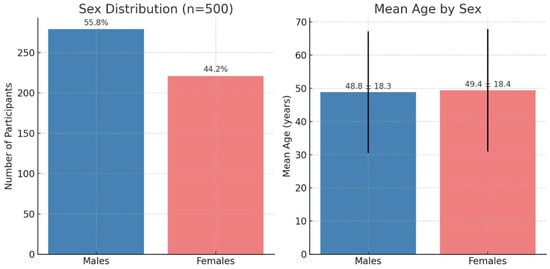

A total of 500 cases were included. The sex distribution was 279 males (55.8%) and 221 females (44.2%). The overall mean age was 49.1 years (SD 18.3); by sex, mean age was 48.8 ± 18.3 years in males (n = 279) and 49.4 ± 18.4 years in females (n = 221). The observed age range was 18–80 years in both groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population (n = 500). The left panel shows the sex distribution. The right panel shows the mean age by sex; bars represent mean values and the vertical lines indicate standard deviation.

3.2. Agreement with the Surgeon-Team Reference

Across 500 cases, exact letter agreement with the reference standard adjudicated by the surgeon team (exact binomial 95% CI) was: DeepSeek-Chat 50.6% (46.13–55.07), DeepSeek-Reasoner 45.6% (41.17–50.08), ChatGPT-5 41.8% (37.44–46.26), Gemini-Flash 38.4% (34.12–42.82) and Gemini-Pro 33.8% (29.66–38.13) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Exact letter agreement with the surgeon-panel reference standard. Exact 95% binomial (Clopper–Pearson) confidence intervals; Percent = 100 × Proportion.

Considering ordinal proximity to the reference, the highest quadratically weighted observed agreement (“weighted percent agreement”) was obtained by DeepSeek-Chat (0.933) and GPT-5 (“ChatGPT-5”) (0.929), followed by DeepSeek-Reasoner (0.846), Gemini-Flash (0.830), and Gemini-Pro (0.800).

Chance-corrected quadratic-weighted κ and Gwet’s AC indicated only moderate agreement overall. In these chance-corrected metrics, ChatGPT-5 and DeepSeek-Reasoner achieved the highest κ values, while DeepSeek-Chat showed the highest Gwet’s AC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ordinal agreement on severity with quadratic weights (kappaetc). Weighted percent agreement, quadratic-weighted κ and Gwet’s AC are shown with 95% confidence intervals.

Analysis of the absolute severity error confirmed that most disagreements were “near misses”. The median absolute error was 0 for DeepSeek-Chat and 1 for the remaining models, with an interquartile range of [0, 1] for all.

The Acc@1 metric (≤1-grade deviation from the reference) ranged from 95.4% (Gemini-Pro) to 98.2% (ChatGPT-5), while Off-by-2+ (≥2-grade deviation) ranged from 1.8% (ChatGPT-5) to 4.6% (Gemini-Pro) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distance-based performance summaries on the ordered severity scale. Median absolute severity error, proportion of predictions within one grade of the reference (Acc@1) and proportion differing by two or more grades (Off-by-2+) are reported for N = 500 cases.

3.3. Head-to-Head Comparisons of Exact Correctness

Pairwise differences in exact correctness showed significant advantages for: DeepSeek-Chat over ChatGPT-5 by 8.8 percentage points (pp), p = 0.008; ChatGPT-5 over Gemini-Pro by 8.0 pp, p = 0.00052; DeepSeek-Reasoner over Gemini-Flash by 7.2 pp, p = 0.004; DeepSeek-Reasoner over Gemini-Pro by 11.8 pp, p < 0.0001; DeepSeek-Chat over Gemini-Flash by 12.2 pp, p = 0.001; and DeepSeek-Chat over Gemini-Pro by 16.8 pp, p < 0.0001. Non-significant contrasts were: ChatGPT-5 vs. DeepSeek-Reasoner (−3.8 pp; p = 0.145), ChatGPT-5 vs. Gemini-Flash (+3.4 pp; p = 0.201) and DeepSeek-Reasoner vs. DeepSeek-Chat (−5.0 pp; p = 0.159) (mid-p values were consistent) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pairwise comparison of exact-letter correctness (two-sided exact McNemar test). Definitions: A correct & B incorrect; A incorrect & B correct; ; exact (pp) ; p = two-sided exact; mid-p = two-sided mid-p.

3.4. Clinical Action Endpoint

Considering the binary endpoint “action required” (D or X) versus “no action” (A–C), all models showed very high negative predictive values (>91%) but low positive predictive values (16–20%), reflecting the relatively low prevalence of D/X cases in the dataset (Table 5). ChatGPT-5 and Gemini-2.5-Flash achieved very high sensitivity (98% and 94%, respectively) with moderate specificity (about 56%), resulting in low Safety-FN rates (2–6%) but Overcall rates around 43–44%. DeepSeek-Reasoner showed a slightly more conservative profile, with sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 55%, and an intermediate Safety-FN of 12%.

Table 5.

Binary clinical endpoint, with category D/X coded as the positive class and categories A–C coded as the negative class. Abbreviations: TP = true positives; TN = true negatives; FP = false positives; FN = false negatives; PPV = positive predictive value; NPV = negative predictive value; Safety FN = FN/(TP + FN); Overcall = FP/(TN + FP).

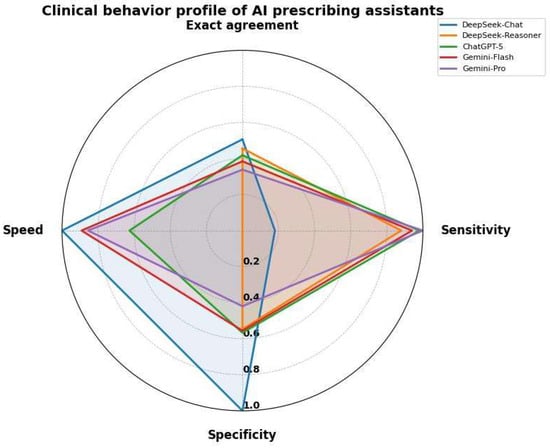

DeepSeek-Chat adopted an extremely conservative behaviour, with 100% specificity and 0% Overcall, but at the cost of detecting only 18% of clinically actionable interactions (Safety-FN 82%). At the opposite extreme, Gemini-2.5-Pro maximised sensitivity (100%, Safety-FN 0%) while showing the lowest specificity (42%) and the highest Overcall (58%). Overall accuracy was therefore highest for DeepSeek-Chat (91.8%), driven by the large proportion of non-actionable cases, and lowest for Gemini-2.5-Pro (47.8%) (Table 5, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical behavior profile of AI prescribing assistants. The radar chart compares five AI models across speed, sensitivity, specificity and exact agreement.

To characterise global discriminative ability beyond the single operating point D/X vs. A–C, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated by treating the ordinal severity predictions as a numerical risk score. The resulting areas under the curve (AUCs) ranged from 0.698 (DeepSeek-Chat) to 0.776 (ChatGPT-5), with intermediate values for Gemini-2.5-Flash (0.749), DeepSeek-Reasoner (0.716) and Gemini-2.5-Pro (0.710), indicating only moderate discrimination overall. The full ROC curves are reported in Supplementary File S1.

3.5. Latency

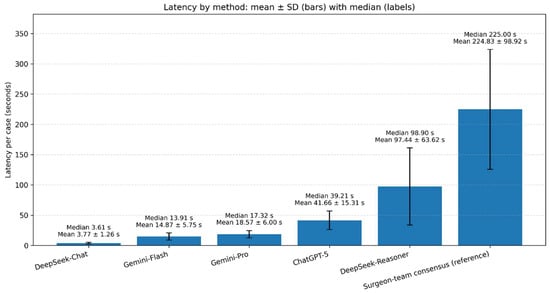

Per-case latency (seconds) medians (mean, SD) were: DeepSeek-Chat 3.61 (3.77, 1.26), Gemini-Flash 13.91 (14.87, 5.75), Gemini-Pro 17.32 (18.57, 6.00), ChatGPT-5 39.21 (41.66, 15.31), DeepSeek-Reasoner 98.90 (97.44, 63.62), reference standard 225.00 (224.83, 98.92) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Per-case latency by method. Vertical bars depict mean latency (seconds) with ±SD error bars; labels above bars report the median and mean ± SD. Methods are ordered from fastest to slowest by median.

A within-case rank-based analysis found all 15 pairwise contrasts significant after multiplicity correction (adjusted p < 0.001 for every pair).

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

This study is, to our knowledge, the first to systematically compare multiple large language models (LLMs) with experienced oral surgeons in identifying clinically relevant drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in standardized oral surgery scenarios. Previous investigations have already highlighted the growing importance of drug interactions in dental settings, as discussed by Colibășanu et al. (2025) [1] and Abbaszadeh et al. (2022) [2], but none have directly evaluated AI systems against human experts.

Among the evaluated systems, DeepSeek-Chat achieved the highest exact agreement with the surgeon reference standard (50.6%) and showed excellent ordinal consistency (Weighted percent agreement ≈ 0.93). ChatGPT-5, although less precise (41.8% agreement), showed the best sensitivity (98.0%) in detecting clinically actionable DDIs (Figure 3).

This trade-off between sensitivity and specificity mirrors what Wang et al. (2025) [29] and Zitu et al. (2025) [30] observed in LLM performance across clinical pharmacology tasks. Highly sensitive systems such as ChatGPT-5 and Gemini may increase false-positive alerts, potentially leading to alert fatigue and workflow disruption, a concern also noted in pharmacovigilance studies by Sicard et al. (2025) [32]. Conversely, precision-oriented models like DeepSeek-Chat may under-detect relevant DDIs, risking missed adverse reactions, consistent with observations from Huang et al. (2025) [35]. In this context, the observed quadratic-weighted κ and Gwet’s AC values indicate only moderate agreement at best between the models and the human consensus, meaning that, although performance is clearly better than chance, it remains insufficient to serve as a stand-alone reference without additional safeguards. Finding the optimal balance between these two extremes remains, therefore, not merely a technical issue but one with direct implications for patient safety and professional usability.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

Our findings are broadly consistent with previous research investigating the reliability of large language models (LLMs) for pharmacovigilance and drug–drug interaction (DDI) prediction. Earlier evaluations reported that general-purpose LLMs such as ChatGPT and Claude achieved very high sensitivity (up to 95–99%) but poor specificity due to hallucinated or duplicated DDIs, as shown by Sicard et al. (2025) [32] and Al-Ashwal et al. (2023) [33]. Similarly, Krishnan et al. (2024) [31] observed that ChatGPT models could accurately detect most clinically relevant interactions but tended to overestimate their severity, leading to inflated risk profiles. In the present dataset, ChatGPT-5 showed a comparable pattern, with sensitivity close to 98% for D/X interactions but specificity around 57% and Overcall above 40%, suggesting that high recall is again obtained at the cost of a substantial number of false-positive alerts.

ChatGPT-5 may have shown an improvement over previous versions, reaching a level of performance comparable to domain-oriented reasoning models. This trend supports the conclusion of Wang et al. (2025) [29], who reported that progressive LLM evolution is narrowing the gap between general and specialised architectures.

Likewise, Ong et al. (2025) [39], in a scoping review of generative AI for pharmacovigilance, identified DDI detection as one of the most promising yet under-validated applications—a limitation our study begins to address within the oral-surgery context. As shown by Sicard et al. (2025) [32], general-purpose LLMs reached very high detection rates of DDIs but remained unable to reliably exclude non-interactions; the moderate AUC values and relatively low positive predictive values (16–20%) observed here align with that limitation, indicating that most alerts generated by even the best-performing models do not correspond to truly actionable DDIs.

In accordance with Ong et al. (2025) [39], who identified generative AI’s three key applications in drug safety, we extend these insights to the domain of oral surgery. Our findings also reflect the caution expressed by Hakim et al. (2025) [40] regarding LLMs in safety-critical settings with false positives and hallucinations requiring robust oversight. Moreover, Huang et al. (2025) [35] emphasised that AI-driven DDI research is making progress but still lacks domain-specific tuning and explainability, which our work begins to address. At the same time, our observation of false-positive inflation aligns with the warning issued by Hakim et al. (2025) [40], who emphasized the need for robust guardrails and continuous monitoring when LLMs are deployed in safety-critical medical domains such as drug safety. Conversely, the perfect specificity but low sensitivity of DeepSeek-Chat (18%) reflects an opposite safety profile with fewer false alarms but a greater risk of missed interactions. This polarity mirrors the challenge outlined by Huang et al. (2025) [35], who noted that AI-powered DDI prediction must balance precision with clinical explainability through domain-specific calibration. Overall, these results reinforce a central message emerging across the literature: while LLMs show great potential for supporting pharmacological decision-making, their deployment in dentistry requires validation, transparency and continuous oversight to ensure true clinical reliability.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of the present study lies in its rigorous and reproducible design, which incorporated deterministic case generation, blinded expert adjudication and standardized severity grading using the Lexicomp framework, an approach consistent with that used by Hughes et al. (2024) [6] in pharmacological safety research. The inclusion of five distinct LLM architectures (general-purpose and pharmacologically oriented) also provides a comprehensive view rarely explored in dental informatics, complementing the multidomain analyses discussed by Schwendicke et al. (2020) [27] and Sitaras et al. (2025) [28]. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, as in similar simulation-based studies (Zitu et al. 2025 [30]), the use of standardized scenarios ensured reproducibility but may not capture the variability of real-world prescribing. Second, the models were tested with single prompts and no iterative refinement; interactive prompting could improve reasoning accuracy, as suggested by Radha Krishnan et al. (2024) [31], so the present results should be interpreted as a conservative estimate of best-case model performance.

Third, the lack of extreme severity categories (A or X) may have reduced sensitivity to rare but critical DDIs. Additionally, a fundamental limitation of current LLMs lies in their black-box nature. The reasoning process leading to a given output remains largely opaque to the clinician, who cannot easily verify how the model derives its conclusions. This issue is particularly evident with ChatGPT-5, which automatically selects the most appropriate internal version or reasoning mode depending on the input prompt, making it unclear which model variant is being used in each query. Such opacity may hinder clinical trust and complicate validation, especially in high-stakes decision-support contexts. Finally, as model performance evolves rapidly with new training data, periodic reevaluation remains essential.

Finally, formal pre-consensus inter-rater agreement statistics were not calculated, so the reliability of individual surgeon ratings cannot be quantified separately from the consensus; however, the use of a blinded, multi-expert panel and a structured consensus procedure supports the robustness of the final reference labels.

4.4. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

From a practical perspective, AI-driven systems can significantly reduce clinicians’ cognitive burden by screening for DDIs in seconds (DeepSeek-Chat, for instance, processed cases in a median of 3.6 s versus 225 s for human adjudication). Similar efficiency benefits have been documented in applied dental AI frameworks by Sitaras et al. (2025) [28]. Integrating such tools into chairside decision-support systems could enhance patient safety, particularly for polypharmacy or medically complex patients. However, these tools should be embedded within workflows that explicitly preserve human control, with oral surgeons and prescribing physicians reviewing alerts and retaining final responsibility for treatment decisions. This approach is in line with the collaborative models proposed by Laddha (2025) [24] and Johnson et al. (2018) [23]. In addition, AI-based DDI screeners should be implemented in accordance with existing regulatory frameworks for clinical decision-support software, with clearly defined intended use, documented performance characteristics, ongoing monitoring and explicit human override, so that licensed clinicians retain ultimate responsibility for prescribing decisions.

Future work should focus on domain-specific fine-tuning of LLMs using curated pharmacological datasets and structured interaction ontologies to optimize both sensitivity and specificity, as proposed by Huang et al. (2025) [35]. Moreover, hybrid frameworks combining LLMs with established drug databases (e.g., Lexicomp, Micromedex) or with EHR-linked decision-support systems could produce safer and more interpretable tools, a direction already explored in broader medical AI research by Wang et al. (2025) [29].

Additional research should also explore explicit strategies for threshold calibration and risk stratification (for example, stricter alert thresholds for high-risk drug classes or vulnerable patient groups), as well as mechanisms for capturing clinician feedback on false-positive and false-negative alerts. Such measures may progressively reduce error rates and improve the practical usefulness of AI-assisted DDI screening in oral-surgery practice. In the context of oral surgery, such integration could bridge the existing divide between dental and medical pharmacology, fostering interprofessional collaboration and minimizing iatrogenic risks, as highlighted by Laddha (2025) [24] and Choi et al. (2017) [25].

5. Conclusions

Large language models (LLMs) can assist clinicians in identifying drug–drug interactions (DDIs) in oral surgery by enabling rapid, standardized screening and reducing cognitive workload, but they should be used strictly as auxiliary tools rather than replacements for clinical judgement. In this comparative evaluation, DeepSeek-Chat achieved the highest concordance with the surgeon reference standard and offered a more conservative profile with fewer false alarms, whereas ChatGPT-5 showed markedly higher sensitivity at the cost of more frequent alerts, underscoring complementary strengths that may be more or less acceptable depending on the clinical tolerance for missed events versus overcall. The observed sensitivity–specificity trade-off confirms that continuous human oversight and close collaboration between AI systems and dental–medical professionals are essential for safe deployment in practice. Future work should focus on real-world clinical evaluation, domain-specific calibration and improved explainability of LLM outputs, so that clinicians can better understand, trust and safely integrate these tools into everyday prescribing decisions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152312851/s1, File S1: ROC analysis for the binary clinical endpoint.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T. and C.B.; methodology, S.T. and G.P.; software, M.S.; validation, G.P., P.F. and C.B.; formal analysis, S.T.; investigation, S.T. and M.S.; resources, P.F.; data curation, M.S. and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.T. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, S.T. and M.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, P.F., R.P. and G.P.; project administration, P.F. and R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DDIs | Drug–Drug Interactions |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| LLMs | Large Language Models |

| NSAIDs | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| SSRIs | Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors |

| MRONJ | Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| STARD | Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies |

References

- Colibășanu, D.; Ardelean, S.M.; Goldiș, F.D.; Drăgoi, M.M.; Vasii, S.O.; Maksimović, T.; Colibășanu, Ș.; Șoica, C.; Udrescu, L. Unveiling Drug-Drug Interactions in Dental Patients: A Retrospective Real-World Study. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abbaszadeh, E.; Ganjalikhan Hakemi, N.; Rad, M.; Torabi, M. Drug-Drug Interactions in Elderly Adults in Dentistry Care: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Dent. 2022, 23, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fujita, K.; Masnoon, N.; Mach, J.; O’Donnell, L.K.; Hilmer, S.N. Polypharmacy and precision medicine. Camb. Prism. Precis. Med. 2023, 1, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morgado-Sevillano, D.; Rodríguez-Molinero, J.; García-Bravo, C.; Peña-Cardelles, J.F.; Ruiz-Roca, J.A.; García-Guerrero, I.; Gómez-de Diego, R. Oral surgery considerations in patients at high-risk of complications related to drug intake: A systematic review. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 1503–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dunbar, D.; Ouanounou, A. An update on drug interactions involving anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications in oral and maxillofacial medicine: A narrative review. Front. Oral. Maxillofac. Med. 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.E.; Bennett, K.E.; Cahir, C. Drug-Drug Interactions and Their Association with Adverse Health Outcomes in the Older Community-Dwelling Population: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Drug Investig. 2024, 44, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dou, K.; Shi, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhao, Z. Risk of bleeding with dentoalveolar surgery in patients taking direct oral anticoagulants or vitamin K antagonists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2025, 61, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Holbrook, A.M.; Pereira, J.A.; Labiris, R.; McDonald, H.; Douketis, J.D.; Crowther, M.; Wells, P.S. Systematic overview of warfarin and its drug and food interactions. Arch. Intern. Med. 2005, 165, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghbin, H.; Zakirkhodjaev, N.; Husain, F.F.; Lee-Smith, W.; Aziz, M. Risk of Gastrointestinal Bleeding with Concurrent Use of NSAID and SSRI: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 1975–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anglin, R.; Anglin, R.; Yuan, Y.; Moayyedi, P.; Tse, F.; Armstrong, D.; Leontiadis, G.I. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with or without concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Calip, G.S.; Rowan, S.; McGregor, J.C.; Perez, R.I.; Evans, C.T.; Gellad, W.F.; Suda, K.J. Potentially Inappropriate Medication Combination with Opioids among Older Dental Patients: A Retrospective Review of Insurance Claims Data. Pharmacotherapy 2020, 40, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baldo, B.A.; Rose, M.A. The anaesthetist, opioid analgesic drugs, and serotonin toxicity: A mechanistic and clinical review. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 124, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, M.; Schindler, C. Clinically and pharmacologically relevant interactions of antidiabetic drugs. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 7, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Spanakis, M.; Alon-Ellenbogen, D.; Ioannou, P.; Spernovasilis, N. Antibiotics and Lipid-Modifying Agents: Potential Drug-Drug Interactions and Their Clinical Implications. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johannessen, S.I.; Landmark, C.J. Antiepileptic drug interactions—Principles and clinical implications. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2010, 8, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kutt, H. Interactions between anticonvulsants and other commonly prescribed drugs. Epilepsia 1984, 25, S118–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, H. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: An update. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 13, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sacco, R.; Woolley, J.; Yates, J.; Calasans-Maia, M.D.; Akintola, O.; Patel, V. The role of antiresorptive drugs and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in nononcologic immunosuppressed patients: A systematic review. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2021, 26, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zheng, Z.; Johansson, H.; Harvey, N.C.; Lorentzon, M.; Vandenput, L.; Liu, E.; Kanis, J.A.; McCloskey, E.V. Potential Adverse Effect of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) on Bisphosphonate Efficacy: An Exploratory Post Hoc Analysis From a Randomized Controlled Trial of Clodronate. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2022, 37, 1117–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coropciuc, R.; Coopman, R.; Garip, M.; Gielen, E.; Politis, C.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Beuselinck, B. Risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after dental extractions in patients receiving antiresorptive agents—A retrospective study of 240 patients. Bone 2023, 170, 116722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hersh, E.V.; Moore, P.A. Drug interactions in dentistry: The importance of knowing your CYPs. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004, 135, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, P.A.; Gage, T.W.; Hersh, E.V.; Yagiela, J.A.; Haas, D.A. Adverse drug interactions in dental practice. Professional and educational implications. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1999, 130, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.L.; Fuji, K.T.; Franco, J.V.; Castillo, S.; O’Brien, K.; Begley, K.J. A Pharmacist’s Role in a Dental Clinic: Establishing a Collaborative and Interprofessional Education Site. Innov. Pharm. 2018, 9, v9i4.1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Laddha, R. Bridging the Gap: The Critical Role of Collaboration Between Dentistry and Pharmacy. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2025, 17, S1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Choi, H.J.; Stewart, A.L.; Tu, C. Medication discrepancies in the dental record and impact of pharmacist-led intervention. Int. Dent. J. 2017, 67, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samaranayake, L.; Tuygunov, N.; Schwendicke, F.; Osathanon, T.; Khurshid, Z.; Boymuradov, S.A.; Cahyanto, A. The Transformative Role of Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Overview. Part 1: Fundamentals of AI, and its Contemporary Applications in Dentistry. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwendicke, F.; Samek, W.; Krois, J. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: Chances and Challenges. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sitaras, S.; Tsolakis, I.A.; Gelsini, M.; Tsolakis, A.I.; Schwendicke, F.; Wolf, T.G.; Perlea, P. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Dental Medicine: A Critical Review. Int. Dent. J. 2025, 75, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Zhuang, B.; Huang, S.; Fang, M.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Gong, S. Accuracy of Large Language Models When Answering Clinical Research Questions: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e64486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zitu, M.M.; Owen, D.; Manne, A.; Wei, P.; Li, L. Large Language Models for Adverse Drug Events: A Clinical Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Radha Krishnan, R.P.; Hung, E.H.; Ashford, M.; Edillo, C.E.; Gardner, C.; Hatrick, H.B.; Kim, B.; Lai, A.W.Y.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.X.; et al. Evaluating the capability of ChatGPT in predicting drug-drug interactions: Real-world evidence using hospitalized patient data. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 3361–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sicard, J.; Montastruc, F.; Achalme, C.; Jonville-Bera, A.P.; Songue, P.; Babin, M.; Soeiro, T.; Schiro, P.; de Canecaude, C.; Barus, R. Can large language models detect drug-drug interactions leading to adverse drug reactions? Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Al-Ashwal, F.Y.; Zawiah, M.; Gharaibeh, L.; Abu-Farha, R.; Bitar, A.N. Evaluating the Sensitivity, Specificity, and Accuracy of ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Bing AI, and Bard Against Conventional Drug-Drug Interactions Clinical Tools. Drug Healthc. Patient Saf. 2023, 15, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.M. Capacity of ChatGPT, Deepseek, and Gemini in predicting major potential drug interactions in adults within the Intensive Care Unit. J. Hosp. Pharm. Health Serv. 2025, 16, e1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Zhang, S. Advancing drug-drug interactions research: Integrating AI-powered prediction, vulnerable populations, and regulatory insights. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1618701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.; Lijmer, J.G.; Moher, D.; Rennie, D.; de Vet, H.C.; et al. STARD2015: An updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015, 351, h5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abbas, A.; Al-Shaibi, S.; Sankaralingam, S.; Awaisu, A.; Kattezhathu, V.S.; Wongwiwatthananukit, S.; Owusu, Y.B. Determination of potential drug-drug interactions in prescription orders dispensed in a community pharmacy setting using Micromedex® and Lexicomp®: A retrospective observational study. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.I.; Beckett, R.D. Evaluation of resources for analyzing drug interactions. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ong, J.C.L.; Chen, M.H.; Ng, N.; Elangovan, K.; Tan, N.Y.T.; Jin, L.; Xie, Q.; Ting, D.S.W.; Rodriguez-Monguio, R.; Bates, D.W.; et al. A scoping review on generative AI and large language models in mitigating medication related harm. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hakim, J.B.; Painter, J.L.; Ramcharran, D.; Kara, V.; Powell, G.; Sobczak, P.; Sato, C.; Bate, A.; Beam, A. The need for guardrails with large language models in pharmacovigilance and other medical safety critical settings. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).