Abstract

Mesoporous silica and its derivatives might enable applications ranging from biomedicine to petrochemical processing. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD) and N2 adsorption–desorption measurements are usually used to characterize the ordered porous system. However, none of these methods convey the full surface information. In this work, a low-voltage scanning electron microscope (LVSEM) with beam deceleration technology was employed to image detailed surface structures of ~2 nm pore size silica (MCM-41), SBA-15, KIT-6, and mesoporous silica nanospheres (MSNSs). The prospects for the development of this application of ultra-high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM) are discussed in the characterization of the ordered porous materials. We demonstrate that the complete dimension range of the mesoscopic surface structure (2–50 nm) could be resolved by current low-voltage SEM technology.

1. Introduction

The invention of Mobil Composition of Matter No. 41 (MCM-41) [1] triggered an explosion of research into mesoporous materials, which have been intensively studied for applications as diverse as catalysis [2,3], molecular adsorption [4,5], drug delivery [6,7], molecular separation using membranes [8,9], energy [10] and templates for synthesis of advanced nanomaterials [11,12]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was broadly used to characterize these ordered porous systems [13,14,15]. Different from TEM and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) which have weak surface sensitivity, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) could reveal detailed information on more microscopic surface structures [16]. However, the practical spatial resolution of SEM was still limited by inclusion of delocalized secondary electron (SE) components [17], the charge effect and the instrument itself [18]. Low voltage coupled with an in-lens detector could control how the signals are dominated by the SE1 component that is emitted from a small escape depth under the specimen surface after direct excitation by the incident electron beam and could ease the charging on non-conducting materials. Terasaki et al. [19] first reported low-voltage scanning electron microscopy (LVSEM) direct observation of the 3D mesoporous structure of Santa Barbara No. 15 (SBA-15) with ~7.5 nm pore diameters and ~2.5 nm thickness of pore wall at 2 kV [20,21,22,23]. Bao et al. [24] imaged a series of SBA-15 materials with finely controlled pore length by using a classic cold field emission SEM instrument (Hitachi S4800, Hitachinaka, Japan) at 1.5 kV. However, the imaging performance of LVSEM in areas like resolution and contrast could be improved by using beam deceleration technology [16], which may further reduce interaction volume of incident electrons and specimens. Jóźwik et al. used an ultra-low-voltage (0.5 keV) SEM to directly visualize the high resistance region caused by ion irradiation in GaN through the damage-induced voltage-change imaging contrast mechanism [25]. Zhang et al. systematically studied the LVSEM imaging mechanism of high-density carbon nanotube arrays on SiO2/Si substrates, and developed an effective method to separate the three contrasts of topology, material and charge to accurately evaluate the array density and polymer residue distribution [26]. Kitta successfully used ultra-low voltage (0.5 keV) SEM to clearly distinguish the distribution of lithiated/delithiated particles in Li-ion battery electrodes, revealing the decisive influence of particle surface conductivity on secondary electron yield [27].

Another way to improve the spatial resolution of SEM was by observing the transmission samples at relatively high voltage like 10 kV, 30 kV or even 200 kV [28,29]. With this method, smaller lateral spot size could be controlled easily and most incident electrons could pass directly through the sample, which might reduce lateral delocalized secondary electron (SE2 and SE3) components, and then the percentage of the SE1 component could be increased. Tüysüz et al. [28] first resolved the high-resolution SEM images of ~2 nm pore size MCM-41 at 10 kV without any beam deceleration. However, the charge and beam damage caused by the high landing energy could not be overlooked [30].

Herein, we report that we can directly image the distinct surface structures of 7 nm pore diameter SBA-15, and even ~2.0 nm pore diameter MCM-41 mesoporous silica by using negative specimen stage bias beam-deceleration technology. A 500 eV landing energy LVSEM and a 200 kV SEM were used to produce a direct image of ~2.0 nm pore diameter silica. High quality SEM images could be provided by these means. Imaging capability mechanisms for the results in different conditions are discussed by comparing them with each other using Monte Carlo simulation.

All these results will allow for a better understanding of the accessibility of the porous systems of ordered mesoporous materials. The two methods, especially low-voltage low-probe-current SEM with beam deceleration technology, could be extended to other mesoporous materials like beam-sensitive mesoporous MOF or COF [31], mesoporous carbon materials, or material systems with particles smaller than 5 nm. With the beam deceleration technology, the generated signal electrons were focused and accelerated towards the newly designed electron detectors, which may have enhanced the S/N rate of the image. Meanwhile, the lower landing energy of the incident electron beam may have further released the charging effect of non-conductive samples. These results also demonstrate that the complete dimension range of mesoscopic surface structures (2–50 nm) could be resolved by current LVSEM technology.

2. Result and Discussion

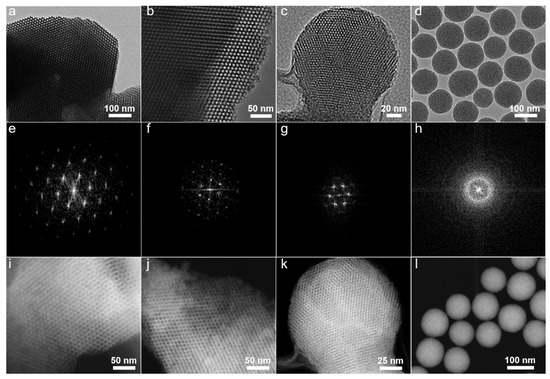

According to literature procedures, ~7 nm pore diameter SBA-15 [19], ~6 nm pore diameter KIT-6 [28], ~3 nm pore diameter mesoporous silica nanospheres (MSNSs) [32] and ~2 nm pore diameter MCM-41 mesoporous silica [28] were prepared. All samples were characterized with small-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD, Figure S1a), N2-sorption (Figure S1b,c) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM). Properties obtained from small-angle XRD and N2 adsorption–desorption measurement are summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 shows HRTEM images of as-prepared SBA-15, KIT-6, MCM-41 and MSNSs. TEM images (Figure 1a–c) and corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) patterns (Figure 1e–g) reveal the hexagonally ordered mesoporous structure of SBA-15, KIT-6 and MCM-41. The image analysis gives the SBA-15 pore diameters as ~7.09 nm with wall thickness ~3.12 nm, KIT-6 pore diameters as ~6.87 nm and wall thickness ~2.21nm, and MCM-41 pore diameters as ~2.00 nm and wall thickness ~1.73 nm. Figure 1d,h suggest the as-prepared MSNS pore system did not show spatial translation symmetry.

Table 1.

Texture parameters of SBA-15, KIT-6, MSNSs and MCM-41 by BET and XRD methods.

Figure 1.

TEM characterization of as-prepared mesoporous silica. (a–d) are TEM images of SBA-15, KIT-6, MCM-41 and MSNSs. (e–h) Corresponding FFT patterns. (i–l) HAADF-STEM images of SBA-15, KIT-6, MCM-41 and MSNSs.

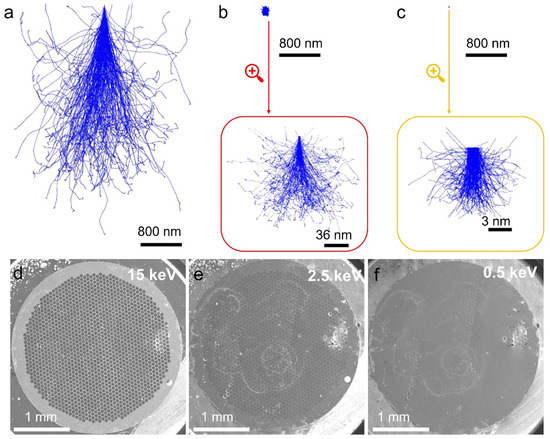

Before LVSEM characterization, the dependence of surface details on accelerating voltage was explored by Monte Carlo simulations and a simple control experiment was conducted (Figure 2). Figure 2a shows simulations of 2000 electrons with 15 keV kinetic energy that are vertically incident to carbon (spot size = 1 nm). The interaction depth is about 2 μm, so the SEM image of the TEM copper grids only show the copper grids without carbon film covering (Figure 2d). But when the accelerating voltage decreased to 2.5 kV, the interaction depth reduced to about 85 nm (Figure 2b), and translucent carbon film could be resolved on the copper grids (Figure 2e). With further decrease in the accelerating voltage to 500 V, the interaction depth reduced to about 6 nm (Figure 2c), and opaque carbon film was found to be covering the copper grids (Figure 2f). These results suggest that too high an accelerating voltage can result in deeper interaction depth in samples which might lead to missing the surface details of SEM images.

Figure 2.

Dependence of surface details on accelerating voltage. (a–c) Monte Carlo simulations of 2000 electrons with 15 keV, 2.5 keV and 500 eV kinetic energy are vertically incident to carbon. (d–f) SEM images of a TEM copper grids with accelerating voltage of 15 kV, 2.5 kV and 500 V.

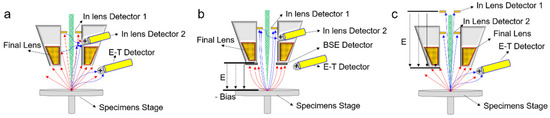

However, low-voltage high-resolution SEM technology could be divided into direct low voltage (Figure 3a), stage-bias beam deceleration (Figure 3b) and in-column beam deceleration (Figure 3c). To present the basic principles intuitively, Figure 3 shows the schematic of the three kinds of low-voltage technologies, including the objective lens systems, the detector systems, and the incident electron beam and signal electron trajectories. By comparing the signal electron trajectories, the collection efficiencies of different detectors and deceleration mode are clearly illustrated. Firstly, by directly decreasing the accelerating voltage to 500 V~1 kV, both the in-lens detector and the Everhart–Thornley (E–T) detector could collect SE images of samples by adding positive bias on the surface of these detectors. We succeeded in obtaining surface details of SBA-15 (Figure S2) with the E–T detector at 1 kV, which had been very rare in previous research. However, the image quality was unsatisfactory because the E–T detector images were enriched with SE2 and SE3 signals [17]. The in-lens detector images possessed more surface details, even at 500 V. Without any beam deceleration, we could image the parallel channels on the surface of mesoporous SBA-15 (Figure S3); the image quality is comparable to the literature [20,33,34,35,36,37]. Beam deceleration with negative stage bias could lower the interaction volume of electrons in samples, release the charge effect, accelerate the low-energy SE1 to in-lens detectors and change the low-angle backscattered electron (BSE) direction of motion to a higher angle (Figure 3b). Hence, we obtained decent SBA-15 images using a BSE detector with a landing energy of only 500 eV (Figure S4a). Even so, the BSE signals were still not an ultra-high-resolution method for smaller details compared to SE1. Considering that the low-energy SE1 are accelerated by the retarding field, a concentric annular in-lens detector (Figure 3b, in-lens detector 1) might receive more electrons than a side-position in-lens detector (Figure 3b, in-lens detector 2). So, the S/N rate of the Figure S4b side position in-lens detector image is not very high. It is also possible to improve the concentric annular in-lens detector images by increasing the stage bias from 2 to 5 kV [38]. Compared to Figure S5b, the S/N rate is improved and even the inter-channel micropores and plugs within channels can be observed in Figure S5a. Nevertheless, the weaknesses of this technology is that sharp surface samples might result in point discharge and small depth of field due to small interaction volume, which might cause difficulties in imaging bulk KIT-6 (Figure S6). Another low-voltage technology is in-column beam deceleration [39]. If the surface of samples is very close to the bottom of final lens (working distance, under 1 mm), the excited SE1 can be easily sucked into the column and accelerated by the in-column retarding field (Figure 3c). In this case, concentric annular in-lens detectors can ensure a good S/N rate even at very low probe-current conditions. The weakness of this technology is that very short working distances need a smooth sample surface.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the three kinds of low-voltage technologies. (a) Direct low voltage, (b) stage-bias beam deceleration (A reverse electric field is applied between the specimens stage and the pole piece), (c) in-column beam deceleration.

According to the above, a concentric annular in-lens detector coupled with high stage bias or in-column beam deceleration might provide ultra-high resolution at very low probe-current and low landing- energy conditions. In this work, both the two technologies were employed to directly image SBA-15, KIT-6, MSNSs and MCM-41.

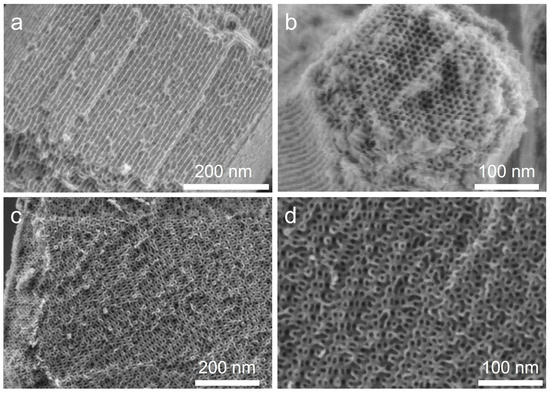

Figure 4 displays LVSEM images of the as-prepared SBA-15 and KIT-6. Figure S7 shows low magnification images of SBA-15; the morphology is bent hexagonal prisms. One can clearly see that the ordered mesoporous channels are fully exposed on the side of the hexagonal prisms. The inter-channel micropores and plugs within channels (Figure 4a) can also be seen, and the cross sections of hexagonal prisms are hexagonally arranged circular-hole structures with ups and downs on the surface (Figure 4b). Fine surface structural details and high S/N rate LVSEM images of SBA-15 were obtained. Image analysis gave the pore size and wall thickness of SBA-15 as about 6.7 and 3.4 nm, respectively.

Figure 4.

LVSEM images of SBA-15 and KIT-6. SBA-15 by integrating a concentric annular in-lens detector and side position in-lens detector with −3.5 kV stage bias (a,b), KIT-6 (c,d) by concentric annular in-lens detector coupled with 8 kV in-column beam deceleration; landing energy = 500 eV.

KIT-6 is cubic structure with Iad symmetry and two types of channel are connected with each other through smaller pores [28]. Large-particle topography and a highly connected pore system result in a severe charge effect and high beam sensitivity. Even at the 1 keV low landing energy of the incident electron beam, there is still existing obvious beam damage (Figure S8a). Although the probe current was decreased to 1.6 pA (Figure S8b) and a newly designed cold field emission SEM was used (Figure S8c), the pore system images are different to the reported results [28]. Therefore, 500 eV landing energy with a tiny probe current was used to collect the LVSEM images of KIT-6 (Figure 4c,d and Figure S9). A whole bulk of the KIT-6 surface fine pore system was obtained (Figure S9a). There are obvious steps (Figure S9a), kinks, vacancies and ledges (Figure 4c,d and Figure S9b) on the surface of KIT-6, which might benefit from the well-focused depth of none-stage bias in-column beam deceleration technology. We can clearly see that the various pores are connected to each other and short-range ordered, which might because the surface is corrugated and is not terminated along well-defined crystal planes. If the surface was polished with Ar ions, long-range ordered pore structure could be observed [40]. The pore size and wall thickness of KIT-6 are about 6.3 nm and 3.8 nm, respectively, which is in agreement with other methods.

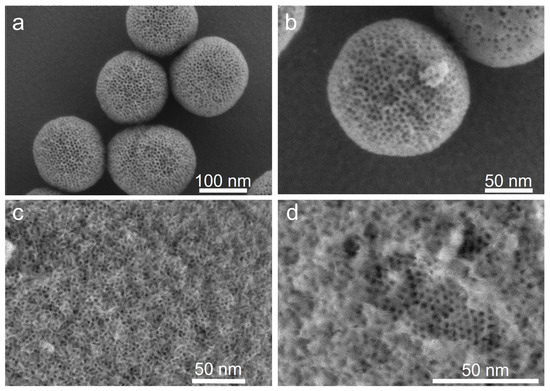

Although the high-resolution LVSEM has made tremendous progress, under 3 nm porous material LVSEM image reports were very rare [28]. Figure 5a,b and Figure S10 show that the morphology of MSNSs are nanospheres with unordered craters on the surface. The absence of parallel channels suggests that the mesoporous silica might be 3D-dendritic. Pore size of MSNSs is about 2.8 nm. Figure 5c,d show ultra-high magnification LVSEM images of MCM-41 with 500 eV landing energy. Some amorphous silica can be seen on the surface of MCM-41 in Figure 5c, but a regular hexagonal array of uniform channels can also be found in Figure 5d. The image analysis gave the pore size range as 1.8 nm to 2.1 nm and the wall thickness is about 1.7 nm. Figure S11 shows a 1 keV landing energy LVSEM image of the MCM-41. The high landing energy of the incident electron beam is too high, resulting in poor practical spatial resolution. However, these results not only give the high-quality surface details of several types of mesoporous silica, but also show that a LVSEM with a current of less than 500 eV can also directly resolve ordered details of approximately 1.8 nm on the surface.

Figure 5.

LVSEM images of MSNSs and MCM-41. MSNSs by concentric annular in-lens detector coupled with 8 kV in-column beam deceleration, (a,b), MCM-41 (c,d) by integrating a concentric annular in-lens detector and side position in-lens detector with −3.5 kV stage bias; landing energy = 500 eV.

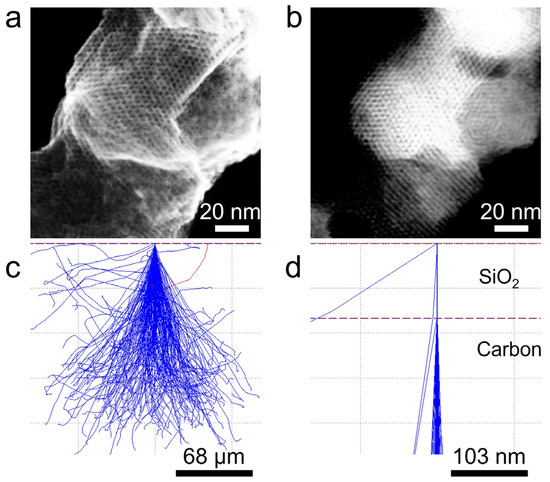

Interestingly, a 200 kV high-voltage SEM can also directly image the ~2 nm pore size MCM-41. Figure 6a shows a 200kV SEM image of MCM-41, while Figure 6b is a high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscope (HAADF-STEM) simultaneous image. The contrast and the S/N rate are also higher than those of the LVSEM images. The regular hexagonal array of uniform channels is more obvious; this might because of the loss of the detail of the amorphous silica on the surface. To determine the reasons for this, Monte Carlo simulations of 2000 electrons were conducted with 200 keV kinetic energy vertically incident to a 100 nm SiO2 membrane supported by carbon (Figure 6d is a magnified image of Figure 6c). In Figure 6d, almost all the electrons break down the SiO2 layer and almost no scattering appears in the SiO2 layer. If the substrate is practical ~20 nm and carbon-membrane supported, the lateral resolution of SEM and STEM are very close to the spot size (~1 nm) of incident electron beam. However, in this method, the sample must be prepared as a TEM sample, and large bulk may also result in a charging effect, which might lead to image shift or loss of surface details.

Figure 6.

200 kV high-voltage SEM image of MCM-41. (a) A 200 kV secondary electron image of MCM-41, (b) HAADF-STEM simultaneous image of MCM-41, (c,d) Monte Carlo simulations of 2000 electrons with 200 keV kinetic energy are vertically incident to a 100 nm SiO2 membrane supported by carbon.

3. Conclusions

In conclusion, we reviewed the advance of ultra-high-resolution SEM technology, and its benefits and drawbacks compared to other technologies, as well as its application in imaging of mesoporous silica. We directly imaged ~7 nm pore size SBA-15, ~6 nm pore size KIT-6, ~3 nm pore size MSNSs and even ~2 nm pore size MCM-41 using under 500 V LVSEM with beam deceleration technology. We demonstrated that the under 500 V LVSEM technique can directly resolve approximately 1.8 nm ordered details on the surface. Unprecedented highest-quality 3D topography and surface pore system images of these four kinds of mesoporous silica are provided. These results will allow for a better understanding of the pore system structures and applications of ordered mesoporous materials. Two methods were discussed and demonstrated be efficient in obtaining high-resolution SEM images of mesoporous silica. These methods were LVSEM and 200 kV high-voltage SEM.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152312845/s1, Figure S1: X-Ray Diffraction and N2-sorption characterization of as-prepared mesoporous silica. Figure S2: LVSEM of SBA-15 by Low position E-T detector. Figure S3: LVSEM of SBA-15 by in-lens detector. Figure S4: LVSEM of SBA-15 by BSE detector (a) and side position in-lens detector (b). Figure S5: LVSEM of SBA-15 by concentric annular in-lens detector with different stage bias. Figure S6: LVSEM images of KIT-6 by integrate concentric annular in-lens detector and side position in-lens detector with -3.5 kV stage bias. Figure S7: LVSEM of SBA-15. Figure S8: 1 keV LVSEM of KIT-6. Figure S9: LVSEM of KIT-6. Figure S10: LVSEM of MSNSs. Figure S11: LVSEM of MCM-41 with 1 keV landing energy. Figure S12: LVSEM of SBA-15 with templates residue. Figure S13: Schematic of the detector systems of FEI Nova Nano SEM 450 and Thermo Fisher Apreo S. Figure S14: Schematic of the detector systems of JEOL JSM-7600F and JEOL JSM-7900F. Figure S15: Schematic of the detector systems of Zeiss Gemini SEM 500. Figure S16: Schematic of the detector systems of Hitachi S4800 (a, b) and Hitachi Regulus 8240 (c, d). Figure S17: Comparison of imaging performance of SBA-15 (side view). Figure S18: Comparison of imaging performance of SBA-15 (top view). Figure S19: Comparison of imaging performance of KIT-6. Figure S20: Comparison of imaging performance of MSNSs first generation. Figure S21: Comparison of imaging performance of MCM-41.

Author Contributions

L.W.: Data curation, Writing—original draft, Preparation, Writing—review & editing. D.Z.: Writing—review and editing, Validation, Visualization, Software. Y.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology. Y.D.: Funding acquisition, Resources, Conceptualization, Methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. BK20201246), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12 274 202) and Jiangsu Provincial Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program (Grant No. KYCX25_0264).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical support provided by Yang Yu from Carl Zeiss Shanghai Company, Qin Luo from Hitaichi High-Tech Shanghai Company and Xiaowei Fang From Hefei Guojing Instrument Technology Co., Ltd.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Kresge, C.; Leonowicz, M.; Roth, W.; Vartuli, J.; Beck, J. Ordered mesoporous molecular sieves synthesized by a liquid crystal template mechanism. Nature 1992, 359, 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazov, M.; Davis, M. Catalysis by framework zinc in silica-based molecular sieves. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Zhou, W.; Li, H.; Ren, L.; Qiao, P.; Li, W.; Fu, H. Synthesis of Particulate Hierarchical Tandem Heterojunctions toward Optimized Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1804282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, M.; Pang, S.; Jones, C. Adsorption Micro-calorimetry of CO2 in Confined Amino polymers. Langmuir 2017, 33, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunathilake, C.; Jaroniec, M. Mesoporous calcium oxide-silica and magnesium oxide-silica composites for CO2 capture at ambient and elevated temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 10914–10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Yang, J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, B.; Lv, Y.; Xu, C.; Asiri, A.; Zi, J.; et al. Dual-Pore Mesoporous Carbon@Silica Composite Core−Shell Nanospheres for Multidrug Delivery. Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 5470–5474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Zink, J. Probing the Local Nanoscale Heating Mechanism of a Magnetic Core in Mesoporous Silica Drug-Delivery Nanoparticles Using Fluorescence Depolarization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 5212–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shen, D.; Chen, G.; Elzatahry, A.; Pal, M.; Zhu, H.; Wu, L.; Lin, J.; Al-Dahyan, D.; Li, W.; et al. Mesoporous Silica Thin Membranes with Large Vertical Mesochannels for Nanosize-Based Separation. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1702274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Shi, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhao, S.; Ji, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, C. Amino-modified hollow mesoporous silica nanospheres-incorporated reverse osmosis membrane with high performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 581, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Mesoporous Materials for Energy Conversion and Storage Devices. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kani, K.; Malgras, V.; Jiang, B.; Hossain, M.; Alshehri, S.; Ahamad, T.; Salunkhe, R.; Huang, Z.; Yamauchi, Y. Periodically Arranged Arrays of Dendritic Pt Nanospheres Using Cage-Type Mesoporous Silica as a Hard Template. Chem. Asian J. 2018, 13, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirin, D.; Protesescu, L.; Trummer, D.; Kochetygov, I.; Yakunin, S.; Krumeich, F.; Stadie, N.; Kovalenko, M. Harnessing defect-tolerance at the nanoscale: Highly luminescent lead halide perovskite nanocrystals in mesoporous silica matrixes. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 5866–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlsson, A.; Kaneda, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Terasaki, O.; Ryoo, R.; Joo, S. The structure of MCM–48 determined by electron crystallography. J. Electron Microsc. 1999, 48, 795–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Kaneda, M.; Terasaki, O.; Zhao, D.; Kim, J.; Stucky, G.; Shin, H.; Ryoo, R. Direct imaging of the pores and cages of three-dimensional mesoporous materials. Nature 2000, 408, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneda, M.; Tsubakiyama, T.; Carlsson, A.; Sakamoto, Y.; Ohsuna, T.; Terasaki, O.; Joo, S.; Ryoo, R. Structural study of mesoporous MCM-48 and carbon networks synthesized in the spaces of MCM-48 by electron crystallography. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asahina, S.; Uno, S.; Suga, M.; Stevens, S.; Klingstedt, M.; Okano, Y.; Kudo, M.; Schüth, F.; Anderson, M.; Adschiri, T.; et al. A new HRSEM approach to observe fine structures of novel nanostructured materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2011, 146, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cen, X.; Ravichandran, R.; Hughes, L.; Benthem, K. Simultaneous scanning electron microscope imaging of topographical and chemical contrast using in-lens, in-column, and everhart-thornley detector systems. Microsc. Microanal. 2016, 22, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, D. Control of charging in low-voltage SEM. Scanning 1989, 11, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, S.; Lund, K.; Tatsumi, T.; Iijima, S.; Joo, S.; Ryoo, R.; Terasaki, O. Direct observation of 3D mesoporous structure by scanning electron microscopy (SEM): SBA-15 silica and CMK-5 carbon. Angew. Chem. 2003, 42, 2182–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Feng, J.; Huo, Q.; Melosh, N.; Fredrickson, G.; Chmelka, B.; Stucky, G. Triblock Copolymer Syntheses of Mesoporous Silica with Periodic 50 to 300 Angstrom Pores. Science 1998, 279, 548–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodusch, N.; Demers, H.; Gauvin, R. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy: New Perspectives for Materials Characterization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kjellman, T.; Asahina, S.; Schmitt, J.; Impéror-Clerc, M.; Terasaki, O.; Alfredsson, V. Direct observation of plugs and intrawall pores in SBA-15 using low voltage high resolution scanning electron microscopy and the influence of solvent properties on plug-formation. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 4105–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraide, S.; Yamada, M.; Kataoka, S.; Inagi, Y.; Endo, A. Time evolution of the framework structure of SBA-15 during the aging process. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects. 2019, 583, 123807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, D.; Weinberg, G.; Su, D.; Bao, X. Engineered Complex Emulsion System: Toward Modulating the Pore Length and Morphological Architecture of Mesoporous Silicas. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 25908–25915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jóźwik, I.; Jagielski, J.; Caban, P.; Kaminski, M.; Kentsch, U. Direct visualization of highly resistive areas in GaN by means of low-voltage scanning electron microscopy. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 138, 106293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, C. Imaging mechanism and contrast separation in low-voltage scanning electron microscopy imaging of carbon nanotube arrays on SiO2/Si substrate. Carbon 2023, 213, 118175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitta, M. Visualization of lithiated/delithiated particle distribution in Li4Ti5O12 electrode by ultralow-voltage scanning electron microscopy imaging. Electrochem. Commun. 2025, 170, 107849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüysüz, H.; Lehmann, C.; Bongard, H.; Tesche, B.; Schmidt, R.; Schüth, F. Direct Imaging of Surface Topology and Pore System of Ordered Mesoporous Silica (MCM-41, SBA-15, and KIT-6) and Nanocast Metal Oxides by High Resolution Scanning Electron Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 11510–11517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inada, H.; Su, D.; Egerton, R.; Konno, M.; Wu, L.; Ciston, J.; Wall, J.; Zhu, Y. Atomic imaging using secondary electrons in a scanning transmission electron microscope: Experimental observations and possible mechanisms. Ultramicroscopy 2011, 111, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Vilas, A. (Ed.) Current Microscopy Contributions to Advances in Science and Technology; Formatex Research Center: Badajoz, Spain, 2012; pp. 1052–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, H.; Grunder, S.; Cordova, K.; Valente, C.; Furukawa, H.; Hmadeh, M.; Gándara, F.; Whalley, A.; Liu, Z.; Asahina, S.; et al. Large-Pore Apertures in a Series of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Science 2012, 336, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, R.; Li, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, D. Biphase Stratification Approach to Three-Dimensional Dendritic Biodegradable Mesoporous Silica Nanospheres. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayari, A.; Han, B.; Yang, Y. Simple Synthesis Route to Monodispersed SBA-15 Silica Rods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 14348–14349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, J.; Ma, D.; Bao, X.; Klein-Hoffmann, A.; Weinberg, G.; Su, D.; Schlögl, R. Unusual Mesoporous SBA-15 with Parallel Channels Running along the Short Axis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7440–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, A.; Yamada, M.; Kataoka, S.; Sano, T.; Inagi, Y.; Miyaki, A. Direct observation of surface structure of mesoporous silica with low acceleration voltage FE-SEM. Colloids Surf. A 2010, 357, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, S.; Takeuchi, Y.; Kawai, A.; Yamada, M.; Kamimura, Y.; Endo, A. Controlled Formation of Silica Structures Using Siloxane/Block Copolymer Complexes Prepared in Various Solvent Mixtures. Langmuir 2013, 29, 13562–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, X.; Yao, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, A.; Li, W.; Wu, W.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhao, D. Conformal Coating of Co/N-Doped Carbon Layers into Mesoporous Silica for Highly Efficient Catalytic Dehydrogenation-Hydrogenation Tandem Reactions. Small 2017, 13, 1702243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suga, M.; Asahina, S.; Sakuda, Y.; Kazumori, H.; Nishiyama, H.; Nokuo, T.; Alfredsson, V.; Kjellman, T.; Stevens, S.; Cho, H.; et al. Recent progress in scanning electron microscopy for the characterization of fine structural details of nano materials. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2014, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Hao, Z. Mesoporous KIT-6 silica-polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mixed matrix membranes for gas separation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 8650–8658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, W.; Xu, F.; Shi, J. Combining scanning electron microscopy and fast Fourier transform for characterizing mesopore and defect structures in mesoporous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 220, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).