Discrete Element Simulations of Fracture Mechanism and Energy Evolution Characteristics of Typical Rocks Subjected to Impact Loads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Establishment of Numerical Simulation Model and Parameter Calibration

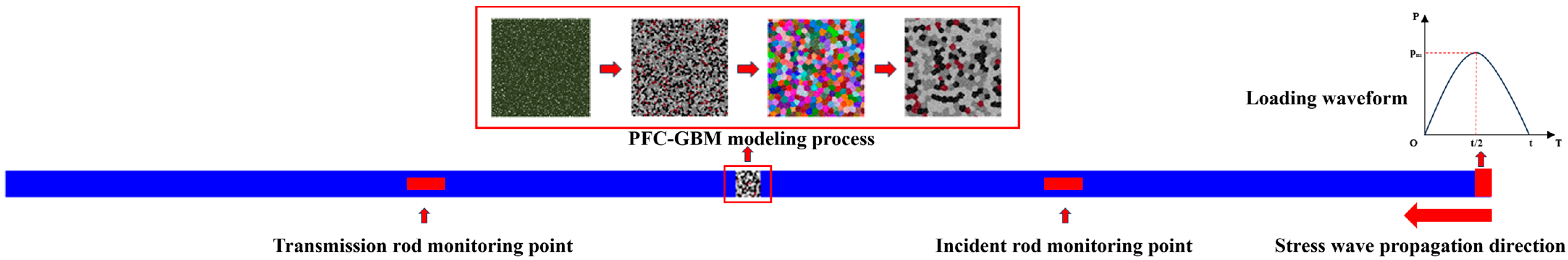

2.1. Establishment of Numerical Simulation Model

- (1)

- An axisymmetric elastic rod is generated in FLAC, with both the incident and transmission rods having a length of 1.8 m, a diameter of 50 mm, a density of 7.89 g/cm3, an elastic modulus of 220 GPa, and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.21.

- (2)

- A PFC2D specimen with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 50 mm is created at the center of the rod-to-rod interface.

- (3)

- The FLAC grid surfaces at both ends of the specimens are defined as coupling boundaries, and the corresponding PFC particle groups at the specimen ends are designated as coupling boundaries. At each global time step, the average normal stress on the FLAC coupling boundary is transferred as a boundary load to the PFC coupling boundary, while the reaction force on the PFC side is fed back as an equivalent nodal force to FLAC.

- (4)

- In FLAC, an incident stress wave is applied at the left end of the incident rod in the form of a half-sine pulse p(t), and the transmitted and reflected waves are recorded through monitoring points.

- (5)

- During dynamic loading, FLAC and PFC apply load waveforms to the units at specified intervals, while exchanging force-velocity data at a frequency of 1 kHz to maintain synchronization between the two software programs.

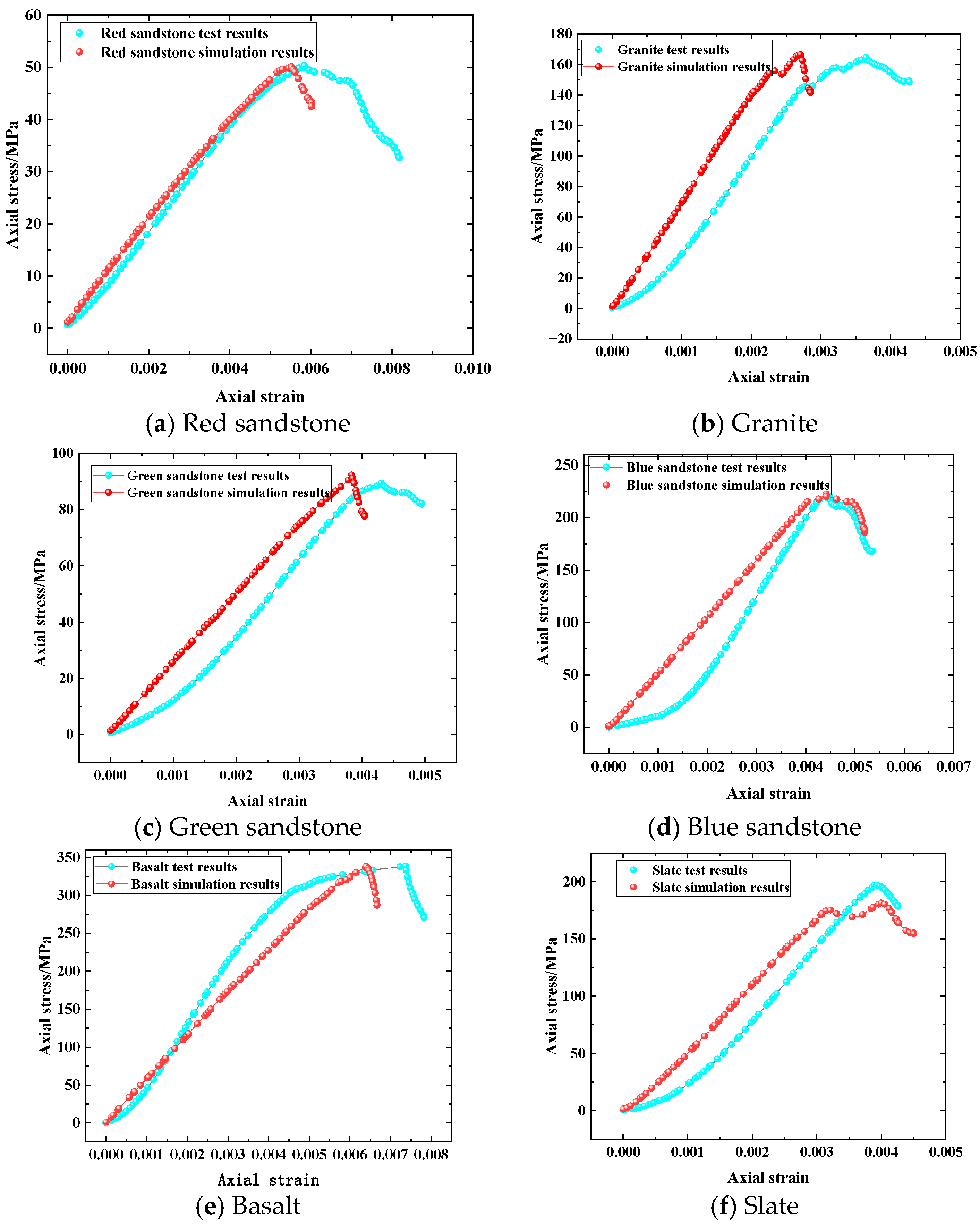

2.2. Parameter Calibration

3. Discrete Element Simulation Method of Moment Tensor Acoustic Emission

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Analysis of Acoustic Emission Characteristics Under Impact Load

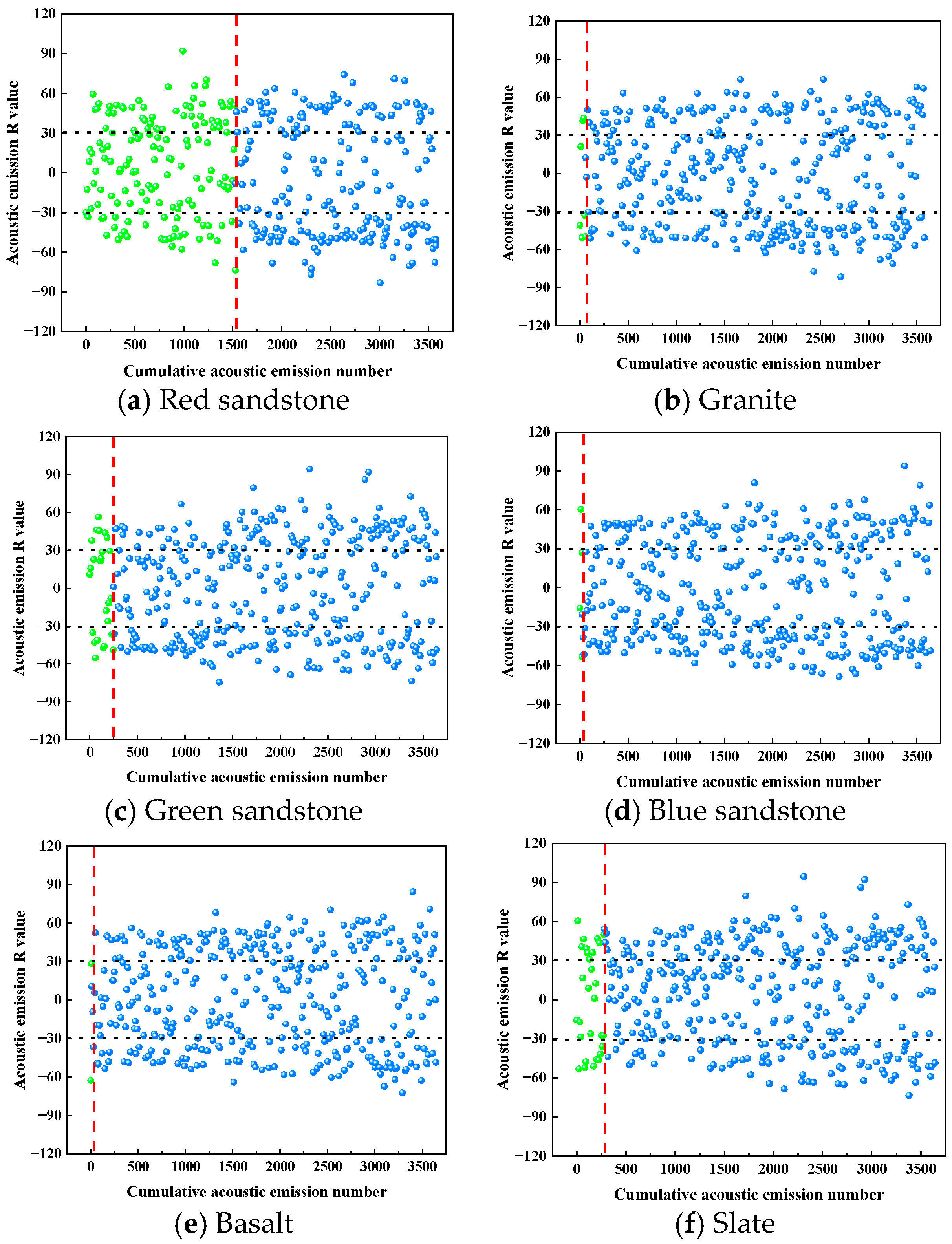

4.1.1. Characteristics of Acoustic Emission R-Value and Distribution of Focal Types

4.1.2. Acoustic Emission B-Value Characteristics

4.1.3. Analysis of AE T-K Diagram

4.2. Study on the Relationship Between Energy-Time Density and B-Value

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under impact loading, the R-values for each lithology display considerable variability and are generally uniform, indicative of a typical composite failure mechanism. The R-values tend to cluster before the stress peak, suggesting that the material undergoes significant microstructural adjustments before reaching peak stress, resulting in an increased presence of microcracks. The variations in rock types do not appear to influence the distribution characteristics of R-values under impact loading; however, they do affect the failure characteristics observed before and after the stress peak.

- (2)

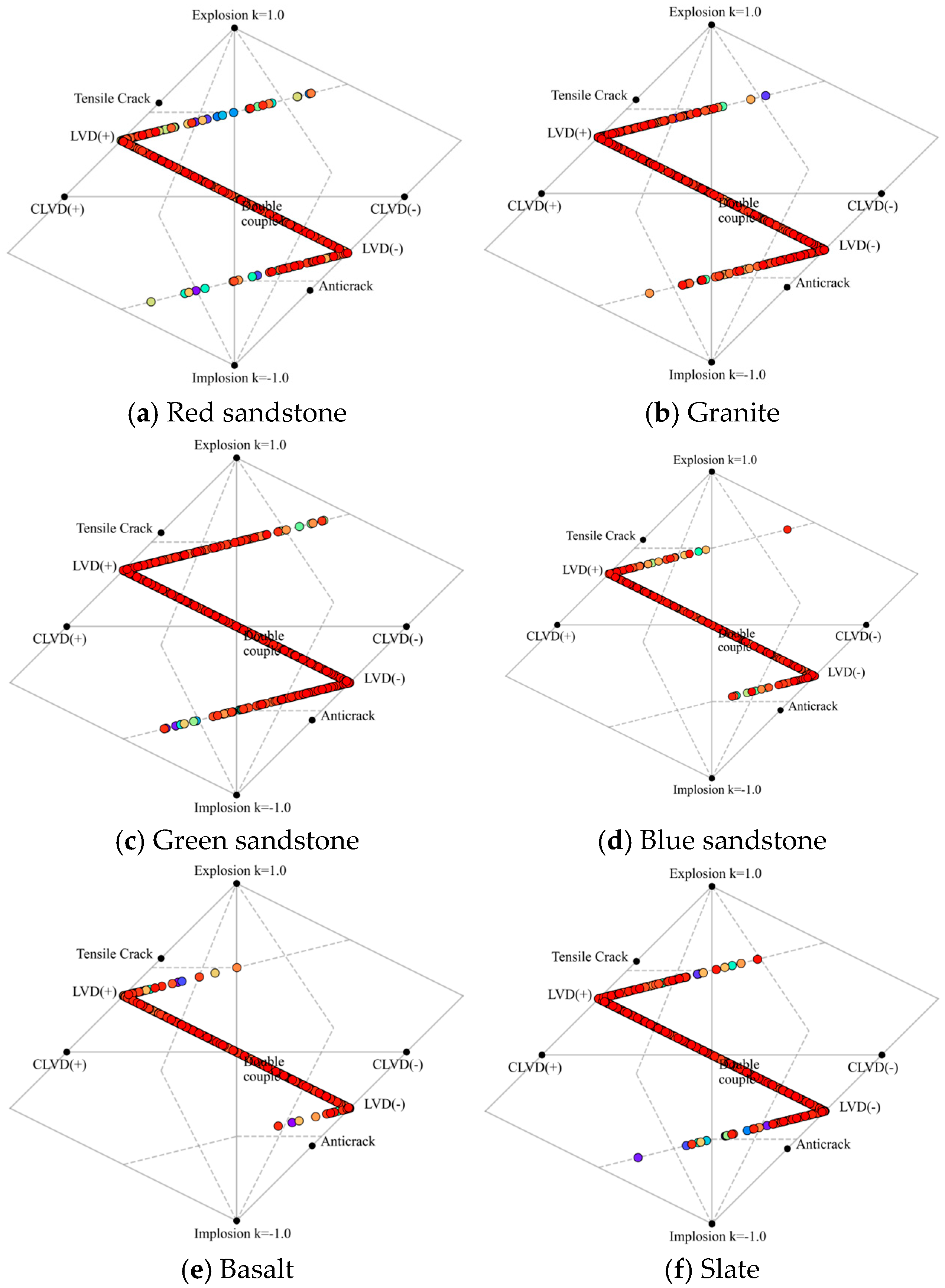

- During impact loading, seismic sources associated with lithologies exhibit a greater density at the boundaries, demonstrating a pattern of aggregation from the boundary into the interior of the sample. The observed distribution features are almost intricate, mainly characterized by shear–tension–implosion interactions, with point clouds predominantly located at grain–grain interfaces. This reflects the critical roles of stress concentration and interface weakening in facilitating impact failure. Notably, the proportion of shear-type sources ranges between 36% and 61%, indicating that tensile cracking is the predominant mode of rock failure.

- (3)

- The AE fracture strength across different lithologies primarily ranges from –8.25 to –5.25, with peak frequencies situated between –7 and –6. The B-values for lithologies under study obey the following order: red sandstone > green sandstone > slate > granite > blue sandstone > basalt. The T-k diagram evolves in an inverted “Z” shape, with initial AE events distributed along the LVD (+)-LVD (–) line, dominated by singular crack types. As loading advances, the distribution gradually extends into the CLVD region, signifying an enhancement in crack interactions that culminates in the formation of a fracture zone, leading to macro instability. Rocks possessing a loose structure are more predisposed to progressive failures driven by tensile fractures, while those exhibiting a dense structure or pronounced weak surfaces tend to exhibit more complex failure mechanisms, primarily dominated by CLVD or reverse fractures.

- (4)

- The time–density plots of all rock types almost reveal a steady trend of initially increasing, followed by a subsequent decrease. There exists a correlation between the peak value of energy–time density and the B-value. Rocks characterized by high energy dissipation capacity predominantly display small-amplitude AE events and small-scale fractures, whereas rocks with lower dissipation capacity are primarily associated with large-amplitude AE events and substantial fractures.

- (5)

- It is important to emphasize that there are several limitations in the study, and the numerical results reported here are based on the two-dimensional PFC2D–FLAC model. Since the specimen is approximately in a plane strain state, it may not fully capture the out-of-plane crack branching. In the simulation process, only one random seed was used for each rock type. Future work should involve repeated simulations using multiple random seeds to account for statistical variability. However, this method fails to capture the potential out-of-plane crack branching and the full three-dimensional distribution of dissipated energy. Future work will extend the current approach to three-dimensional coupled PFC–FLAC simulations and incorporate statistical analysis to better quantify the material properties and fracture behavior of different rock types. This will further validate and refine the conclusions drawn in this study.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, W.; Shi, C.; Zhang, C. Numerical Study on the Effect of Grain Size on Rock Dynamic Tensile Properties Using PFC-GBM. Comput. Part. Mech. 2024, 11, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, F.; Mu, J.; Yin, D.; Lu, L.; Chen, Z. Numerical Simulation of Strength and Failure Analysis of Heterogeneous Sandstone under Different Loading Rates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, D.; Braun, A.; Han, Z. Investigation of the Quasi-Brittle Failure of Alashan Granite Viewed from Laboratory Experiments and Grain-Based Discrete Element Modeling. Materials 2017, 10, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gutierrez, M.; Yan, Z. Heterogeneities of Grain Boundary Contact for Simulation of Laboratory-Scale Mechanical Behavior of Granitic Rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2024, 16, 2629–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, B.; Zuo, J.; Massimo, C.; Wu, G.; Liu, H.; Yu, X. Experimental and Numerical Investigation on Meso-Fracture Behavior of Beishan Granite Subjected to Grain Size Heterogeneity. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 292, 109623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wang, F.; Jiang, F.; Huang, G. Study on the Influence of Mineral Composition on the Mechanical Properties of Granite Based on FDEM-GBM Method. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2023, 129, 102834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Li, T.; Chen, G.; Ma, C.; Qiu, S.; Li, Z. The Grain-Based Model Numerical Simulation of Unconfined Compressive Strength Experiment under Thermal-Mechanical Coupling Effect. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 2764–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Yan, Z.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, H. Dynamic Fracture Mechanism from a Pre-Existing Flaw in Granite: Insights from Grain-Based Modelling. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2024, 184, 108810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Bodahi, F.; He, T.; Luo, F.; Duan, S.; Li, M. Sensitivity Analysis of Macroscopic Mechanical Behavior to Microscopic Parameters Based on PFC Simulation. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2022, 40, 3633–3641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizpa, P.; Jamshidi Chenari, R.; Payan, M. PFC/FLAC 3D Coupled Numerical Modeling of Shallow Foundations Seated on Reinforced Granular Fill Overlying Clay with Square Void. Comput. Geotech. 2023, 161, 105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yuan, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X. Scale Effect of Mechanical Properties of Jointed Rock Mass: A Numerical Study Based on Particle Flow Code. Geomech. Eng. 2020, 21, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, M. Acoustic Emission Theory for Moment Tensor Analysis. Res. Nondestruct. Eval. 1995, 6, 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.C.; Stanchits, S.; Main, I.G.; Dresen, G. Comparison of Polarity and Moment Tensor Inversion Methods for Source Analysis of Acoustic Emission Data. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2010, 47, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, E.; Kühn, D.; Vavryčuk, V.; Soldal, M.; Oye, V. Experimental Investigation of Acoustic Emissions and Their Moment Tensors in Rock during Failure. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2014, 70, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Xu, S.; Jin, C.; Liu, Z. Moment Tensor Analysis of Acoustic Emission for Cracking Mechanisms in Rock with a Pre-Cut Circular Hole under Uniaxial Compression. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 135, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Zhu, C.; He, M. Moment Tensor Analysis of Acoustic Emissions for Cracking Mechanisms during Schist Strain Burst. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, X.-P.; Gan, Y. Modeling Acoustic Emission in the Brazilian Test Using Moment Tensor Inversion. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 123, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, L.; Peng, X.; Liu, H.; Jiang, R.-H.; Zhang, L.-Q.; Wang, S. Numerical Study of Voids Geometry Effects on Sandstone’s Mesoscopic Fracture Mechanism: Insights from Acoustic Emission and Moment Tensor Inversion. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 133, 104588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, F.; Xue, L.; Zhai, M.; Huang, X.; Dong, J.; Liang, N.; Xu, C. Evaluation of the Characterization of Acoustic Emission of Brittle Rocks from the Experiment to Numerical Simulation. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Gao, K.; Wu, S.; Long, W. Moment Tensor-Based Approach for Acoustic Emission Simulation in Brittle Rocks Using Combined Finite-Discrete Element Method (FDEM). Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 3903–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Luo, X.; Song, L.; Wang, Y.; Han, M.; Song, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, Z. Analysis of the Cracking Mechanisms in Pre-Cracked Sandstone under Radial Compression by Moment Tensor Analysis of Acoustic Emissions. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2022, 68, 447. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; He, B.; Hou, X.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Stress–Energy Mechanism for Rock Failure Evolution Based on Damage Mechanics in Hard Rock. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Gao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, Y. Research on the Energy Evolution Characteristics and the Failure Intensity of Rocks. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2020, 30, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, C.; Ma, G.; Xu, G.; Ma, C. Energy Damage Evolution Mechanism of Rock and Its Application to Brittleness Evaluation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2019, 52, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, L.; Peng, R.; Ju, Y. Energy Analysis and Criteria for Structural Failure of Rocks. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2009, 1, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Cong, Y.; Meng, F.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Gao, S. Energy Evolution Analysis and Failure Criteria for Rock under Different Stress Paths. Acta Geotech. 2021, 16, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, F. Energy Evolution Mechanism in Process of Sandstone Failure and Energy Strength Criterion. J. Appl. Geophys. 2018, 154, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Liu, J.; Pu, H.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, J. Effects of Cyclic Loading and Unloading Rates on the Energy Evolution of Rocks with Different Lithology. Geomech. Energy Environ. 2023, 34, 100455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, Z.; Xie, T.; Li, X.; Ranjith, P.G. Energy Evolution Characteristics of Hard Rock during Triaxial Failure with Different Loading and Unloading Paths. Eng. Geol. 2017, 228, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Cai, X.; Li, X.; Cao, W.; Du, X. Dynamic Response and Energy Evolution of Sandstone under Coupled Static–Dynamic Compression: Insights from Experimental Study into Deep Rock Engineering Applications. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2020, 53, 1305–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potyondy, D.O. A Grain-Based Model for Rock: Approaching the True Microstructure. In Proceedings of the Bergmekanikk i Norden 2010—Rock Mechanics in the Nordic Countries, Kongsberg, Norway, 9–12 June 2010; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Wang, K.; Liu, C. Effect of Rock Composition Microstructure and Pore Characteristics on Its Rock Mechanics Properties. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Cao, P.; Lin, Q.; Li, S. Mechanical Behaviour of Fracture-Filled Rock-like Specimens under Compression-Shear Loads: An Experimental and Numerical Study. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2021, 113, 102935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.; Xue, L.; Bu, F.; Yang, B.; Huang, X.; Liang, N.; Ding, H. Effects of Bedding Planes on Progressive Failure of Shales under Uniaxial Compression: Insights from Acoustic Emission Characteristics. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 119, 103343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zineddin, M.; Krauthammer, T. Dynamic Response and Behavior of Reinforced Concrete Slabs under Impact Loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2007, 34, 1517–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cai, M.; Huang, M. Mechanical Properties of Brittle Rock Governed by Micro-Geometric Heterogeneity. Comput. Geotech. 2018, 104, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockner, D. The Role of Acoustic Emission in the Study of Rock Fracture. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1993, 30, 883–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, J.F.; Young, R.P. Moment Tensors and Micromechanical Models. Tectonophysics 2002, 356, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, T.C.; Kanamori, H. A Moment Magnitude Scale. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1979, 84, 2348–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, J.; Ma, J.; Cai, X. Failure Mechanism Analysis of Rock in Particle Discrete Element Method Simulation Based on Moment Tensors. Comput. Geotech. 2021, 136, 104215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Z.; Li, X.; Hou, P.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y. Moment Tensor Analysis of Transversely Isotropic Shale Based on the Discrete Element Method. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.W.; Davidsen, J.; Pedersen, P.K.; Boroumand, N. Breakdown of the Gutenberg-Richter Relation for Microearthquakes Induced by Hydraulic Fracturing: Influence of Stratabound Fractures. Geophys. Prospect. 2014, 62, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aki, K.; Richards, P.G. Quantitative Seismology: Theory and Methods; A series of books in geology; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-7167-1058-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, J.A.; Pearce, R.G.; Rogers, R.M. Source Type Plot for Inversion of the Moment Tensor. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 1989, 94, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajyaguru, A.; Metzler, R.; Cherstvy, A.G.; Berkowitz, B. Quantifying Anomalous Chemical Diffusion through Disordered Porous Rock Materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2025, 27, 9056–9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Roubinet, D.; Lei, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Anomalous Transport and Upscaling in Critically-Connected Fracture Networks under Stress Conditions. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Kang, Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Flawed Granite under Dynamic Loading. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 142, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, L.; Xu, Z.; Wang, J.; Deng, D.; Xu, J.; Hu, Z. A New Index of Energy Dissipation Considering Time Factor under the Impact Loads. Materials 2022, 15, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute Group | Parameter | Red Sandstone | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic particle group | Minimum particle radius Rmin (mm) | 0.05 | |||

| Particle radius ratio Rmax/Rmin | 1.66 | ||||

| Grain density ρ (kg·m−3) | 2500 | ||||

| Elastic modulus of particles E (GPa) | 36 | ||||

| Particle friction coefficient μ | 0.5 | ||||

| Mineral particle group | Mineral matter group | Plagioclase | Quartz | Calcite | Other |

| Parallel bond modulus E* (GPa) | 5.57 | 5.41 | 5.09 | 4.61 | |

| Parallel bond tensile strength σt* (MPa) | 6.24 | 5.61 | 4.98 | 4.88 | |

| Parallel bonding cohesion c* | 8.31 | 7.48 | 6.65 | 6.44 | |

| Parallel bonding friction angle φ* | 30 | ||||

| Parallel bond stiffness ratio K* | 1.5 | ||||

| Mineral boundary group | SJM stiffness ratio k*sj | 2.6 | |||

| SJM friction factor μsj | 0.3 | ||||

| SJM tensile strength σt_sj (MPa) | 2.22 | ||||

| SJM cohesive strength csj | 27.44 | ||||

| Rock | Experiment | Simulation | Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ/MPa | E/GPa | σ/MPa | E/GPa | σ/% | E/% | |

| Red sandstone | 50.26 | 8.61 | 50.04 | 9.08 | 0.43 | 5.46 |

| Granite | 164.49 | 65.96 | 166.49 | 71.93 | 1.22 | 9.05 |

| Green sandstone | 89.43 | 27.57 | 92.36 | 24.65 | 3.27 | 10.59 |

| Blue sandstone | 220.70 | 76.77 | 222.37 | 54.26 | 0.76 | 29.32 |

| Basalt | 338.65 | 82.72 | 338.52 | 55.74 | 0.04 | 32.62 |

| Slate | 197.19 | 65.48 | 181.52 | 60.25 | 7.95 | 7.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, D.; Guo, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Hua, J. Discrete Element Simulations of Fracture Mechanism and Energy Evolution Characteristics of Typical Rocks Subjected to Impact Loads. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12847. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312847

Deng D, Guo L, Li Y, Liu G, Hua J. Discrete Element Simulations of Fracture Mechanism and Energy Evolution Characteristics of Typical Rocks Subjected to Impact Loads. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12847. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312847

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Ding, Lianjun Guo, Yuling Li, Gaofeng Liu, and Jiawei Hua. 2025. "Discrete Element Simulations of Fracture Mechanism and Energy Evolution Characteristics of Typical Rocks Subjected to Impact Loads" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12847. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312847

APA StyleDeng, D., Guo, L., Li, Y., Liu, G., & Hua, J. (2025). Discrete Element Simulations of Fracture Mechanism and Energy Evolution Characteristics of Typical Rocks Subjected to Impact Loads. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12847. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312847