Abstract

It is well known that elevated phosphate concentrations in water bodies trigger the eutrophication process, posing adverse environmental, health, and economic consequences that necessitate effective removal solutions. Phosphate removal has therefore been widely studied using various methods, including chemical precipitation, membrane filtration, and crystallisation. However, most of these methods are often expensive or inefficient for low phosphate concentrations. Therefore, in this study, an eco-friendly, sustainable and biodegradable adsorbent was manufactured by extracting calcium ions from an industrial by-product, ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) and magnesium ions from magnesium dross (MgD), then immobilising them on sodium alginate to form Ca-Mg-SA beads. The new adsorbent was applied to remove phosphate from water under different flow patterns (batch and continuous flow), initial pH levels, contact times, agitation speeds and adsorbent doses. Additionally, the degradation time of the new adsorbent, recycling potential, its morphology, formation of functional groups and chemical composition were investigated. The results obtained from batch experiments demonstrated that the new adsorbent achieved 90.2% phosphate removal efficiency from a 10 mg/L initial concentration, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 1.75 mg P/g at an initial pH of 7, a contact time of 120 min, an agitation speed of 200 rpm and an adsorbent dose of 1.25 g/50 mL. The column experiments demonstrated a 0.82 mg P/g removal capacity under the same optimal conditions as the batch experiments. The findings also showed that the adsorption process fitted well to the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm models and followed a pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Characterisation of Ca-Mg-SA beads using EDX, SEM and FTIR confirmed successful ion immobilisation and phosphate adsorption. Furthermore, the beads fully biodegraded in soil within 75 days and demonstrated potential recycling as a fertiliser.

1. Introduction

Phosphorus, while a vital element for all living creatures, becomes problematic when present in excessive amounts in water bodies. The increasing phosphate concentration, primarily from fertilisers, agricultural runoff from soil, industrial effluents and domestic wastewater, causes devastating effects on aquatic systems, such as eutrophication [1]. Eutrophication is an excessive algal and aquatic plant bloom that disrupts the balance of aquatic organisms and degrades water quality. During eutrophication, a thick, floating mat forms on the surface of the water, preventing light from reaching organisms below. After their death, these organisms settle at the bottom and are digested by bacteria, which cause bacterial blooms alongside the algal bloom, leading to the depletion of dissolved oxygen and the release of carbon dioxide with unpleasant smells. The lack of dissolved oxygen leads to anoxia. This causes phosphate to be released from sediments over time, triggering further eutrophication [2].

Eutrophication significantly threatens the biodiversity of aquatic organisms, as sensitive species may disappear when ecosystem conditions change, with documented cases showing a diminution of up to 60% in coral biodiversity in Indonesia [3]. Furthermore, economic consequences include significant losses in fish farming due to the presence of dinoflagellates and toxic red algae on the shores [4]. Méndez Pasarín [5] estimated the total annual cost in the United Kingdom (UK) for repairing eutrophication damage across various categories (environmental, social, economic, and human health) at about $105–160 million. In 2005, the Environmental Protection Agency identified eutrophication as a significant threat to water quality in Ireland. It was also classified as the most prevalent threat to water quality in Northern Ireland, while 23% of the lakes in the UK were classified as eutrophic water bodies [5].

The Water Framework Directive has established acceptable phosphate limits ranging from 10 to 1000 µg/L to avoid its devastating consequences. Therefore, many techniques, including biological, chemical, and physical methods, were applied to eliminate phosphate from water and wastewater. Although they showed good removal efficiency, their drawbacks limit their applications [6].

The biological method, which utilises living microorganisms, is not expensive and can achieve high phosphate removal efficiency. However, it is slow (requires days), and it is very sensitive to the variation of operating parameters [7]. In contrast, chemical methods such as precipitation using Fe and Ca ions overcome the main disadvantages of biological treatment methods because they are faster and less sensitive to changing operating conditions. However, they are considered expensive due to chemical requirements, while sludge production is another disadvantage of this method [8]. Physical methods, such as membrane and filtration technologies, demonstrate high phosphate removal efficiency within a very short time; nevertheless, these methods have some disadvantages, such as membrane fouling, high power consumption, and considerable amounts of produced sludge [9].

Adsorption has emerged as a promising solution for phosphate removal due to its ease of operation, affordability and low energy consumption [6]. Various natural materials and industrial by-products with high aluminium, calcium, magnesium, and/or iron content were used to develop efficient adsorbents for phosphate removal from water and wastewater, due to the affinity of these ions for phosphate. However, using natural materials is an unsustainable approach because it depletes natural resources, while commercial ones are very expensive. Therefore, using industrial by-products to remove phosphate has several advantages, including affordability compared to commercial adsorbents and eco-friendliness (promoting recycling and sustainability) [8].

For instance, Yang, et al. [10] developed a new adsorbent material named GS-Z2M using gasification slag mixed with zirconium (at molar ratios of 1:1, 2:1 and 3:1 of zirconium to Fe3O4). GS-Z2M showed a high specific surface area (188 m2/g) and good phosphate removal capacity under dynamic flow conditions. Shi, et al. [11] also developed an adsorbent using steel slag with MgCl2 to remove ammonia nitrogen and phosphate, and the results showed that the new adsorbent exhibited high removal efficiency (94.56%).

The reviewed literature by the authors showed that the majority of the available treatment methods for phosphate elimination from water are either expensive, slow or have low efficiency. This research, therefore, aims to develop an eco-friendly, affordable, sustainable and efficient adsorbent that uses waste materials to source the key adsorbing chemicals. Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), a major by-product of iron and power production industries, is used as a source of calcium (Ca), while magnesium dross, a by-product from the production of magnesium alloys, serves as a source of magnesium (Mg) ions. The extracted ions are immobilised on sodium alginate (a natural, affordable and biodegradable polymer) to manufacture an eco-friendly adsorbent to remove phosphate from water. The efficiency of the new adsorbent has been evaluated through batch and column experiments, investigating the effects of the pH of water, adsorbent dosage, agitation speed, Mg and Ca ion loading and contact time. By transforming industrial waste into valuable resources while reducing waste management costs and avoiding the environmental, social and financial burdens associated with by-product landfilling, the proposed research addresses two environmental challenges: phosphate pollution and industrial waste management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

UK waste companies supplied the two by-products (GGBS and MgD), while the chemicals, including HCl (32%), calcium chloride, sodium hydroxide, sodium alginate and potassium phosphate monobasic (KH2 PO4), were purchased from Merck, UK. The GGBS and MgD were subjected to X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis. This technique analyses solid samples non-destructively through X-radiation and obtaining their chemical compositions. The test was carried out to investigate the chemical composition of the selected materials to assess their feasibility for phosphate adsorption. Table 1 illustrates the chemical composition of GGBS and MgD.

Table 1.

The concentrations of the key oxides in GGBS and MgD.

2.2. Preparation of the Adsorbent

2.2.1. Extraction Process

The extraction of Ca ions from GGBS and Mg ions from MgD was conducted using varying amounts of HCl (32% v/v): 1–13 mL for GGBS samples and 1–12 mL for MgD samples to determine the optimal concentrations of these ions. Twenty-five experimental flasks were prepared, each containing 100 mL of deionised water (DW). Thirteen flasks received 2 g of GGBS, while twelve flasks received 2 g of MgD. Then, HCl was added in varying amounts (1–13 mL for GGBS flasks and 1–12 mL for MgD flasks). After addition, the flasks were agitated using a shaker incubator (Labnet) for 3 h at 200 rpm and room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). Subsequently, 5 mL samples were collected from each flask and filtered using Whatman Grade 5 filter paper to remove solid residue. Finally, the concentrations of Ca and Mg were quantified using Hach-Lange hardness test cuvettes (LCK327) and a spectrophotometer (DR 3900).

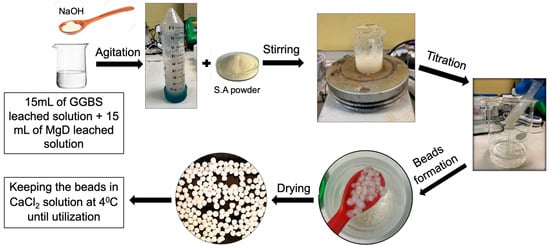

2.2.2. Immobilisation of Ions on Sodium Alginate and Bead Formation

The dissolved Ca and Mg ions were converted to a suspended state by adding NaOH to both leached solutions obtained from the extraction process until the pH reached 12. The solutions were then mixed and shaken for 3 h. After shaking, 30 mL of the agitated solution was mixed with 1 g of sodium alginate powder using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) for 2 h at 600 rpm. The resulting slurry was then added dropwise into a 0.1 M CaCl2 bath using a disposable pipette to initiate polymerisation and bead formation. The freshly formed beads were aged in this solution for 12 h, washed twice with DW, dried at 70 °C for 30 min (this step helps to fix the bead shape and increase their stiffness), and then stored at 4 °C in a 5 mM CaCl2 solution until further use. It is noteworthy that storing the beads in a dilute solution of CaCl2 helps to prevent the breakage of the Ca cross-linkages, which softens the gel [12].

The size of the resulting beads was measured, after drying, using a microscope (Nikon SMZ25) (Figure 1). Additionally, Figure 2 summarises the complete procedure for Ca-Mg-SA bead preparation.

Figure 1.

Diameter of beads (measured using a microscope).

Figure 2.

The procedures of adsorbent manufacturing.

To optimise the ion content and subsequent removal efficiency, the procedure was repeated using different amounts of GGBS and MgD (2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 g). This systematic variation enabled the determination of the optimal loading conditions for maximum phosphate removal efficiency.

2.3. Batch Adsorption Methodology

Batch experiments were conducted in triplicate to examine the effects of various parameters (initial pH values, initial concentrations, agitation speeds, adsorbent doses, and contact times) on phosphate removal efficiency using Ca-Mg-SA beads. The aim was to obtain the optimum conditions for maximum phosphate removal. These parameters were examined due to their potential impact on the phosphate removal efficiency. Several flasks (4 to 10) of 250 mL were prepared, and 50 mL volume (V) of phosphate stock solution with a specific initial concentration () ranging from 10 to 60 mg/L was added to each flask. Various masses of beads (m) ranging from 0.25 to 1.5 g were added and agitated for 2 h at 200 rpm at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). The effect of initial pH on phosphate removal efficiency was examined using various initial pH values (3 to 12). The initial pH value was adjusted to the desired value using measured amounts of NaOH or HCl. The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the new adsorbent was evaluated using the ∆pH/solid addition method. This method involves measuring the initial and final pH values of the solution during the adsorption process. The point at which the initial and final pH values are equal (ΔpH = 0) represents the pHpzc (where the surface charge on the adsorbent equals zero) [13]. Contact time and agitation speeds were adjusted to the desired values using a stopwatch and the regulator (on the agitator), respectively. Adsorbent doses were measured using a 3-digit scale. Before weighing, beads were removed from the storage solution and allowed to drain for approximately 30 s to minimise variability from surface moisture, ensuring consistent measurement conditions across all experiments. All experiments were performed in triplicate to minimise experimental error.

The phosphate removal percentage (R) was determined by measuring the equilibrium concentration () in 5 mL aliquots of the solution that were filtered and analysed using Hach-Lange PO4 cuvettes and a Hach-Lange spectrophotometer (Model: DR 2800) according to Equation (1):

where and (mg/L).

The amounts of the removed phosphate by Ca-Mg-SA beads () were calculated using Equation (2):

where in (mg/g), V in (L) and m in (g).

2.4. Adsorbent Characterisation Methods

Three tests were performed to investigate the adsorbent characterisation. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) test was used to confirm the successful immobilisation of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions on sodium alginate and to verify that phosphate was successfully adsorbed onto the new adsorbent. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Thermo Fisher Scientific (PEI) Inspect F50 variable pressure scanning electron microscope operating at 0.1–30 kV to characterise the morphology of the Ca-Mg-SA beads. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) using an Agilent Cary 630 FTIR spectrometer was employed to investigate the chemical bonds and functional groups in the beads before and after phosphate adsorption. Sample preparation for all tests included drying the Ca-Mg-SA beads at 70 °C for one hour; for the FTIR analysis, samples were additionally ground to a fine powder.

2.5. Isotherms and Kinetic Models

2.5.1. Equilibrium Isotherm Models

Equilibrium isotherms generally describe the relationship between solute concentration (, mg/L) and the adsorbed amount of this solute on the adsorbent (solid material) (, mg/g) at a specific temperature. Although the adsorbed quantity of pollutants per mass unit of adsorbent increases with the pollutant concentration, this relationship is not linear [14].

In this study, the two most common isotherms, Langmuir and Freundlich, were used to describe the adsorption process:

Langmuir model: This model assumes that the adsorption process occurs in a homogeneous single layer and that maximum adsorption is achieved at saturation of the monolayer with solute [15]:

where Ce is the equilibrium concentration of pollutant effluent (mg/L), is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), represents the adsorbed amounts of pollutants on adsorbent (mg/g) and is a constant that represents sorption free energy.

Freundlich model: This model can be applied to adsorption processes involving heterogeneous sites and multi-layer systems, following the formula [16]:

where qe represents the adsorbed amount of pollutants on the adsorbent (mg/g), is the equilibrium concentration (mg/L), is the Freundlich isotherm coefficient (mg/g) and n is a dimensionless empirical coefficient.

2.5.2. Adsorption Kinetics Models

The rate of solute transfer from the liquid to the solid phase determines the appropriate design of the adsorption process [14]. The following models were employed to analyse the experimental data obtained in this study.

Pseudo-first-order model: This is a common expression used to describe the rate of adsorption of a solute from an aqueous solution, which can be described as follows:

where qe and qt are the quantities of adsorbed contaminants on the adsorbent at equilibrium and at time t, respectively, in (mg/g) and k1 is the rate constant of the pseudo-first-order model (1/min).

Pseudo-second-order model: This model assumes that adsorption occurs in a monolayer on the surface of the adsorbent, that sorbed species do not interact with each other, and that the adsorption energy is constant for each adsorption site. This is explained by the following equation [17]:

where qe and qt are the quantities of adsorbed pollutants on the adsorbent at equilibrium and at time t (min), respectively, in (mg/g) and k2 is the pseudo-second-order rate constant (g/(mg·min).

Intra-particle diffusion model: This model was proposed by Weber and Morris [18] and it can be described as follows:

where is the constant of adsorption rate (mg/g min0.5) and is the intercept value.

When the plot of qt versus is linear and the intercept equals zero, intra-particle diffusion is the rate-limiting step. Otherwise, other mechanisms are involved alongside diffusion [18].

2.6. Column Experiments (Continuous Flow)

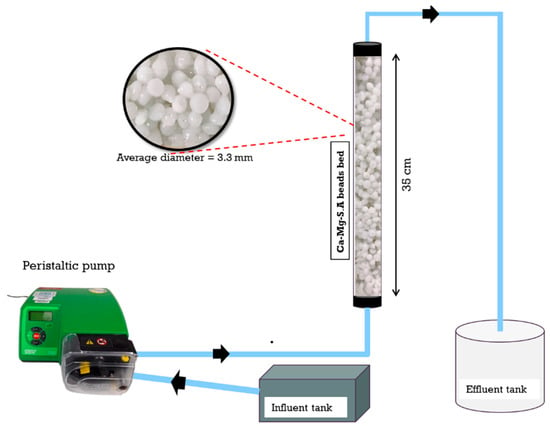

Continuous flow experiments were conducted to investigate the effects of flow rate on phosphate removal efficiency. The column dimensions were determined based on the optimal operational parameters obtained from batch experiments at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min.

The designed system (Figure 3) consists of a vertical acrylic column with a diameter of 26 mm and a height of 35 cm filled with Ca-Mg-SA beads. The column was connected at the bottom to a peristaltic pump (Watson Marlow model 520S) that delivered phosphate solution with an initial concentration of 10 mg/L from a 5 L feed tank to the packed column in upflow mode through 6 mm PVC tubing. The top of the packed column was connected to a 25 L tank to collect the treated water. Effluent samples of 5 mL were collected at various time intervals, filtered using Whatman Grade 5 filter paper and analysed for phosphate using PO4 cuvettes (LCK350) and a Hach-Lange spectrophotometer (Model: DR 3900) until the beads were completely saturated and the effluent concentration equalled the initial phosphate concentration.

Figure 3.

The fixed bed unit (schematic representation, not to scale).

The amount of adsorbed phosphate in column experiments at bed saturation was calculated using the following equation [19]:

where qt is the amount of adsorbed phosphate at bed exhaustion time (mg/g), Q is the flow rate (L/min), m is the mass of used adsorbent in column (g) and ∆t is the difference in time intervals (min), while and are the initial and effluent phosphate concentrations (mg/L), respectively.

Furthermore, the Yoon and Nelson model was employed to describe the adsorption breakthrough curve of the fixed-bed column due to its simplicity and wide applicability.

The Yoon and Nelson model, in its linear formula, can be expressed as follows [20]:

where is the effluent concentration (mg/L), is the influent concentration (mg/L), Kyn is the Yoon-Nelson rate constant (min−1), t is the time (min) and is the time required for 50% breakthrough (min).

2.7. Biodegradability of the Adsorbent

The biodegradability of the Ca-Mg-SA beads was evaluated to determine the time required for complete degradation by soil microorganisms under suitable environmental conditions (water and air). A sample of 1 g of Ca-Mg-SA beads was buried in a container filled with soil and the degradation process was monitored photographically every two weeks, tracking the progressive reduction in bead size until complete degradation. This approach provided a visual timeline of the material’s decomposition rate and environmental persistence. It offered valuable insights into the adsorbent’s end-of-life characteristics and confirmed its biodegradable nature.

2.8. Recycling the Adsorbent as a Fertiliser

The possibility of reusing the adsorbent after treatment (phosphate uptake) as a plant fertiliser has been explored. The presence of some essential plant nutrients in Ca-Mg-SA beads such as phosphate, magnesium and calcium indicates a high possibility of reusing the beads as fertiliser.

Two plants of the same size and species were chosen for the experiment under the same environmental conditions. Three grams of used beads were added weekly to one plant only, while both plants received daily water irrigation. The growth of both plants was monitored and documented photographically to assess the effect of the beads on plant development.

3. Results

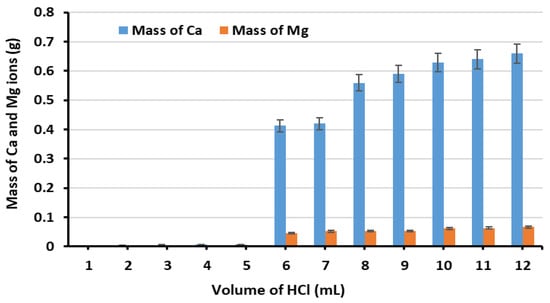

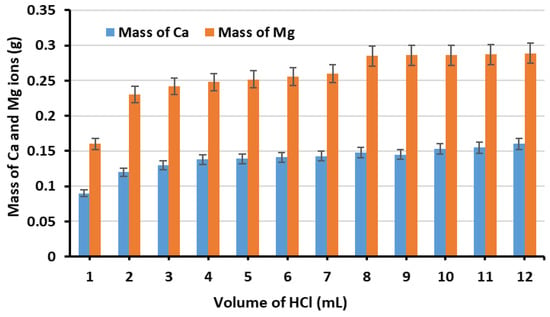

3.1. Ion Extraction Process

The results revealed that Ca ions extraction from GGBS increased with increasing HCl volume up to 10 mL, after which no significant increase was observed. It should be noted that while GGBS serves primarily as a calcium source and MgD as a magnesium source, both materials contain trace amounts of the complementary element. The Hach-Lange hardness test cuvettes used for analysis measure both Ca and Mg simultaneously, as reflected in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

The extraction of Ca and Mg ions from GGBS using various HCl volumes.

Figure 5.

The extraction of Mg and Ca ions from MgD using various HCl volumes.

Figure 4 illustrates the Ca and Mg concentrations obtained from GGBS with various HCl amounts. A notable sharp increase in Ca extraction was observed when HCl addition increased from 5 to 6 mL. At 5 mL HCl, the solution remained buffered with a relatively high pH; however, when 6 mL was added, the buffer capacity was overwhelmed, causing the pH to fall sharply and Ca to dissolve much more rapidly. This sharp transition occurred for Ca but not for Mg because Ca in GGBS exists in two phases: (1) an easily accessible Ca-bearing phase that releases a small amount of Ca during initial HCl additions, and (2) Ca within the glassy network, which releases a large amount of Ca once the solution’s buffer capacity is exceeded. Based on these results, 10 mL of HCl was established as the optimal volume for Ca extraction from GGBS.

Similarly, Figure 5 shows that Mg and Ca extraction from MgD increased with increasing HCl addition. However, additions exceeding 8 mL of HCl did not produce any significant improvement. Therefore, 8 mL of HCl was used for subsequent Mg extraction experiments.

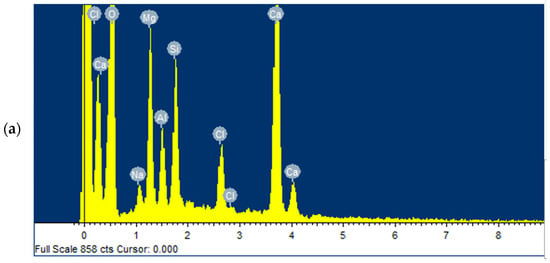

A key advantage of the extraction process is that it prevents the transfer of toxic heavy metals typically present in by-products, which is a crucial safety consideration. This was confirmed by EDX analysis of the adsorbent before treatment, which showed no toxic materials or heavy metals.

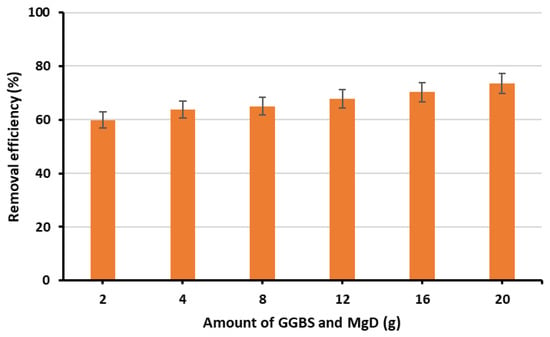

3.2. Optimisation of GGBS and MgD Loading Percentage

To determine the optimal ion loading conditions, various amounts of GGBS and MgD (2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 g) were evaluated. The experimental process involved twelve flasks containing 100 mL of DW, with six containing GGBS and six containing MgD in increasing quantities (2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 g). HCl was then added based on the optimal volumes determined in Section 3.1: 10 mL to each flask with GGBS and 8 mL to each flask containing MgD. The flasks were agitated for 3 h at 200 rpm at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C) and filtered using Whatman Grade 5 filter paper.

Following filtration, 15 mL of each GGBS solution was combined with 15 mL of the corresponding MgD solution (containing equivalent waste amounts) in six separate flasks. The pH of these mixed solutions was adjusted to 12 using NaOH solution, followed by agitation for 3 h at 200 rpm at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). The resulting solutions were then used to manufacture the adsorbent beads, which were subsequently tested for phosphate removal efficiency at a dose of 0.5 g, pH of 7, agitation speed of 200 rpm and contact time of 2 h. The results showed that the optimal loading was achieved with 20 g of each waste material. It should be noted that increasing the amounts of GGBS or MgD beyond 20 g was not feasible because the solution extraction became too viscous, forming a solid layer at the bottom of the flask. Figure 6 illustrates the removal efficiencies for beads manufactured across different loading rates.

Figure 6.

The effects of GGBS and MgD amounts on phosphate removal efficiency.

3.3. Batch Adsorption Performance

All batch experiments were repeated three times to ensure reliability and minimise experimental error.

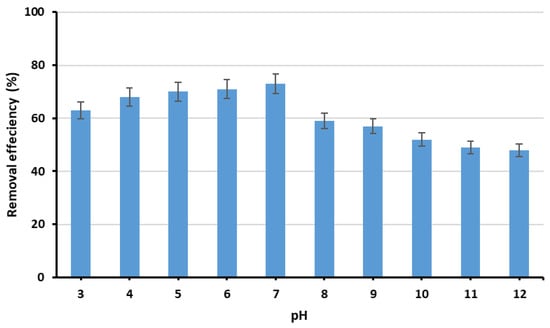

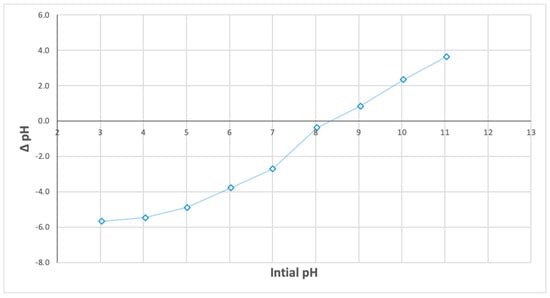

3.3.1. Effect of the Initial pH

The effect of initial pH on phosphate removal efficiency was examined using various initial pH values (3 to 12). Experiments were performed in 250 mL flasks containing 50 mL of phosphate stock solution (initial concentration of 10 mg/L), with 0.5 g of Ca-Mg-SA beads, agitated for 2 h at 200 rpm. The results revealed that phosphate removal efficiency increased from 63% to 73% as pH increased from 3 to 7, then declined to 59% at pH 8, as illustrated in Figure 7. This can be attributed to the fact that, at pH values from 3 to 7, phosphate exists predominantly as H2PO4− and HPO42−, which are attracted by Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions on the adsorbent surface. In alkaline solutions, OH− ions compete with phosphate ions for available active sites on the adsorbent, which inhibits the adsorption process [21]. The point-of-zero-charge (pHpzc) of the new adsorbent was measured using the ∆pH/solid addition method. This involved measuring the initial and final pH of the solution during the adsorption process. It was found that at a pH value of 8, ΔpH = 0, indicating that the surface charge on the surface of the adsorbent is zero (pHpzc), as depicted in Figure 8. Similar findings have been demonstrated by Santos et al. [22]. At pH values below the pHpzc, the adsorbent possesses a positive charge, which is favourable for anions (such as phosphate), while at pH values of the solution above this point, the adsorbent has a negative charge, which is favourable for cations. This explains why the removal efficiency in neutral and acidic conditions was higher than in alkaline environments [13].

Figure 7.

Removal efficiency with different pH values.

Figure 8.

Point of zero charge (pHpzc).

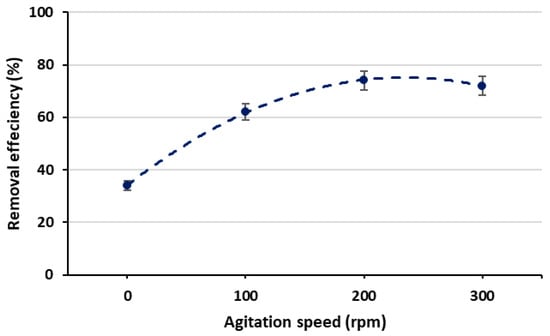

3.3.2. Effect of Agitation Speed

The relationship between phosphate removal efficiency and agitation speed was examined at agitation speed values of 0, 100, 200 and 300 rpm, maintaining a constant initial phosphate concentration of 10 mg/L, pH of 7 and contact time of 2 h. The findings revealed that the minimum removal (34%) was achieved at 0 rpm, while the highest removal efficiency (74%) was obtained when the agitation speed was increased to 200 rpm, as shown in Figure 9. This observation can be explained by the fact that increasing the agitation speed enhanced contact between the adsorbent and the adsorbate (phosphate).

Figure 9.

Removal efficiency with different agitation speeds.

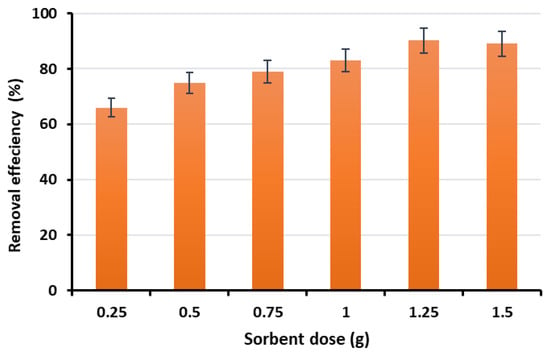

3.3.3. Effect of Adsorbent Dose

Phosphate removal efficiency was evaluated as a function of adsorbent dosage by testing various amounts of Ca-Mg-SA beads (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25 and 1.5 g) in 50 mL phosphate solution (10 mg/L, pH 7) with a 2-h contact time. The results showed that removal efficiency increased with increasing bead dosage from 0.25 to 1.25 g, as shown in Figure 10. However, increasing the dose beyond 1.25 g did not yield a significant improvement in removal efficiency, indicating that this dosage provided sufficient active sites for the available phosphate ions. Consequently, 1.25 g/50 mL was selected as the optimal dosage for subsequent experiments.

Figure 10.

The removal efficiency at different adsorbent doses.

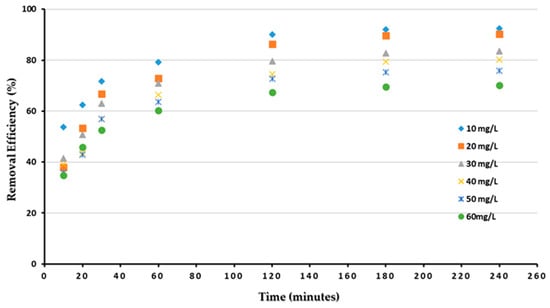

3.3.4. Effect of Contact Time

The kinetics of phosphate adsorption were investigated by varying contact time (0–240 min) at different initial phosphate concentrations (10–60 mg/L) while maintaining the other operational parameters constant (pH 7, adsorbent dose 1.25 g, agitation speed 200 rpm). Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between phosphate removal and initial phosphate concentrations. The adsorption process exhibited biphasic kinetics: a rapid initial phase during the first 60 min, followed by a slower phase until equilibrium. This behaviour can be attributed to the progressive occupation of available active sites on the adsorbent surface. Additionally, it was observed that 120 min were adequate to achieve the highest phosphate adsorption (equilibrium state). Regarding phosphate concentration, removal efficiency decreased from 90% to 67% as concentration increased from 10 to 60 mg/L. This inverse relationship between initial concentration and removal efficiency can be attributed to the limited number of available active sites, which become saturated at higher phosphate concentrations.

Figure 11.

The removal efficiency at various times and initial phosphate concentrations.

3.4. Characterisation of the Adsorbent

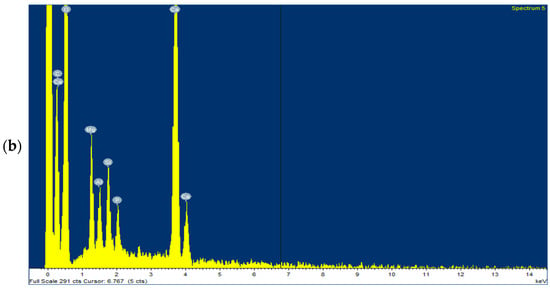

The fresh beads were subjected to EDX analysis to investigate the immobilisation of key ions onto sodium alginate and to confirm the presence of phosphate on the adsorbent after adsorption. Figure 12a,b show the ions present on the beads, including Ca2+ and Mg2+, before and after treatment, respectively, confirming that the adsorbent successfully adsorbed phosphate.

Figure 12.

The EDX test for Ca-Mg-SA beads (a) before treatment and (b) after treatment.

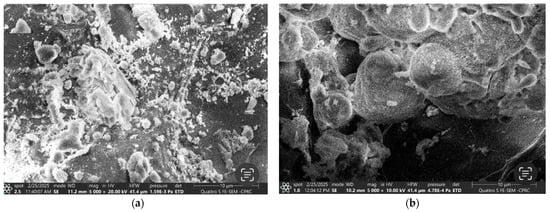

The SEM images in Figure 13a,b reveal significant differences in surface morphology before and after phosphate adsorption. The pre-adsorption images (Figure 13a) show a highly porous surface with notable roughness and fractures, characteristics that provide numerous active sites for phosphate binding. These structural features enhance the adsorption capacity by increasing the effective surface area available for ion exchange and chemical interactions.

Figure 13.

The SEM for Ca-Mg-SA beads (a) before treatment and (b) after treatment.

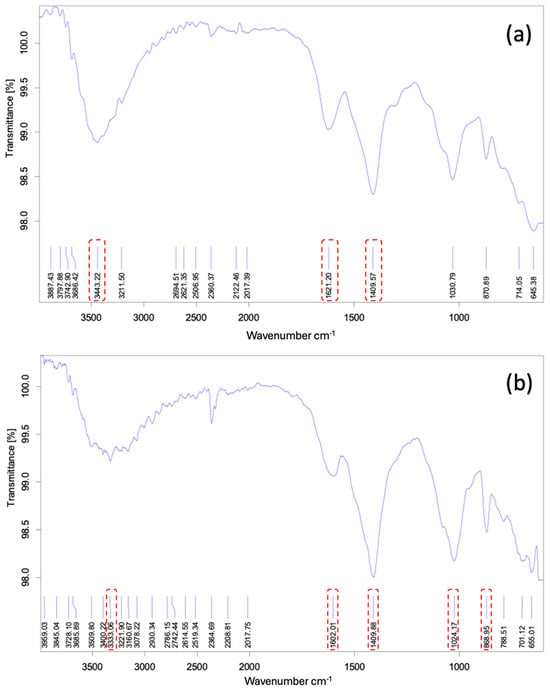

The FTIR test was performed to identify the available functional groups on the surface of beads that are responsible for phosphate uptake. Figure 14a,b depict the FTIR spectrum of Ca-Mg-SA beads before and after phosphate adsorption, respectively. The figures show a range of wavenumbers between (600–4000 cm−1) and noticeable displacements of transmittance bands. The distinct peak at 3443 cm−1 before treatment represents -OH vibration that is found in alginate and water molecules. However, the spectrum of beads after treatment revealed weaker bonds as the peak is slightly shifted to 3333.06 cm−1 due to the replacement of -OH with phosphate after the adsorption process [23].The band at 1409 cm−1 refers to symmetric carboxylate vibration COO- while the shifting of the peak from a wavenumber of 1621.2 cm−1 to 1602 cm−1 after adsorption with a change in intensity can be explained by the replacement of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions in beads by phosphate after phosphate uptake [24]. Moreover, the presence of peaks at 1024.17 and 868 cm−1 in the Ca-Mg-SA beads spectrum after treatment confirms that the phosphate was successfully adsorbed by the adsorbent, as the vibrations at 850–1050 cm−1 represent the P-O-C stretch [25].

Figure 14.

The FTIR test for Ca-Mg-SA beads (a) before treatment and (b) after treatment. Red rectangles indicate key spectral changes confirming phosphate uptake.

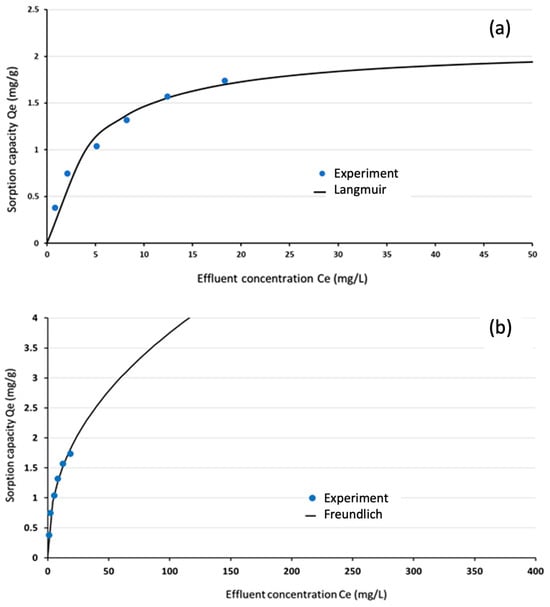

3.5. Equilibrium Isotherm Analysis

The experimental data for phosphate adsorption onto Ca-Mg-SA beads were analysed using both the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm models. Statistical parameters—specifically the coefficient of determination (R2) and the sum of squared errors (SSE)—were calculated to assess model fit quality. These constants were determined using the non-linear regression capabilities of the “Solver” function in Microsoft Excel 365, with results presented in Table 2. As illustrated in Figure 15, the experimental data demonstrated good agreement with both isotherm models, indicating that the adsorption process could be effectively described by either framework. Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of the maximum adsorption capacity qmax obtained in this study against values reported in the literature for different adsorbents, contextualising the performance of the developed material.

Table 2.

Constant values of the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms.

Figure 15.

(a) Langmuir isotherms, (b) Freundlich isotherm.

Table 3.

Comparison between the obtained q max from this study and the literature.

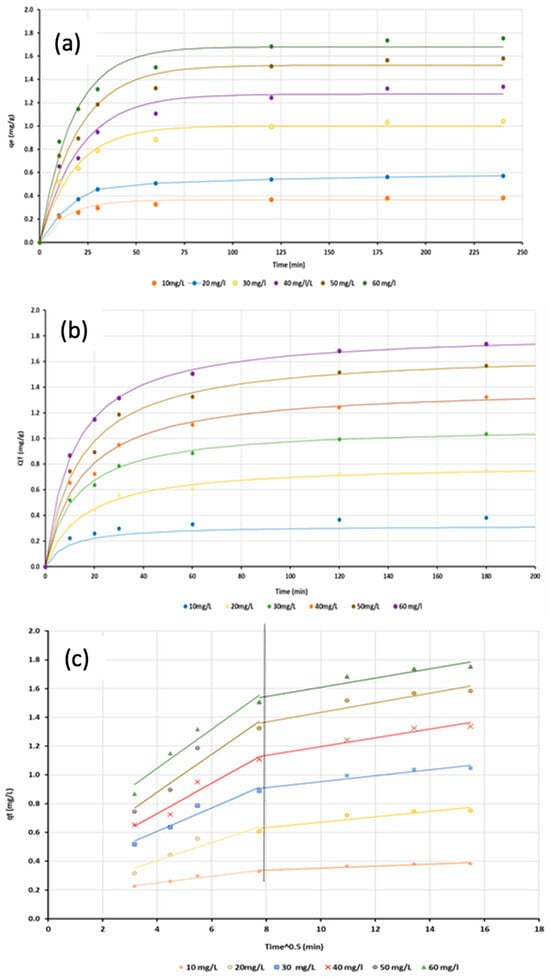

3.6. Adsorption Kinetics

Phosphate adsorption using Ca-Mg-SA beads was analysed using kinetic models at various values of initial phosphate concentrations. The kinetic data were fitted using non-linear regression in Microsoft Excel 365 while keeping the same operational conditions that were obtained from batch studies. Table 4 shows the constants of the used kinetic models, the sum of squared error (SSE) and the coefficient of determination (R2). Figure 16a–c depict the representation of experimental data with these models. Table 4 revealed that the adsorption process fitted well with the pseudo-second-order model, as evidenced by the highest R2 value and the lowest SSE value. Additionally, the experimental values of adsorbed phosphate (qe) were close to the theoretical values, which is further evidence of the model’s applicability. These findings suggest that chemisorption, involving chemical bonding between phosphate ions and active sites on the adsorbent surface, constitutes the primary adsorption mechanism. However, kinetic analysis alone is insufficient to identify the forces involved in the adsorption process; therefore, the intra-particle diffusion model was additionally applied.

Table 4.

The values of the kinetic parameters.

Figure 16.

The data representation of kinetics models: (a) Pseudo first order, (b) Pseudo second order and (c) Intra-particle diffusion.

The intra-particle diffusion model describes the mass transfer mechanism in the adsorption process and it can be represented by plotting the adsorbed amounts of pollutants () with t0.5. When the plot intercepts at zero, diffusion is the rate-controlling mechanism. As shown in Figure 16c, the non-zero intercepts across all concentration levels indicate that diffusion is not the sole rate-controlling mechanism and that additional mechanisms are involved in phosphate uptake by Ca-Mg-SA beads.

3.7. Mechanisms of Adsorption

The adsorption of phosphate on the Ca-Mg-SA beads occurs through three mechanisms: electrostatic attraction, ion exchange and surface complexation. Phosphate ions (PO43−) are negatively charged. EDX analysis of the adsorbent before phosphate uptake confirmed the immobilization of calcium and magnesium ions on sodium alginate, with these positively charged ions evident in the spectrum. Additionally, the point-of-zero-charge analysis proved that the adsorbent surface carries a positive charge below pH 8 and a negative charge above pH 8, respectively, which enables the Ca-Mg SA beads to attract the phosphate ions, resulting in electrostatic attraction. The FTIR analysis showed a wavenumber of 1621.2 cm−1 in the spectrum before treatment, corresponds to the carboxyl group COO− present in sodium alginate. However, the shifting of this band to 1602 cm−1 can be explained by the replacement of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions in beads by phosphate after phosphate uptake (ion exchange) [24]. Furthermore, the presence of the peaks at 1024.17 and 868.9 cm−1 in the Ca-Mg-SA beads spectrum after treatment refers to the formation of Ca–O–P and Mg–O–P linkages as the Ca and Mg ions bind to the phosphate particles, forming inner sphere complexes (surface complexation) [34]. It can be noted that phosphate adsorption on Ca-Mg-SA beads occurred both physically (electrostatic attraction) and chemically (through ion exchange and surface complexation).

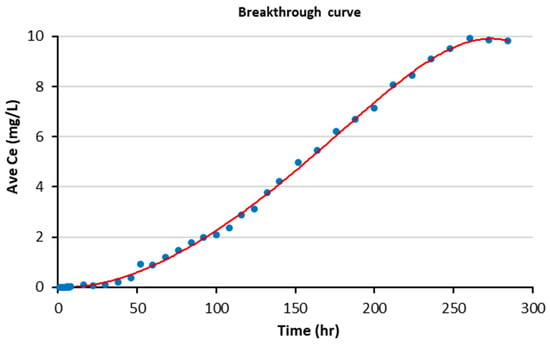

3.8. Column Experiments

The breakthrough curve was employed to demonstrate the behaviour and efficiency of the continuous flow experiment by plotting the effluent phosphate concentration against treatment time, as shown in Figure 17. It can be observed that the effluent phosphate concentration was zero for the first few hours, then began to increase gradually with time until the adsorbent was fully saturated and the phosphate concentration reached 9.92 mg/L after 10.8 days (260 h).

Figure 17.

The breakthrough curve for column experiments.

Additionally, the total accumulated phosphate was calculated by determining the area under the curve, multiplying it by the flow rate, and then dividing by the mass of adsorbent used, as follows:

qt = 94,037 (mg min/L) × 0.0015 (L/min)/179.2 g

qt = 0.82 mg P/g

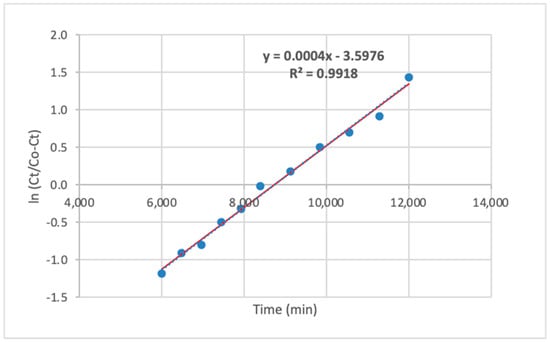

Furthermore, the Yoon and Nelson model was applied in its linear form. Only breakthrough curve data with a high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.99) were used for model fitting to ensure validity, as shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

The linear formula of the Yoon and Nelson model.

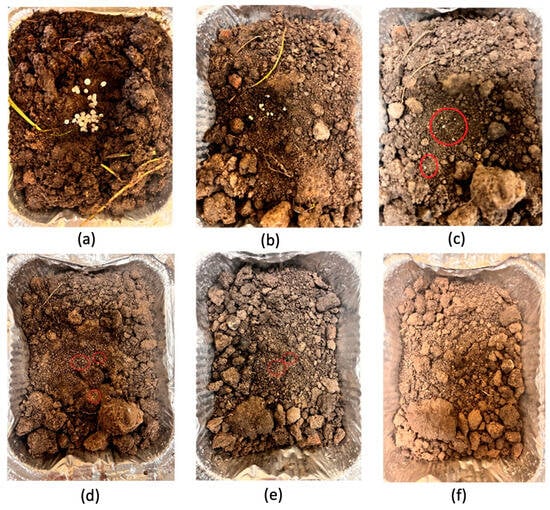

3.9. Biodegradability of Adsorbent

The biodegradability of Ca-Mg-SA beads was systematically monitored under ambient environmental conditions simulating natural soil processes. It was observed that after two weeks, the bead size had decreased by half. After one month, the bead diameters had reduced to approximately one quarter of their original size. Subsequently, they continued to diminish gradually until complete biodegradation occurred after 75 days, as documented in Figure 19. This degradation timeline demonstrates the environmental sustainability of the developed adsorbent, offering significant advantages for practical applications where end-of-life disposal is an important consideration.

Figure 19.

The biodegradability stages of Ca-Mg-SA beads at (a) day 1, (b) day 15, (c) day 30, (d) day 45, (e) day 60, (f) day 75.

3.10. Recycling the Adsorbent as a Soil Fertiliser

The reuse of the used adsorbent after phosphate uptake for soil fertilisation was investigated due to the presence of essential elements and nutrients that could enhance the plants’ germination process. Plant growth was monitored and photographically documented for four weeks. A gradual enhancement in the size of the plant fertilized with phosphate-saturated Ca-Mg-SA beads was observed. This can be attributed to the plant absorbing available nutrients from the beads (phosphate, calcium and magnesium), which promoted its growth. Similar findings have been demonstrated by Wang et al. [35]. Figure 20 illustrates the impact of adding utilised beads to plants for fertilisation.

Figure 20.

The fertilisation effect of the depleted beads on the growth of plants.

The recycling of Ca-Mg-SA beads after phosphate uptake represents an excellent dual-function approach for both water remediation and plant growth.

3.11. Comparison with Previous Studies

Numerous researchers have investigated phosphate removal from water and wastewater to mitigate its detrimental environmental and economic impacts. Various materials (natural, commercial and industrial by-products) have been explored as adsorbents with different preparation conditions and methodologies. For example, Han et al. [36] fabricated a novel, cost-effective adsorbent for phosphate removal from natural calcium-rich clay, which is abundant and affordable. First, a reaction between the clay and sodium silicate formed a silicate, which was then calcined. The experimental results showed that a high adsorption capacity of 372.57 mg/g was achieved with an initial phosphate concentration of 200 mg/L, an adsorbent dose of 4 g/L and a pH range of 4–12. Although the adsorbent had a high removal capacity, it has several limitations, including the depletion of natural resources, the need for additional chemicals and the need to operate at high temperatures due to the calcination process.

Commercial adsorbents have also been evaluated for phosphate removal. Delgadillo-Velasco et al. [37] examined two commercial products: Catalytic Carbon (coconut shell activated carbon (85%) with an iron catalytic coating (FeO(OH) 15%)) and Ferrolox (patented granular iron hydroxide (70–85%)), which were supplied by Watch Water Mexico Company. The results revealed removal capacities of 1.88 mg/g for the former and 76.04 mg/g for the latter when the initial phosphate concentration, pH and temperature were 500 mg/L, 7 and 30 °C, respectively. Despite their effectiveness, these commercial adsorbents present considerable drawbacks, including high procurement costs and environmental consequences associated with their manufacturing processes.

Industrial by-products offer a more sustainable alternative by promoting waste recycling and reducing environmental pollution. Ragheb [38] utilised two industrial by-products, fly ash (produced from the combustion of coal in power plants) and iron slag (generated from the blast furnace in iron production), to remove phosphate from wastewater. The obtained phosphate removal efficiency was 96.9% at a pH of 7 for the former and 96.15% at a pH of 5 for the latter. However, using these materials in their raw form presents challenges: potential transfer of harmful elements from industrial waste to water bodies and difficulties in solid-liquid separation due to fine particulate matter. These limitations highlight the advantage of extracting only the beneficial ions for immobilisation on suitable carriers such as sand or sodium alginate.

Sodium alginate is a natural, affordable, non-toxic and biodegradable polymer that is extracted from brown algae and has gained prominence in various industries, including food, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals [39]. In water treatment applications, Mittal et al. [23] recycled aluminium dross due to its high aluminium content and encapsulated it in sodium alginate to fabricate an adsorbent to remove phosphate from aqueous solution. The adsorbent removed 96.86% of phosphate from an initial concentration of 10 mg/L in 70 min. Although the adsorbent was highly efficient in removing phosphate, the preparation process required high temperatures (100 °C) and the industrial waste material was used directly in the encapsulation process rather than extracting the useful ions only. Similarly, Han et al. [40] blended polyvinyl alcohol with Mg-Al-sodium alginate to enhance its ability to eliminate phosphate, reaching equilibrium within 12 h with 99.2% removal efficiency. The procedures for preparing Mg and Al ions included calcination at 573 K (about 300 °C) for 24 h in an electric muffle furnace, resulting in significant energy consumption and environmental impact.

The current study addresses these limitations by developing an innovative, effective, sustainable and eco-friendly adsorbent. This is achieved through recycling industrial by-products (GGBS and MgD), extracting only the useful ions (Ca2+ and Mg2+) and immobilising them on sodium alginate, a natural and biodegradable polymer. The proposed methodology delivers multiple environmental and economic advantages. It transforms waste disposal liabilities into valuable resources while minimising landfill maintenance costs. Additionally, the extraction process enhances safety by excluding toxic materials commonly present in by-products. Operating at significantly lower processing temperatures (maximum 70 °C) with minimal chemical inputs substantially reduces manufacturing costs, energy consumption, and environmental pollution compared to conventional adsorbent production. Under optimised conditions (pH 7, 2-h contact time, 200 rpm agitation speed, 10 mg/L initial concentration), the Ca-Mg-SA beads achieved 90.2% phosphate removal efficiency with a capacity of 1.75 mg P/g. Moreover, complete biodegradation within 75 days addresses the critical challenge of waste accumulation generated by non-degradable, high-performance adsorbents.

While some commercial or natural adsorbents may exhibit higher removal efficiencies, they typically present significant drawbacks. For instance, chitosan preparation requires excessive chemicals across multiple stages and activated carbon manufacturing demands high temperatures and numerous chemicals [41]. Removal capacity alone should not be the sole criterion for adsorbent evaluation; environmental impact, cost-effectiveness and end-of-life disposal must also be considered. Consequently, the adsorbent developed in this study offers a balanced solution benefiting both environmental sustainability and industrial practicality, representing a significant advancement in eco-friendly water treatment technology.

4. Conclusions

The current study successfully developed a green, sustainable adsorbent for phosphate removal from water by utilising industrial by-products. Through systematic investigation, calcium ions from GGBS and magnesium ions from MgD were efficiently extracted, followed by their immobilisation on sodium alginate, resulting in an effective adsorbent material. The prepared adsorbent achieved 90.2% phosphate removal efficiency with a maximum adsorption capacity of 1.75 mg P/g in batch experiments under an initial pH of 7, an agitation speed of 200 rpm, a contact time of 120 min and a bead dosage of 1.25 g/50 mL, while the packed bed experiments showed a removal capacity of 0.82 mg P/g.

The adsorption mechanisms were thoroughly characterised through FTIR analysis, which showed bonds and shifts corresponding to ion exchange and surface complexation in addition to electrostatic attraction. Furthermore, kinetic results showed that the adsorption process follows pseudo-second-order kinetics, confirming chemical adsorption. This understanding provides valuable insights for process optimisation and scale-up considerations.

A particularly noteworthy attribute of this adsorbent is its complete biodegradation in soil within 75 days, addressing end-of-life disposal concerns. This provides a clear environmental advantage in addition to the possibility of recycling it as a plant fertiliser.

The methodology developed in this study, utilising industrial waste materials and low-temperature processing, represents a significant advancement in sustainable water treatment technology. This approach not only reduces waste management costs but also minimises the environmental footprint of the manufacturing process. The successful development of this adsorbent demonstrates the feasibility of converting industrial by-products into valuable water treatment materials, offering a dual benefit: efficient phosphate removal from water and sustainable utilisation of industrial waste.

The current work faced limitations, including the challenge of obtaining smaller bead sizes using practical, feasible methods. Therefore, future research should focus on examining the efficiency of smaller bead sizes and on further enhancing sustainability by utilising fewer chemicals and replacing oven drying with solar drying, especially in countries with high solar irradiation. This modification would further reduce energy consumption and environmental impact. Additional investigations should focus on evaluating Ca-Mg-SA beads performance in removing other water pollutants. Furthermore, comprehensive economic analysis and life cycle assessment would provide valuable insights for potential commercialisation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; methodology, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; validation, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; investigation, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; resources, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; data curation, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; writing—review and editing, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A.; supervision, R.A., M.A., I.C., M.S. and J.A.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saifuddin, M.; Bae, J.; Kim, K.S. Role of Fe, Na and Al in Fe-Zeolite-A for adsorption and desorption of phosphate from aqueous solution. Water Res. 2019, 158, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagalou, I.; Papastergiadou, E.; Leonardos, I. Long term changes in the eutrophication process in a shallow Mediterranean lake ecosystem of W. Greece: Response after the reduction of external load. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 87, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Tanaka, M. Impacts of pollution on coastal and marine ecosystems including coastal and marine fisheries and approach for management: A review and synthesis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 48, 624–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanassra, I.W.; Mckay, G.; Kochkodan, V.; Atieh, M.A.; Al-Ansari, T. A state of the art review on phosphate removal from water by biochars. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 409, 128211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Pasarín, M. Phosphate Adsorption onto Laterite and Laterite Waste from a Leaching Process. Master’s Thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, K.S.; Ewadh, H.M.; Muhsin, A.A.; Zubaidi, S.L.; Kot, P.; Muradov, M.; Aljefery, M.; Al-Khaddar, R. Phosphate removal from water using bottom ash: Adsorption performance, coexisting anions and modelling studies. Water Sci. Technol. 2021, 83, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzeyadi, A. An Experimental Investigation Into the Efficiency of Filter Materials for Phosphate Removal from Wastewater. Ph.D. Thesis, Liverpool John Moores University (United Kingdom), Liverpool, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Al Tahmazi, T. Characteristics and Mechanisms of Phosphorus Removal by Dewatered Water Treatment Sludges and the Recovery. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alwash, R. Treatment of Highly Polluted Water with Phosphate Using BAPPP-Nanoparticles. Master’s Thesis, University of Technology Baghdad, Baghdad, Iraq, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Jiang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, K. Phosphate removal performance and mechanism of zirconium-doped magnetic gasification slag. Arab. J. Chem. 2025, 18, 106079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Gao, M.; Huang, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of magnesium-modified steel slag and its adsorption performance for simultaneous removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malektaj, H.; Drozdov, A.D.; deClaville Christiansen, J. Mechanical properties of alginate hydrogels cross-linked with multivalent cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Ren, G.; Zhao, R.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, F.; Ma, X. Efficient low-concentration phosphate removal from sub-healthy surface water by adsorbent prepared based on functional complementary strategy. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, M.F.; Faisal, A.A. Calcium/iron-layered double hydroxides-sodium alginate for removal of tetracycline antibiotic from aqueous solution. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 63, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheju, M.; Miulescu, A. Sorption equilibrium of hexavalent chromium on granular activated carbon. Chem. Bull. Politech. Univ. 2007, 52, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.-S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.-C.; Tseng, R.-L.; Juang, R.-S. Comparisons of porous and adsorption properties of carbons activated by steam and KOH. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 283, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellner, B.M.; Hua, G.; Ahiablame, L.M. Fixed bed column evaluation of phosphate adsorption and recovery from aqueous solutions using recycled steel byproducts. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 233, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, F.B.; Mayer, B.K. Fixed-bed column study of phosphate adsorption using immobilized phosphate-binding protein. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z. Fabrication of ceramsite adsorbent from industrial wastes for the removal of phosphorus from aqueous solutions. J. Chem. 2020, 2020, 8036961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.F.; Arim, A.L.; Lopes, D.V.; Gando-Ferreira, L.M.; Quina, M.J. Recovery of phosphate from aqueous solutions using calcined eggshell as an eco-friendly adsorbent. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 238, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, Y.; Srivastava, P.; Tripathy, B.C.; Dhal, N.K.; Martinez, F.; Kumar, N.; Yadav, A.K. Aluminium dross waste utilization for phosphate removal and recovery from aqueous environment: Operational feasibility development. Chemosphere 2024, 349, 140649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmood, Z.; Nasir, S.; Jamil, N.; Sheikh, A.; Akram, A. Adsorption studies of phosphate ions on alginate-calcium carbonate composite beads. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Oktiani, R.; Ragadhita, R. How to read and interpret FTIR spectroscope of organic material. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 4, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; He, Z.; Mahmood, Q.; Liu, D.; Yang, X.; Islam, E. Phosphate removal from solution using steel slag through magnetic separation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 152, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Kong, H. Simultaneous removal of ammonium and phosphate by zeolite synthesized from fly ash as influenced by salt treatment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 304, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Z.; Li, L.; Yao, X.; Rudolph, V.; Haghseresht, F. Phosphate removal from wastewater using red mud. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 158, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Kwon, H.; Jeon, H.; Koopman, B. A new recycling material for removing phosphorus from water. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajima, T.; Haga, M.; Kuzawa, K.; Ishimoto, H.; Tamada, O.; Ito, K.; Nishiyama, T.; Downs, R.T.; Rakovan, J.F. Zeolite synthesis from paper sludge ash at low temperature (90 °C) with addition of diatomite. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 132, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, I.A.; Viswanathan, N. Development of multivalent metal ions imprinted chitosan biocomposites for phosphate sorption. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 104, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Tang, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Ding, X. Using recycled concrete as an adsorbent to remove phosphate from polluted water. J. Environ. Qual. 2019, 48, 1489–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Mahmood, Q. Adsorptive removal of phosphate from aqueous media by peat. Desalination 2010, 259, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, X.; Ye, X.; Niu, X.; Lin, Z.; Fu, M.; Zhou, S. Adsorption recovery of phosphate from waste streams by Ca/Mg-biochar synthesis from marble waste, calcium-rich sepiolite and bagasse. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 288, 125638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhuo, G.; Xue, D.; Zhu, G.; Wang, C.-Y. Sustainable Phosphate Recovery Using Novel Ca–Mg Bimetallic Modified Biogas Residue-Based Biochar. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Guo, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, W. Cost-effective and eco-friendly superadsorbent derived from natural calcium-rich clay for ultra-efficient phosphate removal in diverse waters. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 297, 121516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo-Velasco, L.; Hernández-Montoya, V.; Rangel-Vázquez, N.A.; Cervantes, F.J.; Montes-Morán, M.A.; del Rosario Moreno-Virgen, M. Screening of commercial sorbents for the removal of phosphates from water and modeling by molecular simulation. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 262, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, S.M. Phosphate removal from aqueous solution using slag and fly ash. HBRC J. 2013, 9, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X. Preparation and controlled degradation of oxidized sodium alginate hydrogel. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.-U.; Lee, C.-G.; Park, J.-A.; Kang, J.-K.; Lee, I.; Kim, S.-B. Immobilization of layered double hydroxide into polyvinyl alcohol/alginate hydrogel beads for phosphate removal. Environ. Eng. Res. 2012, 17, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmamı, H.; Amor, I.B.; Amor, A.B.; Zeghoud, S.; Ahmed, S.; Alhamad, A.A. Chitosan, its derivatives, sources, preparation methods, and applications: A review. J. Turk. Chem. Soc. Sect. A Chem. 2024, 11, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).