Abstract

Objectives: To investigate the profile of Th1- and Th2-type cytokines in response to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) antigens and to correlate this immune signature with clinical relapses in Multiple Sclerosis (MS). Specifically, we aimed to evaluate the cellular and humoral immune response following stimulation with a pool of lytic and latent EBV proteins. Methods: We employed ELISpot and ELISA to quantify Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), Interleukin-18 (IL-18), Interleukin-10 (IL-10), and the B-cell activation marker soluble CD23 (sCD23). Measurements were performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from MS patients and controls following stimulation with EBV peptide antigens. Results: MS patients exhibited significantly higher levels of all tested cytokines compared to controls. A statistically significant positive correlation was noted between IL-10 and sCD23 levels (p < 0.03), with significant correlations also found between IL-10 and IFN-γ (r = −0.56) and between IFN-γ and IL-18 (p < 0.02), a finding that warrants cautious interpretation. Crucially, both IL-10 and sCD23 levels strongly correlated with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score (p = 0.0003 and p = 0.0001, respectively). Conclusions: Our findings suggest a chronic, dysregulated immune response to EBV antigens in MS patients, characterized by the co-activation of inflammatory Th1 pathways and robust B-cell activation. These results support a pathogenetic model where the EBV-specific immune response, perpetuated by infected B-cells, may directly contribute to the immunopathological processes driving central nervous system (CNS) damage and clinical relapses.

1. Introduction

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory and demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) characterized by focal lesions of demyelination, axonal damage, and progressive neurological disability. The disease affects approximately 2.8 million people worldwide, with onset typically occurring in young adults between 20 and 40 years of age. While its etiology has long been recognized as multifactorial, involving complex interactions between genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, compelling epidemiological and molecular evidence has now established the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) not merely as one among several risk factors, but as a necessary prerequisite for MS development. Landmark longitudinal studies, particularly the seminal work by Bjornevik and colleagues in 2022, have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of MS etiology. Through analysis of more than 10 million U.S. military personnel over a 20-year period, these investigators demonstrated that the risk of developing MS is exceedingly low in EBV-negative individuals (hazard ratio < 0.01) and that infection with the virus almost invariably precedes the clinical onset of MS [1]. Critically, no other infectious agent showed such a consistent and specific association. This has catalyzed a paradigm shift in MS research: the question is no longer if EBV is involved, but how this ubiquitous herpesvirus—which infects more than 90% of the adult population worldwide—triggers a specific autoimmune attack on the CNS in genetically susceptible individuals [2].

1.1. Molecular Mimicry: The Bridge Between Viral Infection and Autoimmunity

The concept of molecular mimicry provides the most compelling mechanistic explanation for how a viral infection can break immune tolerance and initiate autoimmunity. In this model, structural or sequence similarity between viral epitopes and self-antigens leads to the activation of cross-reactive T-cells and B-cells that, once primed against the pathogen, inadvertently recognize and attack host tissues. In the context of MS, the molecular mimicry hypothesis has been substantiated by work demonstrating structural homology between EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) and the CNS glial cell adhesion molecule (GlialCAM), as well as myelin basic protein (MBP) [3,4,5].The mechanistic link has been further solidified by groundbreaking studies identifying specific T-cell and B-cell clones in MS patients that demonstrate precise cross-reactivity. Lanz and colleagues identified clonally expanded B-cells in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of MS patients producing antibodies that recognize both EBNA1 and GlialCAM, providing direct molecular evidence of the cross-reactive immune response [4]. More recently, Schneider-Hohendorf et al. demonstrated that MS patients harbor a broader anti-EBV T-cell receptor repertoire compared to healthy EBV-seropositive controls, and that this repertoire is modulated by disease-modifying therapies, further implicating EBV-specific immunity in disease pathogenesis [6].

1.2. EBV-Infected B-Cells: Viral Reservoirs and Antigen-Presenting Accomplices

Beyond molecular mimicry, the role of EBV-infected B-cells themselves has emerged as central to MS pathogenesis. EBV establishes lifelong latency primarily in memory B-cells, creating a persistent viral reservoir. These infected B-cells can traffic to the CNS and function as highly efficient antigen-presenting cells (APCs), potentially presenting both viral and cross-reactive self-antigens to T-cells within the inflamed CNS milieu. This mechanism provides a continuous source of antigenic stimulation that perpetuates chronic inflammation [7,8]. The profound clinical efficacy of B-cell depleting therapies—particularly anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies such as ocrelizumab and rituximab—in reducing relapse rates and MRI activity strongly supports this central pathogenic role of B-cells in MS [9].

1.3. Study Rationale

While these mechanisms provide a convincing conceptual framework linking EBV to MS pathogenesis, the specific cytokine environment that facilitates and perpetuates this pathological process remains incompletely characterized. Understanding the functional immune signature associated with EBV in MS patients—particularly during active disease—is crucial for identifying therapeutic targets and developing biomarkers of disease activity. This study aims to provide a functional immunological snapshot of this environment by systematically examining the EBV-specific cytokine response in MS patients during clinical relapses, with particular focus on both Th1-mediated inflammation and B-cell activation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

We performed a retrospective analysis of anonymized data from a previously established institutional database. This database was established at the D. Cotugno Hospital, a reference center for infectious and immunological diseases in Naples, Italy, with the primary goal of collecting longitudinal clinical data and biological samples from patients with neuroinflammatory disorders to facilitate translational research. The repository, assembled between 2005 and 2010, contains data from 106 patients and has served as the basis for our group’s previous investigations into the immunopathology of MS [10,11,12]. For the present study, we selected a specific cohort of thirty EBV-seropositive patients (16 female, 14 male; mean age 34.2 ± 8.7 years) from this database who met the strict inclusion criterion of being sampled during an active clinical relapse. The diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) was made according to the Poser criteria, which were the diagnostic standard at the time of data collection. A clinical relapse was defined as the appearance of new or worsening neurological symptoms lasting for at least 24 h, as confirmed by a board-certified neurologist, within two weeks prior to sampling. The Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score was determined by a neurologist at the time of sample collection for each MS patient using standardized assessment protocols [11,12]. It is important to note that because of these specific selection criteria, this cohort differs from the patient groups described in our previously cited works [10,11,12]. The control group consisted of 20 age- and sex-matched EBV-seropositive subjects diagnosed with other non-inflammatory neurological diseases (OND), primarily comprising individuals with tension-type headaches or idiopathic peripheral neuropathy, to control for potential stress associated with neurological consultations. This group was chosen to account for the psychological and physiological stress that may accompany neurological evaluation, which can influence immune parameters. While a low level of localized inflammation cannot be entirely ruled out in certain OND conditions, these disorders are fundamentally distinct from MS in that they are not characterized by the systemic, T-cell and B-cell mediated autoimmune activation that defines MS pathogenesis, making them a suitable comparison group for isolating MS-specific immune signatures.

2.2. Ethical Statement

All original study procedures for data and sample collection were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki on anonymized data. At the time of enrollment, all participants provided written informed consent for the use of their anonymized biological samples and clinical data in future research. For the present retrospective study, which utilized only pre-existing, fully anonymized, and aggregated data, specific re-consent was not required in accordance with the applicable national regulations established by the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) and the provisions of the Italian Data Protection Authority. According to these guidelines, for retrospective observational studies conducted on anonymized clinical data, neither prior approval from the ethics committee nor informed patient consent is necessary. This interpretation was formally confirmed by the Ethics Committee of the “Nationally Relevant and Highly Specialized Hospitals—A. Cardarelli/Santobono—Pausilipon,” which issued a final opinion with reference to Protocol No. 00000926 dated 11 January 2022.

2.3. PBMC Isolation and In Vitro Stimulation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from heparinized venous blood using Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) density gradient centrifugation. After washing, cells were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. PBMCs were plated at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well. Cells were stimulated with a commercial pool of overlapping 15-mer peptides derived from key latent (EBNA1, LMP2A) and lytic (BRLF1, BZLF1) EBV proteins (Nanogen, Torino, Italy) at a final concentration of 1 µg/mL for each peptide. Unstimulated cells served as a negative control, and phytohemagglutinin (PHA, 5 µg/mL) was used as a positive control. Cells were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

2.4. Cytokine Quantification

Following the 24 h stimulation, cell culture supernatants were collected and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. The frequency of IFN-γ and IL-10 secreting cells was enumerated using a commercial ELISpot PRO kit (Mabtech AB, Nacka, Sweden) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Spots were counted using an automated ELISpot reader. The concentrations of soluble CD23 (sCD23) and IL-18 in the collected culture supernatants were quantified using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Bio-Organon, Rome, Italy) following the manufacturer’s instructions. All samples were run in duplicate.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Group comparisons were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). For group comparisons across the four measured cytokines, a Bonferroni correction was applied, and a p-value of <0.0125 (0.05/4) was considered statistically significant. For the exploratory correlation analyses, a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant, but these results should be interpreted with caution due to the number of comparisons.

3. Results

3.1. Heightened Cytokine Response to EBV Antigens in MS Patients

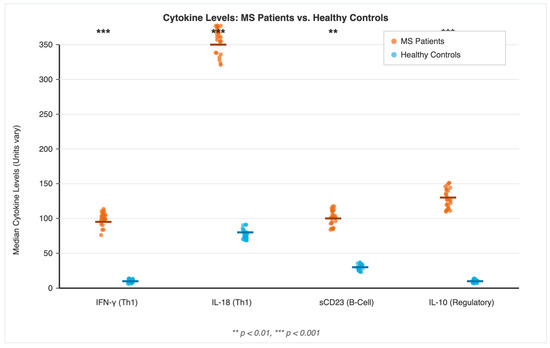

Upon stimulation of PBMCs with a pool of EBV antigens, patients with MS exhibited a significantly heightened and broad-based cytokine response compared to the control group. As visualized in Figure 1, the median levels of all four measured cytokines were markedly elevated in MS patients. The pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines IFN-γ (MS: 98.5 units/106 cells vs. controls: 15.2 units/106 cells; p < 0.001) and IL-18 (MS: 342.7 pg/mL vs. controls: 78.3 pg/mL; p < 0.001), the B-cell. activation marker sCD23 (MS: 102.4 ng/mL vs. controls: 32.1 ng/mL; p < 0.001), and the regulatory cytokine IL-10 (MS: 135.8 units/106 cells vs. controls: 12.4 units/106 cells; p < 0.001) were all produced at significantly higher levels (p < 0.0125 for all comparisons after Bonferroni correction) in the MS cohort, indicating a state of profound immune hyper-responsiveness to the virus during relapse.

Figure 1.

Dysregulated Cytokine Response to EBV Antigens in Multiple Sclerosis. Levels of Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), Interleukin-18 (IL-18), soluble CD23 (sCD23), and Interleukin-10 (IL-10) were measured in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 30 Multiple Sclerosis patients (orange) and 20 healthy controls (blue) following 24 h stimulation with a pool of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) antigens. Each point represents an individual subject, and the horizontal line indicates the median value for each group. Statistical significance between groups was determined using the Mann–Whitney U test. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

3.2. B-Cell Activation and Regulatory Cytokines Strongly Correlate with Clinical Disability

To determine if this immune signature was clinically relevant, we correlated cytokine levels with the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score in MS patients. As shown in Table 1, we found a strong and highly significant positive correlation between the EDSS score and levels of the B-cell activation marker sCD23 (r = 0.72, p = 0.0001), suggesting that the magnitude of B-cell activation directly relates to disease severity. Similarly, levels of the regulatory cytokine IL-10 also showed a strong positive correlation with disability (r = 0.65, p = 0.0003). These findings directly link the magnitude of both B-cell and regulatory immune responses to the clinical severity of the disease relapse, supporting the clinical relevance of these immunological parameters.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Statistical Correlations in MS Patients.

3.3. An Imbalanced Cytokine Network in MS

Further analysis of the relationships between the cytokines revealed a dysregulated network (Table 1). A significant positive correlation was observed between the two key Th1 inflammatory cytokines, IFN-γ and IL-18 (r = 0.51, p = 0.02), suggesting a synergistic feed-forward loop that may amplify and sustain the inflammatory cascade. In contrast, a significant negative correlation was found between the regulatory IL-10 and the inflammatory IFN-γ (r = −0.56, p < 0.01). This inverse relationship suggests an ongoing but ultimately insufficient compensatory attempt by the regulatory arm of the immune system to counteract the powerful Th1-driven inflammation characteristic of active MS relapses.

4. Discussion

The most striking result of this study is the marked elevation of all tested cytokines in MS patients during active relapse, providing a functional snapshot of the profound immune hyper-responsiveness to EBV antigens during periods of clinical disease activity. When interpreted in light of recent mechanistic discoveries, our data support an integrated model of MS pathogenesis in which viral triggers, molecular mimicry, and persistent B-cell dysregulation converge to drive CNS. inflammation and tissue damage.

4.1. Th1 Inflammation and Molecular Mimicry

The significant increase in IFN-γ, a canonical Th1 cytokine and key mediator of cell-mediated immunity, is entirely consistent with the molecular mimicry hypothesis. In this model, IFN-γ represents the signature cytokine produced by pathogenic, cross-reactive CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells that initially recognize EBV antigens such as EBNA1 but subsequently attack structurally similar CNS self-antigens including GlialCAM and myelin proteins [4,5]. Studies by Lanz and colleagues have substantiated this mechanism by identifying specific T-cell and B-cell clones that demonstrate this precise cross-reactivity between EBNA1 and GlialCAM, thereby solidifying the mechanistic link between the virus and the autoimmune lesion [4]. More recently, Schneider-Hohendorf et al. demonstrated that MS patients harbor a qualitatively and quantitatively different anti-EBV T-cell receptor repertoire compared to healthy controls, and that this repertoire is modulated by disease-modifying therapies, further implicating EBV-specific T-cell immunity in ongoing disease pathogenesis [6]. The concurrent elevation of IL-18 is particularly noteworthy. IL-18, a member of the IL-1 cytokine family, is known to synergistically amplify IFN-γ production by Th1 cells and natural killer (NK) cells, especially in the presence of IL-12. The strong positive correlation we observed between IL-18 and IFN-γ (r = 0.51, p = 0.02) suggests the existence of a powerful feed-forward amplification loop that could drive and sustain Th1-mediated inflammation in the CNS microenvironment. This cytokine cascade likely contributes to the recruitment and activation of additional inflammatory cells, the upregulation of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells, and the perpetuation of tissue damage characteristic of MS lesions [13].

4.2. B-Cell Dysregulation: Beyond Antibody Production

Crucially, our study highlights the profound B-cell dysregulation at the heart of MS pathogenesis. The elevated levels of sCD23, a direct marker of B-cell activation that is shed from the surface of activated B-lymphocytes, strongly correlated with neurological disability as measured by EDSS scores (r = 0.72, p = 0.0001). This finding reinforces the central pathogenic 8 di 13 15/10/25, 07:24 Cytokine Signatures Induced by Epstein–Barr Virus Antigens in Multiple Sclerosis role of EBV-infected B-cells, which function not only as a persistent viral reservoir but also as highly efficient APCs capable of presenting both viral and cross-reactive self-antigens to T-cells within the inflamed CNS [7,8,14]. The clinical importance of B-cells in MS has been definitively established by the remarkable efficacy of B-cell depleting therapies. Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies such as ocrelizumab, rituximab, and ofatumumab have demonstrated unprecedented reductions in relapse rates, disability progression, and MRI activity in both relapsing and progressive forms of MS [9,15]. Interestingly, these therapies work despite having minimal effects on antibody levels, suggesting that the primary pathogenic role of B-cells in MS relates to their function as APCs and cytokine producers rather than antibody-secreting cells. Our data showing robust B-cell activation in response to EBV antigens during relapses provides a functional immunological basis for understanding why B-cell depletion is so effective.

4.3. The Paradox of Regulatory Responses

The interpretation of the cytokine correlations requires careful consideration, particularly the complex relationship between pro-inflammatory and regulatory mediators. The negative correlation between IL-10 and IFN-γ (r = −0.56, p < 0.01) is particularly intriguing and warrants nuanced interpretation. Rather than representing a simple causal relationship where IL-10 directly suppresses IFN-γ, this pattern more likely reflects a compensatory regulatory mechanism. As Th1 inflammation (represented by IFN-γ) escalates during a relapse, the immune system appears to mount a counter-regulatory response through increased IL-10 production, likely from regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and regulatory B-cells (Bregs), in an attempt to restore homeostasis and limit tissue damage. However, the fact that high levels of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines coexist, and that IL-10 levels themselves positively correlate with higher disability scores (r = 0.65, p = 0.0003), suggests that this regulatory attempt is ultimately insufficient to quell the pathogenic inflammation during an active relapse. This paradox—robust regulatory responses that nonetheless fail to prevent disease activity—has been observed in multiple autoimmune conditions and may reflect either quantitative insufficiency of regulatory cells, qualitative dysfunction of their suppressive mechanisms, or resistance of effector cells to regulatory signals in the inflamed tissue microenvironment [16,17].

4.4. Broader Mechanisms Linking Viral Infection to Autoimmunity

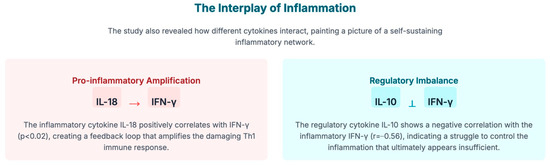

While molecular mimicry provides the most direct mechanistic link between EBV and MS, several complementary mechanisms may contribute to breaking immune tolerance and initiating CNS autoimmunity [18,19] (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

This diagram illustrates two key mechanisms describing how cytokines (the immune system’s signaling molecules) interact to create a self-sustaining inflammatory network in the pathology of Multiple Sclerosis (MS), as triggered by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV).

- Bystander Activation: Local inflammation and tissue damage resulting from the immune response to EBV can lead to the release of sequestered CNS self-antigens and the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules on APCs. This inflammatory milieu can non-specifically activate autoreactive T-cells that are normally held in check by peripheral tolerance mechanisms.

- Epitope Spreading: Chronic inflammation caused by the primary immune response against EBV antigens can lead to secondary tissue damage that exposes previously cryptic self-antigens. This results in diversification and amplification of the autoimmune response to include multiple myelin and neuronal targets, a phenomenon well-documented in MS and demonstrated by the presence of antibodies and T-cells reactive against numerous CNS antigens in established disease [20].

- Chronic Antigenic Stimulation: The lifelong latent infection established by EBV in B-cells provides continuous antigenic stimulation. Periodic viral reactivation and the constant presence of latently infected B-cells may foster a state of chronic immune activation that, over time, erodes tolerance mechanisms and facilitates the emergence or expansion of autoreactive lymphocyte clones.

4.5. Clinical and Therapeutic Implications

Our findings have several important clinical implications. First, the strong correlation between sCD23 and EDSS suggests that markers of B-cell activation could serve as biomarkers for disease activity and severity. Second, the demonstration of heightened cytokine responses to EBV antigens during relapses provides a mechanistic rationale for antiviral approaches targeting EBV as a potential therapeutic strategy in MS. While trials of traditional antiviral agents have been disappointing, novel approaches targeting EBV-infected B-cells specifically—such as adoptive transfer of EBV-specific cytotoxic T-cells or therapeutic vaccines—warrant investigation [21,22].

4.6. Study Limitations

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, the retrospective nature and relatively modest sample size (n = 30 MS patients, n = 20 controls) limit statistical power, and our findings, particularly the exploratory correlation analyses, should be interpreted with appropriate caution and require validation in larger, independent cohorts. Second, while our control group of patients with other non-inflammatory neurological diseases accounted for the potential confounding effects of stress associated with neurological evaluation, an ideal comparison would include asymptomatic,

EBV-seropositive healthy individuals to better isolate MS-specific immune signatures. The inclusion of such controls would strengthen future investigations [21,22].

Third, the diagnostic criteria used in this study (Poser criteria) were the standard at the time of data collection (2005–2010) but have since been superseded by the revised McDonald criteria, which incorporate MRI findings for earlier diagnosis. The Poser criteria relied more heavily on clinical evidence of dissemination in time and space, meaning that our cohort likely represents patients with more clinically established disease. This difference may actually strengthen the observed associations between cytokine responses and clinical disability, but it may limit generalizability to patients diagnosis earlier in their disease course using contemporary criteria. Fourth, this study provides cross-sectional immunological snapshot during active relapses. Longitudinal studies examining how these cytokine signatures evolve over time—comparing relapse to remission periods, and examining changes with disease-modifying therapies—would provide crucial insights into disease dynamics and treatment responses. Finally, while we measured cytokine levels in peripheral blood, MS is fundamentally a CNS disease, and the immune responses in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid may differ qualitatively or quantitatively from those observed peripherally. Future studies correlating peripheral and CNS immune signatures would be valuable.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, while acknowledging the limitations inherent in our retrospective analysis, this study demonstrates that lymphocytes from MS patients experiencing clinical relapses mount an aberrant and markedly heightened response to EBV antigens, characterized by the simultaneous activation of intense Th1 inflammation, robust B-cell activation, and paradoxically elevated but insufficient regulatory responses. These findings lend strong support to the hypothesis that EBV plays a critical, potentially causal role in the immunopathology of MS relapses. The striking correlation between the B-cell activation marker sCD23 and neurological disability (EDSS) highlights B-cell activation as a potentially crucial immunological link between viral infection and CNS autoimmunity—a concept strongly supported by the remarkable clinical efficacy of B-cell depleting therapies. When our functional immunological data are integrated with recent molecular evidence of cross-reactivity between EBV and CNS antigens, they provide a coherent pathogenetic hypothesis. Further investigation on immune responses will be essential to better understand the role of these signatures and to explore the potential of novel therapeutic strategies targeting the virus itself.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P., C.S., P.B.C. and O.P.; Methodology, A.P. and O.P.; Software, P.B.; Validation, P.B.; Investigation, A.D., A.D.S., C.S. and P.B.C.; Resources, A.D.; Visualization, A.D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nationally Relevant and Highly Specialized Hospitals—A. Cardarelli/Santobono—Pausilipon (protocol code No. 00000926) on 11 January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Since the retrospective nature of the study, informed consent was obtained at the time of enrollment from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Oreste Perrella for his invaluable assistance during his life as a researcher at Cotugno Hospital This paper was an original idea of O. Perrella and all data were retrospectively evaluated after his death.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedström, A.K. Risk factors for multiple sclerosis in the context of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1212676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafini, B.; Rosicarelli, B.; Franciotta, D.; Magliozzi, R.; Reynolds, R.; Cinque, P.; Andreoni, L.; Trivedi, P.; Salvetti, M.; Faggioni, A.; et al. Dysregulated Epstein-Barr virus infection in the multiple sclerosis brain. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 2899–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.-S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.-S.; Bartley, C.M.; et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Or, A.; Pender, M.P.; Khanna, R.; Steinman, L.; Hartung, H.-P.; Maniar, T.; Croze, E.; Aftab, B.T.; Giovannoni, G.; Joshi, M.A. Epstein-Barr virus in multiple sclerosis: Theory and emerging immunotherapies. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider-Hohendorf, T.; Wünsch, C.; Falk, S.; Raposo, C.; Rubelt, F.; Mirebrahim, H.; Asgharian, H.; Schlecht, U.; Mattox, D.; Zhou, W.; et al. Broader anti-EBV TCR repertoire in multiple sclerosis: Disease specificity and treatment modulation. Brain 2025, 148, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, M.P.; Csurhes, P.A.; Burrows, J.M.; Burrows, S.R. Defective T-cell control of Epstein-Barr virus infection in multiple sclerosis. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2017, 6, e126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzartos, J.S.; Khan, G.; Vossenkamper, A.; Cruz-Sadaba, M.; Lonardi, S.; Sefia, E.; Meager, A.; Elia, A.; Middeldorp, J.; Clemens, M.; et al. Association of innate immune activation with latent Epstein-Barr virus in active MS lesions. Neurology 2012, 78, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, S.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.-P.; Hemmer, B.; Lublin, F.; Montalban, X.; Rammohan, K.W.; Selmaj, K.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Interferon Beta-1a in Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrella, O.; Sbreglia, C.; Perrella, M.; Spetrini, G.; Gorga, F.; Pezzella, M.; Perrella, A.; Atripaldi, L.; Carrieri, P. Interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Mode of immunomodulation in multiple sclerosis. Neurol. Res. 2006, 28, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, P.B.; Ladogana, P.; Di Spigna, G.; de Leva, M.F.; Petracca, M.; Montella, S.; Buonavolontà, L.; Florio, C.; Postiglione, L. Interleukin-10 and Interleukin-12 Modulation in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis on Therapy with Interferon-beta 1a. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2008, 30, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrieri, P.B.; Carbone, F.; Perna, F.; Bruzzese, D.; La Rocca, C.; Galgani, M.; Montella, S.; Petracca, M.; Florio, C.; Maniscalco, G.T.; et al. Longitudinal assessment of immuno-metabolic parameters in multiple sclerosis patients during treatment with glatiramer acetate. Metabolism 2015, 64, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallaur, A.P.; Lopes, J.; Oliveira, S.R.; Simão, A.N.C.; Reiche, E.M.V.; de Almeida, E.R.D.; Morimoto, H.K.; de Pereira, W.L.C.J.; Alfieri, D.F.; Borelli, S.D.; et al. Immune-inflammatory and oxidative and nitrosative stress biomarkers of depression symptoms in subjects with multiple sclerosis: Increased peripheral inflammation but less acute neuroinflammation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015, 53, 5191–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Patterson, K.R.; Bar-Or, A. Reassessing B cell contributions in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Hauser, S.L.; Kappos, L.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Comi, G.; de Seze, J.; Giovannoni, G.; Hartung, H.-P.; Hemmer, B.; et al. Ocrelizumab versus Placebo in Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Villar, M.; Hafler, D.A. Regulatory T cells in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2018, 19, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser, E.C.; Mauri, C. Regulatory B cells: Origin, phenotype, and function. Immunity 2015, 42, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smatti, M.K.; Cyprian, F.S.; Nasrallah, G.K.; Al Thani, A.A.; Almishal, R.O.; Yassine, H.M. Viruses and Autoimmunity: A Review on the Potential Interaction and Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses 2019, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M.; Restrepo-Jiménez, P.; Monsalve, D.M.; Pacheco, Y.; Acosta-Ampudia, Y.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Leung, P.S.C.; Ansari, A.A.; Gershwin, M.E.; Anaya, J.M. Molecular mimicry and autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 2018, 95, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuohy, V.K.; Yu, M.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Kinkel, R.P. Diversity and plasticity of self recognition during the development of multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, M.P.; Csurhes, P.A.; Smith, C.; Douglas, N.L.; Neller, M.A.; Matthews, K.K.; Beagley, L.; Rehan, S.; Crooks, P.; Hopkins, T.J.; et al. Epstein-Barr virus-specific T cell therapy for progressive multiple sclerosis. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e124714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldan, S.S.; Lieberman, P.M. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).