Detection of Outliers via Uncertain Knowledge and the IF–THEN Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

Novel Contributions of This Work

- We propose an enhanced decision criterion for outlier rules by requiring that at least three out of four fuzzy implications (Product, Łukasiewicz, , ) meet specific thresholds in Section 4.

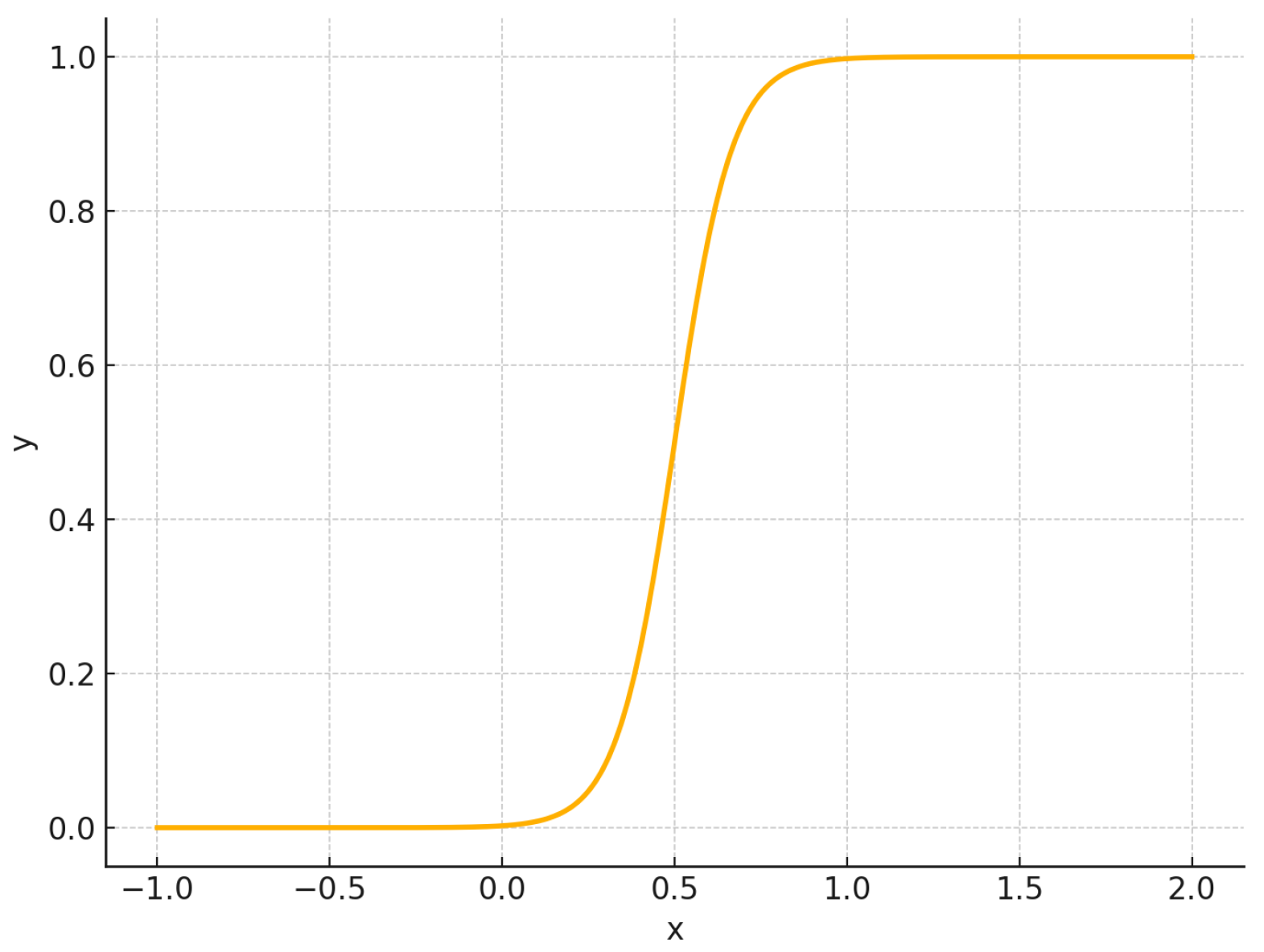

- The paper introduces and utilizes three distinct S-shaped functions to compute the degree of sufficient coverage, which were not included or described in earlier works.

- We provide an extended empirical evaluation, including a comparative analysis with the Local Outlier Factor (LOF) method under multiple parameter configurations, highlighting the strengths and limitations of both approaches in Section 5.

- The proposed method is validated on a large real-world dataset and the results were consulted with domain experts in the banking sector, strengthening the practical significance of our approach.

2. Literature Review

3. An Outlier in Terms of Fuzzy Rules

3.1. Clarification of Terminology

- Outlier rule: A fuzzy rule is considered an outlier rule if it satisfies the conditionswhere is the degree of outlierness, is a fixed threshold (typically 0.95), and C is the degree of sufficient coverage (e.g., ).

- Outlying object: An object is an outlying object if it activates at least one outlier rule , i.e., the fuzzy membership functions associated with the antecedent and consequent of both yield non-zero values for , and is marked as an outlier rule under the criteria above.

3.2. Generating of Fuzzy IF–THEN Rules

- Definition of linguistic variables: Each input and output attribute relevant to the problem is expressed as a linguistic variable (e.g., “season”, “income level”, “average response time”).

- Specification of fuzzy sets: For every linguistic variable, fuzzy sets are assigned (e.g., “low”, “medium”, “high”) along with their membership functions over the defined universe of discourse.

- Combinatorial generation of rules: The algorithm constructs candidate IF–THEN rules by combining each possible antecedent fuzzy set with each possible consequent fuzzy set across all variables. This step yields the complete setwhere K depends on the number of variables and fuzzy sets defined.

- Evaluation and selection: For each generated rule , the degree of truth T and degree of coverage C (as defined in Equations (3) and (4)) are computed. Rules satisfying the thresholds for outlierness (Equation (1)) are retained as outlier rules; the remaining rules are discarded.

4. Detecting Outliers in Graph Databases—An Implementational Example

- S1: Logistic-like functionwhere is the steepness, and is the midpoint.

- S2: Piecewise linear sigmoid

- S3: Quadratic S-shape

Example

- Number of days in a year: —represented by a triangular fuzzy set spring, supported over the interval [64, 218] (The authors consider a universe of discourse from 1 to 366 days because they intend to cover all days, including leap years) (Obviously, the spring starts on 21 March and ends on 22 June. However, in terms of fuzzy logic, by “spring” we rather understand “close to the spring season”, but we use “spring” for short),

- County per capita income: (in thousands)—represented by the fuzzy label middle county, supported on [19, 55]

- Median household income: (in thousands)—represented by the fuzzy label rich county, defined on [37, 65]

- Number of days to send complaint: —represented by the fuzzy label average time, defined on [2, 10]

- GDP of the state: W = [28, 16,209] (in millions)—represented by the fuzzy label very small amount, defined on [28, 126]

- Group category: F is a non-fuzzy attribute with 4 linguistic values: Older American, Servicemember, Older American and Servicemember, and none,

- 85. IF the complaint is submitted in the middle of spring AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household), THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint.

- 121. IF the complaint is submitted in early winter AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household) THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint.

- 137. IF the complaint is submitted in the middle of spring AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household), THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint.

- 1649. IF a complaint is submitted by an older American or a service member AND concerned about a state that has a very small amount (GDP), THEN the submitter comes from a rich county (median household).

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Other Fuzzy-Based Outlier Detection Methods

- Modified Fuzzy Clustering for Intrusion Detection [17]—based on clustering density deviations.

- Fuzzy Neural Networks for Cyber Anomaly Detection [20]—a hybrid method combining learning-based detection with fuzzy rule layers.

- Fuzzy Logic for Time Series Outliers [15]—a rule-less fuzzy method for detecting irregular points in temporal data.

- Explainable Unsupervised Anomaly Detection with Random Forest [29]—an unsupervised tree-based method that distinguishes real data from synthetically generated samples and provides local interpretability of outlier decisions.

5.2. Comparison with Machine Learning Techniques

5.3. Sensitivity to Parameters

- Fixed Threshold (see Definition 1): tested values in {0.90, 0.92, 0.95, 0.98}.

- Coverage threshold : tested values in {0.0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2}.

- Required Implications: two out of four, three out of four, four out of four implications.

6. Conclusions

- Effectiveness of Fuzzy Logic Application: The proposed IF–THEN method for detecting outliers based on fuzzy logic and IF–THEN rules proved effective in identifying anomalies in data, particularly those represented linguistically. This enables the detection of outliers that traditional numerical methods, such as LOF (Local Outlier Factor), fail to identify.

- Universality of the Approach: The new definition of outliers, grounded in fuzzy rules, demonstrated its universal applicability to both relational and non-relational datasets. This increases its potential utility in various fields, including finance, medicine, and security analysis.

- Importance of Expert Knowledge: The integration of expert knowledge through linguistic descriptions of data allowed for more precise identification of the unique characteristics of outlier objects. This approach emphasizes the importance of interpretability and expert validation, enhancing the credibility of the obtained results.

- Advantages Compared to LOF: A comparison between the results of the LOF method and the fuzzy logic-based approach showed that the IF–THEN method identifies outliers that would not be detected by analyses solely based on numerical data. This is particularly evident in the case of properties expressed in linguistic terms, such as “Older American” or “Average Time.”

- Potential for Integration with Other Methods: The fuzzy rule-based method can act as a complement to existing algorithms, such as LOF, enriching results by identifying additional outliers. This approach is particularly useful in the analysis of multifaceted datasets, where the diversity of features requires the application of different analytical techniques.

- Significance of Parameters and Their Interpretation: The introduction of parameters, such as the degree of coverage (C) and the degree of outlierness (), enables precise definition of the conditions for classifying objects as outliers. The selection of appropriate functions, such as S-shaped functions, significantly impacts the accuracy of outlier detection, as demonstrated in the experiments. We note that the fuzzy inference model employed S-shaped membership functions to represent continuous variables such as income, population, and resolution time. This type of function was selected for its smooth transition between linguistic categories, making it suitable for modeling gradual phenomena. As mentioned earlier in Section 3, preliminary experiments confirmed that S-shaped functions led to stable rule activation patterns and consistent outlier detection. Although a formal comparison with alternative shapes was not included, the results support their use as semantically meaningful and operationally effective. A comparative evaluation of different membership function types remains a valuable direction for future work.

- Practical Application and Validation: The outlier detection results were empirically verified and consulted with banking experts, confirming the method’s practical utility in real-world business scenarios.

- Impact of Dataset Structure: Experimental observations indicate that the proper definition and construction of fuzzy sets influence the effectiveness of outlier detection. Future research may focus on optimizing these parameters for specific applications.

7. Future Work

- Dynamic Optimization of Parameters: Future research could explore adaptive methods for selecting the key parameters of the fuzzy rules, such as the degree of coverage (C) and the degree of outlierness (). This could involve machine learning techniques to dynamically optimize these parameters based on the characteristics of the dataset, ensuring better performance across different domains and applications.

- Application to Real-Time Systems: The integration of the proposed method into real-time data processing systems presents a promising direction. Real-time anomaly detection is particularly relevant for domains such as cybersecurity, where timely identification of outliers (e.g., network intrusions) is critical. Implementing the method in a streaming data environment would require further optimization of computational efficiency.

- Extending to Heterogeneous Data: While the current study focuses on specific datasets, future work could evaluate the method’s applicability to more diverse and complex datasets, such as those combining numerical, categorical, textual, and temporal data. This would validate the method’s robustness in handling heterogeneous data structures.

- Integration with Other Outlier Detection Methods: To further enhance the detection of anomalies, future research could investigate the hybridization of the fuzzy logic-based approach with traditional numerical methods, such as Local Outlier Factor (LOF) or clustering algorithms. This integration could provide a more comprehensive outlier detection framework, leveraging the strengths of both numerical and linguistic representations.

- Domain-Specific Applications: The IF–THEN method could be customized and tested in domain-specific scenarios, such as the following:

- Healthcare: Detecting outliers in patient data to identify rare symptoms or unusual disease progression.

- Finance: Identifying fraudulent transactions or irregular patterns in banking datasets.

- IoT Systems: Recognizing anomalous behavior in sensor networks or smart devices.

- Exploration of Explainability: The linguistic nature of the fuzzy logic-based method inherently enhances interpretability. Future work could focus on improving the explainability of the results by developing tools or frameworks that visualize the fuzzy rules and their contributions to the identification of outliers, aiding decision-making by domain experts.

- Scalability and Performance: Expanding the IF–THEN method to accommodate large-scale datasets is another area for future work. This includes optimizing the computational complexity of the fuzzy rule evaluation process and investigating distributed or parallel processing techniques to improve scalability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawkins, D.M. Identification of Outliers; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Outlier Detection in Categorical, Text, and Mixed Attribute Data. In Outlier Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 249–272. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, G.O.; Zimek, A.; Sander, J. On the Evaluation of Outlier Rankings and Outlier Scores. In Proceedings of the KDD ’17 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Yu, P.S. Outlier detection for high dimensional data. In Proceedings of the ACM Sigmod Record, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 21–24 May 2001; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 30, pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Ng, R.T.; Sander, J. LOF: Identifying density-based local outliers. In Proceedings of the ACM Sigmod Record, Dallas, TX, USA, 15–18 May 2000; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 29, pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.; Chen, Z.; Fu, A.W.C.; Cheung, D.W. Enhancing Effectiveness of Outlier Detections for Low Density Patterns. In Knowledge and Information Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Knorr, E.M.; Ng, R.T.; Tucakov, V. Distance-based outliers: Algorithms and applications. VLDB J.—Int. J. Very Large Data Bases 2000, 8, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, M.M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J. Density-Based Clustering of Spatial Data with Noise. In Proceedings of the KDD ’01 Seventh ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 August 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Wu, Q.J.; Jermaine, C. Conditional Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the SIGMOD ’07 2007 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Beijing, China, 11–14 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bartczak, M.; Niewiadomski, A. Linguistic summaries of graph databases in customer relationship management (CRM). J. Appl. Comput. Sci. 2019, 27, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bartczak, M.; Kacprowicz, M. Podniesienie Poziomu Bezpieczeństwa Danych Bankowych Poprzez Wykrywanie Wyjątków; Zeszyty Naukowe Zbliżenia Cywilizacyjne, State Vocational University in Wloclawek: Włocławek, Poland, 2021. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Niewiadomski, A.; Kacprowicz, M.; Bartczak, M. Outliers Detection In Graph-Represented Databases Using Fuzzy Rules. In Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, PACIS 2021, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 12–14 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprowicz, M.; Bartczak, M.; Niewiadomski, A. Detection and recognition of outliers by the use of IF-THEN rules. In Proceedings of the 3rd Polish Conference on Artificial Intelligence, PP-RAI’2022, Gdynia, Poland, 25–27 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.F.; Liu, X.; Zhao, H.; Chen, X.C. Anomaly Detection of Complex Networks Based on Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set Ensemble. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2018, 35, 058901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; Kannan, K. Identifying outliers in fuzzy time series. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2011, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cateni, S.; Colla, V.; Vannucci, M. A fuzzy logic-based method for outliers detection. In Proceedings of the 25th Multi-Conference on Applied Informatics, Innsbruck, Austria, 12–14 February 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Harish, B.S.; Kumar, S.V.A. Anomaly based Intrusion Detection using Modified Fuzzy Clustering. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Batra, S. A novel ensembled technique for anomaly detection. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2019, 30, e3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaes, M.P.; Carvalho, L.F.; Lloret, J.; Proença, M.L.J. Long Short-Term Memory and Fuzzy Logic for Anomaly Detection and Mitigation in Software-Defined Network Environment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 83765–83781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungara, K.K.; Gopi, V.; Kumar, M.K. Detection of Cyber Anomaly Using Fuzzy Neural Networks. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 11, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Moniruzzaman, A.B.M.; Hossain, S.A. NoSQL Database: New Era of Databases for Big data Analytics—Classification, Characteristics and Comparison. Int. J. Database Theory Appl. 2013, 6. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/243963821_NoSQL_Database_New_Era_of_Databases_for_Big_data_Analytics_-_Classification_Characteristics_and_Comparison (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Bartczak, M.; Kacprowicz, M. Detekcja wyjątków metodami agregacji rozmytej w grafowych systemach CRM. In Wyzwania Gospodarcze, Polityczne i społEczne w Globalnej Gospodarce; State Academy of Applied Sciences in Włocławek: Włocławek, Poland, 2022. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kosko, B. Fuzziness vs. probability. Int. J. Gen. Syst. 1990, 17, 11–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, J.; Kaymak, U.; van den Bergh, W.M. Fuzzy classification using probability-based rule weighting. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 12–17 May 2002; pp. 991–996. [Google Scholar]

- Klir, G.J.; Yuan, B. Fuzzy Sets and Fuzzy Logic: Theory and Applications; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D.; Mendel, J.; Joo, J. Linguistic summarization using IF-THEN rules. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Fuzzy Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 July 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Complaint Database. Available online: https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/consumer-complaint-database (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Documentation for the Scikit-Learn Library. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.neighbors.LocalOutlierFactor.html (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, W. Explainable Unsupervised Anomaly Detection with Random Forest. Future Internet 2023, 15, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rule No. | Fuzzy Rules | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 85. | IF the complaint is submitted in the middle of spring AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household) THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint. | 0.94 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.96 | 0 | 0.96 | 0 |

| 121. | IF the complaint is submitted in early winter AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household) THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint. | 0.94 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.86 | 0 | 0.95 | 0 |

| 137. | IF the complaint is submitted in the middle of spring AND the submitter comes from a rich county (median household) THEN in an average time CFPB sends a complaint. | 0.90 | 0 | 0.97 | 0 | 0.86 | 0 | 0.96 | 0 |

| 1649. | IF a complaint is submitted by OlderAmerican, Service-member AND concerned about a state which has a very small amount (GDP) THEN the submitter comes from a rich county (median household). | 0.90 | 0 | 0.92 | 0 | 0.96 | 0 | 0.94 | 0 |

| Feature | IF–THEN Method | LOF Method |

|---|---|---|

| Handles linguistic attributes | Yes | No |

| Sensitivity to data structure | Low to Medium | High |

| Expert knowledge integration | Yes | No |

| Truely detected outliers | 32 | 0 to 6 |

| n_ Neighbors | Algorithm | Leaf\ _Size | Metric | p | Metric\ _Params | Contamination | Accuracy | F1 | Number of Objects Proposed to be Outliers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | auto | 30 | minkowski | 2 | None | auto | 3206 | ||

| 50 | auto | 100 | jaccard | 2 | None | auto | 0 | ||

| 20 | auto | 30 | correlation | 4 | None | 0.0012 | 33 | ||

| 20 | auto | 30 | correlation | 4 | None | 0.0004 | 11 | ||

| 20 | auto | 30 | correlation | 2 | None | 0.0004 | 11 | ||

| 20 | auto | 30 | correlation | 2 | None | 0.0003 | 9 | ||

| 20 | auto | 30 | correlation | 2 | None | 0.0002 | 6 |

| (a) LOF method | ||

| Predicted condition | ||

| Actual condition | Positive (PP) | Negative (PN) |

| Positive (P) | 6 | 45 |

| Negative (N) | 0 | 40,032 |

| accuracy = F1 = | ||

| (b) IF–THEN method | ||

| Predicted condition | ||

| Actual condition | Positive (PP) | Negative (PN) |

| Positive (P) | 32 | 19 |

| Negative (N) | 0 | 40,032 |

| accuracy = F1 = | ||

| Method | Linguistic Input Support | Interpretability | Outlying Objects Detected | Accuracy | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IF–THEN (ours) | Yes | High (explicit rules) | 32 | 99.95% | 0.7710 |

| Fuzzy clustering [17] | No | Low (centroid-based) | 19 | 99.92% | 0.5142 |

| Fuzzy neural network [20] | Partially | Medium (learned rules) | 27 | 99.91% | 0.5128 |

| Fuzzy time-series [15] | No | Medium | 22 | 99.88% | 0.3896 |

| Random Forest [29] | No | Low | 26 | 99.89% | 0.4155 |

| Method | Parameters | Number of Detected Outlying Objects | Ids Objects |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOF | n_neighbors = 20; algorithm = auto leaf_size = 30; metric = correlaction p = 2; metric\-params = None contamination = 0.0002; novelty = False _jobs = None | 6 |

689,889, 725,545, 725,546, 744,072, 1,038,302, 1,087,276 |

| IF–THEN method | Required Implications = 3 out of 4 | 32 |

28,939,

41,365,

41,683,

43,196, 44,358, 364,520, 372,521, 375,975, 377,404, 383,137, 389,866, 395,693, 550,401, 630,491, 659,478, 744,965, 755,635, 755,712, 760,146, 763,847, 773,246, 788,230, 792,773, 801,371, 801,691, 804,591, 805,340, 805,828, 819,496, 833,603, 948,708, 1,115,287 |

| Required Implications | Truely Detected Outliers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.90 | 0.1 | 3 of 4 | 28 |

| 0.95 | 0.1 | 3 out of 4 | 32 |

| 0.98 | 0.1 | 3 out of 4 | 3 |

| 0.95 | 0.1 | 2 out of 4 | 19 |

| 0.95 | 0.0 | 3 out of 4 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kacprowicz, M.; Niewiadomski, A. Detection of Outliers via Uncertain Knowledge and the IF–THEN Method. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312833

Kacprowicz M, Niewiadomski A. Detection of Outliers via Uncertain Knowledge and the IF–THEN Method. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312833

Chicago/Turabian StyleKacprowicz, Marcin, and Adam Niewiadomski. 2025. "Detection of Outliers via Uncertain Knowledge and the IF–THEN Method" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312833

APA StyleKacprowicz, M., & Niewiadomski, A. (2025). Detection of Outliers via Uncertain Knowledge and the IF–THEN Method. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12833. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312833