Featured Application

The extended GTST-MLD framework provides a structured approach for representing and analyzing complex non-physical systems shaped by human interaction, adaptation, and decision-making. While the present study applies the model to a teaching–learning context, the underlying logic of goal–function–success decomposition may hold potential conceptual relevance for other human-centered domains; however, these possibilities lie beyond the empirical scope of this single-course case study and are suggested only as directions for future conceptual exploration. By formalizing interdependencies among goals, functions, and enabling conditions, the framework can support the identification of systemic bottlenecks and can inform the design of context-sensitive adaptive strategies.

Abstract

Modeling complex non-physical systems is essential for understanding the interdependent dynamics of human-centered adaptive environments. This study extends the Goal Tree–Success Tree and Master Logic Diagram (GTST-MLD) framework to represent and analyze these systems beyond their traditional engineering applications. A mixed-methods approach, combining a systematic literature review, expert interviews, and survey-based validation, was employed to test the framework using the teaching–learning process in Higher Education (HE) as an illustrative case study. The results show how function-centered modeling within the GTST-MLD structure decomposes the complexity of the system and reveals pedagogical bottlenecks, providing a structured basis for designing adaptive strategies. Rather than measuring learning gains directly, the model offers a structured representation of the conceptual and methodological pathways that influence learner engagement, conceptual integration, and adaptability. Within this bounded context, this study demonstrates a reproducible GTST-MLD modeling procedure for non-physical systems, an auditable dependency structure, based on explicitly defined nodes and edges, and a coherent alignment between Threshold Concepts (TCs), Learning Outcomes (LOs), and methodological strategies. Together, these contributions offer a basis for diagnosing and optimizing complex non-physical systems and form a foundation for future empirical evaluation.

1. Introduction

Complex non-physical systems present unique challenges related to structure, adaptability, and emergent behavior. Unlike physical systems, which can often be decomposed into discrete and predictable elements, non-physical systems consist of interdependent and evolving components that respond dynamically to environmental and contextual conditions. Traditional modeling approaches frequently fail to capture these interconnections, underscoring the need for alternative methodologies capable of structuring, analyzing, and optimizing such complex environments [1,2,3].

The GTST-MLD framework, originally developed for reliability and risk assessment in engineering, has demonstrated robust analytical capabilities that can be extended to broader system domains [4]. Despite growing interest in modeling complex socio-technical processes, educational systems remain underrepresented within function-centered modeling research. HE environments constitute dynamic, non-physical systems that play a pivotal role in fostering social resilience, workforce adaptability, and informed decision-making amid global challenges such as climate change, migration, and economic inequality. Modeling educational processes through the GTST-MLD framework offers a structured analytical lens with which to examine human coordination and support transformative learning in complex adaptive contexts.

For the purposes of this study, the term ‘system’ refers specifically to the Project Engineering course at a single higher-education institution, which is treated as a bounded non-physical system for the application of the GTST-MLD framework. No claims are made regarding system-wide, program-level, or cross-institutional applicability beyond this context. Within this bounded scope, this study contributes to the literature by demonstrating how GTST-MLD can be instantiated in a human-centered non-physical system using a transparent and reproducible modeling procedure. This includes the formal decomposition of goals and functions, the integration of TCs derived through mixed-methods evidence, and the development of a complete and auditable model comprising a node dictionary and dependency matrix. By aligning functional pathways with concept-acquisition bottlenecks and methodological strategies, this study illustrates how function-centered modeling can clarify the structural logic of complex systems and support evidence-informed interventions aimed at improving performance and adaptability.

Many complex systems operate within open and evolving conditions in which multiple stakeholders interact under variable constraints [5]. These systems demand continuous adaptation to sustain performance and alignment with changing external environments [6]. However, due to their intangible and interconnected nature, conventional modeling methods often lack the capacity to structure analysis and guide decision-making effectively. The integration of function-centered modeling within the GTST-MLD framework offers a promising approach for decomposing complexity, identify critical dependencies, and enhance systemic performance over time [7,8,9].

Accordingly, this study applies the GTST-MLD framework to model an unstructured, non-physical system within the higher-education context. The framework is explored within a single course, used here as an illustrative example of a complex, open, non-physical system. Through a function-centered perspective, it demonstrates how GTST-MLD enables the systematic decomposition of interdependent processes. Rather than claiming broad generalizability, this study focuses on showing how the framework can be instantiated in this specific context to analyze interdependencies and structure a complex learning process.

2. Related Work

This section reviews prior research on function-centered modeling and the evolution of the GTST-MLD framework to establish the theoretical foundation for the present study. It first examines the principles of function-centered modeling of complex systems, then explores the integration of GTST-MLD with transformative change, and finally reviews its main applications across technical and human-centered domains.

2.1. Function-Centered Modeling of Complex Systems

The modeling of complex systems has become essential across disciplines such as engineering, systems science, and organizational studies, reflecting the increasing complexity of technological and institutional structures [2,9]. Traditional approaches, including process-centered and data-centered models, often fail to represent the dynamic and hierarchical behavior of such systems [10]. Function-centered approaches emerged to address this limitation by focusing on system functions and their interactions rather than solely on structural components. This paradigm enhances system understanding, fault diagnosis, and performance optimization, particularly in adaptive and safety-critical contexts [11].

Grounded in system dynamics [12,13] and early hierarchical theories [10], the function-centered approach evolved through hierarchical function analysis [2,14,15], enabling the decomposition of complex systems based on objectives and interactions. It integrates object-oriented and goal-centered perspectives, object-oriented modeling explores system dynamics through tools such as Dynamic Flow Diagrams (DFD) [16], whereas goal-centered methodologies, including Structured Analysis and Design Techniques (SADT) and Multilevel Flow Modeling (MFM), define functional requirements [14,17]. This integration enables the analysis of interactions among humans, software, and hardware while capturing emergent properties.

Building on this foundation, the approach allows complex systems to be decomposed into subsystems down to the component level [18,19]. According to [2], this analysis incorporates both static and dynamic hierarchies, spatial organization and temporal evolution, ensuring a holistic understanding of system behavior. However, decomposition remains subjective and depends on the observer’s intent and system knowledge. Extending this approach, recent studies have applied it to cyber-physical systems and Industry 4.0 [20,21], where interactions among hardware, software, and human operators are critical. Function-centered models enhance fault detection and adaptive control [22,23], although challenges persist regarding subjective decomposition and scalability. Integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning is increasingly proposed to automate functional analysis and improve scalability [24,25].

This functional decomposition logic underpins the GTST-MLD approach, providing a conceptual basis for exploring its adaptation beyond technical systems. By representing systems as hierarchies of goals, intermediate functions, and success conditions, GTST-MLD formalizes the relationship between what a system is expected to achieve and how those expectations are operationalized. Such hierarchical abstractions are consistent with the broader body of work on modeling complex systems, where structured representations are used to make interdependencies and feedback dynamics analytically tractable despite heterogeneity or partial qualitative behavior [24,26].

Although GTST-MLD has been applied predominantly to engineered systems, research conceptualizing HE institutions and school systems as Complex Adaptive Systems (CASs) demonstrates that multi-level, hierarchical modeling is theoretically compatible with social and institutional processes. For example, Ref. [27] analyze universities as CAS and show how institutional change and sustainability governance emerge from interactions across structures, actors, and policies. Similarly, Ref. [28] argue that sustainable school improvement requires attending to the non-linear, interconnected, multi-level system behavior characteristic of CAS. Although these studies do not employ GTST-MLD directly, they show that systems-oriented, hierarchical models can support structured analysis in human-centered domains.

2.2. Integrating GTST-MLD with Transformative Change

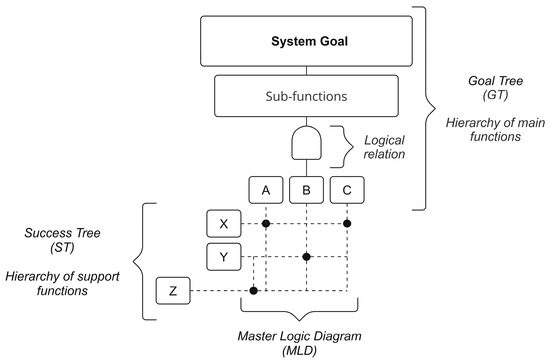

As an extension of function-centered modeling, the GTST-MLD framework represents a significant step toward capturing system complexity through hierarchical relationships between goals, sub-goals, and their logical dependencies, providing a detailed view of functionality and behavior [4]. Originally developed for engineering risk analysis, GTST-MLD merges functional and structural hierarchies to address the limitations of purely structural models, which often overlook emergent properties. Each element is represented by its function, with elementary components defined as non-functional primitives [29].

GTST modeling provides a hierarchical structure of system goals (Goal Tree, GT) and success conditions (Success Tree, ST) that together represent both objectives and the dependencies required for their achievement [2,15,30]. The addition of the Master Logic Diagram (MLD) simplifies dependencies within GT-ST relationships [31], representing links between main and support functions, as well as between primary and auxiliary elements [16,32]. This structure enhances failure detection and system visualization in environments with multiple interdependent subsystems [4,15]. As highlighted by Ref. [16], the fundamental idea behind the GTST modeling framework originated from risk analysis in nuclear power plants during the 1980s [33] and process control in industrial facilities [18,34]. Its capacity to visualize objectives, components, and interrelations has since positioned it as a powerful framework for functional decomposition.

Building on this CAS-oriented literature, the present study does not claim that GTST-MLD has already been validated as a solution for sector-wide educational reform, governance, or sustainability policymaking. Rather, it advances a more modest and clearly bounded claim: that the hierarchical logic of GTST-MLD is conceptually aligned with existing systems-based analyses of educational and organizational change and can therefore be explored as a modeling lens for a single HE course treated as a bounded non-physical system. In this sense, GTST-MLD is positioned as a methodological candidate whose potential in human-centered domains must be assessed incrementally and context-by-context, rather than assumed a priori.

At the same time, recent work at the intersection of AI, complex systems, and organizational adaptability reinforces the relevance of function-centered modeling for decision support in dynamic environments. Ref. [24] show how AI-enabled modeling frameworks can tame the complexity of expert models and improve decision-making in domains characterized by high uncertainty and multi-scale interactions. Ref. [26] argue that organizations navigating turbulent contexts require leadership approaches that explicitly engage with adaptive tension and emergent structures, a view that is grounded in complexity theory and emphasizes the need for tools that make interdependencies and feedback pathways visible to stakeholders. Taken together, these bodies of work indicate that function-centered and CAS-informed models constitute a plausible basis for structuring analysis in non-physical, human-centered systems, although their concrete applicability must be examined empirically in each specific context.

Against this backdrop, the present study should be understood as an exploratory methodological transfer: GTST-MLD is operationalized within the bounded context of a single Project Engineering course to model its teaching–learning process as a complex, adaptive system. The goal is not to offer a fully developed solution to sector-wide educational reform, but to test whether a function-centered GTST-MLD representation can clarify learning dependencies, identify potential bottlenecks, and provide a transparent, auditable structure that may, in future work, be scaled or adapted to broader educational and policy settings.

2.3. Applications of the GTST-MLD Framework

GTST-MLD has been extensively applied in aerospace, defense, and nuclear industries for reliability and risk management, where it maps system objectives and success paths to identify critical failure points [15]. In oil and gas operations, the MLD assists in preventing catastrophic events by analyzing functional dependencies [4], while in automotive engineering it improves the reliability of electronic control systems [32]. The framework’s graphical representation enhances fault prediction and mitigation, although it requires a comprehensive understanding of system goals and can become complex in highly interdependent systems [15].

Recent research integrates GTST-MLD with Fault Tree Analysis (FTA) and Event Tree Analysis (ETA) for enhanced failure-mode prediction [1]. Incorporation of AI and machine learning now supports automated failure path identification and real-time optimization [35]. Compared to other hierarchical models, such as functional or behavior-based hierarchies, GTST-MLD is more goal-oriented, emphasizing objectives over system states [32]. While traditionally focused on physical systems, emerging studies demonstrate their relevance to non-physical, human-centered domains [7]. In education, GTST-MLD can decompose institutional objectives, such as improving LOs or curriculum design, into actionable sub-goals, integrating conditions like resources and collaboration.

Compared with Soft Systems Methodology (SSM) and Agent-Based Modeling (ABM), GTST-MLD provides a clearer hierarchical representation of functional dependencies, aiding systemic goal analysis even in complex adaptive environments [36]. While SSM focuses on stakeholder perspectives and ABM on agent interactions, GTST-MLD clarifies hierarchical relationships between goals and dependencies, thus complementing both approaches. Nevertheless, its reliance on hierarchical decomposition may limit applicability in non-linear systems where feedback and emergent dynamics dominate [16]. Continued integration with adaptive and data-driven methods, such as AI-enhanced MLDs, can extend its scalability and applicability.

Overall, the literature highlights a growing convergence between function-centered modeling, AI integration, and adaptive learning paradigms. These frameworks collectively offer structured tools for analyzing complex systems and have increasingly informed decision-making in dynamic, non-physical domains such as education and organizational governance. In the present study, this theoretical foundation is used not to claim sector-wide solutions, but to motivate an exploratory application of GTST-MLD within a single higher-education course, treated as a bounded educational system. Building upon this foundation, the next section outlines the methodological design adopted to operationalize GTST-MLD in this specific context, demonstrating how the framework can be used to model the adaptive teaching–learning processes of the course as a complex, human-centered system.

2.4. Rationale for Selecting GTST-MLD over Existing Pedagogical Modeling Frameworks

Although several established frameworks guide pedagogical design, including the Theory of Change (ToC), Learning Pathway Maps, and logic-model approaches based on the Logical Framework Analysis (LFA), these models typically provide high-level causal narratives rather than formal, functionally structured representations of internal system dependencies. The ToC approach has become influential in educational innovation and social-impact settings due to its capacity to articulate long-term goals and backward-map assumptions [37,38]. However, ToC remains largely descriptive, relying on conceptual pathways that do not encode the hierarchical, multi-layered functional relationships that shape performance in complex systems. Likewise, learning pathway models help visualize students’ progressive acquisition of concepts [39,40,41], yet they do not specify the logical conditions under which individual concepts function as prerequisites, enablers, or bottlenecks within a dynamic learning architecture. Standard logic models used in evaluation research [42] also emphasize inputs, activities, and outcomes but lack mechanisms to formalize bidirectional dependencies or to integrate heterogeneous evidence into a reproducible structural model.

In contrast, the GTST-MLD framework provides a level of structural granularity and functional precision that surpasses the representational capacities of existing pedagogical models. Rooted in system reliability engineering [2,31] and extended through semi-qualitative modeling approaches [16], GTST-MLD decomposes a system into goal-oriented hierarchies and success-condition structures, enabling explicit representation of how and why system functions interact. Its bidirectional reasoning capacity, supporting both top-down (goal-driven) and bottom-up (evidence-driven) inference, offers analytic flexibility unavailable in linear frameworks such as ToC or LFA. Furthermore, GTST-MLD supports the integration of qualitative and quantitative evidence into a single auditable representation, linking expert insights, empirical observations, and conceptual dependencies within a unified logic-based structure. This capacity aligns the framework with contemporary perspectives in systems thinking and socio-technical modeling [8,43], which emphasize multi-layered causality, feedback, and adaptive interactions.

Given these characteristics, GTST-MLD is not proposed as a substitute for established pedagogical tools but as a complementary analytical approach particularly suited for complex, non-physical, human-centered systems where internal dependencies between concepts, behaviors, and actions profoundly shape performance. Its logic-based structure enables a more explicit connection between TCs, LOs, and instructional strategies than is achievable through conventional pedagogical mapping tools. This functional transparency ultimately justifies the selection of GTST-MLD for modeling the system examined in this study.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the research design, stages, and analytical methods applied to develop the GTST-MLD model for representing complex non-physical systems. The methodological process integrates a mixed approach, combining literature-based, qualitative, and quantitative analyses to identify TCs, map teaching–learning methodologies supported by empirical and literature-based evidence, and construct a function-centered model of the teaching–learning process.

3.1. Research Approach

The methodological goal of this study was not to reassess or redefine the GTST-MLD framework, nor to generate general theoretical claims about function-centered modeling. Instead, the purpose of the research design was to operationalize an existing modeling framework (GTST-MLD) within a bounded, real-world educational subsystem, namely the teaching–learning process of a single Project Engineering course, to examine whether GTST-MLD can offer a clear, auditable, and functionally structured representation of conceptual, methodological, and learning dependencies. Consistent with the study objective stated in the Introduction, the aim was to test the applicability of GTST-MLD to a non-physical system and to determine whether its hierarchical logic supports the analysis of interdependent components of the learning process.

To avoid overstating the role of quantitative analysis, it is important to clarify that the quantitative component of this study served a descriptive rather than an inferential purpose. Survey ratings were analyzed through simple frequency distributions and percentage counts that indicated the prevalence of perceived difficulty and the extent to which each candidate concept was judged transformative, integrative, troublesome, or irreversible. These indicators were used exclusively to support the triangulation process and to determine the relative strength of the evidence informing the GT, ST, and MLD structures. No inferential statistics were conducted and no causal claims regarding learning effectiveness were made, as the objective of this study was to develop an auditable, function-centered representation rather than to test pedagogical impact.

Accordingly, this study does not attempt to deepen the understanding of function-centered modeling at a theoretical level. Rather, it applies a well-established modeling framework to a new domain and evaluate its explanatory usefulness. HE was selected as the non-physical system of interest due to its inherently complex, adaptive, and multi-layered nature, and a single course was modeled as a bounded subsystem. This approach enables controlled methodological transfer while avoiding unsupported generalizations about system-wide governance or planning.

Given the cross-cutting role of the teaching–learning process in curriculum design, each course in an undergraduate program presents distinct TCs, pedagogical needs, competencies, evaluations, resources, and links to professional contexts. For simplification, this research modeled the teaching–learning process of a single course, Project Engineering, recognizing that this method is both replicable and scalable across the curriculum.

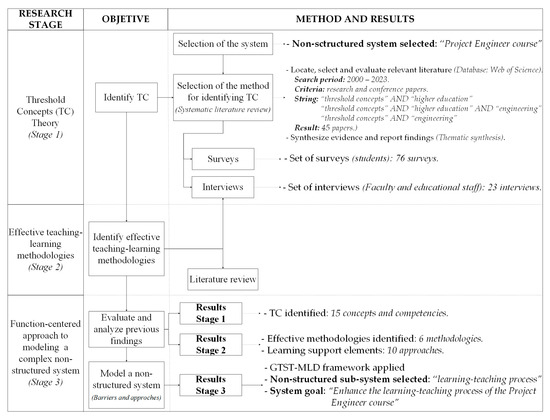

A structured three-step research design was implemented to construct a GTST-MLD model integrating TCs and effective learning approaches (see Figure 1). This staged research design ensures that the modeling process is derived directly from empirical evidence (Stages 1 and 2) before being represented functionally in Stage 3, thereby maintaining methodological alignment with this study’s stated objective of applying GTST-MLD within a bounded non-physical subsystem.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the research design.

3.1.1. Stage 1. Threshold Concepts Identification

TCs are discipline-specific ideas that, once understood, fundamentally alter learners’ cognitive frameworks and enhance their ability to analyze and solve complex problems. Initially introduced to address persistent learning difficulties in HE, TCs act as conceptual gateways that enable deeper subject comprehension and knowledge transfer [44]. Their transformative nature shifts learners’ perspectives by integrating new conceptual frameworks that are essential for advanced understanding [45]. TCs are transformative, integrative, irreversible, and often troublesome, challenging learners’ pre-existing knowledge structures. Their liminal nature introduces a transitional phase where uncertainty and setbacks precede mastery; failure to navigate this phase effectively results in fragmented understanding [45]. Addressing these barriers is crucial for improving LOs.

Although various methodologies exist to identify TCs [46], no single approach is universally accepted due to the process’s inherent complexity and subjectivity. Some studies use predefined TC lists, while others adopt open-ended approaches to minimize bias. The iterative nature of these methods refines TC selection, ensuring depth and contextual relevance. The first stage aimed to identify TCs within the Project Engineering course, a core subject in industrial engineering and a transversal course across other engineering programs.

A Systematic Literature Review (SLR) was conducted to identify the most appropriate methodologies for TC identification, following a formal protocol aligned with PRISMA 2020 [47] guidelines to ensure transparency and replicability. The Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC) was selected as the primary database due to its comprehensive coverage of engineering education and learning sciences. Searches were performed in the Title, Abstract, and Author Keywords fields using three Boolean search strings that combined controlled vocabulary and free terms:

- String 1: TS = (“threshold concept*” AND engineering*)

- String 2: TS = (“threshold concept*” AND “higher education” AND “engineering”)

- String 3: TS = (“threshold concept*” AND “engineering”))

The time window for the analysis spanned from 2003 to 2023, beginning with the publication of the foundational TC theory and ending in the year of data collection. Inclusion criteria required studies to be peer-reviewed journal articles or conference papers, explicitly focused on TC identification, measurement, or application, relevant to engineering or STEM education, and available in full text in English. Exclusion criteria comprised purely conceptual or opinion papers lacking methodological detail, studies not involving TC identification, duplicates, and non-English texts.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two researchers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. In total, 87 records were identified, and 12 duplicates were removed, resulting in a final corpus of 45 articles meeting all eligibility criteria. The information extracted from these studies was synthesized using a thematic synthesis approach, categorizing methodologies into seven groups according to their use in the literature.

To complement the SLR, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 23 faculty members from the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM), representing nine engineering schools and programs. The participants included 19 engineers, two architects, one environmental scientist, and one physical chemistry specialist, with professional experience ranging from 3 to 25 years in project-engineering education.

The interview protocol included 18 questions across five sections:

- Section 1: Profile information;

- Section 2: Identification of significant course concepts and justification, concluding with an introduction to TC theory [44];

- Section 3: Guided analysis of course content to identify potential TCs based on their problematic, transformative, irreversible, and integrative characteristics, consistent with the structure proposed by [46,48];

- Section 4: Reflection on troublesome learning experiences and potential course improvements;

- Section 5: Implementation of TCs in teaching, focusing on tools and mechanisms for their acquisition.

Following the interviews, a focus group was conducted with the same faculty members to validate and refine the TCs identified. This collaborative process promoted discussion and consensus, leading to the discovery of new or previously overlooked TCs.

Student perspectives were then incorporated through a survey, providing broader validation of faculty findings. A total of 76 responses were collected from 110 enrolled students. The survey consisted of eleven questions (eight quantitative, three open-ended) organized into four sections:

- Section 1: General respondent information;

- Section 2: Open-ended question about important and challenging concepts;

- Section 3: Evaluation of faculty-identified TCs using a seven-point Likert scale, including classification as problematic, transformative, irreversible, or integrative, following [49]. Importantly, the quantitative section included four items directly aligned with the core TCs attributes defined by [45,50] allowing students to evaluate each candidate concept on its characteristic threshold dimensions rather than on perceived difficulty alone.

- Section 4: Course satisfaction and perceptions of the teaching–learning process.

The integration of faculty interviews, student survey responses, and the results of the systematic literature review formed the basis of the triangulation process used in this stage. The survey data were examined descriptively to identify recurring patterns of conceptual difficulty, which were then compared with the themes emerging from the semi-structured interviews. These interviews, in turn, provided detailed qualitative evidence regarding the concepts perceived as transformative, integrative, troublesome, or essential for progress in the course. This triangulated approach, documented in the technical reports that preceded this study, ensured that the identification of candidate TCs was grounded in convergent evidence obtained from complementary sources rather than relying on a single dataset.

Quantitative results were incorporated into the analysis through descriptive indicators derived from the student survey. Across the 76 responses, the four TC attributes showed differentiated patterns consistent with TC theory: concepts identified by more than 60% of students as “transformative” or “integrative” also tended to show higher perceived difficulty, while those selected by fewer than 30% of respondents exhibited low evidence intensity and were excluded from the final TC set. Faculty interviews reinforced these patterns: twelve of the fifteen retained concepts were mentioned independently by at least five instructors, and nine were identified across all three data sources (interviews, survey, and literature review). These aggregated indicators informed the semi-qualitative weighting used in the MLD (high, medium, or low intensity), ensuring traceability between the empirical evidence and the dependency structure represented in the model.

3.1.2. Stage 2. Identification of Effective Teaching–Learning Methodologies

The objective of this stage was to identify effective strategies for enhancing the teaching–learning process based on the TCs identified in Stage 1. A literature review complemented by an analysis of faculty interviews was conducted to map the most relevant and recent methodologies. The review focused on the most recent six-year period (2018–2023) to capture up-to-date pedagogical trends, technological innovations, and evolving educational needs [51]. This integrated approach provided a comprehensive understanding of emerging practices and innovations that can enhance the teaching–learning process.

In parallel with the initial review, a targeted six-year literature review (2018–2023) was conducted to identify contemporary pedagogical methodologies aligned with the assimilation of TCs. Although distinct from the Stage 1 SLR, this review adhered to systematic procedures to ensure rigor and replicability. The WoSCC was selected as the primary database due to its comprehensive coverage of engineering education and higher education research. Searches were performed in the Title, Abstract, and Author Keywords fields using the following Boolean string:

TS = ((“engineering education” OR “higher education”) AND (“active learning” OR “PBL” OR “CBL” OR “flipped classroom” OR “experiential learning” OR “collaborative learning”)).

The inclusion criteria required studies to be peer-reviewed articles published between 2018 and 2023, to provide empirical or experimental evaluations of teaching–learning methodologies, and to demonstrate relevance to concept acquisition or competency development. Screening was conducted independently by two reviewers, and any disagreements regarding eligibility were resolved through consensus.

The final selection comprised 32 articles that met all criteria. This targeted review ensured the identification of pedagogical approaches consistent with recent trends and technological innovations in higher education, providing a robust foundation for understanding strategies that support TC assimilation.

3.1.3. Stage 3. Function-Centered Approach to Modeling an Unstructured System

The third stage aimed to model barriers and strategies for enhancing the teaching–learning process, conceptualized as a system of interconnected functions and components. The GTST-MLD framework was employed to functionally decompose this process, integrating two core components:

- The GT, which decomposes high-level objectives into sub-functions;

- The ST, which defines the conditions required to achieve these goals.

The MLD maps dependencies between system elements and functions, offering a comprehensive view of component interactions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A schematic form of the GTST-MLD modeling approach (adapted from [2]).

The model construction followed three steps:

- System characterization: defining the operational environment of the teaching–learning process.

- System decomposition: identifying the main system goal and key contributing functions [2,4,36]. Decomposition proceeded until further breakdown required material specification, marking the transition to the ST, which detailed basic GT functions. Logical binary input–output relationships represented intra- and inter-tree dependencies [16]. Dependencies between main and support functions were depicted through lattices, with filled dots indicating required elements (e.g., element Y supports function B, while X supports A and C). Mutual dependencies were represented by bidirectional arrows.

- Model synthesis: constructing a conceptual schematic summarizing all components and relationships.

3.2. Data Analysis

Data analysis aimed to interpret how TCs and teaching strategies interact to shape the learning process. It was conducted in two complementary phases (qualitative and quantitative) integrated through a mixed-methods approach to enhance the understanding of TCs and teaching–learning strategies in the Project Engineering course.

The qualitative analysis followed a thematic approach based on the TC framework proposed by [45]. Interviews were fully transcribed and coded into categories such as TCs, learning difficulties, conceptual transformation moments, and effective teaching strategies. Codes were grouped into themes representing the challenges and transformations associated with TCs. Themes were iteratively reviewed to ensure consistency and relevance within the context of transformative learning.

The quantitative analysis applied descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, and simple comparative summaries. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to determine the prevalence of teaching–learning approaches and the perceived difficulty of TCs. This phase quantified relationships between TC difficulty and the effectiveness of teaching methodologies, reinforcing qualitative insights.

Results from both analyses were discussed in a focus group, where patterns observed in interviews and surveys were further explored. This triangulation provided a comprehensive view of how TCs influence learning and which strategies most effectively address associated challenges.

Finally, findings from the second literature review were incorporated to identify evidence-based teaching–learning approaches. The teaching–learning process was then modeled as a complex system using the GTST-MLD approach, integrating TCs and strategies that enhance systemic performance.

4. Results

This section presents the main findings derived from the three research stages described in the methodology: (1) identification of TCs, (2) identification of effective teaching–learning approaches, and (3) modeling the teaching–learning process using the GTST-MLD framework. Each stage builds upon the previous one, integrating empirical evidence and functional modeling to represent the educational process as a complex adaptive system.

4.1. Stage 1 Findings: Threshold Concepts Identification

The first objective of this stage was to determine the most effective methods for identifying TCs through an SLR and a mixed-methods analysis. General findings show that TC identification approaches vary according to this study’s goals, context, and stakeholder involvement. Different educational scenarios, such as curriculum redesign, development of new pedagogical tools, or identifying critical learning bottlenecks, require distinct methodological combinations.

The thematic analysis of 45 selected studies revealed seven recurrent TC identification methods, emphasizing the diversity of strategies used in recent years. Surveys are frequently applied to collect information from students because they ensure high participation rates and minimize respondent intimidation. Although not typically designed for TC discovery, surveys are highly effective for validating concepts pre-identified by experts [52].

Interviews, conversely, are preferred for faculty and educational staff, as they provide richer and more contextualized insights. This method allows identifying underlying conceptual barriers and capturing the tacit reasoning behind instructors’ pedagogical decisions. Content analysis of course materials complements these findings by identifying recurring themes and conceptual challenges within curricula. Other methods, such as literature synthesis, concept mapping, focus groups, and workshops, provide triangulation, consensus building, and validation of potential TCs [44,49].

In this study, the combined iterative approach proves the most effective: interviews and content analysis were first conducted to generate a preliminary list of TCs; surveys were then used to quantify and validate these results, and a focus group allowed for final refinement and consensus among faculty. This iterative cycle ensured methodological rigor and stakeholder alignment.

As a result, fifteen TCs were identified through the Stage 1 SLR and the expert interviews conducted on the Project Engineering course. Table 1 provides a complete list of the TCs, their definitions, and their classification according to the four core attributes proposed by [45,50]: transformative, irreversible, integrative, and troublesome. Although Table 1 summarizes the operational definitions and threshold attributes of each TC, the numerical evidence counts from faculty interviews (N = 23) and student responses (N = 76) are not displayed in the table. Instead, these counts were used internally during the triangulation process and are reported narratively in Section 3.1.1 to maintain clarity and avoid overloading the table.

Table 1.

Identified Threshold Concepts.

The distribution of attributes confirms that most TCs exhibit a full set of threshold characteristics, with transformative, integrative, and troublesome features appearing most frequently. Faculty and student evidence show strong agreement, particularly for TC3 (Process Engineering), TC8 (Systemic Thinking), and TC15 (Practical Engineering Constraints), which were consistently identified as difficult yet conceptually pivotal.

Likewise, these TCs act as functional primitives within the GT, structuring the base level of the GTST-MLD model presented in Stage 3. These findings establish the foundational knowledge elements that shape the system’s functional layer and guide the subsequent modeling process.

4.2. Stage 2 Findings: Effective Teaching–Learning Approaches

Building upon the identified TCs, Stage 2 aimed to determine the most effective teaching–learning methodologies and support mechanisms for facilitating their assimilation. The literature review and complementary data analysis revealed a clear shift in HE toward active, experiential, and technology-enhanced learning paradigms, particularly relevant in engineering contexts [53].

The selection of teaching–learning methodologies was not derived from general pedagogical trends but from the functional requirements imposed by the TCs identified in Stage 1. Because TCs are defined by their transformative, integrative, troublesome, and irreversible nature [45,50], the set of 15 TCs identified in this study generated specific cognitive and epistemic demands that shaped the choice of methodologies. Concepts such as Process Engineering, Systemic Thinking, Economic Feasibility, and Project Scope require learners to reorganize prior knowledge structures, integrate multiple representations, and apply reasoning under uncertainty, patterns consistently documented in TC literature [48,54]. These cognitive requirements align with pedagogical approaches that promote deep learning through iteration, collaborative sense-making, and authentic problem engagement. Accordingly, methodologies were selected based on their documented capacity to facilitate TC acquisition, as evidenced in engineering and STEM education research. Active and experiential approaches (such as Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Case-Based Learning (CBL), flipped learning, collaborative learning, and experiential practice) are strongly associated with conceptual change, integrative reasoning, and improved navigation of troublesome knowledge [55,56,57,58]. Thus, the methodological choices in Stage 2 respond directly to the functional characteristics of the TCs identified, rather than to a generic adoption of contemporary pedagogical techniques.

Active learning methods, such as flipped classrooms and peer instruction, have been shown to improve engagement, conceptual retention, and motivation. Collaborative models, including PBL and CBL, emphasize teamwork, communication, and critical thinking [59]. In engineering education, these approaches align closely with the practical and project-oriented nature of the discipline.

Digital transformation has accelerated the use of virtual environments, Learning Management Systems (LMS), and immersive technologies that enhance access and personalization [60]. Project-based and experiential learning approaches further connect academic theory with professional practice, enabling students to develop both technical and managerial competencies [61,62]. Blended learning and guest lectures extend these benefits by combining theoretical, applied, and industry-based experiences [63,64].

Complementary strategies such as dynamic group activities, gamification, and maker-based learning enhance creativity and autonomy [53,65,66]. Additional tools, like short quizzes, self-directed learning, and teamwork learning platforms, serve as reinforcing mechanisms that consolidate TC assimilation [67,68].

The integration of findings from the literature and empirical data allowed identifying five core teaching–learning methodologies consistently associated with the assimilation of difficult and conceptually demanding content in engineering education. These methodologies, grounded in evidence from literature, are: (1) PBL, (2) CBL, (3) Flipped Classroom (FC), (4) Collaborative Learning (CoL), and (5) Experiential/Practice-Based Learning (EBL). PBL and CBL promote conceptual restructuring by situating learners in authentic professional scenarios [56]. The FC emphasizes pre-class content assimilation and in-class application [69,70]. Collaborative Learning facilitates the social dimension of threshold crossing [57]. Finally, EBL grounds conceptual understanding in concrete engineering tasks, following the experiential learning cycle [58,71].

Several learning support elements were also considered (e.g., teamwork tools, gamification, field trips, external talks).

Their inclusion in the ST follows three criteria:

- Relevance: direct contribution to TC assimilation and competency acquisition;

- Replicability: potential to be consistently applied across courses and contexts;

- Adaptability: capacity to scale to different class sizes, formats, and institutional environments.

In this study, the integration between TC theory, active learning methodologies, and GTST-MLD is not presented as a conceptual overlay but as a functional alignment grounded in how complex systems are structured and analyzed. TCs define the critical functions that enable progression within a learning system [45], while active learning methodologies structure the mechanisms through which these functions can be achieved in practice [57,72]. GTST-MLD, for its part, provides a formalism capable of representing hierarchical goals, intermediate functions, and success conditions [31]. The three elements thus map naturally onto the GT (learning goals), intermediate nodes (TCs), and ST (methodological support functions). This alignment is consistent with work demonstrating that hierarchical, function-based representations can be applied to human-centered or socio-technical systems to make interdependencies analytically tractable [24,26], indicating that the use of GTST-MLD here serves as a structured analytical lens rather than an imposed pedagogical analogy.

Building on this conceptual alignment, the triangulated evidence from faculty interviews and student responses showed that difficulties associated with the highest-intensity TCs stemmed from challenges in applying abstract concepts to realistic engineering constraints, coordinating multiple representations, and integrating procedural and conceptual knowledge. These are precisely the types of challenges for which PBL and CBL have demonstrated strong empirical efficacy in engineering contexts [61,62], while collaborative learning supports the social dimension of navigating liminal states [73] and experiential/practice-based learning strengthens the irreversibility and integrative aspects of threshold crossing [58]. Therefore, the five selected methodologies emerged from a direct mapping between TC-specific learning barriers and evidence-based strategies documented in the recent literature, ensuring functional consistency between Stage 1 and Stage 2.

4.3. Stage 3 Findings: A Function-Centered Approach to Modeling the Teaching–Learning Process

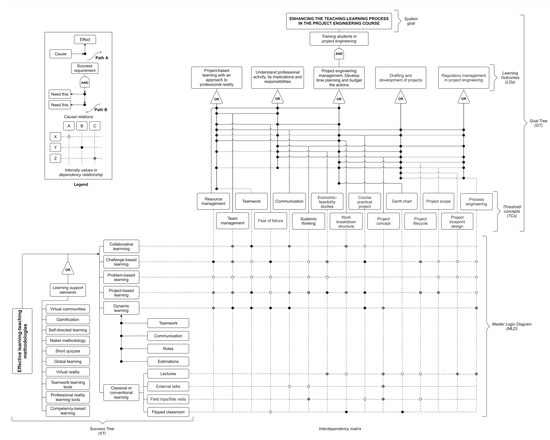

After defining the system components through TCs and teaching methodologies, Stage 3 applies the GTST-MLD framework to represent the Project Engineering course as a complex, adaptive system. This model integrates pedagogical goals, TCs, and effective methodologies through a functional–structural decomposition (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of the GTST-MLD model applied to the teaching–learning process in the Project Engineering course.

Beyond the graphical representation, the application of GTST-MLD yielded several analytical insights that were not identifiable through interviews, surveys, or descriptive analysis alone. First, the functional lattice exposed five high-centrality TCs (Project Lifecycle, Project Scope, Process Engineering, Project Concept, and Practical Project) that operate as structural bottlenecks because they support multiple LOs and accumulate the highest-intensity methodological dependencies. Second, the decomposition revealed redundancy patterns within the methodological layer: three strategies (PBL, CBL, and experiential learning) converge on the same cluster of TCs, indicating areas where instructional effort is disproportionately concentrated. Third, the MLD highlighted under-supported concepts, such as economic feasibility studies, which displayed weak methodological coverage and low evidence intensity. These system-level patterns emerge only when the learning process is represented through formal functional dependencies, illustrating how GTST-MLD contributes analytical value beyond the qualitative and quantitative findings generated in Stages 1 and 2.

4.3.1. System Description: Environment and Essential Aspects

Understanding the system’s environment is essential for analyzing the dynamics of this non-physical, unstructured process. The analysis operates at two interconnected levels: the Spanish HE system and the Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (UPM).

In Spain, HE operates within a regulatory framework that balances institutional autonomy with quality assurance in education, research, and social engagement. It emphasizes in-person learning while enabling hybrid and virtual modalities to meet diverse educational needs. Continuous assessment and stakeholder participation ensure curricular adaptation to evolving professional and societal contexts. Innovation and faculty development are prioritized to foster alignment with European and global standards.

UPM applies this national framework through its autonomy to integrate academic, research, and social objectives. By combining in-person, hybrid, and virtual teaching, UPM strengthens international collaborations, dual-degree programs, and research-education synergies. These institutional mechanisms support the systemic adaptability required for effective engineering education.

4.3.2. Goal Tree: Functional Decomposition

The GT establishes the hierarchical structure of system objectives. The primary goal is to enhance the teaching–learning process in the Project Engineering course. This goal decomposes into progressively smaller sub-goals aligned with the course LOs:

- Project-based learning with an approach to professional reality;

- Project Engineering management, developing time planning and budgeting;

- Regulatory management in Project Engineering;

- Understanding professional activity, implications, and responsibilities;

- Drafting and developing engineering projects.

Each sub-goal follows a logical AND relationship, requiring all to be achieved to fulfill the main system objective. Lower-level functions and sub-functions represent the assimilation of TCs and threshold competencies, such as teamwork and communication, which support LO attainment. These supporting elements are connected through OR relationships, representing partial yet valuable contributions to LOs.

This hierarchical decomposition clarifies the “why” and “how” of the educational process, enabling systematic analysis of the interdependencies between learning objectives, competencies, and pedagogical functions.

4.3.3. Success Tree: Structural Decomposition

The ST complements the GT by linking effective teaching–learning methodologies to the functional elements defined above. It incorporates five primary methodologies and ten supporting strategies identified in Stage 2. The ST structure captures redundancy and flexibility in achieving learning functions, recognizing that multiple methods may fulfill similar roles.

The model also provides educators with practical alternatives for facilitating TC acquisition within the existing course structure. Future iterations could integrate variables such as curriculum updates, class size, and teaching hours to expand the model’s adaptability. Furthermore, the ST framework allows for abstraction at higher scales, from course-level improvements to entire program redesigns, supporting continuous learning innovation.

4.3.4. Master Logic Diagram

The MLD visualizes the network of interrelations between the GT and ST, forming a lattice that connects goals, functions, TCs, and teaching methodologies. It provides both a structural and behavioral representation of the system, translating the abstract dynamics of the teaching–learning process into a functional map of dependencies (see Figure 3). The MLD integrates the hierarchical decomposition from the GT, which defines what must be achieved, with the ST, which defines how these objectives are fulfilled. Each point within the MLD matrix represents a dependency between a main function (upper layer) and a supporting methodology or learning element (lower layer) (i.e., the logical link between conceptual learning objectives and operational teaching mechanisms). Filled dots of different intensities symbolize the strength or relevance of these relationships, as determined through qualitative and quantitative data integration.

The use of different dot intensities follows the semi-qualitative convention adopted in the technical documentation, inspired by the dependency–strength notation described by Ref. [16]. In this approach, the varying fill levels reflect differentiated degrees of methodological contribution to the acquisition of each TC. This notation complements the standard GTST-MLD rule introduced by Ref. [31], in which a filled dot indicates the existence of a functional dependency between elements of the ST and the GT. Incorporating intensity levels allows the model to express nuanced variations in the strength of these dependencies while preserving the underlying logical structure. To support full auditability, the complete node dictionary and the machine-readable dependency matrix corresponding to the MLD are included in Appendix A.

This representation enables bidirectional analysis of the teaching–learning system:

- Upward (bottom-to-top): tracing how specific teaching methodologies contribute to higher-level learning goals;

- Downward (top-to-bottom): identifying the methods and support mechanisms most effective in facilitating TC assimilation.

For instance, examining PBL upward reveals strong dependencies with teamwork and the course practical project TC, moderate dependencies with project lifecycle, and weaker ones with economic feasibility studies TC. This gradient of intensity mirrors the pedagogical alignment of each TC with the methodology’s experiential nature.

In contrast, following the path downward from a single TC, such as economic feasibility studies, shows how its assimilation is supported by multiple teaching strategies, including CBL and PBL. The combined application of these methods increases student exposure to integrative, problem-oriented environments, thereby reinforcing conceptual stability.

However, the use of multiple methodologies requires balance: while diversity of methods enhances adaptability, it can also increase cognitive load, time constraints, and complexity in course management. Thus, the MLD not only maps effective pathways but also highlights trade-offs between methodological intensity and systemic manageability, an essential consideration in HE system design.

As noted in [14], this approach effectively addresses uncertainty within educational systems by identifying overlapping dependencies and revealing latent bottlenecks in the learning flow. The lattice therefore acts as a diagnostic and planning tool, allowing educators to visualize, adjust, and optimize how TCs, competencies, and methodologies interact across different course levels. This bidirectional visualization aids in understanding both the conceptual progression of learning and the practical alignment of teaching tools.

To ensure full transparency and reproducibility, the transformation of empirical evidence into the structure of the MLD followed a set of explicit and consistently applied mapping rules. The first component of this process concerns the representation of evidence strength. The dot intensities used in Figure 3 correspond to three levels of empirical support associated with each connection, whether between candidate TCs and teaching methodologies or between LOs and TCs. High-intensity dots indicate links supported concurrently by all three data sources employed in this study: faculty interviews, quantitative agreement from the student survey, and corroborating findings from the literature review. Medium-intensity dots represent connections supported by two of these sources, while low-intensity dots denote associations grounded in a single form of evidence. This graded representation enables a transparent visualization of the confidence level underlying each modeled dependency. A detailed description of all nodes used in the GTST-MLD model, including LOs, candidate TCs, methodologies, and support elements, is provided in Appendix A.1.

In addition to evidence intensity, the logical architecture of the GTST framework required the specification of gate logic for both GT and ST. At the GT level, the highest-order LOs operate under AND logic, meaning that the global function of the system requires the achievement of all top-level LOs. However, the relationships linking individual TCs to specific LOs follow OR logic: each TC contributes meaningfully to the LO it supports, but mastery of all TCs associated with a given LO is not necessarily required for the LO to be fulfilled. This distinction reflects the pedagogical reality that some concepts are indispensable while others provide complementary pathways toward similar functional achievements.

Within the ST, methodological and support components follow a different logic. Teaching methodologies display OR relationships, recognizing that different pedagogical approaches may serve as viable alternatives for supporting the acquisition of a particular TC, depending on instructional context or instructor preference. Conversely, supporting elements, such as digital tools, regulatory databases, or teamwork platforms, follow AND logic when they are required collectively for a methodology to function as intended. In these cases, the absence of one support element can compromise the methodological effectiveness and, by extension, the learner’s ability to progress through the corresponding TC.

Together, these rules convert the qualitative and quantitative findings of this study into a coherent logical structure that preserves the integrity of the mixed-methods evidence base while enabling an auditable representation of functional dependencies within the GTST-MLD model. The complete machine-readable edge list corresponding to all modeled dependencies is provided in Appendix A.2, ensuring full transparency and reproducibility.

To further clarify how these mapping rules operate in practice, the GTST-MLD structure can be illustrated through a representative example that traces the full pathway connecting a LO, a candidate TC, and the methodology that supports its acquisition. In the case of LO3 (Regulatory management), both faculty interviews and student responses indicated recurring difficulties in understanding how regulatory requirements interact with the internal logic of engineering processes. This convergence of qualitative and quantitative signals supports the identification of TC3 (Process Engineering) as a foundational element for achieving LO3, since this concept provides the analytical basis for connecting technical decisions with regulatory constraints. Following the evidence-to-intensity rules described above, the LO3-TC3 relationship receives a medium-intensity link, as it is consistently supported by two independent sources of evidence.

The methodological alignment derived in Stage 2 reinforces this dependency structure. Across the dataset, PBL emerged as the pedagogical approach most strongly associated with TC3, a finding supported by faculty observations, student reflections on effective learning strategies, and published literature. Because this TC3-PBL association is underpinned simultaneously by these three forms of evidence, the connection is represented in the MLD with a high-intensity link, indicating a strong and triangulated methodological contribution to overcoming the conceptual difficulties associated with TC3.

This example illustrates the operational logic of the GTST-MLD model: a LOs grounded in a threshold-like concept whose mastery, in turn, is supported by an instructional methodology validated through the mixed-methods evidence base. By making these pathways explicit, the model enhances the interpretability of Figure 3 and demonstrates how the functional dependencies encoded in the GTST-MLD can inform targeted pedagogical decisions.

4.3.5. The Combined GTST-MLD Framework

The integration of the GT, ST, and MLD into a composite GTST-MLD framework provides a multidimensional representation of the teaching–learning process. The lowest hierarchical level of the GT feeds directly into the MLD, ensuring that functional goals, success conditions, and learning mechanisms are interconnected. This combined model thus bridges abstract educational objectives with operational pedagogical strategies.

The framework enables two complementary analytical perspectives:

- Top-down interpretation: starting from the system’s main goal, enhancing the teaching–learning process, the model decomposes objectives into LOs, TCs, and competencies. Each LO depends on the assimilation of specific TCs and competencies. For instance, in LO(3), Regulatory management in Project Engineering, the essential TCs are process engineering, project scope, project lifecycle, project concept, and course practical project, supported by competencies such as communication and systems thinking. These are connected through OR relationships: while mastering all of them is not mandatory, each additional element contributes incrementally to performance.The top-down analysis therefore clarifies how LOs are achieved by decomposing abstract course goals into tangible, teachable components, facilitating strategic curriculum design and assessment alignment.

- Bottom-up interpretation: conversely, the bottom-up reading begins with a specific methodology, such as CBL, and explores its impact on the system by tracing upward connections. This process reveals why a given method is pedagogically justified and how it contributes to concept mastery. For example, CBL directly supports the assimilation of project concept, systemic thinking, and economic feasibility studies TCs, indirectly influencing the overall LO of drafting and developing projects.This bottom-up view allows instructors to select and combine methodologies according to their relevance, effectiveness, and alignment with intended outcomes. It also promotes evidence-based instructional design by linking micro-level teaching strategies with macro-level system objectives.

The combined GTST-MLD framework thus provides a diagnostic and prescriptive tool: diagnostic in its capacity to reveal weaknesses or redundancy in learning pathways, and prescriptive by enabling the planning of targeted pedagogical interventions.

Beyond the educational domain, the model’s systemic logic can be extended to analyze other human-centered complex systems, such as policymaking, organizational management, and community planning. By structuring interdependencies between objectives, functions, and success conditions, GTST-MLD provides a scalable and transferable framework for optimizing coordination and adaptability in dynamic environments.

Overall, the expanded GTST-MLD model demonstrates that complex learning environments can be analyzed, diagnosed, and enhanced using function-centered modeling principles, thereby linking human cognition, organizational design, and adaptive system performance.

5. Discussion

The construction of this model required a rigorous process of research and analysis, providing valuable insights into the complex interactions and dynamics present in open and non-physical systems such as the teaching–learning process. Its relevance extends beyond curriculum design, contributing to the understanding of how individual and collective knowledge evolves in HE. The discussion that follows explores the theoretical and practical implications of these findings, situating them within the frameworks of CAS and TC theory, and examining their potential applicability to other human-centered systems with similar characteristics. Additionally, the limitations of the proposed model and its potential contributions to understanding and improving the teaching–learning process are analyzed.

These findings position HE as a prototypical complex adaptive system in which interdependencies among teaching strategies, LOs, and cognitive transformations emerge dynamically and nonlinearly [27,28]. Understanding this complexity requires analytical tools that go beyond descriptive pedagogy and enable a functional mapping of how learning structures evolve, adapt, and self-organize, precisely the purpose of applying function-centered modeling through the GTST-MLD framework.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Applying the GTST-MLD framework to model non-physical complex systems represents a novel contribution to both systems engineering and educational research. In practical and theoretical terms, this contribution consists of demonstrating that a hierarchical, function-centered modeling framework, historically restricted to safety-critical engineered systems, can be operationalized to represent conceptual, cognitive, and pedagogical interdependencies within a human-centered, non-physical system. Unlike conventional pedagogical models, GTST-MLD formalizes goal–function–success relationships using explicit logical gates and functional decomposition rules [2,31], thereby enabling the representation of learning processes as structured networks of dependencies rather than descriptive narratives. This formalization provides three theoretically novel elements: (i) it defines TCs as functional control nodes that condition system performance, a role analogous to critical functions in engineered systems; (ii) it shows how LOs, TCs, and methodologies can be mapped into a coherent, auditable hierarchical architecture; and (iii) it demonstrates that mixed-methods educational evidence can be encoded into a semi-qualitative model using dependency–strength conventions previously applied in reliability and industrial systems modeling [16]. These elements collectively support the claim that GTST-MLD can be extended beyond physical domains by providing a rigorous, logic-based analytical structure capable of representing interdependencies and emergent patterns inherent to complex educational systems, consistent with recent CAS-oriented scholarship in HE [27,28].

Traditionally employed in physical system modeling, particularly in safety-critical industries such as aerospace and nuclear energy [2,4], GTST-MLD has now demonstrated its adaptability to cognitive and institutional domains. This adaptation establishes a bridge between function-centered modeling and learning systems theory, showing that the same analytical rigor used in technical reliability assessment can also structure human learning processes.

The hierarchical decomposition of learning objectives, TCs, and pedagogical methodologies into goal-oriented structures aligns with previous research on structured knowledge acquisition [45,48]. Yet, beyond alignment, it introduces a theoretical unification between TC theory and CAS: both frameworks view learning as an emergent, non-linear process shaped by feedback, iteration, and contextual adaptation. By framing the teaching–learning process as an open and adaptive system, this study reinforces the theoretical robustness of function-centered modeling in educational contexts, a field where systemic formalisms are still underrepresented [15].

This theoretical extension also advances TCs research. While prior studies have focused on the transformative, integrative, and troublesome nature of TCs [53], the GTST-MLD model embeds them within a goal-success logic, making their acquisition measurable through functional dependencies. This structured perspective allows TCs to be positioned not merely as learning milestones but as control nodes in the system, whose assimilation determines the overall performance of the educational process.

Moreover, the incorporation of support functions, such as collaborative learning, technology-enhanced learning, and peer engagement, reflects an alignment with modern constructivist paradigms [53]. Through this integration, GTST-MLD extends its conventional use in failure diagnosis and reliability assessment [15] to a new domain: modeling cognitive, social, and pedagogical interdependencies. This advancement deepens our theoretical understanding of learning systems as purpose-driven adaptive networks, consistent with current CAS scholarship [27].

Unlike models traditionally used in educational research, such as ToC, Learning Pathway Maps, or logic-model frameworks, which provide narrative or causal-chain descriptions but rarely formalize functional dependencies [42,74,75], GTST-MLD enables the explicit encoding of hierarchical relationships and necessary conditions between conceptual nodes. This capacity is particularly relevant for TCs, which function as bottlenecks or control points in a learning architecture. By mapping TCs as intermediate functional nodes and linking them to both LOs and pedagogical mechanisms, GTST-MLD operationalizes constructs that are often discussed abstractly in the literature, thus enabling systematic analysis of the structural coherence of the learning process.

Beyond these contributions, the GTST-MLD framework also complements existing approaches commonly used to represent learning and organizational change, such as logic models, ToC, and learning pathway representations. While these frameworks articulate intended causal progressions and project-level assumptions, they often lack the ability to formalize the internal functional architecture through which system behavior emerges. In contrast, GTST-MLD provides a multi-layered mapping of dependencies that exposes structural bottlenecks, redundancies, and enabling conditions that remain invisible in high-level causal diagrams. This distinction aligns with recent calls in educational systems research for formalisms capable of representing nested dependencies and adaptive feedback processes within human-centered systems [26,76]. It also resonates with complexity-informed decision frameworks which emphasize the need for analytical tools that distinguish between surface-level causal descriptions and deeper systemic patterns that shape emergent outcomes [43]. Through this additional granularity, GTST-MLD strengthens current theoretical efforts to bridge systems engineering logics with educational and organizational complexity, offering a diagnostic lens grounded in functional interdependencies rather than purely descriptive narratives.

The contribution of this study therefore does not lie in proposing new pedagogical techniques or new TC attributes, which are already well established in the literature, but in demonstrating how GTST-MLD can integrate these elements into a single, auditable, function-centered model. The resulting representation makes explicit: (a) the functional role of each TC in achieving higher-level learning goals; (b) the conditions under which specific methodologies support TC acquisition; and (c) the system-wide pathways that influence performance within a bounded learning environment. This form of functional transparency has not been previously documented in TC research or in GTST-MLD applications.

5.2. Practical Implications

Applying GTST-MLD to the Project Engineering course yields actionable insights for curriculum design and pedagogical innovation. By systematically identifying and addressing TCs, educators can use the model to identify opportunities for designing interventions that mitigate conceptual bottlenecks, thus enhancing comprehension, engagement, and knowledge retention [52]. The hierarchical structure of the model facilitates targeted teaching strategies by clarifying the dependencies between LOs, TCs, and competencies.

In practical terms, the GTST-MLD decomposition revealed several structural patterns that were not identifiable from interviews, survey responses, or literature-based analysis alone. Specifically, the model exposed (i) high-dependency TCs that function as systemic bottlenecks across multiple LOs, (ii) clusters of redundant methodological effort where distinct teaching strategies converged on the same subset of concepts, and (iii) under-supported conceptual areas, such as economic feasibility studies, where methodological coverage proved weak. These patterns constitute actionable diagnostic outputs of the framework, guiding instructors in reallocating teaching effort, balancing methodological intensity, and identifying fragile points in the conceptual architecture of the course. None of these system-level insights could be derived from traditional descriptive pedagogical analyses without formal functional modeling.

Beyond these diagnostic patterns, the GTST-MLD analysis generated a set of specific and actionable insights derived uniquely from the model’s functional structure. First, the MLD revealed that TC3 (Process Engineering) acts as a system-wide control node, supporting three LOs and concentrating the highest-intensity methodological dependencies; strengthening this concept would therefore trigger disproportionate improvements across the course. Second, the lattice exposed methodological redundancies where PBL and CBL targeted the same cluster of concepts, while only PBL activated the full set of AND-logic support elements needed for LO5, suggesting efficiency gains through strategic reallocation of teaching effort. Third, the bidirectional navigation of the model identified alternative functional pathways, for instance, LO2 can be achieved either through the TC1-TC3 dependency chain (primarily supported by PBL) or through TC4 in combination with FC strategies, providing structurally grounded options for redesigning teaching sequences. Fourth, the model uncovered hidden interdependencies between competencies and concepts: teamwork emerged as a success condition for four TCs, indicating that strengthening this competency early would unlock multiple subsequent learning functions. Finally, the analysis highlighted system sensitivities, such as the fact that the absence of a single enabling resource (e.g., regulatory database access) weakens the effectiveness of two methodologies simultaneously for LO3. Together, these insights demonstrate that GTST-MLD produces an auditable, structurally grounded set of recommendations unavailable through conventional pedagogical evaluation.

A key practical contribution lies in recognizing effective learning methodologies as support functions within the GTST-MLD framework. The integration of PBL, CBL, and FC techniques within the ST underscores their pivotal role in facilitating TC assimilation. This structured representation allows instructors and curriculum designers to visualize where specific methodologies exert the strongest pedagogical impact, enabling more precise resource allocation and time management. The model’s functional lattice thus becomes a diagnostic and prescriptive tool for instructional decision-making, consistent with continuous improvement cycles in HE.

While the model shows strong internal validity within the Project Engineering course at a single institution, its applicability beyond this context should be interpreted cautiously. The present study does not provide empirical evidence of transferability across programs, disciplines, or institutions. Any broader use of the GTST-MLD framework therefore remains a potential direction for future research rather than an established generalization.

The model provides a structured analytic pathway that may be transferable, but further empirical studies across multiple courses, universities, and disciplinary domains are required to confirm its generalizability. As HE landscapes increasingly integrate digital tools and interdisciplinary learning, GTST-MLD provides a structured methodology that can help align innovation with measurable outcomes, potentially informing efforts to enhance systemic adaptability within educational settings [28].

In sum, the practical implications extend beyond isolated course enhancement to systemic educational governance, supporting data-informed, evidence-based decision-making in curriculum management.

5.3. Implications for Social Complexity and Transformative Change

Research on educational institutions as CAS demonstrates that social and learning environments exhibit multi-level interactions, feedback loops, and emergent behaviors that require analytic tools capable of representing nested dependencies [27,28]. Rather than claiming that GTST-MLD naturally extends into social complexity, the present study adopts a more bounded interpretation: the hierarchical logic of the GTST-MLD is conceptually compatible with CAS-informed analyses because both emphasize interdependent functional relationships. This compatibility does not imply empirical validation beyond the present case but provides a theoretically supported rationale for examining how a function-centered model can clarify dependencies within a single educational subsystem.

Building on this theoretical foundation, the GTST-MLD model helps illuminate how adaptation, feedback, and collective learning interact to produce system-level patterns within the Project Engineering course. While the present study remains strictly bound to a single-case application, the functional decomposition used here aligns with socio-technical perspectives that conceptualize learning environments as adaptive networks shaped by interactions among concepts, behaviors, and enabling conditions [26,43,77]. Within this bounded scope, the model clarifies how structural bottlenecks, redundancy patterns, and enabling functions emerge from interdependencies between TCs, pedagogical strategies, and LOs. This provides a structured analytical perspective that complements but does not replace existing CAS-oriented analyses of educational systems.