Experimental and Numerical Study on the Influence of Forest Spatial Structure on Rockfall Protection Efficacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Experiment

2.1.1. Experimental Platform

2.1.2. Experimental Scheme

2.1.3. Data Acquisition Process

2.2. Numerical Simulation

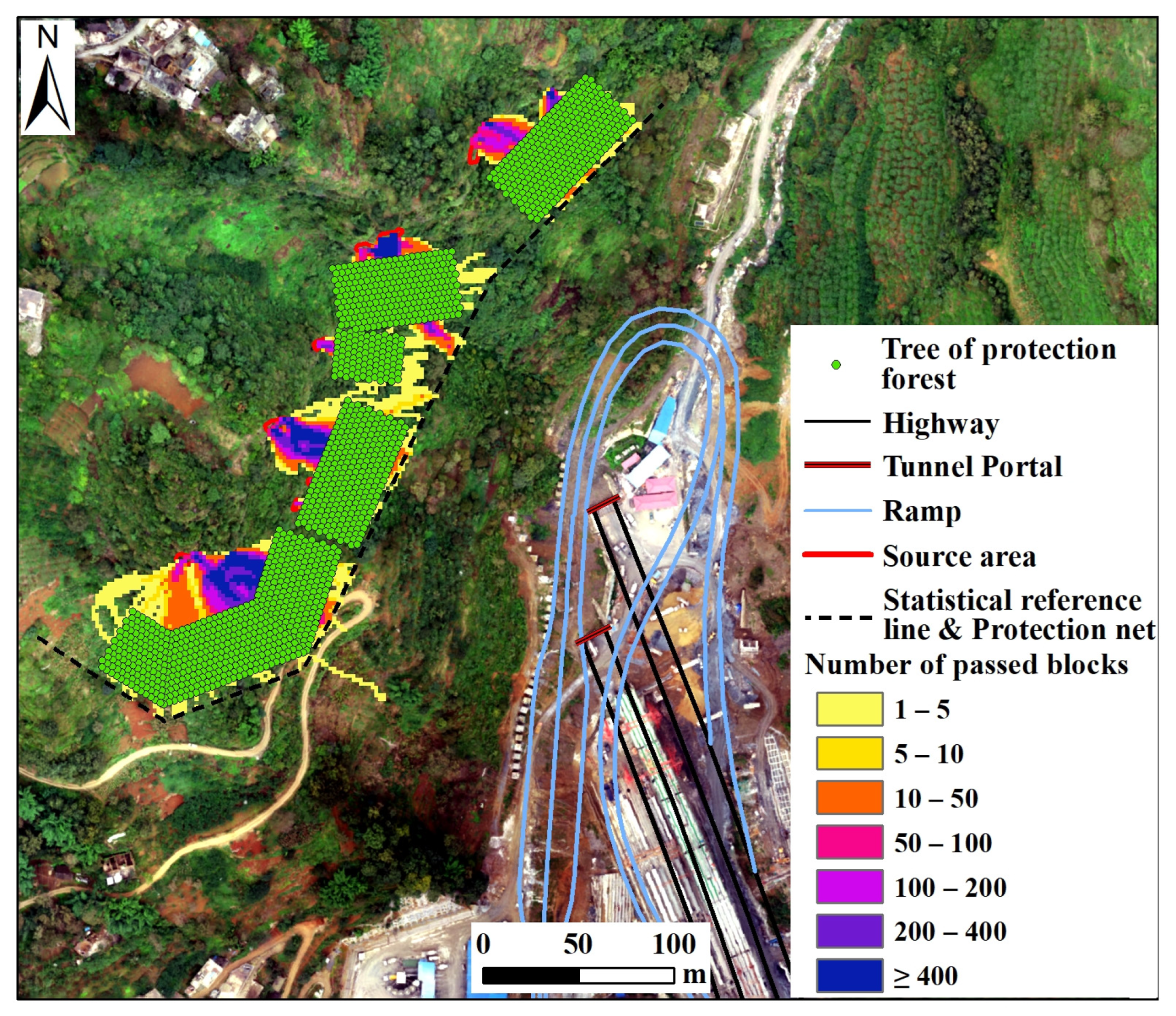

2.2.1. Rockfall Case

2.2.2. Simulation Parameters

3. Experimental Results

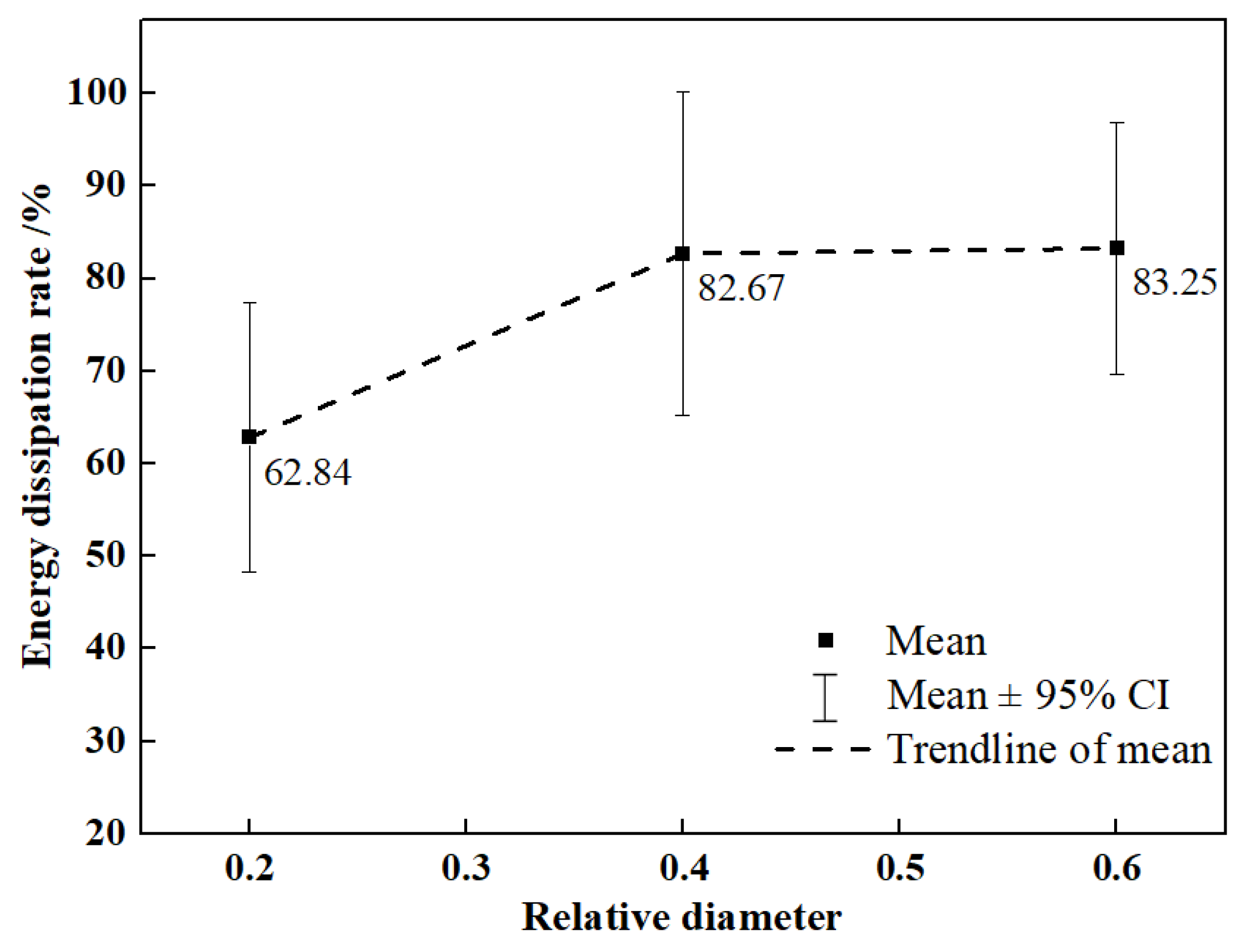

3.1. Different Tree Diameters

3.2. Different Plant Spacing

3.3. Different Arrangement Patterns

4. Protection Forest Scheme for the Rockfall Case

4.1. Simulation Without the Protection Forest

4.2. Protection Scheme Design and Simulation

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of Spatial Structure on Energy Dissipation

5.2. Engineering Applications

5.3. Limitations

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The protection efficacy of forests increases with tree diameter, while the gains plateau after the relative diameter reaches a certain threshold. For slopes with conditions analogous to this study, a relative diameter of 0.4 is recommended as the optimal parameter value for the protection forest design.

- (2)

- Protective effectiveness is enhanced by reducing plant spacing. However, the marginal gains exhibit a diminishing trend with closer spacing. The plant spacing design should integrate considerations of both tree growth space and economic constraints.

- (3)

- The rhombus arrangement enhances the probability of block-tree impact, achieving a substantially higher protective effectiveness compared to the square pattern.

- (4)

- An integrated protection scheme combining protection forests with flexible protection nets was designed based on the experimental results for the rockfall hazard at the Lehong Tunnel slope. Numerical simulations validated the scheme’s effectiveness, demonstrating its capacity to intercept nearly all falling blocks and dissipate 89.49% of the kinetic energy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| EDR | Energy Dissipation Rate |

| EDRVR | Variation Rate of Energy Dissipation Rate |

References

- Liu, X.; Hao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, L.; Wang, L. Study on improvement effect of herb plants on slope stability of dumping site. J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 2021, 17, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruqi, A.; Hall, C.; Kendall, A. Sustainability of bio-mediated and bio-inspired ground improvement techniques for geologic hazard mitigation: A systematic literature review. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1211574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, L.; Borgonovo, G.; Giorgi, A.; Bischetti, G.B. How to renew soil bioengineering for slope stabilization: Some proposals. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 15, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickovski, S.B. Re-Thinking Soil Bioengineering to Address Climate Change Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, M.J. Energy Absorption of Trees in a Rockfall Protection Forest. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reubens, B.; Poesen, J.; Danjon, F.; Geudens, G.; Muys, B. The role of fine and coarse roots in shallow slope stability and soil erosion control with a focus on root system architecture: A review. Trees 2007, 21, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, C.; Lopez-Saez, J.; Favillier, A.; Mainieri, R.; Eckert, N.; Trappmann, D.; Stoffel, M.; Bourrier, F.; Berger, F. Modeling rockfall frequency and bounce height from three-dimensional simulation process models and growth disturbances in submontane broadleaved trees. Geomorphology 2017, 281, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, C.; Khelidj, N.; Guisan, A.; Lischke, H.; Randin, C.F. A quantitative assessment of rockfall influence on forest structure in the Swiss Alps. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, S.; Dolf, F.; Kienholz, H. Rockfalls into forests: Analysis and simulation of rockfall trajectories—Considerations with respect to mountainous forests in Switzerland. Landslides 2004, 1, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancke, O.; Dorren, L.K.A.; Berger, F.; Fuhr, M.; Köhl, M. Implications of coppice stand characteristics on the rockfall protection function. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 259, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupire, S.; Bourrier, F.; Monnet, J.M.; Bigot, S.; Borgniet, L.; Berger, F.; Curt, T. The protective effect of forests against rockfalls across the French Alps: Influence of forest diversity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 382, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupire, S.; Bourrier, F.; Monnet, J.M.; Bigot, S.; Borgniet, L.; Berger, F.; Curt, T. Novel quantitative indicators to characterize the protective effect of mountain forests against rockfall. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranconi, C.; Frattini, P.; Sala, G.; Dattola, G.; Bertolo, D.; Sun, J.; Crosta, G.B. Accounting for the Effect of Forest and Fragmentation in Probabilistic Rockfall Hazard. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2023, 23, 2349–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, F.; Dorren, L.K. Principles of the tool Rockfor.net for quantifying the rockfall hazard below a protection forest. Schweiz. Z. Forstwes. 2007, 158, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Yang, H.; Liang, D.; Chen, L.; Qu, L.; Chen, C. Assessment and Mechanism Analysis of Forest Protection against Rockfall in a Large Rock Avalanche Area. Forests 2023, 14, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okura, Y.; Kitahara, H.; Sammori, T.; Kawanami, A. The effects of rockfall volume on runout distance. Eng. Geol. 2000, 58, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Uchida, I. Dependence of runout distance on the number of rock blocks in large-scale rock-mass failure experiments. J. For. Res. 2014, 19, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Li, L.; Wu, Y. Stochasticity of Rockfall Tracjectory Revealed by a Field Experiment Repeated on a Single Sample. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piteau, D.R.; Clayton, R. Proceedings of the meeting on rockfall dynamics and protective works effectiveness. In Computer Rockfall Model; ISMES Publication No. 90; ISMES: Bergamo, Italy, 1976; pp. 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, K.; Wong, R.; Wu, J. Coefficient of restitution and rotational motions of rockfall impacts. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2002, 39, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzi, O.; Giacomini, A.; Spadari, M. Laboratory Investigation on High Values of Restitution Coefficients. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2011, 45, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, W.; Zhou, J.; Pei, X. Rolling tests on movement characteristics of rock blocks. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 2007, 29, 1296–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, A.; Thoeni, K.; Lambert, C.; Booth, S.; Sloan, S.W. Experimental study on rockfall drapery systems for open pit highwalls. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2012, 56, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteriou, P.; Tsiambaos, G. Effect of impact velocity, block mass and hardness on the coefficients of restitution for rockfall analysis. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2018, 106, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Li, K.; Xie, Y.; Wang, Y. Contributions of Rock Mass Structure to the Emplacement of Fragmenting Rockfalls and Rockslides: Insights From Laboratory Experiments. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2020, 125, e2019JB019296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Liao, J.; He, Z. Experimental study on physical model of dynamic fragmentation process in high-locality rockfall. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2023, 42, 2164–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorren, L.K.A.; Berger, F.; Hir, C.L.; Mermin, E.; Tardif, P. Mechanisms, effects and management implications of rockfall in forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 215, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, S.; Stoffel, M.; Kienholz, H. Spatial and temporal rockfall activity in a forest stand in the Swiss Prealps—A dendrogeomorphological case study. Geomorphology 2006, 74, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorren, L.K.A.; Seijmonsbergen, A.C. Comparison of three GIS-based models for predicting rockfall runout zones at a regional scale. Geomorphology 2003, 56, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammer, W.; Brauner, M.; Dorren, L.K.A.; Berger, F.; Lexer, M.J. Evaluation of a 3-D rockfall module within a forest patch model. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorren, L.K.A.; Schaller, C.; Erbach, A.; Moos, C. Automated Delimitation of Rockfall Hazard Indication Zones Using High-Resolution Trajectory Modelling at Regional Scale. Geosciences 2023, 13, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigot, C.; Dorren, L.K.A.; Berger, F. Quantifying the protective function of a forest against rockfall for past, present and future scenarios using two modelling approaches. Nat. Hazards 2009, 49, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L. Risk Assessment for Luojiaqinggangling Rockfall. J. Eng. Geol. 2017, 25, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorren, L.K.A. Rockyfor3D (V6.0) Revealed—Transparent Description of the Complete 3D Rockfall Model. EcorisQ Manual. 2025. Available online: www.ecorisq.org (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Stoffel, M.; Wehrli, A.; Kühne, R.; Dorren, L.K.A.; Perret, S.; Kienholz, H. Assessing the protective effect of mountain forests against rockfall using a 3D simulation model. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 225, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, C.; Dorren, L.K.A.; Stoffel, M. Quantifying the effect of forests on frequency and intensity of rockfalls. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Qi, X.; Wei, T. Damage mechanism of rockfall barriers under strong impact loading. Eng. Machenics 2016, 33, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Organization for Technical Approvals (EOTA). Guideline for European Technical Approval of Falling Rock Protection Kits—ETAG 27; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moos, C.; Fehlmann, M.; Trappmann, D.; Stoffel, M.; Dorren, L. Integrating the mitigating effect of forests into quantitative rockfall risk analysis—Two case studies in Switzerland. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 32, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzner, M.; Gutheil-Knopp-Kirchwald, G.; Kreimer, E.; Kirchmeir, H.; Huber, M. Gravitational natural hazards: Valuing the protective function of Alpine forests. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 80, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorren, L.K.; Maier, B.; Putters, U.S.; Seijmonsbergen, A.C. Combining field and modelling techniques to assess rockfall dynamics on a protection forest hillslope in the European Alps. Geomorphology 2004, 57, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zone Number | Rg70 a | Rg20 | Rg10 | Soiltype b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | 0 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 5 |

| ② | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 3 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Block size (m3) | 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 |

| Calculation times | 100 |

| Block shape/blshape | Cuboid/1 |

| Rock mass density (kg/m3) | 2800 |

| Without Protection Forest | With Protection Forest | EDR/% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Reaching Blocks | Total Kinetic Energy /kJ | The Maximum Kinetic Energy of the Blocks/kJ | Number of Reaching Blocks | Total Kinetic Energy /kJ | The Maximum Kinetic Energy of the Blocks/kJ | |

| 5815 | 96,355.9 | 161.8 | 712 | 10,127 | 72.1 | 89.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Zhou, J.; Sun, J.; Shao, K.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Influence of Forest Spatial Structure on Rockfall Protection Efficacy. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312829

Liu H, Liu C, Zhou J, Sun J, Shao K, Guo Z, Wang X. Experimental and Numerical Study on the Influence of Forest Spatial Structure on Rockfall Protection Efficacy. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312829

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Haiyang, Chunling Liu, Jian Zhou, Juanjuan Sun, Kuiyu Shao, Zhaocheng Guo, and Xueliang Wang. 2025. "Experimental and Numerical Study on the Influence of Forest Spatial Structure on Rockfall Protection Efficacy" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312829

APA StyleLiu, H., Liu, C., Zhou, J., Sun, J., Shao, K., Guo, Z., & Wang, X. (2025). Experimental and Numerical Study on the Influence of Forest Spatial Structure on Rockfall Protection Efficacy. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12829. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312829