The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

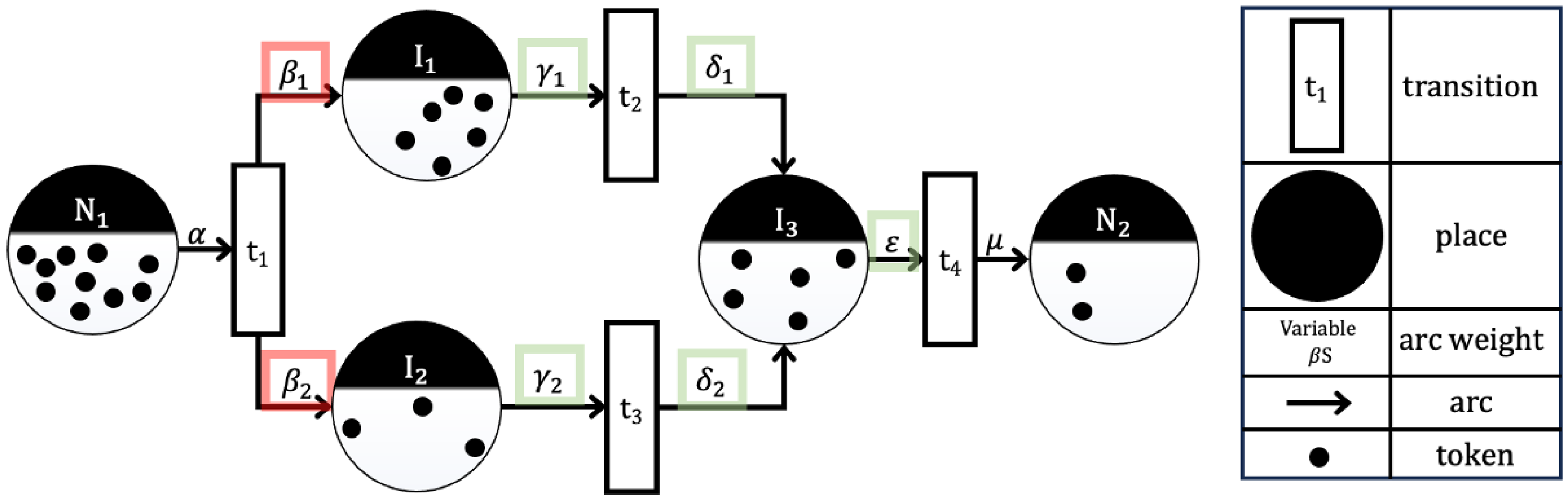

2. A Brief Overview of Petri Nets

- P is the finite set of places (one type of vertex in the graph).

- T is the finite set of transitions (the other type of vertex in the graph).

- A is the set of arcs (edges) from places to transitions and from transitions to places in the graph .

- w: A → {1, 2, 3, …} is the weight function on the arcs.

- x is a marking of the set of places P; ] is the row vector associated with x. The term refers to marking of x at state i. Note that is the initial state (also known as marking).

3. Next-Generation Matrix for Petri Nets

3.1. Next-Generation Matrix for Ordinary Differential Equations

- (1)

- If , then for . Each subsequent function represents a transfer of individuals, thus they are all non-negative.

- (2)

- If then . In particular, if , then for . If a compartment is empty, then there can be no transfer of individuals out of the compartment.

- (3)

- if . No infectious population enters a non-infectious compartment.

- (4)

- If then and for . This states that if the population is disease-free, it stays disease-free. Meaning no density-independent infectious population immigrates in. This becomes important when dealing with patch models, as seen in Section 4.7.

- (5)

- If is set to zero, then all eigenvalues of have negative real parts, where is the derivative evaluated at the disease free equilibrium (DFE), .

3.2. Constructing the Next-Generation Matrix for Petri Nets

- For F: For any infected place , we define as the rate of all new infections entering , which is the net inflow from all infection transitions . The matrix is composed of these terms.

- For V: Conversely, represents the net rate of all other transfers affecting place . This is calculated as the rate of all outflows from (to any place) minus the rate of all inflows to from other infected places .

- (A1)

- If a place contains a non-negative number of tokens , then the number of tokens that can be added to or removed from any place by any transition is non-negative. Specifically, if a transition is enabled (based on its input places and corresponding markings), the number of tokens removed from the input places and added to the output places must be non-negative. By definition of Petri Nets, the assumption is inherently preserved across all Petri Net structures. This is due to the stipulation that the number of tokens in each place must remain non-negative at all times. Additionally, transitions in a Petri Net operate in a manner that ensures the non-negativity of tokens, effectively maintaining this essential characteristic.

- (A2)

- If the marking of a place is zero (i.e., ), then no transition can consume tokens from place . Specifically, if a place is empty (i.e., no tokens are present in the corresponding place), no transition can have it as an input. This ensures that no “removal” of individuals (tokens) from an empty place occurs. Again, the definition of Petri Net preserves this assumption for all Petri Nets, as a transition can not fire if an input place has less tokens than the corresponding arc weight. If a place has no tokens (individuals), no transition can remove tokens from that place.

- (A3)

- If place corresponds to a non-infectious place, then no transition can place tokens into this place from a transition that represents infection occurring or remaining. No transition should be able to fire that would place tokens into non-infectious places from a transition that represents infection occurring or remaining.

- (A4)

- If the marking of a place indicates a disease-free population (i.e., there are no tokens representing infected individuals in this marking), then no transition can fire that would result in tokens (representing infected individuals) being moved to an infected place. If a place has a disease-free marking, no transitions can place tokens in it that correspond to infected individuals (i.e., no “infection” transition should have this place as an output if it is currently disease-free).

- (A5)

- If is set to 0, then all eigenvalues of the Jacobian of the infected subsystem at the DFE have negative real parts. In terms of the Petri Nets, this means that when no new infections occur, that means all transitions transferring tokens from non-infected to infected places are disabled, the marking of every infected place will asymptotically decay to zero. Formally, let the state vector be partitioned as , where are the infected places and are the non-infected places. Define the infected subsystem as , where collects all token inflows into infected places from non-infected places and collects all other token flows (recoveries, deaths, or transfers among infected places). Then, at the DFE , with , the Jacobian matrixmust be Hurwitz, which means all eigenvalues have strictly negative real parts. Note that D is the derivative operator. Equivalently, should be a nonsingular M-matrix, ensuring that small perturbations in the infected places decay over time. In terms of a biological application, this assumption guarantees that in the absence of new infections, any initial infection will die out, preserving the disease-free equilibrium.

4. Case Studies

4.1. SIRS

4.2. SEIR

4.3. SEEIR

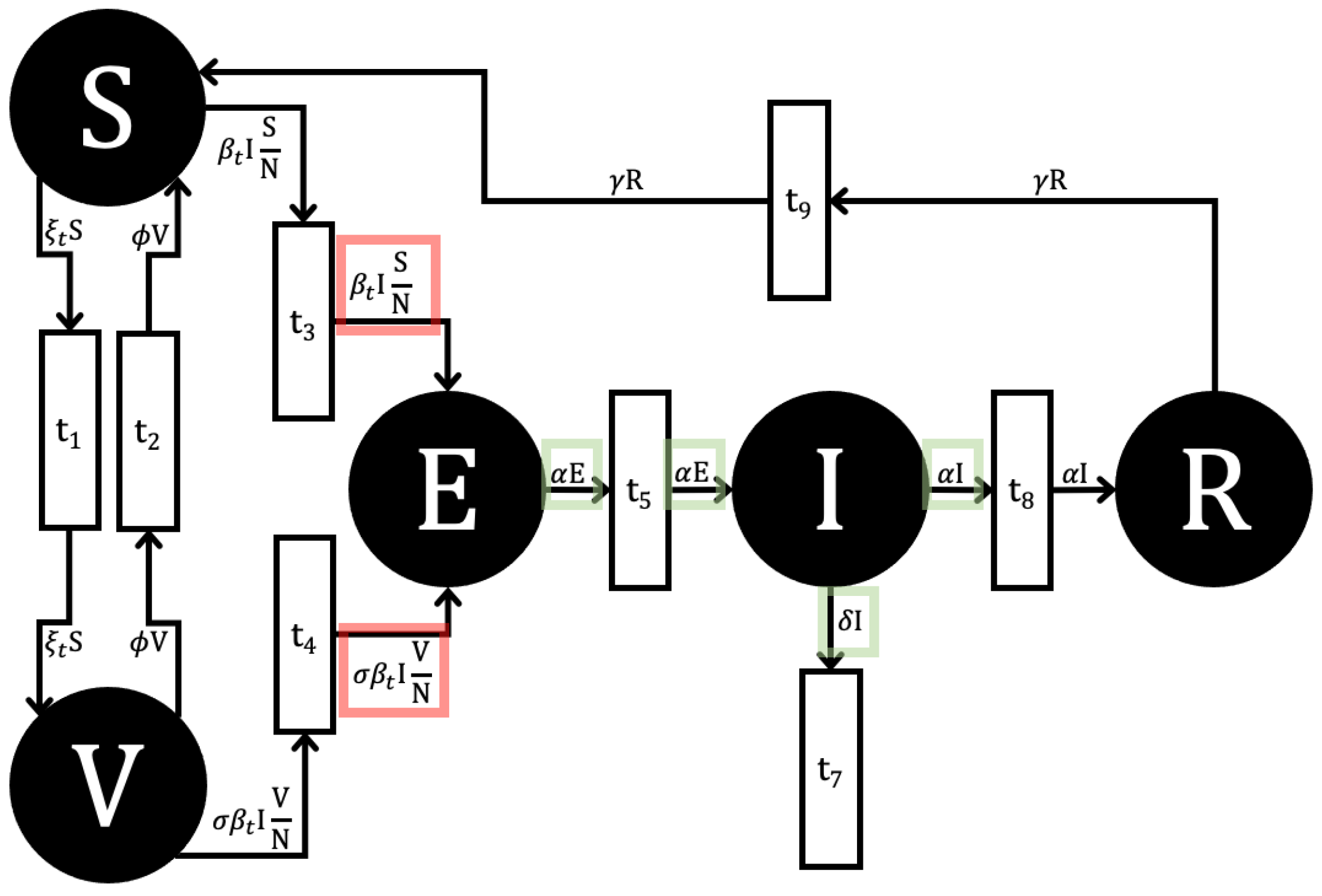

4.4. SVEIR

4.5. Basic COVID-19 Model

4.6. Nonlinear System

4.7. Patch System Overview

Two Patch System

4.8. SIR Vector-Borne Model

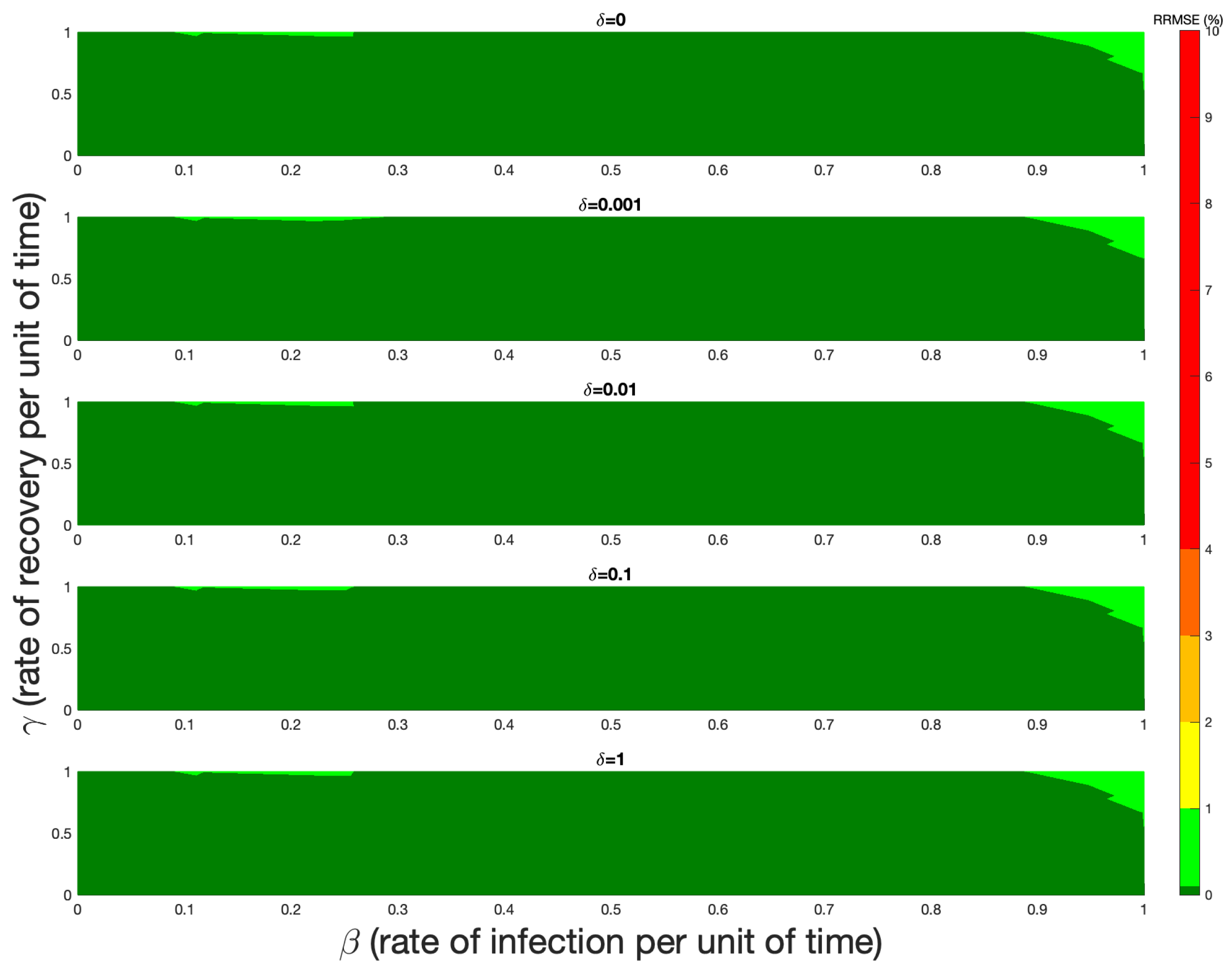

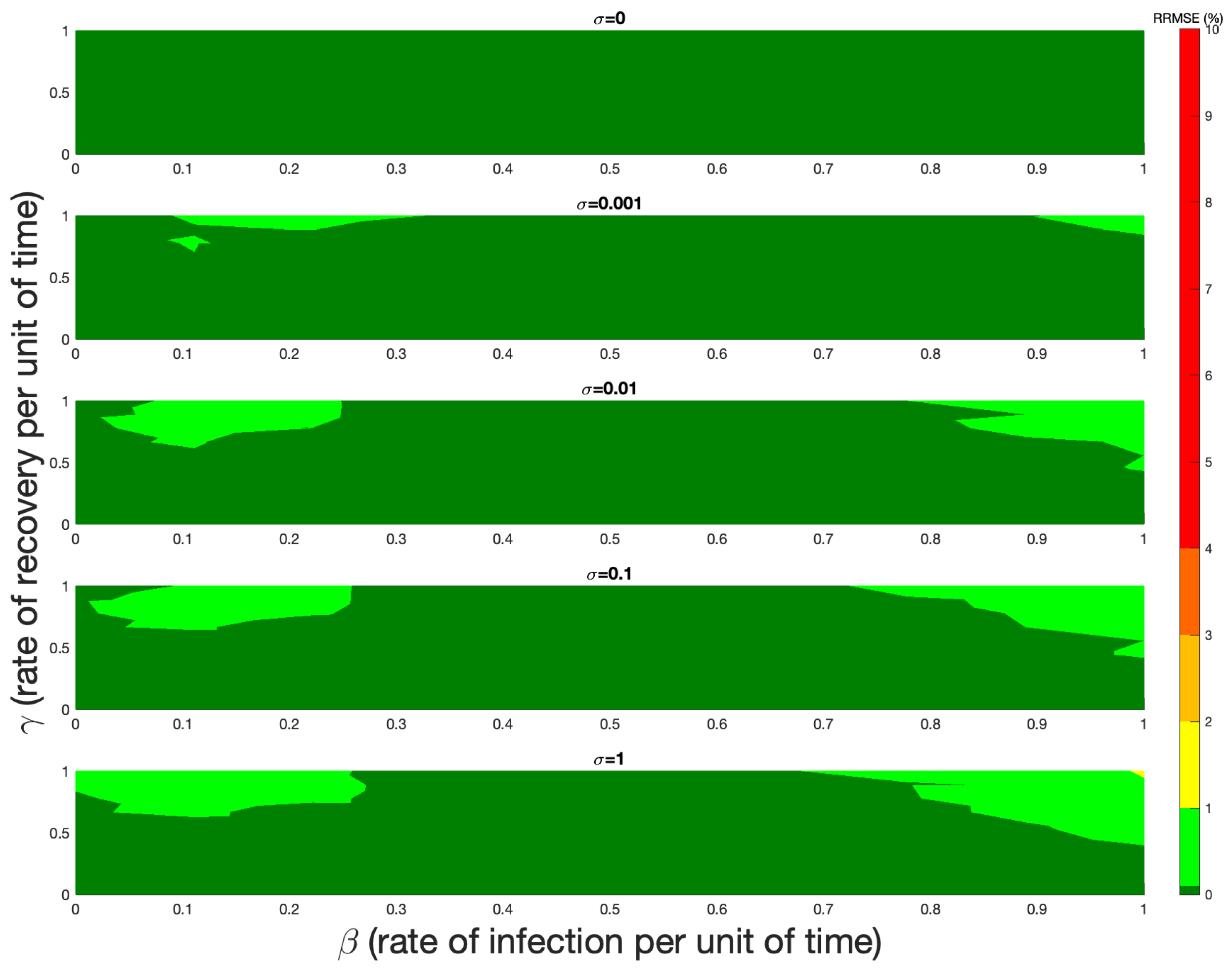

5. Numerical Verification

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reckell, T.; Sterner, B.; Jevtić, P.; Davidrajuh, R. A Numerical Comparison of Petri Net and Ordinary Differential Equation SIR Component Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.10019v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segovia, C. Petri nets in epidemiology. J. Math. Biol. 2025, 91, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Rubin, D.; Altman, R.B. Using Petri net tools to study properties and dynamics of biological systems. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2005, 12, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaradonna, S.; Jevtić, P.; Sterner, B. MPAT: Modular Petri Net Assembly Toolkit. SoftwareX 2024, 28, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahi-Jaber, N.; Pontier, D. Modeling transmission of directly transmitted infectious diseases using colored stochastic Petri nets. Math. Biosci. 2003, 185, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Xie, P.; Tang, Z.; Liu, F. Modeling and analyzing transmission of infectious diseases using generalized stochastic petri nets. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Yu, W.; Hao, F. A CPN-based information propagation model in Online Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th International Conference on Ubiquitous Computing and Communications (IUCC/CIT/DSCI/SmartCNS), London, UK, 20–22 December 2021; pp. 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, S.; Gilbert, D.; Heiner, M. From Epidemic to Pandemic Modelling. Front. Syst. Biol. 2022, 2, 861562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libkind, S.; Baas, A.; Halter, M.; Patterson, E.; Fairbanks, J.P. An algebraic framework for structured epidemic modelling. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, K. The estimation of the basic reproduction number for infectious diseases. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 1993, 2, 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; Metz, J.A.J. On the definition and the computation of the basic reproduction ratio R0 in models for infectious diseases in heterogeneous populations. J. Math. Biol. 1990, 28, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckell, T.; Sterner, B.; Jevtić, P. The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delamater, P.L.; Street, E.J.; Leslie, T.F.; Yang, Y.T.; Jacobsen, K.H. Complexity of the basic reproduction number (R0). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P. Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: Model Building, Analysis and Interpretation; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, O.; Heesterbeek, J.; Roberts, M.G. The construction of next-generation matrices for compartmental epidemic models. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 873–885. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002, 180, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hethcote, H.W. The mathematics of infectious diseases. SIAM Rev. 2000, 42, 599–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, F.; Van den Driessche, P.; Wu, J. Mathematical Epidemiology; Lecture Notes in Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baez, J.C.; Biamonte, J. Quantum techniques for stochastic mechanics. arXiv 2012, arXiv:1209.3632. [Google Scholar]

- Cassandras, C.G.; Lafortune, S. Introduction to Discrete Event Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martcheva, M. An Introduction to Mathematical Epidemiology; Texts in Applied Mathematics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiner, M.; Koch, I.; Will, J. Standardised Petri nets for systems and synthetic biology. In Transactions on Computational Systems Biology XI; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 38–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kermack, W.O.; McKendrick, A.G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Contain. Pap. A Math. Phys. Character 1927, 115, 700–721. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, K.L. Functional differential equations close to differential equations. Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 1966, 72, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Cori, A.; Ferguson, N.M.; Fraser, C.; Cauchemez, S. A new framework and software to estimate time-varying reproduction numbers during epidemics. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2013, 178, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugalia, S.; Tripathi, J.P.; Wang, H. Estimating the time-dependent effective reproduction number and vaccination rate for COVID-19 in the USA and India. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 4673–4689. [Google Scholar]

- Gumel, A.B.; Iboi, E.A.; Ngonghala, C.N.; Elbasha, E.H. A primer on using mathematics to understand COVID-19 dynamics: Modeling, analysis and simulations. Infect. Dis. Model. 2021, 6, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohith, G.; Devika, K. Dynamics and control of COVID-19 pandemic with nonlinear incidence rates. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 101, 2013–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichara, D.; Iggidr, A. Multi-patch and multi-group epidemic models: A new framework. J. Math. Biol. 2018, 77, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedajo, A.; Bole, B.K.; Koya, P.R. Analysis of SIR mathematical model for malaria disease with the inclusion of infected immigrants. IOSR J. Math. 2018, 14, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Obadia, T.; Haneef, R.; Boëlle, P.Y. The R0 package: A toolbox to estimate reproduction numbers for epidemic outbreaks. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2012, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelle, P.Y.; Obadia, T. R0: Estimation of R0 and Real-Time Reproduction Number from Epidemics. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/R0/index.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- White, L.F.; Wallinga, J.; Finelli, L.; Reed, C.; Riley, S.; Lipsitch, M.; Pagano, M. Estimation of the reproductive number and the serial interval in early phase of the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic in the USA. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2009, 3, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reckell, T.; Sterner, B.; Jevtić, P. The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312827

Reckell T, Sterner B, Jevtić P. The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312827

Chicago/Turabian StyleReckell, Trevor, Beckett Sterner, and Petar Jevtić. 2025. "The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312827

APA StyleReckell, T., Sterner, B., & Jevtić, P. (2025). The Basic Reproduction Number for Petri Net Models: A Next-Generation Matrix Approach. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12827. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312827