Abstract

A hollow fiber-supported polymeric mixed-matrix membrane, consisting of a Pebax-1657 matrix and graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) fillers as the selective layer, was tested for CO2/CH4 gas separation at transmembrane pressures up to 30 bar(a). Using a custom, novel, membrane module, we simultaneously performed permeability/selectivity and in situ electric impedance spectroscopy measurements. This in situ technique is proposed here for the first time. Furthermore, stable mixed-gas selectivities, for 10% CO2 in CH4 gas, reaching up to 61.4 (M0) and 68.5 after heat treatment (M2) were observed at 20–30 bar(a), whereas the stressed state (M1) dropped to ~22. Throughout the whole procedure of the three (initial, degraded, and restored) membrane testing assessments, a gradual decline in gas permeability coupled with a corresponding increase in the membrane’s AC resistance, due to membrane compaction, was evident. More specific, the membrane’s AC resistance, R1, increased from ~96–147 ΜΩ (M0) to ~402–435 ΜΩ (M1) and ~5390–5700 ΜΩ (M2), while the peak-phase frequency fp decreased from ~1.25 kHz (M0) to ~340 Hz (M1) and ~115 Hz (M2). Overall, this work proposes a new tool/method for connecting membrane’s deterioration phenomena with AC resistance and demonstrates that a facile heat treatment can restore selectivity following compaction, despite the absence of full permeance recovery.

1. Introduction

Natural gas (NG) sweetening/upgrading is a process where, among other acid gas contaminants, CO2 is removed from CH4 [1]. The utilization of membranes in this process is gradually gaining market share, as more efficient polymeric membranes are becoming commercialized [2,3,4]. At the same time, this sweetening process becomes more complicated in the case of the biogas upgrading units, where the existence of H2O and H2S, among other gases, requires further processing steps or/and more stable membrane materials [5,6,7]. Contemporary advanced NG-upgrading plants are designed with a carbon capture and storage (CCS) facility, where CO2 is compressed to become geo-sequestered immediately following separation [8,9]. It is known that high pressure, above the critical pressure of 72.8 atm (at 31 °C), is needed for the CO2 sequestration stage since the high (600 kg/m3) density of supercritical fluid enables more CO2 to be sequestered [10]. Furthermore, if the separated/recovered CO2 is compressed to supercritical conditions, then the produced CO2 stream can also be used for the enhanced oil recovery process in the upstream oil industry [9]. Therefore, given that the NG feed stream is close to a high well-pressure, compressing the permeate side of a CO2-selective membrane for CO2/CH4 separation to a pressure close to the high-pressure level needed for sequestration leads to reduced transmembrane pressure. By decreasing the operating transmembrane pressure, more membrane materials can be added to the candidate list for the NG sweetening process.

In this respect, the use of less pressure-withstanding, but highly CO2-selective, polymeric membranes, such as those based on polyether-block-amide elastomers marked under tradenames like PEBAX (Arkema) or VESTAMID E (Evonik Industries) is becoming favored [11]. Nonetheless, membrane intrinsic (contaminants and crystallization) and extrinsic (pressure, heat, moisture, weathering, etc.) aging- [12,13], plasticization-, and compaction- [14] resistance testing and improvement remain important challenges for any material intended for use in NG sweetening applications [4]. In particular, pristine Pebax-1657 (60 wt% poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) and 40 wt% polyamide-6 (PA6)) membranes, which are examined in this work, given their high CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 selectivities, are known to suffer severe irreversible compaction when exposed to transmembrane pressures of more than 6 bar(a). However, the addition of nano-filler materials to form mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs) has been demonstrated to significantly enhance the pressure tolerance of this kind of membranes [15], along with an improvement of the resistance against aging phenomena [16,17,18,19]. The addition of nanofillers into membrane matrices enhances the pressure tolerance and provides resistance to aging phenomena. This can maintain selectivity at higher pressures while enabling thinner selective layers. As the polymeric CO2-selective membranes are rarely tested under elevated transmembrane pressures, only a few works report data up to ~25 bar for selected polymers [15,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

At the same time, given the fact that a critical issue in membrane technology is the development of techniques for the in situ monitoring of the operating membrane condition [27,28], this work introduces a technique of in situ electrical resistance measurement during membrane operation. In gas separation membrane technology, a critical challenge lies in the real-time detection of performance degradation, such as compaction or aging, during continuous operation [29,30]. Conventional monitoring methods, which rely primarily on permeance or selectivity measurements, typically require controlled feed conditions or system interruptions and often detect changes only after significant deterioration has occurred. In contrast, in situ electrical resistance measurement offers a non-invasive, continuous diagnostic tool capable of detecting structural or compositional changes within the membrane matrix as they develop [31,32]. This enables earlier identification of degradation phenomena, independent of gas transport measurements, providing a more direct understanding of the membrane’s physical condition. By introducing this approach, the present work contributes a valuable method for enhancing operational reliability and predictive maintenance in advanced gas separation systems.

So far, such techniques of in situ measurement of a second parameter other than permeability have mainly been developed for membranes in water-treatment processes and rely on optical means. Direct observation (DO), using a camera integrated with a light microscope for continuous monitoring of membrane fouling, and the application of confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) in membrane reactors [33,34] are two examples of this kind. However, these non-destructive optical techniques are limited to low-pressure systems and need specific microorganisms producing fluorochromes (e.g., green fluorescent protein) in order to be detected and visualized [33,35]. Therefore, at high-pressure conditions, other ex situ destructive imaging techniques, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and helium-ion microscopy (HIM), have been applied [33,36,37]. On the other hand, in the case of membrane-based gas separation processes, the few existing studies refer to in situ measurements of gas permeability, while a membrane functions as an ion conductor in an electrochemical cell. Specifically, Gode et al. [38], in 2002, reported a new method for studying the problem of the permeation of H2 and O2 through proton-conducting membranes using a cylindrical microelectrode as an in situ method to study the transport properties of H2 and O2 close to real fuel cell operating conditions at an elevated temperature and a wide range of relative humidities. In another work of Lazik et al. [39], in 2009, a tubular membrane was used as part of a developed sensor for in situ monitoring of gases in a solid, while a similar approach was also reported by Craster and Jones [40], in 2019, who developed a novel experimental apparatus and methodology to quantify the transport of CO2 and chloride ions through polymer membranes under varying conditions of temperature (up to 100 °C) and pressure (up to 690 bar) for prolonged periods of time. Finally, it must be noted that there is no literature report yet, regarding in situ measurements of an electrical property of a membrane matrix during a gas permeability measurement in order to correlate these two physical quantities with each other. Based on recent reported observations in the work of Zhao et al. [41], who noticed a pressure-induced change in electric conductivity for Pebax-graphene composites, the examination of this change in a Pebax-based mixed-matrix membrane operated at elevated pressure could possibly be a way of in situ defect, ageing, and compaction phenomena monitoring. Given the limited research on polymeric membranes under high pressures, particularly with in situ characterization techniques, this study aims to provide valuable insights.

Although the incorporation of nanomaterials in a membrane matrix significantly enhances its resistance to aging phenomena, it cannot completely prevent them. Additionally, exposure to CO2 pressures up to ~20 bar can affect the rearrangement of polymer chains, positioning GNPs as potential “sensors” for detecting changes within the mixed-matrix membrane. GNPs are a promising and rapidly carbon nanomaterial filler due to their facile production easily and low manufacturing cost [42,43]. They are composed of ultra-thin, multilayered stacks of graphene sheets in a platelet-like structure exhibiting outstanding mechanical, electrical, and thermal properties. These nanomaterials consist of multiple graphene layers, typically measuring from a few to several tens of nanometers in thickness [44,45,46]. Due to their unique properties, including high surface area and exceptional electrical conductivity, GNPs are highly responsive to structural changes in the polymer matrix. These changes can be identified by monitoring alterations in the electrical resistance of the membrane, enabling GNPs to serve as an effective tool for real-time sensing and diagnosing of structural and performance fluctuations. This ability is especially beneficial for applications that demand continuous monitoring of membrane integrity and functionality under dynamic operational conditions. One such example is natural gas processing, where fluctuations in pressure, temperature, and gas composition can accelerate membrane compaction or aging. In such environments, real-time insight into the membrane’s structural state is crucial for ensuring process stability, maintaining separation performance and minimizing operational disruptions. In situ electrical resistance measurement enables operators to detect early signs of degradation without interrupting the process, offering a practical advantage over conventional performance-based monitoring techniques.

This work proposes the development of a specialized membrane cell for in situ investigations of both gas permeability and AC resistance properties. By analyzing experimental data, the AC resistance properties, resulting from structural modifications in the polymer composite membrane, are correlated with gas permeation and CO2/CH4 selectivity performance. We believe that this topic warrants further investigation to develop sustainable solutions for specific challenges in membrane technology. These solutions could enhance the longevity, efficiency, and selectivity of membranes, leading to more reliable and cost-effective applications in fields such as gas separation, water purification, and energy storage. Such advancements are crucial for addressing the increasing demand for high-performance membranes across various industrial processes. Additionally, although permeability loss can be directly quantified through permeate flow measurements using a mass flow meter, particularly for non-conductive membranes, this method captures only the outcome of deterioration rather than the underlying mechanisms. In contrast, electrical resistance measurements provide insight into structural or physicochemical changes within the membrane, such as compaction or densification. While this approach offers only an indirect correlation with permeability, it enables the early detection of degradation before significant performance decline. Therefore, it serves as a valuable complementary tool for diagnosing membrane deterioration and enabling predictive maintenance under dynamic or long-term operating conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mixed-Matrix Membrane Preparation

A porous P84 (BTDA-TDI/MDI co-polyimide), GNP [47] mixed-matrix hollow fiber support was prepared by dry-jet wet spinning process from a dope solution with GBL/NMP mixed solvent according to a previously reported method/technique [18]. The complete process for preparing GNPs, including oxidative surface modification (oxidized GNPs), has been detailed in our previous work [47]. In brief, oxidized GNPs were prepared through a water-based milling process using selected surfactants to facilitate dispersion. The graphite oxide precursor, composed of multilayer graphene oxide sheets, was exfoliated in liquid phase using GBL as the dispersion medium to obtain few-layer porous GNPs. Following exfoliation, they underwent an acidic oxidative surface-modification step, improving their compatibility and dispersibility within the polymer solution. Regarding the mixed-matrix membrane preparation, the P84 co-polyimide was first dried at 120 °C under vacuum, while oxidized GNPs were pre-dispersed in GBL, diluted into the NMP/GBL solvent mixture, sonicated, and subsequently mixed with the polymer under mechanical stirring at 50 °C to produce a homogeneous spinning dope. The resulting dope was then ultrasonicated, filtrated, and degassed overnight at 50 °C, before being co-extruded with a 70/30 (v/v) GBL/H2O bore fluid through a tube-in-orifice spinneret. The nascent fibers passed through an 11 cm air gap into a water coagulation bath were thoroughly washed, post-treated in ethanol to remove residual solvent, and finally hung to dry at room temperature prior to use. The full experimental parameters are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental parameters of spinning P84-based HFs.

Experimental data, including FTIR, CA (contact angle), and other analyses of the Pebax® 1657/GNP composite matrices, can be found in the previous work by Vasileiou et al. [48].

Subsequently, the support was dip-coated with a Pebax-1657/GNP mixed-matrix separation layer by 5 min immersion in a 3 wt% Pebax and 0.7% w/w (dry) GNP solution with a 70/30 (wt%) ethanol/water mixed solvent, followed by 24 h evaporation under ambient conditions.

2.2. In Situ Gas Separation—Impedance Measurements

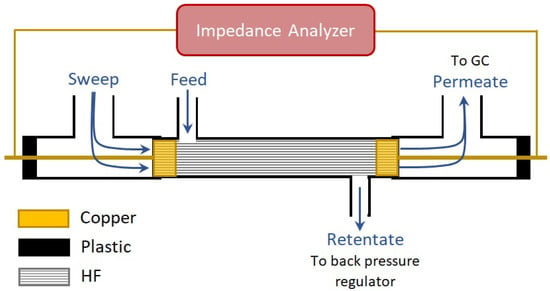

For the in situ study of gas permeances and electric impedance measurements, a new novel cell was designed and constructed. The hollow fiber membrane cell is schematically presented in Figure 1. It consists of conductive and non-conductive parts, namely, a non-conductive plastic housing and T-connectors, with hollow fiber ends bound to brass cylinders with drilled holes for HFs and extending central spikes for electric contacts. More specifically, four HF membranes, each with a length of 9.4 cm, forming an active membrane area of 11.8 cm2, were connected to the brass terminals using a gas-tight Agilent Torr Seal epoxy resin sealant. Additionally, an electrically conductive silver paste adhesive was applied after epoxy resin curing to ensure reliable ohmic contacts between brass and the HFs.

Figure 1.

Schematic of setup for gas permeation tests with a special module, enabling simultaneous measurement of electric impedance during membrane operation.

10% v/v CO2 in CH4 gas mixture was continuously fed with 100 cc(STP)/min as feed stream to the membrane and He with 3 cc(STP)/min as sweep gas to the permeate side. The gas mixture permeating through the membrane was carried by the sweep gas and directed to a bubble flow meter positioned on the permeate side downstream of the membrane module. This enabled continuous and accurate measurement of the permeating flow rate, which was used to calculate gas permeance based on the specified membrane area, transmembrane pressure difference, and feed composition. A Bronckhorst back pressure regulator controlled the pressure at the retentate exit of the membrane to maintain constant levels ranging from 1 to 30 bar(a), while permeate side was kept at atmospheric pressure. An SRI 8610C gas chromatograph, equipped with a porous polymer HayeSep DB, 80–100 mesh adsorbent in a packed column, was employed for CO2 (TCD) and CH4 (FID) gases monitoring at permeate exit [49]. Simultaneously, the impedance analyzer “Dielectric Thermal Analysis System DETA-SCOPE®” of ADVISE was used for performing electric impedance spectroscopy measurements on the membrane material during membrane operation at 298 and 313 K in the frequency range 1 Hz–175 kHz with 10 V amplitude AC voltage.

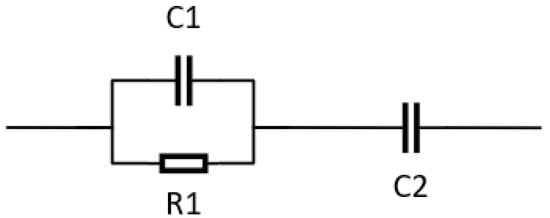

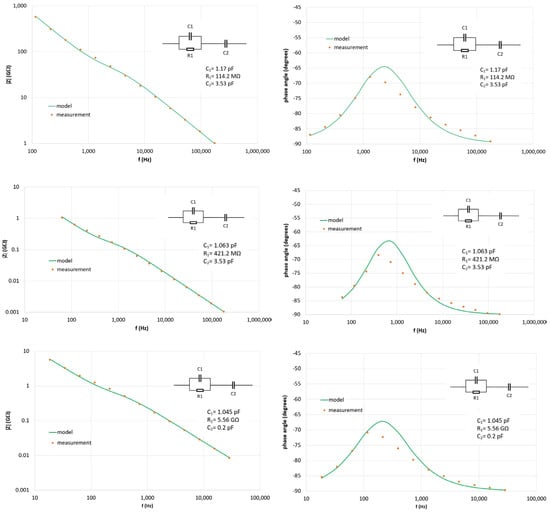

The real and imaginary components of complex impedance were calculated, and these data were fitted, using LEVMW fitting software (version 8.13) based on analysis by Ross McDonald [50], to a model-equivalent circuit consisting of geometric capacitance C2 in series connection with a loop comprising the parallel resistance R1 and parallel capacitance C1 (Figure 2). The geometric capacitance represents a non-dispersive, purely dielectric capacitance associated with the bulk geometry of the polymer specimen and not with the electrochemical or relaxation processes that are described by parallel components R1 and C1 and vary during each test.

Figure 2.

Equivalent circuit model used for fitting impedance spectroscopy data.

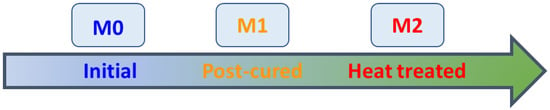

Three different states of the same membrane module were studied: M0, M1, and M2 (Figure 3). M0 corresponds to the module initially, with fresh follow fiber membranes, providing a baseline for performance. M1 represents the same module after being stored at ambient temperature for 1 month, followed by re-operation for 12 h at 28 bar(a), simulating typical operational stress and potential compaction. M2 corresponds to the module status after undergoing a final “healing” procedure, involving thermal treatment to restore selectivity. In this step, the membrane was thermally treated at 40 °C for 5 days under a continuous He flow, a protocol chosen to gently enhance polymer chain mobility without affecting the crystalline domains of Pebax. This mild relaxation step is consistent with the literature report by Tena et al. [51], which shows that low-temperature annealing of Pebax-based membranes promotes microstructural reorganization and partial recovery of selective transport pathways. These three membrane states were chosen to represent practical operational cycles and to assess the extent of membrane performance degradation as well as the effectiveness of recovery procedure.

Figure 3.

Three different states of the studied membrane module.

Specifically, the as-prepared membrane (state M0) was measured in the transmembrane pressure range 20–30 bar(a) (T = 298 K), and then the membrane module was stored for one month in a sealed desiccator placed in a dark cabinet at ambient temperature. Afterwards, identical measurements were performed, starting at the highest pressure of 30 bar(a) (12 h of operation), to be evaluated any deterioration in membrane performance (state M1). Finally, the same membrane sample was measured again in the same 20–30 bar(a) pressure range after a process of membrane “healing”, achieved by mild heating to 313 K for a duration of 5 days mostly at zero transmembrane pressure under He flow (state M2). Within these 5 days, two short time measurements were performed at 2 and 4 bar(a), while after cooling the membrane to 298 K, two additional short measurements at the same two pressures were performed.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gas Permeance/Selectivity Measurements

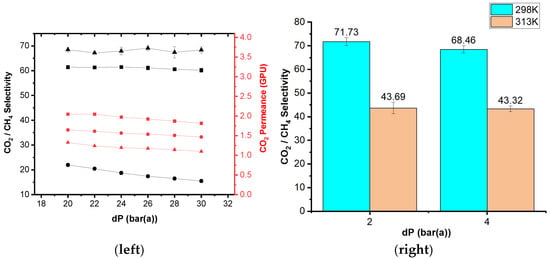

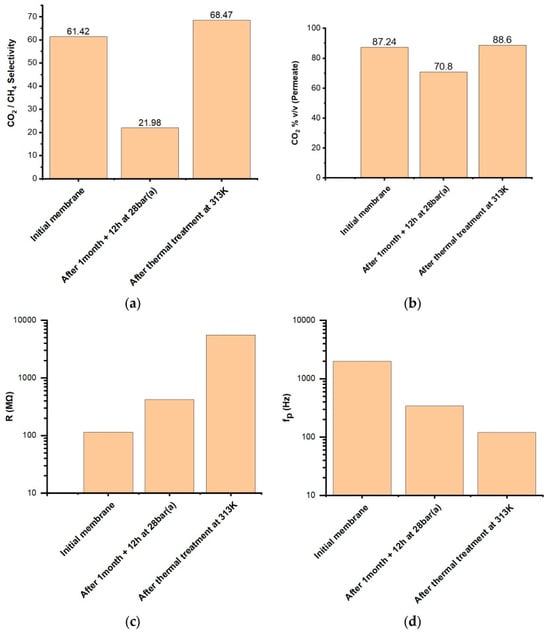

As shown in Figure 4, the mixed-gas CO2/CH4 selectivities of the M0, M1, and M2 membrane states were measured to be approximately 61, 22, and 68, respectively, denoting that after the deterioration of the initial membrane, the mild heating “healing” step not only restored selectivity but even slightly improved it. A similar trend is reported by Pazani and Aroujalian, who prepared PES-supported flat-sheet Pebax-1657 MMMs with graphene or graphene oxide (GO) and, under single-gas CO2/N2 testing (25 °C, 4–8 bar) using a constant-volume/variable-pressure method, reported increased CO2 permeability (up to ~59 Barrer at 0.5 wt% GO) and ideal CO2/N2 selectivity (up to ~121 at 1 wt% GO), further supporting that graphene-based fillers enhance selectivity in Pebax-1657 [17]. Furthermore, M0 and M2 membrane states exhibited excellent stabilities across varying high transmembrane pressures, whereas the selectivity of M1 dropped from 22 to 15 as pressure increased from 20 to 30 bar(a). The sustained high selectivity values for M0 and M2 membrane states throughout the entire high- (Figure 4(left)) and low- (Figure 4(right)) pressure range can be attributed to the high separation layer thickness, along with the mechanical stabilization provided by the GNP filler in both the separation layer and the substrate, as demonstrated in a previous work [18].

Figure 4.

(Left), in black lines: CO2/CH4 selectivity vs. transmembrane pressure of M0: initial (squares), M1: post-cured (circles), and M2: final heat-treated (triangles) membrane states. (Left), in red lines: CO2 (black) permeance vs. transmembrane pressure of M0: initial (squares), M1: post-cured (circles), and M2: final heat-treated (triangles) membrane states. (Right): CO2/CH4 selectivity of final heat-treated membrane (M2 state) at low pressure. Measurements at 298 K and 313 K each at two low transmembrane pressures (2 and 4 bar(a)).

It is noteworthy that the inclusion of GNP filler in the spinning dope solution allowed us to extend the air gap beyond spinnability limits of pure P84 using the same solvent and P84 concentration as the addition of GNPs enhanced its viscosity. A higher air gap is known to lead to pore narrowing [52,53], which is of particular importance when the preparation of HF substrates with minimal pore intrusion during dip coating is desired. In addition, narrower pores also provide stronger mechanical support to the separation layer, allowing it to withstand the stresses imposed by high applied pressure.

The observed drop in CO2/CH4 selectivity at both 2 and 4 bar as the temperature increases from 298 K to 313 K in the M2 state indicates a significant and strong temperature dependence of the membrane’s performance, even after the thermal “healing” treatment. More specifically, in the M2 state, the membrane provided a CO2/CH4 selectivity of 71.7 at 298 K versus 43.7 at 313 K at 2 bar(a), while the CO2/CH4 selectivity was 68.5 at 298 K versus ~43.3 at 313 K at 4 bar(a). This decline can be attributed to the fact that gas transport in polymer membranes typically follows a solution-diffusion mechanism, where both solubility and diffusivity are temperature dependent. As temperature increases, gas diffusivity typically rises because of enhanced molecular motion, while solubility, particularly for more condensable gases such as CO2, tends to decrease. Since CO2 benefits more from solubility selectivity than CH4, the decrease in solubility at higher temperatures disproportionately reduces CO2 transport relative to CH4, resulting in lower overall selectivity. Additionally, elevated temperatures can affect the microstructure of the membrane, even after healing. The thermal treatment applied to restore M2 may improve selectivity at ambient temperature, but increasing the temperature beyond that can partially reverse these improvements by softening the polymer matrix, increasing chain mobility and reducing the size-sieving capability of the membrane. This effect allows more CH4 molecules, which are typically more size-restricted, to permeate more easily, further lowering CO2/CH4 selectivity. The nearly consistent drop in selectivity across pressures suggests that temperature, rather than pressure, is the dominant factor influencing separation efficiency in this case.

The drop in CO2/CH4 selectivity of M1 from 22 to 15 as pressure increased from 20 to 30 bar is likely due to membrane compaction and physical aging effects rather than significant plasticization effects. After one month of storage at ambient temperature and subsequent re-operation at high pressure (28 bar) for 12 h, M1 likely experienced structural relaxation and compaction, reducing its free volume and changing the mobility of its polymer chains. Although CO2 permeance remained relatively stable, CH4 permeance likely increased slightly at higher pressure due to reduced size-sieving ability of the compacted membrane matrix. This leads to reduced discrimination between CO2 and CH4, ultimately lowering selectivity under high-pressure conditions.

Respective CO2 permeances of the three membrane states, as depicted in Figure 4 (left), were found to have magnitudes in the order M0 > M1 > M2, which in contrast with selectivities shows that permeance was not restored by the “healing” process. At the same time, all three states showed a permeance decline with increasing transmembrane pressure [14]. At this point, it must be noted that comparing M0 and M1, membrane compaction favored CH4 by preferentially raising a higher barrier/resistance to CO2 permeance [18,54], whereas, comparing M1 and M2, compaction was found to further increase the barrier to both gases but favoring CO2, possibly due to polymer chain rearrangement after the “healing” process [55].

Conversely, comparing M1 and M2, compaction was found to increase the transport resistance for both CO2 and CH4 but with a more pronounced impact on CH4, resulting in enhanced CO2/CH4 selectivity in M2. This suggests that the thermal “healing” process applied to M2 may have induced polymer chain rearrangement and densification, effectively reducing the size and accessibility of the free volume spaces within the membrane matrix. Such structural refinement can favor smaller, more condensable gases like CO2 while increasingly restricting the diffusion of larger molecules like CH4. Although both M1 and M2 exhibit low permeance due to compaction, this effect alone does not directly cause selectivity changes. Instead, it reflects the denser structure and the reduction in free volume. However, low permeance can increase the susceptibility of experimental measurements to variability in flow rates and limitations in detection accuracy, potentially exaggerating observed selectivity trends. Thus, the improved selectivity in M2 is primarily attributed to structural changes from thermal treatment, with low permeance playing a secondary role in measurement sensitivity [56]. These findings highlight key design principles for developing membranes with improved long-term stability and tunable selectivity. The observed interplay between GNP filler distribution, polymer chain mobility, and pressure-induced compaction demonstrates that well-dispersed nanofillers can enhance mechanical reinforcement while stabilizing the microstructure against densification. At the same time, controlled thermal relaxation shows the potential to fine-tune free-volume architecture and restore selective transport pathways after compaction. These insights suggest that optimizing filler loading, dispersion quality, and post-treatment protocols can yield mixed-matrix membranes with higher resistance to structural deformation, more predictable long-term aging behavior, and tunable selectivity suitable for operation under demanding high-pressure gas separation applications.

3.2. Electric Impedance Spectroscopy

Regarding impedance spectroscopy results, the following Table 2 indicates/outlines the values of the electrical circuit components observed during membrane operation in the specific tests. A number of 10 sequential frequency scans were performed during each membrane operation under constant pressure conditions. The electrical parameter values emerging from these sequential measurements fluctuated between a minimum and a maximum value, as given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gas separation performance at ΔP = 20 bar(a) and T = 298 K and simultaneously measured electric parameters from impedance spectroscopy.

For a CO2-selective membrane, one would typically expect the CO2 concentration in the permeate to be higher than in the feed. However, when a sweep gas such as helium is used on the permeate side, it dilutes the permeating species, reducing their concentration in the permeate stream. As a result, even though CO2 permeates preferentially, its measured concentration in the permeate can appear lower than in the feed due to this dilution effect. If the goal is to evaluate CO2 removal efficiency without introducing CO2 into the CH4 stream, which is particularly important in applications such as natural gas upgrading, it is more appropriate to express the results in terms of CO2 removal from the feed or the CH4 purity in the retentate. Reporting the CO2 concentration in CH4 in the permeate may be misleading or irrelevant, especially when the permeate is not the desired product stream.

Additionally, it must be noticed that, after the heat treatment, the geometric (background) capacitance C2 has decreased from 3.53 pF for states M0 and M1 to 0.2 pF for the heat-treated state M2. This fact can be attributed to a drop in the dielectric constant of the polymer. This drop can be caused by heat-treatment-induced drying and densification of the polymer, which are factors known for causing a reduction in the polarizability of the polymer dielectric [57].

Measurements with fitted data from three indicative measurements, each corresponding to a distinct membrane state, are depicted in Figure 5, comparing the impedance and phase angle characteristics of these membrane states. The left column illustrates the impedance magnitude ∣Z∣ as a function of frequency, while the right column displays the corresponding phase angle responses. The equivalent circuit parameter values derived from these indicative measurements are shown in the insets. The green curves represent the models, which closely align with the experimental data, validating the reliability of the equivalent circuit model used for fitting.

Figure 5.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) Bode plots with fitting curves for M0, M1, and M2 membrane states (from top to bottom).

Although increased densification might be expected to improve contact between conductive fillers and reduce resistance, its actual effect depends on changes in the membrane’s internal morphology. Compaction can lead to microstructural rearrangement that disrupts conductive pathways, particularly, if the filler distribution is non-uniform or below the percolation threshold. Furthermore, densification may decrease free volume and restrict segmental mobility, hindering ionic transport or creating more tortuous paths, which results in increased electrical resistance. As a result, the observed increase in resistance is more likely attributed to disrupted pathways and reduced ionic mobility than to enhanced filler contact.

Overall, frequency scans indicated that the phase angle of the impedance vector exhibited a peak at a particular frequency, denoted as fP, while the magnitude of the impedance vector was decreasing steadily with increasing frequency. The ongoing permeance reduction, a consequence of membrane compaction, appears to be associated with a progressive increase in AC resistance R1 and a decrease in fp (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

MMM’s (a) selectivity and (b) CO2 permeate concentration without sweep gas at ΔP = 20 bar(a), T = 298 K, for 10% CO2 in CH4 gas mixture under flow. (c) AC resistance and (d) frequency at peak of phase difference from impedance measurements performed simultaneously with gas permeation tests.

The rise in membrane density, combined with pressure-induced reorganization of GNP fillers within the matrix that increases rather than decreases electrical resistance, as previously reported by Zhao et al. [41] and other research groups [58,59], could explain the observed AC resistance R1 increase shown in Figure 6c [60,61]. In composites with a low conductive filler concentration, below the percolation threshold, bending of the membrane during one-sided pressurization may disrupt filler–filler contacts, reducing electron-conductive pathways instead of enhancing them and, therefore, increasing electric resistance. However, given the rigid HF geometry of the examined membranes, significant bending is unlikely, making polymer densification effect the more dominant factor influencing conductivity and governing the resistance increase.

Plastic compaction of the membrane under the high feed pressure is believed to have caused an initial filler rearrangement in the polymer matrix, which disrupted filler nanoparticle percolation due to reduction in matrix elasticity. This could to an extent be restored after the “healing” process. The long-time mild heating under the He flow allowed the polymer chains and filler nanoparticles to reorganize and reorientate forming a new microstructure that partly restored filler percolation. The selectivity drop to values of approximately 20 can be explained as a result of high pressure-induced plastic compaction causing filler rearrangement in a way that cancels their selectivity enhancing effect (the value of 20 is that of the pristine Pebax-1657 polymer). However, the exact structural changes still have to be examined, but this is beyond the scope of this work.

Furthermore, since fp equals to the inverse time constant R1C1, the increase in resistance R1 is accompanied by an expected decrease in fp, as illustrated in Figure 6d. These results provide valuable insights into the dynamics of membrane performance and compaction process under different operating conditions.

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

A hollow-fiber-supported Pebax-1657/GNP mixed-matrix membrane was evaluated for CO2/CH4 separation at transmembrane pressures up to 30 bar(a), demonstrating high CO2/CH4 selectivity (up to 61.4) and stable performance in the fresh state. After storage and high-pressure operation, the membrane exhibited reduced permeance and selectivity due to permanent compaction. However, a mild thermal treatment at 40 °C under a He atmosphere for 5 days could restore selectivity. Simultaneous impedance spectroscopy revealed a clear correlation between performance loss and increasing electrical resistance, showing that compaction-driven rearrangement of conductive fillers disrupts percolation pathways and increases R1. This work provides the first demonstration of an in situ electrical resistance monitoring approach for gas separation membranes, enabling real-time detection of microstructural changes that cannot be captured by permeance measurements alone. The results highlight the potential of Pebax-based MMMs for high-pressure separations and underscore the importance of coupling transport performance with structural diagnostics.

Future research will focus on tailoring GNP loading and dispersion to enhance mechanical robustness and stability, refining thermal relaxation protocols for recovery of compacted membranes, and extending the in situ impedance technique to long-term durability studies. Applying this methodology to other polymer-filler systems and gas pairs may enable predictive monitoring tools and the rational design of membranes with improved long-term stability and tunable selectivity for demanding industrial separations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.F., D.S.K., A.A.S. and S.B.; methodology, E.P.F. and D.S.K.; software, G.M. and A.G.; validation, E.P.F., A.A.S. and S.B.; formal analysis, G.V.T., A.A.S. and S.B.; investigation, D.S.K. and G.V.T.; resources, E.P.F. and G.M.; data curation, D.S.K., G.V.T. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.K.; writing—review and editing, E.P.F. and G.V.T.; visualization, G.V.T.; supervision, E.P.F.; project administration, E.P.F.; funding acquisition, E.P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (1) the General Secretariat for Research and Innovation, grant number GG-CO2, Τ2DGE-0183, and (2) the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

Data Availability Statement

The numerical data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Evangelos P. Favvas would like to thank the TH Köln for the funding of his 6-month fellowship through the “German Federal Ministry of Education and Research” (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF)).

Conflicts of Interest

Author George Maistros was employed by the company ADVISE DETA Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CA | Contact angle |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| CLSM | Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| DO | Direct observation |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| GNP | Graphene nanoplatelet |

| HIM | Helium-ion microscopy |

| HF | Hollow fiber |

| MMM | Mixed-matrix membrane |

| NG | Natural gas |

| NMP | N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TCD | Thermal conductivity detector |

| GBL | γ-Butyrolactone |

References

- Ghasem, N. CO2 removal from natural gas. In Advances in Carbon Capture; Rahimpour, M.R., Farsi, M., Makarem, M.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2020; pp. 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadirkhan, F.; Goh, P.S.; Ismail, A.F.; Wan Mustapa, W.N.F.; Halim, M.H.M.; Soh, W.K.; Yeo, S.Y. Recent Advances of Polymeric Membranes in Tackling Plasticization and Aging for Practical Industrial CO2/CH4 Applications—A Review. Membranes 2022, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewole, J.K.; Sultan, A.S. Polymeric Membranes for Natural Gas Processing: Polymer Synthesis and Membrane Gas Transport Properties. In Functional Polymers; Mazumder, M.A.J., Sheardown, H., Al-Ahmed, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. Membranes for Natural Gas Sweetening. In Encyclopedia of Membranes; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1266–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Vinh-Thang, H.; Ramirez, A.A.; Rodrigue, D.; Kaliaguine, S. Membrane gas separation technologies for biogas upgrading. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 24399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Moreno, F.M.; le Saché, E.; Pastor-Pérez, L.; Reina, T.R. Membrane-based technologies for biogas upgrading: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1649–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, A.; Lei, L.; Avruscio, E.; Karousos, D.S.; Lindbråthen, A.; Kouvelos, E.P.; He, X.; Favvas, E.P.; Barbieri, G. Long-term performance of highly selective carbon hollow fiber membranes for biogas upgrading in the presence of H2S and water vapor. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 448, 137615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, N.; Kearns, D. State of the Art: CCS Technologies; Technical Report; Global CCS Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanopoulos, K.L.; Favvas, E.P.; Karanikolos, G.N.; Alameri, W.; Kelessidis, V.C.; Youngs, T.G.A.; Bowron, D.T. Monitoring the CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Process at the Nanoscale: An In-Situ Neutron Scattering Study. Energy Adv. 2022, 1, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Sequestration of Supercritical CO2 in Deep Sedimentary Geological Formations. In Negative Emissions Technologies and Reliable Sequestration: A Research Agenda; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 319–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousos, D.S.; Theodorakopoulos, G.V.; He, X.; Romanos, G.E.; Brunetti, A.; Favvas, E.P. A comprehensive review of pristine Pebax-1657 membranes for CO2 gas separations. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 170938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzig, A.; Johlitz, M.; Lion, A. Ageing Phenomena in Polymers: A Short Survey. In Adhesive Joints: Ageing and Durability of Epoxies and Polyurethanes, 1st ed.; Possart, W., Brede, M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Weinheim, Germany, 2019; pp. 169–204. [Google Scholar]

- Domininghaus, H. Kunststoffe: Eigenschaften und Anwendungen, 8th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–1494. [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, A. Membrane Compaction. In Encyclopedia of Membranes; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisna, P.D.; Hou, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, V. Improved operational stability of Pebax-based gas separation membranes with ZIF-8: A comparative study of flat sheet and composite hollow fibre membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 524, 266–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Du, M.; Ding, X.; Xiang, C. Polymer Additives with Gas Barrier and Anti-Aging Properties Made from Asphaltenes via Supercritical Ethanol. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazani, F.; Aroujalian, A. Enhanced CO2-selective behavior of Pebax-1657: A comparative study between the influence of graphene-based fillers. Polym. Test. 2020, 81, 106264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, G.V.; Karousos, D.S.; Mansouris, K.G.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Kouvelos, E.P.; Favvas, E.P. Graphene nanoplatelets based polyimide/Pebax dual-layer mixed matrix hollow fiber membranes for CO2/CH4 and He/N2 separations. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farashi, Z.; Azizi, S.; Arzhandi, M.R.-D.; Noroozi, Z.; Azizi, N. Improving CO2/CH4 separation efficiency of Pebax-1657 membrane by adding Al2O3 nanoparticles in its matrix. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2019, 72, 103019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, T.; Masetto, N.; Wessling, M. Materials dependence of mixed gas plasticization behavior in asymmetric membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 306, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, Z. Pebax–PEG–MWCNT hybrid membranes with enhanced CO2 capture properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 460, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Car, A.; Stropnik, C.; Yave, W.; Peinemann, K.-V. Pebax®/polyethylene glycol blend thin film composite membranes for CO2 separation: Performance with mixed gases. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 62, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijerkerk, S.R.; Knoef, M.H.; Nijmeijer, K.; Wessling, M. Poly(ethylene glycol) and poly(dimethyl siloxane): Combining their advantages into efficient CO2 gas separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 352, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqilah, N.; Fauzan, B.; Mukhtar, H.; Nasir, R. Composite amine mixed matrix membranes for high- pressure CO2–CH4 separation: Synthesis, characterization and performance evaluation. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2020, 7, 200795. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Swaidan, R.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Litwiller, E.; Jouiad, M.; Pinnau, I.; Han, Y. Synthesis and Gas Transport Properties of Hydroxyl-Functionalized Polyimides with Intrinsic Microporosity. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 3841–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeling, N.; Konietzny, R.; Sieffert, D.; Rölling, P.; Staudt, C. Functionalized copolyimide membranes for the separation of gaseous and liquid mixtures. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2010, 6, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mo, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, W.; Ngo, H.K. In-situ monitoring techniques for membrane fouling and local filtration characteristics in hollow fiber membrane processes: A critical review. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 528, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, G.; Virtanen, T.; Ferrando, M.; Güell, C.; Lipnizki, F.; Kallioinen, M. A review of in situ real-time monitoring techniques for membrane fouling in the biotechnology, biorefinery and food sectors. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 588, 117221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtin, D.S.; Sokolov, S.E.; Borisov, I.L.; Volkov, V.V.; Volkov, A.V.; Samoilov, V.O. Mitigation of Physical Aging of Polymeric Membrane Materials for Gas Separation: A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xue, P.; Yan, X.; Qi, N.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, N. In situ monitoring of nonlinear physical aging and anti-aging in polymer-based separation membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 727, 124054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuToit, M.; Ngaboyamahina, E.; Wiesner, M. Pairing electrochemical impedance spectroscopy with conducting membranes for the in situ characterization of membrane fouling. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 618, 118680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.G.; Childress, A.E.; McGaughey, A.L. Onset, rate, and depth of wetting front progression in membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 713, 123253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, K.T.; Blankert, B.; Horn, H.; Wagner, M.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Bucs, S.; Fortunato, L. Noninvasive monitoring of fouling in membrane processes by optical coherence tomography: A review. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 692, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, H.T.; Chew, J.W. Critical flux of colloidal foulant in microfiltration: Effect of organic solvent. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 616, 118531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwarno, S.R.; Chen, X.; Chong, T.H.; McDougald, D.; Cohen, Y.; Rice, S.A.; Fane, A.G. Biofouling in reverse osmosis processes: The roles of flux, crossflow velocity and concentration polarization in biofilm development. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 467, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.H.; Bucs, S.S.; Witkamp, G.-J.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S. Organic composition in feed solution of forward osmosis membrane systems has no impact on the boron and water flux but reduces scaling. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 611, 118306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joens, M.S.; Huynh, C.; Kasuboski, J.M.; Ferranti, D.; Sigal, Y.J.; Zeitvogel, F.; Obst, M.; Burkhardt, C.J.; Curran, K.P.; Chalasani, S.H.; et al. Helium Ion Microscopy (HIM) for the imaging of biological samples at sub-nanometer resolution. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gode, P.; Lindbergh, G.; Sundholm, G. In-situ measurements of gas permeability in fuel cell membranes using a cylindrical microelectrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2002, 518, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazik, D.; Ebert, S.; Leuthold, M.; Hagenau, J.; Geistlinger, H. Membrane Based Measurement Technology for in situ Monitoring of Gases in Soil. Sensors 2009, 9, 756–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craster, B.; Jones, T.G.J. Permeation of a Range of Species through Polymer Layers under Varying Conditions of Temperature and Pressure: In Situ Measurement Methods. Polymers 2019, 11, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Zhang, X.; Deng, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, R. Flexible PEBAX/graphene electromagnetic shielding composite films with a negative pressure effect of resistance for pressure sensors applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotti, A.; Zuppolini, S.; Borriello, A.; Zarrelli, M. Polymer nanocomposites based on Graphite Nanoplatelets and amphiphilic graphene platelets. Compos. B Eng. 2022, 246, 110223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, K.; Ghayesh, M.H. A review on the mechanics of graphene nanoplatelets reinforced structures. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 186, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, S.N.; Badarudin, A.; Zubir, M.N.M.; Ming, H.N.; Misran, M.; Sadeghinezhad, E.; Mehrali, M.; Syuhada, N.I. Investigation on the use of graphene oxide as novel surfactant to stabilize weakly charged graphene nanoplatelets. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldi, P.; Athanassiou, A.; Bayer, I.S. Graphene Nanoplatelets-Based Advanced Materials and Recent Progress in Sustainable Applications. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, Y.-C.; Chou, H.-Y.; Shen, M.-Y. Effects of adding graphene nanoplatelets and nanocarbon aerogels to epoxy resins and their carbon fiber composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 178, 107869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorakopoulos, G.V.; Karousos, D.S.; Benra, J.; Forero, S.; Hammerstein, R.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Katsaros, F.K.; Schubert, T.; Favvas, E.P. Well-established carbon nanomaterials: Modification, characterization and dispersion study at different solvents. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 3339–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, A.N.; Theodorakopoulos, G.V.; Karousos, D.S.; Bouroushian, M.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Favvas, E.P. Nanocarbon-Based Mixed Matrix Pebax-1657 Flat Sheet Membranes for CO2/CH4 Separation. Membranes 2023, 13, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karousos, D.S.; Lei, L.; Lindbråthen, A.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Kouvelos, E.P.; He, X.; Favvas, E.P. Cellulose-based carbon hollow fiber membranes for high-pressure mixed gas separation of CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 253, 117473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, J.R.; Garber, J.A. Analysis of Impedance and Admittance Data for Solids and Liquids. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1977, 124, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tena, A.; Shishatskiy, S.; Filiz, V. Poly(ether–amide) vs. poly(ether–imide) copolymers for post-combustion membrane separation processes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 22310–22318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayet, M. The effects of air gap length on the internal and external morphology of hollow fiber membranes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 3091–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.Z.; Yong, W.F.; Chung, T.-S. High-performance composite hollow fiber membrane for flue gas and air separations. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 541, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Pan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, C. Thin poly(ether-block-amide)/attapulgite composite membranes with improved CO2 permeance and selectivity for CO2/N2 and CO2/CH4. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2017, 160, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, P.; Drioli, E.; Golemme, G. Membrane gas separation: A review/state of the art. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009, 48, 4638–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wei, J.; Deng, M.; Yang, L.; Yao, L.; Jiang, W.; He, X.; Wang, K.; Tang, J.; Tang, B.; et al. A pragmatic thermal treatment strategy for improved gas separation in 2D zeolite-based mixed matrix membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 370, 133246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogbojuri, G.; Abtahi, S.; Hendeniya, N.; Chang, B. The Effects of Chain Conformation and Nanostructure on the Dielectric Properties of Polymers. Materials 2025, 18, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, K.; Lee, S.-C.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Moon, C.; Park, S.-H. Smart conducting polymer composites having zero temperature coefficient of resistance. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, W. Lightweight and conductive carbon black/chlorinated poly(propylene carbonate) foams with a remarkable negative temperature coefficient effect of resistance for temperature sensor applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 9354–9362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistal, A.; Garcia, E.; Pérez -Coll, D.; Prieto, C.; Belmonte, M.; Osendi, M.I.; Miranzo, P. Low percolation threshold in highly conducting graphene nanoplatelets/glass composite coatings. Carbon 2018, 139, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, N.; Banerjee, R.; Muirhead, D.; Lee, J.; Liu, H.; Shrestha, P.; Wong, A.K.C.; Jankovic, J.; Tam, M.; Susac, D.; et al. Membrane dehydration with increasing current density at high inlet gas relative humidity in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 422, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).