Using VR and BCI to Improve Communication Between a Cyber-Physical System and an Operator in the Industrial Internet of Things

Abstract

1. Introduction

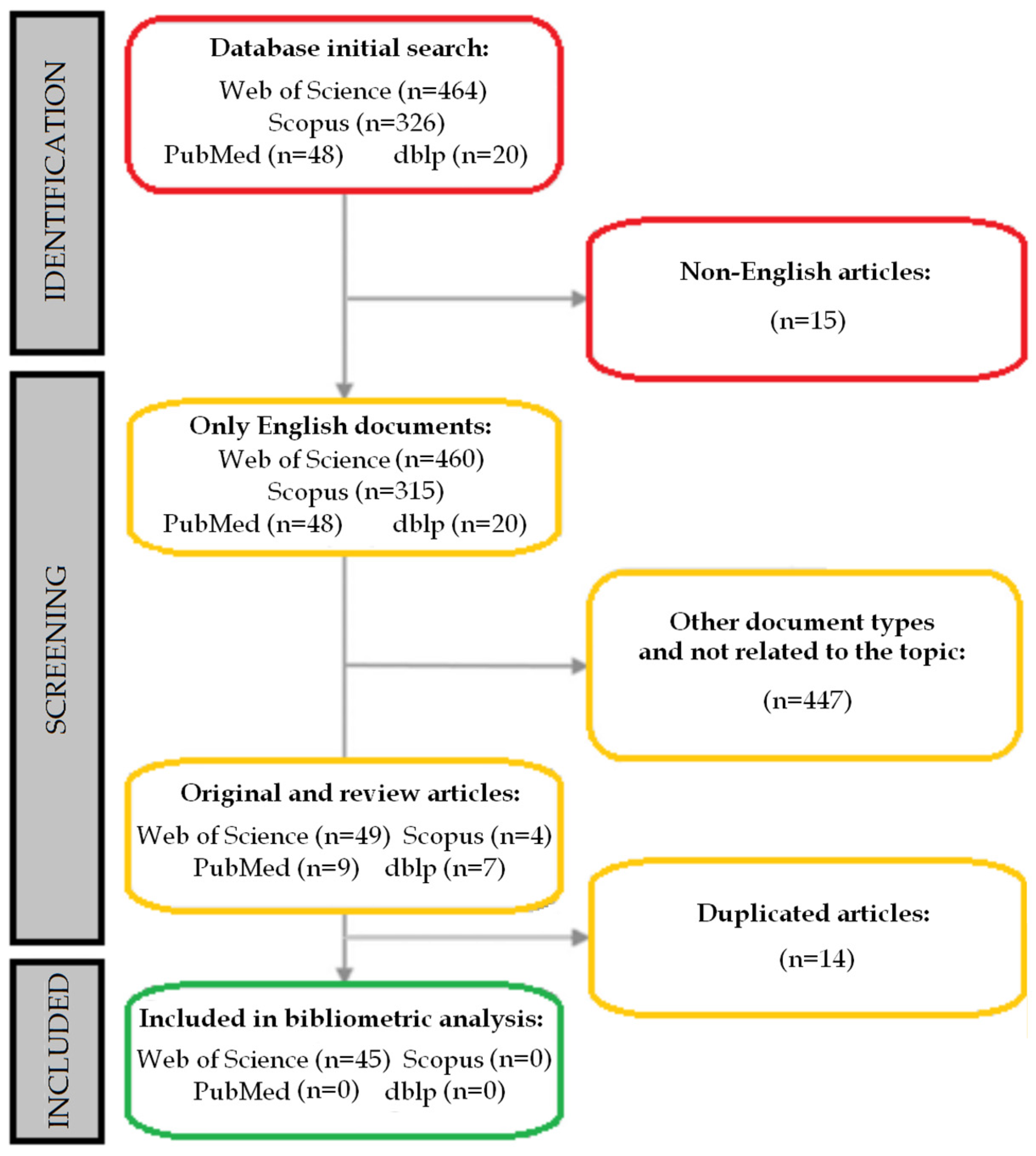

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Data Sources

- Data privacy and security, i.e., protecting sensitive information from unauthorized access;

- System latency, i.e., ensuring real-time performance, especially in critical telecommunications operations;

- User experience, i.e., mitigating VR motion sickness and ensuring that BCI devices are non-invasive and user-friendly;

- Network operations centers (NOCs): VR and BCIs improve monitoring, diagnostics, and optimization of multimedia traffic in telecommunications networks.

- Customer service: VR can provide interactive troubleshooting guides, while BCIs enable efficient responses in high-volume support environments.

3.2. Criteria of Signal(s) and Device(s) Selection Including Hybrid

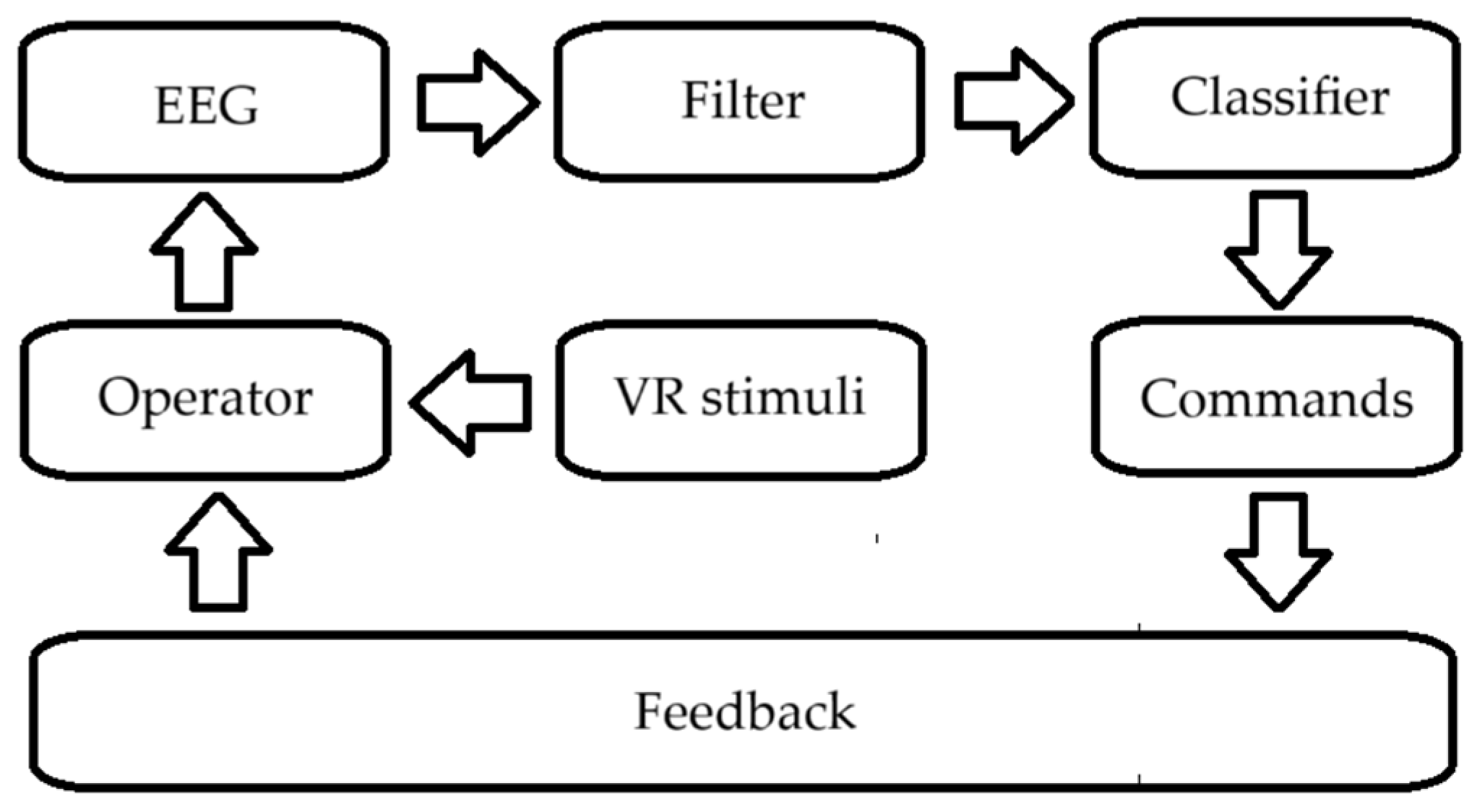

3.3. Planning of VR-BCI System

3.4. Operation of VR-BCI System

4. Discussion

- VR provides operators with an immersive and intuitive interface, improving the understanding of complex data and system operations;

- BCI enables hands-free control, allowing operators to perform tasks faster and more accurately in dynamic environments;

- BCIs can monitor cognitive states such as stress or fatigue, allowing systems to adapt and improve operator performance;

- BCI systems offer people with physical disabilities the ability to effectively interact with telecommunications systems.

- developing and implementing VR and BCI systems requires significant investments in hardware, software, and integration;

- VR may cause motion sickness or discomfort, while BCI devices may be invasive or difficult to wear for long periods of time;

- both technologies require low latency to be effective, which can be difficult in real-time telecommunications environments;

- use of BCIs involves sensitive data on brain activity, raising serious concerns about safety and ethical use.

- Phase 1—Assessment and feasibility: conduct a comprehensive needs analysis to identify communication gaps between operators and CPSs in industrial environments, with a focus on areas where VR and BCI can provide tangible added value;

- Phase 2—Infrastructure preparation: modernize the network and computing infrastructure to support the high-bandwidth, low-latency data transmission required for real-time VR visualization and BCI signal processing;

- Phase 3—Prototype development: develop small-scale pilot systems combining VR-based control interfaces with non-invasive BCI devices to test real-time operator-machine interactions;

- Phase 4—Data integration and AI enhancement: implementation of AI and machine learning algorithms to interpret neural data, personalize operator interfaces, and enhance system adaptability;

- Phase 5—Security and privacy framework: introduce robust cybersecurity measures and neural data protection policies that address privacy, consent, and data ownership;

- Phase 6—Human factors and training: development of ergonomic, cognitive, and safety guidelines for operators, including specialized training in VR-BCI system operation;

- Phase 7—Large-scale implementation and optimization: gradual scaling of implementations across industrial facilities, continuously monitoring performance, safety, and user acceptance;

- Phase 8—Standardization and policy development: collaboration with regulatory authorities, industry organizations, and ethics committees to develop standard protocols, interoperability frameworks, and ethical use policies.

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Technological and Economic Implications

4.3. Societal, Ethical and Legal Implications

4.4. Directions for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piszcz, A.; Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D. Impact of Virtual Reality on Brain–Computer Interface Performance in IoT Control—Review of Current State of Knowledge. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewski, D.; Piszcz, A.; Rojek, I.; Galas, K. Machine Learning Supporting Virtual Reality and Brain–Computer Interface to Assess Work–Life Balance Conditions for Employees. Electronics 2024, 13, 4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Huo, Z.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Z.; Niu, L.; Kang, X.; Huang, X. A VR-based BCI interactive system for UAV swarm control. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Bin, J.; Wang, J.; Zhan, G.; Zhang, L.; Gan, Z.; Kang, X. A dynamically optimized time-window length for SSVEP based hybrid BCI-VR system. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 84, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideraki, A.; Drigas, A. Combination of Virtual Reality (VR) and BCI & fMRI in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 2023, 19, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, L.; Bin, J.; Wang, J.; Zhan, G.; Jia, J.; Zhang, L.; Gan, Z.; Kang, X. Effect of 3D paradigm synchronous motion for SSVEP-based hybrid BCI-VR system. Medical Biol. Eng. Comput. 2023, 61, 2481–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, S.; Zhang, X.; Mao, L. Development and evaluation of BCI for operating VR flight simulator based on desktop VR equipment. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattan, G.H.; Andreev, A.; Mendoza, C.; Congedo, M. A Comparison of Mobile VR Display Running on an Ordinary Smartphone with Standard PC Display for P300-BCI Stimulus Presentation. IEEE Trans. Games 2021, 13, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudjarov, B.; Mitrev, R. Web-based VR Environment for Simulation and Visualization of Construction Manipulator Motion. In Proceedings of the 9th Balkan Conference on Informatics, BCI 2019, Sofia, Bulgaria, 26–28 September 2019; Volume 7, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aamer, A.; Esawy, A.; Swelam, O.; Nabil, T.; Anwar, A.; Eldeib, A. BCI Integrated with VR for Rehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 31st IEEE International Conference on Microelectronics (ICM 2019), Cairo, Egypt, 15–18 December 2019; pp. 166–169. [Google Scholar]

- Grichnik, R.; Benda, M.; Volosyak, I. A VR-Based Hybrid BCI Using SSVEP and Gesture Input. In International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 418–429. [Google Scholar]

- Stawicki, P.; Gembler, F.; Grichnik, R.; Volosyak, I. Remote Steering of a Mobile Robotic Car by Means of VR-Based SSVEP BCI. In International Work-Conference on Artificial Neural Networks; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 406–417. [Google Scholar]

- Lupu, R.G.; Irimia, D.C.; Ungureanu, F.; Poboroniuc, M.; Moldoveanu, A. BCI and FES Based Therapy for Stroke Rehabilitation Using VR Facilities. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, 2018, 4798359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Schukat, M. A low-Cost, Open-Source, BCI-VR Game Control Development Environment Prototype for Game Based Neurorehabilitation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Games, Entertainment, Media Conference (GEM), Galway, Ireland, 15–17 August 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Vourvopoulos, A.; Ferreira, A.; Bermúdez i Badia, S. Development and Assessment of a Self-paced BCI-VR Paradigm Using Multimodal Stimulation and Adaptive Performance. In International Conference on Physiological Computing Systems (Selected Papers); Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.; Lee, H.G.; Nam, Y.; Choi, S. Immersive BCI with SSVEP in VR head-mounted display. In Proceedings of the 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), Milan, Italy, 25–29 August 2015; pp. 1103–1106. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, M.; Yu, B.; Sui, L. Classification of EEG evoked in 2D and 3D virtual reality: Traditional machine learning versus deep learning. Biomed. Phys. Eng. Express 2024, 11, 015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, J.; Yang, G.H. Deep neural network-based adaptive supervisory control for strict-feedback nonlinear systems with sensor and actuator faults. Appl. Math. Comput. 2026, 511, 129745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husinsky, M.; Schlager, A.; Jalaeefar, A.; Klimpfinger, S.; Schumach, M. Situated Visualization of IIoT Data on the Hololens 2. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Christchurch, New Zealand, 12–16 March 2022; pp. 472–476. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, J.; Dias Pereira, J. Editorial: IoT, UAV, BCI empowered deep learning models in precision agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1399753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coogan, C.G.; He, B. Brain-computer interface control in a virtual reality environment and applications for the internet of things. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 10840–10849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaufmann, R.; Widulle, N.; Ehrhardt, J.; Vranjes, D.; Niggemann, O. On the Impact of Pretraining with Simulated Data on Anomaly Detection in CPS—A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 30th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Porto, Portugal, 9–12 September 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Antzoulatos, G.; Orfanidis, G.; Giannakeris, P.; Tzanetis, G.; Kampilis-Stathopoulos, G.; Kopalidis, N.; Gialampoukidis, I.; Vrochidis, S.; Kompatsiaris, I. Severity Level Assessment from Semantically Fused Video Content Analysis for Physical Threat Detection in Ground Segments of Space Systems. In European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; CyberICPS/SECPRE/ADIoT/SPOSE/CPS4CIP/CDT&SECOMANE ESORICS; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 461–476. [Google Scholar]

- Dangana, M.; Ansari, S.; Abbasi, Q.H.; Hussain, S.; Imran, M.A. Suitability of NB-IoT for Indoor Industrial Environment: A Survey and Insights. Sensors 2021, 21, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ishak, M.K.; Bhatti, M.K.L.; Khan, I.; Kim, K.I. A Comprehensive Review of Internet of Things: Technology Stack, Middlewares, and Fog/Edge Computing Interface. Sensors 2022, 22, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douibi, K.; Le Bars, S.; Lemontey, A.; Nag, L.; Balp, R.; Breda, G. Toward EEG-Based BCI Applications for Industry 4.0: Challenges and Possible Applications. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 705064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgher, U.; Ayaz, Y.; Taiar, R. Editorial: Advances in artificial intelligence (AI) in brain computer interface (BCI) and Industry 4.0 for human machine interaction (HMI). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1320536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onciul, R.; Tataru, C.I.; Dumitru, A.V.; Crivoi, C.; Serban, M.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Radoi, M.P.; Toader, C. Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience: Transformative Synergies in Brain Research and Clinical Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Azar, P.I.; Mejía-Muñoz, J.M.; Cruz-Mejía, O.; Torres-Escobar, R.; López, L.V.R. Fog Computing for Control of Cyber-Physical Systems in Industry Using BCI. Sensors 2023, 24, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drigas, A.; Sideraki, A. Brain Neuroplasticity Leveraging Virtual Reality and Brain—Computer Interface Technologies. Sensors 2024, 24, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, S.; Ding, P.; Wang, F.; Gong, A.; Fu, Y. The Effects of VR and TP Visual Cues on Motor Imagery Subjects and Performance. Electronics 2023, 12, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Chinea, K.; Gómez-González, J.F.; Acosta, L. Brain–Computer Interface Based on PLV-Spatial Filter and LSTM Classification for Intuitive Control of Avatars. Electronics 2024, 13, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.W.; Malakuti, S.; Grüner, S.; Finster, S.; Gebhardt, J.; Tan, R.; Schindler, T.; Gamer, T. Developing Industrial CPS: A Multi-Disciplinary Challenge. Sensors 2021, 21, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, G.; Abele, N.D.; Kluth, K. A Review and Qualitative Meta-Analysis of Digital Human Modeling and Cyber-Physical-Systems in Ergonomics 4.0. IISE Trans. Occup. Ergon. Hum. Factors 2021, 9, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Green, A.E.; Chen, Q.; Kenett, Y.N.; Sun, J.; Wei, D.; Qiu, J. Creative problem solving in knowledge-rich contexts. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagula, A.; Ajayi, O.; Maluleke, H. Cyber Physical Systems Dependability Using CPS-IOT Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayanan, K.; Shah, R.; Ramu, V.; Madathil, D.; Yao, Y.; Wang, I.; Brahmi, B.; Rahman, M.H. Motor Imagery Performance through Embodied Digital Twins in a Virtual Reality-Enabled Brain-Computer Interface Environment. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 207, e66859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, M.; Sánchez-Cuesta, F.; González-Zamorano, Y.; Pablo Romero, J.; Vourvopoulos, A. Investigating the synergistic neuromodulation effect of bilateral rTMS and VR brain-computer interfaces training in chronic stroke patients. J. Neural Eng. 2024, 21, 056037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y. Invasive BCI and Noninvasive BCI with VR/AR technology. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual Reality, and Visualization (AIVRV); SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2021; p. 12153. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, V.; Tripathi, U.; Chamola, V.; Rout, B.K.; Kanhere, S.S. A review on virtual reality and augmented reality use-cases of brain computer interface based applications for smart cities. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 88, 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, M.; Schukat, M. A low-cost, open-source, BCI-VR prototype for real-time signal processing of EEG to manipulate 3DVR objects as a form of neurofeedback. In Proceedings of the 29th Irish Signals and Systems Conference (ISSC), Belfast, UK, 21–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jamil, N.; Belkacem, A.N.; Ouhbi, S.; Lakas, A. Noninvasive electroencephalography equipment for assistive, adaptive, and rehabilitative brain–computer interfaces: A systematic literature review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parivash, F.; Amuzadeh, L.; Fallahi, A. Design Expanded BCI with Improved Efficiency for VR-embedded Neurorehabilitation Systems. In Proceedings of the 19th CSI International Symposium on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP), Shiraz, Iran, 25–27 October 2017; pp. 230–235. [Google Scholar]

- Pruss, E.; Prinsen, J.; Alimardani, M. ABCI-controlled Robot Assistant for Navigation and Object Manipulation in a VR Smart Home Environment. In Proceedings of the 15th International Joint Conference on Biomedical Engineering Systems and Technologies (BIOSTEC)/15th International Conference on Biomedical Electronics and Devices (BIODEVICES), Virtual, 9–11 February 2022; Volume 1, pp. 231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Cattan, G. The use of brain–computer interfaces in games is not ready for the general public. Front. Comput. Sci. 2021, 3, 628773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramu, V.; Lakshminarayanan, K. Virtual Embodiment: Revolutionizing Motor Imagery in VR-Enabled BCI with Digital Twins. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (IEEE CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 12–14 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.C.; Nuo, G. Research of VR-BCI and Its Application in Hand Soft Rehabilitation System. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Conference on Virtual Reality (ICVR), Foshan, China, 20–22 May 2021; pp. 254–261. [Google Scholar]

- Cattan, G.; Andreev, A.; Visinoni, E. Recommendations for Integrating a P300-Based Brain-Computer Interface in Virtual Reality Environments for Gaming: An Update. Computers 2020, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Dostatni, E.; Piszcz, A.; Galas, K. ML-Based Maintenance and Control Process Analysis, Simulation, and Automation—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, W.A.; Ahluwalia, A.; Darko, K.; Sanker, V.; Tan, J.K.; Tenkorang, P.O.; Ben-Jaafar, A.; Ranganathan, S.; Aderinto, N.; Mehta, A.; et al. Bridging minds and machines: The recent advances of brain-computer interfaces in neurological and neurosurgical applications. World Neurosurg. 2024, 189, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różanowski, K.; Sondej, T. Architecture Design of the High Integrated System-on-Chip for Biomedical Applications. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Mixed Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems (MIXDES 2013), Gdynia, Poland, 20–22 June 2013; pp. 529–533. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.P.S.; Silva, L.A.; Delisle-Rodriguez, D.; Cardoso, V.F.; Nakamura-Palacios, E.M.; Bastos-Filho, T.F. Unraveling Transformative Effects after tDCS and BCI Intervention in Chronic Post-Stroke Patient Rehabilitation—An Alternative Treatment Design Study. Sensors 2023, 23, 9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonowicz, P.; Podpora, M.; Rut, J. Digital Stereotypes in HMI—The Influence of Feature Quantity Distribution in Deep Learning Models Training. Sensors 2022, 22, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapała, D.; Augustynowicz, P.; Tokovarov, M. Recognition of Attentional States in VR Environment: An fNIRS Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, O.; Sheehan, A.M.; Raman, P.R.; Khara, K.S.; Khalifa, A.; Chatterjee, B. Machine-Learning Methods for Speech and Handwriting Detection Using Neural Signals: A Review. Sensors 2023, 23, 5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, E.J.; Raggam, P.; Kirsch, S.; Belardinelli, P.; Ziemann, U.; Zrenner, C. Artifacts in EEG-Based BCI Therapies: Friend or Foe? Sensors 2022, 22, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawala-Janik, A.; Podpora, M.; Baranowski, J.; Bauer, W.; Pelc, M. Innovative Approach in Analysis of EEG and EMG Signals—Comparision of the Two Novel Methods. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Methods and Models in Automation and Robotics (MMAR), Miedzyzdroje, Poland, 2–5 September 2014; pp. 804–807. [Google Scholar]

- Camargo-Vargas, D.; Callejas-Cuervo, M.; Mazzoleni, S. Brain-Computer Interfaces Systems for Upper and Lower Limb Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Mikołajewski, D.; Dostatni, E.; Kopowski, J. Specificity of 3D Printing and AI-Based Optimization of Medical Devices Using the Example of a Group of Exoskeletons. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliano, J.M.; Spicer, R.P.; Vourvopoulos, A.; Lefebvre, S.; Jann, K.; Ard, T.; Santarnecchi, E.; Krum, D.M.; Liew, S.-L. Embodiment Is Related to Better Performance on a Brain–Computer Interface in Immersive Virtual Reality: A Pilot Study. Sensors 2020, 20, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojek, I.; Dostatni, E.; Mikołajewski, D.; Pawłowski, L.; Wegrzyn-Wolska, K. Modern approach to sustainable production in the context of Industry 4.0. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Tech. Sci. 2022, 70, e143828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Asl, R.; Keshavarzi, M.; Chan, D.Y. Brain-Computer Interface in Virtual Reality. In Proceedings of the2019 9th International IEEE/EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering (NER), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–23 March 2019; pp. 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fan, K.; Gu, Q.; Ruan, Y. Channel-Dependent Multilayer EEG Time-Frequency Representations Combined with Transfer Learning-Based Deep CNN Framework for Few-Channel MI EEG Classification. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillen, A.; Omidi, M.; Ghaffari, F.; Romain, O.; Vanderborght, B.; Roelands, B.; Nowé, A.; De Pauw, K. User Evaluation of a Shared Robot Control System Combining BCI and Eye Tracking in a Portable Augmented Reality User Interface. Sensors 2024, 24, 5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunier, L.; Hoffmann, N.; Preda, M.; Fetita, C. Virtual Reality Interface Evaluation for Earthwork Teleoperation. Electronics 2023, 12, 4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Teng, J.; Lee, S.-M. Optimizing HMI for Intelligent Electric Vehicles Using BCI and Deep Neural Networks with Genetic Algorithms. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.; Ahn, M. P300 Brain–Computer Interface-Based Drone Control in Virtual and Augmented Reality. Sensors 2021, 21, 5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Hasan, W.Z.W.; Jiao, W.; Dong, X.; Ramli, H.R.; Norsahperi, N.M.H.; Wen, D. ChatGPT and BCI-VR: A new integrated diagnostic and therapeutic perspective for the accurate diagnosis and personalized treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1426055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjiaros, M.; Shimi, A.; Avraamides, A.N.; Neokleous, K.; Pattichis, C.S. Virtual Reality Brain–Computer Interfacing and the Role of Cognitive Skills. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 129240–129261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | Articles (original, reviews, communication, editorials), and chapters, including conference proceedings, in English |

| Exclusion criteria | Books older than 5 years, letters, conference abstracts without full text, other languages than English |

| Keywords used | Virtual reality, VR, brain–computer interface, BCI, interaction, optimisation/optimization |

| Used field codes (WoS) | “Subject” field (consisting of title, abstract, keyword plus and other keywords) |

| Used field codes (Sopus) | article title, abstract and keywords |

| Used field codes (PubMed) | manually |

| Used field codes (dblp) | manually |

| Boolean operators used | Yes (AND) |

| Applied filters | Results refined by publication year, document type (e.g., articles, reviews), and subject area (e.g., engineering) |

| Iteration and validation options | Query run iteratively, refinement based on the results, and validation by ensuring relevant articles appear among the top hits here available |

| Leverage truncation and wildcards used | Used symbols like * for word variations (e.g., “virtual realit*”) and ? for alternative spellings (e.g., “optimi?ation”) |

| Parameter/Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Leading types of publication | Article (55%), conference paper (45%) |

| Leading areas of science | Computer science (33%), Neuroscience (33%), Health (16%), Social sciences (16%) |

| Leading topics | Computer science interdisciplinary applications (33%), neurosciences (33%), computer science cybernetics (22%), computer science information systems (22%), computer science artificial intelligence (11%), computer science software engineering (11%), computer science theory methods (11%) |

| Leading countries | South Korea, Italy, China, Austria, Croatia, Germany, India |

| Leading scientists | L. Kim, J. Shin |

| Leading affiliations | Korea University, Korea Institute of Science and Technology KIST |

| Leading funders (where information available) | Institute for Information Communication Technology Planning Evaluation IITP Republic of Korea, Ministry of Science ICT MSIT Republic of Korea |

| Sustainable development goals | Good Health and Well Being, Life on Land |

| Technology | Main Capabilities | Limitations | Typical Use Cases | Relevance Compared to VR–BCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VR | Immersive 3D visualization; simulated environments; enhanced situational awareness | Requires hardware setup; limited tactile realism | Training, remote monitoring, simulation | Forms one half of the VR–BCI synergy, but lacks implicit cognitive data |

| AR | Overlays digital information on real environment; supports real-time guidance | Limited field of view; potential cognitive overload | Maintenance, assisted assembly | Less immersive than VR; does not capture operator cognitive states |

| Haptic Systems | Force and tactile feedback; improved motor guidance | Complex hardware; limited scalability | Teleoperation, precision tasks | Complements VR–BCI but cannot infer mental state |

| Eye- Tracking Interfaces | Measures gaze, attention; supports natural targeting | Sensitive to lighting and calibration | Control panels, safety monitoring | Useful but provides only partial cognitive insight |

| BCI (stand-alone) | Measures workload, attention, intention; enables hands-free control | No environmental immersion; susceptibility to noise | Cognitive monitoring, command triggering | Provides the cognitive dimension that VR lacks |

| Adaptive Automation | Dynamic task allocation based on predefined rules | Limited insight into operator state; not immersive | Process control, system optimization | VR–BCI can make adaptive automation context- and cognition-aware |

| VR–BCI Integration | Immersion + real-time cognitive adaptation; improved bidirectional communication | Signal processing challenges; integration complexity | Training, monitoring, decision support | Most comprehensive and human-aware approach |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piszcz, A.; Rojek, I.; Náprstková, N.; Mikołajewski, D. Using VR and BCI to Improve Communication Between a Cyber-Physical System and an Operator in the Industrial Internet of Things. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12805. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312805

Piszcz A, Rojek I, Náprstková N, Mikołajewski D. Using VR and BCI to Improve Communication Between a Cyber-Physical System and an Operator in the Industrial Internet of Things. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12805. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312805

Chicago/Turabian StylePiszcz, Adrianna, Izabela Rojek, Nataša Náprstková, and Dariusz Mikołajewski. 2025. "Using VR and BCI to Improve Communication Between a Cyber-Physical System and an Operator in the Industrial Internet of Things" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12805. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312805

APA StylePiszcz, A., Rojek, I., Náprstková, N., & Mikołajewski, D. (2025). Using VR and BCI to Improve Communication Between a Cyber-Physical System and an Operator in the Industrial Internet of Things. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12805. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312805