Featured Application

This work is applied in energy trading management systems and to determine Pareto front optimal solution in a multi-objective function.

Abstract

Energy management in smart microgrids is critical to achieving sustainable and efficient energy utilization. This study introduces a hybrid optimization framework combining neural networks (NNs) and multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs) (hybrid NN-MOGA) to address the dual objectives of minimizing total energy cost and maximizing customer satisfaction. The hybrid NN-MOGA approach leverages NNs for predictive modeling of load and renewable energy generation, feeding accurate inputs to the MOGA for enhanced Pareto-optimal solutions. The performance of the proposed method is benchmarked against traditional optimization techniques, including MOGA, multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO), and the multi-objective firefly algorithm (MOFA). The simulation results demonstrate that hybrid NN-MOGA outperforms the alternative model. The proposed method produces uniformly distributed and highly convergent Pareto frontiers, ensuring robust trade-offs of USD 48.2817 and 81.7898 for total cost and customer satisfaction, respectively. Convexity analysis and the satisfaction of Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions further validate the optimization model.

1. Introduction

The increasing global energy demand has accelerated the transition toward sustainable and efficient energy systems, with renewable energy sources (RES) and decentralized microgrids (MGs) playing pivotal roles. Smart microgrids (SMGs) enable bidirectional information and energy flow, facilitating the seamless integration of RES such as solar, hydro, wind, and biomass [1,2]. However, the intermittent nature of these energy sources and the complexities of demand-side management (DSM) present significant challenges in achieving operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and customer satisfaction in energy trading systems [3,4].

Energy aggregators have emerged as critical intermediaries in this landscape. Aggregators optimize resource allocation, facilitate communication [5] between utilities and prosumers and ensure grid stability. Despite advancements in optimization techniques, such as multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs), multi-objective particle swarm optimization (MOPSO) [6], the adaptive multi/many-objective transformation technique [7], and multi-objective firefly algorithms (MOFAs) [8], existing methods often fail to achieve uniformly distributed and robust Pareto-optimal solutions, particularly in complex and non-linear energy management problems. To address these gaps, this research introduces a hybrid optimization framework that integrates neural networks (NNs) with multi-objective genetic algorithms (MOGAs). The proposed hybrid NN-MOGA approach leverages NNs for predictive modeling of load and renewable energy generation, enabling more accurate and dynamic inputs to the optimization process. Unlike traditional methods, the hybrid approach demonstrates superior performance that balances conflicting objectives, such as minimizing total energy cost and maximizing customer satisfaction.

MGs are integrated energy networks that comprise decentralized energy resources (DER), smart controllers [9], and electric load systems. MGs can operate independently, in clusters with other sub-MGs, or in conjunction with conventional grids to ensure energy balance in peer-to-grid (P2G) energy trading systems [10,11]. DSM, defined as the set of actions undertaken by utilities to optimize resource allocation and enhance end-user efficiency, plays a critical role in SMGs [12,13]. DSM strategies can be broadly categorized into incentive-based and time-based approaches. Incentive-based DSM includes mechanisms such as direct load control and flexible service [14], while time-based DSM employs strategies like critical-peak pricing and peak load reduction credits [15]. Despite their effectiveness, challenges to implementing DSM in residential areas persist due to communication delays [5,16] and the impracticality of direct customer engagement in large-scale operations [17]. Aggregators serve as important entities to bridge this gap, facilitating communication and resource coordination [4,18].

Demand response (DR), often used interchangeably with DSM, leverages demand-side flexibility to support active distribution system management [19]. By adjusting or reducing flexible loads, DR helps integrate RES, reduce utility procurement costs, and minimize the peak-to-average ratio (PAR) of aggregated load profiles [20,21]. Recent developments in distribution-level markets, such as the New York Reforming the Energy Vision (NY REV), highlight the potential for direct transactions between utilities and small-scale distributed energy resources (DERs), which promote autonomy and reduce barriers for smaller entities [20]. Similar initiatives in Europe and Asia emphasize the role of aggregators and regulatory reforms to enable small-scale participation in energy markets [22,23].

In Africa, the recurrent issue of energy poverty continues to pose a significant and critical challenge, especially in the sub-Saharan regions, where availability and accessibility to sustainable and RES remain severely limited and constrained. By strategically leveraging the abundant and untapped solar energy resources that are prevalent in this region, along with the implementation of flexible and adaptive regulatory frameworks, it is possible to facilitate the development of community-based energy trading systems and to promote the emergence of “flexumers,”. These are people who actively participate and contribute to the dynamic energy landscape [24]. In Korea, the recent “Act on the Promotion of Distributed Energy,” effective since June 2024, allows small-scale renewable energy facilities to engage in direct electricity trading [25]. Similarly, Japan has progressively liberalized its power market since 1995, culminating in the comprehensive deregulation of retail electricity by 2016 [26].

This paper proposes a novel hybrid optimization framework that integrates NNs with MOGAs. The hybrid NN-MOGA method improves energy management by leveraging predictive modeling for improved Pareto-optimal solutions. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- Development of a hybrid NN-MOGA framework for peer-to-grid optimization.

- Formulation of objective functions that minimize total cost and maximize customer satisfaction.

- Validation through convexity analysis and Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions.

- Comparison of the Pareto front of the hybrid NN-MOGA against MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA, demonstrating improved cost efficiency, customer satisfaction, hyper-volume (HV) convergence, diversity spread (DS), error analysis, and statistical analysis.

Integration of DSM strategies with aggregators for enhanced decision-making.

By addressing the limitations of existing optimization techniques and emphasizing the role of aggregators, this study proposes a scalable and effective solution to improve energy management in SMGs. The results contribute to advances in sustainable energy systems and underscore the potential of hybrid optimization in solving real-world energy challenges. MATLAB, with its multi-paradigm numerical computing environment, is utilized in this study for energy management analysis. Its fourth-generation programming capabilities, including built-in optimization toolboxes and data visualization features, make it a suitable choice to implement the proposed hybrid NN-MOGA framework [21].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related literature and presents the system model and formulates the proposed multi-objective optimization problem, and Section 3 discusses the simulation results. Section 4 concludes the paper. The proof of convexity, the Lagrangian formulation, the knee-point identification procedure, and the accuracy metric expressions are provided in Appendix A.

2. Related Work

Energy trading has emerged as a key operational paradigm in decentralized and transactive energy systems, enabling prosumers and microgrids (MGs) to exchange energy while improving economic efficiency and system reliability. In such environments, effective coordination mechanisms are essential to balance distributed generation, local demand, and renewable energy variability. As a result, various optimization, forecasting, and demand-side management (DSM) techniques have been proposed to support decision-making within modern MG networks.

Energy trading frameworks generally adopt either centralized or decentralized control structures. In centralized approaches, an aggregator or control center schedules consumer loads and generation dispatch, typically without explicitly considering consumer comfort or preferences [27]. In contrast, decentralized control frameworks provide greater autonomy to consumers, allowing them to adjust their demand profiles to meet dynamic system conditions while maintaining overall grid balance. Centralized hubs often coordinate power sharing across interconnected MGs, enabling efficient utilization of surplus generation and enhancing overall energy trading efficiency.

A series of studies have examined the integration of optimization algorithms into MG energy management systems. The authors in [28] emphasize the need for robust optimization techniques capable of ensuring reliability and operational efficiency in the presence of highly intermittent renewable energy sources (RES). Complementary to this, the work in [29] highlights DSM as a critical tool for mitigating the variability of renewable generation. This study surveys DSM methodologies, mathematical formulations, and key enabling technologies, including energy storage systems and electric vehicles.

Hybrid MG architectures based on RES have also been explored to address supply reliability and cost minimization challenges. In [30], a multi-objective optimization methodology grounded in Six Sigma principles is presented for sizing hybrid MG systems. Similarly, the authors in [31] investigate the economic operation of MGs with high distributed generation penetration, proposing a scheduling framework based on an improved particle swarm optimization–exterior point method (IPSO-EPM) to enhance the efficiency of isolated MGs.

Hierarchical DSM models have been proposed to enable scalable control across different grid layers. For instance, the study in [4] introduces a hierarchical structure encompassing utility operators, DR aggregators, and end users. An artificial immune algorithm is employed to minimize operational costs while ensuring incentives for DR aggregators. A related effort in [32] proposes a hybrid renewable energy system optimization framework that minimizes cost and power loss while maximizing RES utilization. The methodology integrates the Taguchi method with fuzzy multi-objective optimization and compares its performance with established algorithms such as NSGA-II and MOPSO.

Additional research has focused on design constraints and system feasibility for distributed generation resources. The work in [33] considers equipment availability and cost during the design of hybrid RES systems and employs a MOPSO-based optimization strategy. Likewise, ref. [34] applies NSGA-II to identify optimal trade-offs among renewable penetration, reliability, and system cost for MG deployments in remote areas. Recent studies have introduced multi-stage or hybrid optimization schemes to further enhance MG performance. The authors in [35] propose a two-stage dispatch model combining day-ahead and real-time scheduling using a hybrid PSO–OGSA algorithm to minimize conversion losses and improve renewable energy utilization. In [36], deterministic and stochastic optimization methods are applied to assess hybrid MG configurations in rural Malaysian communities, enabling the evaluation of dynamic energy pricing under uncertain conditions. Machine learning has also been incorporated into MG optimization: ref. [37] presents a predictive energy management strategy for residential PV battery hybrid systems using ML-based forecasting to optimize cost, battery health, and grid interaction.

Advanced hybrid intelligence techniques have further expanded the scope of DR and energy trading optimization. In [38], a hybrid DR strategy integrating global jackal optimization and deep convolutional NN is introduced to enhance the performance of solar, wind, and battery storage systems. Similarly, ref. [16] combines deep learning with quantum computing using a modified deep quantum neural network (MDQNN) to improve DR prediction accuracy and enhance sustainability objectives. More recently, ref. [39] proposed a hybrid cooperative and non-cooperative multi-objective optimization framework for MG energy trading, achieving significant improvements in cost savings and scheduling flexibility.

Despite these advancements, the existing literature reveals an important research gap. Prior studies have generally focused on proposing a single optimization method or hybrid technique but have seldom compared multiple multi-objective optimization algorithms to evaluate their respective trade-offs, convergence characteristics, diversity spread, and suitability for DSM applications. Moreover, limited attention has been given to analyzing Pareto-front properties, such as hyper-volume (HV), diversity spread (DS), convexity, and knee-point behavior metrics, which are essential for assessing the quality of multi-objective solutions in complex nonlinear MG environments.

To address these challenges, this work introduces a hybrid NN-MOGA that combines data-driven forecasting with evolutionary optimization to enhance decision accuracy and convergence performance. Furthermore, the proposed framework is evaluated against alternative optimization techniques, providing a comparative assessment of algorithmic behavior across HV, DS, convexity, and Pareto knee-point metrics. By integrating hybrid learning mechanisms and conducting a detailed multi-algorithm performance comparison, this work contributes a comprehensive and analytically robust optimization framework for next-generation DSM and energy trading applications.

A neural network is employed in this study due to the inherently dynamic and time-varying nature of RES data, making it a suitable and effective tool for time-series prediction. In addition, the multi-objective genetic algorithm is adopted for optimization, as it offers strong global exploration capability, performs reliably in non-convex search spaces, and can effectively handle complex constraints. A hybrid NN–MOGA combines forecasting and optimization in a single intelligent framework.

2.1. Roles of Aggregator in Energy Market

In energy trading, an aggregator assumes a pivotal position in facilitating the connection between minor, dispersed energy sources and extensive energy markets or services. The role of aggregators will increase as the RES continues to penetrate all sectors [40,41,42]. The subsequent are the primary functions and responsibilities of an aggregator in energy trading. The DR aggregator groups customers to have more market influence. It mediates between customers and the utility, ensuring DSM service and reduced bills. It boosts supply security and efficiency by adjusting consumption patterns. Ideally, demand should match generation. Customers may receive compensation for participating in DSM [4,43]. The principal responsibilities of an aggregator in distributed energy system operation are as follows:

- Access to markets and representation;

- Optimization and control action;

- Equilibrium of services;

- Financial settlement;

- Regulatory control and supervision.

2.2. Flow Chart of System Model

The system model employs the use of a hybrid optimization process that combines the functionality of NNs and MOGAs to optimize the multi-objective function. The NN is utilized in predicting load and solar generation, and the data is trained, tested, and validated. The output of the NN is fed as input to the MOGA optimizer, which processes it through a multi-objective formulation. Then, to test for convexity, the multi-objective function is run, the Pareto frontier is generated, and the optimal solution is fed into the NN as feedback to adjust the solution in real time. In addition, the energy user employs DSM based on incentives and price to adjust their consumption behavior. The DR has two methods or responses, either centralized or decentralized. In centralized control, an aggregator or utility center manages the consumer’s load pattern with no regard to consumer satisfaction levels. Conversely, in a decentralized control system, consumers have the flexibility to adjust their consumption patterns to meet the demand specified by the utility. This work employs the use of a hybrid optimization method to allocate energy usage in the decentralized energy management system, where energy users adjust their load demand based on cost and customer satisfaction. The aggregator determines the optimal solution of energy trade based on the available capacity and adjusts the scheduling to achieve the lowest cost and maximum satisfaction.

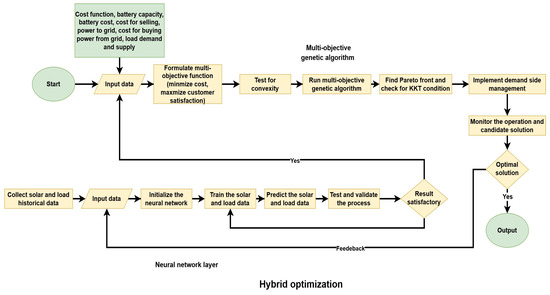

2.3. Flow Chart Implementation of Hybrid Optimization

The implementation of DR from the aggregator shown in Figure 1 starts with initializing the system. Then, solar and load data are collected from DERS and sensors. The system initializes, trains, predicts, tests, and validates the data. A satisfactory result is fed to the MOGA optimizer. The optimizer formulates the objective function based on the goals of the aggregator. The next step is to test the convexity of the function. The MOGA is used to run the optimizer. Then, the Pareto frontier is obtained and the KKT condition is determined. The aggregator implements DSM using incentive-based DSM or price-based DSM. The aggregator monitors the operation and candidate solution for optimal performance. A feedback system is activated if the system does not meet the optimal solution, and the process is repeated.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of hybrid optimization.

2.4. Neural Network Model

A comprehensive machine learning instrument possesses the ability to identify complex interrelations within historical datasets and conducts feature engineering to produce accurate predictions regarding solar, wind, and load dynamics [44,45]. Neural networks are composed of input nodes, hidden layers, output node, and activation function [46]. The general formula for NN is cited in (1):

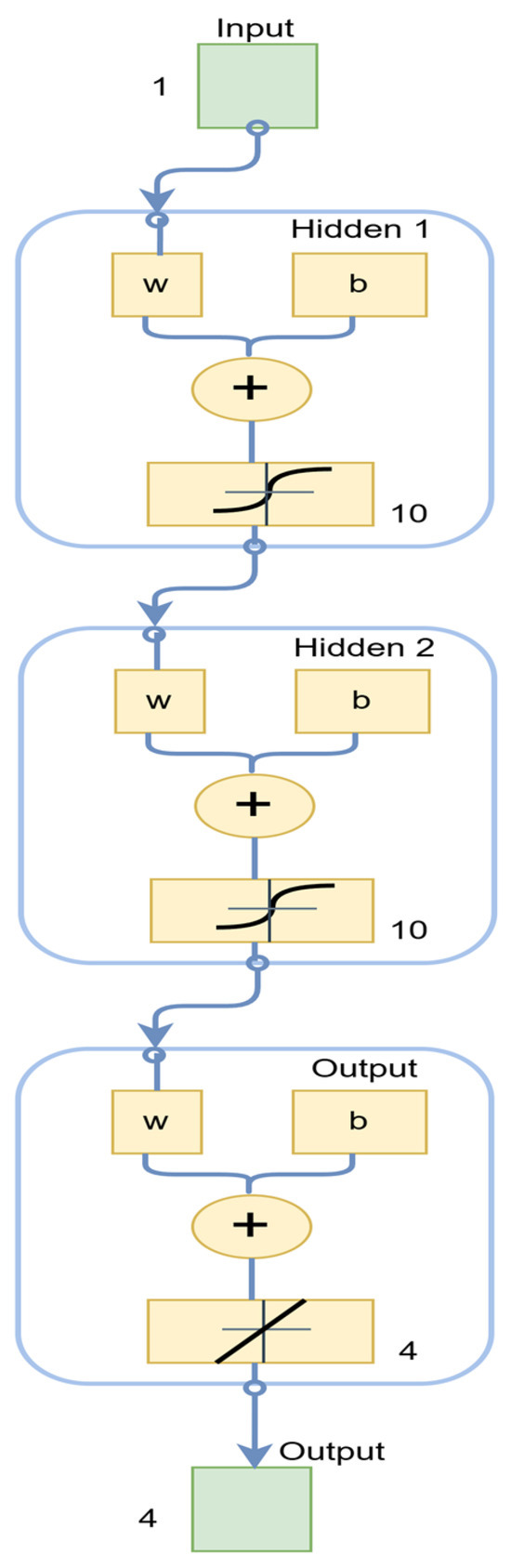

where is the predicted electric load or solar generation; is the input features, such as power, voltage, weather conditions, or seasons of the year; and are the weights of the neural network layers; and are the biases of the respective layers; is the activation function used in the hidden layers, which is a sigmoid function; and is the activation function used in the output layers, which is a tangent function. Figure 2 shows the neural network neurons used for training in the system. The diagram was taken from the MATLAB R2024a simulation results of the neural network (NN) tool.

Figure 2.

Neural network model.

Figure 2 shows an input layer with 1 neuron, two hidden layers with 10 neurons each, and an output layer with of 4 neurons. The hidden layers use a sigmoid function, while the output layer uses a tangent function as an activation function.

2.5. Mathematical Model of Energy System

In RES, various components are integrated to form the entire variable set of the energy system, encompassing a diverse range of elements that contribute to its overall functionality and performance. These components work in synergy to ensure the smooth operation and efficiency of the RES, with each playing a crucial role in the generation, distribution, and utilization of renewable energy sources. The equations that govern the behavior and characteristics of the energy system devices within the RES are listed and defined to provide a comprehensive understanding of their functions and interactions.

- Mathematical model of photovoltaic power generation: Photovoltaic energy production is influenced by various environmental parameters, including solar irradiance and surrounding temperature levels. The mathematical representation of the power output of photovoltaic modules is given as follows:where is the real power output of the solar cell, is the maximum power for standard test conditions, is the reference solar irradiance of 1000 , is the ambient temperature, is the solar irradiance, is the power temperature coefficient, and is the working temperature of the solar cell.

- Mathematical model of energy storage system: The energy storage system (ESS) is employed to retain surplus generation from various RES sources. The charging and discharging cycles of the battery are regulated by the energy management system to facilitate the optimization of the user’s objectives. The energy contained within the battery energy storage is expressed in Equation (3) [47,48,49]:where is the energy stored in the ESS at time (kWh). , and are the initial states of charge, charging power, and discharging power, respectively. and are the charging and discharging efficiencies. Both and are taken as 0.98. is the charging flag indicator, is a specific time instant within period , and is the total time under consideration.

- Mathematical model of cost of photovoltaics: The operation cost of solar PV is represented as [39]where is the unit maintenance cost of solar power generation, is the cost coefficient of solar power generation, and is the solar generation power.

- Mathematical model of cost function for energy storage systems: To calculate the cost of the energy storage system (ESS), we use Equation (5) [39,48]:where is the cost of the ESS at time (USD/kWh), is the coefficient cost of the ESS, is the energy stored in the ESS at time , is the input power to the ESS at time (kilowatt), is the rated capacity of ESS, and is the leakage loss coefficient of the battery ESS.

The proposed model adopts a deterministic formulation to allow for clear evaluation of the multi-objective optimization framework and to reduce computational complexity. Meanwhile, the forecasting module captures variability through historical data.

2.6. Multi-Objective Optimization

Problem formulation is implemented by defining the two main objectives and choosing the best optimal values from the optimization process. The system has two objective functions, which are to minimize total cost and maximize customer satisfaction.

Objective function 1: This objective function minimizes total energy cost in an MG. Consider an MG with prosumers over time periods. The total energy cost over time is given as follows:

where is the amount of power purchased by prosumers in kilowatt-hours (kWh), costs per kilowatt-hour for power purchased from the grid in USD per kWh (USD/kWh), is the amount of power sold by each prosumer back to the grid in kilowatt-hours (kWh), is revenue earned per kilowatt-hour for power sold to the grid in USD per kWh (USD/kWh), is the cost coefficient for the energy storage system, representing the cost per kWh of energy usage in USD per kWh (USD/kWh), and is the power stored or discharged from the battery for each prosumer in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

Power balance constraint: The total power consumed should be equal to the sum of power generated and stored, expressed as

where is the solar generation, and is the load demand at time for prosumer .

Battery capacity constraint: The battery storage must be within its capacity limits, expressed as

where is the maximum battery storage, and the unit is kilowatts (kW).

Non-negativity constraint: Power and storage values should be non-negative, expressed as

Objective function 2: This objective function maximizes customer satisfaction:

where , , and are parameters that can be adjusted to reflect the preferences of participant which corresponds to the power bought . represents customer satisfaction. This function exhibits diminishing marginal utility, as satisfaction increases with but at a decreasing rate. In this simulation, we assume the parameters , , and are 1. The choice of using one is to normalize the utility function and be able to compare other performance indicators. The total energy supply available from solar generation and battery storage is measured in kilowatts (kW). The total energy demand of each prosumer over time is measured in kilowatts (kW).

3. Simulation Results

In the simulation results, we discuss the system parameters and the different cases of optimization involving hybrid NN-MOGA, MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA. This is followed by hyper-volume convergence analysis, diversity spread analysis, error analysis, and comparative analysis of the Pareto front solution.

3.1. System Parameter

Table 1 shows the parameters used in the hybrid optimization for the MOGA optimization routine. Table 1 shows the different parameters where four prosumers were considered, with at USD 0.15 and at USD 0.10, over 24 h. The other parameters were used in the MOGA optimization process. The other criteria were set to the default settings in the optimization. The processor used in this work was an Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-8700K CPU 3.70GHz. The models were compared using the same population and generation sizes.

Table 1.

The parameters used in the hybrid optimization for the MOGA optimization routine.

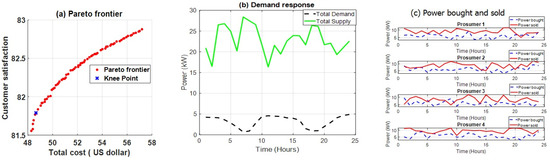

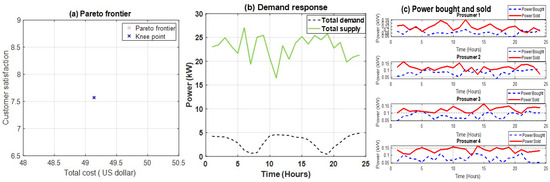

- Case 1: This case represents hybrid optimization, which produced a uniform Pareto-optimal solution. Figure 3 shows the results of the simulation for the hybrid NN-MOGA.

Figure 3. Results of hybrid NN-MOGA optimization.

Figure 3. Results of hybrid NN-MOGA optimization.

Figure 3a shows the Pareto frontier analysis results of the performance of the hybrid NN-MOGA in optimizing cost and customer satisfaction. The Pareto frontier represents the trade-off between total cost in USD and customer satisfaction. The red dots indicate the Pareto-optimal solutions, while the blue cross represents the knee point, which balances both objectives efficiently. The results show that as the total cost increased from approximately USD 48 to 58, customer satisfaction improved from 81.5 to 83. However, the knee point suggests an optimal cost–satisfaction trade-off of around USD 49 and 82 satisfaction units.

Figure 3b shows the DR performance results. The total demand and supply response over 24 h are illustrated in Figure 3b. The total demand fluctuated between 2 kW and 7 kW, indicating variations in consumer energy consumption patterns. In contrast, the total supply maintained higher values, ranging from 20 kW to 30 kW, ensuring stable energy distribution. The significant gap between supply and demand suggests availability of surplus energy that can be traded among prosumers.

Figure 3c shows the power bought and sold by four prosumers, detailing their energy trading behavior. Each sub-plot presents the power bought and power sold across 24 h. Prosumer 1 consistently sold power throughout the day, with minor purchases observed. The selling pattern remained stable, suggesting a reliable surplus. Prosumer 2 engaged in both buying and selling, indicating dynamic energy exchange. Peak sales occurred during hours 10 and 18, whereas purchases were scattered throughout the day. Prosumer 3 was similar to Prosumer 2 but exhibited lower selling peaks. Buying instances remained relatively stable, suggesting lower self-sufficiency. Prosumer 4 frequently bought power, with minimal selling instances. The energy demand was higher than its supply generation, necessitating external purchases. Hybrid optimization was possible with better Pareto distribution because of the input from the NN, which helped to predict the optimal input variable to the optimizer. Figure 4 shows the analysis results of the NN parameters for predicting solar generation.

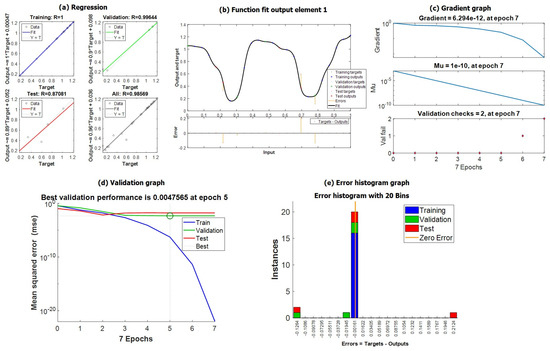

Figure 4.

Results of neural network parameters.

Figure 4a shows the regression analysis results. The NN neuron data was manually chosen in the simulation. The regression analysis evaluated the performance of the trained neural network in approximating the target function across different dataset partitions (training, validation, and test). The R-values obtained for each dataset are as follows:

- Training: R = 1.000, indicating a perfect fit between the predicted and actual values.

- Validation: R = 0.99644, suggesting that the model generalizes well to unseen data.

- Test: R = 0.87081, showing a slight decline, possibly due to limited test data or minor overfitting.

- Overall: R = 0.98569, confirming that the network maintained a high degree of accuracy across all datasets. These results indicate that the hybrid NN-MOGA model successfully captured the complex relationships in the optimization problem while maintaining high generalization performance. The NN training used early stopping when the minimum gradient was reached. Training was carried out every 5–10 min based on the optimization scheduler to update the system.

Figure 4b shows the function fit output analysis results. The function fit output graph visually compares the neural network’s predicted values with the actual target values. The following observations can be made: The training, validation, and test outputs closely followed the target function, indicating a well-fitted network. The error distribution remained small, demonstrating minimal deviation between the predicted and actual values. The fit suggests that the NN component of the hybrid NN-MOGA effectively learned the non-linear dependencies required for optimizing the multi-objective energy management problem.

Figure 4c shows the gradient and convergence performance. The gradient graph in Figure 4c shows how the network’s learning progressed during training:

- The final gradient value was 6.2941 × 10−12 at epoch 7, indicating that the training process converged. The adaptive learning parameter (Mu) was reduced to 1 × 10−10 at epoch 7, suggesting that the network no longer requires large parameter updates, reinforcing the idea of convergence stability.

- Validation checks: The training stopped at epoch 7 with only two validation failures, meaning that overfitting was successfully prevented using an early stopping mechanism. This confirms that the hybrid NN-MOGA framework effectively trained the neural network with minimal risk of overfitting while maintaining stable convergence.

Figure 4d shows the validation performance results. The validation performance curve highlights the mean squared error (MSE) trends for the training, validation, and test datasets:

- The best validation performance was achieved at epoch 5, with an MSE of 0.0047565.

- Training MSE decreased steadily, while validation and test errors remained stable, indicating good generalization. The early stopping mechanism prevented excessive training, ensuring that the model did not overfit the training dataset. This suggests that the neural network in hybrid NN-MOGA strikes a balance between learning accuracy and generalization, making it well-suited for multi-objective optimization tasks.

Figure 4e shows the error histogram analysis results. The error histogram further validates the model’s accuracy by analyzing the distribution of errors across different data subsets. Most errors are concentrated around zero, indicating a high-precision fit. Training errors dominate, with validation and test errors showing minor variations. Few outliers exist, likely due to extreme test samples or model sensitivity to minor variations in input data. This confirms that the hybrid NN-MOGA approach achieves low prediction errors, ensuring robust and accurate optimization performance.

The evaluation of the neural network parameters confirmed that the hybrid NN-MOGA framework effectively integrates neural learning with evolutionary optimization. Regression results show high accuracy across training, validation, and test datasets, with R > 0.98 overall. Function fitting analysis confirmed that the network closely approximates the target function, with minimal deviation. Gradient and convergence metrics indicate stable and early convergence at epoch 7, preventing excessive training. Validation performance was optimized at epoch 5, demonstrating efficient training without overfitting. Error histogram analysis revealed minimal prediction errors, reinforcing the reliability of the model. These findings highlight that the hybrid NN-MOGA approach successfully optimizes multi-objective problems by leveraging deep learning and evolutionary search strategies, enabling efficient decision-making in complex energy management scenarios.

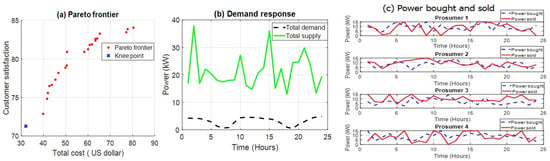

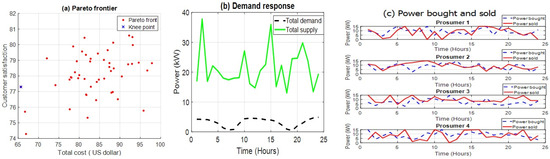

- Case 2: This case involved MOGA optimization, which produced a single-point optimal solution. Figure 5 shows the results of the simulation.

Figure 5. Results of multi-objective genetic algorithm optimization.

Figure 5. Results of multi-objective genetic algorithm optimization.

Figure 5a presents the Pareto front obtained using MOGA, with a specific focus on the knee point, which represents the most balanced trade-off between total cost and customer satisfaction. The knee-point solution was achieved at a total cost of approximately USD 49.1378 with a customer satisfaction level of 7.5710. The Pareto front is sparse, which indicates limited trade-off flexibility within the optimization process. The constrained distribution of Pareto-optimal solutions suggests that MOGA struggles to produce highly diverse solutions, leading to sub-optimal flexibility in cost–satisfaction balance.

Figure 5b illustrates the total demand and supply profiles over 24 h.

The total supply demonstrates significant fluctuation, effectively responding to varying energy demand. The total demand remained relatively stable but showed two peaks around hour 9 and hour 20, indicating periods of high energy consumption. The peak demand hours align with peak supply generation, indicating that MOGA optimization effectively schedules generation to match demand patterns, reducing dependency on external grid purchases.

Figure 5c provides an in-depth analysis of the power transactions of four prosumers, highlighting their power bought and power sold. Prosumer 1 and Prosumer 2 consistently sold more energy than they bought, indicating surplus generation capacity. Prosumer 3 and Prosumer 4 exhibited fluctuating buying and selling patterns, suggesting that their local generation intermittently met their consumption needs. Their power trading behavior was dynamic, with several peaks in power transactions occurring at hours 6, 12, and 18, aligning with changes in total demand and supply.

The results confirm that MOGA optimally schedules energy transactions, allowing prosumers to trade energy efficiently while maintaining system stability. The Pareto front obtained from MOGA is limited in diversity, reducing the range of feasible cost–satisfaction trade-offs. The demand response strategy is aligned with supply fluctuations, minimizing external grid dependency. Prosumers actively participate in energy trading, maximizing self-sufficiency and reducing overall operational costs. Despite its effectiveness, MOGA convergence performance remains limited, suggesting the potential benefits of hybridized optimization approaches, such as hybrid NN-MOGA, to improve solution diversity. These findings underscore the need for enhanced multi-objective optimization techniques to further improve energy cost efficiency and customer satisfaction in smart grid systems.

- Case 3: Figure 6 shows the results of the simulation for MOPSO optimization, which produced a well-distributed Pareto-optimal solution.

Figure 6. Results of multi-objective particle swarm optimization.

Figure 6. Results of multi-objective particle swarm optimization.

Figure 6a depicts the Pareto front solutions obtained using MOPSO, illustrating the trade-off between total cost and customer satisfaction. The knee point is located at a total cost of approximately USD 33.0403, with a customer satisfaction level of 71.2666. The Pareto front exhibits a well-distributed spread, which indicates that MOPSO effectively explores diverse trade-offs between cost and satisfaction. The solutions indicate a higher maximum customer satisfaction at approximately 85 compared to MOGA but come at the expense of increased total cost.

Figure 6b presents the total demand and supply profiles over 24 h, highlighting the DR of the energy system to varying consumption patterns. The total supply followed a fluctuating pattern, adjusting dynamically to meet demand. The total demand remained relatively stable, with peak demand periods occurring around hours 6, 12, and 18. The sharp fluctuations in total supply indicate that MOPSO efficiently schedules energy generation, ensuring that peak demand is met without significant reliance on external grid purchases.

Figure 6c illustrates the power transactions of four prosumers, detailing their power bought and power sold. Prosumer 1 and Prosumer 2 consistently sold more power than they bought, suggesting a surplus in local energy generation. Prosumer 3 and Prosumer 4 demonstrated balanced trading behavior, occasionally purchasing power to meet short-term deficits. The power transactions exhibit periodic peaks and dips, indicating active participation in the local energy market. The variability in energy trading aligns with demand fluctuations, suggesting that MOPSO enables optimal energy distribution among prosumers. MOPSO generates a well-distributed Pareto front, improving the trade-off balance between total cost and customer satisfaction compared to MOGA. DR scheduling is highly adaptive, ensuring energy supply meets demand while minimizing reliance on external sources. Prosumers actively engage in energy trading, with some maintaining energy surpluses and others balancing between buying and selling.

The results in Figure 6 indicate that a well-distributed optimal solution does not necessarily guarantee a global optimal solution in an energy system problem. While MOPSO effectively diversifies the Pareto front, its high sensitivity to local optima may limit solution convergence, suggesting the potential for hybrid models for enhanced performance. These results highlight the potential of MOPSO in optimizing energy management, demonstrating its effectiveness in minimizing costs and maximizing customer satisfaction within a distributed energy system.

- Case 4: Figure 7 shows the results of the simulation for MOFA optimization, which produced a scattered Pareto-optimal solution.

Figure 7. Results of multi-objective firefly algorithm optimization.

Figure 7. Results of multi-objective firefly algorithm optimization.

Figure 7a illustrates the Pareto front solutions derived using MOFA, depicting the trade-off between total cost and customer satisfaction. The Pareto front displays a broad distribution, indicating the exploratory capability of MOFA in identifying diverse optimal solutions. The knee point is located at approximately USD 65.6746 for total cost, with a customer satisfaction level of 77.2989, providing a balanced trade-off between objectives. The solutions are widely distributed, ranging from a total cost of USD 65 to 100, with customer satisfaction values between 74 and 81. Compared to MOGA and MOPSO, MOFA produces a more diverse solution set but at a higher cost range, suggesting a stronger emphasis on achieving higher satisfaction at increased expenses.

Figure 7b depicts the total demand and supply variations over 24 h and captures the responsiveness of the system to consumption fluctuations. The total supply exhibits substantial changes, which adjust dynamically to energy demands. The total demand follows a relatively stable pattern, with peak demand observed during early morning and evening hours. The gap between demand and supply indicates surplus energy availability, which may be leveraged for trading among prosumers. The oscillatory nature of supply suggests MOFA’s capability to handle DR efficiently, though with higher variations compared to MOPSO.

Figure 7c presents energy trading activities for four prosumers, with power bought and power sold overtime. Prosumer 1 and Prosumer 2 exhibited balanced energy trading, actively buying and selling energy throughout the day. Prosumer 3 and Prosumer 4 demonstrated periods of net energy surplus, where power sales exceeded purchases. Fluctuations in power transactions suggest dynamic market participation, with energy exchanges closely aligning with demand fluctuations. MOFA ensured that prosumers engage in energy trading more consistently compared to MOPSO, preventing excessive reliance on external grid energy. MOFA generated a widely distributed Pareto front, providing diverse trade-off solutions but at the expense of increased total costs. The DR system was effectively managed, with supply fluctuating dynamically to meet consumption needs. Prosumers exhibited active trading behaviors, with some maintaining energy surpluses and others engaging in periodic transactions. The higher variability in supply suggests a potential need for hybrid optimization techniques to refine solution stability. The results indicate that MOFA effectively balances cost and customer satisfaction, making it a viable approach for energy optimization in smart grid environments.

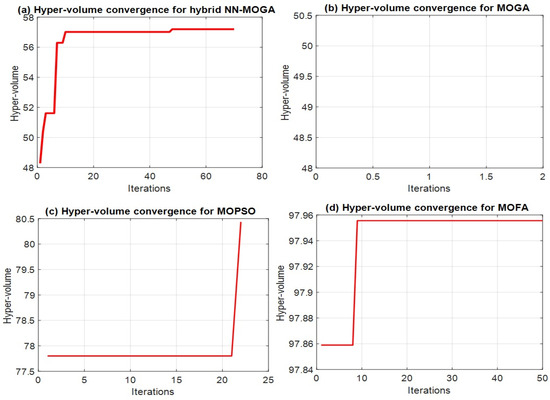

3.2. Hyper-Volume Convergence Analysis

HV is a critical metric for evaluating the performance of multi-objective optimization algorithms. It measures the volume covered by the obtained Pareto front relative to a predefined reference point, with higher HV values indicating better convergence and diversity of solutions. Figure 8 presents the HV convergence trend for four different algorithms: hybrid NN-MOGA, MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA.

Figure 8.

Hyper-volume convergence of Pareto front.

Figure 8a shows the HV for hybrid NN-MOGA optimization. The HV increased rapidly in the initial iterations and gradually stabilized around 56.8 after approximately 40 iterations, suggesting that the hybrid model achieves a balanced Pareto front with good diversity and convergence speed. Figure 8b shows the HV for the MOGA optimization. The HV showed no increase, with no significant improvement beyond the first iteration. This suggests that MOGA struggles to improve the solution quality compared to the other algorithms, since it shows a single-point solution, which is not desirable in practical terms. Figure 8c shows the HV for MOPSO optimization. The HV remained nearly constant for the first 20 iterations before a sharp increase to 80.5, indicating slow initial convergence followed by rapid improvement. Figure 8d shows the HV for MOFA optimization. The HV rapidly converged within the 10 iterations and stabilized at 97.96, demonstrating fast convergence and high solution quality.

The results indicate that MOFA outperformed the other algorithms in terms of convergence speed and final HV value. MOPSO showed late significant improvement, while hybrid NN-MOGA provided a stable increase but reached a lower HV compared to MOFA. MOGA, however, failed to achieve competitive HV values, highlighting its limitations in this problem domain.

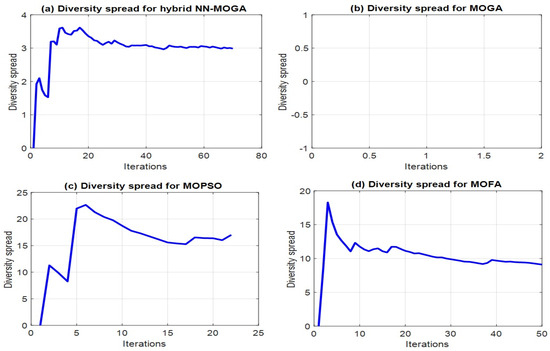

3.3. Diversity Spread Analysis

DS is a key metric that quantifies the distribution of Pareto-optimal solutions in multi-objective optimization. A higher diversity spread indicates a well-distributed Pareto front, which enhances the decision-making process by providing a diverse set of trade-off solutions. Figure 9 illustrates the diversity spread trends for hybrid NN-MOGA, MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA.

Figure 9.

Diversity spread of Pareto front.

Figure 9a shows DS for hybrid NN-MOGA optimization. The DS exhibits a rapid initial increase, stabilizing around 3.0 after approximately 20 iterations. This suggests that the hybrid approach maintains a consistent and well-distributed Pareto front, which remains stable throughout the optimization process. Figure 9b shows DS for MOGA optimization. The DS appears non-existent, suggesting that MOGA failed to generate diverse solutions or converged prematurely to a narrow region of the Pareto front. This highlights a significant limitation of MOGA in maintaining solution diversity. Figure 9c shows DS for the MOPSO optimization: The DS rises sharply in the early iterations, reaching a peak around 22, followed by a gradual decline and stabilization around 15. This indicates that while MOPSO initially explores a wide solution space, it tends to lose diversity over time. Figure 9d shows the DS for MOFA optimization. The DS started high at approximately 19 but declined as iterations progressed, stabilizing around 10. This suggests that while MOFA initially provides a diverse solution set, it progressively focuses on a more compact Pareto front.

The results indicate that hybrid NN-MOGA maintained the most stable diversity throughout the optimization process, whereas MOGA failed to ensure any diversity. MOPSO achieved a high DS at the initial stage but declined over time, while MOFA started with high diversity but gradually converged to a more focused solution set. These findings suggest that hybrid NN-MOGA and MOFA are better suited for problems that require both diversity and convergence, whereas MOPSO may need diversity preservation strategies.

3.4. Error Analysis

The errors from the different optimization were also calculated. Table 2 presents the error analysis results of the Pareto front for hybrid NN-MOGA, MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA.

Table 2.

Error analysis results of the Pareto frontier objective function.

From the results in Table 2, we compared the accuracy of hybrid NN-MOGA to minimize total cost and maximize customer satisfaction against conventional optimization methods, including MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA. The analysis was conducted using two key error metrics, the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE), as presented in Table 2. The MAE values indicate the average absolute deviation between the predicted and actual values for both total cost and customer satisfaction. The results show that hybrid NN-MOGA achieved the lowest MAE for both objectives, with USD 2.7713 for total cost and 0.42825 for customer satisfaction, demonstrating superior predictive accuracy. MOGA exhibited the highest error in total cost estimation, with USD 45.786, but performed reasonably well in customer satisfaction prediction, with 81.471.

MOPSO and MOFA yielded moderate performance, with MAE values significantly higher than that of hybrid NN-MOGA, particularly in total cost estimation, with USD 12.928 and 25.627. The RMSE values further reinforce the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid NN-MOGA approach; hybrid NN-MOGA again achieved the lowest RMSE at USD 2.8408 for total cost and 0.45393 for customer satisfaction, confirming its robustness in minimizing cost while maximizing satisfaction. MOGA demonstrated the highest RMSE in total cost, with USD 49.971, suggesting large deviations in cost predictions. MOPSO and MOFA performed better than MOGA but remained significantly less accurate than hybrid NN-MOGA, particularly in customer satisfaction, with RMSE values of 6.4825 and 4.8207, respectively. The results indicate that hybrid NN-MOGA outperformed all other methods in both total cost minimization and customer satisfaction maximization. The significantly lower MAE and RMSE values confirm the efficiency of the hybrid neural network approach in achieving a well-balanced Pareto front. These improvements demonstrate the potential of hybrid NN-MOGA in optimizing energy management strategies while ensuring high customer satisfaction at a minimal cost.

3.5. Knee-Point Analysis

The knee point represents the best trade-off between total cost and customer satisfaction. The hybrid NN-MOGA achieved a knee-point total cost of USD 48.28 with optimal customer satisfaction of 81.79. MOGA achieved a similar cost of USD 49.14 but performed extremely poorly, with customer satisfaction of 7.57. MOPSO and MOFA yielded mixed results, with MOPSO minimizing costs to USD 33.04 but only achieving 71.27 in customer satisfaction, while MOFA exhibited high satisfaction of 77.29 at a much higher cost of USD 65.67. Table 3 shows the difference between the Pareto front features for the four optimization techniques. This table compares the Pareto front spread, the convergence, diversity, and accuracy of the curve.

Table 3.

Comparison of the Pareto front features for different algorithms.

From the results in Table 3, we can conclude that the hybrid optimization performed better than the three other multi-objective optimization algorithms. Hybrid NN-MOGA optimization achieved a uniformly spread Pareto front, excellent convergence, excellent diversity, and accuracy. MOGA achieved the worst Pareto spread, with a single-point value solution, poor convergence, low diversity, and sub-optimal accuracy. MOPSO performed better, with a well-distributed Pareto front spread, strong convergence, high diversity, and accuracy. MOFA achieved a scattered Pareto front point, with relatively moderate convergence, high diversity, and moderate accuracy. In the case of energy management, hybrid optimization offers a better and improved approach to finding the Pareto-optimal solution. The NN helps to continuously predict the load and solar generation parameters and achieve a better optimal solution in terms of reduced cost and higher customer satisfaction.

4. Conclusions

This study evaluated the economic performance of hybrid NN-MOGA in comparison to conventional MOGA, MOPSO, and MOFA to optimize energy management in a smart grid environment. Key performance metrics, including HV convergence, DS, accuracy metric, convexity, and satisfaction of Karush–Kuhn–Tucker (KKT) conditions, were analyzed to assess solution quality and stability. The results demonstrate that hybrid NN-MOGA effectively balances total cost minimization and customer satisfaction maximization while ensuring a well-distributed Pareto front with enhanced convexity. The proposed approach improves the demand–supply balance, mitigating extreme fluctuations in energy availability and reducing grid dependency. Unlike MOPSO and MOFA, which exhibited significant variations in supply, hybrid NN-MOGA enhanced energy distribution stability, leading to more reliable operational outcomes. Furthermore, the method achieved superior diversity spread and HV convergence, ensuring efficient exploration and exploitation of the solution space with reduced computational overhead. The convexity of the Pareto front in hybrid NN-MOGA also strengthens decision-making reliability by providing consistent energy cost predictions. Moreover, the satisfaction of the KKT conditions confirms the mathematical optimal and practical feasibility of the solutions obtained. Hybrid NN-MOGA significantly enhances computational efficiency, achieving a favorable trade-off between solution quality and execution time compared to traditional methods. This study establishes hybrid NN-MOGA as a robust and efficient optimization framework for smart grid energy management. Future work will focus on improving real-time adaptability and integrating deep reinforcement learning techniques in dynamic pricing to further improve stability in dynamic grid environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.O.; methodology, C.E.O.; software, C.E.O.; validation, R.G. and Y.C.; formal analysis, C.E.O.; investigation, C.E.O.; resources, Y.C.; data curation, R.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.E.O.; writing—review and editing, R.G.; visualization, R.G.; supervision, Y.C.; project administration, Y.C.; funding acquisition, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2023S1A5C2A07096111).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Numerical solution

Proof of convexity, KKT condition, and Lagrangian function.

For function , if the second derivative is greater than or equal to zero for all in the domain, the function is convex at that interval.

Objective function 1:

KKT conditions.

Lagrangian function: Let the Lagrangian be .

Lagrangian: Equality constraint (power balance):

Inequality constraint (battery capacity):

where , , , , and are Lagrange multipliers for the respective constraints .

Stationary KKT conditions:

Convexity analysis for the objective function is expressed as

The objective function is a linear function based on their respective variables. A linear function is both convex and concave. Therefore, the function is convex.

Objective function 2: Let be represented by . The first and second derivatives of are required to analyze its convexity.

First derivative:

Second derivative:

where and are represented in (27) and (28), respectively.

After deriving the solution, Equation (A16) is a complex expression; for convexity, it is required that .

Convexity condition and Lagrange multipliers:

The sign of the second derivative determines convexity. If is non-negative for all in the domain, is convex. If and are such that the function is always increasing at a diminishing rate, the function can exhibit diminishing returns and still be convex or concave.

We employed numerical analysis to definitively determine the convexity based on the chosen parameters , , and . If the parameters are all 1, then the .

The Lagrange multipliers for a constrained optimization problem of the form is given as

Subject to constraints:

The Lagrangian function is defined as

where and are the Lagrange multipliers.

KKT conditions: For the satisfaction function, we write the KKT conditions as follows:

Primal feasibility:

Dual feasibility:

Complementary slackness:

KKT condition for our specific satisfaction function:

Primal feasibility: This depends on the specific constraints and , for example,

Dual feasibility:

Complementary slackness:

Convexity: The satisfaction function is not necessarily convex or concave without specific parameter constraints and requires further analysis. The convexity can be determined from Equation (A27). Convexity simplifies finding optimal solutions within the feasible regions and ensures that the global minimum is found, helping predictable MG operation.

Knee point

The knee point of a Pareto front is the optimal solution where there is a significant trade-off between the objectives. A slight deviation from this point will result in a large deterioration in at least one objective. This is known as the balance point. It can be calculated by minimizing the Euclidean distance from the ideal point.

The knee point of the Pareto front can be calculated as follows:

where is the distance from ideal point, is the number of objectives, is the -th objective value for the solution , and is the -th component of the ideal point .

Therefore, the knee point is

Accuracy metrics calculation:

The mean absolute error (MAE) is calculated as

where is the objective value from the algorithm, is the benchmark value, which is the knee point on the Pareto front, and is the number of solutions in the Pareto front.

Root mean square error (RMSE):

The root means square error (RMSE) is calculated as

References

- Gaggero, G.B.; Girdinio, P.; Marchese, M. Artificial intelligence and physics-based anomaly detection in the smart grid: A survey. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 23597–23606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reka, S.S.; Dragicevic, T.; Venugopal, P.; Ravi, V.; Rajagopal, M.K. Big data analytics and artificial intelligence aspects for privacy and security concerns for demand response modelling in smart grid: A futuristic approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Chiu, W.Y.; Sun, H.; Poor, H.V. Multiobjective optimization for demand side management program in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2017, 14, 1482–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, Z.; Cai, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, B. Renewable-based microgrids’ energy management using smart deep learning techniques: Realistic digital twin case. Sol. Energy 2023, 250, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, C.E.; Kharatovi, L.; Sias, Q.A.; Gantassi, R.; Choi, Y. Minimizing Electricity Cost in Energy Trading Using Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the Korean Institute of Communications and Information Sciences Conference, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 6–8 September 2023; pp. 496–497. Available online: https://www.dbpia.co.kr/Journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE11667374 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Zaini, F.A.; Sulaima, M.F.; Razak, I.A.W.A.; Zulkafli, N.I.; Mokhlis, H. A review on the applications of PSO-based algorithm in demand side management: Challenges and opportunities. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 53373–53400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wang, Z.; Gao, W.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Q. Adaptive multi/many-objective transformation for constrained optimization. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 55, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.F.; Wang, J. A collaborative neurodynamic approach to multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2018, 29, 5738–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Meegahapola, L.; Vahidnia, A.; Datta, M. Stability and Control Aspects of Microgrid Architectures–A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 144730–144766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.; Saxena, D. Comprehensive review on control schemes and stability investigation of hybrid AC-DC microgrid. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 218, 109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, A.M.; Jasim, B.H.; Flah, A.; Bolshev, V.; Mihet-Popa, L. A new optimized demand management system for smart grid-based residential buildings adopting renewable and storage energies. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4018–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Khan, M.; Wijesinghe, R.; Wijenayake, U. Meta-heuristic optimization based cost efficient demand-side management for 771sustainable smart communities. Energy Build. 2024, 303, 113599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, E.; Halder, P.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, E.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Progress on the demand side management in smart grid and optimization approaches. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 36–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, D. A survey on information communication technologies in modern demand-side management for smart grids: Challenges, solutions, and opportunities. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2022, 51, 76–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.M.; Atef, M.; Sarkar, M.R.; Uddin, M.; Shafiullah, G.M. A Review on peak load shaving in microgrid—Potential benefits, challenges, and future trend. Energies 2022, 15, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, A.; Karimi, H.; Jadid, S. Hybrid day-ahead and real-time energy trading of renewable-based multi-microgrids: A stochastic cooperative framework. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 40, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, R.; Gantassi, R.; Ahmed, N.; Alshehri, A.H.; Alsubaei, F.S.; Frnda, J. A hybrid approach for adversarial attack detection based on sentiment analysis model using Machine learning. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 78558, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, V.; Rabelo, R.; Carvalho, A.; Floris, A.; Pilloni, V. On the Impact of Flexibility on Demand-Side Management: Understanding the Need for Consumer-Oriented Demand Response Programs. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 7882024, 8831617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Ai, Q.; Piao, L. Bargaining-based cooperative energy trading for distribution company and demand response. Appl. Energy 2018, 226, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dong, H.; Lin, J.; Zeng, M. Multi-objective optimal scheduling model with IGDT method of integrated energy system considering ladder-type carbon trading mechanism. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 143, 108386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajalli, S.Z.; Weckesser, T.; Bindner, H. A framework for assessing the participation of aggregated flexible loads in power markets. In Proceedings of the IEEE Power & Energy Society Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 14–17 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Akkouch, R.; Menci, S.P.; Pavic, I. Congestion Management in European Electricity Systems Through Aggregators and Local Flexibility Markets: A Systematic Literature Review. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Istanbul, Turkiye, 10–12 June 2024; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.K. Regional Dimensions of Human Development in India and South Africa: Through Sustainable Development Goals; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.D. Consumer-Oriented Distributed Energy Policy for Korea: Based on a Case Study of Victoria, Australia. Int. Reg. Res. 2024, 28, 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa, A.; Gibson, D.V. Technology-Based Regional Economic Development: Institutional Perspectives from the United States and Japan; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- García-Santacruz, C.; Gómez, P.J.; Carrasco, J.M.; Galván, E. Multi P2P energy trading market, integrating energy storage systems and used for optimal scheduling. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 64302–64315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, E.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—A review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakadhurga, D.; Prabaharan, N. Demand side management in microgrid: A critical review of key issues and recent trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 156, 111915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharrich, M.; Mohammed, O.H.; Alshammari, N.; Akherraz, M. Multi-objective optimization and the effect of the economic factors on the design of the microgrid hybrid system. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Sun, L.; Wang, J. Multi-objective optimization scheduling considering the operation performance of islanded microgrid. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 83405–83413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, A.; Nezhad, M.M.; Keynia, F.; Fekih, A.; Shahsavari-Pour, N.; Garcia, D.A.; Piras, G. A combined multi-objective intelligent optimization approach considering techno-economic and reliability factors for hybrid-renewable microgrid systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M. Detailed study, multi-objective optimization, and design of an AC-DC smart microgrid with hybrid renewable energy resources. Energy 2019, 169, 496–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riou, M.; Dupriez-Robin, F.; Grondin, D.; Le Loup, C.; Benne, M.; Tran, Q.T. Multi-objective optimization of autonomous microgrids with reliability consideration. Energies 2021, 14, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, W.; Wang, D.; Ding, M. A Multi-Objective optimization dispatch method for microgrid energy management considering the power loss of converters. Energies 2019, 12, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, A.M.; Fakhar, A.; Helwig, A. Sustainable energy planning for cost minimization of autonomous hybrid microgrid using combined multi-objective optimization algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivam, K.; Tzou, J.C.; Wu, S.C. A multi-objective predictive energy management strategy for residential grid-connected PV-battery hybrid systems based on machine learning technique. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 237, 114103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chithra, S.; Arunachalaperumal, C.; Rajagopal, R.; Meenalochini, P. Hybrid optimization for energy management in smart grids using Golden Jackal algorithm and deep convolutional neural networks. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 8201–8215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Cai, Q.; Cai, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, S. Modeling and Prediction of Demand Response Based on Deep Quantum Neural Networks. Int. J. High Speed Electron. Syst. 2025, 34, 2540332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, S.O.; Sheykhha, S.; Madlener, R. An integrated two-level demand-side management game applied to smart energy hubs with storage. Energy 2020, 206, 118017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Mohanty, S.; Rout, P.K.; Sahu, B.K.; Bajaj, M.; Zawbaa, H.M.; Kamel, S. Residential Demand Side Management model, optimization and future perspective: A review. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 3727–3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, C.; Villavicencio, M. The demand-side flexibility in liberalised power market: A review of current market design and objectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 201, 114643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccino, F.; Grillo, S.; Massucco, S.; Mauri, G.; Mora, P.; Silvestro, F. An aggregator for demand side management at domestic level including PEVs. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Electric Vehicle Conference (IEVC), Florence, Italy, 17–19 December 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sias, Q.A.; Gantassi, R.; Choi, Y. Multivariate bidirectional gate recurrent unit for improving accuracy of energy prediction. ICT Express 2024, 11, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, P.; Vinopraba, T.; Chandrasekaran, K. Deep learning based real time Demand Side Management controller for smart building integrated with renewable energy and Energy Storage System. J. Energy Storage 2023, 58, 106412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, C.E.; Gantassi, R.; Choi, Y. Application of artificial intelligence in minimizing voltage deviation using neural network predictive controller. In Model and Data Engineering; Ordonez, C., Sperlì, G., Masciari, E., Bellatreche, L., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 158–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pournazarian, B.; Seyedalipour, S.S.; Lehtonen, M.; Taheri, S.; Pouresmaeil, E. Virtual impedances optimization to enhance microgrid small-signal stability and reactive power sharing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 139691–139705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi, C.E.; Gantassi, R.; Choi, Y. Artificial intelligence driven digital twin for dynamic pricing model in hybrid optimization. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Peng, Y.; Sun, J. Dual-Stage Optimization Scheduling Model for a Grid-Connected Renewable Energy System with Hybrid Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannelos, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Strbac, G. Multi-Objective Optimization for Pareto Frontier Sensitivity Analysis in Power Systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).