Abstract

For the purpose of Fitness-For-Service analysis, the effect of a semi-elliptical surface crack on a parallel quarter-circle corner crack in a semi-infinite solid subjected to pure bending is studied using 3D finite element analyses. While keeping the geometry of the quarter-circle corner crack constant, the SIF distributions along its front are studied for various geometrical configurations of the semi-elliptical surface crack and several crack layouts. The problem is solved for a wide range of parameters, e.g., the ellipticity of the semi-elliptical b1/a1 = 0.1~1; the relative crack size of the two parallel cracks a1/a2 = 1/3~2; the normalized vertical and horizontal gaps between the two cracks, H/a2 = 0.4 and 1.2, and S/a2 = −0.5 and 1, respectively. The results indicate that the semi-elliptical surface crack might have a considerable effect on the SIF distribution along the quarter-circle corner crack both in amplifying and reducing the SIF. These effects are highly dependent on the semi-elliptical surface crack geometry and the cracks’ configuration. It is further concluded that it is necessary to perform a full 3D analysis, similar to the present one, in order to quantify the “real” effect of neighbouring cracks, in view of the existing inadequate fitness for service criteria.

1. Introduction

Fitness-for-service (FFS) models are engineering assessments used to evaluate the structural integrity and fitness of a component or structure for continued service in petrochemical facilities, power plants, military and other industrial settings. These models are essential for ensuring the safe operation and reliability of equipment, especially when the components may have been exposed to various damage mechanisms or aging. The main purpose of FFS models is to determine whether a component can remain in service, or needs repair or replacement.

A detailed description of fitness-for-service models typically involves the following nine key components:

- Damage Mechanisms: FFS models consider various damage mechanisms that can affect the integrity of the component such as cracking, fatigue, corrosion, deformation, erosion, creep, and other potential failure modes. Understanding the specific damage mechanisms is crucial in determining the appropriate assessment methodology.

- Inspection Data: Inspection data of the component are gathered to assess the extent of damage or degradation. This may involve non-destructive testing (NDT) techniques such as ultrasonic testing, magnetic particle testing, radiography, and visual inspections. The data is used to identify the size, location, and severity of defects or damages.

- Fitness Criteria: Each component has specific acceptance criteria that define the limits of acceptable damage based on industry standards, regulations, and engineering codes. For example, API 579/ASME FFS-1 [1], is a widely used standard providing guidance for evaluating the fitness of pressure vessels, piping, and tanks.

- Assessment Techniques: Different FFS assessment techniques are applied depending on the damage mechanism and component type. Common techniques include three levels of assessments: First, a preliminary assessment based on simplified methods and conservative assumptions to quickly determine if more detailed analysis is necessary. Second, a more detailed analysis using advanced engineering methods and fracture mechanics to quantify the remaining strength and life of the component. Third, comprehensive and rigorous analyses involving the finite element method (FEM), computational fluid dynamics (CFD), and other advanced numerical techniques for complex scenarios.

- Material Properties: Accurate material properties are essential for FFS models. This includes understanding the mechanical properties of the material such as strength, toughness, fatigue resistance, etc.

- Operating Conditions: FFS models take into account the operating conditions of the equipment, such as temperature, pressure, and load, as these factors can influence the behavior of the component.

- Failure Modes and Consequences: FFS models consider the potential failure modes of the component and assess the consequences of failure on personnel safety, the environment, and production processes.

- Remaining Life Assessment: Based on the assessment results, FFS models estimate the remaining life of the component, providing crucial information for maintenance planning and scheduling.

- Repair and Replacement Recommendations: If the component does not meet the fitness criteria, the FFS model may provide recommendations for repair, mitigation measures, or replacement.

In summary, fitness-for-service models play an important and vital role in ensuring the continued safe and reliable operation of industrial equipment. These models help plant operators and engineers make informed decisions regarding the structural integrity of components, thereby preventing potential failures, minimizing downtime, and enhancing overall operational efficiency.

Over time, as plant components degrade, they may contain multiple cracks, resulting from fatigue, stress corrosion, etc. [2,3]. In order to apply any of the FFS standards, based on fracture mechanics concepts, it is necessary to determine the prevailing crack configuration, including the relative location and orientation of the cracks, as well as their shape and size. Such information is necessary for the assessment of the FFS of the machine part in question.

One of the most simplified crack configurations is the case of two adjacent cracks. In this simplified case, the major question is whether the two cracks need to be considered simultaneously, as they interact with each other, or whether they can be treated separately. Multiple alignment criteria have been suggested to resolve this question including: the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code Section XI (ASME Section XI) [4]; the Guide to Methods for Assessing the Acceptability of Flaws in Metallic Structures [5]; the European Fitness-for-Service Network (FITNET) FFS procedure [6]; the American Petroleum Institute (API) 579-1/ASME FFS-1 [1]; and the Rules on Fitness-for-Service for Nuclear Power Plant Components in the Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers (JSME, S NA1-2008) [7]. As these rules may differ considerably from each other, some of them may yield conservative results, while others may provide non-conservative results, in treating a particular case.

Several investigators attempted to address this problem, looking for alignment criteria for multiple internal cracks. Such models were suggested by Kamaya [8], Hasegawa et al. [9,10,11], Miyazaki et al. [12], and Suga et al. [13,14] among others. In recent years, several numerical and experimental studies considering crack interaction, were performed by Kikuchi [15], Toribio et al. [16] and very recently by Cheng et al. [17], Ferrian et al. [18], and Wang et al. [19]. Some of these works focus on fatigue crack growth of multiple cracks and even crack coalescence. Until recently, the mutual interaction of a 3D Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack (SESC) and a non-aligned Quarter- Circle Corner Crack (QCCC) were not considered. Preliminary studies of the interaction of this crack configuration under remote tension were performed by Perl et al. [20] and Levy et al. [21] and under in-plane bending by Levy et al. [22] and Ma et al. [23].

Based on the preliminary results of [22,23], it is the purpose of the present study to perform a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between a 3D semi-elliptical surface crack, and an adjacent non-aligned quarter-circle corner crack in a semi-infinite solid under in-plane bending. The analysis takes into consideration the characteristic parameters of the problem, i.e., the absolute and the relative size of the two cracks, the horizontal and vertical gaps between the cracks, and the surface crack ellipticity. The linear elastic fracture mechanics analysis is performed via the Finite Element Method (FEM) applying the ANSYS 12 code [24]. In Part I of this two-part paper, the influence of the surface crack on the QCCC will be evaluated. Part II of this two-part paper deals with the effect of the QCCC on the semi-elliptical surface crack.

2. The Three-Dimensional Analysis

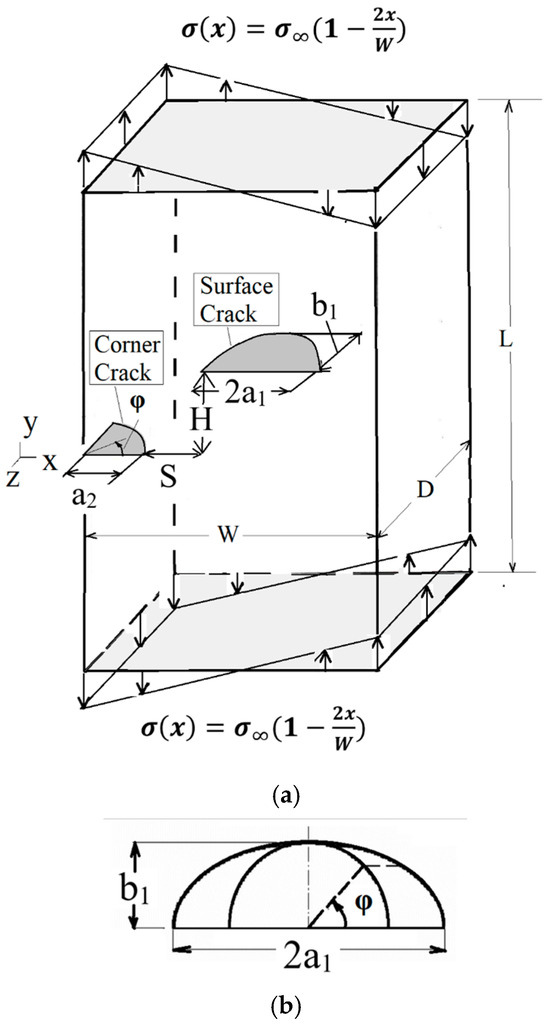

Figure 1a depicts a semi-infinite solid, very large with respect to the crack configuration, i.e., (L, W, D >> a2 + S + 2a1) subjected to in-plane bending. A quarter- circle corner crack, of radius a2, and a semi-elliptical surface crack, of half-length a1 and depth b1, are located on parallel planes perpendicular to the bending load. The horizontal gap between the cracks is S and the vertical gap is H. Figure 1b represents the definition of the parametric angle φ.

Figure 1.

A 3D view of the cracked solid under in-plane bending. (a) The definition of the geometrical and loading parameters of the non-aligned interacting semi-elliptical surface crack quarter- circle corner crack. (b) The definition of the parametric angle φ.

The solid is assumed to be elastic and made of steel with Young’s modulus E = 200 GPa, Poisson’s ratio υ = 0.3. The maximum applied remote stress for all the configurations herein studied is σ∞ = 2 kPa. To avoid any size effect, the width of the solid is taken to be W = 50 ∗ (a2 + S + 2a1) [20], much larger than the total spacing between the two cracks’ extreme end points, so that the solid’s depth, D, and height, L, are taken to be equal the width, i.e., D = L = W.

The Finite Element Model

The standard Finite Element code ANSYS is used to solve the model [24]. The solution is performed in two steps using the submodeling technique (for a detailed description of the submodeling technique see, for example, [22]). In the first step, a global mesh of the entire solid is created using 10-node tetrahedron elements, (SOLID92) [20]. The elements close to the cracks are chosen to be small and their size is gradually increased when moving away from the cracks’ region. In the second step, two separate submodels are created for each of the cracks. The “submodel” is toroid-like covering the complete crack front of each of the cracks. Each of the “submodels” is meshed with three layers of 20-node isoparametric solid brick elements (SOLID95).

In the case of the quarter-circle corner crack, the crack front extends along φ = 0–90°, and thus, the first layer consists of 160 collapsed isoparametric elements, creating a layer of singular “wedges” along the crack’s front. Above this layer, are two more layers of 20-noded isoparametric elements. The sub-model in this case consists of a total of 6543 degrees of freedom (DOF), enabling the accurate evaluation of the SIF distribution at intervals of 9° along the crack front.

In the case of the semi-elliptical surface crack, the crack front extends along φ = 0–180°, and, thus, the first layer consists of 320 collapsed isoparametric elements, creating a layer of singular “wedges” along the crack’s front. Above this layer, are two more layers of 20-noded isoparametric elements. The sub-model in this case consists of a total of 13,086 DOF, enabling evaluation of the SIF distribution along the crack front at the same 9° intervals, with the same accuracy as in the previous case.

The SIF distributions along the fronts of the two cracks are evaluated by the ANSYS KCALC procedure [24]. To provide accurate and reliable results, convergence tests were performed using the stress intensity factor as the convergence criterion. It is anticipated that the level of error is within less than 3% for meshes having more than 200,000 DOFs, with about half of them being assigned to the small volume around the cracks.

3. Results and Discussion

The mutual impact of the corner crack and the surface crack is found to depend on multiple factors, viz. the geometrical configuration of the cracks including: the radius of the QCCC, a2; the ellipticity of the surface crack, b1/a1; the relative size of the two cracks, a1/a2; and the normalized horizontal and vertical gaps between the two cracks, S/a2 and H/a2, respectively.

In this entire study, the size of the QCCC is kept fixed a2 = 15 mm, while the size of the SESC is varied a2 = 10–30 mm, resulting in relative crack sizes of a1/a2 = 2/3 to 2. Furthermore, solutions are obtained for various ellipticities of the surface crack namely b1/a1 = 0.1–1.

In the case of 3D elliptical cracks, SIFs are commonly normalized with respect to:

where σ, is the remote tensile stress; a is the semi-crack length of the elliptical surface crack, c is the semi-elliptical surface crack depth, and Q is a dimensionless shape factor, defined by the crack ellipticity c/a (see [25]).

Furthermore, as in our case, the corner crack is a quarter-circle with a radius of a2, therefore Equation (1) reduces to the exact SIF of a penny-shaped crack [26]:

where σ∞ is the maximum applied tensile stress. Therefore, all the SIFs provided in this paper are normalized to K0 of Equation (2).

3.1. The Solitary Quarter-Circle Corner Crack

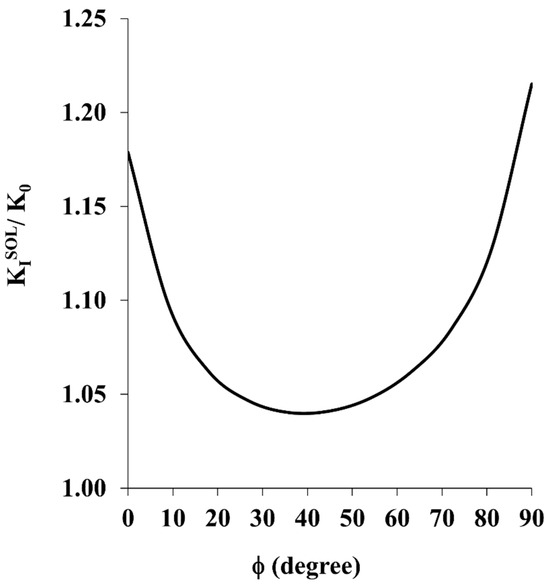

In order to analyze the effect of the semi-elliptical surface crack on the quarter-circle corner crack, it is necessary first to evaluate the SIFs distribution along the front of a solitary quarter-circle corner crack in the absence of the SESC. The solution for the solitary QCCC will serve as the reference solution in the coming analysis. The distribution of the normalized SIF of a solitary QCCC subjected to bending moment is obtained by the FE analysis, and is presented in Figure 2. In contrast to the case for an identical crack configuration under pure tension [25], the SIF distribution in the bending case is not symmetric, bearing its maximum at φ = 90°.

Figure 2.

The Normalized Stress Intensity Factor Distribution along the Front of a Solitary Quarter-Circle Corner Crack.

In order to validate the FE model, the present result for KI/K0 at φ = 90° should be equal to the solution of an identical QCCC subjected to pure tension, which has an “exact” analytical solution [27]. The present result at φ = 90° is found to be in very good agreement, within less than 2% of the analytical solution the accuracy of which is 3% (see [27]). Furthermore, the accuracy of the entire distribution of KI/K0 for the solitary crack (φ = 0–90°) is estimated to be about 3%.

3.2. The Effect of the Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack on the QCCC for Similar Crack Sizes

The effect of the SESC on the QCCC is analyzed in this section for cases of similar crack sizes a1 = a2 = 15 mm, i.e., the semi-length of the surface crack equals the radius of the QCCC. The surface crack’s ellipticity is varied between a shallow crack, b1/a1 = 0.1, and a semi-circular one, b1/a1 = 1.0, and several normalized cracks gaps, H/a2 and S/a2, are considered in the cases solved.

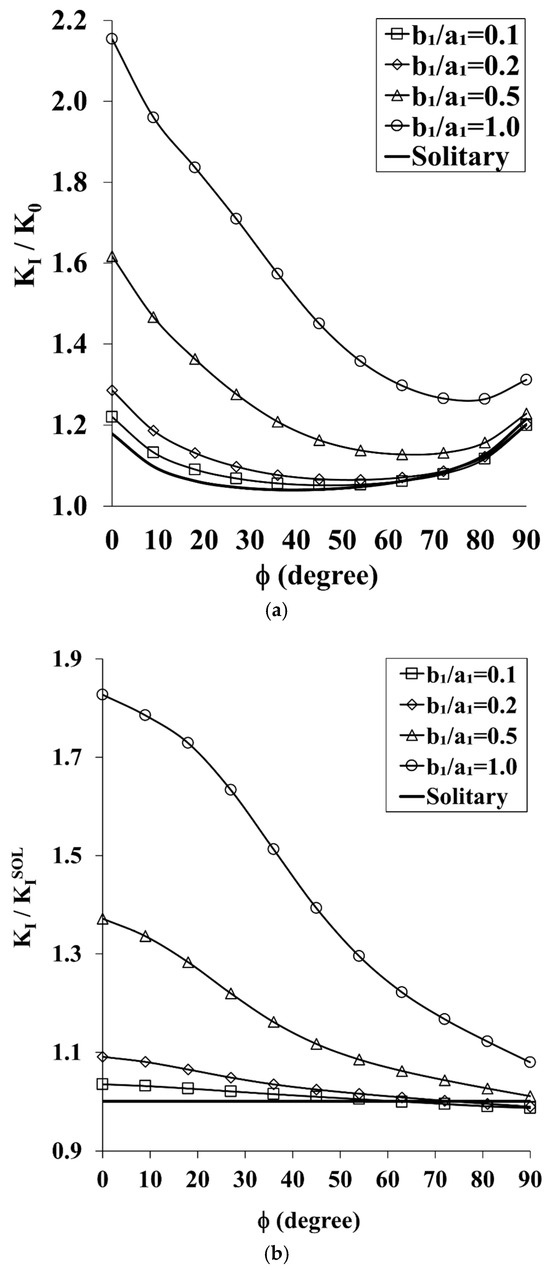

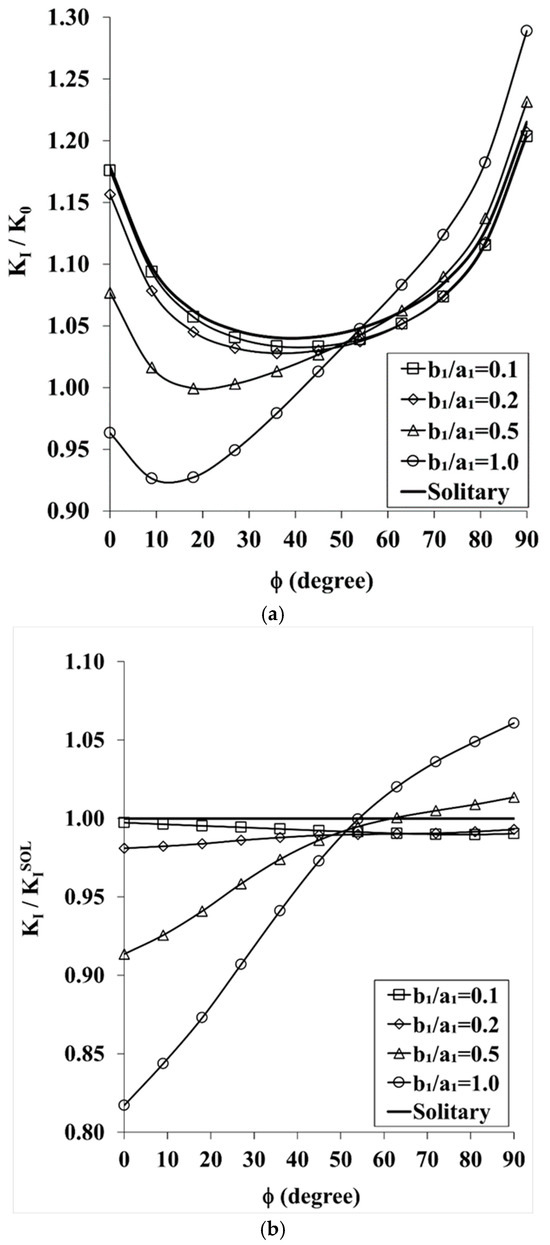

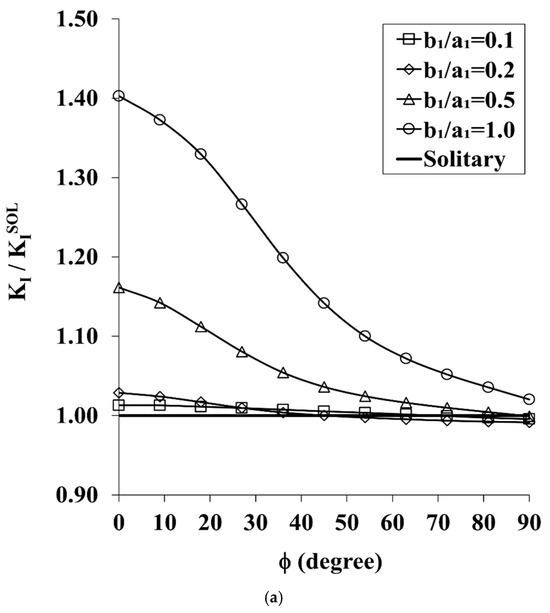

3.2.1. Case I—Horizontally Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

In the first case, the SESC partially overlaps the QCCC as the horizonal gap is taken as S/a2 = −0.5. The cracks are considered overlapped if S/a2 < 0. The normalized SIF distribution along the front of the quarter-circle corner crack is given in Figure 3a for various geometrical configurations as detailed in the legend of the figure. A curve representing the SIF distribution for the solitary crack is added as our reference case, and is represented by the bold curve in the graph.

Figure 3.

(a). The Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5).

A qualitative analysis of the results in Figure 3a shows that the effect of the presence of the SESC on the QCCC, can either amplify or attenuate the SIF, depending on the particular ellipticity of the SESC. In the case of deep SESCs, b1/a1 ≥ 0.5, the SIF along the entire front of the QCCC is intensified by the presence of the SESC with a maximum increase at φ = 0°. However, in the case of shallow SESCs, b1/a1 = 0.1 and 0.2, the SIF is amplified along part of the QCCC front, while attenuated along the rest of it, as can be seen by the dipping of the b1/a1 curves below the solitary crack curve. The reduction in the SIF along part of the QCCC front is a result of the shielding effect the SESC has on the QCCC [28]. A “Shielding Effect” occurs when an adjacent crack attenuates the SIF at the tip of the other crack [29]. In our present case, for b1/a1 = 0.1, shielding occurs for φ ≥ 54°, while for b1/a1 = 0.2 it occurs only for φ ≥ 72°, while their maximum amplification occurs at φ = 90°, i.e., at the free surface.

In order to quantitatively evaluate these results, the distributions of the SIF along the front of the QCCC is re-normalized to the values of the solitary crack, KI, and presented in Figure 3b, and it can observed that in the case of the shallowest crack, b1/a1 = 0.1, for φ ≥ 54° the SIF is reduced by no more than 1.3%, while for φ ≤ 54°, the SIF is amplified by up to 3.5% at φ = 0°. A similar behaviour is noticed for the case of b1/a1 = 0.2 where attenuation in the SIF is no more than 1.1%, and occurs only along a small part of the QCCC front, namely φ ≥81°, while along most of the crack front, the SIF is amplified by up to 9.1% at φ = 0°.

For larger ellipticities of the SESC, b1/a1 = 0.5 and 1, the SIF distribution for the QCCC is entirely amplified with minima at φ = 90°, and maxima at φ = 0°. In the case of b1/a1 = 0.5, the SIF is increased by 1% at φ = 90° and by 37.1% at φ = 0°. When the SESC becomes semi-circular, b1/a1 = 1, the amplification effect becomes dramatic: 8% at φ = 90°, and 82.7% at φ = 0°.

In summary, several conclusions can be drawn for this configuration:

- The presence of the SESC has a considerable effect on the SIF of the QCCC. This effect may be either an amplification, or an attenuation;

- The larger the ellipticity of the SESC, the larger its effect on the QCCC;

- In all the above cases, the effect is the smallest at φ = 90°, the free surface, increasing monotonically towards its maximum at φ = 0°, where the two cracks overlap.

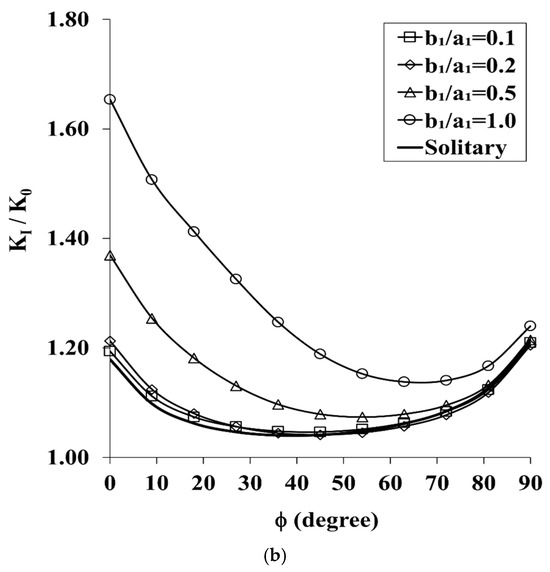

3.2.2. Case II—Horizontally Non-Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

In order to study the influence of the normalized horizontal gap, S/a2, on the effect the SESC has on the QCCC, the crack-configuration presented in case I is resolved with a horizontal dimensionless gap set at S/a2 = 1 while keeping all the rest of the parameters the same. The results for this non-overlapping cracks layout is presented in Figure 4a. The results are dramatically different from those in Figure 3a.

Figure 4.

(a). The Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1).

The SIF distributions for the QCCC due to the different SESC geometries are very much like the results for the solitary QCCC. Thus, to numerically assess these results, the SIF distributions in Figure 4a are renormalized to the values of the solitary crack, KI, and are presented in Figure 4b.

The SIFs along the entire front of the shallow cracks, b1/a1 = 0.1 and 0.2 is reduced by less than 1.5%. The maximum attenuation occurs at φ = 90°, and it monotonically decreases towards φ = 0°. Thus, for these crack configurations the SESC has a complete shielding effect on the QCCC. In the case of b1/a1 = 0.5, only part of the QCCC front is shielded, φ ≥ 63°, with a maximum attenuation in the SIF of 1% at φ = 90°. The rest of the SIFs are amplified by up to 4% at φ = 0°. The SIF along the entire front of the QCCC is amplified in the case of b1/a1 = 1, with 1.1% increase at φ = 90°, and 4.2% at φ = 0°.

To sum up, when the two cracks are apart, and the normalized horizontal gap is large, e.g., S/a2 = 1, the effect of the SESC on the QCCC is considerably reduced as compared to the case of overlapping cracks, though it has the same characteristic trends. As in case I, the larger the ellipticity of the SESC, the larger its effect on the QCCC; and the amplification/attenuation effects are the smallest at φ = 90°, increasing monotonically as φ decreases with a maximum KI at φ = 0°.

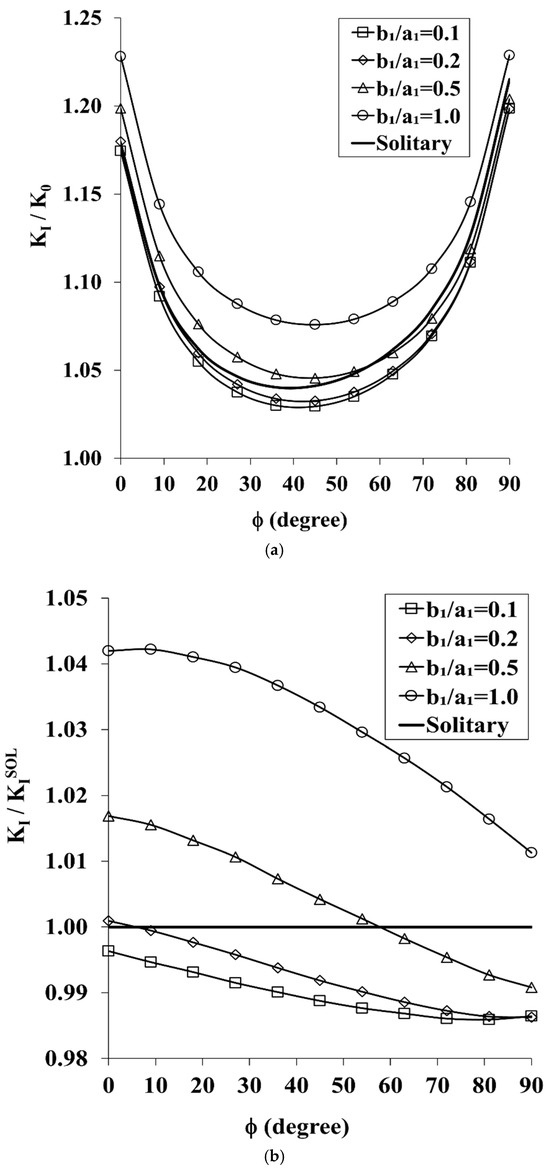

3.2.3. Case III—Horizontally Overlapping but Vertically Distant Cracks

In order to assess the effect of the normalized vertical gap, H/a2, on the influence the SESC has on the CCCC, the crack-configuration presented in case I is assessed when H/a2 = 1.2 while keeping all the rest of the parameters the same. Thus, in this case the two cracks horizontally overlap as in case I, but are farther apart vertically. The results for crack layout are presented in Figure 5a.

Figure 5.

(a). The Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 1.2, and S/a2 = −0.5). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = a1 = 15 mm, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 1.2, and S/a2 = −0.5).

The results are very different from those of the previous two cases presented in Figure 3a and Figure 4a. The entire SIF distribution along the front of the QCCC is reduced by the presence of the shallow semi-elliptical surface cracks, b1/a1 = 0.1 and 0.2. In the presence of deeper SESCs, b1/a1 = 0.5 and 1, the SIFs along part of the QCCC front, φ ≥ 63°, are amplified, while along the rest of its front φ ≤ 63°, the SIFs are reduced. Unlike in the previous two cases, where the SIF curves do not intersect each other, in the present case they crossover around φ ≈ 50°, and the normalized SIF of the QCCC is practically the same for all the SESC ellipticities greater than 0.5. For the two higher b1/a1, values the relative minima of the curves are sharper than for the lower two b1/a1 values.

In Figure 5b the values of the SIFs of Figure 5a are renormalized to the values of the solitary crack, KI/, enabling a quantitative assessment of the above effects. In general, it is clear that for this overlapping but vertically distant crack configuration, the higher the ellipticity of the SESC, the higher its impact on the QCCC both in amplifying and in reducing its SIF.

The two shallow SESC have practically no influence on the QCCC, and the SIF along its front almost equals that of the solitary crack. In the case of b1/a1 = 0.5, the SIF is amplified by up to 1% at φ = 90° while being reduced by up to 8.7% at φ = 0°. In the case of b1/a1 = 1, the SIF distribution has a similar pattern as in the case of b1/a1 = 0.5, but with a considerably higher influence of the SESC, i.e., the SIF is amplified by up to 6% at φ = 90° while being reduced by up to 18.3% at φ = 0°. For the two higher b1/a1 values, the slope of the curves is much higher than for the lower two b1/a1 values prior to the crossover point at around φ ≈ 50°, and the order of the curves reverse beyond the crossover point.

Several interim conclusions can be drawn so far from cases I, II, and III:

- The presence of the SESC can have opposite effects on the QCCC simultaneously: On the one hand, it amplifies the SIF along part of the QCCC front, and on the other hand, it reduces the SIF on the rest of its front;

- The ellipticity of the SESC plays a major role in its effect on the QCCC. In general, the higher the ellipticity, the higher the effect, both in amplifying and in reducing the SIF along the QCCC front;

- Increasing the horizontal or vertical gaps results in a weaker effect of the SESC on the QCCC.

3.3. The Effect of a Longer Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack on the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack

In order to evaluate the effect of the same QCCC (a2 = 15 mm) on a longer SESC, the previous case I and case II of Section 3.2 are determined for a longer SESC of a1 = 30 mm (a1/a2 = 2), while all the other parameters, viz., the SESC four ellipticities, b1/a1 = 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0, as well as the normalized separation gaps, H/a2 = 0.4 and S/a2 = −0.5 and 1.0 are kept the same.

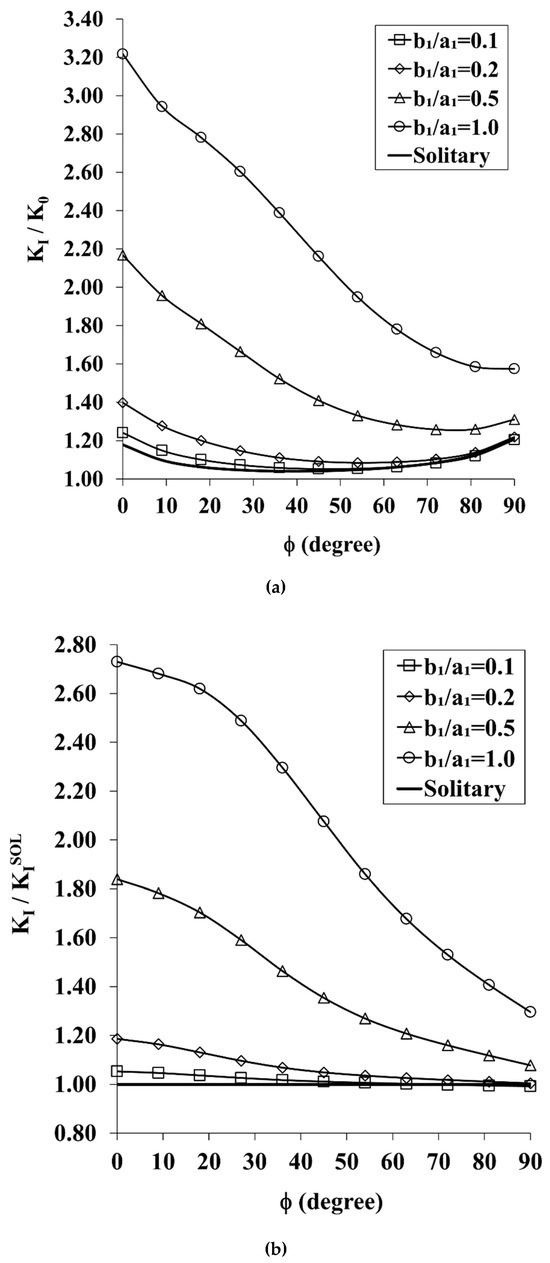

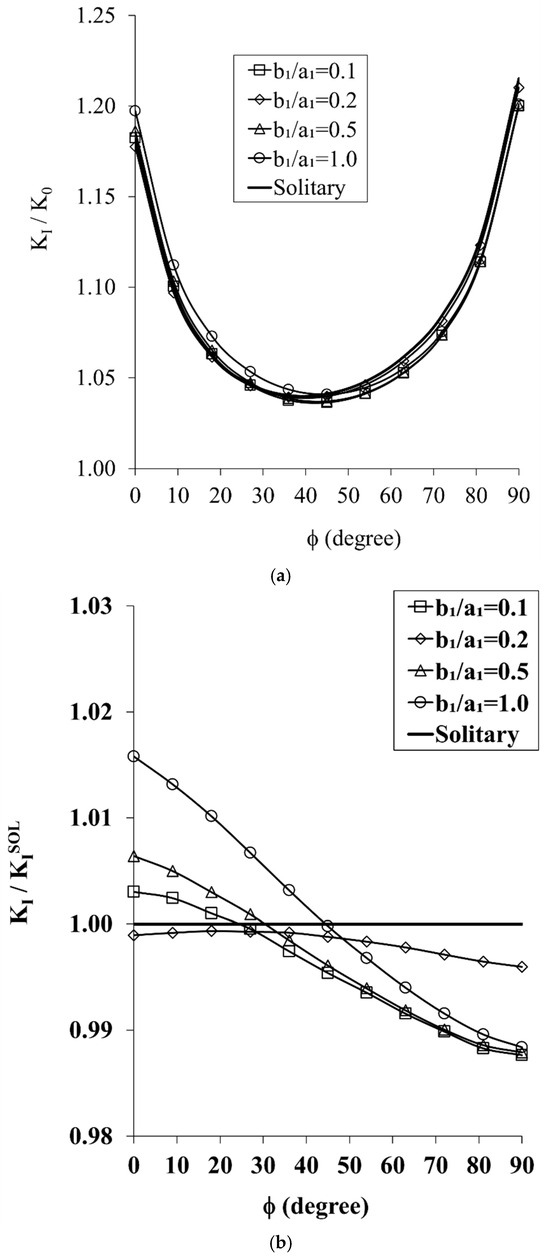

3.3.1. Case IV—Larger SESC, Horizontally Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

The data of the geometrical configuration of case I with a larger SESC, a1/a2 = 2, while keeping all the other parameters the same, is provided and discussed. The distribution of the SIF along the front of the QCCC under in-plane bending, as affected by the presence of a larger SESC, is presented in Figure 6a. Comparing Figure 6a to Figure 3a, shows that both cases have a similar pattern, but differ considerably in magnitude.

Figure 6.

(a). The Effect of Larger Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a1 = 30 mm, a1/a2 = 2, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Larger Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a2 = 30 mm, a1/a2 = 2, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5).

As a rule, the effect of increasing the size of the semi-elliptical surface crack enhances the SIF for the QCCC with a minimal effect at φ = 90°, and a maximal effect seen at φ = 0°. Furthermore, the size effect depends on the SESC’s ellipticity; the larger b1/a1, the larger the effect.

To assess these effects, the distributions of the SIF along the front of the QCCC is re-normalized to the values of the solitary crack, KI, and presented in Figure 6b. In the case of the shallowest, b1/a1 = 0.1, the size of the SESC has practically no effect, as the solution for the smaller (a1 = 15 mm) and the larger (a1 = 30 mm) SESC (compare Figure 3b to Figure 6b) are almost identical, within less than 2%. As ellipticity increases, b1/a1 = 0.2, the SIF distribution for the larger SESC is somewhat higher than that for the smaller SESC by about 1.3% at φ = 90°, and it increases monotonically up to 8.8% at φ = 0°.

As the ellipticity further increases, the effect of the larger SESC becomes more noticeable. In the case of b1/a1 = 0.5, the SIF is increased by 6.6% at φ = 90° and 34% at φ = 0°. The maximum effect of the presence of the larger SESC occurs when it becomes semi-circular, b1/a1 = 1, i.e., at φ = 90° the SIF is increased by 20%, and it increases by 49.3% at φ = 0°.

3.3.2. Case V—Larger SESC, Horizontally Non-Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

Case V is a counterpart of case II, but for a larger SESC. The problem is solved while keeping all the geometrical parameters as in case II, except for the semi-elliptical crack size which is doubled, i.e., a1/a2 = 2. The distribution of the SIF along the front of the QCCC under in-plane bending, as affected by the presence of a larger SESC, is presented in Figure 7a. Comparing Figure 7a to Figure 4a shows that both cases have similar patterns but differ in magnitude. The effect of the larger SESC (Figure 7a) is somewhat stronger than that of the smaller SESC (Figure 4a). The largest effect occurs for the semi-circular surface crack, b2/a1 = 1, at φ = 0°.

Figure 7.

(a). The Effect of Larger Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a2 = 30 mm, a1/a2 = 2, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Larger Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a2 = 30 mm, a1/a2 = 2, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1).

The results of Figure 7a are renormalized to the values of the solitary crack, KI, and are presented in Figure 7b. In general, the results of case V deviate only moderately from the results for the solitary crack. The SIFs for the shallow cracks, b1/a1 = 0.1–0.2, are practically the same as for the solitary counterparts, deviating by less than 1%, which means that SESCs of small ellipticity have no influence on the QCCC in this case. The presence of a SESC of larger ellipticity, b1/a1 = 0.5, creates a negligible shielding of about 1% on a small portion of the QCCC front, viz., φ ≥ 72°. Along the rest of the QCCC front, a gradual amplification of the SIF occurs from less than 1% at φ = 63°, up to 4.6% at φ = 0°. The entire distribution along the front of the QCCC is amplified in the case of b1/a1 = 1, from less than 1% at φ = 90° to 12.1% at φ = 0°.

For the sake of brevity, in the case of a longer SESC (a1 = 30 mm, a2 = 15 mm), the results for horizontally overlapping but vertically distant cracks (S/a2 = −0.5, H/a2 = 1.2), are not presented herein, as this case shows very little crack interaction. Thus, the cracks can be treated as separate cracks.

3.4. The Effect of a Shorter Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack on the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack

To further evaluate the effect of the same QCCC (a2 = 15 mm) on a different size of the SESC cases I and II are solved once again by changing the SESC size to a shorter one, a1 = 10 mm (a1/a2 = 2/3). All the rest of the corresponding parameters are kept intact, i.e., the same four ellipticities of the SESC are used, b1/a1 = 0.1 to 1.0, as well as the same normalized gaps H/a2 and S/a2.

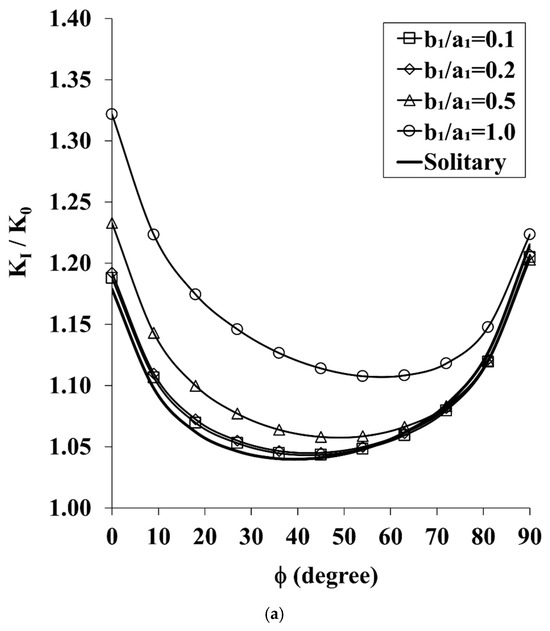

3.4.1. Case VI—Smaller SESC, Horizontally Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

Based on the previous results, it can be assumed that a smaller SESC size would result in a smaller effect on the QCCC. Figure 8a, a plot of KI/K0 is made to test this hypothesis and is compared to Figure 3a. The overall pattern of Figure 8a is similar to that of Figure 3a. However, the effect of the smaller SESC on the normalized SIF of QCCC is reduced when compared to case I. The reduced effect of the smaller crack increases as crack ellipticity increases, and as the parametric angle varies from φ = 90° to φ = 0° along the QCCC front.

Figure 8.

(a). The Effect of Smaller Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a1 = 10 mm, a1/a2 = 2/3, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Smaller Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a1 = 10 mm, a1/a2 = 2/3, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = −0.5).

Figure 8b represents the SIF amplification/attenuation effect of the smaller SESC on the QCCC relative to the solitary crack. By comparing Figure 8b to Figure 3b, it is clear that the reduction in the SESC’s size has hardly any effect as long as its ellipticity is small, b1/a1 ≤ 0.2. When its ellipticity increases to b1/a1 = 0.5 the smaller SESC has no effect on the QCCC at φ = 90°, but increases its SIF by 16.1% at φ = 0°. As the smaller SESC becomes semi-circular, its effect is much smaller than in case I: 2% at φ = 90° and up to 40.3% at φ = 0°.

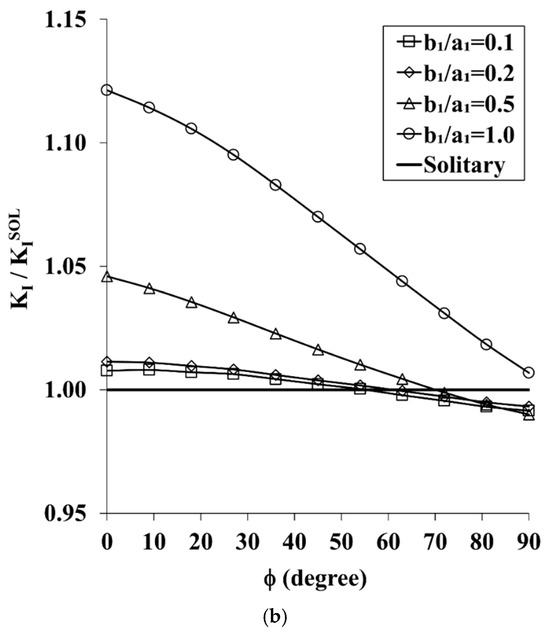

3.4.2. Case VI—Shorter SESC, Horizontally Non-Overlapping & Vertically Close Cracks

The effect of a non-overlapping (S/a2 = 1) shorter SESC, a1 = 10 mm, on the SIF of the QCCC is presented in Figure 9a. This case is identical to case VI except for the larger horizontal gap of S/a2 = 1.

Figure 9.

(a). The Effect of Shorter Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack on the Distribution of the SIF along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a1 = 10 mm, a1/a2 = 2/3, b1/a1 = 0.1–1.0, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1). (b). The Amplification/Attenuation Effect of Shorter Semi-Elliptical Surface Cracks on the SIF Distribution along the Front of the Quarter-Circle Corner Crack Under In-Plane Bending (a2 = 15 mm, a1 = 10 mm, a1/a2 = 2/3, b1/a1 = 0.1–1, H/a2 = 0.4, and S/a2 = 1).

Once the SESC is moved horizontally away from the QCCC, S/a2 = 1.0, as in cases II and V, the SIF distribution along the SESC front is hardly affected by the adjacent QCCC, irrespective of the SESC ellipticity. Practically, the two cracks do not interact, and thus can be handled separately.

Figure 9b depicts the SIFs along the front of the shorter crack normalized to their solitary counterparts KI/. In this case, the SESC produces a minimal amplification/attenuation effect on the QCCC. Semi-elliptical surface cracks with ellipticities b1/a1 ≤ 0.5 induce a slight amplification of much less than 1% on the QCCC, limited to about a third of its front, φ ≈ 0°−30°. The rest of the QCCC front is attenuated up to about 1%, at φ = 90°. In the case of the semi-circular surface crack, b1/a1 = 1.0, about half the QCCC is amplified, from φ = 0–45°, up to 1.6% at φ = 90°, and the other half is attenuated up to about 1% at φ = 90°.

Again, for the sake of conciseness, in the case of a shorter SESC (a1 = 10 mm, a2 = 15 mm), the results for horizontally overlapping and vertically distant cracks (S/a2 = −0.5, H/a2 = 1.2) are not presented herein, as in this case, there is practically no interaction between the two cracks, and they can be treated as separate cracks.

4. Concluding Remarks

Using 3D finite element models, the effect of a semi-elliptic surface crack on the SIF distribution along the front of a quarter-circle corner crack in a semi-infinite large solid under in-plane bending is investigated for various crack configurations.

The results demonstrate that the SIFs along the crack front of the quarter-circle corner can be significantly affected by the presence of the semi-elliptic surface crack. Furthermore, this effect can simultaneously amplify the SIFs along part of the QCCC front, and reduce them along the rest of the front.

The magnitude of the effect of the SESC on a given QCCC depends on several geometrical parameters: the cracks’ relative size, a1/a2; the ellipticity of the SESC, b1/a1; and the normalized horizontal and vertical gaps between the two cracks, S/a2, and H/a2, respectively.

The larger the ellipticity of the SESC, and the smaller the horizontal or vertical gaps are, the larger the effect on the QCCC. In the case of very shallow SESC cracks, b1/a1 = 0.1, the QCCC is practically unaffected for all crack configurations that have been investigated. Thus, in such a situation, the two cracks can be considered separately in FFS analysis.

The most affected point on the QCCC front, for most geometrical configurations, is at φ = 0°, the closest point to the SESC. The larger the ellipticity of the SESC, the larger the effect on the SIF at φ = 0°. This effect can produce an increase in the SIF of up to 173% in case IV. Thus, for FFS analysis, the SIF at φ = 0° would be the critical value for the QCCC. Case III is the only case in which the maximum amplification along the QCCC front occurs at φ = 90°. This results from the fact the SESC is twice as large as the QCCC, creating a considerable shielding effect along most of the QCCC front with a maximum attenuation of the SIF of 18.3% at φ = 0°.

The results for the present problem are very similar to those in [20,21], where the mutual effects of a QCCC and a SESC in a semi-infinite solid under uniform tension have been studied. The results in the present case are somewhat smaller because of the varying remote tensile stress that creates the in-plane bending moment.

In light of the similarities between these two analyses, it is reasonable to come to the same conclusions regarding the FFS criteria. The present results appear to meet the criteria for some of the FFS rules, while not for others, as well as to be conservative according to some of the formulae and non-conservative according to the others. Therefore, in view of the fact that the existing alignment rules used to evaluate the “fitness for service” do not agree and can lead to distinctly opposite results, it is necessary to perform a full 3D analysis in order to quantify the “real” effect of neighbouring cracks. Further research is needed in order to map the complete range of all the relevant parameters, i.e., S, H, a1, a1/a2, a2, and b1/a1, for which significant interaction between these two adjacent cracks occurs, and a 3D analysis is required to evaluate the magnitude and characteristic of this interaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.; Software, Q.M.; Formal analysis, M.P.; Investigation, Q.M. and C.L.; Writing—original draft, M.P.; Writing—review and editing, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The second author (QM) would like to express his deep gratitude to Walla Walla University for its support of this research work through its Faculty Development Grant.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflict of interests with this work. The engineering simulation information within this paper is provided for general informational and educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional advice. Also, we do not provide any kind of engineering simulation advice. Accordingly, before taking any actions based upon such information, the authors encourage the reader to consult with appropriate professionals. The use of or reliance on any information contained in this paper is solely at the reader’s risk.

Nomenclature

| a1 | half semi-elliptical surface crack length |

| a2 | corner crack length |

| b1 | semi-elliptical surface crack depth |

| E | Young’s modulus |

| H | vertical gap between the cracks |

| KI | mode I SIF |

| mode I SIF for the solitary crack | |

| K0 | Normalizing SIF |

| S | horizontal gap between the cracks |

| Greek Symbols | |

| υ | Poisson’s ratio |

| σ∞ | the maximum bending stress (see Figure 1a) |

| φ | parametric angle (see Figure 1a,b) |

| Acronyms | |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| DOF | Degrees of Freedom |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FE | Finite Element |

| FFS | Fitness-for-Service |

| QCCC | Quarter-Circle Corner Crack |

| SESC | Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack |

| SIF | Stress Intensity Factor |

References

- API 579-1/ASME FFS-1; Fitness-For-Service. The American Petroleum Institute and The American Society of Mechanical Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Okamura, Y.; Sakashita, A.; Fukuda, T.; Yamashita, H.; Futami, T. Latest SCC Issues of Core Shroud and Recirculation Piping in Japanese BWRs. In Proceedings of the Transactions of 17th International Conference on Structural Mechanics in Reactor Technology (SMiRT 17), Prague, Czech Republic, 17–22 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaya, M.; Haruna, T. Crack Initiation Model for Type 304 Stainless Steel in High Temperature Water. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 2442–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASME. Section XI: Rules for Inservice Inspection of Nuclear Power Plant Components. In The ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, 2025 ed.; ASME International: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- BS 7910:2019; Guide to Methods for Assessing the Acceptability of Flaws in Metallic Structures. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2019.

- Gutiérrez-Solana, F.; Cicero, S. FITNET FFS procedure: A Unified European Procedure for Structural Integrity Assessment. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2009, 16, 559–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSME S NA1-2008; Rules on Fitness-for-Service for Nuclear Power Plant. Japan Society of Mechanical Engineers: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. (In Japanese)

- Kamaya, M. Growth Evaluation of Multiple Interacting Surface Cracks. Part I: Experiments and Simulation of Coalesced Crack. Eng. Fracture Mech. 2008, 75, 1350–1366. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K.; Saito, K.; Miyazaki, K. Alignment Rule for Non-Aligned Flaws for Fitness-for Service Evaluations Based on LEFM. ASME J. Press. Vessel Technol. 2009, 131, 041403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Saito, K. Behavior of Plastic Collapse Moments for Pipes with two Non-Aligned Flaws, ASME PVP2010-25199. In Proceedings of the 2010 ASME PVP Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 18–22 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Saito, K. Plastic Collapse Loads for Flat Solids with Dissimilar Non-Aligned Through-Wall Cracks, ASME PVP2011-57841. In Proceedings of the 2011 ASME PVP Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–21 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Saito, K. Effect of Flaw Dimensions on Ductile Fracture Behavior of Non-Aligned Multiple Flaws in a Solid, ASME PVP2011-57559. In Proceedings of the 2011 ASME PVP Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–21 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suga, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Kawasaki, S.; Arai, Y. Study on the Interaction of Multiple Flaws in Ductile Fracture Process, ASME PVP2011-57188. In Proceedings of the 2011 ASME PVP Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–21 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Suga, K.; Miyazaki, K.; Senda, R.; Kikuchi, M. Ductile Fracture Simulation of Multiple Surface Flaws, ASME PVP2011-57147. In Proceedings of the 2011 ASME PVP Conference, Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–21 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, M. Study on Multiple Surface Crack Growth and Coalescence Behaviors. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2016, 3, 1623–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio, J.; González, B.; Matos, J.C.; Mulas, Ó. Stress Intensity Factors for Embedded Surface and Corner Cracks in Finite-Thickness Plates Subjected to Tensile Loading. Materials 2021, 14, 2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, T.; Mei Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, W.; Wang, W.; Meng, X.; Ouyang, X. Influence of Interaction Among Multiple Cracks on Crack Propagation in Nozzle Corner of Reactor Pressure Vessel. Ann. Nucl. Ener 2023, 194, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrian, F.; Cornetti, P.; Sapora, A.; Hossein Talebi, A.; Ayatollahi, M.R. Crack Tip Shielding and Size Effect Related to Parallel Edge Cracks Under Uniaxial Tensile Loading. Int. J. Fracture 2024, 245, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.W.; Li, D.M.; Zhong, Y.F.; Liu, Y.K.; Shao, Y.N. Review of Experimental, Theoretical and Numerical Advances in Multi-Crack Fracture Mechanics. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, M.; Ma, Q.; Levy, C. The Influence of a Non-Aligned Semi Elliptical Surface Crack on a Quarter-Circle Corner Crack in an Infinitely Large Solid Under Uniaxial Tension. In Proceedings of the 2016 ASME PVP Conference, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–21 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, C.; Ma, Q.; Perl, M. The Effect of a Quarter-Circle Corner Crack on the Distribution of the SIF Along the Front of a Non-Aligned Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack in an Infinitely Large Solid under Uniaxial Tension. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition, Tampa, FL, USA, 3–9 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, C.; Ma, Q.; Perl, M. The Influence of a non-Aligned Semi-Elliptical Embedded Crack on the Stress Intensity Factor Distribution Along the Front of a Quarter-Circle Corner Crack in a Semi-Infinite Solid Under Pure Bending. In Proceedings of the 2020 ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress & Exposition, Portland, OR, USA, 15–18 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Perl, M.; Levy, C. The Change in the SIF of an Internal Semi-Elliptical Surface Crack Due to the Presence of an Adjacent Nonaligned Corner Quarter-Circle Crack in a Semi-Infinite Body Under Remote Bending. In Proceedings of the 2023 ASME PVP Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–21 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson Analysis System, Inc. ANSYS 12 User Manual; SAS IP Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, I.S.; Newman, J.C., Jr. Stress Intensity Factors for Internal Surface Cracks in Cylindrical Pressure Vessel. ASME J. Press. Vessel Technol. 1980, 102, 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon, I.N. The distribution of stress in the neighbourhood of a crack in an elastic solid. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1946, 187, 229–260. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, H.; Paris, P.; Irwin, G. The Stress Analysis of Crack Handbook, 3rd ed.; ASME Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; p. 412, Part IV. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, R.O. Mechanisms of fatigue crack propagation in metals, ceramics and composites: Role of crack tip shielding. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1988, 103, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.W. Crack Tip Shielding by Micro Cracking in Brittle Solids. Acta Metall. 1987, 35, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).