Featured Application

This study provides guidance for the ergonomic design of seat pans that support correct posture and reduce fatigue during prolonged sitting.

Abstract

This study evaluates the ergonomic benefits of a novel chair featuring a four-segment flexible seat pan designed to support correct sitting posture. Motion capture and electromyography tools are used to quantitatively assess the impact of different chair designs on pelvic and lumbar angles and muscle usage through two ergonomic experiments (short- and long-term). In the short-term experiment (30 participants), the proposed chair demonstrated significant improvements in maintaining the spine’s S-shape, with hip and lumbar angle enhancements of up to 15.3° compared to a conventional chair. The long-term experiment (20 participants) revealed that the proposed chair led to a more favourable muscle fatigue profile during prolonged sitting, with a 47% decrease at lower frequencies (0 to 20 Hz) and a 34% increase at higher frequencies (60 to 80 Hz) compared to the conventional chair, indicating reduced muscle fatigue. These results suggest that the proposed chair can significantly improve posture and reduce fatigue in settings that require prolonged sitting.

1. Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders in the lumbar region are becoming more common among individuals who spend prolonged periods sitting, whether for work, driving, or studying [1,2,3,4,5]. This long-term maintenance of incorrect sitting postures negatively affects the spine and pelvis. While seated, the ischium and soft tissues of the buttocks, along with the muscles in the neck, back, and pelvic areas, are used to support the upper body. Correct sitting posture involves maintaining the spine’s natural S-shaped curve, with the lumbar region slightly arched forward (lumbar lordosis), the pelvis rotated anteriorly, and the body weight evenly distributed across the ischial tuberosities. Additionally, the feet should be flat on the floor, the thighs parallel to the ground, and the knees positioned at or slightly below hip level, while the shoulders are relaxed, and the head is aligned over the shoulders [2,6,7,8]. Prolonged (say, more than 1 h) incorrect posture leads to muscle fatigue and makes maintaining a correct sitting posture difficult over time, which can lead to isometric muscle contractions that cause muscle fatigue and lower back pain [5,9,10,11]. In particular, improper sitting postures may accelerate the development of chronic musculoskeletal issues such as lumbar disc herniation, turtleneck syndrome, and myofascial pain syndrome in the neck, back, and pelvic areas [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Beyond spinal and pelvic issues, extended periods of sitting can cause discomfort (including pain, muscle cramps, and numbness) and increase body fatigue. This can adversely affect nutrient supply and cognitive functions, such as concentration and work efficiency, and potentially contribute to chronic diseases and other detrimental health conditions [10,19,21,22,23,24,25]. Thus, the importance of chair designs that accommodate the body’s biomechanical characteristics to promote good posture has been emphasized in previous research [26,27,28,29,30,31].

As more people spend extended periods sitting in chairs owing to their contemporary lifestyles, research has increasingly emphasized the importance of maintaining the correct sitting posture for the health and well-being of chair users. Correct posture, characterized by a lumbar lordotic curve (forward rotation of the pelvis), ensures an even distribution of contact pressure across the seat pan and effectively supports body weight through the sitting bones (ischial tuberosities). Adopting a correct posture effectively utilizes the muscles in the abdomen and back (e.g., multifidus and internal oblique) to support the alignment of the ears, shoulders, and hips in a straight vertical line to maintain spinal health [2,3,15,32,33]. The ideal correct posture exhibits an S-shaped spinal curve, with an inward curve of the neck, outward curve of the mid-back, and inward curve of the lower back [2,34]. Achieving this posture requires minimizing tension in the neck and shoulders and avoiding forward neck protrusion and kyphosis [35,36,37]. Recent studies have highlighted the necessity of periodic posture adjustments due to the challenges of sustaining a static correct posture over extended periods [2,6,38].

Numerous studies have explored ergonomic chair features that promote proper posture, focusing mainly on backrests and, more recently, seat pans. First, research has examined the role of the seatback in lumbar support, aiming to maintain the spine’s S-shape, especially considering the risk of intervertebral disc degeneration from prolonged improper sitting. This has led to the development of chairs designed to provide adequate back support, maintaining the spine’s S-shape, thereby improving comfort and reducing the risk of disc damage during prolonged sitting [1,2,3,21,34]. Park et al. [34] introduced a seatback divided into three parts to increase contact area and lessen back pressure, although they noted the underuse of the seatback owing to frequent shifting and the tendency to lean forward over time [39]. Second, regarding the seat pan design, Azghani et al. [40] investigated the role of seat pan depth in promoting circulation in the legs and reducing pressure in the thigh. Zemp et al. [41] pointed out that traditional flat seat pan designs might limit the movement of muscles and soft tissues between the ischium and chair, potentially leading to ischemic changes. To address this issue, Choi and Sohn [21] and Denes et al. [42] introduced flexible seat designs that supported dynamic movements of the pelvis. Moreover, Kim et al. [32] examined the effectiveness of a three-segmented flexible seat pan in preventing backward pelvic rotation and preserving the lumbar curve through several methods, including electromyography (EMG), motion analysis, and surveys. In summary, while earlier studies focused on backrest configurations to preserve the spine’s S-shape, more recent studies have explored seat pan designs that promote forward pelvic rotation and enable dynamic sitting. This highlights the need for further detailed studies.

Despite extensive research on ergonomic chair design, most existing studies have primarily emphasized the role of backrests in supporting posture and reducing musculoskeletal strain during seated work. However, comparatively little attention has been paid to the ergonomic implications of seat pan design, especially in dynamic, unsupported sitting conditions. Furthermore, while several studies have investigated seat cushions or tilting mechanisms individually, few have combined real-time motion analysis and muscle activity monitoring to isolate the effects of seat pan contour and flexibility on postural control. This study addresses this gap by evaluating muscle usage and joint kinematics during short-term and long-term sitting, focusing specifically on seat pan design. By doing so, the research offers new insight into the design of chairs that promote active sitting without relying on backrest support, thus contributing to the ongoing discourse on preventive ergonomic strategies for sedentary populations.

This study aimed to empirically analyze the extent to which a chair with a four-segment flexible seat maintains a correct sitting posture. Through ergonomic experiments, motion capture and EMG measurement equipment were used to analyze the angles of the pelvic area and the use of force in the back/abdominal area in a seated posture on three different chairs. The design characteristics of ergonomic chairs that enabled people to maintain a correct sitting posture were examined. This paper first presents the ergonomic design of a chair with a flexible seat pan (Section 2), followed by experimental methods and usability evaluations comparing it with a conventional chair (Section 3); it then details the results (Section 4), interprets the findings in the context of ergonomic benefits (Section 5), and concludes with key insights and implications for future research (Section 6).

2. Ergonomic Design of a Chair with a Flexible Seat Pan

This study identified the biomechanical characteristics of a correct sitting posture by referring to existing studies, analyzed chair design elements that could help individuals assume a correct sitting posture, and proposed a design featuring a four-segment seat with flexibility. First, because individuals have different body types and standards of sitting comfort, it is difficult to define a generally correct sitting posture [6,39,43,44]. Therefore, it needs to be able to accommodate various body types and sitting styles, providing an optimized, correct sitting posture for each individual [45,46]. Second, a dynamic sitting approach has been proposed such that, as prolonged sitting in one is not beneficial, there is continuous posture adjustment on the chair to promote micro-movements of the spine, thereby reducing muscle tension, distributing pressure on the spine, and decreasing back pain or discomfort [45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. To enable dynamic sitting, flexibility can be applied to the seat pan, facilitating the movement of the pelvis in a seated posture and alleviating pressure on the back. Finally, a balanced and good posture that minimizes the overall load on the body while sitting is achieved when the pelvis rotates forward, maintaining the spine in an S-shape, and the ears, shoulders, and hips are vertically aligned [2,3,15,32,33]. However, when focusing on other tasks, maintaining a correct posture becomes difficult, making it easy to adopt an incorrect one [34,39,52]. A slouched posture causes the pelvis to rotate backward, flattens the curvature at the lower part of the spine, and drops the neck forward, which disrupts the overall sitting balance, increases the load on the lumbar region, and intensifies the compressive force on the discs [3,13,14,15,32,46,47,53,54]. Therefore, a chair design that naturally assists users in maintaining a correct sitting posture is required.

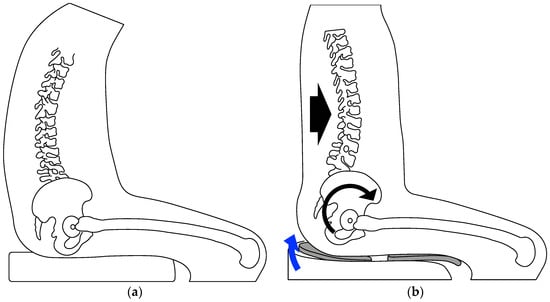

A design concept with a four-segment flexible seat pan is proposed, allowing people of various body types to naturally rotate their pelvis forward and form an S-shape with their spine to maintain a correct posture on a chair (Figure 1). The four-seat pan segments are arranged with two on either side under the buttocks and two on either side under the thighs. An under-chair spring mechanism enables rotation up to 30° in all directions and returns to the original position. Thus, this design can support micro-movements of the spine and pelvis while sitting for extended periods. Based on the proposed design concept, several prototypes were created and tested, leading to the commercialization of the product.

Figure 1.

Comparison between conventional and flexible seat pan designs: (a) conventional flat seat pan limiting pelvic rotation and flattening lumbar curvature; (b) flexible seat pan promoting forward pelvic tilt and natural S-shaped spinal alignment. The black arrows indicate the facilitation of lumbar curvature, while the blue arrow shows the rotation of the flexible seat pan that induces anterior pelvic tilt.

3. Usability Evaluations

This study conducted two experiments: one involved sitting on three different chairs multiple times (short-term evaluation) to analyze the ease of assuming a correct sitting posture in terms of joint angles and muscle force usage, while the other (long-term evaluation) analyzed the fatigue of back muscles while sitting on a chair for one hour. This study was approved by the institutional review board of a local ethics committee (Handong Global University, 2023-HGUR004).

3.1. Experiment I: Short-Term Evaluation

3.1.1. Participants

Participants in the experiment were 30 university students (age: 24.7 ± 2.2), with 20 males and 10 females, who could maintain a correct posture without any difficulty or back pain. Mean body size was a height of 171.8 ± 5.3 cm (162.0 to 180.2 cm) and a weight of 70.1 ± 12.4 kg (52.0 to 103.2 kg).

3.1.2. Apparatus

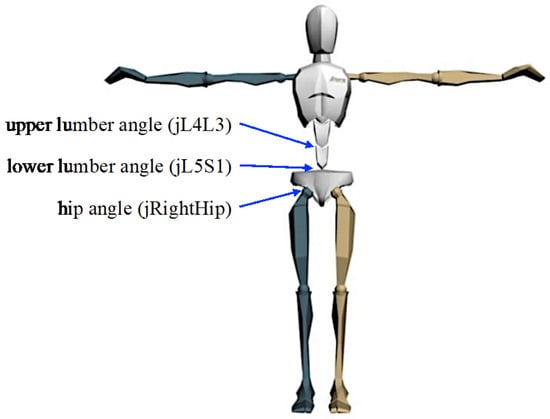

This study compared two chairs with different types of seat pans using motion and EMG analysis equipment. Xsens (Enschede, The Netherlands) motion capture equipment was used to analyze the joint angles of the pelvic area in a seated posture. Xsens uses 17 sensors attached to the human body to define 23 body segments, and utilizes this to measure 22 human joint angles [55]. The joint angle is measured as the three-dimensional angle between two connected segments. Among the 17 sensors, those relevant to this study (used to the angles of the pelvic area and their attachment sites) are located on the pelvis (around the L5 location at the height of the anterior superior iliac spine), sternum (middle of the sternal bone of the chest), and right/left upper legs (middle of the lateral thigh). Among the 22 joint angles provided by Xsens’s human model, this study used the upper lumbar angle (Xsens code: jL4L3), lower lumbar angle (Xsens code: jL5S1), and hip angle (Xsens code: jRightHip), as illustrated in Figure 2. Before measuring each participant’s movements, the sensors were calibrated using the Xsens MVN software. To measure muscle strength in a seated posture, the TeleMyo Clinical DTS, surface EMG (sEMG) measurement equipment from Noraxon (Scottsdale, AZ, USA), was utilized. By referring to the EMG guidelines, sensors were attached to the human body surface on the left and right erector spinae and rectus abdominis muscles. After attaching the sensors, calibration was performed using the Noraxon myoRESEARCH software, and then maximum voluntary contraction (MVC) was measured, using the guidelines to assess the two muscles.

Figure 2.

Joint angles used in this study, as provided by the Xsens skeletal model (illustrated).

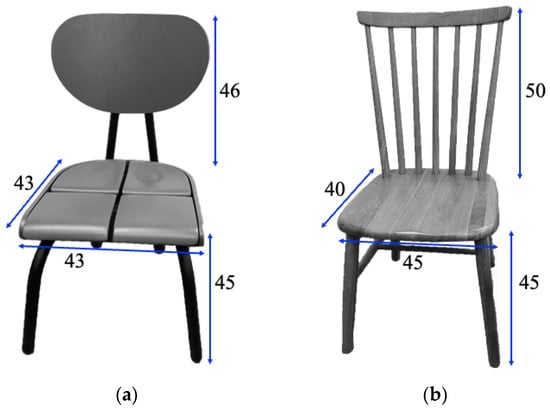

This study selected two chairs with different seat pan designs (Chair A: the proposed chair with a four-segment flexible seat pan; Chair B: a conventional table chair with a flat seat pan) to analyze the characteristics of sitting posture according to the design features of the seat. Chair A has a seat divided into four sections, allowing for flexible movement, which makes it easier for people with different body shapes and anthropometric characteristics to adopt a correct sitting posture. This design was biomechanically intended to support the natural movement of the pelvis and accommodate soft tissue dynamics around the ischial tuberosities. By allowing independent motion of each segment, the seat pan was expected to facilitate forward pelvic tilt and reduce localized pressure accumulation, which in turn promotes upright sitting posture and spinal alignment. The other chair (Chair B) has a flat seat pan. Although the backrest designs differ, this study focused on the seat pan and did not examine the effects of the backrest design. The backrests of the chairs used in this study provide basic support and have standard physical characteristics, and the design dimensions of the two chairs are similar. While these chairs are not typical office task chairs, they are versatile and can be widely used in home or personal workspace settings. We assume that the differing backrest designs will not significantly impact the seat pan experiment because the primary focus is on how the seat pan influences posture and muscle usage, particularly in conditions where the backrest is minimally or not relied upon. The backrests were designed to serve as basic support features rather than active components, thus minimizing their influence on the measured outcomes. To further isolate the seat pan’s effects, the chairs used in the experiment were selected without cushions, armrests, or height adjustment features, and both were made of wood to ensure consistency in material properties [4,14,26,56,57]. Information regarding the shapes and sizes of the chairs is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Chairs compared in this study: (a) the proposed chair with a four-segment flexible seat pan (Chair A); (b) a conventional table chair with a flat seat pan (Chair B) (unit: cm).

3.1.3. Experiment Design

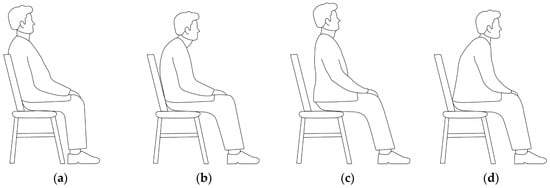

The experiment was conducted using a five-step procedure (S1: introduction; S2: attaching sensors to the body; S3: practice; S4: main experiment; and S5: debriefing). First, the purpose and process of the experiment were explained to participants and informed consent was obtained. Second, sEMG sensors were attached to the participants’ left and right rectus abdominis muscles and erector spinae muscles; 17 Xsens motion measurement sensors were attached to the designated areas on the body, and the MVC for those muscles was measured. Third, participants attempted several times to assume four sitting postures while seated on the chairs for practice (Figure 4): (a) correct posture leaning against the backrest (correct leaning), (b) improper posture leaning against the backrest (improper leaning), (c) correct posture without leaning against the backrest (correct non-leaning), and (d) improper posture without leaning against the backrest (improper non-leaning). Fourth, participants assumed four different sitting postures on the two types of chairs and maintained each posture steadily for 5 s. Each trial was repeated three times, resulting in a total of 24 trials (2 chairs × 4 postures × 3 repetitions). Finally, participants responded to the survey on the subjective usability scores of each chair, and their participation was compensated.

Figure 4.

Four postures compared through the experiment (illustrated): (a) correct leaning posture; (b) improper leaning posture; (c) correct non-leaning posture; (d) improper non-leaning posture.

3.1.4. Analysis Method

Experiment I analyzed the pelvic rotation angles, the use of force in the back and abdomen, and subjective satisfaction across four sitting postures on two types of chairs. Pelvic rotation was analyzed through flexion/extension angles for three angles (upper lumbar angle, lower lumbar angle, and hip angle) provided by the Xsens equipment, as described in Section 3.1.2. The amount of muscle used in the back and abdomen was analyzed as %MVC based on EMG measurements of the left and right erector spinae and rectus abdominis muscles. Notably, %MVC makes it possible to fairly compare muscle effort between people by showing it as a percentage of their strongest effort, even if their EMG values are measured differently due to various factors like muscle size, skin conductivity, or electrode placement [58]. Subjective satisfaction was analyzed based on the comfort levels in the back, hips, neck, and overall body using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied, 3 = neutral, and 5 = very satisfied). The data were statistically analyzed using a paired t-test (α = 0.05) conducted in MATLAB 2022a (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA), after confirming data normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test to ensure the assumptions for parametric analysis were met.

3.2. Experiment II: Long-Term Evaluation

3.2.1. Participants

In this experiment, participants included 20 university students (age: 24.5 ± 1.6), with 12 males and 8 females, who could maintain a sitting posture for an hour without any difficulty or back pain. Mean body size was a height of 171.1 ± 6.4 cm (160.3 to 183.5 cm) and a weight of 67.8 ± 10.9 kg (50.0 to 88.0 kg).

3.2.2. Apparatus

The same sEMG measurement equipment and chairs used in Experiment I were also used in Experiment II. Only sEMG measurements from the left and right erector spinae muscles, which are related to posture maintenance, were taken.

3.2.3. Experimental Design

The experiment was conducted using a four-step procedure (S1: introduction, S2: attaching sensors to the body, S3: main experiment, and S4: debriefing). First, the purpose and process of the experiment were explained to the participants, and informed consent was obtained. Second, sEMG sensors were attached to the participants’ left and right erector spinae muscles. Third, participants sat on each chair for one hour while watching a video, during which EMG data was measured. To prevent bending the head or back, the monitor was positioned at eye level. While watching the video, participants were instructed to maintain as correct a posture as possible while leaning against the backrest. Although standing up or excessively shifting positions was restricted, participants were allowed to adjust their posture naturally to avoid discomfort and ensure they could sit dynamically rather than rigidly in a single position. The experiments using the two chairs were conducted on different days for each participant. Finally, after two days of experiments, participants were compensated for their participation.

3.2.4. Analysis Method

In Experiment II, muscle fatigue was analyzed using frequency information from EMG measurements collected over a prolonged period. This method is widely considered to be effective for assessing muscle fatigue, as it quantifies the shift in frequency components associated with muscle fatigue [59,60]. Typically, as muscles become fatigued from prolonged use, a greater proportion of lower frequencies (e.g., 0–40 Hz) is observed, while higher frequencies diminish. In this study, the continuously measured EMG data over the entire experiment duration (1 h) were transformed into frequency data using Fast Fourier Transform. The frequency spectrum was segmented into 20 Hz intervals (0–20, 20–40, 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100 Hz), and the proportion of the total frequency content within each range was calculated and expressed as a percentage. This method provides a reliable quantitative measure of muscle fatigue by highlighting changes in frequency distribution over time, making it particularly suitable for analyzing prolonged sitting conditions. The results for the two chairs for each participant were compared using a paired t-test (α = 0.05) in MATLAB, after confirming data normality through the Shapiro–Wilk test to ensure that the assumptions for parametric analysis were satisfied.

4. Results

4.1. Experiment I: Short-Term Evaluation

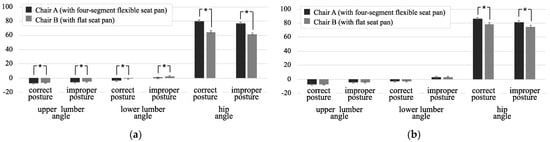

4.1.1. Lumber and Pelvic Rotation Angles

Significant differences in the joint angles were found between the two chairs, both when leaning and when not leaning against the backrest. When leaning against the backrest, Chair A demonstrated significantly greater values (mean difference: 0.8~15.3° by analysis conditions) in the upper lumbar angle, lower lumbar angle, and hip angle for both correct and improper postures compared to those of Chair B (Table 1, Figure 5a). This indicates that Chair A more effectively maintains the spine’s S-shape. When not leaning against the backrest, significant differences were observed only in the hip angle (6.8~7.3° by analysis conditions) for both correct and improper postures (Figure 5b).

Table 1.

Analysis results of lumber and pelvic rotation angles (unit: °).

Figure 5.

Analysis results in lumber and pelvic rotation angles: (a) leaning; (b) non-leaning (unit: °; * p < 0.05; error bar: standard error).

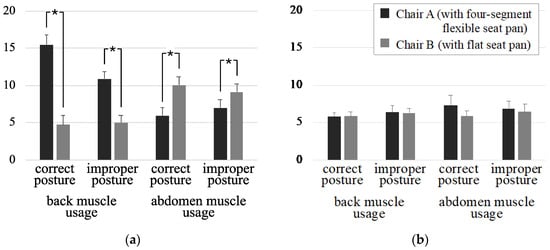

4.1.2. Muscle Use

Significant differences in muscle usage were observed between the two chairs only when leaning against the backrest. When leaning against the backrest, Chair A demonstrated significantly higher values in back muscle usage (5.9~10.8% by analysis conditions) and lower values in abdominal muscle usage (−4.2 ~ −2.1% by analysis conditions) for both correct and improper postures compared to Chair B (Table 2, Figure 6a). This suggests that Chair A more effectively maintains the spine’s S-shape using the back muscles. When not leaning against the backrest, no significant differences were observed (Figure 6b).

Table 2.

Analysis results of lumber and pelvic muscle usu (unit: %).

Figure 6.

Analysis results in back and abdomen muscle usage as %MVC: (a) leaning; (b) non-leaning (unit: %; * p < 0.05; error bar: standard error).

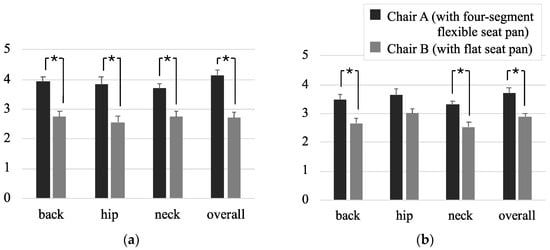

4.1.3. Muscle Use

Significant differences in subjective satisfaction were observed between the two chairs, both when leaning and not leaning against the backrest. For both occasions, the satisfaction scores for Chair A were 0.6 to 1.4 points higher on average than those for Chair B. Statistical significance was found in all cases except for the hip region when not leaning against the backrest (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Analysis results in subjective satisfaction: (a) leaning; (b) non-leaning (* p < 0.05; error bar: standard error).

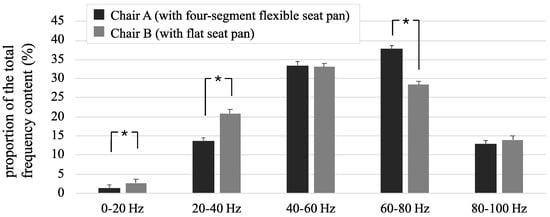

4.2. Experiment II: Long-Term Evaluation

The findings revealed that Chair A exhibited a lower frequency content percentage in the lower frequency ranges (0–40 Hz) and a higher percentage in the higher frequency range (60–80 Hz) compared to Chair B (Figure 8). Specifically, the frequency content percentages for Chair A in the lower frequencies (0–20 Hz: 1.3%; 20–40 Hz: 13.6%) were significantly reduced by an average of 47% and 34%, respectively, when compared to those of Chair B (0–20 Hz: 2.6%; 20–40 Hz: 20.8%). Furthermore, the frequency content percentage of Chair A in the higher frequency range (60–80 Hz) was 37.7%, which was significantly higher, by an average of 34%, compared to Chair B (28.4%). However, no significant differences were found in the frequency content percentages between the two chairs in the 40–60 Hz and 80–100 Hz ranges.

Figure 8.

Analysis results in muscle fatigue analysis (* p < 0.05; error bar: standard error).

5. Discussion

This study analyzed the characteristics of ergonomic chairs through both short- and long-term experiments, focusing on natural sitting actions and fatigue levels during prolonged sitting. Experiment I (short-term evaluation) allowed for the immediate assessment of characteristics while making a sitting posture, specifically the angles of the pelvis and back regions and muscle usage, as participants sat down in the chair from a standing position and adopted certain postures (either correct or improper, as defined in this study). Experiment II (long-term evaluation) enabled the analysis of differences in muscle fatigue in the lumbar region as participants sat for extended periods. These experiments verify that the proposed ergonomic chair facilitates the adoption of a correct sitting posture more easily and maintains the correct posture with less muscle fatigue over prolonged periods, thereby allowing for better posture sustainability.

The ergonomic chair with a four-segment flexible seat pan introduced in this study has proven beneficial in maintaining a correct posture across various sitting positions and conditions compared to conventional chairs. This segmented seat pan was designed with the intention of enabling localized flexibility and allowing each part of the pelvis and thigh to move more freely. From a biomechanical perspective, it was hypothesized that this would promote forward pelvic tilt and reduce the restriction of soft tissue movement around the ischial tuberosities, thus supporting a more natural S-shaped spinal posture. Although the ergonomic chair demonstrated slightly higher abdominal muscle activation when leaning forward, the level remained within functional ranges and did not indicate excessive muscular effort. Moreover, the increased activation of back muscles may help share the postural load, potentially reducing localized fatigue in the abdominal area over time. It was observed that, whether leaning against the backrest in the correct or improper posture, the ergonomic chair more naturally facilitated forward pelvic rotation and maintained the spine’s S-shape. In terms of muscle usage, while conventional chairs tend to engage the abdominal muscles more than the back muscles when leaning against the backrest, the proposed chair shows increased activation of the back muscles, which are crucial in supporting the S-shape of the spine [5,9,28,61]. When not leaning against the backrest, no significant difference was observed in the maintenance of the spine’s S-shape between the two types of chairs, although the ergonomic chair was better at encouraging forward pelvic rotation. Without backrest support, both types of chairs resulted in similar levels of back and abdominal muscle usage and spinal shape, highlighting the potential role of the seat pan design in influencing posture.

Subjective satisfaction levels showed smaller differences when sitting without back support compared to when leaning against it. This could be attributed to the biomechanical characteristics acting on the lumbar and abdominal regions being similar regardless of chair type when sitting without back support. However, when leaning against the backrest, the effects of the backrest design on posture and muscle usage must be considered, as the two chairs used in this study had different backrest designs. This difference in backrest design represents a limitation of the study, as it may have influenced the observed outcomes when leaning against the backrest. Despite this limitation, the ergonomic chair’s ability to allow greater forward pelvic rotation, even in non-leaning positions, suggests it could be a crucial factor in maintaining the lumbar S-shape during prolonged sitting periods. In addition to the flexible seat pan, the ergonomic chair developed in this study accommodates various body sizes by offering different chair leg lengths and backrest depths.

While previous studies have primarily focused on the ergonomic effects of backrests, this research concentrates on the design of seat pans and their impact on sitting posture. This study specifically examined postures without backrest support to isolate the effects of the seat pan, excluding the influence of the backrest. As noted previously, in the short-term sitting situation, no significant differences were observed in the joint angles or muscle usage (except for the pelvic angle) between the different chair types when not leaning against the backrest. Ergonomic guidelines for correct posture generally recommend avoiding prolonged sitting in a single position and instead encourage dynamic sitting. Given the assumption that seat pan design positively affects dynamic sitting (e.g., reducing muscle tension, distributing pressure on the spine, and decreasing back pain or discomfort), the seat pan design proposed in this study was specifically developed to promote such benefits. However, this study focused only on the biomechanical effects of prolonged sitting with backrest support and did not investigate the characteristics of the back, abdomen, hip, and thigh regions in relation to seat pan design during extended sitting without back support or with arm support. Furthermore, future research should examine how factors such as the presence or absence of cushions, cushion firmness, and chair height adjustment influence the effectiveness of the four-segment seat pan in promoting dynamic sitting. Additionally, future studies should consider evaluating the effects of the four-segment seat pan in specific task scenarios, such as computer work, rather than just during static prolonged sitting.

Our results regarding the dynamic seat pan showed that increased mobility and optimized pressure distribution may alleviate discomfort caused by static load concentrations on the ischial region. This finding is in line with previous studies highlighting the biomechanical implications of seat pan design. For example, Zemp et al. [41] emphasized that flat seat pans may restrict the natural movement of soft tissues under the ischial tuberosities, potentially leading to localized pressure peaks and ischemic effects. Similarly, Azghani et al. [40] demonstrated that variations in seat pan depth influenced the myoelectric activity of the lumbar erector spinae, supporting the role of pan geometry in muscular load distribution. Denes et al. [42] focused on pressure redistribution through body-centred chair development, and confirmed that the seat pan contour significantly affects pressure comfort. Choi and Sohn [21] found that flexible backrests and concave seat pans reduced posterior pelvic tilt and supported neutral lumbar alignment, while Kim et al. [32] showed that a segmented seat pan improves pressure relief and user-reported comfort. Together, these findings support the direction of our study, affirming that ergonomic seat pan design—particularly with adaptive or segmental structures—plays a critical role in minimizing localized pressure and supporting dynamic postural adjustment.

In this study, the lumbar angles were estimated using the Xsens system’s skeleton model, so there may be discrepancies between the estimated and actual angles of specific lumbar regions. The Xsens system generates its skeleton model using the rotation angles of a single sensor attached to the lumbar region (the pelvic sensor is located around L5 at the height of the anterior superior iliac spine, as defined by the Xsens system). In this study, the forward and backward rotation angles of the pelvic sensor were measured as participants sat on the chairs, influencing the degree of forward pelvic rotation and the spine’s S-shape, which were utilized in generating the Xsens skeleton model. Therefore, the Xsens system enabled significant analysis of the relative differences in sitting postures between the chairs. Notably, the angles provided in this study (upper lumbar, lower lumbar, and hip angles) may differ from the actual angular values measured in a human skeletal structure.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the ergonomic benefits of a chair with a four-segment flexible seat pan designed to maintain correct sitting posture. The results from both short- and long-term evaluations indicate that the proposed chair facilitates forward pelvic rotation and supports the formation of an S-shaped spine, thereby enhancing posture. Despite the limitations of this study in terms of the number of participants, their demographic and occupational diversity, and the types of chairs compared, it was confirmed that the ergonomic design of the seat pan could significantly influence the maintenance of correct sitting posture. Furthermore, the flexible characteristics of the seat pan were found to have positive effects on prolonged sitting by allowing continuous body movements while seated (e.g., dynamic sitting). However, due to the exploratory nature of this study and the limited sample size, no prior statistical power analysis was conducted. This limitation should be considered when interpreting the generalizability of the results, and future studies with larger, more diverse populations are recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.L. and C.P.; methodology, W.L.; software, S.P. and W.L.; validation, S.P., W.L. and C.P.; formal analysis, S.P., J.R. and Y.T.; investigation, S.P., J.R. and Y.T.; resources, W.L. and C.P.; data curation, S.P. and W.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., J.R. and Y.T.; writing—review and editing, W.L.; visualization, J.R. and W.L.; supervision, W.L.; project administration, W.L.; funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF; grant number 2020R1F1A1050076) and Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT; grant number RS-2025-02653088).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Handong Global University (2023-HGUR004; 1 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Wonsup Lee was employed by the the company Comfo Labs. Chanwook Park was employed by the company NOOGI. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Ellegast, R.P.; Kraft, K.; Groenesteijn, L.; Krause, F.; Berger, H.; Vink, P. Comparison of four specific dynamic office chairs with a conventional office chair: Impact upon muscle activation, physical activity and posture. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, B.Y.; Yoon, A. Ergonomics of office seating and postures. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2014, 33, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, C.Y.; Song, G.Y.; Jang, Y.S.; Ko, H.E.; Kim, H.D.; Park, G.; Hwang, J.B.; Jung, H.S. Development of ergonomic backrest for office chairs. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2015, 34, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Y.; Won, B.H. Ergonomic evaluation of trunk-forearm support type chair. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2014, 33, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zemp, R.; Taylor, W.R.; Lorenzetti, S. Seat pan and backrest pressure distribution while sitting in office chairs. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 53, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Estrada, M.; Vuohijoki, T.; Poberznik, A.; Shaikh, A.; Virkki, J.; Gil, I.; Fernández-García, R. A Smart Chair to Monitor Sitting Posture by Capacitive Textile Sensors. Materials 2023, 16, 4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimberg, L.; Goldoni Laestadius, J.; Ross, S.; Dimberg, I. The changing face of office ergonomics. Ergon. Open J. 2015, 8, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Kharti, S.; Tanna, K.; Vala, G. Are you sitting correctly? What research says: A review paper. Int. J. Multidiscip. Educ. Res. 2021, 10, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, L.M.; Neumann, W.P.; Hägg, G.M.; Kenttä, G. Fatigue and recovery during and after static loading. Ergonomics 2014, 57, 1696–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.; Gyi, D.; Mansfield, N.; Picton, R.; Hirao, A.; Furuya, T. Engineering movement into automotive seating: Does the driver feel more comfortable and refreshed? Appl. Ergon. 2019, 74, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Blyth, F.; Buchbinder, R. The Epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010, 24, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, P.; Lotfian, S.; Moezy, A.; Nejati, M. The study of correlation between forward head posture and neck pain in Iranian office workers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billy, G.G.; Lemieux, S.K.; Chow, M.X. Changes in lumbar disk morphology associated with prolonged sitting assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. PM&R 2014, 6, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, S.W.M.; Palsson, T.S.; Krebs, H.J.; Graven-Nielsen, T.; Hirata, R.P. Prolonged slumped sitting causes neck pain and increased axioscapular muscle activity during a computer task in healthy participants—A randomized crossover study. Appl. Ergon. 2023, 110, 104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Han, J.-S.; Kang, S.; Ahn, C.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, K.-T.; Kim, A.-R.; Hwang, J.-M. Biomechanical effects of different sitting postures and physiologic movements on the lumbar spine: A finite element study. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, N.; Maeda, S. Determination of backrest inclination based on biodynamic response study for prevention of low back pain. Med. Eng. Phys. 2010, 32, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillastrini, P.; Mugnai, R.; Bertozzi, L.; Costi, S.; Curti, S.; Guccione, A.; Mattioli, S.; Violante, F.S. Effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention on work-related posture and low back pain in video display terminal operators: A 3 year cross-over trial. Appl. Ergon. 2010, 41, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M.; Amick, B.C.; DeRango, K.; Rooney, T.; Bazzani, L.; Harrist, R.; Moore, A. The effects of an office ergonomics training and chair intervention on worker knowledge, behavior and musculoskeletal risk. Appl. Ergon. 2009, 40, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vink, P.; Hallbeck, S. Editorial: Comfort and discomfort studies demonstrate the need for a new model. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.R.; Kim, H.S. Development of a bodice block for women in their 20s with a turtle neck syndrome body shape. J. Fash. Bus. 2021, 25, 144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.; Sohn, M. Biomechanical comparison of the effects of two ergonomic chairs on the spine and pelvic postures: Conical pendulum stool versus semi-rigid flexible backrest chair. J. Korean Inst. Ind. Eng. 2022, 48, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yu, S.; Yang, H.; Pei, H.; Zhao, C. Effects of long-duration sitting with limited space on discomfort, body flexibility, and surface pressure. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 58, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gutierrez, M.; Toledo, M.J.; Mullane, S.; Stella, A.P.; Diemar, R.; Buman, K.F.; Buman, M.P. Long-term effects of sit-stand workstations on workplace sitting: A natural experiment. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2018, 21, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.; Coenen, P.; Howie, E.; Williamson, A.; Straker, L. The short term musculoskeletal and cognitive effects of prolonged sitting during office computer work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhsous, M.; Lin, F.; Bankard, J.; Hendrix, R.W.; Hepler, M.; Press, J. Biomechanical effects of sitting with adjustable ischial and lumbar support on occupational low back pain: Evaluation of sitting load and back muscle activity. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2009, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenesteijn, L.; Vink, P.; de Looze, M.; Krause, F. Effects of differences in office chair controls, seat and backrest angle design in relation to tasks. Appl. Ergon. 2009, 40, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenesteijn, L.; Ellegast, R.P.; Keller, K.; Krause, F.; Berger, H.; de Looze, M.P. Office task effects on comfort and body dynamics in five dynamic office chairs. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-D.; Chung, H.-A.; Park, J.-M.; Son, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Jwa, M.-T.; Park, J.-H.; Jung, H.-S. Development of spine curvature responsive chair backrest and verification of its effectiveness. Korean J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 29, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.D.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; He, L.H. Effects of backrest density on lumbar load and comfort during seated work. Chin. Med. J. 2012, 125, 3505–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianat, I.; Karimi, M.A.; Asl Hashemi, A.; Bahrampour, S. Classroom furniture and anthropometric characteristics of Iranian high school students: Proposed dimensions based on anthropometric data. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebe, K.; Griffin, M.J. Factors affecting static seat cushion comfort. Ergonomics 2010, 44, 901–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shin, J.; Kim, M.-S.; Kim, J. The effectiveness test of three-piece moving seat pan (v.2.0) by using EMG, motion analysis, and questionnaire. J. HCI Soc. Korea 2022, 17, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korakakis, V.; O’Sullivan, K.; O’Sullivan, P.B.; Evagelinou, V.; Sotiralis, Y.; Sideris, A.; Sakellariou, K.; Karanasios, S.; Giakas, G. Physiotherapist perceptions of optimal sitting and standing posture. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2019, 39, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, M.U.; Jung, H.; Shim, Y.S.; Ryu, T. Development of ergonomic balance seat (e-BASE) chair. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2013, 32, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.-H.; Park, R.-Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, J.-Y.; Yoon, S.-R.; Jung, K.-I. The effect of the forward head posture on postural balance in long time computer based worker. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 36, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.H.T.; Chiu, T.T.W.; Poon, A.T.K. The relationship between head posture and severity and disability of patients with neck pain. Man. Ther. 2008, 13, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, K.-S.; Kwon, J.-W. The effects of head position in different sitting postures on muscle activity with/without forward head and rounded shoulder. Korean Soc. Phys. Ther. 2014, 26, 140–146. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, L. The effect of postural correction on muscle activation amplitudes recorded from the cervicobrachial region. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2005, 15, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeong, J.-H.; Roh, J.-R.; Park, S.-B.; Kim, S.; Chung, K.-R. Development of tilting chair for maintaining working position at reclined posture. J. Ergon. Soc. Korea 2014, 33, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Azghani, M.R.; Nazari, J.; Sozapoor, N.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M.; Oskouei, A.E. Myoelectric activity of individual lumbar erector spinae muscles variation by differing seat pan depth. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 10, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, R.; Taylor, W.R.; Lorenzetti, S. Are pressure measurements effective in the assessment of office chair comfort/discomfort? A review. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 48, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denes, L.; Bencsik, B.; Horvath, P.G.; Antal, R.M. Chair development on the basis of body pressure distribution—A research effort. For. Prod. J. 2022, 72, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens, R.H.M.; Netten, M.P.; Van der Doelen, B. An office chair to influence the sitting behavior of office workers. Work 2012, 41, 2086–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lan, X.; Zhou, D.; Jiang, B. Research on Office Chair Based on Modern Office Posture. In Human-Computer Interaction. Interaction in Context; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 195–205. [Google Scholar]

- van Dieën, J.H.; De Looze, M.P.; Hermans, V. Effects of dynamic office chairs on trunk kinematics, trunk extensor EMG and spinal shrinkage. Ergonomics 2001, 44, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pynt, J.; Higgs, J.; Mackey, M. Seeking the optimal posture of the seated lumbar spine. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2009, 17, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, K.; O’Keeffe, M.; O’Sullivan, L.; O’Sullivan, P.; Dankaerts, W. The effect of dynamic sitting on the prevention and management of low back pain and low back discomfort: A systematic review. Ergonomics 2012, 55, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, S.; Spence, W.D.; Solomonidis, S.E. The Potential for Actigraphy to Be Used as an Indicator of Sitting Discomfort. Hum. Factors J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2009, 51, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, D.L.; Goossens, R.H.M.; Evers, J.J.M.; van der Helm, F.C.T.; van Deursen, L.L.J.M. Length of the spine while sitting on a new concept for an office chair. Appl. Ergon. 2000, 31, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, S.M.; Fenwick, C.M.J. Using a pneumatic support to correct sitting posture for prolonged periods: A study using airline seats. Ergonomics 2009, 52, 1162–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deursen, D.L.; Snijders, C.J.; van Dieën, J.H.; Kingma, I.; van Deursen, L.L.J.M. The effect of passive vertebral rotation on pressure in the nucleus pulposus. J. Biomech. 2001, 34, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wan, Q.; Zhao, H.; Li, J.; Xu, P. Hip positioning and sitting posture recognition based on human sitting pressure image. Sensors 2021, 21, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemp, R.; Taylor, W.R.; Lorenzetti, S. In vivo spinal posture during upright and reclined sitting in an office chair. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Park, S.y.; Yoo, W.g. Effect of EMG-based Feedback on Posture Correction during Computer Operation. J. Occup. Health 2013, 54, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movella Technologies. MVN Biommechanical Model. Available online: https://base.movella.com/s/article/Xsens-Biomechanical-Model?language=en_US (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Vlaović, Z.; Domljan, D.; Župčić, I.; Grbac, I. Evaluation of office chair comfort. Drv. Ind. 2016, 67, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreischarf, M.; Bergmann, G.; Wilke, H.-J.; Rohlmann, A. Different arm positions and the shape of the thoracic spine can explain contradictory results in the literature about spinal loads for sitting and standing. Spine 2010, 35, 2015–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merletti, R.; Parker, P. Electromyography: Physiology, Engineering, and Noninvasive Applications; Wiley-IEEE Press: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y. The effects of load, flexion, twisting and window size on the stationarity of trunk muscle EMG signals. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2012, 42, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.B.; de Faria, L.P.; Monteiro, A.M.; Lima, J.L.; Barbosa, T.M.; Duarte, J.A. EMG Signal Processing for the Study of Localized Muscle Fatigue—Pilot Study to Explore the Applicability of a Novel Method. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waongenngarm, P.; Rajaratnam, B.S.; Janwantanakul, P. Internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscle fatigue induced by slumped sitting posture after 1 hour of sitting in office workers. Saf. Health Work. 2016, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).