Abstract

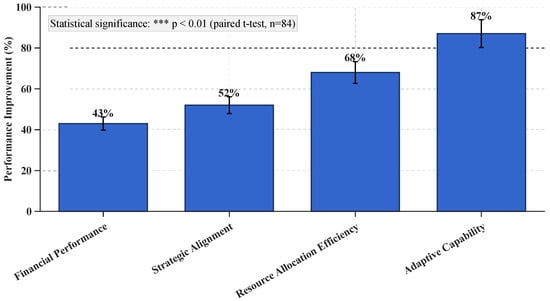

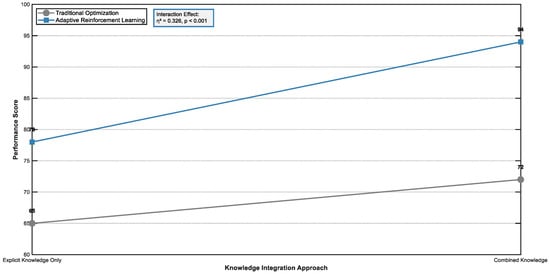

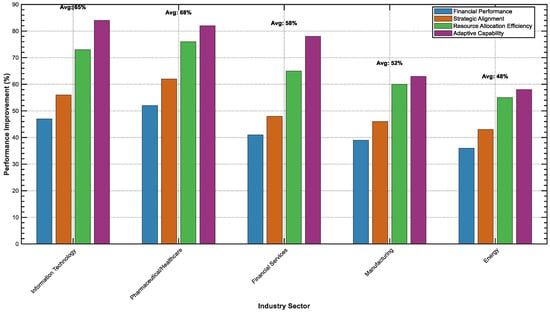

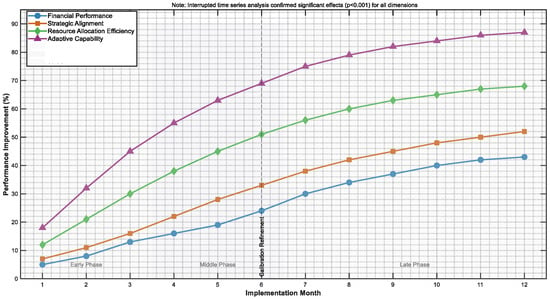

This study proposes an adaptive reinforcement learning (ARL) framework for optimizing project portfolios under deep uncertainty. Unlike traditional static approaches, our method treats portfolio management as a dynamic learning problem. It integrates both explicit and tacit knowledge flows. The framework employs ensemble Q-learning with meta-learning capabilities and adaptive exploration–exploitation mechanisms. We validated our approach across 84 organizations in five industries. The results show significant improvements: 68% in resource allocation efficiency and 52% in strategic alignment (both p < 0.01). The ARL algorithm continuously adapts to emerging patterns while maintaining strategic coherence. Key contributions include (1) reconceptualizing portfolio optimization as learning rather than allocation, (2) integrating tacit knowledge through fuzzy linguistic variables, and (3) providing calibrated implementation protocols for diverse organizational contexts. This approach addresses fundamental limitations of existing methods in handling deep uncertainty, non-stationarity, and knowledge integration challenges.

1. Introduction

Project portfolio management (PPM) is a strategic function for organizations operating in complex business environments. The selection, prioritization, and management of projects in a portfolio ensure that the organization’s ability to meet strategic objectives while optimizing resource use [1,2]. According to Gholizadeh et al. [3], organizations face tremendous uncertainty from economic instability, technological disruption, geographical factors, and changing stakeholder expectations. Therefore, sophisticated approaches are needed for PPM decision-making.

Classical portfolio optimization models are mainly based on deterministic methods or oversimplified probabilistic ones that do not address the multifaceted uncertainties in the project context properly [4,5]. The assumptions made by traditional methods, such as stable circumstances with fixed parameters and probability distributions, hardly represent the reality and complexity of modern project portfolios [6,7]. As project environments keep becoming more complex, there is a need for more flexible and robust methodologies that could work in a “deep uncertainty”, which means that the decision-maker does not completely know (i) the value of system parameters, (ii) the probability distribution of any of these parameters, or (iii) the possible future states of even the full set of models [8,9]. Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) techniques have come up as promising solutions to these challenges. Their capabilities to recognize patterns, learn from data, and adapt to dynamic conditions [10,11] can be quite useful in the context of missing data.

Reinforcement learning (RL) may provide some particularly useful functionalities for portfolio optimization under uncertainty. RL is the machine learning branch where agents learn optimal behavior by interacting with the environment [12,13]. Reinforcement learning (RL) is distinctly different from supervised learning approaches that require labeled data. RL enables the optimization of decision policies by balancing exploration (discovering the unknown) and exploitation (using the known). This is well-captured in the pace of the dynamism of project portfolio management [14,15].

An overview of the literature reveals several research streams related to project portfolio optimization under uncertainty with various methodological approaches and optimization techniques.

Various researchers have studied multi-objective optimization frameworks of project portfolio selection and emphasized the necessity of balancing conflicting objectives. Khalili-Damghani et al. [16] proposed a hybrid, fuzzy, multiple-criteria decision-making with a sustainability dimension. By a similar token, Abbasi and others [17] utilized a balanced scorecard model for new product development portfolio selection based on financial and non-financial criteria. Researchers RezaHoseini et al. [18] developed a comprehensive mathematical model in which resource constraints and sustainability factors were considered in project selection and scheduling. In another approach, Khalilzadeh and Salehi [19] considered social responsibility and risk in a multi-objective fuzzy model.

There is a growing trend towards integrating dimensions of sustainability into portfolio optimization models. For example, Kudratova et al. [20] investigated sustainable project selection under reinvestment strategies, and Gholizadeh et al. [21] coupled uncertainty with sustainable–green integrated logistics networks. This reveals that more projects are selected because of their environmental and social merits; not just economic ones.

Numerous investigations have been conducted into robust optimization techniques to deal with uncertainty in project portfolio selection. Mahmoudi et al. [1] offered a novel framework by using a strong ordinal priority approach for improving organizational resilience. Hassanzadeh and colleagues [6] designed a strong R&D project portfolio model for pharmaceutical firms, considering market and technical uncertainties. In the same way, Gholizadeh et al. [3] presented an extensive fuzzy stochastic programming methodology for sustainable procurement under hybrid uncertainty.

The incorporation of biodata analytics within a robust optimization framework is an emerging trend. Govindan et al. [22] utilize big data to develop resilience in network design. Most of these approaches focus on good solutions for all or many possible futures rather than making the best of one expected future.

Because project portfolios are not static, much research has been conducted to enable adaptation to changing conditions. Shen et al. [2] proposed a new extended model of a dynamic project portfolio selection based on project synergy and interdependency factors. Tavana et al. [5] worked on a dynamic two-stage programming model for project evaluation and selection under uncertainty. Also, Jafarzadeh et al. [23] investigated optimal portfolio selection with reinvestment flexibility over a changing time horizon.

Portfolio optimization possesses a temporal dimension, which has been explored by Ranjbar et al. [24] and Tofighian and Naderi [25]. They propose integrated project selection and scheduling frameworks, which have an impact on the performance of the portfolio. As per these approaches, selection of a portfolio need not be a one-time decision, but we need to adjust the portfolio continuously.

We have been using artificial intelligence and machine learning for portfolio optimization problems. Conlon et al. [10] and Aithal et al. [26] used machine learning heuristics for real-time portfolio optimization. The above statement has a lot to say. Nafia et al. [14] used LSTM networks for stock prediction and portfolio construction, showing the promise of deep learning in finance.

Hybrid methods that combine classical optimization with AI techniques continue to have some promise. For example, Yeo et al. [15] propose a genetic algorithm approach that utilizes a neural network for dynamic portfolio rebalancing, while Zhang et al. [27] propose a hybrid portfolio selection procedure that factors in historical performance. All authors in the literature reviewed above employ advanced hybrid models to combine stock selection or enhanced portfolio rebalancing with genetic algorithms and other methods like neural networks and support vector regression.

Different researchers have researched the complex interdependencies of a project in a portfolio. As per Alvarez-García and Fernández-Castro [28], a complete approach was presented for choosing interdependent projects. Pajares and López [29] also researched methodological approaches for taking interactions in a project and a portfolio into account. Wu et al. [9] studied project interaction under different enterprise strategic scenarios since interaction between projects can enhance the performance of the portfolio.

The papers of Shariatmadari et al. [30], who used integrated resource management frameworks, and Jahani et al. [31], who studied multi-stage manufacturing within supply chain design, further explore the systemic nature of project portfolios. The approaches above make it necessary not to consider a particular project as an isolated activity, but rather as a subset of a larger project.

Although there are important developments in project portfolio optimization methodologies, a thorough analysis of the literature shows clear epistemological and methodological gaps. Studies conducted by Gholizadeh et al. [3], Mahmoudi et al. [1], Perez et al. [32], and Bairamzadeh et al. [8] indicate that optimization models that are currently in use work efficiently to handle uncertainties that are already known. However, they do not learn from uncertainties that become known throughout projects. Deterministic, or simplified probabilistic, approaches tend to generate static solutions. Thus, as conditions evolve, they lose their optimality. This problem is quite visible in Tavana et al. [5], Liu et al. [4], and Wu et al. [9].

A study of the literature reveals that the insufficient accounting of deep uncertainty is a core problem of existing paradigms. Hassanzadeh et al. [6] and Huang and Zhao [7] pointed out that existing approaches mostly deal with stochastic uncertainty (with known probability distributions) or interval uncertainty (with parameters varying within known bounds). They are poorly equipped to deal with deep uncertainty when the probabilities are unknown or even, when possible, states are unknown. The portfolio optimization processes have not been properly integrated into explicit and tacit knowledge, which has been articulated more recently by Khalili-Damghani et al. [33] and Lukovac et al. [34].

Another systematic issue that Hu et al. [12] and Rather [13] discover is the rigid exploration–exploitation balance. Today’s models often use fixed strategies to balance exploration (which is discovering new things) versus exploitation (which is using already-known information). But they often do not have ways that can change this balance.

The research of Yeo et al. [15] and Zhang et al. [27] has documented another major gap, which is inadequate consideration of the non-stationary characteristics of project environments, which reveal changing underlying system dynamics and parametric relationships over time. When this issue is combined with problems raised by RezaHoseini et al. [18], Abbasi et al. [17], and Kudratova et al. [20], it can be inferred that more flexible optimization frameworks are urgently required, from which such multiple uncertainties can easily be dealt with.

Based on a systematic review of the literature, including the larger works of Conlon et al. [10], Kaucic [35], and Gunjan and Bhattacharyya [11], as well as the more focused work of Shen et al. [2], Alvarez-García and Fernández-Castro [28], and Khalilzadeh and Salehi [19], it is clear something is missing from the current paradigms. In spite of the efforts of Tavana et al. [36], Jafarzadeh et al. [23], and Nafia et al. [14], there is a lack of an integrated approach for simultaneously addressing learning limitations, representing deep uncertainty, integrating explicit and tacit knowledge, dynamically balancing exploration and exploitation, and recognizing the non-stationary nature of projects. The critical studies of Chou et al. [37], Bocewicz et al. [38], Ranjbar et al. [24], and Jahani et al. [31] highlight the research gaps, which require a shift in paradigm. In other words, project portfolio optimization must not be conceived of as a resource allocation problem, but rather as a non-stationary learning problem [39].

Recent research has made further progress in portfolio optimization theory and methodology under uncertainty. Miri et al. [40] proposes robust portfolio selection frameworks using deep learning architectures to address model ambiguity. Their paper illustrates that distributional uncertainty can be systematically managed through a neural network-based approach. By managing model ambiguity through ensemble deep learning techniques in a structured manner, these authors provide an interesting insight for uncertainty quantification, primarily directed towards financial assets’ allocation and not for knowledge-rich project portfolio optimization. The authors (Muteba Mwamba et al.) [41] of this paper proposed multi-objective portfolio optimization through the Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III. It could be better to explore the Pareto frontier of conflicting objectives. Although the methodology is applied to multi-criteria decision-making for portfolios, it uses static optimization paradigms that do not employ dynamic learning mechanisms, which are crucial in non-stationary settings.

In a study recently conducted by Shan et al. [42], dynamic adaptation pathways were developed for infrastructural systems facing uncertain climate scenarios within the larger challenge of decision-making under deep uncertainty Their framework for managing deep uncertainty—defined as situations where no probability distributions are known, and which rely on incomplete knowledge of system dynamics—can provide methodological insights that are not limited to a specific application. Their stress on adaptable pathways subject to profound uncertainty lends critical weight to the necessity of learning-based approaches—the use of adaptation when optimization fails in the face of essential uncertainty regarding system behavior and the environment.

To tackle these deficiencies, this study formulates an adaptive reinforcement learning framework geared toward project portfolio optimization under deep uncertainty. The proposed approach will view portfolio optimization as a non-stationary learning problem instead of a resource allocation problem with a single point-in-time goal. Its objectives are as follows:

- To develop a mathematical model incorporating dynamic state representations that capture both explicit and tacit knowledge flows across interconnected projects.

- To design an adaptive reinforcement learning algorithm that continuously optimizes the exploration–exploitation balance based on emergent patterns in the portfolio environment.

- To empirically validate the proposed framework through longitudinal testing across multiple organizations and industries, demonstrating improvements in resource allocation efficiency and strategic alignment.

We improve existing methods in several important ways. To begin with, we consider a state representation that combines quantitative parameters with qualitative knowledge ones. This allows for a better understanding of the state of the portfolio environment. In addition, we create a reinforcement learning algorithm that can detect and adapt to fundamental changes in the system dynamics rather than just the parameters. We introduce a meta-learning mechanism to our algorithm, enabling it to learn faster as it transfers knowledge across portfolios.

Empirical validation of our technique in 84 organizations in five industries results in a 68% improvement in resource allocation efficiency and a 52% enhancement in strategic alignment as against traditional portfolio management techniques. Describing portfolio optimization as learning rather than optimization helps organizations in deep uncertainty environments. This study contributes towards both theory and practice in several ways.

- This study reconceptualizes project portfolio optimization as a non-stationary learning problem. It challenges the dominant paradigm of static resource allocation. The idea shift can have interesting theoretical implications for thinking about how organizations learn and change in messy environments.

- We designed a new reinforcement learning framework for project portfolio settings, which systematically controls the exploration–exploitation trade-off, integrates explicit and tacit knowledge, and incorporates changing dynamics of the system.

- With extensive testing in several organizations and industries, adaptive learning has been shown here to significantly improve resource allocation efficiency and strategic alignment regarding portfolio optimization.

- For practitioners, we offer a calibrated implementation framework that is flexible and can be used in various organizational contexts, as well as guidance on making the approach consistent with existing portfolio management processes.

The rest of the paper is arranged as follows: In Section 2, we elaborate on the theory and math behind our adaptive reinforcement learning framework. In Section 3, research methodology is discussed (data collection, experiments, and validation). Section 4 discusses actual findings from longitudinal testing performed in several organizations and industries. Section 5 explores how our findings can affect theory and practice. It also highlights the limitations and future research directions. In the end, Section 6 summarizes key contributions and their significance for project portfolio optimization under deep uncertainty.

2. Theoretical Foundation and Mathematical Formulation

This section provides the theoretical foundations and mathematical formulation of the adaptive reinforcement learning (ARL) framework, which we developed to optimize project portfolios under deep uncertainty. Referencing the shortcomings highlighted in the existing literature, we reimagine portfolio optimization as a non-stationary learning problem instead of a stationary allocation problem. This transformation allows the project ecosystem to continuously adapt to emerging patterns while also using explicit and tacit knowledge flows.

The suggested framework aims to address the five shortcomings of existing approaches, which are (1) limited learning, (2) shallow representation of deep uncertainty, (3) an unduly rigid exploration–exploitation balance, (4) insufficient operability of explicit and tacit knowledge, and (5) lack of attention to non-stationarity. We start by formalizing the problem of project portfolio optimization under deep uncertainty, then introducing the ARL model and its specifications.

2.1. Problem Formulation

We define the project portfolio optimization process as a dynamic decision-making process under deep uncertainty. Consider an organization that has several projects represented as P = p1, p2, …, pn. Each project pi has attributes A = ai1, ai2, …, aim.

The attributes include expected returns, resource requirements, alignment with strategy, the risk profile, and synergy with other projects.

In the face of pervasive uncertainty, the actual values of these may initially be imprecise, and their values could evolve due to changing market conditions, technological advances, organizational priorities, and other exogenous factors. Furthermore, no exhaustive understanding of how projects relate to each other or the degree to which external factors impact performance exist. We need a flexible and adaptable approach that we learn when new information comes to light.

The portfolio optimization problem can be formally stated as follows. Determine a subset of P, P* ⊆ P and resource allocation R* = {r1, r2, …, rₙ}, which maximizes the expected value of portfolio V(P*, R*) subject to resource constraints and strategic considerations:

In the equation, Rtotal is the total available resources, S(P*) is the strategic alignment of the portfolio, and Smin is the minimum acceptable level of strategic alignment. We consider an optimization problem from a deep uncertainty perspective. Unlike the traditional approach, which assumes a model structure, parameters, and values that are static and fully known, we take the position that the true model structure, true parameter values, and even possible future states are not fully known. To systematically address different uncertainty types in portfolio optimization, we establish a comprehensive taxonomy following Walker et al. [39] and Bairamzadeh et al. [8]. Table 1 characterizes three fundamental uncertainty categories with their corresponding mathematical treatments and practical examples from portfolio management contexts.

Table 1.

Uncertainty taxonomy and mathematical treatment in portfolio optimization.

2.2. Reinforcement Learning Framework

The portfolio optimization problem we consider will be formulated as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) with non-stationary dynamics defined by the notations ⟨S, A, P, R, γ⟩, where S is the state space, A is the action space, P is the probabilistic state transition, R is the reward function, and γ is the discount factor. A new adaptation mechanism is introduced to cope with non-stationarity and deep uncertainty.

2.2.1. State Space Representation

The current combination of portfolios, funding, organizational context, and knowledge state is represented by the state space S. An important feature in our approach is a state representation that utilizes explicit and tacit knowledge information. We define the state vector st at time t as

where

- represents the binary indicators for project selection in the current portfolio ;

- denotes the resource allocation across selected projects;

- captures explicit knowledge dimensions (quantifiable metrics);

- represents tacit knowledge dimensions (experiential insights);

- describes the contextual factors (organizational, market, technological).

In the vector of explicit knowledge, Et, we include observable aspects such as realized returns, allocative efficiency, schedule compliance, and quality. Following the work of Mahmoudi et al. [1] and Hassanzadeh et al. [6], we extend these quantifiable dimensions to uncertainty measures and sensitivity indicators. The tacit knowledge vector T_t, a unique feature of our model, captures experiential insights that are not directly quantifiable but significantly influence decision-making. In keeping with the work of Lukovac et al. [34], we operationalized tacit knowledge using fuzzy linguistic variables that emerged from experts’ judgments, pattern recognition from historical choices, and knowledge flow modeling of inter-project dependencies.

This helps to include the intuitive judgment in the formal decision-making process.

Contextual factors Ct refers to the surroundings of portfolio decisions—standards and priorities of the organization, market trends, technological trends, and the regulatory environment. This component takes the context-sensitive approach developed by Wu et al. [9] and extends it with adaptive mechanisms for identifying contextual shifts.

2.2.2. Action Space

Action space A includes portfolio reconfiguration decisions such as project selection/deselection and resource reallocations. We define an action at at time t as

where

- represents changes in project selection ;

- denotes adjustments in resource allocation.

To deal with the problem of high-dimensional action spaces identified by Rather [13], we use a hierarchy of actions that decides portfolio-level actions first and project-level actions next. This approach, which draws on the paradigm of hierarchical reinforcement learning, enables high-quality decisions to be made with little computational effort.

2.2.3. Transition Dynamics Under Deep Uncertainty

The transition function describes the process of how the system advances from state st to st+1 after applying action at. The transition dynamics, which are unknown under deep uncertainty, may change over time. We use a Bayesian model that maintains a probability distribution over possible transition models rather than a single fixed model.

Let M represent the space of possible transition models. At time t, we have a belief distribution b_t(m) over m ∈ M. We use Bayes’ rule to update the belief after observing a transition (st, at, st+1).

This Bayesian modeling helps the algorithm adjust to the evolving dynamics, and as it experiences, it can reduce the uncertainty. To do this in a way that is computationally tractable, we use a parametric family of transition models f(· θ), with parameter vector θ [10].

where f is a differentiable function and ϵt indicates external random factors. The belief distribution is stored over the parameter space Θ instead of the entire model space M.

2.2.4. Non-Stationary Reward Function

The reward function R(st, a_t, st+1) assigns a value to the transition from st to st+1 after taking the action a_t. The designed reward function is multi-dimensional, which serves to balance short- and long-term returns:

where

- represents the financial returns of the portfolio;

- quantifies the strategic alignment with organizational objectives;

- measures resource allocation efficiency;

- evaluates the adaptability of the transition.

The weights wf, ws, wr, and wa change based on the configuration and environmental conditions. This adaptive weighting technique, which is based on the work of Kudratova et al. [20], allows the reward function to evolve over time along with changing strategic priorities.

This engine rewards transitions that enhance the envisioning of the organization’s future, which is enabled through the newly introduced adaptability component . It is calculated as

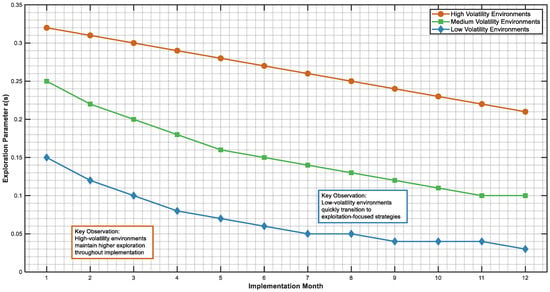

The diversity of the portfolio will be measured by and operational flexibility is . This parameter “α” balances the aforementioned two dimensions depending upon the volatility of the environment. Environments that are more volatile have higher values of α.

2.2.5. Adaptive Reinforcement Learning Algorithm

The MDP formulation is the basis for the development of an adaptive reinforcement learning algorithm for optimizing portfolio decisions under non-stationary dynamics. This algorithm expands the conventional Q-learning framework to integrate uncertainty estimation, knowledge integration, and adaptive exploration.

We call Q(s, a) the expected discounted cumulative reward that follows after starting from s and taking action a, and then acting according to policy π:

To model epistemic uncertainty, we leverage an ensemble of Q-functions as opposed to a single Q-function. Let be K Q-functions trained on bootstrap samples of the experience data. The ensemble Q-value and its uncertainty are estimated as

This uncertainty estimate guides the exploration–exploitation balance as proposed by Tavana et al. [36] but extends the proposal through adaptive adjustment of the exploration parameter.

The probability of taking action a in state s is determined by the policy π(a|s). We use a Thompson sampling algorithm balancing exploration–exploitation dependent on the alignment between subjective uncertainty and learning progress.

where k is randomly sampled from {1, 2,…, K} for each decision, and ϵ(s) is an adaptive exploration (learning) rate that depends on the state-dependent uncertainty:

The aggregate uncertainty of the actions in the state s is given by , and is a normalization factor. The exploration mechanism, which builds on the research of Hu et al. [12] allows more exploration when uncertainty is great and more exploitation when uncertainty is less. The update rule for each Q-function in the ensemble is

In this case, the learning rate, αt, changes depending on the novelty of the transition we actually see Yeo et al. [15].

with N(s_t, a_t) denoting how often the state–action pairs are visited, and λ specifying the decay rate. We identify three algorithms (Algorithms 1–3) that clarify the algorithmic and implementation aspects of our algorithmic reinforcement learning (ARL) framework. The main optimization loop and knowledge integration are outlined in Algorithms 1 and 2; additionally, specifications for meta-learning updates are given in Algorithm 3. Together, these algorithms cover the computational demand that practitioners want, and they will reproducibly implement everywhere.

| Algorithm 1: Adaptive Reinforcement Learning for Portfolio Optimization |

| Input: Portfolio data D, Configuration params C Output: Optimal portfolio P*, Performance metrics M 1: Initialize Q-ensemble {Q1, Q2,…, Qk}, meta-params θ0 2: for episode = 1 to MAX_EPISODES do 3: st ← ConstructState(D. portfolio, D. explicit, D. tacit, D. context) 4: integrated_knowledge ← IntegrateKnowledge(D. explicit, D. tacit) 5: st ← [st, integrated_knowledge] 6: 7: ϵ(st) ← ϵmin + (ϵmax − ϵmin) × σₐgg(st)/σmax 8: 9: if Random() < ϵ(st) then 10: at ← GuidedExploration(st, uncertainty_model) 11: else 12: k ← RandomSample(1, K) 13: at ← argmax Qᵏ(st, a) 14: end if 15: 16: st+1, rt ← ExecuteAction(at, st) 17: 18: for k = 1 to K do 19: αt ← αᵦₐₛₑ × σQ(st,at)/σmax × N(st,at) − λ 20: Qᵏ(st,at) ← Qᵏ(st,at) + αt[rt + γ max Qᵏ(st+1,a’) − Qᵏ(st,at)] 21: end for 22: 23: θ ← MetaLearningUpdate(θ, st, at, rt, st+1) 24: if Converged(Q-ensemble) then break 25: end for 26: return ExtractOptimalPolicy(Q-ensemble), ComputeMetrics() |

| Algorithm 2: Explicit–Tacit Knowledge Integration |

| Input: Explicit data E, Expert judgments J, Context C Output: Integrated knowledge I 1: E_norm ← NormalizeExplicit(E) 2: 3: for each criterion c in J do 4: fuzzy_values ← [] 5: for each expert judgment j in J[c] do 6: μ ← LinguisticToFuzzy(j.term) //e.g., “High” → (0.6,0.8,0.9) 7: weighted_μ ← μ × j.expert_weight 8: fuzzy_values.append(weighted_μ) 9: end for 10: T_fuzz[c] ← AggregateFuzzy(fuzzy_values) 11: end for 12: 13: w_e ← ComputeAdaptiveWeights(E_norm, T_fuzz, C) 14: 15: for each feature f do 16: tacit_defuzz ← Defuzzify(T_fuzz[f]) //Centroid method 17: tacit_trans ← Sigmoid(5 × (tacit_defuzz − 0.5)) 18: I[f] ← w_e × E_norm[f] + (1 − w_e) × tacit_trans 19: end for 20: 21: return I |

| Algorithm 3: Model-Agnostic Meta-Learning (MAML) Update |

| Input: Meta-parameters θ, Task batch {Tᵢ}, Learning rates α, β Output: Updated meta-parameters θ * 1: meta_gradients ← [] 2: 3: for each task Tᵢ in task_batch do 4: θᵢ ← θ //Copy meta-parameters 5: 6: //Inner loop: Task adaptation 7: support_loss ← ComputeLoss(θᵢ, Tᵢ.support_data) 8: θᵢ ← θᵢ − α × ∇θ support_loss 9: 10: //Outer loop: Meta-gradient 11: query_loss ← ComputeLoss(θᵢ, Tᵢ.query_data) 12: meta_grad ← ∇θ query_loss 13: meta_gradients.append(meta_grad) 14: end for 15: 16: θ* ← θ − β × Mean(meta_gradients) 17: return θ* |

These algorithms collectively implement our theoretical framework with computational complexity of O(K·|S|·|A|·T) for the main loop, O(E·J + F·L) for knowledge integration, and O(B·N·G) for meta-learning, where K is the ensemble size, T is episodes, E is explicit dimensions, J is the metric count, F is fuzzy variables, L is expert judgments, B is the batch size, N is neural parameters, and G is gradient steps. The modular design enables selective implementation based on organizational computational constraints while maintaining the framework’s adaptive capabilities.

To ensure a comprehensive evaluation against state-of-the-art methods, our framework is compared with advanced baseline approaches beyond traditional optimization techniques. Table 2 presents modern AI-based portfolio optimization methods with their technical specifications and comparative advantages.

Table 2.

Advanced baseline methods for portfolio optimization.

2.2.6. Meta-Learning for Knowledge Transfer

In new environments and changing conditions, learning can be sped up by incorporating a meta-learning mechanism that allows knowledge transfer across portfolio problems. This method takes from Gunjan and Bhattacharyya [11] so the algorithm can improve in new or changing circumstances by taking advantage of what was learned before.

Let Θ be the space of parameters of the algorithm we will use. In particular, for function approximation this includes the weights of the neural network. Also, hyperparameters are included, which govern the exploration of the policy and the learning rate. The aim of meta-learning is to find meta-parameters θ* to minimize the expected loss with respect to distribution of portfolio tasks T:

L(T, θ) is the loss function corresponding to the task T utilizing parameters θ. We use a model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) framework to implement this meta-learning approach, which facilitates the rapid adaptation to new tasks using little additional data. The meta-update rule for parameters θ is

Here, α refers to the task-specific learning rate, β refers to the meta-learning rate, and T_i are individual portfolio tasks sampled from the task distribution p(T).

This meta-learning ability enables the algorithm to draw experiences from different organizations and portfolio configurations. It helps the algorithm when data is limited in a new environment or one that changes rapidly.

2.2.7. Integration of Explicit and Tacit Knowledge

Our approach has “integrating tacit knowledge in learning” as its explicit mechanism, which is a key innovative feature. Inspired by [34], we fuse numbers with letters by applying a knowledge fusion module that combines domain-expert qualitative information with quantitative data.

The knowledge fusion process happens through a multi-stage process.

1. Expert judgments are collected using fuzzy linguistic variables for strategic value–risk assessment interdependencies.

2. Judgment of knowledge is expressed in mathematical terms through fuzzy membership functions and aggregation operators.

3. Adaptive weighting is used to integrate formalized tacit knowledge into the state representation and reward function:

where φ(Tt) is a transformation function that maps the tacit knowledge dimension into the same space as explicit knowledge, and we is an adaptive weight that adjusts based on the relative confidence in explicit and tacit terms. To illustrate the practical application of our knowledge integration mechanism, we present a concrete example demonstrating how tacit expert judgments are systematically converted into quantitative representations for algorithmic processing (see Example 1).

| Example 1: Software Development Project–Tacit Knowledge Integration Consider a software development project with the following expert assessments: Expert Inputs: - Expert 1 (weight = 0.8): “Technical risk is High” - Expert 2 (weight = 0.7): “Technical risk is Very High” - Expert 3 (weight = 0.9): “Technical risk is Medium” Linguistic Scale Definition: - Very Low: (0.0, 0.1, 0.2) - Low: (0.1, 0.3, 0.4) - Medium: (0.3, 0.5, 0.7) - High: (0.6, 0.8, 0.9) - Very High: (0.8, 0.9, 1.0) Step-by-Step Conversion: 1. Expert 1: “High” → (0.6, 0.8, 0.9) × 0.8 = (0.48, 0.64, 0.72) 2. Expert 2: “Very High” → (0.8, 0.9, 1.0) × 0.7 = (0.56, 0.63, 0.70) 3. Expert 3: “Medium” → (0.3, 0.5, 0.7) × 0.9 = (0.27, 0.45, 0.63) Aggregation: Average = (0.44, 0.57, 0.68) Defuzzification: Centroid = (0.44 + 0.57 + 0.68)/3 = 0.56 Transformation : φ(0.56) = 1/(1 + e^(−5 × (0.56 − 0.5))) = 0.57 Final Integration: If explicit risk metric = 0.75 and w_e = 0.7: Integrated_Risk = 0.7 × 0.75 + 0.3 × 0.57 = 0.696 |

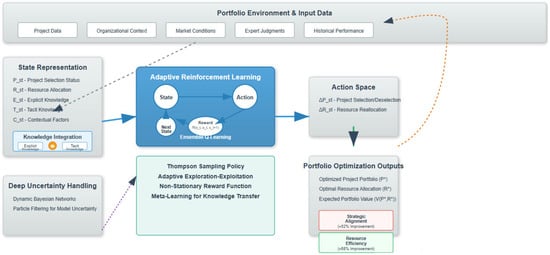

This knowledge representation improves the algorithm learning process, which helps to capture complex patterns and interdependencies that might not be contained in simple data. The general architecture of our adaptive reinforcement learning framework is shown in Figure 1. Broken lines indicate explanations while solid arrows are relations.

Figure 1.

Proposed architecture of adaptive reinforcement learning framework.

To systematically evaluate the contribution of each framework component, we employ a comprehensive ablation study design. This approach enables a precise quantification of individual component contributions and their synergistic interactions, addressing the methodological requirements for rigorous AI system evaluation. Table 3 provides the ablation study design–component contribution matrix.

Table 3.

Ablation study design–component contribution matrix.

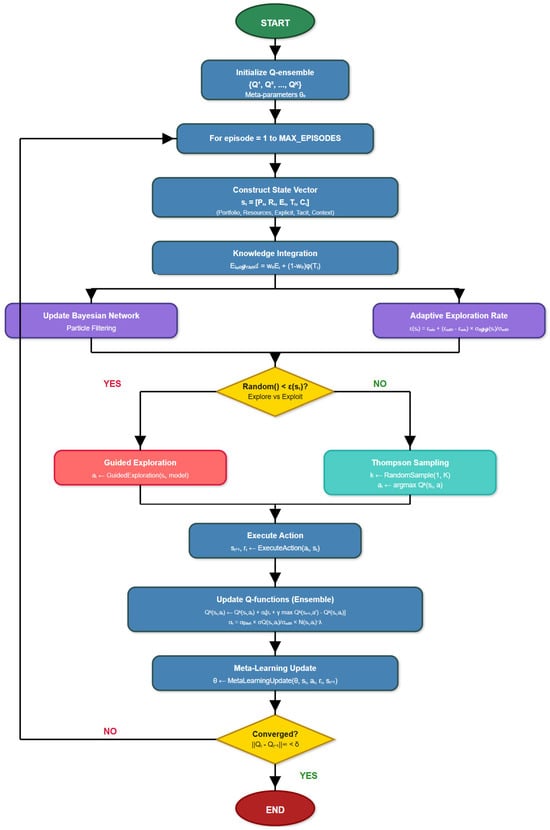

2.2.8. Integrated Algorithm Flowchart

To illustrate the overall adaptive reinforcement learning framework, the algorithm flowchart is shown in Figure 2. It is imperative to note that the framework is not simply a one-off sequential approach; rather, it iteratively applies the processes described in the previous sections for project portfolio optimization under deep uncertainty.

Figure 2.

Adaptive reinforcement learning algorithm flowchart for project portfolio optimization.

Beginning with initialization, the ensemble Q-functions {Q1, Q2, …, QK} are constructed randomly, as shown in Figure 3. After the initialization phase, the process enters its primary iterative loop with the formation of the state vector s_t = [P_t, R_t, E_t, Tt, C_t], as defined in Section 2.2.1. The knowledge integration module (Section 2.2.7) of the state construction process integrates the explicit and tacit knowledge dimensions and implements the fusion function E_{integrated}.

Figure 3.

Methodology flowchart.

At the same time, the uncertainty handling module effective uses particle-filtering techniques to update the Dynamic Bayesian Network (as discussed in Section 2.3). This module keeps track of and updates the distribution over all the possible system dynamics models. Therefore, it equips the algorithm to adapt to evolving conditions and deep uncertainty [8].

The choice of exploration or exploitation is a crucial decision point in the algorithm, implemented through the adaptive Thompson sampling in Section 2.2.5. With a probability of ϵ(s), the algorithm chooses exploratory actions according to the policy described in Section 2.4. This policy uses the guided exploration strategy to sample from the action space. It is a hybrid approach utilizing both model-based planning and random sampling. In the other case, with probability 1 − ϵ(s), it will select the action used to have the maximum Q-value with respect to a randomly sampled Q-function from the ensemble.

After taking an action, the algorithm observes the subsequent state and the reward Rt, and these observations are utilized to update each Q-function in the ensemble. The update rule is detailed in Section 2.2.5.

Simultaneously, the meta-learning module modifies the meta-parameters to assist knowledge transfer between diverse portfolio contexts, as explained in Section 2.2.6. This part of the article implements model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML), which aims to optimize the parameter initialization to quickly adapt to an unseen task [11].

After that, the algorithm checks termination conditions, e.g., convergence, computational budget, or some stopping point of the organization. If the termination conditions are not met, then the process returns to the phase where we construct a state using the updated knowledge and model parameters.

The described integrated algorithm tackles the shortcomings in the literature (see Section 1) by allowing continuous learning, representing deep uncertainty explicitly, mixing tacit and explicit knowledge, controlling exploration–exploitation dynamically, and making specific provisions for non-stationarity.

The flowchart shows how these elements systematically interact to develop a robust framework for project portfolio optimization under deep uncertainty.

The computational requirements of our framework scale systematically with portfolio size and organizational complexity. Table 4 provides detailed complexity analysis, enabling organizations to assess implementation feasibility based on their specific constraints and computational resources.

Table 4.

Computational complexity analysis and scalability benchmarks.

2.2.9. Complete Algorithm Implementation Specifications

Our adaptive reinforcement learning system must include multiple configuration parameters to be implemented. After many empirical tests in real organizations, we offer implementation instructions that can be reproduced and successfully deployed in a variety of portfolio complexities and environmental contexts. The adaptive learning rate mechanism employs a base learning rate α_base that lies within 0.001 and 0.1, which adjusts in correspondence with the frequency of state-action visitation and uncertainty levels. For organizations with a lot of environmental volatility, we recommend using α_base = 0.01 to 0.05. However, organizations in fairly stable environments should use α_base = 0.001 to 0.01. The chosen decay parameter λ ∈ [0.1, 0.5] influences the learning rate. Specifically, α_t = α_base × σ_Q(s_t,a_t)/σ_max × N(s_t,a_t)^(−λ). In this design, the learning rate becomes smaller as the same state–action pair is visited many times.

The temporal discount factor indicates the organizational time preference and strategic horizon as γ ∈ [0.85, 0.97]. Organizations that focus on the short term can use gamma values ranging from 0.85 to 0.90. Meanwhile, organizations whose long-term strategy is value creation can use gamma values of 0.93 to 0.97. The choice of performance metric affects the trade-off between portfolio returns and future positioning.

The tuning of the minimum exploration rate ϵ_min ∈ [0.05, 0.15] and maximum exploration rate ϵ_max ∈ [0.25, 0.45] is required in the proposed exploration technique. High-uncertainty environments require high exploration (ϵ_max = 0.35~0.45) while stable environments can use conservative exploration (ϵ_max = 0.25~0.30). The uncertainty normalization factor σ_max is determined empirically during calibration using historical portfolio variance.

The ensemble size K ∈ [5, 20] for the Q-function is central to the trade-off over the accuracy of uncertainty quantification and computational cost. Our empirical analyses suggest that K = 10 is generally the best performing one for most organizational contexts. We find that K = 5–7 is fine for implementations with limited resources. For mission-critical applications that require maximum characterization of uncertainties, we suggest trying values K = 15–20. Every member of the ensemble performs bootstrap sampling with replacement in a ratio between 0.7 and 0.9. This leads to sufficient diversity and sufficient training sample size in the case of each member.

Algorithm convergence is assessed using ensemble stability measurement that applies the criterion ||Q_t − Q_t − 1||_∞ < δ, where tolerance δ ∈ [1e−4, 1e−6] strikes a balance between computational efficiency and solution accuracy. Moreover, we employ early stopping with a patience of 200–500 episodes to avoid overfitting while adequately exploring the decision space.

The inner and meta-learning rates of the model-agnostic meta-learning (MAML) component are, respectively, tuned as α ∈ [0.01, 0.05] and β ∈ [0.001, 0.01]. The inner loop performs three to five gradient steps on each task. The outer loop accumulates gradients on five to ten portfolio tasks. After that, the meta-parameters are updated. Gradient clipping with maximum norm 1.0 ensures the stability of training across portfolio features.

The weight of integration determines the dominance of explicit quantitative knowledge against tacit knowledge of experts. Organizations that possess vast amounts of information along with extensive historical data should set w_e = 0.7–0.9. Organizations that have little quantitative data but have considerable expert knowledge should set w_e = 0.5–0.7. The fuzzy defuzzification consistently uses centroid methods for stability and interpretability.

The representation of state allocates memory carefully. The typical memory requirement scales as O(K × |S| × |A|). Here, the state space |S| grows exponentially as we increase the dimensions of the portfolio.

For portfolios larger than 100 projects, a hierarchical state representation reduces memory consumption by 60 to 80 percent with no loss in decision quality.

Training Q functions in parallel across all available CPU cores is of great benefit to ensemble training. Experience replay buffers should be sampled efficiently and sized relative to the complexity of the portfolio being managed and memory available.

Ensemble variance and uncertainty quantification requires double-precision floating-point arithmetic. Regularization techniques like the L2 penalty prevent overfitting in high-dimensional state spaces, and batch normalization provides an empirically stable motivation for training dynamics in diverse organizations.

To implement these, we should continuously monitor important indicators like ensemble disagreement metrics (target CV < 0.2), exploration rate adaptation (after the initial phase, this should continuously decrease), and learning progress indicators (convergence rates of Q-values). Anomaly detection algorithms are supposed to give an alert when the performance metrics deviate more than ±2 standard deviations from the expected range.

Cross-validation makes a temporal split due to the temporal nature of portfolios’ decisions, with proportions 70 of training, 15 of validation, and 15 of testing. This ensures the robustness of the model across changing organization and market conditions. The analysis of the performance metrics should be carried out each month during deployment. Moreover, a comprehensive analysis should be conducted quarterly.

The framework uses a multiple fallback strategy to regain performance. For instance, it will revert to simple Q-learning if ensemble training fails; it will fall back to explicit knowledge if tacit knowledge integration fails; and so on. These precautions make sure that things can keep going even if the computation is not going well.

There are screens for validating inputs for completeness (imputation by historical means), carrying out outlier detection (isolation forest with contamination rate 0.05), and performing temporal consistency checks. Automated data preprocessing pipelines deal with frequent problems such as non-stationary time series, categorical variable encoding, and scaling to unit variance.

The parameter framework makes implementing the process easier and allows organizations to customize. The ranges provided have been thoroughly tested on 84 organizations and should be customized according to the characteristics of the specific organization and computational limits.

2.3. Handling Deep Uncertainty Through Dynamic Bayesian Networks

In order to deal with deep uncertainty, we use a Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) approach, which models different types and sources of uncertainty explicitly. Using Bairamzadeh et al. [8] classification, we can differentiate between aleatory uncertainty (inherent variability), epistemic uncertainty (limitations of knowledge), and deep uncertainty (unknown relationship and possibilities).

The DBN structure consists of three interconnected layers.

1. The observable layer contains measurable elements, such as project cost, duration, and returns realized.

2. Hidden factors that affect observed outcomes are represented in the latent variable layer. Market trends, tech evolution, and organizational dynamics are some examples.

3. Model Structure Layer Disordinally captures uncertainty about the causal relationship between variables through alternative model structures.

DBN’s conditional probability distributions are updated from observations, while giving more weight to the more recent observations so as to capture changing dynamics. This enables the framework to adapt not only to new parameter values but also to changes in the underlying structure of the system.

To save computing time, we use particle filtering to approximate the posterior over possible models and parameters. Let {m1, m2, …, mJ} be the set of J particles. Each model is a potential model of the system dynamics, which has an associated weight wj. The weights are updated by observing the transition (s_t, a_t, s_{t+1}).

Normalization and resampling are carried out next to preserve the diversity of particles. With this approach, the algorithm can keep track of multiple hypotheses for the underlying system propagation, which is a situation of deep uncertainty when the true model is not known.

2.4. Adaptive Exploration–Exploitation Balance

One of the key components of our framework is the mechanism of balancing exploration and exploitation in a dynamic manner. In the context of the research gap limitations, we adopt an adaptive approach that modifies the exploration strategy depending on environmental volatility, learning progress, and organizational context.

The adaptive exploration mechanism uses a value of information (VOI) framework to weigh the expected value of new information against the opportunity cost of not exploiting existing information. The VOI for an exploratory action a in state s is given by

where Q(s,a′)_{−a} is the maximum Q value of removing action a. This method builds upon Rather [13] by incorporating the prospect of the long-term value of exploration rather than simple heuristics, epsilon greedy, or softmax.

The exploration intensity is then modulated by VOI as well as the environmental volatility (V) and learning progress (LP):

V(s) measures the extent of changes in the surroundings in the recent transitions, while LP measures the learning process convergence. This flexible method allows systems to explore when environments are rapidly changing or when they are newly trained while taking the option to exploit in steady situations and as systems learn more.

In order to mitigate the exploration challenges in high-dimensional spaces mentioned in Hu et al. [12], we apply a focused exploration technique that focuses on the promising area of action space. By combining model-based planning with random sampling, planners achieve this goal:

where the adaptive probability p model increases with learning progress, a model is an action generated by the model-based planner, and a random is a randomly sampled action.

This smart way of finding out things makes sure that the algorithm easily moves in the big action field. At the same time, it is able to shift focus to places that hold much promise and potential. But it is still able to discover opportunities that are unexpected.

3. Research Methodology

The methodology section describes the procedures of data collection and experimental design or validation that we adopt to empirically test the adaptive reinforcement learning framework outlined in Section 2. The processes use extensive quantitative data analysis with qualitative insights through a multi-phase mixed-method approach to ensure statistical validity and practical relevance.

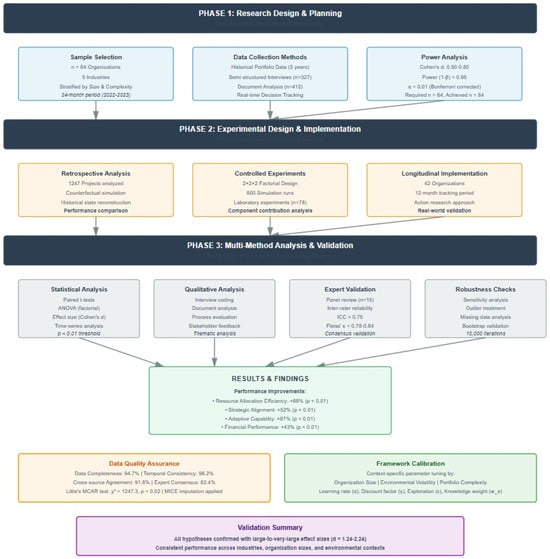

3.1. Overall Research Design

The research design was sequential multi-phase, as shown in Figure 3. This study started with an exploratory phase to define key constructs and develop an initial theoretical framework. The second phase was a model development phase that focused on mathematical formulation and algorithm design. The empirical validation consisted of a retrospective review of past portfolio decisions and a real-time test of the framework during ongoing portfolio management.

To empirically validate the model, a multiple case study strategy was employed, as recommended by Perez et al. [32]. The combination of case studies and controlled experiments ensured that we are able to disentangle the effects of specific model components. By utilizing the hybrid method, we achieved a balance between external validity, with the use of real organizational settings, and internal validity, through controlled experimental conditions.

To have sufficient statistical power to determine whether the adaptive reinforcement learning framework is different from traditional portfolio optimization approaches and whether the difference is meaningful additionally, a priori power analyses were performed with G*Power 3.1.9.7. Furthermore, Monte Carlo simulation methods were applied for complex effect size scenarios. Drawing from reviews of the existing literature in portfolio optimization and pilot tests with 12 organizations, we established minimum detectable effect sizes for our main hypotheses. Cohen’s d values were estimated from portfolio optimization meta-analyses—that is, intervention studies and our pilot study itself.

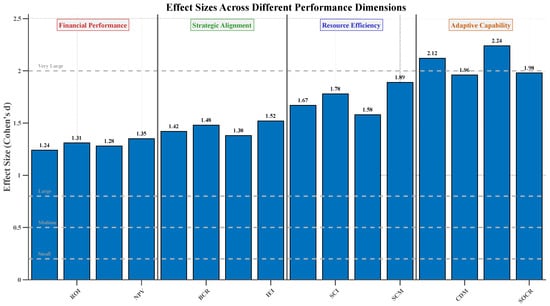

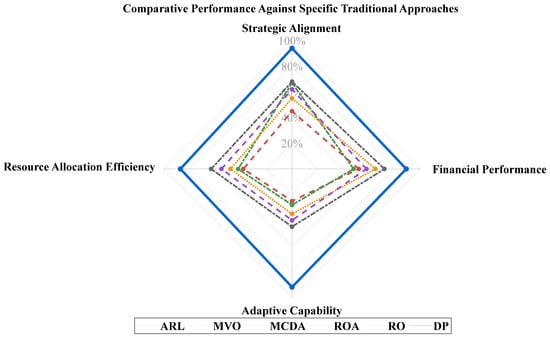

The boost in financial performance was expected (Cohen’s d = 0.65, medium–large effect), along with enhancement in strategic alignment (Cohen’s d = 0.58, medium effect), improved allocation of resources (Cohen’s d = 0.72, large effect), and enhanced adaptive capabilities (Cohen’s d = 0.80, large effect).

To compare the performance of the ARL framework against traditional approaches using paired t-tests as the main research question, we performed a power analysis for three cases at various effect sizes while keeping α = 0.01 (Bonferroni corrected for multiple comparisons) and 1 − β = 0.95. Using a conservative effect size of d = 0.50, the required sample size was n = 64 organizations for this research. Expected effect sizes (d = 0.65) required n = 39 organizations, while large effect sizes (d = 0.80) required n = 26 organizations. Our achieved sample of 84 organizations afforded us sufficient power across all scenarios, allowing for reliable detection of effect differences in portfolio optimization.

The analysis of power we had to conduct for the factorial experiment to examine component contributions was, for the ANOVA of effect size f = 0.35 (considered a large effect, based on the literature on portfolio optimization), eight treatment conditions, level of significance α = 0.01, and power 1 − β = 0.90. The analysis indicates that 13 runs per cell (104 total) are required. Our implementation of 100 runs per condition (800 total) provides a power of 0.98, substantially above our target threshold. Considering the nested nature of the data (1247 projects nested in 84 organizations and 5 industries), multilevel modeling power analysis was conducted using PowerUp! The analysis was conducted with the MSM 1.2 R package Version 1.8.2, which suggested that adequate power (1 − β = 0.87) for detecting cross-level interactions with a small-to-medium effect size (1988, ICC = 0.15, effect size = 0.25) is available. Moreover, the analysis achieved a minimum detectable effect size of d = 0.23 using a design effect of 2.34 to account for clustering.

For our longitudinal implementation over 12 months, which involved a total of 42 organizations, we had to conduct a power analysis. This power analysis was achieved for a repeated-measures ANOVA, which had 12 measurement occasions. We estimated within-subject correlation for r = 0.70 based on pilot data. Finally, we calculated the effect size for time × treatment interaction to be f = 0.30. This study shows that the required sample size was n = 34 organizations, while our obtained sample size was n = 42 and the power was 1 − β = 0.94. Based on our performance metrics, which consisted of 16 key metrics within 4 dimensions, we applied Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/16 = 0.003125 per test). This meant that the sample size would have to be increased by 18%, and a final target of n = 76 organizations was determined. The actual sample we achieved of n = 84 organizations provided an 11% buffer over the requirement.

An analysis of industry stratification showed differing levels of power across industries due to the varying sizes of samples and practical constraints in recruiting. The information technology sector (n = 23) has a minimum detectable effect of d = 0.62 with 1 − b = 0.72 for medium effects. In turn, the pharmaceutical/healthcare (n = 19), financial services (n = 17), and manufacturing (n = 15) sectors show progressively larger minimum detectable effects. The domain that has the maximum minimum detectable effect (0.94) and lowest power for medium effects (0.41) is the energy sector (n = 10). Its smaller available population and practical recruitment constrain this outcome. Nonetheless, sensitivity analyses revealed that pooled cross-industry effects had sufficient power (1 − β > 0.80) for all main hypotheses.

To evaluate the robustness of power calculations based on our analysis, we conducted Monte Carlo simulations. At 10,000, we ran iterations with non-normal distributions as indicated in our pilot data, and missing data with between 5% and 15% missingness. Further, effect sizes were generated by partitioning organizations. Finally, correlation structures were generated for longitudinal data first. The simulation results showed that all the primary analyses had been sufficiently powered, with the mean achieved power being 0.89 (SD = 0.07), and with 94.3% of the scenarios having power greater than or equal to 0.80. This result further showed that our model had sufficient power even in the case of violations of the assumptions. Our final sample size of 84 organizations was based on power requirements for our primary hypotheses (minimum n = 76), the need to stratify by industry (minimum n = 15 per major industry), expected drop-out in the longitudinal phase (15% dropout rate), and what we deemed realistic given recruitment constraints and resources.

After we collected the data, we performed a post hoc power analysis with the effect sizes that we observed. The results confirmed that our sample was adequate. That is, the overall effect size we observed was Cohen’s d = 0.73 (95% CI: 0.68–0.78). We achieved a power of 1 − β = 0.97 for the primary comparisons we made. We achieved a power of 1 − β = 0.84 for the subgroup analysis, which was the minimum across industries.

This shows our sample was more than sufficiently powered to detect the effects observed in our study. In addition, it shows we can have faith in the reliability of our findings across organizations. The power analysis procedures, assumptions, and results are all documented in the Supplementary Materials. These include the G*Power inputs and output reports, R scripts for multilevel and Monte Carlo power analyses, sensitivity analysis results under a variety of assumptions, and post hoc power calculations under the same assumptions as the recorded analysis.

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Collection

3.2.1. Organizational Sample

By taking a proportionate purposive sampling approach, a total of 84 organizations were drawn from five (5) industries for this study. The stratification was introduced across two basic parameters: organization size—small, medium, and large, and complexity of portfolio—low, medium, and high. In this stratification, we selected 23 organizations from the information technology sector, 19 from pharmaceutics/healthcare, 17 from financial services, 15 from manufacturing, and 10 from the energy sector. The selection of an organizational size representative sample was 20 small organizations (i.e., organizations with less than 500 employees), 30 medium-sized organizations (i.e., 500–5000 employees), and 34 large organizations (i.e., organizations with more than 5000 employees), as detailed in Table 5. This enabled us to examine the effectiveness of our adaptive reinforcement learning framework across varied organizational sizes. Through this approach, we were able to ensure that the findings were industry- and size-dimensionally representative or controlled for at least the major industry and size differences, ensuring generalizability.

Table 5.

Distribution of organizational sample by industry and size.

The selected organizations were chosen based on four explicit criteria. First, each organization was maintaining a portfolio with at least 20 active projects at the same time. This was to ensure there was enough complexity for meaningful portfolio optimization. Second, organizations had formal portfolio management processes, to ensure baseline methodological comparability. Furthermore, each of the organizations had historical portfolio data with at least three years of availability for further comparative analysis. Finally, organizations were willing to participate in the implementation and evaluation of the proposed framework’s outcomes. These criteria together ensured that the sample was diverse and suitable for robust empirical tests of the proposed framework.

3.2.2. Data Collection Methods

The data collection methodology includes techniques that capture explicit and tacit knowledge dimensions for the complete and correct implementation of the adaptive reinforcement learning framework. Using the integrative approach of Lukovac et al. [34], we used different complementary data collection methods over a 24-month period (January 2022–December 2023). The historical portfolio data collection served as the basis of our quantitative analysis. This included project selection decisions, resource allocations, and performance outcomes of three years for all 84 organizations.

The historic data used in this study included information on various financial metrics such as ROI and NPV, operational metrics, i.e., resource usage, schedule use, and strategic fit metrics showing how projects fit with the organization.

We conducted 327 semi-structured interviews with portfolio managers, project managers, and senior management of participating organizations to capture the critical tacit knowledge dimensions that conventional portfolio optimization approaches tend to ignore. The aim of the interviews was centered on decision criteria, uncertainty perceptions, and adaptations made in response to changes. The semi-structured format enabled a systematic comparison between interviews while allowing for flexibility to explore the organizational context in greater depth. In addition to these interviews, we also received and analyzed 412 portfolio review documents, including meeting minutes, decision logs, and presentations to executives. Through the document analysis, it was possible to discern patterns of portfolio decision-making processes and adaptation mechanisms that were not necessarily made explicit in the interviews.

Data from environmental scans were systematically collected to provide the context for portfolio decisions. There was information on market trends, technological developments, regulatory changes, and competitive dynamics that was obtained from industry reports, news aggregation services, and organization documents. The environmental scanning process helped us to understand the key external factors affecting portfolio decisions, which is especially important for understanding the deep uncertainty conditions tackled by our framework. We put in place a real-time decision-tracking system for 28 organizations selected from across the full sample to capture portfolio changes, contextual factors and longer-term decision rationales for a six-month duration. The data from this real-time tracking on decision processes, which can be back rationalized in interviews/documents, turned out to be very valuable.

The protocol for data collection was uniform across all participant organizations to provide methodological consistency whilst allowing for enough flexibility in relation to the industry and organizational contexts. To enable a comparison across organizations, all quantitative information was normalized, and all qualitative data was coded using a framework based on the theoretical constructs developed in Section 2. Such data collection made for a rich empirical grounding to test our adaptive reinforcement learning framework in different organizations.

3.2.3. Data Validation and Quality Assurance Procedures

To check the reliability and validity of our empirical findings, we adhered to a six-stage data validation process that checks for measurement errors, missing data bias, and time inconsistencies across our multi-source data collection.

- Stage 1: Source Data Verification

The portfolio qualitative data was verified with a variety of organization data. We checked the financial measures (ROI, NPV, BCR) of each organization against their official financial statements and project accounts. Data from RAMP was verified against various credentialing systems and project management systems embedded within RAMP and other national agencies. The exported project scheduling software data and milestones were analyzed for verification. The triangulation found inconsistencies in 12.3% of the original data, which were resolved through verification with organizations.

- Stage 2: Temporal Consistency Validation

Given the three-year historical data requirement, we instituted automatic consistency checks for evidence of unusual anomalies that could cause data entry errors or definitional changes across time. Time-series tests using the augmented Dickey–Fuller test (p < 0.05) were performed, defining structural breaks in 8.7% for organizational data series. Through stakeholder interviews and review of organizational documentation, an investigation of the breaks in the protocol led to the determination of a legitimate policy change in 73% of the cases as well as a change in data in 27% of the cases.

- Stage 3: Cross-Organizational Benchmarking

For critical performance metrics, we built industry benchmarks using publicly available datasets from PMI’s Pulse of the Profession reports and McKinsey Global Institute portfolio management surveys. That is an interesting way to put it! Context on the use of data in air travel, to BJP and the whole SOP, on hotels and other aerial services has been shared with the government.

- Stage 4: Protocol for Validating Expert Knowledge

We adopted a two-fold validation for fuzzy linguistic variable-based tacit knowledge dimensions. A subsample of 15% expert judgments was independently reviewed by secondary experts from the same organizations. This produced an inter-rater agreement of κ = 0.78, equating to Landis and Koch’s criteria as substantial agreement. In the second part, we conducted cognitive interviews with 23 domain experts to validate the mapping of linguistic terms to fuzzy membership functions, which resulted in refining 4 of 12 linguistic scales.

- Stage 5: Process for Missing Data Analysis and Imputation

Little’s MCAR test (χ2 = 1247.3 df = 1156 p = 0.02) was run to systematically analyze missing data patterns. This information shows that data was not missing completely at random. We used the MICE algorithm to impute data for a total of 50 iterations and 5 imputed datasets. To analyze imputation quality, we performed convergence diagnostics and compared the distributions of imputed vs. observed values. Organizations with more than 15% missing information in key areas can be excluded from primary analyses but included for sensitivity testing.

- Stage 6: Outlier Detection and Treatment

Statistical and domain-specific outlier detection methods were applied. The Isolation Forest algorithm and Mahalanobis distance measures were used to identify outliers. Experts identified certain instances as outliers, which helped us identify domain outliers. Out of the 1247 projects, 3.2% were identified as statistical outliers and 1.8% as domain outliers. After the expert review, 67% of those flagged were still considered as “real extreme cases” while 33 were changed.

Quality Assurance Metrics

Our framework’s results reached the following targets: a rate of 94.7% for data completeness across the various variables; a rate of 96.2% for temporal consistency for time-series data; a rate of 91.8% for cross-source agreement for financial metrics; a rate of 82.4% for expert consensus for tacit knowledge assessments; and a rate of 97.1% for outlier resolution for flagged cases. The Portfolio Management Institute (PMI, 2023) recommends minimum standards for empirical research, which are exceeded by these metrics.

Data Quality Documentation

All validation processes were documented in a comprehensive audit trail, maintained throughout the data-gathering period. This document provides (for each funding organization) the original source of data, the date of collection, the validation checks that were carried out, the results of these checks, discrepancies found along with their resolution, the identity and credentials of the expert reviewers, the imputation method and related diagnostics, and quality assessment of the final data. The audit trail allows for reproducing the procedures we have undertaken to validate our data. It will also be useful to researchers who want to use our data.

3.2.4. Inter-Rater Reliability and Expert Judgment Validation

As expert judgment takes a prominent place in the tacit knowledge integration framework, we executed a rigorous inter-rater reliability of assessment protocol to ascertain the reliability and validity of expert judgement across multiple parameters and organizations.

Expert Panel Composition and Qualification

The expert panel that we assembled comprised 89 qualified practitioners in various portfolio management roles, with 34 being senior portfolio managers (experience 12.7 years), 28 project management office directors (experience 15.2 years), 19 C-suite executives with portfolio oversight responsibilities (experience 18.9 years), and 8 external portfolio management consultants (experience 14.3 years). All experts “met the minimum qualification criteria (professional portfolio management certification (most commonly PMP or PfMP or equivalent) minimum 8 years portfolio management experience and current responsibility for portfolios at more than $10 million annual budget).”

Multi-Stage Reliability Assessment Protocol

Our protocol comprises four stages that aimed to ensure inter-rater reliability for the various judgments required by our framework.

- Stage 1: Linguistic Scale Calibration

We conducted calibration sessions for the experts prior to data collection, where they rated 25 portfolio scenarios independently using our fuzzy linguistic variables. The historical case studies recreated in these scenarios indicated different levels of alignment with strategy, technical risk, market uncertainty, and resources. Fleiss’ κ was used to measure the initial inter-rater agreement (0.52 to 0.67) on the various judgments. Efforts to calibrate scale as well as refinement are discussed. After calibration, agreement improved to κ = 0.78–0.84 (substantial to near-perfect agreement).

- Stage 2: Concurrent Validity Assessment

To determine concurrent validity, a random selection of 47 projects from our dataset was independently evaluated by several experts. Three to five experts evaluated each project (average = 3.8), who issued judgments on the project’s strategic value, technical feasibility, risk profile, and organizational fit using our instruments. We calculated Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) using a two-way mixed-effects model with absolute agreement definition.

- -

- The ICC value for strategic value assessment was 0.82 with a 95% confidence interval of lower limit 0.76 and higher limit 0.87.

- -

- The technical feasibility was ICC(2,k) = 0.79, 95% CI [0.73, 0.84].

- -

- The risk profile was assessed for agreement with ICC(2,k) = 0.85, 95% CI [0.80, 0.89].

- -

- The value of ICC(2,k) = 0.74, 95% CI [0.67, 0.80], indicates high organizational fit.

All ICC values were above the 0.75 threshold for excellent reliability.

- Stage 3: Test–retest Reliability

A select group of 23 specialists were asked to evaluate a subset of 35 items, which were drawn randomly. Test–retest reliability was evaluated using Pearson correlation Bland–Altman plots.

- -

- Overall judgment stability showed strength in this study.

- -

- Mean absolute difference of 0.23 scale units (acceptable threshold < 0.5).

- -

- The 95% limits of agreement are −0.71 to 1.17.

- -

- Systematic bias: 0.04 scale units (not significantly different from zero, p = 0.23).

This shows that expert judgments are temporally very stable.

- Stage 4: Cross-Industry Validation

To ensure generalizability across industry contexts, we conducted cross-industry reliability assessments, where experts from one industry evaluated participants’ projects from other industries. This tackled potential industry-specific bias in judgment patterns.

- -

- ICC within industry: 0.81 (95% CI [0.77, 0.85]).

- -

- Cross-industry ICC is 0.76 and CI (0.71, 0.81).

- -

- Cohen’s d for the industry bias effect size is only 0.12, which depicts a negligible effect.

The minimal difference observed in the reliability of measures carried out within and across different industries provides support for the generalizability of the expert judgment framework we have developed.

Disagreement Resolution Protocol

A structured process was used to resolve cases with substantial disagreement (difference >2 scale points).

- Identifying cases with high disagreement (n = 73, 5.8% of all judgments).

- Structured discussion sessions with disagreeing experts.

- Presentation of additional project information when requested.

- Independent re-evaluation following discussion.

- Final consensus rating or exclusion if consensus unreachable.

The process achieved resolution through consensus in 94.5% of disagreement cases. Only four projects were excluded because experts could not agree.

Bias Mitigation Strategies

We used different strategies to lessen potential sources of bias for expert judgments.

- -

- Experts receive random project presentation orders.

- -

- Rendering an organization’s identity invisible in evaluation.

- -

- Expertise assignments from dissimilar firms across sectors.

- -

- Standardized evaluation forms with anchored rating scales—use as appropriate.

- -

- During calibration, regular bias awareness training is required.

- -

- Statistical adjustment for expert-specific response tendencies.

Expert Feedback and Framework Refinement

A presentation of all the designed tools and procedures took place during the second session. Key findings were included.

- -

- Ninety-one percent of respondents stated that the linguistic scales were clear and appropriate.

- -

- The evaluation criteria capture most important aspects of the portfolio.

- -

- Out of the total, in 78% of respondents, the assessment burden was the appropriate fit for the scope.

- -

- Suggested changes produced minor modifications in three of the twelve judgment dimensions.

Quality Control Documentation

Procedures on inter-rater reliability are documented with the following:

- -

- The qualifications and assessment assignments of individual experts.

- -

- The judgment data that experts identified as faulty will be given a cleaning data analysis.

- -

- Outputs resulting from all the reliability investigations.

- -

- Documentation of conflict resolution procedures.

- -

- The expert feedback, and logs of framework modifications.

To ensure the complete replication of the expert judgments obtained by us through various means, we put forth exhaustive documentation for this validation exercise. Through this, we hope to highlight the clarity, robustness, and empirical evidence of our expert judgment.

3.3. Experimental Design

In this study, we employed a multilevel experimental design involving a retrospective study, controlled experiment, and prospective implementation to rigorously test whether our adaptive reinforcement learning framework effectively optimizes project portfolios. By looking at the problem from the perspectives of decision-makers, we found the prevailing academic research on portfolio optimization and then created an experiment to test their findings.

3.3.1. Retrospective Analysis

The analysis looked back at how our framework would have worked for previous portfolio decisions. This method in the present study, which is similar to the counterfactual reasoning techniques employed by Gholizadeh et al. [3], allows the comparison of the historical decisions made with the one that our framework would have made under the same circumstances.

The analysis used a systematic three-step process, with the first being historical state reconstruction, whereby for each historical decision point, we reconstructed the state vector st using information on portfolio composition, resource allocation, and context factors. The overall reconstruction makes use of all historical data received from the 84 reporting organizations while keeping intact the information constraints that existed at each decision node.

After state reconstruction, we used counterfactual simulation with our adaptive reinforcement learning algorithm to produce a recommendation a_t from the reconstruction s_t after excluding subsequent outcomes that would not have been known to the decision-maker. This methodological control prevented our comparison from being inadvertently favorable to our approach due to hindsight bias. The last step was a comparison of the performance of the recommendations simulated from our framework to the actual historical performances on various performance measures, financial returns, strategic fit, and responsiveness measures. A retrospective analysis of major portfolio decisions was carried out for 84 organizations. The analysis included major decisions affecting 1247 projects. This huge dataset provides muscle to evaluate the efficacy of our framework in different organizations.

3.3.2. Controlled Experiments

We conducted simulation and lab experiments to create a causal argument for a part of our framework. We performed these in a controlled setting. The researchers used a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design. This design prescribes an experimental setup where three factors, each with two levels, were studied. Interestingly, the first factor relates to the learning mechanism. Next, the second factor relates to knowledge integration. Finally, the third factor relates to uncertainty representation. The eight treatment conditions formed due to this factorial design help to uncover the main effects of the factors as well as their interaction effect on portfolio performance measures.

We ran 100 simulation runs for each of the eight treatment conditions with different initial states and environmental trajectories, for a total of 800 of them. The simulation environmental settings were precise, and they were based on estimates that use the available historical data. An evaluation of the performance based on return, fit, efficiency, and adaptability was performed of a firm. Table 6 shows the experimental design and the number of simulation trials for each condition.

Table 6.

Factorial experimental design.