Featured Application

The research presented in this article demonstrates an important and effective potential for field application of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium in sugar beet crops against Heterodera schachtii, as well as a possible application in other crops, where nematodes are significant pests.

Abstract

Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) is the world’s second most important source of sugar, yet its production is seriously threatened by the beet cyst nematode Heterodera schachtii. Managing this pest remains a major challenge, especially where the use of chemical nematicides is limited or prohibited, highlighting the need for sustainable biological alternatives. This study evaluated the edible fungus Pleurotus ostreatus as a potential biocontrol agent against H. schachtii. Several offspring strains derived from a wild parental isolate (Po4) were tested in both pot and field experiments. In pot trials, mycelial application to fallow soil reduced nematode populations by 46.9–71.3%, while in soils cultivated with sugar beet, reductions of 26.2–32.5% were observed. Field experiments conducted over two consecutive years confirmed the nematode-suppressive activity of the Po4 strain, with population decreases of approximately 45–48% in fallow soil and 7–21% in sugar beet plots, whereas control plots exhibited 2–3-fold increases. These consistent trends indicate that P. ostreatus mycelium effectively limits nematode proliferation under both controlled and field conditions. The findings demonstrate the potential of P. ostreatus as an environmentally sound and practical component of integrated pest management systems, offering sugar beet producers and breeding programs a novel biological approach to sustainable nematode control.

1. Introduction

Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) is one of the most important crops in Europe and ranks second among sugar-producing crops worldwide [1]. Its production can be severely affected by various pathogens and pests, among which Heterodera schachtii is one of the most significant threats to sugar beet cultivation [2,3]. In many countries, including Poland, the control of this nematode is restricted primarily to biological methods. In Poland, only two chemical substances are officially registered for nematode control, including H. schachtii, and their use is limited to table beet crops, not to sugar beet cultivation.

The most widely used agricultural strategies to manage this group of pests belong to the framework of integrated pest management and plant protection. Among them, crop rotation, the cultivation of nematode-tolerant sugar beet varieties, and the use of nematocidal plants are the most common practices [3]. Therefore, the search for practical and effective methods to control the sugar beet cyst nematode remains an urgent and important research goal [3].

Pleurotus ostreatus, commonly known as the oyster mushroom, is well known for its nematocidal properties [2]. This phenomenon was first documented by Barron and colleagues at the University of Guelph during the 1980s [4]. The vegetative mycelium of P. ostreatus produces specialized hyphal structures, or knobs, that release droplets containing substances capable of paralyzing nematodes. Since this discovery, several studies have investigated the nematocidal potential of Pleurotus spp. mycelia; however, a comprehensive field-application method has not yet been developed [2,5,6].

P. ostreatus is one of the most widely cultivated edible mushrooms worldwide. Shortly after the discovery of its nematocidal properties, the compound responsible for this activity was identified as (E)-2-decenedioic acid, a ten-carbon dicarboxylic compound [6,7]. Subsequent studies, however, have suggested that this substance is not the sole contributor to the nematocidal activity of Pleurotus species [8,9]. In 2023, Lee et al. [10] identified another compound, 3-octanone, as a key factor responsible for nematode paralysis, although it is commonly found in fungi and known for its characteristic mushroom aroma [11,12]. The identification of 3-octanone helps explain why some studies have reported nematocidal effects even when only parts of the mushroom fruiting bodies were used [8,13].

In our study, we aimed to evaluate the potential of vegetative P. ostreatus mycelium for controlling the cyst nematode H. schachtii under field conditions, in the context of sugar beet breeding. During breeding activities, sugar beets are often sown repeatedly on the same plots, which leads to increased soil infestation with H. schachtii. In our experiments, we compared the effects of mycelium application in fallowed soil with those in soil sown and cultivated with sugar beet. The two-year experiments were conducted on soil heavily infested with this phytopathogenic nematode, providing an opportunity to test the P. ostreatus mycelium selected in previous laboratory experiments [14,15] and to evaluate its field application method.

To date, the use of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium for the protection of sugar beet against Heterodera schachtii has not been evaluated under field conditions in Poland or elsewhere in Europe. The results of this research may contribute to the development of a simple, cost-effective method for “cleaning” infested plots in sugar beet breeding farms, where soils are often contaminated with H. schachtii due to frequent monoculture cultivation. Furthermore, this study supports the development of environmentally friendly, biologically based methods for controlling cyst nematodes, offering potential applications in sustainable agriculture.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Organisms

Plants. Nematode-susceptible sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L. subsp. vulgaris) varieties were employed in the experiments. In the pot experiment, a variety, Fantazja, was applied, and in the field experiment, cv. Janetka, was applied. Both cultivars were kindly delivered by Kutnowska Hodowla Buraka Cukrowego (Kutnowska Sugar Beet Breeding Company, Kutno, Poland).

Mycelia of Pleurotus ostreatus, a wild strain designated Po4, and its progeny, homokaryotic (Po4-8, Po4-30) and heterokaryotic (Po4-3dix17, Po4-14x17, Po4-2dix1) crosses, were chosen for laboratory and field experiments. Based on the results of previous tests, Po4 strain was selected as a model mycelium for field experiments [14,15]. The strains were initially cultured on PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) medium. Upon complete colonization of the plate surface, autoclaved barley grains were inoculated with the mycelium and incubated until complete grain colonization was achieved.

The population of Heterodera schachtii was determined according to the methodology described by Kaczorowski [16]. Before conducting the basic procedure, soil samples (100 ± 0.1g) were dried at room temperature and sieved through a 2 mm sieve to remove any straw residues and then extracted by the Seinhorst apparatus—a method using water–soil suspension and separating the organic and inorganic fractions based on their weight and ability to float on the water surface. The extraction of cysts was performed at an ambient temperature of 20 °C for 8 min, at a flow rate of 1.6 dm3/min. Cysts obtained in this procedure were isolated from smaller organic particles by a dissecting needle under binoculars (ProLab Scientific Motic SMZ160 Binocular) and then transferred to a microscope slide, crushed with a metal spatula in a drop of distilled water to obtain a suspension of nematode eggs and larvae J1, and counted under the microscope (Nikon Eclipse E200 + Delta Optical 1080 camera; magnification 40×). The same procedure of assessing the H. schachtii population was used at the beginning (Pi) and at the end of the experiments (Pf), both in the field and pot experiments. In the field experiment, soil samples used for the assessment of population size were prepared in four replications. For each replicate sample, two independent population size analyses were conducted. Each replicate was prepared from a combined, homogenized sample composed of subsamples collected from a depth of 0–30 cm, from nine locations arranged in an X-shaped pattern within each experimental plot. In the laboratory experiment, three replication samples were estimated.

Based on the obtained results, the percentage of decrease/increase in the number of H. schachtii eggs and larvae was calculated according to Formula (1):

Percentage decrease/increase [%] = (Pf/Pi) × 100 − 100 [%]

2.2. Laboratory Pot Experiments

Laboratory pot experiments were conducted in a cultivation chamber. Plastic pots with a capacity of 1 dm3 (dimensions 11 × 11 cm) were filled with an approximately 7 cm layer of luvisol soil (according to FAO classification) naturally inhabited by Heterodera schachtii (Table 1 and Table 2). A layer of autoclaved barley straw was introduced on the soil surface in each pot. Then, thirty barley grains, overgrown with appropriate mycelium, were placed on the straw layer in each pot. The straw layers were covered with the remaining soil. In each pot, six seeds of sugar beet were sown. The pots left without plants served as control ones (black fallow). Pots were incubated for 90 days in a growing chamber at 20 °C and a relative humidity of approximately 65% under artificial lighting with an intensity of 1450 lx. The experiment was performed in three replicates.

Table 1.

Characteristics of soil used in the laboratory experiment.

Table 2.

Initial H. schachtii population density in the laboratory test.

The soil used in the pot experiment was characterized by a neutral pH, average nitrogen and potassium content, and high phosphorus content, with a known initial population of beet cyst nematode (Pi) (Table 2). At the end of the experiment, the soil was removed from pots to determine the H. schachtii population (Pf).

2.3. Field Experiments

Field studies were conducted at the Kutnowska Sugar Beet Breeding company (Kutnowska Hodowla Buraka Cukrowego, Kutno, Poland), on plots organized in tents used for breeding purposes, where the levels of soil nematode contamination had been previously determined (Table 3). The chemical characteristics of the soil are presented in Table 4. The experiments consisted of 4 variants (Table 3) and were conducted on 2 × 2 m plots in partially (both sides) opened cultivation tents, equipped with a pipe irrigation system, and the soil in them was kept moist during the experiments. Variants with black fallow soil were manually weeded if required, thus no plants used to grow there. Temperatures observed during the vegetation periods are given in Table 5. The experiments were conducted in four replications. Soil inoculation with P. ostreatus mycelium (Po4 wild strain) was performed a day before sowing (Table 3). P. ostreatus Po4 strain was introduced as an overgrown straw-composed substrate. The dosage of the straw substrate was established at a dose corresponding to approximately 18 t/ha. The straw-composed substrate bales, weighing approximately 13–14 kg each, were obtained from a commercial mushroom substrate producer (Rusieccy farm, Poland). The straw substrate bales containing Po4 strain were initially crushed by hand and then mixed with soil using a rotary tiller.

Table 3.

Variants of the field experiments and levels of Pi.

Table 4.

Characteristics of soil in the field experiment.

Table 5.

Temperatures during field experiments.

The fresh mass yield of leaves and roots grown in the experiment was determined by measuring the biomass collected from 1 m2 of each experimental plot. Results were converted into per-hectare yields. The expected yield of fresh and dry matter of the aboveground parts and roots was determined (using the drying method). The content of sucrose and molasses-forming substances (K, Na, and N-α-NH2) in the sugar beet pulp was determined using a Venema analyzer, which is used as a standard technology in analyzing sugar beet root quality. Calculations of technological sugar yield were made using Reinefeld’s Formula (2) [17]:

where TPC—technological sugar yield [t/ha]; PK—root yield [t/ha]; %ZC—percentage sugar content (polarization); K, Na, N-α-NH2—content of molasses-forming substances.

TPC = PK/100 [%ZC − 0.012(K + Na) − 0.024·N-α-NH2 − 1.08]

2.4. Data Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. Mean values and standard deviations (SDs) were calculated at a 95% confidence level, and results were expressed as mean ± SD and presented in graphs. Statistical analyses were performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Statistica 13.3 software. Data were compared (p = 0.05) using Duncan’s test. Analyses were performed in two ways: (1) for both years, 2023–24, analyses of all variants of the field test were performed; (2) separately, also for both years, analyses were made for a part including only fallow soils treated and untreated with Po4 strain. This type of analysis was also prepared for laboratory experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Laboratory Experiments

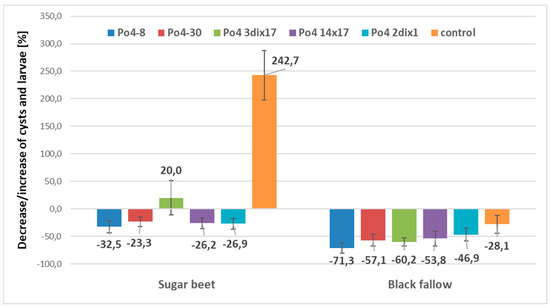

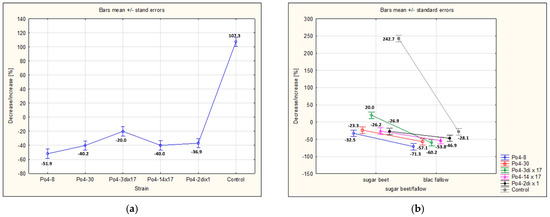

The laboratory experiments demonstrated that some Pleurotus ostreatus mycelia, such as Po4-8, can significantly reduce Heterodera schachtii populations under black fallow conditions (without plants sown), achieving up to a 71.3% reduction in nematode density. This result differed significantly from both control variants (Figure 1 and Figure 2b; Table 6). Other mycelia also reduced H. schachtii populations; however, these reductions were not statistically significant compared with the fallow control. In contrast, all treatments differed significantly from the sugar beet control, in which the cyst nematode population increased by 242.7% within just 90 days of the experiment (Figure 1, Figure 2a,b and Figure 3a) (Table 6).

Figure 1.

Effect of different P. ostreatus strains on H. schachtii population density in laboratory pot experiments. Bars represent the mean percentage change in nematode population ± standard deviation (SD) (3 independent replicates for each strain and condition). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p = 0.05). Negative values represent population reduction; positive values represent population increase relative to initial population.

Figure 2.

Effect of the percentage of decrease and increase in H. schachtii population density in laboratory pot experiments under the influence of the tested strains (a) and the influence of fallow/sugar beet (b). Bars represent the mean percentage change in nematode population ± standard deviation (SD) (3 independent replicates for each strain and condition). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p = 0.05). Negative values represent population reduction; positive values represent population increase relative to initial population.

Table 6.

Results of laboratory pot tests; data were statistically evaluated using two-way analysis of variance at p = 0.05, and the significance level of differences was assessed using Duncan’s test. Data followed by the same letter do not differ significantly.

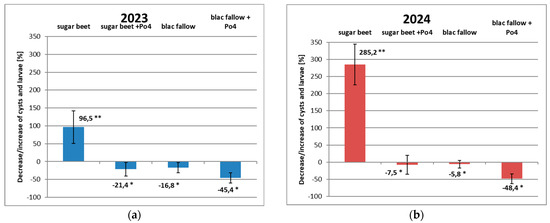

Figure 3.

The influence of P. ostreatus Po4 strain on the percentage decrease/increase in the H. schachtii population in the field experiments; (a) in 2023; (b) in 2024. Bars represent the mean percentage change in nematode population ± standard deviation (SD) (3 independent replicates for each strain and condition). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p = 0.05). Negative values represent population reduction; positive values represent population increase relative to initial population. Data indexed by ** or * do not differ significantly.

In laboratory experiments, tested mycelia, except one, were able to reduce H. schachtii populations in pots containing sown sugar beets. Reductions of 32.5% were observed for the homokaryotic Po4-8 strain and 23.3% for another homokaryon, Po4-30. Two heterokaryotic strains (Po4-14×17 and Po4-2di×1) produced similar reductions of 26.2% and 26.9%, respectively. In contrast, the heterokaryotic strain Po4-3di×17 caused a 20% increase in nematode numbers (Figure 1). However, even this increase was significantly lower than that observed in the sugar beet control (242.7% increase; Figure 1, Table 6). Notably, the Po4-3di×17 strain performed better in black fallow soil, where it reduced the nematode population by 60.2%. In pots with fallowed soils, reductions in H. schachtii populations achieved levels from 71.3% for Po4-8 to 46.9% for Po4-2di×1 strain (Figure 1 and Figure 2a,b). Overall, the mycelia were more effective in fallow soil than in pots where sugar beet plants were grown (Figure 1 and Figure 2a,b, Table 6).

3.2. Field Experiments

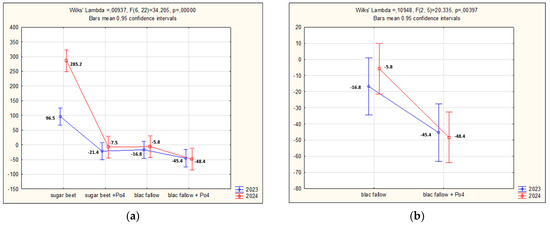

In the field experiment, reductions in H. schachtii population were observed in the case of black fallow + Po4 strain variants, which reached 45.4% in 2023 and 48.4% in 2024. These results were significantly better than those observed in treatments where only sugar beets were cultivated (Table 7). Among the variants, black fallow with mycelium, sugar beet + mycelium, and black fallow, no statistically significant differences were found; however, the black fallow treated with Po4 strain showed a clear trend toward nematode suppression. This trend was statistically confirmed when only the two Po4 strain variants were compared (Table 7—analyze for two variants). A similar tendency was observed in 2023 in plots where sugar beet was cultivated with mycelium application, resulting in a 21.38% reduction in nematode population (Figure 3a,b and Figure 4a,b).

Table 7.

Results of H. schachtii population reduction (or increase) in the field tests; data were statistically evaluated using analysis of variance (p = 0.05); the significance level of differences was assessed using Duncan’s test for the whole experiment and separately for only the fallow soil treated and untreated by Po4; data followed by the same letter do not differ significantly in columns for both years 2023–24 for each analysis.

Figure 4.

Effect of P. ostreatus Po4 strain on the percentage decrease/increase in the H. schachtii population in the field experiments: (a) comparison among experimental variants; (b) direct influence the mycelium addition vs. black fallow. Bars represent the mean percentage change in nematode population ± standard deviation (SD) (3 independent replicates for each strain and condition). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA with Duncan’s test (p = 0.05). Negative values represent population reduction; positive values represent population increase relative to initial population.

In 2023, the estimated root yields per 1 ha were similar for the sugar beet variant (79.2 t·ha−1) and the variant treated with P. ostreatus (78.7 t·ha−1). In 2024, the root yield was higher (18.75%) under the influence of Po4 strain (102.8 t·ha−1) than without mycelium (84.0 t·ha−1) (Table 8). Similar results were obtained for leaf yield and Foliage index, which represents the ratio of leaf to root yield (Table 8).

Table 8.

The influence of Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium on the expected yield level of sugar beet and the technological quality of the obtained roots (data counted according to Reinefeld’s formula [17]).

Other parameters characterizing the yield quality of the crop harvested from plots treated with P. ostreatus mycelium did not exceed those obtained for plots without mycelium. The exceptions were potassium (42.9 mmol·kg−1) and sodium (8.28 mmol·kg−1) contents in 2024, which were higher in Po4 strain-treated plots than in untreated by mycelium plots. Despite this, the biological sugar yield was higher in this case and was expected to reach 17.1 t·ha−1 (Table 8).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study provides the first field-scale evidence that Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium can effectively suppress Heterodera schachtii populations in sugar beet cultivation, a critical step towards developing a practical biocontrol strategy. Although our study was conducted under sugar beet-breeding conditions, the research may be extrapolated to regular agricultural cultivation conditions.

The effects of our experiments were partially due to soil fallowing, which is a well-known, nonchemical method for reducing the potential occurrence of H. schachtii. Both the laboratory and field experiments demonstrated that Pleurotus ostreatus may be useful in reducing H. schachtii populations. The laboratory experiments showed high efficacy for some mycelial offspring derived from the parental strain Po4. These results confirm that searching for highly effective mycelia capable of reducing H. schachtii populations or inhibiting their development is worthwhile. The laboratory-tested mycelia exhibited varying levels of nematocidal activity, which is consistent with our previous studies [14,15] and expectations. Pineda-Alegría et al. [18] reported similar findings for Pleurotus djamor against Haemonchus contortus. In their study, one of the tested strains exhibited lower anthelmintic activity than others. This supports the view that Pleurotus species may produce a wide range of active compounds with nematocidal properties that are present in their fruiting bodies. Therefore, the nematocidal activity cannot be attributed solely to 3-octanone, as suggested by Lee et al. [10]. Previous research by our team clearly demonstrated that the mechanism underlying the reduction in H. schachtii populations involves the entanglement of cysts by P. ostreatus mycelium [15]. The reason for such a mode of action of Pleurotus mycelium in the case of H. schachtii may be a result of a much higher number of cysts in the soil than free larvae, as well as the fact that mycelia more easily reach cysts as a source of nitrogen. To our knowledge, this is the first time that mycelium has been introduced into agricultural soil as a control measure against H. schachtii. Previously, similar experiments were conducted only under laboratory conditions to manage H. schachtii while in the field to protect vegetables from other plant-parasitic nematodes [2,19,20]. The results obtained in the laboratory are highly promising for future research and field applications. However, the field results were less effective than those observed under laboratory conditions, despite our expectations and the findings of Palizi et al. [2]. These differences can be attributed to the complex interactions that occur in the field environment, including those among the introduced strain, native soil microflora, and the chemical agents used in plant protection, which remain currently unknown. Additional factors may be associated with climatic conditions, particularly temperature. In our field experiments, elevated temperatures could have affected 3-octanone volatility, since the temperature inside the tents during summer was likely higher than the ambient temperature outside. Interaction with the soil environment, particularly with the native soil microflora, may influence mycelial activity. However, Pleurotus mycelium appears to exhibit a certain degree of resistance to microbial competition. This conclusion is supported by our observations from laboratory studies and substrate colonization during mushroom production, where the straw-based substrate is not completely sterilized. Moreover, in nature, Pleurotus mycelium typically grows under non-sterile conditions. Considering this, it can be assumed that under field conditions, mycelium introduced into soil containing straw substrate is likely to remain active as long as the straw persists and serves as its primary growth medium. Throughout this period, the mycelium continues to interact and function within the soil environment. In cultivated soils, root exudates represent an important component of the rhizosphere that may affect mycelial activity. Such exudates are known to influence Heterodera schachtii in sugar beet systems; nevertheless, they may also interact with the mycelium by providing readily available nutrients, including sugars and amino acids. Further research is needed to elucidate these interactions, especially in the context of sugar beet and plant species exhibiting nematocidal activity.

Our study represents an initial attempt to apply P. ostreatus on a larger scale for the protection of sugar beet against H. schachtii. The described method could be further improved by selecting and testing new strains, as well as by incorporating supporting organisms, such as plants with nematocidal properties. Another important factor for P. ostreatus is the content of organic matter in the soil, particularly cellulose and lignocellulose (plant residues). Agricultural soils treated primarily with mineral fertilizers typically have insufficient levels of organic matter [21]. The addition of organic materials, such as spent mushroom substrate, can improve soil structure by increasing porosity in both topsoil and subsoil [22] and by enriching the mineral composition [5]. Undecomposed organic matter rich in complex compounds such as lignin and cellulose provides a natural habitat for P. ostreatus mycelium, where nematode bodies serve as an additional nitrogen source for fungal growth [23].

The expected yield quality was comparable to that obtained in standard sugar beet cultivation. This strongly suggests that straw colonized with oyster mushroom mycelium can be considered an effective biological nematocide without negatively affecting yield. In 2024, both root and sugar yields—biological and technological—were higher in plots treated with Pleurotus mycelium. However, this effect was observed in only one study year, suggesting that while promising, the method requires further validation. Nevertheless, it indicates a potential alternative to current strategies for managing the beet cyst nematode (H. schachtii) in sugar beet cultivation. At present, the predominant approach relies on cultivating sugar beet varieties with high tolerance to the nematode. Although tolerant varieties are widely available, their productivity may vary depending on soil suppressiveness. For example, the tolerant variety ‘Nemata’ exhibits substantial yield sensitivity under beet cyst nematode pressure [24].

Similar findings, including increased biomass production, were reported by Tazuba et al. [25] for banana (Musa sp.) and by Nyangwire et al. [20] for eggplant (Solanum melongena). In both studies, pot experiments were conducted using spent P. ostreatus substrates to control Radopholus similis or root-knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.). Promising field results were also reported for tomatoes [26], where spent composts of Pleurotus sajor-caju based on rice or wheat straw were applied against Meloidogyne incognita. Nematode reduction efficiency reached 80.2–85.5% at a dose of 1200 g/m2 of spent mushroom substrate, accompanied by significant increases in fruit yield and quality. The authors recommended treatment with wheat straw-based compost. In our research, the dose of straw–mycelial substrate was approximately on the level of 1800 g/m2, and yield quality was not affected negatively.

Furthermore, a greenhouse experiment using a Pleurotus djamor-spent mushroom substrate against Meloidogyne javanica in lettuce cultivation achieved a 98.68% reduction in nematode reproduction and a 99.75% reduction in population density [27]. However, high concentrations of spent substrate caused some phytotoxic effects in lettuce, including reduced vegetative growth, lower chlorophyll content, and altered nitrogen balance, although anthocyanin levels increased. These results may indicate induced resistance of lettuce to M. javanica.

Our research was conducted for sugar beet-breeding purposes and covered a relatively small cultivation area within a breeding company (experimental breeding tents). The results clearly demonstrate that simultaneous sugar beet cultivation and application of P. ostreatus mycelium on a straw substrate effectively suppressed H. schachtii populations in the soil—an effect that cannot be achieved through the cultivation of tolerant varieties alone. Reuther et al. [24] conducted a three-year study evaluating tolerant sugar beet varieties and their effects on H. schachtii populations. Their results showed that tolerant varieties did not reduce cyst nematode populations; instead, populations increased during cultivation, reaching up to 147% (Pf/Pi = 2.47) for the variety ‘Kleist’. Only the variety ‘Nemata’, considered resistant in this study, limited population growth by reducing nematode density by 34–42% in consecutive years. In contrast, the standard in this research, variety ‘Beretta’ caused a marked increase in H. schachtii populations, with Pf/Pi values of 3.85, 4.87, and 5.10 over three consecutive years. In standardized official trials, sugar beet varieties classified as resistant should achieve a final-to-initial nematode population ratio (Pf/Pi) of less than 1 [24]. This condition has been met only by the ‘Nemata’ variety, whereas other tolerant cultivars typically exceed this threshold [24]. In our experiments, Pf/Pi values below 1 were recorded in both study years, suggesting that the Pleurotus-based method performs comparably to resistant varieties. It should be noted, however, that true resistance to H. schachtii is rare, and most commercial cultivars exhibit only varying degrees of tolerance.

Comparing the results of Reuther et al. [24] to our results, it is clearly seen that the oyster mushroom mycelium achieved greater nematode suppression than tolerant sugar beet varieties. This result is of particular importance for Polish sugar beet-breeding programs, which currently lack domestically developed tolerant cultivars. Future studies should include trials conducted under open-field conditions. Another promising direction for further research involves testing the use of spent oyster mushroom substrate, which could reduce application costs while contributing to improved waste management.

Our research was aimed at identifying an effective method for reducing H. schachtii populations in soils used within breeding tents. In breeding companies, these tents host sugar beet cultivation in prolonged monoculture. Relocating breeding plots or implementing crop rotation within the tents would generate additional costs. Consequently, the tents are typically used for sugar beet cultivation for as long as possible. During that time, the soil becomes heavily infested with the sugar beet cyst nematode. Under such conditions, the development of an efficient method for sanitizing soil from nematode cysts is highly desirable. As a secondary outcome, our experiments produced soil that was effectively cleaned and could be reused for further breeding work. The results demonstrate that the method we tested may be highly effective; however, its economic feasibility was not evaluated. It is reasonable to assume that producing highly active mycelial inoculum for small-scale areas may be acceptable for breeding companies.

Although this method is promising and may eventually apply to agricultural fields or against other nematode pests, its broader implementation requires prior economic assessment. One potential cost-reducing approach for large areas is the use of spent oyster mushroom substrate. Before such a method could be adopted, several issues must be addressed. First, the spent substrate should be evaluated under European climatic conditions using locally cultivated strains. Comparable studies conducted in hot climates have shown favorable results [5]. Spent oyster mushroom substrate has numerous potential applications in agriculture, including aquaculture, enhancement of plant growth and productivity, soil organic amendment, and plant disease suppression [28,29,30,31]. Furthermore, comparative analyses of production costs indicate that biochar derived from spent oyster mushroom substrate is significantly less expensive than biochar produced from many other biomass sources [32].

A remaining challenge concerns legislative frameworks. In several countries, spent mushroom substrate is classified as waste and must therefore be processed or disposed of according to waste management regulations. Its direct agricultural use is restricted unless special permits are obtained or adjustments to national legislation are implemented. Given the substantial benefits that may result from using spent oyster mushroom substrate, addressing these regulatory barriers appears both necessary and worthwhile.

5. Conclusions

Two-year field experiments demonstrated that Pleurotus ostreatus mycelium is capable of effectively reducing Heterodera schachtii populations under natural field conditions, representing a promising biological alternative to conventional chemical control methods. Although only a single mycelial strain was evaluated in field conditions, laboratory results suggest that different strains may exhibit variable levels of nematocidal activity. Consequently, further investigations aimed at identifying and characterizing additional P. ostreatus strains with high efficacy are warranted, particularly in the context of sugar beet breeding companies’ fields. Moreover, extended research on the broader applicability of this approach under diverse agricultural field conditions would be of significant scientific and practical value.

Author Contributions

R.N.—methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation; M.N. (Małgorzata Nabrdalik)—conceptualization, investigation, data curation, supervision, writing—editing; M.N. (Mirosław Nowakowski)—conceptualization, investigation, supervision, writing—review; E.M.—conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, resources, visualization, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development grant number under the program “Biological Progress”, the project for the years 2021–2025, task 22 “Influence of environmental parameters and biological variability of Pleurotus ostreatus in terms of nematocidal activity on Heterodera schachtii”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out at MCBR UO (International Research and Development Center of the University of Opole), which was established as part of a project co-financed by the European Union under the European Regional Development Fund, RPO WO 2014–2020, Action 1.2 Infra-structure for R&D. Agreement No. RPOP.01.02.00-16-0001/17-00 dated 31 January 2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Mwangi, N.G.; Stevens, M.D.; Wright, A.J.D.; Watts, W.D.; Edwards, S.G.; Hare, M.C.; Back, M.A. Population dynamics of stubby root nematodes (Trichodorus and Paratrichodorus spp.) associated with ‘Docking disorder’ of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), in field rotations with cover crops in East England. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2025, 187, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palizi, P.; Goltapeh, E.M.; Pourjam, E.; Safaie, N. Potential of oyster mushrooms for the biocontrol of sugar beet nematode (Heterodera schachtii). J. Plant Prot. Res. 2009, 49, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauer, M.; Koch, H.-J.; Krüssel, S.; Mittler, S.; Märländer, B. Integrated control of Heterodera schachtii Schmidt in Central Europe by trap crop cultivation, sugar beet variety choice and nematicide application. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 99, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, G.L.; Thorn, R.G. Destruction of nematodes by species of Pleurotus. Can. J. Bot. 1987, 65, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L.R.I.; Delmastro, S.; Curvetto, N.R. Spent oyster mushroom substrate in a mix with organic soil for plant pot cultivation. Micol. Apl. Int. 2008, 20, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Degenkolb, T.; Vilcinskas, A. Metabolites from nematophagous fungi and nematicidal natural products from fungi as alternatives for biological control. Part II: Metabolites from nematophagous basidiomycetes and non-nematophagous fungi. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 3813–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, O.C.H.; Plattner, R.; Weisleder, D.; Wicklow, D.T. A nematicidal toxin from Pleurotus ostreatus NRRL 3526. J. Chem. Ecol. 1992, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, N.; Ragucci, S.; Russo, R.; Valletta, M.; Pizzo, E.; Ferreras, J.M.; Di Maro, A. The ribotoxin-like protein Ostreatin from Pleurotus ostreatus fruiting bodies: Confirmation of a novel ribonuclease family expressed in basidiomycetes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 161, 1329–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žužek, M.C.; Maček, P.; Sepčić, K.; Cestnik, V.; Frangež, R. Toxic and lethal effects of ostreolysin, a cytolytic protein from edible oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), in rodents. Toxicon 2006, 48, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-H.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Chang, Y.-C.; Pon, W.-L.; Lee, S.-P.; Wali, N.; Nakazawa, T.; Honda, Y.; Shie, J.-J.; Hsueh, Y.-P. A carnivorous mushroom paralyzes and kills nematodes via a volatile ketone. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliszewska, E. Mushroom flavour. Acta Univ. Lodziensis. Folia Biol. Oecologica 2014, 10, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moliszewska, E.; Nabrdalik, M.; Dickenson, J. Mushrooms as Sources of Flavours and Scents. In Advances in Macrofungi: Pharmaceuticals and Cosmeceuticals; Sridhar, K.R., Deshmukh, S.K., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 252–285. ISBN 9781003191278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Saifullah, M.I.; Hussain, S. Organic control of phytonematodes with Pleurotus species. Pak. J. Nematol. 2014, 32, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kudrys, P.; Nabrdalik, M.; Hendel, P.; Kolasa-Więcek, A.; Moliszewska, E. Trait Variation between Two Wild Specimens of Pleurotus ostreatus and Their Progeny in the Context of Usefulness in Nematode Control. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelke, R.; Nabrdalik, M.; Żurek, M.; Kudrys, P.; Hendel, P.; Nowakowski, M.; Moliszewska, E.B. Nematicidal Properties of Wild Strains of Pleurotus ostreatus Progeny Derived from Buller Phenomenon Crosses. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczorowski, G. Wpływ Chwastów na Populację Heterodera schachtii Schmidt na Polach Gospodarstw Buraczanych. [The Influence of Weeds on the Population of Heterodera schachtii Schmidt in the Fields of Sugar Beet Farms.]. Ph.D. Thesis, Akademia Techniczno-Rolnicza, Bydgoszcz, Bydgoszcz, Poland, 1992; p. 63. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Reinefeld, E.; Emmerich, A.; Baumgarten, G.; Winner, C.; Beiß, U. Zur Voraussage des Melassezuckers aus Rübenanalysen. Zucker 1974, 27, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Alegría, J.A.; Sánchez-Vázquez, J.E.; González-Cortazar, M.; Zamilpa, A.; López-Arellano, M.E.; Cuevas-Padilla, E.J.; Mendoza-de-Gives, P.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L. The Edible Mushroom Pleurotus djamor Produces Metabolites with Lethal Activity Against the Parasitic Nematode Haemonchus contortus. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heydari, R.; Pourjam, E.; Goltapeh, E.M. Antagonistic Effect of Some Species of Pleurotus on the Root-knot Nematode, Meloidogyne javanica in vitro. Plant Pathol. J. 2006, 5, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyangwire, B.; Ocimati, W.; Tazuba, A.F.; Blomme, G.; Alumai, A.; Onyilo, F. Pleurotus ostreatus is a potential biological control agent of root-knot nematodes in eggplant (Solanum melongena). Front. Agron. 2024, 6, 1464111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.; Radicetti, E.; Quintarelli, V.; Petroselli, V.; Marinari, S.; Mancinelli, R. Influence of organic and mineral fertilizers on soil organic carbon and crop productivity under different tillage systems: A meta-analysis. Agriculture 2022, 12, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka, H.; Oda, M.; Hayashi, E.; Tamura, K. Effects of fresh spent mushroom substrate of Pleurotus ostreatus on soil micromorphology in Brazil. Geoderma 2016, 269, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, B.N.; Okazaki, K.; Fukiharu, T.; Takeuchi, Y.; Futai, K.; Le, X.T.; Suzuki, A. Characterization of the nematicidal toxocyst in Pleurotus subgen. Coremiopleurotus. Mycoscience 2007, 48, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuther, M.; Lang, C.; Grundler, F.M.W. Nematode-tolerant sugar beet varieties—resistant or susceptible to the Beet Cyst Nematode Heterodera schachtii? Sugar Ind. 2017, 142, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazuba, A.F.; Ocimati, W.; Ogwal, G.; Nyangwire, B.; Onyilo, F.; Blomme, G. Spent Pleurotus ostreatus Substrate Has Potential for Controlling the Plant-Parasitic Nematode, Radopholus similis in Bananas. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, D.M.; Awd Allah, S.F.A.; Awad-Allah, E.F.A. Potential of Pleurotus sajor-caju compost for controlling Meloidogyne incognita and improve nutritional status of tomato plants. J. Plant Sci. Phytopathol. 2019, 3, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.D.; de Melo Santana Gomes, S.; Schwengber, R.P.; Carpi, M.C.G.; Dias-Arieira, C.R. Control of Meloidogyne javanica with Pleurotus djamor spent mushroom substrate. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aguirre, J.; Hernández, C.; Esqueda, M. Spent oyster mushroom substrate as a potential bioactive and nutritional food ingredient for tilapia culture: A review. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2025, 53, 209–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha Zied, D.; Sánchez, J.E.; Noble, R.; Pardo-Giménez, A. Use of Spent Mushroom Substrate in New Mushroom Crops to Promote the Transition towards A Circular Economy. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, R.W.; Mustafa, M.; Kappel, N.; Csambalik, L.; Szabó, A. Practical applications of spent mushroom compost in cultivation and disease control of selected vegetables species. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yan, S.; Wang, M. Spent mushroom substrate: A review on present and future of green applications. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiduang, W.; Jatuwong, K.; Kiatsiriroat, T.; Kamopas, W.; Tiyayon, P.; Jawana, R.; Xayyavong, O.; Lumyong, S. Spent Mushroom Substrate-Derived Biochar and Its Applications in Modern Agricultural Systems: An Extensive Overview. Life 2025, 15, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).